1. Introduction

The Blue transformation roadmap [

1] aims to strengthen aquatic food system by promoting nutritious food security, sustainable employment, environmental restoration, and socio-economic development. Central to this vision is the emphasis on efficient aquaculture production and improved living conditions for farmed fish, addressing growing consumer concerns. A key objective highlights the need for effective stock management, which is increasingly challenged by intensive fish farming practices that expose fish to multiple stressors, compromising their health and increasing susceptibility to infectious agents.

One of the critical strategies outlined in the roadmap is the prophylactic control of disease through immune system stimulation using immunostimulants, rather than relying on potentially hazardous chemotherapeutics and antibiotics [

2]. Overuse of such chemical treatment’s risks promoting antibiotic-resistant pathogens, bioaccumulation in tissues, and environmental contamination. Although vaccines represent a widely used and effective prophylactic measure, they remain costly for many fish farmers and do not provide broad-spectrum protection against diverse pathogens [

3].

Immunostimulants from various categories have been tested in fish, demonstrating their ability to enhance immunity, protect against diseases, and have minimal environmental impact, thus ensuring the safety of fishery products for consumers. Potential immunostimulants tested in fish include chemicals, bacterial extracts, algal products, as well as animal and plant extracts. A comprehensive review of immunostimulant research across different continents can be found in Subramani

et al., [

4]

Solanum trilobatum (Family: Solanaceae) commonly known as purple-fruited pea eggplant or "Thoothuvalai" in Tamil, is rich in bioactive phytochemicals. It contains alkaloids such as solasodine, which exhibit antimicrobial [

5] and anti-inflammatory properties [

6]. Flavonoids, tannins, and glycosides are also present, contributing to its antioxidant potential [

7]. The leaves and berries are notable for their high content of phenolic compounds and essential amino acids. Additionally, it contains trace elements like iron, calcium, and phosphorus that support its traditional medicinal use in respiratory ailments [

8]. In our previous study, intraperitoneal injection of water-soluble and hexane-soluble fractions of

Solanum trilobatum leaves in

Oreochromis mossambicus enhanced nonspecific immune mechanisms, including serum lysozyme activity and the production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. These fractions also reduced mortality rates following a challenge with live virulent

Aeromonas hydrophila [

9]

Previous studies have identified various bioactive compounds in

S. trilobatum, with key constituents including Epoxylinalol, Himachalol, Illudol, Epibuphanamine, Baimuxinal, and Edulan IV, as determined by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Additionally, nonpolar solvent extraction has revealed the presence of simple phenols, phenolic acids, isoflavones, xanthones, and lignans, as detected using thin-layer chromatography [

7]. One of the primary limitations of natural product efficacy

in vivo is bioavailability. While polar compounds dissolve readily in body fluids and are rapidly excreted, nonpolar compounds tend to persist longer in the system, increasing their potential bioactivity [

10]. Drug candidates have traditionally been selected based on their hydrophobicity, which influences both absorption and retention [

11].

This study evaluates the immunostimulatory efficacy of water-soluble (WSF) and hexane-soluble (HSF) fractions of S. trilobatum administered through feed for 1, 2, and 3 weeks in tilapia (O. mossambicus). Immunological parameters assessed include non-specific immune responses (serum globulin levels, lysozyme activity, antiprotease activity, reactive oxygen species [ROS], reactive nitrogen intermediates [RNI], and myeloperoxidase [MPO] production in peripheral blood leukocytes) as well as the specific immune response (antibody production against Aeromonas hydrophila). Additionally, the ability of these feed supplements twerenhance disease resistance was evaluated through an experimental A. hydrophila challenge.

GC-MS analysis revealed that HSF contained a higher proportion of aromatic compounds (benzenoids) and steroids, mainly phytosterols, while WSF primarily consisted of short-chain alcohol and carbonyl compounds in lower amounts. Due to their hydrophobic nature and higher bioavailability, aromatic and steroid compounds likely contributed to the superior immunostimulatory effects of HSF, enhancing both nonspecific and specific immunity and improving disease resistance. These findings support the use of S. trilobatum HSF as an effective feed supplement for tilapia aquaculture.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fish and Maintenance

Male Oreochromis mossambicus were obtained from a local farmer and were housed in fibre-reinforced plastic (FRP) tanks at a stocking density of 4 g/L kept under ambient temperature and natural light conditions. Water in the tanks was partially replaced every other day to maintain hygiene and stability. Key water quality parameters, such as pH (7.3 ± 0.3) and dissolved oxygen (5.2 ± 0.1 mg/L), were monitored regularly. Before the experiment began, fish were acclimated for two weeks and fed a balanced, lab-prepared diet ad libitum.

2.2. Plant Extract Preparation and Experimental Design

Leaves of

Solanum trilobatum L. (Family: Solanaceae) were processed to obtain water-soluble (WSF) and hexane-soluble fractions (HSF) following earlier protocols [

9]. These extracts were mixed into the fish feed (supplemented feed) at concentrations of 0.01%, 0.1%, and 1% of total feed weight. Control fish received an unsupplemented balanced diet (protein: 39%, carbohydrate: 24%, lipid: 11%, ash: 9%) and fed daily at 2% of their body weight for three weeks. At the end of each week, six fish per group were randomly selected and bled via the common cardinal vein [

12], adhering to the guidelines [

https://ccac.ca/Documents/Standards/Guidelines/Fish.pdf]. Serum from collected blood samples were separated and stored at –20°C in sterile microfuge tubes. Leukocytes were isolated from peripheral blood for immune assays, following previously published methods [

9]

2.3. Nonspecific Immune Response

Serum total protein was estimated by following the method of Lowry

et al., [

13], and albumin levels were determined through the bromocresol green (BCG) dye-binding method [

14]. By subtracting albumin from total protein, the globulin content was determined.

Serum lysozyme activity was determined using the method described by Hutchinson

et al., [

15].

Micrococcus lysodeikticus used as the substrate, and one unit of activity was defined as a decline in absorbance of 0.001 per minute.

Antiprotease activity in serum was assessed following the method of Bowden

et al., [

16] using Na-benzoyl-DL-arginine-p-nitroanilide (BAPNA) as a substrate. Trypsin-mediated hydrolysis produced p-nitroaniline, measured colorimetrically. The percentage of trypsin inhibition was calculated as per Zuo and Woo [

17] using the formula:

The production of superoxide anions by leukocytes was estimated using the nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) reduction assay. The formation of insoluble formazan indicated the level of superoxide activity, and the solubilized product was quantified using a microplate reader [

18]

Nitric oxide (NO) production by peripheral blood leukocytes was quantified using the Griess reaction. Stable nitrite in the supernatant was measured colorimetrically after converting to pink azo dye using Griess reagent [

19]. Nitrite concentration (NO₂⁻) was calculated from a standard curve generated using known concentrations of sodium nitrite.

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) content was determined according to Palić

et al., [

20], with slight adjustments. Neutrophils in head kidney leukocytes were lysed using cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) to release MPO, which catalysed the oxidation of TMB (3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine) in the presence of hydrogen peroxide and absorbance was taken at 450 nm to quantify the reaction.

2.4. Specific Immune Response

A virulent strain of

Aeromonas hydrophila (AHO21) was obtained from Prof. M. R. Chandran, Department of Animal Science, Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli, India. The culture was grown in tryptic soy broth (HiMedia, India), and heat-killed bacterial cells were prepared by adjusting the concentration with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) as per Karunasagar

et al., [

21].

Fish were divided into two sets, each containing ten groups. One group in each set served as control and received a regular diet. The remaining nine groups were fed with diets supplemented with either WSF or HSF of S. trilobatum leaves at 0.01%, 0.1%, or 1% for one, two, or three weeks. At the end of each feeding duration, fish were immunized with the heat-killed A. hydrophila. Blood samples were collected at seven-day intervals using sterile serological tubes (70 × 10 mm) and the serum separated was stored at –20°C in sterile microfuge tubes until used for antibody analysis.

Antibody levels specific to

A. hydrophila were measured using an indirect ELISA method based on Binuramesh

et al., [

22]. After immunization, fish were maintained on a regular control diet during the antibody monitoring period.

2.5. Disease Resistance

A. hydrophila cells were harvested by centrifugation at 800 g for 15 minutes, washed with PBS, and resuspended to the required dose for challenge studies. Fish (n = 10 per group, in triplicate) were fed diets supplemented with WSF or HSF and control groups received an unsupplemented balanced diet. Feeding schedules were grouped into Set I (1 week), Set II (2 weeks), and Set III (3 weeks). After the respective feeding periods, fish were challenged with live A. hydrophila (1 × 10⁸ cells/ fish).

Fish were observed for 15 days post-challenge, and daily mortalities were recorded. Clinical signs included haemorrhagic septicemia, swollen abdomen, and external lesions on the ventral surface. The cause of mortality was confirmed by re-isolating

A. hydrophila from liver samples of 10% of the dead fish, using

Aeromonas isolation medium (HiMedia, India). Following the challenge, the control diet was given to every fish. In accordance with Ellis, [

23], relative percent survival (RPS) was computed using the following formula:

2.6. GC-MS Analysis

The phytochemical analysis of both the fractions of

S. trilobatum leaves were carried out using a GC-MS-QP 2010 system (Shimadzu, Japan) equipped with a thermal desorption system (TD-20). The analytical procedure followed the protocol of Sharma

et al., [

24], with minor modifications. Operating conditions included: injection temperature of 260 °C, ion source temperature of 220 °C, and interface temperature of 270 °C. The initial column oven temperature and flow parameters were maintained as reported in the previous report [

25].

Each compound detected was identified by comparing its retention time and mass spectrum with reference spectra available in the Wiley and NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) libraries. The relative abundance of each constituent was expressed as a percentage of the total peak area.

2.7. In Silico Evaluation of Bioavailability of the Phytoconstituents

To evaluate the oral bioavailability of the major phytoconstituents in the WSF and HSF extracts of

S. trilobatum, a computational analysis was carried out using the Molinspiration Cheminformatics tool (

https://www.molinspiration.com). The molecular structures of the compounds were obtained from the PubChem database

[26] in SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) format. These SMILES entries were uploaded into the Molinspiration platform to generate physicochemical descriptors relevant to drug-likeness and bioavailability.

