1. Introduction

The reported complication rates following adult spinal deformity (ASD) surgery are as high as 70% [

1], with pseudarthrosis being the major reason for a revision surgery [

2]. In particular, rod fracture (RF), the most common form of pseudarthrosis, may occur even when radiographical findings show solid bone union. Accordingly, various treatment strategies for reducing the incidence of RF following surgical treatment of ASD are reported in the literature [

3,

4].

ASD patients who receive deformity correction are not free from the risk of RF. Many studies to date have analyzed the related risk factors [

4,

5], compared the procedure-related complication risks between primary and revision surgeries [

6], and explored the various complications after revision surgery [

7] in the setting of ASD. However, long-term follow-up studies assessing the outcomes after revision surgeries due to RF are sparse.

In general, patients with RF are strongly advised to undergo revision, not only to reduce associated pain, but also to prevent potential deterioration of sagittal balance that may result from the collapse of vertebral body at the pedicle subtraction osteotomy (PSO) site [

3]. Although a revision surgery for RF is traditionally performed through rod replacement and supplementary posterior fusion, several alternative methods have been introduced in recent years, to enhance fusion above and below the osteotomy site through a minimally invasive lateral approach, and to increase both the stiffness and stability of the construct by integrating accessory rods into previous instrumentation [

8,

9].

The current study was conducted on ASD patients who underwent primary deformity correction via PSO and subsequent revision surgery due to RF with one of the three major revision techniques: 1) simple rod replacement, 2) lateral lumbar interbody fusion (LLIF) above and below the PSO site, and 3) accessory rod integration. This study analyzed the long-term results, including the incidence of recurrent RF (re-RF) and the radiographical parameters, for each revision procedure.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This retrospective study reviewed 139 consecutive ASD patients aged ≥65 years enrolled from 2002 to 2020 with a minimum 2-year follow-up after deformity correction via PSO. The inclusion criteria were as follows:

(1) Sagittal malalignment (sagittal vertical axis [SVA] >50 mm, pelvic incidence [PI] minus lumbar lordosis [LL] mismatch >10°, and pelvic tilt [PT] >25°).

(2) Long segment fixation with the uppermost and lowermost instrumented vertebrae at the T10 and S1, respectively.

(3) Atrophy of the back musculature in the cross-section area of magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography (CT) in the diagnosis of lumbar degenerative kyphosis (LDK) and notable clinical signs, as previously described [

10].

(4) Identification of RF, based on rod breakage with recent fusion mass fracture observed on plain radiography and CT, confirmed by uptakes in either bone scan or bone single-photon emission CT.

The patients were classified into three groups according to the received revision procedure: simple rod replacement (SR group), lateral lumbar interbody fusion above and below the PSO site (LLIF group), and accessory rod integration (AR group).

2.2. Surgical Method

With each patient in prone position, the standard posterior midline approach was made to expose the implant and confirm the site of RF. Patients in the SR group underwent bilateral replacement of previously inserted rods, only. Those in the LLIF group received bilateral rod replacement with interbody fusions above and below the PSO site. Lastly, patients in the AR group received bilateral rod replacement with AR integration by bending both the upper and lower ends of an AR and connecting the bent pair to the newly replaced rods with connectors.

2.3. Radiographic Measurements

Sagittal alignment was evaluated using lateral 14×36-inch full spine radiographs obtained with the patients standing in a neutral unsupported position with “fists-on-clavicle” [

11]. All digital radiographs were analyzed using validated software (Surgimap, Nemaris Inc., New York, NY). We evaluated PI, sacral slope (SS), PT, thoracic kyphosis (TK), thoracolumbar junction (TL), LL, lumbosacral junction (LS), and SVA. Sagittal Cobb angles were measured for TK (T5–12), TL (T10–L2), LL (T12–S1), and LS (L4–S1) [

9,

10]. PI, PT, and SS were measured using a standing lateral radiograph of the pelvis according to methods described previously [

12].

2.4. RF Analysis

RF occurrence, RF site (vertebral level), and RF side (unilateral vs. bilateral) were evaluated. The surgical factors (sacropelvic fixation application and L5-S1 fusion method) were also analyzed.

2.5. Clinical Outcome Measurements

Clinical outcomes were assessed using Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) and Visual Analog Scale (VAS) preoperatively, postoperatively, and at last follow-up prior to the occurrence of RF. In addition, age, bone mineral density (BMD), and body mass index (BMI), were also analyzed.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Continuous variables were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), Welch’s robust ANOVA, Bonferroni’s method, Tukey HSD method, and Dunnett T3 method for variables with normal distributions, and Kruskal–Wallis test and Mann-Whitney method for variables without normal distributions. Categorical variables were assessed using chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. A p-value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients with RF

Patients were referred to the outpatient clinic after a startling crack sound with accompanying back pain. RF occurred in 47 patients (34%) at an average of 28 months after primary deformity correction with a mean age of 69.7 years. RF occurred at the PSO site in 39 patients (83%) and at L4-5 level in 8 patients (17%). Bilateral and unilateral RF were observed in 23 and 24 patients, respectively. 33 patients had sacropelvic fixation, and 31 and 16 patients had received ALIF and PLIF, respectively, for L5-S1 interbody fusion. Each patient received one of the following revision surgery procedures: 1) simple bilateral rod replacement (n=17), 2) bilateral rod replacement with LLIF around PSO site (n=8), or 3) bilateral rod replacement with accessory rod integration (n=22).

