Submitted:

26 August 2025

Posted:

27 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- RQ01: How do DevOps practices impact traditional PMO governance practices within the UAE technology sector?

- RQ02: What are the key challenges and opportunities PMOs face when adopting DevOps practices?

- RQ03: What strategies can PMOs implement to effectively integrate DevOps practices into their governance frameworks?

2. Literature Review

2.1. DevOps in Current Application Trends

2.2. DevOps in UAE

2.2.1. Diversity as a Double-Edged Sword

2.2.2. Integrating DevOps into Education for Workforce Readiness

2.2.3. Adapting Frameworks and Architectures for DevOps

2.2.4. Navigating Obstacles and Embracing Cultural Shifts

2.2.5. Prioritizing Technological Innovation and Security

2.2.6. The Role of Government Initiatives and Leadership

2.2.7. Addressing the Skills Shortage and Investing in Human Capital

2.3. The Agile Transformation of PMO Governance

2.3.1. Evolving Governance Roles and Structures

2.3.2. Balancing Flexibility and Strategic Alignment

2.3.3. Navigating External Pressures and Cultural Shifts

2.3.4. Adapting to Future Trends and Maintaining Momentum

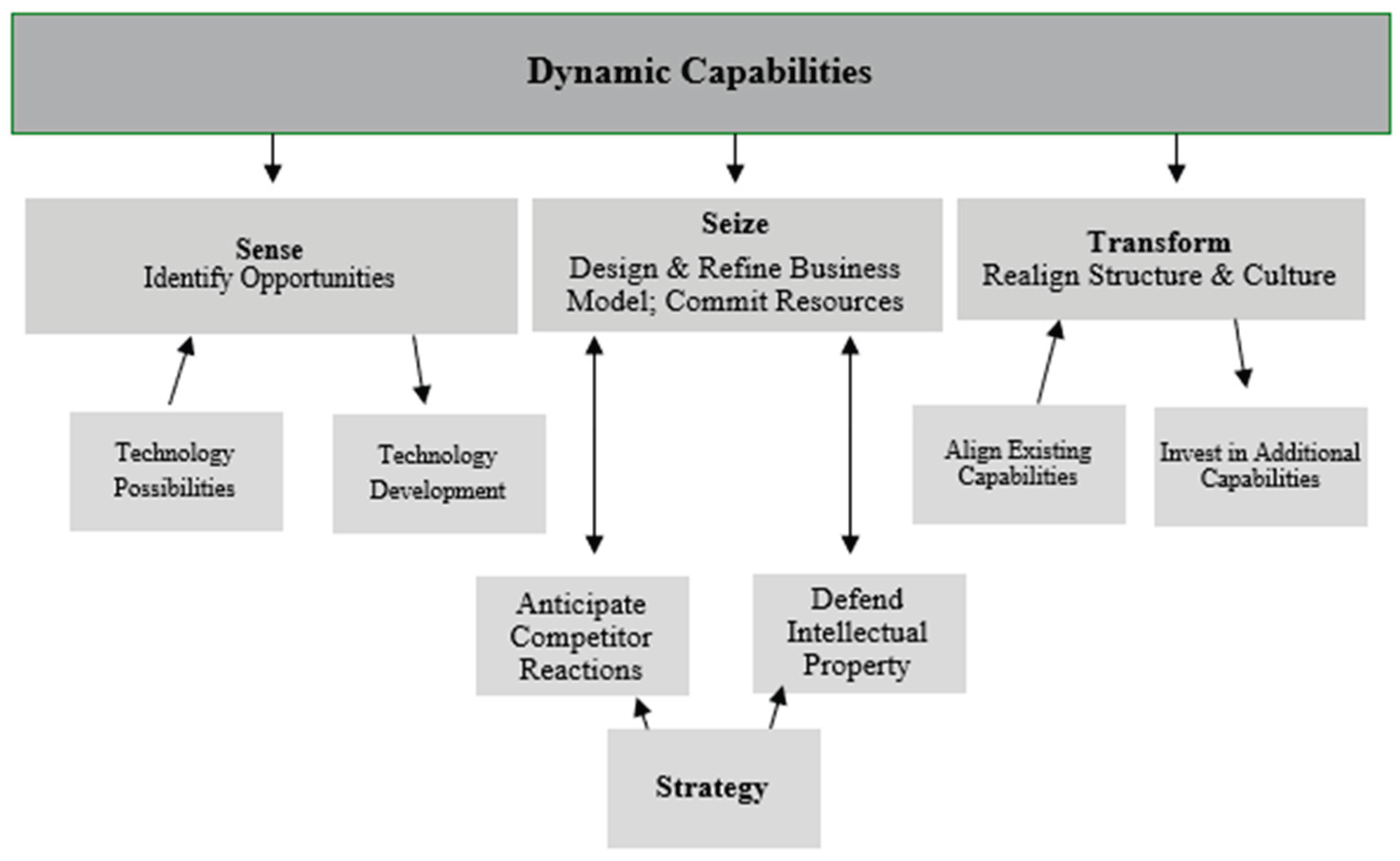

2.4. Synergizing the Dynamic Capabilities Framework and Agile DevOps Reference Model

2.5. Research Framework

Framework Constructs

3. Method and Instruments

3.1. Techniques and Procedures

3.1.1. Methods and Procedures of Data Collection

3.1.2. Instrumentation and Implementation

- (1) Introduction and consent statement;

- (2) Demographics including industry sector, years of experience, and current role;

- (3) Likert-scale items (1=Strongly Disagree to 5=Strongly Agree) assessing constructs from the DCF and ADRM frameworks;

- (4) Open-ended questions on organizational DevOps adoption challenges; and

- (5) Closing remarks.

