1. Introduction

Degenerative spine conditions represent a significant cause of disability and reduced quality of life, particularly in elderly patients or those with comorbidities such as osteoporosis[

1,

2]. These conditions often involve a combination of chronic pain, neurological deficits, and functional impairment, necessitating timely and effective management[

3,

4,

5,

6]. The lumbar spine is especially prone to degenerative changes due to its biomechanical load-bearing role, making it a frequent site of surgical intervention[

7,

8]. Historically, surgical approaches have focused on decompressing the neural elements to alleviate pain and neurological symptoms, often complemented by stabilization techniques to address spinal instability [

9,

10,

11].

Lumbar spine instability, characterized by excessive motion between vertebral segments, plays a central role in the progression of degenerative conditions[

12,

13]. Traditional stabilization techniques, such as pedicle screw and rod systems, have been widely regarded as the gold standard for achieving biomechanical stability after decompression[

14]. These systems provide robust fixation, facilitating spinal fusion and long-term biomechanical integrity [

15]. However, their application is not without challenges, particularly in elderly patients with osteoporosis or other factors compromising bone quality. In such cases, the risk of hardware failure, pseudoarthrosis, and surgical complications may be elevated, prompting the exploration of alternative stabilization methods [

16].

Interspinous devices have emerged as a promising alternative in select patient populations. Initially developed as simple extension-blocking devices to offload affected spinal segments, these systems have evolved into sophisticated interspinous fixation devices (IFDs)[

16]. Modern designs provide both decompression and stabilization while minimizing invasiveness [

17]. By distributing biomechanical stress across treated spinal segments and preserving adjacent segment mobility, interspinous devices aim to reduce the morbidity associated with traditional stabilization techniques[

18].

The rationale for utilizing interspinous devices lies in their potential to offer effective stabilization with a less invasive surgical footprint. This is particularly advantageous for patients at higher surgical risk due to advanced age, osteoporosis, or multiple comorbidities. Despite their increasing adoption, the comparative efficacy of interspinous devices versus traditional pedicle screw systems in achieving clinical and surgical outcomes remains a subject of ongoing investigation [

19].

This study aims to evaluate and compare the clinical and surgical outcomes of lumbar fusion using pedicle screws and rods with those achieved using the interspinous device in selected populations, both performed in conjunction with spinal decompression. By examining these two approaches, the study seeks to provide evidence regarding the safety, effectiveness, and appropriate indications for interspinous devices, ultimately contributing to more personalized treatment strategies for patients with degenerative lumbar spine conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This is a retrospective cohort study conducted at the Mater Olbia Hospital, Department of Neurosurgery. The study compares two groups of patients who underwent lumbar spinal decompression with subsequent stabilization using either pedicle screws and rods or an interspinous device. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Autonomous Region of Sardinia (protocol number 276/2020/CE of October 29th, 2020). The study period spanned from February 2020 to February 2023. Patients were followed for at least one year postoperatively to monitor outcomes.

2.2. Data Collection

Data were collected from electronic medical records and included demographic information, clinical history, operative details, and postoperative outcomes. Parameters analyzed included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), comorbidities, duration of hospital stay, surgical time, and intraoperative and postoperative complications. Clinical outcomes were assessed using validated instruments such as the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for back pain and leg pain[

20], the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI)[

21], and the Short Form-36 (SF-36) for quality of life[

22].

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria:

- -

Patients aged 18 years and older.

- -

Diagnosed with lumbar spinal stenosis with instability requiring surgical intervention.

- -

Underwent lumbar decompression with either pedicle screw fixation or interspinous device stabilization.

- -

Availability of complete preoperative and postoperative clinical data.

Exclusion criteria:

- -

Prior lumbar spine surgery at the affected level.

- -

Severe systemic comorbidities precluding any surgical intervention.

- -

Incomplete follow-up data.

- -

Traumatic lumbar spine conditions.

- -

Oncologic vertebral pathologies.

- -

Infectious vertebral conditions (e.g., discitis, spondylodiscitis).

Eligibility for the interspinous device group:

- -

Patients over 70 years with significant comorbidities.

- -

Patients over 50 years diagnosed with osteoporosis (confirmed by DXA scan and T-score < -2.5).

- -

Patients unsuitable for long surgical procedures (≤ 1 hour of surgical time due to high anesthetic risk).

2.4. Surgical Treatments

All surgeries were conducted by a consistent team of two experienced surgeons to ensure uniformity in the surgical approach and technique.

Group 1: Patients underwent percutaneous stabilization using pedicle screws and rods followed by lumbar decompression. This technique involved bilateral pedicle screw placement, rod fixation, and bone grafting to promote fusion. The surgical procedure adhered to the method described in the study by La Rocca et al. [

23].

