Submitted:

04 December 2023

Posted:

05 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Genome Sequencing and Assembly

2.2. Evaluation of Genome Quality and Completeness

2.3. Genome Annotation

2.4. Compilation of Ecological and Biological Metadata for FSP34 and KS17

3. Results

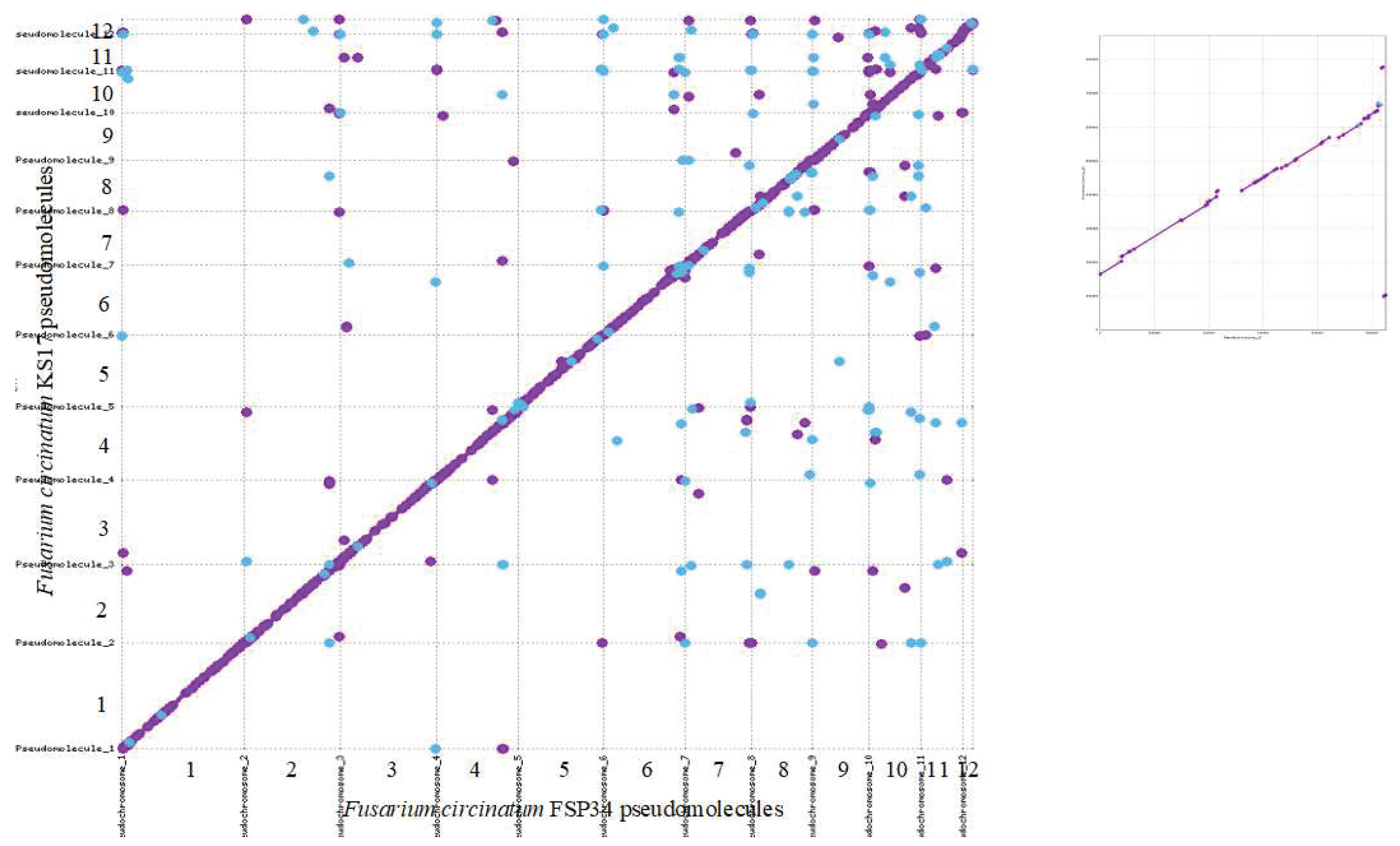

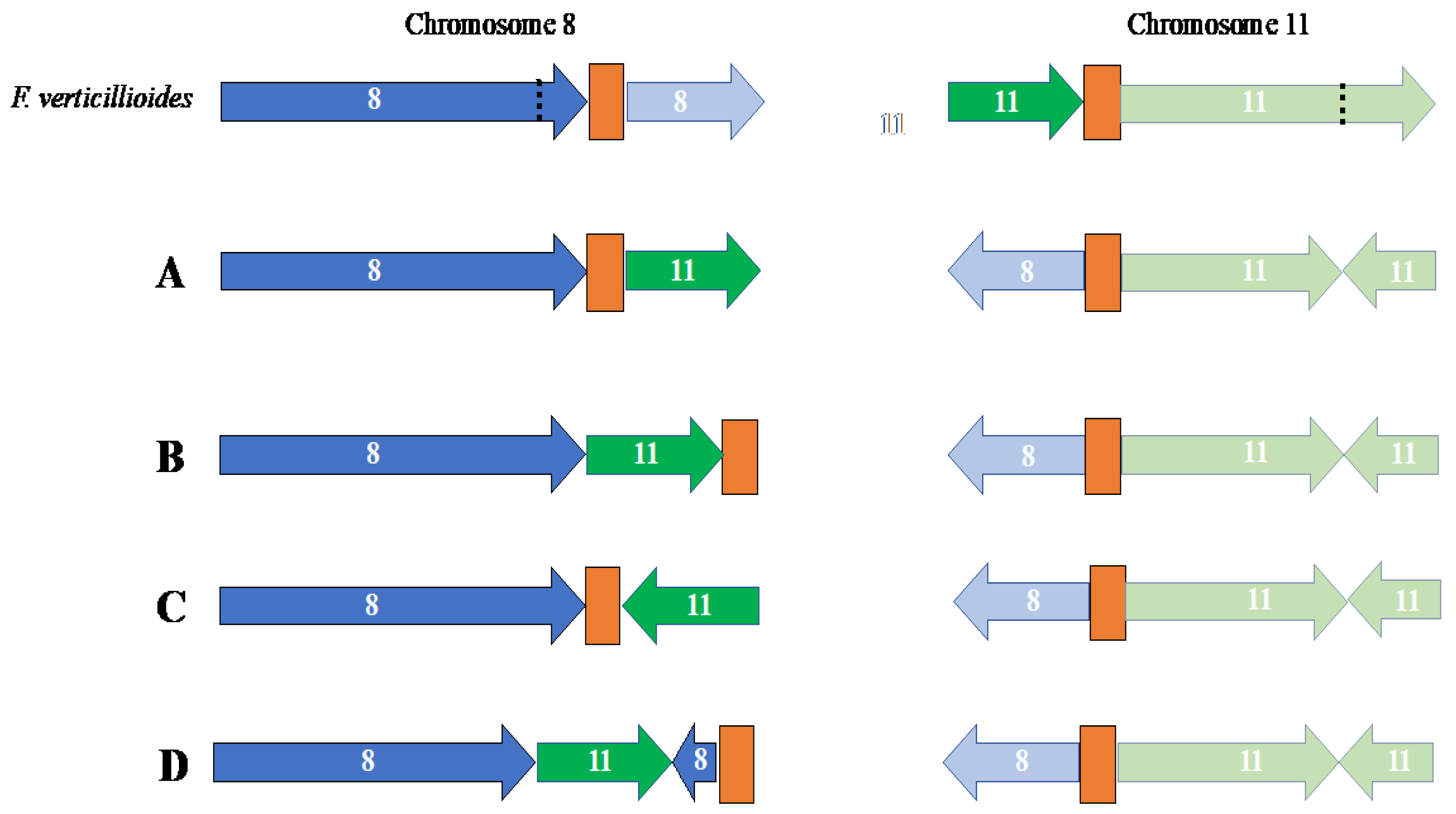

3.1.1. Chromosome-Level Assemblies for FSP34 and KS17

3.1.2. Identification of Telomeres and Centromeres

3.1.3. Genome Completeness and Gene Content

3.1.4. Genome Repetitiveness and TE Content

3.1.5. Detailed Source and Biological Information for KS17 and FSP34

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Engel, S.R.; Dietrich, F.S.; Fisk, D.G.; Binkley, G.; Balakrishnan, R.; Costanzo, M.C.; Dwight, S.S.; Hitz, B.C.; Karra, K.; Nash, R.S.; et al. The reference genome sequence of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Then and Now. G3: Genes | Genomes | Genetics 2014, 4, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galagan, J.E.; Calvo, S.E.; Borkovich, K.A.; Selker, E.U.; Read, N.D.; Jaffe, D.; FitzHugh, W.; Ma, L.-J.; Smirnov, S.; Purcell, S.; et al. The genome sequence of the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa. Nature 2003, 422, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigoriev, I.V.; Nikitin, R.; Haridas, S.; Kuo, A.; Ohm, R.; Otillar, R.; Riley, R.; Salamov, A.; Zhao, X.; Korzeniewski, F.; et al. Mycocosm portal: Gearing up for 1000 fungal genomes. Nucleic Acids Research 2014, 42, D699–D704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.-J.; Van der Does, H.C.; Borkovich, K.A.; Coleman, J.J.; Daboussi, M.-J.; Di Pietro, A.; Dufresne, M.; Freitag, M.; Grabherr, M.; Henrissat, B.; et al. Comparative genomics reveals mobile pathogenicity chromosomes in Fusarium. Nature 2010, 464, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Sengupta, A.; Ghosh, R.; Agarwal, G.; Tarafdar, A.; Nagavardhini, A.; Pande, S.; Varshney, R.K. Genome wide transcriptome profiling of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris conidial germination reveals new insights into infection-related genes. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 37353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, K.K. Fungal genome sequencing: Basic biology to biotechnology. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 2016, 36, 743–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyauchi, S.; Kiss, E.; Kuo, A.; Drula, E.; Kohler, A.; Sánchez-García, M.; Morin, E.; Andreopoulos, B.; Barry, K.W.; Bonito, G.; et al. Large-scale genome sequencing of mycorrhizal fungi provides insights into the early evolution of symbiotic traits. Nature Communications 2021, 11, 5125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.-J.; Geiser, D.M.; Proctor, R.; Rooney, A.P.; O'Donnell, K.; Trail, F.; Gardiner, D.M.; Manners, J.M.; Kazan, K. Fusarium pathogenomics. Annual Review of Microbiology 2013, 67, 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Steenwyk, J.L.; Chang, Y.; Wang, Y.; James, T.Y.; Stajich, J.E.; Spatafora, J.W.; Groenewald, M.; Dunn, C.W.; Hittinger, C.T.; et al. A genome-scale phylogeny of the kingdom Fungi. Current Biology 2021, 31, 1653–1665.e1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coetzee, M.P.A.; Santana, Q.C.; Steenkamp, E.T.; Wingfield, B.D.; Wingfield, M.J. Fungal genomes enhance our understanding of the pathogens affecting trees cultivated in Southern Hemisphere plantations. Southern Forests 2020, 82, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delulio, G.A.; Guo, L.; Zhang, Y.; Goldberg, J.M. Kinome expansion in the Fusarium oxysporum species complex driven by accessory chromosomes. mSphere 2018, 3, e00231–e00218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiemann, P.; Sieber, C.M.K.; Von Bargen, K.W.; Studt, L.; Niehaus, E.-M.; Hub, K.; Michielse, C.B.; Albermann, S.; Wagner, D.; Espino, J.J.; et al. Unleashing the cryptic genome: Genome-wide analyses of the rice pathogen Fusarium fujikuroi reveal complex regulation of secondary metabolism and novel metabolites. PLoS Pathogens 2013, 9, e1003475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fokkens, L.; Guo, L.; Dora, S.; Wang, B.; Ye, K.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, C.; Croll, D. A chromosome-scale genome assembly for the Fusarium oxysporum strain Fo5176 to establish a model Arabidopsis-fungal pathosystem. G3: Genes | Genomes | Genetics 2020, 10, 3549–3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niehaus, E.