1. Introduction

Abiotic stressors, such as salinity, significantly affect the growth and development of glycophytic plants (Soltabayeva et al., 2021; Ventura et al., 2014). The high salt concentrations inhibit plant cell growth, affecting morphological, physiological, and biochemical attributes (Castañeda-Loaiza et al., 2020; Ventura & Sagi, 2013). Halophyte plants are highly adapted to saline soils (Lombardi et al., 2022; Ventura & Sagi, 2013) through mechanisms such as salt exclusion and water storage in succulent tissues (Castañeda-Loaiza et al., 2020; Ventura et al., 2014). Halophytes naturally thrive in environments with high NaCl concentrations, such as salt marshes and coastal regions (Custódio et al., 2021; Ventura et al., 2015). Due to their tolerance, halophytes are being explored as promising alternative crops in response to the growing challenges of freshwater scarcity and soil salinization (Custódio et al., 2021; Kaushal et al., 2018; Sisay et al., 2022a; Ventura et al., 2015; Ventura & Sagi, 2013). Several halophyte species, such as Sarcocornia, Salicornia, and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum (AM), have been successfully cultivated at varying salinity levels, making them valuable for cultivation in saline soils (Agudelo et al., 2021; Barreira et al., 2017; Custódio et al., 2021; ElNaker et al., 2020; Redondo-Gómez et al., 2010; Rodrigues et al., 2014; Ventura et al., 2011a; Ventura et al., 2011b). Sarcocornia ecotypes and AM are perennial plants that can, with appropriate agro technique, produce young succulent shoots throughout the year, allowing for multiple harvests without flowering (Sisay et al., 2022; Ventura et al., 2014b; Ventura & Sagi, 2013) and thus, providing a continuous supply of marketable vegetables. This increases farmers’ profitability, and can also act as an important food source in coastal communities as well as a specialty vegetable in European and North America markets (Antunes et al., 2021; Barreira et al., 2017; Custódio et al., 2021; Lombardi et al., 2022; Sisay et al., 2022a; Ventura & Sagi, 2013). Additionally, its use in salads and cookery is a natural salt substitute (Barreira et al., 2017; Custódio et al., 2021; Ventura et al., 2011). AM and Sarcocornia are good sources of antioxidants, vitamins, and essential nutrients in human diets and therefore beneficial for preventing disease (Barreira et al., 2017).

Abiotic stress negatively impacts plant growth and yield by generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) and toxic aldehydes; their overproduction may cause metabolic imbalances and cellular and tissue damage, leading to senescence (Mohammadi & Kardan, 2015; Patel et al., 2025; Ventura et al., 2014). Plants, including halophytes, generate antioxidants to mitigate the effects of ROS-induced oxidative stress and enhance tolerance to environmental stressors (Mishra et al., 2015). Antioxidants, including polyphenols, flavonoids, carotenoids, and anthocyanins, play crucial roles in plant defence and adaptation to stress (Barreira et al., 2017; Boughalleb & Denden, 2011; Forghani et al., 2024; Rudrapal et al., 2022; Sisay et al., 2022). The antioxidant compounds protect plants from oxidative damage and support growth in harsh conditions (Khlestkina, 2013; Marone et al., 2022).

Previous research has primarily focused on the effects of different salt levels on plant growth, biomass yields, and nutritional content, while little attention has been paid to the impact of successive harvesting intervals on yield, nutritional value, and antioxidant composition in Sarcocornia (Ventura et al., 2011a) and AM. The current study explored the effects of 21-day and 30-day successive harvesting regimes in five Sarcocornia ecotypes and one AM ecotype growing under two different salinity levels on plant growth, accumulated biomass productivity, and nutritional value.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

We used Sarcocornia fruiticosa VM, which has been used before (Ventura et al., 2011a). The other Sarcocornia ecotypes were collected from the Israeli coastal area as follows: Naaman (Naa) ecotype was collected near the Naaman river (Akko), Megadim (Meg) ecotype from the Mediterranean Sea shore area near Megadim town, Shikmona (Shik) and Ruhama (Ruh) ecotypes were collected from the Shikmona Marine Reserve located in the southern part of the city of Haifa, and the AM seeds from the Dead Sea area (Sisay et al., 2022). Seeds were sown in plastic pots [12x8x6 cm (Length × Width × Depth)] in autoclave-sterilized soil. Seed germination was visible after 7 days. During the initial seed germination and seedling establishment phase, tap water (0.9 ds m-1) was used. Seedlings were grown in a controlled temperature growth room (25 to 30°C, long-day (16:8 hours light: dark), and light was supplied via 100W fluorescent tubes, providing 200 µmol m2 s-1.

After germination and establishment, seedlings were irrigated with low salinity water [50 mM NaCl plus 1-gram NPK (20-20-20 + micronutrients, Haifa Chemicals, Israel)]. When they reached 2cm in length, equally sized seedlings were carefully transferred to 3-liter plastic pots containing 14 seedlings per ecotype. The experiment was conducted in a greenhouse under natural day length and with a temperature range of 10ºC to 40ºC, the relative humidity was 75%, and PAR ranges 650–700 µmol m2 s-1. The salinity levels of 50 mM and 150 mM NaCl, including 1 g L-1 NPK nutrients [20-20-20 + micronutrients (Haifa Chemicals, Israel)] were supplemented with 4 mM NH4NO3. The nitrogen in the 20-20-20 was ammonium (1.5 mM), nitrate (2.2 mM), and urea (3.7 mM). K and P were 0.3 mM P as P2O5 and 0.4 mM K as K2O. Micronutrients were Mo 70 ppm, Cu 110 ppm, Zn 150 ppm, Mn 500 ppm, and Fe 1000 ppm.

2.2. Harvest Regime

The first harvest was a technical cut to generate the cutting table for future harvests. This was done when plants reached 16 cm in height. Everything above 10 cm from the soil level was removed and discarded. Then, plants were successively cropped at intervals of either 21 days or 30 days over 210 days, giving to a total number of ten and seven harvests, respectively. The fresh biomass was weighed immediately after harvest and expressed on a kg per m2 basis. Immediately after harvesting fresh shoots, shoot diameter was detected, and samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C until analysis.

2.3. Shoot Diameter

The shoot diameter was measured in the middle section of the third segment from the top of the harvested shoot. Six shoots from each ecotype were used at a salinity level in a harvest regime.

2.4. Chlorophyll and Total Carotenoid Content

100 mg fresh tissue was extracted with 80% ethanol (m/v, 1:10) and incubated in the dark at 4°C for 48 hours until the tissue was colorless. The samples were centrifuged at 18,400 rcf for 15 min at 4ºC, then transferred into new tubes and centrifuged again. 0.2 mL was used, and the absorbance was read at 665 nm, 649 nm, 652 nm, and 470 nm for chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll, and total carotenoids, respectively. The calculations were carried out as described by Ben-Amotz et al. (1988) and Lichtenthaler (1987)

2.5. Relative Water Content (RWC)

Relative water content was determined as described before (Sisay et al., 2022):

where FW is fresh weight, DW is dry weight, and TW is turgid weight.

2.6. Total Protein Content

Total protein content was measured following the protocol of Sarkar et al. (2020) with slight modifications. Briefly, 100 mg of frozen shoot tissue was ground under liquid nitrogen and then mixed with extraction buffer (m/w 1:20). The extraction buffer was prepared by mixing 0.8 grams of sodium chloride, 0.02 grams of potassium chloride, 0.144 grams of sodium dihydrogen phosphate, and 0.0245 grams of potassium dihydrogen phosphate, with 80 mL double distilled water. The pH was adjusted to 7.4 in a total volume of 100 mL. The extract was centrifuged at 10,000 rcf for 10 minutes at 4 °C. Thereafter 4.5 mL of Reagent 1 (prepared from 48 mL of 2% sodium carbonate in 0.1 M sodium hydroxide plus 1 mL of 1% sodium potassium tartrate plus 1 mL of 0.5% copper sulfate) was mixed with 0.2 mL of each supernatant sample, and after 15 min incubation, 0.5 mL of freshly prepared Reagent 2 (Folin Ciacalteau 1 part + 1-part DDW) was mixed and incubated for 30 min in the dark, at room temperature (25 0C). Following this, the absorbance was measured at 660 nm. The standard curve of bovine albumin (0 – 100 μg/mL) was used. The total protein content was determined as mg albumin bovine equivalent per gram fresh weight (mg BSAE g-1 FW).

2.7. Total Soluble Solids (TSS) Content and Electroconductivity (EC) Level

Sample extraction was performed as we did before (Sisay et al. 2022) with slight modifications. Briefly, 200 mg of fresh tissue was ground with liquid nitrogen and mixed with deionized distilled water (1:10 w/v). Supernatants were collected following centrifugation at 18,400 RCF for 20 minutes at 4 °C. Electrical conductivity (EC) and total soluble solids (TSS) were determined by using a standard EC meter (ECTestr 11, Eutech Instruments, Paisley, UK) and a refractometer (Atago Digital Refractometer PR-1, Tokyo, Japan), respectively. TSS and EC were expressed in % and deci-Siemens per meter (dS m−1), respectively.

2.8. Anthocyanin Contents

Anthocyanin concentrations were determined as described before (Sisay et al. 2022) with a slight modification. Frozen fresh materials (100 mg) were crushed first with liquid nitrogen and 5 mL of 1% HCl-acidified methanol [m/v: 1:7.5 (48.4 mL methanol plus 1.56 mL 32N HCL)], and thereafter centrifuged at 18,400 rcf for 20 minutes at 4 °C. 500 µl DDW was added to the 500 µl of the supernatant and 1 mL chloroform and then mixed well by vortex before centrifugation for 20 minutes at 4 °C at 18,400 rcf. The absorbance was measured at 530 nm and 657 nm. The anthocyanin contents were calculated using the following equation:

2.9. Total Polyphenol Content

Total polyphenol content was determined following the method described by Khatri and Rathore (2022) with a slight modification. Briefly, frozen fresh tissue (100 mg) was crushed, and 80% ice-cold methanol (m/v: 1:10) was added. The mixture was centrifuged at 22,500 rcf for 20 minutes at 4 °C. 0.2 mL of supernatant was mixed with 0.5 mL of Folin-Ciocalteu phenol reagent and incubated at room temperature for five minutes before mixing with 2 mL of 20% sodium carbonate. The mixture was incubated in a heated bath for five minutes at 100ºC. Absorbance was measured at 650 nm. The standard curve was prepared using catechol concentrations from 0 to 1000 µg mL−1 and the total polyphenol content reported as milligrams of catechol equivalents (CE) per gram fresh weight (mg CE g-1 FW).

2.10. Total Flavonoids

The total flavonoid content was determined using a modified method described before (Patel et al., 2022). After using liquid nitrogen to crush 100 mg of frozen fresh materials, 80% ice-cold methanol (m/v: 1:10) was added, and the mixture was centrifuged for 20 minutes at 4 °C at 22,500 rcf. 0.1 mL of the supernatant was mixed with 0.3 mL of 5% sodium nitrate, vortexed, and incubated for 5 minutes at room temperature. Subsequently, 0.3 mL of aluminum chloride (10% w/v) and 2 mL of sodium hydroxide (1M) were added and mixed. The absorbance was recorded at 510 nm. The standard curve was prepared using quercetin from 0 to 500 µg/mL−1. The results were expressed as quercetin equivalents per gram of fresh weight (mg QE g-1 FW).

2.11. Radical Scavenging Assay

The radical scavenging activity (the antioxidants in shoot’s extract) was determined using 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) as the free radical, as described before (Choudhary et al., 2023) with minor modifications. The DPPH stock solution [0.024% (w/v)] was prepared in methanol, and a working solution was made by diluting the stock solution with methanol until the absorbance reached 0.98 ± 0.02 at 517 nm. The scavenging activity of plant shoot extract was determined by adding 2 ml of DPPH solution to 100 µl plant extract (as extracted for total polyphenol content determination). The mixture was incubated for 30 min in the dark at room temperature. The absorbance was measured at 517 nm, and Trolox was used as a standard antioxidant from 0 to 100µM. The percentage of DPPH radical scavenging activity of samples was determined using the following formula:

2.12. Malondialdehyde (MDA) Content

MDA content was estimated using the colorimetric method (Hodges, et al., 1999). Samples were extracted in a 1:10 (w/v) ratio of chilled extraction buffer [1% trichloroacetic acid (TCA), 0.1 M phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) in a phosphate-buffered saline solution]. Plant extracts were divided into two sets and mixed with an equal amount of 10% TCA and 0.8% thiobarbituric acid (TBA) in 10%TCA, respectively. The extraction buffer was replaced with plant extract to create a blank reaction. Tubes were heated to 99°C for 1h, and the absorbance of the developed color was taken at 440, 532, and 600 nm. The reaction with 10% TCA acts as an additional control to remove the effect of anthocyanin and sugar complex accumulation. MDA was expressed in nanomoles per gram fresh weight (nmol g−1 FW).

2.14. Data Analysis

Representative data (of two independent experiments) are shown. Significant differences between treatments were determined using the Tukey Kramer HSD test at a 5% significance level (JMP8 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA)), n=4 to 9.

