Submitted:

26 August 2025

Posted:

27 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

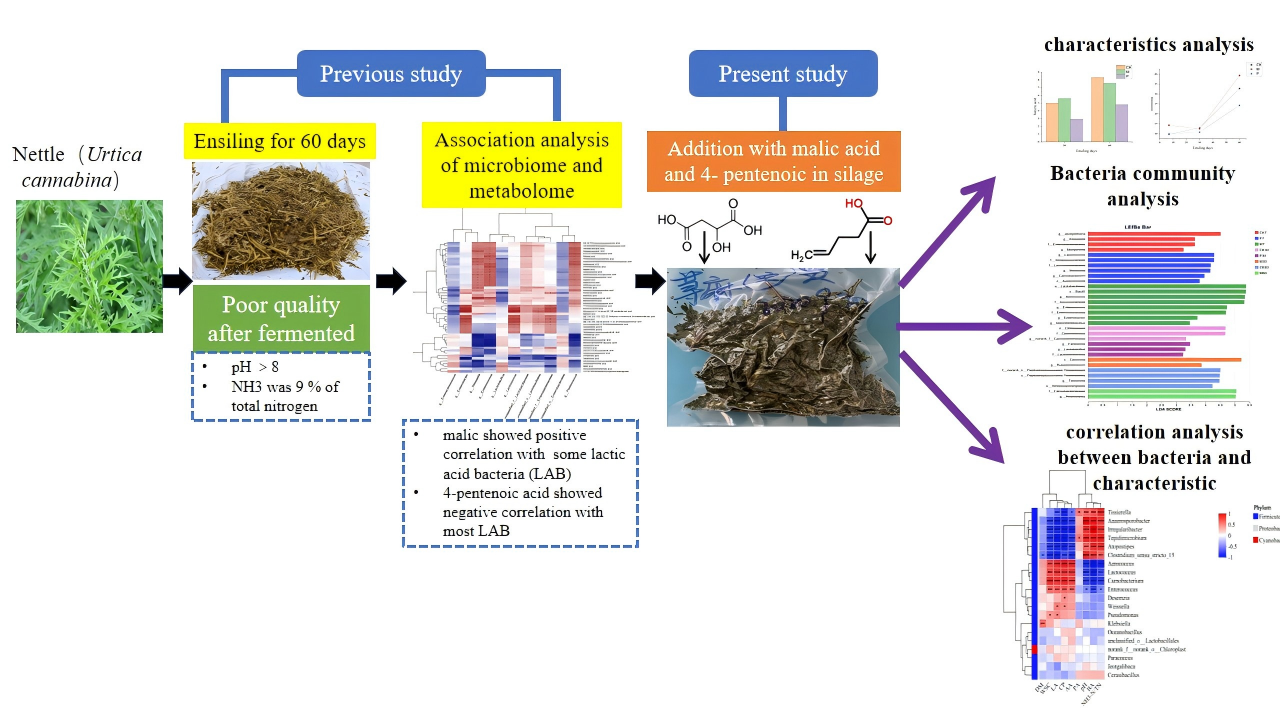

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Silage Prepartion

2.2. Characteristics Analysis of Nettle Silage

2.3. Sequencing Analysis of Bacterial Community in Nettle Silage

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effect of 4-Pentenoic Acid and Malic on Characteristics of Nettle Silage

