Submitted:

22 September 2025

Posted:

23 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology - Gap Analysis of Japanese Coastal Fisheries with MSC Standards from Past assessments

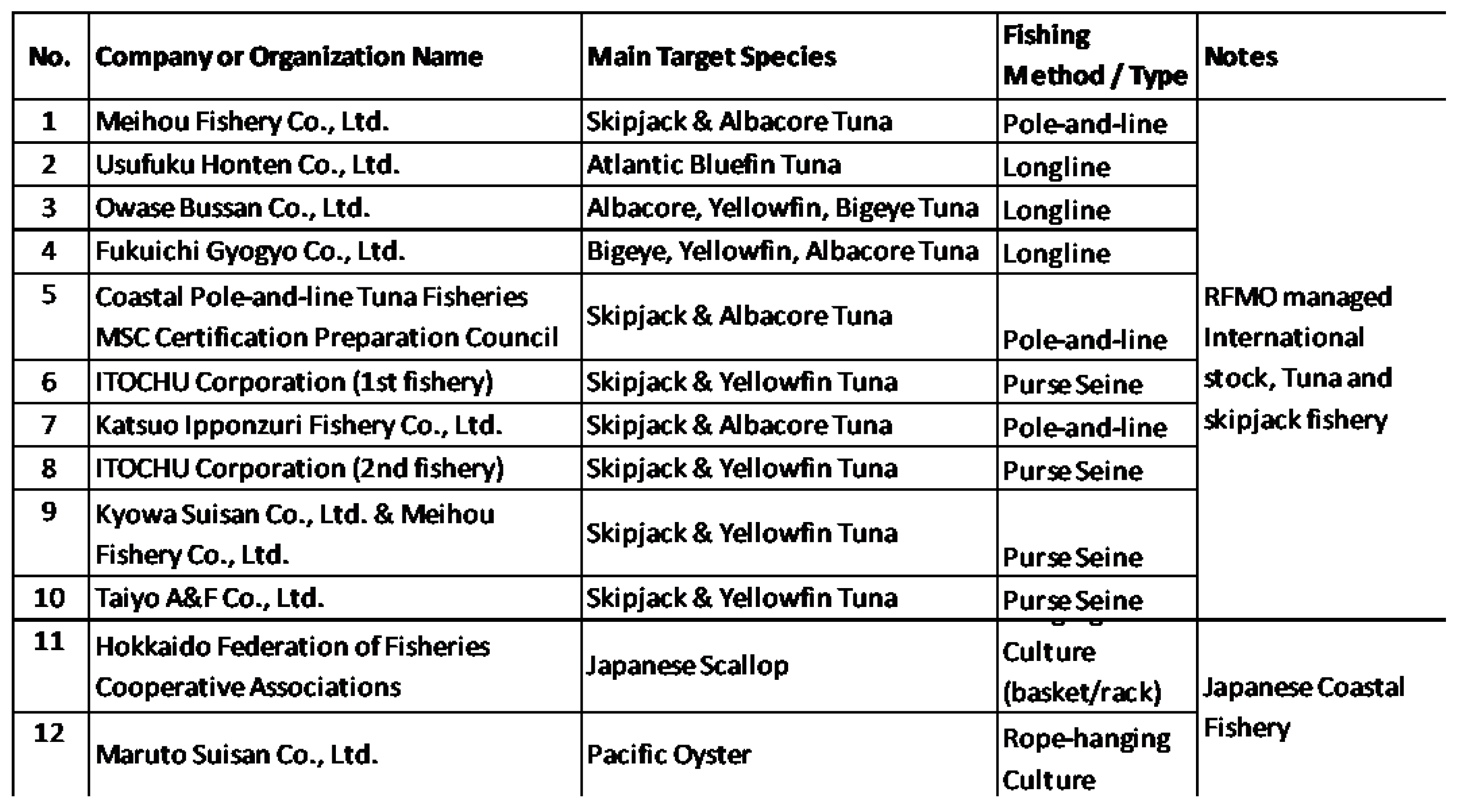

2.1. MSC Certification Assessment in Japan

|

2.2. Certification and Improvements Barriers

2.3. Domestic Perceptions and Certification

2.4. GAP Analysis Results

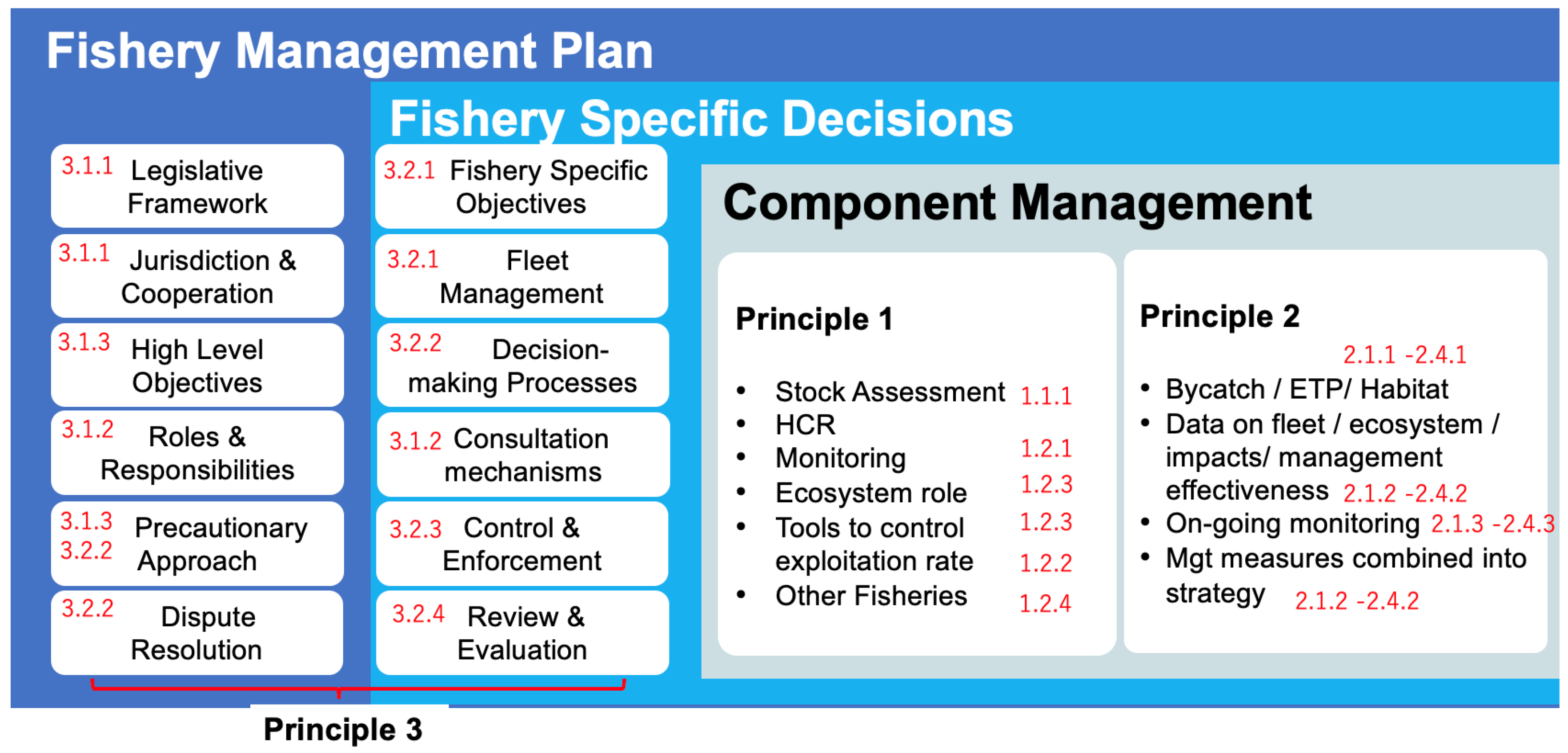

- Disparity between the provided scientific recommendation for sustainable management (stock assessment and suggested harvest strategies) and the fishery-specific management plan (Resource Management Plan).

- Lack or shortage of precautionary approach to management objective setting and its decision making.

- Lack of harvest strategies and rules coordination by stocks among different fishery units for widely distributed (transboundary) fishery resources.

- Internationally shared stock without management coordination (mostly with Korea and China).

- Lack of catch data reporting through logbook, which provides necessary information for stock assessment, such as species and catch size.

- Insufficient reporting and data collection on bycatch and endangered species.

- Limited consideration of ecosystem impacts from bycatch and endangered, threatened, and protected (ETP) species.

