1. Introduction

The Valle del Cauca region is one of Colombia’s most active agro-industrial areas, combining high agricultural productivity with unique ecological richness. The territory is sustained by ecosystems that range from coastal plains to montane forests, which support both biological diversity and productive capacity. It ranks as the third-largest producer and consumer of pork in the country, with a reported output of 88105 tons in 2023, equivalent to 15.6% of national production, and an average pig population exceeding 396000 animals [

1,

2]. This sector generates large volumes of pig manure (PM) that require appropriate handling to prevent environmental and public health risks. Another productive activity with growing regional relevance is cassava cultivation, which covered approximately 564 hectares in 2020, yielding a total of 9888 tons of fresh roots [

1]. During starch extraction, each kilogram of cassava generates about 0.2 kilograms of starch, 0.65 kilograms of fibrous residue (cassava dregs (CD)), and between five and seven liters of wastewater [

3]. Based on these ratios, the estimated annual generation of by-products in the region reaches nearly 6427 tons, most of which are not currently valorized [

4,

5,

6].

To address the increasing accumulation of organic residues from pig farming and cassava processing, anaerobic digestion (AD) has been promoted in rural areas of Valle del Cauca as a strategy for energy recovery and waste management. In these settings, one phase tubular biodigesters are commonly employed due to their affordable construction, ease of installation and minimal infrastructure requirements, making them particularly attractive to smallholder producers [

7,

8]. AD is a biologically mediated process in which organic matter is sequentially transformed into methane through four main stages, each driven by specific microbial groups. In the hydrolysis phase, hydrolytic bacteria degrade complex macromolecules such as carbohydrates, proteins and lipids into soluble monomers. These compounds are then metabolized by acidogenic bacteria during acidogenesis, producing volatile fatty acids (VFA), alcohols and gases like hydrogen and carbon dioxide. In the subsequent acetogenesis stage, acetogenic microorganisms convert these intermediates into acetate, which, along with hydrogen and carbon dioxide, is used by methanogenic archaea in the final phase to generate methane [

9].

For the process to remain stable and efficient, environmental conditions such as pH and temperature must be kept within optimal ranges, typically between 6.5 and 7.5 for pH and 30 to 38 °C under mesophilic conditions [

10,

11,

12,

13]. In addition, maintaining a C:N ratio between 20:1 and 30:1 is considered ideal for AD, as it ensures sufficient nitrogen for microbial growth without leading to ammonia inhibition or carbon limitation [

14,

15,

16,

17]. However, most rural systems lack monitoring tools and operate through empirical practices, without clear understanding of internal conditions or microbial dynamics [

7]. This limitation frequently leads to process imbalance, reduced performance and early system failure.

To overcome the performance limitations of conventional digesters, several strategies have been developed to improve substrate biodegradability and enhance biogas production. Among them, mechanical pre-treatments, codigestion, and multiphase configurations have proven to be particularly effective in increasing system efficiency [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Mechanical pre-treatments have proven effective in enhancing the hydrolysis of lignocellulosic substrates by reducing particle size and fiber crystallinity, thus increasing surface area and enzymatic accessibility [

23,

24]. Depending on specific conditions, methane production improvements of 16% to 99% have been reported with mechanical treatments [

25]. These results highlight the potential of simple mechanical treatments to enhance biodegradability and biogas productivity, especially during the hydrolysis and acidogenesis phases, which are often rate-limited in solid waste digestion.

Codigestion has emerged as a robust strategy to address the nutrient imbalances and low biodegradability often associated with single-substrate digestion. By combining complementary feedstocks, this approach improves the carbon to nitrogen (C:N) ratio, dilutes inhibitors, and stimulates microbial activity, allowing for higher energy yields [

26]. For instance, it has been reported that co-digesting PM with cassava pulp at inclusion levels of up to 60% of the incoming volatile solids (VS) can increase the specific methane yield by around 41% compared with PM alone [

27]. Similarly, results have also shown that mixtures containing 66% PM, 16% cassava pulp, and 16% bagasse achieve higher methane yields than those with high bagasse content alone, which led to pH imbalances and process failure [

28]. Likewise, experimental trials combining sewage sludge with food waste reported an increase in methane yield from 159 to 799 mL CH

4/gVS, along with a reduction in hydraulic retention time (HRT) to less than four days [

29]. These improvements are attributed to enhanced microbial synergy and substrate availability, which accelerate volatile solids degradation.

Multiphase AD systems have been developed to address the limitations of single-stage configurations by creating distinct operational environments for each metabolic phase. In two-phase systems, the acidogenic and methanogenic stages are physically separated, which enables more efficient substrate conversion, greater resilience to organic shocks, and better pH control [

30,

31]. This structural decoupling has led to increases in methane yields, improved volatile solids removal, and significant reductions in HRT without compromising performance [

31]. Compared to single-stage systems, which often suffer from suboptimal compromises between the needs of different microbial groups, two-phase configurations facilitate the coexistence of specialized communities under more stable conditions [

31,

32]. Although three-phase systems further refine process compartmentalization by isolating hydrolysis, acidogenesis, and methanogenesis, they often entail higher operational complexity, energy consumption, and maintenance requirements [

33]. These drawbacks have limited their scalability, particularly in low-resource contexts. Consequently, two-phase systems strike a practical balance between performance enhancement and technical feasibility, making them a more accessible alternative for decentralized applications.

Among the strategies developed to improve AD performance, the integration of real-time monitoring systems has become increasingly relevant for enhancing process oversight and operational efficiency [

34,

35]. Basic and key variables such as pH, temperature, and methane concentration can be considered to infer the internal state of the reactor and anticipate potential imbalances. The use of cost-effective IoT platforms such as ESP32 microcontrollers coupled with sensor has proven suitable for real-time tracking, achieving deviations below 2% for CH

4 and 1.7% for pH when compared to laboratory-grade methods [

34,

35,

36]. Systems incorporating the MQ-4 sensor (200–10,000 ppm CH

4) and platforms like ThingSpeak facilitate continuous data acquisition, cloud visualization, and automatic alerts, offering a practical solution to reduce manual intervention and increase system reliability [

35,

37,

38].

In parallel, greater attention should be given to the microbial community (MC) involved in AD, as they are rarely considered in routine operation despite being responsible for driving the entire process [

9]. Recent studies have highlighted that variations in microbial structure are strongly influenced by substrate type, operational parameters such as temperature and organic loading rates (OLR), and reactor configuration [

39,

40]. However, most operational strategies still rely exclusively on physicochemical parameters, overlooking microbial signals that often precede system imbalances [

41]. Sequencing platforms like Illumina MiSeq and NextSeq have revealed both dominant and low-abundance taxa with key metabolic roles, including members of

Euryarchaeota involved in methanogenesis and syntrophic bacteria mediating VFA conversion [

40]. Understanding microbial shifts under stress conditions has provided valuable insights into process behavior and system dynamics, reinforcing the need to integrate microbial data into process understanding, particularly to elucidate how shifts in community structure and function impact methane levels [

42,

43].

Despite their central role in AD, MLR models have traditionally been developed using operational variables that capture external system conditions, parameters that are directly measurable or predefined during setup, while MC have often been treated as secondary inputs or excluded altogether. For example, recent studies have used MLR to predict specific methane production from dry AD of the organic fraction of municipal solid waste in pilot-scale plug-flow reactors. Six significant, mostly operational predictors were prioritized (VS, OLR, HRT, C/N ratio, lignin content, and VFA) via Pearson correlation and PCA. Simple regression showed low performance (R

2= 0.3), while the full MLR reached R

2= 0.91. A reduced model with four uncorrelated variables (VS, OLR, C/N ratio, lignin content) maintained strong accuracy (R

2= 0.87) with fewer inputs. [

44]. Similarly, MLR has been applied to predict VFA concentrations in AD of primary and secondary sludge using operational and physicochemical inputs. The model achieved R

2 values above 0.85 in several scenarios, offering high interpretability and low computational demand. Although less accurate than leading ensemble methods, MLR remains suitable for applications that require clear interpretation of variable influence [

45].

Unlike models based solely on operational parameters, an MLR model using the relative abundances of archaeal and bacterial OTUs predicted methane production rates in 149 anaerobic digesters, explaining 66% of the variance with a standard error of 0.12 LCH

4/L·day. Through the integration of PCA, ANOVA, and cubic smoothing, it captured operational effects such as ammonia toxicity and achieved R

2 values of 0.93 for biogas generation and 0.95 for COD removal across laboratory, pilot, and industrial scales, underscoring its worth in translating complex MC data into scalable process predictions. [

46].

Building on emerging evidence supporting the integration of microbial data into statistical modeling, this study evaluates the potential of MLR to predict methane concentrations in a low-cost, two-phase anaerobic digester treating PM and CD at laboratory scale. The work aligns with Sustainable Development Goal 7 by promoting accessible tools for energy recovery from organic waste.

This article is structured into four main sections. The Introduction outlines the context of AD in the Valle del Cauca region, highlighting environmental and operational challenges from agro-industrial organic waste, reviewing strategies to improve biogas systems, and emphasizing the need to integrate microbial data into predictive models. The Materials and methods detail the system setup, monitoring, sequencing, and the MLR approach used for variable selection and model construction. The Results and discussion section presents the modeling outcomes, identifies relevant predictors, and interprets their contribution to system behavior. The Conclusion summarizes the key findings and future perspectives for incorporating microbiota into data-driven frameworks for sustainable energy transitions.

