1. Introduction

Seafood products, including shrimp, are highly valued and in high demand worldwide. However, their perishable nature makes effective preservation methods crucial to maintain their quality, safety, and sensory attributes throughout storage and distribution. Shrimp, in particular, are susceptible to various deteriorative processes such as microbial growth, enzymatic reactions, and oxidative deterioration, all of which contribute to quality loss and reduced shelf life. Among the challenges encountered in shrimp preservation, melanosis stands out as a common post-harvest problem that significantly affects the visual appeal and market value of the product [

1].

Melanosis is characterized by the enzymatic oxidation of phenolic compounds present in the exoskeleton of shrimp, leading to the undesirable darkening of their appearance [

2]. This enzymatic browning process not only affects the visual appeal of the shrimp but also serves as a precursor for microbial growth and spoilage, ultimately compromising their overall quality and marketability. Consequently, finding effective strategies to inhibit melanosis and maintain the quality of shrimp during storage is of utmost importance for the seafood industry [

3].

In recent years, there has been growing interest in the utilization of natural bioactive compounds as alternatives to synthetic additives in food preservation. One such group of compounds is phlorotannins, which are polyphenolic compounds abundant in marine brown algae [

4]. Phlorotannins have been recognized for their antioxidant and antimicrobial properties, making them potential candidates for inhibiting enzymatic browning and delaying spoilage in seafood products. Additionally, alginate, a natural polysaccharide extracted from various seaweed species, has been studied for its film-forming ability and potential as a food preservative [

5]. Both phlorotannins and alginate have been reported to exhibit inhibitory effects on PPO activity [

1,

6].

Considering the potential benefits of phlorotannins and alginate, the combination of these compounds in a rich extract form offers a promising solution for inhibiting melanosis and preserving the quality of shrimp during storage. However, specific research investigating the effects of phlorotannins-alginate-rich extract on melanosis inhibition and the overall quality of shrimp during iced storage is limited. The objective of this study was to investigate the effects of a phlorotannin-alginate-rich extract on melanosis development and the quality attributes of Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) during iced storage.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Seaweed Collection

The brown seaweed species

Sargassum cristaefolium and

Nizimuddinia zanardinii were manually collected from the intertidal zone of the coastal area near Chabahar city, Iran, in December and November 2024, respectively. The collected samples were transported to the laboratory of Chabahar Maritime University for further analysis. Species confirmation was conducted by referencing validated identification keys [

7]. Upon arrival at the laboratory, the seaweed samples were first rinsed with freshwater to remove any impurities such as sand, shells, and other debris. Then, the samples were dried in shade to a constant weight. The dried samples were then ground into a fine powder using a household Philips blender (manufactured in Japan). To prevent degradation of the bioactive compounds present in the seaweed, the powdered samples were stored in airtight zip-lock plastic bags and kept in a freezer at -20 °C until the extraction process.

2.2. Preliminary Solvent Screening and Extraction Procedure

To determine the most efficient solvent for the extraction of phlorotannins and alginate from the seaweed samples, 50 g of the powdered samples were combined with 200 mL of the following solvents: 100% methanol, 70% methanol, 30% methanol, 100% water, 100% ethyl acetate, 70% ethyl acetate, and 30% ethyl acetate. The mixtures were shaken at room temperature for two hours using a lab shaker. Each solution was then filtered through a Whatman filter paper (No. 1) to remove any insoluble debris. The filtrates were then concentrated using a rotary vacuum evaporator (RV8V-C, IKA, Germany) under reduced pressure at 50 ℃ until a thick paste was obtained. The yield of the extract, the concentration of phlorotannins and DPPH free-radical scavenging activity were determined for each solvent as described by Sharifian

et al. [

1]. The results of this section revealed that the extraction using 100% methanol exhibited superior efficiency compared to other solvents. Additionally, when comparing the two types of algae,

N. zanardinii demonstrated higher content of bioactive compounds, specifically phlorotannins, compared to

S. cristaefolium. Considering these findings, further experiments for the extraction of phlorotannins and alginate were conducted using 100% methanol as the solvent and

N. zanardinii as the selected seaweed species.

2.3. Extraction and Assay of Phlorotannins (PT)

The extraction, purification, and quantification of phlorotannins were conducted following the procedure described by Sharifian et al. [

1], with slight modifications. Briefly, 500 g of

N. zanardinii powder was subjected to extraction by shaking with 2L of 100% methanol at room temperature for two hours. The resulting solution was filtered, and the solvent was removed, yielding the “first extract.” The solid residue obtained after filtration, containing the remaining biomass, was used for alginate extraction and set aside for further analysis. To the first extract, 4 L of chloroform was added and shaken for 5 minutes. The resulting mixture was then partitioned into upper and lower layers by adding 200 mL of distilled water. The upper fraction was subsequently partitioned with dichloromethane (DCM) and ethyl acetate. The fractions obtained were dried using a rotary evaporator, resulting in the production of the DCM, ethyl acetate, and aqueous fractions. The residue from the ethyl acetate fraction, referred to as crude phlorotannins (PT), was retained for further analysis. Additionally, the crude PT was utilized for the dipping treatment of shrimp samples prior to iced storage. The total phlorotannins content in each extract was analyzed using the Folin-Ciocalteu procedure, employing phloroglucinol (PGH) as a standard. The absorbance of each extract was measured at 700 nm using a UV 160A spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Croissy, France), as described by Sharifian et al. [

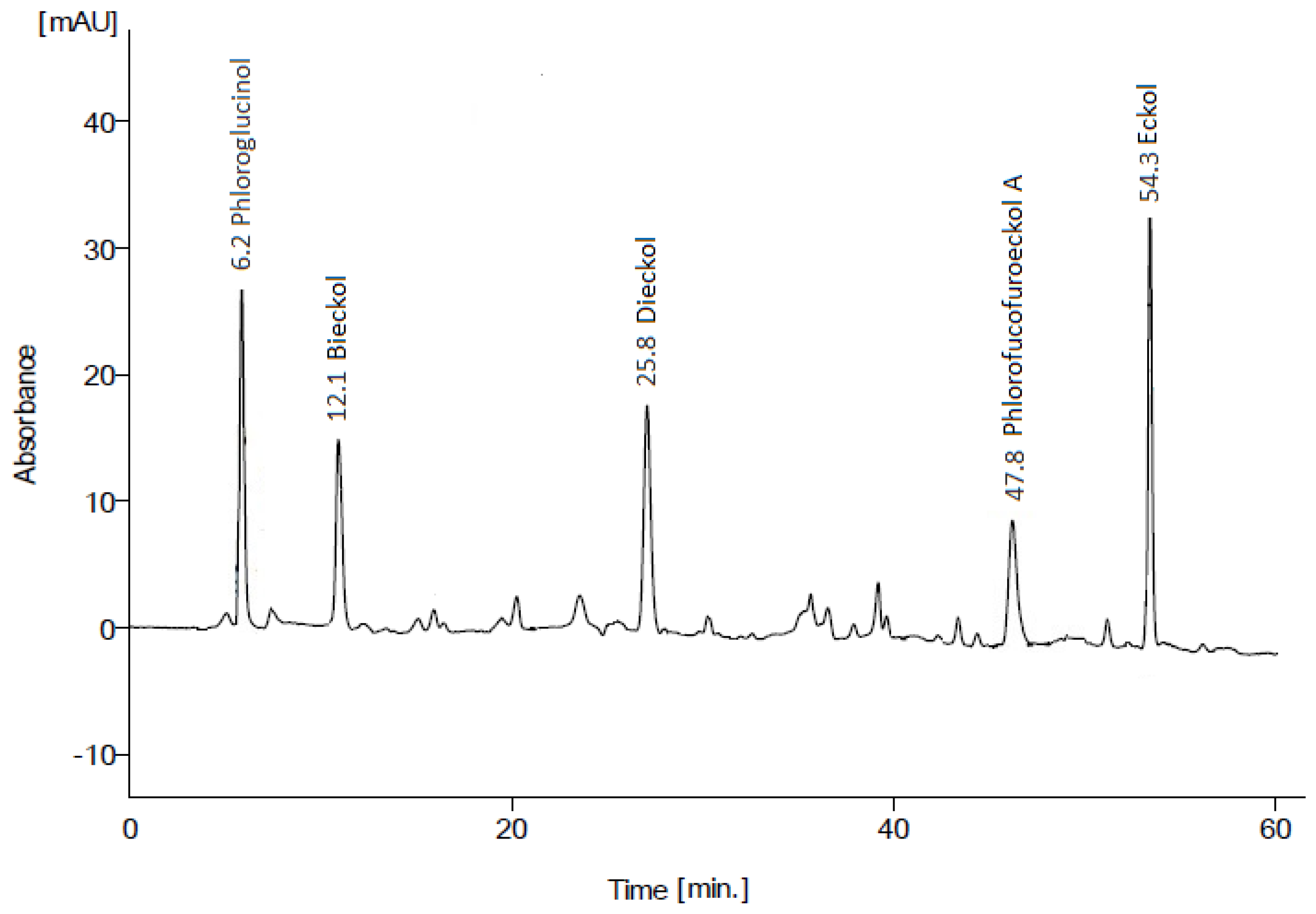

1]. Furthermore, the composition of crude PT was assessed using column and thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on silica gel. For the quantification of the product, a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Knauer-Germany) equipped with an Azura photodiode array detector 6.1L and an AcclaimTM 120 C18 column (5 μm particle size, i.d. 4.6×250 mm) was employed. A gradient mobile phase composed of solvent A (1% formic acid in water) and solvent B (acetonitrile) was used at a flow rate of 1 mL/min (60 min) to separate the samples. The injection volume was set at 15 μL, and the detection wavelength was monitored at 280 nm.

