Submitted:

21 August 2025

Posted:

22 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Introduction

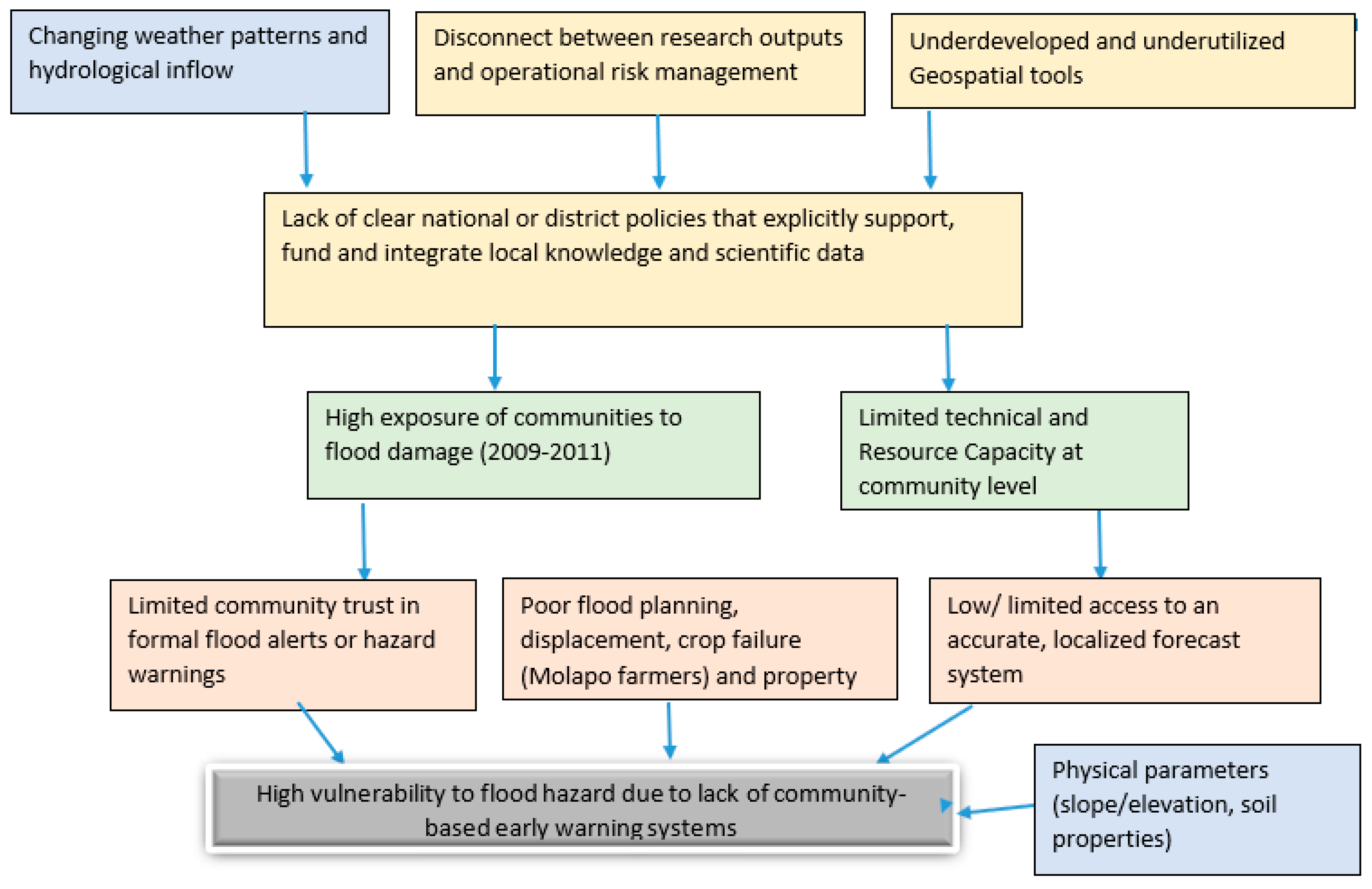

1.2. Statement of The Problem

1.3. Research Questions

- i.

-

General Research QuestionTo what extent have existing flood forecasting methods, techniques and tools been effective in predicting flood events in Ngamiland, and how are these predictions integrated into community-based risk management strategies?

- ii.

-

Specific Research Questions

- 1.

- What are the spatial characteristics of flood-prone areas in relation to soil physical properties?

- 2.

- How do local communities perceive and respond to flood forecasts and early warning systems?

- 3.

- What community-based risk management strategies exist and how are they aligned with scientific predictions/forecasts

- 4.

- How does the limited integration of local knowledge and scientific hydrological data affect flood predictability and community preparedness in the delta and what opportunities exist for improvement?

1.4. Research Objectives

- i.

-

General Research ObjectiveTo evaluate the disconnect between scientific flood forecasts and their integration in community-based risk management.

- ii.

-

Specific Research Objectives

- 1.

- To assess the predictive accuracy of remote sensing data and existing hydrological models in estimating flood extent through literature review.

- 2.

- To analyze the influence of soil-hydrological and topographic features on flood extent in floodplains and/or flood prone-areas.

- 3.

- To examine the level of community awareness, trust, and response to early warning systems during the 2009-2011 flood event and identify the existing community-based risk management strategies.

- 4.

- To explore the potential for integrating local knowledge and scientific data to create or improve existing community-based early warning systems.

1.5. Hypotheses

| Research Objective | Hypothesis |

| General Objective: To evaluate the disconnect between scientific flood forecasts and their integration in community-based risk management. | There is a significant disconnect between scientific forecasts and their integration into community-based risk management in Ngamiland. |

| Specific Objective 2: to analyze the influence of soil-hydrological and topographic features on flood extent in floodplains and/or flood prone-areas. | Soil properties, especially the physical, have a significant influence on flood-prone areas. |

| Objective 3: to examine the level of community awareness, trust, and response to early warning systems during the 2009-2011 flood event and identify the existing community-based risk management strategies. | Communities with higher awareness and trust in early warning systems are more likely to respond proactively and use local risk management strategies. |

| Objective 4: To explore the potential for integrating local knowledge and scientific data to create or improve existing community-based early warning systems. | There is a high potential for improving flood-preparedness outcomes by integrating local knowledge and scientific flood-forecasting tools. |

1.6. Justification for the Study

1.7. Scope of the Study

1.8. Operational definition of Concepts

- Flood Forecast Accuracy: refers to how closely the forecasted values of flood parameters (such as peak discharge, timing, or inundation extent) match the observed flood outcomes, as defined by the World Meteorological Organization (2011). It comprises of precision and reliability of predicting the occurrence, magnitude, timing, and duration of floods. Accurate flood forecasts enable timely and effective response measures to mitigate the impact of flooding. In this study, it refers to how well forecasts issued during the 2009-2011 period matched actual flood events.