Key parameters assessed included molecular weight (MW), predicted lipophilicity (miLogP), topological polar surface area (TPSA), number of hydrogen bond donors (nOHNH), and number of hydrogen bond acceptors (nON). The values were interpreted in relation to Lipinski’s Rule of Five, which suggests that compounds are likely to show good oral bioavailability if they meet the following criteria: MW ≤ 500 Da, miLogP ≤ 5, nOHNH ≤ 5, nON ≤ 10, and TPSA < 140 Ų.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

The data were expressed as the arithmetic mean ± standard error (SE). Statistical analysis of the data involved a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s pairwise comparison test. The levels of significance were expressed as p-values less than 0.05, indicating statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Nonspecific Immune Response

3.1.1. Globulin Level

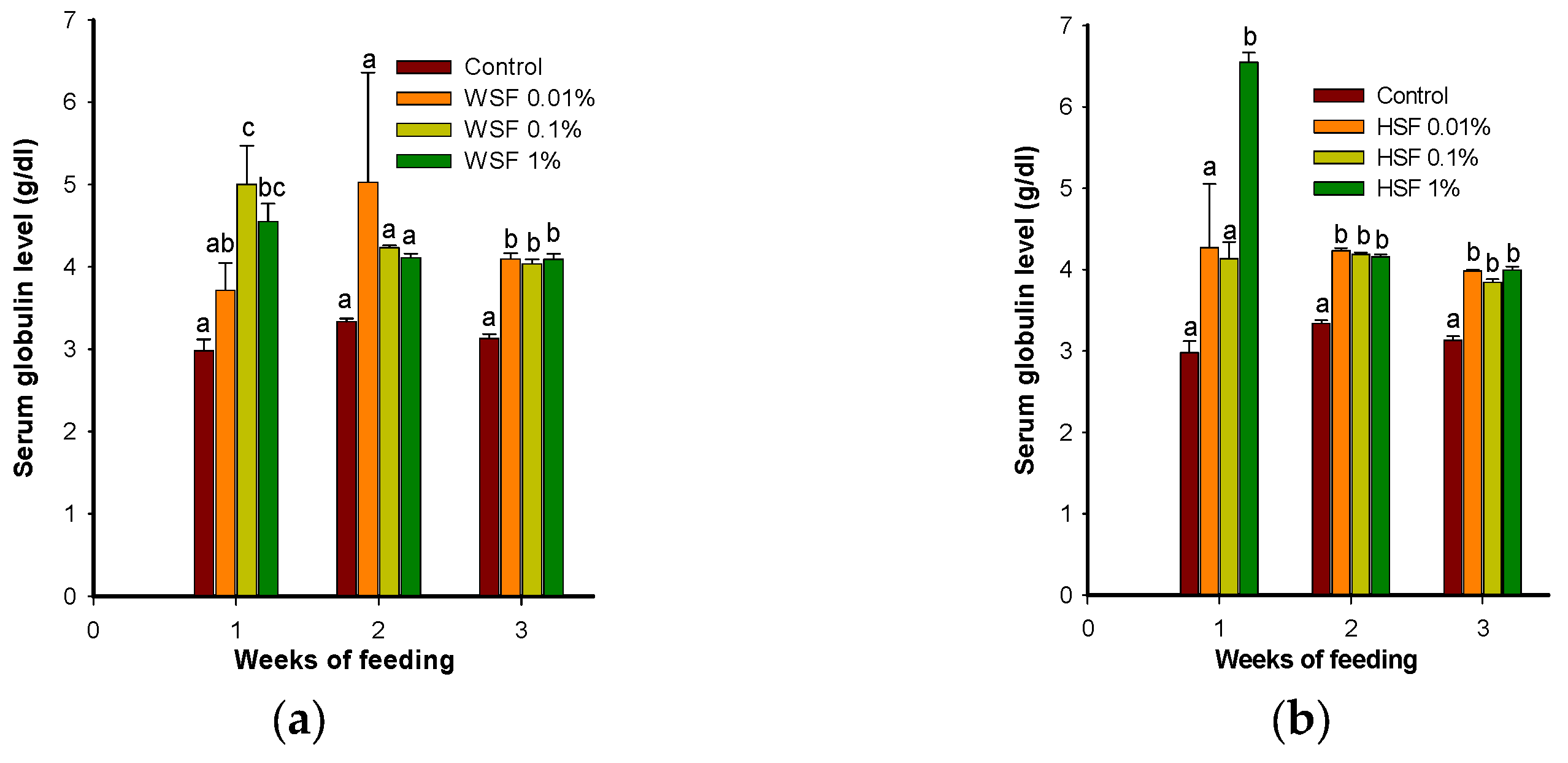

Feeding with 0.1% or 1% of the water-soluble fraction (WSF) significantly increased serum globulin levels after one week (P < 0.05;

Figure 1a). The group receiving 1% of the hexane-soluble fraction (HSF) for one week showed the highest globulin levels (

Figure 1b). All WSF doses elevated globulin only after three weeks, while all HSF doses caused an increase after two weeks, which persisted into the third week.

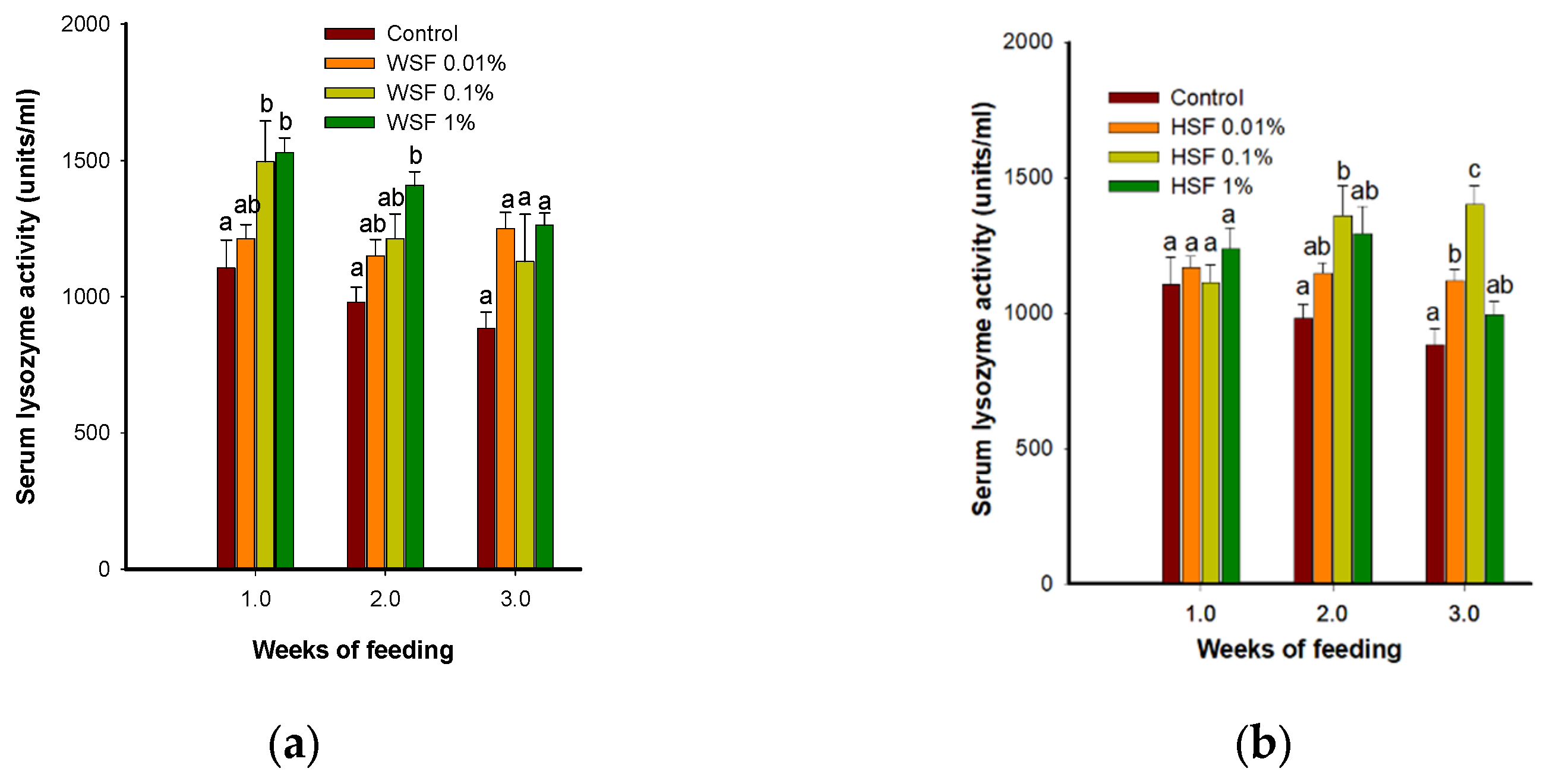

3.1.2. Lysozyme Activity

A significant enhancement in lysozyme activity was observed in fish fed with 1% WSF for one or two weeks (P < 0.05). Feeding with 0.1% WSF also raised lysozyme levels after one week (

Figure 2a). No change was seen in the group fed with 0.01% WSF.

In HSF-fed groups (

Figure 2b), 0.01% HSF led to a significant rise in lysozyme activity after three weeks, and 0.1% HSF induced an increase after two and three weeks. However, 1% HSF did not show any notable effect across all durations, and none of the HSF doses altered lysozyme activity after just one week.

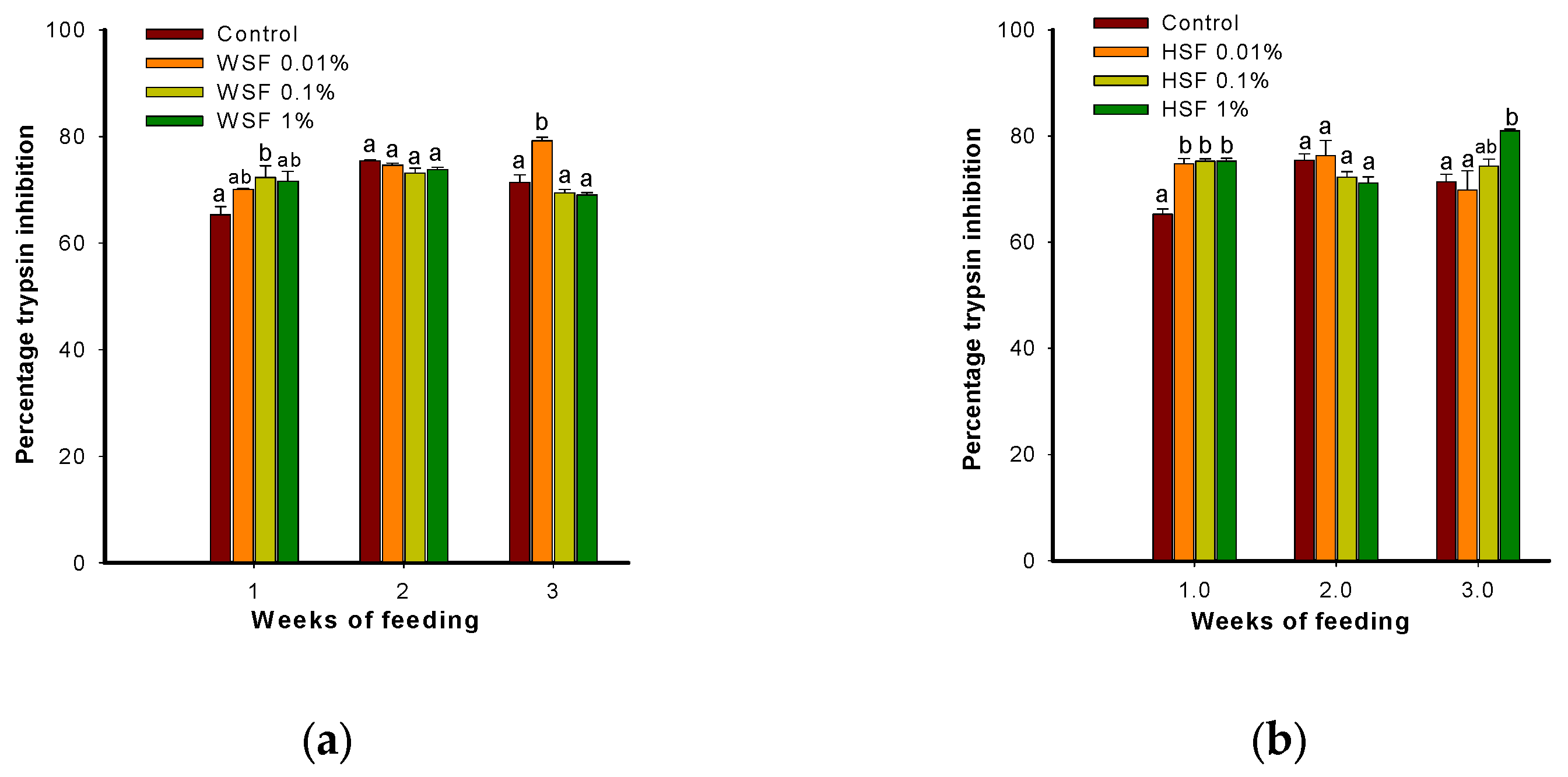

3.1.3. Antiprotease Activity

Supplementation with WSF for 1–3 weeks improved serum antiprotease activity in the 0.1% and 0.01% groups, notably after one and three weeks, respectively (P < 0.05;

Figure 3a). The 1% WSF did not significantly affect activity.

