Submitted:

26 August 2025

Posted:

27 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

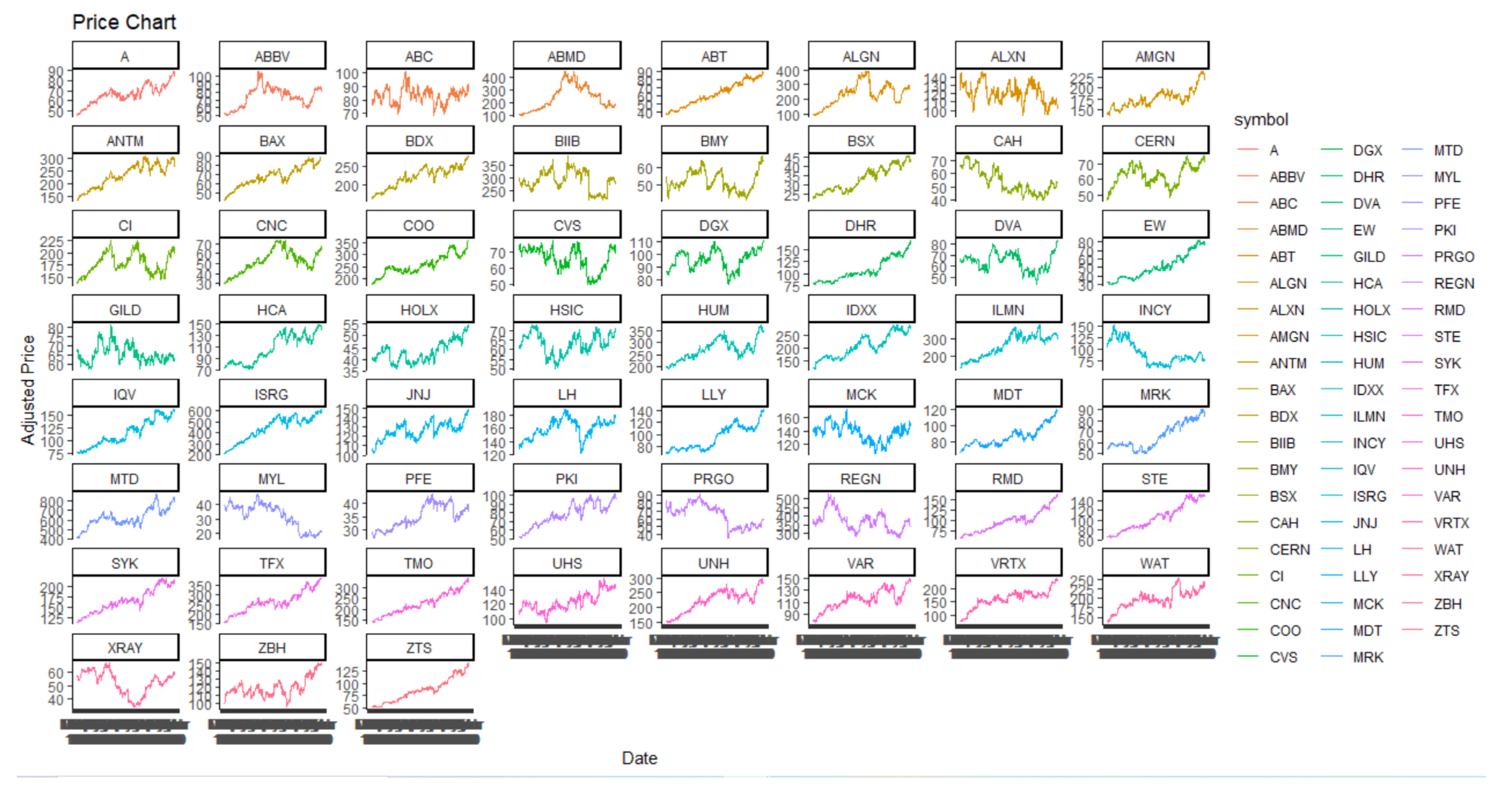

2. Materials and Methods

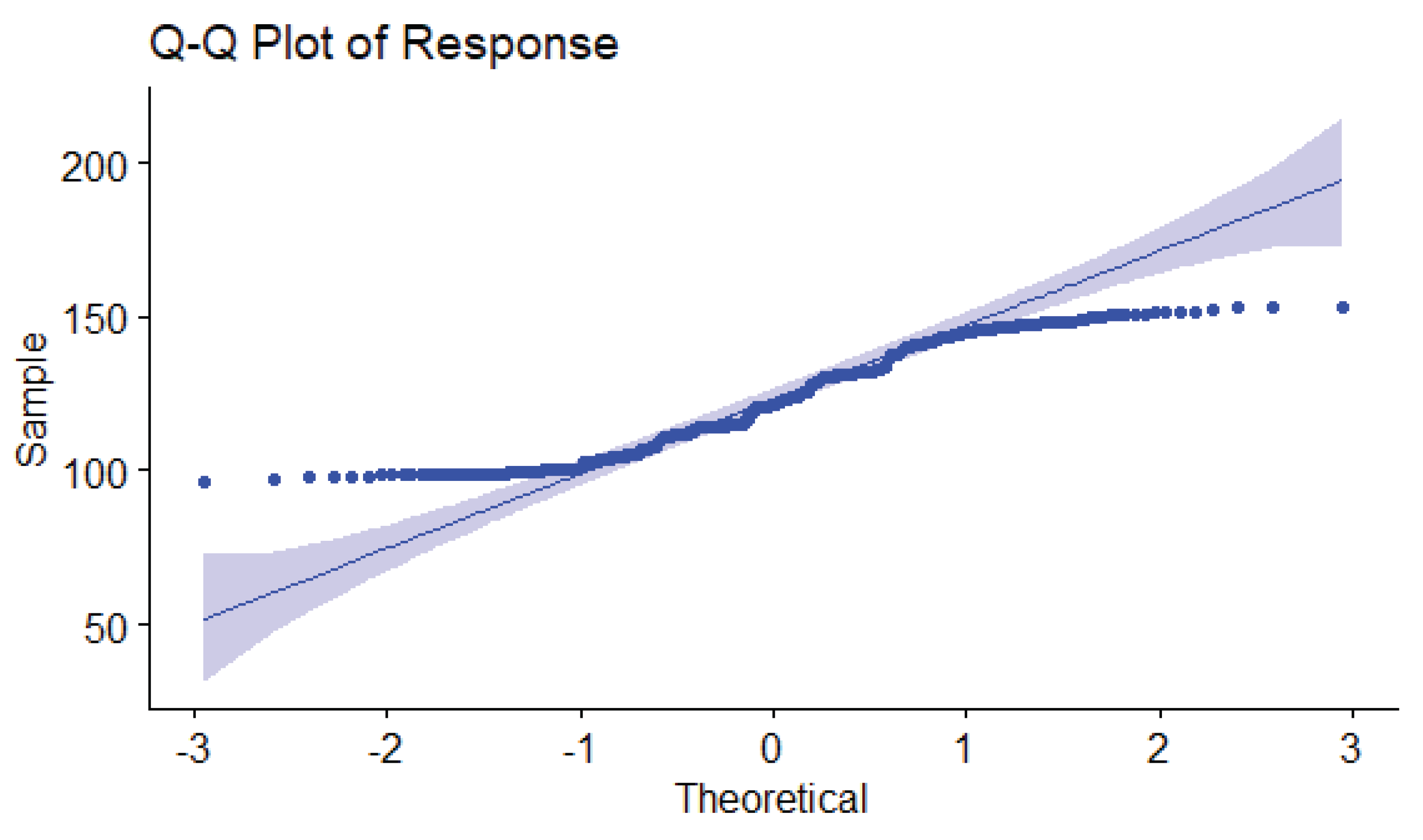

