Submitted:

26 August 2025

Posted:

27 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Explanation of Logical Implementation

2.3. Quality Assurance and Quality Control

2.3.1. DOI Extraction and Literature Title Recognition Module

2.3.2. Neural Networks Entity Recognition Module

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Discussion on Species-Specific Sensitivity to 6PPD, 6PPD-Q, and DNPD

3.2. Discussion on Toxicity Data of PPDs and PPDs-Q in Global Aquatic Media and Organismal Media

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maringer, L.; Roiser, L.; Wallner, G.; Nitsche, D.; Buchberger, W. The role of quinoid derivatives in the UV-initiated synergistic interaction mechanism of HALS and phenolic antioxidants. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2016, 131, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Kiki, C.; Xu, Z.; Manzi, H.P.; Rashid, A.; Chen, T.; Sun, Q. Comparative growth inhibition of 6PPD and 6PPD-Q on microalgae Selenastrum capricornutum, with insights into 6PPD-induced phototoxicity and oxidative stress. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 957, 177627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maji, U.; Kim, K.; Yeo, I.; Shim, K.; Jeong, C. Toxicological Effects of Tire Rubber-Derived 6PPD-Quinone, a Species-Specific Toxicant, and Dithiobisbenzanilide (DTBBA) in the Marine Rotifer Brachionus koreanus. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2023, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosser, R.; Salole, J.; Hang, S. Toxicity of 6PPD-quinone to Four Freshwater Invertebrate Species. Environmental Pollution 2023, 337, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosser, R.; Bartlett, A.; Milani, D.; Holman, E.; Ikert, H.; Schissler, D.; Toito, J.; Parrott, J.; Gillis, P.; Balakrishnan, V. Variation in the Toxicity of Sediment-Associated Substituted Phenylamine Antioxidants to an Epibenthic (Hyalella azteca) and Endobenthic (Tubifex tubifex) Invertebrate. Chemosphere 2017, 181, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calle, L.; Le Du-Carree, J.; Martinez, I.; Sarih, S.; Montero, D.; Gomez, M.; Almeda, R. Toxicity of Tire Rubber-Derived Pollutants 6PPD-Quinone and 4-Tert-Octylphenol on Marine Plankton. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2025, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosser, R.; Salole, J.; Hang, S. Toxicity of 6PPD-quinone to Four Freshwater Invertebrate Species. Environmental Pollution 2023, 337, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, B.; Marlatt, V.; Liao, X.; Reger, S.; Gallilee, C.; Brown, T. Acute Toxicity of 6PPD-Quinone to Early Life Stage Juvenile Chinook (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) and Coho (Oncorhynchus kisutch) Salmon. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 2023, 42, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiki, K.; Yamamoto, H. The Tire-Derived Chemical 6PPD-quinone Is Lethally Toxic to the White-Spotted Char Salvelinus leucomaenis pluvius but not to Two Other Salmonid Species. Environmental Science & Technology Letters, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Philibert, D.; Stanton, R.; Tang, C.; Stock, N.; Benfey, T.; Pirrung, M.; De Jourdan, B. The Lethal and Sublethal Impacts of Two Tire Rubber-Derived Chemicals on Brook Trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) Fry and Fingerlings. Chemosphere 2024, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C.; Lin, J.; Kohlman, E.; Jain, N.; Amekor, M.; Alcaraz, A.; Hogan, N.; Hecker, M.; Brinkmann, M. Acute and Subchronic Toxicity of 6PPD-Quinone to Early Life Stage Lake Trout (Salvelinus namaycush). Environmental Science & Technology 2025, 59, 791–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y.; Qi, P.; Wang, Z.; Xu, H.; Jin, Y.; Wang, X. Chiral Perspective Evaluations: Enantioselective Hydrolysis of 6PPD and 6PPD-Quinone in Water and Enantioselective Toxicity to Gobiocypris rarus and Oncorhynchus mykiss. Environment International 2022, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greer, J.; Dalsky, E.; Lane, R.; Hansen, J. Establishing an In Vitro Model to Assess the Toxicity of 6PPD-Quinone and Other Tire Wear Transformation Products. Environmental Science & Technology Letters 2023, 10, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Co., M. Co., M. Initial Submission: Acute Toxicity of Santoflex 13 to Rainbow Trout and Bluegill with Cover Letter Dated 081492. Technical Report EPA/OTS 88-920007606, Monsanto Co., 1977.

