1. Introduction

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP), including chronic hypertension (CH) during pregnancy, gestational hypertension (GH), preeclampsia (PE), eclampsia, and Hemolysis, Elevated Liver Enzymes, Low Platelet Count (HELLP) syndrome impact one in six pregnancies.[

1] HDP are major contributors to maternal and infant morbidity and mortality, accounting for up to 40,000 maternal deaths and 500,000 fetal and newborn deaths annually.[

2] Despite their impact, clinical management of HDP remains limited, with delivery as the only definitive treatment.[

3]

The etiology of HDP is not fully understood; however, oxidative stress is a well-recognized contributor to hypertension and its systemic complications in both pregnant and non-pregnant individuals.[

4,

5] Increased oxidative stress promotes endothelial dysfunction, an early indicator of impaired vasoreactivity and contributor to HDP pathophysiology.[

4] Although a pro-oxidant environment is necessary for normal placental development and parturition, the sustained systemic vasoconstriction observed in HDP from excessive oxidative stress contributes to placental hypoperfusion and altered vascular development.[

6,

7,

8] In HDP, arterial remodeling of the decidual vessels can lead to high-pressure, pulsatile blood flow to the placenta and fetus, exacerbating hypertension and increasing the risk of severe conditions such as PE, eclampsia, and HELLP syndrome.[

9]

Antioxidants are mitigators of oxidative stress. While the human body can produce endogenous antioxidants in response to oxidative stress, dietary intake serves as a crucial source of exogenous antioxidants.[

10] Antioxidative nutrients, including carotenoids, have demonstrated therapeutic benefits in conditions characterized by inflammation and oxidative stress.[

11] Carotenoids are pigmented tetraterpene derivatives found in plants and algae, but importantly, are not synthesized by humans.[

12] Although over 750 carotenoids have been identified in nature, only about 40 are commonly consumed in the human diet, with α-carotene, β-carotene, lycopene, lutein, and β-cryptoxanthin accounting for nearly 90% of dietary intake.[

