Submitted:

27 August 2025

Posted:

29 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction:

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Recruitment and Procedures

2.3. Cognitive Function Assessment

2.3.1. Verbal Fluency (Animal Naming; CERAD J1)

2.3.2. Word List Memory (CERAD J4):

2.3.3. Constructional Praxis (CERAD J5):

2.3.4. Word List Recall, Delayed (CERAD J6):

2.3.5. Word List Recognition (CERAD J7):

2.3.6. Recall of Constructional Praxis, Delayed (CERAD J8):

2.4. Dietary Assessment

2.4.1. 24-Hour Dietary Recall:

2.4.2. Short Healthy Eating Index (sHEI):

2.5. Health Questionnaires

2.5.1. Demographics and Health History:

2.5.2. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9):

2.5.3. Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI):

2.6. Statistical Analysis:

2.6.1. Descriptive Statistics and Group Comparisons

2.6.2. Multivariate Regression Modeling

3. Results:

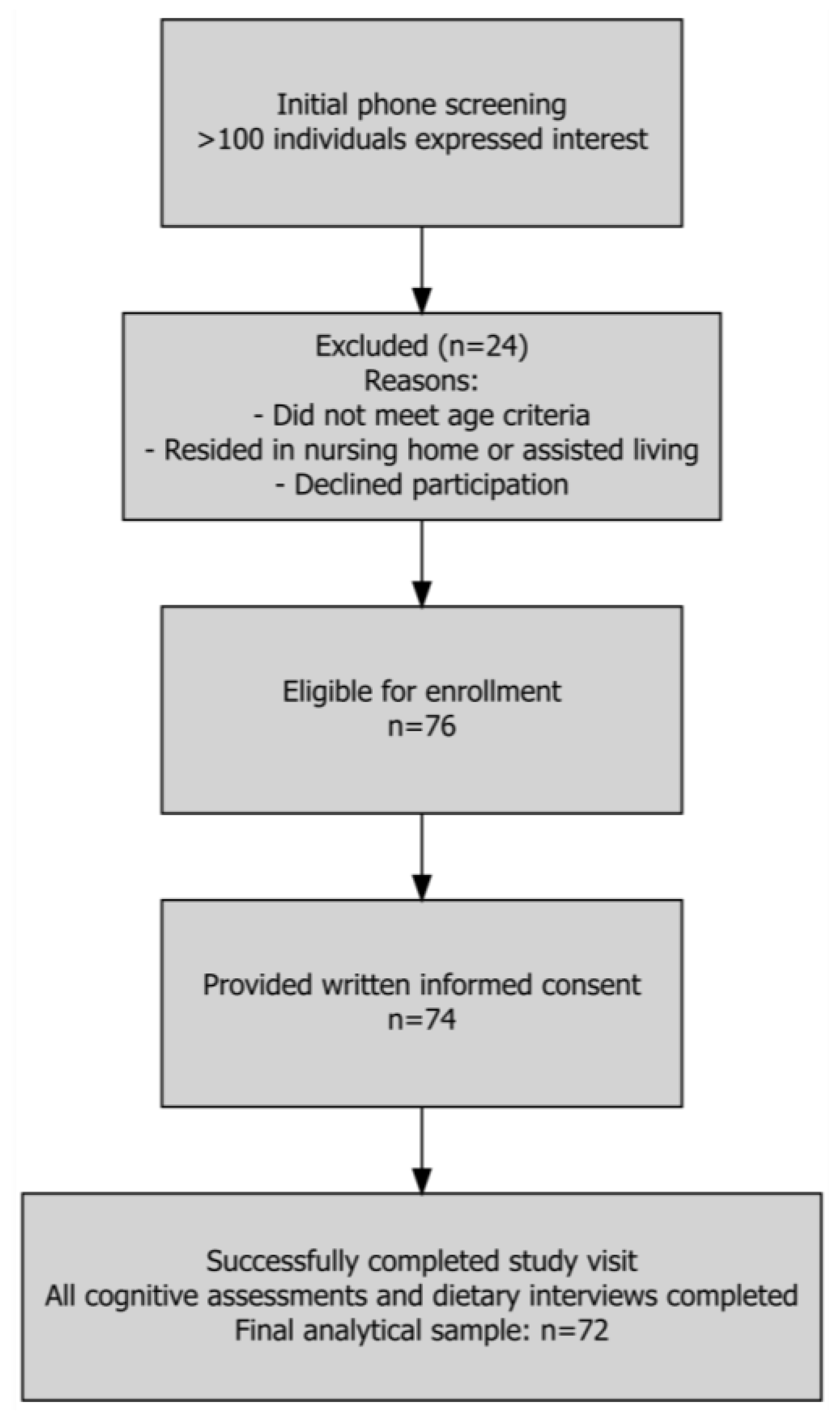

3.1. Participant Flow and Sample Characteristics:

3.2. Cognitive Performance Outcomes:

3.3. Macronutrients and Energy:

3.4. Micronutrient Intake:

| Micronutrient | LCP | HCP | p-value |

| Vitamins | |||

| Vitamin A (RAE, mcg) | 474.0 (346.5) | 713.3 (628.5) | 0.114 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 83.2 (104.2) | 79.0 (78.1) | 0.750 |

| Vitamin D (mcg) | 3.7 (2.9) | 4.5 (5.2) | 0.906 |

| Vitamin E (total, mg) | 7.3 (4.7) | 9.9 (9.6) | 0.338 |

| Vitamin E (added, mg) | 0.8 (2.9) | 0.7 (2.8) | 0.734 |

| Vitamin K (mcg) | 104.7 (188.2) | 127.7 (148.0) | 0.060 |

| Thiamin (mg) | 1.3 (0.7) | 1.4 (1.0) | 0.924 |

| Riboflavin (mg) | 1.5 (0.8) | 1.8 (1.1) | 0.289 |

| Niacin (mg) | 18.6 (11.5) | 20.1 (17.5) | 0.666 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 1.4 (0.8) | 1.5 (0.9) | 0.767 |

| Folate (total, mcg) | 295.8 (177.0) | 319.9 (191.8) | 0.618 |

