Submitted:

24 August 2025

Posted:

27 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

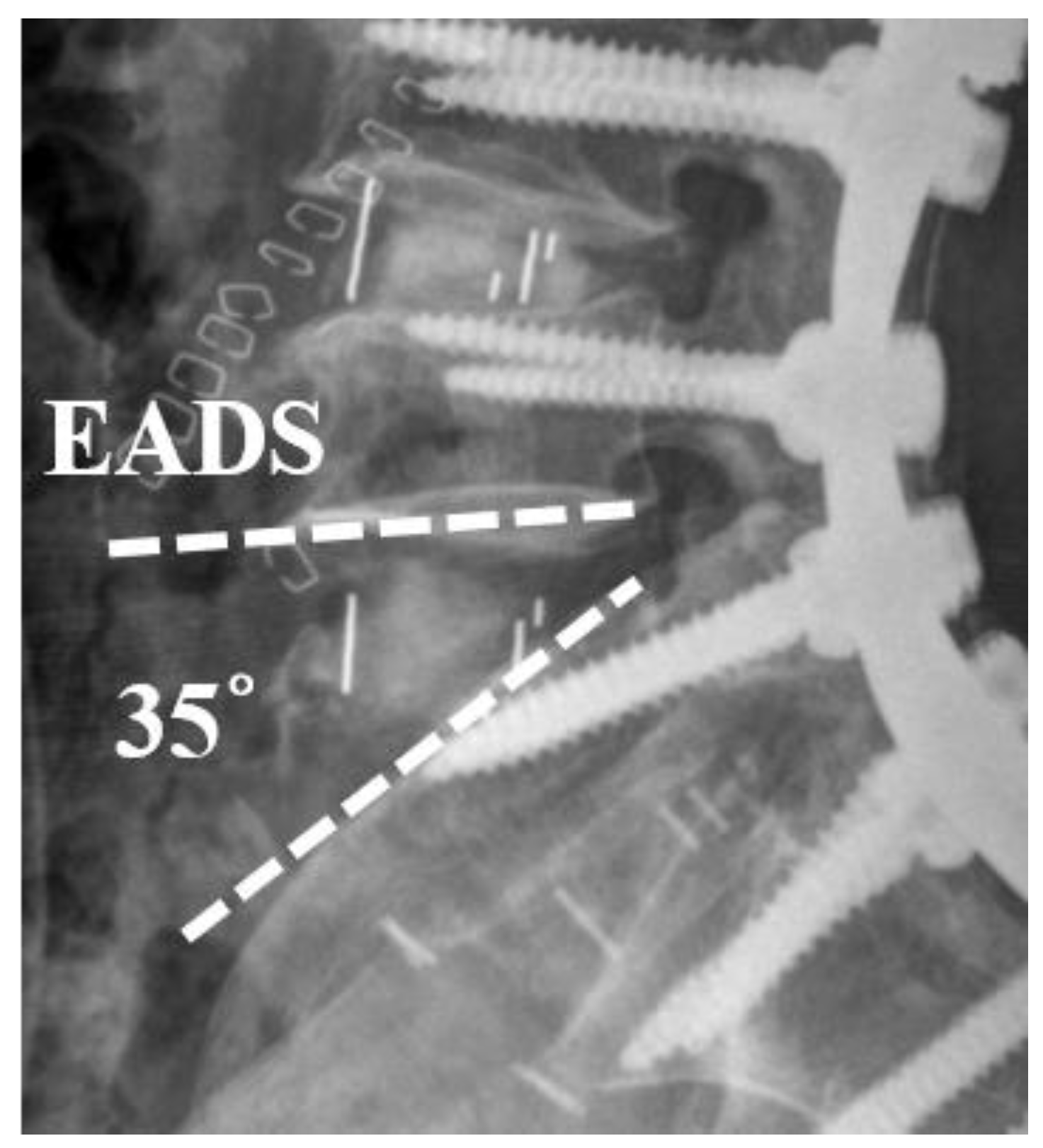

2.1. Radiographic Evaluation

2.2. Clinical Evaluation and Complications

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Surgical Data

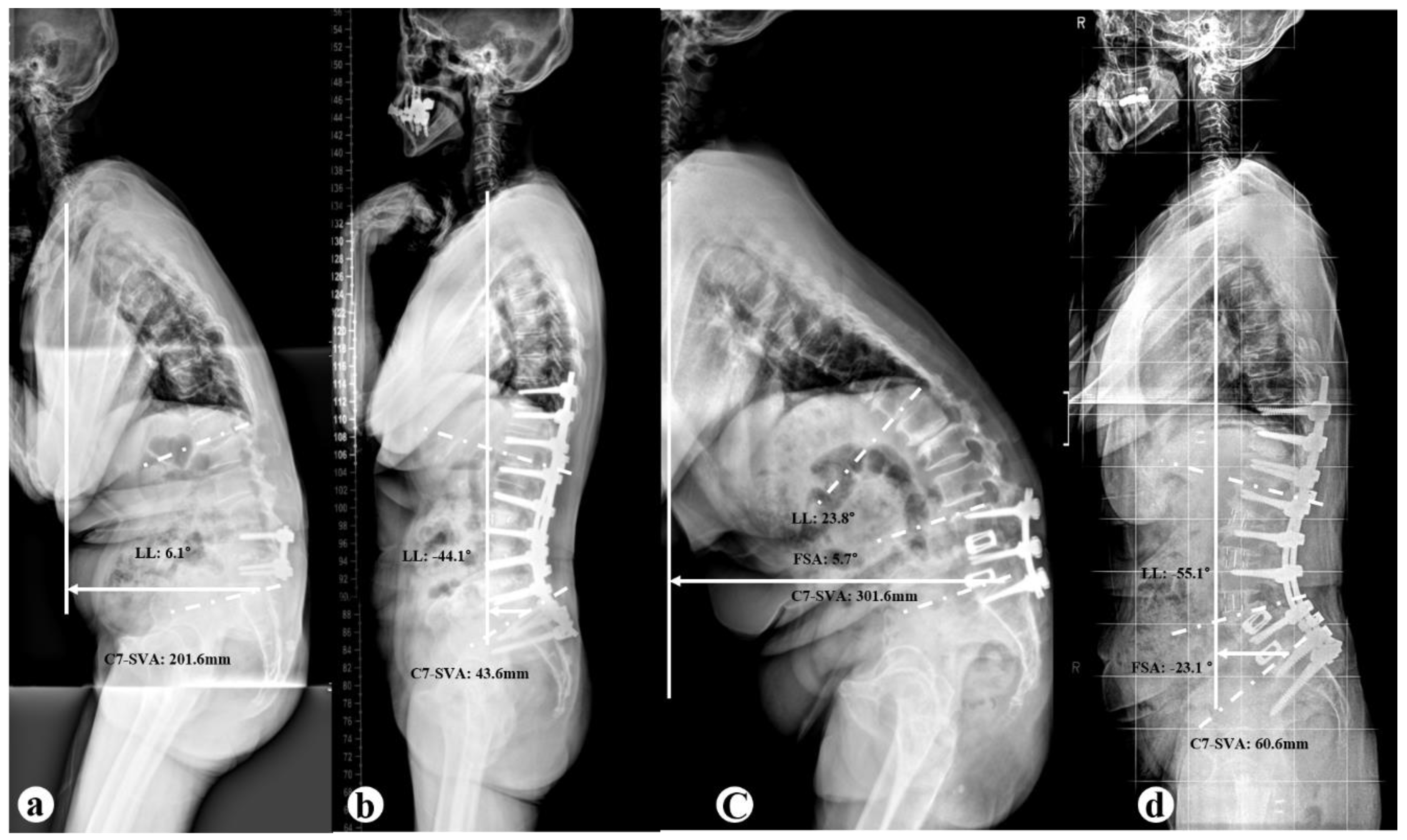

3.2. Radiographic Parameters

3.3. Clinical Outcomes and Complications

3.4. Preoperative Radiographic Parameters Depend on Complication

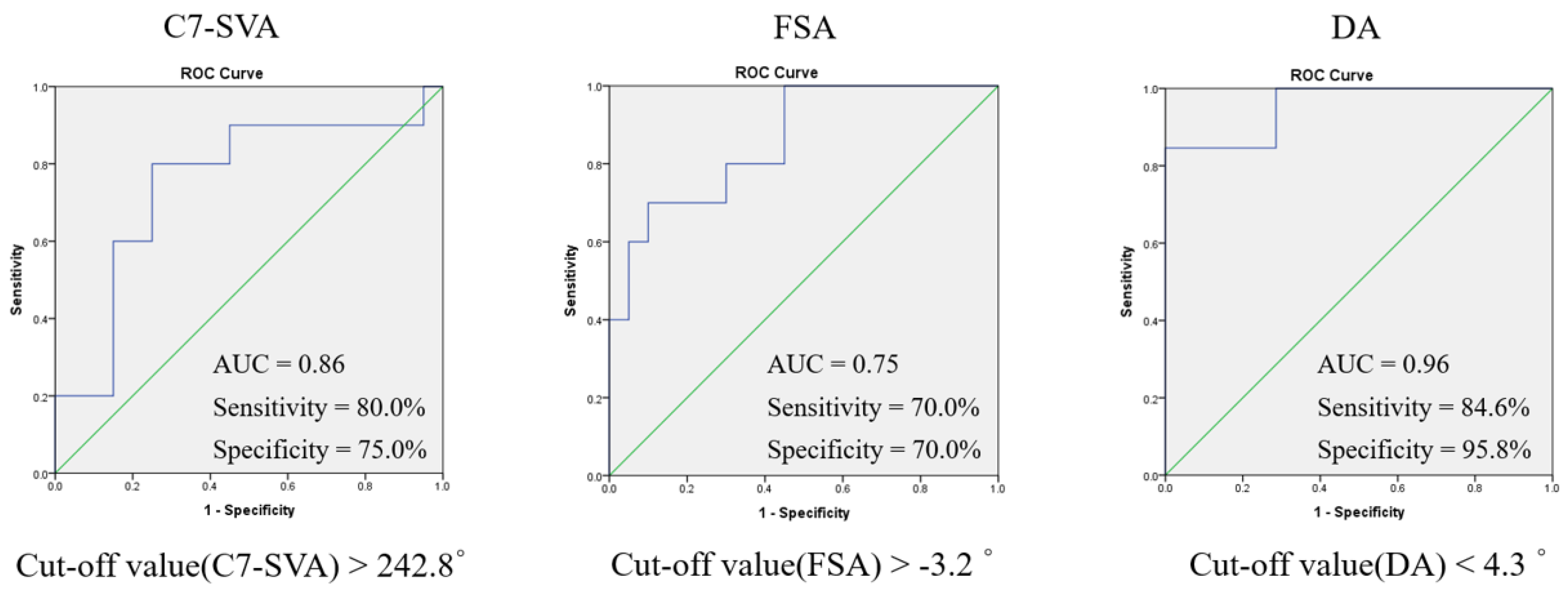

3.5. Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves Determining Optimal Cut-Off Values of Spinopelvic Parameters

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACR | Anterior column realignment |

| ALL | Anterior longitudinal ligament |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| C7SVA | C7 sagittal vertical axis |

| DA | Dynamic segment angulation |

| DL | Dynamic lumbar lordosis |

| DSI | Degenerative sagittal imbalance |

| EADH | Excessive distraction of anterior disc height |

| EBL | Estimated blood loss |

| FSA | Fused segment angle |

| LL | Lumbar lordosis |

| LLL | Lower lumbar lordosis |

| ODI | Oswestry Disability Index |

| PI | Pelvic incidence |

| PI–LL | Pelvic incidence minus lumbar lordosis |

| PLIF | Posterior lumbar interbody fusion |

| PROMs | Patient-reported outcome measures |

| PSO | Pedicle subtraction osteotomy |

| PT | Pelvic tilt |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| SVA | Sagittal vertical axis |

