Submitted:

03 February 2025

Posted:

04 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

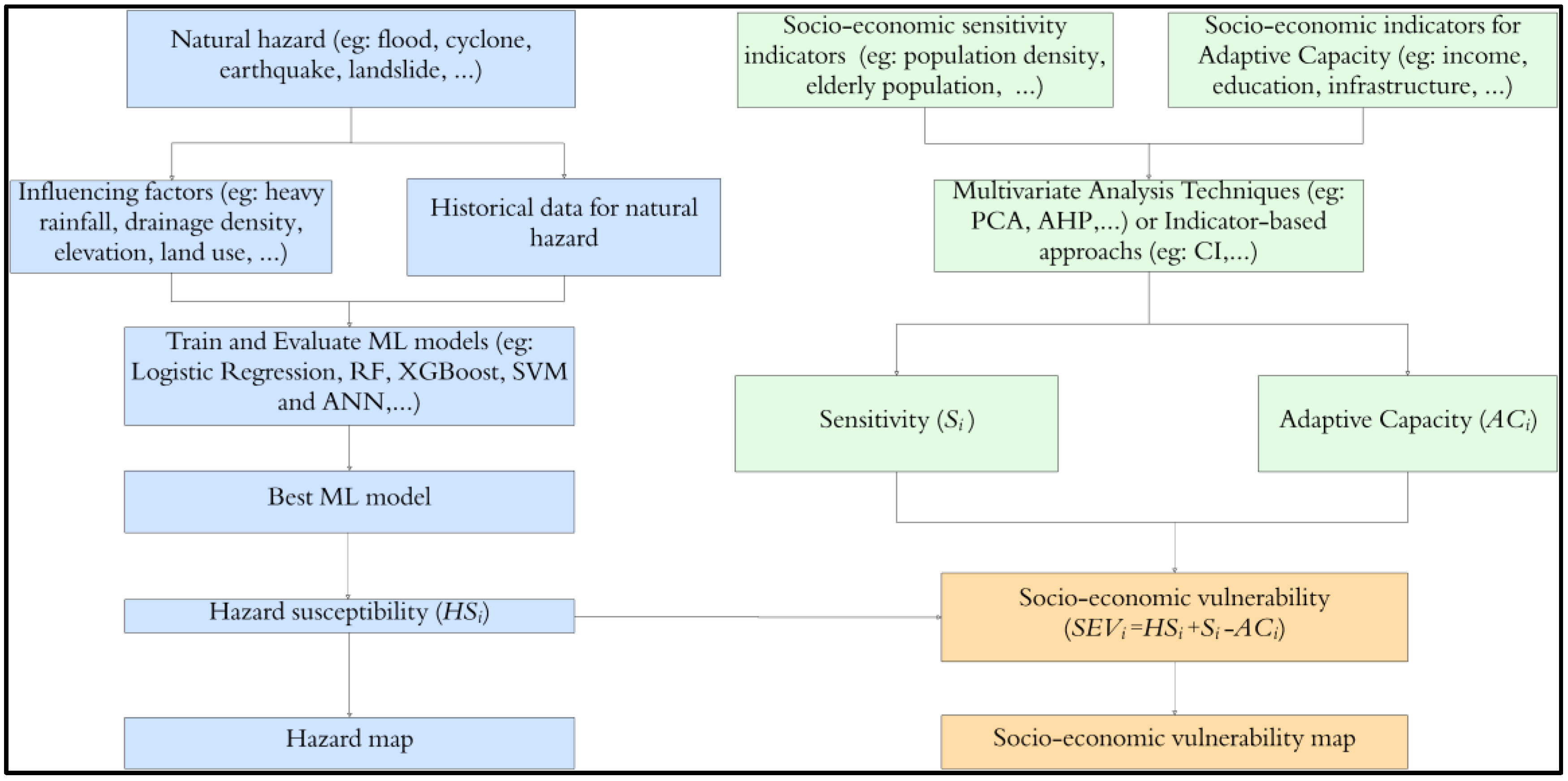

2.1. Description of the Proposed Framework

2.2. Application of the Proposed Framework to Mapping Socio-Economic Vulnerability to Flooding in the City of Kigali

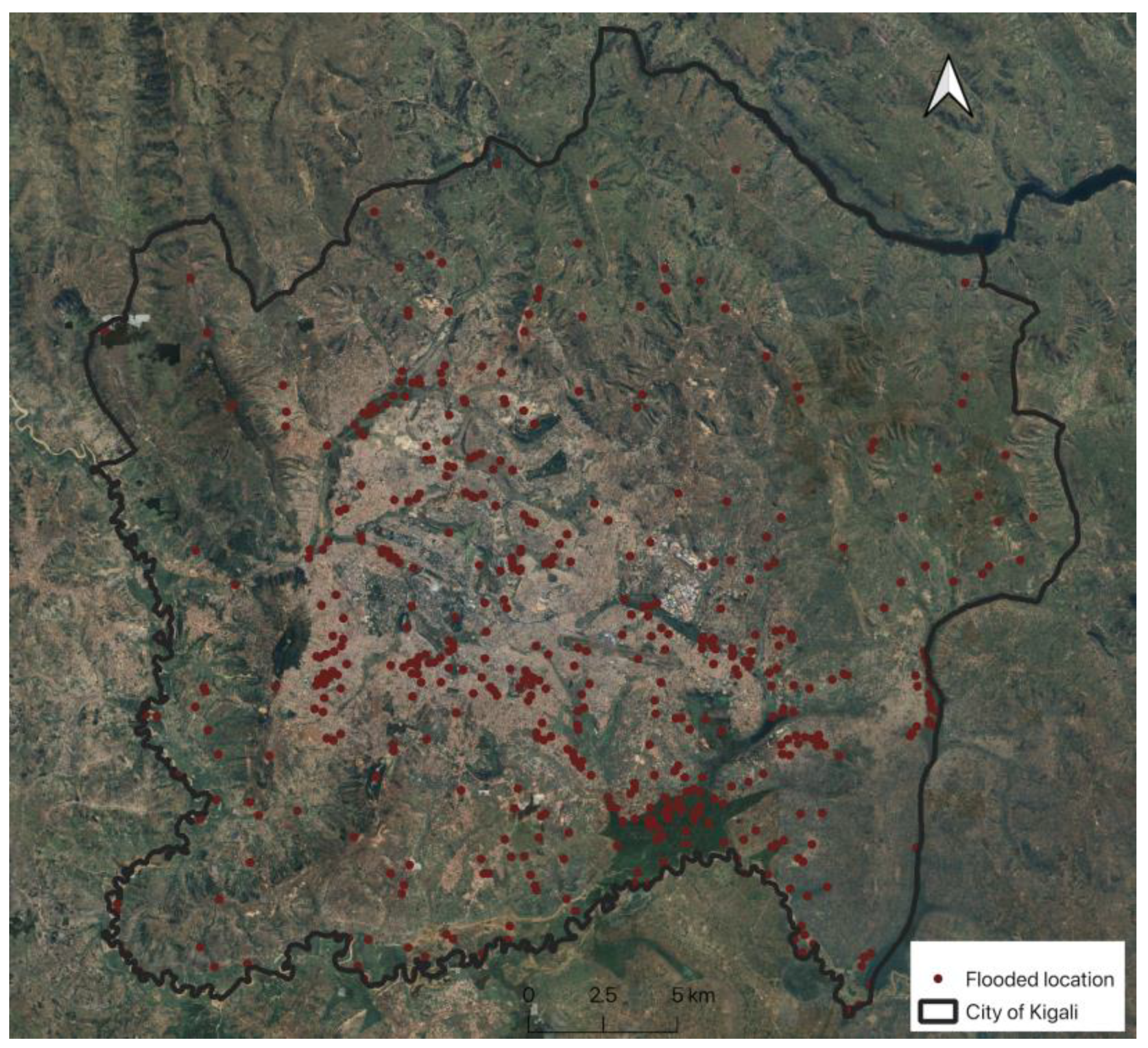

2.2.1. Description of City of Kigali

2.2.2. Overview of Data

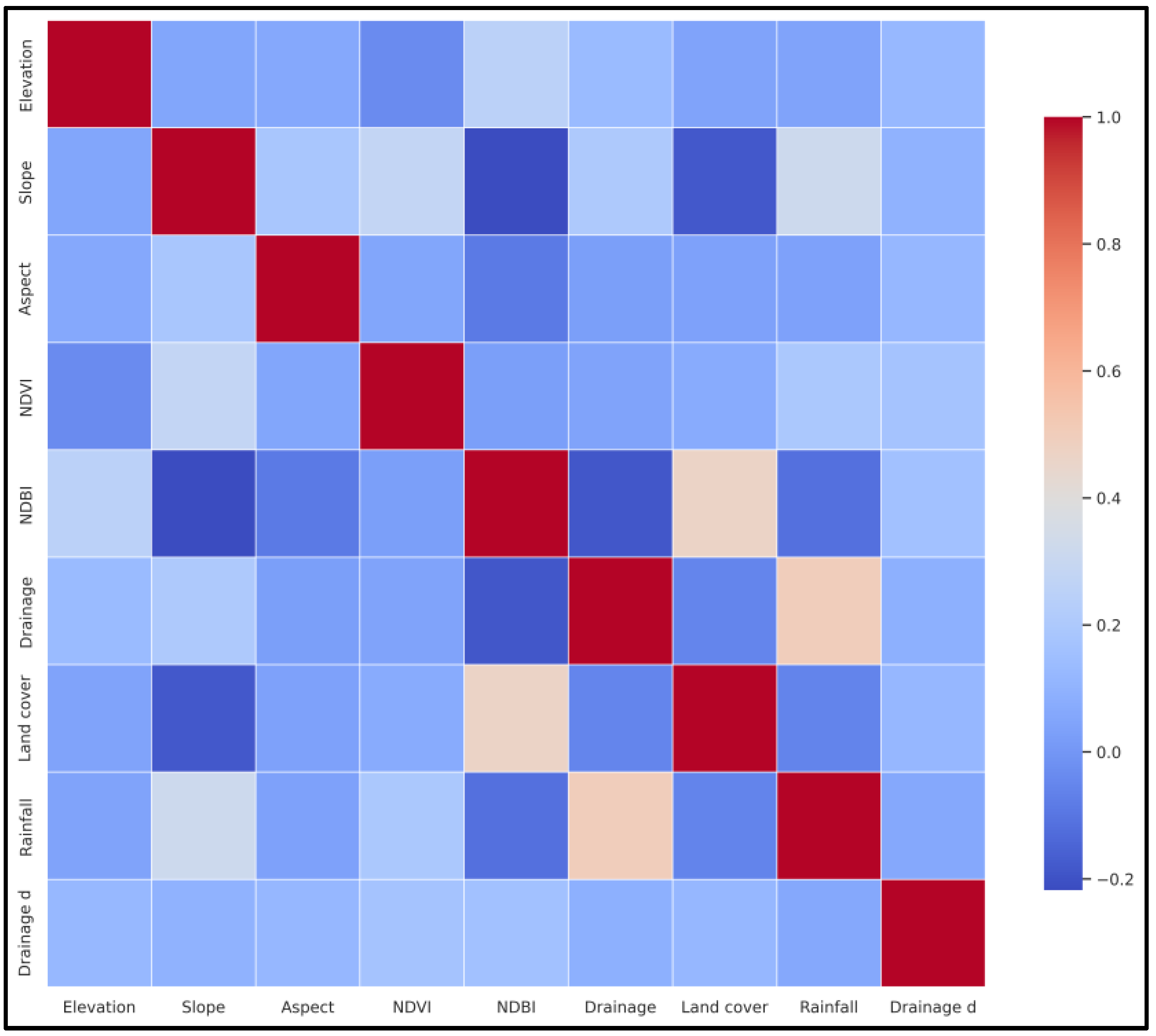

2.2.3. Flood Susceptibility Estimation with Machine Learning Models

2.2.4. Mapping Socio-Economic Vulnerability to Flood

2.2.5. Validation of Flood Susceptibility and Socio-Economic Vulnerability Maps

2.3. Scalability and Transferability of the Framework

4. Results and Discussion

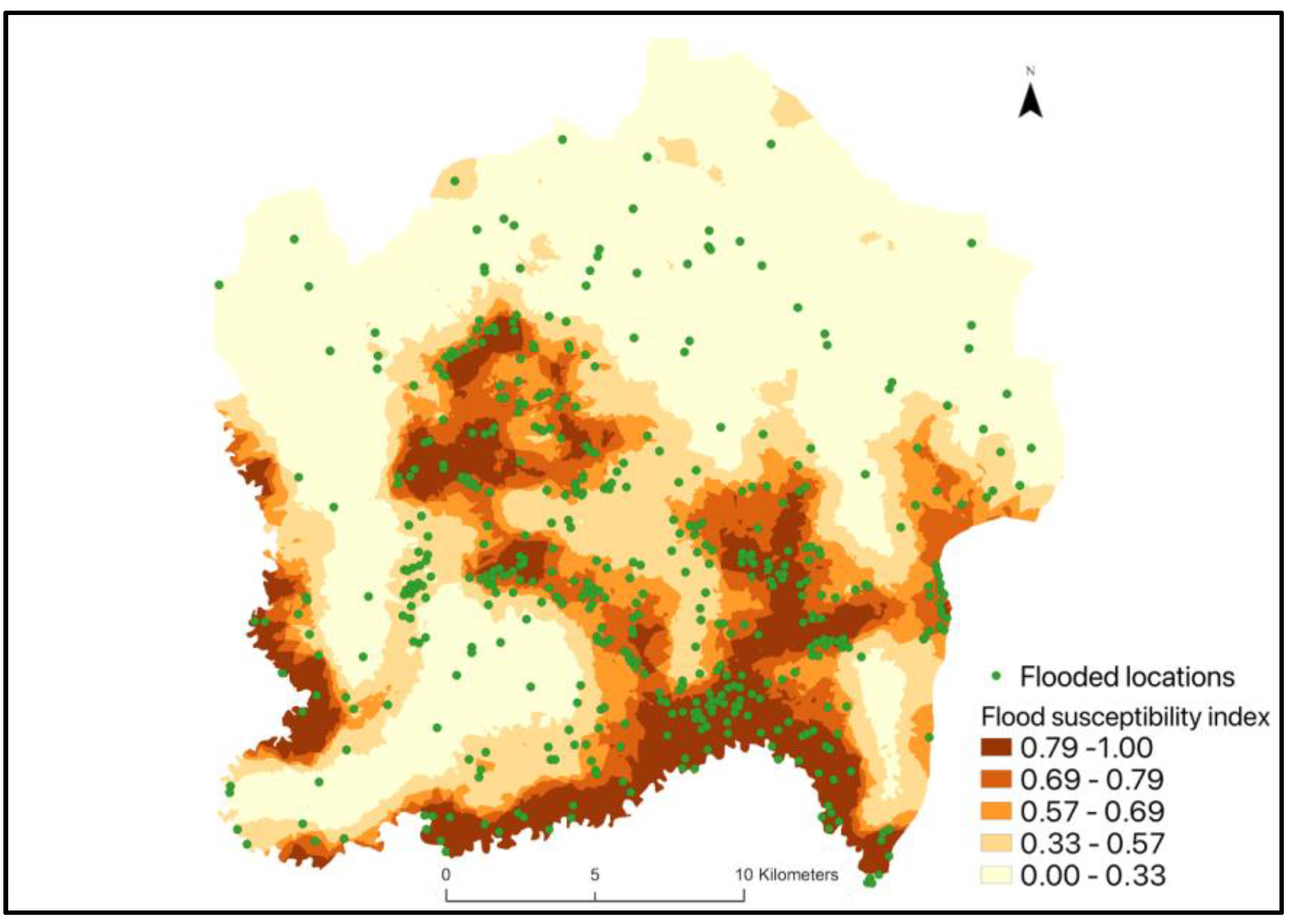

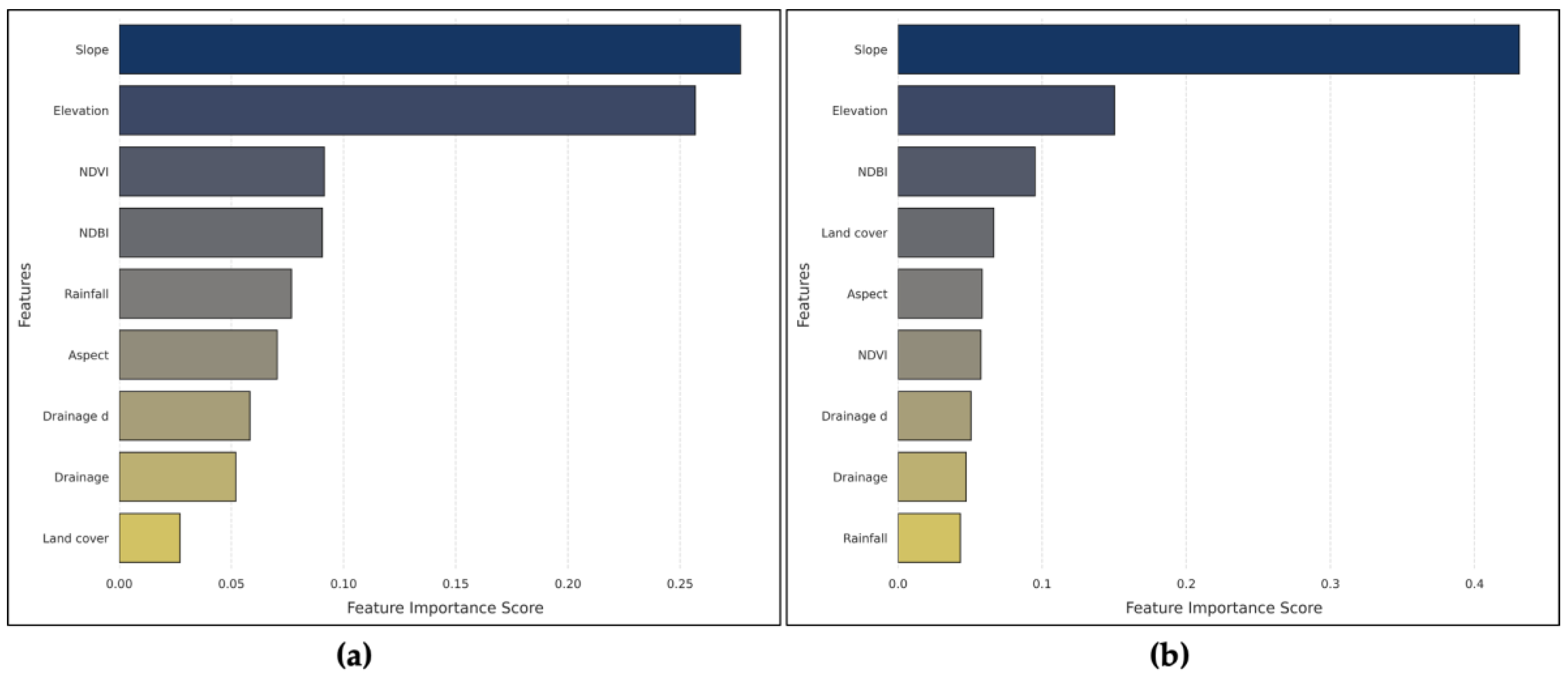

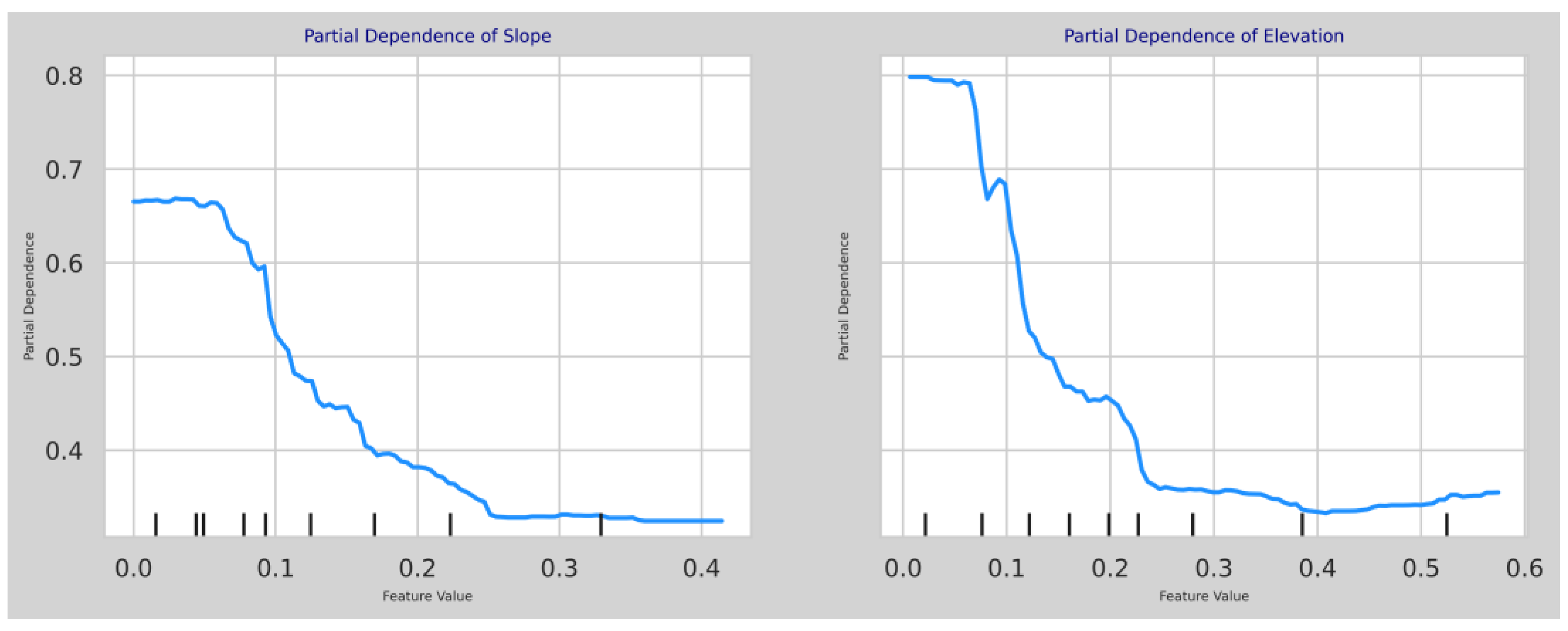

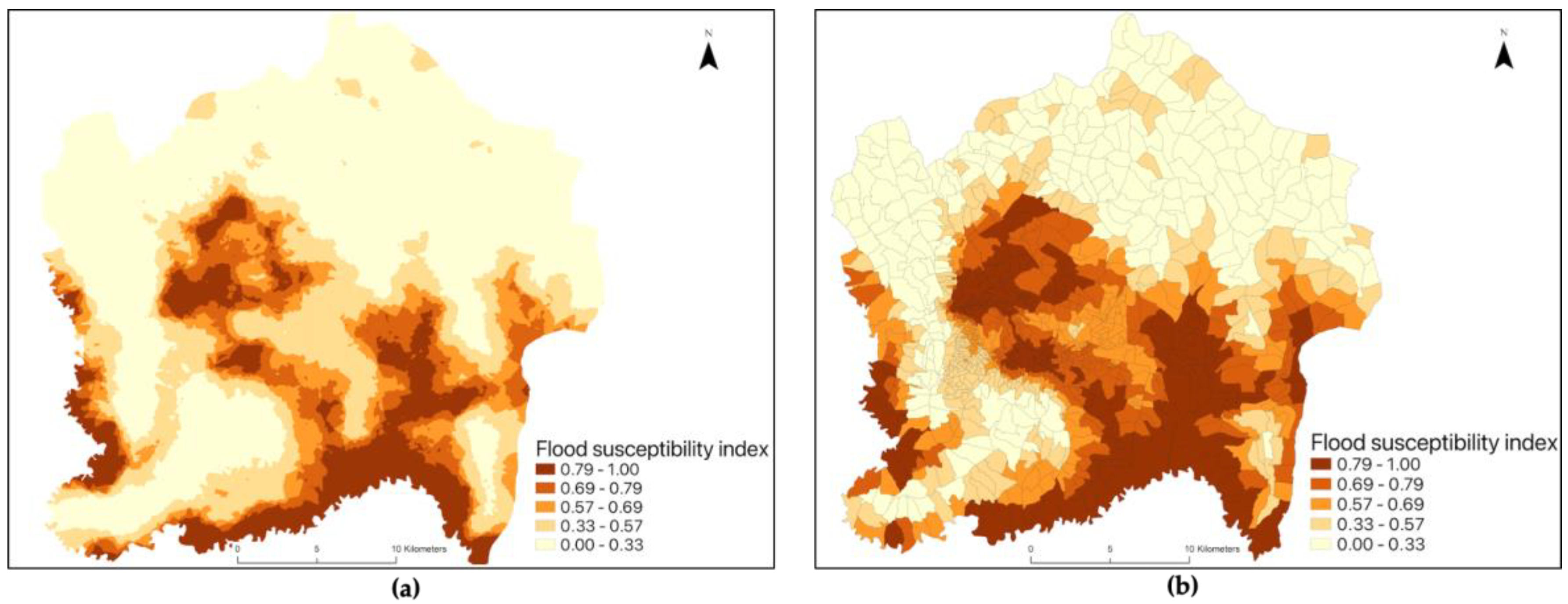

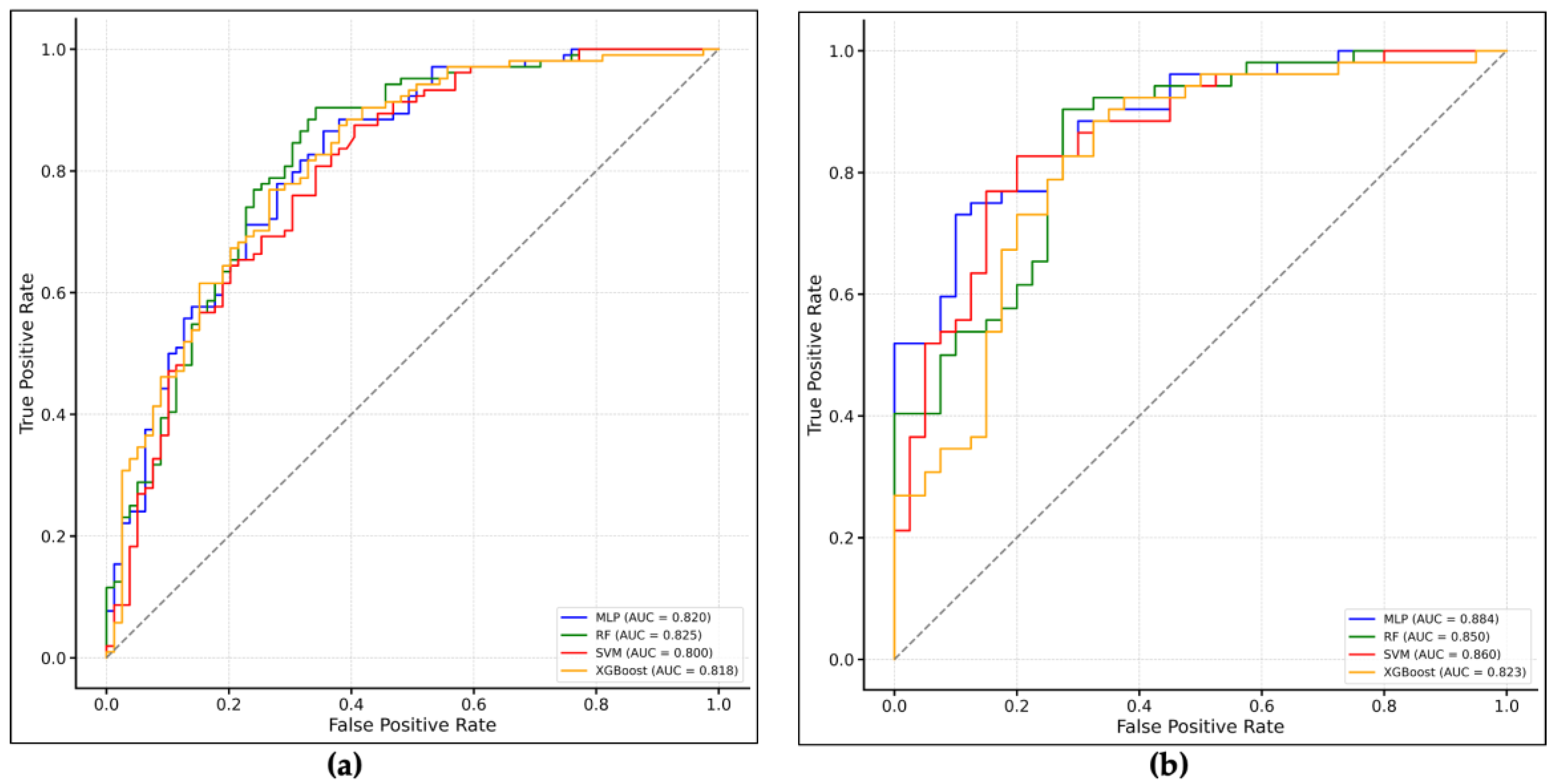

4.1. Flood Susceptibility Map

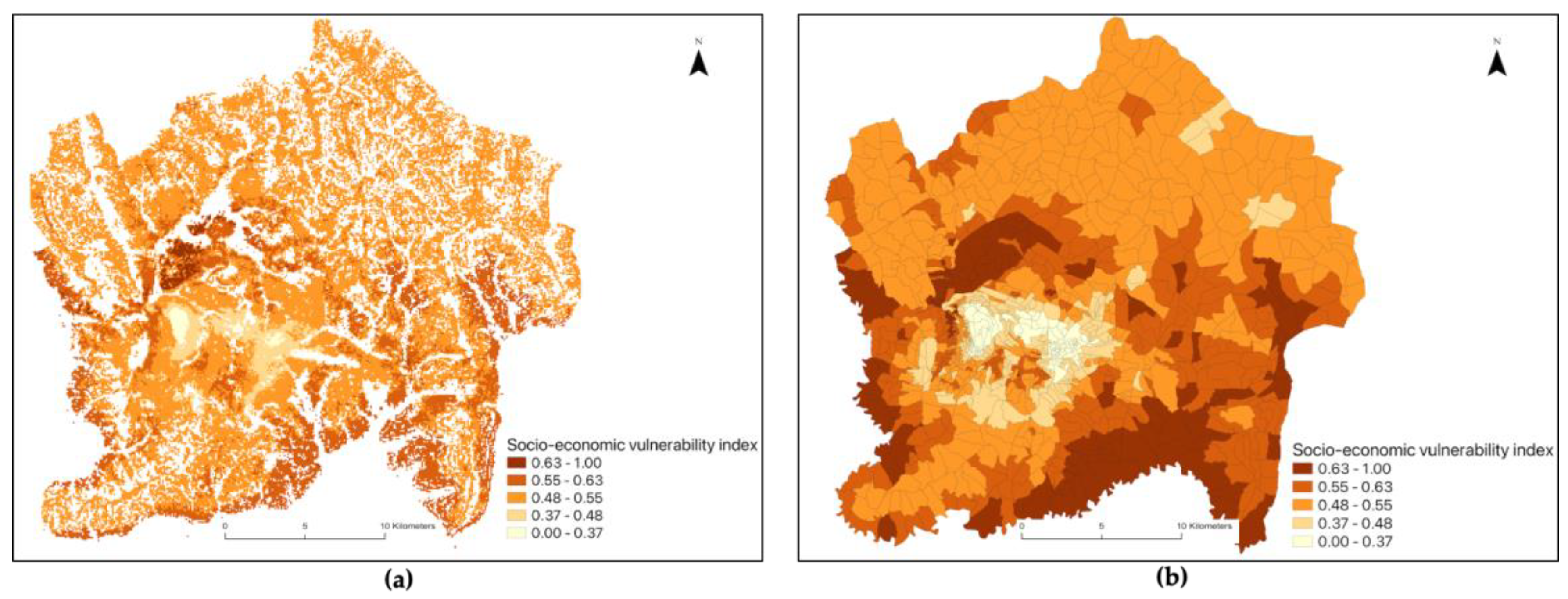

4.2. Socio-Economic Vulnerability Map

4.3. Scalability and Transferability

