4. Discussion

The findings presented in this study challenge prevailing geological models by introducing robust multidisciplinary evidence that supports the artificial manufacture of at least a portion of the world’s stone spheres. Key indicators include the presence of man-made additives such as calcium oxide and manganese, uniformity in mineral composition, spherical precision far exceeding known natural processes, and the absence of similar unshaped forms in otherwise volcanic or sedimentary regions.

The discovery of the 37-ton Podubravlje sphere (

Figure 9) establishes Bosnia-Herzegovina not only as a significant center of this phenomenon but as the location of the

largest recorded stone sphere in the world. Its immense mass, stratigraphic context, and unique material properties suggest advanced prehistoric knowledge of materials science, shaping techniques, and environmental integration—principles consistent with what modern scholars might categorize as an early form of geopolymer technology.

These findings add weight to the hypothesis that a now-lost civilization or cultural tradition developed methods of working stone on a monumental scale, far earlier than current historical timelines allow. The recurrence of such spheres in geographically and culturally disparate regions raises critical questions about cultural diffusion, ancient global networks, or parallel technological evolution.

Moreover, the diversity of materials—granite, volcanic, sandstone, limestone, and granodiorite—suggests that the builders adapted to local geologies while maintaining a consistent goal: creating near-perfect spheres. This speaks to shared values or cosmological beliefs associated with the sphere’s geometric and energetic properties.

The role of these stone spheres—whether symbolic, ritualistic, astronomical, or functional—remains open to interpretation. However, evidence of alignment, astronomical referencing (e.g.,

Figure 2), and anecdotal bioenergetic effects reported at several sites suggest a deeper connection between form, location, and purpose.

Ultimately, this research contributes a structured analytical framework for global stone sphere studies, paving the way for further interdisciplinary research that combines archaeology, geophysics, material science, and cultural anthropology.

Figure 1.

Representative examples of the enigmatic stone spheres of Costa Rica, all carved from granodiorite, a highly durable igneous rock. These spheres exhibit remarkable precision and scale, challenging mainstream assumptions about the technological capacities of ancient Central American cultures. Top left: A solitary stone sphere situated in Palmar Sur, southern Costa Rica, partially embedded in natural surroundings, illustrating its original landscape context (Osmanagich, 2005, p. 29). Top right: A large granodiorite sphere displayed in a public park in Palmar Sur. The presence of a human figure for scale highlights the sphere’s substantial size and near-perfect sphericity (p. 27). Bottom left: A collection of original stone spheres of varying diameters on exhibit at the National Museum in San José. The monumental megalith in the background, weighing over 30 tons, implies the use of highly advanced prehistoric technology well beyond the known capabilities of local cultures circa 1,500 years ago (p. 24). Bottom right: A large granodiorite sphere positioned on a custom stand in front of the High School in Palmar Norte, southern Costa Rica. This educational display underscores the continued cultural significance and reverence for these ancient artifacts in modern times (p. 27). (Source for all images: Osmanagich, S. (2005). Discovery of the First European Pyramid, Archaeological Park: Bosnian Pyramid of the Sun Foundation).

Figure 1.

Representative examples of the enigmatic stone spheres of Costa Rica, all carved from granodiorite, a highly durable igneous rock. These spheres exhibit remarkable precision and scale, challenging mainstream assumptions about the technological capacities of ancient Central American cultures. Top left: A solitary stone sphere situated in Palmar Sur, southern Costa Rica, partially embedded in natural surroundings, illustrating its original landscape context (Osmanagich, 2005, p. 29). Top right: A large granodiorite sphere displayed in a public park in Palmar Sur. The presence of a human figure for scale highlights the sphere’s substantial size and near-perfect sphericity (p. 27). Bottom left: A collection of original stone spheres of varying diameters on exhibit at the National Museum in San José. The monumental megalith in the background, weighing over 30 tons, implies the use of highly advanced prehistoric technology well beyond the known capabilities of local cultures circa 1,500 years ago (p. 24). Bottom right: A large granodiorite sphere positioned on a custom stand in front of the High School in Palmar Norte, southern Costa Rica. This educational display underscores the continued cultural significance and reverence for these ancient artifacts in modern times (p. 27). (Source for all images: Osmanagich, S. (2005). Discovery of the First European Pyramid, Archaeological Park: Bosnian Pyramid of the Sun Foundation).

Figure 2.

