Submitted:

23 August 2025

Posted:

27 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

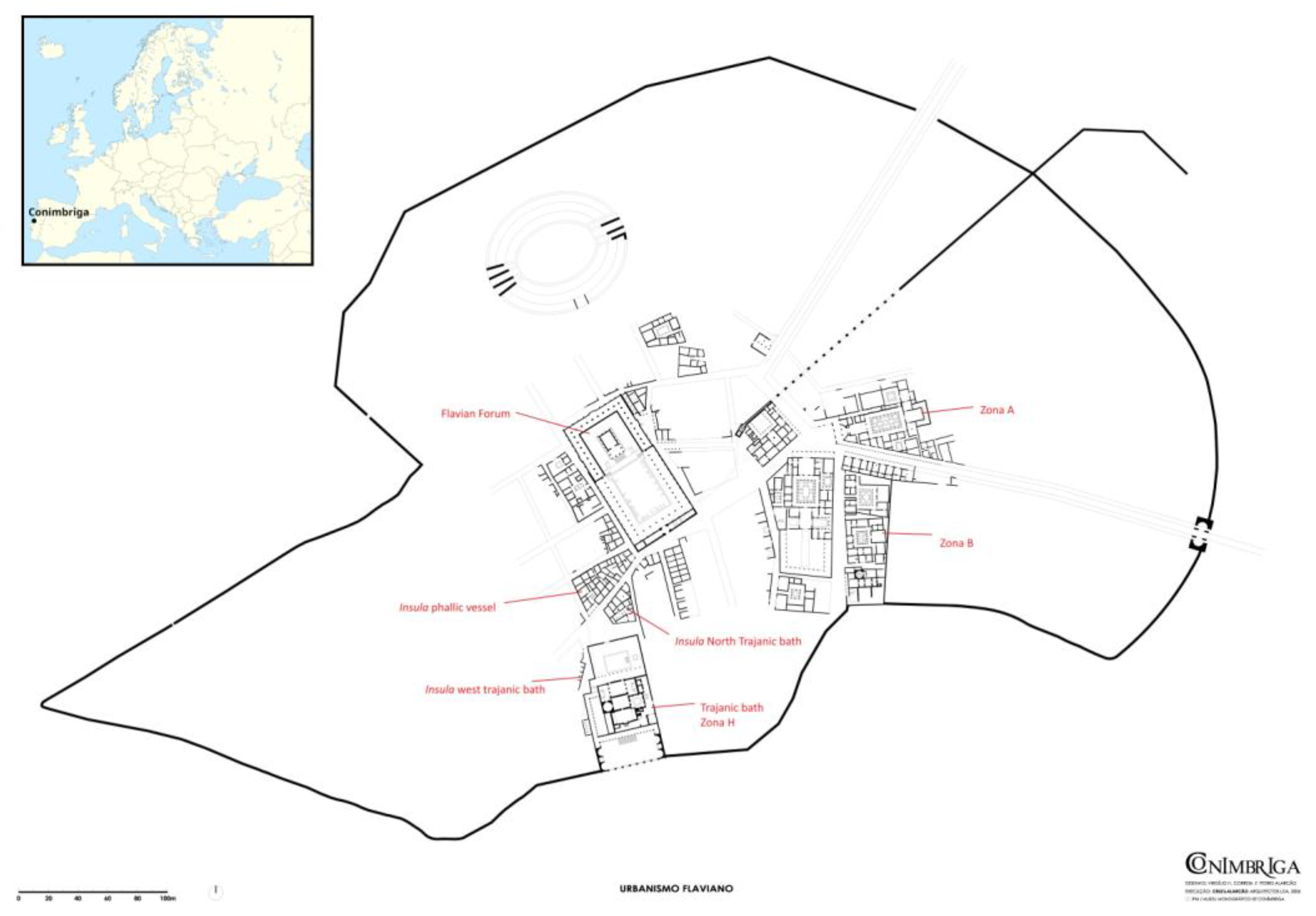

