1. Introduction

Reducing food waste is a critical priority within the European Union, supported by regulatory frameworks aimed at enhancing sustainability and efficiency across the food system [

1]. These regulations promote innovation in food preservation methods to extend shelf life, improve product quality, and reduce losses along the supply chain, particularly at the household level, where a substantial share of food waste occurs [

2]. One of the main factors contributing to food quality deterioration is oxidation, which can reduce nutritional value, alter sensory attributes, and lead to the formation of harmful compounds. To counteract these effects and prolong shelf life, a variety of protective strategies have been developed. Among them, biopolymer-based edible coatings have gained increasing attention. These coatings can perform functions similar to conventional packaging by acting as semi-permeable barriers to oxygen and moisture, thereby slowing lipid oxidation and limiting moisture absorption or desorption. Such properties make the coatings especially useful for oxidation-sensitive products like nuts. Furthermore, incorporating natural antioxidants into the formulation can significantly enhance the protective efficacy [

3]. This strategy may enhance antioxidant effectiveness by delivering active compounds directly to the surface, where oxidative processes are most intense. The efficiency of active coatings depends on the type and concentration of incorporated antioxidants, as well as on interactions between coating components, antioxidants, and the food matrix. These factors influence the release and migration of active agents to target sites. So, the selection of antioxidants must be well-justified, taking into account their polarity, mechanism of action, and compatibility with the coating matrix. Both polar and non-polar antioxidants tend to accumulate at oil/air or oil-in-water interfaces, which are critical sites where oxygen comes into contact with polyunsaturated fatty acids. According to the 'polar paradox' theory, hydrophilic antioxidants are more effective in non-polar environments (e.g., pure oils), while lipophilic ones perform better in polar systems such as emulsions, liposomes, biological membranes, or tissues [

4]. This suggests that polar antioxidants may be more suitable as components of coatings for lipophilic foods with low water content. Since nuts have low moisture (typically below 5%) and high fat content (around ≥60%) [

5,

6], vitamin C (a polar antioxidant) would be expected to act effectively as an antioxidant in coatings. However, a previous study [

7] showed that the incorporation of L-ascorbic acid into the coating formulation did not enhance the antiperoxidant properties when applied to walnuts. This discrepancy indicates that the paradigm of the polar antioxidant paradox oversimplifies the mechanisms of antioxidant activity [

4]. As a result, ongoing research is exploring the use of ascorbyl palmitate (AP) – water-insoluble vitamin C derivative to deepen understanding and develop more comprehensive theories that better explain antioxidant behavior in coating/food systems. The use of non-polar active substances in biopolymer packaging systems is further justified by their potential to enhance water vapor barrier properties [

8,

9], thereby more effectively reducing moisture loss or absorption during food storage [

10].

Although AP is referred to as the lipophilic form of vitamin C, its solubility data in oils is not available. AP is practically insoluble in water (0.00003 g/L at 25 °C) but dissolves well in ethanol. As an ester of ascorbic acid and palmitic acid, AP has an amphiphilic nature, which allows it easier penetration through lipid membranes and enhances tissue distribution. AP protects against oxidative DNA damage and inhibits cancer cell proliferation. Compared to AA, it is more stable, making it a promising antioxidant for active edible films and coatings. However, its partial hydrophobicity and high melting point (107–117 °C) limit its use in aqueous solutions, necessitating cosolvents or emulsifiers to form stable emulsions [

11]. So far, AP combined with α-tocopherol has been applied in whey protein-based edible coatings, but such coatings, with or without antioxidants, showed similar effects in slowing lipid oxidation in roasted peanuts [

12].

A universal carrier designed for loading both hydrophilic and hydrophobic substances should possess amphiphilic properties. Careful selection of biopolymers and manufacturing techniques allows for the creation of matrices capable of effectively binding, stabilizing, and releasing various active compounds. Considering their lower carbon footprint, plant-based biopolymers are generally more environmentally friendly than animal-based ones. However, animal-derived biopolymers, such as gelatin (GEL), possess unique properties that are difficult to substitute in certain applications. Blending biopolymers enables the production of materials with improved or novel properties. Gum Arabic (GAR) is a highly branched heteropolysaccharide with hydrophilic sugar groups, while GEL is a protein containing both hydrophilic and hydrophobic amino acids, giving it surface-active properties. Although GEL’s emulsifying ability is generally weaker than other amphiphilic compounds like GAR, its excellent gelling and thickening properties help maintain the stability of oil-water emulsions during film formation [

13,

14]. This study selected GAR/GEL formulation as a carrier for AP based on prior research showing that a 75/25 GAR/GEL blend film offers the slowest, most controlled AP release and prolonged antioxidant activity. The branched structure of gum Arabic likely traps AP, limiting its migration and sustaining antioxidant action. AP also improved the water vapor barrier of the films, enhancing their use as edible coatings. The current work builds upon these findings, applying the GAR/GEL/AP system to nuts to evaluate its practical performance in extending shelf life and protecting and/or improving product quality [

9].