- Neglect of the carrying capacity of fishing grounds or habitats, especially in coastal aquaculture and sedentary species fisheries.

- Habitat modifications (e.g., seabed plowing, large artificial reef installations) conducted without adequate ecosystem considerations.

- Over-reliance on stock enhancement without robust scientific backing, potentially falling outside MSC scope.

- Insufficient attention to genetic effects on natural populations.

- Lack of measures for proper gear disposal and reduction of plastic waste.

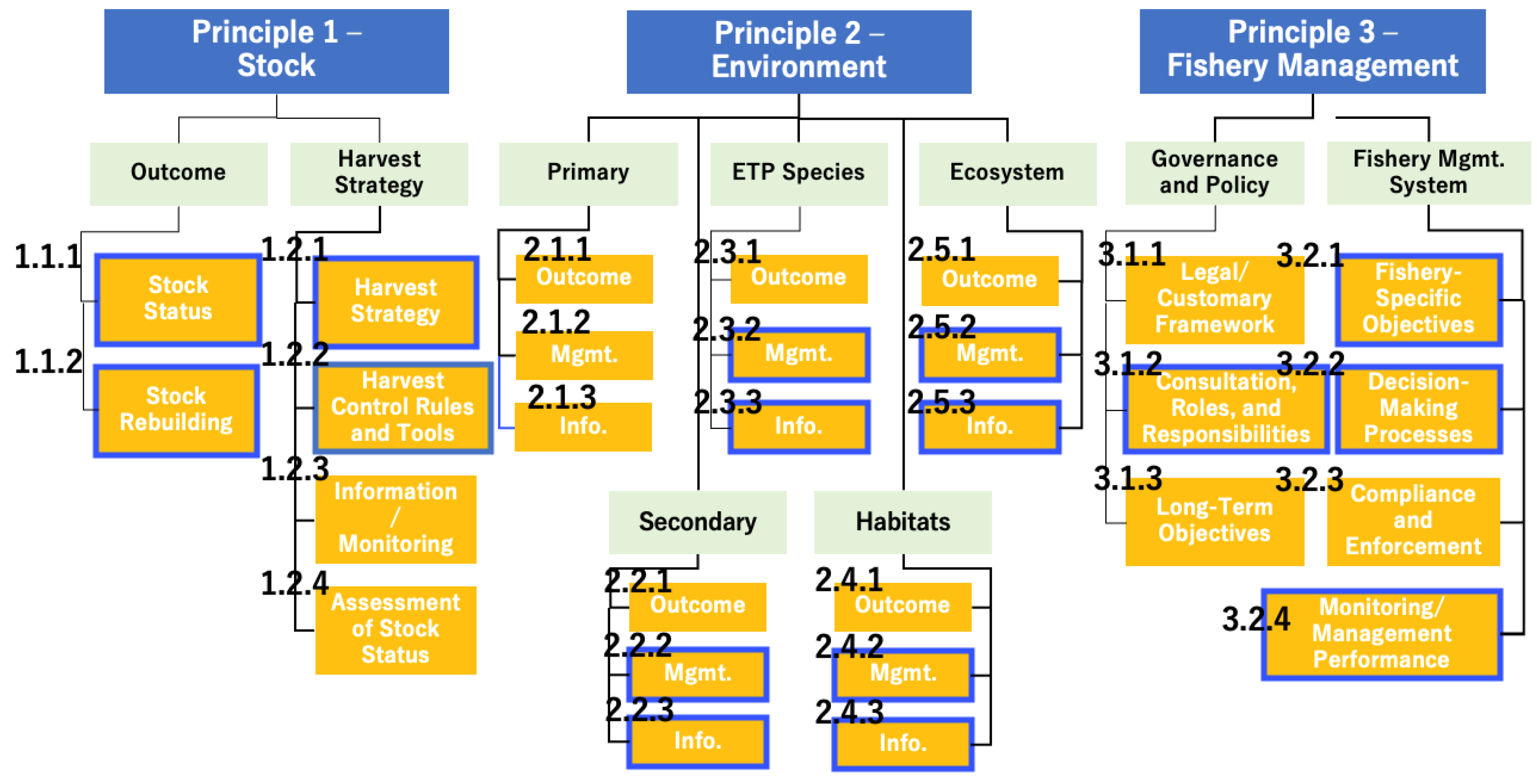

- Limited attention to the sustainability of bait fisheries.Figure 3. The 28 Performance indicators from 1.1.1 to 3.2.4 in the MSC Standard in a default tree. Performance Indicators (PIs) that are particularly weak in Japanese coastal fisheries are highlighted in blue frames.Figure 3. The 28 Performance indicators from 1.1.1 to 3.2.4 in the MSC Standard in a default tree. Performance Indicators (PIs) that are particularly weak in Japanese coastal fisheries are highlighted in blue frames.