- Prosser, R.; Salole, J.; Hang, S. Toxicity of 6PPD-quinone to Four Freshwater Invertebrate Species. Environmental Pollution 2023, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, M.; Montgomery, D.; Selinger, S.; Miller, J.; Stock, E.; Alcaraz, A.; Challis, J.; Weber, L.; Janz, D.; He, M. Acute Toxicity of the Tire Rubber-Derived Chemical 6PPD-Quinone to Four Fishes of Commercial, Cultural, and Ecological Importance. Environmental Science & Technology Letters 2022, 9, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Chen, Z.; Ou, S.; Liu, Q.; Lin, S.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z. Neurological Impairment is Crucial for Tire Rubber-Derived Contaminant 6PPDQ-induced Acute Toxicity to Rainbow Trout. Science Bulletin 2024, 69, 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosser, R.; Gillis, P.; Holman, E.; Schissler, D.; Ikert, H.; Toito, J.; Gilroy, E.; Campbell, S.; Bartlett, A.; M, D. Effect of Substituted Phenylamine Antioxidants on Three Life Stages of the Freshwater Mussel Lampsilis siliquoidea. Environmental Pollution 2017, 229, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, C.; Lin, J.; Kohlman, E.; Jain, N.; Amekor, M.; Alcaraz, A.; Hogan, N.; Hecker, M.; Brinkmann, M. Acute and Subchronic Toxicity of 6PPD-Quinone to Early Life Stage Lake Trout (Salvelinus namaycush). Environmental Science & Technology 2025, 59, 791–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiki, K.; Yamamoto, H. The Tire-Derived Chemical 6PPD-quinone Is Lethally Toxic to the White-Spotted Char Salvelinus leucomaenis pluvius but not to Two Other Salmonid Species. Environmental Science & Technology Letters, 2022; 6. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of the Environment, J. Results of Aquatic Toxicity Tests of Chemicals Conducted by Ministry of the Environment in Japan (March 2019). Technical report, Ministry of the Environment, Japan, 2019.

- Co., M. Dynamic Toxicity of Santoflex 13 to Fatheads Minnows (Pimephales promelas). Technical report, Monsanto, St. Louis, MO, USA, 1979.