The objective of this study was to assess how a GAR/GEL-AP edible coating influences the key quality parameters (weight loss, moisture content, texture, color, antioxidant activity, and markers of lipid degradation) of hazelnut kernels during 16 weeks of storage in at 23 °C and 50% relative humidity in closed polypropylene boxes, in the absence of light.

2. Results

2.1. Characterization of Coating-Forming Emulsion (CFE)

DIC microscopy revealed that the CFE consisted of spherical droplets with well-defined interfaces and a relatively uniform circular morphology. The droplet size ranged approximately from 6 to 40 μm (

Figure 1B), indicating effective emulsification and moderate size homogeneity. This relatively narrow size distribution and the lack of irregular structures suggest that the emulsion was stable, with only limited signs of coalescence or agglomeration. In contrast, such an effect was not observed in a previous study, where AP in the GAR-based emulsion predominantly appeared as large acicular crystals [

9]. This highlights the improved dispersion and stabilization achieved in the current formulation through ultrasonic processing. At higher magnification, needle-like AP crystals, with an average length of 4–11 μm, were observed inside the emulsion droplets, while the continuous phase contained only dispersed microparticles (

Figure 1B). This localization may be explained by hydrophobic interactions between AP, likely enhanced by the presence of Tween 80 and ethanol, which reduced interfacial tension and facilitated the incorporation of water-insoluble AP. Also, the emulsifying properties of biopolymers (GAR and GEL) may have further promoted internal organization and retention of AP within the droplets. This mechanism is consistent with previous findings in polyethylene glycol–water systems, where AP was shown to form crystalline or liquid crystalline mesophases, suggesting a tendency toward self-assembly under certain conditions [

15].

The pH of the CFE was 5.10 (

Table 1), slightly higher than reported in a previous study [

9], possibly due to the previously mentioned variations in the emulsion microstructure. Measuring the pH of emulsions is inherently challenging because of the coexistence of oil and water phases and the likelihood of heterogeneous pH distribution within the system. It is worth mentioning that the pH value of the CFE was close to that of hazelnuts surface (

Table 2), which may be beneficial for preserving the sensory and chemical stability of the product while avoiding the excessive acidity typically introduced by formulations containing ascorbic acid (AA) [

16].

The η of the CFE was 48.50 ± 5.87 mPa·s (

Table 1), indicating a fluid with moderate viscosity. According to visual observations, this level of viscosity provides sufficient thickness to support uniform film formation without runoff, while maintaining adequate fluidity for practical application. Moreover, it may contribute to emulsion stability by minimizing phase separation during processing. Although the comparison should be interpreted with caution due to differences in formulation, under comparable η measurement conditions (25 °C, shear rate of 50 s⁻¹), the viscosity of the current emulsion is higher than that reported for pea protein-based emulsions containing 2% candelilla wax or oleic acid (≈10 mPa·s) [

17]. This may be attributed to the presence of GEL, which enhances the structuring of the continuous phase and promotes network formation.

2.2. Microstructure of Hazelnuts

The surface of uncoated hazelnuts was characterized by a rough and irregular topography (Rq = 57.57), whereas the coated hazelnuts exhibited a smoother and more homogeneous surface morphology (Rq = 40,22,

Figure 2,

Table 2). Needle-like AP crystals, accompanied by much smaller globules, were abundantly distributed across the surface. It can be observed that they were well-developed and noticeably larger than those in CFE (

Figure 1), likely as a result of co-solvent (ethanol) evaporation. In the cross-sectional view, the testa (skin) appeared as a thin outer layer with non-uniform thickness.

Dipping in the emulsion formed a continuous, loose coating on the testa. Partial detachment in some areas, likely due to mechanical sectioning, suggests weak adhesion to the testa. As confirmed by light microscopy observations (

Figure 3), no impregnation of the testa and nut interior with the emulsion occurred, as evidenced by the absence of blue coloration within the cross-section. The coating was uneven, tending to be visibly thicker at the bottom compared to the top (

Figure 3,

Table 1). The coating thickness was similar to or exceeded that of the testa (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

2.3. pH, Weight Loss (WL), Moisture Content (MC), Hardness, and Color Parameters

Since the CFE had a pH of 5.10 (

Table 1), the surface pH of the coated hazelnuts was lower than that of the control (5.14 vs. 5.60;

Table 2), while the pH of the interior surface remained unaffected by the coating. This proves limited CFE penetration through hazelnut skin (

Figure 3). Nevertheless, hazelnuts absorbed moisture during coating, as indicated by the data in

Figure 4.