| Folate (from food, mcg) | 167.5 (101.5) | 207.8 (130.4) | 0.123 |

| Folic Acid (mcg) | 128.4 (136.6) | 112.0 (107.5) | 0.897 |

| Vitamin B12 (total, mcg) | 2.9 (2.3) | 2.9 (2.7) | 0.853 |

| Vitamin B12 (added, mcg) | 0.5 (1.0) | 0.3 (0.7) | 0.252 |

| Choline (mg) | 239.4 (148.0) | 264.0 (195.3) | 0.793 |

| Carotenoids | |||

| α-Carotene (mcg) | 199.2 (437.9) | 932.6 (1276.2) | 0.004 |

| β-Carotene (mcg) | 1424.1 (2247.8) | 3853.2 (4539.2) | 0.012 |

| β-Cryptoxanthin (mcg) | 76.4 (150.2) | 233.0 (556.6) | 0.577 |

| Lutein + Zeaxanthin (mcg) | 1597.8 (4166.2) | 2259.7 (4134.9) | 0.016 |

| Lycopene (mcg) | 2068.8 (5133.2) | 1979.6 (3657.6) | 0.527 |

| Retinol (mcg) | 344.1 (282.8) | 344.0 (323.8) | 0.826 |

| Minerals | |||

| Calcium (mg) | 629.7 (456.3) | 789.0 (582.0) | 0.195 |

| Copper (mg) | 0.9 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.7) | 0.289 |

| Iron (mg) | 10.3 (6.2) | 10.9 (7.1) | 0.784 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 226.1 (142.9) | 275.9 (185.9) | 0.128 |

| Phosphorus (mg) | 948.2 (539.1) | 1124.9 (675.6) | 0.158 |

| Potassium (mg) | 1922.6 (1039.8) | 2345.7 (1313.9) | 0.133 |

| Selenium (mcg) | 79.6 (44.0) | 87.0 (66.9) | 0.978 |

| Zinc (mg) | 7.8 (5.4) | 8.5 (6.2) | 0.436 |

4. Discussion:

Authorship contribution statement

Funding sources

Acknowledgements

Declaration of competing interest

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

Abbreviations

References

- Older Adults Outnumber Children in 11 States and Nearly Half of U.S. Counties. 2025 [cited 2025 08/05]; Available from: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-national-total.html.

- Guerreiro, R. and J. Bras, The age factor in Alzheimer’s disease. Genome Med, 2015. 7: p. 106.

- 2025 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement, 2025. 21(4).

- Tanzi, R.E., The genetics of Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 2012. 2(10).