- Lack of clear, stakeholder participation mechanism which provides consultation opportunity for all interested and affected parties to be involved.

- Lack of fishery-specific long-term goal that achieves Principle 1 and 2 objectives explicit within the fishery-specific management system.

-

Lack of decision-making processes:

- that result in measures and strategies to achieve the fishery-specific objectives.

- that respond to serious and important issues identified in relevant research, monitoring, evaluation and consultation, in a transparent, timely and adaptive manner and take account of the wider implications of decisions.

- with precautionary approach and the use of best available information.

- Lack of accountability and transparency (data and meeting records sharing upon requests)

- Lack of unclear evidence provision on Monitoring, Control and Surveillance system implementation and its enforceability with penalties or right incentives

- Lack of management effectiveness evaluation (Fishery Management Plans, management measures and subsidies, etc.).

3. Analysis - Why These Gaps Emerge: Institutional Factors (1.1.1, 1.1.2, 1.2.1, 3.1.3, 3.2.1)

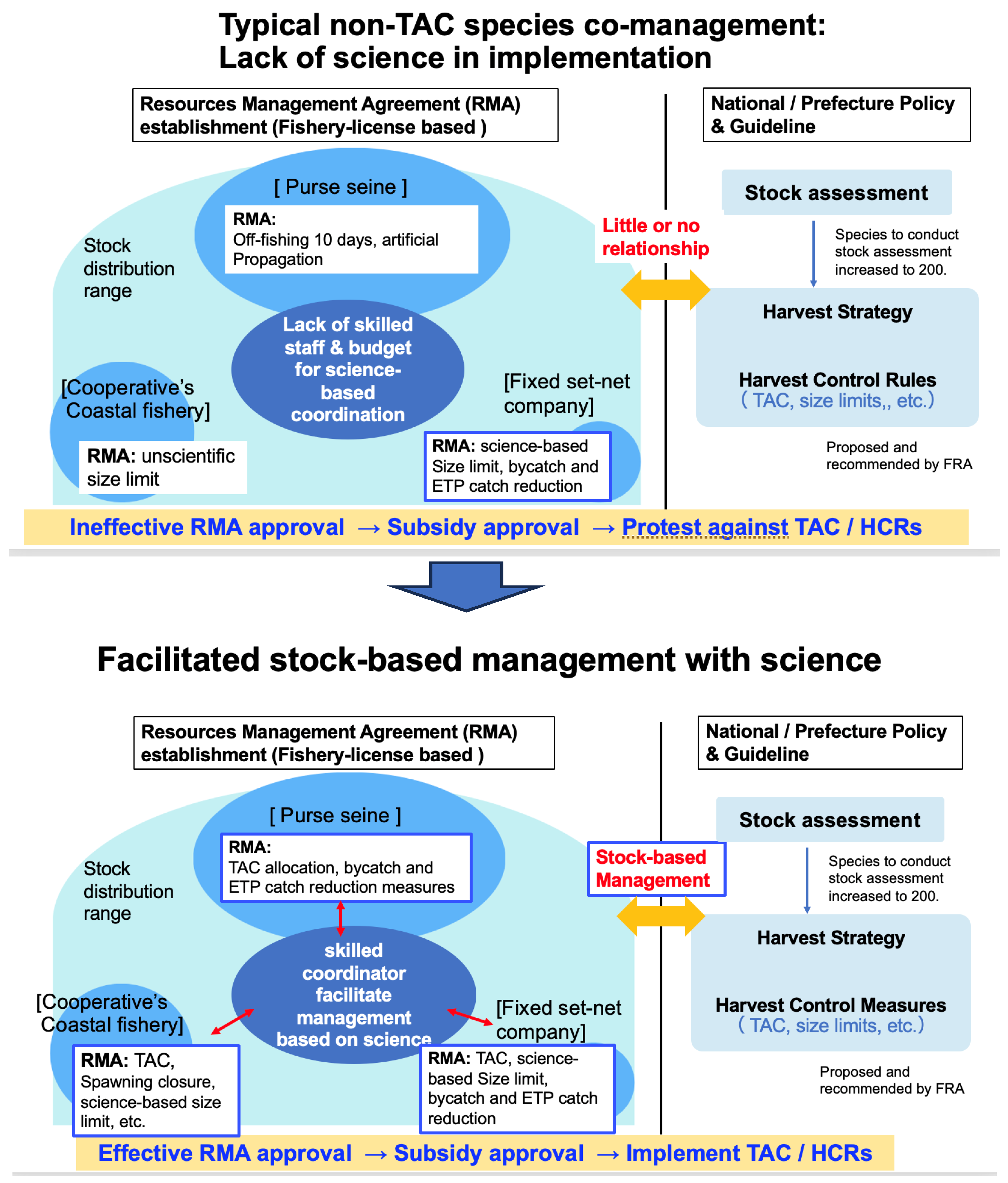

3.1. Japanese Co-Management and Resource Management Agreement (RMA)

3.2. Key Issues in Co-Management

3.3. RMA – Key Needs for Improvement

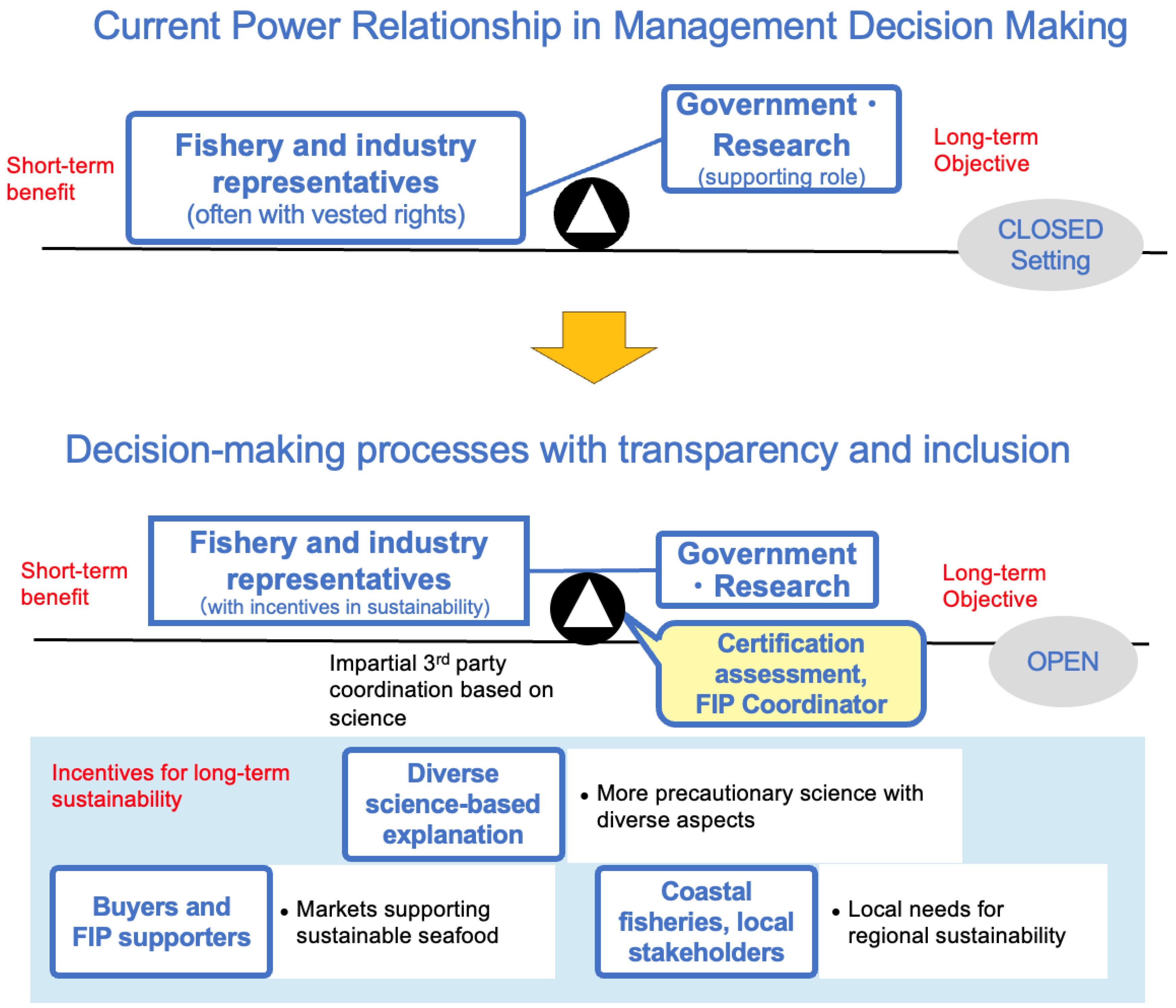

4. Discussion - How the Gaps Can Be Filled

4.1. Global Practices on Small-Scale, Multi-Species Fisheries

4.2. Use of FIPs and Certifications as External Review and Facilitation Tools

5. Conclusion and Recommendations

| Stakeholder Group | Recommended Actions |

|---|---|