3.2. Characteristics of Re-RF

Table 1 presents the characteristics of patients with re-RF. Re-RF occurred in six patients (13%) at an average of 37 months (one unilateral RF and five bilateral RF). Re-RF occurred most commonly in the SR group (p=.048); five patients (29.4%) at 15, 18, 25, 36, and 96 months, postoperatively. There was no re-RF in the LLIF group. Re-RF occurred in one patient in the AR group at 29 months, postoperatively. Every re-RF in the SR group occurred at the PSO site, while one bilateral re-RF in the AR group occurred at L4–5 level just below each junction between the distal end of AR and the primary rod. Every patient with re-RF underwent a re-revision procedure, while one asymptomatic patient with unilateral RF underwent close observation from refusal of surgical intervention.

3.3. Radiographic and Surgical Features of Re-RF Patients

Table 2 shows the radiographic parameters of the three groups. Although preoperative SVA was larger in the AR group than those in the other groups (p=.034), patients in all groups showed severe sagittal malalignment before primary deformity surgery. After both deformity correction and revision surgery for RF, the spinopelvic parameters of all groups showed favorable results, and sagittal alignment was well maintained prior to the occurrence of re-RF, without significant intergroup differences. Also, there were no significant differences between groups with respect to sacropelvic fixation application and L5-S1 fusion method (ALIF or PLIF) (

Table 1).

3.4. Clinical Outcomes

The VAS for back pain and radiating pain, as well as ODI, had all improved after primary deformity surgery prior to RF, without significant intergroup differences (

Table 3). The lack of such differences in clinical outcomes could be attributed to the fact that the patients included in this study were elderly (age ≥65 years) with severe baseline sagittal imbalance and both relatively high ODI and VAS scores, preoperatively. Thus, along with spinopelvic harmony, the leveled horizontal gaze and normal upright posture had already been recovered through sufficient decompression and deformity correction, which enhanced their quality of life to a great extent. Additionally, patient factors including age, BMI, and BMD also did not significantly differ between the three groups (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

The restoration of sagittal balance is the main goal in the surgical treatment of ASD. Among the deformity correction methods in ASD, PSO is understandably one of the most powerful methods for achieving an ideal LL correction, which is fundamental in obtaining and maintaining optimal sagittal balance [

13]. Still, there remain an array of challenges stemming from not only the complexity of the procedure itself, but also from the many known complications of PSO, including RF [

14,

15]. Accordingly, various methods to prevent RF have been reported, such as the combination of sacropelvic fixation with long segment fusion to increase construct stability via lumbosacral fusion [

16], and the integration of multiple rod constructs for proper load distribution and posterior reinforcement at the PSO site [

3].

In the setting of deformity correction of ASD, however, studies analyzing the appropriate surgical methods for revision, the long-term follow-up outcomes after revision, and the incidences of re-RF are lacking. Therefore, our study was significant in that it is the first to report on long-term outcomes with a minimum follow-up duration of 2 years, of the three different revision methods for RF – simple bilateral rod replacement, bilateral rod replacement with LLIF around the PSO site, and bilateral rod replacement with accessory rod integration – in ASD patients who have previously received deformity correction via long level fusion with PSO.

Simple Bilateral Rod Replacement

Our study findings revealed the incidence of re-RF following revision surgery due to RF to be 13%. Of the three revision methods, simple bilateral rod replacement (SR group) showed the highest incidence of re-RF. We believe that the hyper-acutely contoured posterior rods paralleling a relatively large angular correction in PSO, could have progressively intensified the stress concentration and lowered the fatigue strength of each rod [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21], which consequently may have led to rod-breakage. Furthermore, the fact that every re-RF in the SR group occurred consistently at the same PSO site (