- Community-Based Disaster Risk Management (CBDRM) is an approach and process of disaster risk management in which communities at risk are actively engaged in the identification, analysis, treatment, monitoring and evaluation of disaster risks in order to reduce their vulnerabilities and enhance their capacities to prevent and withstand damaging effects of hazards (the Maldives National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA).

- Early Warning Systems: defined by the UNDRR (2017) as an integrated system of hazard monitoring, forecasting and prediction, disaster risk assessment, communication and preparedness activities systems and processes that enables individuals, communities, governments, businesses and others to take timely action to reduce disaster risks in advance of hazardous events.

- Hydrological Modelling: involves the use of digital tools, techniques and methodologies to analyze data and create simulations of water movement, distribution, and quality through the components of the hydrological cycle. These models are essential for managing water resources, predicting flood events, maintaining ecosystem health, designing hydraulic structures, and in climate change studies (World Meteorological Organization, 2008).

- Geospatial Techniques and Tools: the technologies, applications, and methods used to gather, analyze, visualize and interpret spatial or geographical data, examples being Remote Sensing (RS) and Global Positioning Systems (GPS) and Geographic Information Systems (GIS). These are widely applied in flood mapping, environmental monitoring and disaster risk management (Goodchild, 2007; Lillesand, Kiefer, & Chipman, 2015).

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- EO: Earth Observation

- GIS: Geographic Information System

- SMI: Soil Moisture Index

- SWIR: Short Wave Infrared (band)

- MODIS: Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (Imagery)

2. Literature Review

2.1. Introduction

2.2. Empirical and Theoretical Perspectives

- I.

-

Global and Regional Perspectives on Flood Prediction and VulnerabilityFlood risk prediction has evolved with advances in hydrological modelling, remote sensing and machine learning techniques (Sharma & Machiwal, 2017). Globally, systems integrating soil hydrology, rainfall intensity and terrain analysis have improved short-term forecasts (Rahman, Ahmed & Haque, 2021). At regional level, sub-Saharan Africa has seen an increasing use of geospatial tools in modelling flood extent and vulnerability (CRED & UNDRR, 2015).Hillel (2004) showed that soil characteristics such as texture, porosity and moisture retention play a critical role in determining flood susceptibility. Additionally, Mercer, et al. (2012), showed that high bulk density and low infiltration rates increase surface runoff, particularly in flood-prone areas.

- II.

-

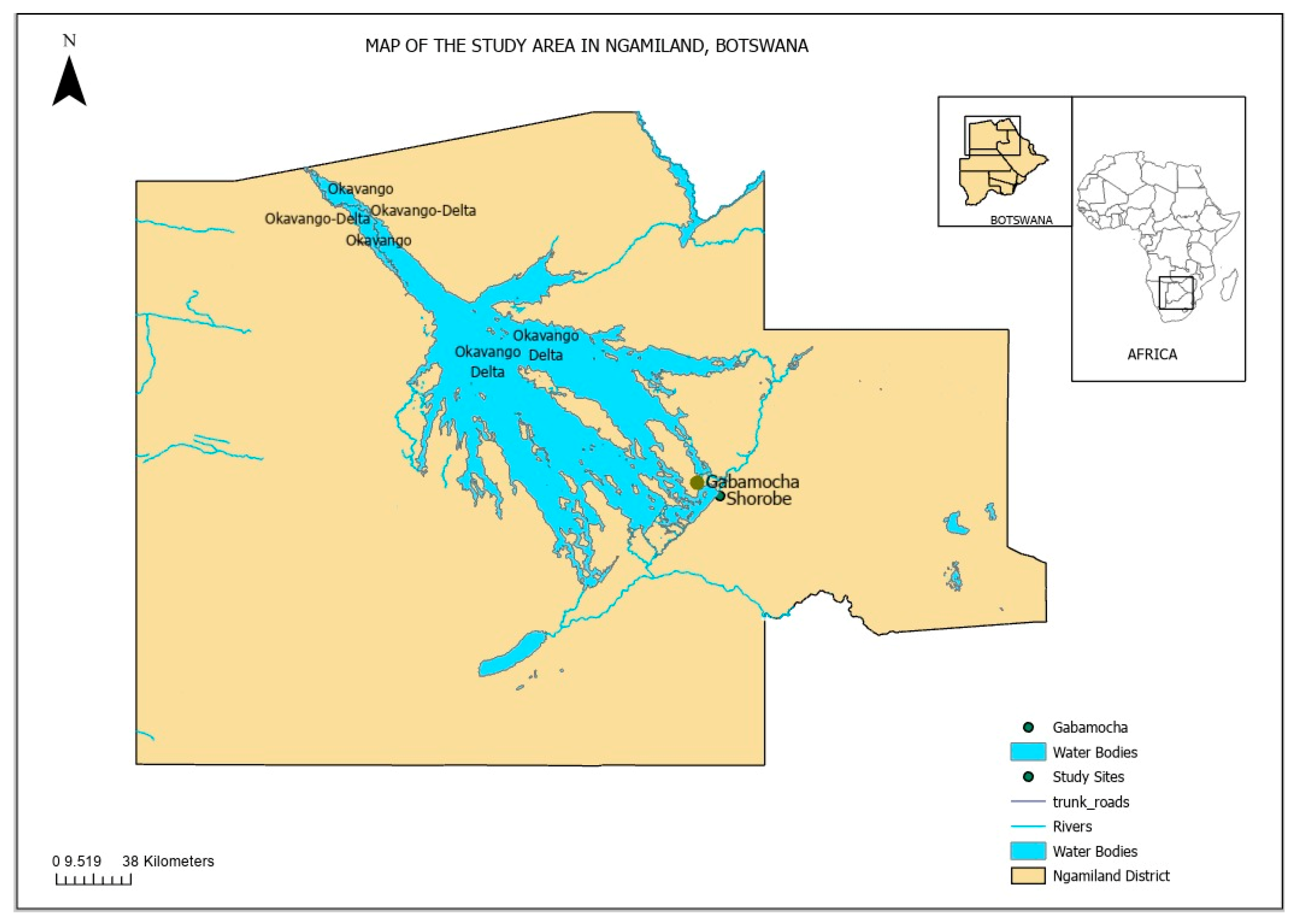

Flooding in the Okavango Delta: Local Experiences and StudiesThe Okavango Delta experiences seasonal flooding shaped by upstream rainfall in the Republic of Angola and the distributary dynamics of the delta’s channels. Flood events between the years 2009 and 2011 had significant socio-economic impacts, especially in Ngamiland district (Mmolawa et al., 2011, Motsholapheko et al., 2013). These studies found that community resilience was often restricted by limited access to early warnings and inadequate preparedness.Modeling efforts such as those by Wolski et al. (2006, 2007) and Tuito e al. (2016) demonstrated how integrating hydrodynamic models with satellite data can improve inundation mapping and prediction. However, their models often overlooked local soil characteristics, which significantly influence flood dynamics at micro level.

