Submitted:

25 December 2024

Posted:

26 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sampling Method and Study Population

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Cognitive Function Assessment

2.5. Plant-Based Diet Indices and Dietary Assessment

2.6. Assessment of Covariates

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Basic Information

3.2. Nutrition-Related Determinants of MCI in Female and Male

3.3. Analysis on the Association between Plant-Based Diets and MCI in Female and Male

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Behr L C, Simm A, Kluttig A, et al. 60 years of healthy aging: On definitions, biomarkers, scores and challenges[J]. Ageing Research Reviews, 2023,88:101934. [CrossRef]

- Zhao L. A review of healthy aging in China, 2000–2019[J]. Health Care Science, 2022,1(2):111-118. [CrossRef]

- V N. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019[J]. Lancet, 2020,396(10258):1204-1222. [CrossRef]

- Cao Y, Yu F, Lyu Y, et al. Promising candidates from drug clinical trials: Implications for clinical treatment of Alzheimer's disease in China[J]. Frontiers in Neurology, 2022,13. [CrossRef]

- DeCarli C. Mild cognitive impairment: prevalence, prognosis, aetiology, and treatment.[J]. The Lancet. Neurology., 2003(1):15-21.

- Petersen R C, Roberts R O, Knopman D S, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: ten years later[J]. Arch Neurol, 2009,66(12):1447-1455. [CrossRef]

- Flanagan E, Lamport D, Brennan L, et al. Nutrition and the ageing brain: Moving towards clinical applications[J]. Ageing Res Rev, 2020,62:101079. [CrossRef]

- Solfrizzi V, Custodero C, Lozupone M, et al. Relationships of Dietary Patterns, Foods, and Micro- and Macronutrients with Alzheimer's Disease and Late-Life Cognitive Disorders: A Systematic Review[J]. J Alzheimers Dis, 2017,59(3):815-849. [CrossRef]

- Ngabirano L, Samieri C, Feart C, et al. Intake of Meat, Fish, Fruits, and Vegetables and Long-Term Risk of Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease[J]. J Alzheimers Dis, 2019,68(2):711-722. [CrossRef]

- Li M, Shi Z. A Prospective Association of Nut Consumption with Cognitive Function in Chinese Adults aged 55+ _ China Health and Nutrition Survey[J]. J Nutr Health Aging, 2019,23(2):211-216. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Chen J, Qiu J, et al. Intakes of fish and polyunsaturated fatty acids and mild-to-severe cognitive impairment risks: a dose-response meta-analysis of 21 cohort studies[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2016,103(2):330-340. [CrossRef]

- Kuczmarski M F, Allegro D, Stave E. The association of healthful diets and cognitive function: a review[J]. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr, 2014,33(2):69-90. [CrossRef]

- Wood A H R, Chappell H F, Zulyniak M A. Dietary and supplemental long-chain omega-3 fatty acids as moderators of cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease[J]. Eur J Nutr, 2022,61(2):589-604. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Xiao M, Leng L, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence and correlation of mild cognitive impairment in sarcopenia[J]. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle, 2023,14(1):45-56. [CrossRef]

- Sachdev P S, Lipnicki D M, Crawford J, et al. Risk profiles for mild cognitive impairment vary by age and sex: the Sydney Memory and Ageing study[J]. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry, 2012,20(10):854-865. [CrossRef]

- Lee L K, Shahar S, Chin A, et al. Prevalence of gender disparities and predictors affecting the occurrence of mild cognitive impairment (MCI)[J]. Arch Gerontol Geriatr, 2012,54(1):185-191. [CrossRef]

- Song M, Wang Y, Wang R, et al. Prevalence and risks of mild cognitive impairment of Chinese community-dwelling women aged above 60 years: A cross-sectional study[J]. Arch Womens Ment Health, 2021,24(6):903-911. [CrossRef]

- Xu S, Xie B, Song M, et al. High prevalence of mild cognitive impairment in the elderly: a community-based study in four cities of the Hebei province, china[J]. Neuroepidemiology, 2014,42(2):123-130. [CrossRef]

- Huang Q, Jia X, Zhang J, et al. Diet–Cognition Associations Differ in Mild Cognitive Impairment Subtypes[J]. Nutrients, 2021,13(4):1341. [CrossRef]

- Katzman R, Zhang M Y, Ouang-Ya-Qu, et al. A Chinese version of the Mini-Mental State Examination; impact of illiteracy in a Shanghai dementia survey[J]. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 1988,41(10):971. [CrossRef]

- Lu J, Li D, Li F, et al. Montreal Cognitive Assessment in Detecting Cognitive Impairment in Chinese Elderly Individuals: A Population-Based Study[J]. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 2011,24(4):184-190. [CrossRef]

- Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, et al. Mild cognitive impairment – beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment[J]. Journal of internal medicine, 2004,256(3):240-246. [CrossRef]

- Julayanont P, Brousseau M, Chertkow H, et al. Montreal Cognitive Assessment Memory Index Score (MoCA-MIS) as a Predictor of Conversion from Mild Cognitive Impairment toA lzheimer's Disease[J]. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 2014,62(4):679-684. [CrossRef]

- Satija A, Bhupathiraju S N, Spiegelman D, et al. Healthful and Unhealthful Plant-Based Diets and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in U.S. Adults[J]. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 2017,70(4):411-422. [CrossRef]

- Huang F, Wang H, Wang Z, et al. Is geriatric depression scale a valid instrument to screen depression in Chinese community-dwelling elderly?[J]. BMC Geriatrics, 2021,21(1). [CrossRef]

- China N H A F. Criteria of Weight for Adults[S]. Beijing, China: Standards Press of China, 2013.

- Chen C. Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Overweight and Obesity in Chinese Adults [M]. 3. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House, 2006.

- Chen L, Woo J, Assantachai P, et al. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 Consensus Update on Sarcopenia Diagnosis and Treatment[J]. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 2020,21(3):300-307. [CrossRef]

- Jia X, Wang Z, Huang F, et al. A comparison of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) for mild cognitive impairment screening in Chinese middle-aged and older population: a cross-sectional study[J]. BMC Psychiatry, 2021,21(1). [CrossRef]

- Blum D, Cailliau E, Behal H, et al. Association of caffeine consumption with cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease: A BALTAZAR cohort study[J]. Alzheimers Dement, 2024,20(10):6948-6959. [CrossRef]

- Orozco Arbelaez E, Banegas J R, Rodriguez Artalejo F, et al. [Influence of habitual chocolate consumption over the Mini-Mental State Examination in Spanish older adults][J]. Nutr Hosp, 2017,34(4):841-846. [CrossRef]

- Sakurai K, Okada E, Anzai S, et al. Protein-Balanced Dietary Habits Benefit Cognitive Function in Japanese Older Adults[J]. Nutrients, 2023,15(3). [CrossRef]

- Gagnon C, Greenwood C E, Bherer L. The acute effects of glucose ingestion on attentional control in fasting healthy older adults[J]. Psychopharmacology, 2010,211(3):337-346. [CrossRef]

- Ooi C P, Loke S C, Yassin Z, et al. Carbohydrates for improving the cognitive performance of independent-living older adults with normal cognition or mild cognitive impairment[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2011,2011(4):CD007220. [CrossRef]

- Best T, Kemps E, Bryan J. Saccharide Effects on Cognition and Well-Being in Middle-Aged Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial[J]. Developmental neuropsychology, 2010,35(1):66-80. [CrossRef]

- Xue J, Jiao Y, Wang J, et al. The Incidence and Burden of Risk Factors for Mild Cognitive Impairment in Older Rural Chinese Persons[J]. Gerontol Geriatr Med, 2022,8:1682809665. [CrossRef]

- Wennberg A M V, Wu M N, Rosenberg P B, et al. Sleep Disturbance, Cognitive Decline, and Dementia: A Review[J]. Semin Neurol, 2017,37(4):395-406. [CrossRef]

- Jokisch M, Schramm S, Weimar C, et al. Fluctuation of depressive symptoms in cognitively unimpaired participants and the risk of mild cognitive impairment 5 years later: Results of the Heinz Nixdorf Recall study[J]. Front Behav Neurosci, 2022,16:988621. [CrossRef]

- Zafar J, Malik N I, Atta M, et al. Loneliness may mediate the relationship between depression and the quality of life among elderly with mild cognitive impairment[J]. Psychogeriatrics, 2021,21(5):805-812. [CrossRef]

- Toloraia K, Meyer A, Beltrani S, et al. Anxiety, Depression, and Apathy as Predictors of Cognitive Decline in Patients With Parkinson's Disease-A Three-Year Follow-Up Study[J]. Front Neurol, 2022,13:792830. [CrossRef]

- Goveas J S, Espeland M A, Woods N F, et al. Depressive symptoms and incidence of mild cognitive impairment and probable dementia in elderly women: the Women's Health Initiative Memory Study[J]. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2011,59(1):57-66. [CrossRef]

- Van Bogart K, Harrington E E, Witzel D D, et al. Momentary loneliness and intrusive thoughts among older adults: the interactive roles of mild cognitive impairment and marital status[J]. Aging Ment Health, 2024,28(12):1785-1792. [CrossRef]