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

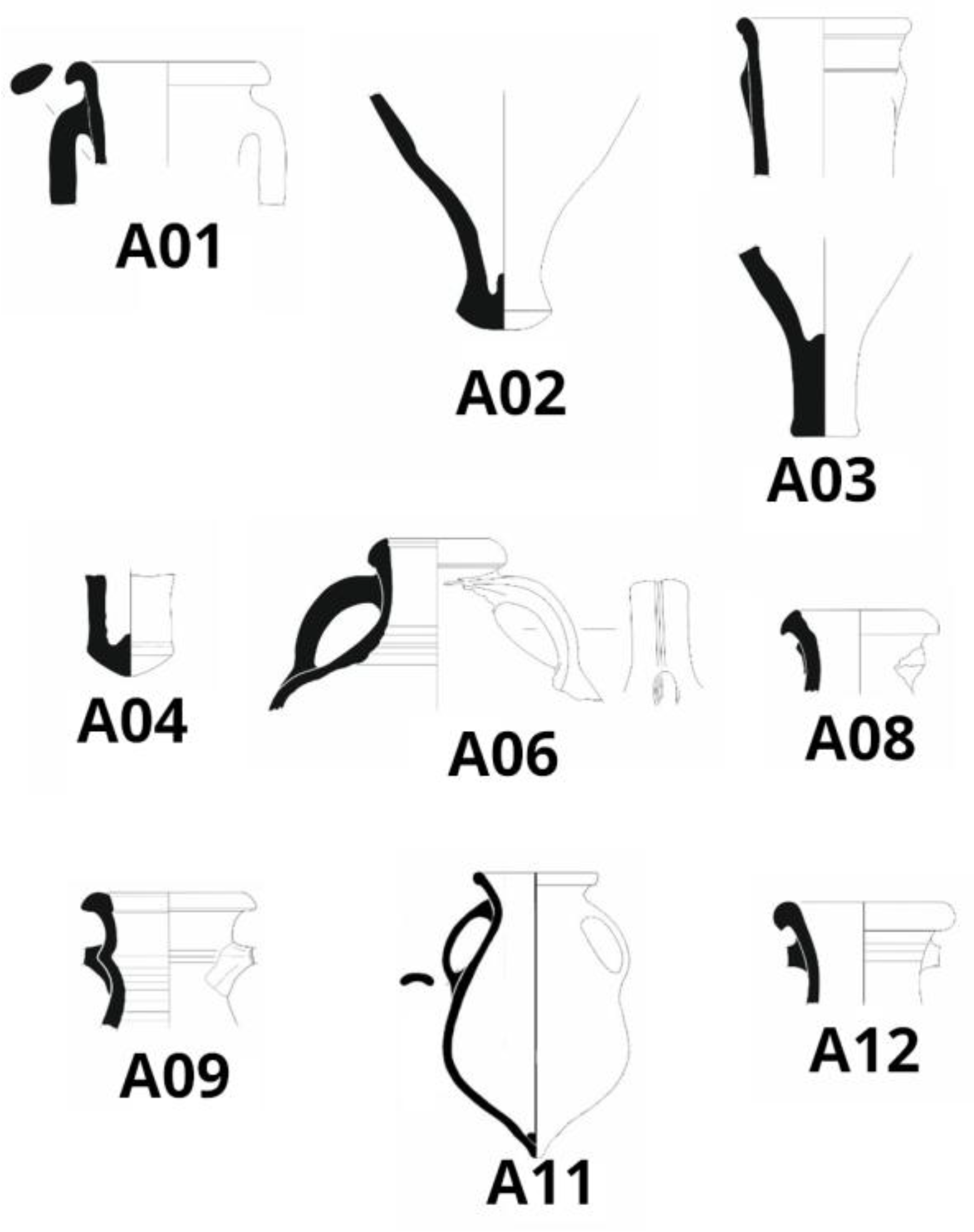

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