4.4. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

References

- United Nations, World Social Report 2020: Inequality in a Rapidly Changing World. 2020. Available online: http://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2020/02/World-Social-Report2020-FullReport.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- UN-Habitat, Urbanization and Development: Emerging Futures. Nairobi, 2016. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/ files/download-manager-files/WCR-2016-WEB.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2020).

- R. Mahabir, A. R. Mahabir, A. Crooks, A. Croitoru, and P. Agouris, “The study of slums as social and physical constructs: challenges and emerging research opportunities,” Reg Stud Reg Sci, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 399–419, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- B. Alves, D. B. B. Alves, D. B. Angnuureng, P. Morand, and R. Almar, “A review on coastal erosion and flooding risks and best management practices in West Africa: what has been done and should be done,” J Coast Conserv, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 1–22, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Climate Change 2022 – Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Cambridge University Press, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Galderisi and, G. Limongi, “A Comprehensive Assessment of Exposure and Vulnerabilities in Multi-Hazard Urban Environments: A Key Tool for Risk-Informed Planning Strategies,” Sustainability 2021, Vol. 13, Page 9055, vol. 13, no. 16, p. 9055, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Deroliya, M. P. Deroliya, M. Ghosh, M. P. Mohanty, S. Ghosh, K. H. V. D. Rao, and S. Karmakar, “A novel flood risk mapping approach with machine learning considering geomorphic and socio-economic vulnerability dimensions,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 851, p. 158002, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- IPCC, “Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability,” in Climate Change 2022 – Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M.K. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, and B. Rama, Eds., Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Peter Terna, “Vulnerability: Types, Causes, and Coping Mechanisms,” International Journal of Science and Management Studies (IJSMS), pp. 187–194, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Aroca-Jiménez, J. M. E. Aroca-Jiménez, J. M. Bodoque, and J. A. García, “How to construct and validate an Integrated Socio-Economic Vulnerability Index: Implementation at regional scale in urban areas prone to flash flooding,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 746, p. 140905, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. B. Julià and T. M. Ferreira, “From single- to multi-hazard vulnerability and risk in Historic Urban Areas: a literature review,” Natural Hazards, vol. 108, no. 1, pp. 93–128, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Sun, Y. Y. Sun, Y. Li, R. Ma, C. Gao, and Y. Wu, “Mapping urban socio-economic vulnerability related to heat risk: A grid-based assessment framework by combing the geospatial big data,” Urban Clim, vol. 43, p. 101169. May 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ajtai, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “Mapping social vulnerability to floods. A comprehensive framework using a vulnerability index approach and PCA analysis,” Ecol Indic, vol. 154, p. 110838, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. L. Paterson, H. D. L. Paterson, H. Wright, and P. N. A. Harris, “Health Risks of Flood Disasters,” Clinical Infectious Diseases, vol. 67, no. 9, pp. 1450–1454, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Nagendra, X. H. Nagendra, X. Bai, E. S. Brondizio, and S. Lwasa, “The urban south and the predicament of global sustainability,” Nat Sustain, vol. 1, no. 7, pp. 341–349, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Hagenlocher et al., “Climate Risk Assessment for Ecosystem-based Adaptation A guidebook for planners and practitioners,” 2018. Available online: https://www.adaptationcommunity.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/giz-eurac-unu-2018-en-guidebook-climate-risk-asessment-eba.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2024)).

