Submitted:

22 August 2025

Posted:

25 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Triggering Receptor on Myeloid Cells 2 (TREM2) is a receptor found in microglia within the central nervous system (CNS) but also in several other cell types throughout the body. TREM2 has been highlighted as a “double-edged sword” due to its contribution to anti- or pro-inflammatory signaling responses in a spatial, temporal, and disease-specific fashion. Many of the functions of TREM2 in relation to neurological disease have been elucidated in a variety of CNS pathologies that include neurodegenerative, traumatic and vascular injuries and autoimmune diseases. Less is known about the function of TREM2 on motoneurons and sensory neurons whose cell bodies and axons expand between the CNS and peripheral nervous system (PNS) and are exposed to a variety of TREM2 expressing cells and mechanisms. In this review, we provide a brief overview of TREM2 and then highlight literature detailing the involvement of TREM2 along the spinal cord, peripheral nerves and muscles, sensory, motor and autonomic functions in health, aging, disease, and injury. We further discuss the current feasibility of TREM2 as a potential therapeutic target to ameliorate damage in the sensorimotor circuits of spinal cord.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells 2 (TREM2)

2.1. What and Where is TREM2?

2.2. TREM2 Ligands and Signaling Cascade

2.3. sTREM2

2.4. TREM2/DAP12 Mutations in Disease

2.5. Different Mouse Models May Contribute to Conflicting TREM2 Results

3. The Dorsal Root Ganglion

3.1. Anatomical Overview of the Dorsal Root Ganglion

3.2. TREM2 in the Dorsal Root Ganglion

4. TREM2 in the Spinal Cord

4.1. Anatomical Overview of the Spinal Cord

5. TREM2 in Microglia

5.1. Disease-Associated Microglia

5.2. Synaptic Plasticity

5.3. Neuronal Bioenergetic Support

6. TREM2 In the Dorsal Horn

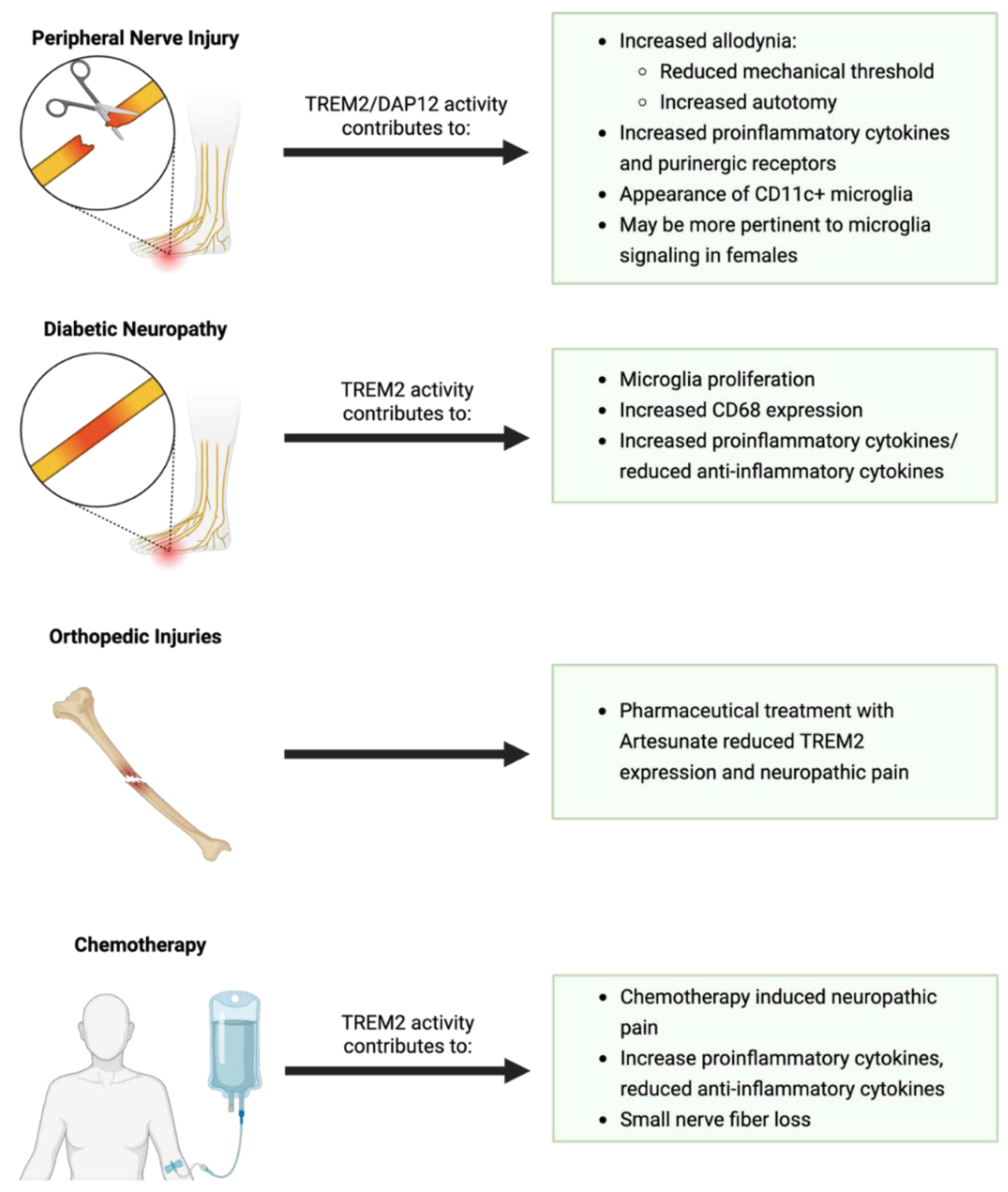

6.1. Neuropathic Pain

7. TREM2 in the Ventral Horn

7.1. Peripheral Nerve Injury

7.2. Aging

7.3. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

8. Spinal Cord Injury

9. TREM2 Along Peripheral Axons

9.1. Anatomical Overview of Peripheral Nerves

9.2. TREM2 in Schwann Cells

9.3. TREM2 in Peripheral Macrophages

10. TREM2 in Muscle

10.1. Anatomical Overview of Skeletal Muscle

10.2. Overview of Neuromuscular Junction Denervation/Reinnervation

10.3. TREM2 and the Neuromuscular Junction

11. TREM2 as a Therapeutic Target

12. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 5XFAD | 5 familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations |

| aa | Amino acid |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| ADAM10 | A Disintegrin and Metalloproteinase domain-containing protein 10 |

| ADAM17 | A Disintegrin and Metalloproteinase domain-containing protein 17 |

| ADI-R | Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised |

| AKT | Protein kinase B |

| ALS | Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis |

| ALSP | Adult-onset Leukoencephalopathy with axonal Spheroids and Pigmented glia |

| AMAN | Acute Motor Axonal Neuropathy |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| APOE | Apolipoprotein E |

| app1 | Antiphagocytic Protein 1 |

| arg1 | Arginase 1 |

| BBB | Blood Brain Barrier |

| C1q | Complement Component 1q |

| CCL21 | CC chemokine ligand 21/6Ckine |

| ccr2 | Chemokine (C-C motif) Receptor 2 |

| CKO | Conditional Knockout |

| Clec7a | C-type lectin domain family 7, member A. |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| CSF1 | Colony Stimulating Factor 1 |

| CSF1-R | Colony Stimulating Factor 1 Receptro |

| CTSD | Cathepsin D |

| CX3CL1 | Fractalkine |

| CX3CR1 | C-X3-C motif chemokine receptor 1/Fractalkine receptor |

| DAM | Disease Associate Microglia |

| DAP10/Hcst | DNAX activating protein of 10 KD |

| DAP12/tryobp | DNAX activating protein of 12 KD |

| DRG | Dorsal Root Ganglion |

| ePtdSer | Externalized Phosphatidylserine |

| ERK | Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase |

| GKO | Global Knockout |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| IL-1β | Interleukin -1 β |

| IL-34 | Interleukin-34 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| ITAM | Immunoreceptor Tyrosine-based Activation Motif. |

| KV2.1 | Potassium Voltage-Gated Channel, Shab-Related Subfamily, Member 1. |

| LAMP1 | Lysosome Associated Membrane Protein 1 |

| LPL | Lipoprotein Lipase |

| LPS | lysophosphatidylcholine |

| MAPK | Mitogen Actived Protein Kinaseitogen A |

| MEK | mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase |

| MND | Motor Neuron Disease |

| mTOR | mechanistic target of rapamycin/mammalian target of rapamycin |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain enhancer of activated B cells |

| NF2 | Merline |

| NMJ | Neuromuscular Junction |

| olfml3 | Olfactomedin-like 3 |

| P2RX4 | P2X purinoceptor 4 |

| P2RY12 | Purinergic Receptor P2Y, G Protein Coupled, 12 |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. |

| PLCγ | Phospholipase C |

| PNS | Peripheral Nervous Sysyem |

| PtdSer | Phosphatidylserine |

| PYK2 | Proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 |

| Raf | Rapidly Accelerated Fibrosarcoma |

| RAS | Reticular Activating System |

| RNA | ribonucleic acid |

| SHIP1 | Src homology 2 (SH2) domain-containing inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase 1. |

| SMA | Spinal Muscular Atrophy |

| SOD1 | Superoxide Dismutase 1. |

| spp1 | Secreted Phosphoprotein 1. |

| sTREM2 | Soluble Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myelioid Cells 2 |

| STZ | streptozotocin |

| SYK | Spleen tyrosine kinase |

| TAMS | Tumor Associated Macrophages |

| TDP-43 | TAR DNA-binding protein 43 |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor beta |

| Tmem119 | Transmembrane protein 119 |

| TNFα | Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha |

| TREM2 | Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells 2 |

| VAV2/3 | Vav family of guanine nucleotide exchange factors 2/3 |

| VEGFA | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A |

References

- Philips, T.; Robberecht, W. Neuroinflammation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: role of glial activation in motor neuron disease. The Lancet Neurology 2011, 10, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, F. Role of neuroinflammation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: cellular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Frontiers in immunology 2017, 8, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooten, K.G.; Beers, D.R.; Zhao, W.; Appel, S.H. Protective and toxic neuroinflammation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurotherapeutics 2015, 12, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, F.H.; Swarts, E.A.; Kigerl, K.A.; Mifflin, K.A.; Guan, Z.; Noble, B.T.; Wang, Y.; Witcher, K.G.; Godbout, J.P.; Popovich, P.G. Microglia promote maladaptive plasticity in autonomic circuitry after spinal cord injury in mice. Science Translational Medicine 2024, 16, eadi3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.K.; Sinkjær, T. Chapter 30 - Features and physiology of spinal stretch reflexes in people with chronic spinal cord injury. In Cellular, Molecular, Physiological, and Behavioral Aspects of Spinal Cord Injury, Rajendram, R., Preedy, V.R., Martin, C.R., Eds.; Academic Press: 2022; pp. 365-375.