-M.; Münsterkötter, M.; Proctor, R.H.; Brown, D.W.; Sharon, A.; Idan, Y.; Oren-Young, L.; Sieber, C.M.; Novák, O.; Pĕnčík, A.; et al. Comparative "omics"of the Fusarium fujikuroi species complex highlights differences in genetic potential and metabolite synthesis. Genome Biology and Evolution 2017, 8, 3574–3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiser, D.M.; Aoki, T.; Bacon, C.W.; Baker, S.E.; Bhattacharyya, M.K.K.; Brandt, M.E.; Brown, D.W.; Burgess, L.W.; Chulze, S.N.; Coleman, J.J.; et al. One fungus, one name: Defining the genus Fusarium in a scientifically robust way that preserves longstanding use. Phytopathology 2013, 103, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drenkhan, R.; Ganley, B.; Martín-García, J.; Vahalík, P.; Adamson, K.; Adamčíková, K.; Ahumada, R.; Blank, L.; Bragança, H.; Capretti, P.; et al. Global geographic distribution and host range of Fusarium circinatum, the causal agent of pine pitch canker. Forests 2020, 11, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingfield, M.J.; Hammerbacher, A.; Ganley, R.J.; Steenkamp, E.T.; Gordon, T.R.; Wingfield, B.D.; Coutinho, T.A. Pitch canker caused by Fusarium circinatum - a growing threat to pine plantations and forests worldwide. Australasian Plant Pathology 2008, 37, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingfield, B.D.; Steenkamp, E.T.; Santana, Q.C.; Coetzee, M.P.A.; Bam, S.; Barnes, I.; Beukes, C.W.; Chan, W.Y.; De Vos, L.; Fourie, G.; et al. First fungal genome sequence from Africa: A preliminary analysis. South African Journal of Science 2012, 108, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingfield, B.D.; Liu, M.; Nguyen, H.D.T.; Lane, F.A.; Morgan, S.W.; De Vos, L.; Wilken, P.M.; Duong, T.A.; Aylward, J.; Coetzee, M.P.A. ; et al. Nine draft genome sequences of Claviceps purpurea s. lat., including C. arundinis, C. humidiphila, and C. cf. spartinea, pseudomolecules for the pitch canker pathogen Fusarium circinatum, draft genome of Davidsoniella eucalypti, Grosmannia galeiformis, Quambalaria euclaypti, and Teratospahaeria destructans. IMA Fungus 2018, 9, 401–418. [CrossRef]