- Rao, C.; Chu, F.; Fang, F.; Xiang, D.; Xian, B.; Liu, X.; Bao, S.; Fang, T. Toxic Effects and Comparison of Common Amino Antioxidants (AAOs) in the Environment on Zebrafish: A Comprehensive Analysis Based on Cells, Embryos, and Adult Fish. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, N.; Hou, S.; Sun, S.; Cao, R.; Zhang, H.; Lu, X.; Zhang, S.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y. A Nationwide Investigation of Substituted p-Phenylenediamines (PPDs) and PPD-Quinones in the Riverine Waters of China. Environmental Science & Technology 2025, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Wu, F.; Zhao, Z.; Ye, T.; Luo, X.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, H. Effects of environmental concentrations of 6PPD and its quinone metabolite on the growth and reproduction of freshwater cladoceran. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 948, 175018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Zhang, Z.; Zeb, A.; Fu, X.; Shi, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, Q.; Chen, C.; Sun, W.; et al. Environmental occurrence, fate, human exposure, and human health risks of p-phenylenediamines and their quinones. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 957, 177742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Nie, C.; Liu, J.; Zeng, J.; Tian, M.; Chen, Z.; Huang, M.; Lu, Z.; Sun, Y. Occurrence, fate and chiral signatures of p-phenylenediamines and their quinones in wastewater treatment plants, China. Water Research 2025, 276, 123272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somepalli, K.; Andaluri, G. Spatiotemporal distribution and environmental risk assessment of 6PPDQ in the Schuylkill River. Emerging Contaminants 2025, 11, 100501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Sun, S.; Xu, P.; Du, L.; Sun, C.; Feng, F.; Feng, T.; Yao, X.; Cui, Z.; Liang, D.; et al. Rubber additives and relevant oxidation products in groundwater in a central China region: Levels, influencing factors and exposure. Environmental Pollution 2024, 363, 125155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.J.; Liu, S.; Wang, M.; Wu, N.N.; Xu, R.; Wei, L.N.; Xu, X.R.; Zhao, J.L.; Xing, P.; Li, H.; et al. Nationwide occurrence and prioritization of tire additives and their transformation products in lake sediments of China. Environment International 2024, 193, 109139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, R.; Venier, M.; Chen, Q.; Yang, J.; Liu, M.; Wu, Y. Amino antioxidants: A review of their environmental behavior, human exposure, and aquatic toxicity. Chemosphere 2023, 317, 137913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.H.; Mei, Y.X.; Liang, X.N.; Ge, Z.Y.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, H.Y.; Zhao, J.L.; Liu, A.; Shi, C.; Ying, G.G. Small-Intensity Rainfall Triggers Greater Contamination of Rubber-Derived Chemicals in Road Stormwater Runoff from Various Functional Areas in Megalopolis Cities. Environmental Science & Technology 2024, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Yuan, L.; Sun, J.; Yang, M.I.; Khan, I.; Lopez, J.J.; Gong, Y.; Nair, P.; Hao, C.; Helm, P.; et al. Compound Class-Specific Temporal Trends (2021–2023) of Tire Wear Compounds in Suspended Solids from Toronto Wastewater Treatment Plants. ACS ES&T Water 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J.; Wu, P.; Qiao, H.; Li, H.; Huang, G.; Yang, Z.; Cai, Z. Occurrence and Removal of Substituted p-Phenylenediamine-Derived Quinones in Hong Kong Sewage Treatment Plants. Environmental Science & Technology 2023, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Guo, R.; Ren, F.; Jiang, S.; Jin, H. p-Phenylenediamine Derivatives in Tap Water: Implications for Human Exposure. Water 2024, 16, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Xia, Y.; Wang, X.; Zou, Y.; Li, Z.; Man, M.; Yang, Q.; Lv, M.; Ding, J.; Chen, L. Development and application of diffusive gradients in thin-films for in-situ monitoring of 6PPD-Quinone in urban waters. Water Research 2024, 266, 122408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, G.P.; Parsia, M.D.; Uychutin, M.; Lane, R.; Orlando, J.L.; Hladik, M.L. 6PPD-quinone in water from the San Francisco–San Joaquin Delta, California, 2018–2024. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2025, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiwert, B.; Nihemaiti, M.; Troussier, M.; Weyrauch, S.; Reemtsma, T. Abiotic oxidative transformation of 6 - PPD and 6 - PPD quinone from tires and occurrence of their products in snow from urban roads and in municipal wastewater. Water Research 2022, 212, 118122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, T.F.M.; Wang, Y.; Humes, C.; Jeronimo, M.; Johannessen, C.; Spraakman, S.; Giang, A.; Scholes, R.C. Bioretention Cells Provide a 10-Fold Reduction in 6PPD-Quinone Mass Loadings to Receiving Waters: Evidence from a Field Experiment and Modeling. Environmental Science & Technology Letters 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, M.S.; Kim, S.H.; Hyun, M.; Han, S.M.; Kim, Y.H. Development of a quantitative analytical method for 6PPD, a harmful tire antioxidant, in biological samples for toxicity assessment. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2025, 296, 118171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Huang, Z.; Liu, Y.H.; Hu, L.X.; He, L.Y.; Liu, Y.S.; Zhao, J.L.; Ying, G.G. Occurrence and risks of 23 tire additives and their transformation products in an urban water system. Environment International 2023, 171, 107715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Liang, G.; Wang, D. Potential human health risk of the emerging environmental contaminant 6-PPD quinone. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 949, 175057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prosser, R.; Salole, J.; Hang, S. Toxicity of 6PPD-quinone to four freshwater invertebrate species. Environmental Pollution 2023, 337, 122512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Zhao, S.; Liu, X.; Tian, L.; Mo, Y.; Yi, X.; Liu, S.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, G. Aquatic environmental fates and risks of benzotriazoles, benzothiazoles, and p-phenylenediamines in a catchment providing water to a megacity of China. Environmental Research 2023, 216, 114721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Tang, S.; Wong, J.W.; Luo, Z.; Li, Z.; Thai, P.K.; Zhu, M.; Yin, H.; Niu, J. Degradation and detoxification of 6PPD-quinone in water by ultraviolet-activated peroxymonosulfate: Mechanisms, byproducts, and impact on sediment microbial community. Water Research 2024, 263, 122210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannessen, C.; Metcalfe, C.D. The occurrence of tire wear compounds and their transformation products in municipal wastewater and drinking water treatment plants. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2022, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klauschies, T.; Isanta-Navarro, J. The joint effects of salt and 6PPD contamination on a freshwater herbivore. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 829, 154675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, L.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, L.Y.; Shen, M.; Du, B. Widespread Occurrence and Transport of p-Phenylenediamines and Their Quinones in Sediments across Urban Rivers, Estuaries, Coasts, and Deep-Sea Regions. Environmental Science & Technology 2023, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phylum | Class | Order | Species | LC/EC50 (mg/L) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorophyta | Chlorophyceae | Sphaeropleales | Selenastrum capricornutum (Printz, 1964) | 8.78 | [2] |