In contrast, all doses of HSF elevated antiprotease levels after one week of feeding (P < 0.05;

Figure 3b). However, this effect did not persist with extended feeding durations and was comparable to control values after two or three weeks.

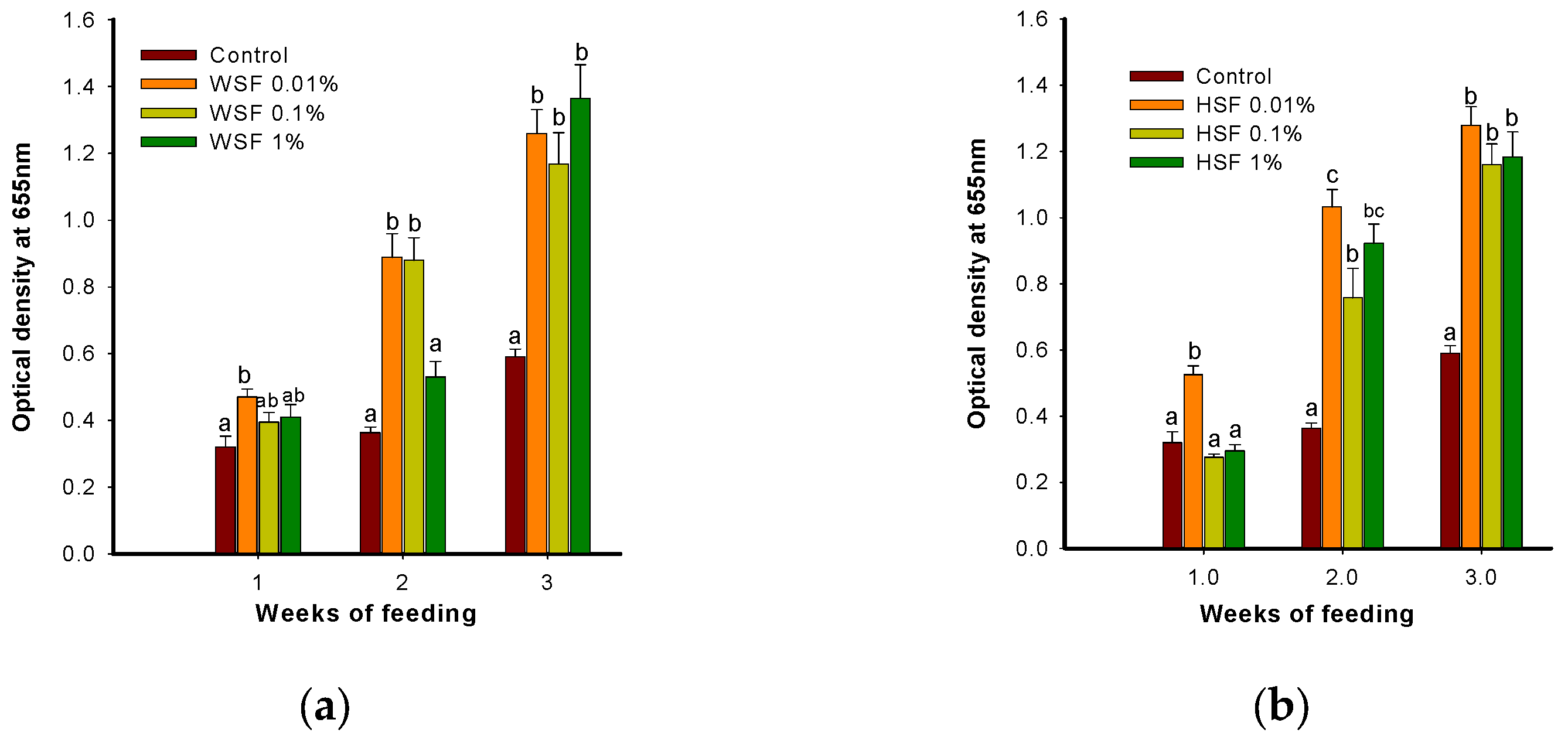

3.1.4. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Production in PBL

As shown in

Figure 4a, 0.01% WSF significantly increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production after one, two, and three weeks of feeding (P < 0.05), with levels rising progressively over time. A similar increase was observed after two and three weeks in the 0.1% WSF group, while 1% WSF induced a significant effect only after three weeks.

For HSF-fed fish (

Figure 4b), 0.01% supplementation significantly enhanced ROS levels at all three time points (P < 0.05). The 0.1% and 1% HSF doses showed increased activity only after two or three weeks of feeding.

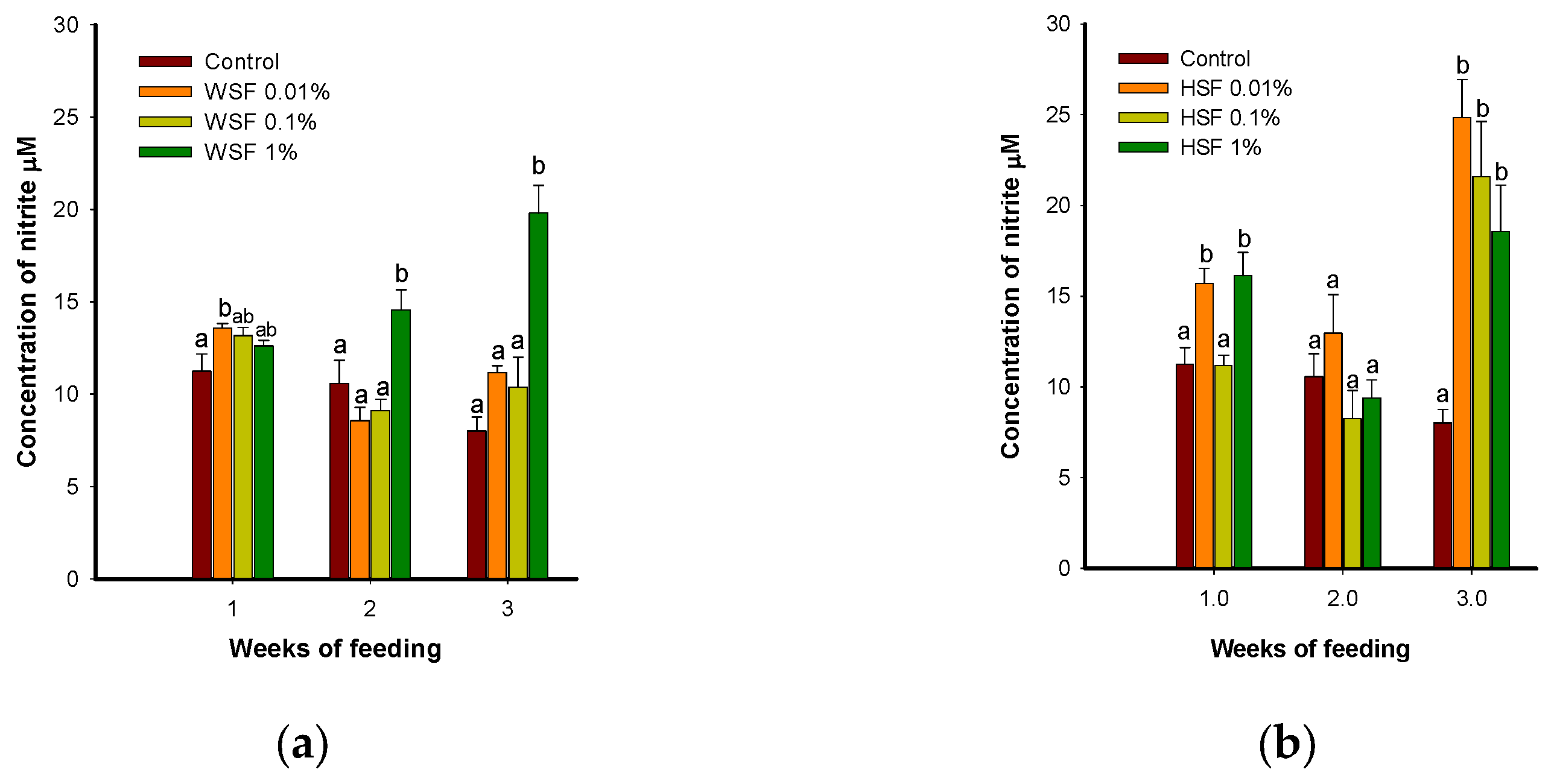

3.1.5. Reactive Nitrogen Intermediate (RNI) Production in PBL

Dietary WSF at 0.01%, significantly boosted reactive nitrogen intermediate (RNI) production after one week (P < 0.05;

Figure 5a). The 1% WSF group showed elevated RNI levels after two and three weeks, with the peak observed at week three.

In HSF-treated groups (

Figure 5b), all doses significantly increased RNI production after three weeks (P < 0.05). Additionally, 0.01% and 1% HSF also enhanced RNI levels after just one week.

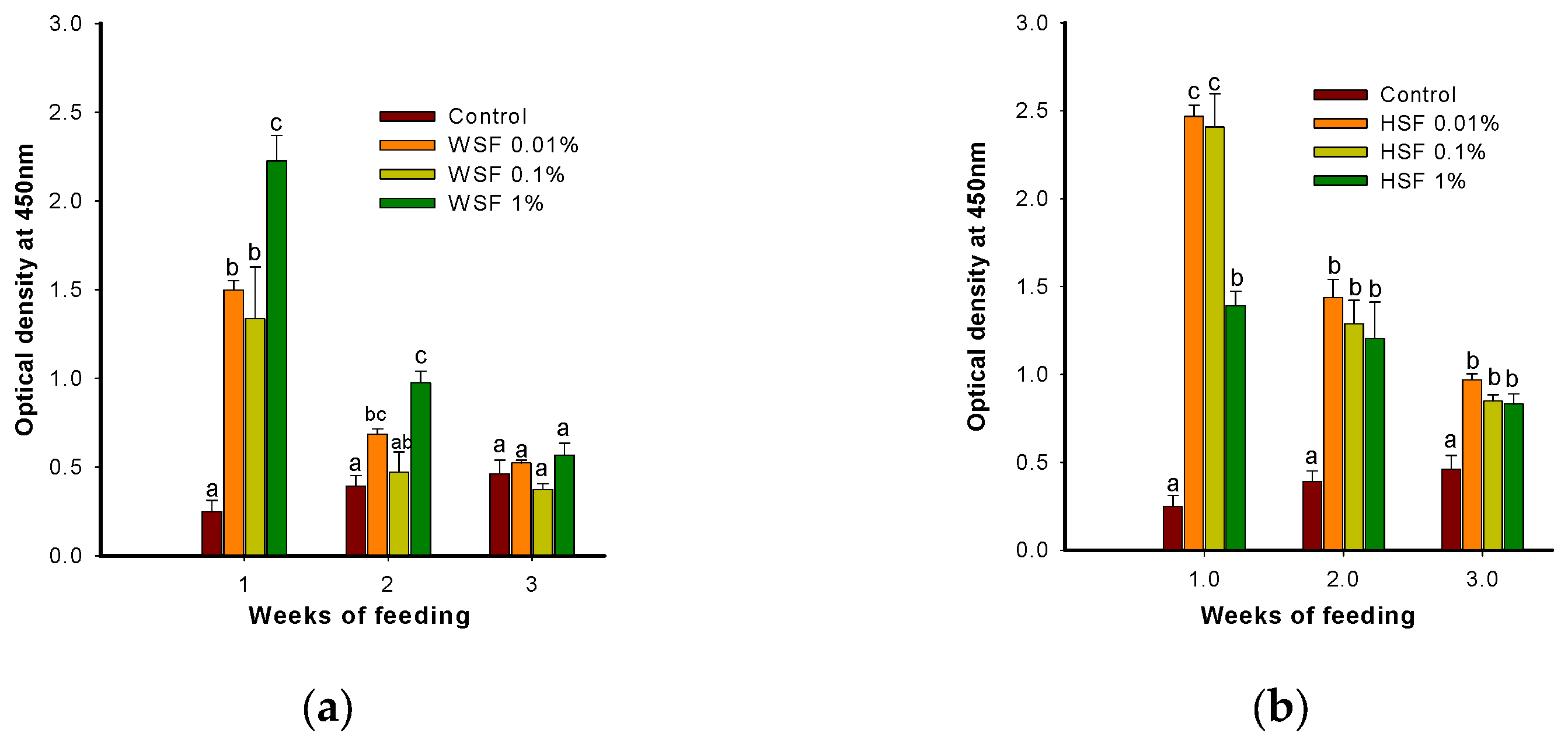

3.1.6. MPO Activity in PBL

The 0.01% and 1% WSF groups showed increased myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity after two weeks of feeding (

Figure 6a), with the highest level recorded in the 1% group after one week. However, WSF did not significantly modulate MPO levels after three weeks.