3. Results

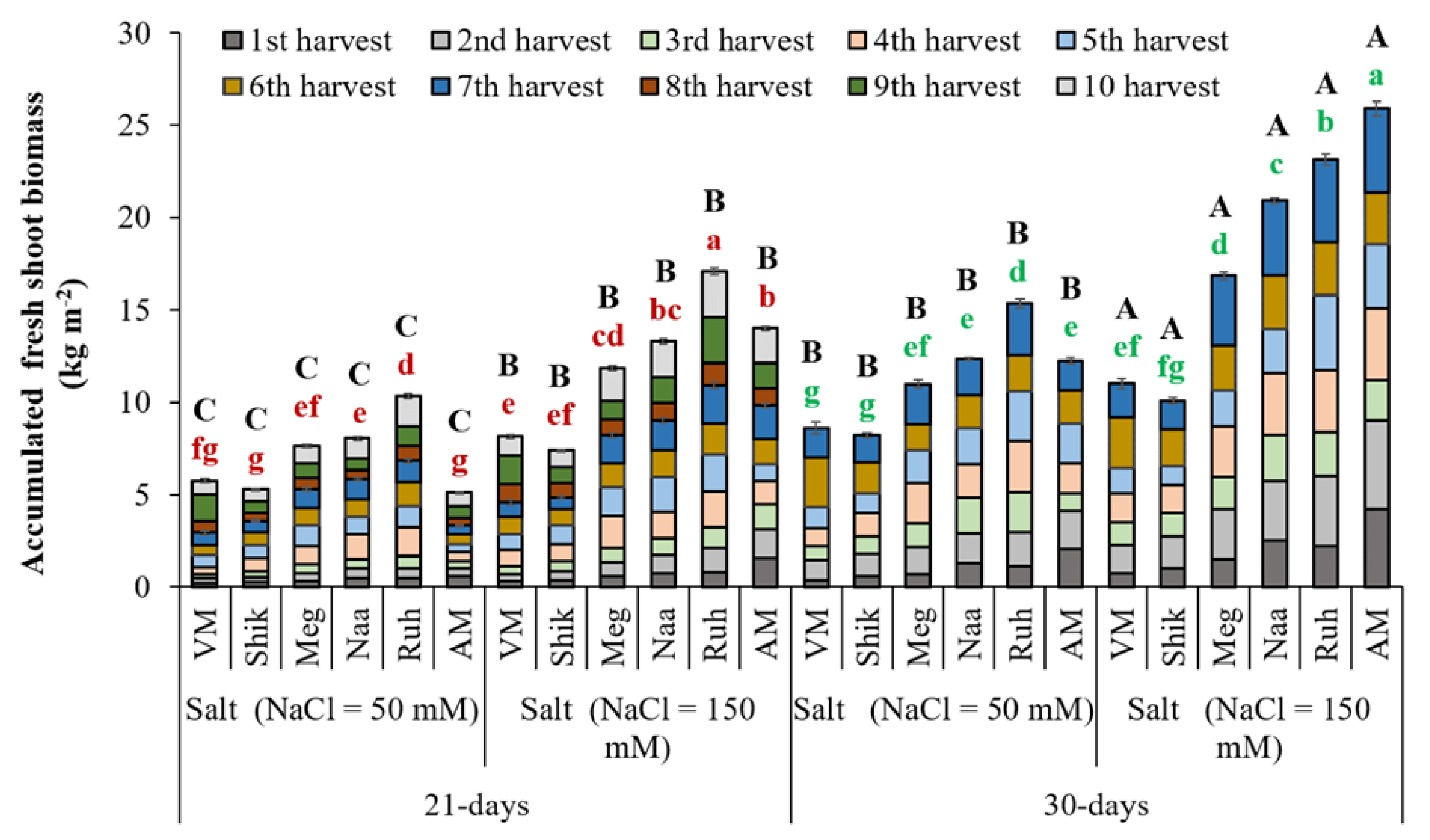

3.1. Fresh Biomass Production

In a previous study,

Sarcocornia cultivated in a hydroponic system supplied with seawater revealed that a three-week harvesting regime produced similar biomass accumulation to a two and four-week harvesting regime (Ventura et al., 2011a). In a following additional study,

Sarcocornia fruticosa ecotypes EL (not examined in the current experiment) and VM irrigated with 100 mM saline water and harvested every four weeks produced a remarkably high yield of ca 20 and 30 Kg/m

2 fresh biomass, respectively (Ventura et al., 2011b). These results indicate the utmost importance of identifying a suitable harvest regime in successively harvested halophytes exposed to various levels of saline water. Accordingly, five

Sarcocornia fruticosa and one AM ecotypes were subjected to 21-day and 30-day successive harvest intervals under two salinity treatments, resulting in ten and seven successive harvests, respectively (

Figure 1). 30-day harvesting regimes significantly increased the fresh biomass accumulation compared with 21-day harvesting regimes in both salinity treatments (50 and 150 mM). However, there was no significant difference between the 30-day harvesting intervals with lower salinity and the 21-day harvesting intervals with higher salinity.

Higher salinity (150 mM) treatments showed significantly greater yield than the lower salinity (50 mM) treatments in both harvesting regimes across all ecotypes. AM produced the highest and second-highest yield at higher and lower salinity, respectively, in the 30-day harvesting regime. In contrast, while AM still exhibited the second-best yield at the higher salinity, a significantly lower yield of AM was shown with the lower salinity treatment than the Sarcocornia ecotypes at the 21-day harvesting regimen.

Within the Sarcocornia ecotypes, Ruhama produced the significantly highest biomass accumulation within each of the four treatments [(21-days x 2 salinity levels) + (30-days x 2 salinity levels) and thereafter Naa and Meg generated as well higher biomass than VM, the currently used ecotype by the farmers.

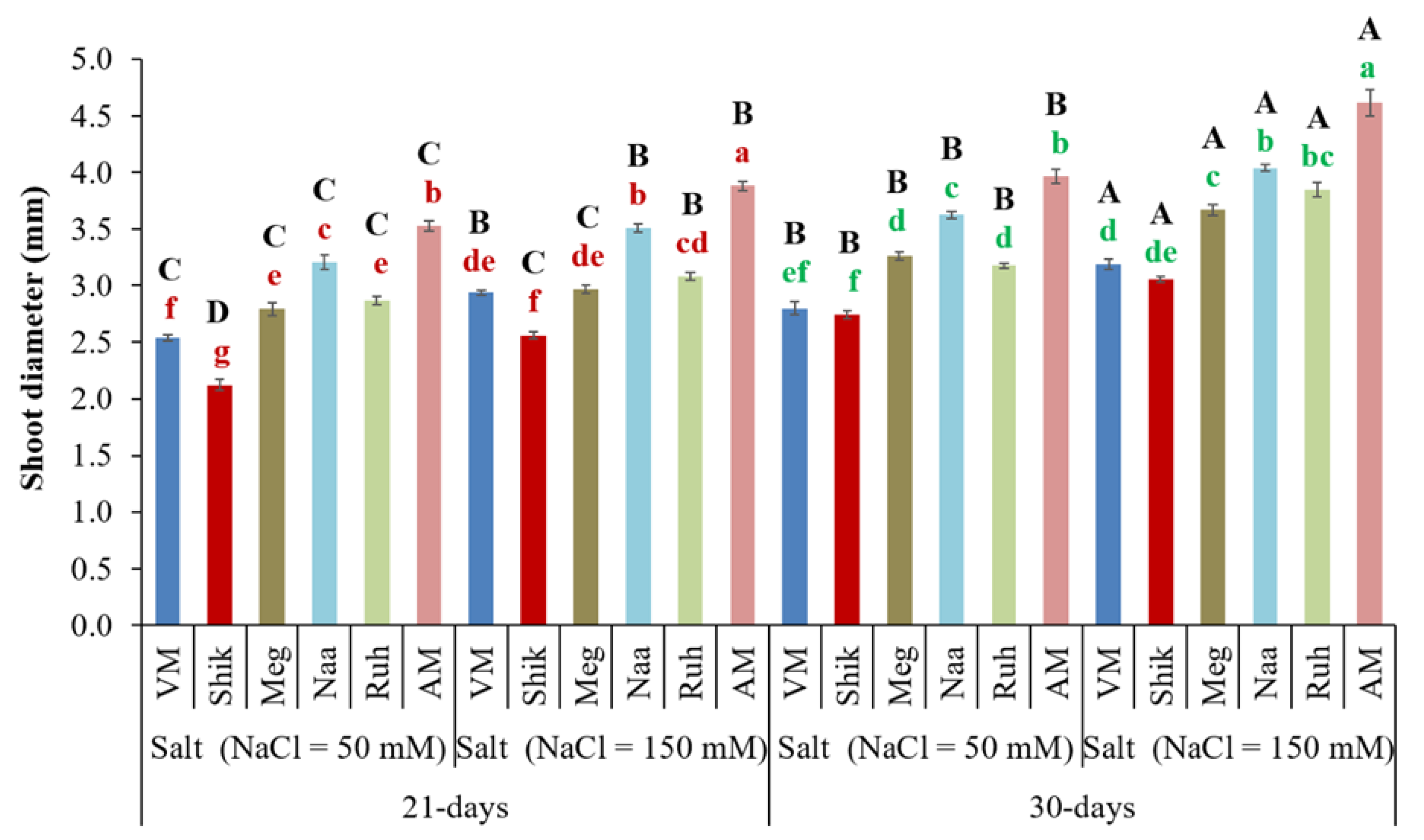

3.2. Effects of Harvesting Intervals and Salinity Levels on Plant Shoot Diameter

Shoot diameter is an indicator of product quality. The 30-day harvesting regime shows greater shoot diameter than the 21-day harvesting interval plants at both salinity treatments (

Figure 2). Notably, the higher salinity treatment significantly increased shoot diameter at both harvesting intervals compared with the lower salinity treatment. Generally, the AM ecotype had greater shoot diameter compared with

Sarcocornia ecotypes at both salinity treatments within different harvesting intervals.

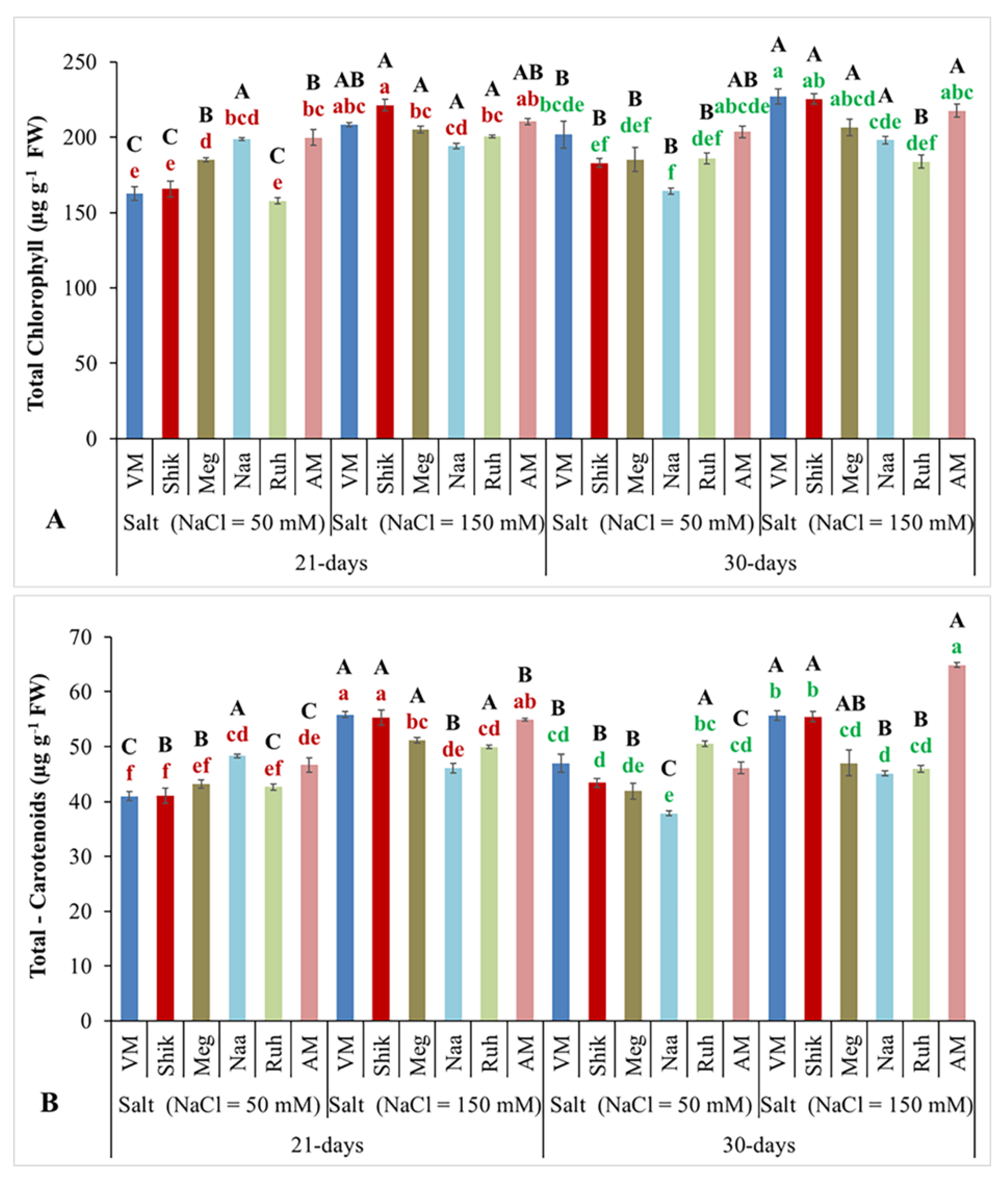

3.3. Total Chlorophyll and Carotenoid Contents

Chlorophyll and carotenoids are organic pigments with antioxidant properties (Srivastava, 2021). The impacts of salinity levels and differing harvesting intervals on total chlorophyll and carotenoid contents revealed that

Sarcocornia ecotypes and AM tended to increase total chlorophyll (

Figure 3A) and carotenoid contents (

Figure 3B) when grown under the higher salinity. Under lower salinity VM, Shik, and Ruh ecotypes displayed lower total chlorophyll contents in the 21-day harvesting regimes, while Naa had lower contents in the 30-day harvesting interval. The harvesting regimes significantly affected total chlorophyll and carotenoid contents. Total chlorophyll and carotenoid contents were highest at the 30-day harvesting intervals, particularly for VM, Shik, and Ruh in the lower salinity treatment.