- United Nations, Revision of World Urbanization Prospects. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2018. Available online: https://population.un.org/wup/Publications/Files/WUP2018-Highlights.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2023).

- S. Biswas and S. Nautiyal, “A review of socio-economic vulnerability: The emergence of its theoretical concepts, models and methodologies,” Natural Hazards Research, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 563–571, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- McCallum, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “Estimating global economic well-being with unlit settlements,” Nature Communications 2022 13:1, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 1–8, 22. May 2022. [CrossRef]

- Yeh, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “Using publicly available satellite imagery and deep learning to understand economic well-being in Africa,” Nat Commun, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 2583, 20. May 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Kuffer et al., “The role of earth observation in an integrated deprived area mapping ‘system’ for low-to-middle income countries,” Remote Sens (Basel), vol. 12, no. 6, p. 982, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Skinner, “Issues and Challenges in Census Taking,” Annu Rev Stat Appl, vol. 5, pp. 49–63, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Kazemi, F. M. Kazemi, F. Mohammadi, M. H. Nafooti, K. Behvar, and N. Kariminejad, “Flood susceptibility mapping using machine learning and remote sensing data in the Southern Karun Basin, Iran,” Applied Geomatics, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 731–750, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Seleem, G. Ayzel, A. C. T. de Souza, A. Bronstert, and M. Heistermann, “Towards urban flood susceptibility mapping using data-driven models in Berlin, Germany,” Geomatics, Natural Hazards and Risk, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 1640–1662, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Javidan, A. N. Javidan, A. Kavian, H. R. Pourghasemi, C. Conoscenti, Z. Jafarian, and J. Rodrigo-Comino, “Evaluation of multi-hazard map produced using MaxEnt machine learning technique,” Sci Rep, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 6496, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. R. Pourghasemi et al., “Assessing and mapping multi-hazard risk susceptibility using a machine learning technique,” Sci Rep, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 3203, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. Sakti et al., “Machine learning based urban sprawl assessment using integrated multi-hazard and environmental-economic impact,” Sci Rep, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 13385, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Yousefi, H. R. S. Yousefi, H. R. Pourghasemi, S. N. Emami, S. Pouyan, S. Eskandari, and J. P. Tiefenbacher, “A machine learning framework for multi-hazards modeling and mapping in a mountainous area,” Sci Rep, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 12144, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Alabbad and, I. Demir, “Comprehensive flood vulnerability analysis in urban communities: Iowa case study,” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, vol. 74, 22. May 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Zhang, D. T. Zhang, D. Wang, and Y. Lu, “Machine learning-enabled regional multi-hazards risk assessment considering social vulnerability,” Sci Rep, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 13405, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Brower et al., “Augmenting the Social Vulnerability Index using an agent-based simulation of Hurricane Harvey,” Comput Environ Urban Syst, vol. 105, p. 102020, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Davino, M. Gherghi, S. Sorana, and D. Vistocco, “Measuring Social Vulnerability in an Urban Space Through Multivariate Methods and Models,” Soc Indic Res, vol. 157, no. 3, pp. 1179–1201, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. Hadipour, F. V. Hadipour, F. Vafaie, and N. Kerle, “An indicator-based approach to assess social vulnerability of coastal areas to sea-level rise and flooding: A case study of Bandar Abbas city, Iran,” Ocean Coast Manag, vol. 188, p. 105077, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- V. Streifeneder, S. V. Streifeneder, S. Kienberger, S. Reichel, and D. Hölbling, “Socio-Economic Vulnerability Assessment for Supporting a Sustainable Pandemic Management in Austria,” sustainability, vol. 16, no. 1, p. 78, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Zhu, Z. K. Zhu, Z. Wang, C. Lai, S. Li, Z. Zeng, and X. Chen, “Evaluating Factors Affecting Flood Susceptibility in the Yangtze River Delta Using Machine Learning Methods,” International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. M. Al-Kindi and Z. Alabri, “Investigating the Role of the Key Conditioning Factors in Flood Susceptibility Mapping Through Machine Learning Approaches,” Earth Systems and Environment, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Khosravi et al., “A comparative assessment of decision trees algorithms for flash flood susceptibility modeling at Haraz watershed, northern Iran,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 627, pp. 744–755, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. Zhu, Z. K. Zhu, Z. Wang, C. Lai, S. Li, Z. Zeng, and X. Chen, “Evaluating Factors Affecting Flood Susceptibility in the Yangtze River Delta Using Machine Learning Methods,” International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Sun, Y. Y. Sun, Y. Li, R. Ma, C. Gao, and Y. Wu, “Mapping urban socio-economic vulnerability related to heat risk: A grid-based assessment framework by combing the geospatial big data,” Urban Clim, vol. 43, p. 101169, 22. May 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Chakraborty, H. L. Chakraborty, H. Rus, D. Henstra, J. Thistlethwaite, and D. Scott, “A place-based socioeconomic status index: Measuring social vulnerability to flood hazards in the context of environmental justice,” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, vol. 43, p. 101394, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda, “Fifth Rwanda Population and Housing Census, 2022” 2022. Available online: https://statistics.gov.rw/file/13787/download?token=gjjLyRXT.