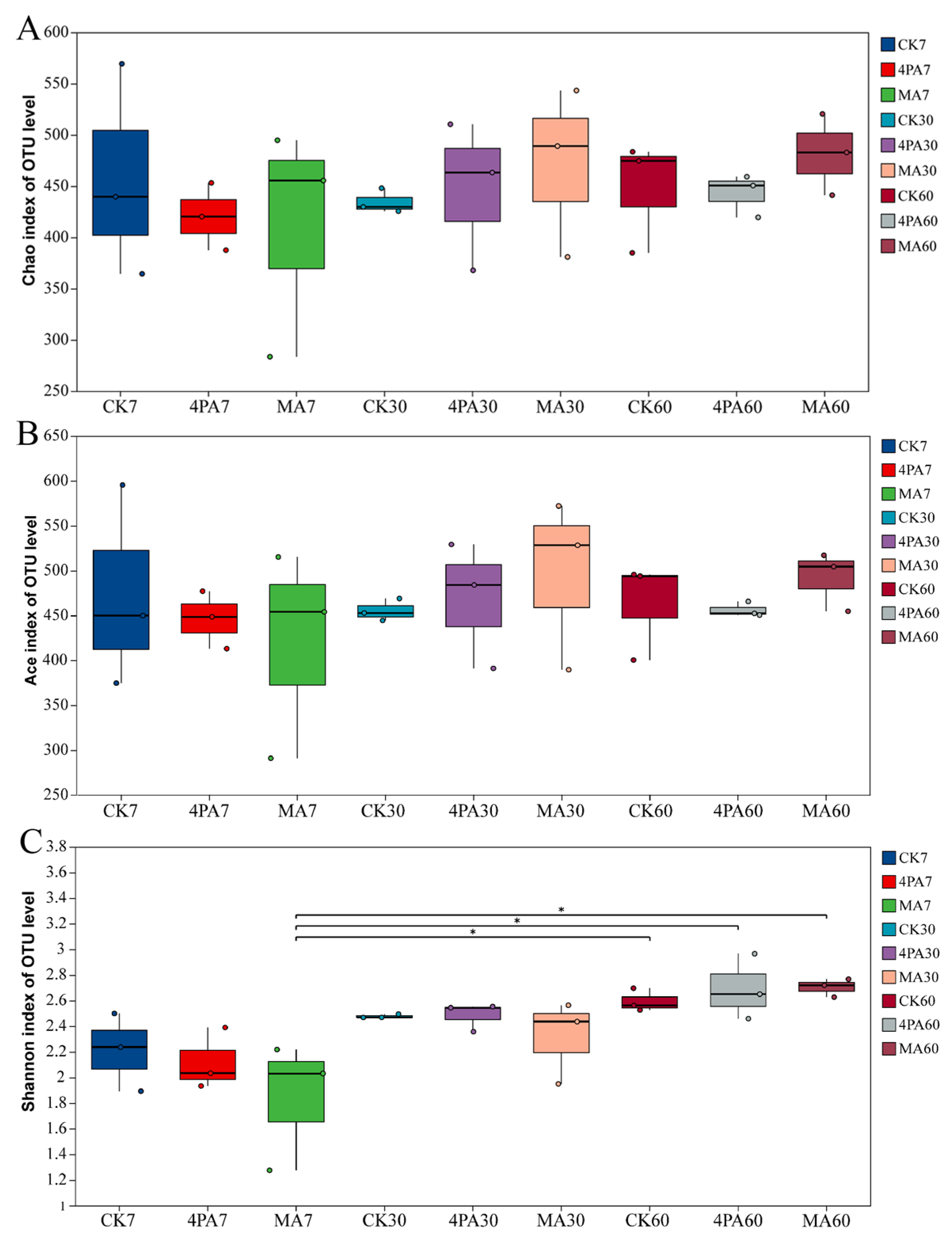

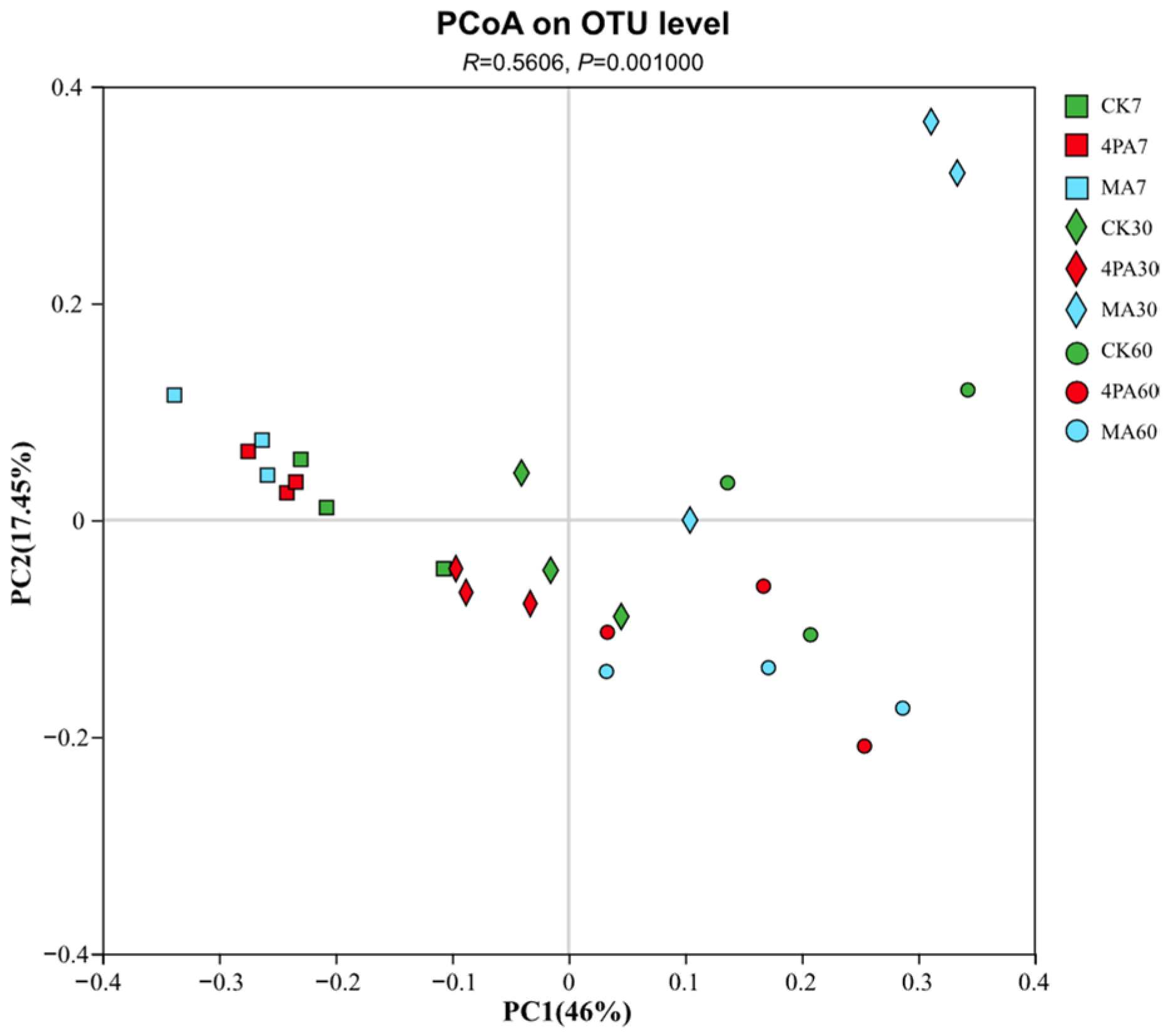

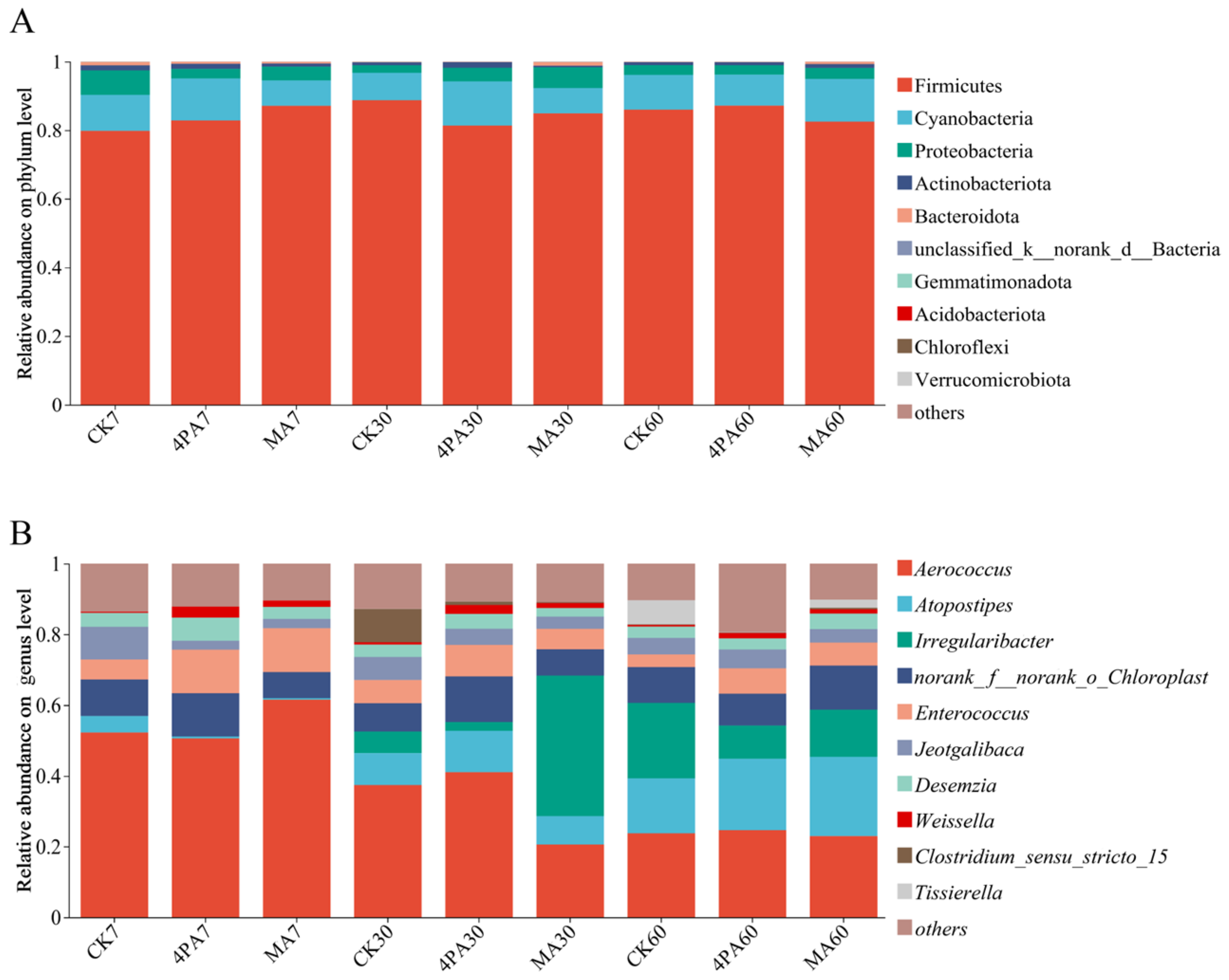

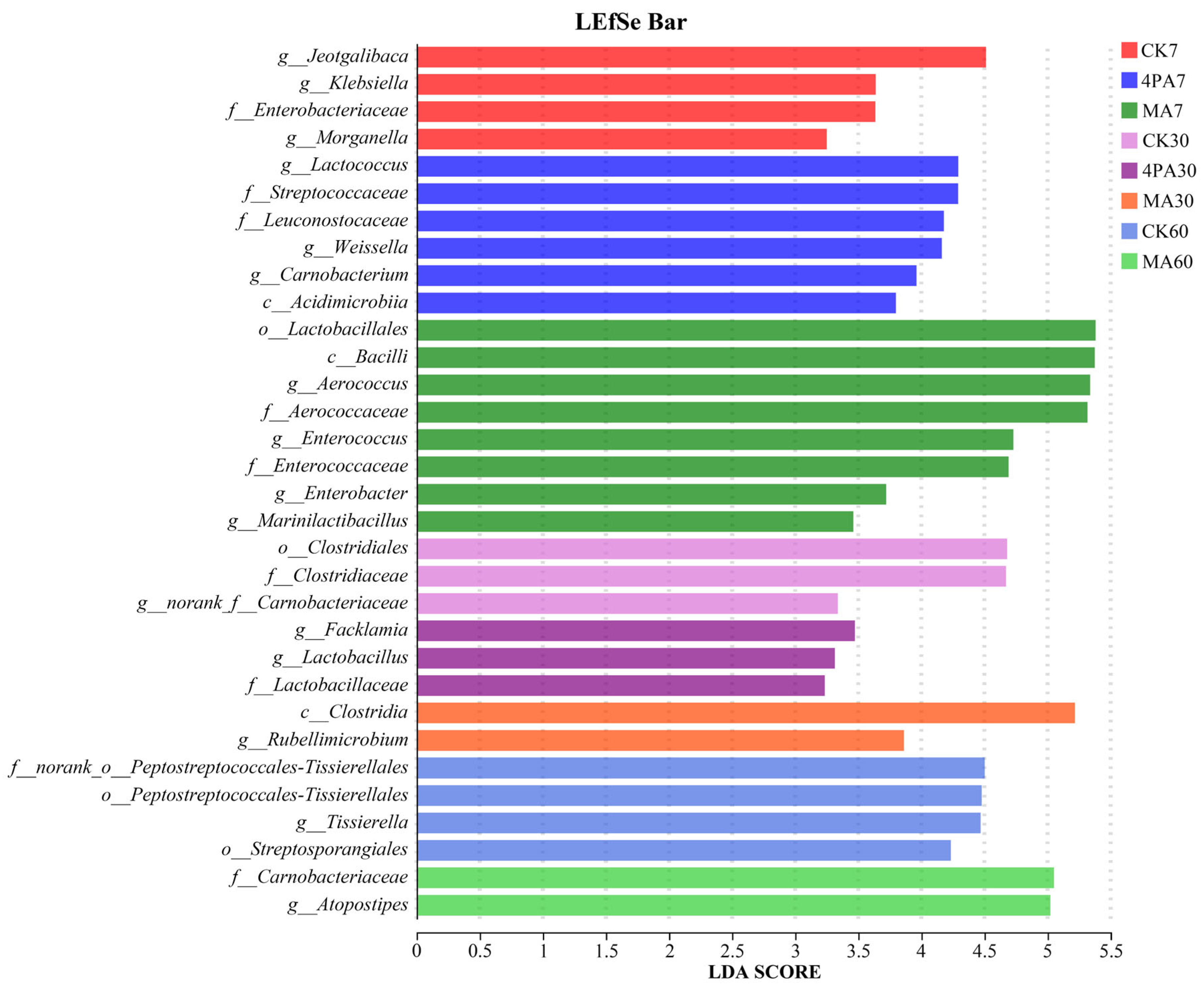

3.2. Effect of 4-Pentenoic Acid and Malic on Bacteria Community of Nettle Silage

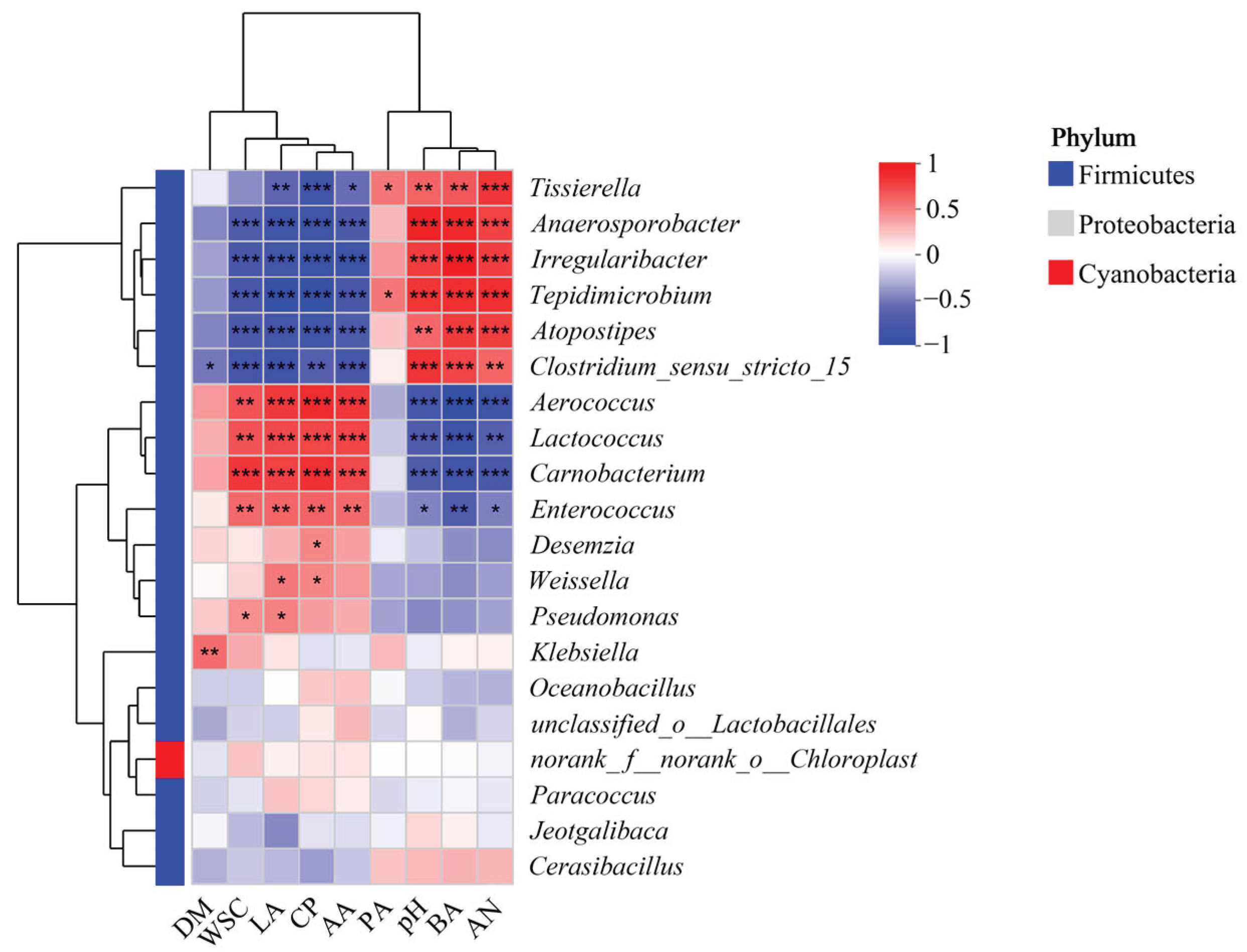

3.3. Correlation Analysis Between Bacteria Community and Fermentation Characteristics in Nettle Silage

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of 4-Pentenoic Acid and Malic on Characteristics of Nettle Silage

4.2. Effect of 4-Pentenoic Acid and Malic On Bacteria Community of Nettle Silage