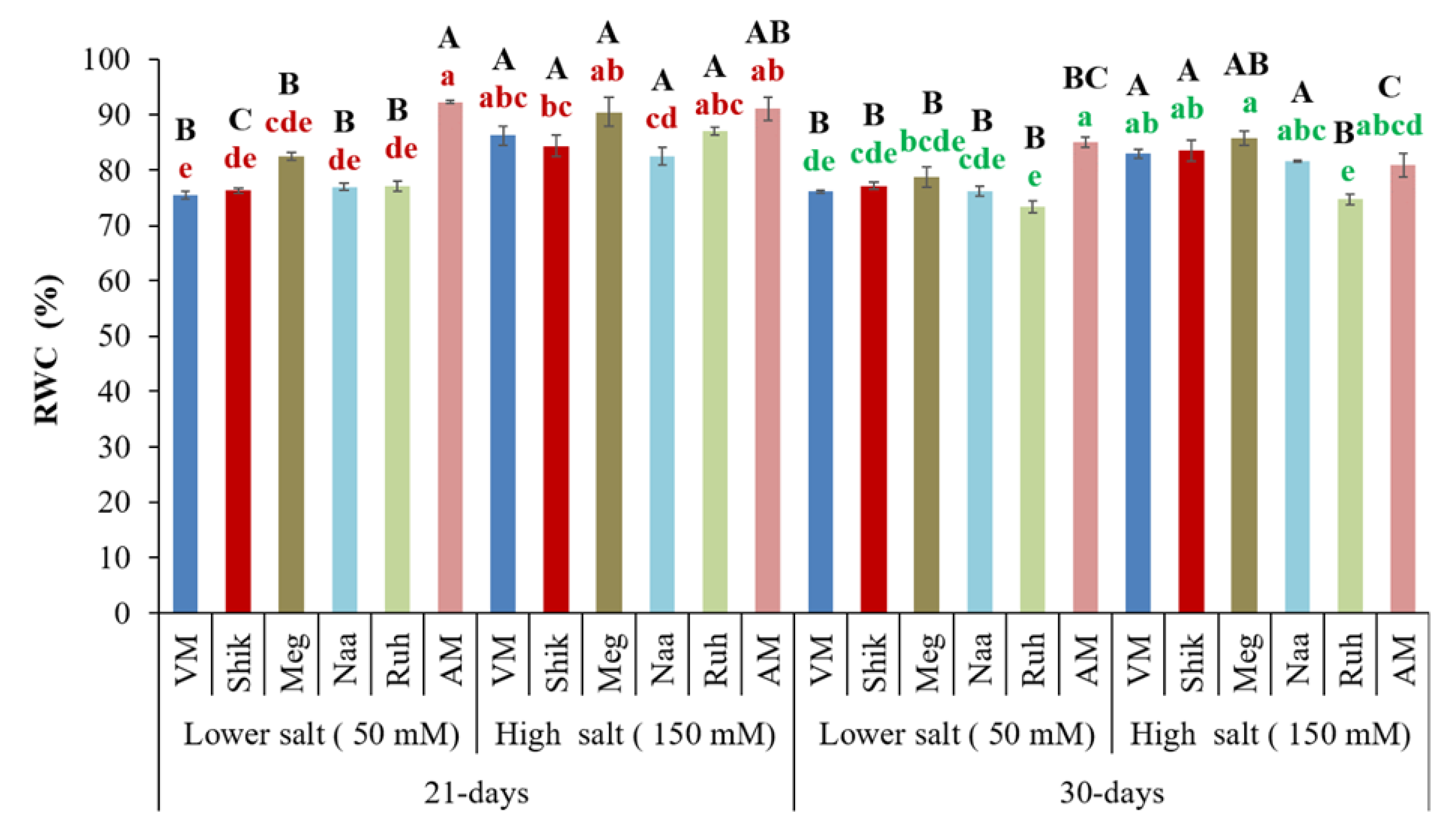

3.4. Relative Water Content (RWC)

Relative water content (RWC) indicates plant freshness and response to osmotic challenges and salinity stress. AM under the low salinity and AM and Ruh under the high salinity showed a significantly increased RWC in the 21-day harvesting treatment compared to 30-day harvesting intervals. At the same time, other ecotypes did not experience significant effects (

Figure 4). Higher salinity treatments exhibited significantly increased RWC than lower salinity treatments at both harvesting regimes, except for the AM ecotype. The Ruh ecotype had a lower RWC at 30-day harvesting intervals at the highest salinity treatments than other ecotypes and was similar to those at the lower salinity (

Figure 4).

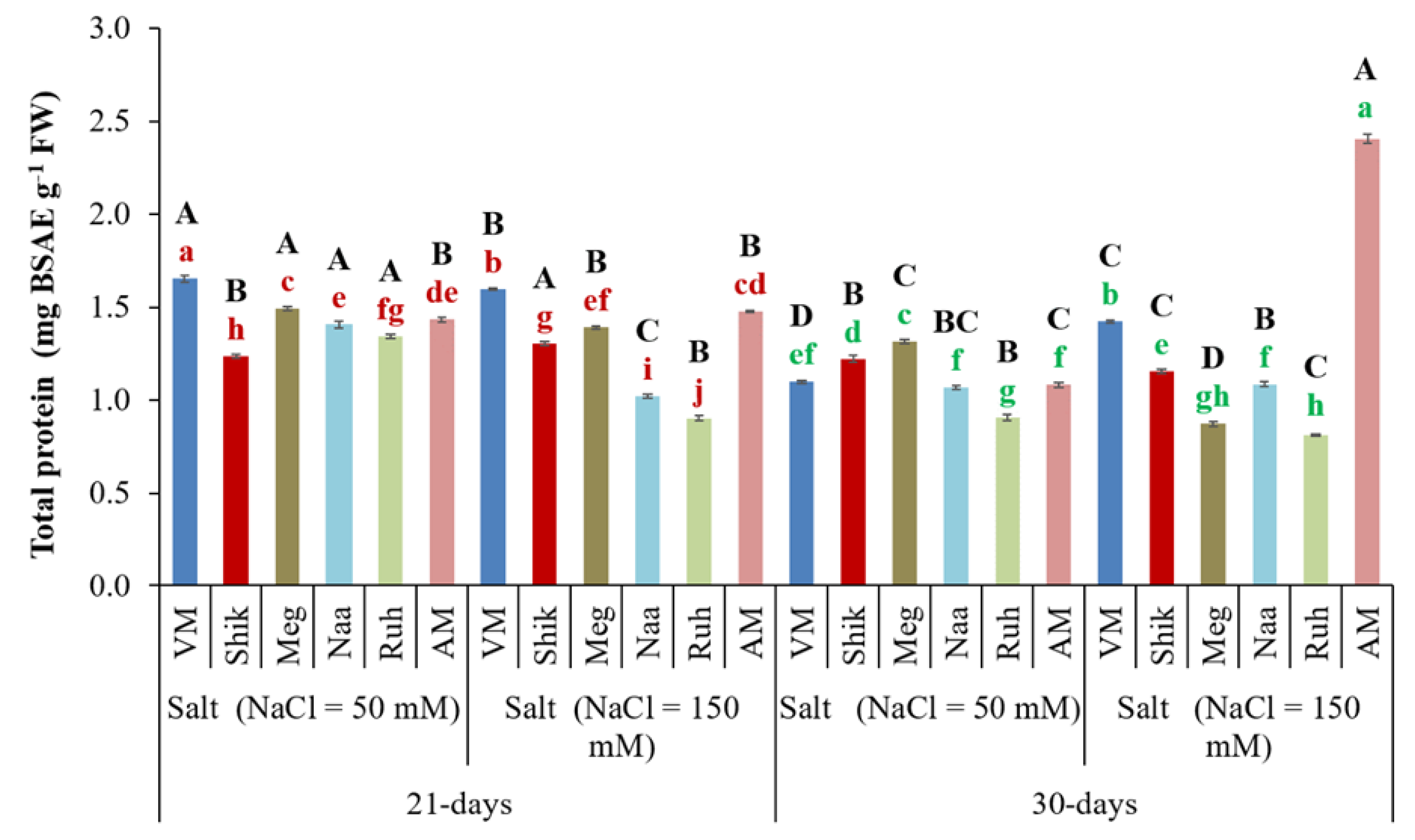

3.5. Total Protein Content

Proteins are necessary for plant growth and are markers of health and development (Pincus, 2001). The total protein content in AM plant tissue at the 30-day harvesting regime under high salinity significantly increased compared to the 21-day harvesting regime (

Figure 5). In contrast,

Sarcocornia ecotypes exhibited higher total protein content at the 21-day harvesting interval compared to the 30-day interval at both salinity treatments. Growth under lower salinity treatments notably significantly increased total protein content for VM, Meg, Naa, and Ruh ecotypes at both harvesting intervals compared to higher salinity treatments. In contrast, the Shik ecotype exhibited a higher protein level under the higher salinity treatment at the 21-day harvesting interval (

Figure 5).

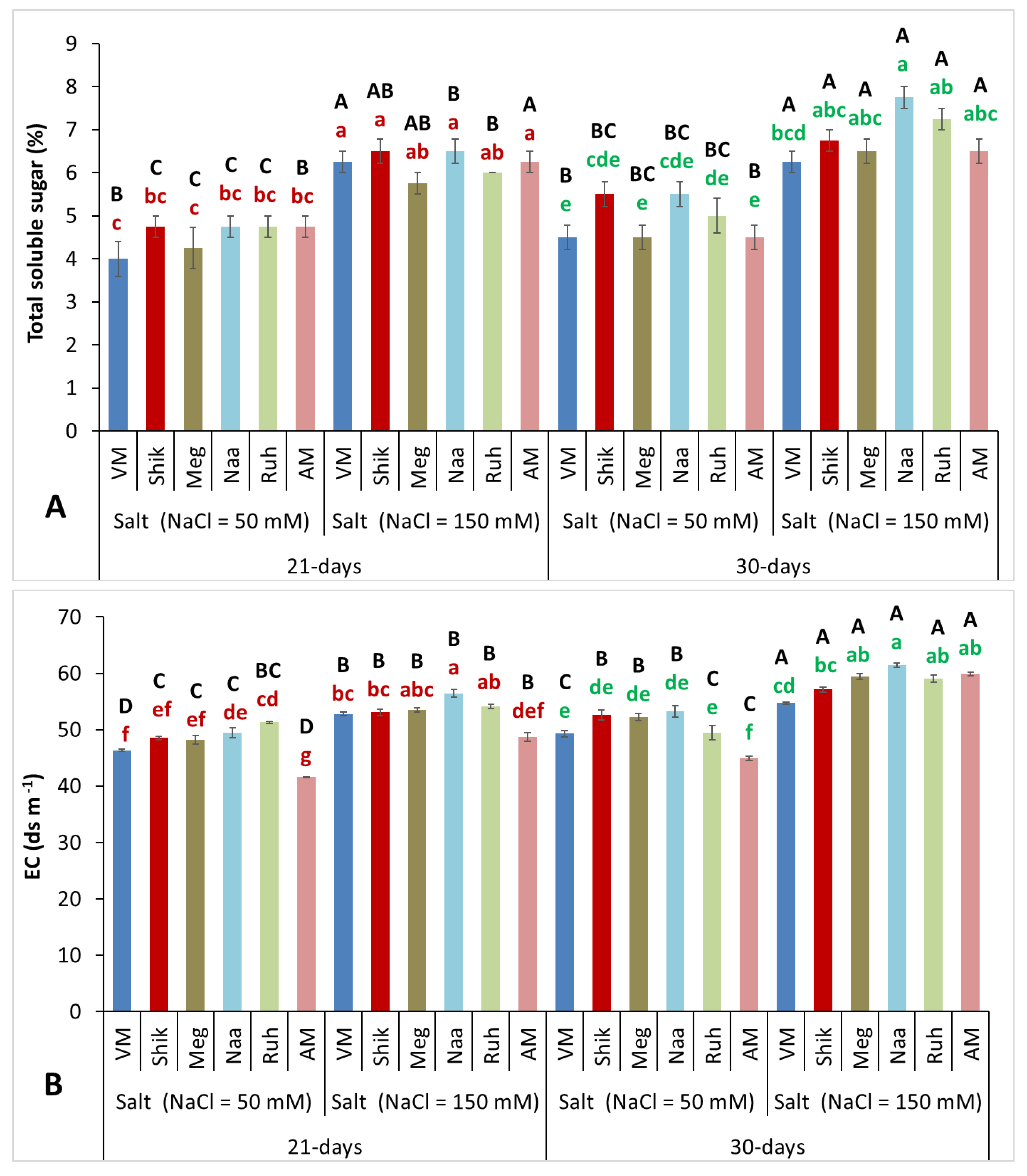

3.6. Total Soluble Sugar and Electroconductivity Contents

The increase in total soluble sugars (TSS) and electroconductivity content in plant tissue is presumably a response to increasing salinity, acting as an osmo-protective mechanism balancing the increased salt uptake, and likely serving as an osmotic adjustment mechanism in response to enhanced salinity (Sisay et al., 2022 and references therein). Indeed, the higher salinity (150 mM) treatments significantly increased TSS contents and EC levels compared with lower salinity (50 mM) treatments at both 21- and 30-day harvest intervals. The prolonged growth duration promoted greater TSS accumulation only in Ruh and Naa grown with the higher salinity, yet higher EC level in AM and

Sarcocornia ecotypes, suggesting superior osmotic adjustment capacity and better adaptation to a saline environment stress (

Figure 6A,B).