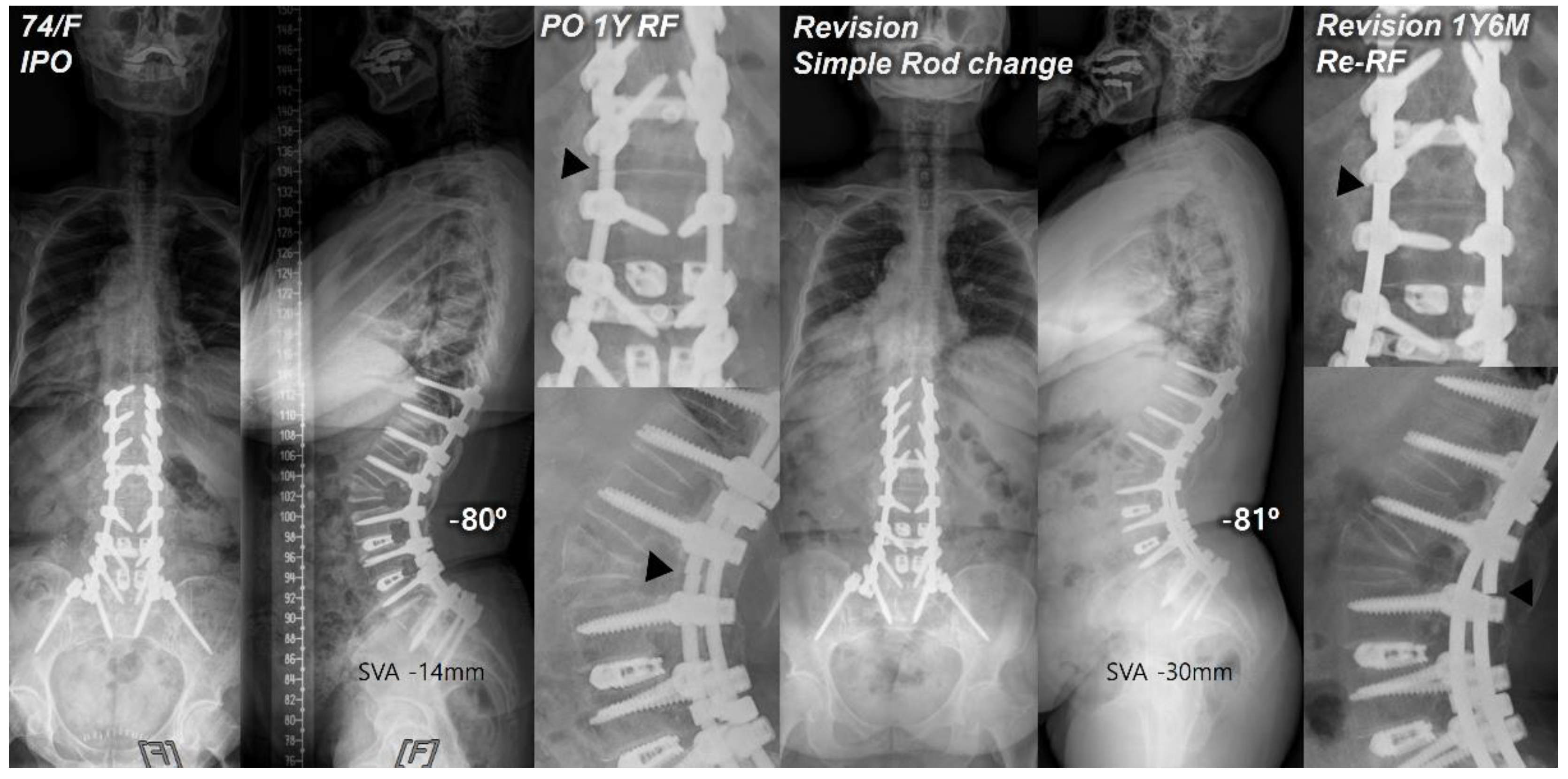

Figure 1), not only suggests that simple bilateral rod replacement alone has a high risk of re-RF, but also proves that additional support around the PSO site is ultimately required to prevent RF and maintain sagittal balance in PSO.

Bilateral Rod Replacement with Accessory Rod Integration

Posterior reinforcement at the PSO site with multiple-rod fixation for appropriate load distribution is a crucial preventive method for RF. Numerous finite element models have demonstrated the effectiveness of additional rods in reducing stress on the primary rods across the osteotomy site [

22,

23]. Several clinical studies also have reported that multiple-rod fixation reduced the occurrence of RF and increased the stability at the osteotomy site [

3,

9]. A biomechanical study by Scheer et al. [

24] that analyzed revision strategies for RF in PSO reported that multiple-rod fixation could restore stiffness and prevent fatigue of revision constructs. Therefore, multiple-rod fixation should offer a proven biomechanical stability in revision for RF. However, RF can still occur even with reinforcement. In our study, re-RF occurred in one of 22 patients in the AR group. Interestingly, instead of occurring at the PSO site, it occurred just below each junction between the distal end of the AR and the primary rod (