2. Materials and Methods

This study aims to develop a predictive model for methane concentration based on a set of measurable variables, including VFAs, microbial populations, and operational parameters. This section first describes the dataset and the preprocessing steps undertaken. Subsequently, it details the initial linear modeling approach, followed by a feature selection process based on variable weighting to derive a simplified, yet robust, model. Finally, it presents the development of an adaptive predictive model using a moving window technique combined with a regularization method to prevent overfitting.

2.1. Substrate Selection

The substrates used in this study were fresh PM and CD. The inoculum, obtained from the same source as the manure, was included to ensure microbial compatibility with the feedstock. Both were collected at a small-scale pig farm located in the municipality of Florida, Valle del Cauca, where approximately 20 pigs are kept under semi-intensive conditions. Animal pens are washed twice daily, and the resulting wastewater, rich in organic matter, drains into a static open-air tank that served as the inoculum source. Fresh manure was manually collected after excretion using sanitized tools. CD were obtained from a medium-sized cassava starch-processing facility located in the rural area of Mandiba, Santander de Quilichao, Cauca. Processing nearly eight tons of cassava per day, the plant generates over two tons of lignocellulosic residue each week. This material was delivered in dry, milled form.

All samples were stored at 4 °C until physicochemical characterization, which included proximate analysis by gravimetric methods and determination of the carbon-to-nitrogen (C:N) ratio via high-temperature combustion. These procedures followed the Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater (APHA, AWWA, WEF), ensuring analytical consistency as summarized in

Table 1 [

47].

2.2. Experimental Setup

The experimental setup consisted of a two-phase laboratory-scale anaerobic digester designed to operate without integrated control systems

Figure 1. The system was constructed using 110 mm sanitary-grade PVC tubing due to its low cost, durability, and ease of assembly. Phase 1 (D1F1) (3 L) was expected to perform hydrolysis and acidogenesis, while phase 2 (D1F2) (4 L) supposedly supported acetogenesis and methanogenesis. Each chamber was operated at 80% of its total volume, 2.4 L in phase 1 and 3.2 L in phase 2, leaving the remaining headspace for biogas accumulation. To enable real-time monitoring, a low-cost IoT module was incorporated into the digester, integrating an Arduino UNO microcontroller with sensors for pH, temperature, and methane concentration. Data were transmitted through a mobile network to the ThingSpeak platform for remote visualization [

38]. This setup allowed continuous monitoring without the need for sophisticated instrumentation.

2.3. Operational Parameter

To establish an active MC, both phases were fed inoculum for five days, until its working volume. The inoculum had a C:N ratio of 10.3 and 2.2% TS. During start-up, the OLR, estimated with a five-day HRT, was 8.37 gVS/L·day. Thereafter, feeding used a 73:27 blend of PM and CD. The daily feed was 35 g fresh PM and 13 g CD, plus 166 g water to achieve 10% TS (214 g/day total). The theoretical C:N ratio was 21.55. With the defined working volumes, HRTs were 12 days for D1F1 and 15 days for D1F2. Corresponding OLRs were 7.7 and 5.7 gVS/L·day. VS inputs were 18.46 g/day (D1F1) and 18.45 g/day (D1F2). Daily manual feeding with graduated containers and isolation valves ensured accurate dosing and anaerobiosis.

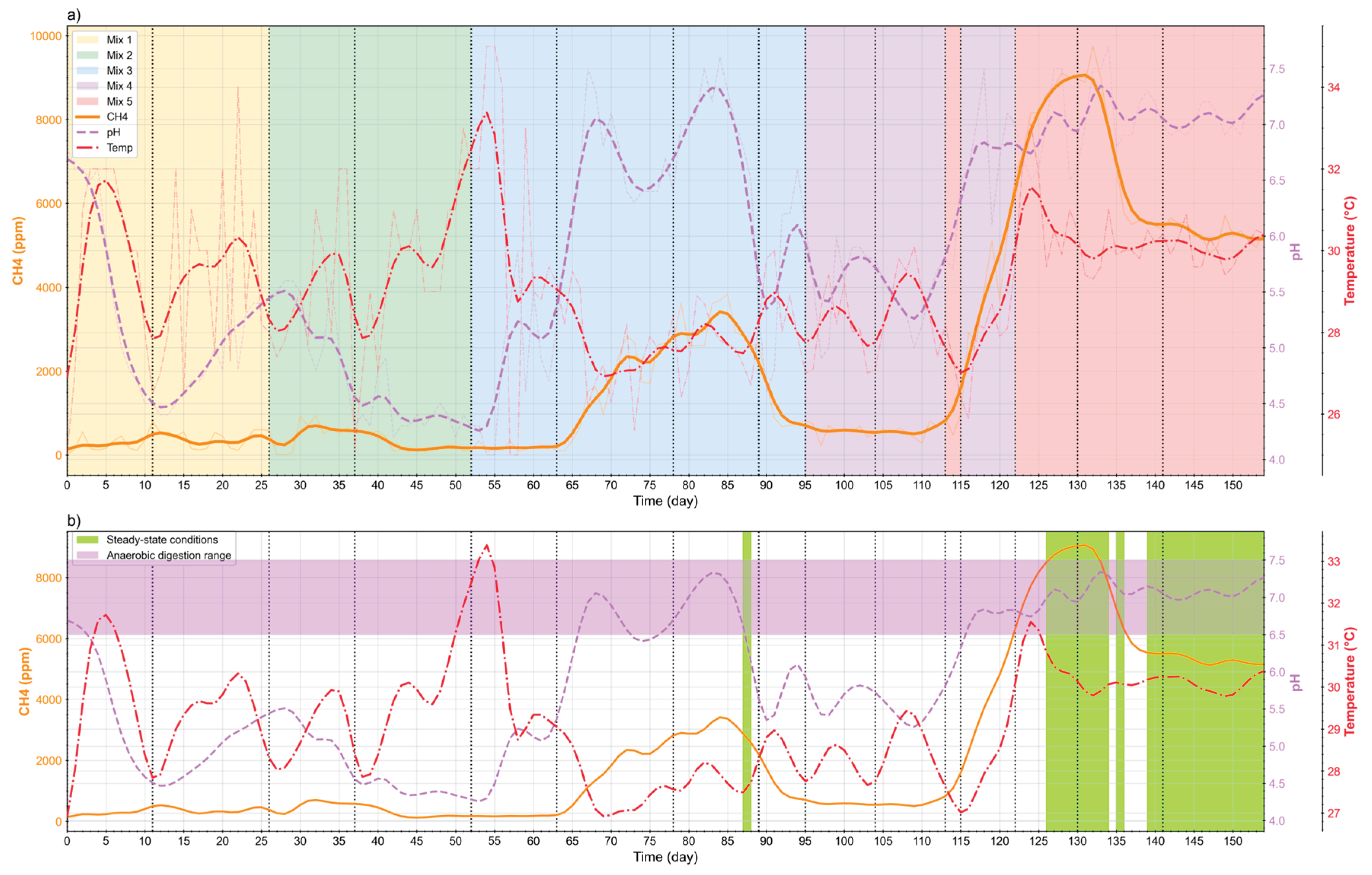

The IoT-instrumented digester (D1) enabled incremental, data-driven feed adjustments in both phases (D1F1, D1F2) using real-time pH, temperature, and methane concentration. These signals guided when to lower the OLR and TS and when to apply temporary pH control, moving the reactors toward consistent operating conditions. Five feed formulations were implemented (

Table 2). In D1F1, pH was briefly corrected with lime and then NaOH to keep it within 6.5–7.5; by mixture 5, recirculated digestate from D1F2 maintained pH without further chemicals. Mixture 4 used inoculum from an anaerobic digester at a university in Colombia treating food waste. Across mixtures, TS was reduced from 10% to 8–9%, OLR decreased from 12.4 gVS/L·day (inoculum step) to 5–6 gVS/L·day, and the C:N ratio increased in the final mixture due to recirculation while the contributions of PM and CD were reduced.

2.4. Steady-State

Identifying steady-state periods was essential to build a reliable dataset, define representative operating conditions, and guide downstream variable prioritization and modeling. pH, temperature, and methane concentration were monitored continuously for 161 days (24/7). The IoT system logged three readings per minute for each variable and was routinely cross-checked against bench measurements to validate operational reliability.

Data volume was substantial, D1F1 recorded 694110 samples per variable and D1F2 573215. Processing followed six steps: 1) splitting timestamp into date and time; 2) validity filtering (e.g., pH 3–12; 10–45 °C; CH₄ within instrument bounds) with out-of-range values set to blank; 3) multivariate imputation by chained equations (MICE) to preserve temporal continuity [

48]; 4) resampling to hourly means (2893 rows in D1F1; 2389 in D1F2) and 5) to daily means (152 and 147, respectively), retaining trends while reducing computational load as shown in

Table 3.