| Government | - Establish clear consultation and decision-making guidelines for inclusive coastal management - Increase investment in scientific and coordination capacity for stock-based management and fishery management trainings. - Ensure institutional independence for science-based and ecosystem-based management - Support small-scale, multi-species fisheries through ecosystem monitoring and centralized data systems - Reform legal framework to strengthen co-management with clear roles and responsibilities. |

| Corporations | - Adopt sustainable sourcing policies - Provide funding for improvements via certification and FIPs - Review corporate impact on sourced products. |

| Academia | Conduct solution-oriented research to the pressing real-world issues in collaboration with industry and diverse stakeholders. |

| Fisheries | - Become responsible steward of ocean, which is expected in exchange of the endowed coastal fishing rights in Japan. - Increase transparency and accountability for fisheries operations. - Participate in consultation processes from diverse positions. - Actively seek to learn methodologies of resources management to implement rules and regulations. |

| Consumers | - Support sustainable seafood through purchasing choices |

| Certification Scheme Holders | - MEL: Introduce external reviews to improve assessment neutrality and transparency in all processes. - MSC and MEL: Design locally appropriate improvement pathways integrated with certification in collaboration with stakeholders. - Disseminate awareness that certifications and FIPs are tools to improve sustainability and requires the system to support improvement. |

| FIP Coordinators | - Facilitate science-based implementation with equitable stakeholder engagement - Share knowledge through user-friendly, centralized platforms for Japanese stakeholders |