3.1.3. Data Analysis Procedures

4. Hypothesis Development

- H1: The adoption of a microservices architecture in DevOps is significantly correlated with effective PMO governance practices.

- H2: A culture that embraces Minimum Viable Experience (MVE) enhances the flexibility of PMO governance within a DevOps environment.

- H3: Continuous Value Stream Integration (CVS) significantly improves the quality and reliability of PMO governance practices.

- H4: Automated configuration (AC) in DevOps positively impacts the efficiency of PMO governance.

- H5: Continuous Delivery/Continuous Deployment (CD) practices complement and reinforce the purpose-driven nature of PMO governance.

5. Results

5.1. Measurement Model

- Reliability: The consistency and stability of the measurement.

- Validity: The extent to which the indicators accurately measure the intended constructs.

- Indicator Multicollinearity: The degree of correlation between indicators within a construct.

- Inter-construct Correlations: The relationships between different latent constructs.

5.1.1. Model Fit

- 1. SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual):

- Value: 0.0597

- HI95: 0.0448

- HI99: 0.0500

- 2. dULS (Unweighted Least Squares Discrepancy):

- Value: 1.6563

- HI95: 0.9339

- HI99: 1.1630

- 3. dG (Geodesic Discrepancy):

- Value: 1.0717

- HI95: 0.5337

- HI99: 0.6255

5.1.2. Construct Reliability

5.1.3. Convergent Validity Using AVE

5.1.4. Discriminant Validity

5.1.5. Indicator Multicollinearity

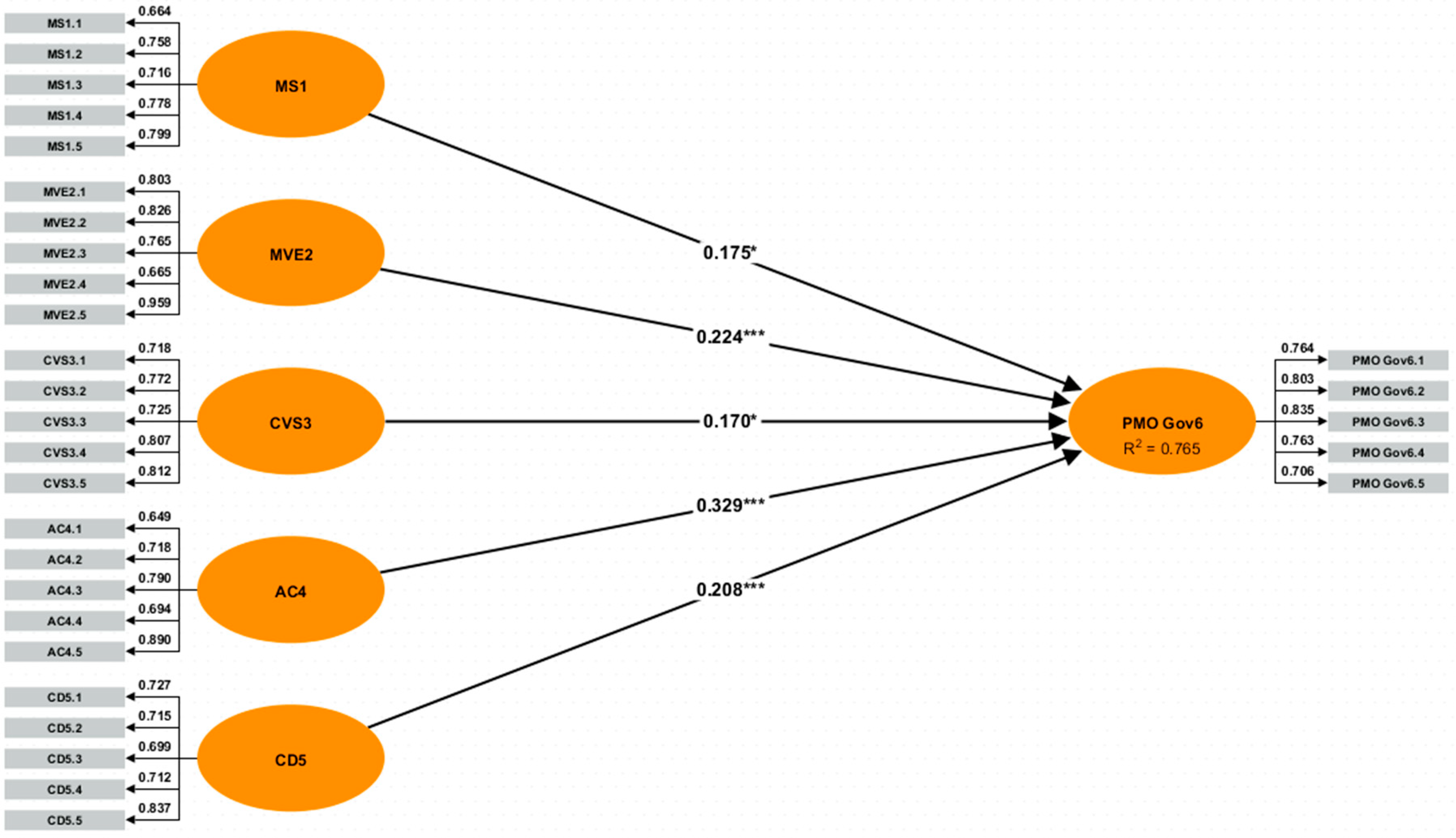

5.2. Structural Model

5.2.1. Coefficient of Determination (R2)

5.2.2. Assessment of the Hypotheses and the Path Coefficients

- Microservices (MS1): Organizations adopting microservices demonstrate a stronger inclination towards implementing effective PMO governance practices (β = 0.1750, t = 2.5125, p < 0.01). This finding supports H1.

- Minimum Viable Experience (MVE2): Organizations leveraging minimum viable experiences are more likely to perceive and realize the benefits of PMO governance (β = 0.2244, t = 3.6072, p < 0.01), confirming H2.

- Continuous Value Stream (CVS3): Prioritizing continuous value streams is positively associated with the adoption of effective PMO governance (β = 0.1696, t = 2.5719, p < 0.01), supporting H3.

- Automated Configuration (AC4): Organizations utilizing automated configuration exhibit a stronger tendency towards implementing robust PMO governance practices (β = 0.3286, t = 4.4585, p < 0.01), confirming H4.

- Continuous Delivery/Deployment (CD5): Prioritizing continuous delivery and deployment is positively linked to the adoption of effective PMO governance (β = 0.2083, t = 3.3727, p < 0.01), supporting H5.

5.2.3. Results & Summary of Hypotheses Analysis

- Microservices: Microservices, due to the modularity adopted, can easily incorporate within the PMO governance structure, which is systemic in its approach.

- Minimum Viable Experience (MVE): Demanding fast cycles and intellectual challenging based on MVEs encourages perceiving the worth of PMO governance.

- Continuous Value Stream: Extending the concept of ‘concurrent value streams’ helps in providing a ‘smooth line of value’, which is actually in sync with PMO governance goals.

- Automated Configuration: The rise of automation and standardization requires the PMO governance to address these issues in order to manage them.

- Continuous Delivery/Deployment (CD): The nature of receiving and delivering CD involves quick turnaround frequently characterized by feedback; thus, PMO governance should be flexible.