A prominent carved petroglyph is visible on the surface of a stone sphere housed in the National Museum in San José, Costa Rica. This image, taken by the author, illustrates an extraordinary example of prehistoric symbolic expression. Costa Rican astronomer Edwin Quesada analyzed the engravings and identified a striking correlation between the petroglyph patterns and known celestial constellations—specifically Pegasus (the winged horse) and Andromeda (the celestial princess). By comparing the lines and points carved into the stone sphere with star locations and the connecting lines used in astronomical charts, Quesada found an astonishing match: twenty-two constellations form a shape that mirrors the petroglyph. One spiral motif engraved on the sphere notably corresponds to the spiral shape of the Andromeda Galaxy (M31) as seen in astronomical representations, despite the fact that this galaxy appears only as a faint point of light in the night sky. This raises profound questions about how prehistoric people could have known its spiral structure without the aid of optical instruments. The constellation match includes: Beta Andromedae, Alpha Andromedae, Omicron Andromedae, HR8632 in Lacerta, Beta Pegasi, Psi Pegasi, Pi Pegasi, Gamma Pegasi, and multiple stars in Pisces (Theta, Iota, Lambda, Kappa, Gamma, and Omega), Beta Piscium, Eta Aquarii, Alpha Pegasi, Theta Pegasi, Theta Aquarii, Beta Aquarii, Alpha Equulei, Upsilon Pegasi, the Delphinus constellation, and two stars (HR8313 and HR8173) in Pegasus. The positioning of the petroglyph also suggests functionality: when the stone sphere is rotated from left to right, with Polaris (the North Star) oriented at the base, the movement of constellations from east to west—caused by Earth’s rotation—can be visualized. Thus, the sphere likely served not only as a celestial map but as a functional planetary model or star tracker—a prehistoric planetarium. An additional point of intrigue is the symbolic form of the petroglyph. It may depict a stylized animal from ancient Central American fauna—perhaps a dog, jaguar, or monkey—or it may represent a concept still beyond our current understanding. The deliberate design and astronomical accuracy suggest it carries a sophisticated message, pointing to a level of prehistoric knowledge far exceeding mainstream assumptions. (Source: Osmanagich, S. (2005). Discovery of the First European Pyramid, Archaeological Park: Bosnian Pyramid of the Sun Foundation, pp. 21–22).

Figure 2.

A prominent carved petroglyph is visible on the surface of a stone sphere housed in the National Museum in San José, Costa Rica. This image, taken by the author, illustrates an extraordinary example of prehistoric symbolic expression. Costa Rican astronomer Edwin Quesada analyzed the engravings and identified a striking correlation between the petroglyph patterns and known celestial constellations—specifically Pegasus (the winged horse) and Andromeda (the celestial princess). By comparing the lines and points carved into the stone sphere with star locations and the connecting lines used in astronomical charts, Quesada found an astonishing match: twenty-two constellations form a shape that mirrors the petroglyph. One spiral motif engraved on the sphere notably corresponds to the spiral shape of the Andromeda Galaxy (M31) as seen in astronomical representations, despite the fact that this galaxy appears only as a faint point of light in the night sky. This raises profound questions about how prehistoric people could have known its spiral structure without the aid of optical instruments. The constellation match includes: Beta Andromedae, Alpha Andromedae, Omicron Andromedae, HR8632 in Lacerta, Beta Pegasi, Psi Pegasi, Pi Pegasi, Gamma Pegasi, and multiple stars in Pisces (Theta, Iota, Lambda, Kappa, Gamma, and Omega), Beta Piscium, Eta Aquarii, Alpha Pegasi, Theta Pegasi, Theta Aquarii, Beta Aquarii, Alpha Equulei, Upsilon Pegasi, the Delphinus constellation, and two stars (HR8313 and HR8173) in Pegasus. The positioning of the petroglyph also suggests functionality: when the stone sphere is rotated from left to right, with Polaris (the North Star) oriented at the base, the movement of constellations from east to west—caused by Earth’s rotation—can be visualized. Thus, the sphere likely served not only as a celestial map but as a functional planetary model or star tracker—a prehistoric planetarium. An additional point of intrigue is the symbolic form of the petroglyph. It may depict a stylized animal from ancient Central American fauna—perhaps a dog, jaguar, or monkey—or it may represent a concept still beyond our current understanding. The deliberate design and astronomical accuracy suggest it carries a sophisticated message, pointing to a level of prehistoric knowledge far exceeding mainstream assumptions. (Source: Osmanagich, S. (2005). Discovery of the First European Pyramid, Archaeological Park: Bosnian Pyramid of the Sun Foundation, pp. 21–22).

Figure 3.

Comparative examples of stone spheres from two geographically distant regions, illustrating the global presence of this archaeological phenomenon and its varied geological compositions. Left: The author on Easter Island alongside a cluster of volcanic stone spheres, featuring one larger central sphere surrounded by six smaller ones. These spheres, sculpted from volcanic material, are located near the ocean and partially enclosed by a ring of stone blocks. Their presence on an island renowned for its monumental moai statues suggests that the tradition of shaping massive stone artifacts may have been part of a broader prehistoric cultural pattern (Source: Osmanagich, 2005). Right: Stone spheres in Mirdita, northern Albania, carved from sandstone and partially embedded in a wooded hillside. At least two spheres remain visible, although others have been heavily damaged or destroyed. Local residents, believing the spheres contained hidden treasure, deliberately broke them open—leading to the irreversible loss of valuable archaeological evidence. This example highlights the vulnerability of such sites and underscores the urgent need for protective measures and public education regarding their significance.