As shown in

Figure 4A, coated nuts exhibited greater WL in comparison to the uncoated samples (4.48-6.64 vs. 0.64-1.38%), which was attributed to their higher initial MC (8.17% vs. 3.35%;

Figure 4B) resulting from moisture uptake. The elevated MC enhanced the moisture gradient, thereby accelerating water migration over time. Similar results were previously observed for walnuts coated with emulsion-based coatings [

7]. Throughout storage, the coated hazelnuts retained significantly more moisture than the noncoated ones, suggesting that the GAR/GEL/AP coating acted as a barrier to water loss and effectively mitigated dehydration; however, by the end of the 16-week period, the differences in MC were no longer statistically significant. As commonly known, low MC in nuts is crucial primarily to inhibit microbial growth and reduce the risk of aflatoxin contamination [

18,

19]. It should be noted that, after one week of storage, the MC in the coated hazelnuts was below 6% (

Figure 4B), which complies with the European Union limit of 7% for hazelnut kernels [

20] and also aligns with the commonly recommended maximum of 6% for optimal storage stability [

21,

22].

As shown in

Figure 4C, no significant differences (p < 0.05) in hardness were observed between coated and uncoated hazelnuts during storage. This suggests that moisture uptake (

Figure 4B) did not negatively affect kernel texture, which is beneficial from a sensory perspective. The hardness of hazelnuts varied between approximately 90 and 106 N, with standard deviations of 14–35 N, consistent with variability reported in previous studies [

24,

25]. The 16-week storage had no significant impact on hardness, contrary to Razavi et al. [

23], who observed increasing rupture force over time. In contrast, Correia et al. [

26], found that high humidity reduced hardness and friability, while Guinée et al. noted increased friability of hazelnut kernels only at 90% relative humidity without packaging. These findings indicate that storage effects on hazelnut texture depend strongly on environmental factors such as humidity and packaging.

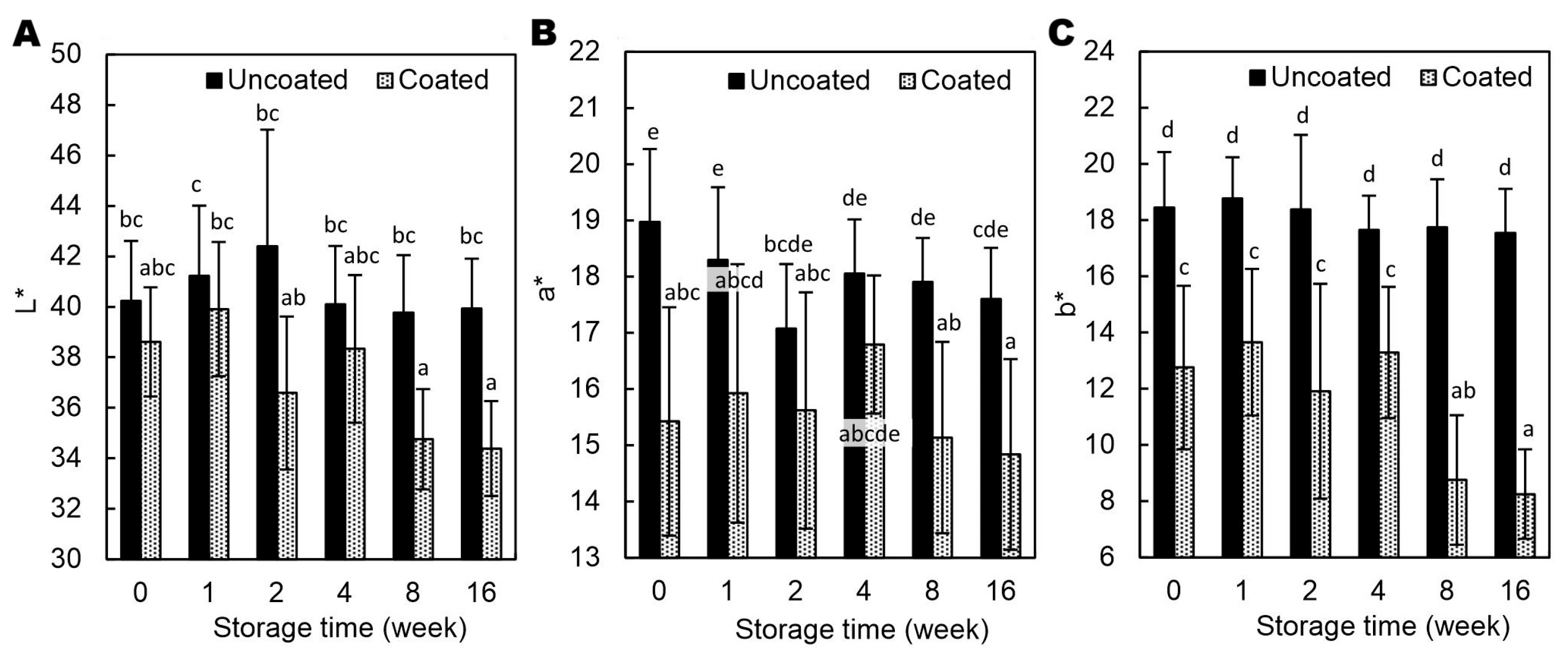

From week 8, the coated hazelnuts showed noticeable darkening compared to initial values and to uncoated samples (

Figure 5A). Unlike walnuts coated with AA-added emulsion, which lighten due to strongly lowered pH to 4.37 [

7,

16], the AP used in this study only slightly reduced surface pH (

Table 2) and thus did not bleach polyphenolic pigments. The coated hazelnuts showed lower b* values, indicating reduced yellowness, with a tendency toward lower a* values as well, suggesting less redness (

Figure 5B-C). The coating may partially mask the natural color of the hazelnut skin by reducing light reflection and increasing diffuse scattering by AP crystals (

Figure 2), leading to a duller, less saturated appearance.