- III.

-

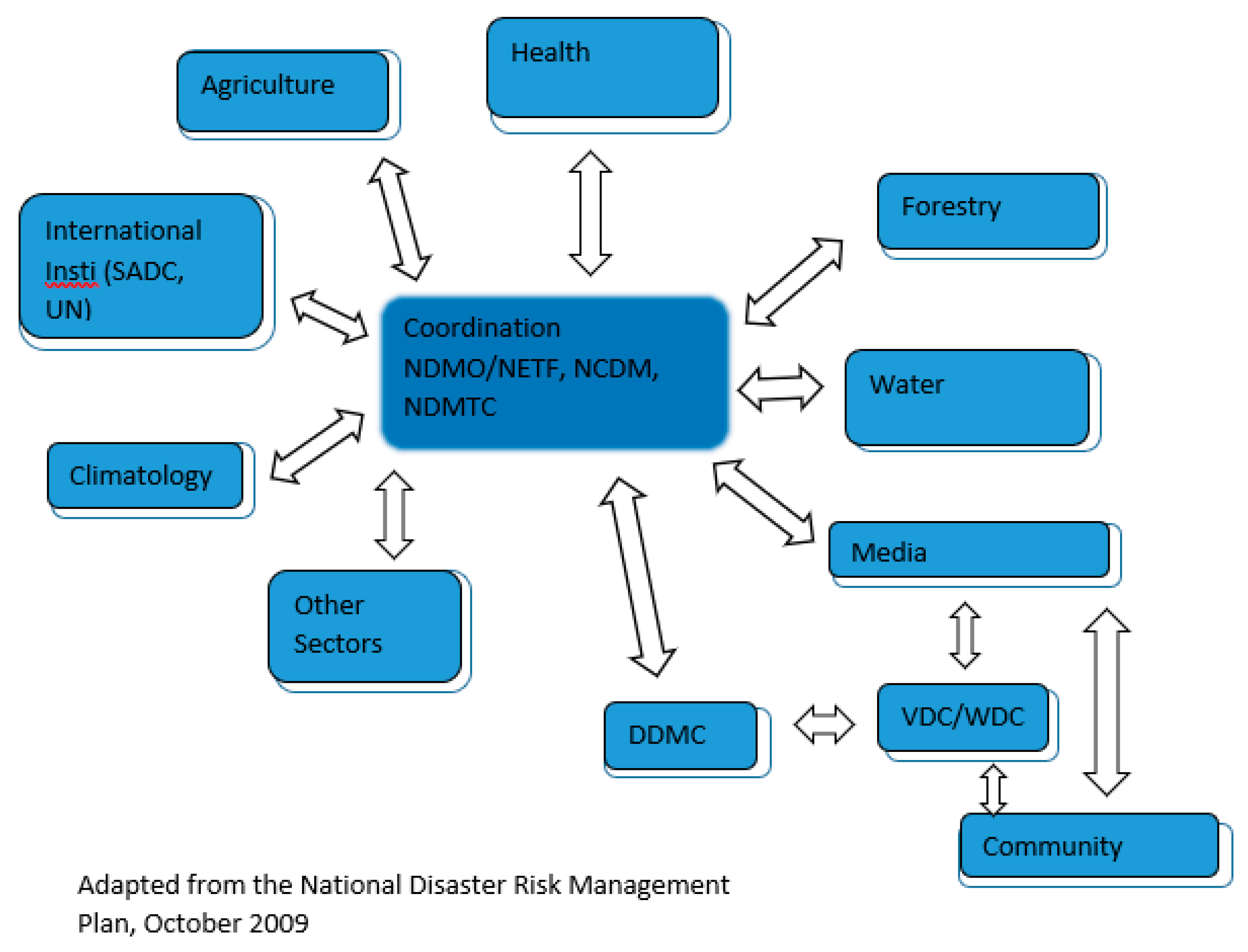

Community Based Flood Risk ReductionCommunity engagement in flood preparedness has proven effective in regions with high uncertainty in hydrological forecasting. Mercer et al. (2012) advocates for integrating local knowledge with scientific data for robust risk communication. In Botswana, Shinn (2018) and Takadzwa et al. (2017) emphasized the value of participatory methods for social-ecological adaptation, though the translation of forecasts into community-level action remains inexistent.Rahman et al. (2021) demonstrated in South Asia that community-based early warning systems (CBEWS) are only effective when communities understand, trust and respond to warnings. This reinforces Brown et al.’s (2019) observation in the Zambezi Basin that strong institutional frameworks are needed for early warning systems (EWS) to succeed in Africa.

- IV.

-

Flood Modeling and Inundation MappingGlobally, flood modeling has evolved in response to increasing flood frequency and severity. Models such as LISFLOOD-FP, HEC-RAS and SWAT have been widely applied to simulate flood inundation dynamics and support early warning systems. Earth observation (EO) data, particularly from MODIS, Sentinel-1 and Landsat satellites, has become central in these efforts, offering both cost effective and regularly updated data on flood extent, depth and duration (Schumann & Bates, 2018, Tarpanelli et al., 2017).However, in many low and middle-income regions, including sub Saharan Africa, flood models often suffer from coarse resolution, sparse ground calibration data, and weak institutional links with local disaster preparedness systems (Ward et al., 2015). This gap reveals the need for context-specific, smaller-scale modeling approaches that balance scientific accuracy with practical applicability for local stakeholders.In Botswana, the Okavango Delta more specifically, early work by Wolski et al. (2006,2007) laid the groundwork for flood modelling using a hybrid reservoir-GIS approach that considered river inflow, local rainfall, evapotranspiration and topography. These models were instrumental in demonstrating the non-linear hydrological behavior of the delta. More recently, Marthews et al. (2022) applied the global JULES-CaMa-Flood framework to simulate flooding across major tropical wetlands. Their findings revealed that while such models could represent broad seasonal trends, they struggled to reflect local-scale dynamics such as channel overflow and distribution shifting. The authors emphasized the need for locally calibrated models to improve flood predictability in Botswana’s wetland regions.While these developments in technology offer valuable insights into flood mapping and prediction, a persistent gap exists between EO-derived flood intelligence and the risk communication systems available to local communities. This study aims to address that gap by grounding flood analysis in both high-resolution EO data and local field-based knowledge, including community interviews and soil assessments. This integrated approach supports more accurate, equitable and usable flood forecasting in complex, data-scarce environments.

- V.