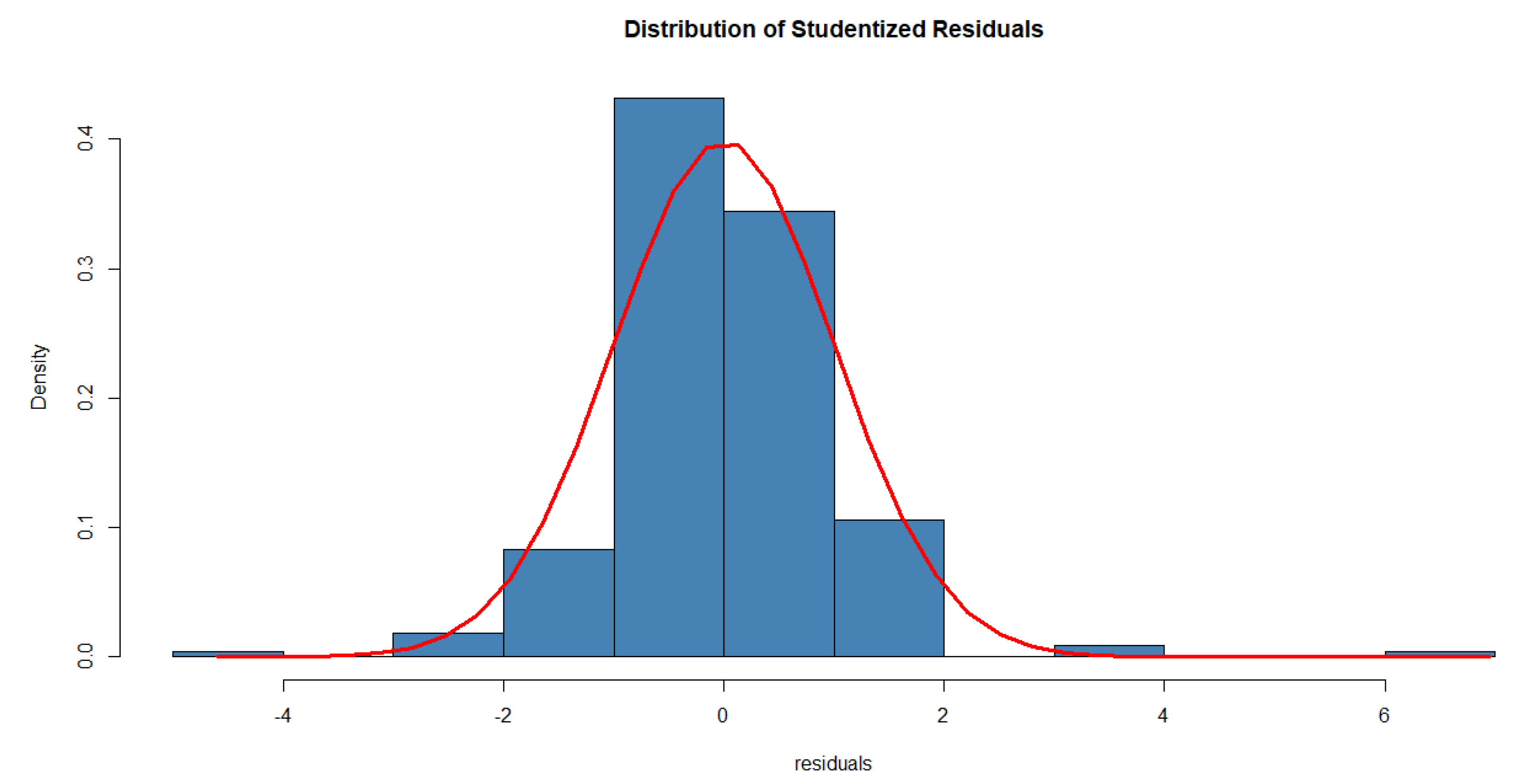

2.1. Model Diagnostics

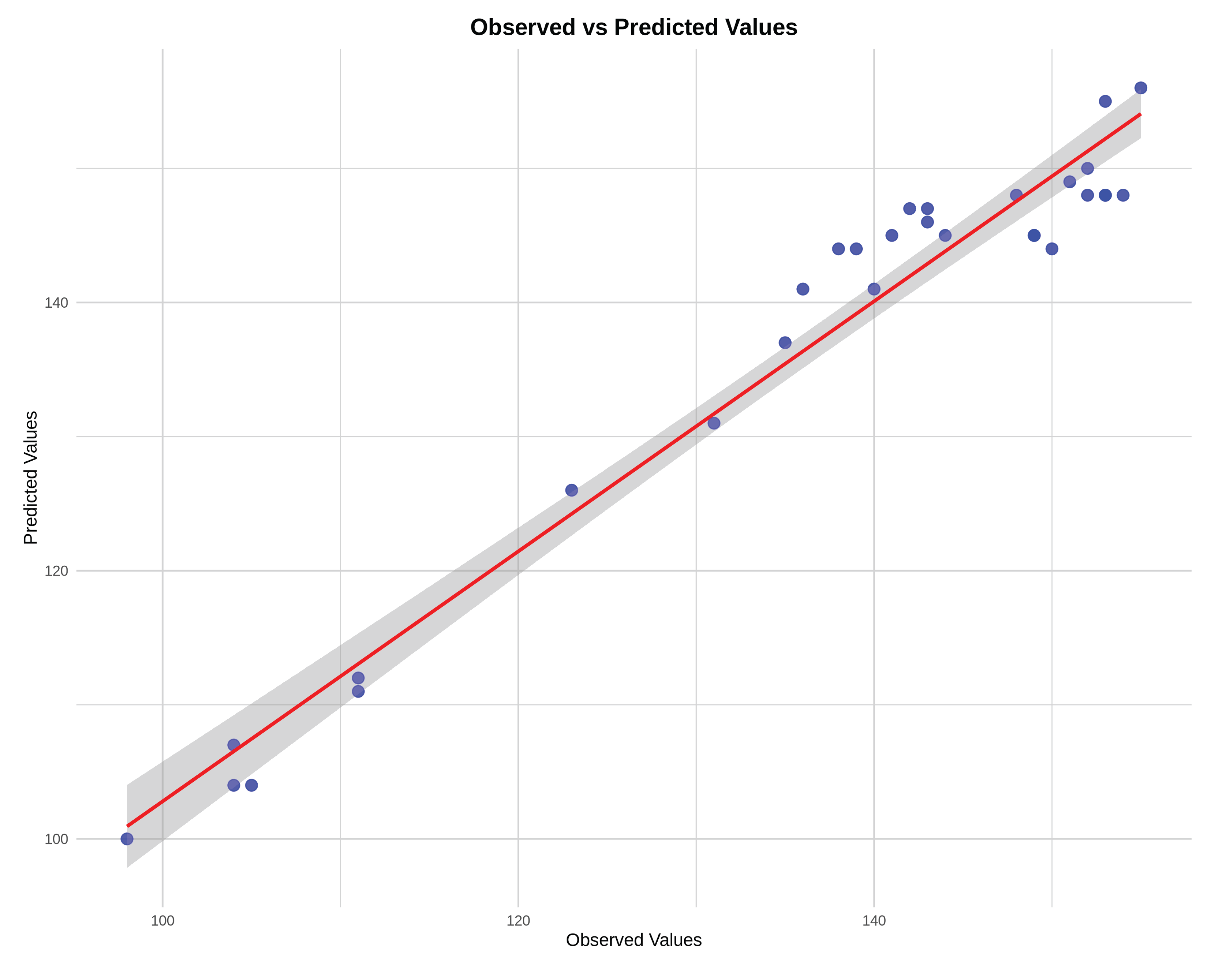

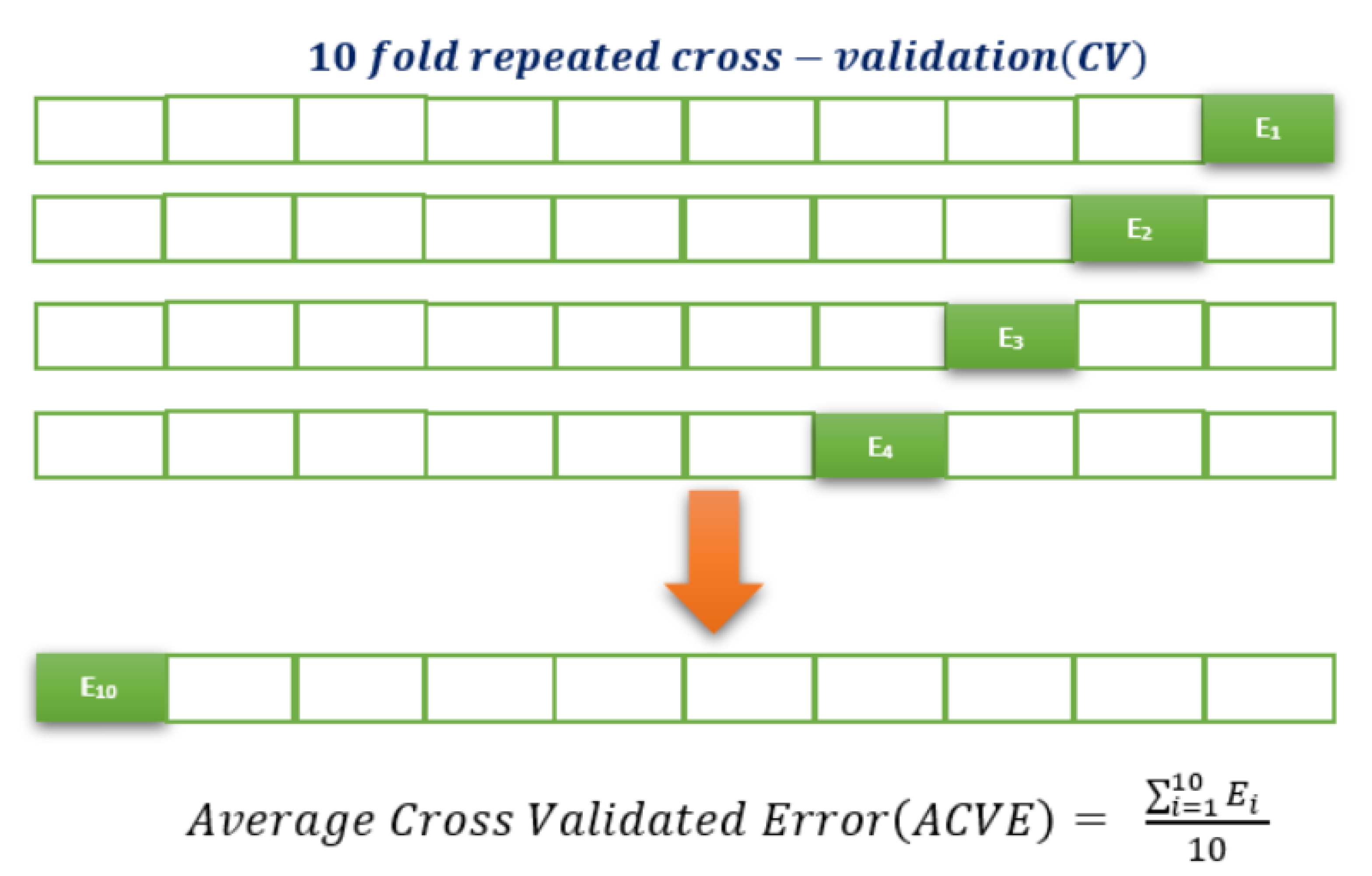

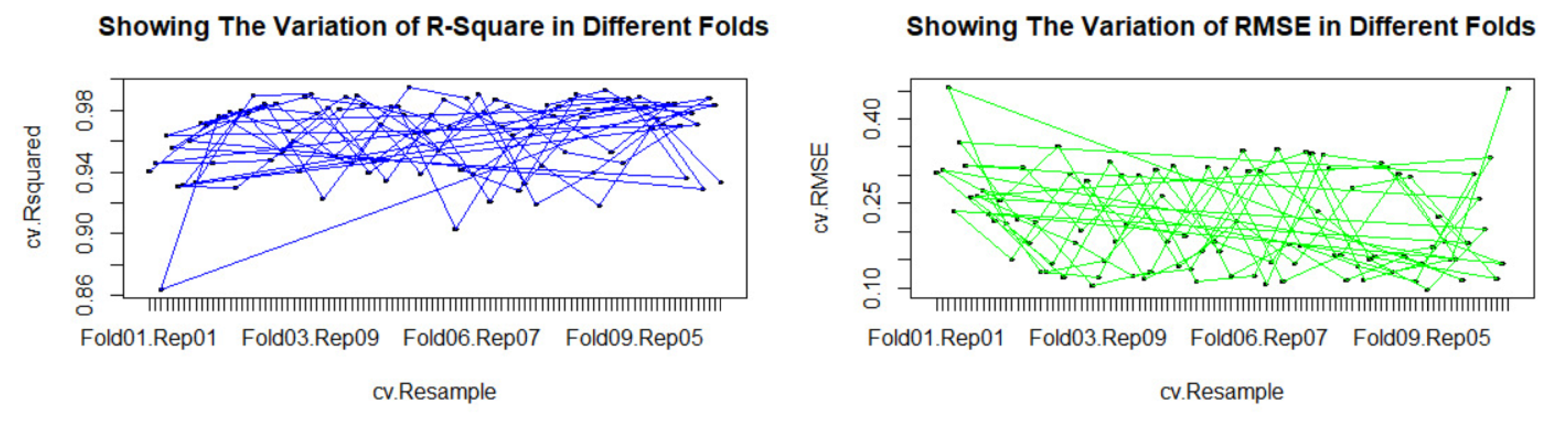

2.2. Validation of the Proposed Model

3. Analytical Method to Optimize the WCP of the HBS

3.1. Analytical Approach Using the Desirability Function

- Develop the statistical model that very accurately predicts the response, WCP, driven by a set of significant indicators.