- van Wyk, S.; Wingfield, B.D.; De Vos, L.; Santana, Q.C.; Van der Merwe, N.A.; Steenkamp, E.T. Multiple independent origins for a subtelomeric locus associated with growth rate in Fusarium circinatum. IMA Fungus 2018, 9, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana, Q.C.; Coetzee, M.P.A.; Steenkamp, E.T.; Mlonyeni, O.X.; Hammond, G.N.A.; Wingfield, M.J.; Wingfield, B.D. Microsatellite discovery by deep sequencing of enriched genomic libraries. BioTechniques 2009, 46, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phasha, M.M.; Wingfield, B.D.; Wingfield, M.J.; Coetzee, M.P.A.; Hammerbacher, A.; Steenkamp, E.T. Deciphering the effect of FUB1 disruption on fusaric acid production and pathogenicity in Fusarium circinatum. Fungal Biology 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phasha, M.M.; Wingfield, M.J.; Wingfield, B.D.; Coetzee, M.P.A.; Hallen-Adams, H.; Fru, F.; Swalarsk-Parry, B.S.; Yilmaz, N.; Duong, T.A.; Steenkamp, E.T. Ras2 is important for growth and pathogenicity in Fusarium circinatum. Fungal Genetics and Biology 2021, 150, 103541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vos, L.; Myburg, A.A.; Wingfield, M.J.; Desjardins, A.E.; Gordon, T.R.; Wingfield, B.D. Complete genetic linkage maps from an interspecific cross between Fusarium circinatum and Fusarium subglutinans. Fungal Genetics and Biology 2007, 44, 701–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, L.; Steenkamp, E.T.; Martin, S.H.; Santana, Q.C.; Fourie, G.; Van der Merwe, N.A.; Wingfield, M.J.; Wingfield, B.D. Genome-wide macrosynteny among Fusarium species within the Gibberella fujikuroi complex revealed by amplified fragment length polymorphisms. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, J.; Wu, H.-C.; Jayasinghe, L.; Patel, A.; Reid, S.; Bayley, H. Continuous base identification for single-molecule nanopore DNA sequencing. Nature Nanotechnology 2009, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, A.; Holmes, N.; Rakyan, V.; Loose, M. BulkVis: A graphical viewer for Oxford nanopore bulk FAST5 files. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 2193–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laver, T.; Harrison, J.; O'Neill, P.A.; Moore, K.; Farbos, A.; Paszkiewicz, K.; Studholme, D.J. Assessing the performance of the Oxford Nanopore Technologies MinION. Biomolecular Detection and Quantification 2015, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saud, Z.; Kortsinoglou, A.M.; Kouvelis, V.N.; Butt, T.M. Telomere length de novo assembly of all 7 chromosomes and mitogenome sequencing of the model entomopathogenic fungus, Metarhizium brunneum, by means of a novel assembly pipeline. BMC Genomics 2021, 22, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Liang, X.; Gleason, M.L.; Hsiang, T.; Zhang, R.; Sun, G. A chromosome-scale assembly of the smallest Dothideomycete genome reveals a unique genome compaction mechanism in filamentous fungi. BMC Genomics 2020, 21, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crestana, G.S.; Taniguti, L.M.; dos Santos, C.P.; Benevenuto, J.; Ceresini, P.C.; Carvalho, G.; Kitajima, J.P.; Monteiro-Vitorello, C.B. Complete chromosome-scale genome sequence resource for Sporisorium panici-leucophaei, the causal agent of sourgrass smut disease. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 2021, 34, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Yu, H.; Jia, Y.; Dong, Q.; Steinberg, C.; Alabouvette, C.; Edel-Hermann, V.; Kistler, H.C.; Ye, K.; Ma, L.-J.; et al. Chromosome-scale genome assembly of Fusarium oxysporum strain Fo47, a fungal endophyte and biocontrol agent. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 2020, 33, 1108–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenzie, S.K.; Walston, R.F.; Allen, J.L. Complete, high-quality genomes from long-read metagenomic sequencing of two wolf lichen thalli reveals enigmatic genome architecture. Genomics 2020, 112, 3150–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maphosa, M.N.; Steenkamp, E.T.; Kanzi, A.M.; van Wyk, S.; De Vos, L.; Santana, Q.C.; Duong, T.A.; Wingfield, B.D. Intra-species genomic variation in the pine pathogen Fusarium circinatum. Journal of Fungi 2022, 8, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swalarsk-Parry, B.S.; Steenkamp, E.T.; van Wyk, S.; Santana, Q.C.; van der Nest, M.A.; Hammerbacher, A.; Wingfield, B.D.; De Vos, L. Identification and characterization of a QTL for growth of Fusarium circinatum on pine-based medium. Journal of Fungi 2022, 8, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lofgren, L.A.; Stajich, J.E. Fungal biodiversity and conservation mycology in light of new technology, big data, and changing attitudes. Current Biology 2021, 31, R1312–R1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheffield, N.C.; LeRoy, N.J.; Khoroshevskyi, O. Challenges to sharing sample metadata in computational genomics. Frontiers in Genetics 2023, 14, 154198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duong, T.A.; De Beer, Z.W.; Wingfield, B.D.; Wingfield, M.J. Characterization of the mating-type genes in Leptographium procerum and Leptographium profanum. Fungal Biology 2013, 117, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koren, S.; Walenz, B.P.; Berlin, K.; Miller, J.R.; Bergman, N.H.; Phillipy, A.M. Canu: Scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Research 2017, 27, 722–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, R.S. Improved pairwise alignment of genomic DNA. Pennsylvania State University, Pennsylvania, USA, 2007.