2.4. Extraction of Alginate

The extraction of alginate from

N. zanardinii seaweed was performed following the method outlined by Rostami et al. [

8]. Fifty grams of seaweed residue obtained from the previous step were combined with 400 mL of sterile distilled water and subjected to agitation on a heat shaker at 65 °C for three hours. This process was repeated twice, and the residues from all three experiments were collected by centrifugation at 5000 g for 10 minutes. To the resulting residue, distilled water was added to bring the volume to one liter. Subsequently, the pH was adjusted to 11 by the addition of 3% Na

2CO

3. The resulting mixture was then centrifuged, and the separated liquid portion was mixed with an equal volume of 70% ethanol. After 12 hours, the sedimentation that formed was collected as the separated alginate. To remove excess water, the obtained alginate was thoroughly washed with water and ethanol several times. Following the washing steps, the alginate was dried under a hood and collected for further analysis.

2.5. Cupric Ion Chelating Activity

Cupric ion chelating activity was assessed following the method described by Wong et al. [

9]. The extracts were initially mixed with hexamine-HCl buffer (10 mM, pH 5) at a concentration of 1 mg/mL. One milliliter of the prepared mixture was then combined with 1 milliliter of copper sulfate II solution (0.4 μM) and 100 microliters of TMM (tetramethylmurexide ammonium salt) solution (2 mM). The absorbance was measured at 460 nm and 530 nm. To determine the chelating capacity, the absorption ratio was calculated using a standard curve. The percentage of copper ion chelation was reported based on the measured chelating activity of the extracts.

2.6. Effect of Phlorotannins and Alginate Extract on the Inhibition of Pacific White Shrimp PPO

2.6.1. Shrimp Sample Preparation

Pacific white shrimps (L. vannamei) with a size of 55-60 shrimps/kg were obtained from a local supplier in Chabahar, Iran. The shrimps were freshly caught and free from any preservatives. Upon arrival at the laboratory, the shrimps were washed with cold water (1-3 ℃) and stored in ice until further use, with a maximum storage time of 2 hours.

2.6.2. Extraction of PPO

The extraction of polyphenol oxidase (PPO) was carried out following the method described by Nirmal and Benjakul [

10]. Briefly, the cephalothoraxes of twenty whole shrimps were separated, frozen using liquid nitrogen, and then powdered using a Waring commercial blender (USA). The resulting powder was suspended in 150 mL of the extracting buffer (0.05 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, containing 1.0 M NaCl and 0.2% Brij-35). After stirring for 30 minutes at 4 ℃, the mixture was centrifuged (30 minutes, 8000g, 4 ℃) using a refrigerated centrifuge (Hettrich Centrifuge Rotina 420 R, Germany). The supernatant was precipitated by adding solid ammonium sulphate until 40% saturation. The resulting precipitate was collected, dissolved in 0.05 M sodium phosphate buffer, and dialyzed against the same buffer. After removing insoluble materials by centrifugation, the resulting supernatant was collected and used as the “crude PPO extract.”

2.6.3. PPO Inhibitory Activity of Phlorotannins and Alginate

To determine the most effective inhibitor and achieve high inhibition of PPO, various concentrations and combinations of phlorotannins (PT), alginate (AG), and sodium metabisulfite (SM) were evaluated. The tested solutions included: 0.1% PT, 0.5% PT, 1% PT, 1% SM, 1% AG, 1%PT+0.5%AG, 2%PT+1%AG, and 1% ascorbic acid (AA). The PPO inhibitory activity of each solution was assessed using a continuous assay with L-DOPA as the substrate, following the method outlined by Nirmal and Benjakul [

10]. Briefly, 100 μL of each solution was mixed with the crude PPO extract and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature. Subsequently, 400 μL of 0.05 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) was added to the mixture, followed by the addition of 600 μL of pre-incubated 15 mM L-DOPA (45 °C). The reaction was conducted at 45 °C, and the rate of dopachrome formation was continuously monitored for 3 minutes at 475 nm. The increase in absorbance per unit of time was used to determine the enzyme activity, with each 0.001 increase in absorbance per minute representing one unit of PPO activity. The inhibitory activity was expressed as the percentage inhibition, calculated using the following formula: Inhibition (%) = (A - B) / A × 100; where A represents the PPO activity of the control and B represents the PPO activity in the presence of the inhibitor.

2.7. Effect of Phlorotannins and Alginate Extract on the Quality of Pacific White Shrimp During Iced Storage

2.7.1. Treatment of Shrimp with Phlorotannins (PT) and Alginate (AG)

Dipping treatments of whole shrimp were carried out by immersing the shrimp in solutions of 1%PT, 1%PT+0.5%AG, and 2%PT+1%AG for 10 minutes at 4 °C. The positive control treatment consisted of shrimp dipped in 1.25% sodium metabisulfite (SM) solution at 4 °C [

10]. A shrimp to solution ratio of 1:2 (w/v) was maintained during the dipping treatments. Untreated shrimp were used as the control. After treatment, the shrimp were removed from the solutions, allowed to drain for 5 minutes, and then stored in separate polyethylene boxes filled with flaked ice. The shrimp to ice ratio was maintained at 1:2 (w/w), and ice was replenished every 12 hours. The boxes were provided with holes at the bottom for drainage of melted ice. At predetermined intervals of 4 days over a 16 day period, 15 shrimp were randomly sampled from each treatment for melanosis evaluation, chemical, microbiological, and sensory analyses.

2.7.2. Melanosis Evaluation

Melanosis formation was evaluated visually by a panel of seven trained assessors as described by Nirmal and Benjakul [

10]. The panellists examined whole shrimp and assigned melanosis scores based on a 10-point scale, where a score of 0 indicated no observable melanosis and a score of 10 denoted extremely heavy melanosis. Each shrimp sample was evaluated blindly and independently by the panel. Additionally, the progression of postharvest melanosis was photographically documented throughout the storage period using a Canon IXUS digital camera under constant lighting conditions and standardized camera angles. Multiple images were captured for each sample at regular intervals during iced storage to visually complement the panel evaluation data.

2.7.3. pH and Total Volatile Basic Nitrogen (TVB-N) Measurement

The pH of shrimp samples was determined using a HM-205 pH meter (Japan). Shrimp meat was homogenized with distilled water at a 1:5 (w/v) ratio for 1 minute and kept at room temperature for 5 minutes. The pH was measured by immersing the electrode directly into the homogenate.

TVB-N content was measured according to Kılınç et al. [

11] and expressed in mg N/100g shrimp meat. 10 grams of ground shrimp meat was mixed with 40 ml distilled water in a distillation flask. 1 gram of magnesium oxide and a few drops of silicone antifoam were added. The mixture was distilled and the distillate collected in a 500 ml conical flask containing 3% boric acid solution and Tashiro indicator. The distillate was titrated with 0.1 N hydrochloric acid solution. TVB-N was calculated using the formula: TVB-N (mg⁄100g meat) = ((V ×C ×14)/10)×100; Where V is the titrant volume (ml) and C is the titrant concentration (N).

2.7.4. Peroxide Value (PV) Determination

Lipid extraction was done following the Bligh and Dyer [

12] method. 50 g shrimp meat was homogenized with 150 mL chloroform: methanol (2:1 v/v) using a Waring blender. The homogenate was filtered and the lipid-containing lower phase collected. The solvent was removed using a rotary evaporator and nitrogen flushing.

PV was determined by the AOAC [

13] method and expressed in mEq active O2/kg lipid. 0.3 g lipid sample was dissolved in 10 mL chloroform-acetic acid and mixed with 1 mL saturated KI solution. After 5 minutes, 20 mL distilled water was added. The mixture was titrated with 0.1 N sodium thiosulfate until the yellow color disappeared. 1 mL 1.5% starch indicator was added and titration continued until the blue color disappeared. A blank with no lipid was run simultaneously.

2.7.5. Thiobarbituric Acid (TBA) Determination

TBA was determined by the method of Benjakul and Bauer [

14] and expressed as mg malondialdehyde/kg shrimp meat. 1 g shrimp meat was mixed with 9 mL 0.25 N HCl containing 0.375% TBA and 15% trichloroacetic acid (TCA). The mixture was heated at 100 °C for 10 minutes then cooled. After centrifugation at 4000 g for 20 min, the supernatant absorbance was measured at 532 nm. TBA value was calculated from a malondialdehyde standard curve.

2.7.6. Microbial Analyses

Total counts of mesophilic (MBC) and psychrotrophic bacteria (PBC) were determined for shrimp samples from each treatment. 10 g of shrimp meat was homogenized with 90 mL sterile Butterfield’s phosphate buffer for 3 minutes using a stomacher blender. Serial dilutions were prepared in sterile phosphate buffer. MBC were enumerated on PCA agar (Merck) incubated at 37 °C for 24-48 hours. PBC were enumerated on PCA agar incubated at 5 °C for 72 hours.