Group 2: Patients underwent lumbar decompression followed by stabilization using the Aspen® interspinous device. The device was positioned between the spinous processes of the affected levels, providing segmental stability while preserving adjacent segment mobility. The surgical technique followed the protocol outlined by La Rocca et al. [

24].

The Aspen® device (Zimmer Biomet Spine, Inc, Westminster, USA) is a titanium interspinous fixation system designed to offer segmental stability following decompression. Its unique design features an adjustable interlocking mechanism, enabling secure fixation while minimizing biomechanical stress on the treated spinal segment. The device is inserted through a minimally invasive approach, reducing tissue disruption and preserving the integrity of adjacent spinal structures[

25].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using R software (version 4.4.2)[

26]. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range [IQR]) based on data distribution[

27]. The normality of distributions was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Comparisons between groups were conducted using Student’s t-test for normally distributed continuous variables and the Mann-Whitney U test for non-normally distributed variables[

28]. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages and analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate.

Multivariate analysis was performed to adjust for potential confounding factors, with regression linear models employed to evaluate predictors of clinical outcomes[

29]. Pre- and postoperative differences within groups were assessed using paired t-tests for normally distributed data or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for non-parametric data. Results were considered statistically significant at a p-value < 0.05. Effect sizes (e.g., Cohen’s d for continuous variables) were calculated to provide a measure of clinical relevance where applicable[

30].

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are summarized in

Table 1. The interspinous device group included older patients (mean age: 68.4 ± 9.04 years) compared to the pedicle screws group (mean age: 59.2 ± 10.2 years; p < 0.001). BMI was slightly higher in the pedicle screws group (27.4 ± 4.64) compared to the interspinous device group (26.5 ± 4.44; p < 0.01). No significant differences were observed in gender distribution or comorbidities between groups.

3.2. Surgical and Postoperative Outcomes

The surgical characteristics and hospitalization data are summarized in

Table 2. The surgical time was significantly shorter in the interspinous device group (mean: 39 ± 12 minutes) compared to the pedicle screws group (mean: 72 ± 20 minutes; p < 0.001). Similarly, the incision size was smaller in the interspinous device group (mean: 4.56 ± 1.69 cm) than in the pedicle screws group (mean: 8.91 ± 1.70 cm; p < 0.001). The rate of intraoperative complications was comparable between groups (1.12% vs. 1.34%; p > 0.05); however, postoperative complications were slightly higher in the pedicle screws group (1.88% vs. 0.56%; p < 0.05).

In the interspinous device group, the 4 intraoperative complications included 2 cases of CSF leak and 2 spinous process fractures. In the pedicle screws group, the 5 intraoperative complications consisted of 3 cases of CSF leak and 2 cases of screw repositioning. Regarding postoperative complications, the 2 cases in the interspinous device group were both subfascial hematomas, while in the pedicle screws group, the 7 postoperative complications included 2 subfascial hematomas, 3 cases of postoperative anemia, and 2 infections managed conservatively with antibiotic therapy.

3.3. Functional and Quality of Life Outcomes

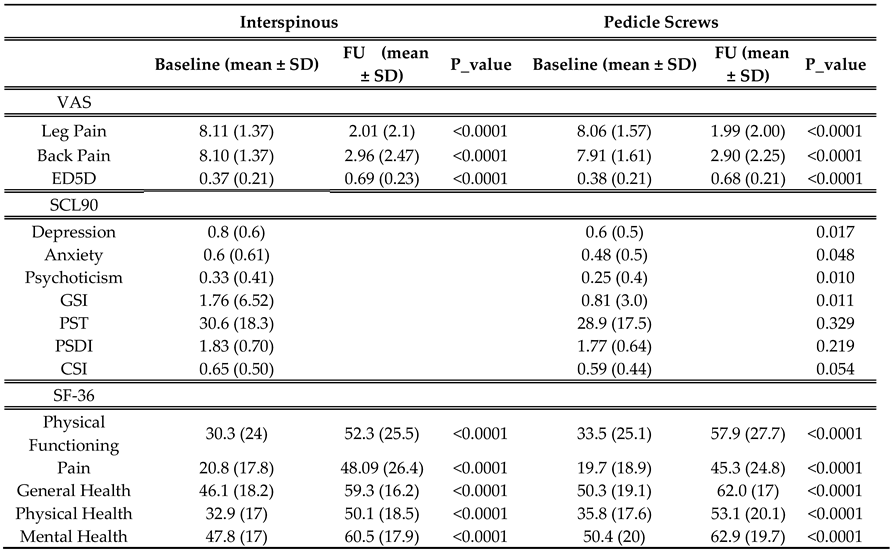

VAS scores for back and leg pain significantly improved postoperatively in both groups with p.value < 0.001 for all comparisons (