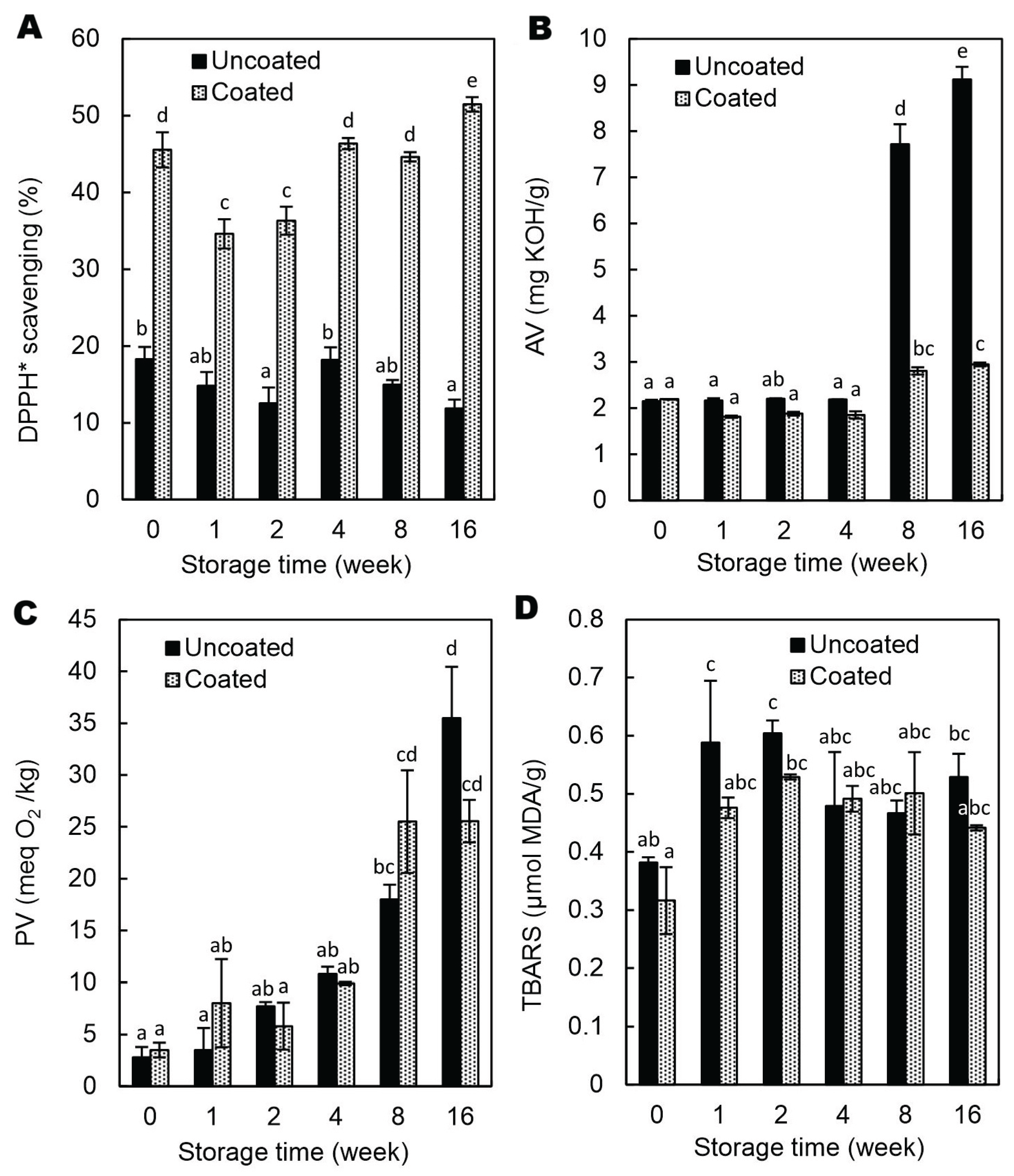

2.4. Antiradical Activity, Acid Value (AV), Peroxide Value (PV), and Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances (TBARS) Concentration

Hazelnuts are a rich source of bioactive compounds such as phenolic acids, proanthocyanidins, and tocopherols, which contribute to their significant antioxidant activity and associated health benefits [

27,

28]. Accordingly, the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical (DPPH*) scavenging activity of uncoated hazelnuts (

Figure 6A) was likely attributed to the synergistic action of alcohol-extractable polyphenols, including esterified gallic acid and condensed tannins concentrated in the skin [