| Financial Institutions & Funders | - Provide sustainability-linked financing - Support grassroots sustainability initiatives |

Funding

Acknowledgments

Glossary

References

- Agnew, D.J., Gutiérrez, N.L., Stern-Pirlot, A., Hoggarth, D.D., 2014. The MSC experience: Developing an operational certification standard and a market incentive to improve fishery sustainability. ICES Journal of Marine Science 71, 216–225. [CrossRef]

- Bellchambers, L.M., Gaughan, D.J., Wise, B.S., Jackson, G., Fletcher, W.J., 2016. Adopting Marine Stewardship Council certification of Western Australian fisheries at a jurisdictional level: The benefits and challenges. Fish Res 183, 609–616. [CrossRef]

- Blandon, A., Ishihara, H., 2021. Seafood certification schemes in Japan: Examples of challenges and opportunities from three Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) applicants. Mar Policy 123. [CrossRef]

- Cannon, J., Sousa, P., Katara, I., Veiga, P., Spear, B., Beveridge, D., Van Holt, T., 2018. Fishery improvement projects: Performance over the past decade. Mar Policy 97, 179–187. [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.W., 1973. The Economics of Overexploitation. Science (1979) 181, 630–634. [CrossRef]

- Crona, B., Käll, S., van Holt, T., 2019. Fishery Improvement Projects as a governance tool for fisheries sustainability: A global comparative analysis. PLoS One 14. [CrossRef]

- Jo Gascoigne, T.E.Y.T.C.D.V.P., 2023. Public Comment Draft report, Fukuichi Western and Central Pacific Ocean longline bigeye, yellowfin and albacore tuna fishery.

- FAO, 2024. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024: Blue Transformation in Action. Rome.

- FAO, 2009. The Guidelines for the Ecolabelling of Fish and Fishery Products from Marine Capture Fisheries.