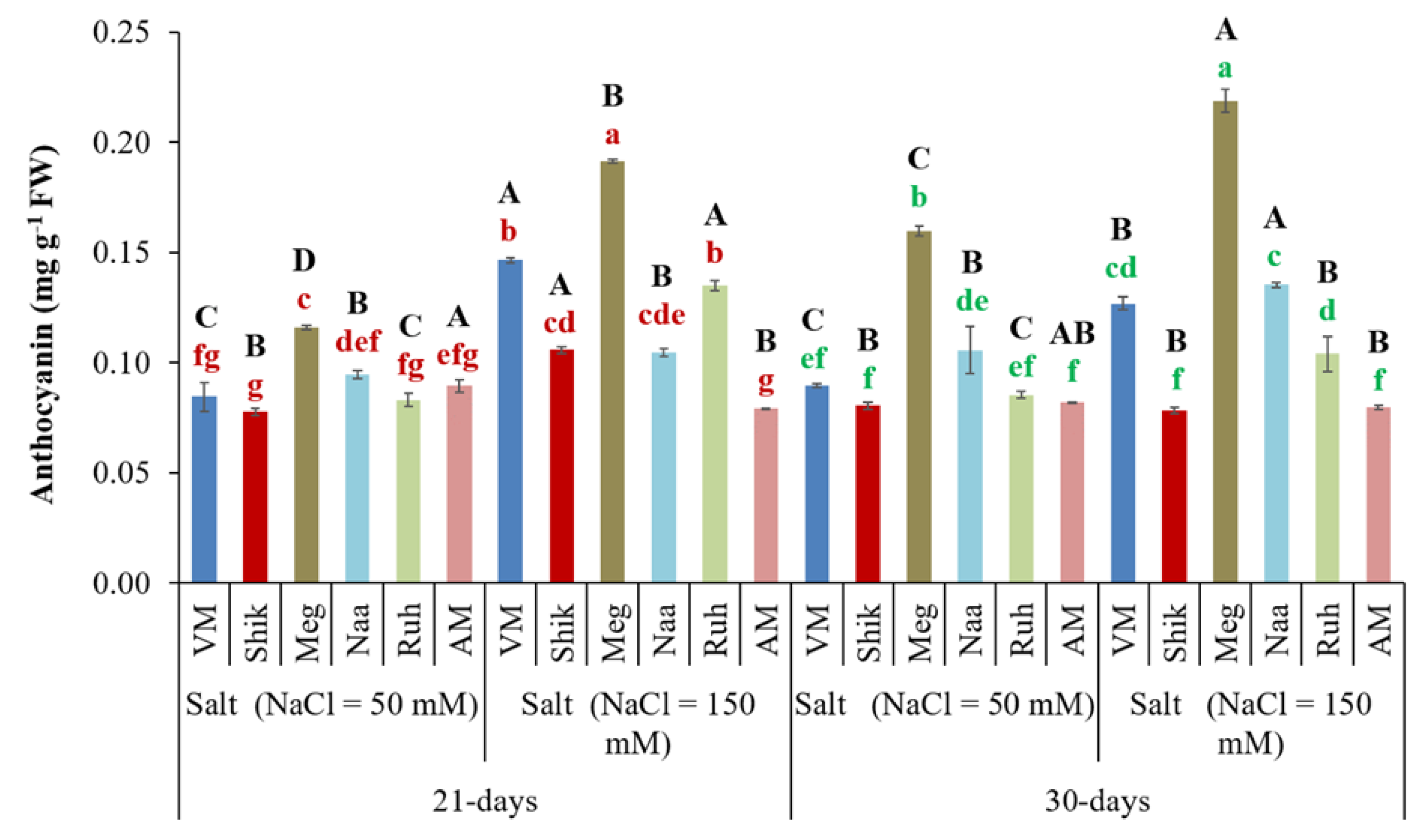

3.7. Anthocyanin Content

Abiotic stresses such as salinity may result in oxidative stress and ROS production, which triggers anthocyanin production, used to scavenge ROS in order to ameliorate osmotic damage to cells (Sisay et al., 2022 and references therein). Interestingly, the VM, Shik, and Ruh ecotypes showed significantly greater anthocyanin accumulation in the high salinity treatment of the 21-day-harvested regime compared to the 30-day treatments. Higher salinity, with both harvesting regimes, except for the AM ecotype, significantly increased the anthocyanin accumulation compared with lower salinity treatments. Meg exhibited the highest anthocyanin accumulation at higher salinity treatments within the 30-day and 21-day harvesting regimes, with a significantly lower level in the shorter harvest period than in the more extended harvesting period (

Figure 7).

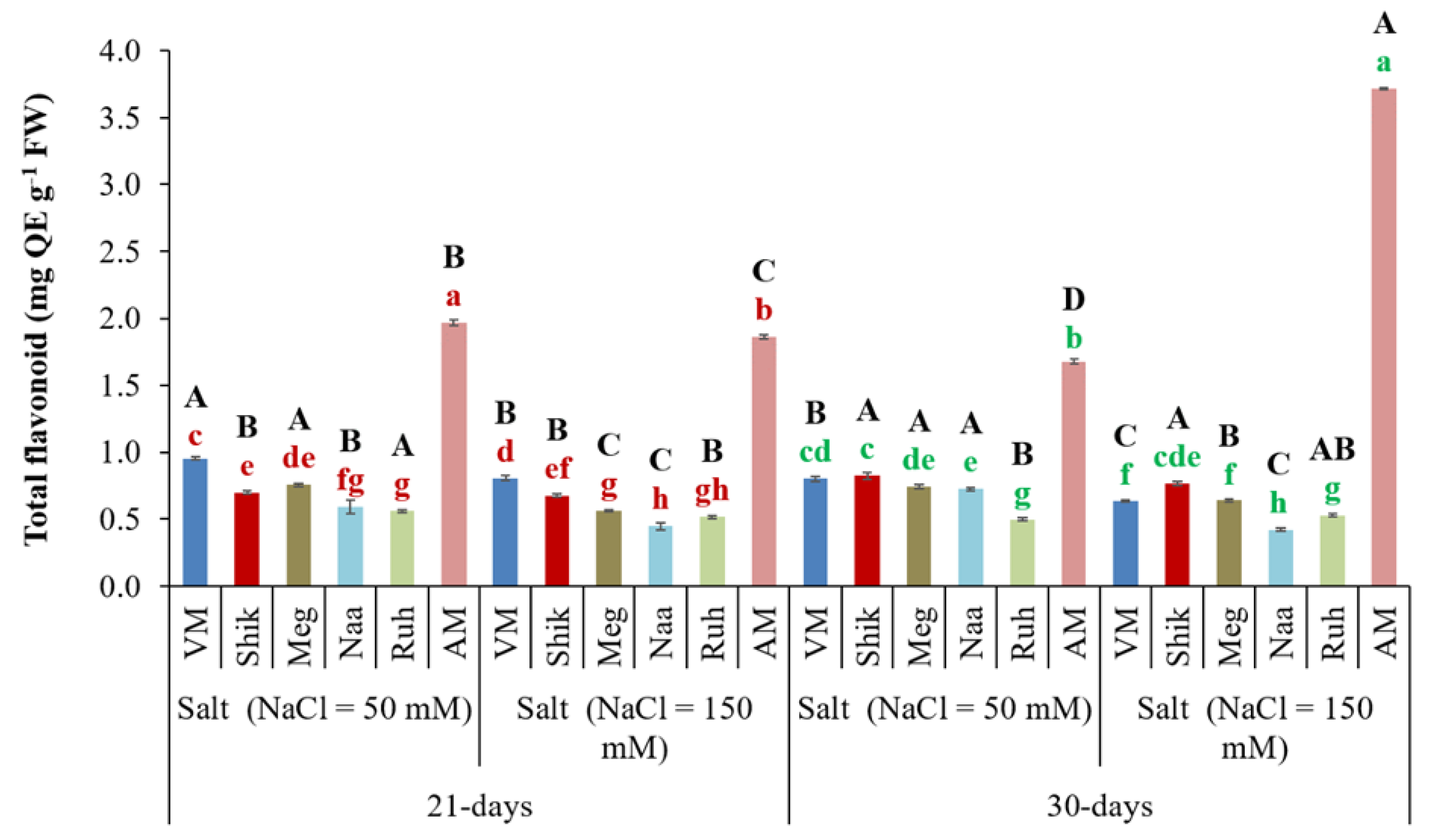

3.8. Total Flavonoid Content

Flavonoids are part of a large family of phenolic or polyphenol compounds and are synthesized in several plant parts that exhibit a high antioxidant capacity. Flavonoids play an important role in plant stress tolerance and are highly relevant to human health due to their anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties (Dias et al., 2021). AM exhibited significantly higher total flavonoid contents than the Sarcocornia ecotypes across salinity and harvesting regime treatments, the highest at the 30-day harvest regime irrigated with high salinity. Among the Sarcocornia ecotypes, Ruh and Naa tended to generate the lowest level in each of the four treatment combinations (two salinity levels versus two harvest regimes).

Figure 8.

The impact of 21-day and 30-day harvesting intervals on total flavonoid levels in the shoots of Sarcocornia ecotypes VM, Shikmona (Shik), Megadim (Meg), Naaman (Naa), Ruhama (Ruh), and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum (AM). Sodium Chloride in supplied water was at two levels (50 and 150 mM). The means plus standard error (+SE) are shown. Different uppercase letters indicate a significant difference between the same ecotypes across various harvesting intervals and salinity levels. Lowercase letters represent significant differences among the various ecotypes within the same harvesting interval and under different salinity treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p ≤ 0.05, n = 6). Representative data (of two independent experiments) is shown.

Figure 8.

The impact of 21-day and 30-day harvesting intervals on total flavonoid levels in the shoots of Sarcocornia ecotypes VM, Shikmona (Shik), Megadim (Meg), Naaman (Naa), Ruhama (Ruh), and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum (AM). Sodium Chloride in supplied water was at two levels (50 and 150 mM). The means plus standard error (+SE) are shown. Different uppercase letters indicate a significant difference between the same ecotypes across various harvesting intervals and salinity levels. Lowercase letters represent significant differences among the various ecotypes within the same harvesting interval and under different salinity treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p ≤ 0.05, n = 6). Representative data (of two independent experiments) is shown.

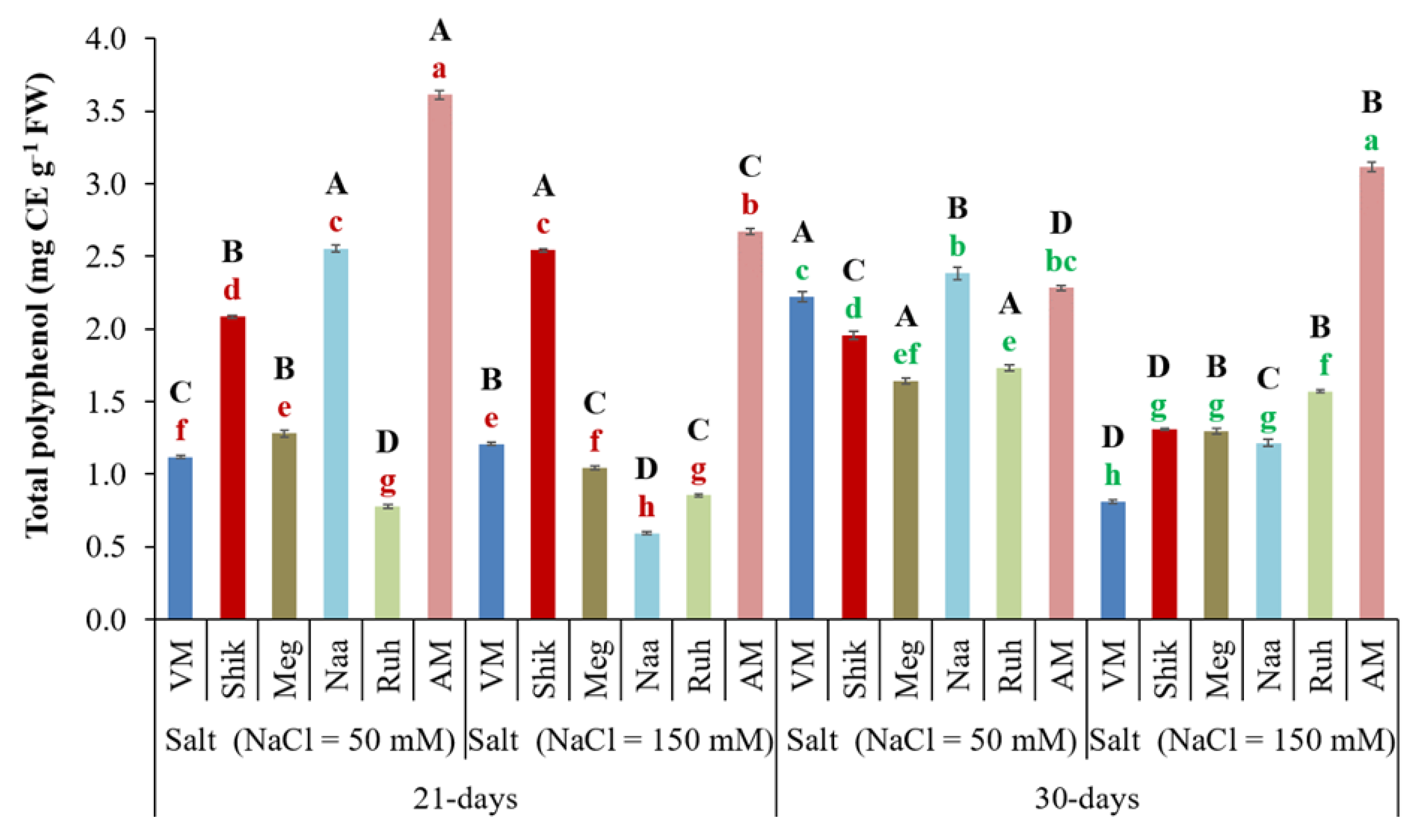

3.9. Total Polyphenol Content

Plants typically respond to abiotic stressors such as salt and drought by increasing the synthesis and accumulation of polyphenols, which help defend against ROS enhancement and neutralize free radicals (Ksouri et al., 2008). Analysis of shoot total polyphenol content revealed that VM, Meg, and Ruh ecotypes grown under low salinity significantly increased total polyphenol content under a 30-day harvesting regime compared to the 21-day regime. In contrast, Naa and Shik ecotypes exhibited higher total polyphenol content under low salinity at the 21-day harvesting intervals (

Figure 9). Significantly, at the 30-day harvest regime,

Sarcocornia ecotypes accumulated higher total polyphenol content at low salinity than at the higher salinity conditions. As for the AM, except for a similar level to Naa and VM at low salinity under a 30-day harvest regime, the AM ecotype exhibited the highest total polyphenol content compared to the

Sarcocornia ecotypes across salinity and harvesting regime treatments (

Figure 9).