Table 3). The mean reduction in VAS leg pain was 6.1 ± 2.1 in the interspinous group and 6.07 ± 2.0 in the pedicle screws group, with no statistically significant difference between the groups (p = 0.87). Similarly, both groups showed marked improvements in back pain (mean reductions: interspinous 5.14 vs. pedicle screws 5.01; p = 0.526). (

Table 4)

Regarding the SCL-90 scales, statistically significant difference between groups were observed for anxiety (p = 0.048), depression (p = 0.017), psychoticism (p = 0.010) and the Global Severity Index (GSI) (p = 0.011).(

Table 3. In addition,

Table 3 show improvements in SF-36 scores were significant across all domains in both groups (p < 0.0001).

Social functioning, pain and general health scores were slightly higher in the interspinous group at follow-up, though when comparing pre- and postoperative differences between the groups, no significant differences emerged (

Table 4).

The EQ-5D index also improved significantly postoperatively in both groups (p < 0.0001), with no significant difference in the extent of improvement between the interspinous group (-0.31) and the pedicle screws group (-0.29; p = 0.253;

Table 4).

The multivariate regression analysis revealed important associations between postoperative outcomes—VAS back pain, VAS leg pain, and EQ-5D—and clinical, psychological, and demographic variables in the interspinous and pedicle screws groups (

Supplementary Materials -

Table S1,

Table S2,

Table S3).

For VAS leg pain, somatization (p = 0.001) emerged as a significant predictor of worse outcomes in the overall cohort and particularly in the pedicle screws group. Paranoid ideation (p = 0.014) and Psychoticism (p = 0.046) also significantly influenced outcomes in the pedicle screws group, highlighting the impact of psychological factors on postoperative pain. Furthermore, improvements in physical functioning and pain domains of the SF-36 were correlated with reductions in leg pain for both groups, underscoring the contribution of physical recovery to pain relief. However, no significant differences between the interspinous and pedicle screws groups were observed when these SF-36 domains were directly compared.

Similarly, for VAS back pain, somatization (p = 0.020) was associated with worse outcomes in both the overall cohort and the pedicle screws group. Additional psychological factors, such as phobic anxiety (p = 0.007) and paranoid ideation (p = 0.006), significantly influenced back pain outcomes in the pedicle screws group. Physical recovery also played a pivotal role, with improvements in the SF-36 domains of role limitations due to physical health (p < 0.0001) and Physical health (p=0.010) being strongly associated with reductions in back pain. These findings suggest an interplay between physical and psychological factors in determining postoperative pain relief.

For EQ-5D, no significant associations were found with psychological variables. Instead, physical health, as measured by the SF-36, emerged as a primary determinant of quality-of-life improvements in both groups. Statistically significant relationship between EQ-5D and Role limitation due to physical health (p=0.021), emotional problems (p=0.012), energie fatigue (p=0.013), emotional well-being (p=0.013), social functioning pain, general (0.010) physical (0.003) and mental(0.013) health were showed in interspinous group. Interestingly, BMI showed a borderline significant negative association with EQ-5D in the overall cohort and in the interspinous group, suggesting that higher BMI may slightly limit perceived quality-of-life improvements.

Regarding demographic factors, age did not consistently predict postoperative outcomes across groups. However, a borderline trend was noted in the interspinous group, where increased age appeared to slightly reduce the improvement in VAS leg pain. BMI, on the other hand, did not significantly influence VAS back pain or leg pain outcomes but showed a weak negative association with physical health recovery in the interspinous group and with quality-of-life improvements in the overall cohort.

4. Discussion

Recognizing the broad spectrum of complications associated with the evolution of pedicle screws, it’s evident that not all patients are suited for such stabilization techniques[

31]. When inserted via the classically minimally invasive midline posterior techniques, interspinous fixation devices (IFDs) provide good resistance to flexion and extension and moderate resistance to lateral bending and axial rotation; thus, these devices are well-suited for spinal fusion and stabilization[

32]. A randomized, controlled, multi-center clinical trial has shown that the Aspen® System could be a significantly faster and less invasive alternative to pedicle screw fixation in support of interbody fusion[

33]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated in biomechanical studies that the implant does not significantly alter the kinematics of the motion segments adjacent to the instrumented level[

34].