- Montero-Odasso, M., Z. Ismail, and G. Livingston, One third of dementia cases can be prevented within the next 25 years by tackling risk factors. The case “for” and “against”. Alzheimers Res Ther, 2020. 12(1): p. 81. [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G., et al., Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet standing Commission. Lancet, 2024. 404(10452): p. 572-628. [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G., et al., Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet, 2020. 396(10248): p. 413-446. [CrossRef]

- Ellouze, I., et al., Dietary Patterns and Alzheimer’s Disease: An Updated Review Linking Nutrition to Neuroscience. Nutrients, 2023. 15(14). [CrossRef]

- Grant, W.B. and S.M. Blake, Diet’s Role in Modifying Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease: History and Present Understanding. J Alzheimers Dis, 2023. 96(4): p. 1353-1382.

- Litke, R., et al., Modifiable Risk Factors in Alzheimer Disease and Related Dementias: A Review. Clin Ther, 2021. 43(6): p. 953-965. [CrossRef]

- Stefaniak, O., et al., Diet in the Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease: Current Knowledge and Future Research Requirements. Nutrients, 2022. 14(21). [CrossRef]

- Więckowska-Gacek, A., et al., Western diet as a trigger of Alzheimer’s disease: From metabolic syndrome and systemic inflammation to neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. Ageing Research Reviews, 2021. 70: p. 101397. [CrossRef]

- Barnes, L.L., et al., Trial of the MIND Diet for Prevention of Cognitive Decline in Older Persons. N Engl J Med, 2023. 389(7): p. 602-611. [CrossRef]

- Fekete, M., et al., The role of the Mediterranean diet in reducing the risk of cognitive impairement, dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis. Geroscience, 2025. 47(3): p. 3111-3130. [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.C., et al., MIND diet slows cognitive decline with aging. Alzheimers Dement, 2015. 11(9): p. 1015-22. [CrossRef]

- Figueira, I., et al., Blood-brain barrier transport and neuroprotective potential of blackberry-digested polyphenols: an in vitro study. Eur J Nutr, 2019. 58(1): p. 113-130. [CrossRef]

- Velásquez-Jiménez, D., et al., Phenolic compounds that cross the blood-brain barrier exert positive health effects as central nervous system antioxidants. Food Funct, 2021. 12(21): p. 10356-10369. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R., et al., Association of Dietary and Supplement Intake of Antioxidants with Risk of Dementia: A Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. J Alzheimers Dis, 2024. 99(s1): p. S35-s50. [CrossRef]

- Mao, P., Oxidative Stress and Its Clinical Applications in Dementia. J Neurodegener Dis, 2013. 2013: p. 319898. [CrossRef]

- Dietary Guidelines for Americans, H.H.S. U.S.D.A, Editor. 2020, https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/: https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/.

- Snetselaar, L.G., et al., Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025: Understanding the Scientific Process, Guidelines, and Key Recommendations. Nutr Today, 2021. 56(6): p. 287-295.

- Morris, J.C., et al., The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part I. Clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology, 1989. 39(9): p. 1159-65.

- Fillenbaum, G.G. and R. Mohs, CERAD (Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease) Neuropsychology Assessment Battery: 35 Years and Counting. J Alzheimers Dis, 2023. 93(1): p. 1-27. [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A., et al., Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform, 2009. 42(2): p. 377-81. [CrossRef]

- Lea, A.N., et al., Patient and provider perspectives on self-administered electronic substance use and mental health screening in HIV primary care. Addict Sci Clin Pract, 2022. 17(1): p. 10. [CrossRef]

- Welsh, K.A., et al., The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part V. A normative study of the neuropsychological battery. Neurology, 1994. 44(4): p. 609-14. [CrossRef]

- Colby, S., et al., Development and Validation of the Short Healthy Eating Index Survey with a College Population to Assess Dietary Quality and Intake. Nutrients, 2020. 12(9). [CrossRef]

- Ford, J., et al., Use of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) in Practice: Interactions between patients and physicians. Qual Health Res, 2020. 30(13): p. 2146-2159. [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K., R.L. Spitzer, and J.B. Williams, The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med, 2001. 16(9): p. 606-13.

- Buysse, D.J., et al., The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res, 1989. 28(2): p. 193-213. [CrossRef]

- Hale, J.M., et al., Cognitive impairment in the U.S.: Lifetime risk, age at onset, and years impaired. SSM Popul Health, 2020. 11: p. 100577. [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, S., M. Hossain, and S. Parajuli, The incorporation of red meat in higher-HEI diets supports brain-health critical nutritional adequacy, and gut microbial diversity. Research Square, 2025.