- Obtain the constraints on input indicators, for and ; Y being the response and x being the indicators.

- Define the desirability function(s) for the response(s) based on the optimization objective.

- Obtain the optimal values of the response by maximizing the desirability function with respect to the controllable input indicators.

- Validate the optimization process based on the coefficient of variation and the .

3.2. Numerical Results

4. Discussion

- The individual, and interacting financial and economic indicators that significantly contribute to the price behavior of the healthcare business segment (HBS) of S&P 500 were identified via analytical modeling.

- The individual and interacting attributes were ranked with respect to their percentage of contribution to the WCP of the HBS of S&P 500. The precise ranking might be helpful in improving the forecasting models by incorporating accurate and robust predictions regarding future economic and financial market conditions.

- The developed non-linear analytical model was validated, and found to be consistent with ( = 96.74% and adjusted = 96.03% ) the test dataset, justifying the model’s applicability to any of the other eleven segments of S&P 500.

- The analytical optimization process (using the desirability function) was utilized to determine the optimal values of the indicators that maximize the WCP of the HBS. These values were determined with at least 95% confidence.

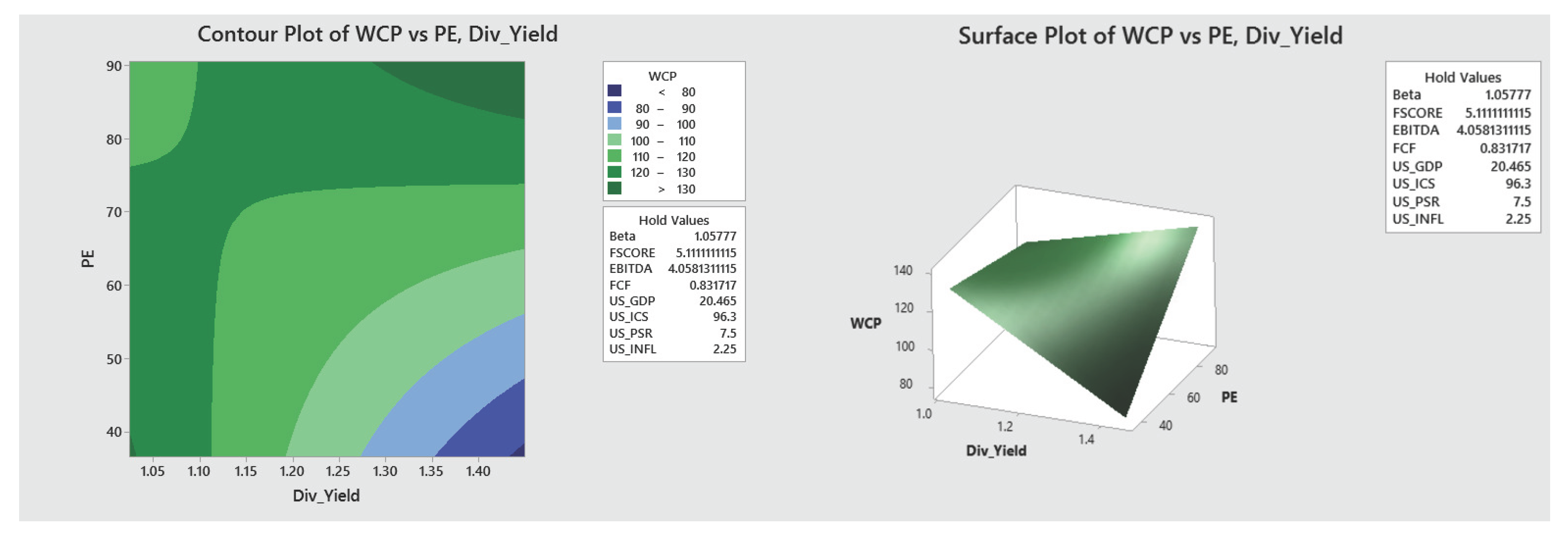

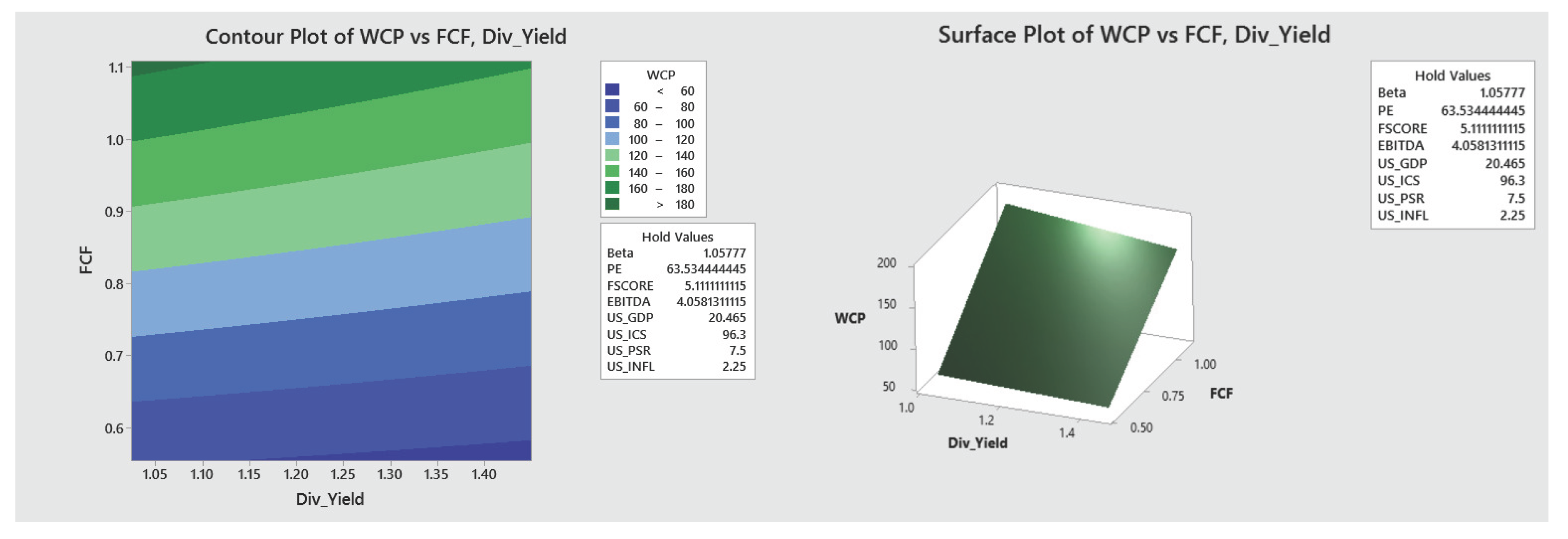

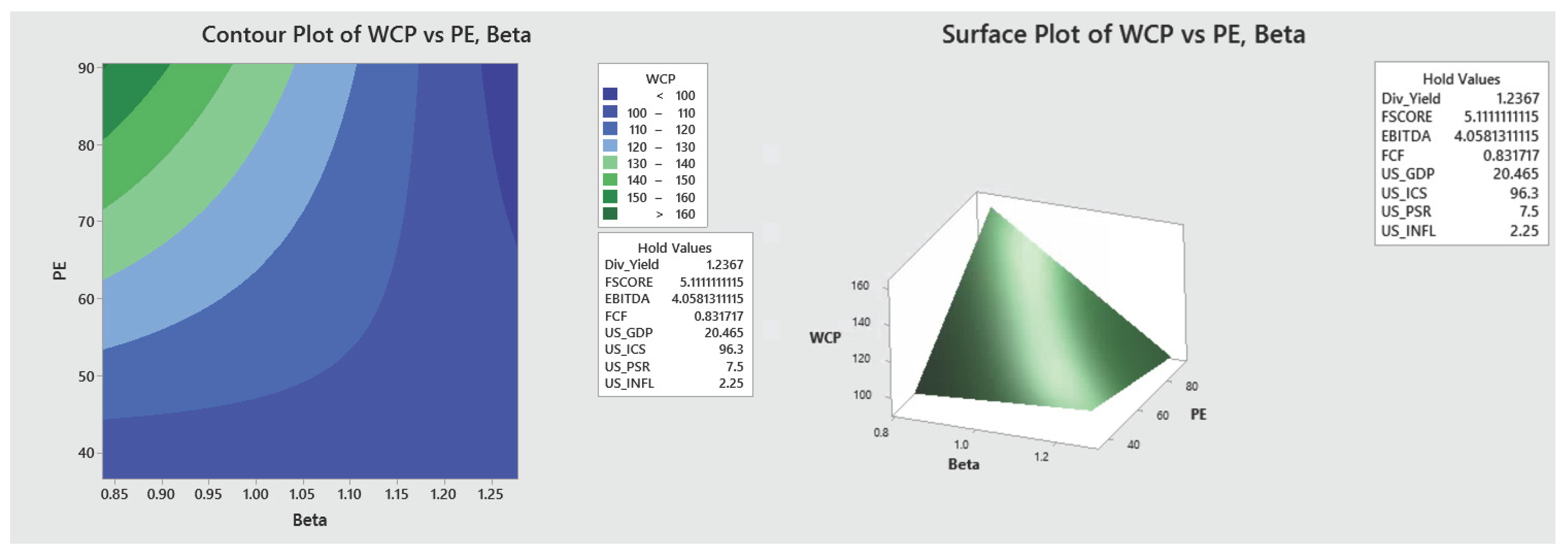

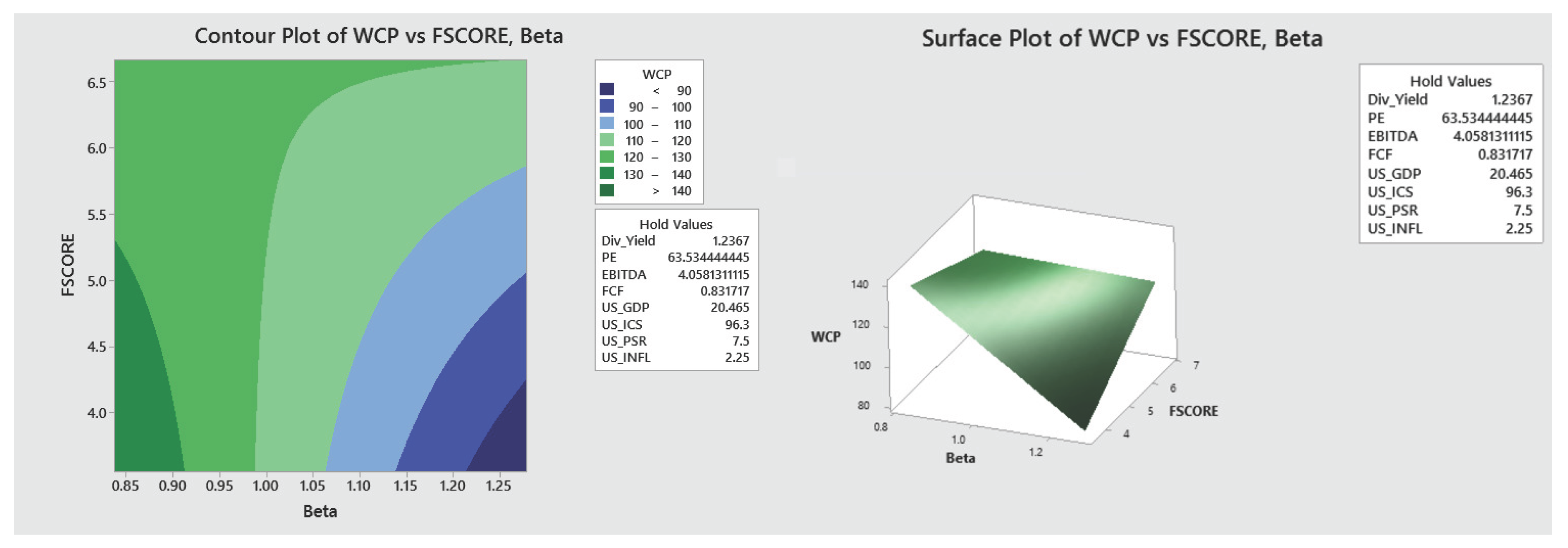

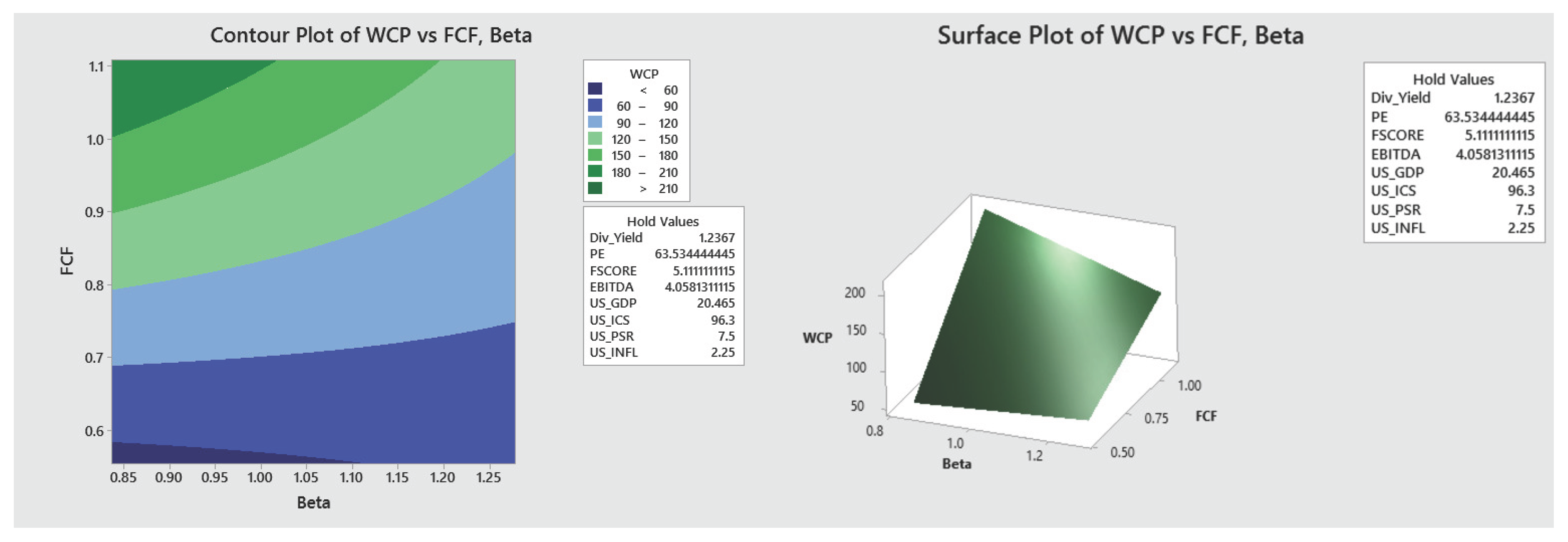

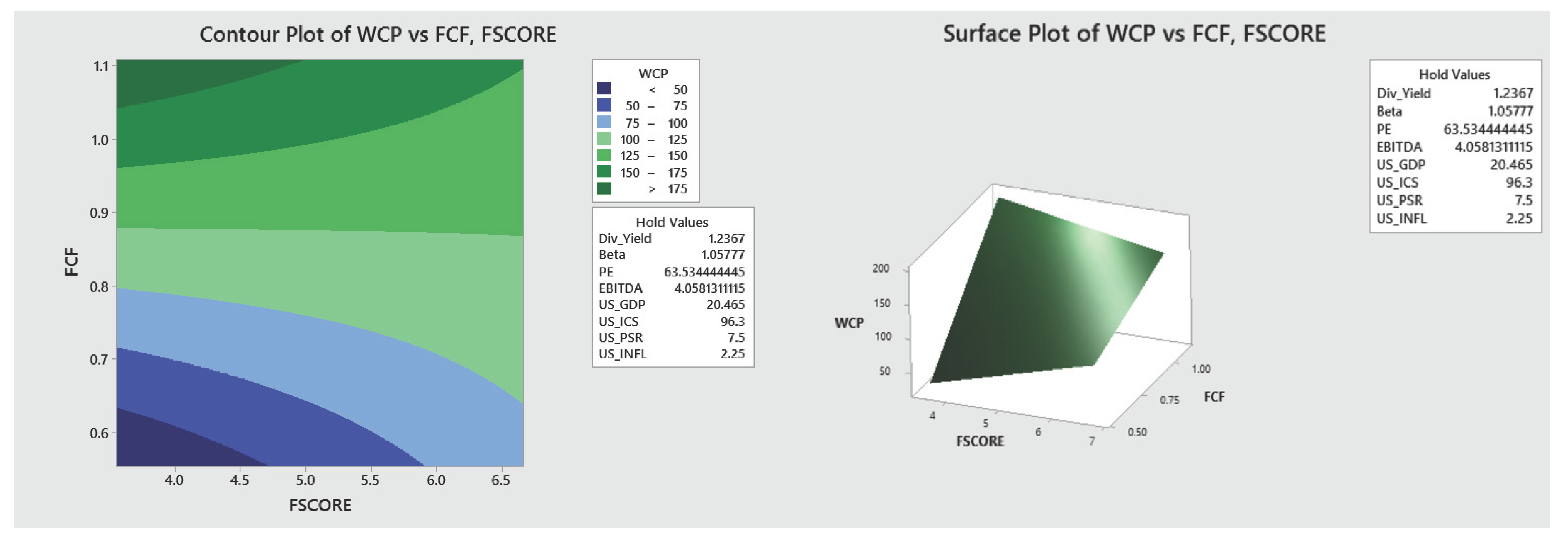