-

Soil Properties and Flood VulnerabilitySoil plays an important role in flood infiltration and runoff. Studies, such as Hillel (2004) and Wolski et al.’s (2006) work in modeling, point to the importance of analyzing physical soil parameters. While flood extent is often mapped using hydrological and remote sensing tools, the underlying soil physical properties play a foundational role in determining the flood vulnerability of an area, yet they remain under-represented in most models (Hess et al., 2022, Marthews et al., 2022). Parameters such as texture, soil structure, and moisture retention capacity among others, critically influence how water interacts with the land surface (Hillel, 2004, Brady & Weil, 2016).Soils in the Okavango delta range from sandy and well-drained dunes to clay-dominated and water-retaining soils in the low-lying alluvial plains (Murray-Hudson et al., 2016). These physical differences directly affect flood retention and runoff behavior. Clay soils, for instance, tend to impede infiltration and promote water pooling, increasing the risk of prolonged surface flooding (Rawls et al., 1993, Mikkelsen et al., 2013). Conversely, sandy soils allow rapid percolation but may worsen subsurface water loss, reducing the soil moisture available for vegetation and farming (Brady & Weil, 2016). Understanding soil data can help refine both flood risk assessments and adaptation strategies such as drainage interventions and placement of emergency infrastructure (Hillel, 2004, Mikkelsen et al., 2013).This study seeks to bridge the gap between hydrological modeling and the ground vulnerability assessment by combining soil sample analysis with flood maps generated from satellite imagery and remote sensing tools and community perspectives to assess flood vulnerability.

- VI.

-

Methodological Approaches in Similar StudiesNumerous studies have made important contributions to flood modeling, EO-based mapping and vulnerability assessments, however, only a few have effectively combined all three approaches. For instance, Wolski et al. (2017) integrated MODIS imagery with runoff simulations to estimate Okavango flood extent but did not engage the community. Meanwhile, Budhathoki et al. (2020) and Mufute et al. (2008) demonstrated the power of combining geospatial mapping with participatory risk communication. Masocha et al.’s (2021) is one of the very few studies that include soil physical characteristics to explain spatial variations in flood impacts.This study aims to bridge these gaps by combining EO-derived flood mapping, soil property field analysis and community-based interviews into a multi-scalar vulnerability framework for Ngamiland, Botswana.

2.3. Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Population

3.3. Sampling Frame

3.4. Sampling and Sampling Techniques

Spatial Data (Shape-files and Raster Files)