HSF supplementation, on the other hand, resulted in a sustained increase in MPO activity after both two and three weeks of feeding (

Figure 6b).

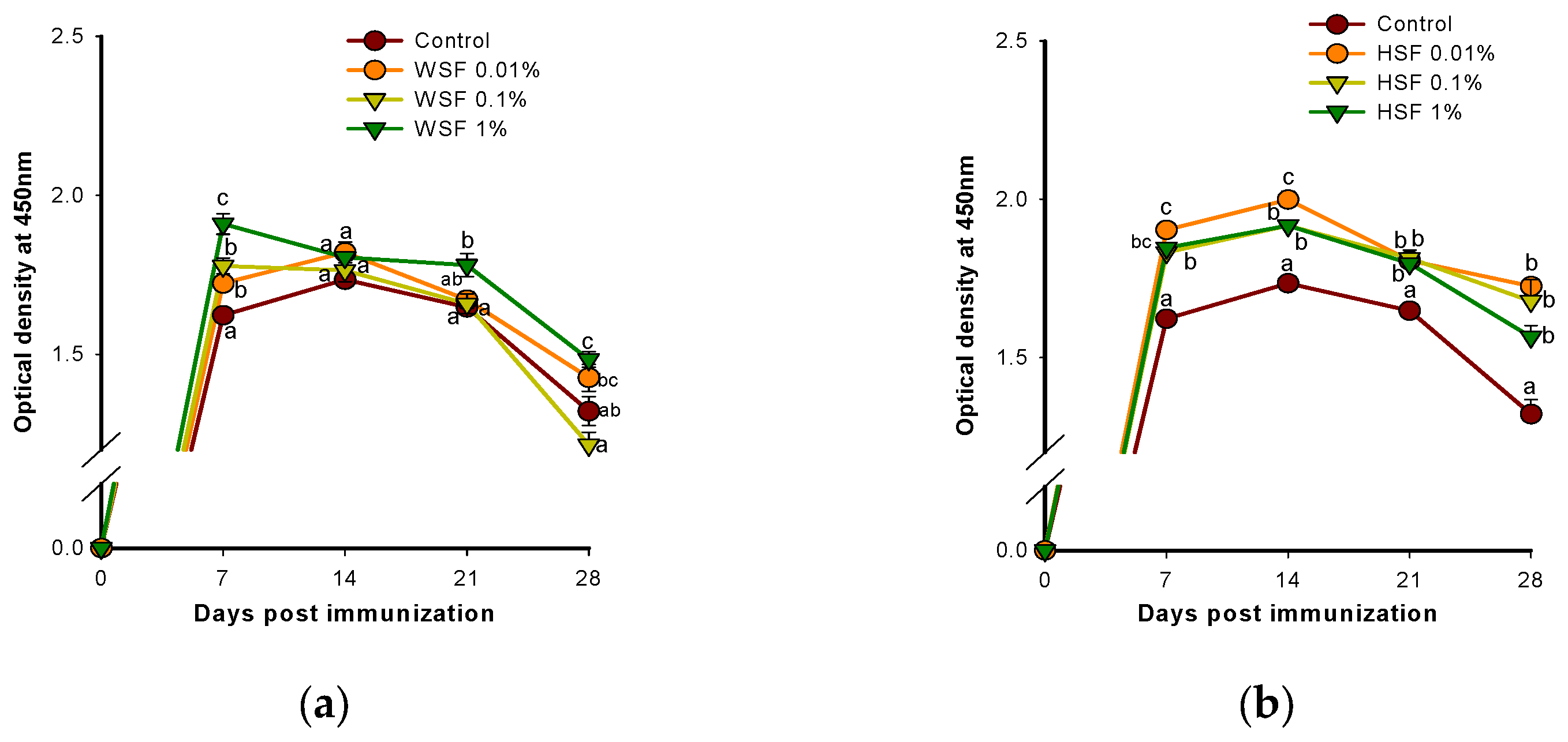

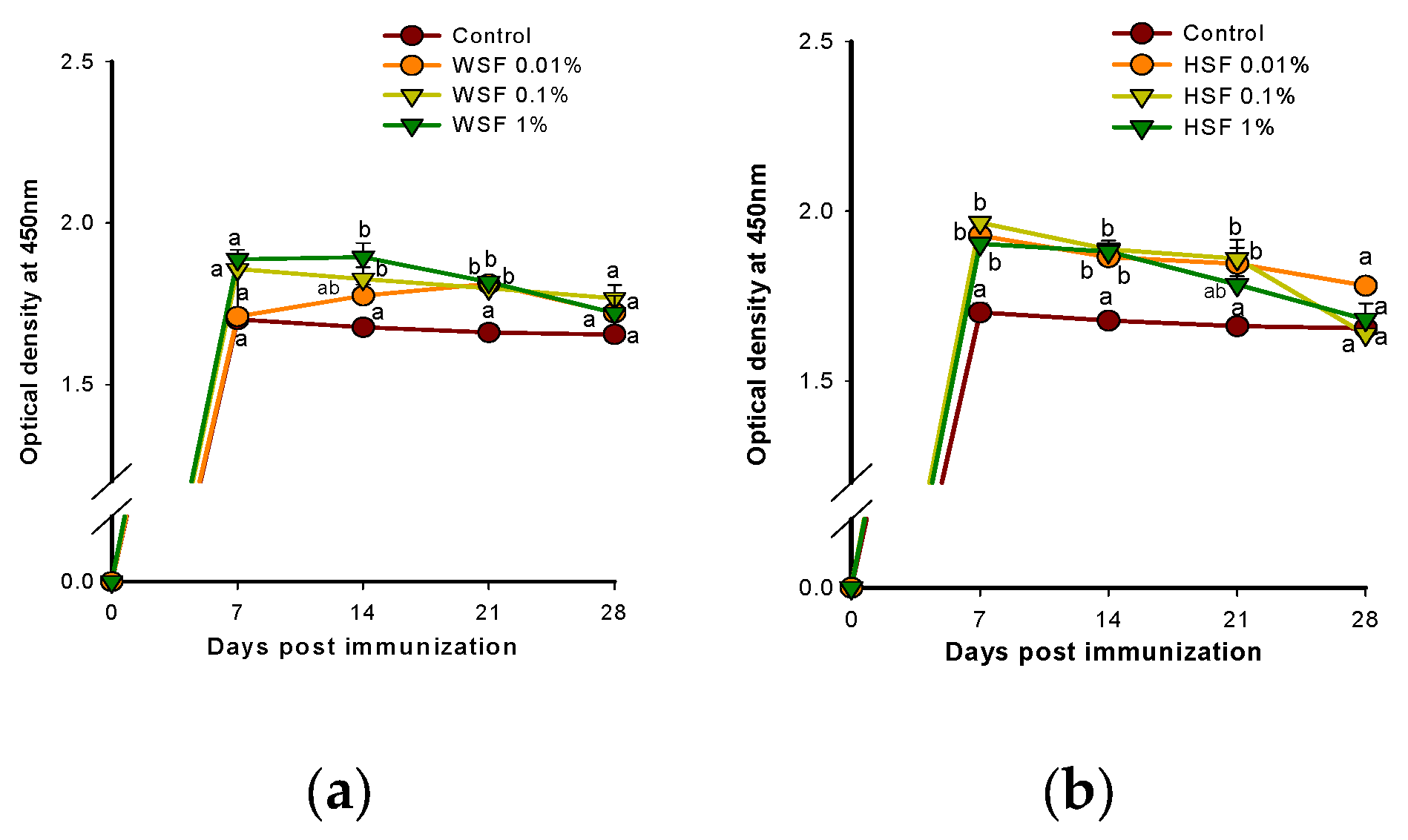

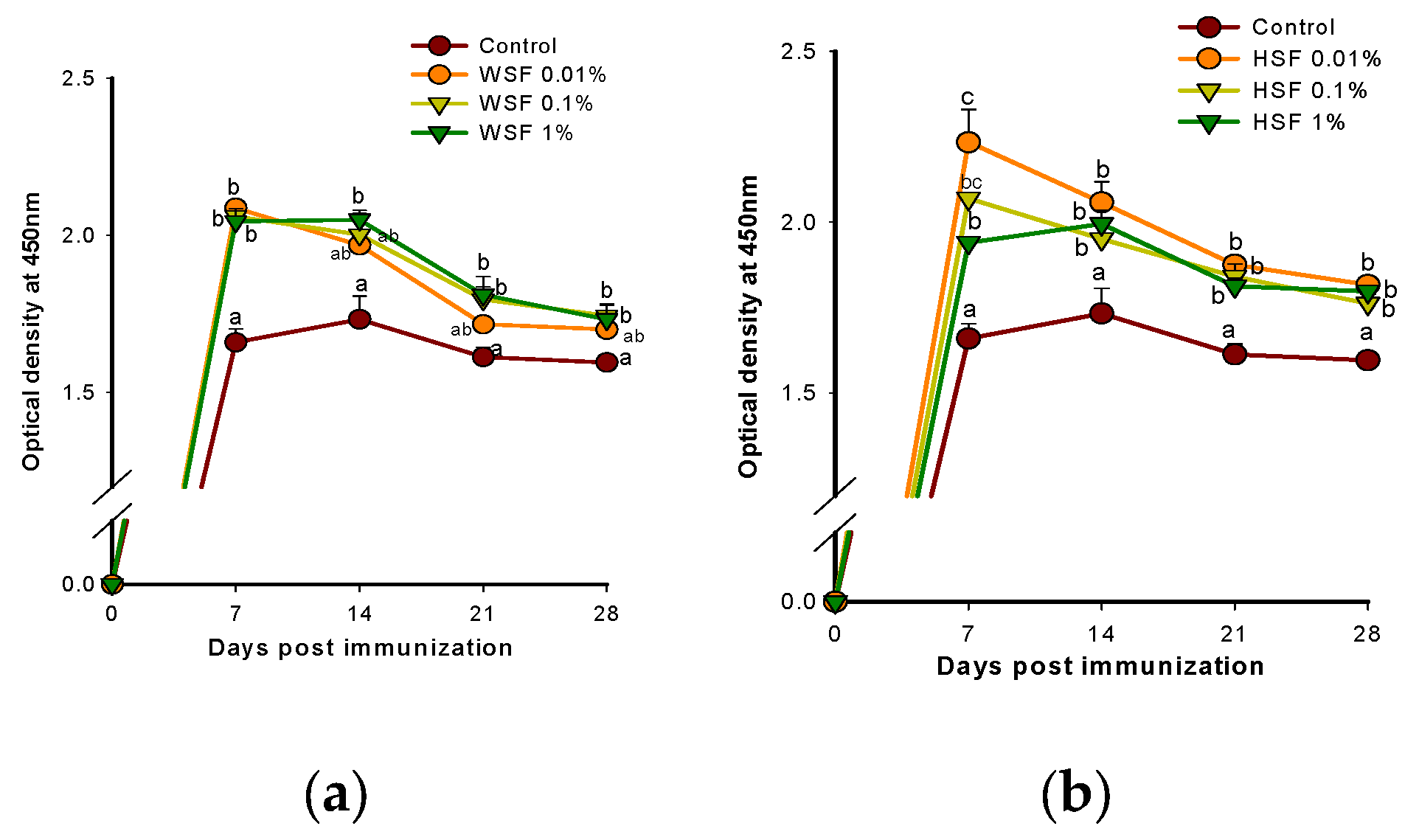

3.2. Specific Immune Response

In WSF-fed fish, antibody titres increased significantly on day 7 across all treatment groups after one week of feeding (P < 0.05;