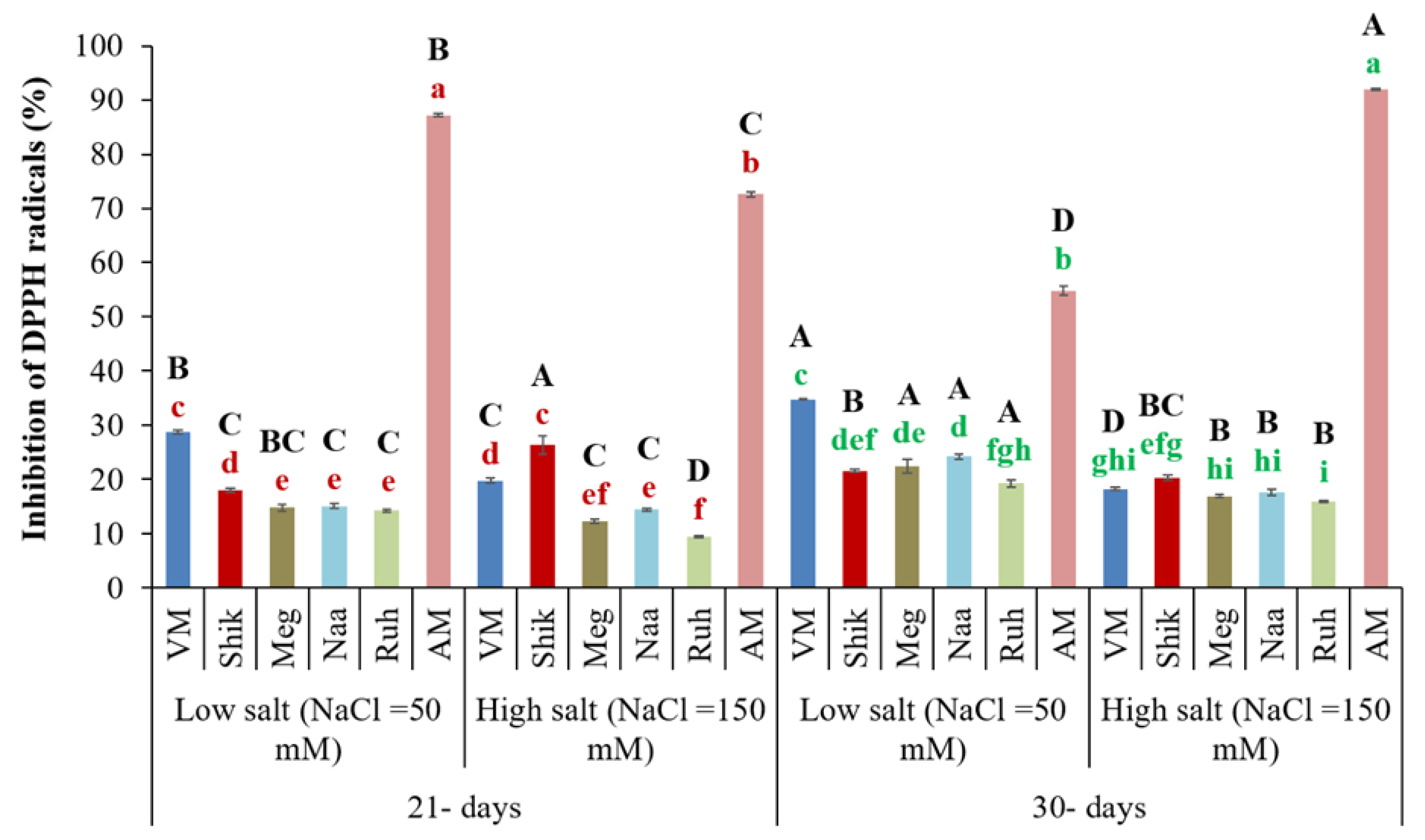

3.10. Radical Scavenging Activities Using 2,2-Diphenyl-1-Picrylhydrazyl (DPPH)

The radical scavenging activity of 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) is a commonly used antioxidant assay to estimate antioxidant capacity to neutralize the ROS-induced damage (Choudhary et al., 2023, and references therein). Under the 30-day harvesting regime,

Sarcocornia ecotypes plants showed significantly enhanced radical scavenging activity compared to 21-day harvesting regimes across both salinity treatments, except for Shik and VM, which showed enhanced inhibition of radicals at high salinity under the 21-day harvest regime (

Figure 10). The effect of low salinity treatments, except for Shik ecotype, notably increased the free radical scavenging activity in

Sarcocornia (VM, Meg, Naa, and Ruh) ecotypes in both harvest regime intervals. In contrast, AM significantly increased at higher salinity with 30-day harvesting intervals, followed by lower salinity treatment at the 21-day harvesting interval. Significantly, the AM ecotype exhibited the highest scavenging activity compared to the other

Sarcocornia ecotypes across harvesting regimes and salinity treatments (

Figure 10).

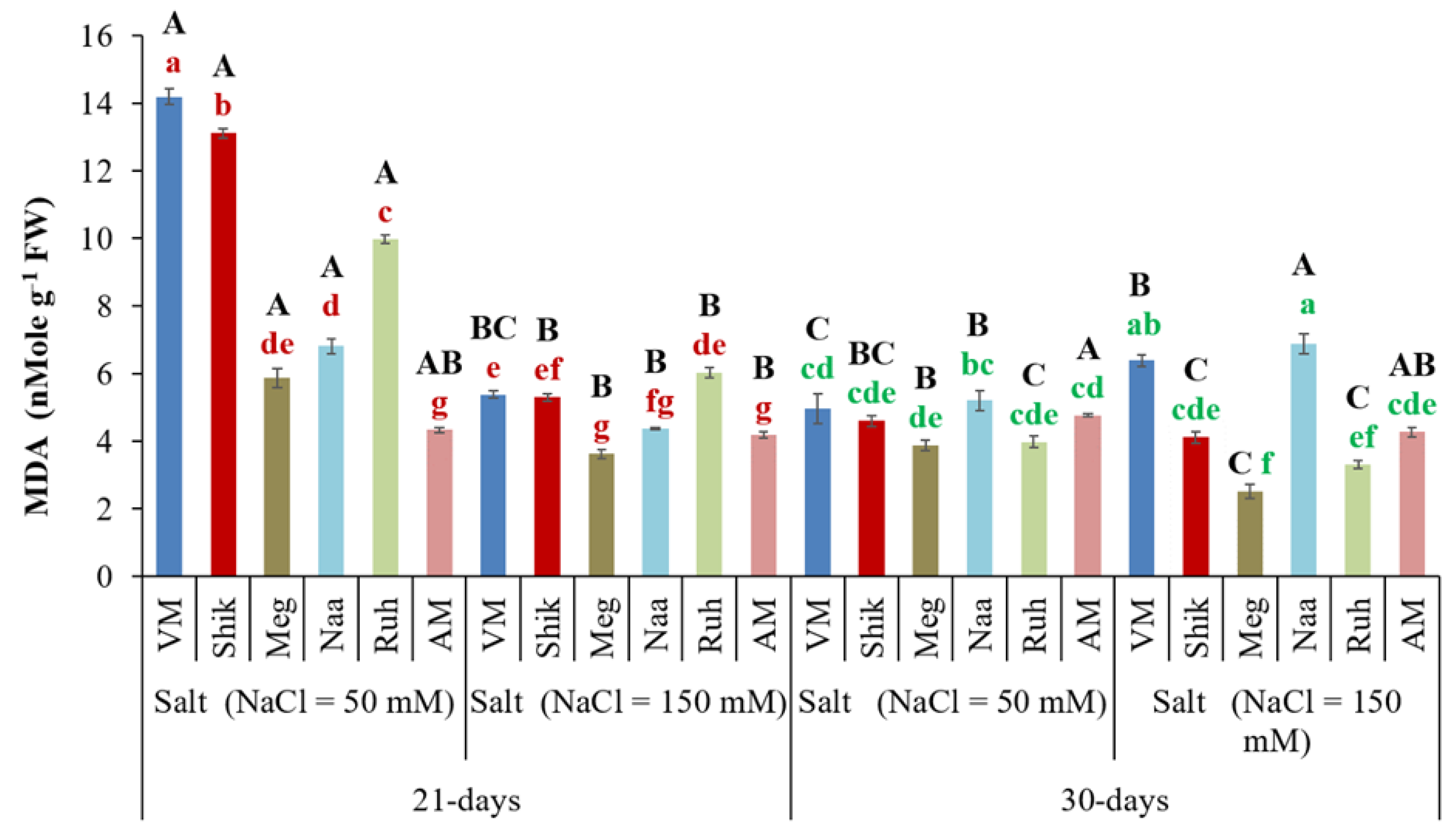

3.12. Malondialdehyde (MDA) Content

MDA is a toxic carbonyl aldehyde resulting from lipid peroxidation by prolonged oxidative stress, and is a stress marker in plants, with increased MDA content indicating higher stress levels (Soltabayeva et al., 2022). Plants grown at low salinity under 21-day harvest regime had significantly higher MDA levels than plants grown with high salinity under 21-day and 30-day harvesting regimes under both salinity levels. This was particularly noticeable in the VM, Shik, Megadim, and Ruh ecotypes. In contrast, AM exhibited lower MDA than the

Sarcocornia ecotypes exposed to the low salinity at the short harvest regime and generally was similar to the Sarcocornia ecotypes at the other treatments (

Figure 11).

4. Discussion

4.1. Growth Responses

The current study compared the yield of new Sarcocornia fruticosa ecotypes (Shik, Meg, Naa, and Ruh) to the current used ecotype (VM), as well as to the Arthrocnemum macrostachyum (AM), phenotypically similar to Sarcocornia. The effect of 21-day and 30-day successive harvesting intervals on the yield of plants exposed to 50 or 150 mM NaCl was examined.

Multiple harvesting in perennial crops is advantageous, enhancing crop yield and enabling year-round vegetable supply (Ventura & Sagi, 2013). These regimes are designed to ensure consistently high-quality products, as only young, re-growing shoots are harvested (Ventura et al., 2011a). Sarcocornia ecotypes and AM, as perennials, are well-suited for multiple harvest regimes due to their extended periods without flowering, while the market value of Salicornia can be influenced by varying day lengths, inducing shoot flowering unsuitable as a vegetable crop (Sisay et al., 2022; Ventura et al., 2011b).

In previous studies,

Sarcocornia cultivated in a hydroponic system supplied with complete seawater revealed that a three-week harvesting regime produced similar biomass accumulation to a two and four-week harvesting regime (Ventura et al., 2011a). The current study demonstrated that over 210 days, harvesting seven times (every 30 days) produced greater biomass than harvesting ten times (every 21 days) (

Figure 1).

Additionally, at each harvest regime, the higher salinity levels (150 mM NaCl) enhanced plant growth and therefore fresh biomass production, compared to the lower salinity level (50 mM) (

Figure 1). Similarly, harvesting every 30 days produced greater shoot diameter than harvesting every 21 days, and the higher salinity levels also enhanced shoot diameter compared to the lower salinity level (

Figure 2), supporting both yield and quality improvement.

The results indicate that longer harvesting intervals (30 days) and higher salinity concentrations generally enhanced plant productivity across salinity and harvesting intervals in both AM and

Sarcocornia ecotypes. Specifically, the growth responses indicate that Meg, Naa, Ruh, and AM better responded to the higher salinity than VM and Shik. At the same time, AM accumulated the highest biomass and shoot diameter under the longer harvest regime (30 days). In contrast, lower salinity treatments reduced plant growth, yield, and shoot diameter, especially in AM grown under the shorter harvest interval [21 days (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2)].

Importantly, these results are supported by studies on other halophyte types such as Sarcocornia fruticosa, Salicornia bigelovii, Salicornia persica, and Atriplex halimus, demonstrating that moderate salinity promoted growth, while lower salinity (50 mM) or too high salinity levels (600 mM) caused stress that limited growth (Aghaleh et al., 2009; Ibraheem et al., 2025; Ventura et al., 2011a; Kong & Zheng, 2014; Salazar et al., 2024). Moderate salinity levels improve osmotic adjustment and ion compartmentalization, which support metabolic activity and plant growth, but excessive salinity causes oxidative stress, ion toxicity, and reduced nutrient uptake (Ibraheem et al., 2025; Yang et al., 2008).

4.2. Photosynthetic Pigments

Photosynthetic pigments such as chlorophyll are crucial for photosynthesis, as they absorb light energy and convert it into chemical energy (Mandal & Dutta, 2020; Tan et al., 2020). In saline environments, decreased chlorophyll levels indicate salt stress, which reduces chlorophyll synthesis and accelerates degradation (Jameel et al., 2024; Taïbi et al., 2016). Chlorophyll degradation, often a photoprotection mechanism, reduces the ability of plants to absorb light (Türkan & Demiral, 2009), while chlorophyll activity is a key indicator of plant health, supporting photosynthetic processes, nutrient cycling, and stress adaptation (Pavlovic et al., 2014; Talebzadeh & Valeo, 2022). The current study revealed a significant difference in total chlorophyll concentrations between 21-day and 30-day harvesting regimes across VM, Shik, and Naa ecotypes at lower salinity but no significant difference at higher salinity treatments. Higher salinity treatments increased chlorophyll content compared to lower salinity treatments (

Figure 3A). These results are consistent with other studies (Kumar et al., 2021 Rabhi et al., 2012 Shah et al., 2017; and Ventura et al., 2011a), who observed increased chlorophyll content with increasing salinity in halophytes and wheat plants.