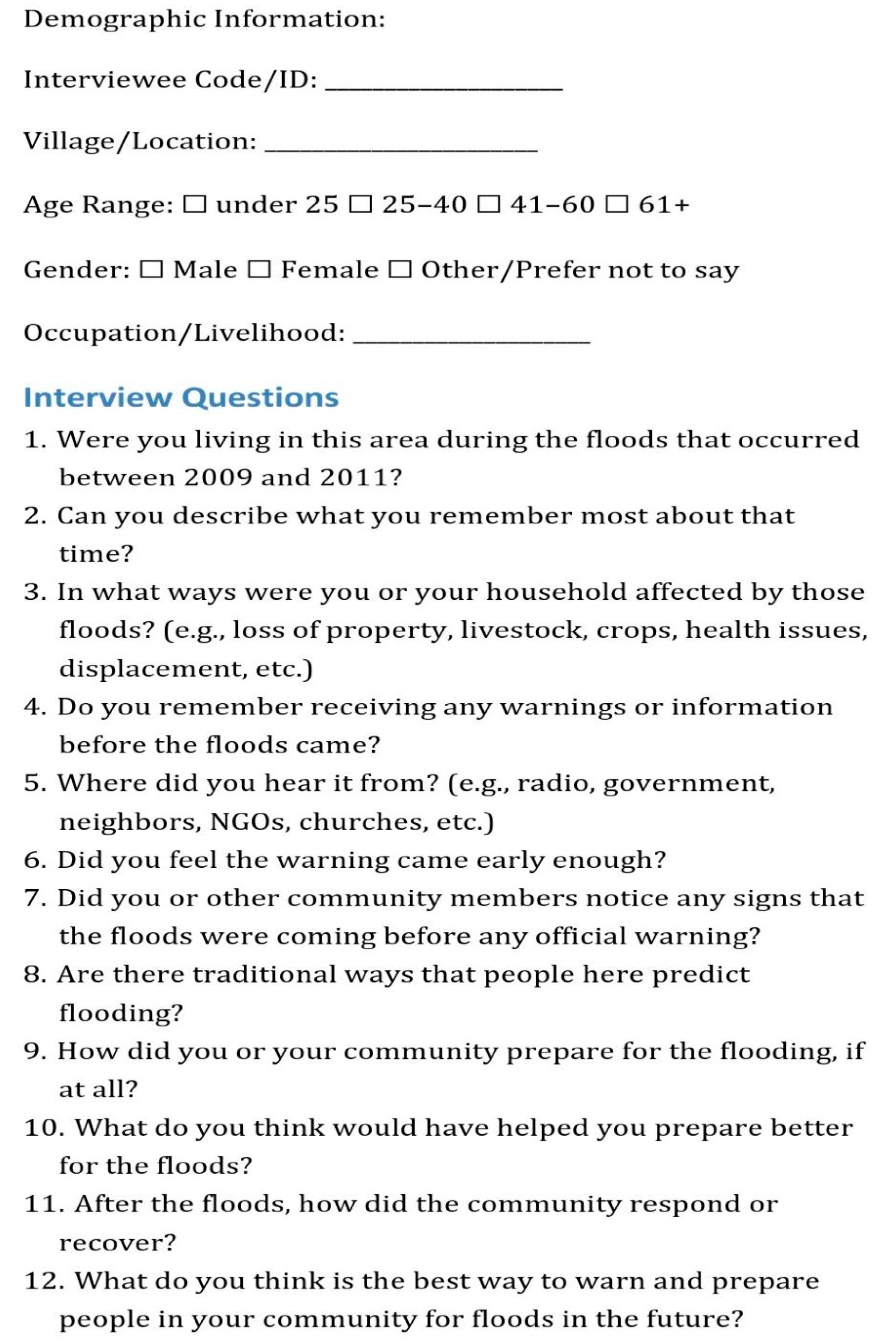

Interviews

Literature Review

3.5. Instrumentation

3.6. Data Collection Procedure

3.7. Data Processing and analysis

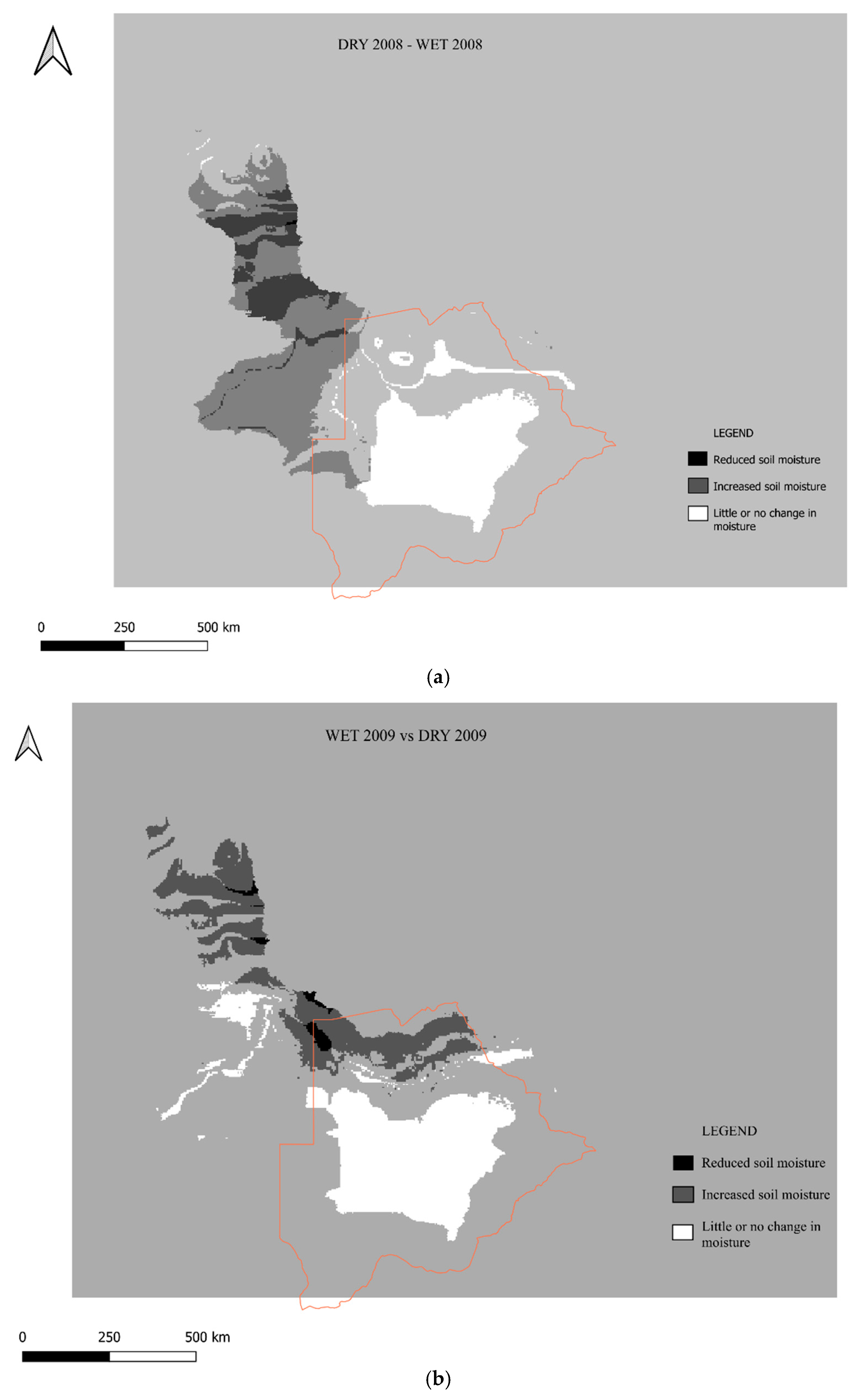

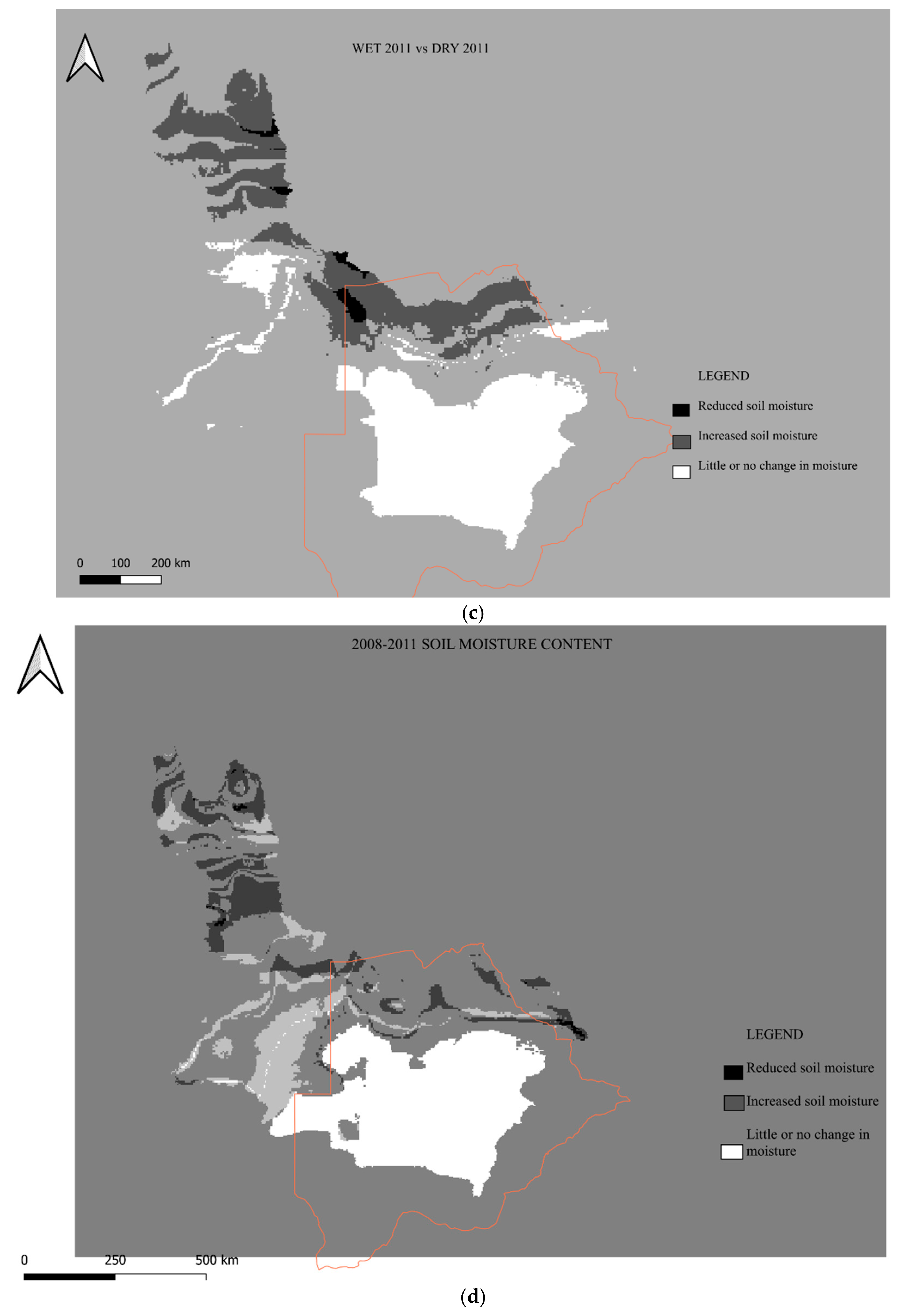

Remote Sensing data

Interviews

3.8. Ethical Considerations

- I.

