Submitted:

29 August 2025

Posted:

01 September 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Menu Creation

Inconvenience Metric

Determination of Nova Categorization

Shelf Stability in Context of 7-Day Menu

Menu Cost and Leftover Food Calculations

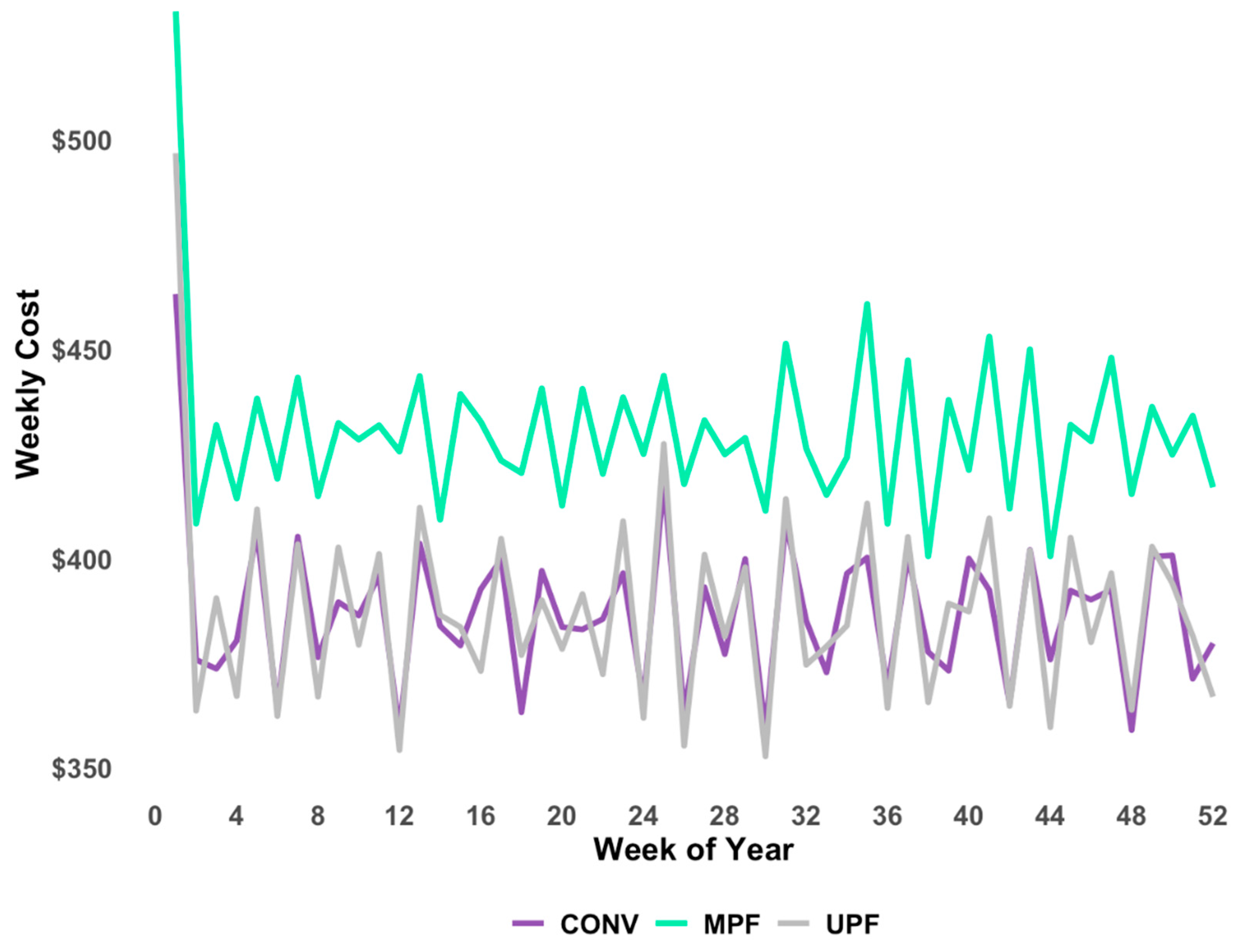

Annual Cost Analysis Using 52-Week Shopping Simulation

- 1)

- Daily Consumption Rates: The daily consumption rates were calculated by dividing the total quantity used for the 4-person household across the 7-day menu by 7. For example, the UPF menu required 8.71 containers of milk over the week, so the daily consumption rate was 1.24 containers per day (8.71/7=1.24). Ready-to-eat food items that are intended to be consumed upon purchase (e.g. a pre-made chicken wrap), were consumed immediately each week in the model.

- 2)

- Inventory Tracking: The model maintained a running inventory of food items, tracking both unopened containers and opened containers currently in use. When a container was opened, its shelf life was updated according to expiration timeframes of an opened container from the FoodKeeper App [31] and supplementary resources [32,33,34]. Proportion of items that remained in the inventory until their expiration date was counted as wasted value and removed.

- 3)

- Shopping Frequency: Weekly shopping trips were simulated, with purchases based on anticipated needs for the coming week while considering existing inventory levels. The model assumed consumers would purchase items only when current inventory levels were insufficient to meet the week’s requirements. When multiple containers were purchased, they were opened sequentially as consumption required, with each newly opened container's expiration timer reset to the opened shelf-life duration. Annual costs were calculated from all food purchased throughout the 52 weeks.