2.7.7. Sensory Evaluation

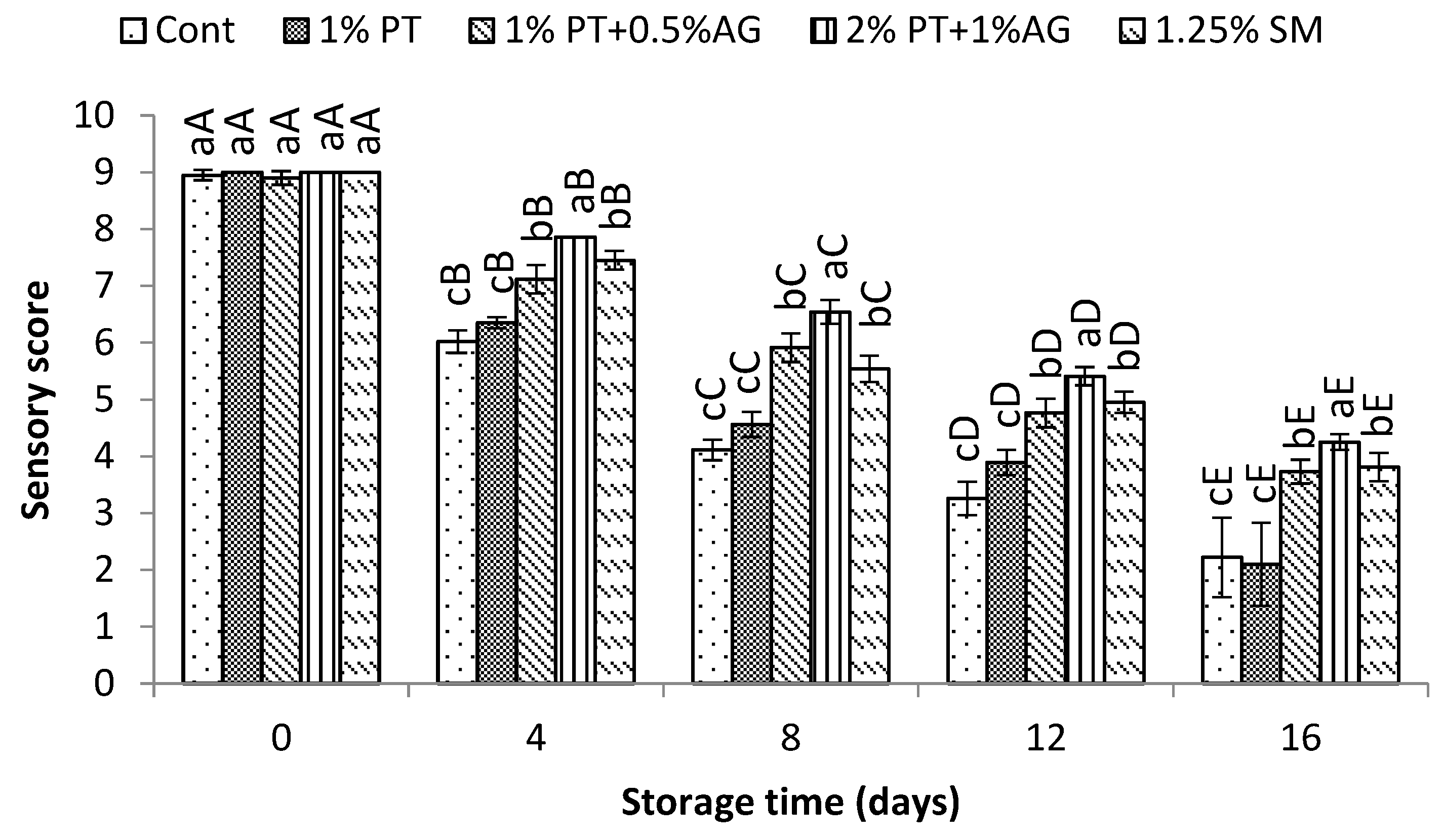

Sensory analysis was performed according to Li et al. [

15] using a 7-member trained panel. 25 shrimp from each treatment were evaluated on each sampling day. A 9-point hedonic scale was used where 9 = highest quality and 1 = lowest quality. Scores below 5 were considered unacceptable. Attributes evaluated included appearance, odour, texture and overall acceptability.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were carried out in triplicate. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA using SPSS 13.0 software. Means were compared using Tukey’s test at a significance level of p<0.05. Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Preliminary Solvent Screening

The extract yield, phlorotannins content, and antioxidant activity of extracts obtained from

S. cristaefolium and

N. zanardinii using different solvents are presented in

Table 1. For

S. cristaefolium, the highest extract yield of 5.50±0.29 g/100 g seaweed was obtained using 70% methanol, while 100% methanol resulted in an extract yield of 4.23±0.11 g/100 g seaweed. However, the phlorotannins content and antioxidant activity determined by DPPH assay were higher for the 100% methanol extract (6.39±0.07 mg PHG/g and 52.63±0.99%, respectively) compared to the 70% methanol extract (5.33±0.09 mg PHG/g and 48.08±0.96%, respectively). For

N. zanardinii, the 100% methanol extract provided the highest extract yield (6.43±0.09 g/100 g seaweed), phlorotannins content (9.39±0.27 mg PHG/g) and DPPH radical scavenging activity (73.27±0.94%). The 100% water extract for both seaweeds showed the lowest phlorotannins content and antioxidant activity. Ethyl acetate extracts demonstrated high phlorotannins content and antioxidant activity, however the extract yields were low compared to aqueous methanol extracts. Based on the preliminary screening results, 100% methanol was selected as the most suitable solvent for further extraction of phlorotannins and alginate from

N. zanardinii, as it provided high extract yield and maximum phlorotannins content with potent antioxidant activity. Previous studies have also reported superior extraction of seaweed phlorotannins using aqueous methanol compared to other solvents [

16,

17]. The high polarity of methanol allows effective extraction of the phenolic components responsible for the observed bioactivities.

3.2. Phlorotannins Content and Bioactivities of N. zanardinii Extracts

The extract yield, phlorotannins content, antioxidant activity (DPPH assay), and copper chelating activity of the initial methanol extract and subsequent fractions of

N. zanardinii are presented in

Table 2. The first methanol extract showed the highest extract yield of 6.43±0.09 g/100 g seaweed as well as potent antioxidant activity of 73.27±0.94% DPPH inhibition and moderate copper chelating ability (43.45±1.17% inhibition). Among the fractions, the ethyl acetate fraction demonstrated the maximum phlorotannins content of 19.14±0.65 mg PGH/g extract as well as the highest antioxidant (98.95±0.74% DPPH inhibition) and copper chelating activities (73.44±1.64% inhibition). The dichloromethane fraction also showed relatively high phlorotannins content and antioxidant activity. In contrast, the hexane fraction contained negligible phlorotannins and poor bioactivities. The high concentration of phlorotannins in the

N. zanardinii ethyl acetate fraction correlates well with several previous studies that have reported ethyl acetate as an efficient solvent for enriching phlorotannins from brown algae. For example, Li et al. [

18] found that sequential extraction with acetone and ethyl acetate yielded an extract from

Sargassum fusiforme with the highest phlorotannins content (88.48 ± 0.30 mg PGE/100 mg extract) and antioxidant activity. Similarly, Almeida et al. [

19] showed that ethyl acetate extraction provided enrichment of low molecular weight phlorotannins from

Fucus spiralis. The relatively non-polar nature of ethyl acetate allows preferential solubilisation of low and medium molecular weight phlorotannins, leaving higher molecular weight compounds concentrated in the residue [

20] Ethyl acetate fractions from

Fucus vesiculosus [

21],

Sargassum muticum [

22] and

Scytosiphon lomentaria [

23] have also shown high phlorotannin contents up to 24% dry weight. The composition of the phlorotannins extracted from

N. zanardinii was further analyzed by HPLC, as shown in

Figure 1. The chromatogram indicates that the extract contained a diversity of phlorotannin compounds. Quantification revealed that the major components were eckol (19.2%), phloroglucinol (16.3%), dieckol (9.9%), bieckol (8.6%), and phlorofucofuroeckol A (8.4%), along with 37.6% of other minor compounds. This profile is consistent with previous characterization of phlorotannins from brown algae, where eckol, phloroglucinol, fuhalols and other phlorotannin derivatives are commonly found [

1,

24]. The variety of mono-, di-, and trimer phlorotannin structures likely contributes to the potent antioxidant and bioactive properties observed for the

N. zanardinii extracts.

3.3. Yield and Bioactivities of Alginate from N. zanardinii

In addition to phlorotannins, the polysaccharide alginate was extracted from

N. zanardinii and its yield and antioxidant properties characterized as shown in

Table 3. An alginate extraction efficiency of 4.73 ± 0.38 g per 100 g of seaweed was achieved. The purified alginate extract contained appreciable levels of phenolic compounds (6.64 ± 0.41 mg PGH/g). This phenolic content correlated with moderate antioxidant activities, as the alginate demonstrated 23.07 ± 1.67% DPPH radical scavenging and 43.47 ± 0.99% copper chelating abilities. The obtaining of alginate with inherent antioxidant capacity has been reported previously in brown algae. Borazjani et al. [

25] extracted alginate from

Sargassum spp. that showed DPPH radical scavenging in the range of 39-66%. Antioxidant alginates isolated from

Lessonia trabeculata [

26] and

Sargassum wightii [

27] also exhibited phenolic contents of 4-8 mg GAE/g. The phenolic compounds are likely integrated into the alginate polysaccharide matrix through covalent linkages [

28], conferring its natural bioactive properties.