- Fisheries Agency, 2021. Koremadeno Jisyuteki Na Kanrito Kongo, Shigen Kanri Kyotei heno Ikou, document 3-2-1. [WWW Document]. https://www.jfa.maff.go.jp/j/suisin/s_kouiki/setouti/attach/pdf/index-101.pdf. URL https://www.jfa.maff.go.jp/j/suisin/s_kouiki/setouti/attach/pdf/index-101.pdf (accessed 2.16.25).

- FRA, 2019. Marine fisheries stock assessment and evaluation for Japanese waters, 2019.

- FRA (Japan Fisheries Research and Education Agency), 2018. FRA News 56, Suisan shigen hyouka no genjou to korekara.

- Government of Western Australia, D. of F., 2016. Guideline for stakeholder engagement on aquatic resource management-related processes. Government Of Western Australia, Department of Fisheries, Western Australia, AU.

- Grafton, R.Q., Kompas, T., Hilborn, R.W., 2007. Economics of overexploitation revisited. Science (1979) 318, 1601. [CrossRef]

- Gulbrandsen, L.H., 2009. The emergence and effectiveness of the Marine Stewardship Council. Mar Policy 33, 654–660. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, N.L., Hilborn, R., Defeo, O., 2011. Leadership, social capital and incentives promote successful fisheries. Nature 470, 386–389. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, N.L., Valencia, S.R., Branch, T.A., Agnew, D.J., Baum, J.K., Bianchi, P.L., Cornejo-Donoso, J., Costello, C., Defeo, O., Essington, T.E., Hilborn, R., Hoggarth, D.D., Larsen, A.E., Ninnes, C., Sainsbury, K., Selden, R.L., Sistla, S., Smith, A.D.M., Stern-Pirlot, A., Teck, S.J., Thorson, J.T., Williams, N.E., 2012. Eco-Label Conveys Reliable Information on Fish Stock Health to Seafood Consumers. PLoS One 7, e43765. [CrossRef]

- Hakala, S., Watari, S., Uehara, S., Akatsuka, Y., Methot, R., Oozeki, Y., 2023. Governance and science implementation in fisheries management in Japan as it compares to the United States. Mar Policy 155. [CrossRef]

- Hardin, G., 1968. The Tragedy of the Commons. Science (1979) 162, 1243–1248. [CrossRef]

- Hønneland, G., 2020. Marine stewardship council (Msc) certification of arctic fisheries: Processes and outcomes. Arctic Review on Law and Politics 11. [CrossRef]

- JFA, 2018. Fisheries White Paper, Heisei 30, Suisan Hakusho Heisei 30 Nendo Ban 231p.

- Karr, K.A., Fujita, R., Carcamo, R., Epstein, L., Foley, J.R., Fraire-Cervantes, J.A., Gongora, M., Gonzalez-Cuellar, O.T., Granados-Dieseldorff, P., Guirjen, J., Weaver, A.H., Licón-González, H., Litsinger, E., Maaz, J., Mancao, R., Miller, V., Ortiz-Rodriguez, R., Plomozo-Lugo, T., Rodriguez-Harker, L.F., Rodríguez-Van Dyck, S., Stavrinaky, A., Villanueva-Aznar, C., Wade, B., Whittle, D., Kritzer, J.P., 2017. Integrating science-based co-management, partnerships, participatory processes and stewardship incentives to improve the performance of small-scale fisheries. Front Mar Sci 4. [CrossRef]

- Kleisner, K.M., Ojea, E., Battista, W., Burden, M., Cunningham, E., Fujita, R., Karr, K., Amorós, S., Mason, J., Rader, D., Rovegno, N., Thomas-Smyth, A., 2022. Identifying policy approaches to build social-ecological resilience in marine fisheries with differing capacities and contexts. ICES Journal of Marine Science 79, 552–572. [CrossRef]

- Levine, M., Thomas, J.B., Sanders, S., Berger, M.F., Gagern, A., 2020. 2020 Global Landscape Review of Fishery Improvement Projects About the authors.

- López-Ercilla, I., Rocha-Tejeda, L., Fulton, S., Espinosa-Romero, M.J., Torre, J., Fernández Rivera-Melo, F.J., 2024. Who pays for sustainability in the small-scale fisheries in the global south? Ecological Economics. [CrossRef]

- Makino, M., 2013. Nihon gyogyou no seido bunseki [Institutional Analysis of Japanese Fisheries]. Kouseisya kouseikaku.