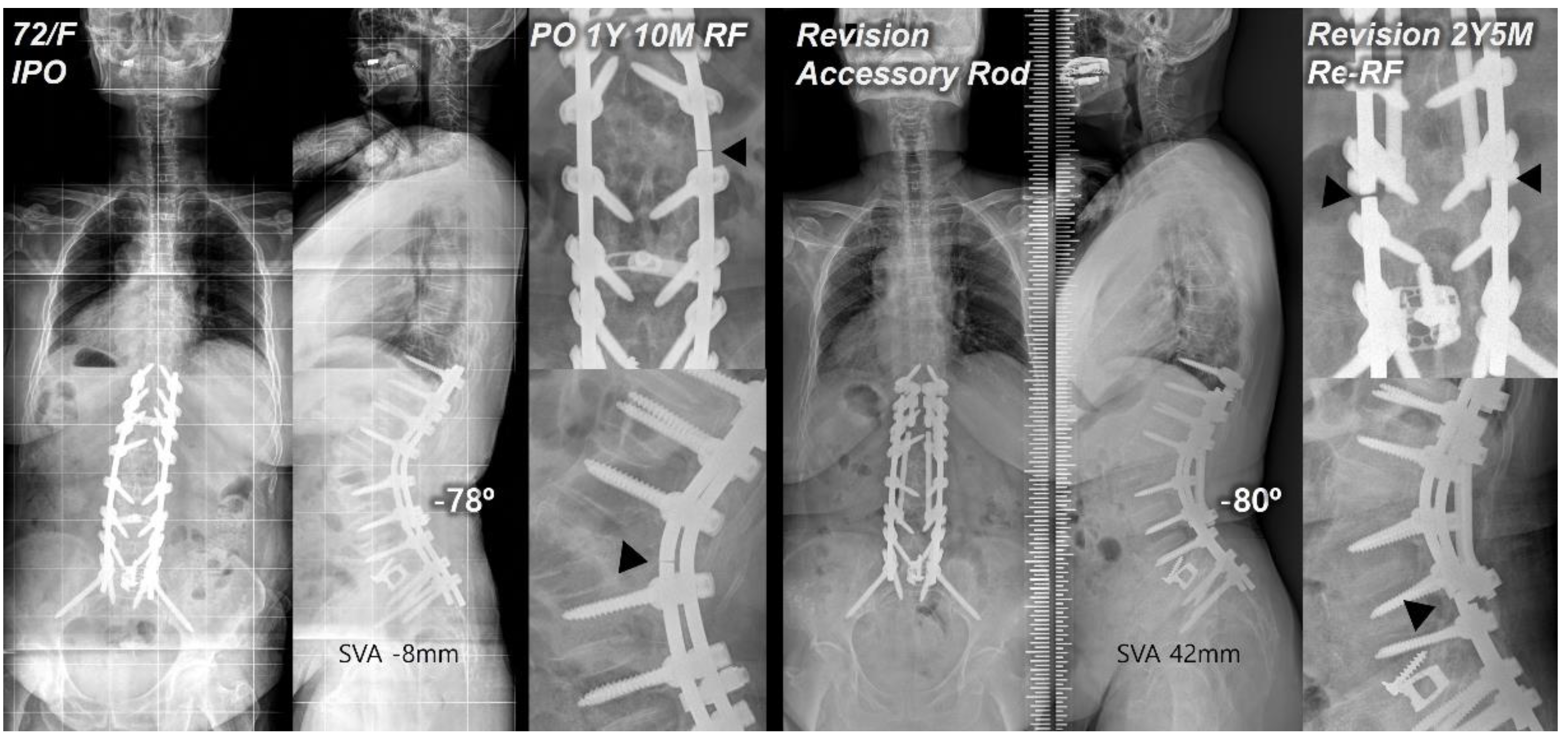

Figure 2). We believe that, in the application of multiple-rods, connecting the distal end of the AR to the previous instrumentation at the S1-2 area could potentially offer increased stability in conjunction with L5-S1 interbody fusion and sacropelvic fixation, but further studies are warranted.

Bilateral Rod Replacement with LLIF around the PSO Site

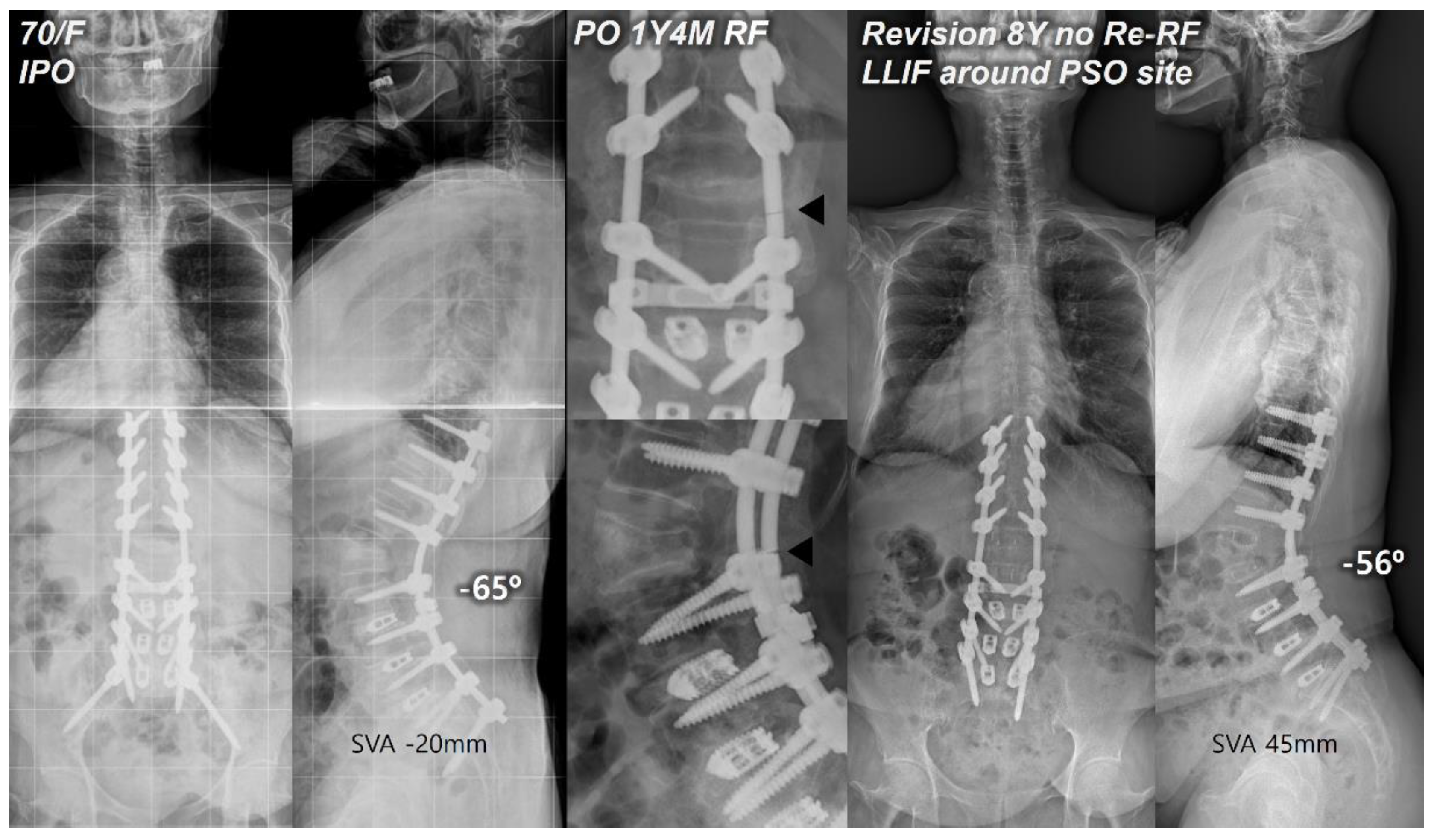

None of the patients in the LLIF group had experienced re-RF (

Figure 3). This result can be attributed to the reduced residual sagittal motion of the construct, the increased stress distribution through anterior support, and the enhanced stability via interbody fusion immediately above and below the PSO site [