13,

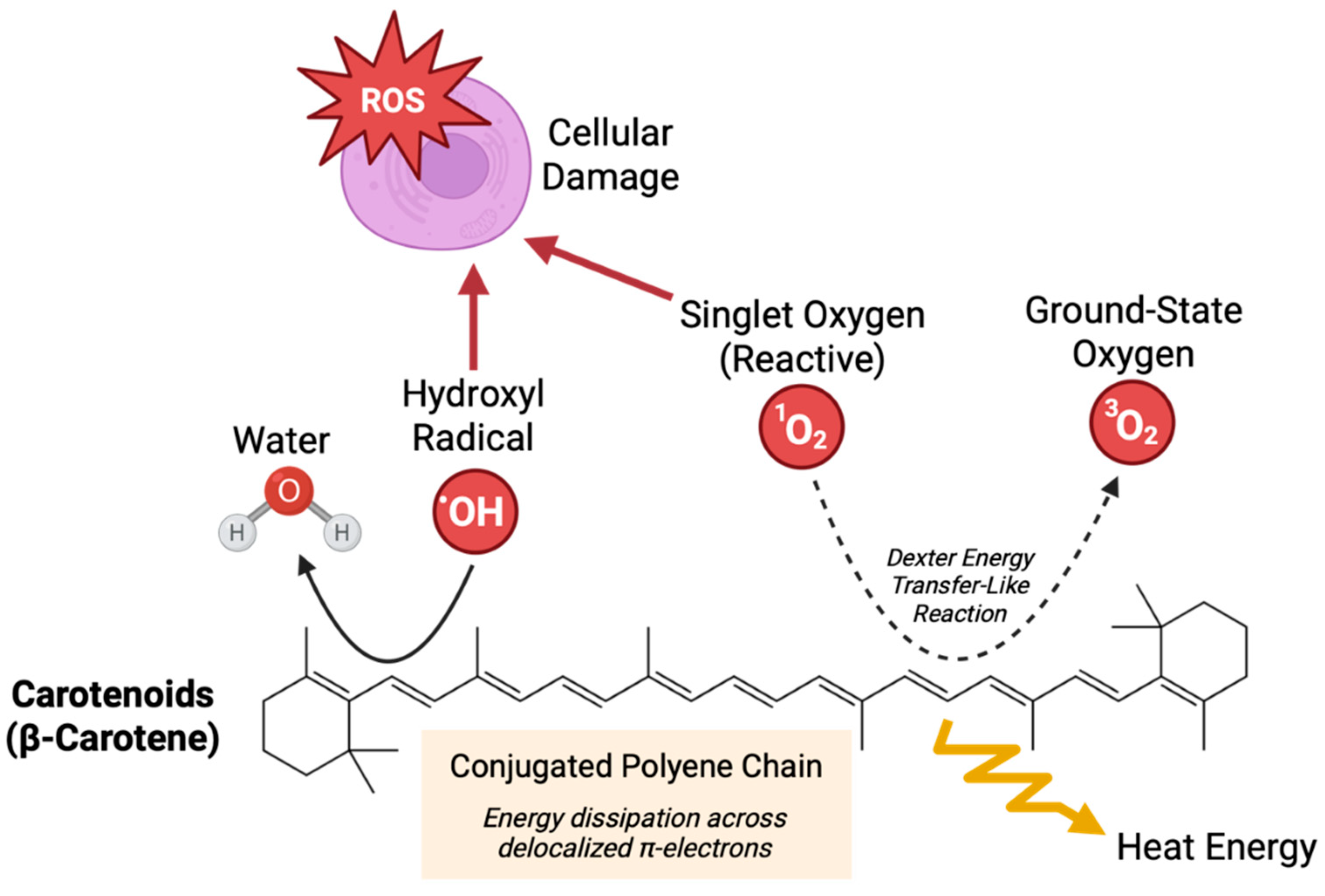

14] Carotenoids play diverse biological roles, including modulating inflammation and protecting cells from oxidative stress by neutralizing free radicals and singlet oxygen (

Figure 1).[

12]

Carotenoid status in humans has been associated with lower blood pressure, and studies have reported reduced carotenoid levels in both maternal plasma and placentae in women with PE.[

15,

16,

17,

18] Although carotenoids are increasingly recognized as nutrients with important roles in inflammatory regulation and fetal development, their relationship with HDP has not been fully elucidated. To address this gap, we conducted a retrospective cohort analysis evaluating self-reported maternal dietary carotenoid intake and quantified plasma carotenoid levels in NT, CH, GH, and PE pregnancies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participant Enrollment

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of Nebraska Medical Center Institutional Review Board (IRB #112-15-EP). Patients provided informed, written consent prior to enrollment in this study. Inclusion criteria included women ≥19 years old admitted to the Labor and Delivery Unit at Nebraska Medicine (Omaha, NE, USA) who delivered at least one live-born infant. Exclusion criteria included infants who were deemed Ward of the State and mothers with diseases affecting normal nutrient metabolism, including gastrointestinal, liver, and kidney diseases and genetic metabolic disorders.

2.2. Dietary Questionnaires

Trained study personnel administered demographic questionnaires and the Harvard Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) to maternal participants.[

19] De-identified FFQs were analyzed by the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health to quantify average daily intake of carotenoids from foods and supplements.

2.3. Clinical Data Collection

Clinical data was obtained from the maternal electronic medical record. The hypertensive status of the mother was determined using 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines.[

20] Participants were classified as having PE if a formal diagnosis was noted in the electronic medical record by Nebraska Medicine obstetricians. The final HDP classifications included NT, CH, GH, or PE.

2.4. Blood Sample Collection

The Maternal blood was collected in K2 EDTA tubes during routine clinical care. The research team received blood samples leftover from clinical blood draws. Whole blood samples were protected from heat and light, separated into plasma and red blood cell components by centrifugation, and frozen at -80 C within 12 hours of collection per the World Health Organization guidelines to preserve nutrient integrity.[

21]

2.5. Carotenoid Analysis

Plasma samples were analyzed for carotenoids (α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, combined lutein + zeaxanthin, and lycopene). The Biomarker Research Institute at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health analyzed samples using High Performance Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (HPLC-MS) as described by Thoene et al.[

22] NIST standards were utilized to receive quality control in both labs.[

23]

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, were calculated. The normality of continuous variables was assessed by skewness tests. Statistical differences between continuous maternal demographics data were assessed using Kruskal-Wallis tests. Statistical differences between categorical maternal demographics variables were assessed using chi-squared tests. Statistical differences between dietary intake and blood levels of carotenoids were assessed using Kruskal-Wallis tests with Dunn’s post-hoc multiple comparisons tests. Summary and comparative statistics of demographics data were performed using Stata 18.5. Statistical analyses and visualization of dietary intake and blood levels of carotenoids was performed using GraphPad Prism 10. The threshold of significance was set at p-value < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Maternal Demographics

A total of 488 maternal participants were included in this analysis, of which 270 (55%) were NT, 61 (13%) had CH, 102 (21%) had GH, and 55 (11%) had PE. The demographic characteristics of participants were broadly representative of the patient population served at the study site. The age of participants was similar between groups, with averages ranging from 28.6 to 29.6 years. Pre-pregnancy BMI was significantly different between groups, with the lowest BMI averages in the NT and CH groups at 28.3 kg/m2 and the highest in the PE group at 33.1 kg/m2. Average BMIs for all groups fell within the overweight (25-29.9) and obese (>30) ranges, consistent with published population demographics for Nebraska women age 20-39 years.[

24] The majority of participants identified as white and there were no significant differences in racial composition between HDP groups. Most participants were multiparous at the time of recruitment, although there was a statistically significant difference in parity noted across HDP groups, potentially owing to the higher percentage of nulliparous women in the PE group. There were no significant differences in maternal diabetes status or smoking status between HDP groups. Pregnancy duration was significantly different between HDP groups, with the shortest period in the PE group at 36.4 weeks and the longest in the CH group at 38.9 weeks.