29] and α-tocopherol [

30]. The GAR/GEL/AP-coated hazelnuts exhibited 2.5- to 4.5-fold increase in antiradical activity compared to the control (

Figure 6A). Considering the 2% AP concentration in CFE, the observed increase is relatively small and likely limited by the coating thickness (~100 μm,

Table 1) applied to a relatively small surface area. Moreover, previous studies [

9] have shown that this type of coating exhibits the slowest release rate of AP, suggesting limited migration of the antioxidant from the coating to the acceptor medium with the free radicals. The DPPH* scavenging activity, assessed over time using an immersion method with whole kernels, showed variability (

Figure 6A), likely due to differences in surface contact and resulting variations in AP release, which complicated the clear assessment of storage effects. While this method effectively evaluates surface antioxidant capacity, it may not fully capture synergistic interactions between the coating components and the hazelnut, and thus could somewhat underestimate the total antioxidant potential during consumption.

The AV of oils extracted from both uncoated and coated hazelnuts did not differ significantly up to 4 months of storage (

Figure 6B). However, after doubling this storage time (i.e., after 8 months), lipase-induced hydrolytic degradation increased sharply, with the AV being significantly lower in the coated samples (p < 0.05). One possible explanation is that the CFE, which contained 20% ethanol, reduced the activity of lipases on the kernel surface. Furthermore, ethanol likely inactivated most molds [

31] and, consequently, their lipases, which are known to contribute synergistically to the hydrolytic rancidity of nuts [

32]. Supporting this, Gull et al. [

33] reported that sodium alginate coatings enriched with β-tocopherol significantly reduced free fatty acid content (0.9% vs. 1.4% oleic acid) and microbial counts (1.9 vs. 3.2 log CFU/g) in fresh walnuts compared to uncoated samples [

33]. According to the authors, the reduction in microbial growth could be due to limited oxygen supply by creating a barrier. Similarly, other studies have reported that coatings containing different bioactive compounds effectively reduced microbial, including fungal, growth on nut surfaces by providing antimicrobial protection [

34,

35,

36].

Given that the endogenous lipases of intact nuts are generally inactive on the surface [

37], the coating-induced decrease in surface pH (

Table 2) was unlikely to have contributed significantly to the observed reduction in hydrolytic activity. It is worth noting, however, that in a previous study [

7], the low pH of the AA-containing coating was likely responsible for the reduced activity of native walnut lipase, as evidenced by lower AV compared to the control and AA-free coated walnuts.

The coating did not affect oxidative deterioration of oil in the hazelnuts as evidenced by determination of peroxide and TBARS values (

Figure 6 C-D). This could be attributed to insufficient barrier integrity and/or low adhesion of the coating to the kernel surface. Such findings challenge the common assumption that edible coatings consistently offer antioxidative protection, highlighting that coating efficacy depends strongly on composition, structure, and interaction with the substrate.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

Shelled hazelnut kernels (Corylus avellana L.) were purchased from a commercial supplier in Lublin, Poland. For the study, only kernels weighing approximately 1.5 g each and free from visible defects, discoloration, or signs of spoilage were selected. GAR Agri-Spray Acacia R (Agrigum International, United Kingdom) and pork GEL (bloom strength 240; McCormick-Kamis, Poland) were used as coating-forming biopolymers. Glycerol, AP, Tween 80, and 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (USA). Ethanol (99.8%) was purchased from Avantor Performance Materials Poland S.A.

3.2. Coating Formulation and Procedure

The coating-forming emulsion (CFE) was prepared following the procedure described by Łupina et al. [

9], with the modification of using ultrasound emulsification as described previously [

38]. The CFE consisted a 20% aqueous-ethanolic solution containing GAR/GEL 75:25 blend (10% w/w), glycerol (1% w/w), Tween 80 (0.25% w/w), and AP (2% w/w). Uncoated hazelnut kernels were used as the control. The kernels skewered on sword toothpicks were immersed in the CFE for 30 seconds and then air-dried for 1 h. The coated and uncoated hazelnuts were packed in portions of 10 pieces per container into 200 mL polypropylene PRATIPACK boxes (107 mm in width, 80 mm in length, and 40 mm in height; Guillin Polska, sealed with lids, and stored under controlled conditions (23 ± 1 °C, 40 ± 5% relative humidity, in darkness). The samples for analysis were collected at week 0 (baseline), and after 1, 3, 4, 8, and 16 weeks of storage.

3.3. Analysis of CFE

To examine the morphology of CFE, a Leica 5500B microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) with differential interference contrast optics was used. The pH of the CFE was measured at 30 ± 1 °C using a flat surface electrode (Elmetron EPX-3, Zabrze, Poland)connected to a pH meter (Elmetron CPC 401, Zabrze, Poland). The dynamic viscosity (η, mPa·s) of CFE at 30 ± 1 °C was assessed using a ROTAVISC lo-vi rotational viscometer (IKA, Staufen, Germany) equipped with a VOLS-1 adapter and a VOL-SP-6.7 spindle, operating at 50 rpm for 2 min, with a sample volume of 6.7 mL. All measurements were conducted in triplicate.

