1. INTRODUCTION

Epidemiological research indicates that 70-90% of all traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) are mild, which are common among professional athletes engaged in contact and collision sports and military personnel [

1]. Mild TBIs (mTBIs) are characterized by a transient disturbance in brain function with short-lived neurological symptoms, such as headache, dizziness, and confusion, among others, along with normal neuroimaging results (CT scan) [

2,

3,

4]. However, 10-25% of mTBI patients develop persistent post-concussion symptoms, which are associated with long-term cognitive deficits and white matter damage [

3,

5,

6]. Nevertheless, the underlying mechanisms are not well defined, and currently, no effective treatment is available for mTBI-related pathogenesis.

Diffuse axonal injury (DAI) is a key pathology following mTBI, characterized by axonal stretching, mitochondrial swelling, cytoskeletal disorganization, and transport dysfunction, accompanied by the accumulation of amyloid precursor protein (APP) [

7,

8]. Moreover, astrocyte reactivity and microglial activation are critical early responses to TBI-induced extracellular changes [

4,

9]. These cells exert complex and heterogeneous responses, including altered gene expression, hypertrophy, proliferation, and secretion of pro- and/or anti-inflammatory cytokines to regulate inflammatory responses and/or subdue the spread of damage [

10]. The formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and oxidative stress, mediated by the pro-inflammatory microglia and astrocytes, has been implicated in mTBI-mediated axonal injury and pathogenesis, exacerbating brain damage, and hindering brain repair and neurological functional recovery [

4,

7,

8].

Our research, along with others, has unveiled that stimulation of the Na

+/H

+ exchanger isoform 1 (NHE1), a vital pH-regulatory plasma membrane protein, facilitates the efflux of H

+ in exchange for the influx of Na

+, in maintaining optimal intracellular pH (pH

i) homeostasis [

9]. This process is essential for continuous activation of NADPH oxidase (NOX2) and the release of cytokines in neurons [

9,

11], proinflammatory microglia [

9], and reactive astrocytes [

12]. In our recent study, we reported that selective deletion of the microglial NHE1 protein in

Cx3cr1-CreER+/-;Nhe1flox/flox mice reduced neuroinflammation, enhanced remyelination, and improved neurological functional outcomes in a moderate-TBI mouse model with open-skull injury [

9]. However, whether pathological stimulation of NHE1 protein expression and activity plays a role in oxidative stress and the development of DAI associated with repetitive mTBI (r-mTBI) pathogenesis remains unexplored.

In this current study, we investigated r-mTBI-induced changes in the expression of the NHE1 protein, axonal damage markers, neuroinflammation, and oxidative stress. Additionally, we tested the efficacy of post-r-mTBI administration of NHE1 selective inhibitor, HOE642, in reducing brain injury and sensorimotor and cognitive deficits. Our findings reveal that post-r-mTBI pharmacological inhibition of the NHE1 protein in C57BL/6J mice led to a reduction in gliosis, axonal damage, oxidative stress, and MRI diffusion tensor imaging (DTI)-detected white matter damage. Moreover, this intervention resulted in an improvement in locomotor and cognitive functional recovery. Thus, targeting the NHE1 protein may serve as a potential therapeutic strategy for reducing mTBI pathology and improving neurological function.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Animals

All animal experiments described in this study were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and adhered to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Additionally, all studies were reported in accordance with the Animal Research: Reporting In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines [

13]. Food and water were provided to animals ad libitum and animals were housed in a temperature-controlled environment with 12/12hr light-dark cycles. All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used for experiments and any animal suffering. The number of animals used per figure can be found in

Table S1. Adult C57BL/6J wild-type (WT) (male, 2-3 months old) were used in the study. For transgenic knockout study,

Cx3cr1-CreER+/- control (Ctrl) mice and

Cx3cr1-CreER+/-; Nhe1f/f conditional knockout (

Nhe1 cKO) mice were used as described in our previous study (male and female, 2-3 months old) [

9]. See Supplemental Materials for detailed methods.

2.2. Repetitive Mild (r-mTBI) Procedures

Adult C57BL/6J WT or transgenic mice were anesthetized using 1.5% isoflurane as previously described [

9]. Mice were placed on a stereotaxic frame mounted with a controlled cortical impact (CCI) device (Leica Biosystems, Germany). Mice were impacted at 5 m/s with a 5-mm blunt tip, with a strike depth of 1 mm and a dwell time of 200 ms, mimicking a mTBI [

14]. Repetitive injuries occurred on days 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 for a total of 5 impacts with an inter-mTBI interval of 48 hrs. Stepwise changes in righting time and apnea time (indicators of neurological functional recovery) after each impact were recorded [

14]. Sham animals underwent the same repetitive procedures without receiving impacts. See Supplemental Materials for detailed methods.

2.3. Post-r-mTBI HOE642 Treatment

For the inhibitor study, C57BL/6J WT mice were used. NHE1 preparation and administration methods were the same as previously described [

9]. The potent NHE1 inhibitor, HOE642 (Cariporide, Sigma-Aldrich, USA), was dissolved at 1 mg/ml in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) stock solution. Immediately before injection, the solution was diluted to 0.025 mg/ml in PBS. For the vehicle control (Veh), 2.5% DMSO in PBS was used. Veh or HOE642 (0.3 mg/kg body weight/day, i.p.) was administered twice daily for 7 days starting at 24 hours after the 5

th impact.

2.4. Behavioral Function Tests

Neurological functional impairments in mice were screened in a blinded manner with the rotarod accelerating test, open field test, y-maze spontaneous alternation test, and y-maze novel spatial recognition test. All tests listed were considered reliable for identifying and quantifying sensorimotor and cognitive impairments in rodent models [

10,

15,

16,

17]. Behavioral tests were performed as previously described [

9,

10,

16,

17] with slight modification. See Supplemental Materials for detailed methods.

2.5. MRI and DTI of Ex Vivo Brains

MRI and DTI procedures were performed as previously described [

9,

10]. At 60 days post first-injury (dpi), the same cohort of mice that underwent behavioral assessments were humanely euthanized through CO

2 overdose. Subsequently, they underwent transcardial perfusion with ice-cold 0.1M PBS (pH 7.4) followed by an infusion of 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). The mice were then decapitated, keeping the brains intact within the skull to prevent anatomical distortion as previously outlined [

9,

10]. Regions of interest (ROIs) were delineated, segmenting the corpus callosum (CC), hippocampal CA1, internal capsule, and external capsule in both hemispheres from four scanned sections in each brain. Fractional anisotropy (FA), mean diffusivity (MD), axial diffusivity (AD), and radial diffusivity (RD) values were then calculated for each ROI, employing previously described methodology [

9,

10]. See Supplemental Materials for detailed methods.

2.6. Immunofluorescent Staining and Analysis

Immunofluorescent staining procedures were similar to those used in previous studies [

9,

10,

16,

17]. Mice were humanely euthanized and perfused with 4% PFA on either 15 or 60 dpi as previously described above. Coronal sections (25 μm, at the level of 1.46 mm posterior to bregma) were used for immunostaining.

Table S2 depicts the primary and secondary antibodies used in immunostaining. Negative controls were established by staining brain sections with secondary antibodies only (

Figures S1-S2). A minimum of three fluorescent images were captured for each area under a 40x lens using a Nikon A1R inverted confocal laser-scanning microscope (Olympus, Japan). Identical digital imaging acquisition parameters were used, and images were obtained and analyzed in a blinded manner throughout the study. Field intensity was measured within the delineated regions and cell counts were measured by converting into binary images with semi-automated cell counting using consistent threshold parameters for specific cell types. See Supplemental Materials for detailed methods.

2.7. IMARIS 3D Reconstruction and Analysis

Z-stack analysis and 3D cell reconstruction were performed using the IMARIS 10.0.1 program (Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, UK). Initially, a surface was generated for GFAP+, IBA1+, or OLIG2+ immunosignals within their respective Z-stacks. Consistent surface detail and thresholding parameters were applied across stacks of the same staining. For MAP2+-stained Z-stacks, the filament tool was utilized to recreate the cytoskeletal protein, employing the ‘Autopath (loops) no Soma and no Spine’ detection type and selecting the ‘Multiscale Points’ option to enable the setting of variable filament diameters. The thinnest and largest diameters remained consistent across all MAP2+-stained Z-Stacks, and the same threshold was applied. The NHE1 immunosignal was replicated using the spots tool, with a uniform XY diameter across all stacks. Following the reconstruction of both green (GFAP+, IBA1+, OLIG2+, or MAP2+) and red (NHE1) signals, a filter was applied to remove all spots outside the surface or filament, retaining only the reconstructed NHE1 immunoreactive spots within the various reconstructed structures. Subsequently, the ‘Total Number of Spots’ was plotted for GFAP+, IBA1+, and OLIG2+ immunostaining, while the ‘Filament Length (Sum)’ was plotted for the MAP2+ immunostaining.

2.8. Colocalization Analysis

We employed the ImageJ (NIH, USA) colocalization tool JaCoP (Just Another Colocalization Plugin v.2.1.1) to quantify the extent of overlap between NOX2 immunostaining and cell type markers. Stacked multichannel images were created from Z-stacks collected for each brain region and subsequently split by channel. The 8-bit channel image for NOX2 (imaged at 561 nm) and the cell-type marker (NeuN+ 488 nm) were subsequently analyzed by the JaCoP to determine M1 and M2 Mander’s Overlap Coefficients as described by the developers [

18]. This generated the fraction of pixels for cell-type marker staining that also have NOX2

+ immunostaining signals. All images were set to the same positive vs. negative immunostaining signal threshold during analysis.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were conducted with impartial study design and analyses. Investigators were blinded to experimental groups until data analysis was complete whenever feasible. Power analyses were performed based on the mean and variability of data from our laboratory. N = 12 mice/group for behavioral tests, N = 6 mice/group for immunostaining and MRI/DTI were sufficient to give us 80% power to detect 10% changes with 0.05 one-sided significance. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM and all data were tested for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. For comparing two conditions, a two-tailed Student’s t-test with 95% confidence was employed. For comparing three conditions or more, a one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) analysis was used. Statistical significance was considered at a p value < 0.05 (Prism, GraphPad, USA). Non-normally distributed data were analyzed using a two-tailed unpaired Mann-Whitney U-test with a confidence level of 95% or other appropriate alternative tests according to the data. All data was included unless appropriate outlier analysis suggests otherwise.

3. RESULTS

3.1. r-mTBI Mice Displayed Neurological Function Deficits in Both Acute and Chronic Phases