3.4. PPO Inhibitory Activity of Phlorotannins and Alginate

The inhibitory effects of phlorotannins, alginate, and their combination on polyphenol oxidase (PPO) from Pacific white shrimp are shown in

Table 4. At 0.1%, the phlorotannin extract exhibited weak PPO inhibition of 13.30%. However, increasing the concentration to 0.5% and 1% significantly enhanced the PPO inhibitory activity to 32.67% and 68.37%, respectively. The inhibitory effect was concentration-dependent. Similarly, the synergistic blend of 1% phlorotannins + 0.5% alginate showed 76.65% PPO inhibition, surpassing their individual activities. Of the treatments tested, 2% phlorotannins + 1% alginate exhibited the highest PPO inhibition at 84.51%, which was on par with 1% ascorbic acid (72.43%). This indicates the synergistic combination of phlorotannins and alginate can match or even exceed the PPO inhibitory effect of the common reference standard ascorbic acid. The inhibitory effects of phlorotannins, alginate, and their combinations on polyphenol oxidase (PPO) have been documented in several studies. Kurihara and Kujira [

29] reported concentration-dependent PPO inhibition reaching 68-85% for phlorotannin extracts from the brown algae

Colpomenia bullosa at levels of 0.5-1 mg/mL. Li et al. [

30] found a synergistic effect of polyphenols and polysaccharides in inhibiting PPO from the Pacific white shrimp. Phlorotannins are thought to inhibit PPO activity through several mechanisms, including chelation of the copper cofactor needed for PPO function, direct binding to enzymes to block active sites, and interaction with PPO substrates such as phenols to render them unavailable [

1]. The diverse structures of phlorotannins allow for multiple modes of action. Alginate has also exhibited PPO inhibition. Xu et al. [

31] found that the use of 2% sodium alginate during refrigerated storage could inhibit PPO activity. Combining alginate with organic acids has been found to further improve PPO inhibition compared to individual compounds [

32]. Alginate’s polysaccharide structure may enable interactions with PPO proteins. Furthermore, when combined with polyphenolic compounds, alginate could confer additional antioxidant effects against PPO. However, further research is needed to fully characterize alginate’s specific mechanisms of PPO inhibition and how these may be influenced when coupled with different phenolic components.

3.5. Effect of Phlorotannins and Alginate Extract on the Quality of Pacific White Shrimp During Iced Storage

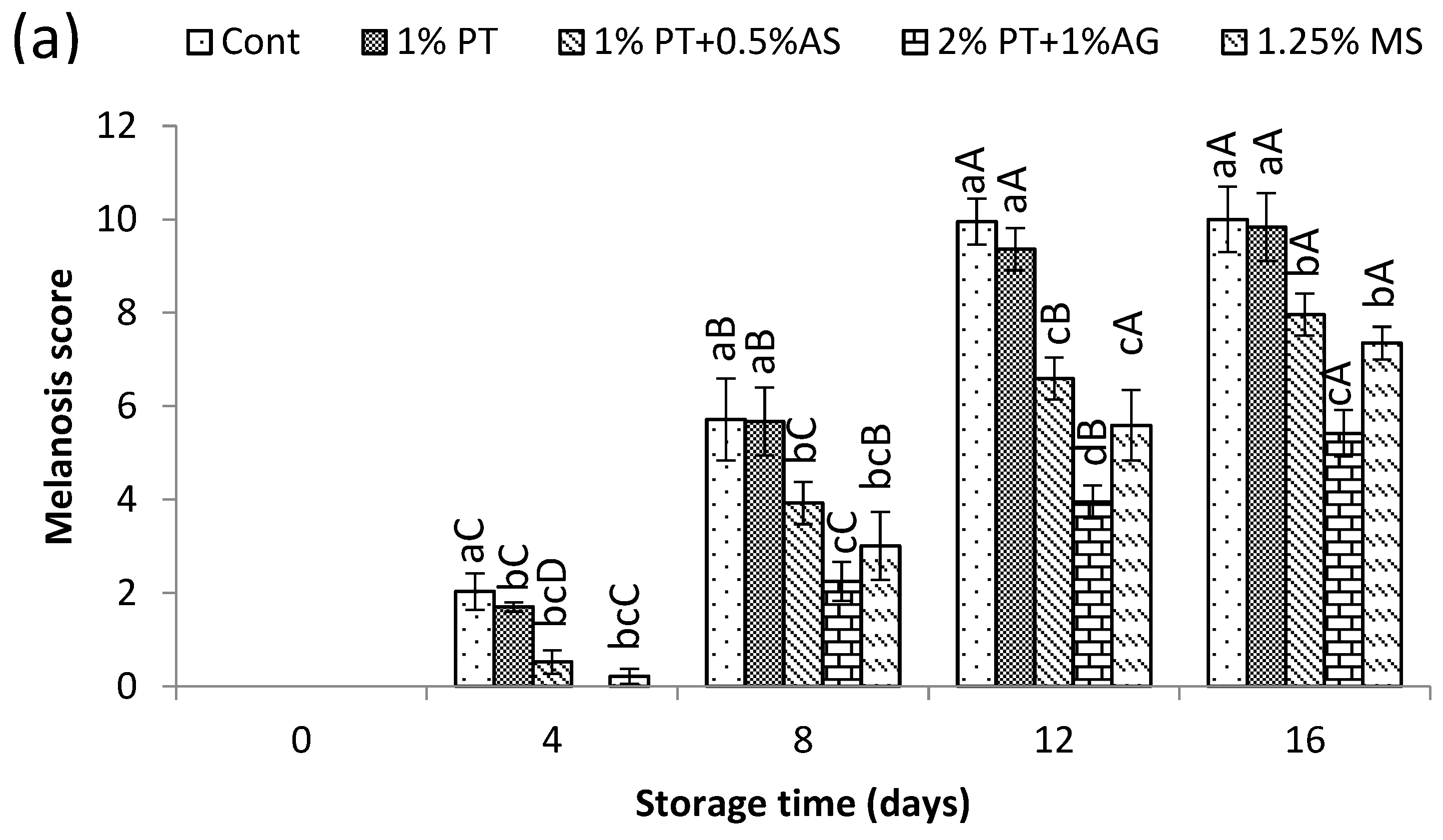

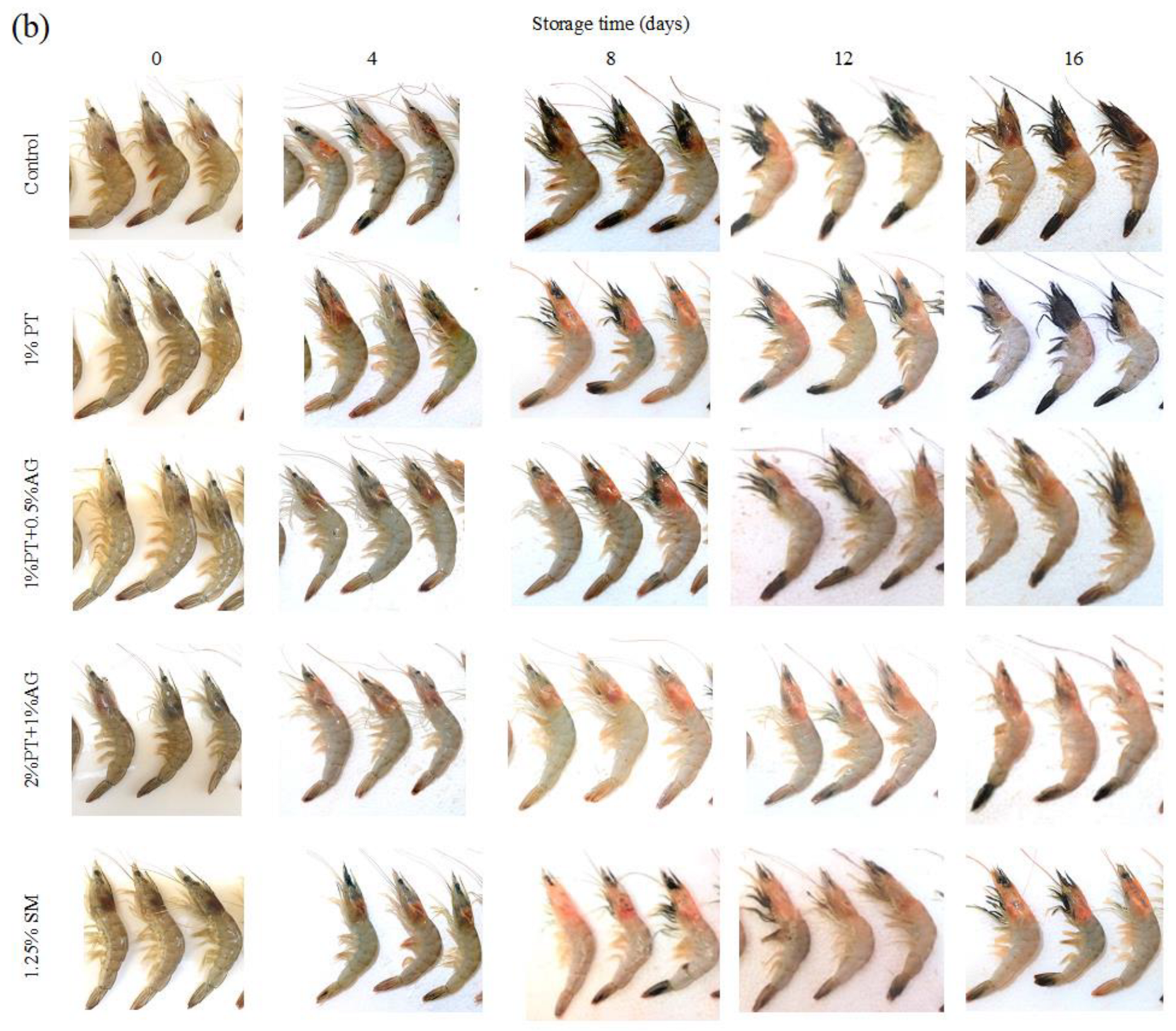

3.5.1. Melanosis Changes

Figure 2 (a) and (b) present the effect of phlorotannins and alginate treatment on inhibiting melanosis formation in Pacific white shrimp during 16 days of iced storage. Over the storage period, the visual melanosis score increased for all treatments as seen in