Figure 7a). In the 1% WSF group, this response remained elevated into the third and fourth weeks. HSF-treated groups also showed a consistent antibody increase after one week (

Figure 7b).

After two weeks, the 1% and 0.1% WSF diets enhanced antibody levels on days 14 and 21 (P < 0.05;

Figure 8a). In HSF-fed fish, 0.01% and 0.1% doses significantly boosted antibody responses on most days, while the 1% group showed increases on days 7 and 14 (

Figure 8b). With three weeks of feeding, 1% WSF significantly elevated antibody titres across all time points (

Figure 9a). The 0.1% WSF group showed increased response on days 7 and 21, while 0.01% WSF did not produce any change. All HSF dose groups demonstrated significant antibody enhancement on nearly all tested days (

Figure 9b).

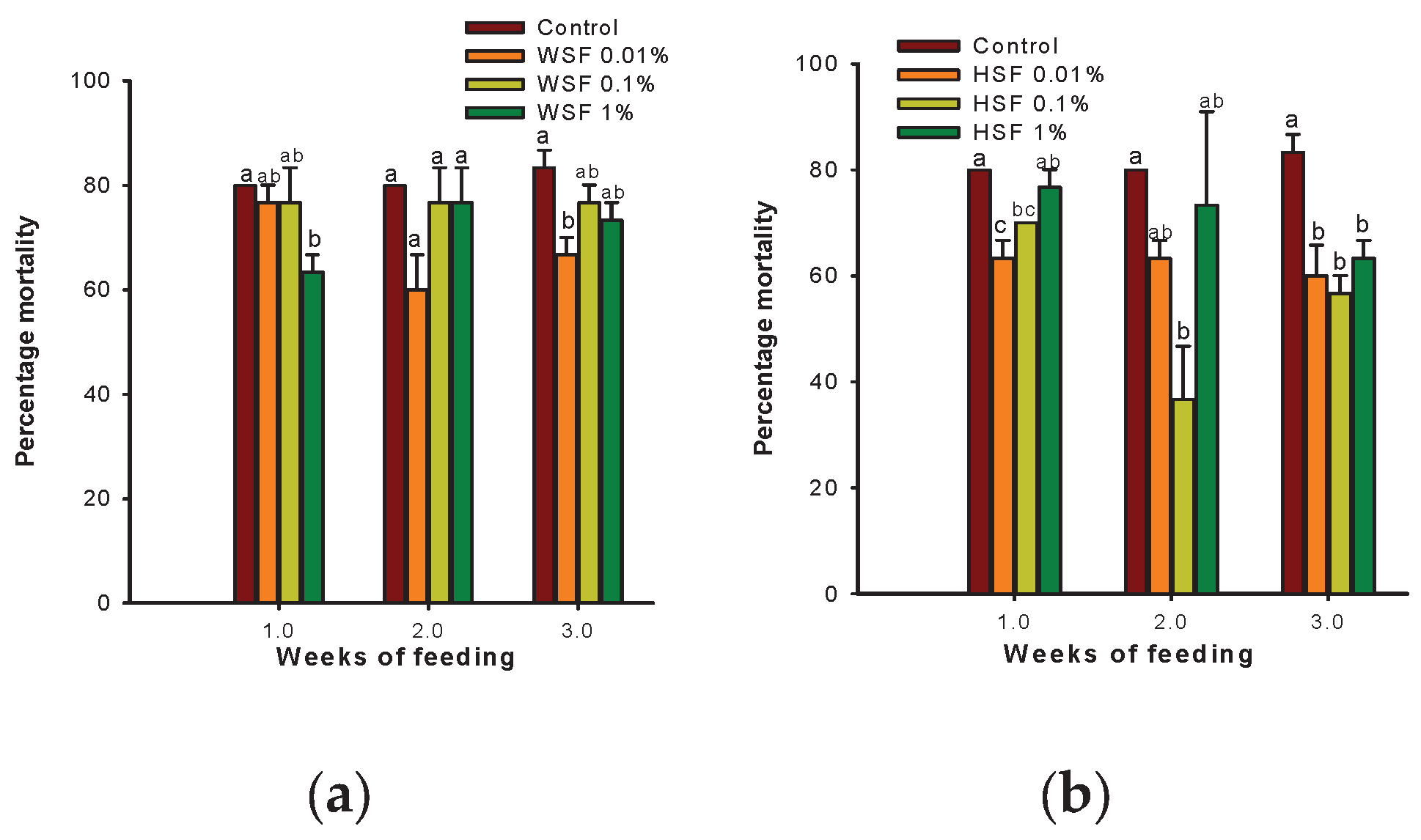

3.3. Disease Resistance

Overall, feeding with

S. trilobatum leaf extracts reduced fish mortality after bacterial challenge. In the WSF-fed groups, a significant reduction in mortality was seen only in the 1% group after one week (63.33%, RPS = 20.83) and the 0.01% group after three weeks (66.67%, RPS = 20) (

Figure 10a;

Table 1).

Three weeks of feeding with any HSF dose significantly reduced mortality (P < 0.05;

Figure 10b;

Table 1). Notably, the 0.01% and 0.1% HSF doses lowered mortality after just one week (RPS = 20.83 and 12.5, respectively). The 0.1% dose continued to offer protection after two weeks (36.67%, RPS = 54.17).

3.4. GC-MS Analysis

GC-MS profiling revealed 31 compounds in WSF and 44 in HSF. In the WSF, γ-sitosterol (RT: 27.424) had the largest peak area (1,959,571) and was identified as a major phytosterol. Other components included alkanes, fatty alcohols, quinones, diterpenes, triterpenes, and sesquiterpenoids (

Table 2).

In HSF, the dominant compound was germacrene D-4-ol (RT: 11.962) with a peak area of 6,051,885, followed by abietinol.

Table 3 lists additional constituents including diterpenes, fatty acids, esters, steroids, and other phytosterols.

3.5. In Silico Evaluation of Bioavailability of the Phytoconstituents

Based on Lipinski’s Rule of Five, one compound from the WSF and eleven from the HSF were predicted to have good oral bioavailability. The total relative abundance (sum of peak area percentages) for these compounds was 41.11% in WSF and 47.66% in HSF. Most violations of Lipinski’s criteria were associated with high miLogP values, suggesting limited solubility and absorption for those compounds.

4. Discussion

Medicinal plants are widely recognized for their ability to promote fish growth, stimulate appetite, and improve disease resistance by enhancing the immune system [

27]. They can also contribute to antioxidant defence mechanisms, as shown in several species [

28]. A recent meta-analysis by Mbokane and Moyo, [

29] supports the inclusion of medicinal plants in aquafeeds to strengthen disease resistance and improve overall fish health, which could have practical benefits for aquaculture operations. The current study reinforces these conclusions: enhanced immune responses were observed in

O. mossambicus following dietary inclusion of

S. trilobatum leaf extracts.

Serum globulin is a key biomarker of immune competence, elevated innate immune responses [

30] and general health in fish [

31]. In this study, oral administration of

S. trilobatum fractions resulted in a significant elevation of serum globulin levels. These results are in line with previous reports showing increased globulin in juvenile greasy groupers (

Epinephelus tauvina) when fed methanolic extracts of

Ocimum sanctum or

Withania somnifera [

32].

Lysozyme, vital component of the fish innate immunity, was significantly upregulated in

O. mossambicus receiving

S. trilobatum-supplemented diets. Similar trends have been documented in

O. niloticus fed with

Astragalus radix root at 0.1–0.5% for one week [

33], and in

Labeo rohita supplemented with

Achyranthes aspera extracts [

31] or

Allium sativum powder [

34]. The observed enhancement of lysozyme activity may reflect increased macrophage numbers [

35] or greater production of lysozyme per cell [

36], as macrophages are the primary producers of this enzyme.

Antiprotease activity, another humoral defence mechanism, was also increased after feeding with the HSF fraction. Such proteins help neutralize bacterial proteases, limiting infection [

37]. Comparable responses were observed in

Catla catla and

Oncorhynchus mykiss with dietary inclusion of

A. aspera [

38] or natural carotenoids in a study by Thompson

et al., [

39].

Enhanced ROS and RNI production in the treated groups suggest an activated oxidative burst response, a major defence mechanism of phagocytes [

40]. The stimulation may be linked to increased leukocyte activity, as seen in

Glycyrrhiza glabra [

41] or

Eclipta alba treated fish [

25] or due to the elevated phagocytic activity and cytokine [

42]. However, species-specific responses are evident; for example,

Zingiber officinale improved extracellular but not intracellular burst in trout [

43].

MPO, a marker for neutrophil activation, was upregulated following dietary treatment. Similar enhanced activity has been observed in

C. carpio,

Sparus aurata and

O. mykiss fed with oak leaf or yeast [

44,

45,

46]. The GC-MS results of

S. trilobatum indicated the presence of carbohydrate-rich components, potentially responsible for the immune [

25]activation observed, similar to β-glucan-based immunostimulants [

36].

Immunostimulants may also improve specific immune functions, especially when followed by infection or vaccination [

47]. Here, HSF-fed groups showed consistently higher antibody responses across multiple time points, while WSF also enhanced responses at select time points. This is consistent with earlier work involving

T. cordifolia [

48],

O. sanctum [

49] and Azadiractin [

50].

Upon challenge with

A. hydrophila, a significant reduction in mortality was observed in groups fed with both WSF and HSF, especially the latter. This agrees with earlier protective effects reported using

R. officinalis [

51] and

A. paniculata [

52]. Enhanced overall immunity has been reported upon dietary or IP administration of plant derived immunostimulants in

O. mossambicus [

53,

54],

L. rohita [

34] and

C. carpio [

55].

However, oral delivery offered slightly lower protection compared to intraperitoneal routes [

9], possibly due to inconsistent ingestion, compound degradation in the digestive tract, or limited absorption [

56].