- Li, C.; Xiong, W.; Wan, B.; Kong, G.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Fan, J. Role of peripheral immune cells in spinal cord injury. Cell Mol Life Sci 2022, 80, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiSabato, D.J.; Marion, C.M.; Mifflin, K.A.; Alfredo, A.N.; Rodgers, K.A.; Kigerl, K.A.; Popovich, P.G.; McTigue, D.M. System failure: Systemic inflammation following spinal cord injury. European journal of immunology 2024, 54, 2250274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, J.M.; Zhang, Y.; Kopp, M.A.; Brommer, B.; Popovich, P.G. The paradox of chronic neuroinflammation, systemic immune suppression, autoimmunity after traumatic chronic spinal cord injury. Experimental neurology 2014, 258, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottorf, T.S.; Rotterman, T.M.; McCallum, W.M.; Haley-Johnson, Z.A.; Alvarez, F.J. The Role of Microglia in Neuroinflammation of the Spinal Cord after Peripheral Nerve Injury. Cells 2022, 11, 2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konishi, H.; Kiyama, H. Microglial TREM2/DAP12 Signaling: A Double-Edged Sword in Neural Diseases. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 2018, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colonna, M. The biology of TREM receptors. Nature Reviews Immunology 2023, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colonna, M. TREMs in the immune system and beyond. Nature reviews. Immunology 2003, 3, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Fu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Xiong, M.; Meng, L.; Zhang, Z. TREM2 ectodomain and its soluble form in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanier, L.L. DAP10-and DAP12-associated receptors in innate immunity. Immunological reviews 2009, 227, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allcock, R.J.; Barrow, A.D.; Forbes, S.; Beck, S.; Trowsdale, J. The human TREM gene cluster at 6p21. 1 encodes both activating and inhibitory single IgV domain receptors and includes NKp44. European journal of immunology 2003, 33, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasamatsu, J.; Deng, M.; Azuma, M.; Funami, K.; Shime, H.; Oshiumi, H.; Matsumoto, M.; Kasahara, M.; Seya, T. Double-stranded RNA analog and type I interferon regulate expression of Trem paired receptors in murine myeloid cells. BMC immunology 2016, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stet, R.J.; Hermsen, T.; Westphal, A.H.; Jukes, J.; Engelsma, M.; Lidy Verburg-van Kemenade, B.; Dortmans, J.; Aveiro, J.; Savelkoul, H.F. Novel immunoglobulin-like transcripts in teleost fish encode polymorphic receptors with cytoplasmic ITAM or ITIM and a new structural Ig domain similar to the natural cytotoxicity receptor NKp44. Immunogenetics 2005, 57, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viertlboeck, B.C.; Schmitt, R.; Göbel, T.W. The chicken immunoregulatory receptor families SIRP, TREM, and CMRF35/CD300L. Immunogenetics 2006, 58, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.C.; Benitez, B.A.; Karch, C.M.; Cooper, B.; Skorupa, T.; Carrell, D.; Norton, J.B.; Hsu, S.; Harari, O.; Cai, Y. Coding variants in TREM2 increase risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Human molecular genetics 2014, 23, 5838–5846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, T.R.; von Saucken, V.E.; Landreth, G.E. TREM2 in neurodegenerative diseases. Molecular neurodegeneration 2017, 12, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Malhotra, S.; Torchia, J.A.; Kerr, W.G.; Coggeshall, K.M.; Humphrey, M.B. TREM2-and DAP12-dependent activation of PI3K requires DAP10 and is inhibited by SHIP1. Science signaling 2010, 3, ra38–ra38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunderlich, P.; Glebov, K.; Kemmerling, N.; Tien, N.T.; Neumann, H.; Walter, J. Sequential proteolytic processing of the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-2 (TREM2) protein by ectodomain shedding and γ-secretase-dependent intramembranous cleavage. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2013, 288, 33027–33036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Yu, J.X.; Zhang, W.X.; Lao, F.X.; Huang, H.C. Roles of TREM2 in the Pathological Mechanism and the Therapeutic Strategies of Alzheimer’s Disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 2024, 11, 1682–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Ji, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wen, X.; Shan, F. TREM2 deficiency impairs the energy metabolism of Schwann cells and exacerbates peripheral neurological deficits. Cell Death & Disease 2024, 15, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Feng, J.; Tang, L. Function of TREM1 and TREM2 in liver-related diseases. Cells 2020, 9, 2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-W.; Lee, I.-H.; Iimura, T.; Kong, S.W. Two macrophages, osteoclasts and microglia: from development to pleiotropy. Bone Research 2021, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, L. TREM2+ macrophages: a key role in disease development. Frontiers in Immunology, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulland, T.K.; Colonna, M. TREM2 — a key player in microglial biology and Alzheimer disease. Nature Reviews Neurology 2018, 14, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colonna, M.; Wang, Y. TREM2 variants: new keys to decipher Alzheimer disease pathogenesis. Nat Rev Neurosci 2016, 17, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, D.V.; Hanson, J.E.; Sheng, M. Microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. J Cell Biol 2018, 217, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painter, M.M.; Atagi, Y.; Liu, C.C.; Rademakers, R.; Xu, H.; Fryer, J.D.; Bu, G. TREM2 in CNS homeostasis and neurodegenerative disease. Mol Neurodegener 2015, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Kang, R.; Coyne, C.B.; Zeh, H.J.; Lotze, M.T. PAMPs and DAMPs: signal 0s that spur autophagy and immunity. Immunol Rev 2012, 249, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brantley-Sieders, D.M.; Zhuang, G.; Vaught, D.; Freeman, T.; Hwang, Y.; Hicks, D.; Chen, J. Host deficiency in Vav2/3 guanine nucleotide exchange factors impairs tumor growth, survival, and angiogenesis in vivo. Mol Cancer Res 2009, 7, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Götz, J. Pyk2 is a Novel Tau Tyrosine Kinase that is Regulated by the Tyrosine Kinase Fyn. J Alzheimers Dis 2018, 64, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martelli, M.P.; Lin, H.; Zhang, W.; Samelson, L.E.; Bierer, B.E. Signaling via LAT (linker for T-cell activation) and Syk/ZAP70 is required for ERK activation and NFAT transcriptional activation following CD2 stimulation. Blood 2000, 96, 2181–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.S.; Yu, J.T.; Tan, L. Bridging integrator 1 (BIN1): form, function, and Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Mol Med 2013, 19, 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griciuc, A.; Patel, S.; Federico, A.N.; Choi, S.H.; Innes, B.J.; Oram, M.K.; Cereghetti, G.; McGinty, D.; Anselmo, A.; Sadreyev, R.I.; et al. TREM2 Acts Downstream of CD33 in Modulating Microglial Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuron 2019, 103, 820–835.e827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Li, X.; Dai, K.; Duan, S.; Rong, Z.; Chen, Y.; Lü, L.; Liu, Z.; Huang, X.; Xu, H. Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-2 (TREM2) interacts with colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) but is not necessary for CSF1/CSF1R-mediated microglial survival. Frontiers in immunology 2021, 12, 633796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xiang, X.; Li, Y.; Bu, G.; Chen, X.-F. TREM2 and sTREM2 in Alzheimer’s disease: from mechanisms to therapies. Molecular Neurodegeneration 2025, 20, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mócsai, A.; Ruland, J.; Tybulewicz, V.L. The SYK tyrosine kinase: a crucial player in diverse biological functions. Nature Reviews Immunology 2010, 10, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cella, M.; Mallinson, K.; Ulrich, J.D.; Young, K.L.; Robinette, M.L.; Gilfillan, S.; Krishnan, G.M.; Sudhakar, S.; Zinselmeyer, B.H.; et al. TREM2 lipid sensing sustains the microglial response in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Cell 2015, 160, 1061–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirotani, K.; Hori, Y.; Yoshizaki, R.; Higuchi, E.; Colonna, M.; Saito, T.; Hashimoto, S.; Saito, T.; Saido, T.C.; Iwata, N. Aminophospholipids are signal-transducing TREM2 ligands on apoptotic cells. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 7508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kober, D.L.; Stuchell-Brereton, M.D.; Kluender, C.E.; Dean, H.B.; Strickland, M.R.; Steinberg, D.F.; Nelson, S.S.; Baban, B.; Holtzman, D.M.; Frieden, C. Functional insights from biophysical study of TREM2 interactions with apoE and Aβ1-42. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2021, 17, 475–488. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon, J.P.; O’Driscoll, M.; Litman, G.W. Specific lipid recognition is a general feature of CD300 and TREM molecules. Immunogenetics 2012, 64, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Hooli, B.; Mullin, K.; Jin, S.C.; Cella, M.; Ulland, T.K.; Wang, Y.; Tanzi, R.E.; Colonna, M. Alzheimer’s disease-associated TREM2 variants exhibit either decreased or increased ligand-dependent activation. Alzheimers Dement 2017, 13, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atagi, Y.; Liu, C.C.; Painter, M.M.; Chen, X.F.; Verbeeck, C.; Zheng, H.; Li, X.; Rademakers, R.; Kang, S.S.; Xu, H.; et al. Apolipoprotein E Is a Ligand for Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells 2 (TREM2). J Biol Chem 2015, 290, 26043–26050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, C.C.; DeVaux, L.B.; Farzan, M. The Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells 2 Binds Apolipoprotein E. J Biol Chem 2015, 290, 26033–26042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawabori, M.; Kacimi, R.; Kauppinen, T.; Calosing, C.; Kim, J.Y.; Hsieh, C.L.; Nakamura, M.C.; Yenari, M.A. Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) deficiency attenuates phagocytic activities of microglia and exacerbates ischemic damage in experimental stroke. Journal of Neuroscience 2015, 35, 3384–3396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daws, M.R.; Sullam, P.M.; Niemi, E.C.; Chen, T.T.; Tchao, N.K.; Seaman, W.E. Pattern recognition by TREM-2: binding of anionic ligands. J Immunol 2003, 171, 594–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iizasa, E.i.; Chuma, Y.; Uematsu, T.; Kubota, M.; Kawaguchi, H.; Umemura, M.; Toyonaga, K.; Kiyohara, H.; Yano, I.; Colonna, M.; et al. TREM2 is a receptor for non-glycosylated mycolic acids of mycobacteria that limits anti-mycobacterial macrophage activation. Nature Communications 2021, 12, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wu, X.; Li, X.; Jiang, L.-L.; Gui, X.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, B.; Piña-Crespo, J.C.; Zhang, M. TREM2 is a receptor for β-amyloid that mediates microglial function. Neuron 2018, 97, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Liu, Y.U.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, L.; Bosco, D.B.; Pang, Y.-P.; Zhong, J.; Sheth, U.; Martens, Y.A.; Zhao, N. TREM2 interacts with TDP-43 and mediates microglial neuroprotection against TDP-43-related neurodegeneration. Nature neuroscience 2022, 25, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills III, W.A.; Eyo, U.B. TREMble before TREM2: the mighty microglial receptor conferring neuroprotective properties in TDP-43 mediated neurodegeneration. Neuroscience Bulletin 2023, 39, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, L.H.; Willette-Brown, J.; Taylor, L.S.; McVicar, D.W. Regulation of Ly49D/DAP12 Signal Transduction by Src-Family Kinases and CD4512. The Journal of Immunology 2006, 176, 6615–6623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, G.; Koegl, M.; Mazurenko, N.; Courtneidge, S.A. Sequence Requirements for Binding of Src Family Tyrosine Kinases to Activated Growth Factor Receptors (∗). Journal of Biological Chemistry 1995, 270, 9840–9848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Elwood, F.; Britschgi, M.; Villeda, S.; Zhang, H.; Ding, Z.; Zhu, L.; Alabsi, H.; Getachew, R.; Narasimhan, R.; et al. Colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) signaling in injured neurons facilitates protection and survival. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2013, 210, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J.A. CSF-1 signal transduction. Journal of Leukocyte Biology 1997, 62, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pixley, F.J.; Stanley, E.R. CSF-1 regulation of the wandering macrophage: complexity in action. Trends Cell Biology 2004, 14, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Z.; Kuhn, J.A.; Wang, X.; Colquitt, B.; Solorzano, C.; Vaman, S.; Guan, A.K.; Evans-Reinsch, Z.; Braz, J.; Devor, M. Injured sensory neuron–derived CSF1 induces microglial proliferation and DAP12-dependent pain. Nature Neuroscience 2016, 19, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, K.; Turnbull, I.R.; Poliani, P.L.; Vermi, W.; Cerutti, E.; Aoshi, T.; Tassi, I.; Takai, T.; Stanley, S.L.; Miller, M. Macrophage colony-stimulating factor induces the proliferation and survival of macrophages via a pathway involving DAP12 and β-catenin. Nature immunology 2009, 10, 734–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornton, P.; Sevalle, J.; Deery, M.J.; Fraser, G.; Zhou, Y.; Ståhl, S.; Franssen, E.H.; Dodd, R.B.; Qamar, S.; Gomez Perez-Nievas, B.; et al. TREM2 shedding by cleavage at the H157‐S158 bond is accelerated for the Alzheimer’s disease‐associated H157Y variant. EMBO Molecular Medicine 2017, 9, 1366–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlepckow, K.; Kleinberger, G.; Fukumori, A.; Feederle, R.; Lichtenthaler, S.F.; Steiner, H.; Haass, C. An Alzheimer-associated TREM2 variant occurs at the ADAM cleavage site and affects shedding and phagocytic function. EMBO molecular medicine 2017, 9, 1356–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glebov, K.; Wunderlich, P.; Karaca, I.; Walter, J. Functional involvement of γ-secretase in signaling of the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-2 (TREM2). Journal of Neuroinflammation 2016, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuerbach, D.; Schindler, P.; Barske, C.; Joller, S.; Beng-Louka, E.; Worringer, K.A.; Kommineni, S.; Kaykas, A.; Ho, D.J.; Ye, C.; et al. ADAM17 is the main sheddase for the generation of human triggering receptor expressed in myeloid cells (hTREM2) ectodomain and cleaves TREM2 after Histidine 157. Neuroscience Letters 2017, 660, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipello, F.; Goldsbury, C.; You, S.F.; Locca, A.; Karch, C.M.; Piccio, L. Soluble TREM2: Innocent bystander or active player in neurological diseases? Neurobiology of Disease 2022, 165, 105630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutinho, M.; Coronel, I.; Tsai, A.P.; Di Prisco, G.V.; Pennington, T.; Atwood, B.K.; Puntambekar, S.S.; Smith, D.C.; Martinez, P.; Han, S.; et al. TREM2 splice isoforms generate soluble TREM2 species that disrupt long-term potentiation. Genome Medicine 2023, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutinho, M.; Landreth, G.E. TREM2 splicing emerges as crucial aspect to understand TREM2 biology. Journal of Leukocyte Biology 2021, 110, 827–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccio, L.; Buonsanti, C.; Cella, M.; Tassi, I.; Schmidt, R.E.; Fenoglio, C.; Rinker, J., II; Naismith, R.T.; Panina-Bordignon, P.; Passini, N.; et al. Identification of soluble TREM-2 in the cerebrospinal fluid and its association with multiple sclerosis and CNS inflammation. Brain : a journal of neurology 2008, 131, 3081–3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jericó, I.; Vicuña-Urriza, J.; Blanco-Luquin, I.; Macias, M.; Martinez-Merino, L.; Roldán, M.; Rojas-Garcia, R.; Pagola-Lorz, I.; Carbayo, A.; De Luna, N.; et al. Profiling TREM2 expression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2023, 109, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Chen, X.F.; Wang, T.; Wang, Z.; Liao, C.; Wang, Z.; Huang, R.; Wang, D.; Li, X.; Wu, L.; et al. Soluble TREM2 induces inflammatory responses and enhances microglial survival. J Exp Med 2017, 214, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.M.; Joshita, S.; Zhou, Y.; Ulland, T.K.; Gilfillan, S.; Colonna, M. Humanized TREM2 mice reveal microglia-intrinsic and -extrinsic effects of R47H polymorphism. J Exp Med 2018, 215, 745–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Byers, D.E.; Jin, X.; Agapov, E.; Alexander-Brett, J.; Patel, A.C.; Cella, M.; Gilfilan, S.; Colonna, M.; Kober, D.L.; et al. TREM-2 promotes macrophage survival and lung disease after respiratory viral infection. J Exp Med 2015, 212, 681–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-H.; Lee, E.-H.; Kim, H.-J.; Jo, S.; Lee, S.; Seo, S.W.; Park, H.-H.; Koh, S.-H.; Lee, J.-H. The relationship of soluble TREM2 to other biomarkers of sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 13050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabizadeh, F.; Seyedmirzaei, H.; Karami, S. Neuroimaging biomarkers and CSF sTREM2 levels in Alzheimer’s disease: a longitudinal study. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 15318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhan, Y.; Zhu, W.; Yang, Q.; Pei, J. Association of soluble TREM2 with Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Yang, J.; Wang, W.; Liu, X.; Fu, Y.; Fan, D. sTREM2 cerebrospinal fluid levels are a potential biomarker in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and associate with UMN burden. Frontiers in Neurology, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper-Knock, J.; Green, C.; Altschuler, G.; Wei, W.; Bury, J.J.; Heath, P.R.; Wyles, M.; Gelsthorpe, C.; Highley, J.R.; Lorente-Pons, A. A data-driven approach links microglia to pathology and prognosis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta neuropathologica communications 2017, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Di, J.; Clausen, B.H.; Wang, N.; Zhu, X.; Zhao, T.; Chang, Y.; Pang, M.; Yang, Y.; He, R. Distinct myeloid population phenotypes dependent on TREM2 expression levels shape the pathology of traumatic versus demyelinating CNS disorders. Cell Reports 2023, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paloneva, J.; Manninen, T.; Christman, G.; Hovanes, K.; Mandelin, J.; Adolfsson, R.; Bianchin, M.; Bird, T.; Miranda, R.; Salmaggi, A.; et al. Mutations in Two Genes Encoding Different Subunits of a Receptor Signaling Complex Result in an Identical Disease Phenotype. The American Journal of Human Genetics 2002, 71, 656–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paloneva, J.; Mandelin, J.; Kiialainen, A.; Böhling, T.; Prudlo, J.; Hakola, P.; Haltia, M.; Konttinen, Y.T.; Peltonen, L. DAP12/TREM2 deficiency results in impaired osteoclast differentiation and osteoporotic features. The Journal of experimental medicine 2003, 198, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Tada, M.; Cai, Z.; Andhey, P.S.; Swain, A.; Miller, K.R.; Gilfillan, S.; Artyomov, M.N.; Takao, M.; Kakita, A.; et al. Human early-onset dementia caused by DAP12 deficiency reveals a unique signature of dysregulated microglia. Nature Immunology 2023, 24, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, R.; Wojtas, A.; Bras, J.; Carrasquillo, M.; Rogaeva, E.; Majounie, E.; Cruchaga, C.; Sassi, C.; Kauwe, J.S.; Younkin, S. TREM2 variants in Alzheimer’s disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2013, 368, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, T.; Stefansson, H.; Steinberg, S.; Jonsdottir, I.; Jonsson, P.V.; Snaedal, J.; Bjornsson, S.; Huttenlocher, J.; Levey, A.I.; Lah, J.J. Variant of TREM2 associated with the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2013, 368, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Liu, Y.; Hwang, S.; Archuleta, K.; Huang, H.; Campos, A.; Murad, R.; Piña-Crespo, J.; Xu, H.; Huang, T.Y. Trem2 deletion enhances tau dispersion and pathology through microglia exosomes. Molecular Neurodegeneration 2022, 17, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, A.S.; Butler, C.A.; Allendorf, D.H.; Piers, T.M.; Mallach, A.; Roewe, J.; Reinhardt, P.; Cinti, A.; Redaelli, L.; Boudesco, C.; et al. Alzheimer’s disease-associated R47H TREM2 increases, but wild-type TREM2 decreases, microglial phagocytosis of synaptosomes and neuronal loss. Glia 2023, 71, 974–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.L.; Tan, C.C.; Hou, X.H.; Cao, X.P.; Tan, L.; Yu, J.T. TREM2 Variants and Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Alzheimers Dis 2019, 68, 1171–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasemann, S.; Madore, C.; Cialic, R.; Baufeld, C.; Calcagno, N.; El Fatimy, R.; Beckers, L.; O’Loughlin, E.; Xu, Y.; Fanek, Z.; et al. The TREM2-APOE Pathway Drives the Transcriptional Phenotype of Dysfunctional Microglia in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Immunity 2017, 47, 566–581.e569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratuze, M.; Leyns, C.E.G.; Holtzman, D.M. New insights into the role of TREM2 in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener 2018, 13, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayaprolu, S.; Mullen, B.; Baker, M.; Lynch, T.; Finger, E.; Seeley, W.W.; Hatanpaa, K.J.; Lomen-Hoerth, C.; Kertesz, A.; Bigio, E.H. TREM2 in neurodegeneration: evidence for association of the p. R47H variant with frontotemporal dementia and Parkinson’s disease. Molecular neurodegeneration 2013, 8, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cady, J.; Koval, E.D.; Benitez, B.A.; Zaidman, C.; Jockel-Balsarotti, J.; Allred, P.; Baloh, R.H.; Ravits, J.; Simpson, E.; Appel, S.H. TREM2 variant p. R47H as a risk factor for sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. JAMA neurology 2014, 71, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peplonska, B.; Berdynski, M.; Mandecka, M.; Barczak, A.; Kuzma-Kozakiewicz, M.; Barcikowska, M.; Zekanowski, C. TREM2 variants in neurodegenerative disorders in the Polish population. Homozygosity and compound heterozygosity in FTD patients. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Degeneration 2018, 19, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.S.; Kurti, A.; Baker, K.E.; Liu, C.-C.; Colonna, M.; Ulrich, J.D.; Holtzman, D.M.; Bu, G.; Fryer, J.D. Behavioral and transcriptomic analysis of Trem2-null mice: not all knockout mice are created equal. Human molecular genetics 2018, 27, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipello, F.; Morini, R.; Corradini, I.; Zerbi, V.; Canzi, A.; Michalski, B.; Erreni, M.; Markicevic, M.; Starvaggi-Cucuzza, C.; Otero, K. The microglial innate immune receptor TREM2 is required for synapse elimination and normal brain connectivity. Immunity 2018, 48, 979–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliatti, E.; Desiato, G.; Mancinelli, S.; Bizzotto, M.; Gagliani, M.C.; Faggiani, E.; Hernández-Soto, R.; Cugurra, A.; Poliseno, P.; Miotto, M.; et al. Trem2 expression in microglia is required to maintain normal neuronal bioenergetics during development. Immunity 2024, 57, 86–105.e109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, C.D.; Sautkulis, L.N.; Danielson, P.E.; Cooper, J.; Hasel, K.W.; Hilbush, B.S.; Sutcliffe, J.G.; Carson, M.J. Heterogeneous expression of the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-2 on adult murine microglia. J Neurochem 2002, 83, 1309–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forabosco, P.; Ramasamy, A.; Trabzuni, D.; Walker, R.; Smith, C.; Bras, J.; Levine, A.P.; Hardy, J.; Pocock, J.M.; Guerreiro, R.; et al. Insights into TREM2 biology by network analysis of human brain gene expression data. Neurobiology of Aging 2013, 34, 2699–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyns, C.E.; Ulrich, J.D.; Finn, M.B.; Stewart, F.R.; Koscal, L.J.; Remolina Serrano, J.; Robinson, G.O.; Anderson, E.; Colonna, M.; Holtzman, D.M. TREM2 deficiency attenuates neuroinflammation and protects against neurodegeneration in a mouse model of tauopathy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114, 11524–11529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyns, C.E.; Gratuze, M.; Narasimhan, S.; Jain, N.; Koscal, L.J.; Jiang, H.; Manis, M.; Colonna, M.; Lee, V.M.; Ulrich, J.D. TREM2 function impedes tau seeding in neuritic plaques. Nature neuroscience 2019, 22, 1217–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarnes, W.C.; Rosen, B.; West, A.P.; Koutsourakis, M.; Bushell, W.; Iyer, V.; Mujica, A.O.; Thomas, M.; Harrow, J.; Cox, T.; et al. A conditional knockout resource for the genome-wide study of mouse gene function. Nature 2011, 474, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, B.C.; Snider, H.C.; Turner, A.K.; Zajac, D.J.; Simpson, J.F.; Estus, S.; Combs, C. An Alternatively Spliced TREM2 Isoform Lacking the Ligand Binding Domain is Expressed in Human Brain. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2022, 87, 1647–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brierley, J.B. The penetration of particulate matter from the cerebrospinal fluid into the spinal ganglia, peripheral nerves, and perivascular spaces of the central nervous system. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1950, 13, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devor, M. Unexplained peculiarities of the dorsal root ganglion. PAIN 1999, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagashima, K.; Oota, K. A HISTOPATHOLOGICAL STUDY OF THE HUMAN SPINAL GANGLIA. NORMAL VARIATIONS IN AGING. Acta Patholigica Japonica 1974, 24, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandrup, T. Unbiased estimates of number and size of rat dorsal root ganglion cells in studies of structure and cell survival. Journal of neurocytology 2004, 33, 173–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.A.; McKay Hart, A.; Terenghi, G.; Wiberg, M. Sensory neurons of the human brachial plexus: a quantitative study employing optical fractionation and in vivo volumetric magnetic resonance imaging. Neurosurgery 2012, 70, 1183–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberberger, R.V.; Kuramatilake, J.; Barry, C.M.; Matusica, D. Ultrastructure of dorsal root ganglia. Cell Tissue Res 2023, 393, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraham, O.; Feng, R.; Ewan, E.E.; Rustenhoven, J.; Zhao, G.; Cavalli, V. Profiling sensory neuron microenvironment after peripheral and central axon injury reveals key pathways for neural repair. eLife 2021, 10, e68457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feringa, E.R.; Lee, G.W.; Vahlsing, H.L.; Gilbertie, W.J. Cell death in the adult rat dorsal root ganglion after hind limb amputation, spinal cord transection, or both operations. Exp Neurol 1985, 87, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S. Single-cell transcriptome analyses of dorsal root ganglia in aged hyperlipidemic mice. lmu, 2023.