25]. This finding was consistent with that of a cadaveric study by Deviren et al. [

26], which showed increased stability through placement of interbody cages above and below the PSO site in multiaxial bending conditions. Luca et al. [

8] also reported that the management of revision surgery after PSO may require an addition of anterior column support to maintain correction and reduce complications. In the same vein, Dickson et al. [

27] recommended interbody fusion above and below the PSO site to help reduce the risk of further pseudarthrosis. Therefore, providing the anterior column support through interbody work around the PSO site by either lateral or anterior approach may be a promising method for revision due to RF. However, further comparative studies are needed to assess the effectiveness of LLIF technique with respect to the prevention of RF and postoperative complications.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, several variables may exist due to its retrospective nature. Second, this study examined only the patients who underwent deformity correction via PSO and subsequent revision procedures due to RF. Therefore, the number of patients with re-RF was relatively small, and the study findings may have limited implications. However, despite its limitations, this study is the first to compare the incidence of re-RF and analyze different revision methods for RF in the setting of ASD surgery.

5. Conclusions

For ASD patients, various revision surgery methods are available for RF following deformity correction. Our results showed that accessory rod integration or additional LLIF around the PSO site was superior to simple rod replacement in the prevention of re-RF. Therefore, any revision surgery for RF after deformity correction with PSO should consider incorporating additional support to provide greater strength and stability to the previous construct. Our findings should provide an effective guideline for revisions due to RF following long posterior spinal fusion with PSO.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.Y.L. and J.-H.L.; methodology, K.Y.L. and J.-H.L.; software, K.Y.L.; validation, K.Y.L., J.-H.L., G.H., C.H.J.; formal analysis, K.Y.L., J.-H.L., G.H., C.H.J., H.S.P.; investigation, K.Y.L., L.J.H., G.H., C.H.J., H.S.P.; resources, J.-H.L.; data curation, J.-H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, K.Y.L., J.-H.L., G.H., C.H.J.; writing—review and editing, K.Y.L., J.-H.L., G.H., C.H.J.; visualization, K.Y.L., J.-H.L., G.H., C.H.J.; supervision, J.-H.L.; project administration, J.-H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by our institutional review board (approval number: KMC IRB: 2023-03-053).