4.3. Correlation Analysis Between Bacteria Community and Fermentation Characteristics in Nettle Silage

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Data Availability Statement

Competing interests

Abbreviations

| AA | Acetic acid |

| AN | Ammonia-N |

| BA | Butyric acid |

| CP | Crude protein |

| DM | Dry matter |

| LA | Lactic acid |

| LAB | Lactic acid bacteria |

| MA | malic acid |

| PA | Propionic acid |

| WSC | Water-soluble carbohydrate |

| 4PA | 4-pentenoic acid |

References

- Ding, Z. Z.; Xiao, C.F.; Xu, Y. Y.; Lu, W. W.; Zhu, L. H. . Research progress on the application of alternative unconventional feed ingredients in poultry breeding. Acta Agric. Shanghai. 2024, 40, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhusal, K. K.; Magar, S. K.; Thapa, R.; Lamsal, A.; Bhandari, S.; Maharjan, R.; Shrestha, S.; Shrestha, J. . Nutritional and pharmacological importance of stinging nettle (Urtica dioica L.): A review. Heliyon. 2022, 8, e09717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R. Z.; Chen, Y. C.; Ma, C. H.; Chai, Y. X.; Jia, S. A.; Zhang, F. F. Potential Factors Causing Failure of Whole Plant Nettle (Urtica Cannabina) Silages. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1113050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q. Z.; Hou, Z. P.; Gao, S.; Li, Z. C.; Wei, Z. S.; Wu, D. Q. . Substitution of fresh forage ramie for alfalfa hay in diets affects production performance, milk composition, and serum parameters of dairy cows. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2019, 51, 469–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirsaiidi Farahani, M.; Hosseinian, S. A. . Effects of dietary stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) on hormone stress and selected serum biochemical parameters of broilers subjected to chronic heat stress. Vet. Med. Sci. 2022, 8, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirgozliev, V. R.; Kljak, K.; Whiting, I. M.; Mansbridge, S. C.; Atanasov, A.G.; Enchev, S. B.; Tukša, M.; Rose, S. P. . Dietary stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) improves carotenoids content in laying hen egg yolk. Br. Poult. Sci. 2025, 66, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Toledo, G. S. P.; da Silva, L. P.; de Quadros, A. R. B.; Retore, M.; Araújo, I. G.; Brum, H. S.; Melchior, R. . Productive performance of rabbits fed with diets containing ramie (Boehmeria nivea) hay in substitution to alfalfa (Medicago sativa) hay. Verona, Italy: In 9th World Rabbit Congress 2008, 827–830.