| SS | Sacral slope |

| TK | Thoracic kyphosis |

References

- Booth, K.C.; Bridwell, K.H.; Lenke, L.G.; Baldus, C.R.; Blanke, K.M. Complications and Predictive Factors for the Successful Treatment of Flatback Deformity (Fixed Sagittal Imbalance). Spine 1999, 24, 1712–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, G.C.; Ondra, S.L.; Shaffrey, C.I. Management of Iatrogenic Flat-Back Syndrome. Neurosurg. Focus 2003, 15, E8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagannathan, J.; Sansur, C.A.; Shaffrey, C.I. Iatrogenic Spinal Deformity. Neurosurgery 2008, 63 (Suppl. 3), 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagrone, M.O.; Bradford, D.S.; Moe, J.H.; Lonstein, J.E.; Winter, R.B.; Ogilvie, J.W. Treatment of Symptomatic Flatback after Spinal Fusion. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1988, 70, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, J.W.; Patel, A.A. Fixed Sagittal Plane Imbalance. Global Spine J. 2014, 4, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louie, P.K.; Iyer, S.; Khanna, K.; Harada, G.K.; Khalid, A.; Gupta, M.; Burton, D.; Shaffrey, C.; Lafage, R.; Lafage, V.; et al. Revision Strategies for Harrington Rod Instrumentation: Radiographic Outcomes and Complications. Global Spine J. 2022, 12, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.C.; Ferrero, E.; Mundis, G.; Smith, J.S.; Shaffrey, C.I.; Schwab, F.; Kim, H.J.; Boachie-Adjei, O.; Lafage, V.; Bess, S.; et al. Pedicle Subtraction Osteotomy in the Revision Versus Primary Adult Spinal Deformity Patient: Is There a Difference in Correction and Complications? Spine 2015, 40, E1169–E1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potter, B.K.; Lenke, L.G.; Kuklo, T.R. Prevention and Management of Iatrogenic Flatback Deformity. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2004, 86, 1793–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diebo, B.G.; Shah, N.V.; Boachie-Adjei, O.; Zhu, F.; Rothenfluh, D.A.; Paulino, C.B.; Schwab, F.J.; Lafage, V. Adult Spinal Deformity. Lancet 2019, 394, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebo, B.G.; Balmaceno-Criss, M.; Lafage, R.; McDonald, C.L.; Alsoof, D.; Halayqeh, S.; DiSilvestro, K.J.; Kuris, E.O.; Lafage, V.; Daniels, A.H. Sagittal Alignment in the Degenerative Lumbar Spine: Surgical Planning. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2024, 106, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Carreon, L.Y.; Dimar, J.R., II. The Role of Anterior Spine Surgery in Deformity Correction. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 34, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, A.K.; Mummaneni, P.V.; Shaffrey, C.I. Approach Selection: Multiple Anterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion to Recreate Lumbar Lordosis Versus Pedicle Subtraction Osteotomy: When, Why, How? Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 29, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uribe, J.S.; Schwab, F.; Mundis, G.M.; Xu, D.S.; Januszewski, J.; Kanter, A.S.; Okonkwo, D.O.; Hu, S.S.; Vedat, D.; Eastlack, R.; et al. The Comprehensive Anatomical Spinal Osteotomy and Anterior Column Realignment Classification. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2018, 29, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirai, T.; Yoshii, T.; Egawa, S.; Sakai, K.; Inose, H.; Yuasa, M.; Yamada, T.; Ushio, S.; Kato, T.; Arai, Y.; et al. Increased Height of Fused Segments Contributes to Early-Phase Strut Subsidence after Anterior Cervical Corpectomy with Fusion for Multilevel Ossification of the Posterior Longitudinal Ligament. Spine Surg. Relat. Res. 2020, 4, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, S.H.; Lin, S.Y.; Shen, P.C.; Tu, H.P.; Huang, H.T.; Shih, C.L.; Lu, C.C. Pain Control Affects the Radiographic Diagnosis of Segmental Instability in Patients with Degenerative Lumbar Spondylolisthesis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frerich, J.M.; Dibble, C.F.; Park, C.; Bergin, S.M.; Goodwin, C.R.; Abd-El-Barr, M.M.; Shaffrey, C.I.; Than, K.D. Proximal Lumbar Anterior Column Realignment for Iatrogenic Sagittal Plane Adult Spinal Deformity Correction: A Retrospective Case Series. World Neurosurg. 2025, 193, 884–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lainé, G.; Le Huec, J.C.; Blondel, B.; Fuentes, S.; Fiere, V.; Parent, H.; Lucas, F.; Roussouly, P.; Tassa, O.; Bravant, E.; et al. Factors Influencing Complications after 3-Columns Spinal Osteotomies for Fixed Sagittal Imbalance from Multiple Etiologies: A Multicentric Cohort Study about 286 Cases in 273 Patients. Eur. Spine J. 2022, 31, 3673–3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.J.; Kim, K.T.; Kim, W.J.; Lee, S.H.; Jung, J.H.; Kim, Y.T.; Park, H.B. Pedicle Subtraction Osteotomy in Elderly Patients with Degenerative Sagittal Imbalance. Spine 2013, 38, E1561–E1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godzik, J.; Hlubek, R.J.; de Andrada Pereira, B.; Xu, D.S.; Walker, C.T.; Farber, S.H.; Turner, J.D.; Mundis, G.; Uribe, J.S. Combined Lateral Transpsoas Anterior Column Realignment with Pedicle Subtraction Osteotomy to Treat Severe Sagittal Plane Deformity: Cadaveric Feasibility Study and Early Clinical Experience. World Neurosurg. 2019, 121, e589–e595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadrameli, S.S.; Davidov, V.; Lee, J.J.; Huang, M.; Kizek, D.J.; Mambelli, D.; Rajendran, S.; Barber, S.M.; Holman, P.J. Hybrid Anterior Column Realignment–Pedicle Subtraction Osteotomy for Severe Rigid Sagittal Deformity. World Neurosurg. 2021, 151, e308–e316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Wang, B.; Run, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y. Pedicle Subtraction Osteotomy and Disc Resection with Cage Placement in Post-Traumatic Thoracolumbar Kyphosis, a Retrospective Study. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2016, 11, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Bridwell, K.H.; Lenke, L.G.; Cheh, G.; Baldus, C. Results of Lumbar Pedicle Subtraction Osteotomies for Fixed Sagittal Imbalance: A Minimum 5-Year Follow-Up Study. Spine 2007, 32, 2189–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Rhim, S.C. Spinal Pedicle Subtraction Osteotomy for Fixed Sagittal Imbalance Patients. World J. Clin. Cases 2013, 1, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridwell, K.H.; Lewis, S.J.; Lenke, L.G.; Baldus, C.; Blanke, K. Pedicle Subtraction Osteotomy for the Treatment of Fixed Sagittal Imbalance. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2003, 85, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwab, F.J.; Patel, A.; Shaffrey, C.I.; Smith, J.S.; Farcy, J.P.; Boachie-Adjei, O.; Hostin, R.A.; Hart, R.A.; Akbarnia, B.A.; Burton, D.C.; et al. Sagittal Realignment Failures following Pedicle Subtraction Osteotomy Surgery: Are We Doing Enough? J. Neurosurg. Spine 2012, 16, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boody, B.S.; Rosenthal, B.D.; Jenkins, T.J.; Patel, A.A.; Savage, J.W.; Hsu, W.K. Iatrogenic Flatback and Flatback Syndrome: Evaluation, Management, and Prevention. Clin. Spine Surg. 2017, 30, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Group A (n=33) | Group B (n=16) | P Value |