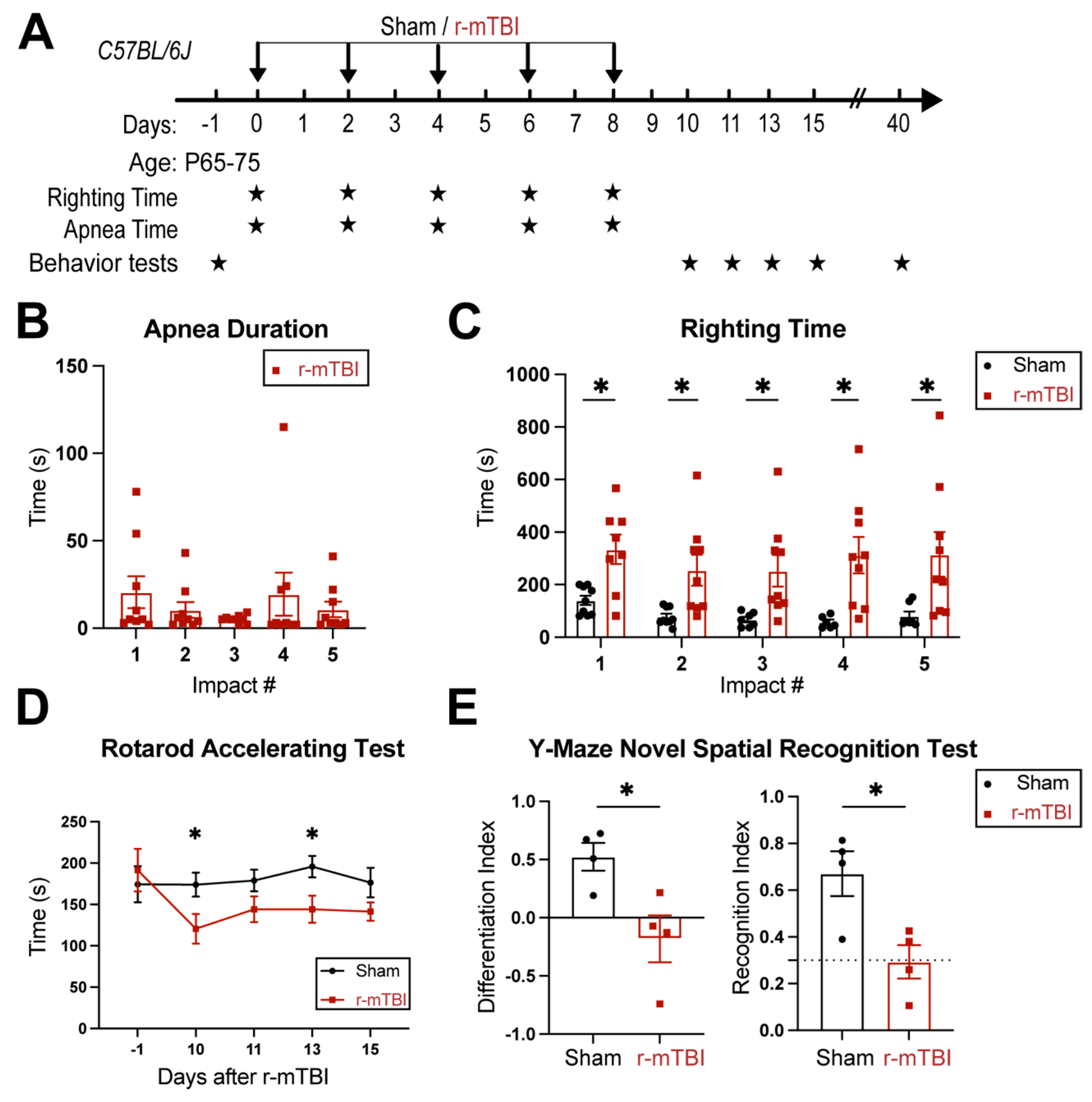

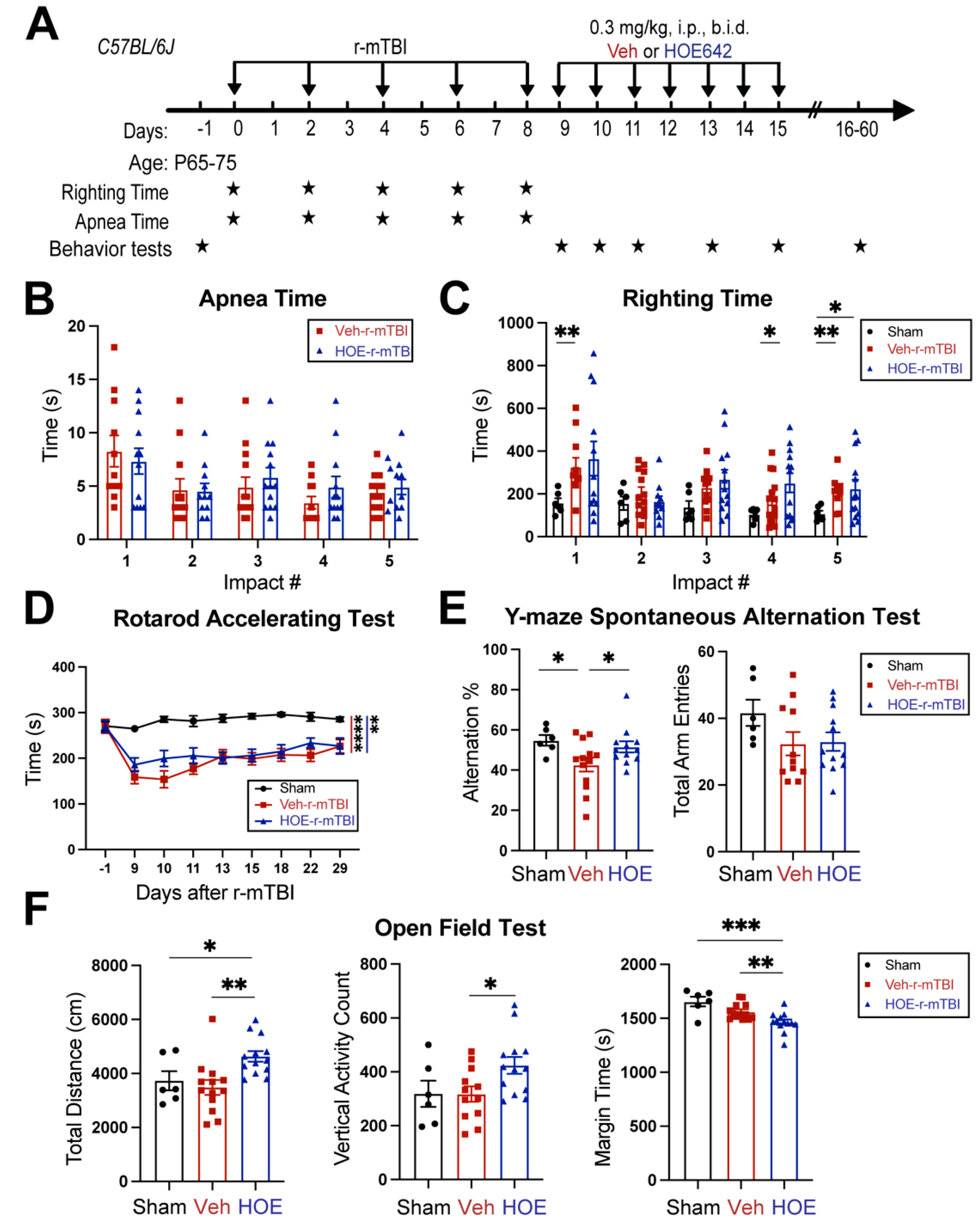

R-mTBIs were induced by repetitive injuries in C57BL/6J mice, with a total of 5 impacts on 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 dpi with an inter-concussion interval of 48 hrs (

Figure 1A). Sham control mice underwent the same procedure without receiving the impacts. Following each impact, all r-mTBI animals exhibited a period of temporary cessation of breathing that was followed by an extended phase of unresponsiveness (

Figure 1B). No significant differences were observed among apnea times detected between the injury days. Moreover, compared to the sham-operated mice, the r-mTBI mice demonstrated significantly higher righting times after all impacts (p < 0.05,

Figure 1C), suggesting that a longer time for restoration of neurological functions was required for r-mTBI mice [

14]. Additionally, compared to the sham group, the r-mTBI mice displayed significantly poorer motor functions in the rotarod accelerating test on 10 and 13 dpi (p < 0.05,

Figure 1D). During the chronic phase at 40 dpi, the r-mTBI mice demonstrated a worsened performance reflected by significantly reduced differentiation index (DI) and recognition index (RI) in the y-maze novel spatial recognition test compared to the sham mice (p < 0.05,

Figure 1E), implying a poor spatial recognition memory function [

15] (

Figure 1E). No changes were detected on the spatial working memory test (y-maze spontaneous alternation test, Fig. S3). In the open field test, the r-mTBI mice showed moderate hyperactivity compared to the sham mice (p = 0.08), but there were no statistically significant differences in locomotor activity or anxiety (Fig. S3). Taken together, these findings indicate that our r-mTBI model triggered sustained motor and cognitive neurological function impairments in both acute and chronic stages post-mTBI, which is consistent with previous reports [

14].

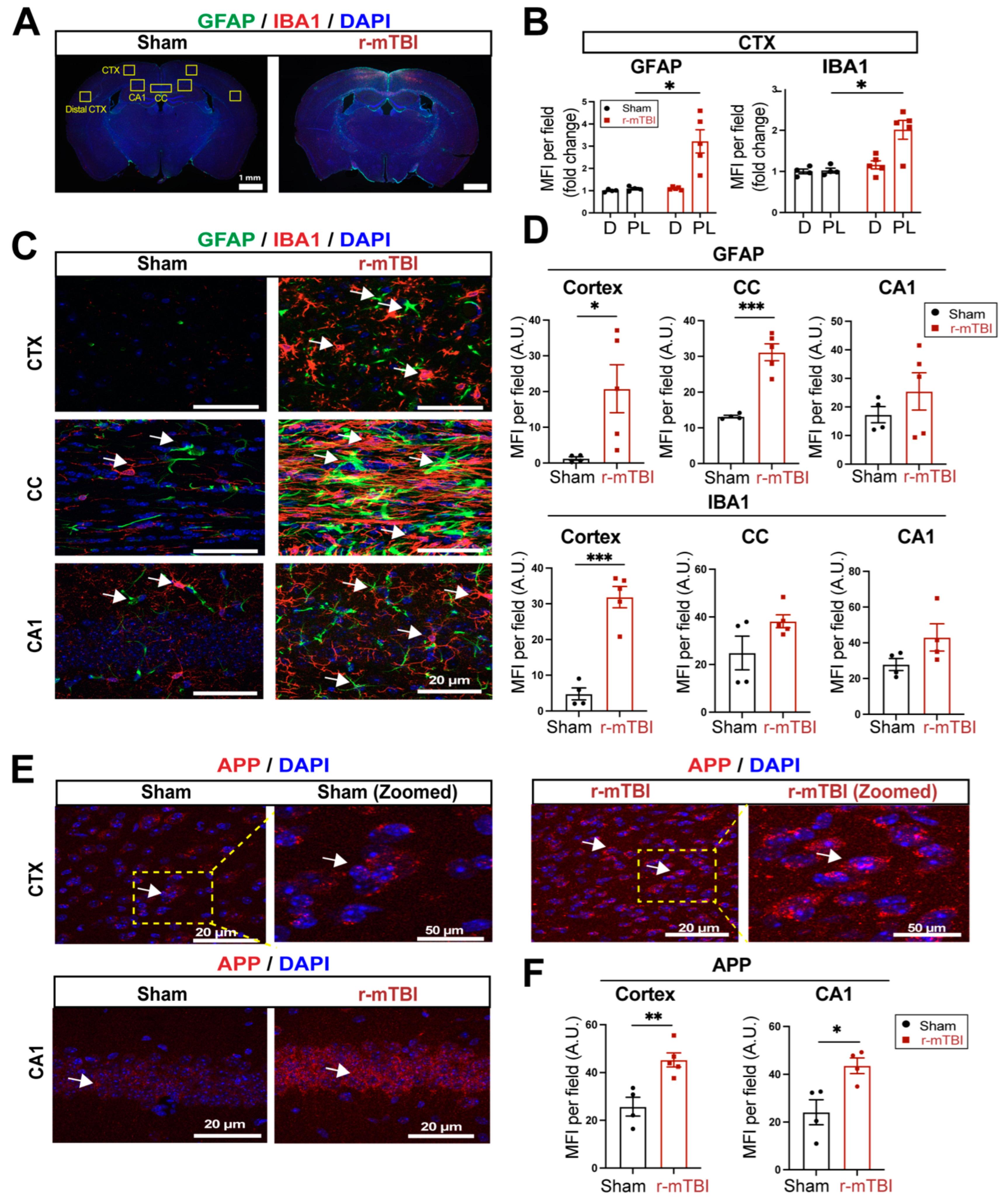

3.2. r-mTBI Stimulates Robust Astrogliosis and Microgliosis in Cerebral Cortical, Hippocampal, and White Matter Tissues

We then assessed levels of astrogliosis and microgliosis by immunostaining for the reactive astrocyte marker protein GFAP (glial fibrillary acidic protein) and the microglial marker protein IBA1 (ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1) expression at 15 dpi. Compared to sham-operated mice, r-mTBI mice displayed significant increases in immunoreactivity of GFAP

+ and IBA1

+ protein especially in the bi-hemispheric peri-lesion areas (p < 0.05,

Figure 2A-B). In contrast to the “resting” cellular morphology of both astrocytes and microglia in the sham brains,

Figure 2C displayed ameboid phenotypic morphology of microglia with larger cell bodies and fewer processes, and reactive astrocytes that displayed typical morphological changes such as hypertrophy and elongated cell processes throughout the cortex (CTX), CC, and hippocampal CA1 regions, indicating pronounced activation of GFAP

+ astrocytes and IBA1

+ microglial cells in these areas of r-mTBI mice

at 15 dpi. Additionally, the mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) per field for GFAP

+ astrocytes and IBA1

+ microglia also significantly increased in the CTX and CC of these r-mTBI brains (p < 0.05,

Figure 2C-D), demonstrating certain brain regions susceptible to glial activation in response to r-mTBI. In assessing axonal damage,

Figure 2E-F showed an increased deposition of APP with significantly higher MFI in the CTX and hippocampal CA1 neurons of r-mTBI brains than in the sham brains (p < 0.05), implicating axonal transport dysregulation [

7,

8]. Taken together, these data demonstrate the early occurrence of astrogliosis, microgliosis, and axonal damage in r-mTBI-induced pathogenesis development.