- Dhakal, S., et al., Effects of Lean Pork on Microbiota and Microbial-Metabolite Trimethylamine-N-Oxide: A Randomized Controlled Non-Inferiority Feeding Trial Based on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, 2022. 66(9): p. 2101136. [CrossRef]

- Bandayrel, K. and S. Wong, Systematic literature review of randomized control trials assessing the effectiveness of nutrition interventions in community-dwelling older adults. Journal of nutrition education and behavior, 2011. 43(4): p. 251-262. [CrossRef]

- The Top 10 Most Common Chronic Conditions in Older Adults. 2025, National Council on Aging.

- Iadecola, C., et al., Impact of Hypertension on Cognitive Function: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Hypertension, 2016. 68(6): p. e67-e94. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., et al., Cognitive dysfunction in diabetes: abnormal glucose metabolic regulation in the brain. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2023. 14: p. 1192602. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., et al., Association between Dyslipidaemia and Cognitive Impairment: A Meta-Analysis of Cohort and Case-Control Studies. J Integr Neurosci, 2024. 23(2): p. 40. [CrossRef]

- Spira, A.P., et al., Impact of sleep on the risk of cognitive decline and dementia. Curr Opin Psychiatry, 2014. 27(6): p. 478-83. [CrossRef]

- Godos, J., et al., Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet is Associated with Better Sleep Quality in Italian Adults. Nutrients, 2019. 11(5). [CrossRef]

- Lassale, C., et al., Healthy dietary indices and risk of depressive outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Mol Psychiatry, 2019. 24(7): p. 965-986. [CrossRef]

- Bäckman, L., et al., Multiple cognitive deficits during the transition to Alzheimer’s disease. J Intern Med, 2004. 256(3): p. 195-204. [CrossRef]

- Albert, M.S., et al., The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement, 2011. 7(3): p. 270-9. [CrossRef]

- Rönnlund, M., et al., Stability, growth, and decline in adult life span development of declarative memory: cross-sectional and longitudinal data from a population-based study. Psychol Aging, 2005. 20(1): p. 3-18. [CrossRef]

- Silva, Y.P., A. Bernardi, and R.L. Frozza, The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids From Gut Microbiota in Gut-Brain Communication. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2020. 11: p. 25. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, M.A.W., N.G. Keirns, and Z. Helms, Carbohydrates and cognitive function. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care, 2018. 21(4): p. 302-307.

- Yin, J., et al., A Comprehensive Review of the Effects of Glycemic Carbohydrates on the Neurocognitive Functions Based on Gut Microenvironment Regulation and Glycemic Fluctuation Control. Nutrients, 2023. 15(24). [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.J., et al., Relationship between Serum and Brain Carotenoids, α-Tocopherol, and Retinol Concentrations and Cognitive Performance in the Oldest Old from the Georgia Centenarian Study. J Aging Res, 2013. 2013: p. 951786. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.J., Role of lutein and zeaxanthin in visual and cognitive function throughout the lifespan. Nutr Rev, 2014. 72(9): p. 605-12. [CrossRef]

- Lopes da Silva, S., et al., Plasma nutrient status of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement, 2014. 10(4): p. 485-502.

- Farina, N., et al., Vitamin E for Alzheimer’s dementia and mild cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2017. 4(4): p. Cd002854.

- Slutsky, I., et al., Enhancement of learning and memory by elevating brain magnesium. Neuron, 2010. 65(2): p. 165-77. [CrossRef]

- Kitazono, T., et al., Role of potassium channels in cerebral blood vessels. Stroke, 1995. 26(9): p. 1713-23. [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.D. and H. Refsum, Homocysteine, B Vitamins, and Cognitive Impairment. Annu Rev Nutr, 2016. 36: p. 211-39. [CrossRef]

| Characteristic |

Overall N = 721 |

LCP N = 361 |

HCP N = 361 |

p-value2 |

| Age | 77.5 (6.1) | 79.5 (6.6) | 75.5 (4.9) | 0.009 |

| Not reported | 9 | 4 | 5 | |

| Sex | 0.015 | |||

| Male | 25 (36%) | 17 (50%) | 8 (22%) | |

| Female | 45 (64%) | 17 (50%) | 28 (78%) | |

| Not reported | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| Family History of Dementia | 22 (32%) | 8 (24%) | 14 (40%) | 0.14 |