- Kearse, M.; Moir, R.; Wilson, A.; Stones-Havas, S.; Cheung, M.; Sturrock, S.; Buxton, S.; Cooper, A.; Markowitz, S.; Duran, C.; et al. Geneious Basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics Applications Note 2012, 28, 1647–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R.; Subgroup, G.P.D.P. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, B.J.; Abeel, T.; Shea, T.; Priest, M.; Abouelliel, A.; Sakthikumar, S.; Cuomo, C.A.; Zeng, Q.; Wortman, J.; Young, S.K.; et al. Pilon: An integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, S.; Phillippy, A.; Delcher, A.L.; Smoot, M.; Shumway, M.; Antonescu, C.; Salzberg, S.L. Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biology 2004, 5, R12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Donnell, K.; Cigelnik, E.; Nirenberg, H.I. Molecular systematics and phylogeography of the Gibberella fujikuroi species complex. Mycologia 1998, 90, 465–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, R.M.; Seppey, M.; Simão, F.A.; Manni, M.; Ioannidis, P.; Klioutchnikov, G.; Kriventseva, E.V.; Zdobnov, E.M. BUSCO applications from quality assessments to gene prediction and phylogenomics. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2017, 35, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Wyk, S. Molecular characterization of the growth rate determining quantitative trait locus in Fusarium circinatum. University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, 2015.