| Rotifera | Monogononta | Brachionida | Brachionus koreana (Hwang et al., 2013) | 1 | [3] |

| Arthropoda | Malacostraca | Amphipoda | Hyalella azteca (Saussure, 1858) | 0.017 | [4] |

| Arthropoda | Branchiopoda | Anomopoda | Daphnia magna (Straus, 1820) | 0.042 | [5] |

| Mollusca | Gastropoda | Basommatophora | Paracentrotus lividus (Lamarck, 1816) | 0.0007 | [6] |

| Mollusca | Gastropoda | Basommatophora | Planorbella pilsbryi (F.C. Baker, 1926) | 0.0117 | [7] |

| Mollusca | Bivalvia | Unionida | Megalonaias nervosa (Rafinesque, 1820) | 0.0179 | [7] |

| Echinodermata | Echinoidea | Arbacioida | Arbacia lixula (Linnaeus, 1758) | 0.0008 | [6] |

| Chordata | Actinopterygii | Salmoniformes | Oncorhynchus kisutch (Walbaum, 1792) | 0.000041 | [8] |

| Chordata | Actinopterygii | Salmoniformes | Salvelinus leucomaenis (Pallas, 1814) | 0.00051 | [9] |

| Chordata | Actinopterygii | Salmoniformes | Salvelinus fontinalis (Mitchill, 1814) | 0.00038 | [10] |

| Chordata | Actinopterygii | Salmoniformes | Salvelinus namaycush (Walbaum, 1792) | 0.00039 | [11] |

| Chordata | Actinopterygii | Salmoniformes | Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum, 1792) | 0.00226 | [12] |

| Chordata | Actinopterygii | Salmoniformes | Oncorhynchus tshawytscha (Walbaum, 1792) | 0.0082 | [13] |

| Chordata | Actinopterygii | Perciformes | Lepomis macrochirus (Rafinesque, 1819) | 0.45 | [14] |

| Phylum | Class | Order | Species | LC/EC50 (mg/L) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthropoda | Branchiopoda | Anomopoda | Daphnia magna (Straus, 1820) | 0.0534 | [15] |

| Arthropoda | Insecta | Ephemeroptera | Hexagenia spp. (Charbonneau and Hare, 1998) | 0.042 | [15] |

| Mollusca | Bivalvia | Unionida | Megalonaias nervosa (Rafinesque, 1820) | 0.0180 | [15] |

| Echinodermata | Echinoidea | Arbacioida | Arbacia lixula (Linnaeus, 1758) | 0.012 | [6] |

| Chordata | Actinopterygii | Salmoniformes | Oncorhynchus kisutch (Walbaum, 1792) | 0.0000485 | [8] |

| Chordata | Actinopterygii | Salmoniformes | Salvelinus namaycush (Walbaum, 1792) | 0.00051 | [8] |

| Chordata | Actinopterygii | Salmoniformes | Salvelinus fontinalis (Mitchill, 1814) | 0.00059 | [16] |

| Chordata | Actinopterygii | Salmoniformes | Salvelinus leucomaenis (Pallas, 1814) | 0.0012 | [9] |

| Chordata | Actinopterygii | Salmoniformes | Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum, 1792) | 0.00103 | [17] |

| Chordata | Actinopterygii | Salmoniformes | Oncorhynchus tshawytscha (Walbaum, 1792) | 0.0821 | [13] |

| Phylum | Class | Order | Species | LC/EC50 (mg/L) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthropoda | Malacostraca | Amphipoda | Hyalella azteca (Saussure, 1858) | 0.048 | [5] |

| Arthropoda | Insecta | Ephemeroptera | Hexagenia spp. (Charbonneau and Hare, 1998) | 0.0534 | [4] |