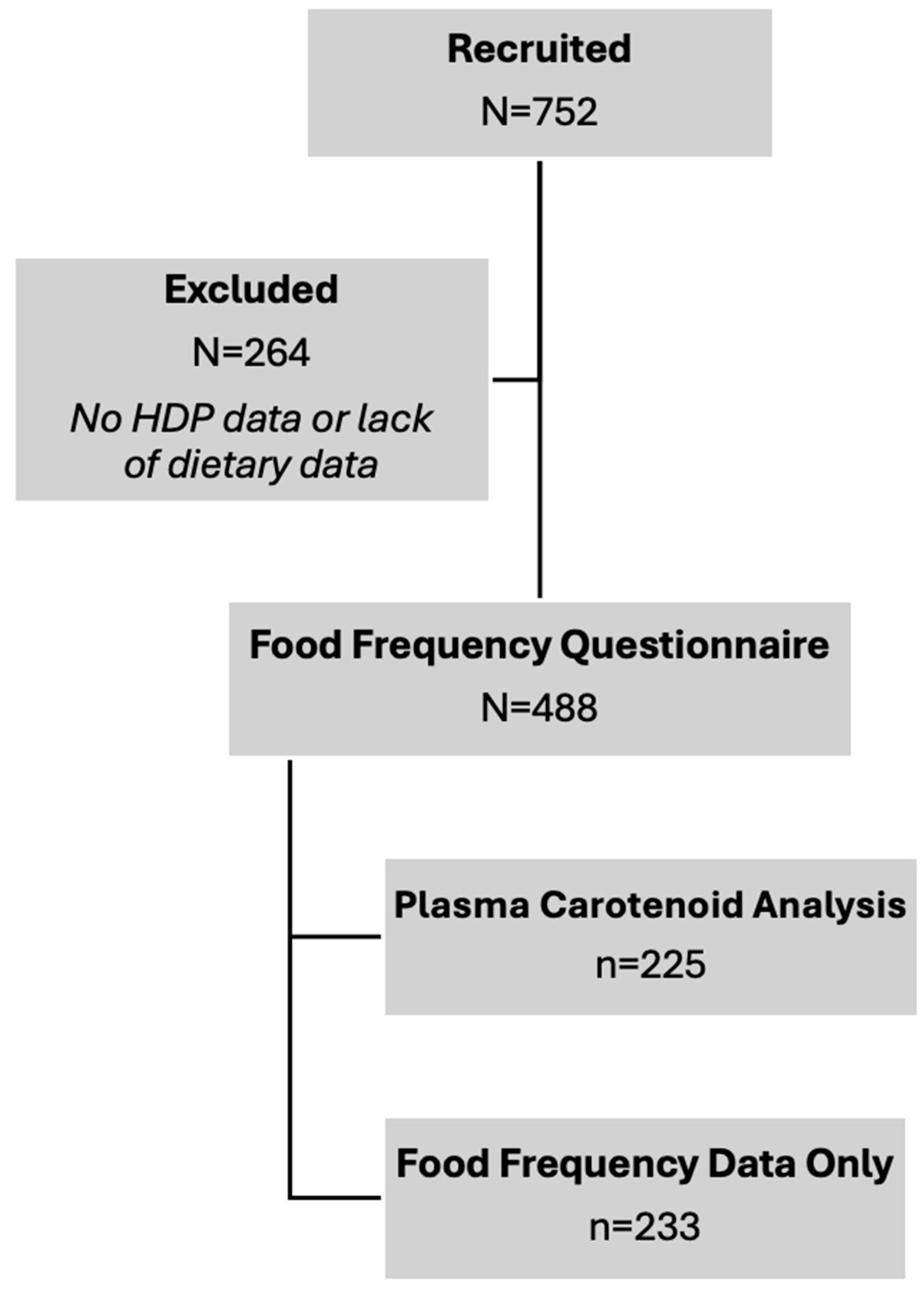

Figure 2.

Study Flowchart for Subject Recruitment and Analyses. Final sample sizes for carotenoid dietary intake and blood levels are contained.

Figure 2.

Study Flowchart for Subject Recruitment and Analyses. Final sample sizes for carotenoid dietary intake and blood levels are contained.

Table 1.

Demographics Information.

Table 1.

Demographics Information.

| |

NT (N=270) |

CH (N=61) |

GH (N=102) |

PE (N=55) |

p-value |

Age

(years; median, inner quartiles)

|

30 (25-33) |

30 (25-33) |

30 (25-34) |

28 (23-34) |

0.7000 |

Body Mass Index

(kg/m2; median, inner quartiles)