3.4. Microstructure and pH

The microstructure of the surface and cross-sections of the hazelnuts was analyzed using a scanning electron microscope (1430VP, LEO Electron Microscopy Ltd., Cambridge, UK). The film samples were re-dried under vacuum and coated with gold before observation. ImageJ open-source software was used to reconstruct 3D surface profiles from 2D topographical images and to determine surface roughness (Rq) [

39]. Additionally, the thickness of the coating stained with methylene blue was measured from microscopic images captured using a Leica 205C microscope equipped with a Leica DFC500 camera(Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany)and analyzed with AxioVision 4.8 software (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Longitudinal cross-sections of the coated hazelnuts were prepared using a scalpel, and the coating thickness was measured at the top, lateral, and bottom regions through microscopic analysis.

The pH of the surface and cross-sections of the hazelnuts was measured as described in section 4.3, after slight surface hydration with 20.0 μL of deionized water.

3.5. Determination of Weight Loss (WL), Moisture Content (MC), Hardness, and Color Parameters

The entire hazelnut kernels batch stored in boxes (~15g) of were used for WL assessment. WL was expressed as the percentage decrease from the initial weight. MC was determined by drying ground samples (~2g) at 105 °C for 24 h. The WL and MC measurements were conducted in four replicates. The maximum force (N), representing kernel hardness, was measured using a TA-XT2i texture analyzer equipped with a 50 kg load cell (Stable Micro Systems, UK). Individual hazelnut kernels were placed on the testing platform and compressed using a 100 mm diameter platen at a constant speed of 5 mm/s until reaching a penetration depth of 2 mm. Color values (L*, a*, b*) were measured with a colorimeter (NH310, 3nh, China). Hardness and color measurements were performed on 10 kernels per treatment.

3.6. Determination of Antiradical Properties

The antiradical activity of hazelnut kernels was assessed using the DPPH* scavenging assay. A single kernel was placed in contact with 20 mL of a methanolic DPPH* solution (absorbance of 2.5 ± 0.05 at 517 nm, 23 °C). The solution was mixed using a magnetic stirrer (400 rpm) and circulated through a flow-through cuvette (Lambda 40 spectrophotometer, Perkin–Elmer, Shelton, CT, USA) via a peristaltic sipper pump (“PESI” B2190036, Perkin–Elmer, USA). A perforated barrier was placed between the kernel and the stir bar. Absorbance at 517 nm was continuously monitored for 1h. The results were expressed as the percentage of DPPH* neutralized, calculated using the formula 1:

where A₀ is the initial absorbance of the DPPH* solution, and Aₛ is the absorbance of DPPH* solution after 1 hour contact with the hazelnut. The measurements were performed in triplicate.

3.7. Determination of Acid Value (AV), Peroxide Value (PV), and Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances (TBARS) Concentration in Hazelnut Oil

Lipid extraction was carried out according to the previously described method [

7]. The AV and PV for the extracted oil were determined according to [

40] ISO 660:2020 and [

41] ISO 3960:2017, respectively. TBARS values were measured following the procedure outlined by [

42]. All measurements were performed in triplicate.

3.8. Statistical Analysis

All results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n ≥ 3). Statistical differences among mean values were evaluated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tuckey test using Statistica software, version 13.3 (TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA). Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

4. Conclusions

The GAR/GEL/AP coating doubled the moisture content of hazelnuts, which in turn led to greater weight loss during storage, highlighting the need for more efficient post-coating drying. Although the coating improved antioxidant properties, it did not provide oxidative protection, likely due to insufficient barrier integrity, possibly resulting from emulsion destabilization during co-solvent (ethanol) evaporation and subsequent crystallization of AP. The observed reduction in hydrolytic rancidity may be attributed to ethanol-induced denaturation of endogenous lipases during the coating process. Further optimization, such as improving homogeneity (emulsion stability), adjusting ingredients ratios, or applying multilayer coatings, is needed to limit moisture uptake caused by dipping in the emulsion and to enhance oxygen barrier performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K. and K.N.; methodology, D.K., T.S, E.Z., and J.J.; validation, D.K; formal analysis, D.K.; investigation, K.N. D.K., T.S, E.Z., and J.J.; data curation, D.K. and K.N.; writing—original draft preparation, D.K.; writing—review and editing, K.N. T.S, and J.J.; visualization, D.K., T.S, E.Z., and J.J.; supervision, D.K.; project administration, K.N.; funding acquisition, K.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science Centre (Poland), grant no. 2019/35/N/NZ9/01795.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| a* |