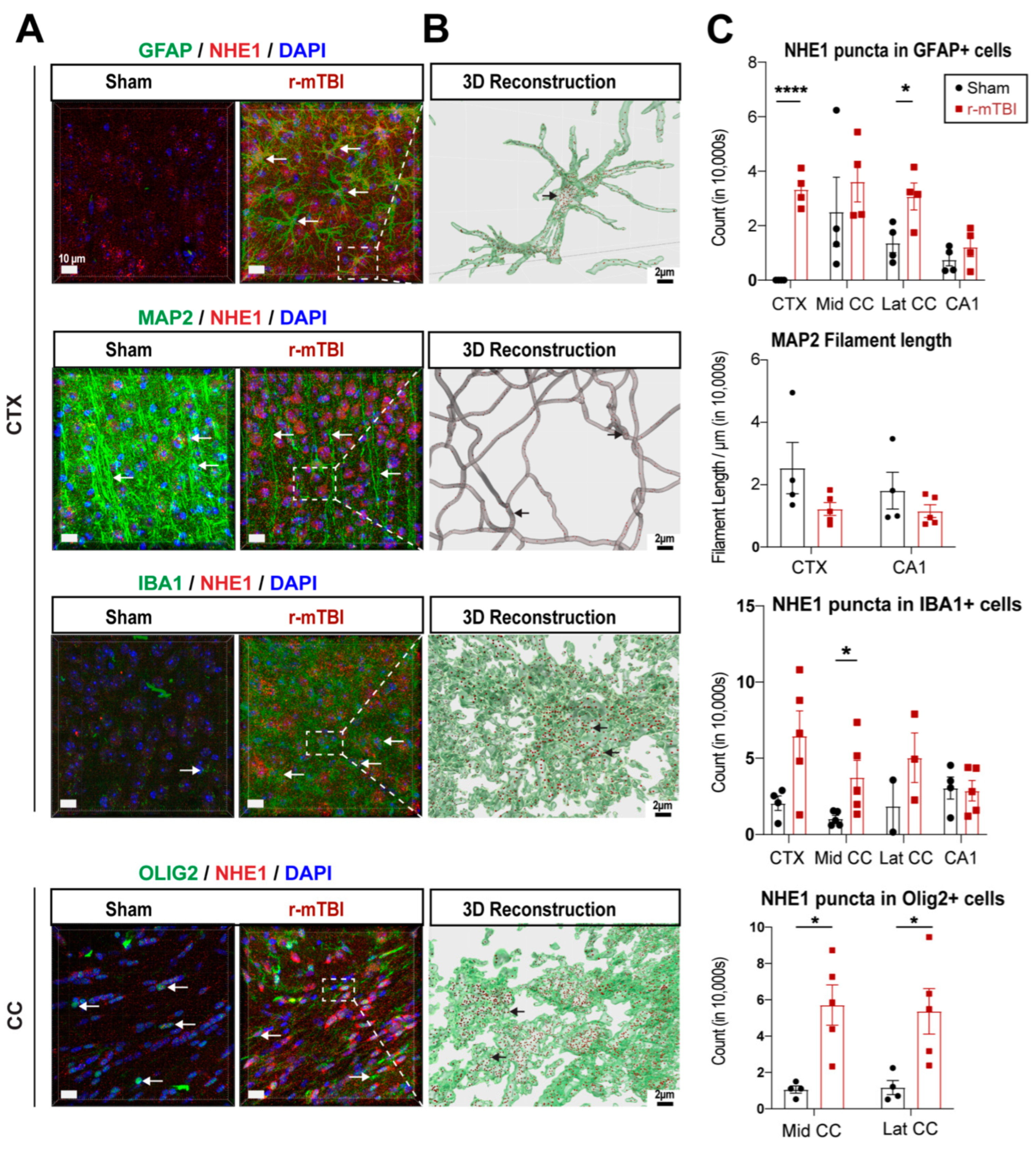

3.3. r-mTBI Upregulated NHE1 Protein Expression in Multiple Brain Cell Types

NHE1 protein has been shown to be involved in inflammatory responses in astrocytes and microglia after open-skull moderate-TBI or ischemic stroke mouse models [

9,

12]. Here we investigated whether NHE1 protein expression was altered in GFAP

+ astrocytes, IBA1

+ microglia, MAP2

+ neurons, and OLIG2

+ oligodendrocytes at 15 dpi after r-mTBI using immunofluorescence staining. Low levels of NHE1 protein expression were detected in GFAP

+ astrocytes, IBA1

+ microglia, and OLIG2

+ oligodendrocytes throughout the CTX, CC, and CA1 regions in sham control brains (

Figure 3A). In contrast, the r-mTBI brains at 15 dpi showed significant increases in NHE1 protein immunoreactive signals in GFAP

+ astrocytes, IBA1

+ microglia, and OLIG2

+ cells (arrows,

Figure 3A), which were clearly illustrated in the Imaris 3D reconstructed images showing increased NHE1

+ puncta in the soma and processes of GFAP

+, IBA1

+, and OLIG2

+ cells of r-mTBI brains (

Figure 3B). Especially, NHE1 expression showed statistically significant increases in the GFAP

+ astrocytes in the CTX and lateral CC regions (p < 0.0001 and p < 0.05, respectively;

Figure 3C), in the OLIG2

+ cells in both the middle and lateral CC regions (p < 0.05;

Figure 3C), and in IBA1

+ microglia in the middle CC region in r-mTBI brains (p < 0.05;

Figure 3C). While we did not detect changes in NHE1 protein expression in MAP2

+ filaments between sham and r-mTBI brains, we found a decrease in MAP2

+ filament lengths in the CTX and CA1 regions for the r-mTBI brains; however, that did not reach statistical significance (p > 0.05;

Figure 3C). Taken together, these data suggest that r-mTBI increased expression of NHE1 protein in various cell types in multiple brain regions. These findings motivated us to investigate whether the blockade of NHE1 protein would restore brain cell homeostasis and reduce r-mTBI-mediated brain damage.

3.4. Delayed Administration of Selective NHE1 Protein Inhibitor HOE642 Significantly Improved Neurological Behavioral Functions Post-r-mTBI

We examined whether a delayed administration of NHE1 protein inhibitor HOE642 could attenuate neurological deficits in r-mTBI mice.

Figure 4A illustrates the regimen of administration of Veh (DMSO) or HOE642 (0.3 mg/kg body weight/day, b.i.d., 8 h apart) from 9-15 dpi post-sham or r-mTBI. In general, sham-operated mice had significantly lower righting times than the r-mTBI mice (Veh- and HOE-cohort) after impact #1 (p < 0.01) and impacts #4-5 (p < 0.05), suggesting that r-mTBI mice required a longer time for neurological restoration when compared to sham mice [

14]. Similar apnea and righting times were detected in the Veh- and HOE-cohort mice prior to their treatment, suggesting similar initial neurological deficits in both groups (

Figure 4B-C). At 9-29 dpi, all r-mTBI mice (both Veh- and HOE-treated mice) exhibited a significantly decreased performance in the rotarod accelerating test after r-mTBI, when compared to sham animals (p < 0.01;

Figure 4D). Compared to the Veh-treated mice, the HOE-treated mice showed improved motor performance with higher latency on the rotating rods at 9, 10, 11, and 22 dpi; however, this observation did not reach statistical significance (

Figure 4D, p = 0.1). Moreover, the Veh-treated r-mTBI mice displayed sustained working memory deficits with a significant decrease in arm alternations (with similar arm entries) in the y-maze spontaneous alternation test at the chronic phase of 32 dpi, compared to the sham mice (p < 0.05;

Figure 4E), which was almost fully attenuated in the HOE-treated r-mTBI group (

Figure 4E, p < 0.05). At 30 dpi, the Veh-treated mice exhibited similar locomotor activity as the sham control mice in the open field test (

Figure 4F). Interestingly, the HOE-treated r-mTBI mice showed significantly stimulated locomotor functions reflected by increased total travel distance and vertical activity counts, compared to the Veh-treated mice (p < 0.05;

Figure 4F). These HOE-treated r-mTBI mice concurrently displayed reduced anxiety with significantly decreased margin time than the Veh-treated r-mTBI mice (p < 0.01;

Figure 4F). However, no significant differences in the index ratios (DI, p = 0.3; and RI, p = 0.2) were observed between the Veh-treated and HOE-treated r-mTBI mice when assessed with the y-maze novel spatial recognition test at 39 dpi, suggesting there were no differences in spatial reference memory between the two groups (Fig. S4). Taken together, these findings demonstrated that post-r-mTBI pharmacological blockade of the NHE1 protein with HOE642 significantly improved both locomotor and cognitive neurological functions in the subacute and chronic phase of r-mTBI.

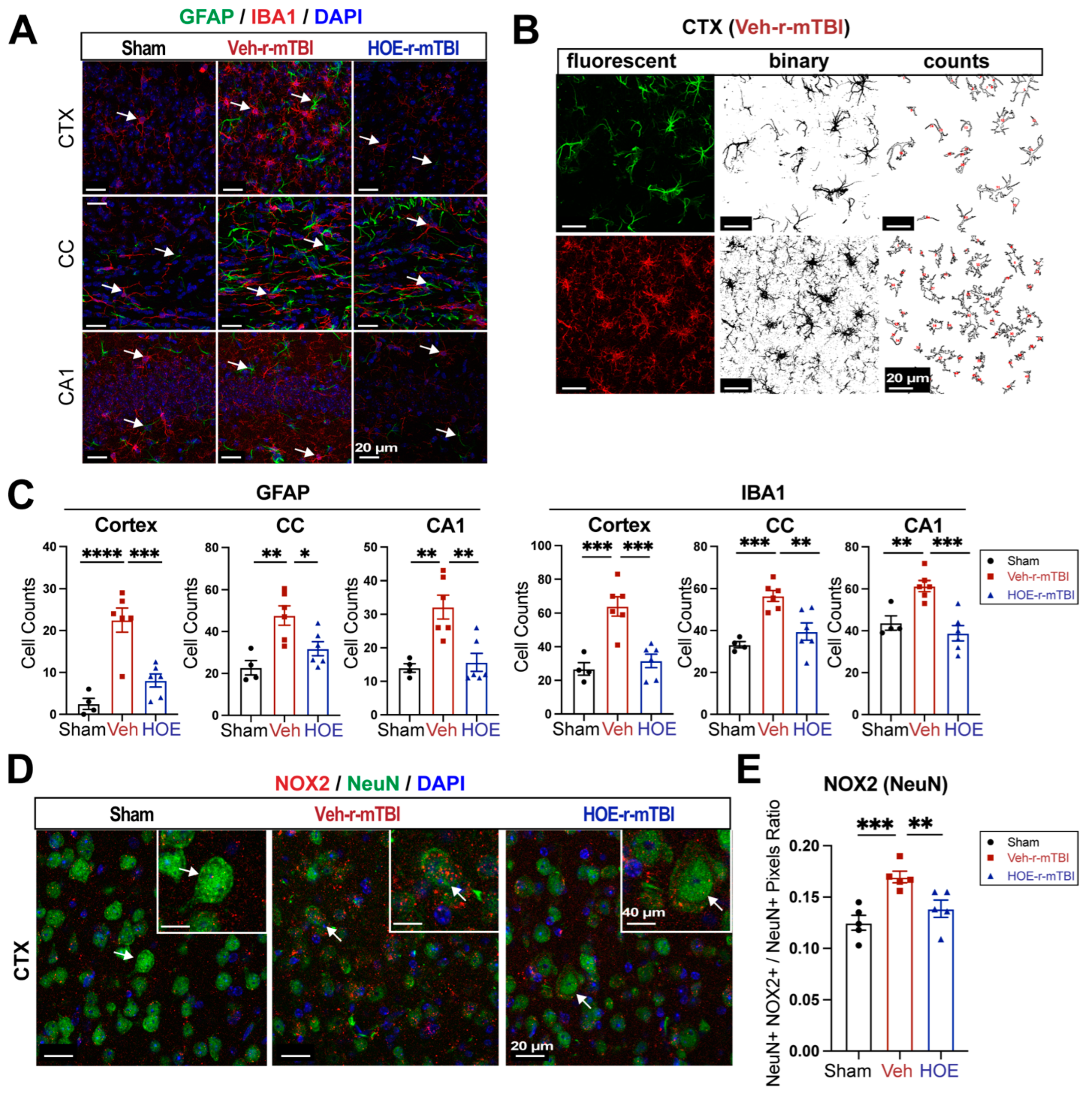

3.5. Pharmacological Inhibition of NHE1 with HOE642 Reduced Gliosis and Oxidative Damage over Broad Brain Regions after r-mTBI

To evaluate whether delayed pharmacological blockade of the NHE1 protein would impact levels of astrogliosis and microgliosis following r-mTBI, we conducted immunostaining for GFAP

+ and IBA1

+ expression in the CTX, CC, and CA1 regions in both Veh- and HOE-treated r-mTBI mice at 60 dpi. Compared to sham-operated mice, the Veh-treated r-mTBI mice exhibited ameboid cell morphologies for both GFAP

+ and IBA1

+ cells (

Figure 5A), akin to those observed in the r-mTBI cohort at 15 dpi (

Figure 2C). Significant increases in GFAP

+ and IBA1

+ cell counts in the three brain regions were also identified through unbiased semi-automatic quantification of cell counts using binary images in ImageJ software (

Figure 5B-C, p < 0.01), indicating robust activation of both reactive astrocytes and microglia. In contrast, the HOE-treated r-mTBI brains displayed similar cell morphologies the resting phenotypes observed in sham brains at 15 dpi (

Figure 5A and

Figure 2C), along with significantly reduced cell counts of both GFAP

+ and IBA1

+ cells throughout all three brain regions (

Figure 5C, p < 0.05). In evaluating oxidative stress-induced changes, immunostaining of phosphor-p47-phox (p-p47), an active subunit of the NOX2 complex, was performed at 60 dpi. p-p47 is a crucial subunit involved in NOX2 activation [

19]. We observed that Veh-treated r-mTBI mice exhibited visually higher p-p47 NOX2 expression within NeuN

+ neurons in the CTX, reflected by a significantly higher overlap percentage when compared to sham brains (arrows,

Figure 5D-E, p < 0.001). Conversely, HOE-treated r-mTBI mice displayed lower p-p47 NOX expression within NeuN

+ neurons in the CTX, appearing more akin to sham tissue at 60 dpi (arrows,

Figure 5D). Additionally, HOE-treated r-mTBI brains exhibited a significant decrease in the overlap percentage of p-p47 NOX2 expression within NeuN

+ cortical neurons (arrows,

Figure 5D-E, p < 0.01) when compared to Veh-treated r-mTBI mice. In summary, these findings demonstrate that delayed pharmacological blockade of the NHE1 protein reduces r-mTBI-mediated astrogliosis and microgliosis, as well as oxidative stress responses in neurons.

