Introduction

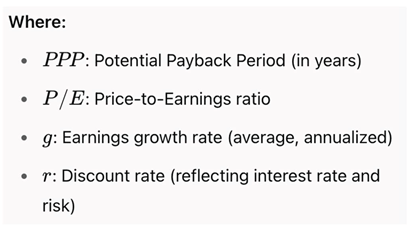

Over the course of the 20th and 21st centuries, financial analysis has undergone a series of profound conceptual transformations. These revolutions have successively redefined the way investors, analysts, academics, and institutions understand value, measure risk, and make decisions in increasingly complex and interconnected financial markets. From the early realization that the value of money changes over time, to sophisticated models incorporating uncertainty, behavioral biases, and sustainability factors, each new framework has built upon or challenged previous ones — pushing the boundaries of what constitutes sound financial reasoning.

These revolutions are not merely academic milestones; they have had significant practical implications. They have shaped everything from capital budgeting and portfolio construction to pricing models and regulatory standards. Most importantly, they reflect an ongoing quest to bridge theory and reality — to better model how financial markets work and how investment decisions should be made.

This article outlines ten key conceptual revolutions that have shaped modern financial analysis. It traces their chronological development, highlights their theoretical breakthroughs, and examines their enduring impact on the practice of finance. From foundational principles like the time value of money to the dynamic valuation model offered by the Potential Payback Period (PPP), these revolutions collectively define the intellectual architecture of contemporary financial thought.

1. Time Value of Money and Discounted Cash Flow (Early 20th Century)

The most foundational concept in finance is the time value of money (TVM)—the principle that a dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow. Introduced formally by Irving Fisher and later operationalized by John Burr Williams in The Theory of Investment Value (1938), this concept led to the discounted cash flow (DCF) model. By valuing an asset as the present value of its expected future cash flows, DCF laid the groundwork for virtually all modern asset valuation techniques. It captured both the value of time and the cost of capital, making it applicable to stocks, bonds, and investment projects alike.

2. Modern Portfolio Theory (1952)

Harry Markowitz revolutionized financial thinking by introducing Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT). His 1952 paper, “Portfolio Selection,” demonstrated that portfolio risk could be reduced through diversification, and that investors should focus on the mean-variance optimization of returns. The key insight was that the risk of a portfolio is not merely the sum of the risks of its components, but also a function of how those assets move in relation to one another. MPT introduced the efficient frontier, changing how institutions constructed portfolios and how investors viewed diversification as a tool for risk reduction.

3. Capital Asset Pricing Model (1964)

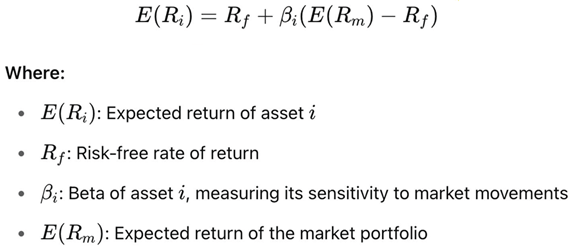

Building on MPT, the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), developed by Sharpe, Lintner, and Mossin, formalized the relationship between risk and return. CAPM introduced the idea of systematic risk (beta) and the risk-free rate, with expected return determined by exposure to market risk:

CAPM provided a theoretical framework for pricing securities and for estimating the cost of equity capital, becoming central to corporate finance, investment analysis, and performance benchmarking.

4. Efficient Market Hypothesis (1970)

In the 1970s, Eugene Fama advanced the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH), asserting that security prices always fully reflect all available information. EMH challenged the utility of active management, suggesting that beating the market consistently is nearly impossible. It justified the growth of passive investing and index funds, while also igniting debates about anomalies, bubbles, and investor irrationality. EMH exists in three forms—weak, semi-strong, and strong—each assuming different levels of information efficiency.

5. Option Pricing Theory (1973)

The creation of the Black-Scholes-Merton model was a monumental leap in financial mathematics. For the first time, options and other derivatives could be priced using a closed-form formula based on stochastic calculus. This innovation enabled the explosive growth of derivatives markets and provided a new method of hedging and risk transfer. Option pricing theory also influenced real options analysis in corporate finance and contributed to Nobel Prizes for Scholes and Merton.