Red/Green coordinate |

| AA |

Ascorbic Acid |

| AP |

Ascorbyl Palmitate |

| AV |

Acid Value |

| b* |

Yellow/Blue coordinate |

| CFE |

Coating-Forming Emulsion |

| DPPH* |

2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical |

| GAR |

Gum Arabic |

| GEL |

Gelatin |

| L* |

Lightness |

| MC |

Moisture Content |

| PV |

Peroxide Value |

| Rq |

Root-Mean-Square Roughness |

| TBARS |

Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances |

| WL |

Weight Loss |

| η |

Viscosity |

References

- European Commission. EU actions against food waste. Food Safety—Food Waste. European Commission. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/food-safety/food-waste/eu-actions-against-food-waste_en (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- European Commission. Research and innovation for food waste prevention and reduction at household level through measurement, monitoring and new technologies (HORIZON-CL6-2025-02-FARM2FORK-04-two-stage). CORDIS – EU Research Results. European Union. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/programme/id/HORIZON_HORIZON-CL6-2025-02-FARM2FORK-04-two-stage (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Laguerre, M.; Bayrasy, C.; Panya, A.; Weiss, J.; McClements, D.J.; Lecomte, J.; Decker, E.A.; Villeneuve, P. What Makes Good Antioxidants in Lipid-Based Systems? The Next Theories Beyond the Polar Paradox. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 55, 183–201. [CrossRef]

- Mukwevho, P.L.; Kaseke, T.; Fawole, O.A. Innovations in Biodegradable Packaging and Edible Coating of Shelled Temperate Nuts. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2025, 18, 7763–7794. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, B.; Pinto, T.; Aires, A.; Morais, M.C.; Bacelar, E.; Anjos, R.; Ferreira-Cardoso, J.; Oliveira, I.; Vilela, A.; Cosme, F. Composition of nuts and their potential health benefits—an overview. Foods 2023, 12, 942.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. FoodData Central. 2019. Available online: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/ (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Kowalczyk, D.; Zięba, E.; Skrzypek, T.; Baraniak, B. Effect of carboxymethyl cellulose/candelilla wax coating containing ascorbic acid on quality of walnut (Juglans regia L.) kernels. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 52, 1425–1431. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, C.M.; Salgado, P.R.; Dufresne, A.; Mauri, A.N. Microfibrillated cellulose addition improved the physicochemical and bioactive properties of biodegradable films based on soy protein and clove essential oil. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 79, 416–427. [CrossRef]

- Łupina, K.; Kowalczyk, D.; Drozłowska, E. Polysaccharide/gelatin blend films as carriers of ascorbyl palmitate – A comparative study. Food Chem. 2020, 333, 127465. [CrossRef]

- Galus, S.; Kadzińska, J. Food applications of emulsion-based edible films and coatings. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 45, 273–283. [CrossRef]

- López-Martínez, A.; Rocha-Uribe, A. Antioxidant Hydrophobicity and Emulsifier type Influences the Partitioning of Antioxidants in the Interface Improving Oxidative Stability in O/W Emulsions rich in n-3 fatty acids. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2017, 121.

- Han, J.H.; Hwang, H.M.; Min, S.; Krochta, J.M. Coating of peanuts with edible whey protein film containing α-tocopherol and ascorbyl palmitate. J. Food Sci. 2008, 73, 349–355. [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, D.; Baraniak, B. Effect of candelilla wax on functional properties of biopolymer emulsion films - A comparative study. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 41, 195–209. [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, Z.; Banach, M.; Makara, A. Otrzymywanie białka niskotemperaturowego mocno żelującego (żelatyny) metodami chemicznymi. Chemik 2011, 65, 1085–1092.

- Benedini, L.; Messina, P. V.; Palma, S.D.; Allemandi, D.A.; Schulz, P.C. The ascorbyl palmitate-polyethyleneglycol 400-water system phase behavior. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 2012, 89, 265–270. [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, D. Biopolymer/candelilla wax emulsion films as carriers of ascorbic acid - A comparative study. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 52, 543–553. [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, D.; Kazimierczak, W.; Zięba, E.; Lis, M.; Wawrzkiewicz, M. Structural and physicochemical properties of glycerol-plasticized edible films made from pea protein-based emulsions containing increasing concentrations of candelilla wax or oleic acid. Molecules 2024, 29, 5998. [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, M.M.; Andolfi, A.; Nicoletti, R. Mycotoxin Contamination in Hazelnut: Current Status, Analytical Strategies, and Future Prospects. Toxins (Basel) 2023, 15, 99.

- K., B.P.; D., D.M. Nuts and grains: microbiology and preharvest contamination risks. Microbiol. Spectr. 2018, 6, 1128. [CrossRef]

- Commission Regulation (EC) No 1284/2002 of 15 July 2002 laying down the marketing standard for hazelnuts in shell. Official Journal of the European Communities L 182, 25 July 2002, pp. 14–18. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32002R1284 (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Turan, A. Effect of drying on the chemical composition of Çakıldak (cv) hazelnuts during storage. Grasas y Aceites 2019, 70, 296. [CrossRef]