6. Discussion

Implications

Theoretical Implications

Practical Implications

Practical UAE Impact

Limitations

Scope for Future Research

7. Conclusions

Funding

Appendix A. Convergent Validity Using Indicator Loadings

| Indicator | MS1 | MVE2 | CVS3 | AC4 | CD5 | PMO Gov6 |

| MS1.1 | 0.6636 | |||||

| MS1.2 | 0.7582 | |||||

| MS1.3 | 0.7162 | |||||

| MS1.4 | 0.7780 | |||||

| MS1.5 | 0.7987 | |||||

| MVE2.1 | 0.8029 | |||||

| MVE2.2 | 0.8261 | |||||

| MVE2.3 | 0.7646 | |||||

| MVE2.4 | 0.6650 | |||||

| MVE2.5 | 0.9593 | |||||

| CVS3.1 | 0.7179 | |||||

| CVS3.2 | 0.7720 | |||||

| CVS3.3 | 0.7255 | |||||

| CVS3.4 | 0.8070 | |||||

| CVS3.5 | 0.8120 | |||||

| AC4.1 | 0.6492 | |||||

| AC4.2 | 0.7183 | |||||

| AC4.3 | 0.7900 | |||||

| AC4.4 | 0.6944 | |||||

| AC4.5 | 0.8897 | |||||

| CD5.1 | 0.7274 | |||||

| CD5.2 | 0.7150 | |||||

| CD5.3 | 0.6985 | |||||

| CD5.4 | 0.7121 | |||||

| CD5.5 | 0.8370 | |||||

| PMO Gov6.1 | 0.7643 | |||||

| PMO Gov6.2 | 0.8029 | |||||

| PMO Gov6.3 | 0.8352 | |||||

| PMO Gov6.4 | 0.7626 | |||||

| PMO Gov6.5 | 0.7065 |

Appendix B. Discriminant Validity Loadings

| Indicator | MS1 | MVE2 | CVS3 | AC4 | CD5 | PMO Gov6 |

| MS1.1 | 0.6636 | 0.3876 | 0.3310 | 0.3216 | 0.2580 | 0.4287 |

| MS1.2 | 0.7582 | 0.4645 | 0.3756 | 0.3791 | 0.3917 | 0.4899 |

| MS1.3 | 0.7162 | 0.4682 | 0.3596 | 0.3464 | 0.3220 | 0.4627 |

| MS1.4 | 0.7780 | 0.4064 | 0.4401 | 0.4023 | 0.3209 | 0.5027 |

| MS1.5 | 0.7987 | 0.5022 | 0.3392 | 0.3061 | 0.4366 | 0.5160 |

| MVE2.1 | 0.5465 | 0.8029 | 0.3614 | 0.4160 | 0.3327 | 0.5466 |

| MVE2.2 | 0.4642 | 0.8261 | 0.4292 | 0.4502 | 0.4258 | 0.5624 |

| MVE2.3 | 0.4957 | 0.7646 | 0.3412 | 0.3896 | 0.3266 | 0.5205 |

| MVE2.4 | 0.4390 | 0.6650 | 0.3067 | 0.4495 | 0.2483 | 0.4527 |

| MVE2.5 | 0.4903 | 0.9593 | 0.5002 | 0.4623 | 0.4597 | 0.6531 |

| CVS3.1 | 0.3460 | 0.3253 | 0.7179 | 0.4437 | 0.3966 | 0.4903 |

| CVS3.2 | 0.4055 | 0.3622 | 0.7720 | 0.4620 | 0.4028 | 0.5273 |

| CVS3.3 | 0.3511 | 0.3498 | 0.7255 | 0.4684 | 0.4023 | 0.4955 |

| CVS3.4 | 0.4223 | 0.4666 | 0.8070 | 0.4584 | 0.4529 | 0.5512 |

| CVS3.5 | 0.3771 | 0.3544 | 0.8120 | 0.5090 | 0.4998 | 0.5546 |

| AC4.1 | 0.3659 | 0.3509 | 0.3434 | 0.6492 | 0.2197 | 0.4846 |

| AC4.2 | 0.3706 | 0.4178 | 0.4120 | 0.7183 | 0.3856 | 0.5361 |

| AC4.3 | 0.3422 | 0.3758 | 0.5463 | 0.7900 | 0.4080 | 0.5896 |

| AC4.4 | 0.2963 | 0.3851 | 0.4208 | 0.6944 | 0.3734 | 0.5183 |