Determination of Nutrient Content

Determination of HEI-2015 Scores

Energy Density and Hyper-Palatable Foods

Statistical Analysis

Results

Menus and Energy from Ultra-Processed Foods

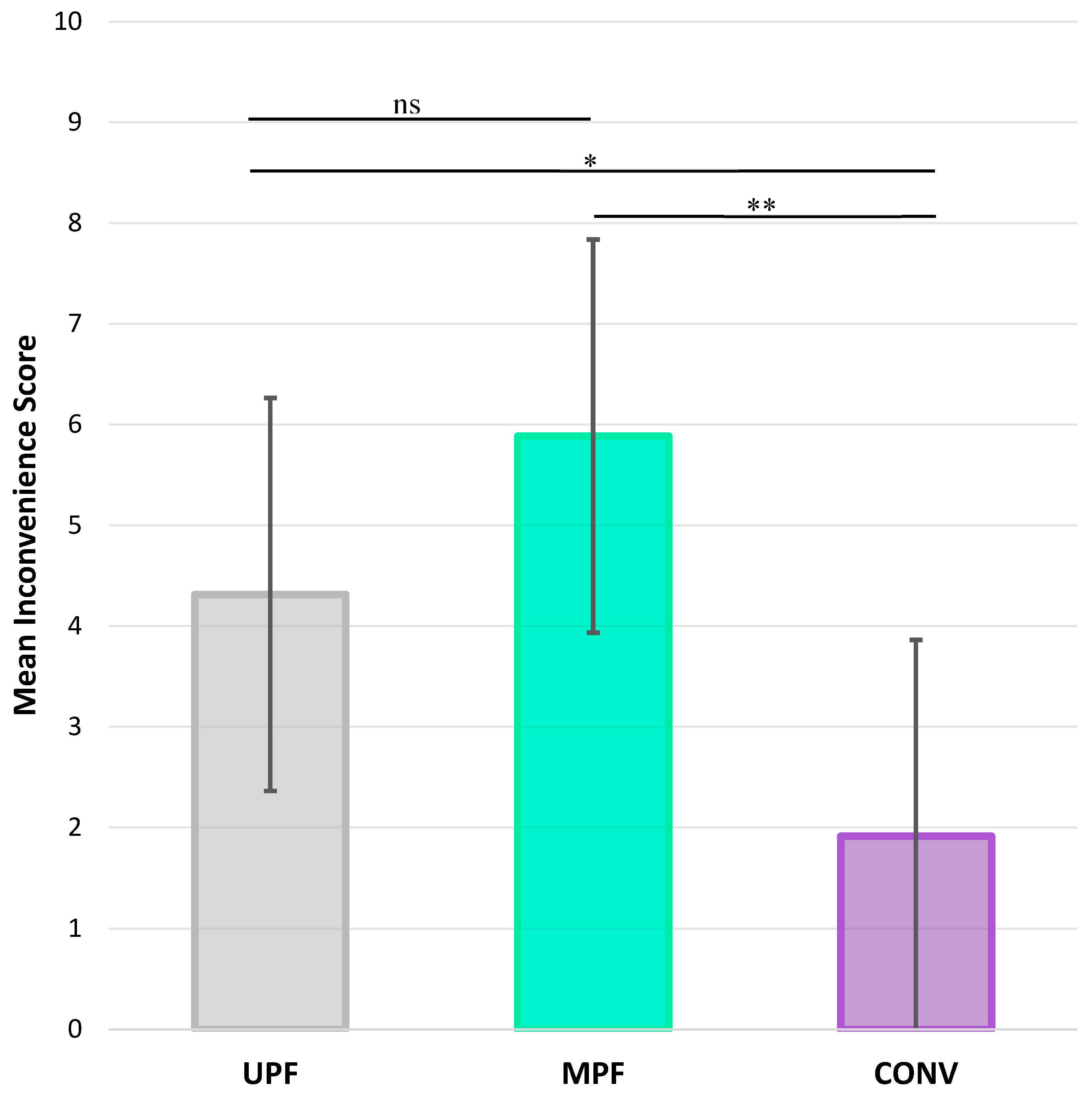

Meal Inconvenience Score

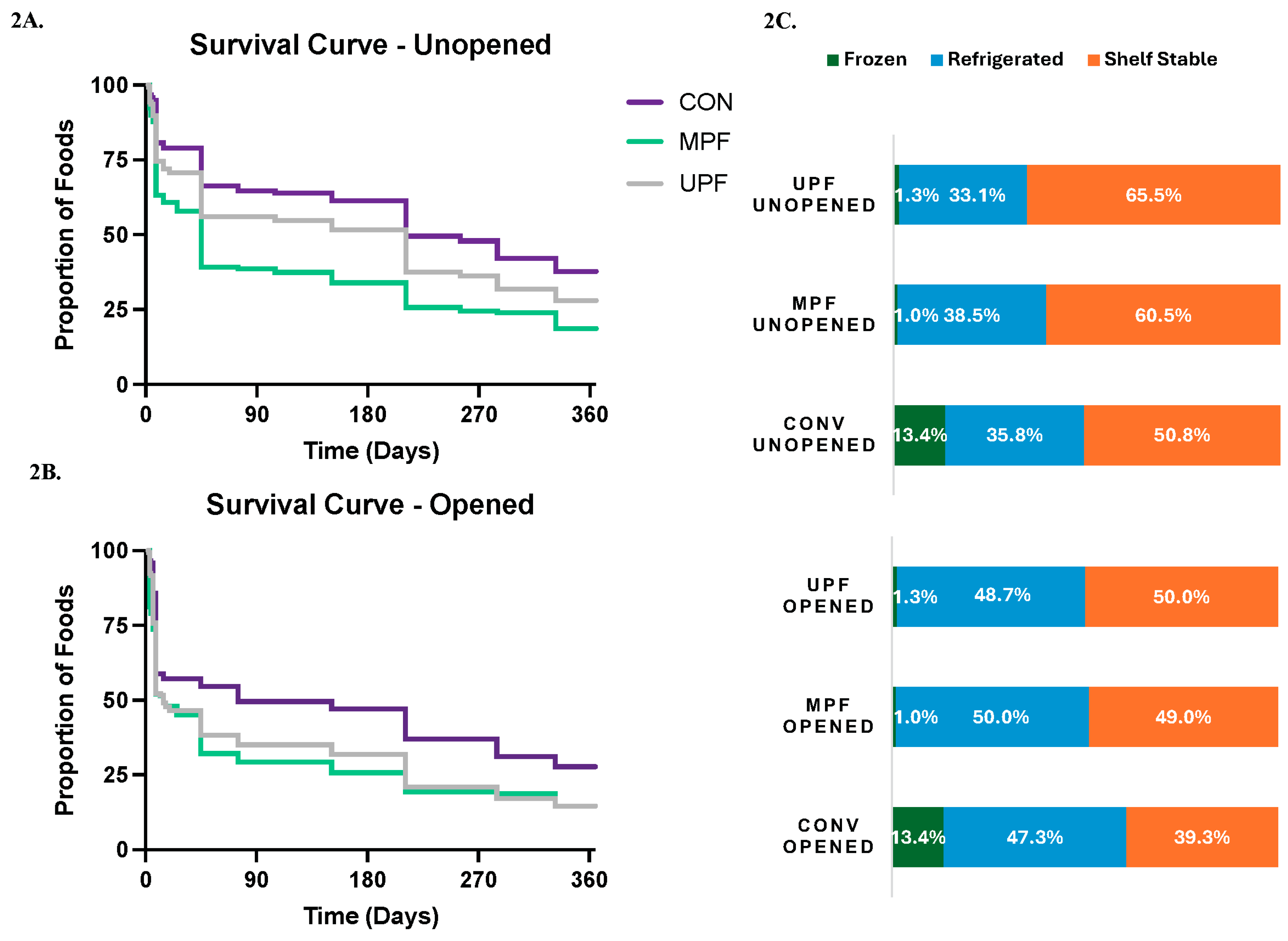

Shelf Stability of the Initial 7-Day Menus

Nutrient Content, Energy Density, and Hyper-Palatable Foods

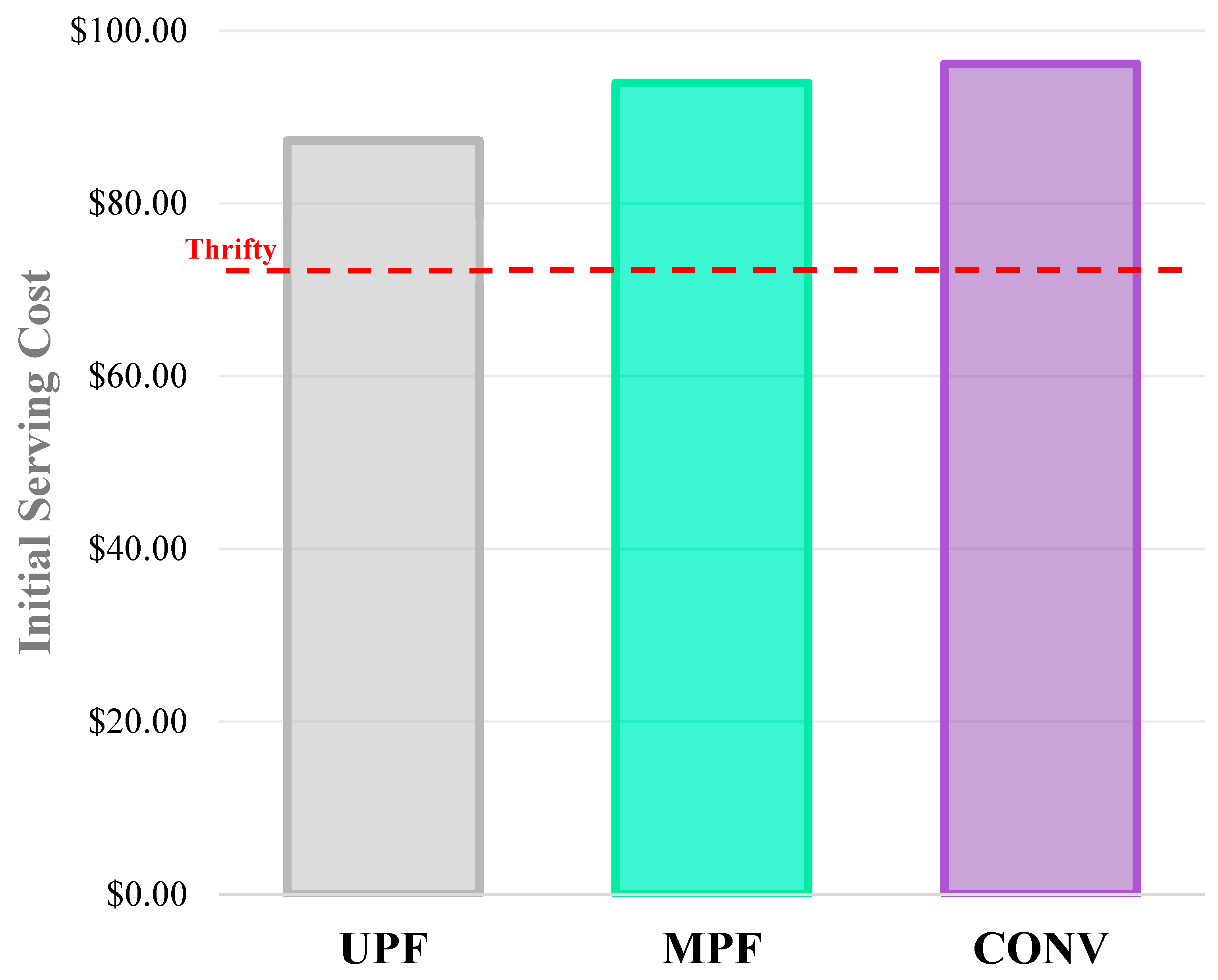

Initial Food Cost

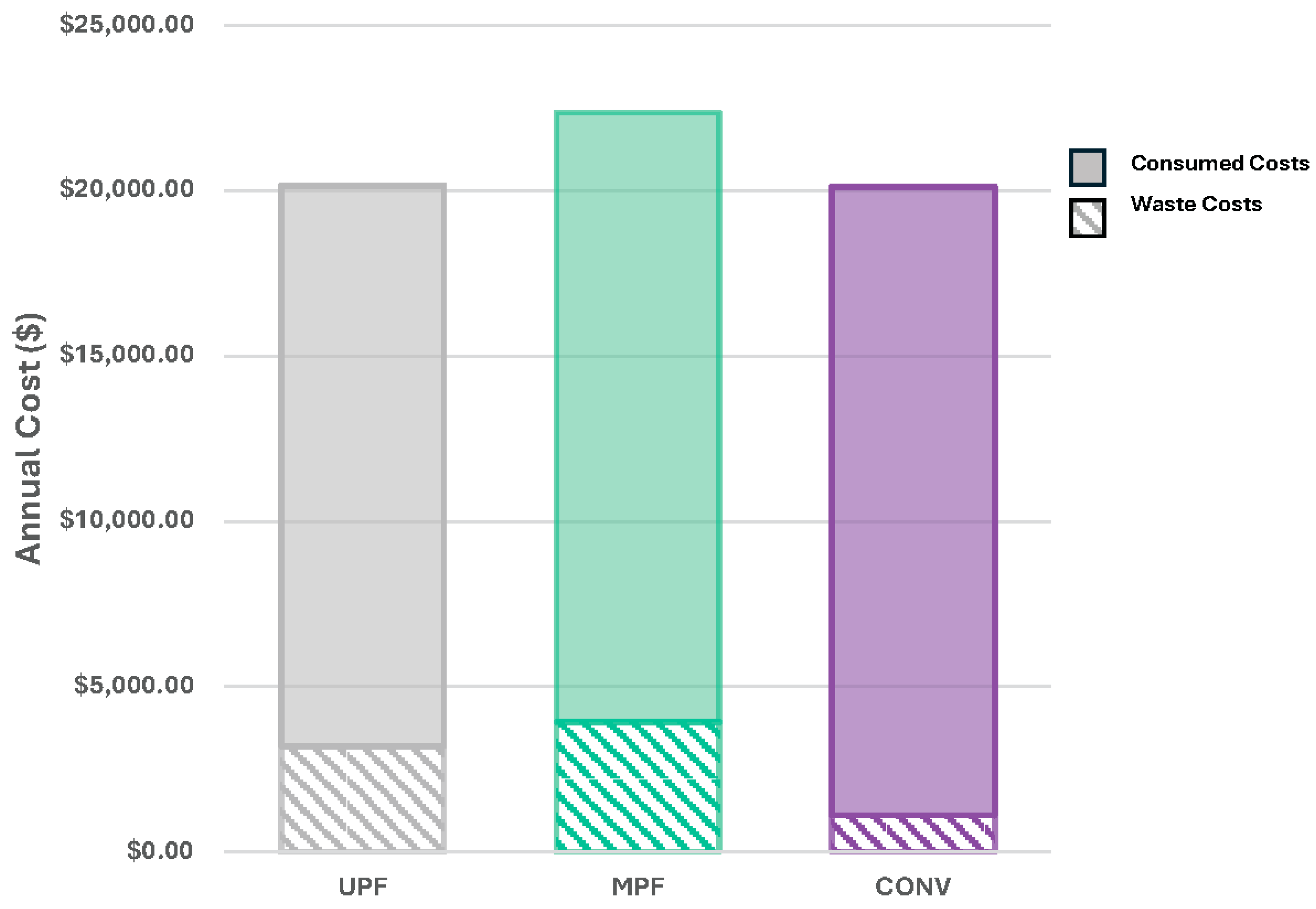

Annual Cost Analysis Using 52-Week Shopping Simulation

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Author Disclosures

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of interest

References

- Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Levy RB, Moubarac JC, Louzada ML, Rauber F, et al. Ultra-processed foods: what they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22(5):936-41. [CrossRef]

- Hall KD, Ayuketah A, Brychta R, Cai H, Cassimatis T, Chen KY, et al. Ultra-Processed Diets Cause Excess Calorie Intake and Weight Gain: An Inpatient Randomized Controlled Trial of Ad Libitum Food Intake. Cell Metab. 2019;30(1):226. [CrossRef]

