Submitted:

21 August 2025

Posted:

22 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. DNA Extraction and Sequencing

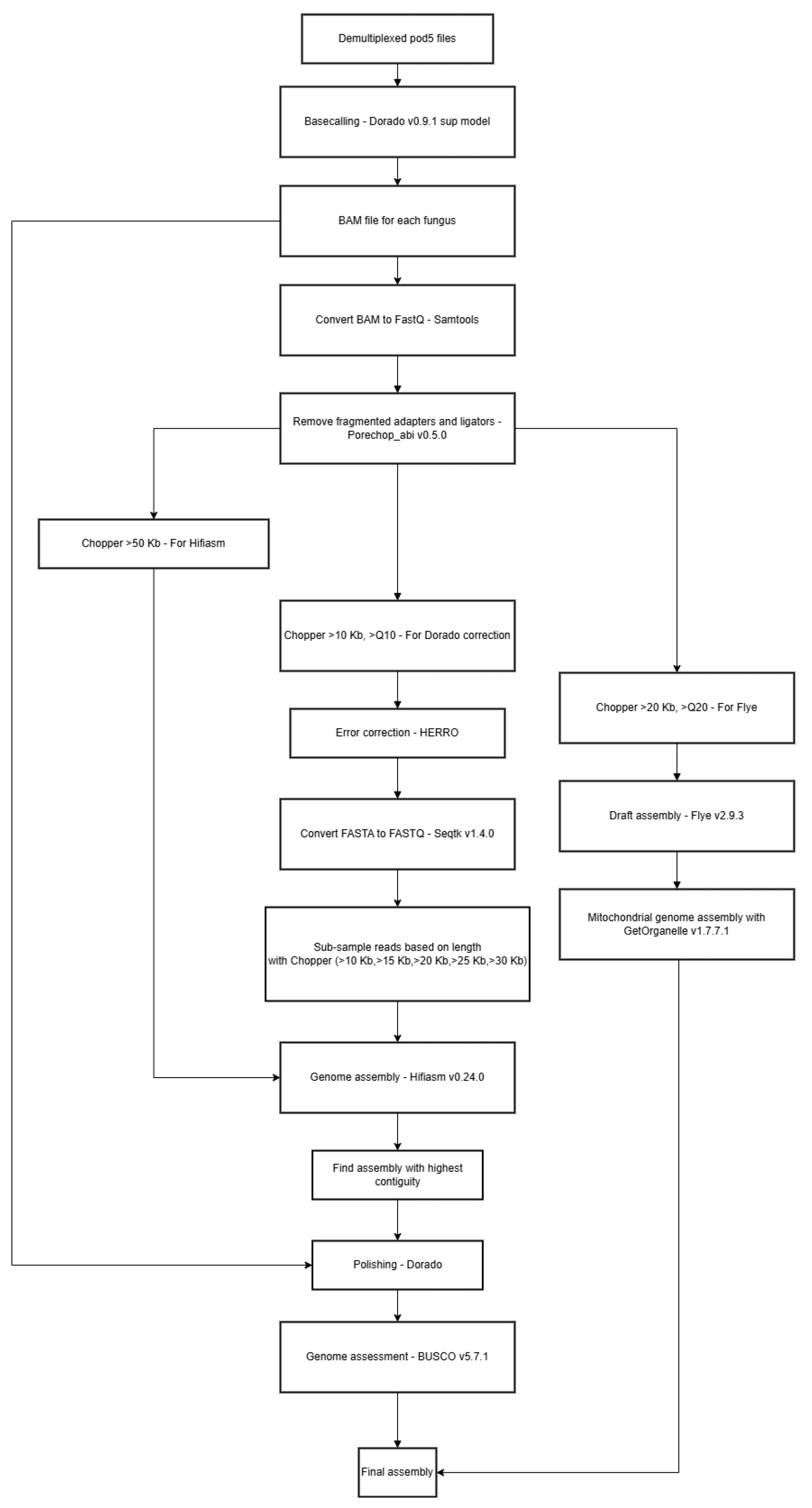

2.2. Snakemake Workflow for High Quality Assembly