| AC4.5 | 0.4009 | 0.4720 | 0.5470 | 0.8897 | 0.5912 | 0.6641 |

| CD5.1 | 0.3349 | 0.3322 | 0.4135 | 0.4094 | 0.7274 | 0.4827 |

| CD5.2 | 0.3839 | 0.3542 | 0.3980 | 0.4066 | 0.7150 | 0.4745 |

| CD5.3 | 0.3359 | 0.2764 | 0.3986 | 0.3372 | 0.6985 | 0.4636 |

| CD5.4 | 0.3302 | 0.3305 | 0.3777 | 0.4768 | 0.7121 | 0.4726 |

| CD5.5 | 0.3497 | 0.3691 | 0.4859 | 0.3705 | 0.8370 | 0.5555 |

| PMO Gov6.1 | 0.6396 | 0.5945 | 0.4838 | 0.4922 | 0.4138 | 0.7643 |

| PMO Gov6.2 | 0.5444 | 0.6028 | 0.5537 | 0.5129 | 0.5397 | 0.8029 |

| PMO Gov6.3 | 0.5017 | 0.5548 | 0.7107 | 0.5800 | 0.5088 | 0.8352 |

| PMO Gov6.4 | 0.4108 | 0.4492 | 0.4850 | 0.7444 | 0.4997 | 0.7626 |

| PMO Gov6.5 | 0.4028 | 0.4287 | 0.3908 | 0.5723 | 0.6230 | 0.7065 |

Appendix C. Indicator Multicollinearity

| Effect | Original coefficient | Standard bootstrap results | Percentile bootstrap quantiles | |||||||

| Mean value | Standard error | t-value | p-value (2-sided) | p-value (1-sided) | 0.5% | 2.5% | 97.5% | 99.5% | ||

| MS1 -> PMO Gov6 | 0.1750 | 0.1845 | 0.0696 | 2.5125 | 0.0121 | 0.0061 | -0.0025 | 0.0362 | 0.3153 | 0.3694 |

| MVE2 -> PMO Gov6 | 0.2244 | 0.2194 | 0.0622 | 3.6072 | 0.0003 | 0.0002 | 0.0414 | 0.1011 | 0.3422 | 0.3856 |

| CVS3 -> PMO Gov6 | 0.1696 | 0.1700 | 0.0660 | 2.5719 | 0.0103 | 0.0051 | 0.0027 | 0.0354 | 0.2953 | 0.3352 |

| AC4 -> PMO Gov6 | 0.3286 | 0.3249 | 0.0737 | 4.4585 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.1308 | 0.1775 | 0.4657 | 0.5072 |

| CD5 -> PMO Gov6 | 0.2083 | 0.2103 | 0.0618 | 3.3727 | 0.0008 | 0.0004 | 0.0387 | 0.0875 | 0.3401 | 0.3715 |

References

- A Schtein, I. (2018). Management Strategies for Adopting Agile Methods of Software Development in Distributed Teams.

- Akbar, M. (2023). DevOps project management success factors: a decision-making framework. Software Practice and Experience, 54(2), 257-280. [CrossRef]

- Akbar, M. , Naveed, W., Mahmood, S., Alsanad, A., Alsanad, A., Gumaei, A., … & Mateen, A. (2020). Prioritization-based taxonomy of dev ops challenges using fuzzy AHP analysis. Ieee Access, 8, 202487-202507. [CrossRef]

- Akbar, M. , Naveed, W., Mahmood, S., Alsanad, A., Alsanad, A., Gumaei, A., … & Mateen, A. (2020). Prioritization-based taxonomy of dev ops challenges using fuzzy AHP analysis. Ieee Access, 8, 202487-202507. [CrossRef]

- Alenezi, M. (2022). Factors Hindering the Adoption of DevOps in the Saudi Software Industry.