- Wu, C.; Kim, Y.-S.; Smith, K.M.; Li, W.; Hood, H.M.; Staben, C.; Selker, E.U.; Sachs, M.S.; Farman, M.L. Characterization of chromosome ends in the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa. Genetics 2009, 181, 1129–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Wyk, S.; Harrison, C.H.; Wingfield, B.D.; De Vos, L.; van der Merwe, N.A.; Steenkamp, E.T. The RIPper, a web-based tool for genome-wide quantification of Repeat-Induced Point (RIP) mutations. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levan, A.; Fredga, K.; Sandberg, A.A. Nomenclature for centromeric position on chromosomes. Hereditas 1964, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantarel, B.L.; Korf, I.; Robb, S.M.C.; Parra, G.; Ross, E.; Moore, B.; Holt, C.; Alvarado, A.S.; Yandell, M. MAKER: An easy-to-use annotation pipeline designed for emerging model organism genomes. Genome Research 2008, 18, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanke, M.; Schöffmann, O.; Morgenstern, B.; Waack, S. Gene prediction in eukaryotes with a generalized hidden Markov model that uses hints from external sources. BMC Bioinformatics 2006, 7, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ter-Hovhannisyan, V.; Lomsadze, A.; Chernoff, Y.O.; Borodovsky, M. Gene prediction in novel fungal genomes using an ab initio algorithm with unsupervised training. Genome Research 2008, 18, 1979–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korf, I. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinformatics 2004, 5, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Götz, S.; García-Gómez, J.M.; Terol, J.; Williams, T.D.; Nagaraj, S.H.; Nueda, M.J.; Robles, M.; Talón, M.; Dopazo, J.; Conesa, A. High-throughput functional annotation and data mining with the Blast2GO suite. Nucleic Acids Research 2008, 36, 3420–3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Supek, F.; Bošnjak, M.; Škunca, N.; Šmuc, T. REVIGO summarizes and visualizes long lists of gene ontology terms. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flutre, T.; Dupart, E.; Feuillet, C.; Quesneville, H. Considering transposable element diversification in de novo annotation approaches. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quesneville, H.; Bergman, C.M.; Andrieu, O.; Autard, D.; Nouaud, D.; Ashburner, M.; Anxolabehere, D. Combined evidence annotation of transposable elements in genome sequences. PLoS Computational Biology 2005, 1, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vos, L.; Van der Nest, M.A.; Van der Merwe, N.A.; Myburg, A.A.; Wingfield, M.J.; Wingfield, B.D. Genetic analysis of growth, morphology and pathogenicity in the F1 progeny of an interspecific cross between Fusarium circinatum and Fusarium subglutinans. Fungal Biology 2011, 115, 902–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieber, N.; Zapatka, M.; Lasitschka, B.; Jones, D.; Northcott, P.; Hutter, B.; Jäger, N.; Kool, M.; Taylor, M.; Lichter, P.; et al. Coverage bias and sensitivity of variant calling for four whole-genome sequencing technologies. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wyk, S.; Wingfield, B.D.; De Vos, L.; van der Merwe, N.A.; Steenkamp, E.T. Genome-wide analysis of Repeat-Induced Point mutations in the Ascomycota. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 11, 3625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wyk, S.; Wingfield, B.D.; van der Merwe, N.A.; De Vos, L.; Maphosa, M.; Potgieter, L.; Steenkamp, E.T. Repeat-induced point mutations (RIP) drives the formation of distinct sub-genomic comparrtments in Fusarium circinatum. Preprints 2020, 2020120697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicker, T.; Sabot, F.; Hua-Van, A.; Bennetzen, J.L.; Capy, P.; Chalhoub, B.; Flavell, A.; Leroy, P.; Morgante, M.; Panaud, O.; et al. A unified classification system for eukaryotic transposable elements. Nature Reviews Genetics 2007, 8, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, T.R.; Storer, A.J.; Okamoto, D. Population structure of the pitch canker pathogen, Fusarium subglutinans f. sp. pini, in California. Mycological Research 1996, 100, 850–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, E.T.; Makhari, O.M.; Coutinho, T.A.; Wingfield, B.D.; Wingfield, M.J. Evidence for a new introduction of the pitch canker fungus Fusarium circinatum in South Africa. Plant Pathology 2014, 63, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aylward, J.; Steenkamp, E.T.; Dreyer, L.L.; Roets, F.; Wingfield, B.D.; Wingfield, M.J. Genome sequences of Knoxdaviesia capensis and K. protea (Fungi: Ascomycota) from Protea trees in South Africa. Standards in Genomic Sciences 2016, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mashandule, O.M. Population biology of Fusarium cirrcinatum Nirenberg et O’Donnell associated with South African Pinus radiata D. Don plantation trees. PhD, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, 2014.

- Steenkamp, E.T.; Coutinho, T.A.; Desjardins, A.E.; Wingfield, B.D.; Marasas, W.F.O.; Wingfield, M.J. Gibberella fujikuroi mating population E is associated with maize and teosinte. Molecular Plant Pathology 2001, 2, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desjardins, A.E.; Plattner, R.D.; Gordon, T.R. Gibberella fujikuroi mating population A and Fusarium subglutinans from teosinte species and maize from Mexico and Central America. Mycological Research 2000, 104, 865–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCain, A.H.; Koehler, C.S.; Tjosvold, S.A. Pitch canker threatens California pines. California Agriculture 1987, November-December, 22-23.