Interspinous devices have been combined with procedures such as microdiscectomy, foraminotomy, and interbody fusion. Their use has also been suggested in cases involving unilateral or total facetectomy to provide stabilization. However, there is a lack of biomechanical studies confirming the stability achieved by interspinous devices after unilateral facetectomy, which is known to have destabilizing effects on the spine[

35]. Gonzalez-Blohm et al. analyzed the biomechanical properties of interspinous fusion devices used as standalone solutions, adjuncts to lumbar decompression surgeries, and supplemental support in posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF) constructs. Their findings indicate that IFDs effectively restore flexion-extension stability after unilateral laminotomies. While PLIF constructs combined with IFDs and pedicle screws demonstrated comparable stability in flexion-extension and axial rotation, bilateral pedicle screw PLIF constructs showed superior resistance to lateral bending forces[

36]. This study reinforces the growing body of evidence suggesting that interspinous devices, such as the Aspen®, offer distinct advantages over traditional pedicle screw systems for specific patient populations. The results of this study, in line with previous findings from Gazzeri et al., demonstrate that interspinous devices provide effective stabilization while maintaining a less invasive surgical profile[

37].

One notable advantage of the interspinous fusion device is its significant reduction in operative time and intraoperative blood loss compared to pedicle screw fixation. The shorter duration of surgery and minimally invasive nature of the procedure are particularly beneficial for elderly patients or those with significant comorbidities. These findings underscore the importance of tailoring surgical approaches to patient-specific needs, particularly in high-risk populations such as the elderly.

In terms of clinical outcomes, patients treated with the interspinous fusion device exhibited superior improvements in back pain compared to those treated with pedicle screws. This aligns with the biomechanical advantages of interspinous devices, which are designed to unload stress on the posterior annulus and reduce intradiscal pressure. Additionally, the preservation of surrounding anatomical structures and avoidance of extensive paraspinal muscle dissection contribute to improved postoperative recovery and reduced complications.

Despite these advantages, the use of interspinous devices is not without limitations. Concerns regarding adjacent segment degeneration (ASD) have been raised in the literature. While the reduced rigidity of interspinous devices may protect against hardware-related complications, it could predispose patients to ASD over the long term. Gazzeri et al. reported a higher incidence of ASD in patients treated with interspinous devices compared to those with pedicle screws [

38]. Further long-term studies are needed to better understand the implications of this finding and optimize patient selection criteria.

Moreover, the psychological and functional outcomes observed in this study, assessed using the SCL-90 and SF-36 scales, highlight the holistic benefits of the Aspen® device. Improvements in anxiety, depression, and overall quality of life were observed in both groups, with no statistically significant differences between them. These results emphasize that while the choice of surgical technique is crucial, patient-centered care that addresses psychological and functional recovery is equally important[

39,

40].

The interspinous device group included older patients with higher comorbidity burdens compared to the pedicle screws group. This aligns with previous studies, which have recommended interspinous devices for patients with increased surgical risk or reduced bone quality (e.g., osteoporosis) [

41]. The significant age difference underscores the utility of interspinous devices as a less invasive alternative for patients unable to tolerate longer or more complex procedures. However, the benefits of reduced surgical invasiveness must be balanced against the potential for less robust stabilization compared to pedicle screws in certain patient populations[

42].

Both groups demonstrated significant postoperative improvements in pain and quality of life, with no major differences in the extent of improvement. This supports the growing body of evidence that both stabilization techniques are effective in appropriately selected patients. Notably, the significantly lower rate of postoperative complications in the interspinous group (0.56%) compared to the pedicle screws group (1.88%; p < 0.05) underscores the safety profile of this approach, particularly in elderly or frail patients.

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the strengths of this study, including its robust statistical analysis and detailed patient stratification, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the retrospective design may introduce selection bias. Second, the follow-up period, while sufficient for early outcomes, does not capture long-term durability of the stabilization techniques. Future prospective, randomized studies are needed to validate these findings and explore the impact of these surgical approaches on adjacent segment degeneration and long-term patient satisfaction.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that both pedicle screws and interspinous devices are viable options for lumbar spinal stabilization, with distinct advantages depending on patient characteristics and surgical goals. The choice of technique should be individualized, considering patient age, comorbidities, and anatomical factors. Interspinous devices offer a valuable alternative for patients at higher surgical risk, while pedicle screws remain the gold standard for robust stabilization in younger, healthier patients. The analysis underscores the significant impact of psychological factors on postoperative pain outcomes, highlighting the importance of adopting a comprehensive approach that integrates both physical and psychological aspects to enhance surgical outcomes in patients undergoing lumbar stabilization.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: Multivariate Regression Analysis: Clinical and SCL-90 Factors for VAS Leg Pain and SF-36 Outcomes, Comparing Interspinous Devices and Pedicle Screw Stabilizations.; Table S2: Multivariate Regression Analysis: Clinical and SCL-90 Factors for VAS Back Pain and SF-36 Outcomes, Comparing Interspinous Devices and Pedicle Screw Stabilizations; Table S3: Multivariate Regression Analysis: Clinical and SCL-90 Factors for EQ-5D and SF-36 Outcomes, Comparing Interspinous Devices and Pedicle Screw Stabilizations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, G.G., G.S., G.L.R.; methodology, V.O., G.G., P.B., G.L.R; validation, V.O., G.G., M.B., A.O., G.S., G.L.R. ; formal analysis, V.O., G.G., E.M., F.P., R.A.; investigation, G.G., E.M., F.P., A.C., P.B., R.A.; data curation, G.G., F.P., A.C., M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, V.O., G.G.; writing—review and editing, G.G., G.S., G.L.R.; visualisation, V.O., G.G., E.M., F.P., A.C., P.B., R.A., M.B., A.O.; supervision, A.O., G.S, G.L.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Regione Autonoma Sardegna: protocol number 276/2020/CE (29/10/2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| CSI |