- Al-Jenaibi, B. (2011). The Scope and Impact of Workplace Diversity in the United Arab Emirates – An Initial Study.

- Alsaber, L., Elsheikh, E., Aljumah, S., & Jamail, N. (2021). Perspectives on the adherence to scrum rules in software project management. Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, 21(1), 360. [CrossRef]

- Anjaria, D. and Kulkarni, M. (2022). Effective develops implementation: a systematic literature review. CM, (24), 410-417. [CrossRef]

- Azad, N. (2022). Understanding DevOps critical success factors and organizational practices., 83-90. [CrossRef]

- Azad, N. and Hyrynsalmi, S. (2022). DevOps challenges in organizations: through a professional lens., 260-277. [CrossRef]

- Azad, N. and Hyrynsalmi, S. (2022). DevOps challenges in organizations: through a professional lens., 260-277. [CrossRef]

- Baiyere, A., Grover, V., & Lyytinen, K. (2020). Digital transformation and the new logics of business process management. European Journal of Information Systems, 29(3), 238–259.

- Bezemer, C. , Eismann, S., Ferme, V., Grohmann, J., Heinrich, R., Jamshidi, P., … & Willnecker, F. (2019). How is performance addressed in devops? [CrossRef]

- Bildirici, F. & Akdemir, Ömür (2023). From Agile to DevOps, Holistic Approach for Faster and Efficient Software Product Release Management.

- Bobrov, E. , Bucchiarone, A., Capozucca, A., Guelfi, N., Mazzara, M., & Masyagin, S. (2020). Teaching DevOps in academia and industry: reflections and vision., 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Capizzi, A. , Distefano, S., & Mazzara, M. (2020). From DevOps to deviations: data management in DevOps processes., 52-62. [CrossRef]

- Chamberland-Tremblay, D. (2024). Leveraging location intelligence for enhanced damage insurance underwriting in the context of climate change. [CrossRef]

- Díaz, J. , Pérez, J., Yagüe, A., Villegas, A., & Antona, A. (2019). Devops in practice – a preliminary analysis of two multinational companies., 323-330. [CrossRef]

- El Aouni, F. , Moumane, K., Idri, A., Najib, M., & Jan, S. U. (2024). A systematic literature review on Agile, Cloud, and DevOps integration: Challenges, benefits. Information and Software Technology, 107569.

- Erdenebat, B. (2023). Multi-project multi-environment approach—an enhancement to existing DevOps and continuous integration and continuous deployment tools. Computers, 12(12), 254. [CrossRef]

- Fawzy, A. , Tahir, A., Galster, M., & Liang, P. (2024). Data Management Challenges in Agile Software Projects: A Systematic Literature Review.

- Ghantous, G. B. & Gill, A. Q. (2019). An agile-devops reference architecture for teaching enterprise agile.

- Gill, A., Loumish, A., Riyat, I., & Han, S. (2018). Devops for information management systems. Vine Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, 48(1), 122-139. [CrossRef]

- Gómez González, D. & Vargas, J. (2015). Diseño e implementación de una PMO ágil para una pyme del sector de las Tecnologías de la Información y la Comunicación TIC.

- Guerrero, J. , Zúñiga, K., Certuche, C., & Pardo, C. (2020). A systematic mapping study about DevOps. Journal De Ciencia E Ingeniería, 12(1), 48-62. [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, J. , Zúñiga, K., Certuche, C., & Pardo, C. (2020). A systematic mapping study about DevOps. Journal De Ciencia E Ingeniería, 12(1), 48-62. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J. , Yang, D., Siegmund, N., Apel, S., Sarkar, A., Valov, P., Czarnecki, K., Wąsowski, A., & Yu, H. (2018). Data-efficient performance learning for configurable systems. Empirical Software Engineering, 23, 1826-1867. [CrossRef]

- Gwangwadza, A. & Hanslo, R. (2022). Factors that Contribute to the Success of a Software Organisation’s DevOps Environment: A Systematic Review.

- Hamza, U. (2024). DevOps adoption guidelines, challenges, and benefits: a systematic literature review. Journal of Advanced Research in Applied Sciences and Engineering Technology, 114-136. [CrossRef]

- Hemon, A. , Lyonnet, B., Rowe, F., & Fitzgerald, B. (2018). Conceptualizing the transition from agile to DevOps: a maturity model for a smarter is function., 209-223. [CrossRef]

- Hossain Tanzil, M. , Sarker, M., Uddin, G., & Iqbal, A. (2024). A Mixed Method Study of DevOps Challenges.

- Huang, Y., Fang, Y., Li, X., & Xu, J. (2022). Coordinated Power Control for Network Integrated Sensing and Communication. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, 71, 13361-13365. [CrossRef]

- J. H. de O. Luna, A. J. H. de O. Luna, A., Kruchten, P., & P. de Moura, H. (2015). Agile Governance Theory: conceptual development.