|

27.3 (23.4-31.8) |

26.8 (22.4-33.2) |

28.0 (22.9-32.4) |

34.2 (25.7-38.8) |

0.0007 |

| Race (N, %) |

|

|

|

|

0.295 |

| White |

180 (66.9%) |

46 (75.4%) |

73 (71.6%) |

37 (67.3%) |

|

| African American |

40 (14.9%) |

6 (9.8%) |

9 (8.8%) |

8 (14.6%) |

|

| Hispanic |

22 (8.2%) |

2 (3.3%) |

7 (6.7%) |

3 (5.5%) |

|

| Asian or Pacific Islander |

6 (2.2%) |

3 (4.9%) |

1 (1.0%) |

2 (3.6%) |

|

| American Indian |

- |

1 (1.6%) |

- |

- |

|

| Other/Unknown |

21 (7.8%) |

3 (4.9%) |

12 (11.8%) |

5 (9.1%) |

|

| Parity (N, %) |

|

|

|

|

0.024 |

| Nulliparous |

31 (11.5%) |

4 (6.6%) |

11 (10.8%) |

14 (25.5%) |

|

| Primiparous |

83 (30.7%) |

24 (39.3%) |

37 (36.3%) |

20 (36.4%) |

|

| Multiparous |

156 (57.8%) |

33 (54.1%) |

54 (52.9%) |

21 (38.2%) |

|

| Diabetes (N, %) |

34 (12.6%) |

4 (6.6%) |

10 (9.8%) |

11 (20.0%) |

0.135 |

| Smoking (N, %) |

|

|

|

|

0.297 |

| Current |

28 (10.4%) |

5 (8.2%) |

7 (6.9%) |

5 (9.1%) |

|

| Former |

32 (11.9%) |

5 (8.2%) |

17 (16.7%) |

12 (21.2%) |

|

Pregnancy Duration

(weeks; median, inner quartiles)

|

39.3 (38.4-40.2) |

39.4 (38.3-40.4) |

39.2 (38-40.3) |

37 (34.1-38.6) |

0.0001 |

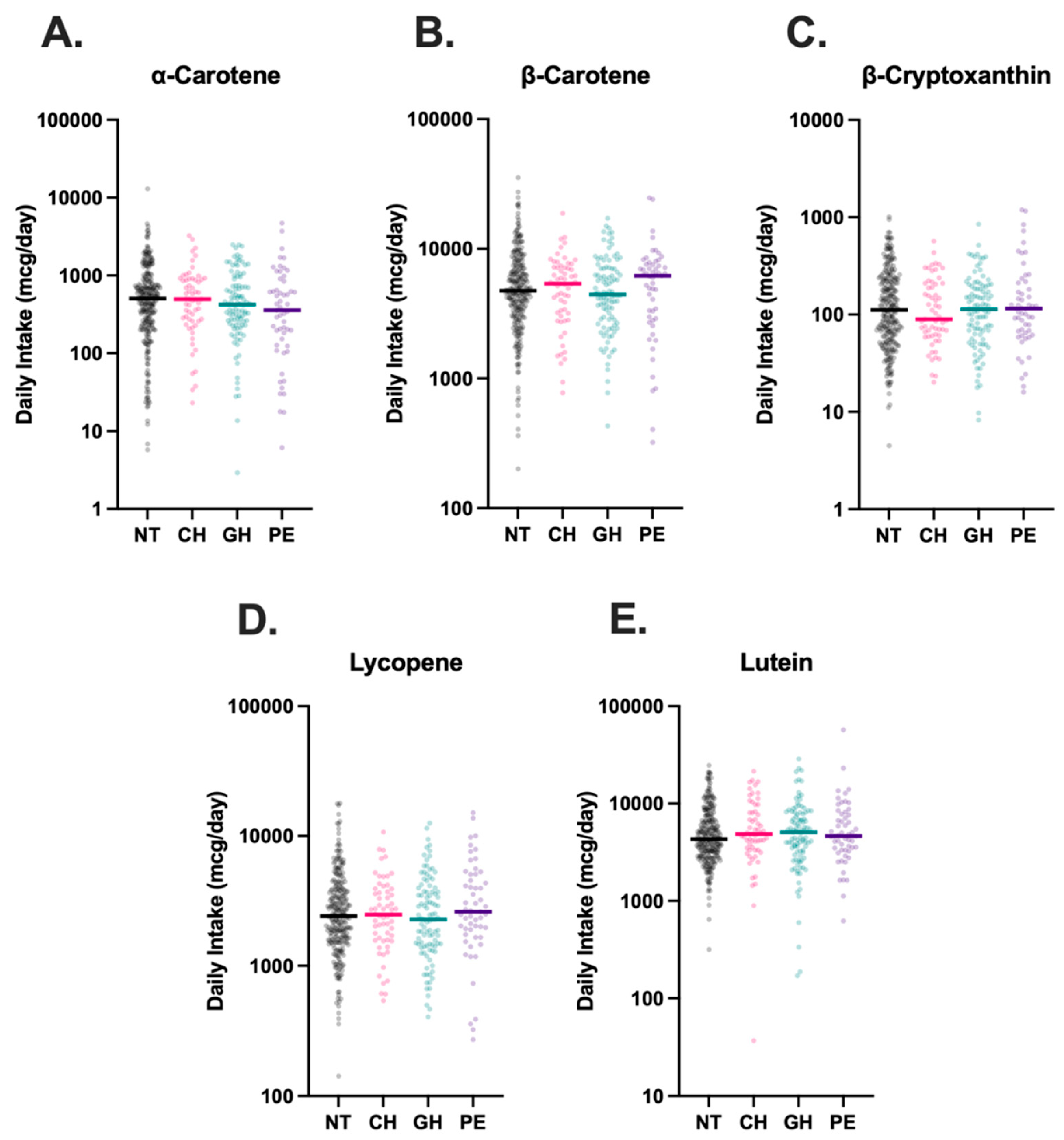

3.2. Dietary Carotenoid Intake

Dietary intake data was available for all 488 participants. Comparison of self-reported carotenoid intake across groups revealed no statistically significant differences between NT, CH, GH, and PE groups (

Figure 3).