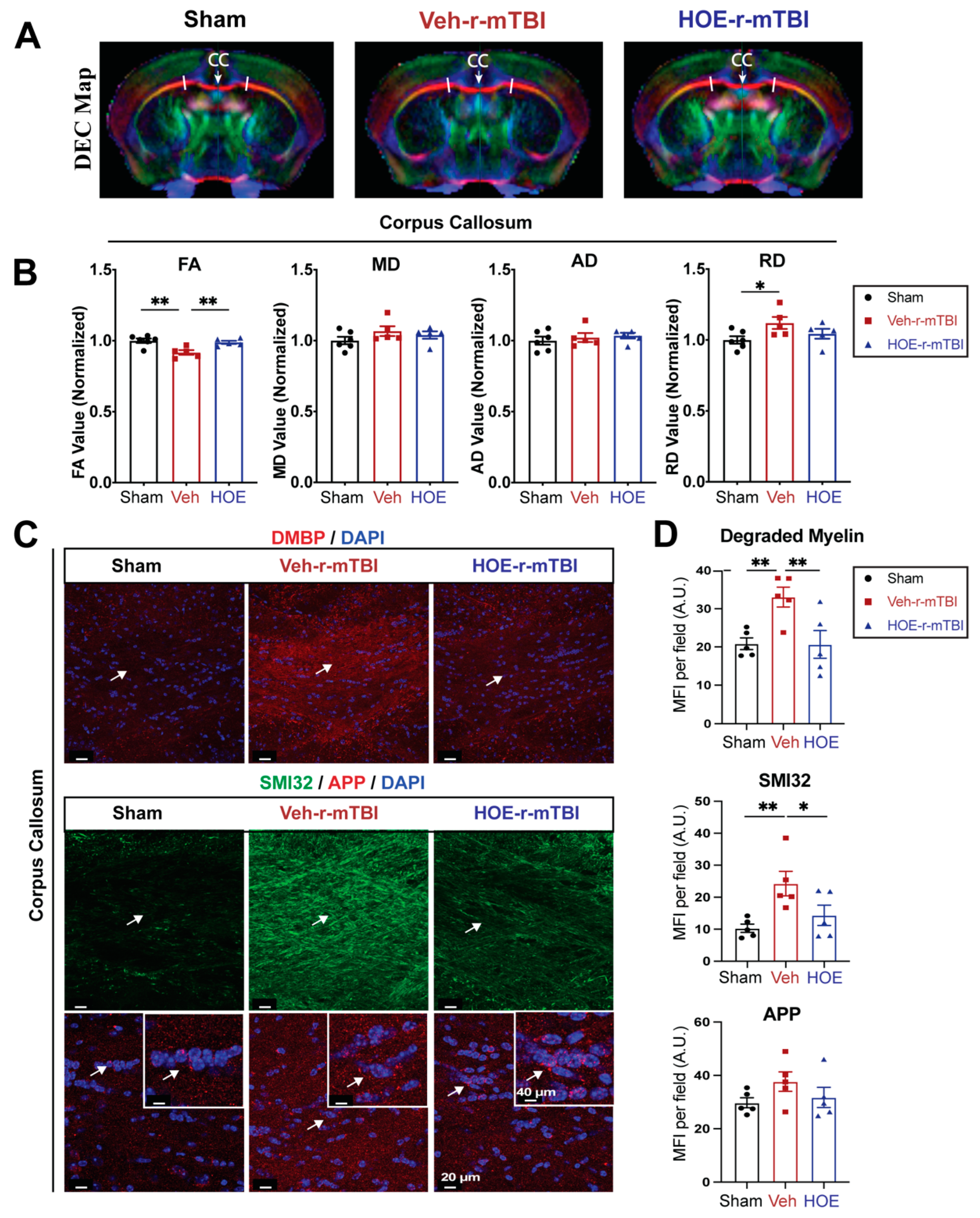

3.6. Pharmacological Inhibition of NHE1 with Inhibitor HOE642 Attenuated Axonal and White Matter Damage after r-mTBI

To gain a deeper understanding of r-mTBI-mediated white matter damage, MRI DTI studies were conducted in

ex vivo brains of sham, Veh-treated and HOE-treated r-mTBI mice at 60 dpi (

Figure 6A). The representative directionally encoded color (DEC) maps showed no noticeable lesions in the white matter tracts (arrow,

Figure 6A) among the three groups. The DTI metric FA is a measurement that characterizes the overall directionality of water diffusion within tissues, such as the white matter tracts in the brain [

20]. Lower values indicate loss of integrity that can occur from conditions that cause axonal damage or demyelination [

20]. Within the CC, Veh-treated mice exhibited a significant reduction in FA values (normalized to sham control animals) compared to sham mice (

Figure 6B, p < 0.01).

In contrast, the HOE-treated r-mTBI mice demonstrated preserved FA values (normalized to sham control animals) (

Figure 6B, p < 0.01) when compared to Veh-treated r-mTBI mice. RD is a DTI measurement that characterizes the diffusion of water molecules perpendicular to the principal axis of diffusion within tissues [

20]. In contrast to FA, RD values tend to increase in conditions such as demyelination or changes in axonal density [

20]. Interestingly, the DTI metric RD (normalized to sham) showed a significant increase (

Figure 6B, p < 0.05) in the Veh-treated r-mTBI cohort when compared to sham animals. Other normalized DTI metrics such as MD or AD showed no significant changes across the three groups. Within the hippocampal CA1 regions and external capsule, no significant differences were detected in normalized FA, AD, MD, or RD values between the three groups (Fig. S5). Within the internal capsule, no significant differences were detected in normalized FA, AD, or MD values between the three groups (Fig. S5). However, when compared to sham mice, the HOE-treated r-mTBI mice had a statistically significant increase in the DTI metric RD (normalized to sham) (Fig. S5).

To further support our DTI findings, we conducted immunostaining for damaged myelin with the degraded myelin basic protein (DMBP) antibody [

21], and for axonal damage with SMI32 (non-phosphorylated neurofilament) and APP in the CC (

Figure 6C) [

16,

22]. When compared to sham mice, Veh-treated r-mTBI mice had a significantly higher MFI of DMBP and SMI32 expression (arrows,

Figure 6C-D, p < 0.01) within the CC. In contrast, the HOE-treated r-mTBI mice exhibited a significant decrease in the MFI for both DMBP and SMI32, compared to the Veh-treated r-mTBI mice in the CC (arrows,

Figure 6C-D, p < 0.01 and p <0.05, respectfully). However, no differences were detected in the MFI of APP accumulation among all three groups (arrows,

Figure 6C-D). Taken together, our unbiased MRI DTI findings in addition to our immunostaining data demonstrate that pharmacological inhibition of the NHE1 protein reduced axonal damage and preserved white matter integrity in the CC following r-mTBI.

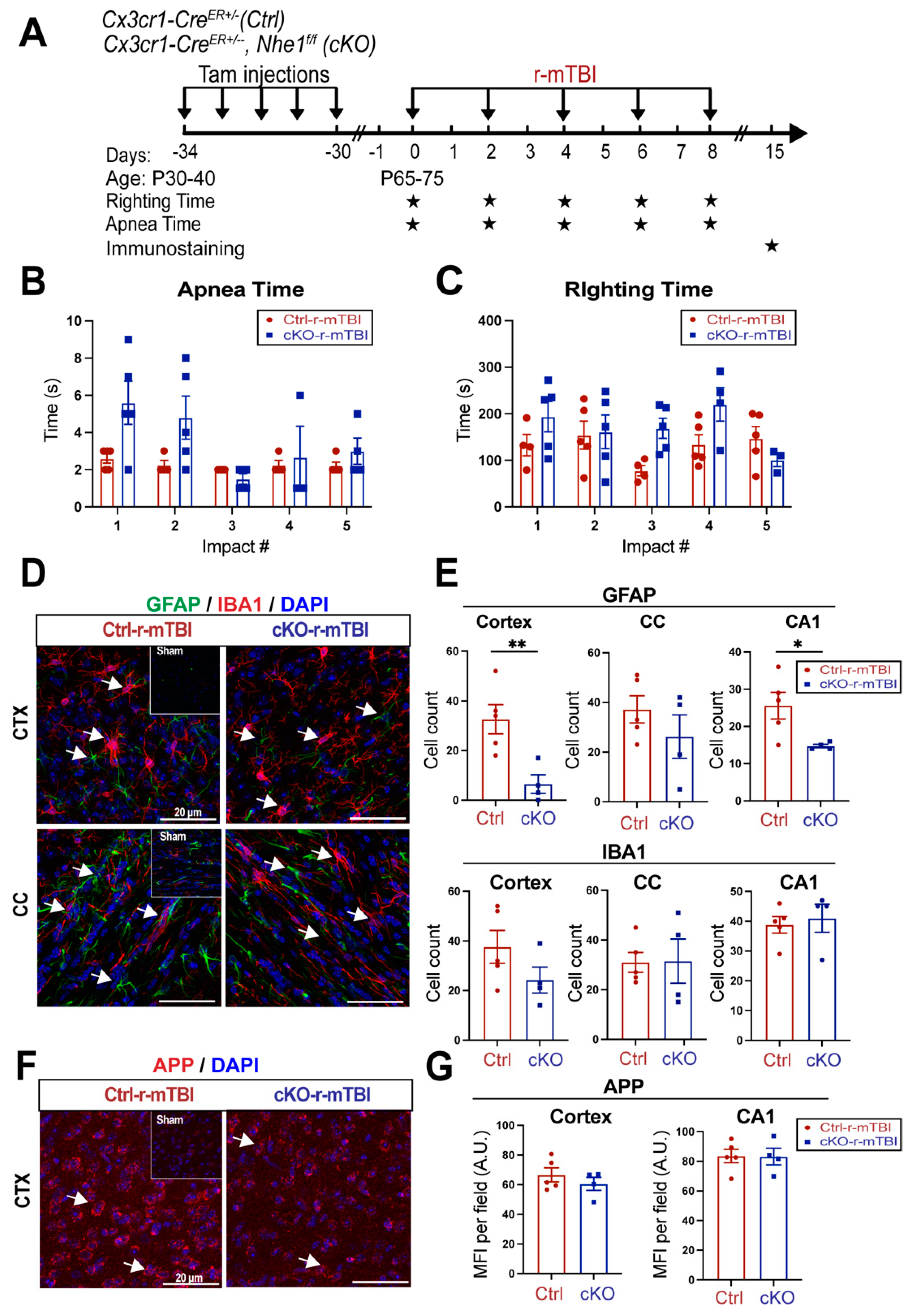

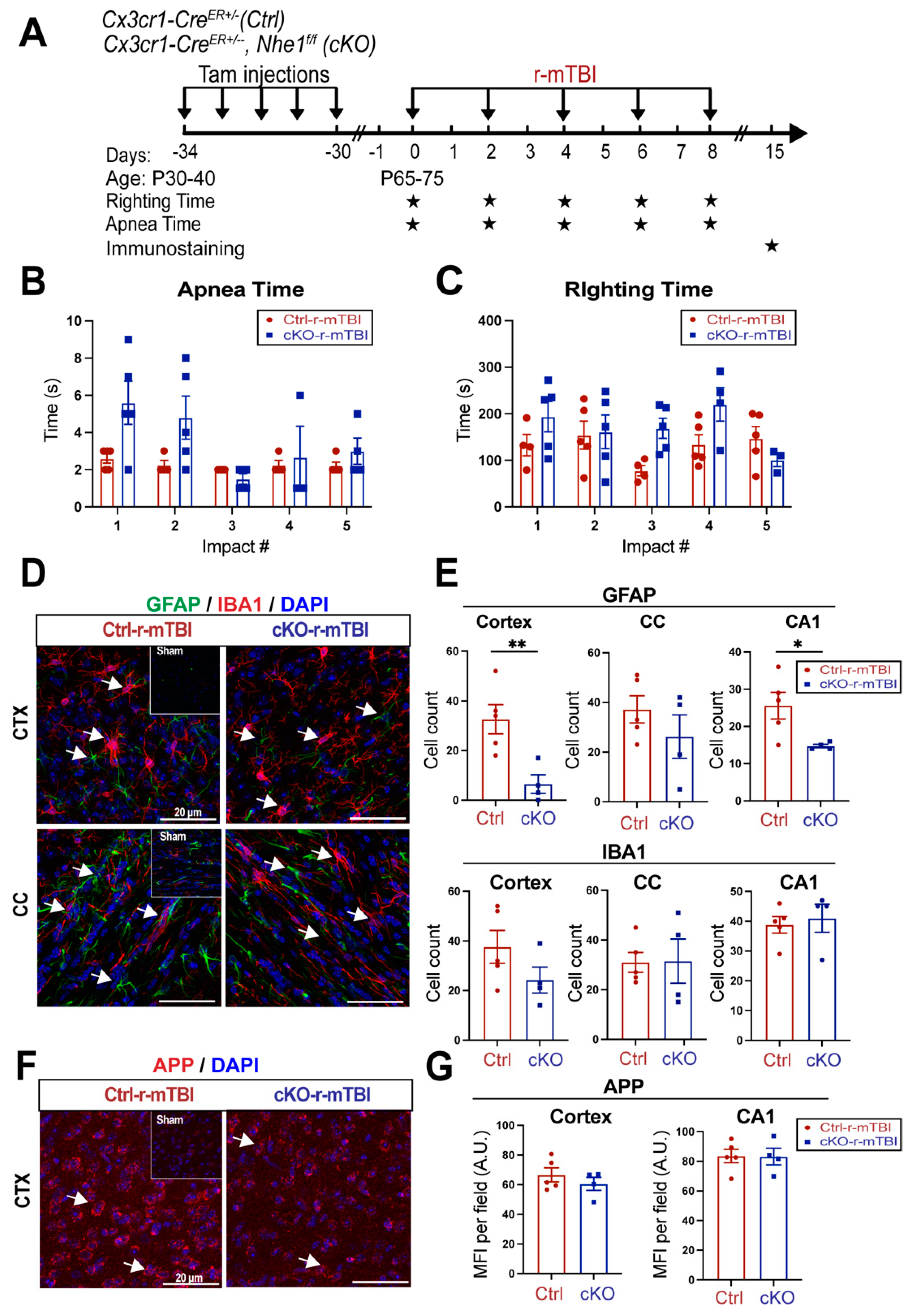

3.7. Selective Deletion of Microglial Nhe1 in Cx3cr1CreER+/-;Nhe1f/f Mice Reduced Astrogliosis after r-mTBI

Following TBI, pro-inflammatory microglia can become activated, leading the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and ROS that exacerbate neuronal injury [