- Hamano S, Sawada M, Aihara M, Sakurai Y, Sekine R, Usami S, et al. Ultra-processed foods cause weight gain and increased energy intake associated with reduced chewing frequency: A randomized, open-label, crossover study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2024;26(11):5431-43. [CrossRef]

- Lane MM, Davis JA, Beattie S, Gomez-Donoso C, Loughman A, O'Neil A, et al. Ultraprocessed food and chronic noncommunicable diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 43 observational studies. Obes Rev. 2021;22(3):e13146. [CrossRef]

- Taneri PE, Wehrli F, Roa-Diaz ZM, Itodo OA, Salvador D, Raeisi-Dehkordi H, et al. Association Between Ultra-Processed Food Intake and All-Cause Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2022;191(7):1323-35. [CrossRef]

- Wang M, Du X, Huang W, Xu Y. Ultra-processed Foods Consumption Increases the Risk of Hypertension in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Hypertens. 2022;35(10):892-901. [CrossRef]

- Yuan L, Hu H, Li T, Zhang J, Feng Y, Yang X, et al. Dose-response meta-analysis of ultra-processed food with the risk of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality: evidence from prospective cohort studies. Food Funct. 2023;14(6):2586-96. [CrossRef]

- Popkin BM, Miles DR, Taillie LS, Dunford EK. A policy approach to identifying food and beverage products that are ultra-processed and high in added salt, sugar and saturated fat in the United States: a cross-sectional analysis of packaged foods. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2024;32:100713. [CrossRef]

- Juul F, Parekh N, Martinez-Steele E, Monteiro CA, Chang VW. Ultra-processed food consumption among US adults from 2001 to 2018. Am J Clin Nutr. 2022;115(1):211-21. [CrossRef]

- Pomeranz JL, Mande JR, Mozaffarian D. U.S. Policies Addressing Ultraprocessed Foods, 1980-2022. Am J Prev Med. 2023;65(6):1134-41. [CrossRef]

- Services USDoAaUSDoHaH. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. 9th Edition [Internet]. December 2020; Available from: https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/resources/2020-2025-dietary-guidelines-online-materials.