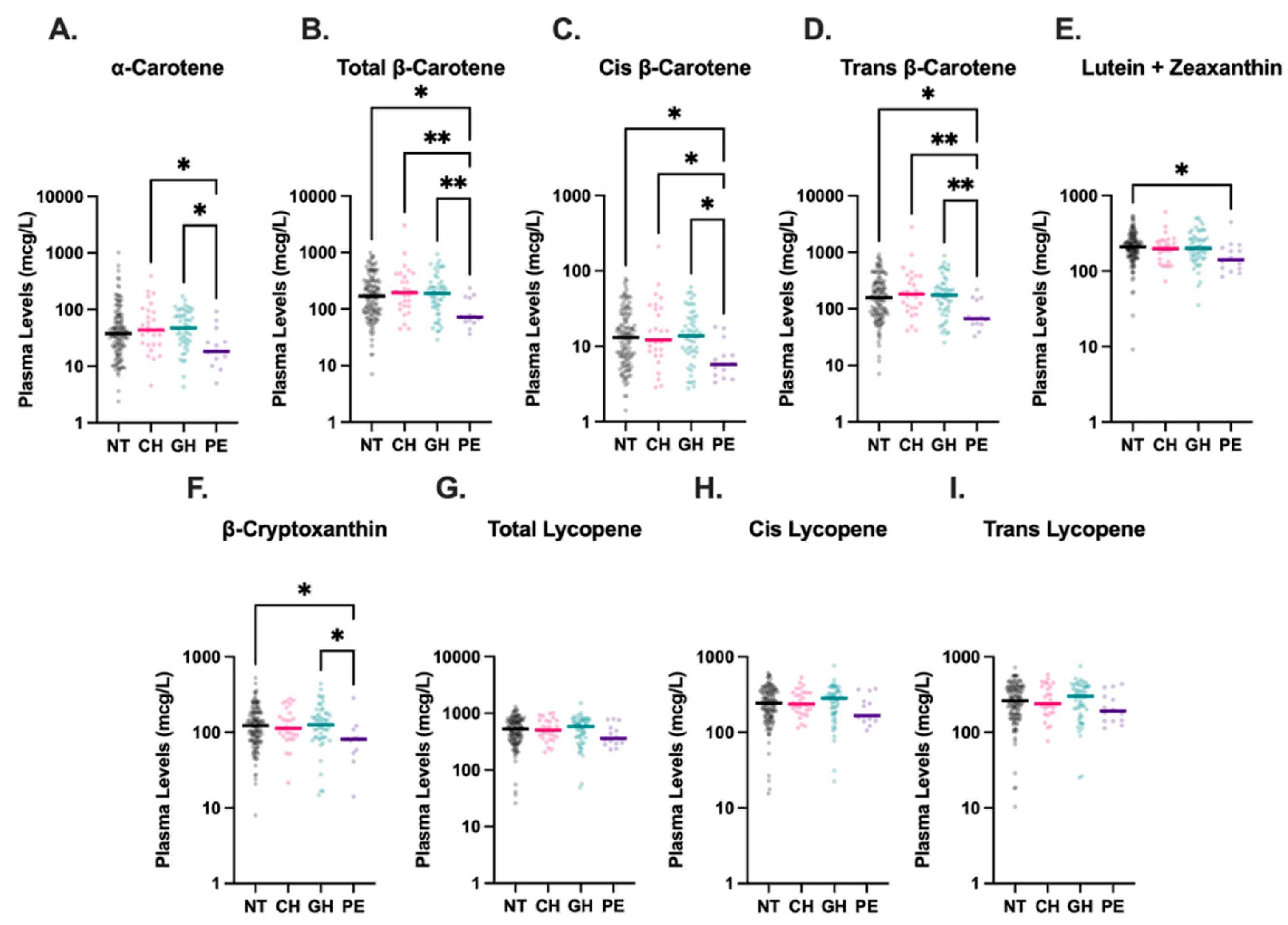

3.3. Plasma Carotenoid Concentrations

Maternal plasma carotenoid levels were available for 225 of the 488 participants, as detailed in

Figure 2, although levels of cis-β-carotene were undetectable in three analyzed plasma samples. Compared to all other HDP groups, women with PE had significantly lower plasma levels of total-β-carotene, cis-β-carotene, and trans-β-carotene (

Figure 4). The median concentration of total-β-carotene in the PE group was less than half that observed in the NT group (72.5 mcg/L vs. 169.9 mcg/L, p=0.01). Similarly, the median concentration of cis-β-carotene in PE was less than half of that in NT (5.8 mcg/L vs. 12.9 mcg/L, p=0.01), and trans-β-carotene levels in PE were also markedly lower than in NT (67.1 mcg/L vs. 157.6 mcg/L, p=0.01). Levels of total-β-carotene, cis-β-carotene, and trans-β-carotene were similar among NT, CH, and GH groups, with levels in CH and GH groups also significantly higher than those in PE. Combined lutein + zeaxanthin and β-cryptoxanthin levels were also lower in the PE group compared to the NT group (208.6 mcg/L vs. 141.6 mcg/L, p=0.049 and 123.5 mcg/L vs. 81.1 mcg/L, p=0.048, respectively), although the differences were not as drastic. Levels of β-cryptoxanthin were also significantly lower in PE compared to GH (p=0.02). No significant differences were detected among levels of total, cis-, or trans-lycopene in HDP groups.