| Mollusca | Bivalvia | Unionida | Megalonaias nervosa (Rafinesque, 1820) | 0.0114 | [4] |

| Mollusca | Bivalvia | Unionida | Lampsilis siliquoidea (Barnes, 1823) | 0.047 | [18] |

| Chordata | Actinopterygii | Salmoniformes | Salvelinus namaycush (Walbaum, 1792) | 0.00051 | [19] |

| Chordata | Actinopterygii | Salmoniformes | Salvelinus leucomaenis (Pallas, 1814) | 0.0008 | [20] |

| Chordata | Actinopterygii | Salmoniformes | Oncorhynchus tshawytscha (Walbaum, 1792) | 0.067307 | [8] |

| Chordata | Actinopterygii | Beloniformes | Oryzias latipes (Temminck & Schlegel, 1846) | 0.029 | [21] |

| Chordata | Actinopterygii | Cypriniformes | Gobiocypris rarus (Ye et al., 1983) | 0.162 | [12] |

| Chordata | Actinopterygii | Cypriniformes | Pimephales promelas (Rafinesque, 1820) | 0.48 | [22] |

| Chordata | Actinopterygii | Cypriniformes | Danio rerio (Hamilton, 1822) | 1 | [23] |

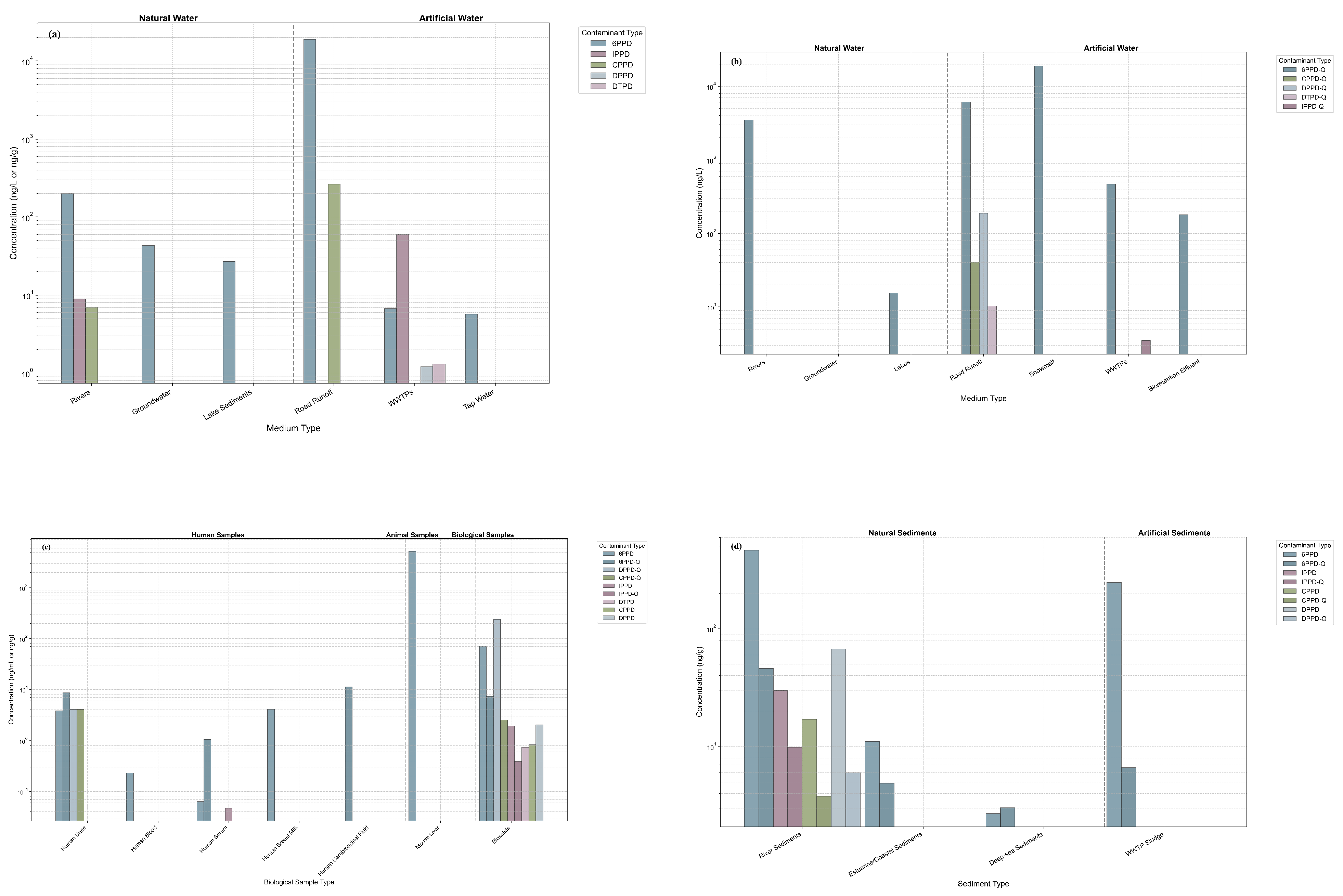

| Contaminant Name | Medium Type | Details | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6PPD | Natural water - Rivers | Chinese rivers: concentrations not specified (Liuxi River, Pearl River, Dongjiang River); Washington rivers (USA): 35-200 ng/L; Miller Creek (USA): ug/L; Schuylkill River (USA): not detected to 17.95 ng/L; Don River (Canada): concentrations not specified; Jiaojiang River: 4.0-72 ng/L | [24,25,26,27,28] |

| 6PPD | Natural water - Groundwater | Kaifeng area (China): ND-43.0 ng/L, mean value 4.05 ng/L | [29] |

| 6PPD | Natural water - Lakes | Sediments in China’s five major lake regions: <0.045-27 ng/g | [30] |

| 6PPD | Artificial water - Road runoff | Seattle (USA): 800-19,000 ng/L; Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area (China): maximum 907 ng/L | [31,32] |

| 6PPD | Artificial water - WWTPs | Guangzhou Plant A influent: 0.29-3.11 ng/L; effluent: <MDL-0.16 ng/L; Guangzhou Plant B influent: 1.46-6.69 ng/L; effluent: 0.07-0.16 ng/L; Hong Kong influent: 1.1 - 59 ng/L; effluent: <LOQ - 15 ng/L; Suspended solids in Toronto WWTPs: WWTP A ng/g dw; WWTP B ng/g dw | [27,33,34] |