- Finally, two and three-dimensional contour and surface plots were developed, based on the behavior of the values of the financial indicators that maximize the WCP of the HBS. These plots can be used strategically to monitor the behavior of WCP as the significant values of the indicators change.

5. Concluding Remark

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Graphical Visualization of the Optimization Results

Appendix B. Supplementary Material

References

- Fama, E.F.; French, K.R. The cross-section of expected stock returns. the Journal of Finance 1992, 47, 427–465. [Google Scholar]

- Piotroski, J.D. Value investing: The use of historical financial statement information to separate winners from losers. Journal of Accounting Research 2000, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.F.; Roll, R.; Ross, S.A. Economic forces and the stock market. Journal of business 1986, 383–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F. Stock returns, expected returns, and real activity. The journal of finance 1990, 45, 1089–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapach, D.; Zhou, G. Forecasting stock returns. In Handbook of economic forecasting; Elsevier, 2013; Vol. 2, pp. 328–383.

- Siegel, J.J.; Schwartz, J.D. Long-term returns on the original S&P 500 companies. Financial Analysts Journal 2006, 62, 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sakaki, H. Oil price shocks and the equity market: Evidence for the S&P 500 sectoral indices. Research in International Business and Finance 2019, 49, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaller, I.G.; Koch, P.D.; Koch, T.W. The temporal price relationship between S&P 500 futures and the S&P 500 index. The Journal of Finance 1987, 42, 1309–1329. [Google Scholar]