Informed Consent Statement

The need for informed consent was waived because our study was performed retrospectively.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available, as participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Smith, J. S.; Klineberg, E.; Lafage, V.; Shaffrey, C. I.; Schwab, F.; Lafage, R.; Hostin, R.; Mundis, G. M., Jr.; Errico, T. J.; Kim, H. J.; et al. Prospective multicenter assessment of perioperative and minimum 2-year postoperative complication rates associated with adult spinal deformity surgery. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2016, 25, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y. J.; Bridwell, K. H.; Lenke, L. G.; Cheh, G.; Baldus, C. Results of lumbar pedicle subtraction osteotomies for fixed sagittal imbalance: a minimum 5-year follow-up study. Spine 2007, 32, 2189–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K. Y.; Lee, J. H.; Kang, K. C.; Im, S. K.; Lim, H. S.; Choi, S. W. Strategies for prevention of rod fracture in adult spinal deformity: cobalt chrome rod, accessory rod technique, and lateral lumbar interbody fusion. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J. S.; Shaffrey, E.; Klineberg, E.; Shaffrey, C. I.; Lafage, V.; Schwab, F. J.; Protopsaltis, T.; Scheer, J. K.; Mundis, G. M., Jr.; Fu, K. M.; et al. Prospective multicenter assessment of risk factors for rod fracture following surgery for adult spinal deformity. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2014, 21, 994–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J. S.; Shaffrey, C. I.; Ames, C. P.; Demakakos, J.; Fu, K. M.; Keshavarzi, S.; Li, C. M.; Deviren, V.; Schwab, F. J.; Lafage, V.; et al. Assessment of symptomatic rod fracture after posterior instrumented fusion for adult spinal deformity. Neurosurg 2012, 71, 862–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diebo, B. G.; Passias, P. G.; Marascalchi, B. J.; Jalai, C. M.; Worley, N. J.; Errico, T. J.; Lafage, V. Primary Versus Revision Surgery in the Setting of Adult Spinal Deformity: A Nationwide Study on 10,912 Patients. Spine 2015, 40, 1674–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S. K.; Bridwell, K. H.; Lenke, L. G.; Yi, J. S.; Pahys, J. M.; Zebala, L. P.; Kang, M. M.; Cho, W.; Baldus, C. R. Major complications in revision adult deformity surgery: risk factors and clinical outcomes with 2- to 7-year follow-up. Spine 2012, 37, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luca, A.; Lovi, A.; Galbusera, F.; Brayda-Bruno, M. Revision surgery after PSO failure with rod breakage: a comparison of different techniques. Eur. Spine J. 2014, 23 Suppl 6, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S. J.; Lenke, L. G.; Kim, Y. C.; Koester, L. A.; Blanke, K. M. Comparison of standard 2-rod constructs to multiple-rod constructs for fixation across 3-column spinal osteotomies. Spine 2014, 39, 1899–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takemitsu, Y.; Harada, Y.; Iwahara, T.; Miyamoto, M.; Miyatake, Y. Lumbar degenerative kyphosis. Clinical, radiological and epidemiological studies. Spine 1988, 13, 1317–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, W. C.; Brown, C. W.; Bridwell, K. H.; Glassman, S. D.; Suk, S. I.; Cha, C. W. Is there an optimal patient stance for obtaining a lateral 36" radiograph? A critical comparison of three techniques. Spine 2005, 30, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legaye, J.; Duval-Beaupère, G.; Hecquet, J.; Marty, C. Pelvic incidence: a fundamental pelvic parameter for three-dimensional regulation of spinal sagittal curves. Eur. Spine J. 1998, 7, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.-H.; Kim, K.-T.; Lee, S.-H.; Kang, K.-C.; Oh, H.-S.; Kim, Y.-J.; Jung, H. Overcorrection of lumbar lordosis for adult spinal deformity with sagittal imbalance: comparison of radiographic outcomes between overcorrection and undercorrection. Eur. Spine J. 2016, 25, 2668–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridwell, K. H.; Lewis, S. J.; Edwards, C.; Lenke, L. G.; Iffrig, T. M.; Berra, A.; Baldus, C.; Blanke, K. Complications and outcomes of pedicle subtraction osteotomies for fixed sagittal imbalance. Spine 2003, 28, 2093–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S. J.; Rhim, S. C. Clinical outcomes and complications after pedicle subtraction osteotomy for fixed sagittal imbalance patients : a long-term follow-up data. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 2010, 47, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. Y.; Lee, J. H.; Kang, K. C.; Shin, S. J.; Shin, W. J.; Im, S. K.; Park, J. H. Strategy for obtaining solid fusion at L5-S1 in adult spinal deformity: risk factor analysis for nonunion at L5-S1. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J. A.; Leasure, J. M.; Smith, J. S.; Buckley, J. M.; Kondrashov, D.; Ames, C. P. Effect of severity of rod contour on posterior rod failure in the setting of lumbar pedicle subtraction osteotomy (PSO): a biomechanical study. Neurosurg. 2013, 72, 276–282; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, C.; Deviren, V.; Xu, Z.; Yeh, R. F.; Puttlitz, C. M. The effects of rod contouring on spinal construct fatigue strength. Spine 2006, 31, 1680–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotani, Y.; Cunningham, B. W.; Parker, L. M.; Kanayama, M.; McAfee, P. C. Static and fatigue biomechanical properties of anterior thoracolumbar instrumentation systems. A synthetic testing model. Spine 1999, 24, 1406–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, B. W.; Sefter, J. C.; Shono, Y.; McAfee, P. C. Static and cyclical biomechanical analysis of pedicle screw spinal constructs. Spine 1993, 18, 1677–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, J. C.; Bourgeault, C. A. Notch sensitivity of titanium alloy, commercially pure titanium, and stainless steel spinal implants. Spine 2001, 26, 1668–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luca, A.; Ottardi, C.; Sasso, M.; Prosdocimo, L.; La Barbera, L.; Brayda-Bruno, M.; Galbusera, F.; Villa, T. Instrumentation failure following pedicle subtraction osteotomy: the role of rod material, diameter, and multi-rod constructs. Eur. Spine J. 2017, 26, 764–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Januszewski, J.; Beckman, J. M.; Harris, J. E.; Turner, A. W.; Yen, C. P.; Uribe, J. S. Biomechanical study of rod stress after pedicle subtraction osteotomy versus anterior column reconstruction: A finite element study. Surg. Neurolo. Int. 2017, 8, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheer, J. K.; Tang, J. A.; Deviren, V.; Buckley, J. M.; Pekmezci, M.; McClellan, R. T.; Ames, C. P. Biomechanical analysis of revision strategies for rod fracture in pedicle subtraction osteotomy. Neurosurg. 2011, 69, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godzik, J.; Haglin, J. M.; Alan, N.; Hlubek, R. J.; Walker, C. T.; Bach, K.; Mundis, G. M., Jr.; Turner, J. D.; Kanter, A. S.; Okonwko, D. O.; et al. Retrospective Multicenter Assessment of Rod Fracture After Anterior Column Realignment in Minimally Invasive Adult Spinal Deformity Correction. World Neurosurg. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deviren, V.; Tang, J. A.; Scheer, J. K.; Buckley, J. M.; Pekmezci, M.; McClellan, R. T.; Ames, C. P. Construct Rigidity after Fatigue Loading in Pedicle Subtraction Osteotomy with or without Adjacent Interbody Structural Cages. Glob. Spine J. 2012, 2, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, D. D.; Lenke, L. G.; Bridwell, K. H.; Koester, L. A. Risk factors for and assessment of symptomatic pseudarthrosis after lumbar pedicle subtraction osteotomy in adult spinal deformity. Spine 2014, 39, 1190–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Postoperative standing radiographs of a 74-year-old female patient after T10-S1 posterior instrumentation with PSO on L2, PLIF on L3-5, and ALIF on L5-S1 with an optimal sagittal balance (SVA, -14 mm; TK, 28°; LL, -80°; PI, 54°; PT, 4°; SS, 50°). At 1 year after primary deformity correction, RF (left rod) occurred at L2. At 1 year and 6 months following revision surgery with simple bilateral rod replacement, re-RF occurred at L2-3. Black triangles indicate the site of RF.