| 6PPD | Artificial water - Tap water | Hangzhou (China): <LOD - 5.7 ng/L (mean: 0.79 ng/L); Taizhou (China): <LOD - 2.6 ng/L (mean: 0.93 ng/L) | [35] |

| IPPD | Natural water - Rivers | Jiaojiang River: <LOD-8.9 ng/L; Liuxi River (China): 0.658-3.85 ng/L | [35,36] |

| IPPD | Artificial water - WWTPs | Hong Kong influent: 0.63 - 33 ng/L; effluent: 0.13 - 28 ng/L; Malaysia influent: not detected–60 ng/L; effluent: not detected–47 ng/L; Sri Lanka influent: 0.63–2.4 ng/L; effluent: 1.2–3.6 ng/L | [34,37] |

| CPPD | Natural water - Rivers | Jiaojiang River: <LOD-7.0 ng/L | [36] |

| CPPD | Artificial water - Road runoff | Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area (China): maximum 265 ng/L | [32] |

| DPPD | Artificial water - WWTPs | Hong Kong influent: 0.39 - 1.2 ng/L; effluent: <LOQ - 0.28 ng/L | [34] |

| DTPD | Artificial water - WWTPs | Hong Kong influent: <LOQ - 1.3 ng/L; effluent: <LOQ - 0.3 ng/L | [34] |

| Contaminant Name | Medium Type | Details | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6PPD-Q | Natural water - Rivers | Chinese rivers: 0.26-11.3 ng/L; Canadian rivers: 290-890 ng/L; American rivers: 200-3500 ng/L; Australian rivers: 0.38-88 ng/L; Guangdang River (Yantai): ng/L; Xin’an River: ng/L; Yu’niao River: ng/L; Urban rivers in the Pearl River Delta: 7.20-34.5 ng/L; Upper reaches of Shenchong River (Guangzhou): ng/L; Discharge point: ng/L; Downstream: ng/L; Upper reaches of Tianma River (Guangzhou): ng/L; Discharge point: ng/L; Downstream: ng/L; Schuylkill River (USA): not detected to 17.95 ng/L; Don River (Canada, during rainstorms): ug/L; GTA streams (wet season): 5.6-82.3 ng/L; (dry season): <2.0-8.4 ng/L; Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta (USA): 0.43-21 ng/L | [26,27,28,32,37,38,39] |