- Li, X.; Zhuang, Z.; Hao, Y.; Lin, S.; Gu, J.; Chang, S.; Lan, L.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, D. Paeonol Relieves Chronic Neuropathic Pain by Reducing Communication Between Schwann Cells and Macrophages in the Dorsal Root Ganglia After Injury. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Cai, R.; Li, Q.; Wang, H.; Lu, L. Neuroinflammation signatures in dorsal root ganglia following chronic constriction injury. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Liu, H.; Hamel, K.A.; Morvan, M.G.; Yu, S.; Leff, J.; Guan, Z.; Braz, J.M.; Basbaum, A.I. Dorsal root ganglion macrophages contribute to both the initiation and persistence of neuropathic pain. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Muraleedharan Saraswathy, V.; Mokalled, M.H.; Cavalli, V. Self-renewing macrophages in dorsal root ganglia contribute to promote nerve regeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2023, 120, e2215906120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.G. Organization in the spinal cord: the anatomy and physiology of identified neurones; Springer Science & Business Media: 2012.

- Fowler, C.J.; Griffiths, D.; De Groat, W.C. The neural control of micturition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2008, 9, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuru, M. Nervous control of micturition. Physiological Reviews 1965, 45, 425–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uher, E.-M.; Swash, M. Sacral reflexes: physiology and clinical application. Diseases of the colon & rectum 1998, 41, 1165–1177. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, E.; Morales, H. Spinal Cord Anatomy and Clinical Syndromes. Seminars in Ultrasound, CT and MRI 2016, 37, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, G.D.; Darby, S.A. Clinical anatomy of the spine, spinal cord, and ANS. 2013.