The phytochemical composition of

S. trilobatum likely contributed to these results. Compounds such as sobatum (β-sitosterol) are known to modulate T-helper cell responses and cytokine production in mammalian systems [

57]. HSF, rich in di- and triterpenoids and saponins, showed superior bioactivity, where saponins are known to enhance cytokine production and lymphocyte proliferation [

58].

Bioavailability is key when delivering plant-based compounds via feed. In this study, HSF contained more bioavailable components, including Germacrene d-4-ol, a lipophilic sesquiterpenoid present in high concentration and compliant with Lipinski’s Rule of Five. Similar compounds like nerolidol have shown protective effects in infected

N. tilapia [

59]. Other compounds with poor solubility, indicated by high miLogP values, may have limited effectiveness due to poor absorption.

Taken together, both fractions of S. trilobatum stimulated disease resistance, specific immunity, humoral and cellular nonspecific responses. The HSF, in particular, showed higher efficacy and could be explored as a feed-based prophylactic immunostimulant in aquaculture systems.

5. Conclusions

Non-specific immune parameters, antibody response, and resistance to bacterial challenge in Oreochromis mossambicus were evaluated after the administration of either water-soluble fraction (WSF) or hexane-soluble fraction (HSF) of Solanum trilobatum leaves as feed supplement for 1, 2, or 3 weeks. Both the fractions increased serum globulin levels, lysozyme, antiprotease activity and in the peripheral blood leukocytes MPO content and ROS production also showed elevated response. The antibody response was significantly higher in the HSF-fed group, and this reflected on the reduced mortality in this group whereas WSF could reduce the mortality only after 1 or 3 weeks. We found better performance of HSF in stimulating immunity which might be due to the presence and bioavailability of aromatic compounds and phytosterols when compared to low molecular weight alcohols and carbonyls in WSF. These findings demonstrate that HSF enhances both innate and adaptive immunity in tilapia and can be explored for administration through feed to enhance the overall immunity of fish in aquaculture.

Ethics statement: The experimental work was conducted before the establishment of an Institutional Ethics Committee for non-mammalian models in India and prior to the formal release of CPCSEA guidelines for fish experimentation in 2021. At that time, procedures adhered to the Canadian Council on Animal Care (CCAC) standards for fish research, which were internationally recognized and ensured animal welfare.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.D.M., M.D.G., D.C. and S.S.; methodology, R.D.M., M.D.G., D.C. and S.S.; software, P.A.S., D.G. and S.S.; validation, R.D.M., D.G. and P.A.S.; formal analysis, D.G., D.C. and S.S.; investigation, D.G., D.C. and S.S.; resources, R.D.M.; data curation, D.G., D.C. and S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, D.G. and S.S.; writing—review and editing, D.G., S.S., S.T. and P.A.S.; visualization, D.G. and R.D.M.; supervision, R.D.M.; project administration, R.D.M.; funding acquisition, R.D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Department of Biotechnology, Government of India, New Delhi, (Ref No: BT/PR2385/AAQ/03/120/2001) and postdoctoral fellowship from the Humboldt Foundation.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available with corresponding author will be provided upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Premsingh, Department of Chemistry, The American College, Madurai, for his valuable guidance in preparing the plant extracts. We also acknowledge Advanced Instrumentation Research Facility (AIRF), JNU, New Delhi, for facilitating GC-MS analysis. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used ChatGPT [OpenAI, USA] for the purposes of language editing to refine grammar and improveclarity. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- FAO Blue Transformation - Roadmap 2022–2030: A Vision for FAO’s Work on Aquatic Food Systems; Rome, 2022.

- Robertsen, B. Modulation of the Non-Specific Defence of Fish by Structurally Conserved Microbial Polymers. Fish Shellfish Immunol 1999, 9, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raa, J.; Rorstad, G.; Engstad, R.; Robertsen, B. The Use of Immunostimulants to Increase Resistance of Aquatic Organisms to Microbial Infections. In Proceedings of the Diseases in Asian aquaculture; Shariff, I.M., Subasinghe, R.P., Arthus, J.R., Eds.; Asian Fisheries Society, 1992; pp. 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Subramani, P.A.S.; Priyadarshini Kalaivani; Balasubramanian Ramalakshmi; Divya Gnaneswari, M.; Ganesh Kumar Devasree; Rajendran Priyatharsini; Alexander Catherine; Michael, R. Dinakaran Current Status and Recent Advancements with Immunostimulants in Aquaculture. In Immunomodulators in Aquaculture and Fish Health; Elumalai, P., Soltani, M., Lakshmi, S., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2023 ISBN 9781003361183.

- Abareethan, M.; Sathiyapriya, R.; Pavithra, M.E.; Parvathy, S.; Thirumalaisamy, R.; Selvankumar, T.; Chinnathambi, A.; Almoallim, H.S. Biogenic Silver Nanoparticles from Solanum Trilobatum Leaf Extract and Assessing Their Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Potential. Chemical Physics Impact 2024, 9, 100771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandurangan, A.; Khosa, R.L.; Hemalatha, S. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of an Alkaloid from Solanum Trilobatum on Acute and Chronic Inflammation Models. Nat Prod Res 2011, 25, 1132–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sini, H.; Devi, K.S. Antioxidant Activities of the Chloroform Extract of Solanum Trilobatum. Pharm Biol 2004, 42, 462–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, S.; Viswanathan, S.; Vijayasekaran, V.; Alagappan, R. A Pilot Study on the Clinical Efficacy of Solanum Xanthocarpum and Solanum Trilobatum in Bronchial Asthma. J Ethnopharmacol 1999, 66, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divyagnaneswari, M.; Christybapita, D.; Michael, R.D. Enhancement of Nonspecific Immunity and Disease Resistance in Oreochromis Mossambicus by Solanum Trilobatum Leaf Fractions. Fish Shellfish Immunol 2007, 23, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parasuraman Aiya Subramani; Vinnie Cheeran; Ganesh Munuswamy Ramanujam; Venkata Ramireddy Narala Clinical Trials of Curcumin, Camptothecin, Astaxanthin and Biochanin. In Natural Products in clinical trials; Atta-ur-Rahman, Anjum Shazia, Hesham El-Seedi, Eds.; Bentham Science Publishers, UAE, 2018; Vol. I.

- Roskoski, R. Properties of FDA-Approved Small Molecule Protein Kinase Inhibitors. Pharmacol Res 2019, 144, 19–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R. Dinakaran Michael; Srinivas, S.D.; Sailendri, K.; Muthukkaruppan, V.R. A Rapid Method for Repetitive Bleeding in Fish. Indian Journal of Experimental Biology 1994, 32, 838–839. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry, O.H.; Rosebrough, N.J.; Farr, A.L.; Randall, R.J. Protein Measurement with the Folin Phenol Reagent. J Biol Chem 1951, 193, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doumas, B.T.; Ard Watson, W.; Biggs, H.G. Albumin Standards and the Measurement of Serum Albumin with Bromcresol Green. Clinica Chimica Acta 1971, 31, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, T.H.; Manning, M.J. Seasonal Trends in Serum Lysozyme Activity and Total Protein Concentration in Dab (Limanda Limanda L.) Sampled from Lyme Bay, U.K. Fish Shellfish Immunol 1996, 6, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, T.J.; Butler, R.; Bricknell, I.R.; Ellis, A.E. Serum Trypsin-Inhibitory Activity in Five Species of Farmed Fish. Fish Shellfish Immunol 1997, 7, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, X.; Woo, P.T.K. Natural Anti-Proteases in Rainbow Trout, Oncorhynchus Mykiss and Brook Charr, Salvelinus Fontinalis and the in Vitro Neutralization of Fish A2-Macroglobulin by the Metalloprotease from the Pathogenic Haemoflagellate, Cryptobia Salmositica. Parasitology 1997, 114, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secombes, C.J. Isolation of Salmonid Macrophages and Analysis of Their Killing Activity. In Techniques in fish Immunology; J.S. Stolen, T.C. Fletcher, D.P. Anderson, B.S. Robertson, W.B. van Muiswinkel, Eds.; SOS Publications: New Jersey., 1990; Vol. I, pp. 137–154.

- Green, L.C.; Wagner, D.A.; Glogowski, J.; Skipper, P.L.; Wishnok, J.S.; Tannenbaum, S.R. Analysis of Nitrate, Nitrite, and [15N] Nitrate in Biological Fluids. Anal Biochem 1982, 126, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palić, D.; Andreasen, C.B.; Menzel, B.W.; Roth, J.A. A Rapid, Direct Assay to Measure Degranulation of Primary Granules in Neutrophils from Kidney of Fathead Minnow (Pimephales Promelas Rafinesque, 1820). Fish Shellfish Immunol 2005, 19, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karunasagar, I.; Ali, A.; Otta, S.K.; Karunasagar, I. Immunization with Bacterial Antigens: Infections with Motile Aeromonads. Dev Biol Stand 1997, 90, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Binuramesh, C.; Prabakaran, M.; Steinhagen, D.; Michael, R.D. Effect of Sex Ratio on the Immune System of Oreochromis Mossambicus (Peters). Brain Behav Immun 2006, 20, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A.E. General Principles of Fish Vaccination. In Fish Vaccination; Academic Press: London, 1988; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R.K.; Bibi, S.; Chopra, H.; Khan, M.S.; Aggarwal, N.; Singh, I.; Ahmad, S.U.; Hasan, M.M.; Moustafa, M.; Al-Shehri, M.; et al. In Silico and In Vitro Screening Constituents of Eclipta Alba Leaf Extract to Reveal Antimicrobial Potential. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2022, 2022, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christybapita, D.; Divya Gnaneswari, M.; Sharma, S.; Michael, R.D.; Subramani, P.A. In Silico Insights into the Molecular Mechanisms of Eclipta Alba Leaf Fractions Enhancing Nonspecific Immune Mechanisms and Resistance to Aeromonas Hydrophila in Oreochromis Mossambicus (Peters). Aquac Rep 2025, 42, 102774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chen, J.; Cheng, T.; Gindulyte, A.; He, J.; He, S.; Li, Q.; Shoemaker, B.A.; Thiessen, P.A.; Yu, B.; et al. PubChem 2025 Update. Nucleic Acids Res 2025, 53, D1516–D1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faheem, M.; Hoseinifar, S.H.; Firouzbakhsh, F. Medicinal Plants in Tilapia Aquaculture. In; 2023; pp. 161–200.