- Jabbari, R. , Ali, N., Petersen, K., & Tanveer, B. (2018). Towards a benefits dependency network for devops based on a systematic literature review. Journal of Software Evolution and Process, 30(11). [CrossRef]

- Jayakody, J. (2023). Critical success factors for DevOps adoption in information systems development. International Journal of Information Systems and Project Management, 11(3), 60-82. [CrossRef]

- Jayakody, J. (2023). Critical success factors for DevOps adoption in information systems development. International Journal of Information Systems and Project Management, 11(3), 60-82. [CrossRef]

- Jayakody, J. and Wijayanayake, W. (2022). DevOps adoption in information systems projects; a systematic literature review. International Journal of Software Engineering & Applications, 13(3), 39-53. [CrossRef]

- Jindal, A and Mamatha, G.S. (2024). The Future of DevOps Compute: A Survey of Innovative Strategies for Efficient Resource Utilization – IJSREM. [online] Available at: https://ijsrem.com/download/the-future-of-devops-compute-a-survey-of-innovative-strategies-for-efficient-resource-utilization/ [Accessed 15 Jan. 2025].

- Kaledio, P. , & Lucas, D. (2024). Agile DevOps Practices: Implement agile and DevOps methodologies to streamline development, testing, and deployment processes.

- Karampatsis, P. , Malesios, C., & Deligiannis, I. (2020). Leadership styles and DevOps: A systematic mapping study. Proceedings of the 2020 ACM/IEEE International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement (ESEM), 1–11.

- Khan, A. and Shameem, M. (2020). Multicriteria decision-making taxonomy for DevOps challenging factors using analytical hierarchy process. Journal of Software Evolution and Process, 32(10). [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. (2020). Fast delivery, continuous build, testing, and deployment with DevOps pipeline techniques on the cloud. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, 13(5), 552-575. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. , Khan, A., Khan, F., Khan, M., & Whangbo, T. (2022). Critical challenges to adopting DevOps culture in software organizations: a systematic review. Ieee Access, 10, 14339-14349. [CrossRef]

- Khattak, K. (2023). A systematic framework for addressing critical challenges in adopting DevOps culture in software development: a pls-sem perspective. Ieee Access, 11, 120137-120156. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. (2023). Multicriteria decision-making–based framework for implementing devops practices: a fuzzy best–worst approach. Journal of Software Evolution and Process, 36(6). [CrossRef]

- Leffingwell, D. (2010). Agile software requirements: lean requirements practices for teams, programs, and the enterprise. Addison-Wesley Professional.

- Leminen, R. (2023). Business value optimisation in agile software development.

- Lestari, M. , Iriani, A., & Hendry, H. (2022). Information technology governance design in DevOps-based e-marketplace companies using Cobit 2019 framework. Intensif Jurnal Ilmiah Penelitian Dan Penerapan Teknologi Sistem Informasi, 6(2), 233-252. [CrossRef]

- Lowrance, S. (2009). Pmo Lite for Colorado Housing and Finance Authority.

- Mahmood Khan, P. , M Sufyan Beg, M., & Ahmad, M. (2014). Sustaining IT PMOs during Cycles of Global Recession.

- Mahon, J. F., & Jones, N. B. (2016). The challenge of knowledge corruption in high velocity, turbulent environments. VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, 46(4), 508-523.

- Maroukian, K. & Gulliver, S. (2020). Leading DevOps Practice and Principle Adoption. 9th International Conference on Information Technology Convergence and Services (ITCSE 2020), May 30~31, 2020, Vancouver, Canada Volume Editors : David C. Wyld, Natarajan Meghanathan (Eds) ISBN : 978-1-925953-19-0.

- Mason, R. , Masters, W., & Stark, A. (2017). Teaching Agile Development with DevOps in a Software Engineering and Database Technologies Practicum.

- Meedeniya, D. , Rubasinghe, I., & Perera, I. (2019). Traceability establishment and visualization of software artefacts in devops practice: a survey. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 10(7). [CrossRef]

- Melgar, Á. (2021). DevOps as a culture of interaction and deployment in an insurance company. Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education (Turcomat), 12(4), 1701-1708. [CrossRef]

- Menon, V. , Sinha, R., & MacDonell, S. (2021). Architectural Challenges in Migrating Plan-driven Projects to Agile.

- Moeez, M. (2024). Comprehensive analysis of DevOps: integration, automation, collaboration, and continuous delivery. BBE, 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Morais, R., Valente, M. T., & Seguro, J. (2020). Security culture in DevOps. Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Evaluation of Novel Approaches to Software Engineering (ENASE 2020), 489–496.

- Narang, P. and Mittal, P. (2022). Performance assessment of traditional software development methodologies and DevOps automation culture. Engineering Technology & Applied Science Research, 12(6), 9726-9731. [CrossRef]

- Nkukwana, S. & H. D. Terblanche, N. (2017). Between a rock and a hard place : management and implementation teams’ expectations of project managers in an agile information systems delivery environment.

- Orozco-Garcés, C. , Pardo, C., & Monsalve, E. (2022). Metrics model to complement the evaluation of devops in software companies. Revista Facultad De Ingeniería, 31(62), e14766. [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Garcés, C. , Pardo, C., & Salazar-Mondragón, Y. (2022). What is there about DevOps assessment? A systematic mapping. Revista Facultad De Ingeniería, 31(59), e13896. [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Fernandez, I., Sestelo, M., Burguillo, J. C., & Piñón-Blanco, C. (2024). Network intrusion detection system for DDoS attacks in ICS using deep autoencoders. Wireless Networks, 30(6), 5059-5075.