Stable windows were then identified via rolling windows using relative standard deviation thresholds (<15%) around moving means for pH, temperature, and methane concentration, with a minimum continuous duration and compliance with predefined operating limits [

49]. D1 showed extended steady windows, typically with pH 6.5–7.5, facilitated by high-frequency data and the ability to adjust operating conditions in real time.

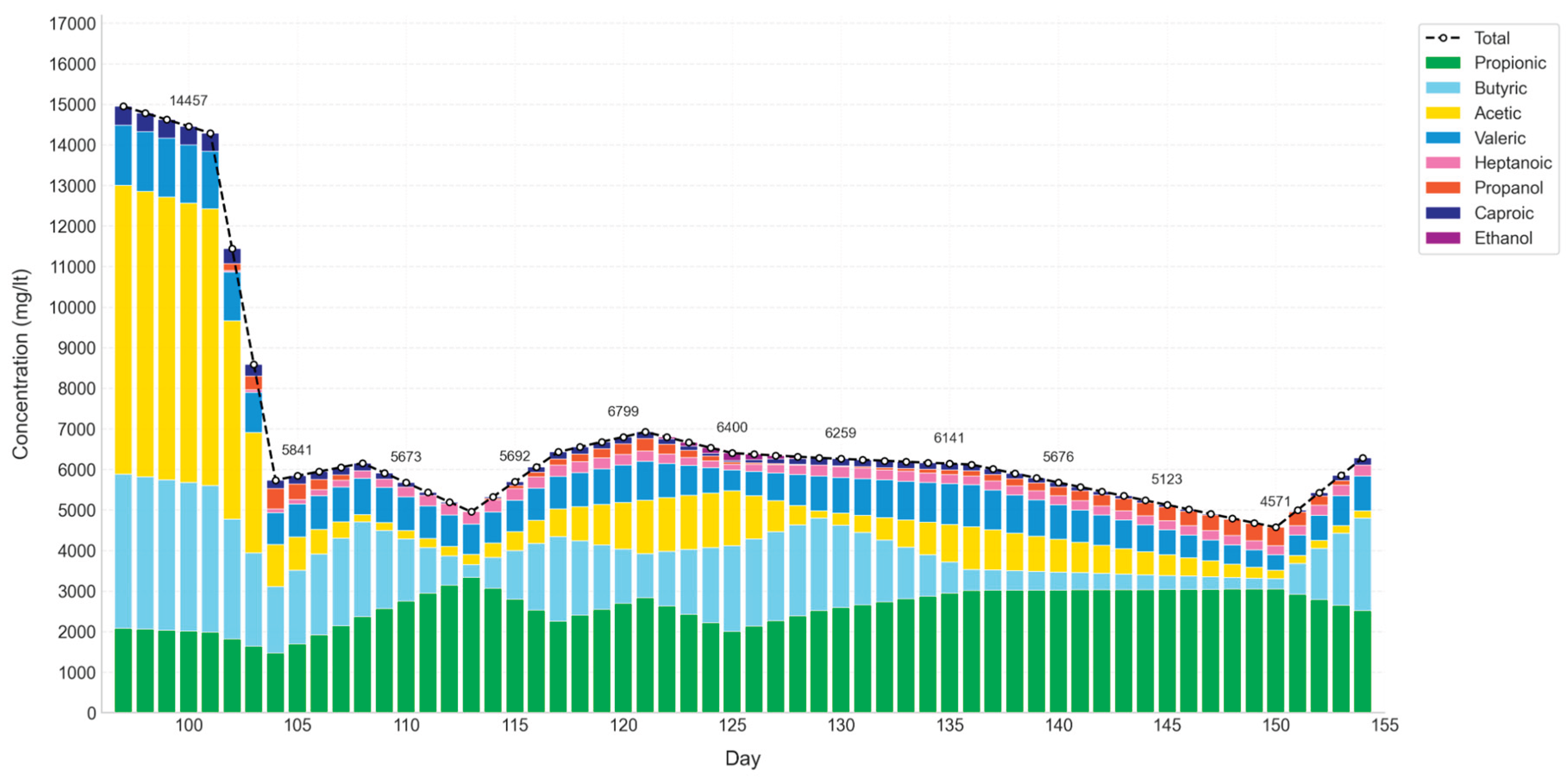

2.5. VFA Quantification

Samples were collected every three days in 5 ml Eppendorf tubes and stored at -20°C until analysis. The final selection of samples for analysis was made considering the periods of system stabilization under IoT monitoring and budgetary constraints, prioritizing those most representative of the overall process behavior. Sampling was carried out during the active operation of the digester.

The quantification of VFAs was performed by gas chromatography, following the procedure described in section 5560D of the Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater (APHA) [

50], in the laboratory of the Department of Chemical Engineering and Analytical Chemistry at the University of Barcelona. Prior to chromatographic analysis, the samples were centrifuged and filtered through 0.45 µm nylon membranes to remove suspended solids. Each analysis vial contained 1 ml of sample, diluted or not depending on the estimated concentration level, along with 0.1 ml of 15% orthophosphoric acid containing a known concentration of 2-ethylbutyric acid (~500 mg/L) as an internal standard. This compound allowed verification of injection consistency and facilitated calibration of the equipment through the ratio of analyte to standard peak areas.

Analyses were carried out on a Shimadzu GC-2010 Plus gas chromatograph with a flame ionization detector, using a DB-FFAP capillary column (Agilent Technologies, 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm). The oven temperature program started at 60°C with a two-minute hold, followed by an increase of 20°C/min up to 240°C, maintained for an additional two minutes. The total analysis time was 13 minutes.

The injector (SPL-1) operated at 220°C in split mode, with a split ratio of 50:1. Helium was used as the carrier gas at a pressure of 42.6 kPa, with a total flow of 233.4 ml/min, a column flow of 8.86 ml/min, and a linear velocity of 60 cm/s. The purge flow was set at 3 ml/min, and the makeup gas flow (nitrogen) at the detector was 10 ml/min. The injection volume was 2 ml, using helium, air, hydrogen, and nitrogen as auxiliary gases.

For equipment calibration, a commercial VFA standard (Supelco CRM46975) containing defined concentrations of acetic, propionic, isobutyric, butyric, isovaleric, valeric, isocaproic, caproic, hexanoic, and heptanoic acids was used. Serial dilutions were prepared in 1:1, 1:2, 1:4, 1:8, 1:16, and 1:32 ratios, to which orthophosphoric acid and the internal standard were also added. For alcohol analysis (ethanol, propanol, and butanol), defined-concentration standard solutions were prepared, applying the same dilutions and analytical conditions.

This procedure allowed precise and reproducible determination of VFAs in the samples, essential for evaluating the performance of the AD system and its relationship with operating conditions and microbiota.