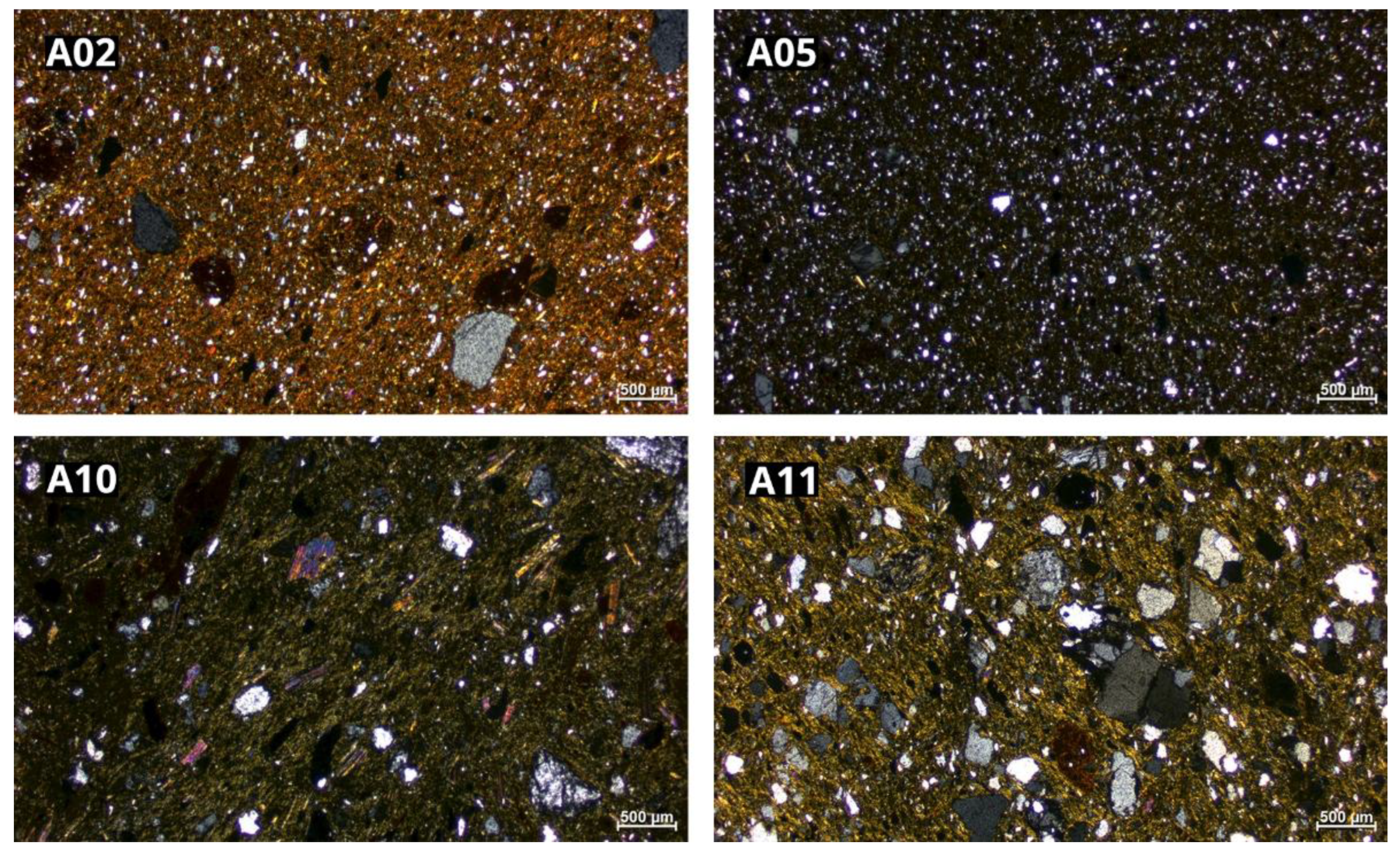

2.2.1. Optical Microscopy

2.2.2. X-Ray Diffraction

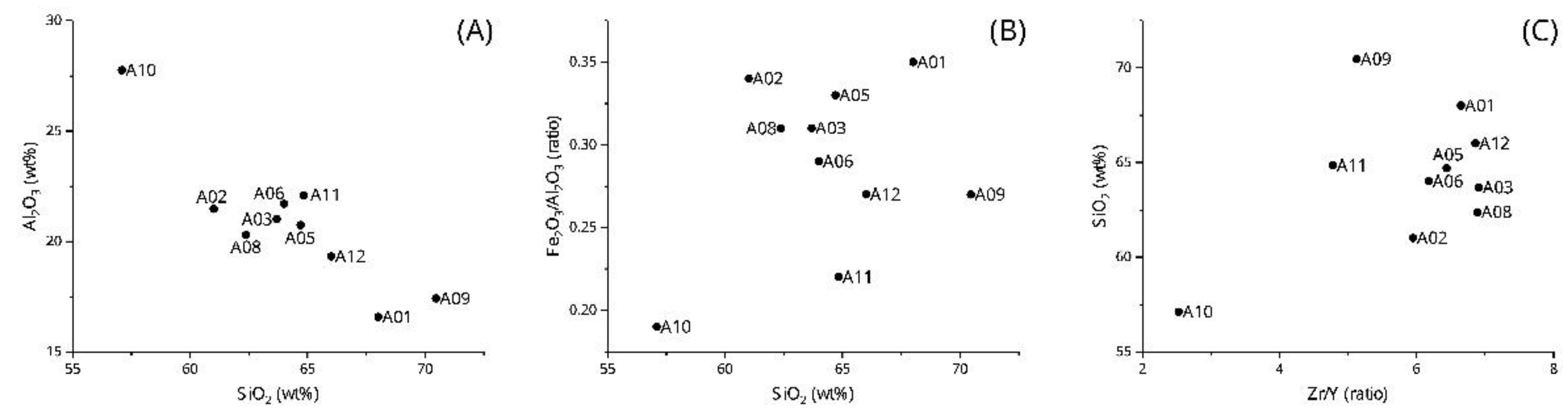