Figure 1.

Postoperative standing radiographs of a 74-year-old female patient after T10-S1 posterior instrumentation with PSO on L2, PLIF on L3-5, and ALIF on L5-S1 with an optimal sagittal balance (SVA, -14 mm; TK, 28°; LL, -80°; PI, 54°; PT, 4°; SS, 50°). At 1 year after primary deformity correction, RF (left rod) occurred at L2. At 1 year and 6 months following revision surgery with simple bilateral rod replacement, re-RF occurred at L2-3. Black triangles indicate the site of RF.

Figure 2.

Postoperative standing radiographs of a 72-year-old female patient after T10-S1 posterior instrumentation with PSO on L2, and ALIF on L5-S1 with an optimal sagittal balance (SVA, -8 mm; TK, 27°; LL, -78°; PI, 60°; PT, 12°; SS, 48°). At 1 year and 10 months after primary deformity correction, RF (right rod) occurred at L2-3. At two years and 5 months following revision surgery with bilateral rod replacement and accessory rod integration, re-RF occurred at L4-5. Black triangles indicate sites of RF.

Figure 2.

Postoperative standing radiographs of a 72-year-old female patient after T10-S1 posterior instrumentation with PSO on L2, and ALIF on L5-S1 with an optimal sagittal balance (SVA, -8 mm; TK, 27°; LL, -78°; PI, 60°; PT, 12°; SS, 48°). At 1 year and 10 months after primary deformity correction, RF (right rod) occurred at L2-3. At two years and 5 months following revision surgery with bilateral rod replacement and accessory rod integration, re-RF occurred at L4-5. Black triangles indicate sites of RF.

Figure 3.

Postoperative standing radiographs of a 70-year-old female patient after T10-S1 posterior instrumentation with PSO on L2, and PLIF on L3-S1 with an optimal sagittal balance (SVA, -20 mm; TK, 12°; LL, -65°; PI, 57°; PT, 17°; SS, 40°). At 1 year and 4 months after primary deformity correction, RF (right rod) occurred at L2-3. At 8 years following revision surgery with bilateral rod replacement and LLIF around the PSO site, sagittal alignment was well-maintained without re-RF. Black triangles indicate the site of RF.

Figure 3.

Postoperative standing radiographs of a 70-year-old female patient after T10-S1 posterior instrumentation with PSO on L2, and PLIF on L3-S1 with an optimal sagittal balance (SVA, -20 mm; TK, 12°; LL, -65°; PI, 57°; PT, 17°; SS, 40°). At 1 year and 4 months after primary deformity correction, RF (right rod) occurred at L2-3. At 8 years following revision surgery with bilateral rod replacement and LLIF around the PSO site, sagittal alignment was well-maintained without re-RF. Black triangles indicate the site of RF.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of re-RF patients.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of re-RF patients.

| Variables |

SR group

(n=15) |

LLIF group

(n=9) |

AR group

(n=12) |

p-value |

| Re-RF (n=6) |

5/12

(29.4%) |

0/8

(0%) |

1/21

(4.5%) |

0.048*1

|

RF detection time

(month) |

38 |

- |

29 |

- |

| RF site (level) |

L2-3 |

- |

L4-5 |

- |

| RF side |

1 right

4 both |

- |

both |

- |

| Sacropelvic fixation |

9/8 |

6/2 |

18/4 |

0.1821

|

| ALIF/PLIF |

11/6 |

4/4 |

16/6 |

0.5081

|

Table 2.

Comparison of radiographic parameters between groups†.

Table 2.

Comparison of radiographic parameters between groups†.