2.3. Phylogenetic Determination with Universal Fungal Core Genes

2.4. Whole-Genome Alignment

2.5. Gene prediction and functional annotation

2.6. Validation of Workflow

3. Results

3.1. Snakemake Workflow Output and Assembly Stats

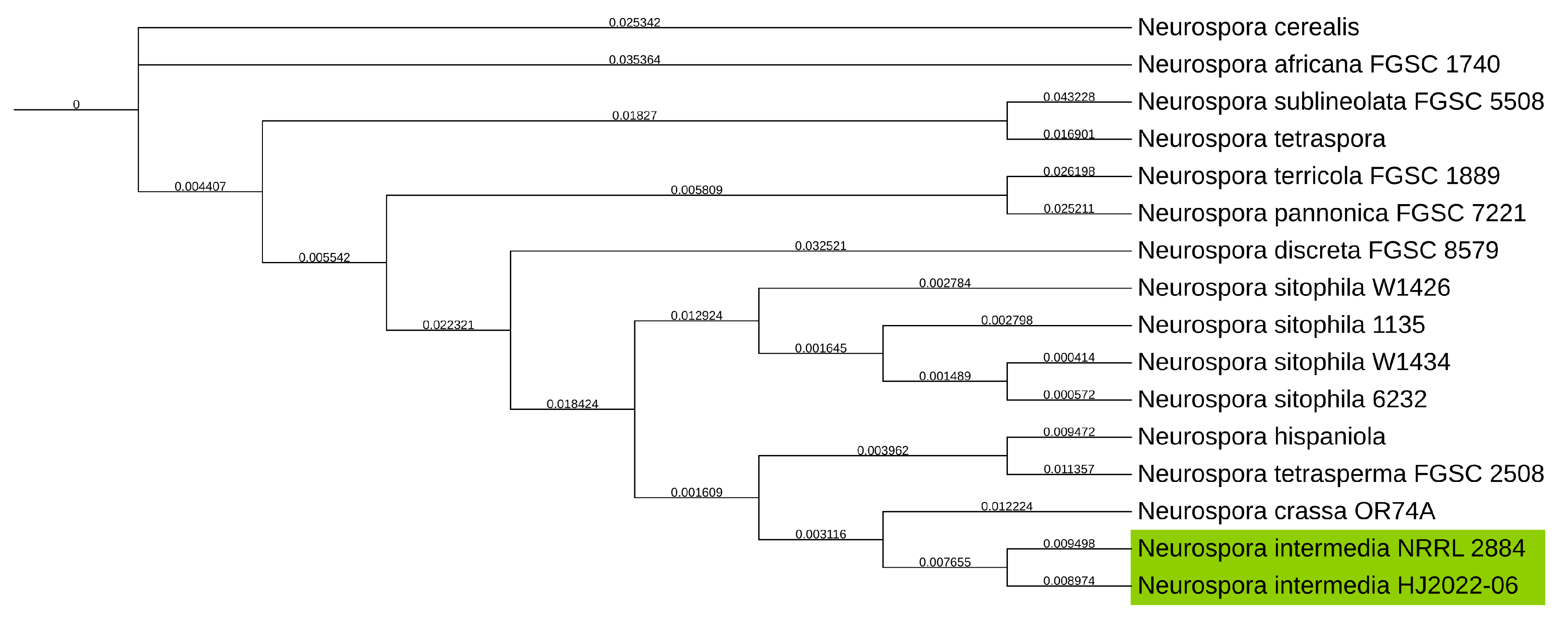

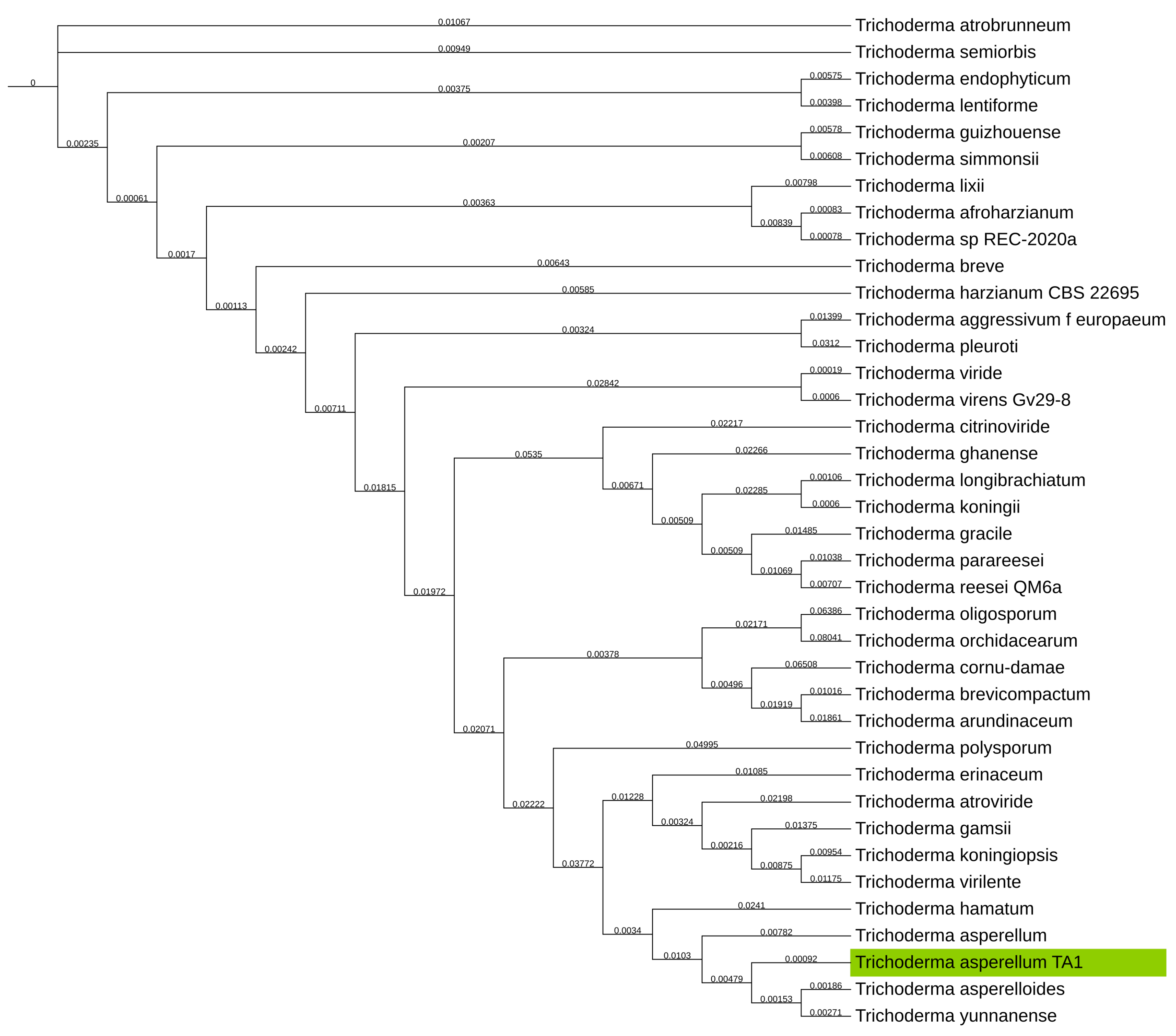

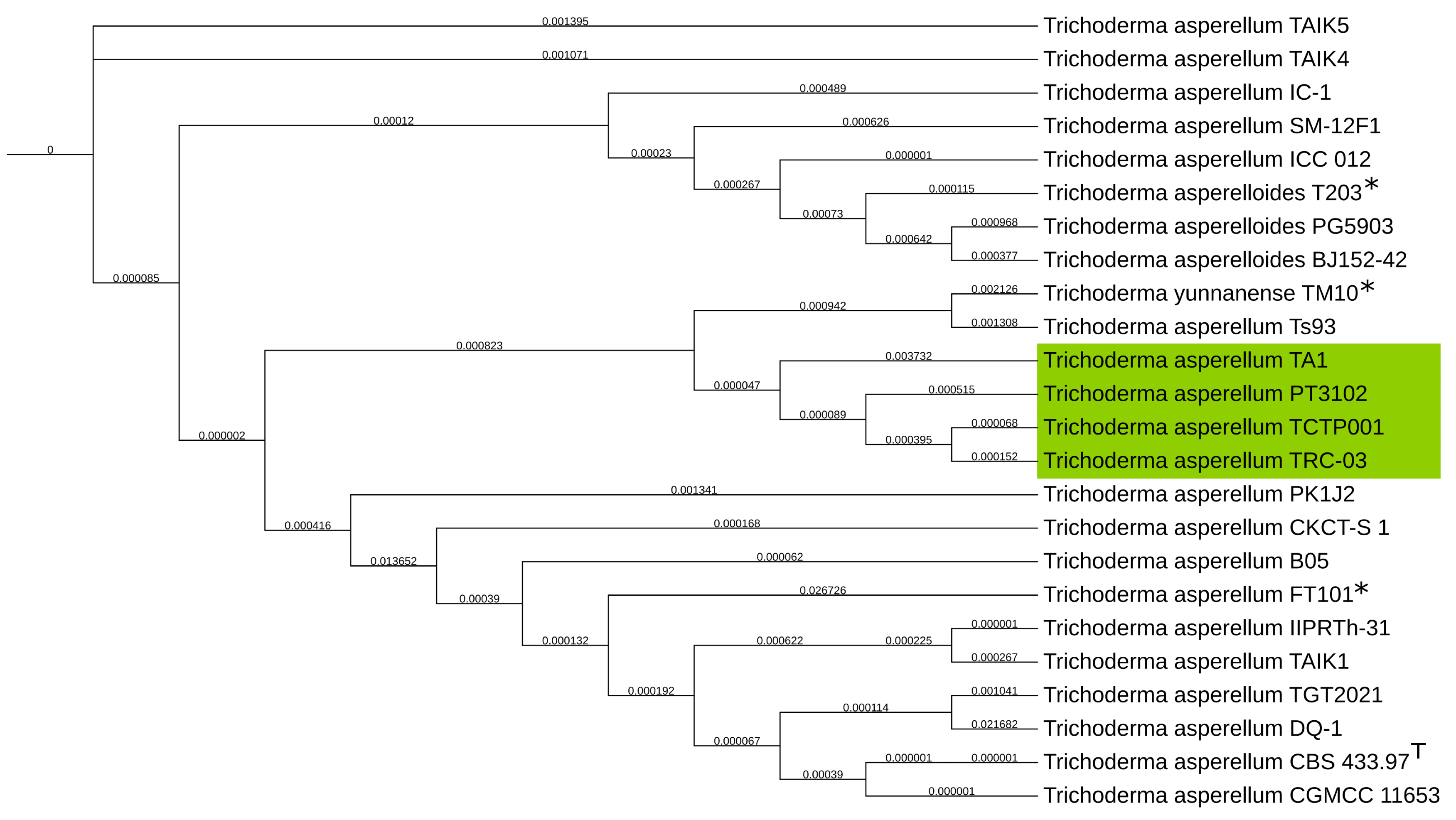

3.2. Phylogenetic Determination

3.3. Whole Genome Alignment with High Quality Closest Neighbor

3.4. Predicted Genes and Telomeres

3.5. Workflow Validation

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BGCs | Biosynthetic gene clusters |