- Berbegal, M.; Pérez-Sierra, A.; Armengol, J.; Grünwald, N.J. Evidence for multiple introductions and clonality in Spanish populations of Fusarium circinatum. Phytopathology 2013, 103, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britz, H.; Coutinho, T.A.; Wingfield, B.D.; Marasas, W.F.O.; Wingfield, M.J. Diversity and differentiation in two populations of Gibberella circinata in South Africa. Plant Pathology 2005, 54, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, E.L.; Jaszczyszyn, Y.; Naquin, D.; Thermes, C. The third revolution in sequencing technology. Trends in Genetics 2018, 34, 666–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, K.R.; Cowley, M.J.; Davis, R.L. Next-generation sequencing and emerging technologies. Seminars in Thrombosis and Homestasis 2019, 45, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wingfield, B.D.; Barnes, I.; De Beer, Z.W.; De Vos, L.; Duong, T.A.; Kanzi, A.M.; Naidoo, K.; Nguyen, H.D.T.; Santana, Q.C.; Sayari, M.; et al. Draft genome sequences of Ceratocystis eucalypticola, Chrysoporthe cubensis, C. deuterocubensis, Davidsoniella virescens, Fusarium temperatum, Graphilbum fragrans, Penicillium nordicum, and Thielaviopsis musarum. IMA Fungus 2015, 6, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wingfield, B.D.; Berger, D.K.; Steenkamp, E.T.; Lim, H.-J.; Duong, T.A.; Bluhm, B.H.; de Beer, Z.W.; De Vos, L.; Fourie, G.; Naidoo, K.; et al. Draft genome of Cercospora zeina, Fusarium pininemorale, Hawksworthiomyces lignivorus, Huntiella decipiens and Ophiostoma ips. IMA Fungus 2017, 8, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wingfield, B.D.; Bills, G.F.; Dong, Y.; Huang, W.; Nel, W.J.; Swalarsk-Parry, B.S.; Vaghefi, N.; Wilken, P.M.; An, Z.; de Beer, Z.W. ; et al. Draft genome sequence of Annulohypoxylon stygium, Aspergillus mulundensis, Berkeleyomyces basicola (syn. Thielaviopsis basicola), Ceratocystis smalleyi, two Cercospora beticola strains, Coleophoma cylindrospora, Fusarium fracticaudum, Phialophora cf. hyalina, and Morchella septimelata. IMA Fungus 2018, 9, 199–223. [CrossRef]

- Coghlan, A.; Eichler, E.E.; Oliver, S.G.; Paterson, A.H.; Stein, L. Chromosome evolution in eukaryotes: A multi-kingdom perspective. Trends in Genetics 2005, 21, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guin, K.; Sreekumar, L.; Sanyal, K. Implications of the Evolutionary Trajectory of Centromeres in the Fungal Kingdom. Annual Review of Microbiology 2020, 74, 835–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Yadav, V.; Billmyre, R.B.; Cuomo, C.A.; Nowrousian, M.; Wang, L.; Souciet, J.-L.; Boekhout, T.; Porcel, B.; Wincker, P.; et al. Fungal genome and mating system transitions facilitated by chromosomal translocations involving intercentromeric recombination. PLos Biology 2017, 15, e2002527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, V.; Sun, S.; Coelho, M.A.; Heitmans, J. Centromere scission drives chromosome shuffling and reproductive isolation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117, 7917–7928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, S.; Sharda, S.; Oddi, V.; Nandineni, M.R. The landscape of repetitive elements in the refined genome of chilli anthracnose fungus Collectotrichum truncatum. Frontiers in Microbiology 2018, 9, 2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stukenbrock, E.H.; Croll, D. The evolving fungal genome. Fungal Biology Reviews 2014, 28, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depotter, J.R.L. , Ökmen, B., Ebert, M.K., Beckers, J., Kruse, J., Thines, M. and Doehlemann, G. High nucleotide substitution rates associated with retrotransposon proliferation drive dynamic secretome evolution in smut pathogens. Microbiology Spectrum, 2022, 10, e00349–e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malewski, T.; Matić, S.; Okorski, A.; Borowik, P.; Oszako, T. Annotation of the 12th chromosome of the forest pathogen Fusarium circinatum. Agronomy 2023, 13, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slinski, S.L. , Kirkpatrick, S.C. and Gordon, T.R. Inheritance of virulence in Fusarium circinatum, the cause of pitch canker in pines. Plant Pathology 2016, 65, 1292–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Nest, M.A. , Beirn, L.A., Crouch, J.A., Demers, J.E., De Beer, Z.W., De Vos, L., Gordon, T.R., Moncalvo, J.M., Naidoo, K., Sanchez-Ramirez, S. and Roodt, D. Draft genomes of Amanita jacksonii, Ceratocystis albifundus, Fusarium circinatum, Huntiella omanensis, Leptographium procerum, Rutstroemia sydowiana, and Sclerotinia echinophila. IMA fungus, 2014, 5, 472–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumero, M.V.; Villani, A.; Susca, A.; Haidukowski, M.; Cimmarusti, M.T.; Toomajian, C.; Leslie, J.F.; Chulze, S.N.; Moretti, A. Fumonisin and beauvericin chemotypes and genotypes of the sister species Fusarium subglutinans and Fusarium temperatum. Appled and Environmental Microbiology 2020, 86, e00133–e00120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Genome Statistic | FSP34 | KS17 | |||