- Peng J, Li X, Wang J, et al. Association between plant-based dietary patterns and cognitive function in middle-aged and older residents of China[J]. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hewlings S J, Draayer K, Kalman D S. Palm Fruit Bioactive Complex (PFBc), a Source of Polyphenols, Demonstrates Potential Benefits for Inflammaging and Related Cognitive Function[J]. Nutrients, 2021,13(4). [CrossRef]

- Smith L, Lopez Sanchez G F, Veronese N, et al. Association of Fruit and Vegetable Consumption With Mild Cognitive Impairment in Low- and Middle-Income Countries[J]. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2023,78(8):1410-1416. [CrossRef]

- Fangfang H, Qiong W, Shuai Z, et al. Vegetable and Fruit Intake, Its Patterns, and Cognitive Function: Cross-Sectional Findings among Older Adults in Anhui, China[J]. J Nutr Health Aging, 2022,26(5):529-536. [CrossRef]

| Variables | Women | Men | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCI, n (%) | Normal, n (%) | χ2 | P | MCI, n (%) | Normal, n (%) | χ2 | P | ||||

| Total | 141(24.7) | 430(75.3) | 126(24.5) | 388(75.5) | |||||||

| Region | 4.408 | 0.036 | 0.114 | 0.736 | |||||||

| Urban | 90(63.8) | 231(53.7) | 59(46.8) | 175(45.1) | |||||||

| Rural | 51(36.2) | 199(46.3) | 67(53.2) | 213(54.9) | |||||||

| Age, year | 19.480 | <0.001 | 24.590 | <0.0001 | |||||||

| 55~65 | 37(26.2) | 166(38.6) | 26(20.6) | 143(36.9) | |||||||

| 65~75 | 58(41.1) | 195(45.4) | 52(41.3) | 175(45.1) | |||||||

| 75~ | 46(32.6) | 69(16.1) | 48(38.1) | 70(18.0) | |||||||

| Educational level | 1.415 | 0.234 | 3.281 | 0.070 | |||||||

| Junior school or below | 126(91.3) | 374(87.6) | 110(89.4) | 318(82.6) | |||||||

| High school or above | 12(8.7) | 53(12.4) | 13(10.6) | 67(17.4) | |||||||

| Occupation | 0.434 | 0.51 | 0.915 | 0.339 | |||||||

| employed or re-employ after retirement or seeking employment | 127(90.1) | 395(91.9) | 101(80.2) | 295(76.0) | |||||||

| Retirement or unemployed | 14(9.9) | 35(8.1) | 25(19.8) | 93(24.0) | |||||||

| Marital status | 4.616 | 0.032 | 1.443 | 0.230 | |||||||

| married | 104(73.7) | 353(82.1) | 117(92.9) | 346(89.2) | |||||||

| unmarried/ divorced/widowed | 37(26.2) | 77(17.9) | 9(7.1) | 42(10.8) | |||||||