Current Symptom Index |

| EQ-5D |

EuroQol-5 Dimensions |

| GSI |

Global Severity Index |

| ODI |

Oswestry Disability Index |

| PSDI |

Positive Symptom Distress Index |

| PST |

Positive Symptom Total |

| SCL-90 |

Symptom Checklist 90 |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| SF-36 |

Short Form 36 |

| VAS |

Visual Analog Scale |

| VAS-BP |

Visual Analog Scale for Back Pain |

| VAS-LP |

Visual Analog Scale for Leg Pain |

| IFDs |

Interspinous Fixation Devices |

| PLIF |

Posterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion |

| ASD |

Adjacent Segment Degeneration |

| DXA |

Dual-energy X-ray Absorptiometry |

References

- Rault, F.; Briant, A.R.; Kamga, H.; Gaberel, T.; Emery, E. Surgical Management of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis in Patients over 80: Is There an Increased Risk? Neurosurg Rev 2022, 45, 2385–2399. [CrossRef]

- Sait Naderi; Varun R. Kshettry; Ilker Gulec; Edward C. Benzel History of Spine Biomechanics. In Benzel’s Spine Surgery; Edward C. Benzel, Ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, 2016; Vol. 1, pp. 18–27.

- Katz, J.N.; Zimmerman, Z.E.; Mass, H.; Makhni, M.C. Diagnosis and Management of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: A Review. JAMA 2022, 327, 1688–1699. [CrossRef]

- Last, A.R.; Hulbert, K. Chronic Low Back Pain: Evaluation and Management. Am Fam Physician 2009, 79, 1067–1074.

- Staartjes, V.E.; Joswig, H.; Corniola, M. V.; Schaller, K.; Gautschi, O.P.; Stienen, M.N. Association of Medical Comorbidities With Objective Functional Impairment in Lumbar Degenerative Disc Disease. Global Spine J 2022, 12, 1184–1191. [CrossRef]

- La Rocca, G.; Galieri, G.; Mazzucchi, E.; Pignotti, F.; Orlando, V.; Pappalardo, S.; Olivi, A.; Sabatino, G. The Three-Step Approach for Lumbar Disk Herniation with Anatomical Insights Tailored for the Next Generation of Young Spine Surgeons. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, Vol. 13, Page 3571 2024, 13, 3571. [CrossRef]

- Galieri, G.; Mazzucchi, E.; Pignotti, F.; Rinaldi, P.; De Santis, V.; La Rocca, G.; Sabatino, G. Lumbo-Sacral Pedicular Aplasia Diagnosis and Treatment: A Systematic Literature Review and Case Report. Br J Neurosurg 2022. [CrossRef]

- Christopher D. Witiw; John E. O’Toole Cervical, Thoracic, and Lumbar Stenosis. In Youmans and Winn Neurological Surgery; Winn H. Richard, Ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, 2022; Vol. 3, pp. 2497–2509.