Figure 3.

Comparative examples of stone spheres from two geographically distant regions, illustrating the global presence of this archaeological phenomenon and its varied geological compositions. Left: The author on Easter Island alongside a cluster of volcanic stone spheres, featuring one larger central sphere surrounded by six smaller ones. These spheres, sculpted from volcanic material, are located near the ocean and partially enclosed by a ring of stone blocks. Their presence on an island renowned for its monumental moai statues suggests that the tradition of shaping massive stone artifacts may have been part of a broader prehistoric cultural pattern (Source: Osmanagich, 2005). Right: Stone spheres in Mirdita, northern Albania, carved from sandstone and partially embedded in a wooded hillside. At least two spheres remain visible, although others have been heavily damaged or destroyed. Local residents, believing the spheres contained hidden treasure, deliberately broke them open—leading to the irreversible loss of valuable archaeological evidence. This example highlights the vulnerability of such sites and underscores the urgent need for protective measures and public education regarding their significance.

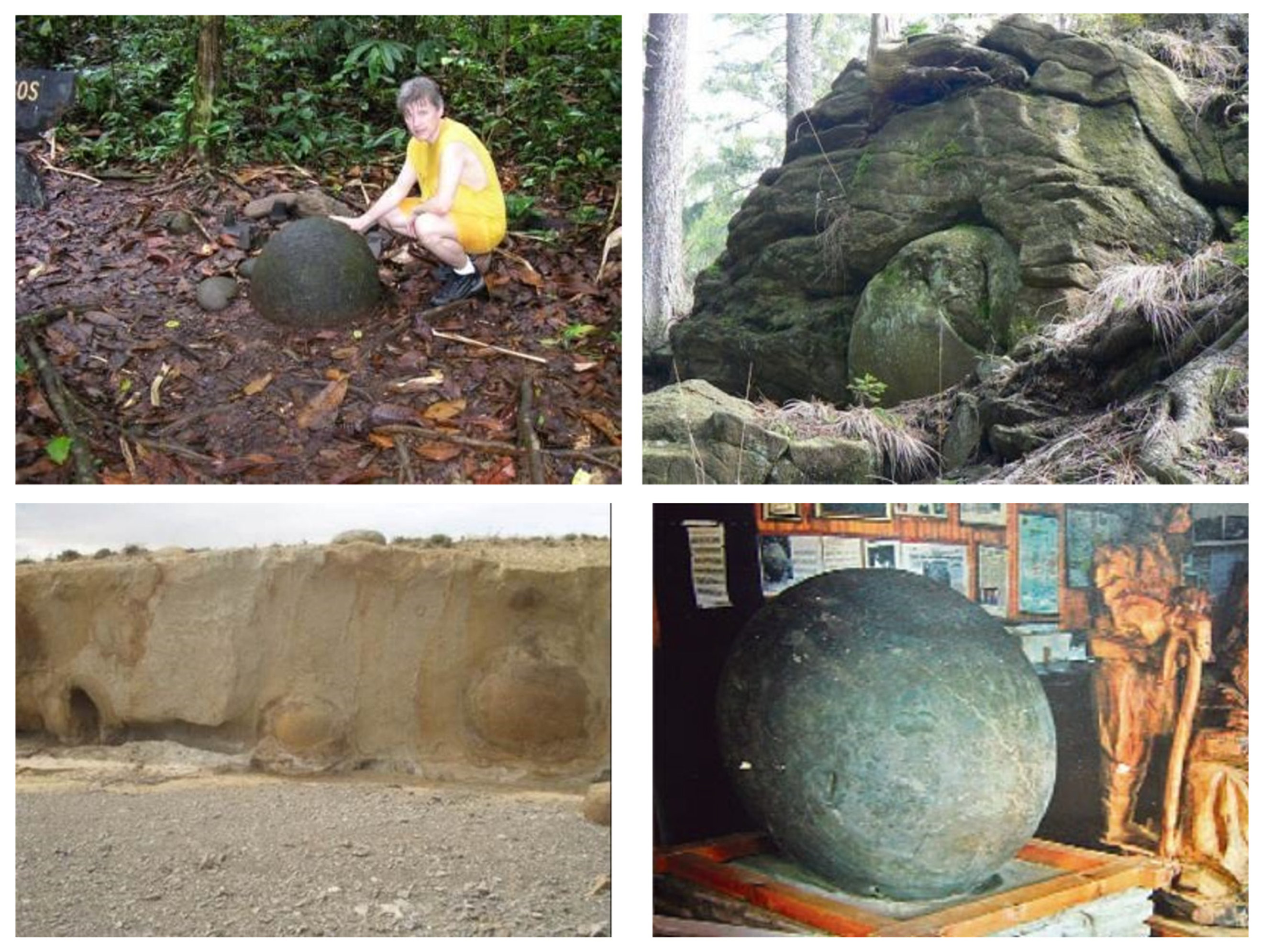

Figure 4.