6. Behavioral Finance (1980s–1990s)

In contrast to EMH and rational-agent models, Behavioral Finance incorporates insights from psychology to explain irrational investor behavior. Pioneered by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky (Prospect Theory), and expanded by Richard Thaler and Robert Shiller, this school documented systematic biases such as overconfidence, loss aversion, and mental accounting. Behavioral finance provided a new lens for understanding anomalies like momentum, bubbles, and market crashes, and laid the foundation for nudging, financial education, and policy reform.

7. Arbitrage Pricing Theory (1976)

Stephen Ross introduced the Arbitrage Pricing Theory (APT) as a more flexible alternative to CAPM. Instead of a single market factor, APT allows multiple macroeconomic and statistical factors to explain asset returns. It assumed that arbitrage opportunities are limited in equilibrium and emphasized factor-based pricing. APT influenced the development of multi-factor models, such as the Fama-French three- and five-factor models, now widely used in academic research and quantitative investing.

8. Factor Investing and Smart Beta (2000s)

Factor investing translated APT into practice by identifying and targeting persistent return drivers such as value, size, momentum, quality, and low volatility. This gave rise to smart beta strategies, which systematically deviate from market-cap weights to enhance risk-adjusted returns. The success of academic research in identifying factor premia led to a proliferation of low-cost ETFs and rules-based portfolios, democratizing access to sophisticated investment strategies.

9. ESG and Impact Investing (2010s–2020s)

The growing awareness of climate change, social inequality, and corporate governance led to the integration of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors into financial analysis. ESG revolutionized the definition of risk and value by incorporating non-financial metrics. Impact investing, which seeks both financial return and measurable social/environmental impact, gained momentum. While initially controversial, ESG has become a mainstream part of risk management, capital allocation, and regulatory reporting.

10. Potential Payback Period (PPP) and Dynamic Valuation (21st Century)

The Potential Payback Period (PPP), developed by Rainsy Sam, marks a new conceptual leap in stock valuation. While traditional valuation relies heavily on static metrics like the Price-to-Earnings (P/E) ratio or PEG ratio, PPP offers a dynamic alternative that integrates:

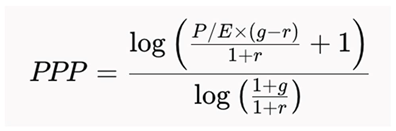

The PPP is calculated using the following formula:

The PPP formula measures how many years it would theoretically take for future discounted earnings to recover the current stock price. This period reflects the earning power of a company and allows direct comparison with bond durations. The PPP restores temporal meaning to valuation and yields a derived Stock Internal Rate of Return (SIRR) that bridges equity and fixed income investing. It extends and subsumes the P/E ratio, providing a unified and more realistic measure of intrinsic value, especially useful for high-growth firms, startups, and global market comparisons.

Conclusion

Financial analysis has evolved through waves of conceptual innovation, each addressing new dimensions of valuation, risk, and investor behavior. The trajectory from time value of money to PPP reveals a shift:

From static to dynamic metrics

From rationality to realism

From simplicity to integration

The ten revolutions discussed reflect an ongoing effort to build tools that better mirror the complexities of financial markets and investor decision-making. As the field continues to evolve, the challenge remains to balance theoretical rigor with practical relevance in the face of changing macroeconomic, technological, and societal dynamics.

References

- Fisher, I. (1930). The Theory of Interest.

- Williams, J.B. (1938). The Theory of Investment Value.

- Markowitz, H. (1952). “Portfolio Selection”. The Journal of Finance.

- Sharpe, W. (1964). “Capital Asset Prices: A Theory of Market Equilibrium under Conditions of Risk”. The Journal of Finance. [CrossRef]

- Fama, E. (1970). “Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work”. The Journal of Finance. [CrossRef]

- Black, F., & Scholes, M. (1973). “The Pricing of Options and Corporate Liabilities”. Journal of Political Economy. [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk”. Econometrica.

- Ross, S. (1976). “The Arbitrage Theory of Capital Asset Pricing”. Journal of Economic Theory.

- Fama, E., & French, K. (1992, 2015). Multi-Factor Models.

- Sam, R. (2024). www.stockinternalrateofreturn.com.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).