Figure 2 (a). However, shrimp treated with 2% phlorotannins (PT) + 1% alginate (AG) exhibited significantly lower scores compared to the control (P<0.05). After 16 days, the melanosis score reached 6.93 in the control versus only 2.67 with 2% PT + 1% AG (P<0.05). The lower melanosis scores align with our previous study, where we found phlorotannin extracts decreased melanosis in chilled shrimp [

1]. Shiekh et al. [

3] also reported that dipping in the extracts rich in polyphenols (Chamuang leaf extract; 1% w/w) delayed melanosis in Pacific white shrimp compared to controls.

Figure 2 (b) shows representative images of melanosis progression. The untreated control displayed considerable black spot formation by day 16. In contrast, shrimp treated with 2%PT+1%AG showed minimal darkening, comparable to 1.25% SM.

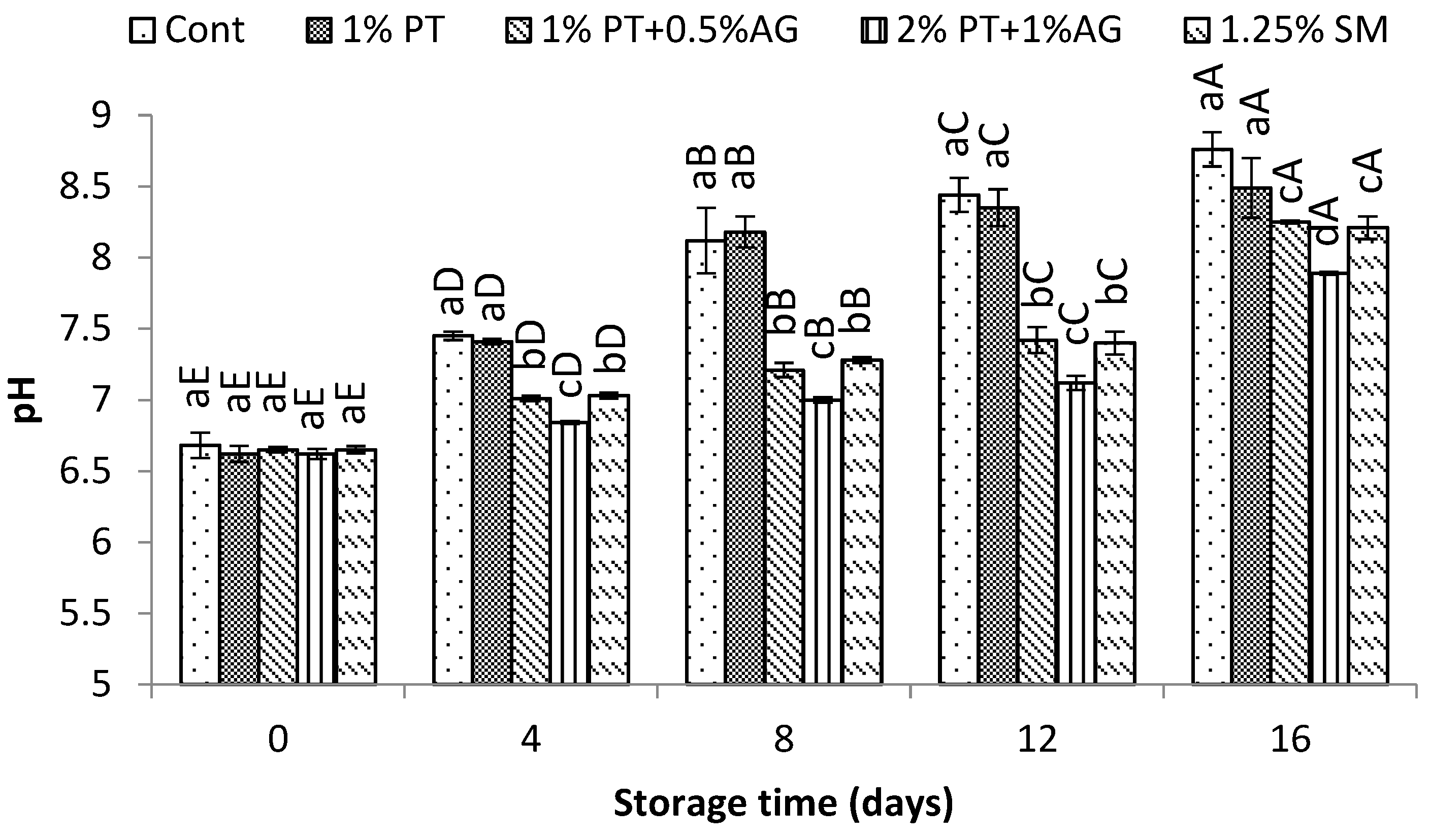

3.5.2. Physicochemical Changes

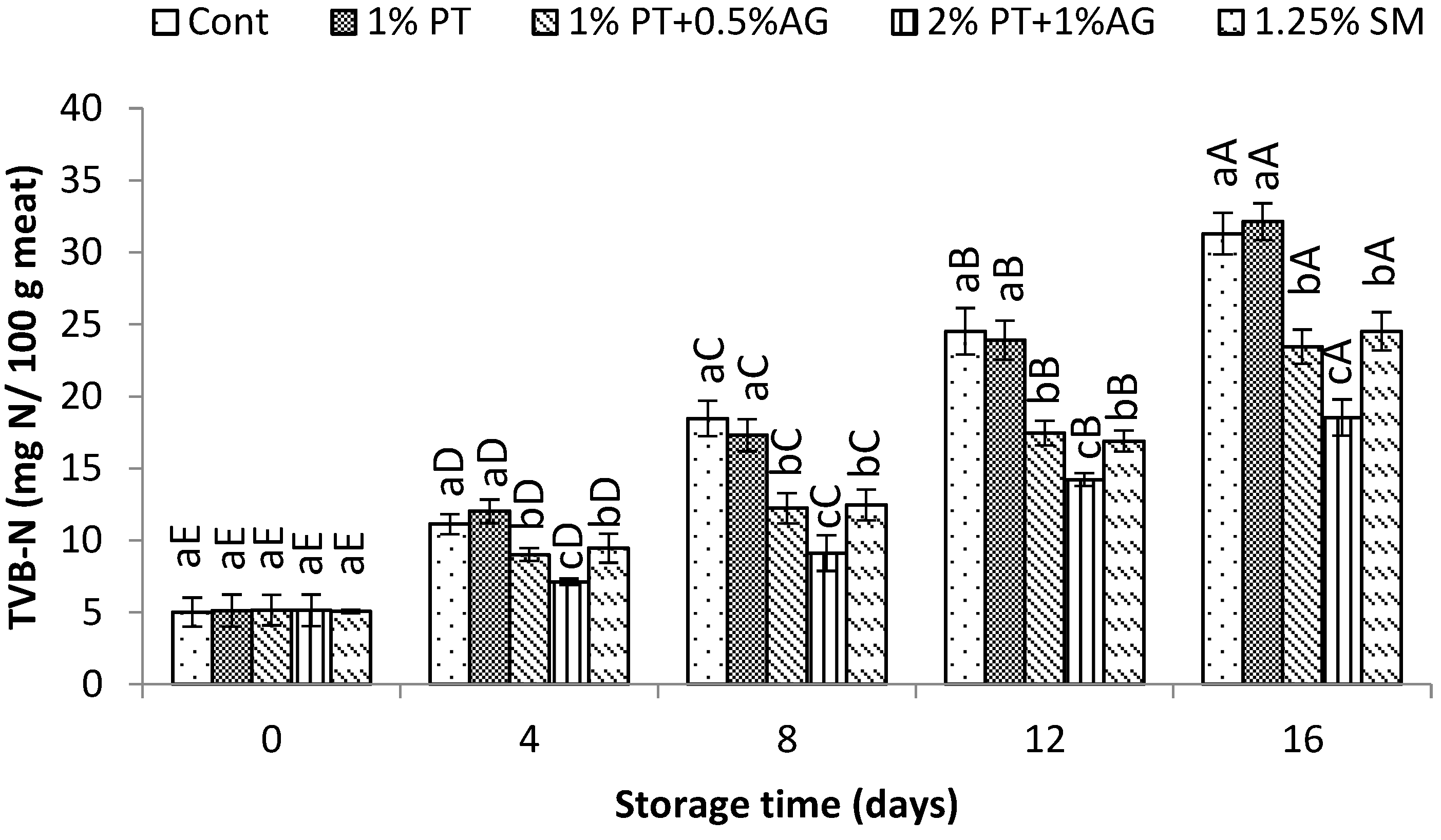

The effects of phlorotannins and alginate treatment on quality indices including pH, TVB-N, PV, and TBA in shrimp during chilled storage are presented in