Globally distributed examples of perfectly spherical stone balls made from various types of rock, further challenging the hypothesis of natural geological origin and suggesting widespread prehistoric knowledge of advanced shaping techniques. Top left: A stone sphere on Isla del Caño, located off the Pacific coast of Costa Rica. Composed of coquina—a soft limestone formed from shell fragments—this specimen demonstrates high precision in shaping despite the relatively friable material (Source: author’s private documentation). Top right: A sandstone stone sphere embedded in a rock face near the border of Slovakia and the Czech Republic. The layers of sediment accumulated above and around the sphere suggest that it has been in situ for an extended period, indicating significant antiquity. Bottom left: Spherical limestone formations in an oasis in southwestern Egypt. Similar to the Slovak-Czech example, these spheres are partially buried beneath compacted sediment, implying extreme age and challenging natural formation theories based solely on erosion or concretion. Bottom right: A volcanic stone sphere formerly displayed in western Serbia. Notable for its uniform roundness and dense material, this artifact was tragically destroyed in a fire in 2004. Its documented precision and composition prior to its destruction added valuable evidence to the global stone sphere record. All four examples exhibit near-perfect sphericity and are made from geologically distinct materials—including volcanic rock, sandstone, limestone, and coquina—making the likelihood of identical natural formation processes across such varied environments highly improbable.

Figure 4.

Globally distributed examples of perfectly spherical stone balls made from various types of rock, further challenging the hypothesis of natural geological origin and suggesting widespread prehistoric knowledge of advanced shaping techniques. Top left: A stone sphere on Isla del Caño, located off the Pacific coast of Costa Rica. Composed of coquina—a soft limestone formed from shell fragments—this specimen demonstrates high precision in shaping despite the relatively friable material (Source: author’s private documentation). Top right: A sandstone stone sphere embedded in a rock face near the border of Slovakia and the Czech Republic. The layers of sediment accumulated above and around the sphere suggest that it has been in situ for an extended period, indicating significant antiquity. Bottom left: Spherical limestone formations in an oasis in southwestern Egypt. Similar to the Slovak-Czech example, these spheres are partially buried beneath compacted sediment, implying extreme age and challenging natural formation theories based solely on erosion or concretion. Bottom right: A volcanic stone sphere formerly displayed in western Serbia. Notable for its uniform roundness and dense material, this artifact was tragically destroyed in a fire in 2004. Its documented precision and composition prior to its destruction added valuable evidence to the global stone sphere record. All four examples exhibit near-perfect sphericity and are made from geologically distinct materials—including volcanic rock, sandstone, limestone, and coquina—making the likelihood of identical natural formation processes across such varied environments highly improbable.

Figure 5.

Examples of spherical stone artifacts from four different regions, emphasizing global distribution, diversity of materials, and the ongoing debate surrounding their origin.

Top left: A polished granite stone sphere near the Hagia Sophia (Aya Sofia) in Istanbul, Turkey. These spheres have endured through centuries of conquest, likely due to their symbolic neutrality, having no religious or national connotations. Their continued presence in one of the world’s most historically contested sites suggests both resilience and cultural detachment (Source: Author’s private collection).

Top right: Two of the estimated 250 multi-ton volcanic stone spheres discovered in western Mexico. Some specimens reach up to 25 tons in weight. While a 1965 U.S. archaeological report suggested they were artificially created, a subsequent National Geographic-sponsored expedition concluded that a nearby volcano (approximately 30 miles away) had naturally produced the spheres during a unique geological event—never observed before or since. The claim remains highly controversial. Furthermore, 80% of the spheres were destroyed in the 1960s by locals searching for hidden treasure, often using dynamite.

Bottom left: Large spherical formations found on the coast of New Zealand, commonly referred to as the Moeraki Boulders. Mainstream geology identifies them as septarian concretions formed by calcium carbonate precipitating around a nucleus over 65 million years ago. However, this interpretation—despite being supported by multiple sedimentological studies (e.g., Boles et al., 1985; Thyne & Boles, 1989; Forsyth & Coates, 1992; Fordyce & Maxwell, 2003)—is contested in the context of the global phenomenon of near-perfect stone spheres. The extraordinary uniformity and large size of the Moeraki Boulders, especially when compared with similar artifacts worldwide, challenge the sufficiency of natural processes alone to account for such precision and distribution. (Source:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moeraki_Boulders, accessed on May 7, 2025).