2.2.3. X-Ray Fluorescence

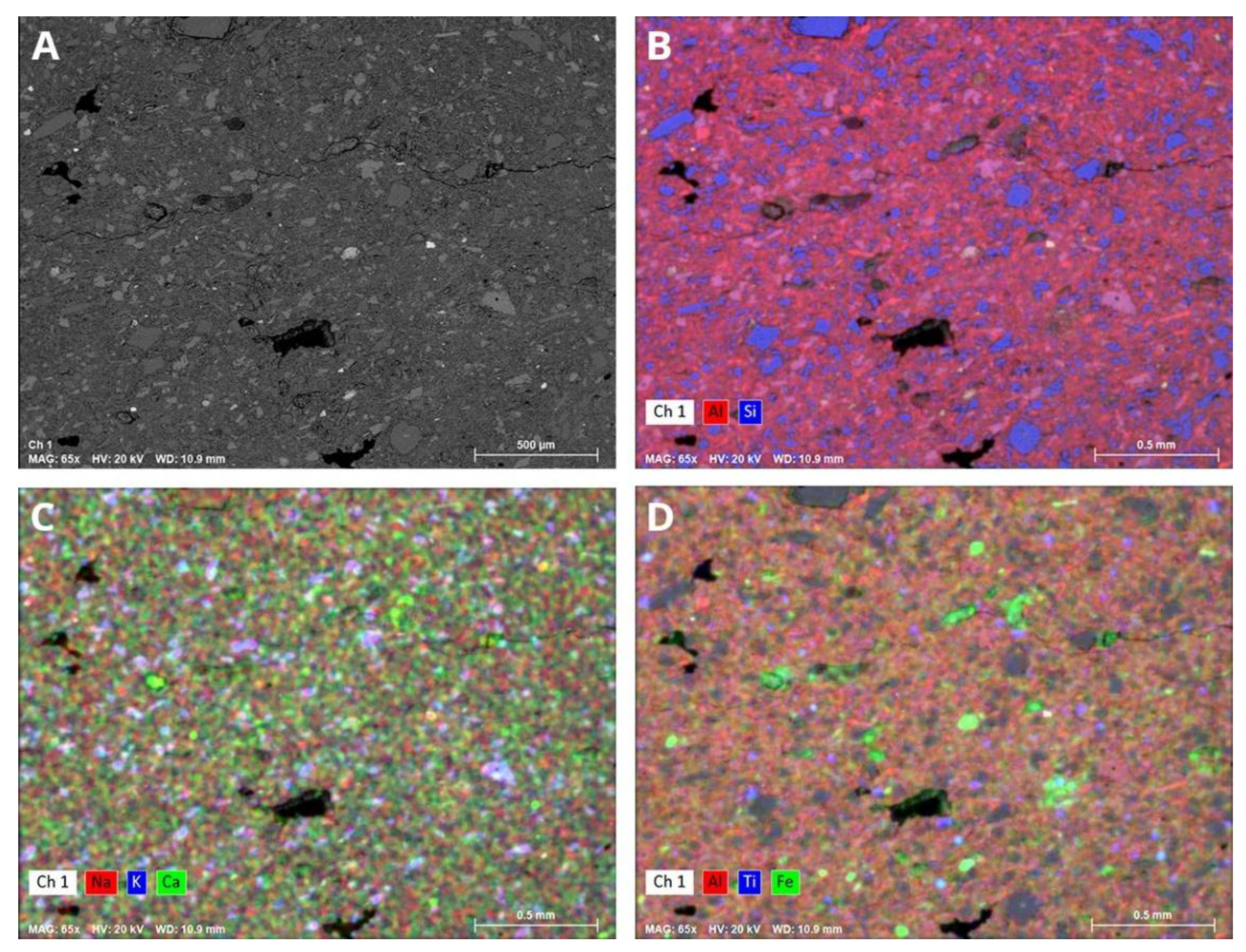

2.2.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy-Dispersive Spectroscopy

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Technological Analysis and Raw Material Characterization