| BUSCO | Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs |

| CAZymes | Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes |

| CTAB | Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide |

| GSI | Genealogical Sorting Index |

| CDS | Coding sequence |

| HERRO | Haplotype-aware error correction |

| HMW | High molecular weight DNA |

| HPC | High-performance computing |

| HQ | High quality |

| NRPSs | Nonribosomal peptide synthetases |

| PKSs | Polyketide synthases |

| RiPPs | Post-translationally modified peptides |

| T2T | Telomere to telomere |

| Tidk | Telomere identification toolkit |

| UFCG | Universal Fungal Core Genes |

| YES | Yeast extract sucrose |

| YPG | Yeast extract Peptone Glucose |

References

- Galagan, J.E.; Calvo, S.E.; Borkovich, K.A.; Selker, E.U.; Read, N.D.; Jaffe, D.; FitzHugh, W.; Ma, L.J.; Smirnov, S.; Purcell, S.; et al. The genome sequence of the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa. Nature 2003, 422, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarze, K.; Buchanan, J.; Fermont, J.M.; Dreau, H.; Tilley, M.W.; Taylor, J.M.; Antoniou, P.; Knight, S.J.; Camps, C.; Pentony, M.M.; et al. The complete costs of genome sequencing: a microcosting study in cancer and rare diseases from a single center in the United Kingdom. Genetics in Medicine 2020, 22, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heather, J.M.; Chain, B. The sequence of sequencers: The history of sequencing DNA. Genomics 2016, 107, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satam, H.; Joshi, K.; Mangrolia, U.; Waghoo, S.; Zaidi, G.; Rawool, S.; Thakare, R.P.; Banday, S.; Mishra, A.K.; Das, G.; et al. Next-Generation Sequencing Technology: Current Trends and Advancements. Biology 2023, 12, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Genome assembly in the telomere-to-telomere era. Nature Reviews Genetics 2024, 25, 658–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yao, G.; Chen, W.; Ayhan, D.H.; Wang, X.; Sun, J.; Yi, S.; Meng, T.; Chen, S.; Geng, X.; A gap-free genome assembly of Fusarium oxysporum f., sp.; et al. conglutinans, a vascular wilt pathogen. Scientific Data 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yang, J.; Ji, X.; Liu, J.; Yin, C.; Bhadauria, V.; Zhao, W.; Peng, Y.L. First telomere-to-telomere gapless assembly of the rice blast fungus Pyricularia oryzae. Scientific Data 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, G.; Chen, W.; Sun, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Meng, T.; Zhang, L.; Guo, L. Gapless genome assembly of Fusarium verticillioides, a filamentous fungus threatening plant and human health. Scientific Data 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarasinghe, S.L.; Su, S.; Dong, X.; Zappia, L.; Ritchie, M.E.; Gouil, Q. Opportunities and challenges in long-read sequencing data analysis. Genome Biology 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, S.; Bao, Z.; Guarracino, A.; Ou, S.; Goodwin, S.; Jenike, K.M.; Lucas, J.; McNulty, B.; Park, J.; Rautiainen, M.; et al. Gapless assembly of complete human and plant chromosomes using only nanopore sequencing. Genome Research 2024, 34, 1919–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanojevic, D.; Lin, D.; Nurk, S.; Florez De Sessions, P.; Sikic, M. Telomere-to-Telomere Phased Genome Assembly Using HERRO-Corrected Simplex Nanopore Reads. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigova, E.A.; Dvorianinova, E.M.; Arkhipov, A.A.; Rozhmina, T.A.; Kudryavtseva, L.P.; Kaplun, A.M.; Bodrov, Y.V.; Pavlova, V.A.; Borkhert, E.V.; Zhernova, D.A.; et al. Nanopore Data-Driven T2T Genome Assemblies of Colletotrichum lini Strains. Journal of Fungi 2024, 10, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cechova, M. Probably Correct: Rescuing Repeats with Short and Long Reads. Genes 2020, 12, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiti, A.K.; Bouvagnet, P. Assembling and gap filling of unordered genome sequences through gene checking. Genome Biology 2001, 2, preprint0008.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaldi, N.; Seifuddin, F.T.; Turner, G.; Haft, D.; Nierman, W.C.; Wolfe, K.H.; Fedorova, N.D. SMURF: Genomic mapping of fungal secondary metabolite clusters. Fungal Genetics and Biology 2010, 47, 736–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robey, M.T.; Caesar, L.K.; Drott, M.T.; Keller, N.P.; Kelleher, N.L. An interpreted atlas of biosynthetic gene clusters from 1, 000 fungal genomes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Leahy, I.; Collemare, J.; Seidl, M.F. Genomic Localization Bias of Secondary Metabolite Gene Clusters and Association with Histone Modifications in Aspergillus. Genome Biology and Evolution 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, C.; Keller, N.P.; Rokas, A. Unearthing fungal chemodiversity and prospects for drug discovery. Current Opinion in Microbiology 2019, 51, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Xu, H.; Liu, Y.; Hong, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhou, C.; Tao, L. Computational advances in biosynthetic gene cluster discovery and prediction. Biotechnology Advances 2025, 79, 108532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, L.; Barrett, K.; Meyer, A.S. New Method for Identifying Fungal Kingdom Enzyme Hotspots from Genome Sequences. Journal of Fungi 2021, 7, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Füting, P.; Barthel, L.; Cairns, T.C.; Briesen, H.; Schmideder, S. Filamentous fungal applications in biotechnology: a combined bibliometric and patentometric assessment. Fungal Biology and Biotechnology 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijaya, C.H.; Nuraida, L.; Nuramalia, D.R.; Hardanti, S.; Świąder, K. Oncom: A Nutritive Functional Fermented Food Made from Food Process Solid Residue. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 10702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, G.; Hao, L.; Xin, T.; Gan, Y.; Lou, Q.; Xu, W.; Song, J. Analysis of Whole-Genome facilitates rapid and precise identification of fungal species. Frontiers in Microbiology 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartholomew, H.P.; Gottschalk, C.; Cooper, B.; Bukowski, M.R.; Yang, R.; Gaskins, V.L.; Luciano-Rosario, D.; Fonseca, J.M.; Jurick, W.M. Omics-Based Comparison of Fungal Virulence Genes, Biosynthetic Gene Clusters, and Small Molecules in Penicillium expansum and Penicillium chrysogenum. Journal of Fungi 2024, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Cerezo, S.; de Vries, R.P.; Garrigues, S. Strategies for the Development of Industrial Fungal Producing Strains. Journal of Fungi 2023, 9, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, C.; Sørensen, T.; Westphal, K.R.; Fechete, L.I.; Sondergaard, T.E.; Sørensen, J.L.; Nielsen, K.L. High molecular weight DNA extraction methods lead to high quality filamentous ascomycete fungal genome assemblies using Oxford Nanopore sequencing. Microbial Genomics 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Holt, K.E. Performance of neural network basecalling tools for Oxford Nanopore sequencing. Genome Biology 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanoporetech. GitHub - dorado. https://github.com/nanoporetech/dorado, 2022. [Accessed 14-08-2025].