9]. In our previous study, microglia-specific

Nhe1 cKO mice displayed an increase in the anti-inflammatory restorative microglia phenotype, which subsequently led to decreased GFAP

+ and IBA1

+ cell counts and improved white matter remyelination and oligodendrogenesis following an open-skull, moderate TBI model [

9]. We investigated here whether

Nhe1 cKO mice show resilience to r-mTBI-induced damage. r-mTBI triggered similar apnea and righting times in the Ctrl and cKO mice (

Figure 7A-B). Interestingly, the microglia-specific

Nhe1 cKO mice displayed significantly reduced GFAP

+ cell counts throughout the CTX and CA1 regions when compared to Ctrl mice at 15 dpi after r-mTBI (

Figure 7D-E, p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectfully). However, while overall cell counts of IBA1

+ cells appeared to be reduced in the CTX of

Nhe1 cKO mice, compared to Ctrl mice after r-mTBI (

Figure 7D-E), this difference lacked statistical significance. Immunostaining for APP accumulation did not show any significant differences between these two groups (Fig. F-G). These results imply that specific deletion of

Nhe1 in microglial cells has profound effects on attenuating astrogliosis after repetitive injuries, however, it was not effective in reducing the levels of activated microglia or APP accumulation accrued from damaged axons.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Clinical Significance of mTBI and Pathogenesis of White Matter Damage

It has been extensively documented that DAI is a characteristic pathology following mTBIs [

7,

23]. DAI not only manifests following mTBIs but across all spectrums of TBI severities [

7,

24]. This is mainly attributed to the susceptibility of axonal projections in the white matter tracts to shear after experiencing rapid acceleration or deceleration forces, causing microscopic damage to the brain’s axons [

7,

24]. Key features of DAI encompass axonal tearing, mitochondrial swelling, and the formation of axonal bulbs, subsequently leading to disruptions in neuronal transport [

4,

7,

24] and protein accumulation, often evidenced as the accumulation of APP [

7,

8]. APP accumulation has been consistently observed in cases of mild trauma and occurs quite rapidly after the inciting event, as evidenced by postmortem studies conducted on individuals who’ve experienced mTBIs and died from unrelated causes [

25]. In our study, we observed a significantly higher MFI of APP accumulation in both the CTX and hippocampal CA1 regions at 15 dpi (

Figure 2E). APP is transported via fast anterograde axon transport along microtubules and serves as a sensitive marker of acute axonal disruption in white matter during brain damage [

7,

8,

26]. In our study, at 60 dpi, we observed no significant difference between sham, Veh-treated and HOE-treated r-mTBI mice for APP accumulation in the CC. This prompted us to stain for SMI32, a well-validated marker that stains non-phosphorylated neurofilaments for detecting axonal damage [

16,

22]. Under physiological conditions, neurofilaments are transported through slow axonal transport [

27]. In pathological conditions that result in disrupted transport or abnormal phosphorylation, they accumulate within affected axons [

28], contributing to pathological processes. In the CC at 60 dpi, we observed a significantly increased MFI of SMI32 in the Veh-treated r-mTBI mice compared to sham (

Figure 6C-D) and a significant decrease in SMI32 MFI in the HOE-treated r-mTBI mice compared to Veh-treated mice (

Figure 6C-D). Taken together, these results indicate that HOE administration did reduce r-mTBI induced DAI by the chronic timepoint of 60 dpi.

Diagnosing mTBI-induced DAI in the clinical setting remains challenging, as traditional imaging methods, such as computed tomography (CT), are insufficient for detecting the specific microscopic changes found throughout the brain. However, advanced imaging modalities such as MRI DTI show more promise for diagnosing axonal injuries and detecting changes in white matter integrity [

29,

30]. The DEC color map illustrates the orientation of water diffusion, facilitating the detection of the alignment of white matter pathways [

29]. Furthermore, DTI enables the construction of tract bundles from ROIs and analysis of their diffusion metrics [

29,

30]. The primary diffusion metric in DTI, FA, serves as an indicator of white matter tract integrity [

29,

30,

31]. Clinical research studies on mTBI patients with chronic symptoms revealed that damage to axons in white matter pathways commonly results in reduced FA values [

32,

33]. In our study, we observed significant reductions in FA in the Veh-treated r-mTBI mice in the CC at 60 dpi, compared to sham mice (

Figure 6A-B), while HOE-treated r-mTBI mice displayed restored FA values (

Figure 6A-B). Additionally, compared to sham mice, Veh-treated mice also exhibited a significant increase in RD (

Figure 6A-B), suggesting increased demyelination from r-mTBI induction in these animals [

20]. These findings imply reduced white matter integrity in the Veh-treated r-mTBI mice compared to HOE-treated mice. In addition, within the internal capsule, when compared to sham animals, HOE-treated r-mTBI animals were observed to have higher RD values as well (

Figure S5). This also indicates that HOE-treated animals had higher levels of demyelination when compared to sham, as HOE-treated animals also underwent r-mTBI [

20]. Our findings were further validated by a significantly higher MFI of DMBP (

Figure 6C), a marker for abnormal oligodendrocyte processes found within demyelinating areas [

21] in the Veh-treated mice. Collectively, our findings suggest that post-r-mTBI administration of the NHE1 inhibitor, HOE642, reduces axonal damage and improves white matter integrity. Moreover, these findings suggest promising future applications of MRI DTI in facilitating clinical diagnoses for patients with mTBIs.

4.2. TBI-Induced Brain pH Dysregulation and NHE1 Upregulation

Findings from recent decades have firmly established post-traumatic cerebral acidosis as a hallmark of secondary injury following TBI [

34,

35]. Brain acidosis, characterized by an increase of brain lactate/pyruvate ratio, has been shown to be associated with worsened outcomes in acute severe TBI patients [

36]. pH dysregulation, both intracellular and extracellular, have been detected after moderate-TBIs [

37]. While the heterogeneity of brain injuries may influence the precise mechanisms and clinical implications of this process, it is widely acknowledged that increased extracellular levels of pCO2, protons, and lactate correspond to slower recovery [

38] as well as an elevated risk of poorer outcomes and mortality [

39,

40,

41]. This consensus is evident in the rigorous clinical regulation of ventilation and pO2/pCO2 pressures after severe brain injury [

42]. Additionally, extracellular acidic conditions following TBI are believed to contribute to the accumulation of tau and amyloid-β peptide aggregates observed in chronic traumatic encephalopathy [

43,

44]. This evidence indicates that mitigating the pathological H

+ homeostasis dysregulation as a potential approach for modulating post-mTBI pathogenesis.

At the cellular level, the decrease in intracellular and extracellular pH is associated with distorted metabolism and upregulated production of ROS, which can damage cell membranes and impair critical cellular functions [

37]. Numerous mediators of this pathogenesis are sensitive to pH, such as the activation of NOX activity and the production of superoxide ROS production under acidic conditions [

11]. In our study, we observed consecutive mTBIs-induced increases in NHE1 immunoreactivity in cortical neurons, as well as in activated astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia in the CC (

Figure 3C). This upregulation of NHE1 may stimulate H

+ efflux in response to elevated intracellular proton and lactate levels after brain injury. Consequently, the activation of proton extrusion proteins like NHE1 is crucial for maintaining the optimal pH

i for sustained NOX activation, leading to ROS production and oxidative damage following brain injuries [

4,

9] and allowing NOX-driven inflammation and cell damage to persist [

11,

16]. This was supported by our observation of increased neuronal expression of p-p47, the initiating component of the NOX2 complex activation, in the Veh-treated r-mTBI animals (

Figure 5D). Other proteins involved in H

+ efflux, such as the voltage-gated H

+ channel (Hv1) [

45,

46] and the ATPase H

+ [

47], both maintaining intracellular pH

i in microglial cells through proton extrusion, have similar functions to the NHE1 protein after brain injury [

9]. Interestingly, previous research also showed that Hv1 channel activation in microglia cells is required for NOX-mediated oxidative damage, and that inhibition of this specific channel in microglia reduced NOX activation and neuronal cell death as early as 24 hours after ischemic stroke [

46]. Collectively, our study demonstrates that pharmacological inhibition of NHE1 protein activity prevents the activation of p-p47 NOX2 subunit in neurons and mitigates oxidative damages induced by r-mTBI.

4.3. Protective Effects of Pharmacological Inhibition of NHE1 Protein

Treatment options for axonal damage induced by mTBIs are currently limited, as existing therapies primarily target addressing presenting signs and symptoms, encompassing somatic, cognitive, emotional, or behavioral aspects [

4]. There is a pressing need for new preclinical research to explore potential therapeutic targets for reducing oxidative damage and axonal injury following mTBI, thereby facilitating the translation of these therapies into clinical medicine. HOE642 (Cariporide) is a selective and potent inhibitor of the NHE1 protein, effectively blocking NHE1-mediated H

+ extrusion (along with blocked Na

+ influx) to acidify resting pH

i from approximately ~7.0 to ~6.8 in neurons, akin to reducing the extracellular pH (pH

e) from 7.2 to 7.0 [

11].

In vitro administration of HOE642 nearly abolished superoxide formation and neuronal death after NMDA-induced excitotoxicity [

11] or oxygen glucose deprivation/reoxygenation (OGD/REOX) [

48]. Similarly,

in vivo administration of HOE642 demonstrated potency in reducing NOX activation and superoxide production across various diseased models, including ischemic stroke [

49] and chronic cerebral hypoperfusion [

50]. Our study unveiled that post-r-mTBI administration of the NHE1 inhibitor, HOE642, for one week after five CCI-induced r-mTBIs significantly reduced p-p47 NOX2 expression in cortical neurons post-r-mTBI (

Figure 5D-E), indicating the crucial roles of NHE1-mediated pH

i regulation in oxidative damage and neuroinflammation following r-mTBI. Concurrently, we observed reduced axonal and white matter damages with diminished accumulation of SMI32 and DMBP (

Figure 6C-D), alongside increased FA values in the CC via MRI/DTI (

Figure 6A-B). This was accompanied by reduced microgliosis and astrogliosis (

Figure 5A-C), as well as improved locomotor and cognitive functional recovery (

Figure 4E-F) in the HOE642-treated mice post-r-mTBI at 60 dpi. These data indicate the potential of targeting NHE1 protein with pharmacological inhibitor HOE642 in providing therapeutic benefits to mTBI patients.

Additional mechanisms of NHE1-mediated pH

i homeostasis includes maintaining balancing aerobic glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) [

16,

51,

52]. Metabolic reprogramming from OXPHOS to glycolysis is associated with neurodegenerative phenotypes of microglia, while restoration of OXPHOS activity, with a reversal of glycolytic metabolism, mitigated the pathological changes associated with Alzheimer’s disease [

53]. Although the energy demand of astrocytes is predominantly met by glycolysis, their OXPHOS activity is required to provide crucial nutrient support to neurons by degrading fatty acids and maintaining lipid homeostasis [

54]. Defects in astrocytic OXPHOS induce lipid accumulation and reactive astrogliosis, subsequently suppressing oligodendrocyte-mediated myelin generation [

54]. Whether HOE642-mediated neuroprotective effects were mediated by metabolic reprogramming in neurons and glial cells remains to be further elucidated.