- City of Kigali, “Zoning regulations: Kigali Master Plan 2050” 2019. Available online: https://masterplan2020.kigalicity.gov.rw/portal/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=218a2e3088064fc6b13198b4304f3d35/#:~:text=be%20found%20here%3A-,Zoning%20Regulations,-Transport%20Plan (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- G. Baffoe, J. G. Baffoe, J. Malonza, V. Manirakiza, and L. Mugabe, “Understanding the concept of neighbourhood in Kigali City, Rwanda,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 1–22, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Hafner, S. S. Hafner, S. Georganos, T. Mugiraneza, and Y. Ban, “Mapping Urban Population Growth from Sentinel-2 MSI and Census Data Using Deep Learning: A Case Study in Kigali, Rwanda” 2023, In 2023 Joint Urban Remote Sensing Event (JURSE) (pp. 1-4). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Nikuze, R. Sliuzas, and J. Flacke, “Towards Equitable Urban Residential Resettlement in Kigali, Rwanda,” in GIS in Sustainable Urban Planning and Management, CRC Press, 2018, pp. 325–344. [CrossRef]

- Uwizeye, A. Irambeshya, S. Wiehler, and F. Niragire, “Poverty profile and efforts to access basic household needs in an emerging city: a mixed-method study in Kigali’s informal urban settlements, Rwanda,” Cities Health, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 98–112, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Dufitimana, P. Gahungu, E. Uwayezu, E. Mugisha, A. Poorthuis, and J. P. Bizimana, “Measuring urban socio-economic disparities in the global south from space using convolutional neural network: the case of the City of Kigali, Rwanda,” GeoJournal, vol. 89, no. 3, p. 107, 24. May 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nduwayezu, E. Ingabire, and J. P. Bizimana, “Measuring disparities in access to district and referral hospitals in the city of Kigali, Rwanda,” Rwanda Journal of Engineering, Science, Technology and Environment, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 2617–2321, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. Manirakiza, L. V. Manirakiza, L. Mugabe, A. Nsabimana, and M. Nzayirambaho, “City Profile: Kigali, Rwanda,” Environment and Urbanization ASIA, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 290–307, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Naeem, Z. Zaheer, S. Tabassum, A. Nazir, and F. Naeem, “Diseases caused by floods with a spotlight on the present situation of unprecedented floods in Pakistan: a short communication,” Annals of Medicine & Surgery, vol. 85, no. 6, pp. 3209–3212, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Haque, “Climate risk responses and the urban poor in the global South: the case of Dhaka’s flood risk in the low-income settlements,” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, vol. 64, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Q. Liu, J. Q. Liu, J. Yuan, W. Yan, W. Liang, M. Liu, and J. Liu, “Association of natural flood disasters with infectious diseases in 168 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019: A worldwide observational study,” Glob Transit, vol. 5, pp. 149–159, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Singh, · Kishan, and S. Rawat, “Mapping flooded areas utilizing Google Earth Engine and open SAR data: a comprehensive approach for disaster response,” Discover Geoscience 2024 2:1, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 1–12, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. R. Rahman and P. K. Thakur, “Detecting, mapping and analysing of flood water propagation using synthetic aperture radar (SAR) satellite data and GIS: A case study from the Kendrapara District of Orissa State of India,” The Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Science, vol. 21, pp. S37–S41, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. P. Dhanabalan, S. A. S. P. Dhanabalan, S. A. Rahaman, and R. Jegankumar, “Flood monitoring using Sentinel-1 SAR data: A case study based on an event of 2018 and 2019 Southern part of Kerala,” in The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XLIV-M-3-2021 ASPRS 2021 Annual Conference, 29 March–, virtual, 2021. 2 April. [CrossRef]

- Kalisch, F. Lagona, and V. Roeber, “Sudden wave flooding on steep rock shores: a clear but hidden danger,” Natural Hazards, vol. 120, no. 3, pp. 3105–3125, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. Dodangeh et al., “Novel hybrid intelligence models for flood-susceptibility prediction: Meta optimization of the GMDH and SVR models with the genetic algorithm and harmony search,” J Hydrol (Amst), vol. 590, p. 125423, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Liu, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “Hybrid Models Incorporating Bivariate Statistics and Machine Learning Methods for Flash Flood Susceptibility Assessment Based on Remote Sensing Datasets,” Remote Sens (Basel), vol. 13, no. 23, p. 4945, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Siahkamari, A. S. Siahkamari, A. Haghizadeh, H. Zeinivand, N. Tahmasebipour, and O. Rahmati, “Spatial prediction of flood-susceptible areas using frequency ratio and maximum entropy models,” Geocarto Int, vol. 33, no. 9, pp. 927–941, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Lee and F. Rezaie, “Data used for GIS-based Flood Susceptibility Mapping,” GEO DATA, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 1–15, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Darabi, B. H. Darabi, B. Choubin, O. Rahmati, A. Torabi Haghighi, B. Pradhan, and B. Kløve, “Urban flood risk mapping using the GARP and QUEST models: A comparative study of machine learning techniques,” J Hydrol (Amst), vol. 569, pp. 142–154, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. Yariyan et al., “Flood susceptibility mapping using an improved analytic network process with statistical models,” Geomatics, Natural Hazards and Risk, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 2282–2314, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, F. B. Y. Li, F. B. Osei, T. Hu, and A. Stein, “Urban flood susceptibility mapping based on social media data in Chengdu city, China,” Sustain Cities Soc, vol. 88, p. 104307, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Q. B. Pham et al., “Current and future projections of flood risk dynamics under seasonal precipitation regimes in the Hyrcanian Forest region,” Geocarto Int, vol. 37, no. 25, pp. 9047–9070, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Breinl, D. Lun, H. Müller-Thomy, and G. Blöschl, “Understanding the relationship between rainfall and flood probabilities through combined intensity-duration-frequency analysis,” J Hydrol (Amst), vol. 602, p. 126759, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Government of Rwanda, Law n°48/2018 of 13/08/2018 on environment. Kigali: Government of Rwanda, 2018. Available online: https://rema.gov.rw/fileadmin/templates/Documents/Law_on_environment.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Izonin, R. Tkachenko, N. Shakhovska, B. Ilchyshyn, and K. K. Singh, “A Two-Step Data Normalization Approach for Improving Classification Accuracy in the Medical Diagnosis Domain,” Mathematics, vol. 10, no. 11, p. 1942, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen, X. Y. Chen, X. Zhang, K. Yang, S. Zeng, and A. Hong, “Modeling rules of regional flash flood susceptibility prediction using different machine learning models,” Front Earth Sci (Lausanne), vol. 11, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Abu El-Magd, G. S. Abu El-Magd, G. Soliman, M. Morsy, and S. Kharbish, “Environmental hazard assessment and monitoring for air pollution using machine learning and remote sensing,” International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, vol. 20, no. 6, pp. 6103–6116, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Henry, D. D. Henry, D. Gorman-Smith, M. Schoeny, and P. Tolan, “‘Neighborhood Matters’: Assessment of Neighborhood Social Processes,” Am J Community Psychol, vol. 54, no. 3–4, pp. 187–204, Dec. 2014. [CrossRef]