- Costa, F.; Alves, O.L.; Anania, C.D.; Zileli, M.; Fornari, M. Decompressive Surgery for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: WFNS Spine Committee Recommendations. World Neurosurg X 2020, 7, 100076. [CrossRef]

- Sigmundsson, F.G.; Kang, X.P.; Jönsson, B.; Strömqvist, B. Prognostic Factors in Lumbar Spinal Stenosis Surgery. Acta Orthop 2012, 83, 536–542. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wei, H.; Zhang, R. Different Lumbar Fusion Techniques for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: A Bayesian Network Meta-Analysis. BMC Surg 2023, 23. [CrossRef]

- Saremi, A.; Goyal, K.K.; Benzel, E.C.; Orr, R.D. Evolution of Lumbar Degenerative Spondylolisthesis with Key Radiographic Features. Spine J 2024, 24, 989–1000. [CrossRef]

- Quattrocchi, C.C.; Alexandre, A.M.; Pepa, G.M.D.; Altavilla, R.; Zobel, B.B. Modic Changes: Anatomy, Pathophysiology and Clinical Correlation. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) 2011, 49–53. [CrossRef]

- Formica, M.; Vallerga, D.; Zanirato, A.; Cavagnaro, L.; Basso, M.; Divano, S.; Mosconi, L.; Quarto, E.; Siri, G.; Felli, L. Fusion Rate and Influence of Surgery-Related Factors in Lumbar Interbody Arthrodesis for Degenerative Spine Diseases: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Musculoskelet Surg 2020, 104. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Liu, S.; Yang, R.; Wang, H. Biomechanical Analysis of a Newly Proposed Surgical Combination (MIS Screw-Rod System for Indirect Decompression+ Interspinous Fusion System for Long Term Spinal Stability) in Treatment of Lumbar Degenerative Diseases. World Neurosurg 2024, 184, e809–e820. [CrossRef]

- Baroudi, M.; Daher, M.; Maheshwari, K.; Singh, M.; Nassar, J.E.; McDonald, C.L.; Diebo, B.G.; Daniels, A.H. Surgical Management of Adult Spinal Deformity Patients with Osteoporosis. J Clin Med 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Pennington, Z.; Lakomkin, N.; Mikula, A.L.; Elsamadicy, A.A.; Astudillo Potes, M.; Fogelson, J.L.; Grossbach, A.J.; Elder, B.D. Decompression Alone Versus Interspinous/Interlaminar Device Placement for Degenerative Lumbar Pathologies: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg 2024, 185, 417-434.e3. [CrossRef]

- Mangal, H.; Felzensztein Recher, D.; Shafafy, R.; Itshayek, E. Effectiveness of Interspinous Process Devices in Managing Adjacent Segment Degeneration Following Lumbar Spinal Fusion: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 5160. [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, J.E.; Khalifeh, K.; Hara, J.; Ozgur, B. Interspinous Process (ISP) Devices in Comparison to the Use of Traditional Posterior Spinal Instrumentation. Cureus 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Shafshak, T.S.; Elnemr, R. The Visual Analogue Scale Versus Numerical Rating Scale in Measuring Pain Severity and Predicting Disability in Low Back Pain. J Clin Rheumatol 2021, 27, 282–285. [CrossRef]

- Koivunen, K.; Widbom-Kolhanen, S.; Pernaa, K.; Arokoski, J.; Saltychev, M. Reliability and Validity of Oswestry Disability Index among Patients Undergoing Lumbar Spinal Surgery. BMC Surg 2024, 24. [CrossRef]

- Apolone, G.; Mosconi, P. The Italian SF-36 Health Survey: Translation, Validation and Norming. J Clin Epidemiol 1998, 51, 1025–1036. [CrossRef]

- La Rocca, G.; Mazzucchi, E.; Pignotti, F.; Nasto, L.A.; Galieri, G.; Rinaldi, P.; De Santis, V.; Pola, E.; Sabatino, G. Navigated, Percutaneous, Three-Step Technique for Lumbar and Sacral Screw Placement: A Novel, Minimally Invasive, and Maximally Safe Strategy. Journal of Orthopaedics and Traumatology 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Rocca, G. La; Galieri, G.; Mazzucchi, E.; Pignotti, F.; Orlando, V.; Pappalardo, S.; Olivi, A.; Sabatino, G. The 3-Steps Approach for Lumbar Stenosis with Anatomical Insights, Tailored for Young Spine Surgeons. J Pers Med 2024, 14, 985. [CrossRef]

- Karnati, T.; Kulubya, E.; Goodarzi, A.; Kim, K.; Karnati, T.; Kulubya, E.; Goodarzi, A.; Kim, K. The Aspen MIS Spinous Process Fusion System. Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery - Advances and Innovations 2021. [CrossRef]

- R: The R Project for Statistical Computing Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Balduzzi, S.; Rücker, G.; Schwarzer, G. How to Perform a Meta-Analysis with R: A Practical Tutorial. Evid Based Ment Health 2019, 22, 153–160. [CrossRef]

- Ergin, M.; Koskan, Ö. Comparison of Student – t, Welch s t, and Mann – Whitney U Tests in Terms of Type I Error Rate and Test Power. Selcuk journal of agriculture and food sciences 2023. [CrossRef]

- Pourhoseingholi, M.A.; Baghestani, A.R.; Vahedi, M. How to Control Confounding Effects by Statistical Analysis. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench 2012, 5, 79.