- Informed Consent: all participants received a clear explanation of the study’s purpose, procedures and potential risks and benefits. Participation were completely voluntary and a written consent form, available in both Setswana and English languages, was signed by the participant before any interviews or soil sampling took place.

- II.

- Respect for Cultural Protocols: the study respected local hierarchies by seeking permission and entry through the Kgosi and Village Developments Committee (VDCs).

- III.

- Minimizing Harm and Discomfort: while the research does not deal with highly sensitive issues, participants recounting experiences of past flood events may be affected emotionally. To mitigate this, participants were allowed to skip questions or terminate interviews at any point. The researcher approached all interviews with empathy.

- IV.

- Institutional and National Ethics Approval: ethical clearance was sought from the University of Botswana Research Ethics Committee. This research was also aligned with the Botswana National Research Ethics Guidelines and any other protocols set by relevant institutions. A research permit was also acquired from the Ministry of Lands and Agriculture.

4. Results

Soil Properties Across Villages

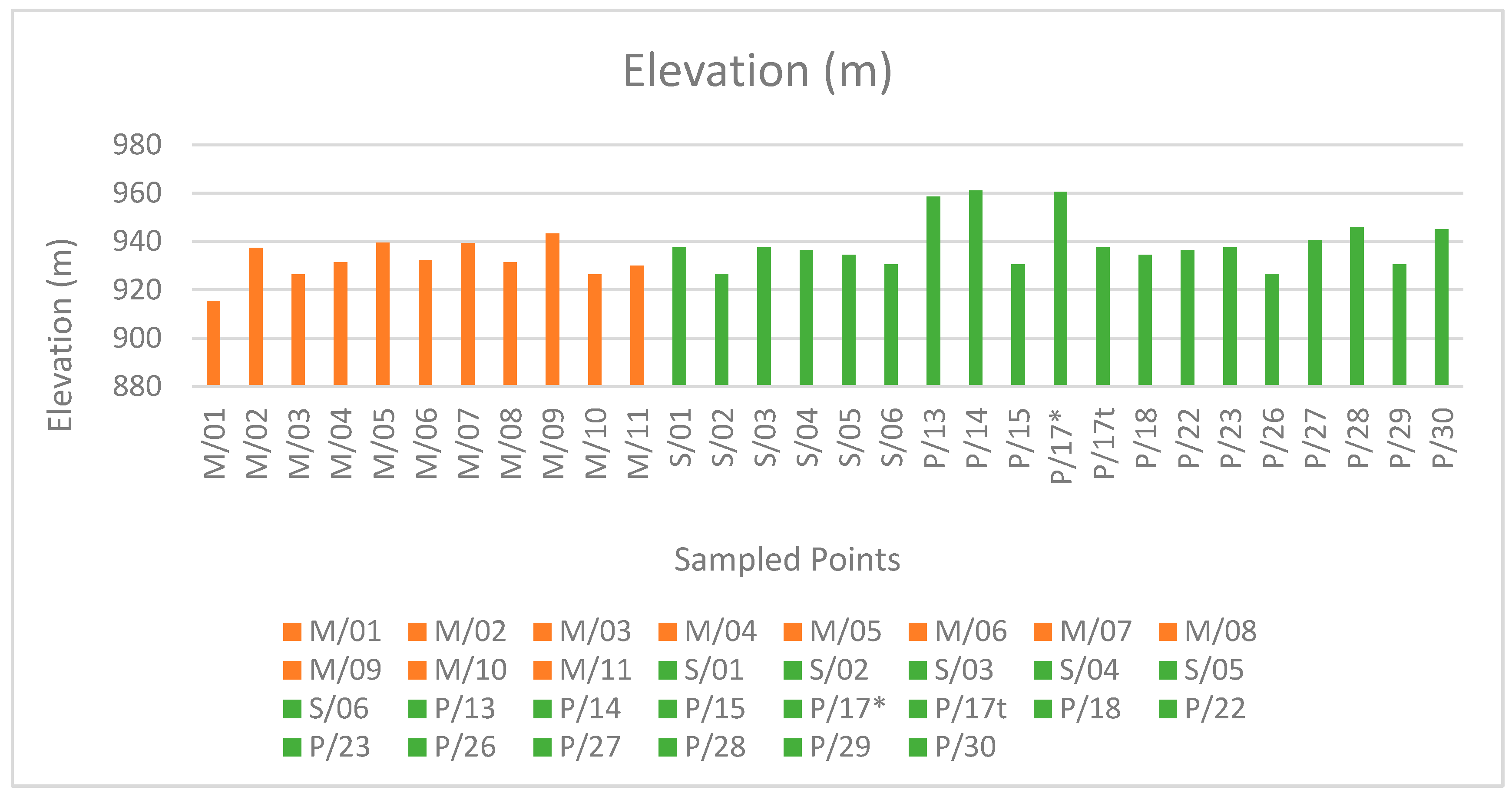

Elevation Data

SMI Data Analysis

Interview Responses

Community Awareness and Sources of Flood Information

Functionality of CBWES, Timing and Responsiveness

Risk Perception and Preparedness

Disconnect Between EO-Based Forecast and Community Action

Literature Review

Predictive Accuracy of Remote Sensing Approaches

Predictive Accuracy of Hydrological Models

5. Discussion

Physical and Chemical Soil Properties

- -

- Soil Texture and Flooding Implications

- -

- Gabamocha’s higher clay content in certain areas, (e.g., M/08) may enhance temporary water retention, making it more susceptible to waterlogging in low-lying areas. Shorobe soils, while sandier, had a sample (P/15) with 41% clay, suggesting isolated zones of potential high flood-water retention.

- -

- Organic Matter and Moisture Retention

- -

- Gabamocha had higher organic matter and moisture levels, especially in M/08 and M/03, pointing to possible organic matter accumulation due to prolonged flooding or vegetation decay. Lower bulk densities in these samples support the idea of looser, more porous soils that retain more water. Shorobe, on the other hand, displayed higher bulk density values and lower organic matter content overall, indicating more compacted soils that favor faster surface water runoff and less water storage during flooding.