- T.-B. Jiang, Z.-W. T.-B. Jiang, Z.-W. Deng, Y.-P. Zhi, H. Cheng, and Q. Gao, “The Effect of Urbanization on Population Health: Evidence from China,” Front Public Health, vol. 9, p. 706982, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Warembourg, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “Urban environment during early-life and blood pressure in young children,” Environ Int, vol. 146, p. 106174, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Xue, X. Xiao, and J. Li, “Identification method and empirical study of urban industrial spatial relationship based on POI big data: a case of Shenyang City, China,” Geography and Sustainability, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 152–162, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Tariverdi, M. M. Tariverdi, M. Nunez-del-Prado, N. Leonova, and J. Rentschler, “Measuring accessibility to public services and infrastructure criticality for disasters risk management,” Scientific Reports 2023 13:1, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 1–16, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- W. Yap and F. Biljecki, “A Global Feature-Rich Network Dataset of Cities and Dashboard for Comprehensive Urban Analyses,” Sci Data, vol. 10, no. 1, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Ndayishimiye et al., “Availability, accessibility, and quality of adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) services in urban health facilities of Rwanda: a survey among social and healthcare providers,” BMC Health Serv Res, vol. 20, no. 1, p. 697, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Ganter, M. M. Ganter, M. Toetzke, and S. Feuerriegel, “Mining Points-of-Interest Data to Predict Urban Inequality: Evidence from Germany and France,” 2022. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media. [CrossRef]

- N. Shrestha, “Factor Analysis as a Tool for Survey Analysis,” Am J Appl Math Stat, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 4–11, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Gulum, C. M. M. A. Gulum, C. M. Trombley, and M. Kantardzic, “A Review of Explainable Deep Learning Cancer Detection Models in Medical Imaging,” Applied Sciences 2021, Vol. 11, Page 4573, vol. 11, no. 10, p. 4573, 21. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- Hall, M. Ohlsson, and T. Rögnvaldsson, “A review of explainable AI in the satellite data, deep machine learning, and human poverty domain,” Patterns, vol. 3, no. 10, p. 100600, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Fazeli, S. Zeynab, S. M. Khatami, and E. Ranjbar, “The Associations Between Urban Form and Major Non-communicable Diseases: A Systematic Review,” J Urban Health, vol. 99, no. 5, pp. 941–958, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Persello and M. Kuffer, “Towards Uncovering Socio-Economic Inequalities Using VHR Satellite Images and Deep Learning,” in IGARSS 2020 - 2020 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, IEEE, Sep. 2020, pp. 3747–3750. [CrossRef]

| Flood-Influencing Factor | Description | Data source |

|---|---|---|

| Elevation | Lower elevation areas are more prone to water accumulation, which increases the likelihood of flooding, while higher elevations typically experience less flooding as water drains downhill [56]. | Extracted from DEM (10 m resolution) obtained from the National Land Authority (NLA) of Rwanda. |

| Slope | Moderate slopes may lead to water accumulation, increasing flood risk, while steep slopes promote rapid runoff, potentially resulting in flash floods [56]. | Extracted from DEM (10 m resolution) obtained from the National Land Authority (NLA) of Rwanda. |

| Aspect | Different aspects can influence vegetation growth and soil moisture levels, impacting flood dynamics; for example, south-facing slopes may dry out faster than north-facing ones [36,57,58,59]. | Extracted from DEM (10 m resolution) obtained from the National Land Authority (NLA) of Rwanda. |

| Land cover | Land cover influences the flow and accumulation of water. For instance, vegetation is important in reducing water runoff and enhancing soil infiltration, which helps mitigate flooding [60]. In contrast, impervious surfaces and barren or open land exacerbate flooding by accelerating water runoff and decreasing water infiltration [61]. | Data were obtained from land cover map of the City of Kigali |

| Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) | High NDVI values indicate dense vegetation that can absorb and slow water movement and mitigate flooding effects; low NDVI values suggest sparse vegetation cover correlating with higher flood susceptibility [62]. | Extracted from Sentinel-2 satellite images. |

| Normalized Difference Built-up Index (NDBI) | High NDBI values indicate extensive urban development with impermeable surfaces that exacerbate flooding by increasing surface runoff during heavy rains [63]. | Extracted from Sentinel-2 satellite images. |

| Cumulative Rainfall | Excessive cumulative rainfall can overwhelm drainage systems, particularly in areas with low drainage density or poor soil permeability, leading to increased flooding risks [64]. | Computed from Climate Hazards Group Infrared Precipitation with Station (CHIRPS) data. |

| Drainage Density | Low drainage density can hinder effective water channeling during floods, increasing the likelihood of flooding in those areas [65]. | Computed from drainage networks data obtained from the City of Kigali. |

| Distance from drainage | Areas that are close to drainage systems, including rivers and streams, are more prone to experience flooding in the event that the drainage system is overloaded with water [62]. | Computed based on drainage network data obtained from the City of Kigali. We considered a distance of 10 m from each river and stream based on Law n°48/2018 of 13/08/2018 on the environment in Rwanda [66]. |

| Categories | Socio-economic Factors/indicators | Description | Data source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure sensitivity | Population density | Higher population density often leads to increased exposure to hazards such as flooding [6]. In densely populated regions, the concentration of individuals exacerbates the effects of these hazards, as more people are simultaneously affected by limited resources and emergency services during disasters [71]. | Obtained from Worldpop a database for global population and their characteristics at high resolution. |

| Population below 5 years | Young children are not physically able to resist during the flood event since their bodies adapt less efficiently than adults, increasing their risk during flood event [72]. | Obtained from Worldpop. | |

| Population above 65 years | Older people are particularly sensitive to natural hazards people are not physically able to resist during the flood event and are likely suffering from pre-existing health conditions that can be exacerbated by environmental factors, making them a high-risk group during disasters [40]. | Obtained from Worldpop. | |

| Adaptive capacity | Road network | The road network is crucial for understanding human and socio-economic interactions, particularly in accessing essential services [73]. Access to road networks facilitates quicker responses during emergencies and enhances the overall adaptive capacity of communities [74]. | Extracted from OpenStreetMap (OSM), a global open-source database where volunteers map geographic elements [75]. |

| Access to primary healthcare facilities, | Access to healthcare facilities enables quicker medical responses during disasters. When facilities are within reach, individuals can receive timely treatment for injuries or health issues that arise during emergencies [76]. Primary healthcare facilities serve as the initial point of entry for individuals seeking healthcare services. | Computed from the spatial distribution of primary healthcare facilities available from the Ministry of Health of Rwanda and downloaded from the national spatial data geoportal. | |

| Points of interest (POIs) | Socio-economic related POIs, including economic and social activities, were used to describe the availability of socio-economic activities across the city of Kigali [77]. In total, 804 POIs were extracted and grouped into eight categories, namely hospitality services, education, amenities, shopping centers, financial services, culture and recreation, auto services, and health. | POIs were obtained from OSM. |

| Model | AUC | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLP | 0.902 | 0.85 | 0.83 | 0.90 | 0.86 |

| SVM | 0.885 | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.90 | 0.84 |

| RF | 0.884 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.87 | 0.82 |

| XGBoost | 0.883 | 0.80 | 0.77 | 0.88 | 0.82 |

| City | Model | AUC | MAE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kampala | MLP | 0.475 | 0.511 |

| RF | 0.473 | 0.530 | |

| SVM | 0.455 | 0.547 | |

| XGBoost | 0.519 | 0.484 | |

| Dar es Salaam | MLP | 0.402 | 0.523 |

| RF | 0.403 | 0.590 | |

| SVM | 0.447 | 0.535 | |

| XGBoost | 0.387 | 0.605 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).