- Dieleman, J.L.; Cao, J.; Chapin, A.; Chen, C.; Li, Z.; Liu, A.; Horst, C.; Kaldjian, A.; Matyasz, T.; Scott, K.W.; et al. US health care spending by payer and health condition, 1996-2016. Jama 2020, 323, 863–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.P.; Chen, W.Y.; Tseng, T.C. Co-movements of returns in the health care sectors from the US, UK, and Germany stock markets: Evidence from the continuous wavelet analyses. International Review of Economics & Finance 2017, 49, 484–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Q. Enhancing stock market Forecasting: A hybrid model for accurate prediction of S&P 500 and CSI 300 future prices. Expert Systems with Applications 2025, 260, 125380. [Google Scholar]

- Alamu, O.S.; Siam, M.K. Stock price prediction and traditional models: An approach to achieve short-, medium-and long-term goals. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.07220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Tsokos, C. A Stock Optimization Problem in Finance: Understanding Financial and Economic Indicators through Analytical Predictive Modeling. Mathematics 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashgari, A. Assessing text mining and technical analyses on forecasting financial time series. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.14544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangwan, V.; Kumar, V.; Christopher, V.B. Contrasting the efficiency of stock price prediction models using various types of LSTM models aided with sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings. AIP Publishing, 2024, Vol. 3075.