- Green, T.R.; Rowe, R.K. Quantifying microglial morphology: an insight into function. Clinical and experimental immunology 2024, 216, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Itriago, A.; Radford, R.A.; Aramideh, J.A.; Maurel, C.; Scherer, N.M.; Don, E.K.; Lee, A.; Chung, R.S.; Graeber, M.B.; Morsch, M. Microglia morphophysiological diversity and its implications for the CNS. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 997786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edler, M.K.; Mhatre-Winters, I.; Richardson, J.R. Microglia in Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Comparative Species Review. Cells 2021, 10, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pottorf, T.S.; Lane, E.L.; Haley-Johnson, Z.; Amores-Sanchez, V.; Ukmar, D.N.; Correa-Torres, P.M.; Alvarez, F.J. Dual Role of Microglial TREM2 in Neuronal Degeneration and Regeneration After Axotomy. bioRxiv, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, R.; Zachariadis, V.; Sankavaram, S.R.; Han, J.; Harris, R.A.; Brundin, L.; Enge, M.; Svensson, M. Spinal Cord Injury Induces Permanent Reprogramming of Microglia into a Disease-Associated State Which Contributes to Functional Recovery. J Neurosci 2021, 41, 8441–8459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keren-Shaul, H.; Spinrad, A.; Weiner, A.; Matcovitch-Natan, O.; Dvir-Szternfeld, R.; Ulland, T.K.; David, E.; Baruch, K.; Lara-Astaiso, D.; Toth, B. A unique microglia type associated with restricting development of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell 2017, 169, 1276–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samant, R.R.; Standaert, D.G.; Harms, A.S. The emerging role of disease-associated microglia in Parkinson’s disease. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Zhao, S.; Bosco, D.B.; Nguyen, A.; Wu, L.J. Microglial TREM2 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Developmental neurobiology 2022, 82, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Microglia heterogeneity in Alzheimer’s disease: insights from single-cell technologies. Frontiers in Synaptic Neuroscience 2021, 13, 773590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deczkowska, A.; Keren-Shaul, H.; Weiner, A.; Colonna, M.; Schwartz, M.; Amit, I. Disease-associated microglia: a universal immune sensor of neurodegeneration. Cell 2018, 173, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Song, W.M.; Andhey, P.S.; Swain, A.; Levy, T.; Miller, K.R.; Poliani, P.L.; Cominelli, M.; Grover, S.; Gilfillan, S.; et al. Human and mouse single-nucleus transcriptomics reveal TREM2-dependent and TREM2-independent cellular responses in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature Medicine 2020, 26, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J.-C.; Ibrahim-Verbaas, C.A.; Harold, D.; Naj, A.C.; Sims, R.; Bellenguez, C.; Jun, G.; DeStefano, A.L.; Bis, J.C.; Beecham, G.W. Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nature genetics 2013, 45, 1452–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.M.; Colonna, M. The identity and function of microglia in neurodegeneration. Nature immunology 2018, 19, 1048–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuade, A.; Kang, Y.J.; Hasselmann, J.; Jairaman, A.; Sotelo, A.; Coburn, M.; Shabestari, S.K.; Chadarevian, J.P.; Fote, G.; Tu, C.H.; et al. Gene expression and functional deficits underlie TREM2-knockout microglia responses in human models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 5370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennerfelt, H.; Frost, E.L.; Shapiro, D.A.; Holliday, C.; Zengeler, K.E.; Voithofer, G.; Bolte, A.C.; Lammert, C.R.; Kulas, J.A.; Ulland, T.K. SYK coordinates neuroprotective microglial responses in neurodegenerative disease. Cell 2022, 185, 4135–4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteoli, M. The role of microglial TREM2 in development: A path toward neurodegeneration? Glia 2024, 72, 1544–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, T.R.; von Saucken, V.E.; Muñoz, B.; Codocedo, J.F.; Atwood, B.K.; Lamb, B.T.; Landreth, G.E. TREM2 is required for microglial instruction of astrocytic synaptic engulfment in neurodevelopment. Glia 2019, 67, 1873–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchiarelli, H.A.; Bisht, K.; Sharma, K.; Weiser Novak, S.; Traetta, M.E.; Garcia-Segura, M.E.; St-Pierre, M.-K.; Savage, J.C.; Willis, C.; Picard, K. Dark Microglia Are Abundant in Normal Postnatal Development, where they Remodel Synapses via Phagocytosis and Trogocytosis, and Are Dependent on TREM2. bioRxiv, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- St-Pierre, M.-K.; Šimončičová, E.; Bögi, E.; Tremblay, M.-È. Shedding light on the dark side of the microglia. ASN neuro 2020, 12, 1759091420925335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, A.H.; Barres, B.A.; Stevens, B. The complement system: an unexpected role in synaptic pruning during development and disease. Annual Review of Neuroscience 2012, 35, 369–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, D.P.; Lehrman, E.K.; Kautzman, A.G.; Koyama, R.; Mardinly, A.R.; Yamasaki, R.; Ransohoff, R.M.; Greenberg, M.E.; Barres, B.A.; Stevens, B. Microglia sculpt postnatal neural circuits in an activity and complement-dependent manner. Neuron 2012, 74, 691–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, A.S.; Eyo, U.B. Microglia and Astrocytes in Postnatal Neural Circuit Formation. Glia 2025, 73, 232–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott-Hewitt, N.; Perrucci, F.; Morini, R.; Erreni, M.; Mahoney, M.; Witkowska, A.; Carey, A.; Faggiani, E.; Schuetz, L.T.; Mason, S.; et al. Local externalization of phosphatidylserine mediates developmental synaptic pruning by microglia. Embo j 2020, 39, e105380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Lue, L.-F.; Yang, L.-B.; Roher, A.; Kuo, Y.-M.; Strohmeyer, R.; Goux, W.J.; Lee, V.; Johnson, G.V.; Webster, S.D. Complement activation by neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience letters 2001, 305, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Burdick, D.; Glabe, C.G.; Cotman, C.W.; Tenner, A.J. beta-Amyloid activates complement by binding to a specific region of the collagen-like domain of the C1q A chain. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950) 1994, 152, 5050–5059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.; Cooper, N.R.; Webster, S.; Schultz, J.; McGeer, P.L.; Styren, S.D.; Civin, W.H.; Brachova, L.; Bradt, B.; Ward, P. Complement activation by beta-amyloid in Alzheimer disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1992, 89, 10016–10020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Sheng, X.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Zhuo, R.; Wang, K.; Zhang, L.; Hu, D.-D.; Hong, Y.; Chen, L. TREM2 receptor protects against complement-mediated synaptic loss by binding to complement C1q during neurodegeneration. Immunity 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda-Carrasco, J.; Sokolova, D.; Lee, S.E.; Childs, T.; Jurčáková, N.; Crowley, G.; De Schepper, S.; Ge, J.Z.; Lachica, J.I.; Toomey, C.E.; et al. Microglia-synapse engulfment via PtdSer-TREM2 ameliorates neuronal hyperactivity in Alzheimer’s disease models. Embo j 2023, 42, e113246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fracassi, A.; Marcatti, M.; Tumurbaatar, B.; Woltjer, R.; Moreno, S.; Taglialatela, G. TREM2-induced activation of microglia contributes to synaptic integrity in cognitively intact aged individuals with Alzheimer’s neuropathology. Brain Pathol 2023, 33, e13108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejanovic, B.; Wu, T.; Tsai, M.C.; Graykowski, D.; Gandham, V.D.; Rose, C.M.; Bakalarski, C.E.; Ngu, H.; Wang, Y.; Pandey, S.; et al. Complement C1q-dependent excitatory and inhibitory synapse elimination by astrocytes and microglia in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Nat Aging 2022, 2, 837–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Mao, W.; Voskobiynyk, Y.; Necula, D.; Lew, I.; Petersen, C.; Zahn, A.; Yu, G.Q.; Yu, X.; Smith, N.; et al. Alzheimer risk-increasing TREM2 variant causes aberrant cortical synapse density and promotes network hyperexcitability in mouse models. Neurobiol Dis 2023, 186, 106263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freria, C.M.; Brennan, F.H.; Sweet, D.R.; Guan, Z.; Hall, J.C.; Kigerl, K.A.; Nemeth, D.P.; Liu, X.; Lacroix, S.; Quan, N. Serial Systemic Injections of Endotoxin (LPS) Elicit Neuroprotective Spinal Cord Microglia through IL-1-Dependent Cross Talk with Endothelial Cells. Journal of Neuroscience 2020, 40, 9103–9120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cserép, C.; Pósfai, B.; Lénárt, N.; Fekete, R.; László, Z.I.; Lele, Z.; Orsolits, B.; Molnár, G.; Heindl, S.; Schwarcz, A.D.; et al. Microglia monitor and protect neuronal function through specialized somatic purinergic junctions. Science 2020, 367, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; Tsuda, M. Microglia in neuropathic pain: cellular and molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2018, 19, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozaki-Saitoh, H.; Takeda, H.; Inoue, K. The Role of Microglial Purinergic Receptors in Pain Signaling. Molecules 2022, 27, 1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozaki-Saitoh, H.; Tsuda, M.; Miyata, H.; Ueda, K.; Kohsaka, S.; Inoue, K. P2Y12 receptors in spinal microglia are required for neuropathic pain after peripheral nerve injury. Journal of Neuroscience 2008, 28, 4949–4956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, M.; Masuda, T.; Kitano, J.; Shimoyama, H.; Tozaki-Saitoh, H.; Inoue, K. IFN-γ receptor signaling mediates spinal microglia activation driving neuropathic pain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2009, 106, 8032–8037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, T.; Ozono, Y.; Mikuriya, S.; Kohro, Y.; Tozaki-Saitoh, H.; Iwatsuki, K.; Uneyama, H.; Ichikawa, R.; Salter, M.W.; Tsuda, M. Dorsal horn neurons release extracellular ATP in a VNUT-dependent manner that underlies neuropathic pain. Nature Communications 2016, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boakye, P.A.; Tang, S.-J.; Smith, P.A. Mediators of Neuropathic Pain; Focus on Spinal Microglia, CSF-1, BDNF, CCL21, TNF-α, Wnt Ligands, and Interleukin 1β. Frontiers in Pain Research 2021, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sideris-Lampretsas, G.; Malcangio, M. Microglial heterogeneity in chronic pain. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2021, 96, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Basbaum, A.; Guan, Z. Contribution of colony-stimulating factor 1 to neuropathic pain. Pain Reports 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohno, K.; Tsuda, M. Role of microglia and P2 × 4 receptors in chronic pain. Pain Reports 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, C.R.; Andriessen, A.S.; Chen, G.; Wang, K.; Jiang, C.; Maixner, W.; Ji, R.-R. Central nervous system targets: glial cell mechanisms in chronic pain. Neurotherapeutics 2020, 17, 846–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salter, M.W.; Beggs, S. Sublime microglia: expanding roles for the guardians of the CNS. Cell 2014, 158, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrini, F.; De Koninck, Y. Microglia control neuronal network excitability via BDNF signalling. Neural Plasticity 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcangio, M.; Sideris-Lampretsas, G. How microglia contribute to the induction and maintenance of neuropathic pain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2025, 26, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Tian, G.; He, K.; Su, Y.; Wang, Z.; Huang, L.; Yao, Y.; Li, X.; Lin, Y. The role of microglia in neuropathic pain: A systematic review of animal experiments. Brain Research Bulletin 2025, 111410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Konishi, H.; Sayo, A.; Takai, T.; Kiyama, H. TREM2/DAP12 signal elicits proinflammatory response in microglia and exacerbates neuropathic pain. Journal of Neuroscience 2016, 36, 11138–11150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Huang, Y.; Liu, W.; Cai, G.; Huang, S.; Zeng, Y.; Ren, S.; Zhan, H.; Wu, W. Resveratrol mediates mechanical allodynia through modulating inflammatory response via the TREM2-autophagy axis in SNI rat model. J Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefpour, N.; Locke, S.; Deamond, H.; Wang, C.; Marques, L.; St-Louis, M.; Ouellette, J.; Khoutorsky, A.; De Koninck, Y.; Ribeiro-da-Silva, A. Time-dependent and selective microglia-mediated removal of spinal synapses in neuropathic pain. Cell Reports 2023, 42, 112010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohno, K.; Shirasaka, R.; Yoshihara, K.; Mikuriya, S.; Tanaka, K.; Takanami, K.; Inoue, K.; Sakamoto, H.; Ohkawa, Y.; Masuda, T.; et al. A spinal microglia population involved in remitting and relapsing neuropathic pain. Science 2022, 376, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, M.; Masuda, T.; Kohno, K. Microglial diversity in neuropathic pain. Trends in Neurosciences 2023, 46, 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamphuis, W.; Kooijman, L.; Schetters, S.; Orre, M.; Hol, E.M. Transcriptional profiling of CD11c-positive microglia accumulating around amyloid plaques in a mouse model for Alzheimer’s disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-molecular basis of Disease 2016, 1862, 1847–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, N.T.; Yin, Z.; Guneykaya, D.; Gauthier, C.D.; Hayes, J.P.; D’Hary, A.; Butovsky, O.; Moalem-Taylor, G. Sex-specific transcriptome of spinal microglia in neuropathic pain due to peripheral nerve injury. Glia 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Y.; Tang, S.-q.; He, W.-y.; He, J.; Wang, Y.-h.; Wang, H. Contribution of Trem2 signaling to the development of painful diabetic neuropathy by mediating microglial polarization in mice. 2021.