4.4. Lack of Reduction of Microgliosis in Microglial-Specific Nhe1 cKO Mice after r-mTBI

Neuroinflammation and activation of reactive astrocytes and microglia are the pathological hallmarks in concussion TBI models [

55,

56]. Activation of oxidative stress and proinflammatory signaling pathways, such as nuclear factor

κ-light chain-enhancer (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), have been reported to play a role in these events [

57,

58]. Compared to WT Ctrl,

Nhe1 cKO mice showed a pronounced reduction in GFAP

+ astrocyte cell counts but did not exhibit any changes in IBA1

+ microglia or APP accumulation in any of the three brain regions at 15 dpi following r-mTBI (

Figure 7). However, our recent report found a profound reduction in microglial activation in

Nhe1 cKO mice in an open-skull CCI contusion model [

9]. The causes for these different outcomes are not apparent. Possible reasons could be attributed to small sample size (n = 4 – 5) and/or less significant role of microglial NHE1 protein in r-mTBI pathogenesis (milder injury, chronic timepoint for collection), compared to other cell types (neuronal, astrocytes, etc). Moreover, in addition to cell count, a more detailed analysis of microglial activity should be further conducted.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, our study has demonstrated that r-mTBI induces neurological functional deficits, stimulates neuroinflammation, causes axonal damage, and upregulates the expression of the NHE1 protein. Furthermore, we observed that post-r-mTBI pharmacological inhibition of the NHE1 protein with HOE642 reduces neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, axonal damage, and preserves white matter integrity. Moreover, this treatment attenuates r-mTBI-induced locomotor and cognitive impairments. Thus, our findings identify the NHE1 protein as a potential therapeutic target for r-mTBIs.

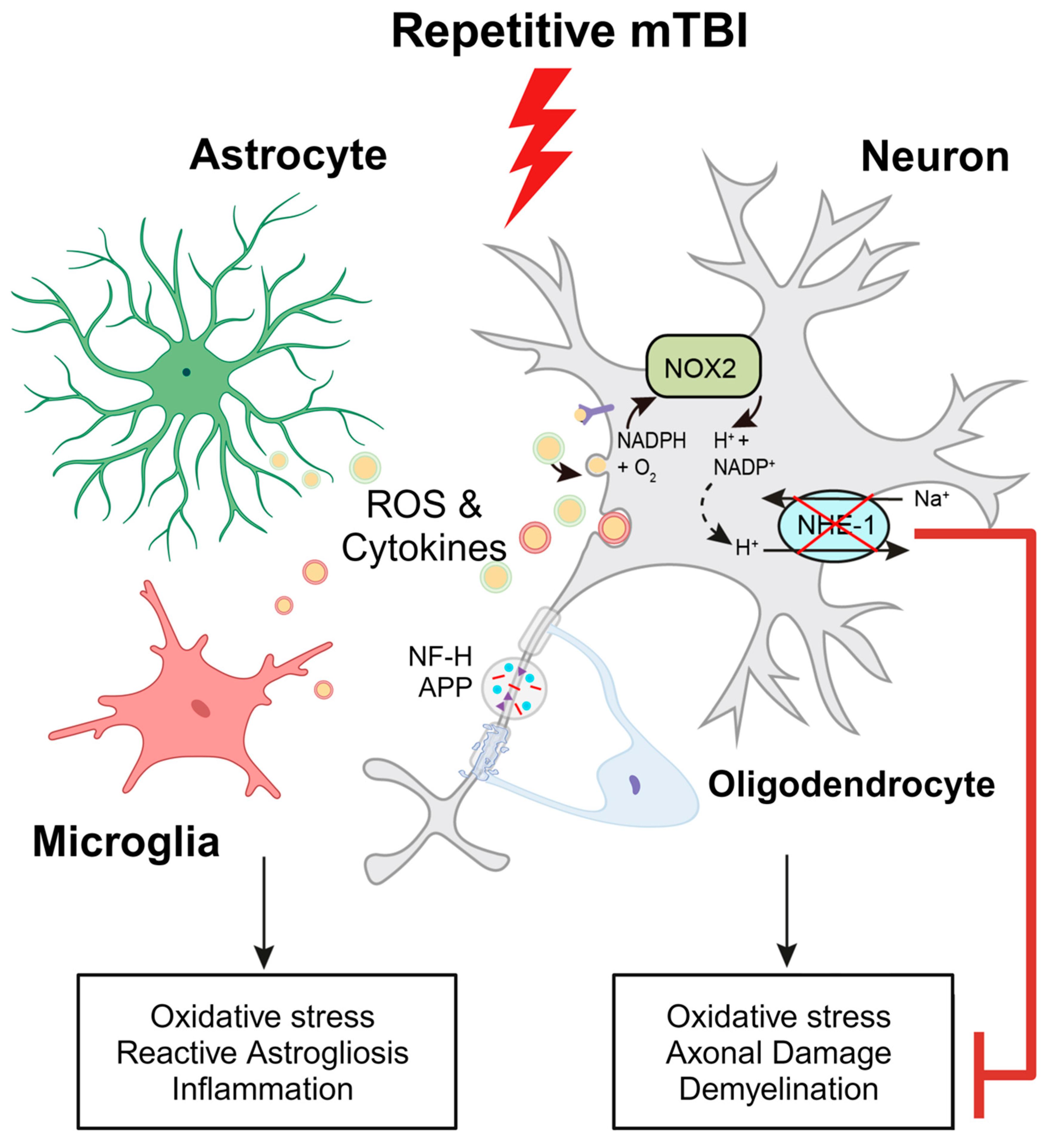

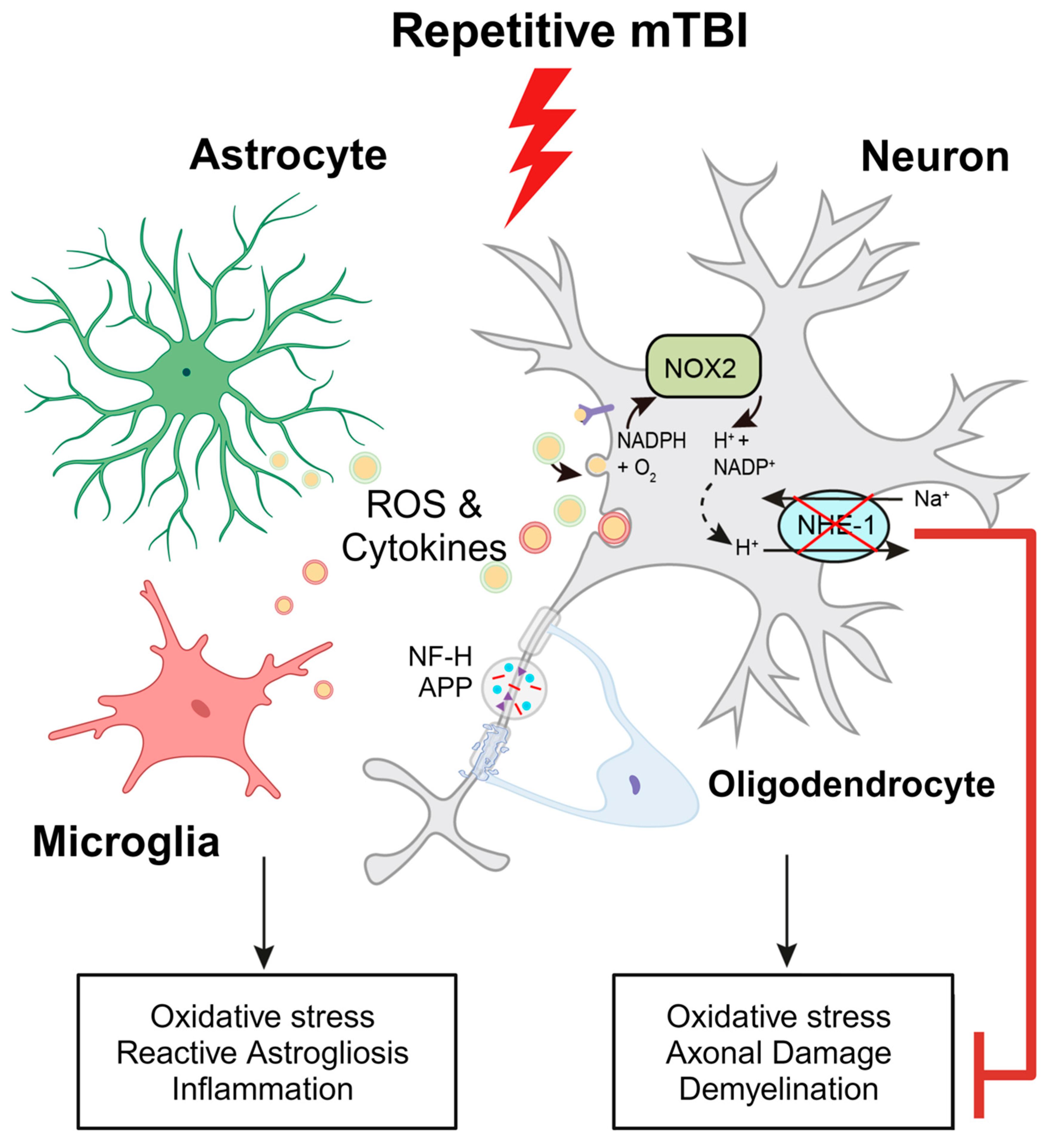

Figure 8.

Schematic illustration of r-mTBI-induced neuronal damage associated with the activation of NOX2 and NHE1. R-mTBI leads to the upregulation of NHE1 protein in neurons and multiple cell types. The coupling of NHE1 with NOX2 results in oxidative-stress induced neuroinflammation and white matter damage following r-mTBI. Pharmacological inhibition of NHE1 not only decreases gliosis, oxidative stress, and axonal injury, but also improves locomotor and cognitive functional recovery. Overall, these findings suggest that blocking NHE1 activity inhibits the response of reactive astrocytes and inflammatory microglia, promotes neuroprotection, and enhances white matter integrity, thereby expediting the recovery of neurological function following r-mTBI. This figure was created with Biorender.com and Adobe Illustrator software (Adobe Inc., Mountain View, CA USA). Abbreviations: APP, Amyloid Precursor Protein; NFL-H, Neurofilament Heavy Chain; NHE1, Sodium-Hydrogen Exchanger 1; NOX2, NADPH Oxidase; ROS, Reactive Oxygen Species.

Figure 8.

Schematic illustration of r-mTBI-induced neuronal damage associated with the activation of NOX2 and NHE1. R-mTBI leads to the upregulation of NHE1 protein in neurons and multiple cell types. The coupling of NHE1 with NOX2 results in oxidative-stress induced neuroinflammation and white matter damage following r-mTBI. Pharmacological inhibition of NHE1 not only decreases gliosis, oxidative stress, and axonal injury, but also improves locomotor and cognitive functional recovery. Overall, these findings suggest that blocking NHE1 activity inhibits the response of reactive astrocytes and inflammatory microglia, promotes neuroprotection, and enhances white matter integrity, thereby expediting the recovery of neurological function following r-mTBI. This figure was created with Biorender.com and Adobe Illustrator software (Adobe Inc., Mountain View, CA USA). Abbreviations: APP, Amyloid Precursor Protein; NFL-H, Neurofilament Heavy Chain; NHE1, Sodium-Hydrogen Exchanger 1; NOX2, NADPH Oxidase; ROS, Reactive Oxygen Species.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

John P. Bielanin: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. Visualization, Project administration. Shamseldin A. H. Metwally: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. Visualization. Helena C. M. Oft: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – review and editing. Satya S. Paruchuri: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Lin Lin: Investigation, Formal analysis. Okan Capuk: Investigation. Nicholas D. Pennock: Investigation. Shanshan Song: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing, Supervision, Project administration. Dandan Sun: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding Acquisition.

Funding

This study was funded by the Veterans Affairs Merit Awards I01 BX004625 (Sun) and I01 BX006372-01 (Sun), and the Career Research Scientist award IK6BX005647 (Sun). We would like to the thank the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine for their fellowship support for J.P.B via the Dean’s Year-Off Research Fellowship.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pittsburgh (protocol number: 21089835, date of approval: 7/17/2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest pertaining to this work.

References

- Bagalman, E. Heath Care for Veterans: Traumatic Brain Injury Congressional Research Service. 2015.