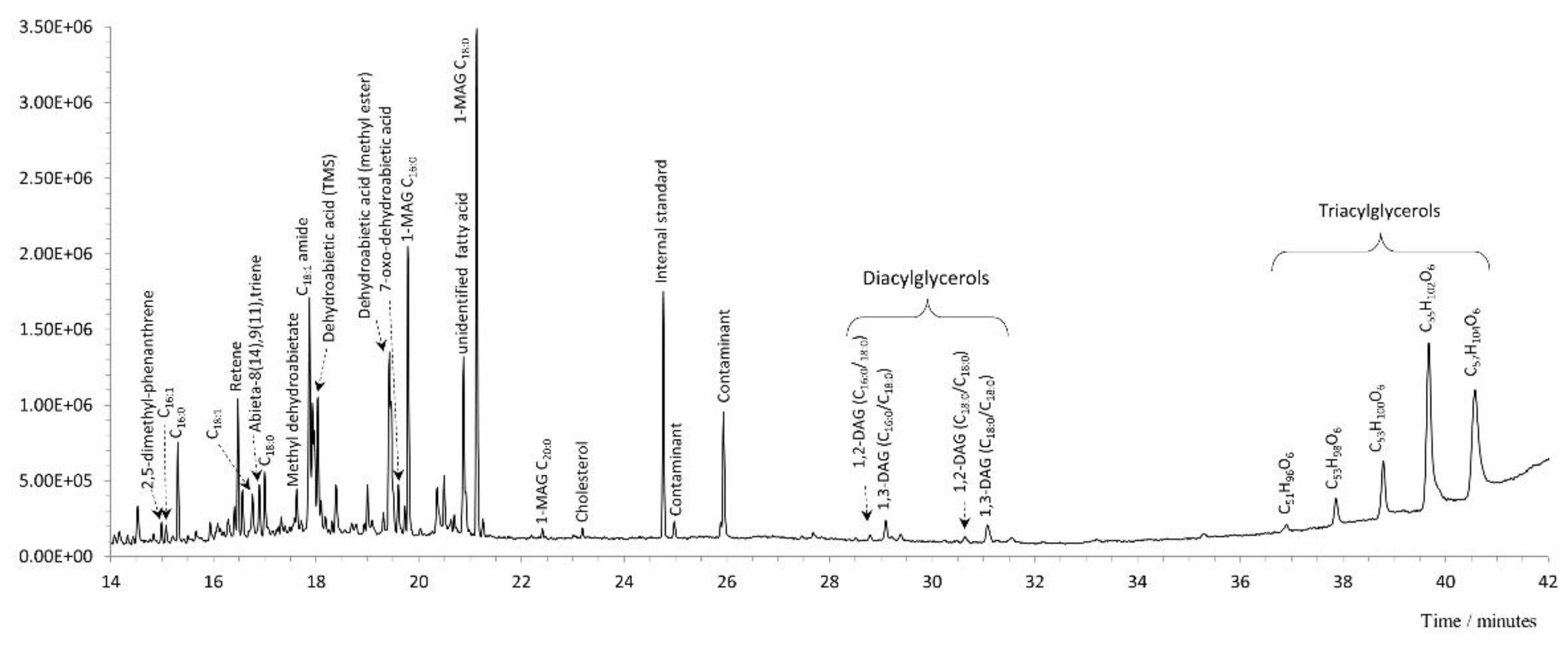

3.2. Amphora Functionality and Use: Evidence from Organic and Ceramic Data

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Correia, V.H., Conimbriga: a vida de uma cidade da Lusitânia. 2024: Coimbra University Press.

- Alarcão, J. and R. Etienne, Fouilles de Conimbriga: Alarcão, J., et al. Céramiques diverses et verres. Vol. 6. 1976: Diffusion, E. de Boccard.

- Alarcão, P., Construir na ruína: a propósito da cidade romanizada de Conimbriga. 2009, Universidade do Porto (Portugal).

- Reis, M.P., De Lvsitaniae Vrbium Balneis. Estudo sobre as termas e balneários das cidades da Lusitânia, 2 vols., Tese de doutoramento em Arqueologia. Coimbra: Universidade de Coimbra, 2014.

- Ruivo, J., V.H. Correia, and A. De Man, A cronologia da muralha baixo-imperial de Conímbriga. In Ruivo J. and V.H. Correia (eds.), Conimbriga diripitur. Aspetos das ocupações tardias de uma antiga cidade romana, Coimbra, Universidade de Coimbra, 2021: p. 15-24.

- Ruivo, J. and V.H. Correia, Conimbriga diripitur: aspetos das ocupações tardias de uma antiga cidade romana. Vol. 67. 2021: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra/Coimbra University Press.

- De Man, A. and A.M. Soares, A datação pelo radiocarbono de contextos pós-romanos de Conimbriga. Revista Portuguesa de Arqueologia, 2007. 10(2): p. 285-294.

- Alarcão, J., Fouilles de Conimbriga V, in La céramique commune locale et régionale, D. Boccard, Editor. 1975: Paris.

- Correia, V.H. and A. De Man, Variação e constância na ocupação de Conimbriga e do seu território. 2010, CIDEHUS.

- Correia, V.H., Buraca, R. Triães and C. Oliveira, Identificação de uma produção de ânforas romanas no norte da Lusitânia. Revista Portuguesa de Arqueologia, 2015. 18: p. 225-136.