- Greenland, S.; Senn, S.J.; Rothman, K.J.; Carlin, J.B.; Poole, C.; Goodman, S.N.; Altman, D.G. Statistical Tests, P Values, Confidence Intervals, and Power: A Guide to Misinterpretations. Eur J Epidemiol 2016, 31, 337–350. [CrossRef]

- Filipczyk, P.; Filipczyk, K.; Saulicz, E. Influence of Stabilization Techniques Used in the Treatment of Low Back Pain on the Level of Kinesiophobia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 6393. [CrossRef]

- Lurie, J.; Tomkins-Lane, C. Management of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis. BMJ 2016, 352. [CrossRef]

- Karahalios, D.G.; Kaibara, T.; Porter, R.W.; Kakarla, U.K.; Reyes, P.M.; Baaj, A.A.; Yaqoobi, A.S.; Crawford, N.R. Biomechanics of a Lumbar Interspinous Anchor with Anterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion: Laboratory Investigation. J Neurosurg Spine 2010, 12, 372–380. [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Li, G. X-Stop® Implantation Effectively Limits Segmental Lumbar Extension in-Vivo without Altering the Kinematics of the Adjacent Levels. Turk Neurosurg 2015, 25, 279–284. [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, P.D.; Lindsey, D.P.; Hsu, K.Y.; Zucherman, J.F.; Yerby, S.A. The Use of an Interspinous Implant in Conjunction with a Graded Facetectomy Procedure. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005, 30, 1266–1272. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Blohm, S.A.; Doulgeris, J.J.; Aghayev, K.; Lee, W.E.; Volkov, A.; Vrionis, F.D. Biomechanical Analysis of an Interspinous Fusion Device as a Stand-Alone and as Supplemental Fixation to Posterior Expandable Interbody Cages in the Lumbar Spine. J Neurosurg Spine 2014, 20, 209–219. [CrossRef]

- Gazzeri, R.; Galarza, M.; Alfieri, A. Controversies about Interspinous Process Devices in the Treatment of Degenerative Lumbar Spine Diseases: Past, Present, and Future. Biomed Res Int 2014, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Puzzilli, F.; Gazzeri, R.; Galarza, M.; Neroni, M.; Panagiotopoulos, K.; Bolognini, A.; Callovini, G.; Agrillo, U.; Alfieri, A. Interspinous Spacer Decompression (X-STOP) for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis and Degenerative Disk Disease: A Multicenter Study with a Minimum 3-Year Follow-Up. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2014, 124, 166–174. [CrossRef]

- La Rocca, G.; Orlando, V.; Galieri, G.; Mazzucchi, E.; Pignotti, F.; Cusumano, D.; Bazzu, P.; Olivi, A.; Sabatino, G. Mindfulness vs. Physiotherapy vs. Medical Therapy: Uncovering the Best Postoperative Recovery Method for Low Back Surgery Patients during the COVID-19 Pandemic-A Single Institution’s Experience. J Pers Med 2024, 14, 917. [CrossRef]

- Mazzucchi, E.; La Rocca, G.; Cusumano, D.; Bazzu, P.; Pignotti, F.; Galieri, G.; Rinaldi, P.; De Santis, V.; Sabatino, G. The Role of Psychopathological Symptoms in Lumbar Stenosis: A Prediction Model of Disability after Lumbar Decompression and Fusion. Front Psychol 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Kaye, A.D.; Edinoff, A.N.; Temple, S.N.; Kaye, A.J.; Chami, A.A.; Shah, R.J.; Dixon, B.M.; Alvarado, M.A.; Cornett, E.M.; Viswanath, O.; et al. A Comprehensive Review of Novel Interventional Techniques for Chronic Pain: Spinal Stenosis and Degenerative Disc Disease-MILD Percutaneous Image Guided Lumbar Decompression, Vertiflex Interspinous Spacer, MinuteMan G3 Interspinous-Interlaminar Fusion. Adv Ther 2021, 38, 4628–4645. [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, L.; Piazza, A.; Capobianco, M.; Della Pepa, G.M.; Miscusi, M.; Raco, A.; Scerrati, A.; Somma, T.; Lofrese, G.; Sturiale, C.L. Lumbar Interbody Fusion Using Oblique (OLIF) and Lateral (LLIF) Approaches for Degenerative Spine Disorders: A Meta-Analysis of the Comparative Studies. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2023, 33, 1–7. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Variables.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Variables.