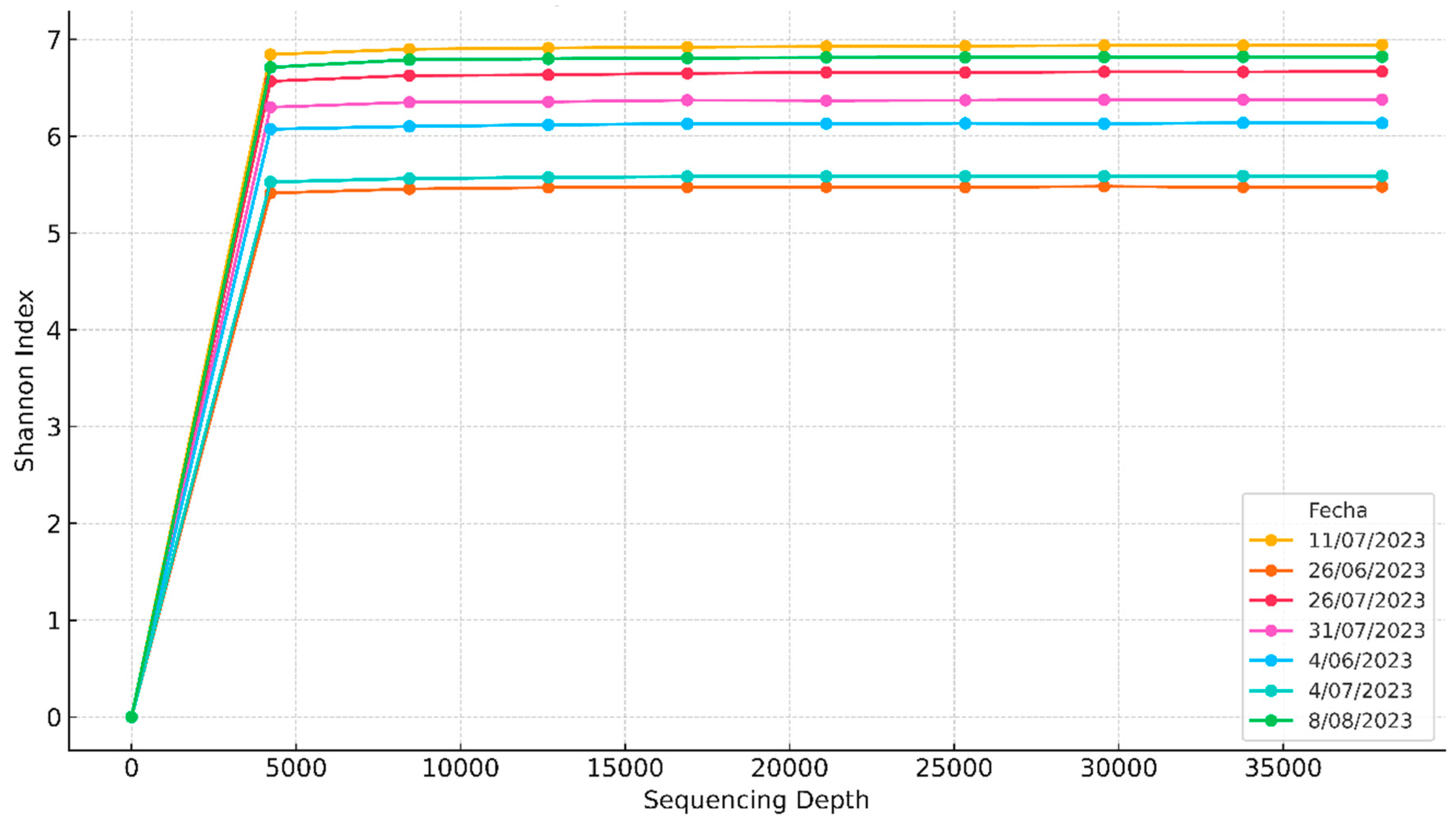

2.6. Metagenomic Analysis

Samples for metagenomic analysis were collected directly from operational biodigester using 50 ml Falcon tubes. Sampling was performed every three days throughout the process, following the same prioritization criteria used for the quantification of VFAs, focusing on periods of greatest microbiological representativeness and considering the availability of resources. Once collected, samples were immediately frozen at -20°C and stored until further processing.

To analyse the MC, Falcon tubes were sent to Omega Bioservices (U.S.A) for DNA extraction using the kit E.Z.N.A.® Universal Pathogen Kit, library preparation and for sequencing the V3–V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene using the primers 341F (CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG) and 806R (GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC) which was conducted on an Illumina Miseq sequencing platform (Paired-end sequencing 300 bp). Illumina reads were then analysed using BaseSpace app (version 1.1.3) [

51]. Thus, raw sequence data were demultiplexed and then quality filtered, denoised, merged, and chimera removed using the DADA2 [

52] to generate amplicon sequence variants (ASVs). Taxonomic assignment was conducted using the SILVA database (version 138.2) [

53].

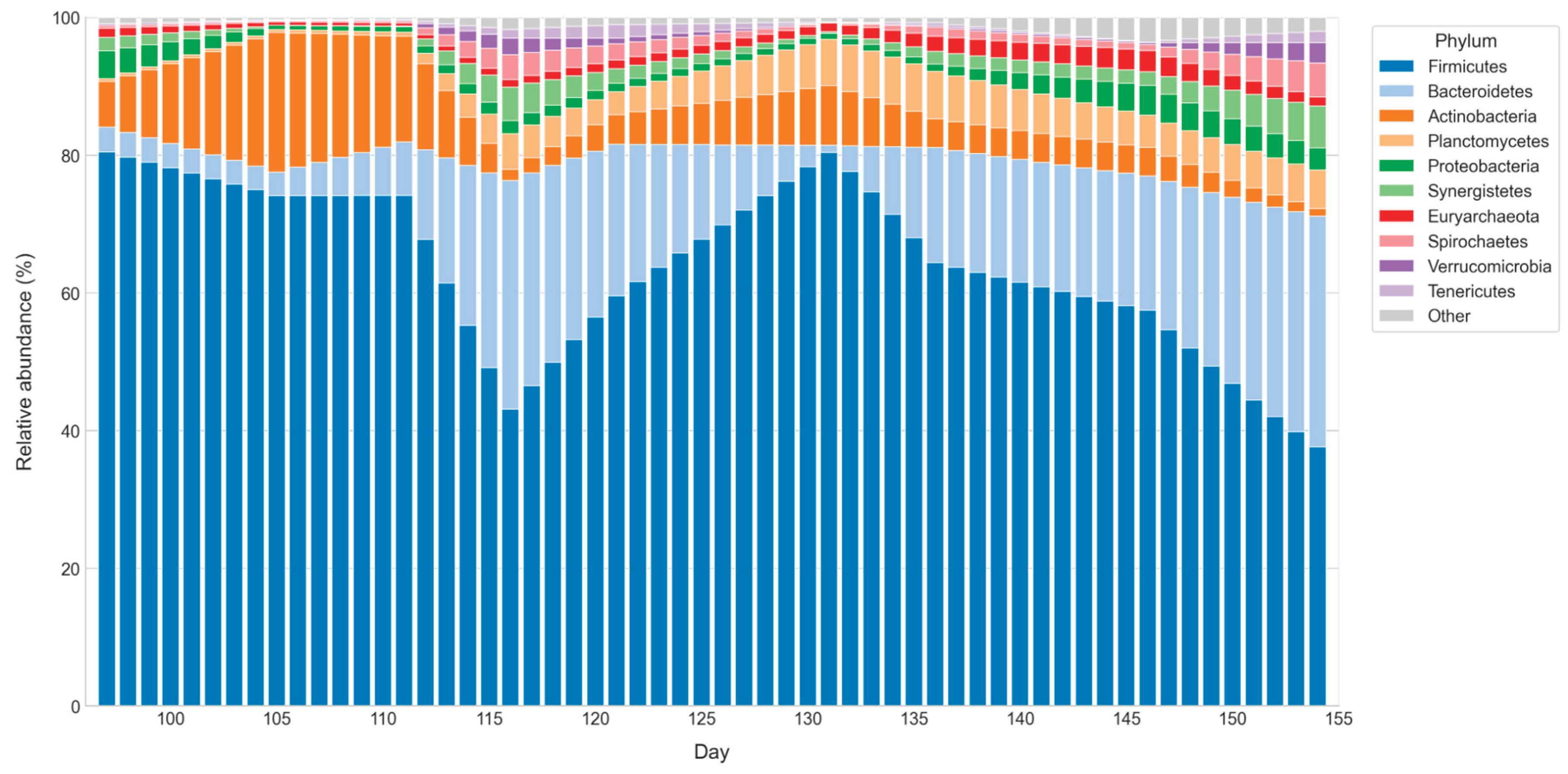

To structure the analysis of microbial interactions, a subset of phyla of interest was defined from the general metagenomic dataset, considering the sequencing reads obtained for each taxonomic group. The selection was based on two main criteria. First, the sustained presence of each phylum throughout the monitoring period was evaluated, excluding those with very low or intermittent representation, as their variability would hinder the detection of consistent associations in the relational analysis. Second, functional relevance reported in previous studies on anaerobic digestion was reviewed, prioritizing phyla whose involvement in fermentative, acetogenic, or methanogenic pathways has been extensively documented in similar systems [

9,

54].

Once the representative periods were defined, the results from VFA quantification and metagenomic analysis were integrated, extending the characterization to the biochemical and microbiological components of the system. In several cases, the observed patterns were consistent with those reported in the specialized literature, which supported the robustness of the approach. The dataset included operational, biochemical, and microbiological variables [

55,

56,

57,

58,

59].

Since the biochemical and microbiological measurements were less frequent than the operational records, imputation techniques were applied within the selected periods to expand the dataset without distorting the relationships among variables. Methods such as KNN imputation, iterative imputation, and MICE were employed [

56,

60].

The analysis focused on the period between days 97 and 154, which, although not representing a fully stabilized phase, shows a trend toward stabilization and coincides with the selected VFA and microbiological samples. This ensured consistency between the experimental data and the operational conditions.

2.7. Preprocessing and Unified Database

Once the representative periods were defined, the results from VFA quantification and metagenomic analysis were incorporated to extend the characterization of the system to its biochemical and microbiological dimensions. The patterns obtained aligned with those reported in specialized literature, reinforcing the validity of the approach [

55,

56,

57,

58,

59]. The unified dataset combined operational, biochemical, and microbiological variables.

Because biochemical and microbiological measurements were less frequent than operational records, imputation method MICE was applied to harmonize the dataset without altering the underlying relationships among variables [

56,

60].

The analysis focused on the period between days 97 and 154, which, while not fully stabilized, displayed a clear trend toward steady performance and coincided with the VFA and microbiological samples selected. This ensured coherence between experimental observations and operational conditions. The resulting dataset comprised daily averages over 58 days, which were further refined through linear interpolation to increase temporal resolution. This process expanded the series to 1000 points, enabling the application of moving window analyses, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

The interpolation was validated for all variables, yielding R² values close to 1 and MRE values around 0.1%, confirming a high-fidelity representation of the original data.

2.8. Linear Modeling

To simplify the proposed equations and procedure, the suffixes associated with each fatty acid (

Table 4) microorganism (

Table 5), and operating condition (

Table 6) are shown below.

The equation (1) that linearly approximates

concentration as a function of the microorganisms, fatty acids, and operating conditions was proposed in the following linear form, based on the suffixes from

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6.