| Alcohol | 35 (51%) | 17 (50%) | 18 (51%) | >0.9 |

| Hypertension | 35 (49%) | 20 (56%) | 15 (42%) | 0.2 |

| Diabetes | 13 (18%) | 4 (11%) | 9 (25%) | 0.13 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 33 (46%) | 16 (44%) | 17 (47%) | 0.8 |

| Obesity | 19 (26%) | 8 (22%) | 11 (31%) | 0.4 |

| Number of Comorbidities | ||||

| 0 | 15 (21%) | 8 (22%) | 7 (19%) | |

| 1 | 30 (42%) | 14 (39%) | 16 (44%) | |

| 2 | 14 (19%) | 9 (25%) | 5 (14%) | |

| 3 | 10 (14%) | 4 (11%) | 6 (17%) | |

| 4 | 3 (4.2%) | 1 (2.8%) | 2 (5.6%) |

| Cognitive Outcomes |

Overall N = 721 |

LCP N = 361 |

HCP N = 361 |

p-value2 |

| Word List Memory (Immediate) | 5.2 (2.8) | 3.4 (2.2) | 7.1 (2.0) | <0.001 |

| Constructional Praxis (Copy) | 9.7 (1.7) | 8.9 (1.9) | 10.5 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| Word List Recall (Delayed) | 3.9 (2.6) | 2.0 (1.9) | 5.8 (1.4) | <0.001 |

| Word List Recognition | 18.1 (1.7) | 17.3 (2.0) | 18.9 (1.0) | <0.001 |

| Constructional Praxis (Delayed Recall) | 8.1 (2.5) | 6.6 (2.3) | 9.7 (1.4) | <0.001 |

| Total Cognitive Score | 45.0 (8.5) | 38.1 (5.5) | 52.0 (4.0) | <0.001 |

| Memory Composite Score | 27.2 (6.0) | 22.6 (4.0) | 31.8 (3.7) | <0.001 |

| Visuospatial Composite Score | 17.8 (3.7) | 15.4 (3.7) | 20.2 (1.8) | <0.001 |

| Executive Functioning Score | 20.3 (6.6) | 18.6 (5.3) | 22.0 (7.4) | 0.056 |

| Dietary Variable |

Overall N = 721 |

LCP N = 361 |

HCP N = 361 |

p-value2 | |

| Dietary Intake & Quality | Energy (kcal/day) | 1,662.8 (978.0) | 1,529.5 (824.5) | 1,796.1 (1,106.2) | 0.3 |

| Protein (g/day) | 61.3 (40.0) | 57.1 (32.5) | 65.6 (46.5) | 0.6 | |

| Carbohydrate (g/day) | 192.0 (128.1) | 176.0 (85.5) | 207.9 (159.6) | 0.7 | |

| Total Sugars (g/day) | 84.8 (72.5) | 76.5 (48.2) | 93.0 (90.6) | 0.6 | |

| Dietary Fiber (g/day) | 16.0 (9.7) | 14.0 (7.7) | 18.0 (11.1) | 0.2 | |

| Total Fat (g/day) | 73.2 (53.8) | 64.9 (43.1) | 81.5 (62.3) | 0.2 | |

| Saturated Fat (g/day) | 22.4 (16.1) | 19.9 (13.2) | 24.9 (18.4) | 0.2 | |

| Monounsaturated Fat (g/day) | 26.6 (24.1) | 23.4 (18.6) | 29.8 (28.4) | 0.2 | |

| Polyunsaturated Fat (g/day) | 18.1 (14.5) | 16.0 (11.2) | 20.2 (17.0) | 0.4 | |

| Guideline Adherence (% Meeting) | HEI Total Score | 54.4 (9.4) | 54.0 (9.3) | 54.8 (9.6) | 0.5 |

| sHEI Total Score | 52.1 (9.7) | 53.0 (9.0) | 51.1 (10.5) | 0.4 | |

| Protein AMDR (10-35%) | 61 (85%) | 32 (89%) | 29 (81%) | 0.3 | |

| Carbohydrate AMDR (45-65%) | 35 (49%) | 20 (56%) | 15 (42%) | 0.2 | |

| Fat AMDR (20-35%) | 23 (32%) | 14 (39%) | 9 (25%) | 0.2 | |

| Saturated Fat (<10% kcal) | 22 (31%) | 13 (36%) | 9 (25%) | 0.3 | |

| Fiber Recommendation | 7 (9.7%) | 3 (8.3%) | 4 (11%) | >0.9 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).