- Kumar, S.; Ghildayal, N.S.; Shah, R.N. Examining quality and efficiency of the US healthcare system. International journal of health care quality assurance 2011, 24, 366–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghupathi, V.; Raghupathi, W. Healthcare expenditure and economic performance: insights from the United States data. Frontiers in public health 2020, 8, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R. Valuation: theories and concepts; Academic Press, 2015.

- McManus, I.; Ap Gwilym, O.; Thomas, S. The role of payout ratio in the relationship between stock returns and dividend yield. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 2004, 31, 1355–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajevardi, S. A study on the effect of P/E and PEG ratios on stock returns: Evidence from Tehran Stock Exchange. Management Science Letters 2014, 4, 1401–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.Y.; Shum, W.C. The conditional relationship between beta and returns: Recent evidence from international stock markets. International Business Review 2003, 12, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkshäusl, C. Piotroski’s FSCORE: international evidence. Journal of Asset Management 2020, 21, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansanen, A.; et al. Effectiveness of Piotroski F-Score for Finnish Stocks. 2016.

- Kusowska, M.; et al. Assessment of efficiency of Piotroski F-Score strategy in the Warsaw Stock Exchange. Przedsiębiorstwo we współczesnej gospodarce–teoria i praktyka 2021, 32, 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Nissim, D. EBITDA, EBITA, or EBIT? Columbia Business School Research Paper, 2019, 17–71.

- Rozenbaum, O. EBITDA and managers’ investment and leverage choices. Contemporary Accounting Research 2019, 36, 513–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, P.P. What is free cash flow and how do I calculate it? James Madison 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, G.D.; Mahendru, M. Impact of macro-economic variables on stock prices in India. Global Journal of Management and Business Research 2010, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Büyüksalvarci, A.; Abdioglu, H. The causal relationship between stock prices and macroeconomic variables: A case study for Turkey. Journal of Economic & Management Perspectives 2010, 4, 601. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, T.K.; Naka, A. Dynamic relations between macroeconomic variables and the Japanese stock market: an application of a vector error correction model. Journal of financial Research 1995, 18, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osamwonyi, I.O.; Evbayiro-Osagie, E.I. The relationship between macroeconomic variables and stock market index in Nigeria. Journal of Economics 2012, 3, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.; Mehta, S.; Varsha, M. Macroeconomic factors and stock returns: Evidence from Taiwan. Journal of economics and international finance 2011, 3, 217. [Google Scholar]

- Jareño, F.; Negrut, L.; et al. US stock market and macroeconomic factors. Journal of Applied Business Research (JABR) 2016, 32, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmon, M.; Portniaguina, E. Consumer confidence and asset prices: Some empirical evidence. The Review of Financial Studies 2006, 19, 1499–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howrey, E. The Predictive Power of the Index of Consumer Sentiment. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2001, 32, 175–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singal, M. Effect of consumer sentiment on hospitality expenditures and stock returns. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2012, 31, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tootell, G.M.; et al. Globalization and US inflation. New England Economic Review 1998, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Antonakakis, N.; Gupta, R.; Tiwari, A.K. Has the correlation of inflation and stock prices changed in the United States over the last two centuries? Research in International Business and Finance 2017, 42, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albulescu, C.T.; Aubin, C.; Goyeau, D. Stock prices, inflation and inflation uncertainty in the US: testing the long-run relationship considering Dow Jones sector indexes. Applied Economics 2017, 49, 1794–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, C.; Selcuk, P. The impact of globalization and digitalization on the Phillips Curve. Technical report, Bank of Canada Staff Working Paper, 2022.

- Van Rooij, M.; Lusardi, A.; Alessie, R. Financial literacy and stock market participation. Journal of Financial economics 2011, 101, 449–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Estrada, E.; Cosmes, W. Shapiro–Wilk test for skew normal distributions based on data transformations. Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation 2019, 89, 3258–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royston, P. Approximating the Shapiro-Wilk W-test for non-normality. Statistics and computing 1992, 2, 117–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, I.K.; Johnson, R.A. A new family of power transformations to improve normality or symmetry. Biometrika 2000, 87, 954–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnum, N.R. Using JOHNSON curves to describe non-normal ROCESS data. Quality Engineering 1996, 9, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polansky, A.M.; Chou, Y.M.; Mason, R.L. An algorithm for fitting Johnson transformations to non-normal data. Journal of quality technology 1999, 31, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fashoto, S.G.; Mbunge, E.; Ogunleye, G.; den Burg, J.V. Implementation of machine learning for predicting maize crop yields using multiple linear regression and backward elimination. Malaysian Journal of Computing (MJoC) 2021, 6, 679–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, A.R.; Mohanty, M.K.; Fifarek, R.H. Backward elimination procedure for a predictive model of gold concentration. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 2008, 97, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustam, F.; Reshi, A.A.; Mehmood, A.; Ullah, S.; On, B.W.; Aslam, W.; Choi, G.S. COVID-19 future forecasting using supervised machine learning models. IEEE access 2020, 8, 101489–101499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.T.; Yeh, P.Y. Reliable accuracy estimates from k-fold cross validation. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2019, 32, 1586–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrar, D.; et al. Cross-Validation., 2019.

- de Lima Lemos, R.A.; Silva, T.C.; Tabak, B.M. Propension to customer churn in a financial institution: A machine learning approach. Neural Computing and Applications 2022, 34, 11751–11768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, J. Forecasting of real GDP growth using machine learning models: Gradient boosting and random forest approach. Computational Economics 2021, 57, 247–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, A.; Chaudhari, K. A comprehensive survey on portfolio optimization, stock price and trend prediction using particle swarm optimization. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2021, 28, 2133–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülmez, B. Stock price prediction with optimized deep LSTM network with artificial rabbits optimization algorithm. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, 227, 120346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; He, T.; Benesty, M.; Khotilovich, V.; Tang, Y.; Cho, H.; Chen, K.; Mitchell, R.; Cano, I.; Zhou, T.; et al. Xgboost: extreme gradient boosting. R package version 0.4-2 2015, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Osman, A.I.A.; Ahmed, A.N.; Chow, M.F.; Huang, Y.F.; El-Shafie, A. Extreme gradient boosting (Xgboost) model to predict the groundwater levels in Selangor Malaysia. Ain Shams Engineering Journal 2021, 12, 1545–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, Y.G.; Burrage, K.; Tian, Y.C.; Lawson, B.; Ding, Z. An improved firefly algorithm for global continuous optimization problems. Expert Systems with Applications 2020, 149, 113340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnik, A.; Shumetov, V.; Kondrashin, B.; Mikhaylov, M. Use of Harrington’s desirability function in wheat grain quality assessment. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. IOP Publishing, 2020, Vol. 422:1.