| Previous 1 | Current | Previous 2 | Current | ||

| Genome size (bp) | 43 932 912 | 45 020 843 | 46 325 048 | 44 380 849 | |

| G+C content (%) | 47.41 | 47.00 | 44.69 | 47.26 | |

| Number of open reading frames | 14 923 3 | 15 490 | 16 502 4 | 15 113 | |

| Gene density (orfs/Mb) | 339.68 | 344.06 | 356.22 | 340.53 | |

| Number of scaffolds | 585 | 49 | 6 033 | 96 | |

| N50 (bp) | 363 633 | 4 313 168 | 95 695 | 4 401 926 | |

| Average scaffold size (bp) | 75 085 | 1 667 439 | 7 679 | 1 431 640 | |

| Unmapped scaffolds (total % of genome) | 418 (3.03%) | 15 (0.60%) | - 5 | 19 (0.78%) | |

| Repeat content 6 | 2.81% | 8.75% | - | 8.60% | |

| Genome completeness 7 | 94.8% | 97.3% | 76.2% | 98.1% | |

| Pseudomolecule | FSP34 1 | KS17current | |

| Previous | Current | ||

| 1 | 6 190 704 (14) | 6 407 689 (2) | 6 397 914 (8) |

| 2 | 4 773 114 (22) | 5 066 197 (3) | 4 709 326 (5) |

| 3 | 4 756 822 (18) | 5 081 888 (3) | 5 148 568 (3) |

| 4 | 4 140 424 (12) | 4 313 168 (2) | 4 401 926 (5) |

| 5 | 4 399 406 (10) | 4 432 553 (2) | 4 304 443 (7) |

| 6 | 4 053 349 (21) | 4 301 895 (3) | 4 219 930 (9) |

| 7 | 3 472 423 (19) | 3 541 054 (5) | 3 312 103 (8) |

| 8 | 3 024 507 (17) | 3 172 915 (5) | 3 066 990 (9) |

| 9 | 2 773 158 (8) | 2 981 544 (1) | 2 828 005 (4) |

| 10 | 2 371 510 (16) | 2 698 820 (3) | 2 483 521 (7) |

| 11 | 2 122 486 (11) | 2 228 420 (3) | 2 291 537 (5) |

| 12 | 525 791 (6) | 525 065 (1) | 870 680 (3) |

| Content Estimates | FSP34 Pseudomolecule 12 1 | KS17 Pseudomolecule 12 2 | |||

| Whole Molecule | Distal | Middle | Proximal | ||

| G+C content (%) | 46.36 | 41.73 | 31.88 | 45.18 | 41.48 |

| Gene density (orfs/Mb) | 325.67 | 294.01 | 123.53 | 349.52 | 300.00 |

| Repeats (%) | 6.92 | 26.63 | 59.67 | 12.67 | 33.48 |

| Data/Properties | FSP34 | KS17 | References |

| Strain origin | |||

| Collection date | Unknown date between March 1993 and April 1995 | October 2005 | [65,66,67,68] |

| Collector | TR Gordon | OM Mashandula, ET Steenkamp | [65,68] 1 |

| Host plant | Pinus radiata | Pinus radiata | [65] |

| Host tissue | Tissue from the leading edge of a canker on the branch of a mature tree | Diseased root tissue of a nursery seedling | [65] |

| Geographic location | Monterey, California (USA) | Karatara, Western Cape (South Africa) | [65,68] |

| Location description | Exact location is unknown, but collected in a region where mature trees of native Pinus species displayed symptoms of pitch canker | Commercial seedling nursery; was collected during an outbreak of F. circinatum-associated root disease | [65] |

| Reproductive biology | |||

| Mating type | MAT1-1 | MAT1-2 | [68,69] |

| Fertility | Male fertile; mostly female sterile; also capable of mating with sexually compatible strains of Fusarium temperatum to produce fertile hybrid progeny | Male fertile; displays some level of fertility as a female | [24,69,70](unpublished) |

| Source population dynamics | Forms part of a population with limited genetic diversity that propagates asexually | Forms part of a moderately diverse population that propagates mainly asexually | [66,71,72,73] |

| Growth in culture | Grows at 5-30°C, but not at 35°C; grows faster than KS17 at 15-30°C | Grows at 5-30°C, but not at 35°C; grows slower than FSP34 at 15-30°C | [60], this study |

| Pathogenicity | Capable of inducing lesions when inoculated onto the apices of the main stems of P. patula seedlings; more virulent than KS17 | Capable of inducing lesions when inoculated onto the apices of the main stems of P. patula seedlings; less virulent than FSP34 | This study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).