- Guruprasad, B.; Chaudhary, P.; Choedon, T.; Kumar, V.L. Artesunate ameliorates functional limitations in Freund’s complete adjuvant-induced monoarthritis in rat by maintaining oxidative homeostasis and inhibiting COX-2 expression. Inflammation 2015, 38, 1028–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, T.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Wang, G.; Wang, C.; Li, Y. Artesunate reduces remifentanil-induced hyperalgesia and peroxiredoxin-3 hyperacetylation via modulating spinal metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 in rats. Neuroscience 2022, 487, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, N.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Gao, T.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, G.; Yu, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, Y. Artesunate therapy alleviates fracture-associated chronic pain after orthopedic surgery by suppressing CCL21-dependent TREM2/DAP12 inflammatory signaling in mice. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2022, 13, 894963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, T.; Toptas, O.; Saylan, A.; Carver, H.; Turkoglu, S.A. Evaluation and Comparison of the Effects of Artesunate, Dexamethasone, and Tacrolimus on Sciatic Nerve Regeneration. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2019, 77, 1092.e1091–1092.e1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, X.-T.; Qian, N.-S.; Zhang, T.; Li, J.-M.; Li, X.-K.; Wang, P.; Zhao, D.-S.; Huang, G.; Zhang, L.; Fei, Z. Spinal astrocytic activation contributes to mechanical allodynia in a rat chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain model. PloS one 2013, 8, e60733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.-Y.; Zhou, Y.; Cui, W.-Q.; Hu, X.-M.; Du, L.-X.; Mi, W.-L.; Chu, Y.-X.; Wu, G.-C.; Wang, Y.-Q.; Mao-Ying, Q.-L. Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) dependent microglial activation promotes cisplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy in mice. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2018, 68, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannelli, L.D.C.; Pacini, A.; Micheli, L.; Tani, A.; Zanardelli, M.; Ghelardini, C. Glial role in oxaliplatin-induced neuropathic pain. Experimental neurology 2014, 261, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pevida, M.; Lastra, A.; Hidalgo, A.; Baamonde, A.; Menéndez, L. Spinal CCL2 and microglial activation are involved in paclitaxel-evoked cold hyperalgesia. Brain research bulletin 2013, 95, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Xiao, W.-H.; Bennett, G. The response of spinal microglia to chemotherapy-evoked painful peripheral neuropathies is distinct from that evoked by traumatic nerve injuries. Neuroscience 2011, 176, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotterman, T.M.; MacPherson, K.P.; Tansey, M.G.; Alvarez, F.J. Motor circuit synaptic plasticity after peripheral nerve injury depends on a central neuroinflammatory response and a CCR2 mechanism Journal of Neuroscience 2018, In revision, JN-RM-2945-17.

- Rotterman, T.M.; Haley-Johnson, Z.; Pottorf, T.S.; Chopra, T.; Chang, E.; Zhang, S.; McCallum, W.M.; Fisher, S.; Franklin, H.; Alvarez, M. Modulation of central synapse remodeling after remote peripheral injuries by the CCL2-CCR2 axis and microglia. Cell reports 2024, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotterman, T.M.; García, V.V.; Housley, S.N.; Nardelli, P.; Sierra, R.; Fix, C.E.; Cope, T.C. Structural preservation does not ensure function at sensory Ia–motoneuron synapses following peripheral nerve injury and repair. Journal of Neuroscience 2023, 43, 4390–4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotterman, T.M.; Alvarez, F.J. Microglia dynamics and interactions with motoneurons axotomized after nerve injuries revealed by two-photon imaging. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotterman, T.M.; Akhter, E.T.; Lane, A.R.; MacPherson, K.P.; García, V.V.; Tansey, M.G.; Alvarez, F.J. Spinal Motor Circuit Synaptic Plasticity after Peripheral Nerve Injury Depends on Microglia Activation and a CCR2 Mechanism. The Journal of Neuroscience 2019, 39, 3412–3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manich, G.; Gómez-López, A.R.; Almolda, B.; Villacampa, N.; Recasens, M.; Shrivastava, K.; González, B.; Castellano, B. Differential Roles of TREM2+ Microglia in Anterograde and Retrograde Axonal Injury Models. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Konishi, H.; Takai, T.; Kiyama, H. A DAP12-dependent signal promotes pro-inflammatory polarization in microglia following nerve injury and exacerbates degeneration of injured neurons. Glia 2015, 63, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, A. The axon reaction: a review of the principal features of perikaryal responses to axon injury. International review of neurobiology 1971, 14, 49–124. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, S.Y.; Gordon, T. The cellular and molecular basis of peripheral nerve regeneration. Molecular neurobiology 1997, 14, 67–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, R.W.; Lopes, M.C.; De Biase, L.M.; Valdez, G. Aging spinal cord microglia become phenotypically heterogeneous and preferentially target motor neurons and their synapses. Glia 2024, 72, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, R.W.; Lopes, M.C.; Settlage, R.E.; Valdez, G. Aging alters mechanisms underlying voluntary movements in spinal motor neurons of mice, primates, and humans. JCI Insight 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, J.; Youssef, M.M.; Santos, J.R.; Lee, J.; Park, J. Microglia and astrocytes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: disease-associated states, pathological roles, and therapeutic potential. Biology 2023, 12, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, B.E.; Patani, R. The microglial component of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain : a journal of neurology 2020, 143, 3526–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brites, D.; Vaz, A.R. Microglia centered pathogenesis in ALS: insights in cell interconnectivity. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience 2014, 8, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henkel, J.S.; Beers, D.R.; Zhao, W.; Appel, S.H. Microglia in ALS: the good, the bad, and the resting. Journal of neuroimmune pharmacology 2009, 4, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dols-Icardo, O.; Montal, V.; Sirisi, S.; López-Pernas, G.; Cervera-Carles, L.; Querol-Vilaseca, M.; Muñoz, L.; Belbin, O.; Alcolea, D.; Molina-Porcel, L. Motor cortex transcriptome reveals microglial key events in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology: Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation 2020, 7, e829. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.-X.; Zhang, M.-D.; Xu, H.-F.; Ye, H.-Q.; Chen, D.-F.; Wang, P.-S.; Bao, Z.-W.; Zou, S.-M.; Lv, Y.-T.; Wu, Z.-Y. Single-Nucleus RNA Sequencing Reveals the Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Disease-Associated Microglia in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Research 2024, 7, 0548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, O.H.; Rozhkov, N.V.; Shaw, R.; Kim, D.; Hubbard, I.; Fennessey, S.; Propp, N.; Phatnani, H.; Kwan, J.; Sareen, D.; et al. Postmortem Cortex Samples Identify Distinct Molecular Subtypes of ALS: Retrotransposon Activation, Oxidative Stress, and Activated Glia. Cell Reports 2019, 29, 1164–1177.e1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauregui, C.; Blanco-Luquin, I.; Macías, M.; Roldan, M.; Caballero, C.; Pagola, I.; Mendioroz, M.; Jericó, I. Exploring the Disease-Associated microglia state in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniatis, S.; Äijö, T.; Vickovic, S.; Braine, C.; Kang, K.; Mollbrink, A.; Fagegaltier, D.; Andrusivová, Ž.; Saarenpää, S.; Saiz-Castro, G.; et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of molecular pathology in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science 2019, 364, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreedharan, J.; Blair, I.P.; Tripathi, V.B.; Hu, X.; Vance, C.; Rogelj, B.; Ackerley, S.; Durnall, J.C.; Williams, K.L.; Buratti, E.; et al. TDP-43 Mutations in Familial and Sporadic Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Science 2008, 319, 1668–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.; Bharathi, V.; Sivalingam, V.; Girdhar, A.; Patel, B.K. Molecular mechanisms of TDP-43 misfolding and pathology in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience 2019, 12, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotter, E.L.; Chen, H.-J.; Shaw, C.E. TDP-43 proteinopathy and ALS: insights into disease mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Neurotherapeutics 2015, 12, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, R.; Adkins, R.; Yakura, J. Definition of complete spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 1991, 29, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauffer, E.S. Diagnosis and prognosis of acute cervical spinal cord injury. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1975, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klose, K.J.; Green, B.A.; Smith, R.S.; Adkins, R.H.; MacDonald, A.M. University of Miami Neuro-Spinal Index (UMNI): a quantitative method for determining spinal cord function. Paraplegia 1980, 18, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard Jr, F.M.; Bracken, M.B.; Creasey, G.; Ditunno Jr, J.F.; Donovan, W.H.; Ducker, T.B.; Garber, S.L.; Marino, R.J.; Stover, S.L.; Tator, C.H. International standards for neurological and functional classification of spinal cord injury. Spinal cord 1997, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheriyan, T.; Ryan, D.; Weinreb, J.; Cheriyan, J.; Paul, J.; Lafage, V.; Kirsch, T.; Errico, T. Spinal cord injury models: a review. Spinal cord 2014, 52, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M. Second Memoir on some principles of the pathology of the nervous system. Medico-chirurgical transactions 1840, 23, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.Y. Revisit Spinal Shock: Pattern of Reflex Evolution during Spinal Shock. Korean J Neurotrauma 2018, 14, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, H.C. On the symptomatology of total transverse lesions of the spinal cord; with special reference to the condition of the various reflexes. Medico-chirurgical transactions 1890, 73, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.A.; Sousa, N.; Reis, R.L.; Salgado, A.J. From basics to clinical: a comprehensive review on spinal cord injury. Progress in neurobiology 2014, 114, 25–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindan, R.; Joiner, E.; Freehafer, A.; Hazel, C. Incidence and clinical features of autonomic dysreflexia in patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal cord 1980, 18, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widerström-Noga, E.G.; Felipe-Cuervo, E.; Yezierski, R.P. Relationships among clinical characteristics of chronic pain after spinal cord injury. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation 2001, 82, 1191–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyinbo, C. Secondary injury mechanisms in traumatic spinal cord injury: a nugget of this multiply cascade. Acta neurobiologiae experimentalis 2011, 71, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, C.S.; Wilson, J.R.; Nori, S.; Kotter, M.; Druschel, C.; Curt, A.; Fehlings, M.G. Traumatic spinal cord injury. Nature reviews Disease primers 2017, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tator, C.H.; Fehlings, M.G. Review of the secondary injury theory of acute spinal cord trauma with emphasis on vascular mechanisms. Journal of neurosurgery 1991, 75, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, F.H.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Ma, A.; Guo, Q.; Li, Y.; Pukos, N.; Campbell, W.A.; Witcher, K.G.; Guan, Z.; et al. Microglia coordinate cellular interactions during spinal cord repair in mice. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 4096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarts, E.A.; Brennan, F.H. Evolving insights on the role of microglia in neuroinflammation, plasticity, and regeneration of the injured spinal cord. Frontiers in Immunology 2025, 16, 1621789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroner, A.; Almanza, J.R. Role of microglia in spinal cord injury. Neuroscience letters 2019, 709, 134370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; He, X.; Ren, Y. Function of microglia and macrophages in secondary damage after spinal cord injury. Neural regeneration research 2014, 9, 1787–1795. [Google Scholar]