In its matrix form (matrix

), equation (1) can be expressed as follows (equation (2)):

where the constants

are the approximation coefficients. This matrix form from equation (2) can be written more compactly as shown in equation (3):

The matrix

contains data collected from fatty acids, microorganisms, and operating conditions, the vector

represents the collected methane production data, while the vector

contains the approximation coefficients that must be determined to formulate the model. The vector

, can be solved by rearranging equation (3) as follows:

where

is the transpose of matrix

.

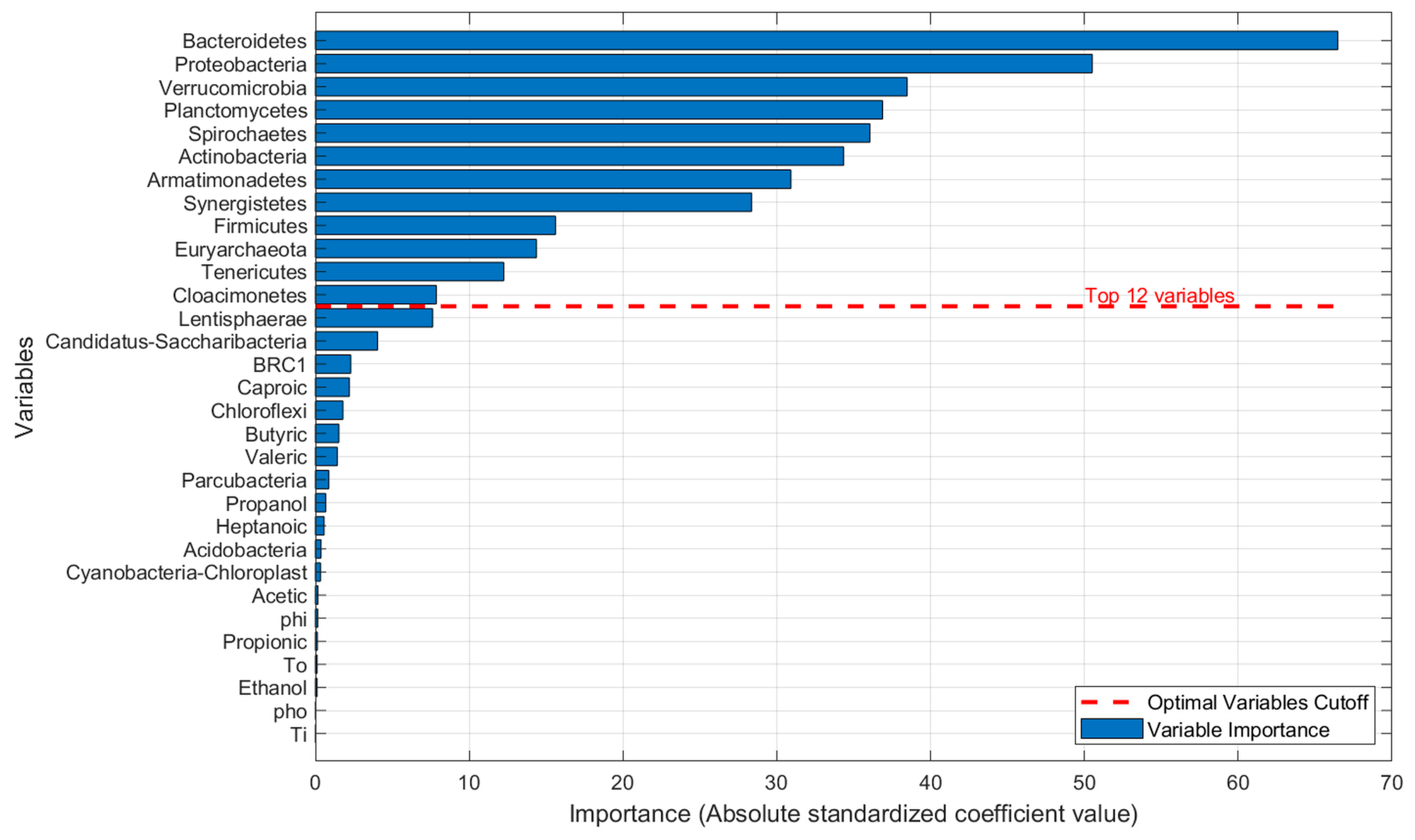

2.8.1. Assessing Variable Importance

To determine the relative importance of each variable in the approximation, and subsequently define a smaller, more practical subset (as working with all 31 variables can be impractical and costly in terms of laboratory testing), a variable weighting method was used. Therefore, equation (5) appears as a modification of the equation (3) considering the minimal error

.

To quantify how much each variable "contributes" to the

production within the approximation, it is necessary to measure the relevance of each variable in the linear model. Since each variable may be measured on a different scale (e.g., microorganism abundance vs. fatty acid concentration in mg/L), directly comparing the raw coefficients

in vector

can be misleading. Therefore, it is necessary to standardize the input data. In the same way, to compare the relative importance of each variable, the coefficients

that form the vector

were standardized (as z-scores). The standardized coefficient

for each variable

was calculated as:

where

and

are the standard deviations of the approximation coefficient

and the response variable

, respectively.

2.8.2. Proposing a Predictive Model

To capture the evolutionary nature of the anaerobic digestion process, a dynamic predictive model was developed based on a moving windows approach. The model operates iteratively. At each time step , a linear regression model is trained using a window containing the last observations (in this case, was chosen). This model is then used to make a one-step-ahead prediction of (denoted as ), as a function of the weighted variables previously described.

However, the use of small data windows can lead to overfitting. To address this problem and improve the model's generalization capability, Ridge Regression was used instead of ordinary least squares. This regression introduces a penalty term into the least squares cost function. For each time window, the objective is to find the coefficient vector

that minimizes the following function:

where

is the sum of squared errors (the data fit term at time

),

is the regularization term applied at time

,

is the regularization hyperparameter that controls the balance between the data fit and the model simplicity, and

contains the coefficients

. The hyperparameter

was selected to improve the model predictive performance (

). Thus, equation (4) is rewritten to obtain the predictive parameters (

) by solving the following equation:

where

is the identity matrix. The goal of equation (8) is to find the value of the coefficients in vector

at time

using the data available at time

. Using equation (8), it is possible to find the

values for a subsequent window, given a defined window size of

. In this way, equation (3) becomes a prediction equation as follows:

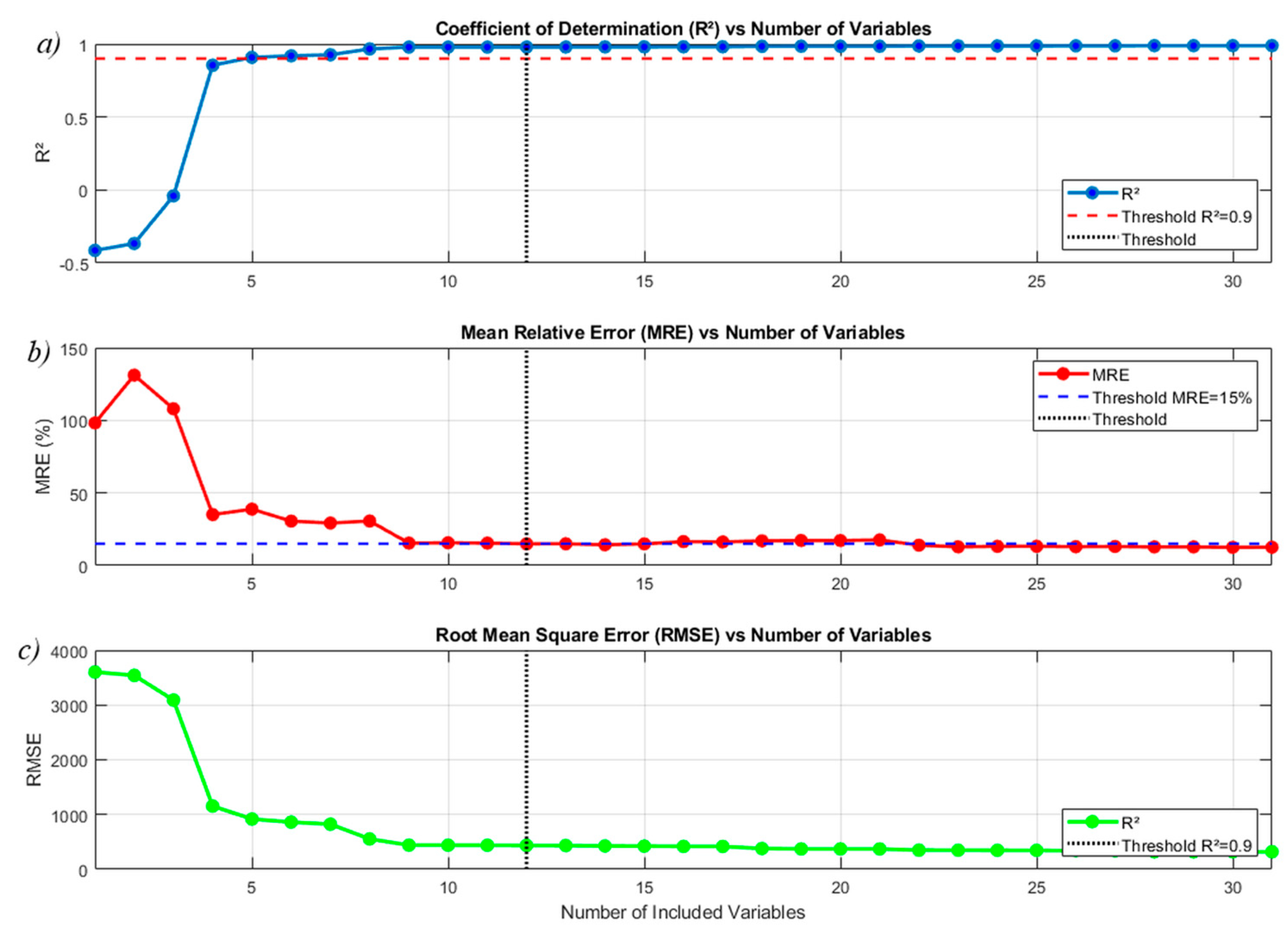

2.8.3. Model Performance Evaluation

The precision of the predictive model was quantified using three standard statistical metrics. These metrics evaluate the divergence between the real observed values of

and the values predicted by the model,

. On one hand, the Coefficient of Determination (

) indicates the proportion of the variance in methane production that is predictable from the independent variables. A value close to 1 indicates an almost perfect fit. Equation (10) shows how it was calculated for this case.