- Liu, J. Y.; Zhao, M.; Hao, J. F.; Yan, X. Q.; Fu, Z. H.; Zhu, N.; Jia, Y. S.; Wang Z., J.; Ge, G. T. . Effects of temperature and lactic acid Bacteria additives on the quality and microbial community of wilted alfalfa silage. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S. A.; Chai, Y. X.; Yang, H. J. , Zhang, F. F.; Ma, C. H.. Isolation and identification of dominant lactic acid bacteria from Urtica cannabina silage. Pratac. Sci. 2023, 40, 1410–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y. X.; Jia, S. A.; Zhang, T.; Li, X.; Chen, Y. C.; Huang, R. Z.; Zhang, F. F. . Effects of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum on Silage Quality of Urtica cannabina and Rumen Degradation Characteristics of Sheep. Acta Agrestia Sin. 2024, 32, 2283–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R. Z.; Chai, Y. X.; Li, S. M.; Chen, Y. C.; Jia, S. A.; Ma, C. H.; Zhang, F. F. . Involvement of 4-pentenoic acid in causing quality deterioration of nettle silage: study of antibacterial mechanism. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e0266724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, P.; Henderson, A. R. Determination of Water-Soluble Carbohydrates in Grass. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1964, 15, 395–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherburn, M. W. Phenol-Hypochlorite Reaction for Determination of Ammonia. Anal. Chem. 1967, 39, 971–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. C.; Li, S. M.; Sun, Y. C.; Chai, Y. X.; Jia, S. A.; Ma, C. H.; Zhang, F. F. The Effects of Lactococcus garvieae and Pediococcus pentosaceus on the Characteristics and Microbial Community of Urtica cannabina Silage. Microorganisms. 2025, 13, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Wang, S. R.; Zhao, J.; Dong, Z. H.; Li, J. F.; Nazar, M.; Shao, T. Microbial Diversity and Fermentation Profile of Red Clover Silage Inoculated with Reconstituted Indigenous and Exogenous Epiphytic Microbiota. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 314, 123606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Feng, Y.; Pei, J.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Fu, S.; Zheng, Y.; Li, Z.; Peng, Z. Effects of Lactobacillus Plantarum Additive and Temperature on the Ensiling T Quality and Microbial Community Dynamics of Cauliflower Leaf Silages. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 307, 123238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladosu, Y.; Rafii, M. Y.; Abdullah, N.; Magaji, U.; Hussin, G.; Ramli, A.; Miah, G. Fermentation Quality and Additives: A Case of Rice Straw Silage. Biomed Res. Int. 2016, 7985167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driehuis, F.; Elferink, S. The Impact of the Quality of Silage on Animal Health and Food Safety: A Review. Vet. Q. 2000, 22, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huhtanen, C. N.; Trenchard, H.; Milnes-McCaffery, L. Inhibition of Clostridium-Botulinum in Comminuted Bacon by Short-Chain Alkynoic and Alkenoic Acids and Esters. J. Food Prot. 1985, 48, 570–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Q. X.; Shi, W. J.; Zhou, J. Addition of Organic Acids and Lactobacillus Acidophilus to the Leguminous Forage Chamaecrista Rotundifolia Improved the Quality and Decreased Harmful Bacteria of the Silage. Animals. 2022, 12, 2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, W. C.; Ding, Z. T.; Li, F. H.; Xu, D. M.; Bai, J.; Muhammad, I.; Zhang, Y. X.; Zhao, L. S.; Guo, X. S. Effects of Malic or Citric Acid on the Fermentation Quality, Proteolysis and Lipolysis of Alfalfa Silage Ensiled at Two Dry Matter Contents. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 106, 988–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, L. D.; Zhang, Q.; Zi, X. J.; Lv, R. L.; Tang, J.; Zhou, H. L. Impacts of Citric Acid and Malic Acid on Fermentation Quality and Bacterial Community of Cassava Foliage Silage. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 595622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, P.; Petrov, K. Lactic Acid Fermentation of Cereals and Pseudocereals: Ancient Nutritional Biotechnologies with Modern Applications. Nutrients. 2020, 12, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. L.; Yang, H. J.; Huang, R. Z.; Wang, X. Z.; Ma, C. H.; Zhang, F. F. Effects of Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum and Lactiplantibacillus Brevis on Fermentation, Aerobic Stability, and the Bacterial Community of Paper Mulberry Silage. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1063914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Q.; Li, F. H.; Xie, D. M.; Zhang, B. B.; Kharazian, Z. A.; Guo, X. S. Effects of Bacteriocin-Producing Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum on Fermentation, Dynamics of Bacterial Community, and Their Functional Shifts of Alfalfa Silage with Different Dry Matters. Fermentation. 2022, 8, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, H.; Li, J.; Dong, Z.; Wang, S.; Shao, T. Relationships between Microbial Community, Functional Profile and Fermentation Quality during Ensiling of Hybrid Pennisetum. J. Anim. Feed Sci. 2023, 32, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Venegas, G.; Gomez-Mora, J. A.; Meraz-Rodriguez, M. A.; Flores-Sanchez, M. A.; Ortiz-Miranda, L. F. Effect of Flavonoids on Antimicrobial Activity of Microorganisms Present in Dental Plaque. Heliyon. 2019, 5, e03013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, L.; Xie, Z.; Hu, L. X.; Chen, G. H.; Zhang, Z. F. Cellulase Interacts with Lactobacillus Plantarum to Affect Chemical Composition, Bacterial Communities, and Aerobic Stability in Mixed Silage of High-Moisture Amaranth and Rice Straw. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 315, 123775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H. C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z. C.; Hu, Z. Y.; Guo, Y. Q.; Deng, M.; Liu, G. B.; Sun, B. L. Effects of Malic Acid and Sucrose on the Fermentation Parameters, CNCPS Nitrogen Fractions, and Bacterial Community of Moringa Oleifera Leaves Silage. Microorganisms. 2021, 9, 2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maspolim, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, C. H.; Xiao, K. K.; Ng, W. J. The Effect of pH on Solubilization of Organic Matter and Microbial Community Structures in Sludge Fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 190, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driehuis, F.; Elferink, S.O.; Van Wikselaar, P.G. . Fermentation characteristics and aerobic stability of grass silage inoculated with Lactobacillus buchneri, with or without homofermentative lactic acid bacteria. Grass Forage Sci. 2001, 56, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X,; Ai, L. Z.; Xia, Y. J.; Song, X.; Zhang, H.; Ni, B.; Yang, D. J. Research progress of safety, probiotic potential and functional properties of Weissella confusa. Ind. Microbiol. 2022, 52, 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L. N.; Wang, X. K.; Chen, H. L.; Li, X. M.; Xiong, Y.; Zhou, H. Z.; Xu, G.; Yang, F. Y.; Ni, K. K. . Exploring the fermentation quality, bacterial community and metabolites of alfalfa ensiled with mugwort residues and Lactiplantibacillus pentosus. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2023, 10, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Index | Time/day | Groups | SEM | pvalue | ||