The accumulation of the photosynthetic pigment anthocyanin is a key response to abiotic stress, with roles in osmoregulation, signaling, and photoprotection (Dabravolski & Isayenkov, 2023; Li & Ahammed, 2023). As such, plants produce anthocyanins in response to salinity stress (Kovinich et al., 2014; Maduraimuthu et al., 2004), and the level in leaves is closely associated with the ability to tolerate salt stress (Maduraimuthu et al., 2004). While salt-tolerant plants may generate anthocyanins in smaller quantities due to different defense mechanisms, higher levels of anthocyanins can help protect salt-sensitive plants from oxidative stress (Hurkman et al., 1989). The current study showed increased anthocyanin concentrations in the Meg ecotype under higher salinity at both harvest regimes, being higher under the 30-day harvest. In contrast, VM, Shik, and Ruh ecotypes exhibited increased anthocyanin levels under higher salinity during the 21-day harvesting regime (

Figure 7). These results are consistent with other studies, which observed increased anthocyanin content with increasing salinity (Jameel et al., 2024; Sisay et al., 2022). AM exhibited lower anthocyanin contents than the

Sarcocornia ecotypes, but showed increased anthocyanin concentrations under the 21-day regime at lower salinity (

Figure 7), indicating that lower salinity is likely stressful for AM.

Carotenoids are vital non-antioxidants in protecting plants against salinity and photo-oxidative stress damage, while enhancing photosynthetic performance through improved light harvesting and energy transfer (Collini, 2019; Croft & Chen, 2017; Demmig-Adams & Adams, 2002). The current study revealed a significant difference in total carotenoid concentration between 21-day and 30-day harvesting regimes across VM, Naa, and Ruh ecotypes at lower salinity, but no significant difference at higher salinity treatments. Carotenoid levels increased under higher salinity in both harvesting regimes under 21 and 30 days (

Figure 3B). These results align with other studies reporting that carotenoid levels rise in response to enhanced salinity in various halophytes as well as wheat plants to protect (Jameel et al., 2024; Rabhi et al., 2012; Sarker and Oba, 2019; Shah et al., 2017; Ventura et al., 2014).

4.3. Relative Water Content

RWC is a key metric of plant hydration and can indicate plant response to salinity stress. Increased RWC indicates osmolyte accumulation and stable water content, while a decrease signals drought stress (Ben-Amotz et al., 1988; Sisay et al., 2022). Halophytes typically increase RWC in response to higher salinity to mitigate stress and maintain osmolyte balance (Parida et al., 2016). The study indicates that RWC significantly increased at higher salinity treatments under both harvesting regimes. Lower salinity treatments decreased RWC, particularly in the AM, which showed a significant increase in RWC under the 21-day harvesting regime compared to the 30-day regime. In contrast, no significant RWC differences between harvesting regimes were noticed in the

Sarcocornia ecotypes (

Figure 4). Parida et al. (2016) and Sisay et al. (2022) also reported increased RWC in halophyte ecotypes under higher salinity conditions, attributed to the enhanced water uptake at elevated salinity levels, osmoregulatory adjustments, and the activation of osmoreceptors.

The higher salinity treatment significantly increased TSS content and EC level in

Sarcocornia ecotypes and AM at 21-day and 30-day harvesting intervals (

Figure 6A,B). Notably, Sarcocornia ecotypes and AM significantly increased TSS under higher salinity treatments than the lower ones, while the harvesting interval had no significant effect on total soluble sugar content, except for the Naa and Ruh ecotypes, which exhibited significantly higher TSS levels at the 30-day interval compared to the 21-day interval (

Figure 6). These results indicate an advantage of Naa and Ruh compared to the other

Sarcocornia ecotypes under these growth conditions and a potential adaptive response to prolonged exposure to salinity stress at the higher salinity level during plant growth.

Stress-associated protein biosynthesis is induced by salinity and environmental stresses such as drought and mineral nutrient levels in saline environments(Ali, 1999). The increased protein content contributes to osmotic adjustment, helping plants maintain cellular homeostasis. Some of these proteins are newly synthesized as a direct response to salt stress, while others are constitutively present at low levels and become upregulated upon exposure to salinity (Ashraf & Harris, 2004; Pareek,1997). The current study indicated that the AM ecotype protein content significantly increased under a 30-day harvesting interval at higher salinity stress than at lower salinity. In contrast,

Sarcocornia ecotypes had higher protein contents at lower salinity treatments under 21-day harvesting intervals compared with higher salinity and 30-day harvesting intervals (

Figure 5), likely indicating the different capacity between AM and

Sarcocornia ecotypes in growth at low salinity.

4.4. Antioxidant Responses

Environmental factors such as drought, waterlogging, wounding, UV irradiation, and mineral nutrient levels in saline environments induce oxidative stress by producing ROS, which can damage plant cells and disrupt metabolic activity. (Soltabayeva et al., 2022; Sagi et al., 2004; Kumar et al., 2021). MDA is a biomarker of oxidative stress, indicating the extent of lipid peroxidation and ROS damage (Patel et al.,2025; Mohammadi et al., 2015). Lower MDA levels indicate higher tolerance to environmental stress, such as salinity, while higher levels suggest sensitivity. The current study shows that MDA levels were highest under lower salinity treatments in AM and Sarcocornia, especially for the VM and Shik ecotypes under the 21-day harvesting regime. Sarcocornia ecotypes exhibited higher MDA levels than AM ecotypes across salinity levels and harvesting regimes, indicating that AM is more salinity-stress-tolerant than Sarcocornia.

Radical scavenging activity serves as a crucial defense mechanism under various stress conditions, and it plays a vital role in neutralizing reactive oxygen species that contribute to lipid peroxidation and abiotic stress effects (Harboub et al., 2025). The current study shows that the radical scavenging activity, detected by DPPH inhibition, significantly increased at both salinity levels at the 30-day harvesting interval. Except for the Shik ecotype, all other

Sarcocornia ecotypes exhibited a generally higher (or similar) level of DPPH inhibition under lower salinity conditions. As with Flavonoids (

Figure 8), the AM ecotype demonstrated the highest level of DPPH inhibition compared to the

Sarcocornia ecotypes at the high and low salinity levels and harvesting intervals (

Figure 10). Accordingly, the level of DPPH inhibition was significantly increased in AM under high salinity at the 30-day harvesting interval, followed by an increase at the 21-day harvesting interval under lower salinity, indicating a role of Flavonoids in the level of DPPH inhibition at least in AM (

Figure 8 and

Figure 10).

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study highlights the significant effects of harvesting intervals and salinity levels on the yield and nutritional value of Sarcocornia fruticose ecotypes and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum (AM).

30-day successive harvesting over a 210-day growth increased Sarcocornia and AM yield compared to 21-day harvesting at both salinity levels examined (50 and 150 mM NaCl). It also tended to improve electrical conductivity and total soluble sugar, lower the toxic stress marker malondialdehyde, and enhance radical inhibition activity in most Sarcocornia ecotypes.

Compared to VM, the other Sarcocornia ecotypes, Ruh and Naa, exhibited much higher biomass with generally similar radical inhibition activity but lower total protein content. The higher salinity improved fresh biomass, shoot diameter, relative water content, chlorophyll level, TSS, EC, and tended to increase anthocyanin and carotenoid levels. In contrast, the lower salinity tended to increase total flavonoid, polyphenol, and radical inhibition activity in the Sarcocornia ecotypes.

Significantly, AM outperformed both VM and the new Sarcocornia ecotypes (Shik, Meg, Naa, and Ruh) in biomass and productivity at higher salinity levels and 30-day harvesting intervals and exhibited higher radical scavenging activity.

These findings highlight the importance of optimizing harvesting regimes and salinity concentration management to improve yield and quality in such halophytic plants, with potential implications for sustainable agricultural practices in saline water and saline soil environments.

Author Contributions

TAS and DS conceived the idea, participated in designing the research plans, performed the experiments, and analyzed the data; MS and LMBC participated in conceiving the idea. TAS, DS, JP, KK, BC, and IG participated in methodology; TAS, JP, KK, DS, ZDN, and BC participated in preparing plant material; SAGI conceived the idea, designed the research plan, and supervised the research work. TAS, DS, and SAGI wrote and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Work funded by the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) and the Portuguese National Budget (bilateral project, Portugal/Israel, PT-IL/0003/2019, and UIDB/04326/2020 project). Part of the work was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (grant agreement no.820906).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

- Abdel Latef, A. A. H., & Chaoxing, H. (2014). Does Inoculation with Glomus mosseae Improve Salt Tolerance in Pepper Plants? Journal of Plant Growth Regulation, 33(3), 644–653. [CrossRef]

- Aghaleh, M., Niknam, V., Ebrahimzadeh, H., & Razavi, K. (2009). Salt stress effects on growth, pigments, proteins and lipid peroxidation in Salicornia persica and S. europaea. In BIOLOGIA PLANTARUM (Vol. 53, Issue 2).

- Agudelo, A., Carvajal, M., & Martinez-Ballesta, M. D. C. (2021). Halophytes of the mediterranean basin—underutilized species with the potential to be nutritious crops in the scenario of the climate change. Foods, 10(1). [CrossRef]

- Ali, G., Srivastava, P.S. and Iqbal, M., (1999). Proline accumulation, protein pattern, and photosynthesis in Bacopa Monniera regenerants grown under NaCl stress. Biologia Plantarum, 42, pp.89–95.

- Antunes, M. D., Gago, C., Guerreiro, A., Sousa, A. R., Julião, M., Miguel, M. G., Faleiro, M. L., & Panagopoulos, T. (2021). Nutritional characterization and storage ability of salicornia ramosissima and sarcocornia perennis for fresh vegetable salads. Horticulturae, 7(1), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M., & Harris, P. J. C. (2004). Potential biochemical indicators of salinity tolerance in plants. In Plant Science (Vol. 166, Issue 1, pp. 3–16). Elsevier Ireland Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Barreira, L., Resek, E., Rodrigues, M. J., Rocha, M. I., Pereira, H., Bandarra, N., da Silva, M. M., Varela, J., & Custódio, L. (2017). Halophytes: Gourmet food with nutritional health benefits? Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 59, 35–42. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Amotz, A., Lers, A. and Avron, M., (1988). Stereoisomers of β-carotene and phytoene in the alga Dunaliella bardawil. Plant physiology, 86(4), pp.1286-1291.

- Boughalleb, F., & Denden, M. (2011). Physiological and Biochemical Changes of Two Halophytes, Nitraria retusa (Forssk.) and Atriplex halimus (L.) Under Increasing Salinity. Agricultural Journal, 6(6), 327–339. [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Loaiza, V., Oliveira, M., Santos, T., Schüler, L., Lima, A. R., Gama, F., Salazar, M., Neng, N. R., Nogueira, J. M. F., Varela, J., & Barreira, L. (2020). Wild vs cultivated halophytes: Nutritional and functional differences. Food Chemistry, 333. [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, B., Khandwal, D., Gupta, N. K., Patel, J., & Mishra, A. (2023). Nutrient Composition, Physicobiochemical Analyses, Oxidative Stability and Antinutritional Assessment of Abundant Tropical Seaweeds from the Arabian Sea. Plants, 12(12). [CrossRef]

- Collini, E. (2019). Carotenoids in Photosynthesis: The Revenge of the “Accessory” Pigments. In Chem (Vol. 5, Issue 3, pp. 494–495). Elsevier Inc. [CrossRef]

- Croft, H., & Chen, J. M. (2017). Leaf pigment content. In Comprehensive Remote Sensing (Vols. 1–9, pp. 117–142). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Custódio, L., Rodrigues, M. J., Pereira, C. G., Castañeda-Loaiza, V., Fernandes, E., Standing, D., Neori, A., Shpigel, M., & Sagi, M. (2021). A review on sarcocornia species: Ethnopharmacology, nutritional properties, phytochemistry, biological activities and propagation. In Foods (Vol. 10, Issue 11). MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Dabravolski, S. A., & Isayenkov, S. V. (2023). The Role of Anthocyanins in Plant Tolerance to Drought and Salt Stresses. In Plants (Vol. 12, Issue 13). Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- Demmig-Adams, B., & Adams, W. W. (2002). Antioxidants in Photosynthesis and Human Nutrition. https://www.science.org.

- Dias, M.C., Pinto, D.C.G.A., Silva, A.M.S. (2021). Plant Flavonoids: Chemical Characteristics and Biological Activity. Molecules, 26, 5377. [CrossRef]

- ElNaker, N. A., Yousef, A. F., & Yousef, L. F. (2020). A review of Arthrocnemum (Arthrocaulon) macrostachyum chemical content and bioactivity. In Phytochemistry Reviews (Vol. 19, Issue 6, pp. 1427–1448). Springer Science and Business Media B.V. [CrossRef]

- Flowers, T. J., Munns, R., & Colmer, T. D. (2015). Sodium chloride toxicity and the cellular basis of salt tolerance in halophytes. In Annals of Botany (Vol. 115, Issue 3, pp. 419–431). Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Forghani, A. H., Mohebatinejad, H., & Fazilati, M. (2024). The Effect of Salt Stress on Antimicrobial Activity and Potential Production of Anthocyanin and Total Phenolic of Salicornia in Hydroponic Culture. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences India Section B - Biological Sciences, 94(4), 793–801. [CrossRef]

- Gengmao, Z., Yu, H., Xing, S., Shihui, L., Quanmei, S., & Changhai, W. (2015). Salinity stress increases secondary metabolites and enzyme activity in safflower. Industrial Crops and Products, 64(1), 175–181. [CrossRef]

- Harboub, N., Mighri, H., Bennour, N., Dbara, M., Pereira, C., Chouikhi, N., Custódio, L., Abdellaoui, R., & Akrout, A. (2025). Nutritional profile, chemical composition and health promoting properties of Salicornia emerici Duval-Jouve and Sarcocornia alpini (Lag.) Rivas Mart. from southern Tunisia. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology, 64. [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M., Bhuyan, M. H. M. B., Zulfiqar, F., Raza, A., Mohsin, S. M., Al Mahmud, J., Fujita, M., & Fotopoulos, V. (2020). Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant defense in plants under abiotic stress: Revisiting the crucial role of a universal defense regulator. In Antioxidants (Vol. 9, Issue 8, pp. 1–52). MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M. Al, Chaura, J., Donat-Torres, M. P., Boscaiu, M., & Vicente, O. (2017). Antioxidant responses under salinity and drought in three closely related wild monocots with different ecological optima. AoB PLANTS, 9(2). [CrossRef]

- Hichem, H., Mounir, D., & Naceur, E. A. (2009). Differential responses of two maize (Zea mays L.) varieties to salt stress: Changes on polyphenols composition of foliage and oxidative damages. Industrial Crops and Products, 30(1), 144–151. [CrossRef]

- Hodges, D.M., DeLong, J.M., Forney, C.F. and Prange, R.K., (1999). Improving the thiobarbituric acid-reactive-substances assay for estimating lipid peroxidation in plant tissues containing anthocyanin and other interfering compounds. Planta, 207, pp.604-611.