- Quinn, P.S., Ceramic petrography: the interpretation of archaeological pottery & related artefacts in thin section. 2013.

- Wentworth, C.K., A Scale of Grade and Class Terms for Clastic Sediments. The Journal of Geology, 1922. 30(5): p. 377-392.

- Riccardi, M., B. Messiga, and P. Duminuco, An approach to the dynamics of clay firing. Applied Clay Science, 1999. 15(3-4): p. 393-409.

- Gliozzo, E., Ceramic technology. How to reconstruct the firing process. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 2020. 12(11): p. 260.

- Maritan, L., et al., Influence of firing conditions on ceramic products: experimental study on clay rich in organic matter. Applied Clay Science, 2006. 31(1-2): p. 1-15.

- Heimann, R.B. and M. Maggetti, The struggle between thermodynamics and kinetics: Phase evolution of ancient and historical ceramics. In Artioli, G. and R. Oberti (eds.) The Contribution of Mineralogy to Cultural Heritage. European Mineral Union and the Mineralogical Society of Great Britain & Ireland, 2019. p. 233-281.

- Xanthopoulou, V., I. Iliopoulos, and I. Liritzis, Mineralogical and Microstructure Analysis for Characterization and Provenance of Ceramic Artifacts from Late Helladic Kastrouli Settlement, Delphi (Central Greece). Geosciences, 2021. 11(1): p. 36.

- Oliveira, C., I. Buraca, V.H. Correia and R. Trigães, Análises químicas de ânforas identificadas em Conímbriga. Al-madan, 2015. 19: p. 175-176.

- Buraca, I., C. Olveira, G. Elesi, J. Connan, R. Morais and V.H. Correia, In vino veritas. An assessment of current research of amphorae contents from Conimbriga (Portugal). DIAITA: Food&Heritage, 2025. 2: e0207.

- Lejay, M., et al., The organic signature of an experimental meat-cooking fireplace: The identification of nitrogen compounds and their archaeological potential. Organic Geochemistry, 2019. 138: p. 103923. [CrossRef]

- Lejay, M., et al., Organic signatures of fireplaces: Experimental references for archaeological interpretations. Organic Geochemistry, 2016. 99: p. 67-77. [CrossRef]

- Correia, V. H., Burada, I., Triães, R., Araújo, A., & Oliveira, C. Identification of a production of Roman amphorae in Northern Lusitania. In C. Oliveira, R. Morais, & Á. M. Cerdán (Eds.), ArchaeoAnalytics - Chromatography and DNA analysis in archaeology (pp. 169-184). Esposende City Council. 2015.

| Lab ID | Archaeological ID | Type | Chronology |

|---|---|---|---|

| A01 | 2004_IWT_2 | Conimbriga 1 | 1st to 3rd century AD |

| A02 | 2004_IWT_4 | Dressel 2-4 | 1st century AD (from 69 to 96 AD) |

| A03 | 66_H_VI_44_6 | Dressel 2-4 | 1st century AD (from 69 to 96 AD) |

| A05 | 67_H_VI_43_9 | Dressel 28 | Prior to the 3rd century AD |

| A06 | 66_U_11 | Gauloise 4 | Prior to the end of the 3rd century AD |

| A08 | 66_F_1/67/12 | Gauloise 4 | Prior to the end of the 3rd century AD |

| A09 | 69_H_VIII_47_5 | Conimbriga 2 | 4th century AD to last quarter of 5th century AD (from 305 to 476 AD) |

| A10 | 72_BF6_10 | Conimbriga 45-46 | Last quarter of the 1st century AD to the 3rd century AD |

| A11 | 71_CRY_Norte_Cano | Conimbriga 45-46 | Last quarter of the 1st century AD to the 3rd century AD |

| A12 | 72_BF1_7 | Gauloise 4 | Prior to the end of the 3rd century AD |

| Lab ID | Mineralogy | Rock fragments | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| A01 | Qz, K-Fsp, Pl, Ms. | Qzite. | Very abundant in Kfs (microcline) and Ms. |