| BMI(kg/m2) | 0.25 | 0.882 | 2.229 | 0.328 | |||||||

| <24.0 | 74(54.8) | 241(57.0) | 73(59.4) | 194(52.2) | |||||||

| ≥24~<28 | 45(33.3) | 137(32.4) | 43(35.0) | 147(39.5) | |||||||

| ≥28 | 16(11.9) | 45(10.6) | 7(5.7) | 31(8.3) | |||||||

| Live alone | 3.108 | 0.078 | 0.354 | 0.552 | |||||||

| Yes | 128(90.8) | 408(94.9) | 122(96.8) | 371(95.6) | |||||||

| No | 13(9.2) | 22(5.1) | 4(3.2) | 17(4.4) | |||||||

| Depression | 20.655 | <0.001 | 3.339 | 0.068 | |||||||

| Yes | 127(90.1) | 423(98.4) | 117(92.9) | 375(96.7) | |||||||

| No | 14(9.9) | 7(1.6) | 9(7.1) | 13(3.4) | |||||||

| Cereal# | 16.685 | <0.001 | 25.162 | <0.0001 | |||||||

| <300 g | 94(66.5) | 201(46.9) | 75(59.5) | 133(34.3) | |||||||

| ≥300 g | 47(33.3) | 228(53.2) | 51(40.5) | 255(65.7) | |||||||

| Vegetables intake | 7.996 | 0.005 | 10.374 | 0.001 | |||||||

| <150 g | 89(63.1) | 212(49.4) | 72(57.1) | 158(40.7) | |||||||

| ≥150 g | 52(36.9) | 217(50.6) | 54(42.9) | 230(59.3) | |||||||

| Fruit intake | 9.030 | 0.003 | 6.122 | 0.013 | |||||||

| <50 g | 95(67.4) | 227(52.9) | 92(73.0) | 236(60.8) | |||||||

| ≥50 g | 46(32.6) | 202(47.1) | 34(27.0 | 152(39.2) | |||||||

| Soybean intake | 4.154 | 0.004 | 1.503 | 0.002 | |||||||

| <38 g | 106(75.2) | 283(66.0) | 84(66.7) | 235(60.6) | |||||||

| ≥38g | 35(24.8) | 146(34.0) | 42(33.3) | 153(39.4) | |||||||

| Vegetable oil intake | 6.830 | 0.009 | 6.610 | 0.010 | |||||||

| <22 g | 93(66.0) | 229(53.4) | 84(66.7) | 208(53.6) | |||||||

| ≥22g | 48(34.0) | 200(46.6) | 42(33.3) | 180(46.4) | |||||||

| Strong teat intake | 0.386 | 0.535 | 0.347 | 0.556 | |||||||

| no | 130(91.2) | 389(90.5) | 94(74.6) | 279(71.9) | |||||||

| yes | 11(7.8) | 41(9.5) | 32(25.4) | 109(28.1) | |||||||

| Nuts intake | 6.761 | 0.009 | 2.725 | 0.099 | |||||||

| <5 g | 109(77.3) | 282(65.6) | 94(74.6) | 259(66.8) | |||||||

| ≥5 g | 32(22.7) | 148(34.4) | 32(25.4) | 129(33.3) | |||||||

| Plant-based diet indices* | PDI | 48.2±6.4 | 49.7±6.5 | 2.10 | 0.037 | 48.6±5.9 | 50.1±6.7 | 2.11 | 0.35 | ||

| hPDI | 56.4±5.6 | 57.6±4.8 | 2.16 | 0.032 | 57.3±4.8 | 57.4±5.0 | 0.19 | 0.847 | |||