- Hurkman, W. J., Fornari, C. S., & Tanaka, C. K. (1989). A Comparison of the Effect of Salt on Polypeptides and Translatable mRNAs in Roots of a Salt-Tolerant and a Salt-Sensitive Cultivar of Barley. In Plant Physiol (Vol. 90). https://academic.oup.com/plphys/article/90/4/1444/6082300.

- Ibraheem, F., Albaqami, M., & Elghareeb, E. M. (2025). Halophytic resilience in extreme environments: adaptive strategies of Suaeda schimperi in the Red Sea’s hyper-arid salt marshes. Plant, Soil and Environment, 71(5), 320–337. [CrossRef]

- Jameel, J., Anwar, T., Majeed, S., Qureshi, H., Siddiqi, E. H., Sana, S., Zaman, W., & Ali, H. M. (2024a). Effect of salinity on growth and biochemical responses of brinjal varieties: implications for salt tolerance and antioxidant mechanisms. BMC Plant Biology, 24(1). [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, S. S., Likens, G. E., Pace, M. L., Utz, R. M., Haq, S., Gorman, J., & Grese, M. (2018). Freshwater salinization syndrome on a continental scale. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(4), E574–E583. [CrossRef]

- Khatri, K., & Rathore, M. S. (2022). Salt and osmotic stress-induced changes in physio-chemical responses, PSII photochemistry and chlorophyll a fluorescence in peanut. Plant Stress, 3. [CrossRef]

- Khlestkina, E. (2013). The adaptive role of flavonoids: Emphasis on cereals. Cereal Research Communications, 41(2), 185–198. [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y., & Zheng, Y. (2014). Potential of Producing Salicornia bigelovii Hydroponically as a Vegetable at Moderate NaCl Salinity. In HORTSCIENCE (Vol. 49, Issue 9).

- Kovinich, N., Kayanja, G., Chanoca, A., Riedl, K., Otegui, M. S., & Grotewold, E. (2014). Not all anthocyanins are born equal: distinct patterns induced by stress in Arabidopsis. Planta, 240(5), 931–940. [CrossRef]

- Ksouri, R., Megdiche, W., Debez, A., Falleh, H., Grignon, C., & Abdelly, C. (2007). Salinity effects on polyphenol content and antioxidant activities in leaves of the halophyte Cakile maritima. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 45(3–4), 244–249. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., Li, G., Yang, J., Huang, X., Ji, Q., Liu, Z., Ke, W., & Hou, H. (2021). Effect of Salt Stress on Growth, Physiological Parameters, and Ionic Concentration of Water Dropwort (Oenanthe javanica) Cultivars. Frontiers in Plant Science, 12. [CrossRef]

- Kurmanbayeva, A., Bekturova, A., Soltabayeva, A., Oshanova, D., Zhadyrassyn, N., Srivastava, S., Tiwari, P., Dubey, A.K., Sagi, M. (2022). Active O-acetylserine-(thiol) lyase A and B confer improved selenium resistance and degrade L-Cys and L-SeCys in Arabidopsis. Journal of Experimental Botany, Volume 73, Issue 8, Pages 2525–2539. [CrossRef]

- Lima, A. R., Castañeda-Loaiza, V., Salazar, M., Nunes, C., Quintas, C., Gama, F., Pestana, M., Correia, P. J., Santos, T., Varela, J., & Barreira, L. (2020). Influence of cultivation salinity in the nutritional composition, antioxidant capacity and microbial quality of Salicornia ramosissima commercially produced in soilless systems. Food Chemistry, 333. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., & Ahammed, G. J. (2023). Hormonal regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis for improved stress tolerance in plants. In Plant Physiology and Biochemistry (Vol. 201). Elsevier Masson s.r.l. [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, T., Bertacchi, A., Pistelli, L., Pardossi, A., Pecchia, S., Toffanin, A., & Sanmartin, C. (2022). Biological and Agronomic Traits of the Main Halophytes Widespread in the Mediterranean Region as Potential New Vegetable Crops. In Horticulturae (Vol. 8, Issue 3). MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Maduraimuthu, D., Agric, M. J., Djanaguiraman, M., Ramadass, R., & Durga Devi, D. (2004). Effect of salinity on chlorophyll content of rice genotypes. Effect of salt stress on germination and seedling growth in rice genotypes. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/284041307.

- Mandal, R., & Dutta, G. (2020). From photosynthesis to biosensing: Chlorophyll proves to be a versatile molecule. In Sensors International (Vol. 1). KeAi Communications Co. [CrossRef]

- Marone, D., Mastrangelo, A. M., Borrelli, G. M., Mores, A., Laidò, G., Russo, M. A., & Ficco, D. B. M. (2022). Specialized metabolites: Physiological and biochemical role in stress resistance, strategies to improve their accumulation, and new applications in crop breeding and management. In Plant Physiology and Biochemistry (Vol. 172, pp. 48–55). Elsevier Masson s.r.l. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A., Patel, M. K., & Jha, B. (2015). Non-targeted metabolomics and scavenging activity of reactive oxygen species reveal the potential of Salicornia brachiata as a functional food. Journal of Functional Foods, 13, 21–31. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, H. and Kardan, J. (2015). Morphological and physiological responses of some halophytes to salinity stress. In Annales Universitatis Mariae Curie-Sklodowska, sectio C–Biologia (Vol. 70, No. 2). Uniwersytet Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej.

- Pareek, A., Lata Singla, S., Kumar Kush, A., & Grover, A. (1997). Distribution patterns of HSP 90 protein in rice. In Plant Science (Vol. 125).

- Parida, A. K., Veerabathini, S. K., Kumari, A., & Agarwal, P. K. (2016). Physiological, anatomical and metabolic implications of salt tolerance in the halophyte Salvadora persica under hydroponic culture condition. Frontiers in Plant Science, 7(MAR2016). [CrossRef]

- Patel, J., Khandwal, D., Choudhary, B., Ardeshana, D., Jha, R. K., Tanna, B., Yadav, S., Mishra, A., Varshney, R. K., & Siddique, K. H. M. (2022). Differential Physio-Biochemical and Metabolic Responses of Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) under Multiple Abiotic Stress Conditions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(2). [CrossRef]

- Patel, J., Khatri, K.,, Sisay, T. A., Nja, Z.D., Choudhary, B., Nurbekova, Z., Mishra, A., Sikron, N., Standing, D., Mudgal, A., Mudgal, V., Sagi, M. (2025). UV-C-induced reactive carbonyl species are better detoxified in the halophytic plants Salicornia brachiata and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum than in the halophytic Sarcocornia fruticosa plants. The Plant Journal 122, e70239. [CrossRef]

- Pavlovic, D., Nikolic, B., Djurovic, S., Waisi, H., Andjelkovic, A., & Marisavljevic, D. (2014). Chlorophyll as a measure of plant health: Agroecological aspects. Pesticidi i Fitomedicina, 29(1), 21–34. [CrossRef]

- Pincus, M.R., (2001). Physiological structure and function of proteins. In Cell physiology source book (pp. 19–42). Academic Press.

- Rabhi, M., Castagna, A., Remorini, D., Scattino, C., Smaoui, A., Ranieri, A., & Abdelly, C. (2012). Photosynthetic responses to salinity in two obligate halophytes: Sesuvium portulacastrum and Tecticornia indica. South African Journal of Botany, 79, 39–47. [CrossRef]

- Rao, M. J., & Zheng, B. (2025). The Role of Polyphenols in Abiotic Stress Tolerance and Their Antioxidant Properties to Scavenge Reactive Oxygen Species and Free Radicals. In Antioxidants (Vol. 14, Issue 1). Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- Redondo-Gómez, S., Mateos-Naranjo, E., Figueroa, M. E., & Davy, A. J. (2010). Salt stimulation of growth and photosynthesis in an extreme halophyte, Arthrocnemum macrostachyum. Plant Biology, 12(1), 79–87. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M. J., Gangadhar, K. N., Vizetto-Duarte, C., Wubshet, S. G., Nyberg, N. T., Barreira, L., Varela, J., & Custódio, L. (2014). Maritime halophyte species from southern Portugal as sources of bioactive molecules. Marine Drugs, 12(4), 2228–2244. [CrossRef]

- Rudrapal, M., Khairnar, S. J., Khan, J., Dukhyil, A. Bin, Ansari, M. A., Alomary, M. N., Alshabrmi, F. M., Palai, S., Deb, P. K., & Devi, R. (2022). Dietary Polyphenols and Their Role in Oxidative Stress-Induced Human Diseases: Insights Into Protective Effects, Antioxidant Potentials and Mechanism(s) of Action. In Frontiers in Pharmacology (Vol. 13). Frontiers Media S.A. [CrossRef]

- Sagi, M., Davydov, O., Orazova, S., Yesbergenova, Z., Ophir, R., Stratmann, J. W., Fluhr, R. (2004). Plant Respiratory Burst Oxidase Homologs Impinge on Wound Responsiveness and Development in Lycopersicon esculentum. The Plant Cell, 16(3), 616–628. [CrossRef]

- Salazar, O. R., Chen, K., Melino, V. J., Reddy, M. P., Hřibová, E., Čížková, J., Beránková, D., Arciniegas Vega, J. P., Cáceres Leal, L. M., Aranda, M., Jaremko, L., Jaremko, M., Fedoroff, N. V., Tester, M., & Schmöckel, S. M. (2024). SOS1 tonoplast neo-localization and the RGG protein SALTY are important in the extreme salinity tolerance of Salicornia bigelovii. Nature Communications, 15(1). [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S., Mondal, M., Ghosh, P., Saha, M., & Chatterjee, S. (2020). Quantification of total protein content from some traditionally used edible plant leaves: A comparative study. Journal of Medicinal Plants Studies, 8(4), 166–170. [CrossRef]

- Sarker, U., & Oba, S. (2019). Salinity stress enhances color parameters, bioactive leaf pigments, vitamins, polyphenols, flavonoids and antioxidant activity in selected Amaranthus leafy vegetables. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 99(5), 2275–2284. [CrossRef]

- Shah, S. H., Houborg, R., & McCabe, M. F. (2017). Response of Chlorophyll, Carotenoid and SPAD-502 measurement to salinity and nutrient stress in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). In Agronomy (Vol. 7, Issue 3). MDPI AG. [CrossRef]

- Sisay, T. A., Nurbekova, Z., Oshanova, D., Dubey, A. K., Khatri, K., Mudgal, V., Mudgal, A., Neori, A., Shpigel, M., Srivastava, R. K., Custódio, L. M. B., Standing, D., & Sagi, M. (2022). Effect of Salinity and Nitrogen Fertilization Levels on Growth Parameters of Sarcocornia fruticosa, Salicornia brachiata, and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum. Agronomy, 12(8). [CrossRef]

- Soltabayeva, A., Ongaltay, A., Omondi, J. O., & Srivastava, S. (2021). Morphological, physiological and molecular markers for salt-stressed plants. In Plants (Vol. 10, Issue 2, pp. 1–18). MDPI AG. [CrossRef]

- Soltabayeva, A., Bekturova, A., Kurmanbayeva, A., Oshanova, D., Nurbekova, Z., Srivastava, S., Standing, D., Sagi, M. (2022). Ureides are accumulated similarly in response to UV-C irradiation and wounding in Arabidopsis leaves but are remobilized differently during recovery. Journal of Experimental Botany, 73(3), 1016–1032. [CrossRef]

- Souid, A., Bellani, L., Tassi, E. L., Ben Hamed, K., Longo, V., & Giorgetti, L. (2023). Early Physiological, Cytological and Antioxidative Responses of the Edible Halophyte Chenopodium quinoa Exposed to Salt Stress. Antioxidants, 12(5). [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, R., (2021). Physicochemical, antioxidant properties of carotenoids and its optoelectronic and interaction studies with chlorophyll pigments. Scientific Reports vol. 11, Article number: 18365. [CrossRef]

- Szekely-Varga, Z., González-Orenga, S., Cantor, M., Jucan, D., Boscaiu, M., & Vicente, O. (2020). Effects of drought and salinity on two commercial varieties of lavandula angustifolia mill. Plants, 9(5). [CrossRef]

- Taïbi, K., Taïbi, F., Ait Abderrahim, L., Ennajah, A., Belkhodja, M., & Mulet, J. M. (2016). Effect of salt stress on growth, chlorophyll content, lipid peroxidation and antioxidant defence systems in Phaseolus vulgaris L. South African Journal of Botany, 105, 306–312. [CrossRef]

- Talebzadeh, F., & Valeo, C. (2022). Evaluating the Effects of Environmental Stress on Leaf Chlorophyll Content as an Index for Tree Health. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 1006(1). [CrossRef]

- Tan, X., Zhu, J., & Wakisaka, M. (2020). Effect of protocatechuic acid on Euglena gracilis growth and accumulation of metabolites. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(21), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Türkan, I., & Demiral, T. (2009). Recent developments in understanding salinity tolerance. In Environmental and Experimental Botany (Vol. 67, Issue 1, pp. 2–9). [CrossRef]

- Valifard, M., Mohsenzadeh, S., Kholdebarin, B., & Rowshan, V. (2014). Effects of salt stress on volatile compounds, total phenolic content and antioxidant activities of Salvia mirzayanii. South African Journal of Botany, 93, 92–97. [CrossRef]

- Ventura, Y., Eshel, A., Pasternak, D., & Sagi, M. (2015). The development of halophyte-based agriculture: Past and present. In Annals of Botany (Vol. 115, Issue 3, pp. 529–540). Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Ventura, Y., Myrzabayeva, M., Alikulov, Z., Omarov, R., Khozin-Goldberg, I., & Sagi, M. (2014). Effects of salinity on flowering, morphology, biomass accumulation and leaf metabolites in an edible halophyte. AoB PLANTS, 6. [CrossRef]

- Ventura, Y., & Sagi, M. (2013). Halophyte crop cultivation: The case for salicornia and sarcocornia. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 92, 144–153. [CrossRef]

- Ventura, Y., Wuddineh, W. A., Myrzabayeva, M., Alikulov, Z., Khozin-Goldberg, I., Shpigel, M., Samocha, T. M., & Sagi, M. (2011a). Effect of seawater concentration on the productivity and nutritional value of annual Salicornia and perennial Sarcocornia halophytes as leafy vegetable crops. Scientia Horticulturae, 128(3), 189–196. [CrossRef]

- Ventura, Y., Wuddineh, W. A., Shpigel, M., Samocha, T. M., Klim, B. C., Cohen, S., Shemer, Z., Santos, R., & Sagi, M. (2011b). Effects of day length on flowering and yield production of Salicornia and Sarcocornia species. Scientia Horticulturae, 130(3), 510–516. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C., Shi, D., & Wang, D. (2008). Comparative effects of salt and alkali stresses on growth, osmotic adjustment and ionic balance of an alkali-resistant halophyte Suaeda glauca (Bge.). Plant Growth Regulation, 56(2), 179–190. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The impact of 21-day and 30-day successive harvesting intervals on the fresh biomass accumulation in Sarcocornia ecotypes VM, Shikmona (Shik), Megadim (Meg), Naaman (Naa), Ruhama (Ruh), and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum (AM). Sodium Chloride in the supplied water was at two levels (50 and 150 mM). The means plus standard error (+SE) are shown. Different uppercase letters indicate a significant difference between the same ecotypes across various harvesting intervals and salinity levels. Lowercase letters represent significant differences among the various ecotypes within the same harvesting interval and under different salinity treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p ≤ 0.05, n = 3). Representative data (of two independent experiments) are shown.