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. The pH of shrimp muscle gradually increased over the 16 day storage period (

Figure 3). However, shrimp dipped in 2%PT+1%AG maintained a significantly lower pH from day 8 onwards compared to control (P<0.05). By day 16, the pH reached 7.8±0.11 in control versus 7.3±0.09 in treated shrimp (P<0.05). The gradual pH increase in shrimp muscle during chilled storage indicates accumulation of alkaline compounds like ammonia from protein breakdown. The slower pH rise in PT+AG treated shrimp aligned with their lower TVB-N values (

Figure 4) and microbial counts (

Figure 7a and b), indicating inhibited protein decomposition and bacterial growth. Other studies on polyphenolic extracts in shrimp also found effective pH control. Li et al. [

30] reported smaller increases in pH for Pacific white shrimp treated with 5 g/L polyphenol and 8 g/L polysaccharides extracted from

Porphyra yezoensis (red algae) compared to controls during refrigerated storage. They attributed the lower pH to antimicrobial effects of phenolic compounds. Similarly, the phlorotannins and alginate in the current study likely suppressed microbial activity, slowing the pH increase.

The changes in TVB-N content of shrimp samples during storage are shown in

Figure 4. A general increase in TVB-N values was observed over time for all treatments, indicative of on-going protein degradation. However, shrimp treated with PT+AG maintained significantly lower (P<0.05) TVB-N levels compared to the control from Day 8 onwards. By the end of storage on Day 16, TVB-N reached 46.8±2.3 mg N/100g in the control shrimp, while 2%PT+1%AG treated shrimp showed only 28.4±1.9 mg N/100g (P<0.05). Previous research has demonstrated that phlorotannins exhibit antimicrobial properties against diverse seafood spoilage bacteria [

33]. In this study, the inhibitory effect of PT+AG treatment on TVB-N accumulation can be attributed to the antimicrobial activity of phlorotannins suppressing microbial-driven proteolysis and TVB-N production, as supported by reported reductions in total viable count and psychrotrophic bacteria in seafood imparted with phlorotannin extracts [

1] Additionally, alginate component may have formed an antioxidant film on shrimp surfaces in combination with phlorotannins, acting as a barrier against microbial infiltration and enzymatic deterioration of proteins over time [

30] Hence, through multifactorial mechanisms, the 2%PT+1%AG treatment very effectively controlled TVB-N accumulation and maintained better protein quality in Pacific white shrimp compared to untreated samples.