| Variables |

SR group

(n=15) |

LLIF group

(n=9) |

AR group

(n=12) |

p-value |

| Sagittal vertical axis (SVA, mm) |

| Pre SVA |

169.9 ± 67.1 |

169 ± 74.5 |

236.4 ± 98.1 |

0.034* |

| Post SVA |

-16.5 ± 17.3 |

-20.8 ± 29.6 |

-16.4 ± 27.7 |

0.901 |

| SVA correction |

-186.4 ± 72 |

-189.8 ± 84.7 |

-252.7 ± 97.8 |

0.047* |

| Post Rev SVA |

16 ± 33.8 |

6.3 ± 25.4 |

13.1 ± 37.4 |

0.805 |

| Last SVA |

36.5 ± 27.6 |

24.8 ± 9.7 |

22.4 ± 33 |

0.304 |

| Thoracic kyphosis (TK, °) |

| Pre TK |

-2.8 ± 12 |

-1 ± 13.5 |

10.9 ± 37.8 |

0.407 |

| Post TK |

18.2 ± 15.1 |

22.6 ± 9.6 |

27.5 ± 10.1 |

0.069 |

| Post Rev TK |

32.1 ± 11.7 |

27.6 ± 13 |

35.6 ± 12.1 |

0.267 |

| Last TK |

31.9 ± 12 |

31.9 ± 13.3 |

39.7 ± 14.4 |

0.150 |

| Thoracolumbar junctional angle (TL, °) |

| Pre TL |

7.5 ± 18.1 |

1.4 ± 17.2 |

11.2 ± 16.6 |

0.389 |

| Post TL |

-22.3 ± 19.1 |

-11.8 ± 23.1 |

-25.4 ± 16.1 |

0.345 |

| Post Rev TL |

-17.8 ± 22.2 |

-18.4 ± 16.9 |

-21.8 ± 9 |

0.971 |

| Last TL |

-17.4 ± 19.5 |

-15.4 ± 16.7 |

-20.4 ± 11.9 |

0.697 |

| Lumbar lordosis (LL, °) |

| Pre LL |

7.6 ± 16.3 |

7.5 ± 14.5 |

11.2 ± 17.5 |

0.988 |

| Post LL |

-66.6 ± 16 |

-62.4 ± 7.4 |

-77.7 ± 24 |

0.093 |

| LL correction |

-74.2 ± 19.4 |

-70 ± 17.6 |

-88.9 ± 26.4 |

0.108 |

| Post Rev LL |

-61.6 ± 16.1 |

-62.6 ± 7.8 |

-70.4 ± 9.5 |

0.065 |

| Last LL |

-59 ± 23.5 |

-53.3 ± 25.5 |

-65.3 ± 18.6 |

0.376 |

| Lumbosacral junctional angle (LS, °) |

| Pre LS |

-5.6 ± 19.1 |

0.4 ± 12.7 |

2.4 ± 15.1 |

0.383 |

| Post LS |

-24.8 ± 8.8 |

-27.4 ± 7.4 |

-27.7 ± 11.2 |

0.746 |

| Post Rev LS |

-22.1 ± 8.8 |

-27 ± 7.7 |

-29.4 ± 9.3 |

0.051 |

| Last LS |

-25.6 ± 8.7 |

-19 ± 11.9 |

-27.9 ± 11.7 |

0.214 |

| Pelvic incidence (°) |

55.5 ± 11.2 |

51 ± 10.2 |

57.5 ± 9.8 |

0.326 |

| Sacral slope (SS, °) |

| Preoperative SS |

17.1 ± 14.5 |

21 ± 12.3 |

21.3 ± 13.1 |

0.604 |

| Postoperative SS |

42.3 ± 11.8 |

38.4 ± 6.9 |

45.7 ± 8.4 |

0.177 |

| Post Rev SS |

39.7 ± 13.3 |

40.1 ± 3.9 |

46.4 ± 7.4 |

0.074 |

| Last SS |

41.7 ± 13.4 |

39.4 ± 7.1 |

43.9 ± 8 |

0.538 |

| Pelvic tilt (PT, °) |

| Preoperative PT |

38.4 ± 15.1 |

30 ± 11.3 |

36.2 ± 11.6 |

0.317 |

| Postoperative PT |

16.1 ± 9.5 |

16.3 ± 8.3 |

14.4 ± 15.6 |

0.894 |

| Post Rev PT |

15.8 ± 12.9 |

11.5 ± 7.2 |

10.8 ± 11.4 |

0.386 |

| Last PT |

13.8 ± 12.4 |

12.3 ± 8.2 |

13.4 ± 10.4 |

0.945 |

| PI-LL (°) |

| Pre PI-LL |

63.1 ± 20.9 |

58.5 ± 17 |

68.7 ± 19.1 |

0.783 |

| Post PI-LL |

-11.1 ± 14.5 |

-11.5 ± 6.8 |

-20.2 ± 25.4 |

0.428 |

| Post Rev PI-LL |

-6.1 ± 16.3 |

-11.7 ± 8.6 |

-13 ± 11.7 |

0.263 |

| Last PI-LL |

-5.7 ± 19 |

-8 ± 10.7 |

-9.7 ± 12.5 |

0.714 |

Table 3.

Comparison of clinical parameters between groups†.

Table 3.

Comparison of clinical parameters between groups†.

| Variables |

SR group(n=15) |

LLIF group

(n=9) |

AR group

(n=12) |

p-value |

| Age (year) |

68.7 ± 6.4 |

69.3 ± 6.3 |

70.7 ± 5 |

0.522 |

| BMD (gm/cm2) |

0.89 ± 0.18 |

1.02 ± 0.11 |

0.93 ± 0.16 |

0.184 |

BMD T-score

(gm/cm2) |

-1.96 ± 1.56 |

-.99 ± 1.08 |

-1.64 ± 1.45 |

0.301 |

| BMI (kg/m2) |

24.8 ± 3.7 |

27.3 ± 2.8 |

24.7 ± 3.7 |

0.211 |

| Pre ODI |

37.5 ± 2.7 |

37.9 ± 3.5 |

38.2 ± 2.4 |

0.675 |

| Post ODI |

18.8 ± 6 |

17.3 ± 4.7 |

19.9 ± 4 |

0.419 |

| Last ODI |

10.2 ± 4.2 |

10 ± 4.8 |

9.6 ± 3.6 |

0.986 |

| Pre LBP VAS |

8.1 ± 1.3 |

8.4 ± 1.2 |

8.6 ± 0.9 |

0.654 |

| Post LBP VAS |

4.5 ± 2 |

4.1 ± 2.4 |

5 ± 1.7 |

0.537 |

| Last LBP VAS |

1.8 ± 1.5 |

2 ± 1.3 |

1.5 ± 1.2 |

0.582 |

| Pre Leg VAS |

7.8 ± 0.9 |

8.1 ± 1.4 |

8 ± 1.2 |

0.870 |

| Post Leg VAS |

1.9 ± 1 |

1.8 ± 0.7 |

1.6 ± 0.7 |

0.746 |

| Last Leg VAS |

0.9 ± 0.7 |

1.9 ± 2.1 |

1.8 ± 1.7 |

0.419 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).