- Silverberg, N.D.; Iaccarino, M.A.; Panenka, W.J.; Iverson, G.L.; McCulloch, K.L.; Dams-O’Connor, K.; Reed, N.; McCrea, M.; American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine Brain Injury Interdisciplinary Special Interest Group Mild, T. B.I.T.F. Management of Concussion and Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: A Synthesis of Practice Guidelines. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2020, 101, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zetterberg, H.; Winblad, B.; Bernick, C.; Yaffe, K.; Majdan, M.; Johansson, G.; Newcombe, V.; Nyberg, L.; Sharp, D.; Tenovuo, O.; et al. Head trauma in sports - clinical characteristics, epidemiology and biomarkers. J Intern Med 2019, 285, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bielanin, J.P.; Metwally, S.A.H.; Paruchuri, S.S.; Sun, D. An overview of mild traumatic brain injuries and emerging therapeutic targets. Neurochemistry International 2024, 172, 105655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, W.T.; Starling, A.J. Concussion Evaluation and Management. Med Clin North Am 2019, 103, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polinder, S.; Cnossen, M.C.; Real, R.G.L.; Covic, A.; Gorbunova, A.; Voormolen, D.C.; Master, C.L.; Haagsma, J.A.; Diaz-Arrastia, R.; von Steinbuechel, N. A Multidimensional Approach to Post-concussion Symptoms in Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Front Neurol 2018, 9, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehily, B.; Fitzgerald, M. Repeated Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: Potential Mechanisms of Damage. Cell Transplant 2017, 26, 1131–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, M.; Frati, A.; Santoro, A.; Frati, P.; Fineschi, V.; Pesce, A. Diffuse Axonal Injury: Clinical Prognostic Factors, Molecular Experimental Models and the Impact of the Trauma Related Oxidative Stress. An Extensive Review Concerning Milestones and Advances. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.; Hasan, M.N.; Yu, L.; Paruchuri, S.S.; Bielanin, J.P.; Metwally, S.; Oft, H.C.M.; Fischer, S.G.; Fiesler, V.M.; Sen, T.; et al. Microglial-oligodendrocyte interactions in myelination and neurological function recovery after traumatic brain injury. J Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.; Wang, S.; Pigott, V.M.; Jiang, T.; Foley, L.M.; Mishra, A.; Nayak, R.; Zhu, W.; Begum, G.; Shi, Y.; et al. Selective role of Na(+) /H(+) exchanger in Cx3cr1(+) microglial activation, white matter demyelination, and post-stroke function recovery. Glia 2018, 66, 2279–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.I.; Brennan-Minnella, A.M.; Won, S.J.; Shen, Y.; Hefner, C.; Shi, Y.; Sun, D.; Swanson, R.A. Intracellular pH reduction prevents excitotoxic and ischemic neuronal death by inhibiting NADPH oxidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, E4362–4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Collier, J.M.; Capuk, O.; Jin, S.; Sun, M.; Mondal, S.K.; Whiteside, T.L.; Stolz, D.B.; et al. NOX activation in reactive astrocytes regulates astrocytic LCN2 expression and neurodegeneration. Cell Death Dis 2022, 13, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Percie du Sert, N.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. Experimental Physiology 2020, 105, 1459–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouzon, B.; Chaytow, H.; Crynen, G.; Bachmeier, C.; Stewart, J.; Mullan, M.; Stewart, W.; Crawford, F. Repetitive mild traumatic brain injury in a mouse model produces learning and memory deficits accompanied by histological changes. Journal of Neurotrauma 2012, 29, 2761–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraeuter, A.K.; Guest, P.C.; Sarnyai, Z. The Y-Maze for Assessment of Spatial Working and Reference Memory in Mice. Methods Mol Biol 2019, 1916, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.; Yu, L.; Hasan, M.N.; Paruchuri, S.S.; Mullett, S.J.; Sullivan, M.L.G.; Fiesler, V.M.; Young, C.B.; Stolz, D.B.; Wendell, S.G.; et al. Elevated microglial oxidative phosphorylation and phagocytosis stimulate post-stroke brain remodeling and cognitive function recovery in mice. Commun Biol 2022, 5, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metwally, S.A.H.; Paruchuri, S.S.; Yu, L.; Capuk, O.; Pennock, N.; Sun, D.; Song, S. Pharmacological Inhibition of NHE1 Protein Increases White Matter Resilience and Neurofunctional Recovery after Ischemic Stroke. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolte, S.; Cordelieres, F.P. A guided tour into subcellular colocalization analysis in light microscopy. Journal of microscopy 2006, 224, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, R.; Geng, X.; Li, F.; Ding, Y. NOX Activation by Subunit Interaction and Underlying Mechanisms in Disease. Front Cell Neurosci 2016, 10, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeramuthu, V.; Narayanan, V.; Kuo, T.L.; Delano-Wood, L.; Chinna, K.; Bondi, M.W.; Waran, V.; Ganesan, D.; Ramli, N. Diffusion Tensor Imaging Parameters in Mild Traumatic Brain Injury and Its Correlation with Early Neuropsychological Impairment: A Longitudinal Study. Journal of Neurotrauma 2015, 32, 1497–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Sun, W.; McBride, J.J.; Cheng, J.X.; Shi, R. Acrolein induces myelin damage in mammalian spinal cord. J Neurochem 2011, 117, 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yandamuri, S.S.; Lane, T.E. Imaging Axonal Degeneration and Repair in Preclinical Animal Models of Multiple Sclerosis. Front Immunol 2016, 7, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigler, E.D. Neuroimaging biomarkers in mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI). Neuropsychol Rev 2013, 23, 169–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, V.E.; Stewart, W.; Smith, D.H. Axonal pathology in traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol 2013, 246, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blennow, K.; Hardy, J.; Zetterberg, H. The neuropathology and neurobiology of traumatic brain injury. Neuron 2012, 76, 886–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieg, J.L.; Leonard, A.V.; Turner, R.J.; Corrigan, F. Identifying the Phenotypes of Diffuse Axonal Injury Following Traumatic Brain Injury. Brain Sci 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, J.M.; Garcia, M.L. Neurofilament Phosphorylation during Development and Disease: Which Came First, the Phosphorylation or the Accumulation? J Amino Acids 2012, 2012, 382107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzold, A.; Gveric, D.; Groves, M.; Schmierer, K.; Grant, D.; Chapman, M.; Keir, G.; Cuzner, L.; Thompson, E.J. Phosphorylation and compactness of neurofilaments in multiple sclerosis: indicators of axonal pathology. Exp Neurol 2008, 213, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigler, E.D.; Abildskov, T.J.; Goodrich-Hunsaker, N.J.; Black, G.; Christensen, Z.P.; Huff, T.; Wood, D.M.; Hesselink, J.R.; Wilde, E.A.; Max, J.E. Structural Neuroimaging Findings in Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev 2016, 24, e42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niogi, S.N.; Mukherjee, P. Diffusion tensor imaging of mild traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2010, 25, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Shukla, D.K.; Armstrong, R.C.; Marion, C.M.; Radomski, K.L.; Selwyn, R.G.; Dardzinski, B.J. Repetitive Model of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Produces Cortical Abnormalities Detectable by Magnetic Resonance Diffusion Imaging, Histopathology, and Behavior. Journal of Neurotrauma 2017, 34, 1364–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglese, M.; Makani, S.; Johnson, G.; Cohen, B.A.; Silver, J.A.; Gonen, O.; Grossman, R.I. Diffuse axonal injury in mild traumatic brain injury: a diffusion tensor imaging study. J Neurosurg 2005, 103, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutgers, D.R.; Toulgoat, F.; Cazejust, J.; Fillard, P.; Lasjaunias, P.; Ducreux, D. White matter abnormalities in mild traumatic brain injury: a diffusion tensor imaging study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008, 29, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uryu, K.; Laurer, H.; McIntosh, T.; Pratico, D.; Martinez, D.; Leight, S.; Lee, V.M.; Trojanowski, J.Q. Repetitive mild brain trauma accelerates Abeta deposition, lipid peroxidation, and cognitive impairment in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer amyloidosis. J Neurosci 2002, 22, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hum, P.D.; Traystman, R.J. pH-associated Brain Injury in Cerebral Ischemia and Circulatory Arrest. Journal of Intensive Care Medicine 1996, 11, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timofeev, I.; Carpenter, K.L.; Nortje, J.; Al-Rawi, P.G.; O’Connell, M.T.; Czosnyka, M.; Smielewski, P.; Pickard, J.D.; Menon, D.K.; Kirkpatrick, P.J.; et al. Cerebral extracellular chemistry and outcome following traumatic brain injury: a microdialysis study of 223 patients. Brain 2011, 134, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritzel, R.M.; He, J.; Li, Y.; Cao, T.; Khan, N.; Shim, B.; Sabirzhanov, B.; Aubrecht, T.; Stoica, B.A.; Faden, A.I.; et al. Proton extrusion during oxidative burst in microglia exacerbates pathological acidosis following traumatic brain injury. Glia 2021, 69, 746–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmarou, A., Holdaway, R., Ward, J.D., Yoshida, K., Choi, S.C., Muizelaar, J.P., & Young, H.F. . Traumatic Brain Tissue Acidosis: Experimental and Clinical Studies. In A. Baethmann, O. Kempski, & L. Schürer (Eds.). Mechanisms of Secondary Brain Damage 1993, 160-164. [CrossRef]

- Clausen, T.; Khaldi, A.; Zauner, A.; Reinert, M.; Doppenberg, E.; Menzel, M.; Soukup, J.; Alves, O.L.; Bullock, M.R. Cerebral acid-base homeostasis after severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg 2005, 103, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellingson, B.M.; Yao, J.; Raymond, C.; Chakhoyan, A.; Khatibi, K.; Salamon, N.; Villablanca, J.P.; Wanner, I.; Real, C.R.; Laiwalla, A.; et al. pH-weighted molecular MRI in human traumatic brain injury (TBI) using amine proton chemical exchange saturation transfer echoplanar imaging (CEST EPI). Neuroimage Clin 2019, 22, 101736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timofeev, I.; Nortje, J.; Al-Rawi, P.G.; Hutchinson, P.J.; Gupta, A.K. Extracellular brain pH with or without hypoxia is a marker of profound metabolic derangement and increased mortality after traumatic brain injury. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism: official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 2013, 33, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asehnoune, K.; Roquilly, A.; Cinotti, R. Respiratory Management in Patients with Severe Brain Injury. Crit Care 2018, 22, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, C.; Ding, Y.; Long, X.; Li, W.; Ke, D.; Wang, Q.; Liu, R.; Wang, J.Z.; Zhang, H.; et al. Blockage of AEP attenuates TBI-induced tau hyperphosphorylation and cognitive impairments in rats. Aging (Albany NY) 2020, 12, 19421–19439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schutzmann, M.P.; Hasecke, F.; Bachmann, S.; Zielinski, M.; Hansch, S.; Schroder, G.F.; Zempel, H.; Hoyer, W. Endo-lysosomal Abeta concentration and pH trigger formation of Abeta oligomers that potently induce Tau missorting. Nature communications 2021, 12, 4634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Ritzel, R.M.; Wu, J. Functions and Mechanisms of the Voltage-Gated Proton Channel Hv1 in Brain and Spinal Cord Injury. Front Cell Neurosci 2021, 15, 662971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.J.; Wu, G.; Akhavan Sharif, M.R.; Baker, A.; Jia, Y.; Fahey, F.H.; Luo, H.R.; Feener, E.P.; Clapham, D.E. The voltage-gated proton channel Hv1 enhances brain damage from ischemic stroke. Nat Neurosci 2012, 15, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemeyer, N.; Hanft, K.M.; Akriditou, M.A.; Unger, N.; Park, E.S.; Stanley, E.R.; Staszewski, O.; Dimou, L.; Prinz, M. Microglia contribute to normal myelinogenesis and to oligodendrocyte progenitor maintenance during adulthood. Acta Neuropathol 2017, 134, 441–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Kintner, D.B.; Chanana, V.; Algharabli, J.; Chen, X.; Gao, Y.; Chen, J.; Ferrazzano, P.; Olson, J.K.; Sun, D. Activation of microglia depends on Na+/H+ exchange-mediated H+ homeostasis. J Neurosci 2010, 30, 15210–15220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Chanana, V.; Watters, J.J.; Ferrazzano, P.; Sun, D. Role of sodium/hydrogen exchanger isoform 1 in microglial activation and proinflammatory responses in ischemic brains. J Neurochem 2011, 119, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Bhuiyan, M.I.H.; Liu, R.; Song, S.; Begum, G.; Young, C.B.; Foley, L.M.; Chen, F.; Hitchens, T.K.; Cao, G.; et al. Attenuating vascular stenosis-induced astrogliosis preserves white matter integrity and cognitive function. J Neuroinflammation 2021, 18, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Kim, D.; Caldwell, M.; Sun, D. The role of Na(+)/h (+) exchanger isoform 1 in inflammatory responses: maintaining H(+) homeostasis of immune cells. Adv Exp Med Biol 2013, 961, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.N.; Luo, L.; Ding, D.; Song, S.; Bhuiyan, M.I.H.; Liu, R.; Foley, L.M.; Guan, X.; Kohanbash, G.; Hitchens, T.K.; et al. Blocking NHE1 stimulates glioma tumor immunity by restoring OXPHOS function of myeloid cells. Theranostics 2021, 11, 1295–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, S.H.; Kang, S.; Lee, W.; Choi, H.; Chung, S.; Kim, J.I.; Mook-Jung, I. A Breakdown in Metabolic Reprogramming Causes Microglia Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell Metab 2019, 30, 493–507 e496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mi, Y.; Qi, G.; Vitali, F.; Shang, Y.; Raikes, A.C.; Wang, T.; Jin, Y.; Brinton, R.D.; Gu, H.; Yin, F. Loss of fatty acid degradation by astrocytic mitochondria triggers neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. Nat Metab 2023, 5, 445–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obenaus, A.; Noarbe, B.P.; Lee, J.B.; Panchenko, P.E.; Noarbe, S.D.; Lee, Y.C.; Badaut, J. Progressive lifespan modifications in the corpus callosum following a single juvenile concussion in male mice monitored by diffusion MRI. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, K.D.; Seshadri, V.; Thompson, X.D.; Broshek, D.K.; Druzgal, J.; Massey, J.C.; Newman, B.; Reyes, J.; Simpson, S.R.; McCauley, K.S.; et al. Microglial activation persists beyond clinical recovery following sport concussion in collegiate athletes. Front Neurol 2023, 14, 1127708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mettang, M.; Reichel, S.N.; Lattke, M.; Palmer, A.; Abaei, A.; Rasche, V.; Huber-Lang, M.; Baumann, B.; Wirth, T. IKK2/NF-kappaB signaling protects neurons after traumatic brain injury. FASEB Journal 2018, 32, 1916–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morganti, J.M.; Goulding, D.S.; Van Eldik, L.J. Deletion of p38alpha MAPK in microglia blunts trauma-induced inflammatory responses in mice. J Neuroinflammation 2019, 16, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Experimental protocol and neurological function deficits induced by r-mTBI. A. Experimental protocol. C57BL/6J mice (2-3 months old, male) were randomly assigned to sham control or r-mTBI groups (repetitive injuries of a total of 5 impacts with an inter-concussion interval of 48h). B-C. Apnea and righting times for sham or r-mTBI mice after each impact. N = 9. D. Rotarod accelerating test in mice 1 day prior to r-mTBI induction as baseline and at 10-15 days post-first injury (dpi). N = 7 for sham group, N = 6 for r-mTBI group. E. Y-maze novel spatial recognition test in a separate cohort of mice at 40 dpi. N = 4. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05.