| A02 | Qz, K-Fsp, Pl, Ms. | Not homogenized Clp identified. | |

| A03 | Qz, K-Fsp, Pl, Ms. | Not homogenized Clp identified. | |

| A05 | Qz, K-Fsp, Pl, Am, Ms. | Rare Am. Not homogenized Clp identified. | |

| A06 | Qz, K-Fsp, Pl, Ms. | ||

| A08 | Qz, K-Fsp, Pl, Ms. | Not homogenized Clp identified. | |

| A09 | Qz, K-Fsp, Pl, Ms, Bt (very rare). | Qzite. | Ms-rich. |

| A10 | Qz, K-Fsp, Pl, Ms, Bt (very rare). | Qzite, Clst, Gnrd. | Ms-rich. |

| A11 | Qz, K-Fsp, Pl, Ms, Bt, Grt. | Qzite, Clst, Gnrd. | Ms- and Bt-rich. |

| A12 | Qz, K-Fsp, Pl, Ms. | Not homogenized Clp identified. |

| Lab Id | Ceramic paste | Porosity | |||

| Color | Hom./Het. | Enrichment in Fe or Ca | Optical activity | Shape and size | |

| A01 | Brown | H.HOM. | Fe | S | Vesicles (meso) |

| A02 | Red | H.HOM. | Fe | S | Vesicles (meso) |

| A03 | Red | H.HOM. | Fe | S | Vesicles – Chanels (macro, mega) |

| A05 | Red | H.HOM. | Fe | S | Vesicles – Chanels (meso, macro) |

| A06 | Red | H.HOM. | Fe | S | Vesicles (micro, macro) |

| A08 | Red | H.HOM. | Fe | S | Vesicles (micro, meso) |

| A09 | Brown | M.HOM. | Fe | S | Vesicles – Planar voids (meso, macro) |

| A10 | Brown | M.HOM. | Fe | M | Vesicles – Chanels (meso, macro) |

| A11 | Brown | M.HOM. | Fe | M | Vesicles – Chanels (meso, macro) |

| A12 | Red | H.HOM. | Fe | NA | Vesicles (micro, meso) |

| LAB ID | Temper | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shape | Sphericity | Alignment | Packing | Sorting | GSD | DGSF | Temper % | |

| A01 | G | A-R | CS | P | M | U | VFS/FS | 20 |

| A02 | G | A-R | CS | F | W | U | CSilt | 10 |

| A03 | G | SR-R | CS | F | W | U | CSilt–VFS | 20 |

| A05 | G | SR-R | CS | F | W | U | CSilt | 20 |

| A06 | G | SA-R | CS | F | W | U | CSilt | 10 |

| A08 | G | SR-R | CS | F | W | B | CSilt/CSand | 10 |

| A09 | G/El | A-SR | CS | P | P | B | CSilt/CSand | 10 |

| A10 | G/El | VA-SA | OS | P | P | U | FS | 10 |

| A11 | G | A-SR | SP | M | M | B | VFS/CSand | 10 |

| A12 | G | SA-R | CS | F | W | U | CSilt | 20 |

| Lab ID | Qz | Kfs | Pl | Hm | I/M | Cal | Bt | Mul |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A02 | xxxx | x | xx | x | vs | x | ||

| A01 | xxxx | xx | x | xx | ||||

| A03 | xxxx | vs | vs | x | vs | |||

| A05 | xxxx | xx | vs | x | x | |||

| A06 | xxxx | xx | vs | x | vs | xx | ||

| A08 | xxxx | xx | vs | x | x | |||

| A09 | xxxx | xx | vs | vs | x | |||

| A10 | xxxx | x | vs | x | xxx | |||

| A11 | xxxx | xx | x | x | x | xxx | ||

| A12 | xxxx | xx | x | x |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).