- -

- Soil pH and Salinity Status

- -

- Both villages showed favorable pH conditions for plant growth (6.3-7.9), and EC values below 250µS/cm, indicating non-saline soils suitable for most crops and natural vegetation. No significant soil salinity concerns were identified in either site.

Elevation Data

Gabamocha (Flood-Prone)

Shorobe (Low Flood Risk)

EO Data

Interviews

Literature Review

6. Conclusions

7. Recommendations

- -

- Strengthen CBEWS Structures: reactivate and equip VDCs with basic training, materials, and decision-support tools to relay forecast information clearly and timely.

- -

- Promote participatory design of early warning messages by involving local leaders, elders and the youth to improve cultural and linguistic appropriateness, developing trust, comprehension and understanding.

- -

- Enhance Two-way Communication: structured channels such as mobile platforms, community radio sessions or disaster dialogues, where communities can not only receive but also respond to and critique forecast information, should be established.

- -

- Integrate soil properties into flood risk planning; identifying zones with high infiltration potential or those prone to waterlogging. Classifying areas which are more suitable for drainage infrastructure or erosion control interventions is also recommended.

- -

- Encourage collaboration between the National Disaster Management Office (NDMO), Department of Water Affairs, and agricultural extension services to ensure that flood forecasts and risk-management are coordinated and implemented at village level.

- -

- Incorporate high-resolution topography in hydrological models and flood forecasts to better represent risks at the village scale, as studies (e.g., Towey & Kemter, 2024; McClean et al., 2020) have shown the sensitivity of flood predictions to the accuracy of elevation inputs.

Appendix A

References

- Blackwell, C. , Mothorpe, C., & Wright, J. (2024). Flooding and Elevation: An Examination of Differential Price Responses to Flood Events. Journal of Sustainable Real Estate, 16(1). [CrossRef]

- Bhattamishra, R., & Barrett, C. B. (2010). Community-based risk management arrangements: A review. World Development, 38(7), 923–932. [CrossRef]

- Brown, C., Visser, H., & Mbungu, G. (2019). Strengthening Early Warning Systems in the Zambezi Basin. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 10(3), 317-330.

- Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED) & United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR), (2015). The human cost of natural disaster: A global perspective (No. ISBN 978-92-9139-204-6). United Nations.

- Garcia-Pintado, J., & Neal, J. C. (2023). Flood modeling and prediction using Earth observation data. Surveys in Geophysics, 44, 1553-1578. [CrossRef]

- Hillel, D. (2004). Introduction to Environmental Soil Physics. Academic Press.

- Inman, V. L., & Lyons, M. B. (2020). Automated Inundation Mapping Over Large Areas Using Landsat Data and Google Earth Engine. Remote Sensing, 12(8), 1348. [CrossRef]

- King, B. , Shinn, J. E., Crews, K. A., & Young, K. R. (2016). Fluid waters and rigid livelihoods in the Okavango Delta of Botswana. Land, 5(2), Article 16. [CrossRef]

- McClean, F., Dawson, R., & Kilsby, C. (2020). Implications of Using Global Digital Elevation Models for Flood Risk Analysis in Cities. Water Resources Research, 56(12), e2020WR028241. [CrossRef]

- Mercer, J., Kelman, I., Taranis, L., & Suchet-Pearson, S. (2012). Framework for integrating indigenous and scientific knowledge for disaster risk reduction. Disasters, 34(1), 214-239.

- Mfundisi, K. B. (2023). Multi-source Earth observation derived data for delineating the high flood waterline in the Okavango Delta (Unpublished master’s thesis or report). University of Twente. https://research.utwente.nl/en/publications/multi-source-earth-observation-derived-data-for-delineating-the-2.

- Mmopelwa, G., Kgathi, D. L., & Molefhe, L. (2011). Flooding in the Okavango Delta, Botswana: impacts on livelihoods and coping strategies. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C, 36(15-15), 984—991.

- Motsholapheko, M. R., Kgathi, D. L., & Vanderpost, C. (2013). An assessment of adaptation planning for flood variability in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Environmental Development, 5, 62-86.

- NASA Earth Observatory. (2008, January 4). Intense seasonal floods in Southern Africa. NASA. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/19495/intense-seasonal-floods-in-southern-africa.

- Paul, B. K. , Rashid, H., & Islam, M. S. (2018). Community-based early warning systems for disaster resilience: Lessons from cyclone-affected communities in coastal Bangladesh. Sustainable Development, 26. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M., Ahmed, S., & Haque, A. (2021). Community-based early warning systems in flood prone areas. Disasters, 45(2), 273-295.

- Tiwari, U. K. , Deo, R. C., & Adamowski, J. F. (2021). Short-term flood forecasting using artificial neural networks, extreme learning machines, and M5 model tree. In P. Sharma & D. Machiwal (Eds.), Advances in streamflow forecasting (pp. 263–279). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Seneviratne, S. I. , Corti, T., Davin, E. L., Hirschi, M., Jaeger, E. B., Lehner, I.,... & Teuling, A. J. (2010). Investigating soil moisture–climate interactions in a changing climate: A review. Earth-Science Reviews, 99. [CrossRef]

- Shinn, JE. Toward anticipatory adaptation: Transforming social-ecological vulnerabilities in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Geogr J. 2018; 184: 179–191. [CrossRef]

- Schumann, G. J. P., & Bates, P.D. (2018). The need for a high-accuracy, open-access global DEM. Frontiers in Earth Science, 6, 225.

- Tarpanelli, A., Brocca, L., Melone, F., et al. (2017). Toward operational satellite remote sensing of flood inundation. Remote sensing of flood inundation. Remote Sensing, 9(6), 560.

- Tevera, D. , Musasa, D., & Simelane, T. (2021). Assessment of Cyclone Idai floods on local flood systems and disaster management responses in Mozambique and Zimbabwe. Cyclones in Southern Africa (pp. 111-132).

- Thakadu, O. T. , Kolawole, O. D., & Sommer, C. (2017). Flood risk communication within flood-prone communities of the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Botswana Notes and Records, 49, Special Issue.

- Thito, K., Wolski, P., & Murray-Hudson, M. (2016). Mapping inundation extent, frequency and duration in the Okavango Delta from 2001 to 2012. African Journal of Aquatic Science, 41(3), 267–277. [CrossRef]

- Towey, K., & Kemter, M, (2024). Location, Location, Location: The Role of Elevation in Flood Models. MSCI. https://www.msci.com/research-and-insights/quick-take/location-location-location-the-role-of-elevation-in-flood-models.

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). 2017. The Sendai Framework Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction. “Early warning system”. Accessed 14 June 2025. https://www.undrr.org/terminology/early-warning-system.