| 6PPD-Q | Natural water - Groundwater | Guanghua Basin (China): detection frequency > 70% | [35] |

| 6PPD-Q | Natural water - Lakes | Nearshore waters of Lake Ontario (Canada): Toronto Harbour 2.4-2.55 ng/L; Near Humber Bay Park 2.8-15.5 ng/L | [32] |

| 6PPD-Q | Artificial water - Road runoff | Seattle (USA): 6.1 ug/L; 0.8-19 ug/L; High-traffic areas in Hong Kong (China): 2.43 ug/L; 1.9-470 ng/L; Los Angeles (USA): 4100-6100 ng/L; 4.1-6.1 ug/L; San Francisco creeks (USA): 1.0-3.5 ug/L; Huizhou (China): 38.5-1562 ng/L; Dongguan (China): 38.5-1562 ng/L; Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area (China): 1.6–940 ng/L; Roads around Guelph (Canada): 0.05-0.20 ug/L | [25,32,38,40,41,42,43] |

| 6PPD-Q | Artificial water - Snowmelt | Seattle (USA): 19.0 ug/L; Snowmelt in Yantai (grab sampling): 67.4-129 ng/L; (DGT detection): 210 ng/L; Cold-climate cities in Canada: 367 ng/L (average); 0.08-0.37 ug/L; Leipzig (Germany): 110-428 ng/L | [28,39,44,45] |

| 6PPD-Q | Artificial water - WWTPs | A WWTP in Germany (influent): snowmelt period ug/L; rainfall period ug/L; Guangzhou Plant A influent: 1.33-10.5 ng/L; effluent: 0.06-1.77 ng/L; Guangzhou Plant B influent: 2.49-10.0 ng/L; effluent: 0.90-3.08 ng/L; Hong Kong influent: 1.9-470 ng/L; effluent: 1.1-37 ng/L; Southern Ontario (Canada) influent: ng/POCIS - ng/POCIS; effluent: ng/POCIS - ng/POCIS; Suspended solids in Toronto WWTPs: WWTP A ng/g dw; WWTP B ng/g dw | [27,33,34,38,46] |

| 6PPD-Q | Artificial water - Bioretention cell effluent | Vancouver (Canada): peak value 150 ng/L; simulated MEC range 23-180 ng/L | [47] |

| IPPD-Q | Artificial water - WWTPs | Hong Kong influent: 0.36-3.5 ng/L; effluent: 0.06-1.7 ng/L | [34] |

| CPPD-Q | Artificial water - Road runoff | Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area (China): ND–40.7 ng/L | [32] |

| DPPD-Q | Artificial water - Road runoff | Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area (China): ND–189 ng/L | [32] |

| DTPD-Q | Artificial water - Road runoff | Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area (China): ND–10.3 ng/L | [32] |

| Contaminant Name | Biological Type | Details | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6PPD | Human - Urine | Pregnant women in southern China: median 0.068 ng/mL; adults: 0.018 ng/mL; children: 0.015 ng/mL; Quzhou (China): 0.41-3.8 ng/mL; Guangzhou (China): <LOD-0.54 ng/mL | [26,38] |

| 6PPD | Human - Blood | Tianjin (China): <LOD-0.230 ng/mL | [26] |

| 6PPD | Human - Serum | South China: median 0.063 ng/mL | [26] |

| 6PPD | Human - Breast milk | South China: median 4.10 ng/mL | [26] |

| 6PPD | Animal - Mouse liver | Oral exposure for 3h: 1043 pg/uL (100 mg/kg dose), 5236 pg/uL (1000 mg/kg dose); Oral exposure for 9h: 1868 pg/uL (100 mg/kg dose), 4044 pg/uL (1000 mg/kg dose); Intratracheal instillation for 9h: 150 pg/uL (10 mg/kg dose), 339 pg/uL (25 mg/kg dose) | [24] |

| 6PPD-Q | Human - Urine | Pregnant women in southern China: median 2.91 ng/mL; adults: 0.40 ng/mL; children: 0.076 ng/mL; Children in Guangzhou (China): <MQL-0.78 ng/mL; Pregnant women: 0.26-8.58 ng/mL; Adults: 0.055-2.11 ng/mL; Adults in Shanghai (China): 0.14-6.3 ng/mL; General population in Tianjin (China): ND-0.073 ng/mL | [25,38] |