- Makino, M., 2011. Fisheries Management in Japan. Fisheries Management in Japan: Its Institutional Features and Case Studies, Fish and Fisheries Series. [CrossRef]

- Makino, M., Matsuda, H., 2005. Co-management in Japanese coastal fisheries: Institutional features and transaction costs. Mar Policy 29, 441–450. [CrossRef]

- MEL, 2022. MEL Fisheries Certification: Conformity Assessment Criteria (Assessment Guidelines) Ver. 2.2.

- Melnychuk, M.C., Lees, S., Veiga, P., Rasal, J., Baker, N., Koerner, L., Hively, D., Kurota, H., de Moor, C.L., Pons, M., Mace, P.M., Parma, A.M., Mannini, A., Little, L.R., Bensbai, J., Muñoz Albero, A., Polidoro, B., Jardim, E., Hilborn, R., Longo, C., 2025. Comparing voluntary and government-mandated management measures for meeting sustainable fishing targets, in: Journal of Environmental Management. Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki Prefecture, 2024. Miyazaki Ken ni Okeru Iwashi Shirasu ni kansuru Shigen Kanri Kyoutei (Danish seine).

- MSC, 2024. MedPath Impact Report 2024.

- MSC, 2014. MSC Fisheries Certification Requirements and Guidance Version 2.0. 1 October 2014.

- MSC, n.d. Fishery Improvement Projects (FIPs) | Marine Stewardship Council [WWW Document]. URL https://www.msc.org/for-business/fisheries/fips (accessed 9.4.25).

- Nagasaki Prefecture, 2022. Shigen Kanri Kyoutei,Nagasaki Kennan Chiku for Mackerel, horse mackerel, sardine middle-size purse seine.

- Okamura, H., 2023. Towards sustainable use of fishery resources: maximum sustainable yield and biometrics.

- Orita, K., 2019. MSC ninshou to MEL ninshou no hikaku ni motozuku nihon no suisan ecolaberu seisaku no teigen [Proposed Fishery Ecolabeling policy based on the Comparison of MSC certification and MEL certification]. Tokyo.

- Ostrom, E., 1990. Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action.. Cambridge university press.

- Pérez-Ramírez, M., Phillips, B., Lluch-Belda, D., Lluch-Cota, S., 2012. Perspectives for implementing fisheries certification in developing countries. Mar Policy 36, 297–302. [CrossRef]

- Pomeroy, R.S., Berkes, F., 1997. Two to tango: the role of government in fisheries co-management. Pergamon Marine Policy 21, 465–480.

- Rasal, J., Melnychuk, M.C., Lejbowicz, A., Montero-Castaño, C., Ferber, S., Longo, C., 2024. Drivers of success, speed and performance in fisheries moving towards Marine Stewardship Council certification. Fish and Fisheries 25, 235–250. [CrossRef]

- SFP, n.d. FishSource [WWW Document]. URL https://www.fishsource.org/improvement-project (accessed 9.4.25).

- Southall, T., 2018. MSC FIP capacity building workshop training material.

- Swartz, W., S.L., S.U.R., & O.Y., 2017. Searching for market-based sustainability pathways: Challenges and opportunities for seafood certification programs in Japan. Mar Policy 76, 185–191.

- UNEP, 2009. Certification and sustainable fisheries.

- UNESCO-IOC, 2020. UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development 2021–2030: Implementation Plan (Version 2).0). Paris.

- United Nations, 2023. Making food systems work for people and planet UN Food Systems Summit +2 Report of the Secretary-General.

- Unknown, 2024. MEL Recertification report Fukushima Fisheries Cooperative mackerels purse seine fisheries. Tokyo.

- Unknown, 2022. MEL Certification Report Rishiri Atka mackerel gillnet fishery.

- Wakamatsu, H., Sakai, Y., 2021. Can the Japanese fisheries qualify for MSC certification? Mar Policy 134. [CrossRef]

- Washington, S., Ababouch, L., 2011. Private standards and certification in fisheries and aquaculture: current practice and emerging issues. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper 203.

- World Bank, 2013. Fish to 2030: Prospects for fisheries and aquaculture. Washington,DC.

- WWF, n.d. What are fishery improvement projects and how do they work? | Pages | WWF [WWW Document]. URL https://www.worldwildlife.org/pages/what-are-fishery-improvement-projects-and-how-do-they-work?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed 9.4.25).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).