Next, the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) represents the standard deviation of the prediction residuals. It is a measure of the average error of the model in the same units as the response variable (ppm of

), which facilitates its interpretation and is expressed in equation (11).

Finally, the Mean Relative Error (MRE) measures the average error in relative or percentage terms with respect to the real value is defined in equation (12). The absolute value was used to prevent positive and negative errors from canceling each other out.

In equations (10), (11), and (12), is the real value of the i-th observation, is the value predicted by the model for the i-th observation, is the mean value of all real values, and n is the total number of observations used for the evaluation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.O. and I.R; methodology, I.O., I.R, and D.C.; software, I.O., I.R, and D.C.; validation, I.O., I.R, and L.M.F.; formal analysis, I.O., I.R, and D.C.; investigation, I.O., and I.R.; resources, I.O., I.R.; data curation, I.O., I.R, and D.C.; writing—original draft preparation, I.O., I.R.; writing—review and editing, I.O., I.R, and L.M.F.; visualization, I.O., I.R, and D.C.; supervision, L.M.F; project administration, I.O, L.M.F; funding acquisition, I.O., I.R, and L.M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Two-phase digester made of PVC.

Figure 1.

Two-phase digester made of PVC.

Figure 2.

Original (58 points) vs. interpolated (1000 points) time-series data for CH4 concentration.

Figure 2.

Original (58 points) vs. interpolated (1000 points) time-series data for CH4 concentration.

Figure 3.

D1F1 operation during 24 hours on random days.

Figure 3.

D1F1 operation during 24 hours on random days.

Figure 4.

D1F2 operation during 24 hours on random days.

Figure 4.

D1F2 operation during 24 hours on random days.

Figure 5.

a) Mixture feeding over time b) Steady-state identification.

Figure 5.

a) Mixture feeding over time b) Steady-state identification.

Figure 6.

VFA and alcohol concentration in D1.

Figure 6.

VFA and alcohol concentration in D1.

Figure 7.

Alpha rarefaction curves of the alpha diversity (Shannon) of the 16S rRNA gene.

Figure 7.

Alpha rarefaction curves of the alpha diversity (Shannon) of the 16S rRNA gene.

Figure 8.

Temporal dynamics of microbial phyla in D1.

Figure 8.

Temporal dynamics of microbial phyla in D1.

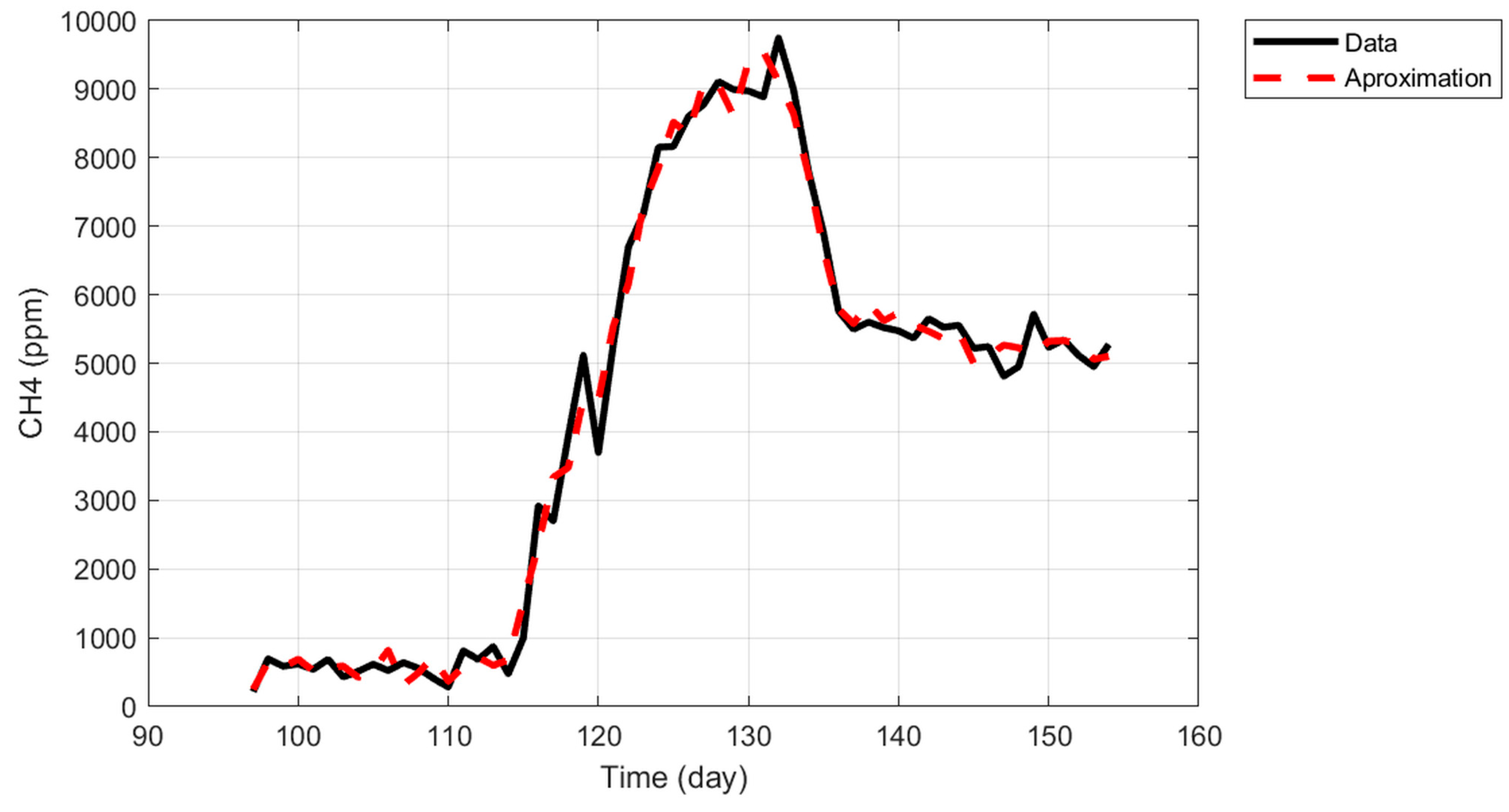

Figure 9.

Approximation result.

Figure 9.

Approximation result.

Figure 10.

Relative variable importance with defined cut-off.

Figure 10.

Relative variable importance with defined cut-off.

Figure 11.

a) , b) MRE and c) RMSE vs Number of included variables in the approximation.

Figure 11.

a) , b) MRE and c) RMSE vs Number of included variables in the approximation.