- Zhang, X.; Sun, Z.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wang, G.; Cao, F. Enhancement of Growth, Antioxidative Status, Nonspecific Immunity, and Disease Resistance in Gibel Carp (Carassius Auratus) in Response to Dietary Flos Populi Extract. Fish Physiol Biochem 2022, 48, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbokane, E.M.; Moyo, N.A.G. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Potential Effect of Medicinal Plants on Innate Immunity of Selected Freshwater Fish Species: Its Implications for Fish Farming in Southern Africa. Aquaculture International 2024, 32, 315–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegertjes, G.F.; Stet, RenéJ.M.; Parmentier, H.K.; van Muiswinkel, W.B. Immunogenetics of Disease Resistance in Fish: A Comparative Approach. Dev Comp Immunol 1996, 20, 365–381. [CrossRef]

- Vasudeva Rao, Y.; Das, B.K.; Jyotyrmayee, P.; Chakrabarti, R. Effect of Achyranthes Aspera on the Immunity and Survival of Labeo Rohita Infected with Aeromonas Hydrophila. Fish Shellfish Immunol 2006, 20, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaram, V.; Babu, M.M.; Immanuel, G.; Murugadass, S.; Citarasu, T.; Marian, M.P. Growth and Immune Response of Juvenile Greasy Groupers (Epinephelus Tauvina) Fed with Herbal Antibacterial Active Principle Supplemented Diets against Vibrio Harveyi Infections. Aquaculture 2004, 237, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.; Jeney, G.; Racz, T.; Xu, P.; Jun, X.; Jeney, Z. Effect of Two Chinese Herbs (Astragalus Radix and Scutellaria Radix) on Non-Specific Immune Response of Tilapia, Oreochromis Niloticus. Aquaculture 2006, 253, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, S.; Das, B.K.; Mishra, B.K.; Pradhan, J.; Sarangi, N. Effect of Allium Sativum on the Immunity and Survival of Labeo Rohita Infected with Aeromonas Hydrophila. Journal of Applied Ichthyology 2007, 23, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarder, M.R.I.; Thompson, K.D.; Penman, D.J.; McAndrew, B.J. Immune Responses of Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis Niloticus L.) Clones: I. Non-Specific Responses. Dev Comp Immunol 2001, 25, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engstad, R.E.; Robertsen, B.; Frivold, E. Yeast Glucan Induces Increase in Lysozyme and Complement-Mediated Haemolytic Activity in Atlantic Salmon Blood. Fish Shellfish Immunol 1992, 2, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A.E. Innate Host Defense Mechanisms of Fish against Viruses and Bacteria. Dev Comp Immunol 2001, 25, 827–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.V.; Chakrabarti, R. Stimulation of Immunity in Indian Major Carp Catla Catla with Herbal Feed Ingredients. Fish Shellfish Immunol 2005, 18, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, I.; Choubert, G.; Houlihan, D.F.; Secombes, C.J. The Effect of Dietary Vitamin A and Astaxanthin on the Immunocompetence of Rainbow Trout. Aquaculture 1995, 133, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, G.; Evelyn, T.P.T.; Lallier, R. Immunity to Aeromonas Salmonicida in Coho Salmon (Oncorhynchus Kisutch) Induced by Modified Freund’s Complete Adjuvant: Its Non-Specific Nature and the Probable Role of Macrophages in the Phenomenon. Dev Comp Immunol 1985, 9, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.I.; Marsden, M.J.; Kim, Y.G.; Choi, M.S.; Secombes, C.J. The Effect of Glycyrrhizin on Rainbow Trout, Oncorhynchus Mykiss (Walbaum), Leucocyte Responses. J Fish Dis 1995, 18, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peddie, S.; Zou, J.; Secombes, C.J. Immunostimulation in the Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus Mykiss) Following Intraperitoneal Administration of Ergosan. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2002, 86, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dügenci, S.K.; Arda, N.; Candan, A. Some Medicinal Plants as Immunostimulant for Fish. J Ethnopharmacol 2003, 88, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paray, B.A.; Hoseini, S.M.; Hoseinifar, S.H.; Van Doan, H. Effects of Dietary Oak (Quercus Castaneifolia) Leaf Extract on Growth, Antioxidant, and Immune Characteristics and Responses to Crowding Stress in Common Carp (Cyprinus Carpio). Aquaculture 2020, 524, 735276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwicki, A.K.; Anderson, D.P.; Rumsey, G.L. Dietary Intake of Immunostimulants by Rainbow Trout Affects Non-Specific Immunity and Protection against Furunculosis. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 1994, 41, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortuño, J.; Cuesta, A.; Rodrı́guez, A.; Esteban, M.A.; Meseguer, J. Oral Administration of Yeast, Saccharomyces Cerevisiae, Enhances the Cellular Innate Immune Response of Gilthead Seabream (Sparus Aurata L.). Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2002, 85, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, D.P. Immunostimulants, Adjuvants, and Vaccine Carriers in Fish: Applications to Aquaculture. Annu Rev Fish Dis 1992, 2, 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhakaran, D.S.; Srirekha, P.; Devasree, L.D.; Premsingh, S.; Michael, R.D. Immunostimulatory Effect of Tinospora Cordifolia Miers Leaf Extract in Oreochromis Mossambicus. Indian J Exp Biol 2006, 44, 726–732. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatalakshmi, S.; Michael, R.D. Immunostimulation by Leaf Extract of Ocimum Sanctum Linn. in Oreochromis Mossambicus (Peters). Journal of Aquaculture in the Tropics 2001, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Logambal, S.M.; Michael, R.D. Azadirachtin - an Immunostimulant for Oreochromis Mossambicus (Peters). Journal of Aquaculture in the Tropics 2001, 16, 339–347. [Google Scholar]

- Abutbul, S.; Golan-Goldhirsh, A.; Barazani, O.; Zilberg, D. Use of Rosmarinus Officinalis as a Treatment against Streptococcus Iniae in Tilapia (Oreochromis Sp.). Aquaculture 2004, 238, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citarasu, T.; Venkatramalingam, K.; Micheal Babu, M.; Raja Jeya Sekar, R.; Petermarian, M. Influence of the Antibacterial Herbs, Solanum Trilobatum, Andrographis Paniculata and Psoralea Corylifolia on the Survival, Growth and Bacterial Load of Penaeus Monodon Post Larvae. Aquaculture International 2003, 11, 581–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devasree, L.D.; Binuramesh, C.; Michael, R.D. Immunostimulatory Effect of Water Soluble Fraction of Nyctanthes Arbortristis Leaves on the Immune Response in Oreochromis Mossambicus (Peters). Aquac Res 2014, 45, 1581–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, C.P.; John Wesly Kirubakaran, C.; Michael, R.D. Water Soluble Fraction of Tinospora Cordifolia Leaves Enhanced the Non-Specific Immune Mechanisms and Disease Resistance in Oreochromis Mossambicus. Fish Shellfish Immunol 2010, 29, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harikrishnan, R.; Balasundaram, C.; Bhuvaneswari, R. Restorative Effect of Azadirachta Indica Aqueous Leaf Extract Dip Treatment on Haematological Parameter Changes in Cyprinus Carpio (L.) Experimentally Infected with Aphanomyces Invadans Fungus. Journal of Applied Ichthyology 2005, 21, 410–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Companjen, A.R.; Florack, D.E.A.; Slootweg, T.; Borst, J.W.; Rombout, J.H.W.M. Improved Uptake of Plant-Derived LTB-Linked Proteins in Carp Gut and Induction of Specific Humoral Immune Responses upon Infeed Delivery. Fish Shellfish Immunol 2006, 21, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouic, P.J.D. The Role of Phytosterols and Phytosterolins in Immune Modulation: A Review of the Past 10 Years. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2001, 4, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacaille-Dubois, M.-A.; Hanquet, B.; Cui, Z.-H.; Lou, Z.-C.; Wagner, H. A New Biologically Active Acylated Triterpene Saponin from Silene f Ortunei. J Nat Prod 1999, 62, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldissera, M.D.; Souza, C.F.; Velho, M.C.; Bassotto, V.A.; Ourique, A.F.; Da Silva, A.S.; Baldisserotto, B. Nanospheres as a Technological Alternative to Suppress Hepatic Cellular Damage and Impaired Bioenergetics Caused by Nerolidol in Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis Niloticus). Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2020, 393, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Modulation of serum globulin level in fish fed with WSF (a) or HSF (b) of S. trilobatum leaves supplemented diet for 1, 2 and 3 weeks; each point represents mean ± SE of 6 fish; Error bars with different alphabets indicates significant difference (P<0.05).

Figure 1.

Modulation of serum globulin level in fish fed with WSF (a) or HSF (b) of S. trilobatum leaves supplemented diet for 1, 2 and 3 weeks; each point represents mean ± SE of 6 fish; Error bars with different alphabets indicates significant difference (P<0.05).

Figure 2.

Modulation of serum lysozyme activity in fish fed with WSF (a) or HSF (b) of S. trilobatum leaves supplemented diet for 1, 2 and 3 weeks; each point represents mean ± SE of 6 fish; Error bars with different alphabets indicates significant difference (P<0.05).

Figure 2.

Modulation of serum lysozyme activity in fish fed with WSF (a) or HSF (b) of S. trilobatum leaves supplemented diet for 1, 2 and 3 weeks; each point represents mean ± SE of 6 fish; Error bars with different alphabets indicates significant difference (P<0.05).

Figure 3.

Modulation of serum antiprotease activity in fish fed with WSF (a) or HSF (b) of S. trilobatum leaves supplemented diet for 1, 2 and 3 weeks; each point represents mean ± SE of 6 fish; Error bars with different alphabets indicates significant difference (P<0.05).

Figure 3.

Modulation of serum antiprotease activity in fish fed with WSF (a) or HSF (b) of S. trilobatum leaves supplemented diet for 1, 2 and 3 weeks; each point represents mean ± SE of 6 fish; Error bars with different alphabets indicates significant difference (P<0.05).

Figure 4.

Modulation of ROS production in fish fed with WSF (a) or HSF (b) of S. trilobatum leaves supplemented diet for 1, 2 and 3 weeks; each point represents mean ± SE of 6 fish; Error bars with different alphabets indicates significant difference (P<0.05).

Figure 4.

Modulation of ROS production in fish fed with WSF (a) or HSF (b) of S. trilobatum leaves supplemented diet for 1, 2 and 3 weeks; each point represents mean ± SE of 6 fish; Error bars with different alphabets indicates significant difference (P<0.05).

Figure 5.

Modulation of RNI production in fish fed with WSF (a) or HSF (b) of S. trilobatum leaves supplemented diet for 1, 2 and 3 weeks; each point represents mean ± SE of 6 fish; Error bars with different alphabets indicates significant difference (P<0.05).

Figure 5.

Modulation of RNI production in fish fed with WSF (a) or HSF (b) of S. trilobatum leaves supplemented diet for 1, 2 and 3 weeks; each point represents mean ± SE of 6 fish; Error bars with different alphabets indicates significant difference (P<0.05).

Figure 6.

Modulation of MPO content in fish fed with WSF (a) or HSF (b) of S. trilobatum leaves supplemented diet for 1, 2 and 3 weeks; each point represents mean ± SE of 6 fish; Error bars with different alphabets indicates significant difference (P<0.05).

Figure 6.

Modulation of MPO content in fish fed with WSF (a) or HSF (b) of S. trilobatum leaves supplemented diet for 1, 2 and 3 weeks; each point represents mean ± SE of 6 fish; Error bars with different alphabets indicates significant difference (P<0.05).

Figure 7.

Modulation of antibody response to heat killed A. hydrophila tested by ELISA in fish fed with WSF (a) or HSF (b) of S. trilobatum leaves supplemented diet for 1 week; each point represents mean ± SE of 6 fish; Error bars with different alphabets indicates significant difference (P<0.05).

Figure 7.

Modulation of antibody response to heat killed A. hydrophila tested by ELISA in fish fed with WSF (a) or HSF (b) of S. trilobatum leaves supplemented diet for 1 week; each point represents mean ± SE of 6 fish; Error bars with different alphabets indicates significant difference (P<0.05).

Figure 8.

Modulation of antibody response to heat killed A. hydrophila tested by ELISA in fish fed with WSF (a) or HSF (b) of S. trilobatum leaves supplemented diet for 2 weeks; each point represents mean ± SE of 6 fish; Error bars with different alphabets indicates significant difference (P<0.05).

Figure 8.

Modulation of antibody response to heat killed A. hydrophila tested by ELISA in fish fed with WSF (a) or HSF (b) of S. trilobatum leaves supplemented diet for 2 weeks; each point represents mean ± SE of 6 fish; Error bars with different alphabets indicates significant difference (P<0.05).

Figure 9.

Modulation of antibody response to heat killed A. hydrophila tested by ELISA in fish fed with WSF (a) or HSF (b) of S. trilobatum leaves supplemented diet for 3 weeks; each point represents mean ± SE of 6 fish; Error bars with different alphabets indicates significant difference (P<0.05).