4. Discussion

Authors To our knowledge, this is the first study to specifically assess plasma carotenoid status across HDP subtypes. We report significantly decreased levels of previously uncharacterized cis and trans β-carotene isoforms in maternal plasma from pregnancies complicated by PE compared to NT pregnancies. While previous studies have reported lower total β-carotene levels in PE, our results uniquely highlight isoform-specific reductions.[

17,

18,

25] Our results also corroborate the findings of previous studies characterizing decreased plasma levels of lutein and β-cryptoxanthin in PE compared to NT pregnancies.[

16] Although, interestingly, we did not observe statistically significant differences between α-carotene or lycopene levels in PE and NT, which have been demonstrated in other studies.[

18,

26]

Our study was unique in its inclusion of other HDP, such as CH and GH, in addition to PE. Despite this broader inclusion, we did not observe significant associations between carotenoid levels and these other HDP subtypes. This distinction may point toward fundamental differences in redox state between PE and other HDP conditions. The increased oxidative stress characteristic of PE may lead to greater consumption of carotenoids in the process of quenching ROS, resulting in lower circulating levels.[

4,

27] In contrast, the oxidative stress present in CH or GH may not be as severe, and thus, may not exert a measurable impact on plasma carotenoid levels. This hypothesis is supported by the significantly lower plasma α-carotene, β-carotene, and β-cryptoxanthin in PE compared to GH and CH, which both fall on the HDP spectrum, but have notably milder clinical features than PE.

Clinical trials evaluating carotenoid supplementation, specifically lycopene supplementation, have not demonstrated meaningful benefit in preventing PE.[

28] However, this is important to consider in the context that our data show no significant differences in plasma lycopene levels between NT and PE groups. It is possible that other carotenoids, or more likely, a synergism of multiple carotenoids could have meaningful clinical impacts in reducing PE occurrence if supplemented during early pregnancy. However, the relationship between carotenoid status and PE risk may be more complex than intake alone. Despite lower levels of plasma carotenoids in our PE group, our dietary intake data did not reveal reduced carotenoid intake among individuals with PE compared to any other HDP group, which was true of both total intake and intake without supplements (

Supplementary Figure 1). This differs from previous studies, such as Kang et al., who reported an association between decreased dietary intake of β-carotene and lutein + zeaxanthin and the development of PE.[

29] Notably, we found no meaningful correlations between maternal dietary carotenoid intake and measured plasma levels except for α-carotene (

Supplementary Figure 2). While dietary intake data were self-reported, this observation suggests that reduced intake may not fully explain the lower carotenoid levels observed in PE. Several factors are known to influence carotenoid bioavailability, including lipid absorption, gut microbiota composition, genetic polymorphisms, and dietary fat co-ingestion, which may also contribute to PE.[

13,

30,

31,

32]

Other studies have evaluated maternal plasma carotenoid levels during PE as biomarkers for the redox environment, with evidence suggesting that mid-pregnancy α-carotene, β-carotene, and lutein plasma levels may be suitable targets.[

26] Our data also support the utility of carotenoids as markers of PE, but with notable caveats, including assessment at delivery and incompletely characterized trends in plasma carotenoid levels over the course of pregnancy. There are known positive correlations between gestational age and maternal plasma carotenoid concentrations, which were also observed in our dataset (

Supplementary Figure 3).[

23] However, it remains unclear whether this relationship is prognostic for earlier delivery or variation in carotenoid metabolism over gestation.[

23] To clarify this, future studies should consider serial measurement of maternal carotenoids throughout pregnancy to better define their temporal dynamics and potential utility as early indicators for the risk of developing HDP.

Our study was limited by sample size, which reduced statistical power and precluded the use of robust multivariate regression models. We acknowledge that our PE sample size, in particular, was limited, with as few as fourteen participants in plasma carotenoid analyses. Adjusted regression models are sensitive to overfitting when the number of covariates exceeds the degrees of freedom allowed by the sample size, as in our dataset.[

33] Adjusted analyses would have strengthened our interpretations, as factors such as obesity, parity, and maternal age are known to influence HDP risk.[

34,

35] However, despite these limitations, our study had notable strengths, including the assessment of both dietary intake and plasma carotenoid levels, characterization of a broad spectrum of carotenoids, and the inclusion of under-studied HDP subtypes such as GH and CH during pregnancy. These findings contribute to the growing body of evidence implicating the role of carotenoids in the pathophysiology of PE and provide important distinctions between specific HDP categories. Future studies should evaluate the synergistic impact carotenoids in ameliorating oxidative states and the temporal dynamics of plasma carotenoid levels during pregnancy to assess the utility of carotenoids as therapeutic targets and biomarkers for PE.