Bottom right: A weathered sandstone stone sphere positioned near a building wall in northern Italy. Its placement and condition suggest repurposing from an earlier context, yet its geometric integrity remains evident, contributing to the broader catalogue of similar artifacts across Europe. These spheres—crafted or shaped from granite, volcanic rock, sandstone, and calcium carbonate—further support the hypothesis of widespread prehistoric technological capabilities, especially in light of their consistency in shape across distinct geological and cultural environments. (Source: Author’s private collection).

Figure 5.

Examples of spherical stone artifacts from four different regions, emphasizing global distribution, diversity of materials, and the ongoing debate surrounding their origin.

Top left: A polished granite stone sphere near the Hagia Sophia (Aya Sofia) in Istanbul, Turkey. These spheres have endured through centuries of conquest, likely due to their symbolic neutrality, having no religious or national connotations. Their continued presence in one of the world’s most historically contested sites suggests both resilience and cultural detachment (Source: Author’s private collection).

Top right: Two of the estimated 250 multi-ton volcanic stone spheres discovered in western Mexico. Some specimens reach up to 25 tons in weight. While a 1965 U.S. archaeological report suggested they were artificially created, a subsequent National Geographic-sponsored expedition concluded that a nearby volcano (approximately 30 miles away) had naturally produced the spheres during a unique geological event—never observed before or since. The claim remains highly controversial. Furthermore, 80% of the spheres were destroyed in the 1960s by locals searching for hidden treasure, often using dynamite.

Bottom left: Large spherical formations found on the coast of New Zealand, commonly referred to as the Moeraki Boulders. Mainstream geology identifies them as septarian concretions formed by calcium carbonate precipitating around a nucleus over 65 million years ago. However, this interpretation—despite being supported by multiple sedimentological studies (e.g., Boles et al., 1985; Thyne & Boles, 1989; Forsyth & Coates, 1992; Fordyce & Maxwell, 2003)—is contested in the context of the global phenomenon of near-perfect stone spheres. The extraordinary uniformity and large size of the Moeraki Boulders, especially when compared with similar artifacts worldwide, challenge the sufficiency of natural processes alone to account for such precision and distribution. (Source:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moeraki_Boulders, accessed on May 7, 2025).

Bottom right: A weathered sandstone stone sphere positioned near a building wall in northern Italy. Its placement and condition suggest repurposing from an earlier context, yet its geometric integrity remains evident, contributing to the broader catalogue of similar artifacts across Europe. These spheres—crafted or shaped from granite, volcanic rock, sandstone, and calcium carbonate—further support the hypothesis of widespread prehistoric technological capabilities, especially in light of their consistency in shape across distinct geological and cultural environments. (Source: Author’s private collection).

Figure 6.

Examples of large, nearly spherical stone formations found in extreme and remote locations, raising questions about their origin—natural or artificial—and contributing to the ongoing debate about prehistoric technological capabilities and unexplained global parallels. Top left: A perfectly spherical stone on Champ Island in the Franz Josef Land archipelago, Russian Arctic. These formations, scattered across the icy landscape, have attracted global attention due to their remote polar location and unusual symmetry. Their presence in one of the harshest climates on Earth further complicates traditional geological explanations. (Source: Arctic Travel Centre, accessed May 7, 2025) Top right: A group of smooth, meter-wide stone spheres discovered deep underground in a Siberian coal mine. Found during excavation work, these spheres were initially thought to be of natural origin, yet their regularity, symmetry, and the fact that they were found deeply buried raises the possibility of a non-natural origin. (Source: The Siberian Times, accessed May 7, 2025) Bottom left: The Valley of Stone Balls on the Mangyshlak Peninsula, Kazakhstan, features hundreds of massive spherical stones scattered across the steppes. Estimated to date back between 180 and 120 million years, these spheres are composed largely of silicate and carbonate cement. While mainstream science attributes their formation to large concretions during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, the precision of their spherical shapes and the sheer quantity invite alternative theories—including the possibility of an ancient civilization’s involvement. (Sources: Kazakhstan Travel and Tourism Blog; Indian Defence Review; accessed May 7, 2025) Bottom right: A granite stone sphere located near Šibenik, Croatia, documented by the author. This well-preserved specimen is representative of other European stone spheres and contributes to the hypothesis that the phenomenon is not limited to tropical or volcanic regions, but extends across diverse environments and geological contexts. While conventional geology explains these formations through processes such as spheroidal weathering, massive concretions, or volcanic megaspherulites, the remarkable consistency in form, geographical spread, and material diversity suggests a more complex origin—potentially linked to lost or unknown prehistoric civilizations. (Sources: See image-specific citations above; bottom right from Author’s private collection).