- Brockie, S.; Hong, J.; Fehlings, M.G. The role of microglia in modulating neuroinflammation after spinal cord injury. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 9706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, S.; Kroner, A. Repertoire of microglial and macrophage responses after spinal cord injury. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2011, 12, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, J.; Ding, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhu, Y.-J. Current knowledge of microglia in traumatic spinal cord injury. Frontiers in neurology 2022, 12, 796704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockie, S.; Zhou, C.; Fehlings, M.G. Resident immune responses to spinal cord injury: role of astrocytes and microglia. Neural Regeneration Research 2024, 19, 1678–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, X.; Zheng, G.; Skutella, T.; Kiening, K.; Unterberg, A.; Younsi, A. Microglia: a promising therapeutic target in spinal cord injury. Neural regeneration research 2025, 20, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Di, J.; Kang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yao, S.; Liu, B.; Rong, L. TREM2 Impedes Recovery After Spinal Cord Injury by Regulating Microglial Lysosomal Membrane Permeabilization-Mediated Autophagy. Cell Proliferation 2025, e70047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, M.; Wicks, K.; Gardasevic, M.; Mace, K.A. Cx3CR1 expression identifies distinct macrophage populations that contribute differentially to inflammation and repair. Immunohorizons 2019, 3, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Lee, Y.; Song, J.; Lee, J.; Chang, S.-Y. Tissue-specific role of CX3CR1 expressing immune cells and their relationships with human disease. Immune network 2018, 18, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Aliberti, J.; Graemmel, P.; Sunshine, M.J.; Kreutzberg, G.W.; Sher, A.; Littman, D.R. Analysis of fractalkine receptor CX3CR1 function by targeted deletion and green fluorescent protein reporter gene insertion. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2000, 20, 4106–4114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, A.J.; Lavemia, C.; Owens, P.W. Anatomy and physiology of peripheral nerve injury and repair. AMERICAN JOURNAL OF ORTHOPEDICS-BELLE MEAD- 2000, 29, 167–178. [Google Scholar]

- Geuna, S.; Raimondo, S.; Ronchi, G.; Di Scipio, F.; Tos, P.; Czaja, K.; Fornaro, M. Histology of the peripheral nerve and changes occurring during nerve regeneration. International review of neurobiology 2009, 87, 27–46. [Google Scholar]

- Boissaud-Cooke, M.; Pidgeon, T.E.; Tunstall, R. Chapter 37 - The Microcirculation of Peripheral Nerves: The Vasa Nervorum. In Nerves and Nerve Injuries, Tubbs, R.S., Rizk, E., Shoja, M.M., Loukas, M., Barbaro, N., Spinner, R.J., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, 2015; pp. 507–523. [Google Scholar]

- Appenzeller, O.; Dhital, K.K.; Cowen, T.; Burnstock, G. The nerves to blood vessels supplying blood to nerves: the innervation of vasa nervorum. Brain Research 1984, 304, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sladjana, U.Z.; Ivan, J.D.; Bratislav, S.D. Microanatomical structure of the human sciatic nerve. Surgical and radiologic anatomy 2008, 30, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosius Lutz, A.; Lucas, T.A.; Carson, G.A.; Caneda, C.; Zhou, L.; Barres, B.A.; Buckwalter, M.S.; Sloan, S.A. An RNA-sequencing transcriptome of the rodent Schwann cell response to peripheral nerve injury. Journal of Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, D.; Pereira, J.A.; Gerber, J.; Tan, G.; Dimitrieva, S.; Yángüez, E.; Suter, U. Transcriptional profiling of mouse peripheral nerves to the single-cell level to build a sciatic nerve ATlas (SNAT). Elife 2021, 10, e58591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.L.; Yim, A.K.; Kim, K.-W.; Avey, D.; Czepielewski, R.S.; Colonna, M.; Milbrandt, J.; Randolph, G.J. Peripheral nerve resident macrophages share tissue-specific programming and features of activated microglia. Nature communications 2020, 11, 2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.L. Peripheral Nerve Macrophages and Their Implications in Neuroimmunity. Washington University in St. Louis, 2021.