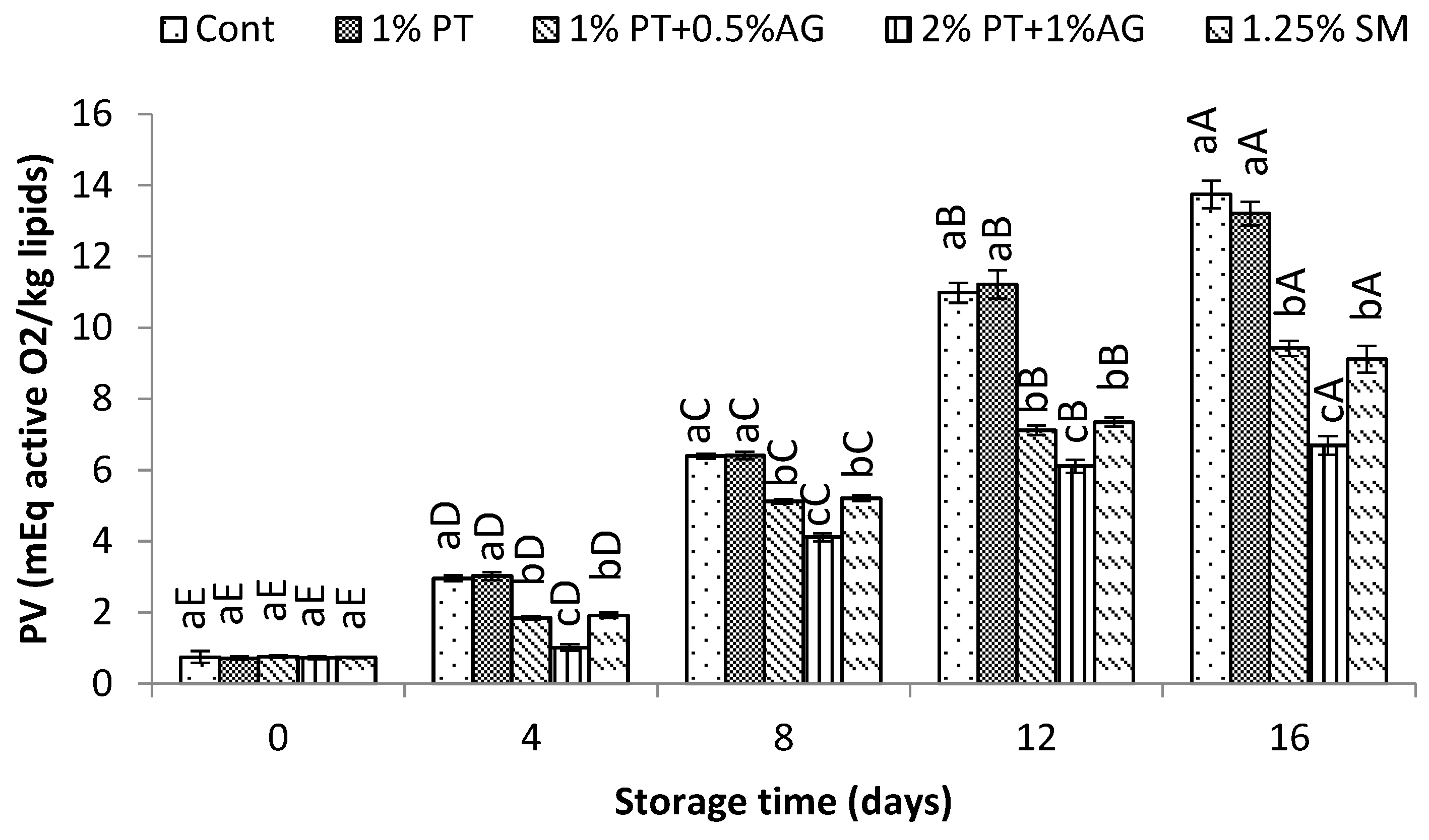

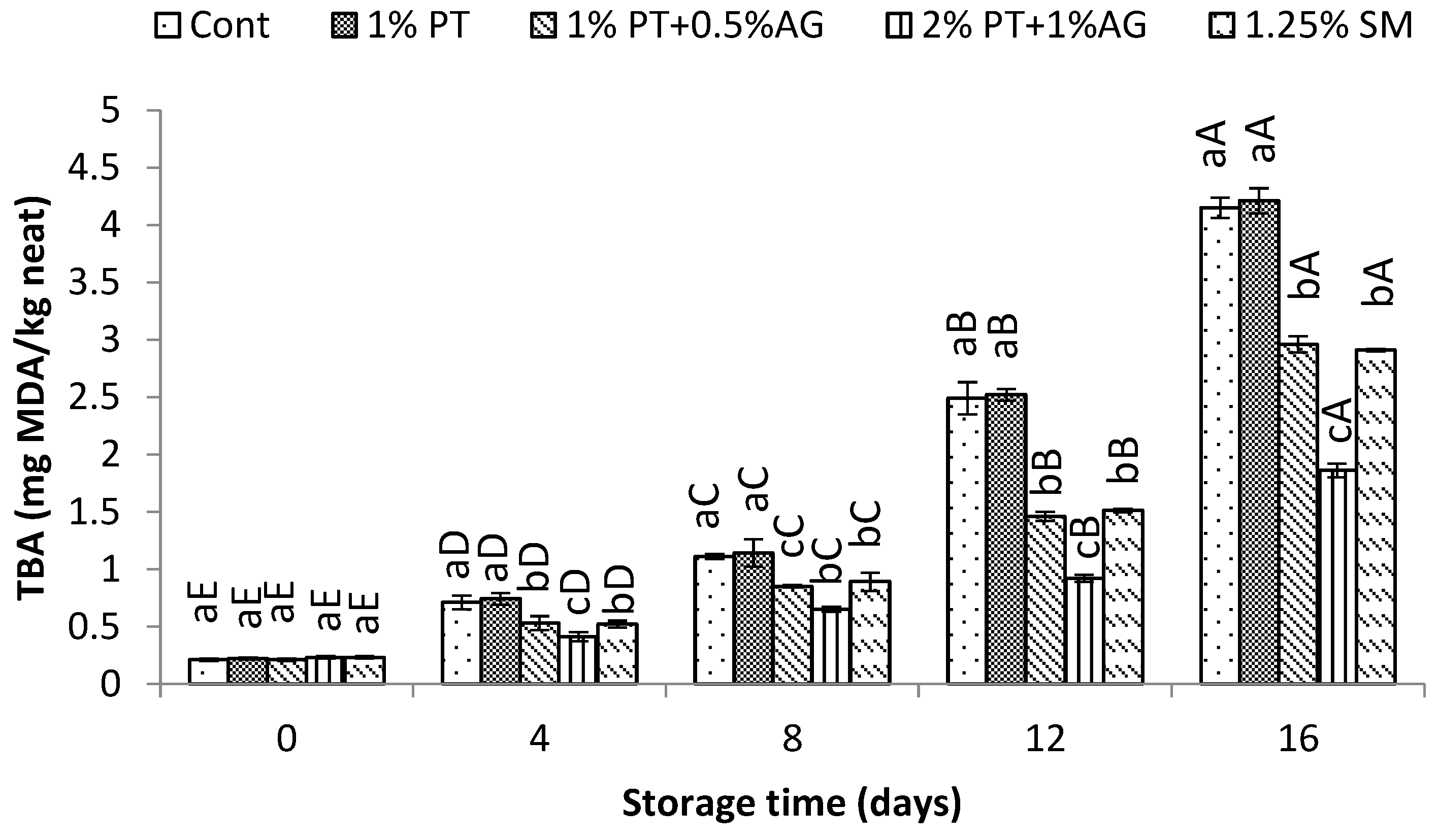

As seen in

Figure 5, PV increased gradually during storage for all samples due to lipid oxidation. However, 2%PT+1%AG treated shrimp maintained significantly lower PV compared to control (P<0.05). By day 16, PV was 20.5±1.2 mEq active O2/kg lipid in control versus 12.3±0.8 mEq active O2/kg lipid in treated shrimp. Similarly, TBA values increased over time for all samples as a result of secondary lipid oxidation products (

Figure 6). However, PT+AG treated shrimp exhibited significantly lower TBA content, indicating reduced lipid oxidation. By day 16, TBA reached 5.8±0.4 mg MDA/kg in control compared to 3.2±0.2 mg MDA/kg in treated shrimp (P<0.05). The lower PV and TBA values obtained with 2%PT+1%AG treatment can be attributed to the combined antioxidant and antimicrobial effects of phlorotannins and alginate. Previous studies have reported inhibitory effects of phlorotannins on lipid oxidation in shrimp and fish [

1]. Additionally, alginate films enriched with phlorotannins exhibited improved antioxidant activity in foods [

34]. Phlorotannins and alginate likely acted synergistically to suppress auto-oxidation and microbial proliferation, maintaining lower levels of protein deterioration and lipid oxidation in shrimp over the 16-day iced storage period.

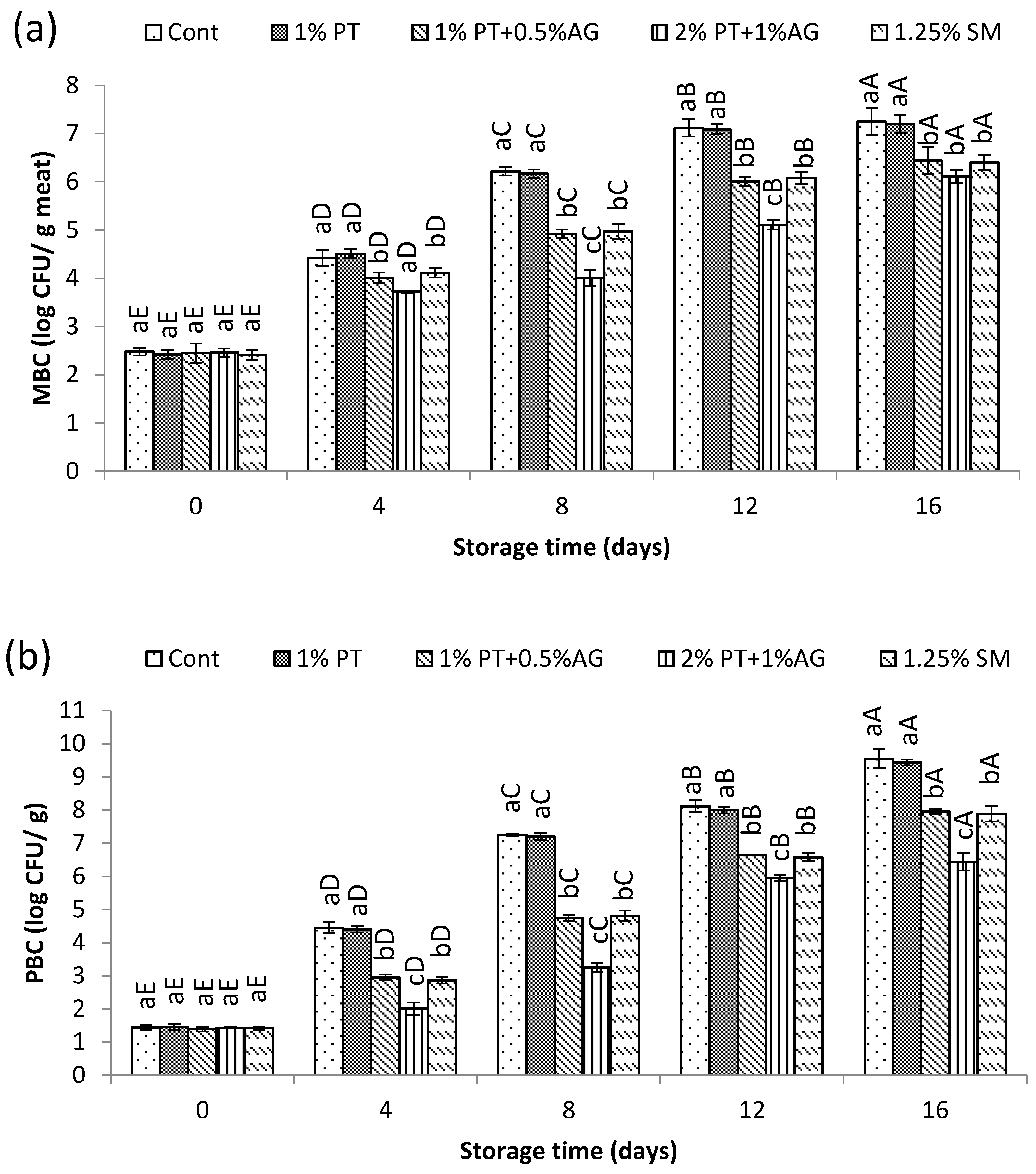

3.5.3. Microbial Changes

The changes in total mesophilic bacteria (MBC) and psychrotrophic bacteria counts (PBC) during storage are shown in

Figure 7 (a) and (b). In general, bacterial numbers increased with storage time for all samples. However, shrimp treated with 2%PT+1%AG demonstrated significantly lower (P<0.05) microbial growth compared to the untreated control. As seen in

Figure 7 (a), MBC in the control shrimp exceeded 7 log CFU/g by Day 16, whereas 2%PT+1%AG treated shrimp showed only 5.8 log CFU/g at the same time. Similarly for PBC,

Figure 7 (b) illustrates counts reaching over 8 log CFU/g in the control versus 6.3 log CFU/g in treated shrimp after 16 days of storage. The observed reduction in bacterial growth with 2%PT+1%AG treatment can be attributed to the antimicrobial action of phlorotannins and alginate. Previous studies have reported that phlorotannin-rich extracts are effective against both gram-positive and gram-negative seafood spoilage bacteria [

35]. This antibiotic property likely helped suppress the proliferation of MBC and PBC in shrimp muscle throughout iced storage. Additionally, the alginate component may have formed a protective coating on treated shrimp, presenting a physical barrier against microbial attachment and entry [

30]. Overall, through synergistic antimicrobial effects, the combination of phlorotannins and alginate very effectively controlled the outgrowth of mesophilic and psychrotrophic bacteria, thereby maintaining better microbial quality of Pacific white shrimp compared to the untreated control during 16 days of chilled storage.

3.5.4. Sensory Evaluation

Changes in sensory scores of Pacific white shrimp treated without and with 2%PT+1%AG during 16 days of iced storage are shown in

Figure 8. Overall, the sensory scores of all treatments declined throughout storage, with the fastest rate of decline observed in the untreated control shrimp. Initially at Day 0, there were no significant differences (P>0.05) between treatments and scores were within the “high quality” range for all shrimp. After 8 days of storage, scores of the control dropped to 4.71, reaching the unacceptable level below 5. Shrimp treated with 2%PT+1%AG maintained acceptable scores above 5 until Day 12. On Day 12, untreated shrimp exhibited noticeable quality deterioration through unpleasant odor and soft texture. Meanwhile, treated shrimp still appeared fresh with acceptable aroma and firmness. The highest sensory scores were observed for shrimp treated with 2%PT+1%AG, maintaining quality until Day 12. These sensory results coincided well with slower melanosis development, lower microbial growth and reduced biochemical changes observed in 2%PT+1%AG treated shrimp. Therefore, 2%PT+1%AG treatment extended the shelf-life of Pacific white shrimp by 4 additional days compared to the control, likely attributable to antioxidant and antimicrobial effects prolonging freshness.