Figure 6.

Examples of large, nearly spherical stone formations found in extreme and remote locations, raising questions about their origin—natural or artificial—and contributing to the ongoing debate about prehistoric technological capabilities and unexplained global parallels. Top left: A perfectly spherical stone on Champ Island in the Franz Josef Land archipelago, Russian Arctic. These formations, scattered across the icy landscape, have attracted global attention due to their remote polar location and unusual symmetry. Their presence in one of the harshest climates on Earth further complicates traditional geological explanations. (Source: Arctic Travel Centre, accessed May 7, 2025) Top right: A group of smooth, meter-wide stone spheres discovered deep underground in a Siberian coal mine. Found during excavation work, these spheres were initially thought to be of natural origin, yet their regularity, symmetry, and the fact that they were found deeply buried raises the possibility of a non-natural origin. (Source: The Siberian Times, accessed May 7, 2025) Bottom left: The Valley of Stone Balls on the Mangyshlak Peninsula, Kazakhstan, features hundreds of massive spherical stones scattered across the steppes. Estimated to date back between 180 and 120 million years, these spheres are composed largely of silicate and carbonate cement. While mainstream science attributes their formation to large concretions during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, the precision of their spherical shapes and the sheer quantity invite alternative theories—including the possibility of an ancient civilization’s involvement. (Sources: Kazakhstan Travel and Tourism Blog; Indian Defence Review; accessed May 7, 2025) Bottom right: A granite stone sphere located near Šibenik, Croatia, documented by the author. This well-preserved specimen is representative of other European stone spheres and contributes to the hypothesis that the phenomenon is not limited to tropical or volcanic regions, but extends across diverse environments and geological contexts. While conventional geology explains these formations through processes such as spheroidal weathering, massive concretions, or volcanic megaspherulites, the remarkable consistency in form, geographical spread, and material diversity suggests a more complex origin—potentially linked to lost or unknown prehistoric civilizations. (Sources: See image-specific citations above; bottom right from Author’s private collection).

Figure 7.

Representative stone spheres from various regions of Bosnia-Herzegovina, showcasing different geological materials, states of preservation, and discovery contexts. These examples support the hypothesis of intentional manufacture and long-term cultural significance. Top left: A well-preserved granite sphere near the village of Teočak in northeastern Bosnia, cemented into a display wall near the local mosque in the 2010s. The material—granite—does not naturally form into spherical shapes, and the size and symmetry of this artifact far exceed that of traditional cannonballs (topovsko đule), indicating an artificial origin. (Source: Osmanagich, S. (2005), p. 47) Top right: A polished volcanic stone sphere partially buried in a snowy field. Originally discovered during tunnel excavation in the 1970s, its location and smooth surface finish suggest careful crafting and possible ritual or structural placement. (Source: Ibid., p. 55) Bottom left: A sandstone stone sphere being excavated at the top of a mountain Brnjic in central Bosnia during a winter 2010 field campaign. The team carefully uncovered the artifact from beneath a thin layer of snow and soil, revealing its near-perfect curvature. (Source: Author’s private collection) Bottom right: A large stone sphere located in central Bosnia, near the town of Vareš. The sphere, once hidden beneath a tree, has since been relocated to a mountain restaurant site, where it now bears spray-painted graffiti—”101 Mtbr. Logistik”—a remnant from the 1990s wartime period. Despite the defacement, the sphere remains intact and continues to attract archaeological and public interest. (Source: Osmanagich, S. (2005), p. 48) These examples—crafted from granite, volcanic rock, and sandstone—exhibit high sphericity and diverse locations, reinforcing the broader pattern of intentional placement and construction associated with the Bosnian stone sphere phenomenon.

Figure 7.

Representative stone spheres from various regions of Bosnia-Herzegovina, showcasing different geological materials, states of preservation, and discovery contexts. These examples support the hypothesis of intentional manufacture and long-term cultural significance. Top left: A well-preserved granite sphere near the village of Teočak in northeastern Bosnia, cemented into a display wall near the local mosque in the 2010s. The material—granite—does not naturally form into spherical shapes, and the size and symmetry of this artifact far exceed that of traditional cannonballs (topovsko đule), indicating an artificial origin. (Source: Osmanagich, S. (2005), p. 47) Top right: A polished volcanic stone sphere partially buried in a snowy field. Originally discovered during tunnel excavation in the 1970s, its location and smooth surface finish suggest careful crafting and possible ritual or structural placement. (Source: Ibid., p. 55) Bottom left: A sandstone stone sphere being excavated at the top of a mountain Brnjic in central Bosnia during a winter 2010 field campaign. The team carefully uncovered the artifact from beneath a thin layer of snow and soil, revealing its near-perfect curvature. (Source: Author’s private collection) Bottom right: A large stone sphere located in central Bosnia, near the town of Vareš. The sphere, once hidden beneath a tree, has since been relocated to a mountain restaurant site, where it now bears spray-painted graffiti—”101 Mtbr. Logistik”—a remnant from the 1990s wartime period. Despite the defacement, the sphere remains intact and continues to attract archaeological and public interest. (Source: Osmanagich, S. (2005), p. 48) These examples—crafted from granite, volcanic rock, and sandstone—exhibit high sphericity and diverse locations, reinforcing the broader pattern of intentional placement and construction associated with the Bosnian stone sphere phenomenon.