5. Conclusions

Maternal plasma carotenoids, including β-carotene, lutein + zeaxanthin, and β-cryptoxanthin were lower in PE compared to NT. Plasma α-carotene, β-carotene, and β-cryptoxanthin were also lower in PE compared to GH, and plasma α-carotene and β-carotene was lower in PE compared to CH. These data may indicate that PE is a unique redox state compared to other HDP, potentially requiring greater quantities of carotenoids to quench ROS. Despite differences in plasma carotenoid levels, dietary intake of carotenoids did not differ between HDP groups, indicating that intake is not the exclusive determinant of carotenoid levels. These observations highlight the role of carotenoids in PE, specifically. Clarifying whether and how carotenoid status influences PE risk will require mechanistic and longitudinal studies across pregnancy.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: Dietary Intake of Carotenoids Without Supplementation in HDP.; Figure S2: Maternal Plasma Carotenoid Levels Compared to Dietary Carotenoid Intake.; Figure S3: Maternal Plasma Carotenoid Levels Compared to Gestational Age.; Analysis Files and Raw Data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S., M.K.T., C.K.H., A.L.A.B; methodology, C.I.F., M.K.T., C.K.H., and A.L.A.B.; validation, E.L., M.K.T, C.K.H., and A.L.A.B.; formal analysis, C.I.F. and E.L. ; investigation, C.I.F. and J.S.; resources, P.K.M. and A.L.A.B.; data curation, C.I.F., J.S., R.A.D., M.V.O., M.K.T., C.K.H, and A.L.A.B. ; writing—original draft preparation, C.I.F. and J.S.; writing—review and editing, C.I.F., R.A.D., M.V.O, M.K.T., P.K.M., C.K.H., and A.L.A.B.; visualization, C.I.F.; supervision, P.K.M. and A.L.A.B.; project administration, M.V.O.; funding acquisition, P.K.M. and A.L.A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding for research time and facilities from the National Institutes of Health grants R56HL156806, UNMC Collaboration Initiative grant, Child Health Research Institute research grant, and Buffett Early Childhood Institute Graduate Scholars program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Nebraska Medical Center (IRB # 0166-21-EP, December 14th, 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

De-identified data and analysis files are provided in the

supplementary materials. The authors can provide data in alternative formats upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge care providers in the University of Nebraska Medical Center Labor and Delivery unit and technicians in the Blood Bank, who were instrumental in supporting our clinical research initiatives. We acknowledge the use of BioRender to generate

Figure 1.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HDP |

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy |

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

| GH |

Gestational hypertension |

| CH |

Chronic hypertension |

| PE |

Preeclampsia |

| NT |

Normotension |

| HELLP |

Hemolysis, Elevated Liver Enzymes, Low Platelet Count |

| FFQ |

Food Frequency Questionnaire |

References

- Cameron, N.A.; Everitt, I.; Seegmiller, L.E.; Yee, L.M.; Grobman, W.A.; Khan, S.S. Trends in the Incidence of New-Onset Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy Among Rural and Urban Areas in the United States, 2007 to 2019. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e023791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hladunewich, M.; Karumanchi, S.A.; Lafayette, R. Pathophysiology of the Clinical Manifestations of Preeclampsia. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007, 2, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinoza, J. Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 222. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, e237–e260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouache, R.; Biquard, L.; Vaiman, D.; Miralles, F. Oxidative Stress in Preeclampsia and Placental Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griendling, K.K.; Camargo, L.L.; Rios, F.J.; Alves-Lopes, R.; Montezano, A.C.; Touyz, R.M. Oxidative Stress and Hypertension. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 993–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gubory, K.H.; Fowler, P.A.; Garrel, C. The Roles of Cellular Reactive Oxygen Species, Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants in Pregnancy Outcomes. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2010, 42, 1634–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendhack, L.M. Contribution of Oxidative Stress to Endothelial Dysfunction in Hypertension. Front. Physiol. [CrossRef]

- Myatt, L.; Cui, X. Oxidative Stress in the Placenta. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2004, 122, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staff, A.C.; Fjeldstad, H.E.; Fosheim, I.K.; Moe, K.; Turowski, G.; Johnsen, G.M.; Alnaes-Katjavivi, P.; Sugulle, M. Failure of Physiological Transformation and Spiral Artery Atherosis: Their Roles in Preeclampsia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 226, S895–S906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, M.H. Significance of Dietary Antioxidants for Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 13, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaulmann, A.; Bohn, T. Carotenoids, Inflammation, and Oxidative Stress—Implications of Cellular Signaling Pathways and Relation to Chronic Disease Prevention. Nutr. Res. 2014, 34, 907–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crupi, P.; Faienza, M.F.; Naeem, M.Y.; Corbo, F.; Clodoveo, M.L.; Muraglia, M. Overview of the Potential Beneficial Effects of Carotenoids on Consumer Health and Well-Being. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmarchelier, C.; Borel, P. Overview of Carotenoid Bioavailability Determinants: From Dietary Factors to Host Genetic Variations. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 69, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assessment of Dietary Carotenoid Intake and Biologic Measurement of Exposure in Humans. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 255–295 ISBN 978-0-323-91351-5.