4. Conclusions

The results of this study demonstrated the potential of a phlorotannin-alginate rich extract from the brown seaweed Nizimuddinia zanardinii to inhibit melanosis and preserve the quality of Pacific white shrimp during ice storage. The extract exhibited a high concentration of phlorotannins as well as potent antioxidant and metal chelating activities. It was found to effectively inhibit the enzymatic activity of polyphenol oxidase (PPO) from shrimp in a concentration-dependent manner. A synergistic combination of 1% phlorotannins, 0.5% alginate and 0.5% sodium metabisulfite provided over 84% PPO inhibition, comparable to the standard preservative ascorbic acid. When applied as a post-harvest treatment for shrimp, the phlorotannin-alginate-sodium metabisulfite blend was successful in delaying melanosis development and maintained lower melanosis scores throughout 16 days of chilled storage compared to the untreated control. It also retarded the microbial, chemical and lipid oxidation spoilage of shrimp, as evidenced through suppressed pH, TVB-N, TBA and peroxide values. Sensory analysis further confirmed the better retention of visual appeal, odor and texture attributes among treated shrimp. In conclusion, the phlorotannin-alginate rich extract demonstrated great promise as an effective natural alternative for controlling melanosis and enhancing the shelf-life of Pacific white shrimp during ice storage. With further optimization, this approach can potentially be incorporated into industrial processing for sustainable shrimp preservation under iced storage conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Sh. and S.B.; methodology, S.Sh.; software, S.Sh.; validation, S.Sh. and S.B.; formal analysis, S.Sh.; investigation, S.Sh. and S.B..; resources, S.Sh.; data curation, S.Sh.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Sh.; writing—review and editing, S.Sh. and S.B.; visualization, S.Sh.; supervision, S.Sh.; project administration, S.Sh.; funding acquisition, S.Sh. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Grant (number 99005193) funded by the Iran National Science Foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not Applicable.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the employees of the Central Laboratory of Chabahar Maritime University for their invaluable contributions to this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sharifian S, Shabanpour B, Taheri A, Kordjazi M. Effect of phlorotannins on melanosis and quality changes of Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) during iced storage. Food Chem 298:124980 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Yan Y, Zhang Y, Yang R, Zhao W. Combined effect of slightly acidic electrolyzed water and ascorbic acid to improve quality of whole chilled freshwater prawn (Macrobrachium rosenbergii). Food Control 108:106820 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Shiekh KH, Benjakul S, Sae-leaw T. Effect of Chamuang (Garcinia cowa Roxb.) leaf extract on inhibition of melanosis and quality changes of Pacific white shrimp during refrigerated storage. Food Chem 270(1):554–561 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Khan F, Jeong G-J, Khan MSA, Tabassum N, Kim Y-M. Seaweed-Derived Phlorotannins: A Review of Multiple Biological Roles and Action Mechanisms. Mar Drugs 20(6):384 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Jayakody MM, Vanniarachchy MPG, Wijesekara I. Seaweed derived alginate, agar, and carrageenan based edible coatings and films for the food industry: a review. Food Measure 16:1195–1227 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Zhu D, Guo R, Li W, Song J, Cheng F. Improved postharvest preservation effects of Pholiota nameko mushroom by sodium alginate–based edible composite coating. Food Bioprocess Technol 12:587–598 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Shams M, Afsharzadeh S, Balali Gh. Taxonomic Study of Six Sargassum Species (Sargassaceae, Fucales) with Compressed Primary Branches in the Persian Gulf and Oman Sea Including S. binderi Sonder New Record Species for Algal Flora, Iran. J Sci Islamic Repub Iran 26(1):7–16 (2015).

- Rostami Z, Tabarsa M, You S, Rezaei M. Relationship between molecular weights and biological properties of alginates extracted under different methods from Colpomenia peregrina. Process Biochem 58:289–297 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Wong SP, Leong LP, Koh JHW. Antioxidant activities of aqueous extracts of selected plants. Food Chem 99(4):775–783 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Nirmal NP, Benjakul S. Effect of ferulic acid on inhibition of polyphenoloxidase and quality changes of Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) during iced storage. Food Chem 116(1):323–331 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Kılınç B, Çaklı Ş, Kışla D. Quality changes of sardine (Sardina pilchardus W., 1792) during frozen storage. E.U. J Fish Aqua Scien 20:139–146 (2003).

- Bligh E, Dyer W. A rapid method of total extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol 37:911–917 (1959).

- AOAC. Official methods of analysis of the Association of the Official Analysis Chemists (17th ed.). Washington, DC: Association of Official Analytical Chemists (2000).

- Benjakul S, Bauer F. Biochemical and physicochemical changes in catfish (Silurus glanis Linne) muscle as influenced by different freeze-thaw cycles. Food Chem 77:207–217 (2001). [CrossRef]

- Li M, Wang W, Fang W, Li Y. Inhibitory effects of chitosan coating combined with organic acids on Listeria monocytogenes in refrigerated ready-to-eat shrimps. J Food Prot 76(8):1377–1383 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Puspita M, Deniel M, Widowati I. Total phenolic content and biological activities of enzymatic extraction from Sargassum muticum (Yendo) Fensholt. J Appl Phycol 29:2521–2537 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Tierney MS, Smyth TJ, Rai DK, Soler-Vila A, Croft AK, Brunton N. Enrichment of polyphenol contents and antioxidant activity of Irish brown macroalgae using food-friendly techniques based on polarity and molecular size. Food Chem 139(1–4):753–761 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Fu X, Duan D, Liu X, Xu J, Gao X. Extraction and identification of phlorotannins from the brown alga, Sargassum fusiforme (Harvey) Setchell. Mar Drugs 15(2):49 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Almeida B, Barroso S, Ferreira ASD, Adão P, Mendes S, Gil MM. Seasonal Evaluation of Phlorotannin-Enriched Extracts from Brown Macroalgae Fucus spiralis. Molecules 26(14):4287 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Kirke DA, Rai DK, Smyth TJ, Stengel DB. An assessment of temporal variation in the low molecular weight phlorotannin profiles in four intertidal brown macroalgae. Algal Res 41:101550 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Wang T, Jónsdóttir R, Ólafsdóttir G. Total phenolic compounds, radical scavenging and metal chelation of extracts from Icelandic seaweeds. Food Chem 116(1):240–248 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Le Lann K, Jégou C, Stiger-Pouvreau V. Effect of different conditioning treatments on total phenolic content and antioxidant activities in two Sargassacean species: Comparison of the frondose Sargassum muticum (Yendo) Fensholt and the cylindrical Bifurcaria bifurcata R. Ross. Phycol Res 56(4):238–245 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Mhadhebi L, Chaieb K, Bouraoui A. Evaluation of antimicrobial activity of organic fractions of six marine algae from Tunisian Mediterranean coasts. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci 4(1):534–537 (2012).

- Li YX, Wijesekara I, Li Y, Kim SK. Phlorotannins as bioactive agents from brown algae. Process Biochem 46(12):2219-2224 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Borazjani NJ, Tabarsa M, You S, Rezaei M. Effects of extraction methods on molecular characteristics, antioxidant properties and immunomodulation of alginates from Sargassum angustifolium. Int J Biol Macromol 101:703–711 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Fertah M, Belfkira A, Dahmane EM, Taourirte M, Brouillette F. Extraction and characterization of sodium alginate from Moroccan Laminaria digitata brown seaweed. Arab J Chem 10:S3707 –S3714 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Kumar S, Sahoo D. A comprehensive analysis of alginate content and biochemical composition of leftover pulp from brown seaweed Sargassum wightii. Algal Res 23:233–239 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Hu T, Liu D, Chen Y, Wu J, Wang S. Antioxidant activity of sulfated polysaccharide fractions extracted from Undaria pinnitafida in vitro. Int J Biol Macromol 46(2):193–198 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Kurihara H, Kujira K. Phlorotannins derived from the brown alga Colpomenia bullosa as tyrosinase inhibitors. Nat Prod Commun 16(7) (2021). [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Yang Z, Li J. Shelf-life extension of Pacific white shrimp using algae extracts during refrigerated storage. J Sci Food Agric 97(1):291–298 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Xu L, Gao L, Meng J, Chang M. Browning inhibition and postharvest quality of button mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus) treated with alginate and ascorbic acid edible coating. Int Food Res J 29(1):106–115 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Nazoori F, Poraziz S, Mirdehghan SH, Esmailizadeh M, ZamaniBahramabadi E. Improving shelf life of strawberry through application of sodium alginate and ascorbic acid coatings. Int J Hortic Sci Technol 7(3):279–293 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Afrin F, Ahsan T, Mondal MN, Rasul MG, Afrin M, Silva AA, Yuan C, Shah AKMA. Evaluation of antioxidant and antibacterial activities of some selected seaweeds from Saint Martin’s Island of Bangladesh. Food Chem Advanc 3:100393 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Dou L, Li B, Zhang K, Chu X, Hou H. Physical properties and antioxidant activity of gelatin-sodium alginate edible films with tea polyphenols. Int J Biol Macromol 118:1377–1383 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Besednova NN, Andryukov BG, Zaporozhets TS, Kryzhanovsky SP, Kuznetsova TA, Fedyanina LN, Makarenkova ID, Zvyagintseva TN. Algae Polyphenolic Compounds and Modern Antibacterial Strategies: Current Achievements and Immediate Prospects. Biomedicines 8(9):342 (2020). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).