Figure 8.

Representative stone spheres from four distinct locations in Bosnia-Herzegovina, each offering unique insights into the diversity of geological material, condition of preservation, and local oral histories surrounding their discovery. Top left: A precisely shaped sandstone sphere from the village of Trn, near Banja Luka in northwestern Bosnia. During home foundation excavations at a depth of 4–5 meters, local resident Čedo Tešanović uncovered two spheres with diameters between 30 and 40 cm. Although one was unfortunately embedded into the foundation, another was found nearby at the property of Milorad Dakić—intact until local workers, curious about its contents, broke it into two symmetrical halves. (Source: Osmanagich, S., Bosanska piramida Sunca, p. 45) Top right: The weathered surface of a stone sphere in Ponikve, near Zlokuće village, central Bosnia. Composed of the same magmatic material found in Trn, this sphere is part of a cluster of rounded and elongated megaliths partially buried on a small 10-meter rise. Locals refer to the site as part of a “Greek cemetery,” linked to legends of ancient Greek settlers, and attribute healing properties to the spheres—especially for horses with urinary difficulties. (Source: Ibid., p. 49) Bottom left: A stone sphere originally found in the Megara stream near the village of Jablanica, close to Maglaj. Discovered in the 1970s by Mustafa Mehinagić, it was retrieved from the stream and relocated to his yard with the help of three men. The circumference of the sphere was measured at 155 cm. (Source: Ibid., p. 52) Bottom right: A sandstone sphere located in the village of Slatina, near Banja Luka. Close examination reveals unfinished surface texture, suggesting coarse shaping using a scoop-like tool, but lacking the final polishing phase that would have produced a perfectly smooth sphericity. (Source: Ibid., p. 56) These Bosnian examples highlight varied states of completion and preservation, but all demonstrate intentional shaping and contribute to the broader understanding of the prehistoric stone sphere phenomenon in the region.

Figure 8.

Representative stone spheres from four distinct locations in Bosnia-Herzegovina, each offering unique insights into the diversity of geological material, condition of preservation, and local oral histories surrounding their discovery. Top left: A precisely shaped sandstone sphere from the village of Trn, near Banja Luka in northwestern Bosnia. During home foundation excavations at a depth of 4–5 meters, local resident Čedo Tešanović uncovered two spheres with diameters between 30 and 40 cm. Although one was unfortunately embedded into the foundation, another was found nearby at the property of Milorad Dakić—intact until local workers, curious about its contents, broke it into two symmetrical halves. (Source: Osmanagich, S., Bosanska piramida Sunca, p. 45) Top right: The weathered surface of a stone sphere in Ponikve, near Zlokuće village, central Bosnia. Composed of the same magmatic material found in Trn, this sphere is part of a cluster of rounded and elongated megaliths partially buried on a small 10-meter rise. Locals refer to the site as part of a “Greek cemetery,” linked to legends of ancient Greek settlers, and attribute healing properties to the spheres—especially for horses with urinary difficulties. (Source: Ibid., p. 49) Bottom left: A stone sphere originally found in the Megara stream near the village of Jablanica, close to Maglaj. Discovered in the 1970s by Mustafa Mehinagić, it was retrieved from the stream and relocated to his yard with the help of three men. The circumference of the sphere was measured at 155 cm. (Source: Ibid., p. 52) Bottom right: A sandstone sphere located in the village of Slatina, near Banja Luka. Close examination reveals unfinished surface texture, suggesting coarse shaping using a scoop-like tool, but lacking the final polishing phase that would have produced a perfectly smooth sphericity. (Source: Ibid., p. 56) These Bosnian examples highlight varied states of completion and preservation, but all demonstrate intentional shaping and contribute to the broader understanding of the prehistoric stone sphere phenomenon in the region.

Figure 9.