| Age, years | 72.6±6.6 | 67.1±6.8 | 0.420 |

| Sex (Male: Female) | 3:30 | 1:15 | 0.733 |

| EBL (ml) | 1845±929.9 | 2260±1447.8 | 0.348 |

| BMI (%) | 25.2±3.2 | 25.5±2.2 | 0.742 |

| Operative time, minutes | 404.9±91.4 | 506.0±154.8 | 0.032* |

| Follow-up, moth | 25.2±5.8 | 25.2±4.1 | 0.981 |

| No. of previous fusion level | 1.1±0.2 | 2.2±0.8 | <0.001* |

| No. of instrumented level | 7.6±0.8 | 8.1±0.3 | 0.530 |

| No. of ACR level | 2.5±0.6 | 1.9±0.9 | 0.053 |

| PLIF L5-S1, no. (%) | 16 (40.8) | 4 (25) | 0.117 |

| PSO, no. (%) | |||

| L3 | 9 (56.3) | ||

| L4 | 7 (43.7) | ||

| Parameter | Group A (n=33) | Group B (n=16) | P Value |

| C7-SVA (mm) | |||

| Preoperative | 219.8±76.4† | 293.8±90.3† | 0.026* |

| Postoperative | 61.7±66.1† | 30.7±45.5† | 0.195 |

| correction | 157.9±84.9 | 263.0±79.9 | 0.003* |

| TK (°) | |||

| Preoperative | 8.2±14.1† | -0.4±12.2† | 0.110 |

| Postoperative | 33.4±12.6† | 29.0±13.5† | 0.389 |

| correction | -25.2±13.1 | -29.5±18.8 | 0.372 |

| LL (°) | |||

| Preoperative | 9.6±19.4† | 22.2±20.5† | 0.051 |

| Postoperative | -51.1±10.2† | -49.8±8.7† | 0.728 |

| correction | 60.7±23.3 | 72.0±17.8 | 0.100 |

| LLL (°) | |||

| Preoperative | -7.0±9.8† | -2.4±13.3† | 0.287 |

| Postoperative | -23.9±8.9† | -27.6±10.9† | 0.331 |

| correction | 16.9±10.4 | 25.2±5.8 | 0.127 |

| T1PA (°) | |||

| Preoperative | 53.5±15.4† | 64.6±17.3† | 0.085 |

| Postoperative | 20.8±11.1† | 21.8±8.9† | 0.820 |

| correction | 32.7±16.3 | 42.8±12.9 | 0.099 |

| SS (°) | |||

| Preoperative | 24.4±10.8† | 26.4±9.1† | 0.621 |

| Postoperative | 38.1±7.0† | 34.3±9.6† | 0.230 |

| correction | -13.6±8.4 | -7.9±9.1 | 0.097 |

| PT (°) | |||

| Preoperative | 34.1±12.1† | 33.4±9.3† | 0.885 |

| Postoperative | 20.1±9.5† | 25.1±10.6† | 0.212 |

| correction | 13.9±8.6 | 8.4±9.0 | 0.114 |

| PI (°) | |||

| Preoperative | 58.5±11.0 | 59.9±5.2 | 0.705 |

| Postoperative | 58.3±11.0 | 59.6±5.4 | 0.738 |

| correction | 0.1±1.2 | 0.2±1.2 | 0.726 |

| PI-LL (°) | |||

| Preoperative | 65.1±19.1† | 82.1±20.9† | 0.051 |

| Postoperative | 7.2±6.2† | 9.8±11.1† | 0.658 |

| correction | 57.8±23.4 | 72.2±17.4 | 0.096 |

| FSA (°) | |||

| Preoperative | -7.2±7.5 | 5.1±8.0† | 0.001* |

| Postoperative | -7.8±7.8 | -26.6±12.6† | < 0.001 |

| correction | -0.6±2.3 | -31.6±8.9 | < 0.001 |

| Variables | Group A (n=33) | Group B (n=16) | P Value |

| ODI | |||

| Preoperative | 28.1±7.8 | 23.5±7.6 | 0.146 |

| Postoperative | 14.5±7.4 | 11.0±7.5 | 0.229 |

| P Value | <0.001* | 0.001* | - |

| VAS-low back | |||

| Preoperative | 5.7±2.1 | 5.4±2.2 | 0.724 |

| Postoperative | 2.9±1.3 | 2.6±1.3 | 0.614 |

| P Value | <0.001* | 0.009* | - |

| Group A (n=33) | Group B (n=16) | P Value | |

| Perioperative n, (%) | |||

| Dura tear | 2, (6.1%) | 2, (12.5%) | 0.440 |

| Motor deficit | 1, (3.0%) | 2, (12.5%) | 0.195 |

| Blood loss (>4000ml) | 0 | 1, (6.3%) | 0.147 |

| EADH | 7, (21.2%) | 0 | 0.047* |

| Postoperative n, (%) | |||

| Infection | 1, (3.0%) | 1, (6.3%) | 0.593 |

| PJK | 2, (6.1%) | 1, (6.3%) | 0.979 |

| PJF | 2, (6.1%) | 1, (6.3%) | 0.979 |

| Rod fracture | 3, (9.1%) | 2, (12.5%) | 0.712 |

| Parameter | Excessive group (n=7) |

Non-excessive group (n=26) |

P Value |

| C7-SVA (mm) | 213.2 ± 83.9 | 223.3 ± 75.4 | 0.785 |

| TK (°) | 12.2 ± 10.5 | 7.2 ± 6.5 | 0.081 |

| LL (°) | 11.3 ± 13.6 | 4.1 ± 7.4 | 0.054 |

| LLL (°) | -5.6 ± 12.7 | -7.8 ± 8.3 | 0.643 |

| PT (°) | 36.4 ± 9.9 | 32.8 ± 13.4 | 0.544 |

| PI (°) | 56.2 ± 9.2 | 59.7 ± 12.1 | 0.509 |

| DL (°) | 18.6 ± 10.5 | 21.7 ± 7.4 | 0.458 |

| DA (°) | 2.8 ± 1.1 | 9.1 ± 3.5 | <0.001* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).