- Köster, J.; Rahmann, S. Snakemake—a scalable bioinformatics workflow engine. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 2520–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonenfant, Q.; Noé, L.; Touzet, H. Porechop_ABI: discovering unknown adapters in Oxford Nanopore Technology sequencing reads for downstream trimming. Bioinformatics Advances 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Coster, W.; Rademakers, R. NanoPack2: population-scale evaluation of long-read sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2023, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmogorov, M.; Yuan, J.; Lin, Y.; Pevzner, P.A. Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. Nature Biotechnology 2019, 37, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Concepcion, G.T.; Feng, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nature Methods 2021, 18, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.J.; Yu, W.B.; Yang, J.B.; Song, Y.; dePamphilis, C.W.; Yi, T.S.; Li, D.Z. GetOrganelle: a fast and versatile toolkit for accurate de novo assembly of organelle genomes. Genome Biology 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, M. Rasusa: Randomly subsample sequencing reads to a specified coverage. Journal of Open Source Software 2022, 7, 3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- lh3. GitHub - lh3/seqtk: Toolkit for processing sequences in FASTA/Q formats — github.com. https://github.com/lh3/seqtk, 2016. [Accessed 21-03-2025].

- Shen, W.; Sipos, B.; Zhao, L. SeqKit2: A Swiss army knife for sequence and alignment processing. iMeta 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manni, M.; Berkeley, M.R.; Seppey, M.; Simão, F.A.; Zdobnov, E.M. BUSCO Update: Novel and Streamlined Workflows along with Broader and Deeper Phylogenetic Coverage for Scoring of Eukaryotic, Prokaryotic, and Viral Genomes. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2021, 38, 4647–4654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Gilchrist, C.L.M.; Chun, J.; Steinegger, M. UFCG: database of universal fungal core genes and pipeline for genome-wide phylogenetic analysis of fungi. Nucleic Acids Research 2022, 51, D777–D784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, N.A.; Cox, E.; Holmes, J.B.; Anderson, W.R.; Falk, R.; Hem, V.; Tsuchiya, M.T.N.; Schuler, G.D.; Zhang, X.; Torcivia, J.; et al. Exploring and retrieving sequence and metadata for species across the tree of life with NCBI Datasets. Scientific Data 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svedberg, J.; Vogan, A.A.; Rhoades, N.A.; Sarmarajeewa, D.; Jacobson, D.J.; Lascoux, M.; Hammond, T.M.; Johannesson, H. An introgressed gene causes meiotic drive inNeurospora sitophila. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Research 2024, 52, W78–W82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtz, S.; Phillippy, A.; Delcher, A.L.; Smoot, M.; Shumway, M.; Antonescu, C.; Salzberg, S.L. Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biology 2004, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimoyama, Y. pyCirclize: Circular visualization in Python. https://github.com/moshi4/pyCirclize, 2022. [Accessed 08-04-2025].

- Krzywinski, M.; Schein, J.; Birol, İ.; Connors, J.; Gascoyne, R.; Horsman, D.; Jones, S.J.; Marra, M.A. Circos: An information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Research 2009, 19, 1639–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.; Zaretskaya, I.; Raytselis, Y.; Merezhuk, Y.; McGinnis, S.; Madden, T.L. NCBI BLAST: a better web interface. Nucleic Acids Research 2008, 36, W5–W9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J.M.; Stajich, J. Funannotate v1.8.1: Eukaryotic genome annotation, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Blin, K.; Shaw, S.; Augustijn, H.E.; Reitz, Z.L.; Biermann, F.; Alanjary, M.; Fetter, A.; Terlouw, B.R.; Metcalf, W.W.; Helfrich, E.J.N.; et al. antiSMASH 7.0: new and improved predictions for detection, regulation, chemical structures and visualisation. Nucleic Acids Research 2023, 51, W46–W50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdobnov, E.M.; Apweiler, R. GitHub - ebi-pf-team/interproscan: Genome-scale protein function classification — github.com. https://github.com/ebi-pf-team/interproscan, 2001. [Accessed 08-04-2025].