Figure 1.

Experimental protocol and neurological function deficits induced by r-mTBI. A. Experimental protocol. C57BL/6J mice (2-3 months old, male) were randomly assigned to sham control or r-mTBI groups (repetitive injuries of a total of 5 impacts with an inter-concussion interval of 48h). B-C. Apnea and righting times for sham or r-mTBI mice after each impact. N = 9. D. Rotarod accelerating test in mice 1 day prior to r-mTBI induction as baseline and at 10-15 days post-first injury (dpi). N = 7 for sham group, N = 6 for r-mTBI group. E. Y-maze novel spatial recognition test in a separate cohort of mice at 40 dpi. N = 4. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05.

Figure 2.

Robust astrogliosis and microgliosis induced by r-mTBI. A-B. Representative low magnification (4x) immunostaining images of GFAP and IBA1 in the distal cortex (D) or peri-lesion cortex (PL) from sham or r-mTBI C57BL/6J brains at 15 dpi. GFAP+ and IBA1+ mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) fold change was quantified. C-D. Representative confocal images (40x) and quantification of GFAP+ and IBA1+ MFI per field from cortex (CTX), corpus callosum (CC) and hippocampal CA1 regions at 15 dpi. E-F. Representative confocal images and MFI quantification per field for amyloid precursor protein (APP) in CTX and CA1 hippocampus at 15 dpi. N = 4 for sham group, N = 5 for r-mTBI group. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Arrows: GFAP+, IBA1+ or APP+ cells. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 2.

Robust astrogliosis and microgliosis induced by r-mTBI. A-B. Representative low magnification (4x) immunostaining images of GFAP and IBA1 in the distal cortex (D) or peri-lesion cortex (PL) from sham or r-mTBI C57BL/6J brains at 15 dpi. GFAP+ and IBA1+ mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) fold change was quantified. C-D. Representative confocal images (40x) and quantification of GFAP+ and IBA1+ MFI per field from cortex (CTX), corpus callosum (CC) and hippocampal CA1 regions at 15 dpi. E-F. Representative confocal images and MFI quantification per field for amyloid precursor protein (APP) in CTX and CA1 hippocampus at 15 dpi. N = 4 for sham group, N = 5 for r-mTBI group. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Arrows: GFAP+, IBA1+ or APP+ cells. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 3.

IMARIS 3D reconstruction in sham and r-mTBI brains. A. Representative confocal (40x) double immunostaining images for NHE1 protein colocalizing with GFAP+ astrocytes, IBA1+ microglia, MAP2+ neurons, or OLIG2+ oligodendrocytes in CTX or CC from sham or r-mTBI brains at 15 dpi. B. IMARIS 3D reconstruction images from the same dataset as in A. C. Quantification summary of NHE1+ puncta in GFAP+, IBA1+, and OLIG2+ cells, and MAP2+ filament lengths in sham or r-mTBI brains. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. N = 4 for sham group, N = 5 for r-mTBI group. Arrows: NHE1+ puncta in GFAP+, IBA1+, OLIG2+ cells and MAP2+ filaments. * p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 3.

IMARIS 3D reconstruction in sham and r-mTBI brains. A. Representative confocal (40x) double immunostaining images for NHE1 protein colocalizing with GFAP+ astrocytes, IBA1+ microglia, MAP2+ neurons, or OLIG2+ oligodendrocytes in CTX or CC from sham or r-mTBI brains at 15 dpi. B. IMARIS 3D reconstruction images from the same dataset as in A. C. Quantification summary of NHE1+ puncta in GFAP+, IBA1+, and OLIG2+ cells, and MAP2+ filament lengths in sham or r-mTBI brains. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. N = 4 for sham group, N = 5 for r-mTBI group. Arrows: NHE1+ puncta in GFAP+, IBA1+, OLIG2+ cells and MAP2+ filaments. * p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 4.

Efficacy of NHE1 inhibitor HOE642 on improving behavioral performance in r-mTBI mice. A. Experimental protocol. Veh (DMSO) or HOE642 (0.15 mg/kg body weight/day, b.i.d., 8h apart) was administered from 9-15 dpi in C57BL/6J mice (2-3 months old, male). B-C. Apnea and righting times. D. Rotarod accelerating test at baseline (1 day prior to r-mTBI or sham induction) and at 9-29 dpi. | ****p < 0.0001 (Sham vs Veh); | **p < 0.001 (Sham vs HOE). E. Y-maze spontaneous alternation test conducted at 32 dpi from the same cohort of mice as in D. F. Open field test conducted at 30 dpi from the same cohort of mice as in D. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. N = 6 for sham group, N = 13 for Veh-treated group, N = 13 for HOE-treated group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 4.

Efficacy of NHE1 inhibitor HOE642 on improving behavioral performance in r-mTBI mice. A. Experimental protocol. Veh (DMSO) or HOE642 (0.15 mg/kg body weight/day, b.i.d., 8h apart) was administered from 9-15 dpi in C57BL/6J mice (2-3 months old, male). B-C. Apnea and righting times. D. Rotarod accelerating test at baseline (1 day prior to r-mTBI or sham induction) and at 9-29 dpi. | ****p < 0.0001 (Sham vs Veh); | **p < 0.001 (Sham vs HOE). E. Y-maze spontaneous alternation test conducted at 32 dpi from the same cohort of mice as in D. F. Open field test conducted at 30 dpi from the same cohort of mice as in D. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. N = 6 for sham group, N = 13 for Veh-treated group, N = 13 for HOE-treated group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 5.

Efficacy of pharmacological blocking NHE1 protein on reducing gliosis and oxidative damage after r-mTBI. A. Representative confocal immunofluorescent images (40x) of GFAP+ and IBA1+ cells at 60 dpi in the CTX, CC, and hippocampal CA1 regions B-C. Representative confocal immunofluorescent and binary images (40x) used for the unbiased semi-automatic quantification of GFAP+ and IBA1+ cell counts at 60 dpi. N = 4 for sham group, N = 6 for Veh-treated r-mTBI group, N = 6 for HOE-treated r-mTBI group. D-E. Representative confocal immunofluorescent images (40x) and quantification of NOX2 expression in NeuN+ cells at 60 dpi. Insert: 2x zoomed from respective image where arrow is indicating. N = 5 for sham group, N = 5 for Veh-treated r-mTBI group, N = 5 for HOE-treated r-mTBI group. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Arrows: GFAP+ cells, IBA1+ cells or NOX2+ expression within NeuN+ cells. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 5.

Efficacy of pharmacological blocking NHE1 protein on reducing gliosis and oxidative damage after r-mTBI. A. Representative confocal immunofluorescent images (40x) of GFAP+ and IBA1+ cells at 60 dpi in the CTX, CC, and hippocampal CA1 regions B-C. Representative confocal immunofluorescent and binary images (40x) used for the unbiased semi-automatic quantification of GFAP+ and IBA1+ cell counts at 60 dpi. N = 4 for sham group, N = 6 for Veh-treated r-mTBI group, N = 6 for HOE-treated r-mTBI group. D-E. Representative confocal immunofluorescent images (40x) and quantification of NOX2 expression in NeuN+ cells at 60 dpi. Insert: 2x zoomed from respective image where arrow is indicating. N = 5 for sham group, N = 5 for Veh-treated r-mTBI group, N = 5 for HOE-treated r-mTBI group. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Arrows: GFAP+ cells, IBA1+ cells or NOX2+ expression within NeuN+ cells. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 6.

Changes of r-mTBI-induced axonal damage detected by MRI Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and immunostaining. A. Representative DTI diffusion encoded color (DEC) map of the ex vivo brains from sham, Veh-treated and HOE-treated r-mTBI mice at 60 dpi. B. Analysis of normalized fractional anisotropy (FA), mean diffusivity (MD), axial diffusivity (AD), and radial diffusivity (RD) values in the corpus callosum (CC) from the same cohort of mice in A. N = 6 for sham group, N = 5 for Veh-treated group, N = 5 HOE-treated group. C-D. Representative confocal immunofluorescent images (40x) and MFI quantification of degraded myelin basic protein (DMBP), SMI32 and APP at 60 dpi in the CC from the same cohort of mice as in A. Insert: 2x zoomed from respective image where arrow is indicating. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. N = 5 for sham group, N = 5 for Veh-treated group, N = 5 HOE-treated group. Arrows: CC location, DMBP, SMI32 and APP expression * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

Figure 6.

Changes of r-mTBI-induced axonal damage detected by MRI Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and immunostaining. A. Representative DTI diffusion encoded color (DEC) map of the ex vivo brains from sham, Veh-treated and HOE-treated r-mTBI mice at 60 dpi. B. Analysis of normalized fractional anisotropy (FA), mean diffusivity (MD), axial diffusivity (AD), and radial diffusivity (RD) values in the corpus callosum (CC) from the same cohort of mice in A. N = 6 for sham group, N = 5 for Veh-treated group, N = 5 HOE-treated group. C-D. Representative confocal immunofluorescent images (40x) and MFI quantification of degraded myelin basic protein (DMBP), SMI32 and APP at 60 dpi in the CC from the same cohort of mice as in A. Insert: 2x zoomed from respective image where arrow is indicating. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. N = 5 for sham group, N = 5 for Veh-treated group, N = 5 HOE-treated group. Arrows: CC location, DMBP, SMI32 and APP expression * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

Figure 7.

Selective deletion of microglial Nhe1 in Cx3cr1CreER+/-;Nhe1f/f mice reduces astrogliosis. A. Experimental protocol. Tamoxifen (Tam, 75 mg/kg body weight, 20 mg/ml in corn oil, i.p.) was administered in Ctrl (Cx3cr1CreER+/- mice) and Cx3cr1CreER+/-;Nhe1f/f (cKO mice) daily for 5 consecutive days. A 30-day waiting period was given for complete clearance of Tam and peripheral Cx3cr1+ monocyte turnover. Repetitive injuries of a total of 5 impacts with an inter-concussion interval of 48h were induced in both Ctrl and cKO mice. B-C. Apnea and righting times. D. Representative immunofluorescent images (40x) of GFAP+ and IBA1+ cells at 15 dpi. Insert: Sham mice from separate cohort perfused at 15 dpi. E. Unbiased semi-automatic quantification from binary images (not shown) of GFAP+ and IBA1+ cell counts from the CTX, CC and hippocampal CA1 regions at 15 dpi. F. Representative immunofluorescent images (40x) of APP staining in the CTX at 15 dpi. Insert: Sham mice from separate cohort perfused at 15 dpi. G. MFI quantification of APP expression in the CTX and hippocampal CA1 regions. Arrows: GFAP+, IBA1+ or APP expression. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. N = 5 for Ctrl group, N = 4 for cKO groups. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

Figure 7.

Selective deletion of microglial Nhe1 in Cx3cr1CreER+/-;Nhe1f/f mice reduces astrogliosis. A. Experimental protocol. Tamoxifen (Tam, 75 mg/kg body weight, 20 mg/ml in corn oil, i.p.) was administered in Ctrl (Cx3cr1CreER+/- mice) and Cx3cr1CreER+/-;Nhe1f/f (cKO mice) daily for 5 consecutive days. A 30-day waiting period was given for complete clearance of Tam and peripheral Cx3cr1+ monocyte turnover. Repetitive injuries of a total of 5 impacts with an inter-concussion interval of 48h were induced in both Ctrl and cKO mice. B-C. Apnea and righting times. D. Representative immunofluorescent images (40x) of GFAP+ and IBA1+ cells at 15 dpi. Insert: Sham mice from separate cohort perfused at 15 dpi. E. Unbiased semi-automatic quantification from binary images (not shown) of GFAP+ and IBA1+ cell counts from the CTX, CC and hippocampal CA1 regions at 15 dpi. F. Representative immunofluorescent images (40x) of APP staining in the CTX at 15 dpi. Insert: Sham mice from separate cohort perfused at 15 dpi. G. MFI quantification of APP expression in the CTX and hippocampal CA1 regions. Arrows: GFAP+, IBA1+ or APP expression. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. N = 5 for Ctrl group, N = 4 for cKO groups. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).