- Osmundsen, K. and Bygstad, B. (2021). Making sense of the continuous development of digital infrastructures. Journal of Information Technology, 37(2), 144-164. [CrossRef]

- Pardo, C. J. , Salazar-Mondragón, Y. H., & Orozco-Garcés, C. E. (2022). DevOps model in practice: Applying a novel reference model to support and encourage the adoption of DevOps in a software development company as case study. Ingeniería e Investigación, 42(2), 48–55.

- Pardo, C. , Guerrero, J., & Monsalve, E. (2022). DevOps model in practice: applying a novel reference model to support and encourage the adoption of DevOps in a software development company as a case study. Periodicals of Engineering and Natural Sciences (Pen), 10(3), 221. [CrossRef]

- Philbin, S. P. & Philbin, S. P. (2016). Exploring the Project Management Office (PMO)–Role, Structure and Processes.

- Rafi, S. , Akbar, M., AlSanad, A., AlSuwaidan, L., Al-Alshaikh, H., & AlSagri, H. (2022). Decision-making taxonomy of DevOps success factors using preference ranking organization method of enrichment evaluation. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 2022, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Rafi, S. , Akbar, M., Mahmood, S., Alsanad, A., & Alothaim, A. (2022). Selection of devops best test practices: a hybrid approach using ism and fuzzy topics analysis. Journal of Software Evolution and Process, 34(5). [CrossRef]

- Rafi, S. , Akbar, M., Mahmood, S., Alsanad, A., & Alothaim, A. (2022). Selection of devops best test practices: a hybrid approach using ism and fuzzy topsis analysis. Journal of Software Evolution and Process, 34(5). [CrossRef]

- Romero, E., Camacho, C., Montenegro, C., Acosta, O., Crespo, R., Gaona, E., … & Martínez, M. (2022). Integration of devops practices on a noise monitor system with circleci and terraform. Acm Transactions on Management Information Systems, 13(4), 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Rowse, M. and Cohen, J. (2021). A survey of DevOps in the South African software context. [CrossRef]

- Salih, A. (2023). Adopting devops practices: an enhanced unified theory of acceptance and use of technology framework. International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering (Ijece), 13(6), 6701. [CrossRef]

- Shahin, M. , Nasab, A., & Babar, M. (2021). A qualitative study of architectural design issues in devops. Journal of Software Evolution and Process, 35(5). [CrossRef]

- Simpson, C. (2023). Scalable, flexible implementation of mbse and devops in vses: design considerations and a case study. Incose International Symposium, 33(1), 1044-1056. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S. (2024). The integration of AI and DevOps in the field of information technology and its prospective evolution in the United States. International Journal for Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology, 12(2), 33-37. [CrossRef]

- Sultan, M. (2024). Engineering stakeholders’ viewpoint-concerns for architecting a modern enterprise. [CrossRef]

- Tanzil, M. , Sarker, M., Uddin, G., & Iqbal, A. (2022). A mixed method study of devops challenges. SSRN Electronic Journal. [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. J. (2018) Business models and dynamic capabilities, Long Range Planning, Volume 51, Issue 1, 2018, Pages 40-49,ISSN 0024-6301. [CrossRef]

- Weeraddana, N. (2023). An empirical comparison of ethnic and gender diversity of DevOps and non-DevOps contributions to open-source projects. Empirical Software Engineering, 28(6). [CrossRef]

- Wiedemann, A. (2018). It governance mechanisms for devops teams - how incumbent companies achieve competitive advantages. [CrossRef]

- Wiedemann, A. , Wiesche, M., Gewald, H., & Krcmar, H. (2020). Understanding how DevOps align development and operations: a tripartite model of intra-it alignment. European Journal of Information Systems, 29(5), 458-473. [CrossRef]

- Yazdi, M. (2024). Reliability-Centered Design and System Resilience. In Advances in Computational Mathematics for Industrial System Reliability and Maintainability (pp. 79-103). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Zhou, X. , Mao, R., Zhang, H., Dai, Q., Huang, H., Shen, H., … & Rong, G. (2023). Revisit security in the era of devops: an evidence-based inquiry into devsecops industry. Iet Software, 17(4), 435-454. [CrossRef]

- Zohaib, M. (2024). Prioritizing DevOps implementation guidelines for sustainable software projects. Ieee Access, 12, 71109-71130.

|

Sensing (DCF) |

Seizing (DCF) |

Seizing (DCF) |

Seizing (DCF) |

Transforming/ Reconfiguring (DCF) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Dimension (ADRM) |