- Monteiro CA, Levy RB, Claro RM, Castro IRRd, Cannon G. A new classification of foods based on the extent and purpose of their processing. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2010-11;26(11). [CrossRef]

- Council IFI. 2024 Food & Health Survey. june 20, 2024.

- Imtiyaz H, Soni P, Yukongdi V. Assessing the Consumers' Purchase Intention and Consumption of Convenience Food in Emerging Economy: The Role of Physical Determinants. Sage Open. 2023;13(1). doi: Artn 21582440221148434, 10.1177/21582440221148434.

- Hess JM, Comeau ME, Palmer DG. Preparation time does not reflect nutrition and varies based on level of processing. The Journal of Nutrition. 2025/05/23. [CrossRef]

- Aljahdali AA. Food insecurity and ultra-processed food consumption in the Health and Retirement Study: Cross-sectional analysis. The Journal of nutrition, health and aging. 2025;29(2):100422. [CrossRef]

- Leung CW, Fulay AP, Parnarouskis L, Martinez-Steele E, Gearhardt AN, Wolfson JA. Food insecurity and ultra-processed food consumption: the modifying role of participation in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2022;116(1):197-205. [CrossRef]

- Leung CW, Epel ES, Ritchie LD, Crawford PB, Laraia BA. Food Insecurity Is Inversely Associated with Diet Quality of Lower-Income Adults. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2014;114(12):1943-53.e2. [CrossRef]

- 2025 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: Meeting 5 (Day 2). Departments of Health and Human Services (HHS), 2024.

- Hess JM, Comeau ME, Casperson S, Slavin JL, Johnson GH, Messina M, et al. Dietary Guidelines Meet NOVA: Developing a Menu for A Healthy Dietary Pattern Using Ultra-Processed Foods. J Nutr. 2023;153(8):2472-81. [CrossRef]

- Gibney MJ. Ultra-Processed Foods: Definitions and Policy Issues. Curr Dev Nutr. 2019;3(2):nzy077. [CrossRef]

- Price EJ, Du M, McKeown NM, Batterham MJ, Beck EJ. Excluding whole grain-containing foods from the Nova ultraprocessed food category: a cross-sectional analysis of the impact on associations with cardiometabolic risk measures. Am J Clin Nutr. 2024;119(5):1133-42. [CrossRef]

- Hess JM, Comeau ME, Scheett AJ, Bodensteiner A, Levine AS. Using Less Processed Food to Mimic a Standard American Diet Does Not Improve Nutrient Value and May Result in a Shorter Shelf Life at a Higher Financial Cost. Current Developments in Nutrition. 2024/11/01;8(11). [CrossRef]

- Agriculture USDo. FoodData Central [Internet]. Available from: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/.

- Osipov O. 5 Minute Strawberry Yogurt [Internet]. iFoodReal; 2004; [cited November 23]. Available from: https://ifoodreal.com/strawberry-yogurt-recipe/.

- Daniels S, Glorieux I. Convenience, food and family lives. A socio-typological study of household food expenditures in 21st-century Belgium. Appetite. 2015;94:54-61. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Steele E, Khandpur N, Batis C, Bes-Rastrollo M, Bonaccio M, Cediel G, et al. Best practices for applying the Nova food classification system. Nature Food 2023 4:6. 2023-06-01;4(6). [CrossRef]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-81. [CrossRef]

- Monteiro CA, Cannon, G., Lawrence, M., Costa Louzada, M.L. and Pereira Machado, P. Ultra-processed foods, diet quality, and health using the NOVA classification system., 2019.

- Jones MS, House LA, Gao Z. Respondent Screening and Revealed Preference Axioms: Testing Quarantining Methods for Enhanced Data Quality in Web Panel Surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2015/01/01;79(3). [CrossRef]

- Services USDoHaH. FoodKeeper App [Internet]. 2019; Available from: foodsafety.gov.

- Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank Shelf Life of Food Bank Products.

- (FDA) FaDA. Refrigerator & Freezer Storage Chart [Internet]. 2021; [cited February]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/74435/download.

- Huffstetler E. Refrigerator and Freezer Storage Charts. 2019.

- Team R. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. Boston, MA: RStudio, PBC, 2025.

- The Food Processor Nutrition Analysis Software. 11.14.9 ed: ESHA Research, Inc., 2022.

- Agriculture UDo. How the HEI Is Scored [Internet]. Food and Nutrition Service; Available from: https://www.fns.usda.gov/cnpp/how-hei-scored.

- Service AR. Food Patterns Equivalents Database [Internet]. US Department of Agriculture; Available from: https://www.ars.usda.gov/northeast-area/beltsville-md-bhnrc/beltsville-human-nutrition-research-center/food-surveys-research-group/docs/fped-methodology/.

- Krebs-Smith SM, Pannucci TE, Subar AF, Kirkpatrick SI, Lerman JL, Tooze JA, et al. Update of the Healthy Eating Index: HEI-2015. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2018/09/01;118(9). [CrossRef]

- Fazzino TL, Rohde K, Sullivan DK. Hyper-Palatable Foods: Development of a Quantitative Definition and Application to the US Food System Database. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2019;27(11):1761-8. [CrossRef]

- Gamer MaL, Jim and Singh, Ian Fellows Puspendra. irr: Various Coefficients of Interrater Reliability and Agreement. 0.84.1 ed: CRAN, 2019.

- Therneau T. A Package for Survival Analysis in R. 3.5-7 ed: CRAN, 2023.

- Kassambara AK, M.; Biecek, P. survminer: Drawing Survival Curves using 'ggplot2'. 0.4.9 ed: CRAN, 2021.