- Abbasian, F.; Alavi, M.S.; Roohbakhsh, A. Dietary Carotenoids to Improve Hypertension. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M. Plasma Carotenoids, Retinol, Tocopherols, and Lipoproteins in Preeclamptic and Normotensive Pregnant Zimbabwean Women. Am. J. Hypertens. 2003, 16, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, J.S.; Yuan, W.L.; Ong, C.N.; Tan, K.H.; Yap, F.; Chong, Y.S.; Gluckman, P.D.; Godfrey, K.M.; Lee, Y.S.; Chan, J.K.Y.; et al. Perinatal Plasma Carotenoid and Vitamin E Concentrations with Maternal Blood Pressure during and after Pregnancy. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2022, 32, 2811–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palan, P.R.; Mikhail, M.S.; Romney, S.L. Placental and Serum Levels of Carotenoids in Preeclampsia. 2001, 98. [CrossRef]

- Baer, H.J.; Blum, R.E.; Rockett, H.R.; Leppert, J.; Gardner, J.D.; Suitor, C.W.; Colditz, G.A. Use of a Food Frequency Questionnaire in American Indian and Caucasian Pregnant Women: A Validation Study. BMC Public Health 2005, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whelton, P.K.; Carey, R.M.; Aronow, W.S.; Casey, D.E.; Collins, K.J.; Dennison Himmelfarb, C.; DePalma, S.M.; Gidding, S.; Jamerson, K.A.; Jones, D.W.; et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, e127–e248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Micronutrient Survey Manual; 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2020; ISBN 978-92-4-001269-1.

- Thoene, M.; Anderson-Berry, A.; Van Ormer, M.; Furtado, J.; Soliman, G.A.; Goldner, W.; Hanson, C. Quantification of Lutein + Zeaxanthin Presence in Human Placenta and Correlations with Blood Levels and Maternal Dietary Intake. Nutrients 2019, 11, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, C.; Thoene, M.; Van Ormer, M.; Furtado, J.D.; Korade, Z.; Genaro-Mattos, T.C.; Hanson, C.; Anderson-Berry, A. Plasma Concentrations and Maternal-Umbilical Cord Plasma Ratios of the Six Most Prevalent Carotenoids across Five Groups of Birth Gestational Age. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, E.M.; Geske, J.A.; Khandalavala, B.N. Temporal Trends of Obesity Among Nebraska Adults: EMR Data Shows a More Rapid Increase Than Projected. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2024, 15, 21501319241301236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhail, M.S.; Anyaegbunam, A.; Garfinkel, D.; Palan, P.R.; Basu, J.; Romney, S.L. Preeclampsia and Antioxidant Nutrients: Decreased Plasma Levels of Reduced Ascorbic Acid, Alpha-Tocopherol, and Beta-Carotene in Women with Preeclampsia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1994, 171, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.M.; Kramer, M.S.; Platt, R.W.; Basso, O.; Evans, R.W.; Kahn, S.R. The Association between Maternal Antioxidant Levels in Midpregnancy and Preeclampsia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 213, 695.e1–695.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, T. Carotenoids and Markers of Oxidative Stress in Human Observational Studies and Intervention Trials: Implications for Chronic Diseases. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, S.; Jeyaseelan, S.; Guleria, R. Trial of Lycopene to Prevent Pre-eclampsia in Healthy Primigravidas: Results Show Some Adverse Effects. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2009, 35, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, T.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Huang, X.; Cao, Y.; Dou, W.; Duan, D.; Bo, Y.; Traore, S.S.; Zhao, X.; et al. Dietary Carotenoid Intake and Risk of Developing Preeclampsia: A Hospital-Based Case–Control Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, H.R.; Coelho, M.C.; Gomes, A.M.; Pintado, M.E. Carotenoids Diet: Digestion, Gut Microbiota Modulation, and Inflammatory Diseases. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lv, Y.; Ding, H. Dissecting the Roles of Lipids in Preeclampsia. Metabolites 2022, 12, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrmi, J.S.; Kaartokallio, T.; Lokki, A.I.; Jääskeläinen, T.; Kortelainen, E.; Ruotsalainen, S.; Karjalainen, J.; Ripatti, S.; Kivioja, A.; Laisk, T.; et al. Genetic Risk Factors Associated With Preeclampsia and Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. JAMA Cardiol. 2023, 8, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, F.E.; Lee, K.L.; Mark, D.B. MULTIVARIABLE PROGNOSTIC MODELS: ISSUES IN DEVELOPING MODELS, EVALUATING ASSUMPTIONS AND ADEQUACY, AND MEASURING AND REDUCING ERRORS. Stat. Med. 1996, 15, 361–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, S.A.; Savu, A.; Islam, S.; Ward, C.C.; Krasuski, R.A.; Grotegut, C.A.; Newby, L.K.; Hornberger, L.K.; Windram, J.; Kaul, P. Risk Factors and Outcomes Associated With Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy in Maternal Congenital Heart Disease. JACC Adv. 2022, 1, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Tian, Y.; Su, Z.; Sun, J.-Y.; Sun, W. Risk Factors and Prediction Model for New-Onset Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).