| 6PPD-Q | Human - Serum | Control group in South China: <LOQ-1.06 ng/mL; Adults with S-NAFLD: <LOQ-0.78 ng/mL; General population: 0.11-0.43 ng/mL; median 0.15 ng/mL | [25,26] |

| 6PPD-Q | Human - Cerebrospinal fluid | Parkinson’s patients in Shenzhen (China): median 11.18 ng/mL; Control group: median 5.07 ng/mL | [25] |

| IPPD | Human - Serum | South China: median 0.047 ng/mL | [26] |

| DPPD-Q, CPPD-Q, DNPD-Q | Human - Urine | Tianjin (China): 0.193-4.064 ng/mL | [26] |

| IPPD | Biological sample - Biosolids | 0.25-1.9 ng/g | [34] |

| CPPD | Biological sample - Biosolids | 0.48-0.83 ng/g | [34] |

| 6PPD | Biological sample - Biosolids | 2.1-71 ng/g | [34] |

| DPPD | Biological sample - Biosolids | 0.49-2.0 ng/g | [34] |

| DTPD | Biological sample - Biosolids | 0.53-0.74 ng/g | [34] |

| IPPD-Q | Biological sample - Biosolids | <LOQ-0.39 ng/g | [34] |

| CPPD-Q | Biological sample - Biosolids | 0.35-2.5 ng/g | [34] |

| 6PPD-Q | Biological sample - Biosolids | 2.6-7.3 ng/g | [34] |

| DPPD-Q | Biological sample - Biosolids | 19-240 ng/g | [34] |

| Contaminant Name | Sediment Type | Details | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6PPD | River sediments | Urban rivers in the Pearl River Delta (China): 0.585-468 ng/g; Jiaojiang River (China): 1.6-172 ng/g; Rivers in the Dongjiang River basin (China): median 4.90 ng/g dw | [26,35,36,48] |

| 6PPD | Estuarine/coastal sediments | Pearl River Estuary: 1.49-5.71 ng/g; Coastal areas of the South China Sea: 1.07-11.1 ng/g; Estuaries in the Dongjiang River basin (China): range not specified (PPD median 5.26 ng/g dw) | [35,48] |

| 6PPD | Deep-sea sediments | Deep-sea areas of the South China Sea: <MDL-2.69 ng/g; Okinawa Trough: median 0.77 ng/g dw | [35,48] |

| 6PPD | WWTP sludge | Guangzhou (China): range 9.06-248 ng/g dw (accounting for over 60%); median 35.6 ng/g dw | [35] |

| 6PPD-Q | River sediments | Urban rivers in the Pearl River Delta (China): 1.87-18.2 ng/g; Jiaojiang River (China): <LOD-46 ng/g; Rivers in the Dongjiang River basin (China): nd-5.24 ng/g dw | [25,36,38,48] |

| 6PPD-Q | Estuarine/coastal sediments | Pearl River Estuary: <MDL-4.88 ng/g; median 2.00 ng/g; Coastal areas of the South China Sea: 0.431-2.98 ng/g; Estuaries in the Dongjiang River basin (China): nd-0.62 ng/g dw | [25,48] |

| 6PPD-Q | Deep-sea sediments | Deep-sea areas of the South China Sea: <MDL-3.02 ng/g; median 2.71 ng/g | [25,48] |

| 6PPD-Q | WWTP sludge | Guangzhou (China): median 6.62 ng/g dw | [35] |

| IPPD | River sediments | Urban rivers in the Pearl River Delta (China): <MDL-29.9 ng/g; Jiaojiang River (China): <LOD-22 ng/g | [48] |

| IPPD-Q | River sediments | Urban rivers in the Pearl River Delta (China): 0.434-9.91 ng/g | [48] |

| CPPD | River sediments | Urban rivers in the Pearl River Delta (China): <MDL-5.30 ng/g; Jiaojiang River (China): <LOD-17 ng/g | [48] |

| CPPD-Q | River sediments | Urban rivers in the Pearl River Delta (China): <MDL-3.79 ng/g | [48] |

| DPPD | River sediments | Urban rivers in the Pearl River Delta (China): <MDL-67.1 ng/g; Jiaojiang River (China): <LOD-17 ng/g | [48] |

| DPPD-Q | River sediments | Pearl River Delta (China): <1.2-6.0 ng/g | [26] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).