- Service FaN. USDA Food Plans: Monthly Cost of Food Reports [Internet]. US Department of Agriculture; 2024; Available from: https://www.fns.usda.gov/cnpp/usda-food-plans-cost-food-monthly-reports.

- Agriculture USDo. Official USDA Thrifty Food Plan: U.S. Average, October 2023 [Internet]. 2023; Available from: https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/Cost_Of_Food_Thrifty_Food_Plan_October_2023.pdf.

- Poti JM, Mendez MA, Ng SW, Popkin BM. Is the degree of food processing and convenience linked with the nutritional quality of foods purchased by US households? Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(6):1251-62. [CrossRef]

- Baker P, Machado P, Santos T, Sievert K, Backholer K, Hadjikakou M, et al. Ultra-processed foods and the nutrition transition: Global, regional and national trends, food systems transformations and political economy drivers. Obes Rev. 2020;21(12):e13126. [CrossRef]

- Insights PM. Ready to Eat Food Market Size Value Will Grow Over USD 489.3 Billion by 2034, at 9.7% CAGR: Prophecy Market Insights [Internet]. 2024; Available from: https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2024/08/30/2938563/0/en/Ready-to-Eat-Food-Market-Size-Value-Will-Grow-Over-USD-489-3-Billion-by-2034-at-9-7-CAGR-Prophecy-Market-Insights.html.

- Lenk KM, Winkler MR, Caspi CE, Laska MN. Food shopping, home food availability, and food insecurity among customers in small food stores: an exploratory study. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2021 Jan 9;10(6). [CrossRef]

- Morland K, Filomena S. Disparities in the availability of fruits and vegetables between racially segregated urban neighbourhoods | Public Health Nutrition | Cambridge Core. Public Health Nutrition. 2007/12;10(12). [CrossRef]

- Gebauer H, Laska MN, Gebauer H, Laska MN. Convenience Stores Surrounding Urban Schools: An Assessment of Healthy Food Availability, Advertising, and Product Placement. Journal of Urban Health 2011 88:4. 2011-04-14;88(4). [CrossRef]

- Council IFI. Food & Health Survey. 2023.

- Service UER. Food Access Research Atlas [Internet]. USDA; 2025; Available from: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-access-research-atlas/documentation#:~:text=Using%20this%20measure%2C%20an%20estimated%201.9%20million%20households%2C%20or%201.7,20%20miles%20from%20a%20supermarket.

- Gustat J, O'Malley K, Luckett BG, Johnson CC. Fresh produce consumption and the association between frequency of food shopping, car access, and distance to supermarkets. Preventive Medicine Reports. 2015/01/01;2. [CrossRef]

- Liese AD, Bell BA, Barnes TL, Colabianchi N, Hibbert JD, Blake CE, et al. Environmental influences on fruit and vegetable intake: results from a path analytic model | Public Health Nutrition | Cambridge Core. Public Health Nutrition. 2014/11;17(11). [CrossRef]

- Gustat J, Lee Y-S, O'Malley K, Luckett B, Myers L, Terrell L, et al. Personal characteristics, cooking at home and shopping frequency influence consumption. Preventive Medicine Reports. 2017/06/01;6. [CrossRef]

- Banks J, Fitzgibbon ML, Schiffer LA, Campbell RT, Antonic MA, Braunschweig CL, et al. Relationship between Grocery Shopping Frequency and Home- and Individual-level Diet Quality among Low-income Racial/Ethnic Minority Households with Preschool-age Children. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2020 Aug 19;120(10). [CrossRef]

- Changes in the local food-at-home environment, supplemental nutrition assistance program participation, and dietary quality: Evidence from FoodAPS. Journal of the Agricultural and Applied Economics Association. 2022;1(2). [CrossRef]

| Category |

Inconvenient (2) |

Semi-Convenient (1) |

Convenient (0) |

|

| Score | ||||

| Meal Ingredients | Full (fast) Meals | |||

| (2a) Single meal components used for cooking from scratch (Fresh meat (cuts), fish and seafood, vegetables, fruit, rice, eggs, pasta and potatoes) |

(1a) Partially prepared and/or preserved single meal components (Canned, frozen, smoked or pre- prepared fish or seafood, frozen meat products, potato croquettes, French fries, frozen, tinned or dried vegetables (e.g. dried beans), canned, dried, frozen or candied fruits) |

(0a) Complete fast meals (e.g. ready-to-(h)eat meals (based on vegetables, meat or fish), premade soups, pizza, lasagna, or canned pasta dishes, ready-made diet meals, baby food, ready-to-eat sandwiches) |

(0a) Meals out (e.g. away-from-home food or restaurant expenditures) |

|

| Accessory Ingredients | ||||

| (2b) Accessory meal ingredients (e.g. fats, oils, dried herbs, spices, flour, yeast, starch and flavors) |

(1b) Ready-made accessory stuffs (e.g. sauces (e.g. pre-prepared pesto or store- bought pasta sauces, mayonnaise, mustard, apple sauce), bouillon cubes, meat juices, liquid meat preparations) |

|||

| (1c) 'Other' (e.g. Bread, sandwich fillings, milk products and breakfast cereals) |

(0c) ‘Ready-to-eat’ snacks (e.g. biscuits, cakes, sweets, crisps, ice cream) |

|||

| DAY 1 | DAY 2 | DAY 3 | DAY 4 | |

| BREAKFAST |

Breakfast burrito 1 flour tortilla 7” in diameter ¼ c. liquid egg whites (in 1 tsp butter) 1/3 c. canned black beans 1 oz shredded cheddar cheese 1 c. orange juice 1 c. nonfat milk |

Hot cereal ½ c. instant oatmeal 1 tbsp brown sugar 2 tbsp raisins 1 tsp butter ½ c. nonfat milk 1 c. apple juice |

Cold cereal 1 c. honey nut oat cereal † 1 c. nonfat milk 1 small banana 1 slice whole wheat toast † 1 tsp butter 1 c. grapefruit juice |