Figure 1.

The impact of 21-day and 30-day successive harvesting intervals on the fresh biomass accumulation in Sarcocornia ecotypes VM, Shikmona (Shik), Megadim (Meg), Naaman (Naa), Ruhama (Ruh), and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum (AM). Sodium Chloride in the supplied water was at two levels (50 and 150 mM). The means plus standard error (+SE) are shown. Different uppercase letters indicate a significant difference between the same ecotypes across various harvesting intervals and salinity levels. Lowercase letters represent significant differences among the various ecotypes within the same harvesting interval and under different salinity treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p ≤ 0.05, n = 3). Representative data (of two independent experiments) are shown.

Figure 2.

The effect of 21-day and 30-day harvesting intervals on shoot diameter of VM, Shikmona (Shik), Megadim (Meg), Naaman (Naa), Ruhama (Ruh), and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum (AM). Sodium Chloride in supplied water was at two levels (50 and 150 mM). The mean plus standard error (±SE) is shown. Different uppercase letters indicate a significant difference between the same ecotypes across various harvesting intervals and salinity levels. Lowercase letters represent significant differences among the various ecotypes within the same harvesting interval and under different salinity treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p ≤ 0.05, n = 6). Representative data (of two independent experiments) is shown.

Figure 2.

The effect of 21-day and 30-day harvesting intervals on shoot diameter of VM, Shikmona (Shik), Megadim (Meg), Naaman (Naa), Ruhama (Ruh), and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum (AM). Sodium Chloride in supplied water was at two levels (50 and 150 mM). The mean plus standard error (±SE) is shown. Different uppercase letters indicate a significant difference between the same ecotypes across various harvesting intervals and salinity levels. Lowercase letters represent significant differences among the various ecotypes within the same harvesting interval and under different salinity treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p ≤ 0.05, n = 6). Representative data (of two independent experiments) is shown.

Figure 3.

The effect of 21-day and 30-day harvesting intervals on total chlorophyll (A) and total carotenoid (B) levels in the shoots of Sarcocornia ecotypes VM, Shikmona (Shik), Megadim (Meg), Naaman (Naa), Ruhama (Ruh), and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum (AM). Sodium Chloride in supplied water was at two levels (50 and 150 mM). The means plus standard error (+SE) are shown. Different uppercase letters indicate a significant difference between the same ecotypes across various harvesting intervals and salinity levels. Lowercase letters represent significant differences among the various ecotypes within the same harvesting interval and under different salinity treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p ≤ 0.05, n = 9). Representative data (of two independent experiments) is shown.

Figure 3.

The effect of 21-day and 30-day harvesting intervals on total chlorophyll (A) and total carotenoid (B) levels in the shoots of Sarcocornia ecotypes VM, Shikmona (Shik), Megadim (Meg), Naaman (Naa), Ruhama (Ruh), and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum (AM). Sodium Chloride in supplied water was at two levels (50 and 150 mM). The means plus standard error (+SE) are shown. Different uppercase letters indicate a significant difference between the same ecotypes across various harvesting intervals and salinity levels. Lowercase letters represent significant differences among the various ecotypes within the same harvesting interval and under different salinity treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p ≤ 0.05, n = 9). Representative data (of two independent experiments) is shown.

Figure 4.

Relative water contents in the shoots of Sarcocornia ecotypes VM, Shikmona (Shik), Megadim (Meg), Naaman (Naa), Ruhama (Ruh), and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum (AM) at two different harvesting intervals (21-day and 30-day) with two different salinity levels (50 and 150 mM) treatments. The means plus standard error (+SE) are shown. Different uppercase letters indicate a significant difference between the same ecotypes across various harvesting intervals and salinity levels. Lowercase letters represent significant differences among the various ecotypes within the same harvesting interval and under different salinity treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p ≤ 0.05, n = 4). Representative data (of two independent experiments) is shown.

Figure 4.

Relative water contents in the shoots of Sarcocornia ecotypes VM, Shikmona (Shik), Megadim (Meg), Naaman (Naa), Ruhama (Ruh), and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum (AM) at two different harvesting intervals (21-day and 30-day) with two different salinity levels (50 and 150 mM) treatments. The means plus standard error (+SE) are shown. Different uppercase letters indicate a significant difference between the same ecotypes across various harvesting intervals and salinity levels. Lowercase letters represent significant differences among the various ecotypes within the same harvesting interval and under different salinity treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p ≤ 0.05, n = 4). Representative data (of two independent experiments) is shown.

Figure 5.

The impact of 21-day and 30-day harvesting intervals on total protein contents in the shoots of Sarcocornia ecotypes VM, Shikmona (Shik), Megadim (Meg), Naaman (Naa), Ruhama (Ruh), and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum (AM). Sodium Chloride in supplied water was at two levels (50 and 150 mM). The means plus standard error (+SE) are shown. Different uppercase letters indicate a significant difference between the same ecotypes across various harvesting intervals and salinity levels. Lowercase letters represent significant differences among the various ecotypes within the same harvesting interval and under different salinity treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p ≤ 0.05, n = 6). Representative data (of two independent experiments) is shown.

Figure 5.

The impact of 21-day and 30-day harvesting intervals on total protein contents in the shoots of Sarcocornia ecotypes VM, Shikmona (Shik), Megadim (Meg), Naaman (Naa), Ruhama (Ruh), and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum (AM). Sodium Chloride in supplied water was at two levels (50 and 150 mM). The means plus standard error (+SE) are shown. Different uppercase letters indicate a significant difference between the same ecotypes across various harvesting intervals and salinity levels. Lowercase letters represent significant differences among the various ecotypes within the same harvesting interval and under different salinity treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p ≤ 0.05, n = 6). Representative data (of two independent experiments) is shown.

Figure 6.

The impact of 21-day and 30-day harvesting intervals on total soluble sugar(A) and electrical conductivity(B) contents in the shoots of Sarcocornia ecotypes VM, Shikmona (Shik), Megadim (Meg), Naaman (Naa), Ruhama (Ruh), and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum (AM). Sodium Chloride in the supplied water was at two levels (50 and 150 mM). The means plus standard error (+SE) are shown. Different uppercase letters indicate a significant difference between the same ecotypes across various harvesting intervals and salinity levels. Lowercase letters represent significant differences among the various ecotypes within the same harvesting interval and under different salinity treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p ≤ 0.05, n =3-4). Representative data (of two independent experiments) is shown.

Figure 6.

The impact of 21-day and 30-day harvesting intervals on total soluble sugar(A) and electrical conductivity(B) contents in the shoots of Sarcocornia ecotypes VM, Shikmona (Shik), Megadim (Meg), Naaman (Naa), Ruhama (Ruh), and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum (AM). Sodium Chloride in the supplied water was at two levels (50 and 150 mM). The means plus standard error (+SE) are shown. Different uppercase letters indicate a significant difference between the same ecotypes across various harvesting intervals and salinity levels. Lowercase letters represent significant differences among the various ecotypes within the same harvesting interval and under different salinity treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p ≤ 0.05, n =3-4). Representative data (of two independent experiments) is shown.

Figure 7.

The impact of 21-day and 30-day harvesting intervals on anthocyanin levels in the shoots of Sarcocornia ecotypes VM, Shikmona (Shik), Megadim (Meg), Naaman (Naa), Ruhama (Ruh), and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum (AM). Sodium chloride was supplied at two levels (50 mM and 150 mM). Means plus standard error (+SE) are shown. Different uppercase letters indicate a significant difference between the same ecotypes across various harvesting intervals and salinity levels. Lowercase letters represent significant differences among the various ecotypes within the same harvesting interval and under different salinity treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p ≤ 0.05, n = 4). Representative data (of two independent experiments) is shown.

Figure 7.

The impact of 21-day and 30-day harvesting intervals on anthocyanin levels in the shoots of Sarcocornia ecotypes VM, Shikmona (Shik), Megadim (Meg), Naaman (Naa), Ruhama (Ruh), and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum (AM). Sodium chloride was supplied at two levels (50 mM and 150 mM). Means plus standard error (+SE) are shown. Different uppercase letters indicate a significant difference between the same ecotypes across various harvesting intervals and salinity levels. Lowercase letters represent significant differences among the various ecotypes within the same harvesting interval and under different salinity treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p ≤ 0.05, n = 4). Representative data (of two independent experiments) is shown.

Figure 9.

The impact of 21-day and 30-day harvesting intervals on total polyphenol content in the shoots of Sarcocornia ecotypes VM, Shikmona (Shik), Megadim (Meg), Naaman (Naa), Ruhama (Ruh), and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum (AM). Sodium Chloride in supplied water was at two levels (50 and 150 mM). The means plus standard error (+SE) are shown. Different uppercase letters indicate a significant difference between the same ecotypes across various harvesting intervals and salinity levels. Lowercase letters represent significant differences among the various ecotypes within the same harvesting interval and under different salinity treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p ≤ 0.05, n = 6). Representative data (of two independent experiments) is shown.

Figure 9.

The impact of 21-day and 30-day harvesting intervals on total polyphenol content in the shoots of Sarcocornia ecotypes VM, Shikmona (Shik), Megadim (Meg), Naaman (Naa), Ruhama (Ruh), and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum (AM). Sodium Chloride in supplied water was at two levels (50 and 150 mM). The means plus standard error (+SE) are shown. Different uppercase letters indicate a significant difference between the same ecotypes across various harvesting intervals and salinity levels. Lowercase letters represent significant differences among the various ecotypes within the same harvesting interval and under different salinity treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p ≤ 0.05, n = 6). Representative data (of two independent experiments) is shown.

Figure 10.

The impact of 21-day and 30-day harvesting intervals on radical scavenging activities by DPPH in fresh shoots of Sarcocornia ecotypes VM, Shikmona (Shik), Megadim (Meg), Naaman (Naa), Ruhama (Ruh), and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum (AM). Sodium Chloride in supplied water was at two levels (50 and 150 mM). The means plus standard error (+SE) are shown. Different uppercase letters indicate a significant difference between the same ecotypes across various harvesting intervals and salinity levels. Lowercase letters represent significant differences among the various ecotypes within the same harvesting interval and under different salinity treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p ≤ 0.05, n = 6). Representative data (of two independent experiments) is shown.

Figure 10.

The impact of 21-day and 30-day harvesting intervals on radical scavenging activities by DPPH in fresh shoots of Sarcocornia ecotypes VM, Shikmona (Shik), Megadim (Meg), Naaman (Naa), Ruhama (Ruh), and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum (AM). Sodium Chloride in supplied water was at two levels (50 and 150 mM). The means plus standard error (+SE) are shown. Different uppercase letters indicate a significant difference between the same ecotypes across various harvesting intervals and salinity levels. Lowercase letters represent significant differences among the various ecotypes within the same harvesting interval and under different salinity treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p ≤ 0.05, n = 6). Representative data (of two independent experiments) is shown.

Figure 11.

Malondialdehyde levels in shoots of Sarcocornia ecotypes VM, Shikmona (Shik), Megadim (Meg), Naaman (Naa), Ruhama (Ruh), and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum (AM) at two different harvesting intervals (21-day and 30-day) with two different salinity levels (50 and 150 mM) treatments. The means plus standard error (+SE) are shown. Different uppercase letters indicate a significant difference between the same ecotypes across various harvesting intervals and salinity levels. Lowercase letters represent significant differences among the various ecotypes within the same harvesting interval and under different salinity treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p ≤ 0.05, n = 4). Representative data (of two independent experiments) is shown.

Figure 11.

Malondialdehyde levels in shoots of Sarcocornia ecotypes VM, Shikmona (Shik), Megadim (Meg), Naaman (Naa), Ruhama (Ruh), and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum (AM) at two different harvesting intervals (21-day and 30-day) with two different salinity levels (50 and 150 mM) treatments. The means plus standard error (+SE) are shown. Different uppercase letters indicate a significant difference between the same ecotypes across various harvesting intervals and salinity levels. Lowercase letters represent significant differences among the various ecotypes within the same harvesting interval and under different salinity treatments (Tukey’s HSD, p ≤ 0.05, n = 4). Representative data (of two independent experiments) is shown.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).