- UNISDR. (2009). 2009 UNISDR Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction. United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction. https://www.unisdr.org.

- Ward, P. J., Jongman B., Salamon, P., et al. (2015). Usefulness and limitations of global flood risk models. Nature Climate Change, 5(8), 712-715.

- Wisner, B., Blaikie, P., Cannon, T., & Davis, I. (2004). At Risk: Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability and Disasters. Routledge.

- Wolski, P., Savenije, H. H. G., Murray-Hudson, M., & Gumbricht, T. (2006). Modelling of the flooding in the Okavango Delta, Botswana, using a hybrid reservoir-GIS model. Journal of Hydrology, 331(1–2), 58–72. [CrossRef]

- Wolski, P., Murray-Hudson, M. & Todd, M. (2017). Modelling floods in the Okavango Delta. Journal of Hydrology, 549, 788-800.

- World Meteorological Organization. (2011). Manual on flood forecasting and warning (WMO-No. 1072). World Meteorological Organization. https://www.pseau.org/outils/ouvrages/omm_manual_on_flood_forecasting_and_warning_2011.pdf.

| Point ID | Latitude | Longitude |

| M/01 | -19.762898 | 23.612183 |

| M/02 | -19.76288 | 23.610231 |

| M/03 | -19.762828 | 2.609059 |

| M/04 | -19.762879 | 23.607991 |

| M/05 | -19.784474 | 23.646196 |

| M/06 | -19.761711 | 23.605911 |

| M/07 | -19.759971 | 23.589081 |

| M/08 | -19.760359 | 23.589116 |

| M/09 | -19.759706 | 23.589 |

| M/10 | -19.759562 | 23.588717 |

| M/11 | -19.758563 | 23.586337 |

| S/01 | -19.763571 | 23.671286 |

| S/02 | -19.76204 | 23.669155 |

| S/03 | -19762277 | 23.667103 |

| S/04 | -19.761481 | 23.666396 |

| S/05 | -19.761381 | 23.674333 |

| S/06 | -19.761261 | 23.674839 |

| P/13 | -19.778946 | 23.663702 |

| P/14 | -19.770677 | 23.668104 |

| P/15 | -19.771028 | 23.672285 |

| P/17* | -19.761192 | 23.677708 |

| P/17t | -19.761243 | 23.679253 |

| P/18 | -19.757296 | 23.682271 |

| P/22 | -19.768464 | 23.679633 |

| P/23 | -19.764147 | 23.682874 |

| P/26 | -19.779198 | 23.679412 |

| P/27 | -19.775864 | 23.678411 |

| P/28 | -19.770731 | 23.682409 |

| P/29 | -19.766557 | 23.686373 |

| P/30 | -19.763207 | 23.688853 |

| SAMPLE ID | MOISTURE CONTENT (%) | TOTAL ORGANIC CONTENT(%) | pH | ELECTRIC CONDUCTIVITY (μs/cm) | BULK DENSITY (g/ml) |

| *M/01 | 82.67 | 12.034 | 6.81 | 69.3 | 1.2535 |

| *M/02 | 154.18 | 15.52 | 6.639 | 221 | 1.0423 |

| *M/03 | 759.95 | 9.1 | 7.017 | 54 | 1.4077 |

| *M/04 | 39.91 | 5.38 | 7.975 | 54.4 | 1.2669 |

| *M/05 | 33.66 | 5.45 | 7.499 | 33.2 | 1.2808 |

| *M/06 | 234.3 | 12.05 | 7.017 | 60 | 1.0461 |

| *M/07 | 78.24 | 9.84 | 6.883 | 43.4 | 1.2309 |

| *M/08 | 432.58 | 2312.13 | 6.86 | 63.4 | 0.9380 |

| *M/09 | 112.59 | 12.24 | 6.685 | 38.1 | 1.1531 |

| *M/10 | 75.68 | 9.53 | 6.601 | 39.9 | 1.2482 |

| *M/11 | 52.33 | 6.99 | 6.489 | 48.3 | 1.1289 |

| ^S/01 | 71.54 | 4.64 | 7.405 | 76.6 | 1.2863 |

| ^S/02 | 22.26 | 1.16 | 7.305 | 16.2 | 1.5519 |

| ^S/03 | 97.79 | 4.56 | 6.57 | 53.8 | 1.0030 |

| ^S/04 | 30.56 | 1.89 | 6.635 | 15.6 | 1.1760 |

| ^S/05 | 27.02 | 4.32 | 6.538 | 53 | 1.4573 |

| ^S/06 | 17.13 | 2.35 | 6.319 | 26.6 | 1.4204 |

| ^P/13 | 64.47 | 17.71 | 7.816 | 112.6 | 1.2655 |

| ^P/14 | 45.98 | 424.77 | 7.46 | 31.8 | 1.3140 |

| ^P/15 | 75.32 | 47.39 | 6.841 | 28.5 | 1.2377 |

| ^P/17 | 21.08 | 41.7 | 6.89 | 57.9 | 1.2759 |

| ^P/17t | 23.79 | 96.33 | 6.757 | 17.9 | 1.4138 |

| ^P/18 | 44.86 | 5.4 | 6.65 | 18.9 | 1.2498 |

| ^P/22 | 59.78 | 4.4 | 6.475 | 27.9 | 1.3472 |

| ^P/23 | 57.63 | 5.54 | 6.532 | 32.8 | 1.3859 |

| ^P/26 | 23.88 | 3.64 | 6.312 | 16.5 | 1.4417 |

| ^P/27 | 31.06 | 5.45 | 6.591 | 25.4 | 1.3512 |

| ^P/28 | 42.88 | 5.85 | 6.25 | 18.5 | 1.2686 |

| ^P/29 | 46.24 | 5.44 | 6.289 | 17.6 | 1.4041 |

| ^P/30 | 57 | 7.24 | 6.373 | 15.3 | 1.4694 |

| SAMPLE ID | % Sand | % Silt | % Clay | Texture Class |

| *M/02 | 52.2 | 31.1 | 16.7 | Sandy clay loam |

| *M/04 | 57.3 | 30.4 | 12.3 | Sandy loam |

| *M/05 | 74 | 19 | 7 | Loamy sand |

| *M/08 | 53.4 | 19.4 | 27.2 | Sandy loam |

| *M/11 | 70.2 | 29.4 | 0.4 | Loamy sand |

| ^P/14 | 66.2 | 21.4 | 12.4 | Sandy loam |

| ^P/15 | 53 | 6 | 41 | Sandy clay loam |

| ^P/29 | 53.6 | 24.8 | 21.6 | Sandy loam |

| ^S/02 | 75 | 5.4 | 19.6 | Loamy sand |

| ^S/05 | 77.6 | 16 | 6.4 | Loamy sand |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).