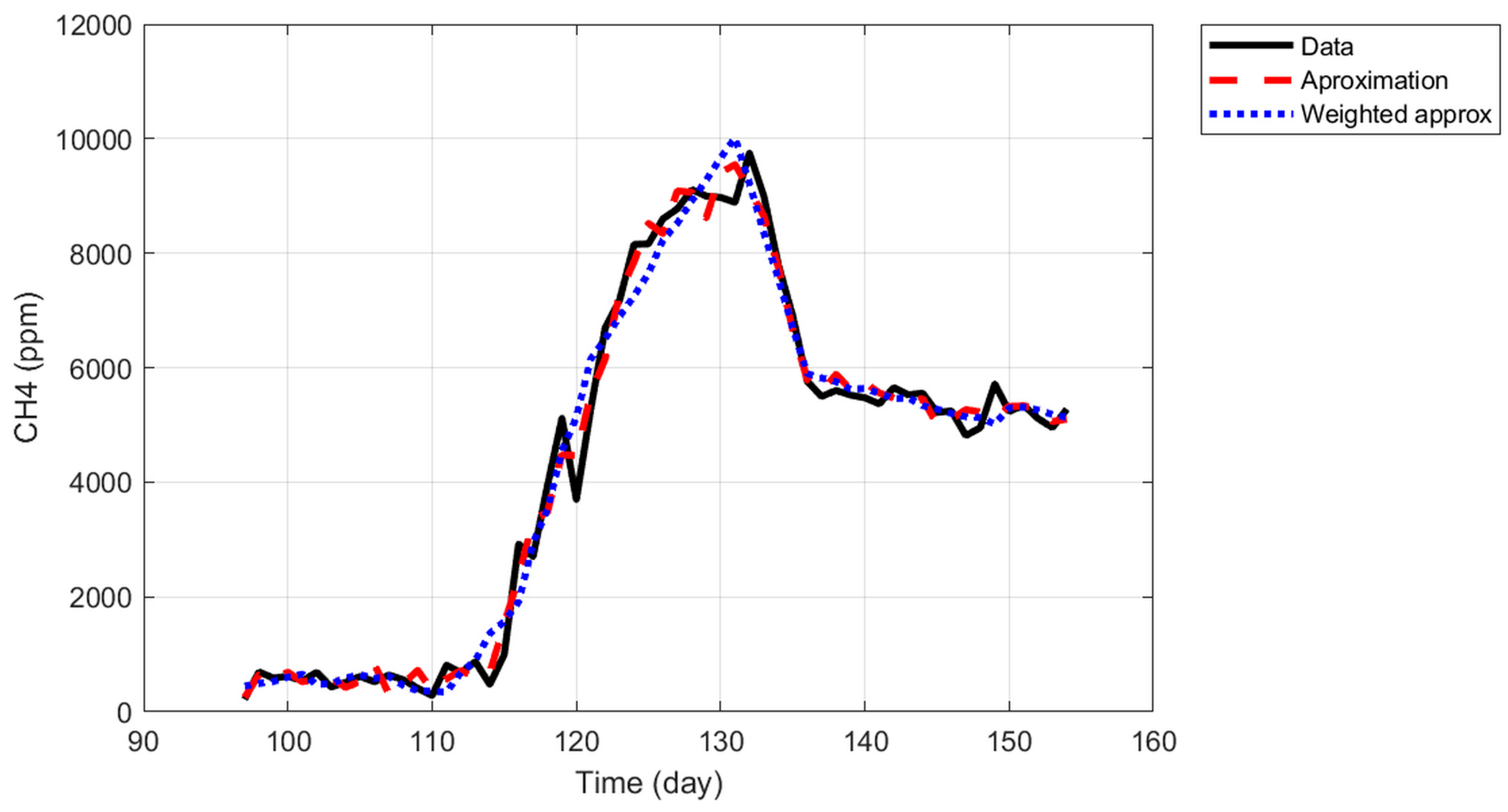

Figure 12.

Weighted approximation.

Figure 12.

Weighted approximation.

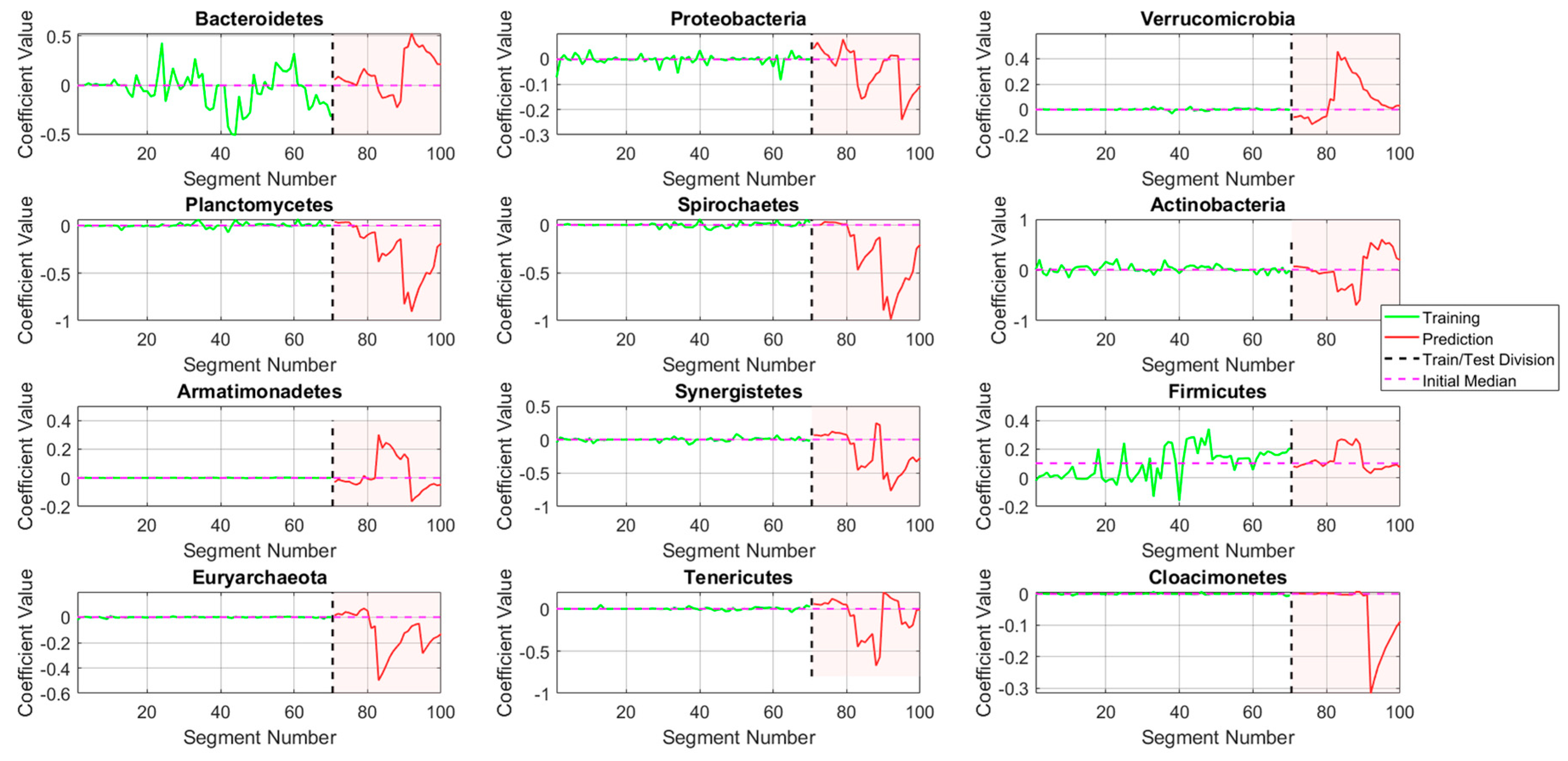

Figure 13.

Behavior of the coefficients associated with the weighted variables.

Figure 13.

Behavior of the coefficients associated with the weighted variables.

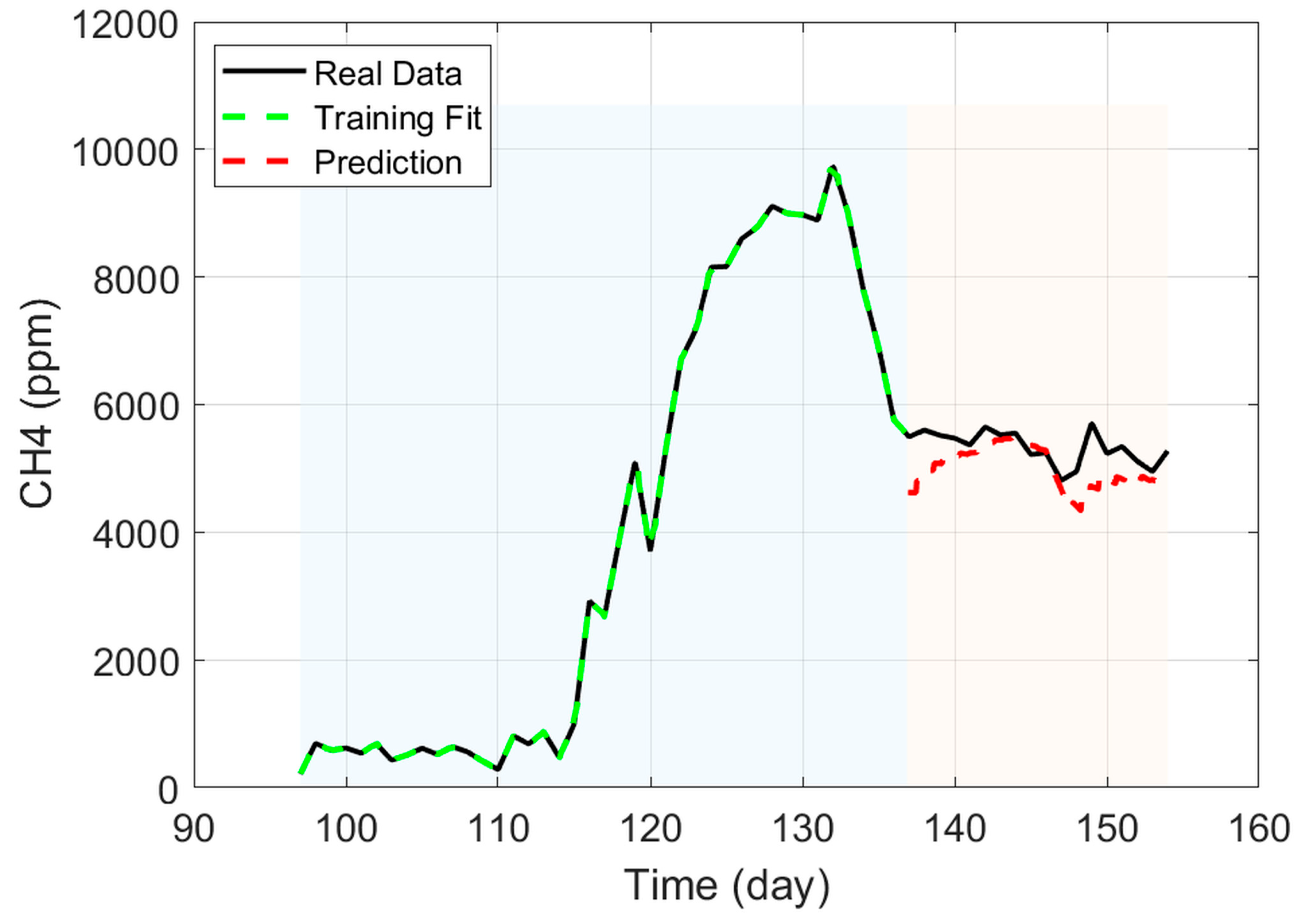

Figure 14.