Significant archaeological and geological documentation of stone spheres in central Bosnia, particularly near the town of Zavidovići, highlighting both historical damage and recent discoveries. Top left: Professor Muhamed Pašić and researcher Ahmed Bosnić collecting fragments from a damaged stone sphere for petrographic and physical-chemical analysis in Duboki Potok, near Zavidovići, in November 2008. This location witnessed a natural event in 1936 when approximately 80 spheres rolled down the hill during a storm. Sadly, many were destroyed by locals in the 1960s in search of supposed treasure, with smaller spheres being relocated to private properties or carried downstream toward the Bosna River. (Source: Author’s private collection) Top right: An unfinished stone sphere near the town of Zenica in central Bosnia. The visible tool marks and rough shaping suggest it was abandoned before the polishing phase. A hammer placed alongside the sphere provides a sense of scale. (Source: Author’s private collection) Bottom left: The author measuring the diameter of a newly discovered stone sphere in the village of Podubravlje, near Zavidovići. The find contributes to the growing inventory of precisely formed megalithic spheres in the region. (Source: Osmanagich, S., My Story, 2023, p. 176) Bottom right: Full excavation of the Podubravlje sphere revealed it to be the most massive stone sphere discovered to date, with an estimated weight of over 37 tons (37,320 kg). The site has since become a regional tourist attraction, promoted and maintained by the Archaeological Park: Bosnian Pyramid of the Sun Foundation. (Source: Ibid., p. 178) These images underscore the historical, scientific, and cultural significance of the Bosnian stone spheres and the efforts made to preserve and study them systematically.

Figure 9.

Significant archaeological and geological documentation of stone spheres in central Bosnia, particularly near the town of Zavidovići, highlighting both historical damage and recent discoveries. Top left: Professor Muhamed Pašić and researcher Ahmed Bosnić collecting fragments from a damaged stone sphere for petrographic and physical-chemical analysis in Duboki Potok, near Zavidovići, in November 2008. This location witnessed a natural event in 1936 when approximately 80 spheres rolled down the hill during a storm. Sadly, many were destroyed by locals in the 1960s in search of supposed treasure, with smaller spheres being relocated to private properties or carried downstream toward the Bosna River. (Source: Author’s private collection) Top right: An unfinished stone sphere near the town of Zenica in central Bosnia. The visible tool marks and rough shaping suggest it was abandoned before the polishing phase. A hammer placed alongside the sphere provides a sense of scale. (Source: Author’s private collection) Bottom left: The author measuring the diameter of a newly discovered stone sphere in the village of Podubravlje, near Zavidovići. The find contributes to the growing inventory of precisely formed megalithic spheres in the region. (Source: Osmanagich, S., My Story, 2023, p. 176) Bottom right: Full excavation of the Podubravlje sphere revealed it to be the most massive stone sphere discovered to date, with an estimated weight of over 37 tons (37,320 kg). The site has since become a regional tourist attraction, promoted and maintained by the Archaeological Park: Bosnian Pyramid of the Sun Foundation. (Source: Ibid., p. 178) These images underscore the historical, scientific, and cultural significance of the Bosnian stone spheres and the efforts made to preserve and study them systematically.

Figure 10.

Laboratory analysis of the massive stone sphere discovered in Podubravlje, conducted by the Faculty of Mining, Geology and Civil Engineering, University of Tuzla in 2016. The analysis, commissioned by the Archaeological Park: Bosnian Pyramid of the Sun Foundation, focused on determining the density of solid particles within the stone material, a crucial parameter for estimating the total mass of the sphere. The test, led by Mr. sc. Mersudin Hodžić, dipl. ing. geology, reported a specific particle density (ρₛ) of 2.64 g/cm³. This value supports prior projections that the total mass of the Podubravlje sphere exceeds 30 tons, making it potentially the most massive stone sphere recorded to date. The sample used in the analysis was labeled “Big stone sphere,” confirming its origin from the 2016 excavation site. (Source: Faculty of Mining, Geology and Civil Engineering, University of Tuzla; Commissioned by Archaeological Park: Bosnian Pyramid of the Sun Foundation, 2016).

Figure 10.

Laboratory analysis of the massive stone sphere discovered in Podubravlje, conducted by the Faculty of Mining, Geology and Civil Engineering, University of Tuzla in 2016. The analysis, commissioned by the Archaeological Park: Bosnian Pyramid of the Sun Foundation, focused on determining the density of solid particles within the stone material, a crucial parameter for estimating the total mass of the sphere. The test, led by Mr. sc. Mersudin Hodžić, dipl. ing. geology, reported a specific particle density (ρₛ) of 2.64 g/cm³. This value supports prior projections that the total mass of the Podubravlje sphere exceeds 30 tons, making it potentially the most massive stone sphere recorded to date. The sample used in the analysis was labeled “Big stone sphere,” confirming its origin from the 2016 excavation site. (Source: Faculty of Mining, Geology and Civil Engineering, University of Tuzla; Commissioned by Archaeological Park: Bosnian Pyramid of the Sun Foundation, 2016).