English muffin 1 whole wheat English muffin † 2 tsp butter 1 tbsp jam † 1 c. grapefruit juice 1 hard-boiled egg |

| LUNCH |

Turkey sandwich 2 slices whole wheat bread † 3 oz deli turkey † 2 slices tomato ¼ c. shredded romaine lettuce 1/8 c. mushrooms 1 ½ oz shredded mozzarella 1 tsp yellow mustard 3/4 c. frozen grilled potatoes 12 oz sparkling water* |

Taco salad 2 oz tortilla chips 2 oz ground turkey, sauteed in 1 tbsp sunflower oil ½ c. canned black beans ½ c. iceberg lettuce 1 tbsp canned diced tomato 1 oz shredded cheddar 2 tbsp salsa ½ c. guacamole 12 oz sparkling water † |

Tuna fish sandwich 2 slices rye bread* 3 oz cracked black pepper tuna 2 tsp mayonnaise † 1 tbsp diced celery ¼ c. shredded romaine lettuce 2 slices tomato 1 c. pear slices 1 c. nonfat milk |

Black bean soup 2 ¾ c. canned black bean soup 2 oz whole wheat bread/dinner roll* ½ c. frozen carrots 1 c. nonfat milk |

| DINNER |

Salmon rice bowl 2 packets lemon pepper salmon ½ c. white rice 1 tbsp chopped scallions ¼ c. diced cucumber 1 tbsp sesame seeds 3 tsp mayonnaise † 1 tsp hot sauce Toasted nori (4g package) ½ c. steamed broccoli 1 c. nonfat milk |

Spinach pasta bake 1 c. gluten-free pasta 2/3 c. cooked spinach ½ c. skim milk ricotta † ½ c. diced tomatoes 1 oz mozzarella cheese 1 oz whole wheat dinner roll* 1 c. nonfat milk |

Chicken dinner 3 oz rotisserie chicken 1 c. mixed greens 1.5 c. yams ½ c. sweet peas 1 oz whole wheat dinner roll † |

Pasta with meat sauce 1 c. gluten-free pasta ½ c. tomato sauce 3 oz extra lean group beef), in 2 tsp vegetable oil 3 tbsp grated Parmesan cheese Spinach salad 1 c. baby spinach leaves 1 c. mandarin oranges ½ oz glazed walnuts 3 tsp thousand island salad dressing † 1 c. nonfat milk |

| SNACK | 1 c. homemade fruit cocktail | ½ oz roasted almonds ¼ c. mandarin oranges 2 tbsp raisins |

¼ c. dried apricots 5 oz low-fat yogurt 1 oz brown sugar 1 oz strawberries |

1 c. low-fat yogurt 1 tbsp brown sugar |

| † Denotes foods from Nova Category 4 | ||||

| DAY 5 | DAY 6 | DAY 7 | ||

| BREAKFAST |

Cold cereal 1 c. shredded wheat cereal † 1 tbsp raisins 1 c. nonfat milk ½ c. peach slices 1 slice whole wheat toast † 1 tsp butter 1 tsp jelly † |

Peanut butter toast 2 slices whole wheat toast † 2 tsp butter 2 tbsp peanut butter ½ c. peach slices 1 c. nonfat milk |

Hot cereal ½ c. Instant oatmeal 2 tbsp raisins ½ c. nonfat milk 1 c. pear slices |

|

| LUNCH |

Chicken sandwich 2 oz whole wheat pita bread † ¼ c. romaine lettuce 2 slices tomato 3 oz deli-style turkey 1 tbsp thousand island dressing † 1 tsp yellow mustard ½ c. applesauce † 1 c. tomato juice † |

Chili on a baked potato 1 c. vegetarian chili 2 oz ground turkey sauteed in 1 tbsp canola oil 1 medium baked potato ½ c. pear slices ¾ c. grapefruit juice |

Clam chowder 1 c. soup ½ c. mushrooms ½ c. onions ¾ c. mixed vegetables 10 whole wheat crackers 1 c. nonfat milk |

|

| DINNER |

Steak dinner 5 oz grilled top loin steak ¾ c. frozen potatoes ½ c. frozen carrots 2 oz whole wheat dinner roll † 1 tsp butter 1 c. nonfat milk |

Pizza 2 7-inch tortillas (7”) 2 oz shredded mozzarella cheese ¼ c. tomato sauce 1 oz hot pork sausage † ¼ c. roasted red bell peppers 2 tbsp mushrooms 2 tbsp onions Green salad 1 c. leafy greens 3 tsp Italian salad dressing † 1 c. nonfat milk |

Vegetable stir fry 4 oz firm tofu † ½ c. water chestnuts † ¼ c. canned carrots 1 c. brown rice and quinoa with garlic 1 c. grapefruit juice |

|

| SNACK | 1 c. strawberry kefir † | 5 whole wheat crackers 1 oz honey-roasted chickpeas † ½ c. homemade fruit cocktail |

1 oz salt and pepper cashews 1 c. sliced peaches 1 c. plain greek yogurt 2 tbsp brown sugar |

|

| † denotes foods from Nova Category 4 | ||||

| DAY 1 | DAY 2 | DAY 3 | DAY 4 | |

| BREAKFAST |

1 ct. Breakfast burrito 1 c. orange juice 1 c. nonfat milk |

Hot cereal ½ c. instant oatmeal 1 tsp soft margarine ½ c. nonfat ultrafiltered milk 1 c. apple juice |

Cold cereal 1 c. honey nut oat cereal 1 c. nonfat ultrafiltered milk 1 small banana* 1 slice whole wheat toast 1 tsp soft margarine 1 c. grapefruit juice |

English muffin 1 whole wheat English muffin 2 tsp soft margarine 1 tbsp jam 1 c. grapefruit juice 1 hard-boiled egg |

| LUNCH |

1 ct. Turkey and cheese sandwich 2 oz. canned tomato ¼ c. shredded romaine lettuce* 1/8 c. mushrooms 1 tsp yellow* mustard 3/4 c. frozen grilled potatoes 12 oz sparkling water |