- Zdobnov, E.M.; Apweiler, R. InterProScan – an integration platform for the signature-recognition methods in InterPro. Bioinformatics 2001, 17, 847–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.R.; Manuel Gonzalez de La Rosa, P.; Blaxter, M. tidk: a toolkit to rapidly identify telomeric repeats from genomic datasets. Bioinformatics 2025, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyčka, M.; Bubeník, M.; Závodník, M.; Peska, V.; Fajkus, P.; Demko, M.; Fajkus, J.; Fojtová, M. TeloBase: a community-curated database of telomere sequences across the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Research 2023, 52, D311–D321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalamun, M.; Schmoll, M. Trichoderma – genomes and genomics as treasure troves for research towards biology, biotechnology and agriculture. Frontiers in Fungal Biology 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieloch, W. Chromosome visualisation in filamentous fungi. Journal of Microbiological Methods 2006, 67, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.M.; Baek, J.H.; Choi, D.G.; Jeon, M.S.; Eyun, S.i.; Jeon, C.O. Comparative pangenome analysis of Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus oryzae reveals their phylogenetic, genomic, and metabolic homogeneity. Food Microbiology 2024, 119, 104435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbert, P.B.; Henikoff, S. What makes a centromere? Experimental Cell Research 2020, 389, 111895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaccaron, A.Z.; Stergiopoulos, I. The dynamics of fungal genome organization and its impact on host adaptation and antifungal resistance. Journal of Genetics and Genomics 2025, 52, 628–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, J.; Pratas, D.; Videira, A.; Pereira, F. Revisiting the Neurospora crassa mitochondrial genome. Letters in Applied Microbiology 2021, 73, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, B.; Buckler, E.S.; Stitzer, M.C. New whole-genome alignment tools are needed for tapping into plant diversity. Trends in Plant Science 2024, 29, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.C.; Lin, T.C.; Chen, C.L.; Liu, H.C.; Lin, H.N.; Chao, J.L.; Hsieh, C.H.; Ni, H.F.; Chen, R.S.; Wang, T.F. Complete Genome Sequences and Genome-Wide Characterization of Trichoderma Biocontrol Agents Provide New Insights into their Evolution and Variation in Genome Organization, Sexual Development, and Fungal-Plant Interactions. Microbiology Spectrum 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genus | Method | Coverage [X] | N50 [Kb] | Average Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurospora | Raw-Basecalled | 194.56 | 11.375 | 20.31 |

| Neurospora | Pre-Correction | 104.67 | 21.338 | 20.58 |

| Neurospora | Corrected | 94.05 | 20.317 | n/a |

| Neurospora | Contiguity | 33.68 | 34.920 | n/a |

| Neurospora | Ultra-long | 7.53 | 59.306 | 20.14 |

| Neurospora | Flye | 42.53 | 30.951 | 23.34 |

| Trichoderma | Raw-Basecalled | 66.34 | 22.114 | 20.35 |

| Trichoderma | Pre-Correction | 49.06 | 29.752 | 20.56 |

| Trichoderma | Corrected | 44.78 | 27.294 | n/a |

| Trichoderma | Contiguity | 43.60 | 27.993 | n/a |

| Trichoderma | Ultra-long | 9.37 | 61.816 | 20.27 |

| Trichoderma | Flye | 26.45 | 37.005 | 23.45 |

| Aspergillus | Raw-Basecalled | 238.93 | 11.980 | 20.94 |

| Aspergillus | Pre-Correction | 136.76 | 19.340 | 21.13 |

| Aspergillus | Corrected | 118.29 | 18.200 | n/a |

| Aspergillus | Contiguity | 114.65 | 18.633 | n/a |

| Aspergillus | Ultra-long | 7.60 | 59.144 | 20.40 |

| Aspergillus | Flye | 51.27 | 29.417 | 23.74 |

| Genus | Contigs | Size [Mb] | C [%] | S [%] | D [%] | F [%] | M [%] | n | DB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurospora | 7(+1)1 | 40 | 99.4 | 99.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 758 | fungi_odb10 |

| Trichoderma | 7 | 37 | 98.8 | 98.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 758 | fungi_odb10 |

| Aspergillus | 8 | 38 | 98.7 | 98.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 758 | fungi_odb10 |

| Strain | Genes | CAZymes | PKSs | NRPSs/NRPSs-like | Terpene synthases | RiPPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N. intermedia NRRL 2884 | 8790 | 345 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 4 |

| T. asperellum TA1 | 9805 | 401 | 17 | 18 | 10 | 3 |

| A. oryzae CBS 466.91 | 13042 | 579 | 28 | 32 | 12 | 6 |

| Sample | Contigs | Size [Mb] | C [%] | S [%] | D [%] | F [%] | M [%] | DB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. lini 394-2 1 | 13 | 53.56 | 96.8 | 96.6 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 2.6 | glomerellales_odb10 |

| C. lini 394-2 | 13 | 53.69 | 96.8 | 96.6 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 2.6 | glomerellales_odb10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).