Principle (ADRM) |

Practice (ADRM) |

Culture* |

Value (ADRM) |

| Ease & Simplicity | Microservices Approach |

Collaboration [Improved Pace of Delivery] |

||

| Removal of SPOF | ||||

| Availability & Capacity | ||||

| Tailor-Made Functionalities | ||||

| Team Velocity | ||||

| Agility | Minimum Viable Experience (MVE) Culture |

Adaptation [Continuous Improvement] |

||

| Learning Curve | ||||

| Knowledge Management | ||||

| Expanding Capabilities | ||||

| Customer Experience (CX) | ||||

| Dynamic Coding | Continuous Value Stream Integration |

Value Delivery [Enhanced Quality & Reliability] |

||

| Central Repository | ||||

| Lean Time Metrics [Value Added (VA) & Lead Time (LT)] | ||||

| Completion & Accuracy [%Complete/Accurate (%C/A)] | ||||

| Lean | ||||

| Programmability | Automated Configuration [Infrastructure as Code (IaC)] |

Automation [More Efficient & Effective Operations] |

||

| Idempotence | ||||

| Version Control | ||||

| Standardized Patterns | ||||

| Performance Measurement | ||||

| Deployability | Continuous Delivery |

Outcome-focused [Deployment Artifact (Build, Test, Release)] |

||

| Modifiability | ||||

| Testability | ||||

| Automated Testing | ||||

| Emerging Technology Adoption |

| Value | HI95 | HI99 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SRMR | 0.0597 | 0.0448 | 0.0500 |

| dULS | 1.6563 | 0.9339 | 1.1630 |

| dG | 1.0717 | 0.5337 | 0.6255 |

| Construct | Dijkstra-Henseler’s rho (ρA) | Jöreskog’s rho (ρc) | Cronbach’s alpha(α) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MS1 | 0.8638 | 0.8610 | 0.8624 |

| MVE2 | 0.9140 | 0.9034 | 0.9048 |

| CVS3 | 0.8795 | 0.8776 | 0.8781 |

| AC4 | 0.8755 | 0.8661 | 0.8680 |

| CD5 | 0.8610 | 0.8574 | 0.8584 |

| PMO Gov6 | 0.8849 | 0.8826 | 0.8825 |

| Construct | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|

| MS1 | 0.5543 |

| MVE2 | 0.6549 |

| CVS3 | 0.5897 |

| AC4 | 0.5671 |

| CD5 | 0.5472 |

| PMO Gov6 | 0.6014 |

| Construct | MS1 | MVE2 | CVS3 | AC4 | CD5 | PMO Gov6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS1 | 0.5543 | |||||

| MVE2 | 0.3596 | 0.6549 | ||||

| CVS3 | 0.2463 | 0.2357 | 0.5897 | |||

| AC4 | 0.2222 | 0.2844 | 0.3720 | 0.5671 | ||

| CD5 | 0.2190 | 0.2029 | 0.3166 | 0.2901 | 0.5472 | |

| PMO Gov6 | 0.4174 | 0.4634 | 0.4665 | 0.5571 | 0.4405 | 0.6014 |

| Construct | MS1 | MVE2 | CVS3 | AC4 | CD5 | PMO Gov6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS1 | ||||||

| MVE2 | 0.5999 | |||||

| CVS3 | 0.4937 | 0.4774 | ||||

| AC4 | 0.4705 | 0.5338 | 0.6019 | |||

| CD5 | 0.4644 | 0.4419 | 0.5584 | 0.5267 | ||

| PMO Gov6 | 0.6427 | 0.6739 | 0.6760 | 0.7437 | 0.6651 |

| Construct | Coefficient of determination (R2) | Adjusted R2 |

|---|---|---|

| PMO Gov6 | 0.7652 | 0.7615 |

| t-values | p-values | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| t < 1.28 | p > 0.10 | Not significant |

| 1.28 < t < 1.65 | 0.10 > p > 0.05 | Moderate |

| 1.65 < t < 2.33 | 0.05 > p > 0.01 | Significant |

| t > 2.33 | p < 0.01 | Very significant |

| Effect | Original coefficient | Standard bootstrap results | Percentile bootstrap quantiles | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean value | Standard error | t-value | p-value (2-sided) | p-value (1-sided) | 0.5% | 2.5% | 97.5% | 99.5% | ||

| MS1 -> PMO Gov6 | 0.1750 | 0.1845 | 0.0696 | 2.5125 | 0.0121 | 0.0061 | -0.0025 | 0.0362 | 0.3153 | 0.3694 |

| MVE2 -> PMO Gov6 | 0.2244 | 0.2194 | 0.0622 | 3.6072 | 0.0003 | 0.0002 | 0.0414 | 0.1011 | 0.3422 | 0.3856 |

| CVS3 -> PMO Gov6 | 0.1696 | 0.1700 | 0.0660 | 2.5719 | 0.0103 | 0.0051 | 0.0027 | 0.0354 | 0.2953 | 0.3352 |

| AC4 -> PMO Gov6 | 0.3286 | 0.3249 | 0.0737 | 4.4585 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.1308 | 0.1775 | 0.4657 | 0.5072 |

| CD5 -> PMO Gov6 | 0.2083 | 0.2103 | 0.0618 | 3.3727 | 0.0008 | 0.0004 | 0.0387 | 0.0875 | 0.3401 | 0.3715 |

| Code | Relationship | Type | β-value | t-value | Supported? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Microservices -> PMO Governance | Direct | 0.175 | 2.5125 | Yes |

| H2 | MVE Culture -> PMO Governance | Direct | 0.2244 | 3.6072 | Yes |

| H3 | Continuous Value Stream -> PMO Governance | Direct | 0.1696 | 2.5719 | Yes |

| H4 | Automated Configuration -> PMO Governance | Direct | 0.3286 | 4.4585 | Yes |

| H5 | Continuous Delivery/Deployment -> PMO Governance | Direct | 0.2083 | 3.3727 | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).