| CK | MA | 4PA | ||||

| DM (% fresh weight) | 7 | 37.72 | 37.23 | 36.58 | 1.245 | 0.675 |

| 30 | 35.45 b | 36.66 a | 35.39 b | 0.038 | 0.027 | |

| 60 | 36.33 | 36.78 | 35.08 | 0.871 | 0.211 | |

| CP% DM | 7 | 16.23 a | 15.89 b | 16.32 a | 0.039 | <0.001 |

| 30 | 15.27 c | 15.60 b | 15.96 a | 0.067 | <0.001 | |

| 60 | 13.27 c | 13.72 b | 14.83 a | 0.062 | <0.001 | |

| WSC% DM | 7 | 2.92 | 3.30 | 2.95 | 0.230 | 0.263 |

| 30 | 0.68 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.045 | 0.606 | |

| 60 | 0.69 | 0.74 | 0.68 | 0.041 | 0.386 | |

| pH | 7 | 7.65 c | 7.80 b | 7.98 a | 0.024 | <0.001 |

| 30 | 8.35 a | 8.15 b | 8.11 b | 0.064 | 0.019 | |

| 60 | 8.47 a | 8.24 a | 8.10 b | 0.096 | 0.023 | |

| LA/(g·kg−1 DM) | 7 | 2.68 b | 4.21 a | 3.86 b | 0.425 | 0.026 |

| 30 | 0.016 c | 0.17 b | 0.40 a | 0.048 | <0.001 | |

| 60 | ND | ND | ND | - | - | |

| AA/(g·kg−1 DM) | 7 | 1.74 | 1.74 | 1.77 | 0.251 | 0.990 |

| 30 | 0.94 b | 0.93 b | 1.57 a | 0.070 | <0.001 | |

| 60 | 0.63 b | 0.50 b | 1.37 a | 0.166 | 0.004 | |

| PA/(g·kg−1 DM) | 7 | 0.054 | 0.068 | 0.076 | 0.016 | 0.413 |

| 30 | 0.082 | 0.078 | 0.050 | 0.019 | 0.215 | |

| 60 | 0.19 a | 0.083 b | 0.065 b | 0.026 | 0.005 | |

| BA/(g·kg−1 DM) | 7 | ND | ND | ND | - | - |

| 30 | 4.99 a | 5.59 a | 2.92 b | 0.287 | <0.001 | |

| 60 | 8.31 a | 7.56 a | 4.79 b | 0.367 | <0.001 | |

| AN (% of TN) DM | 7 | 9.81 | 14.30 | 9.94 | 2.280 | 0.160 |

| 30 | 12.90 a | 12.47 a | 10.86 b | 0.190 | <0.001 | |

| 60 | 32.79 b | 39.33 a | 24.28 c | 1.150 | <0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).