Figure 9.

Modulation of antibody response to heat killed A. hydrophila tested by ELISA in fish fed with WSF (a) or HSF (b) of S. trilobatum leaves supplemented diet for 3 weeks; each point represents mean ± SE of 6 fish; Error bars with different alphabets indicates significant difference (P<0.05).

Figure 10.

Modulation of disease resistance in fish fed with WSF (a) or HSF (b) of S. trilobatum leaves supplemented diet for 1, 2 and 3 weeks; each point represents mean ± SE of 10 fish in triplicate; Error bars with different alphabets indicates significant difference (P<0.05).

Figure 10.

Modulation of disease resistance in fish fed with WSF (a) or HSF (b) of S. trilobatum leaves supplemented diet for 1, 2 and 3 weeks; each point represents mean ± SE of 10 fish in triplicate; Error bars with different alphabets indicates significant difference (P<0.05).

Table 1.

Change in relative percent survival (RPS) in fish fed with WSF or HSF of S. trilobatum leaves supplemented diet for 1, 2 and 3 weeks.

Table 1.

Change in relative percent survival (RPS) in fish fed with WSF or HSF of S. trilobatum leaves supplemented diet for 1, 2 and 3 weeks.

| Fractions |

Dose |

1 week |

2 weeks |

3 weeks |

| WSF |

0.01% |

4.17 |

25.00 |

20.00 |

| 0.1% |

4.17 |

4.17 |

8.00 |

| 1% |

20.83 |

4.17 |

12.00 |

| HSF |

0.01% |

20.83 |

20.83 |

28.00 |

| 0.1% |

12.50 |

54.17 |

32.00 |

| 1% |

4.17 |

8.33 |

24.00 |

Table 2.

Phytoconstituents in S. trilobatum WSF based on GC-MS analysis and the number of Lipinski’s violations.

Table 2.

Phytoconstituents in S. trilobatum WSF based on GC-MS analysis and the number of Lipinski’s violations.

| Chemical Class |

Retention Time |

Area |

Area % |

Compound Name |

Molecular Formula |

Molecular Weight, g/mol |

N Violations |

| Alcohol |

22.207 |

103451 |

0.59 |

1,3-Propanediol, dodecyl ethyl ether |

C17H36O2

|

272 |

1 |

| Alkanes |

12.338 |

703424 |

4.05 |

Nonane, 3-methyl-5-propyl- |

C13H28

|

184 |

1 |

| 19.053 |

188710 |

1.09 |

2-methylhexacosane |

C27H56

|

380 |

1 |

| 14.097 |

118161 |

0.68 |

Heptadecane, 3-methyl- |

C18H38

|

254 |

1 |

| Alkylbenzene |

15.765 |

636438 |

3.66 |

Benzenepropanoic acid, 3,5-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-4-hydro |

C18H28O3

|

292 |

1 |

| Benzenoids |

7.449 |

6997607 |

40.24 |

Azulene |

C10H8

|

128 |

0 |

| Carbohydrate |

18.189 |

48125 |

0.28 |

Carbonic acid, eicosyl vinyl ester |

C23H44O3

|

368 |

1 |

| Diterpene |

17.473 |

273775 |

1.57 |

Phytol |

C20H40O |

296 |

1 |

| 14.793 |

127124 |

0.73 |

Neophytadiene |

C20H38

|

278 |

1 |

| 18.342 |

66102 |

0.38 |

Phytol, acetate |

C22H42O2

|

338 |

1 |

| Ergostane steroids |

26.509 |

684277 |

3.94 |

Ergost-5-en-3-ol, (3.β.,24r)- |

C28H48O |

400 |

1 |

| Fatty acid methyl ester |

22.462 |

181667 |

1.04 |

Tricosanoic acid, methyl ester |

C24H48O2

|

368 |

1 |

| Fatty Alcohol |

20.733 |

180506 |

1.04 |

1-hexacosanol |

C26H54O |

382 |

1 |

| 17.3 |

161875 |

0.93 |

6,11-hexadecadien-1-ol |

C16H30O |

238 |

1 |

| Fattyacids esters |

17.349 |

155442 |

0.89 |

Methyl Stearate |

C19H36O2

|

296 |

1 |

| 17.574 |

67628 |

0.39 |

Octadecanoic acid, methyl ester |

C19H38O2

|

298 |

1 |

| Hydrocarbon |

10.196 |

1247832 |

7.18 |

1-chlorohexadecane |

C16H33Cl |

260 |

1 |

| Long chain fatty alcohol |

30.253 |

162922 |

0.94 |

1,2-nonadecanediol |

C19H40O2

|

300 |

1 |

| Macrocyclin diterpene alcohol |

29.191 |

196398 |

1.13 |

Thunbergol |

C20H34O |

290 |

1 |

| Pentracyclic triterpenoid |

28.395 |

429331 |

2.47 |

9,19-Cyclolanost-24-en-3-ol, (3.β.)- |

C30H50O |

426 |

1 |

| Phytosterol |

27.424 |

1959571 |

11.27 |

γ-sitosterol |

C29H50O |

414 |

1 |

| 26.749 |

1210014 |

6.96 |

Stigmasta-5,23-dien-3-ol, (3.β.)- |

C29H48O |

412 |

1 |

| 25.533 |

156360 |

0.9 |

Cholest-5-en-3-ol (3.β)- |

C27H46O |

386 |

1 |

| Quinone and hydroquinone lipids |

25.436 |

151482 |

0.87 |

Vitamin E |

C29H50O2

|

430 |

1 |

| Sesquiterpenoids |

16.382 |

79887 |

0.46 |

Heptadecane, 2,6,10,15-tetramethyl- |

C21H44

|

296 |

1 |

| Sesterterpenoids |

23.279 |

67717 |

0.39 |

α-tocospiro b |

C29H50O4

|

462 |

1 |

| Triterpene |

23.039 |

256270 |

1.47 |

Squalene |

C30H50

|

410 |

1 |

| |

25.225 |

325188 |

1.87 |

24-Norursa-3,12-diene |

C29H46

|

394 |

1 |

Table 3.

Phytoconstituents in S. trilobatum HSF based on GC-MS analysis and the number of Lipinski’s violations.

Table 3.

Phytoconstituents in S. trilobatum HSF based on GC-MS analysis and the number of Lipinski’s violations.

| Chemical Class |

Retention Time |

Area |

Area % |

Compound Name |

Molecular Formula |

Molecular Weight, g/mol |

N Violations |

| Carboxylic ester |

8.134 |

83253 |

0.47 |

4-tert-butylcyclohexyl acetate |

C12H22O2

|

198 |

0 |

| Diterpene |

14.715 |

156057 |

0.89 |

Neophytadiene |

C20H38

|

278 |

1 |

| 15.822 |

113913 |

0.65 |

Biformene |

C20H32

|

272 |

1 |

| 17.387 |

1146616 |

6.54 |

Abieta-7,13-diene |

C20H32

|

272 |

1 |

| 17.823 |

192602 |

1.10 |

Verticiol |

C20H34O |

290 |

1 |

| 17.888 |

656202 |

3.74 |

Agathadiol |

C20H34O2

|

306 |

0 |

| 17.972 |

93879 |

0.54 |

Neoabietadiene |

C20H32

|

272 |

1 |

| 18.375 |

156065 |

0.89 |

Isodextropimaraldehyde |

C20H30O |

286 |

1 |

| 18.630 |

64779 |

0.37 |

Palustrinal |

C20H30O |

286 |

1 |

| 18.755 |

172913 |

0.99 |

Levopimarate |

C21H32O2

|

316 |

1 |

| 18.953 |

86383 |

0.49 |

Abieta-8,11,13-trien-18-a |

C20H28O |

284 |

1 |

| 19.317 |

1296637 |

7.39 |

Abietinol |

C20H32O |

288 |

1 |

| 19.924 |

113206 |

0.65 |

Neo abietal |

C20H30O |

286 |

1 |

| Ergostane steroids |

26.549 |

85471 |

0.49 |

Ergost-5-en-3-ol, (3.β.,24r)- |

C28H48O |

400 |

1 |

| Fatty acids |

22.477 |

212007 |

1.21 |

Galaxolide |

C14H26O4

|

258 |

0 |

| 16.674 |

166324 |

0.95 |

Tetradecanedioic acid, 3-oxo-, dimethyl ester |

C16H28O5

|

300 |

0 |

| Fatty acid ester |

17.334 |

162807 |

0.93 |

9-octadecenoic acid, methyl ester |

C19H36O2

|

296 |

1 |

| 17.562 |

152150 |

0.87 |

Methyl stearate |

C19H38O2

|

298 |

1 |

| 15.693 |

1029561 |

5.87 |

Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester |

C17H34O2

|

270 |

1 |

| Fatty alcohol |

14.820 |

30242 |

0.17 |

1-tetradecanol |

C14H30O |

214 |

1 |

| Organic hetero tricyclic |

14.883 |

279538 |

1.59 |

Hexamethyl-pyranoindane |

C18H26O |

258 |

1 |

| Phytosterol |

25.240 |

256252 |

1.46 |

Stigmast-5-en-3-ol, (3.β.)- |

C29H50O |

414 |

1 |

| 26.801 |

190485 |

1.09 |

Stigmasterol |

C29H48O |

412 |

1 |

| 27.474 |

299140 |

1.71 |

γ-sitosterol |

C29H50O |

414 |

1 |

| Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons |

7.360 |

378839 |

2.16 |

Azulene |

C10H8

|

128 |

0 |

| PUFA |

17.288 |

128833 |

0.73 |

Verticillol |

C18H32O2

|

280 |

1 |

| Sesquiterpene |

9.534 |

170825 |

0.97 |

Β -elemene |

C15H24

|

204 |

1 |

| 8.776 |

100393 |

0.57 |

Cyclohexene, 4-ethenyl-4-methyl-3-(1-methylethenyl)-1-(1 |

C15H24

|

204 |

1 |

| 9.729 |

140414 |

0.80 |

Cyperene |

C15H24

|

204 |

0 |

| 10.053 |

580731 |

3.31 |

Germacrene b |

C15H24

|

204 |

1 |

| 10.767 |

217949 |

1.24 |

Germacrene d |

C15H24

|

204 |

1 |

| 10.974 |

488025 |

2.78 |

Cedrelanol |

C15H26O |

222 |

0 |

| 11.263 |

41022 |

0.23 |

Cubebol |

C15H26O |

222 |

0 |

| 11.962 |

6051885 |

34.51 |

Germacrene d-4-ol |

C15H26O |

222 |

0 |

| 13.393 |

347188 |

1.98 |

Shyobunol |

C15H26O |

222 |

1 |

| 14.253 |

86532 |

0.49 |

Abietinal |

C15H26O |

222 |

0 |

| 18.557 |

55406 |

0.32 |

10,11-dihydroxy-3,7,11-trimethyl-2,6-dodecadienyl acetate |

C17H30O4

|

298 |

0 |

| Steroid |

13.979 |

599432 |

3.42 |

Ergostane-5,25-diol |

C39H76O6Si3

|

724 |

2 |

| Tetralins |

14.990 |

191432 |

1.09 |

Tonalid |

C18H26O |

258 |

|

| Triterpenoid |

16.499 |

136199 |

0.78 |

Manool oxide |

C20H34O |

290 |

1 |

| |

14.190 |

78086 |

0.45 |

7-dimethyl(chloromethyl)silyloxytridecane |

C16H35ClOSi |

306 |

1 |

| |

21.061 |

323290 |

1.84 |

Bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate |

C24H38O4

|

390 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).