Methane prediction and training data.

Figure 14.

Methane prediction and training data.

Table 1.

Substrate characerization.

Table 1.

Substrate characerization.

| Substrate |

C(%) |

N(%) |

C:N |

%Hum. |

%TS |

%VS |

%VS/%TS |

%FS |

| I |

32.9 |

3.2 |

10.3 |

98.0% |

2.2% |

1.3% |

60.8% |

0.9% |

| CD |

43.1 |

0.9 |

45.9 |

11.0% |

89.0% |

85.4% |

96.0% |

3.6% |

| PM |

12.9 |

1.9 |

7.0 |

72.0% |

28.0% |

21.0% |

75.0% |

7.0% |

Table 2.

Adjusted feeding regime.

Table 2.

Adjusted feeding regime.

| D1F1 |

|---|

| Mix |

OLR (gVS/L·day) |

Mix load (g) |

I (g) |

PM (g) |

CD (g) |

H2O added (g) |

Daily load (g) |

%TS |

C:N |

%I |

%PM |

%CD |

HRT (day) |

Period (day) |

pH treatment |

| I |

12.40 |

329 |

329 |

|

|

152 |

481 |

10% |

10.3 |

100% |

0% |

0% |

5 |

0-.5 |

|

| 1 |

7.67 |

48 |

|

35 |

13 |

166 |

214 |

10% |

21.6 |

0% |

73% |

27% |

11 |

6-27 |

Lime |

| 2 |

7.66 |

54 |

|

43 |

11 |

164 |

218 |

10% |

18.3 |

0% |

80% |

20% |

11 |

28-49 |

|

| 3 |

6.60 |

48 |

|

39 |

9 |

162 |

210 |

9% |

17.5 |

0% |

81% |

19% |

11 |

50-89 |

NaOH |

| 4 |

5.90 |

46 |

14 |

25 |

7 |

165 |

211 |

8% |

15.7 |

30% |

54% |

15% |

11 |

90-118 |

NaOH |

| 5 |

5.87 |

71 |

35 |

26 |

10 |

136 |

207 |

8% |

20.7 |

50% |

36% |

14% |

11 |

119-161 |

|

| D1F2 |

| I |

12.40 |

439 |

439 |

|

|

202 |

641 |

10% |

10.3 |

100% |

0% |

0% |

5 |

0-.5 |

|

| 1 |

5.75 |

48 |

|

35 |

13 |

166 |

214 |

10% |

21.6 |

0% |

73% |

27% |

15 |

6-38 |

|

| 2 |

5.74 |

54 |

|

43 |

11 |

164 |

218 |

10% |

18.3 |

0% |

80% |

20% |

15 |

39-60 |

|

| 3 |

4.95 |

48 |

|

39 |

9 |

162 |

210 |

9% |

17.5 |

0% |

81% |

19% |

15 |

61-100 |

|

| 4 |

4.41 |

46 |

14 |

25 |

7 |

165 |

211 |

8% |

15.7 |

30% |

54% |

15% |

15 |

101-127 |

|

| 5 |

4.40 |

71 |

35 |

26 |

10 |

136 |

207 |

8% |

20.7 |

50% |

36% |

14% |

15 |

128-161 |

|

Table 3.

Data processing.

Table 3.

Data processing.

| D1F1 |

|---|

| Steps |

pH |

T(°C) |

CH4

|

Total |

% |

| All data |

694110 |

694110 |

694110 |

2082330 |

100% |

| Day-hour |

694110 |

694110 |

694110 |

2082330 |

100% |

| Filters |

635953 |

635953 |

635953 |

1907859 |

92% |

| MICE |

694110 |

694110 |

694110 |

2082330 |

100% |

| Data per hour |

2893 |

2893 |

2893 |

8679 |

0.42% |

| Data per day |

152 |

152 |

152 |

456 |

0.02% |

| D1F2 |

| All data |

573215 |

573215 |

573215 |

1719645 |

100% |

| Day-hour |

573215 |

573215 |

573215 |

1719645 |

100% |

| Filters |

518897 |

518897 |

518897 |

1556691 |

91% |

| MICE |

573215 |

573215 |

573215 |

1719645 |

100% |

| Data per hour |

2389 |

2389 |

2389 |

7167 |

0.42% |

| Data per day |

147 |

147 |

147 |

441 |

0.03% |

Table 4.

List of associated suffixes for fatty acids (a).

Table 4.

List of associated suffixes for fatty acids (a).

| Acetic |

1 |

|

Caproic |

5 |

| Propionic |

2 |

|

Heptanoic |

6 |

| Butyric |

3 |

|

Ethanol |

7 |

| Valeric |

4 |

|

Propanol |

8 |

Table 5.

List of associated suffixes for microorganisms (m).

Table 5.

List of associated suffixes for microorganisms (m).

| Firmicutes |

9 |

|

Tenericutes |

19 |

| Bacteroidetes |

10 |

|

Armatimonadetes |

20 |

| Actinobacteria |

11 |

|

Cyanobacteria Chloroplast |

21 |

| Proteobacteria |

12 |

|

Acidobacteria |

22 |

| Planctomycetes |

13 |

|

Lentisphaerae |

23 |

| Synergistetes |

14 |

|

BRC1 |

24 |

| Spirochaetes |

15 |

|

Candidatus Saccharibacteria |

25 |

| Euryarchaeota |

16 |

|

Parcubacteria |

26 |

| Verrucomicrobia |

17 |

|

Chloroflexi |

27 |

| Cloacimonetes |

18 |

|

|

|

Table 6.

List of associated suffixes for operating conditions (p).

Table 6.

List of associated suffixes for operating conditions (p).

| phi |

28 |

|

pho |

30 |

| Ti |

29 |

|

To |

31 |

Table 7.

Approximation coefficients.

Table 7.

Approximation coefficients.

|

-0.25 |

|

84.58 |

|

0.72 |

|

152.94 |

|

4.86 |

|

-154.01 |

|

18.20 |

|

-112.07 |

|

-61.33 |

|

165.65 |

|

-22.60 |

|

60.94 |

|

-12.08 |

|

15.47 |

|

14.33 |

|

-302.56 |

|

7.39 |

|

159.10 |

|

-18.99 |

|

-450.57 |

|

-21.21 |

|

81.69 |

|

-161.69 |

|

116.88 |

|

-58.79 |

|

-1562.95 |

|

67.72 |

|

6.72 |

|

123.17 |

|

68.50 |

| |

|

|

242.54 |

Table 8.

Weighting parameters

Table 8.

Weighting parameters

|

66.48 |

|

2.21 |

|

50.51 |

|

1.79 |

|

38.48 |

|

1.53 |

|

36.87 |

|

1.43 |

|

36.06 |

|

0.88 |

|

34.35 |

|

0.67 |

|

30.92 |

|

0.57 |

|

28.37 |

|

0.37 |

|

15.61 |

|

0.34 |

|

14.37 |

|

0.17 |

|

12.25 |

|

0.15 |

|

7.87 |

|

0.13 |

|

7.63 |

|

0.11 |

|

4.04 |

|

0.11 |

|

2.30 |

|

0.01 |

| |

|

|

0.01 |

Table 9.

New weighted approximation coefficients.

Table 9.

New weighted approximation coefficients.

|

-4.64 |

|

63.94 |

|

-42.40 |

|

16.20 |

|

-94.76 |

|

1.70 |

|

-7.66 |

|

-7.10 |

|

64.88 |

|

-22.13 |

|

-4.02 |

|

251.39 |

Table 10.

Precision metrics for approximations and real data.

Table 10.

Precision metrics for approximations and real data.

| |

|

|

[ppm] |

| All variables |

0.989 |

12.59 |

319.94 |

| Weighted aproximation |

0.979 |

14.94 |

435.82 |

Table 11.

Evaluation of the training model and predictive model.

Table 11.

Evaluation of the training model and predictive model.

| |

|

|

|

| Training Fit |

0.999 |

0.35 |

20.77 |

| Prediction |

0.920 |

6.50 |

139.84 |