- Palandi Cardoso, R.; da Motta Reis, J.S.; Werderits Silva, D.E.; Medeiros de Barros, J.G.; de Souza Sampaio, N.A. How to perform a simultaneous optimization with several response variables. GeSec: Revista de Gestao e Secretariado 2023, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Nazarpour, M.; Taghizadeh-Alisaraei, A.; Asghari, A.; Abbaszadeh-Mayvan, A.; Tatari, A. Optimization of biohydrogen production from microalgae by response surface methodology (RSM). Energy 2022, 253, 124059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, M.; Gupta, S.K. Response surface methodological (RSM) approach for optimizing the removal of trihalomethanes (THMs) and its precursor’s by surfactant modified magnetic nanoadsorbents (sMNP)-An endeavor to diminish probable cancer risk. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 18339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derringer, G.; Suich, R. Simultaneous optimization of several response variables. Journal of quality technology 1980, 12, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhayoun, N.; Chairi, I.; El Gonnouni, A.; Lyhyaoui, A. Financial intelligence in prediction of firm’s creditworthiness risk: evidence from support vector machine approach. Procedia Economics and Finance 2013, 5, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Tsokos, C.P. An AI-driven Predictive Model for Pancreatic Cancer Patients Using Extreme Gradient Boosting. Journal of Statistical Theory and Applications 2023, 22, 262–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malyshenko, K.A.; Shafiee, M.M.; Malyshenko, V.A.; Anashkina, M.V. Dynamics of the securities market in the information asymmetry context: developing a methodology for emerging securities markets. Global Business and Economics Review 2021, 25, 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Tsokos, C. A Stock Optimization Problem in Finance: Understanding Financial and Economic Indicators through Analytical Predictive Modeling. Mathematics 2024, 12, 2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, S.; Proietti, T.; Frale, C.; Marcellino, M.; Mazzi, G. EuroMInd-C: A disaggregate monthly indicator of economic activity for the Euro area and member countries. International Journal of Forecasting 2015, 31, 712–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Xiaojing, G.; Ningning, Z. Notice of Retraction: The principal component analysis and evaluation of financial performance for enterprises based on cash flow information. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Management Science (ICAMS 2010). IEEE, 2010, Vol. 3, pp. 291–296.

- Jiang, W. Applications of deep learning in stock market prediction: recent progress. Expert Systems with Applications 2021, 184, 115537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhou, E. Stock prediction based on optimized LSTM and GRU models. Scientific Programming 2021, 2021, 4055281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Chen, K.; Li, N. Predicting stock movements: using multiresolution wavelet reconstruction and deep learning in neural networks. Information 2021, 12, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietterich, T. Overfitting and undercomputing in machine learning. ACM computing surveys (CSUR) 1995, 27, 326–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbar, H.; Khan, R.Z. Methods to avoid over-fitting and under-fitting in supervised machine learning (comparative study). Computer Science, Communication and Instrumentation Devices 2015, 70, 978–981. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, K.; Xue, C.; Zhang, L. Digesting anomalies: An investment approach. The Review of Financial Studies 2015, 28, 650–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reji, M.; Kumar, R. Response surface methodology (RSM): An overview to analyze multivariate data. Indian J. Microbiol. Res 2022, 9, 241–248. [Google Scholar]

- Breig, S.J.M.; Luti, K.J.K. Response surface methodology: A review on its applications and challenges in microbial cultures. Materials Today: Proceedings 2021, 42, 2277–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sholichah, F.; Asfiah, N.; Ambarwati, T.; Widagdo, B.; Ulfa, M.; Jihadi, M. The effects of profitability and solvability on stock prices: Empirical evidence from Indonesia. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business 2021, 8, 885–894. [Google Scholar]

- Pando, V.; San-Jose, L.A.; Sicilia, J.; Alcaide-Lopez-de Pablo, D. Maximization of the return on inventory management expense in a system with price-and stock-dependent demand rate. Computers & Operations Research 2021, 127, 105134. [Google Scholar]

| Rank | Indicators | Contr.(%) | Rank | Indicators | Contr.(%) |

| 1 | 4.53 | 21 | 2.41 | ||

| 2 | 4.15 | 22 | 2.35 | ||

| 3 | 3.89 | 23 | 2.27 | ||

| 4 | 3.63 | 24 | 2.24 | ||

| 5 | 3.41 | 25 | 2.20 | ||

| 6 | 3.34 | 26 | 2.18 | ||

| 7 | 3.34 | 27 | 2.14 | ||

| 8 | 3.27 | 28 | 2.10 | ||

| 9 | 3.07 | 29 | 2.07 | ||

| 10 | 3.05 | 30 | 2.02 | ||

| 11 | 3.03 | 31 | 1.97 | ||

| 12 | 2.86 | 32 | 1.95 | ||

| 13 | 2.71 | 33 | 1.92 | ||

| 14 | 2.69 | 34 | 1.87 | ||

| 15 | 2.66 | 35 | 1.84 | ||

| 16 | 2.62 | 36 | 1.82 | ||

| 17 | 2.51 | 37 | 1.75 | ||

| 18 | 2.49 | 38 | 1.72 | ||

| 19 | 2.48 | 30 | 1.63 | ||

| 20 | 2.47 | 40 | 1.62 | ||

| 41 | 1.59 |

| Rank | Indicators | No. of Occurrence | Contr.(%) |

| 1 | 8 | 25.32 | |

| 2 | 8 | 20.14 | |

| 3 | 8 | 19.57 | |

| 4 | 7 | 19.23 | |

| 5 | 7 | 18.29 | |

| 6 | 8 | 18.23 | |

| 7 | 7 | 16.44 | |

| 8 | 8 | 16.41 | |

| 9 | 6 | 14.84 | |

| 10 | 5 | 12.66 |

| Indicators | Constraints |

| Response & Indicators | Optimum Values |

|---|---|

| $155 | |

| 96.3 | |

| 7.5 | |

| 2.61 |

| Estimated Maximized Value | $155 |

| Desirability | 1 |

| 98.84% | |

| 97.85% | |

| 95% CI | (139.57, 170.43) |

| 95% PI | (139.06, 170.94) |

| Observations | Observed | Predicted | Observations | Observed | Predicted | |

| 1 | 155 | 156 | 63 | 136 | 141 | |

| 2 | 152 | 150 | 64 | 135 | 137 | |

| 5 | 151 | 149 | 72 | 153 | 148 | |

| 6 | 148 | 148 | 73 | 154 | 148 | |

| 13 | 141 | 145 | 81 | 143 | 147 | |

| 19 | 144 | 145 | 82 | 142 | 147 | |

| 20 | 143 | 146 | 83 | 140 | 141 | |

| 28 | 139 | 144 | 127 | 131 | 131 | |

| 29 | 138 | 144 | 148 | 123 | 126 | |

| 36 | 149 | 145 | 212 | 111 | 111 | |

| 37 | 150 | 144 | 213 | 111 | 112 | |

| 38 | 149 | 145 | 252 | 104 | 104 | |

| 39 | 152 | 148 | 255 | 104 | 107 | |

| 40 | 153 | 148 | 256 | 105 | 104 | |

| 41 | 153 | 155 | 272 | 98 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).