- Kenya Bureau of Standards. Hazelnut Kernels—Specification (Kenya Standard DKS 2992:2023). First ed. Kenya Bureau of Standards: Nairobi, Kenya, 2023. Available online: https://www.kebs.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Hazelnut-Kernels-Specification-1.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Razavi, R.; Maghsoudlou, Y.; Aalami, M.; Ghorbani, M. Impact of carboxymethyl cellulose coating enriched with Thymus vulgaris L. extract on physicochemical, microbial, and sensorial properties of fresh hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) during storage. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, 15313. [CrossRef]

- Ghirardello, D.; Contessa, C.; Valentini, N.; Zeppa, G.; Rolle, L.; Gerbi, V.; Botta, R. Effect of storage conditions on chemical and physical characteristics of hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.). Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 81, 37–43. [CrossRef]

- Guiné, R.P.F.; Almeida, C.F.F.; Correia, P.M.R. Influence of packaging and storage on some properties of hazelnuts. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2015, 9, 11–19. [CrossRef]

- Correia, P.; Filipe, A.; Ferrão, A.C.; Ramalhosa, E.; Guiné, R.P.F. Effect of moisture on the characteristics of hazelnut kernel during storage. In Proceedings of the Livro de Resumos do XVI Encontro de Química dos Alimentos: Bio-Sustentabilidade e Bio-Segurança Alimentar; 2022; p. 104.

- Pfeil, J.A.; Zhao, Y.; McGorrin, R.J. Chemical composition, phytochemical content, and antioxidant activity of hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) skins from Oregon. LWT 2024, 201, 116204. [CrossRef]

- Pycia, K.; Kapusta, I.; Jaworska, G. Changes in Antioxidant Activity, Profile, and Content of Polyphenols and Tocopherols in Common Hazel Seed (Corylus avellana L.) Depending on Variety and Harvest Date. Molecules 2020, 25, 43.

- Alasalvar, C.; Karamać, M.; Amarowicz, R.; Shahidi, F. Antioxidant and antiradical activities in extracts of hazelnut kernel (Corylus avellana L.) and hazelnut green leafy cover. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 4826–4832. [CrossRef]

- Król, K.; Gantner, M.; Piotrowska, A.; Hallmann, E. Effect of climate and roasting on polyphenols and tocopherols in the kernels and skin of six hazelnut cultivars (Corylus avellana L.). Agriculture 2020, 10, 36.

- Ingram, L.O.; Buttke, T.M. Effects of alcohols on micro-organisms. In Advances in Microbial Physiology; Rose, A.H., Tempest, D.W.B.T.-A. in M.P., Eds.; Academic Press, 1985; Vol. 25, pp. 253–300.

- Dobarganes, C.; Márquez-Ruiz, G. Rancidity in Nuts: Mechanisms and Control. Food Rev. Int. 1999, 15, 309–333. [CrossRef]

- Gull, A.; Masoodi, F.A.; Masoodi, L.; Gani, A.; Muzaffar, S. Effect of sodium alginate coatings enriched with α-tocopherol on quality of fresh walnut kernels. Food Chem. Adv. 2023, 2, 100169. [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, M.; Dastjerdi, A.M.; Shakerardekani, A.; Mirdehghan, S.H. Effect of alginate coating enriched with Shirazi thyme essential oil on quality of the fresh pistachio (Pistacia vera L.). J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 34–43. [CrossRef]

- Habashi, R.; Zomorodi, S.; Talaie, A.; Jari, S. Effects of chitosan coating enriched with thyme essential oil and packaging methods on a postharvest quality of Persian walnut under cold storage. Foods Raw Mater. 2019, 7, 18–25. [CrossRef]

- Sabaghi, M.; Maghsoudlou, Y.; Khomeiri, M.; Ziaiifar, A.M. Active edible coating from chitosan incorporating green tea extract as an antioxidant and antifungal on fresh walnut kernel. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2015, 110, 224–228. [CrossRef]

- Seyhan, F.; Tijskens, L.M.M.; Evranuz, O. Modelling temperature and pH dependence of lipase and peroxidase activity in Turkish hazelnuts. J. Food Eng. 2002, 52, 387–395. [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, D.; Karaś, M.; Kazimierczak, W.; Skrzypek, T.; Wiater, A.; Bartkowiak, A.; Basiura-Cembala, M. A Comparative study on the structural, physicochemical, release, and antioxidant properties of sodium casein and gelatin films containing sea buckthorn oil. Polymers (Basel) 2025, 17, 320. [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, D.; Karaś, M.; Kordowska-Wiater, M.; Skrzypek, T.; Kazimierczak, W. Inherently acidic films based on chitosan lactate-doped starches and pullulan as carries of nisin: A comparative study of controlled-release and antimicrobial properties. Food Chem. 2023, 404, 134760. [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 660:2020 – Animal and Vegetable Fats and Oils—Determination of Acid Value and Acidity; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 3960:2017 – Animal and Vegetable Fats and Oils—Determination of Peroxide Value; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Pegg, R.B. Spectrophotometric Measurement of Secondary Lipid Oxidation Products. Curr. Protoc. Food Anal. Chem. 2001, 1, D2.4.1-D2.4.18. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).