1 ct. Chef salad kit 2 oz flavored tortilla chips ½ c. canned black beans 2 tbsp salsa ½ c. guacamole 12 oz sparkling water |

Tuna fish sandwich 2 slices rye bread 4 oz tuna salad ¼ c. shredded romaine lettuce* 2 oz. canned tomato 1 serving pear slices 1 c. nonfat ultrafiltered milk |

Black bean soup 2 ¾ c. canned black bean soup 2 oz whole wheat bread/dinner roll ½ c. canned carrots 1 c. nonfat ultrafiltered milk |

| DINNER |

Salmon rice bowl 2 packets lemon pepper salmon ½ c. white rice 1 tbsp chopped scallions* ¼ c. diced cucumber* 1 tbsp sesame seeds* 3 tsp mayonnaise 1 tsp hot sauce* Toasted nori (4g package)* ½ c. steamed broccoli* 1 c. nonfat ultrafiltered milk |

2 ½ c. Spinach ricotta ravioli ½ c. diced tomatoes 1 oz whole wheat dinner roll 1 c. nonfat ultrafiltered milk |

1 ct. chicken marsala 1 c. mixed greens 1 oz whole wheat dinner roll |

3 c. Pasta with meat sauce Spinach salad 1 c. baby spinach leaves* 2 servings mandarin oranges ½ oz glazed walnuts 3 tsp thousand island salad dressing 1 c. nonfat ultrafiltered milk |

| SNACK | 2 sv. fruit cocktail | ½ oz roasted almonds ¼ c. mandarin oranges 2 tbsp raisins |

¼ c. dried apricots 6 oz low-fat strawberry yogurt |

1 c. low-fat vanilla yogurt |

| ∗ denotes foods from Nova Categories 1-3 (i.e. minimally processed foods) | ||||

| DAY 5 | DAY 6 | DAY 7 | |

| BREAKFAST |

Cold cereal 1 c. shredded wheat raisin cereal 1 c. nonfat ultrafiltered milk 1 sv. peach slices 1 slice whole wheat toast 1 tsp soft margarine 1 tsp jelly |

1 ct. Peanut butter pie 1 sv. peach slices 1 c. nonfat ultrafiltered milk |

Hot cereal ½ c. Instant oatmeal ½ c. nonfat ultrafiltered milk 2 sv. pear slices |

| LUNCH |

1 ct. Chicken caesar wrap 2 tbsp. canned tomato 1 tsp yellow mustard* ½ c. applesauce 1 c. tomato juice |

Chili and potato 1 c. turkey chili ¾ c. frozen grilled potato 1 sv.. pear slices ¾ c. mixed fruit juice |

Clam chowder 1 c. soup ½ c. mushrooms ½ c. onions ¾ c. mixed vegetables 10 whole wheat crackers 1 c. nonfat ultrafiltered milk |

| DINNER |

1 ct. Salisbury Steak and potatoes ½ c. honey glazed carrots 2 oz whole wheat dinner roll 1 tsp soft margarine 1 c. nonfat ultrafiltered milk |

1 ct. Pizza burrito 2 tbsp mushrooms Green salad 1 c. leafy greens* 3 tsp Italian salad dressing 1 c. nonfat ultrafiltered milk |

1 ct Tofu stir fry ½ c. water chestnuts ¼ c. canned carrots 1 c. cran-raspberry juice |

| SNACK | 1 c. strawberry kefir | 5 whole wheat crackers 1 oz honey-roasted chickpeas 1 sv. fruit cocktail |

1 oz dill pickle cashews 2 sv. sliced peaches 1 c. vanilla Greek yogurt |

| ∗ denotes foods from Nova Categories 1-3 (i.e. minimally processed) | |||

| UPF | MPF | CONV | |

| Group 1 and 2 Foods (minimally processed, unprocessed, and processed culinary ingredients) | 6% | 35% | 2% |

| Group 3 Foods (processed foods) | 3% | 45% | 2% |

| Group 4 Foods (ultra-processed foods) | 91% | 20% | 96% |

| Nutrients | UPF | MPF | CONV |

| MACRONUTRIENTS | |||

| Energy (kcal) | 2025 | 2020 | 2000 |

| Non-beverage Energy density (kcal/g) | 1.24 | 1.22 | 1.30 |

| % Energy from Hyper-palatable Food | 46% | 37% | 55% |

| Protein (g) | 108 | 96 | 101 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 281 | 282 | 276 |

| Added sugars (g) | 29 | 24 | 31 |

| Added sugar (teaspoon equivalents) | 6.92 | 5.73 | 7.40 |

| Fiber, total dietary (g) | 39 | 41 | 34 |

| Total fat (g) | 56.5 | 58.1 | 59.1 |

| Saturated fat (g) | 14.6 | 15.7 | 16.2 |

| Monounsaturated fat (g) | 20 | 22 | 20 |

| Polyunsaturated fat (g) | 16 | 17 | 15 |

| Omega-3 fat (g) | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.74 |

| Omega-6 fat (g) | 6.32 | 6.94 | 4.67 |

| Cholesterol (mg) | 165 | 144.3 | 125.6 |

| Calcium (mg) | 1583 | 1456 | 1622 |

| Iron (mg) | 21.0 | 20.5 | 17.3 |

| Potassium (mg) | 3750 | 4141 | 3440 |

| Sodium (mg) | 4435 | 3109 | 5135 |

| Vitamin A, RAE (mcg) | 1530 | 1645 | 1210 |

| Vitamin D (IU) | 387.4 | 393.5 | 385.1 |

| UPF | MPF | CONV | |

| Initial Cost per Serving, 1-Person Household | $87.59 | $94.01 | $96.15 |

| Initial Total Cost, 1-Person Household | $296.90 | $304.89 | $227.49 |

| Initial Total Cost, 4-Person Household | $491.27 | $533.91 | $469.40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).