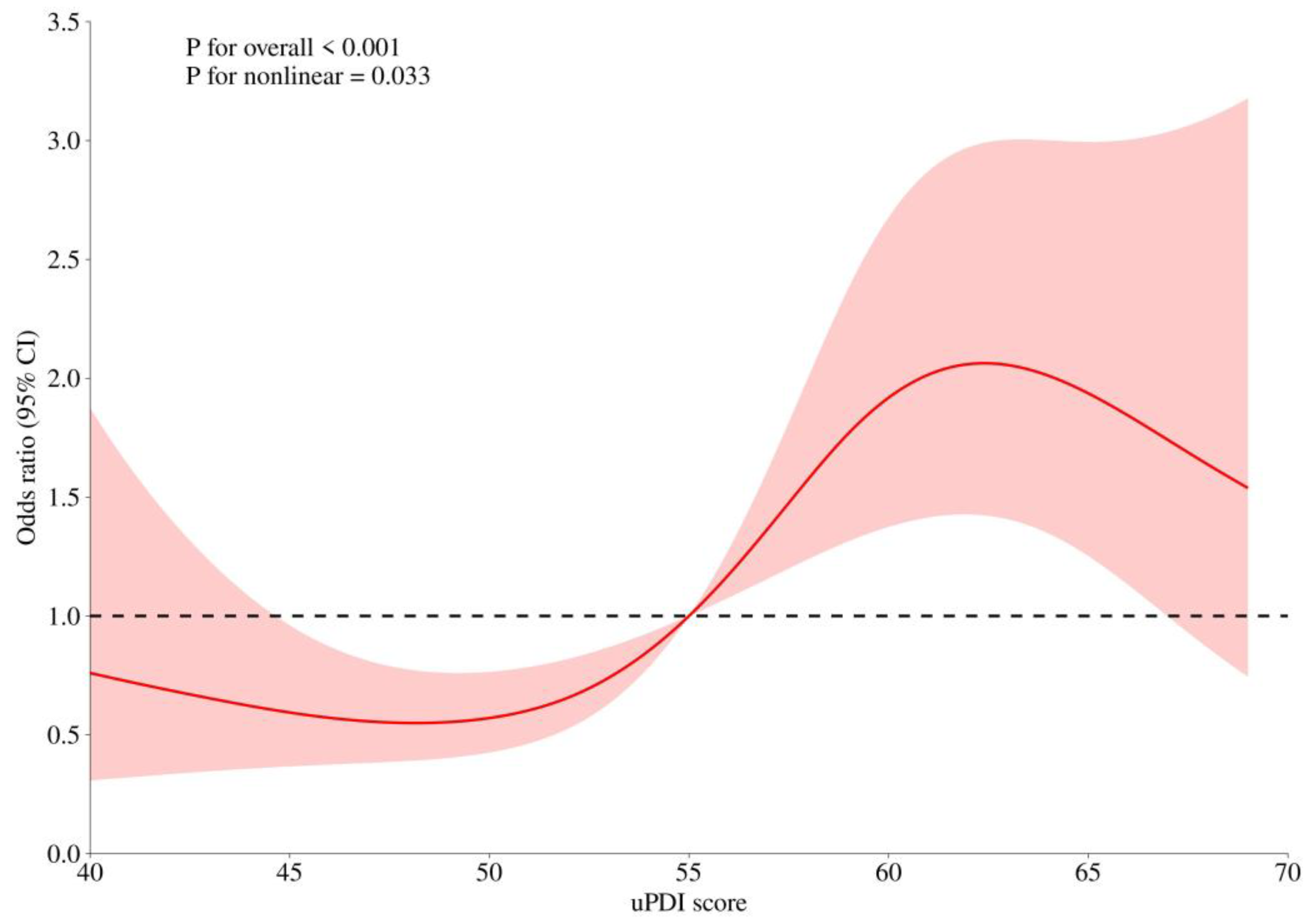

| uPDI | 57.7±7.4 | 54.7±7.6 | -3.78 | 0.0002 | 56.32±7.4 | 54.05.9±7.5 | -2.77 | 0.0058 | |||

| Sarcopenia related | |||||||||||

| Sarcopenia | 0.342 | 0.559 | 1.650 | 0.199 | |||||||

| No | 134(97.1) | 410 (96.0) |

113(90.4) | 362(93.8) | |||||||

| Yes | 4(2.9) | 17(4.0) | 12(9.6) | 24(6.2) | |||||||

| low muscle mass | 1.352 | 0.245 | 1.348 | 0.246 | |||||||

| No | 122(95.3) | 347(92.3) | 92(85.2) | 285(89.3) | |||||||

| Yes | 6(4.7) | 29(7.7) | 16(14.8) | 34(10.7) | |||||||

| low muscle strength or performance | 7.303 | 0.026 | 4.200 | 0.122 | |||||||

| No low muscle strength or performance | 69(50.4) | 216(50.8) | 49(39.5) | 158(41.9) | |||||||

| Low muscle strength or performance | 48(35.0) | 178(41.9) | 50(40.3) | 171(45.4) | |||||||

| low muscle strength and performance | 20(14.6) | 31(7.3) | 25(20.2) | 48(12.7) | |||||||

| Variables | β | sxˉ | Wald χ2 | OR(95%CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| intercept | -3.9696 | 0.8982 | 19.5336 | <.0001 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| married | ||||||

| unmarried/ divorced/ widowed |

0.6672 | 0.2907 | 5.2669 | 1.949(1.102~3.445) | 0.0217 | |

| Depression | ||||||

| Yes | 1.8018 | 0.6004 | 9.0059 | 6.061 (1.868~19.660) | 0.0027 | |

| No | ||||||

| Cereal | ||||||

| <300 g | ||||||

| ≥300 g | -1.1450 | 0.2562 | 19.9714 | 0.318(0.193~0.526) | <0.0001 | |

| uPDI | 0.0545 | 0.0156 | 12.2135 | 1.056 (1.024~1.089) | 0.0005 |

| Variables | β | sxˉ | Wald χ2 | OR(95%CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| intercept | 0.9000 | 0.3106 | 8.3991 | 0.0038 | ||

| Region | ||||||

| Urban | ||||||

| Rural | 0.6438 | 0.2727 | 5.5734 | 1.904(1.116~3.249) | 0.0182 | |

| Age, year | ||||||

| 55~65 | ||||||

| 65~75 | 0.6729 | 0.3062 | 4.8286 | 1.96 (1.075~3.572) | 0.0280 | |

| 75~ | 1.5504 | 0.3366 | 21.2155 | 4.713 (2.437~9.117) | <0.0001 | |

| Vegetables intake | ||||||

| <150 g | ||||||

| ≥150 g | -0.9390 | 0.2658 | 12.4781 | 0.391 (0.232~0.658) | 0.0004 | |

| Vegetable oil intake | ||||||

| <22 g | ||||||

| ≥22g | -0.6901 | 0.2511 | 7.5516 | 0.502 (0.307~0.820) | 0.006 | |

| Cereal | ||||||

| <300 g | ||||||

| ≥300 g | -0.8251 | 0.2456 | 11.2892 | 0.438 (0.271~0.709) | 0.0008 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).