- Tsuchiya, T.; Miyawaki, S.; Teranishi, Y.; Ohara, K.; Hirano, Y.; Ogawa, S.; Torazawa, S.; Sakai, Y.; Hongo, H.; Ono, H.; et al. Current molecular understanding of central nervous system schwannomas. Acta Neuropathologica Communications 2025, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruah, P.; Mahony, C.; Marshall, J.L.; Smith, C.G.; Monksfield, P.; Irving, R.I.; Dumitriu, I.E.; Buckley, C.D.; Croft, A.P. Single-cell RNA sequencing analysis of vestibular schwannoma reveals functionally distinct macrophage subsets. British Journal of Cancer 2024, 130, 1659–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzenelenbogen, Y.; Sheban, F.; Yalin, A.; Yofe, I.; Svetlichnyy, D.; Jaitin, D.A.; Bornstein, C.; Moshe, A.; Keren-Shaul, H.; Cohen, M. Coupled scRNA-Seq and intracellular protein activity reveal an immunosuppressive role of TREM2 in cancer. Cell 2020, 182, 872–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Smyth, M.J. TREM2 marks tumor-associated macrophages. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2020, 5, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, L.; Liu, Y. Identification of key genes and immune infiltration based on weighted gene co-expression network analysis in vestibular schwannoma. Medicine 2023, 102, e33470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, Y.; Sjöstrand, J. Origin of macrophages in Wallerian degeneration of peripheral nerves demonstrated autoradiographically. Experimental Neurology 1969, 23, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaco, S.; Gehrmann, J.; Raivich, G.; Kreutzberg, G.W. MHC-positive, ramified macrophages in the normal and injured rat peripheral nervous system. J Neurocytol 1992, 21, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Piao, X.; Bonaldo, P. Role of macrophages in Wallerian degeneration and axonal regeneration after peripheral nerve injury. Acta Neuropathologica 2015, 130, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattin, A.-L.; Burden, J.J.; Van Emmenis, L.; Mackenzie, F.E.; Hoving, J.J.; Calavia, N.G.; Guo, Y.; McLaughlin, M.; Rosenberg, L.H.; Quereda, V. Macrophage-induced blood vessels guide Schwann cell-mediated regeneration of peripheral nerves. Cell 2015, 162, 1127–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, T. Peripheral Nerve Regeneration and Muscle Reinnervation. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Chen, Q.; Parkinson, D.B.; Dun, X.-p. Analysis of Schwann cell migration and axon regeneration following nerve injury in the sciatic nerve bridge. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience 2019, 12, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzel, C.; Rohde, C.; Brushart, T.M. Pathway sampling by regenerating peripheral axons. Journal of Comparative Neurology 2005, 485, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, J.E.; Žygelytė, E.; Grenier, J.K.; Edwards, M.G.; Cheetham, J. Temporal changes in macrophage phenotype after peripheral nerve injury. Journal of neuroinflammation 2018, 15, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, R.; Jablonka-Shariff, A.; Broberg, C.; Snyder-Warwick, A.K. Macrophage roles in peripheral nervous system injury and pathology: Allies in neuromuscular junction recovery. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience 2021, 111, 103590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ydens, E.; Cauwels, A.; Asselbergh, B.; Goethals, S.; Peeraer, L.; Lornet, G.; Almeida-Souza, L.; Van Ginderachter, J.A.; Timmerman, V.; Janssens, S. Acute injury in the peripheral nervous system triggers an alternative macrophage response. Journal of neuroinflammation 2012, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraishi, W.; Yamasaki, R.; Hashimoto, Y.; Ko, S.; Kobayakawa, Y.; Isobe, N.; Matsushita, T.; Kira, J.-i. Clearance of peripheral nerve misfolded mutant protein by infiltrated macrophages correlates with motor neuron disease progression. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 16438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graber, D.J.; Hickey, W.F.; Harris, B.T. Progressive changes in microglia and macrophages in spinal cord and peripheral nerve in the transgenic rat model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Journal of neuroinflammation 2010, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, O.; Beers, D.R.; Henkel, J.S.; Appel, S.H. Peripheral nerve inflammation in ALS mice: cause or consequence. Neurology 2012, 78, 833–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Muriana, A.; Mancuso, R.; Francos-Quijorna, I.; Olmos-Alonso, A.; Osta, R.; Perry, V.H.; Navarro, X.; Gomez-Nicola, D.; López-Vales, R. CSF1R blockade slows the progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis by reducing microgliosis and invasion of macrophages into peripheral nerves. Scientific reports 2016, 6, 25663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiot, A.; Zaïdi, S.; Iltis, C.; Ribon, M.; Berriat, F.; Schiaffino, L.; Jolly, A.; de la Grange, P.; Mallat, M.; Bohl, D. Modifying macrophages at the periphery has the capacity to change microglial reactivity and to extend ALS survival. Nature neuroscience 2020, 23, 1339–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msheik, Z.; El Massry, M.; Rovini, A.; Billet, F.; Desmoulière, A. The macrophage: a key player in the pathophysiology of peripheral neuropathies. Journal of Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntosh, B.R.; Gardiner, P.F.; McComas, A.J. Skeletal muscle: form and function; Human kinetics: 2006.

- Lieber, R.L. Skeletal muscle structure, function, and plasticity; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: 2002.

- Liddel, E.; Sherrington, C. Reflexes in response to stretch (myotatic reflexes). Proceedings of the Royal Society, London, series B 1924, 96, 212–242. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, J.; Eccles, R.M.; Lundberg, A. Synaptic actions on motoneurones caused by impulses in Golgi tendon organ afferents. The Journal of Physiology 1957, 138, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendell, L.M.; Henneman, E. Terminals of single Ia fibers: location, density, and distribution within a pool of 300 homonymous motoneurons. Journal of Neurophysiology 1971, 34, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bączyk, M.; Manuel, M.; Roselli, F.; Zytnicki, D. Diversity of Mammalian Motoneurons and Motor Units. In Vertebrate Motoneurons; Springer: 2022; pp. 131-150.

- Kernell, D. The Motoneurone and its Muscle Fibres; Oxford University Press UK: 2006.

- Manuel, M.; Zytnicki, D. Alpha, beta and gamma motoneurons: functional diversity in the motor system’s final pathway. Journal of integrative neuroscience 2011, 10, 243–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhindi, A.; Boehm, I.; Forsythe, R.O.; Miller, J.; Skipworth, R.J.E.; Simpson, H.; Jones, R.A.; Gillingwater, T.H. Terminal Schwann cells at the human neuromuscular junction. Brain Commun 2021, 3, fcab081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balice-Gordon, R.J. Schwann cells: Dynamic roles at the neuromuscular junction. Current Biology 1996, 6, 1054–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, R.L.; Valdez, G. Origin, identity, and function of terminal Schwann cells. Trends in Neurosciences 2024, 47, 432–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, R.L.; Mikesh, M.; Lee, Y.i.; Thompson, W.J. Morphological remodeling during recovery of the neuromuscular junction from terminal Schwann cell ablation in adult mice. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 11132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, A.; Kanji, A.; Allbrook, D. The structure of the satellite cells in skeletal muscle. Journal of anatomy 1965, 99, 435. [Google Scholar]

- Mauro, A. Satellite cell of skeletal muscle fibers. The Journal of biophysical and biochemical cytology 1961, 9, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, A.B.; Smith, G.R.; Raue, U.; Begue, G.; Minchev, K.; Ruf-Zamojski, F.; Nair, V.D.; Wang, X.; Zhou, L.; Zaslavsky, E.; et al. Single-cell transcriptional profiles in human skeletal muscle. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Micheli, A.J.; Spector, J.A.; Elemento, O.; Cosgrove, B.D. A reference single-cell transcriptomic atlas of human skeletal muscle tissue reveals bifurcated muscle stem cell populations. Skeletal Muscle 2020, 10, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Tian, L.; Mikesh, M.; Lichtman, J.W.; Thompson, W.J. Terminal Schwann Cells Participate in Neuromuscular Synapse Remodeling during Reinnervation following Nerve Injury. The Journal of Neuroscience 2014, 34, 6323–6333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, M.; Woolf, C. Terminal Schwann cells elaborate extensive processes following denervation of the motor endplate. Journal of neurocytology 1992, 21, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermedo-García, F.; Zelada, D.; Martínez, E.; Tabares, L.; Henríquez, J.P. Functional regeneration of the murine neuromuscular synapse relies on long-lasting morphological adaptations. BMC Biology 2022, 20, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, Y.-J.; Thompson, W.J. Schwann cell processes guide regeneration of peripheral axons. Neuron 1995, 14, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, P.; Chen, M.; Rao, M.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, M.; Xu, R.; Hu, X.; Chen, R.; Chai, W.; Huang, X. Deciphering immune landscape remodeling unravels the underlying mechanism for synchronized muscle and bone aging. Advanced Science 2024, 11, 2304084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larouche, J.A.; Wallace, E.C.; Spence, B.D.; Buras, E.; Aguilar, C.A. Spatiotemporal mapping of immune and stem cell dysregulation after volumetric muscle loss. JCI insight 2023, 8, e162835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Alabdullatif, S.; Homma, S.T.; Alekseyev, Y.O.; Zhou, L. Expansion and pathogenic activation of skeletal muscle–resident macrophages in mdx5cv/Ccr2−/− mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2025, 122, e2410095122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essex, A.L.; Huot, J.R.; Deosthale, P.; Wagner, A.; Figueras, J.; Davis, A.; Damrath, J.; Pin, F.; Wallace, J.; Bonetto, A.; et al. Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells 2 (TREM2) R47H Variant Causes Distinct Age- and Sex-Dependent Musculoskeletal Alterations in Mice. J Bone Miner Res 2022, 37, 1366–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacconi, S.; Giudetti, A.M.; Blangero, F.; Meugnier, E.; El-jaafari, A.; Longo, S.; Angilé, F.; Fanizzi, F.P.; Canaple, L.; Jalabert, A.; et al. LAM/TREM2 <sup>+</sup> macrophages release extracellular vesicles and extracellular lipid droplets which modulate the phenotype of recipient macrophages and homeostasis of skeletal muscle cells. bioRxiv, 6349; .12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.-Y.; Santosa, K.B.; Jablonka-Shariff, A.; Vannucci, B.; Fuchs, A.; Turnbull, I.; Pan, D.; Wood, M.D.; Snyder-Warwick, A.K. Macrophage-derived vascular endothelial growth factor-A is integral to neuromuscular junction reinnervation after nerve injury. Journal of Neuroscience 2020, 40, 9602–9616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyke, J.M.; Smit-Oistad, I.M.; Macrander, C.; Krakora, D.; Meyer, M.G.; Suzuki, M. Macrophage-mediated inflammation and glial response in the skeletal muscle of a rat model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Experimental neurology 2016, 277, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, I.M.; Phatnani, H.; Kuligowski, M.; Tapia, J.C.; Carrasco, M.A.; Zhang, M.; Maniatis, T.; Carroll, M.C. Activation of innate and humoral immunity in the peripheral nervous system of ALS transgenic mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2009, 106, 20960–20965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dachs, E.; Hereu, M.; Piedrafita, L.; Casanovas, A.; Calderó, J.; Esquerda, J.E. Defective neuromuscular junction organization and postnatal myogenesis in mice with severe spinal muscular atrophy. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology 2011, 70, 444–461. [Google Scholar]

- Deczkowska, A.; Weiner, A.; Amit, I. The Physiology, Pathology, and Potential Therapeutic Applications of the TREM2 Signaling Pathway. Cell 2020, 181, 1207–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chtarto, A.; Humbert-Claude, M.; Bockstael, O.; Das, A.T.; Boutry, S.; Breger, L.S.; Klaver, B.; Melas, C.; Barroso-Chinea, P.; Gonzalez-Hernandez, T. A regulatable AAV vector mediating GDNF biological effects at clinically-approved sub-antimicrobial doxycycline doses. Molecular therapy Methods & clinical development 2016, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, C. A comprehensive review of AAV-mediated strategies targeting microglia for therapeutic intervention of neurodegenerative diseases. Journal of Neuroinflammation 2024, 21, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoudi, N.; Willen, J.; Daniels, C.; Jenkins, B.A.; Furber, E.C.; Kothiya, M.; Banjoko, M.B.; Gowda, R.; Hendricks, J.; Fang, Y.-Y.; et al. Microglial-targeted Gene Therapy: Developing a Disease Modifying Treatment for ALSP Associated with CSF1R Mutations (ALSP-CSF1R) (P11-4.012). Neurology 2024, 102, 3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).