| Variable |

Overall (n=728) |

Interspinous (n=356) |

Pedicle Screws (n=372) |

| Gender (Male, %) |

610 (83.9%) |

296 (83.1%) |

314 (84.6%) |

| Age (years, mean ± SD) |

63.7 ± 10.7 |

68.4 ± 9.04 |

59.2 ± 10.2 |

| Weight (kg) |

75.2 ± 15.5 |

74.4 ± 15.6 |

76.0 ± 15.3 |

| Height (m) |

1.67 ± 0.08 |

1.67 ± 0.08 |

1.66 ± 0.08 |

| BMI (kg/m²) |

26.9 ± 4.6 |

26.5 ± 4.44 |

27.4 ± 4.64 |

| Hypertension (%) |

345 (47.4%) |

198 (55.6%) |

147 (39.5%) |

| Diabetes Mellitus II (%) |

98 (13.5%) |

43 (12.1%) |

55 (14.8%) |

| Cardiovascular Disease (%) |

234 (32.1%) |

135 (37.9%) |

99 (26.6%) |

| Osteoarthritis (%) |

150 (20.6%) |

74 (20.8%) |

76 (20.4%) |

| Previous Spinal Surgery (%) |

107 (14.7%) |

46 (12.9%) |

61 (16.4%) |

| Autoimmune Diseases (%) |

98 (13.5%) |

42 (11.8%) |

56 (15.1%) |

| Neoplasms (%) |

73 (10%) |

35 (9.8%) |

38 (10.2%) |

| Smokers (%) |

239 (32.8%) |

111 (31.2%) |

128 (34.4%) |

Table 2.

Hospitalization and Surgery.

Table 2.

Hospitalization and Surgery.

| Variable |

Overall (n=728) |

Interspinous (n=356) |

Pedicle Screws (n=372) |

| Pathology (%) |

|

|

|

| - Stenosis with instability |

728 (100 %) |

356 (48.9%) |

372 (51.1%) |

| Operated Level (%) |

|

|

|

| - L2-L3 |

16 (2.2%) |

15 (4.2%) |

1 (0.3%) |

| - L3-L4 |

90 (12.4%) |

57 (16.0%) |

33 (8.9%) |

| - L4-L5 |

528 (72.5%) |

244 (68.5%) |

284 (76.3%) |

| - L5-S1 |

93 (12.8%) |

40 (11.2%) |

53 (14.2%) |

| Hospital Stay (days) |

2.7 ± 0.81 |

2.7 ± 0.81 |

2.6 ± 0.70 |

| Preoperative Analgesia (%) |

32 (4.4%) |

0 |

32 (8.6%) |

| Intraoperative Complications (%) |

9 (1.24%) |

4 (1.12%) |

5 (1.34%) |

| Postoperative Complications (%) |

9 (1.24%) |

2 (0.56%) |

7 (1.88%) |

| Surgical time (minute) |

55.9 ± 24.5 |

39 ± 12 |

72 ± 20 |

| Wound Size (cm) |

6,78 ± 2,76 |

4.56 ± 1.69 |

8.91 ± 1.70 |

| Drain Usage (%) |

390 (53.7%) |

27 (7.6%) |

363 (97.8%) |

Table 3.

Comparative analysis of pre- and postoperative outcomes for interspinous devices and pedicle screws.

Table 3.

Comparative analysis of pre- and postoperative outcomes for interspinous devices and pedicle screws.

Table 4.

Test T-Student for comparation of pre- and post-operative differences between interspinous device and pedicle screws.

Table 4.

Test T-Student for comparation of pre- and post-operative differences between interspinous device and pedicle screws.

| |

Interspinous

Mean Pre- and Post-Operative Value |

Pedicle Screws

Mean Pre- and Post-Operative Value |

P-Values |

| VAS |

|

|

|

| Leg pain |

6.10 |

6.07 |

0.873 |

| Back pain |

5.14 |

5.01 |

0.526 |

| ED5D |

-0.31 |

-0.29 |

0.253 |

| SF-36 |

|

|

|

| Physical Functioning |

22.08 |

24.41 |

0.300 |

| Role limitation due to physical health |

6.61 |

3.49 |

0.339 |

| Role limitation due to emotional problems |

12.76 |

17.56 |

0.258 |

| Energie fatigue |

13.52 |

13.86 |

0.848 |

| Emotional well being |

9.45 |

10.11 |

0.678 |

| Social Functioning |

16.71 |

12.93 |

0.101 |

| Pain |

27.19 |

25.56 |

0.472 |

| General Health |

13.17 |

11.73 |

0.306 |

| Physical Health |

17.29 |

17.26 |

0.987 |

| Mental Health |

12.64 |

12.59 |

0.970 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).