1. Introduction

The rapid growth of wearable sensing technologies has transformed the landscape of health monitoring and personal wellness assessment [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. With the increasing availability of compact, low-power, and user-friendly devices, continuous recording of physiological and behavioral data in daily life has become not only feasible but increasingly common. This trend reflects a broader societal shift toward preventive health care, personalized medicine, and data-driven wellness management. Among the many physiological signals that can be captured through wearable sensors—such as heart activity, respiratory rhythm, or skin conductance—one of the most informative and versatile indicators is body acceleration. Acceleration signals obtained from 3-axis sensors provide direct, fine-grained information about movement patterns, posture, and physical activity levels [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Unlike self-reported measures of activity, accelerometers deliver objective, continuous data that can be analyzed over hours, days, or even weeks. These data streams allow for the characterization of both transient movements, such as walking or climbing stairs, and long-term behavioral trends, such as sedentary patterns or sleep quality. In recent years, the importance of accelerometer-based monitoring has been increasingly recognized, not only in general activity tracking but also in advanced health research applications.

For example, in geriatric populations, acceleration data have been widely used to develop predictive models for fall risk. Falls represent a major source of morbidity and loss of independence in older adults, and early identification of individuals at risk is a crucial goal for preventive care [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Similarly, accelerometer-derived activity metrics have been investigated as predictors of frailty, a condition characterized by decreased physiological reserves and heightened vulnerability to stressors [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. By quantifying subtle changes in movement dynamics, wearable accelerometers can reveal early indicators of frailty before overt clinical symptoms emerge. Thus, accelerometry has become a cornerstone in research targeting healthy aging, fall prevention, and long-term functional maintenance. Beyond elderly care, accelerometers have been integrated into a wide range of health monitoring systems aimed at younger populations and the general public. Commercial activity trackers and smartwatches, now ubiquitous in daily life, rely heavily on acceleration signals to quantify steps, energy expenditure, sleep cycles, and exercise intensity [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. This democratization of health data has empowered individuals to monitor their own behaviors, set personalized goals, and engage more actively in health management. In parallel, researchers have leveraged these data to study the links between physical activity and a variety of outcomes, including metabolic health, mental well-being, and cardiovascular fitness.

While accelerometer data are highly informative on their own, their utility is significantly enhanced when combined with other physiological signals. Among these, heart rate (HR) and heart rate variability (HRV) occupy a particularly important role. Both metrics reflect the dynamic interplay between the autonomic nervous system and cardiovascular regulation, and they are sensitive to physical exertion, emotional states, and environmental stressors. By integrating HR signals with accelerometer-derived activity measures, it becomes possible to disentangle the physiological drivers of heart rate dynamics in daily life. For instance, HR elevation may be attributed to physical exertion when accompanied by acceleration, or to psychological stress when occurring in the absence of movement.

Recent technological advances have enabled the development of wearable devices that seamlessly integrate both accelerometry and cardiac monitoring. These systems provide a unique opportunity to analyze transient HR responses to spontaneous physical activity under free-living conditions. Unlike controlled laboratory experiments, free-living monitoring captures the richness and variability of real-world behavior, offering more ecologically valid insights into cardiovascular regulation. Furthermore, the continuous nature of the data allows for the detection of subtle, short-lived responses that may be overlooked in snapshot assessments. The combination of accelerometer and heart activity data has been particularly powerful for developing computational models of cardiovascular responses. Among these approaches, the multivariate autoregressive (MVAR) model has emerged as a robust method for characterizing dynamic interactions between time-series signals. By incorporating both accelerometer-derived activity levels and RR interval sequences from heart signals, the MVAR framework can quantify the extent to which physical activity explains transient changes in HR. Such modeling not only provides mechanistic insights into autonomic regulation but also offers practical tools for personalized health monitoring. The relevance of this integration extends beyond academic research. In everyday health applications, reliable quantification of HR responses to activity can support diverse use cases, including fitness optimization, stress management, and early detection of abnormal cardiovascular reactions. For athletes and recreational exercisers, monitoring the alignment between activity levels and HR responses can guide training intensity and recovery strategies. For individuals managing chronic conditions or seeking to maintain general wellness, the same metrics can serve as indicators of resilience, adaptation, and lifestyle balance. At the population level, wearable sensing data also hold potential for public health applications. Large-scale analyses of accelerometer and HR data can provide valuable insights into activity patterns across different demographics, socioeconomic groups, and geographic regions. These insights can inform policy decisions, community-level interventions, and health promotion strategies. Importantly, such data collection can be achieved passively, without requiring disruptive laboratory visits or self-report surveys, thereby reducing barriers to participation and enhancing ecological validity.

Despite these advances, challenges remain in extracting reliable and interpretable metrics from wearable sensor data collected under free-living conditions. Movement artifacts, signal noise, and individual variability can complicate the analysis. Furthermore, while correlations between physical activity and HR are well established, quantifying the precise contribution of movement to transient HR dynamics remains a methodological hurdle. Addressing these challenges requires robust computational models capable of capturing complex, multivariate relationships in real-world data.

In this study, we aim to address these gaps by applying an MVAR modeling approach to combined accelerometer and cardiac data recorded under free-living conditions. Specifically, we investigate whether transient HR responses to spontaneous activity can be accurately predicted using this framework. By doing so, we extend the utility of wearable sensors beyond simple descriptive metrics, advancing toward predictive, mechanistic insights into daily cardiovascular regulation. The results of this study contribute to the growing body of literature demonstrating the potential of wearable sensing technologies as powerful tools for health and wellness monitoring.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Experimental Protocol

Twelve healthy adult males (age: 41 ± 9 years) participated in this study. All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nagoya City University Hospital (Approval number: 60-18-2011, March 22, 2019). Cardiac activity was recorded using an ultra-compact electrocardiograph equipped with a built-in three-axis accelerometer (Cardy 303 pico, Suzuken Co., Ltd., Nagoya, Japan). The device was attached to the anterior chest, and continuous 24-hour recordings were obtained under free-living conditions. Each subject underwent two measurement sessions separated by a one-week interval.

Two types of transient body activities were analyzed:

- A)

Awake condition: Approximately 40 short, spontaneous episodes of physical activity (≤ 60 s each) were identified during wakefulness.

- B)

Sleep condition: Approximately 10 episodes of movement arousals (≤ 60 s each) were extracted during sleep.

2.2. Signal Acquisition and Preprocessing

The electrocardiograph provided both RR interval time-series (X) and tri-axial acceleration signals. The accelerometer axes were defined as follows:

X-axis: right–left direction

Y-axis: vertical (upward) direction

Z-axis: forward–backward direction

Because posture changes affect axis orientation, positional adjustments were applied to normalize activity representation. For example, supine posture corresponded to Z = –1.0 g, prone posture to Z = +1.0 g, and lateral positions to ±1.0 g depending on hand orientation. Here, 1.0 g was defined as 9.8 m/s².

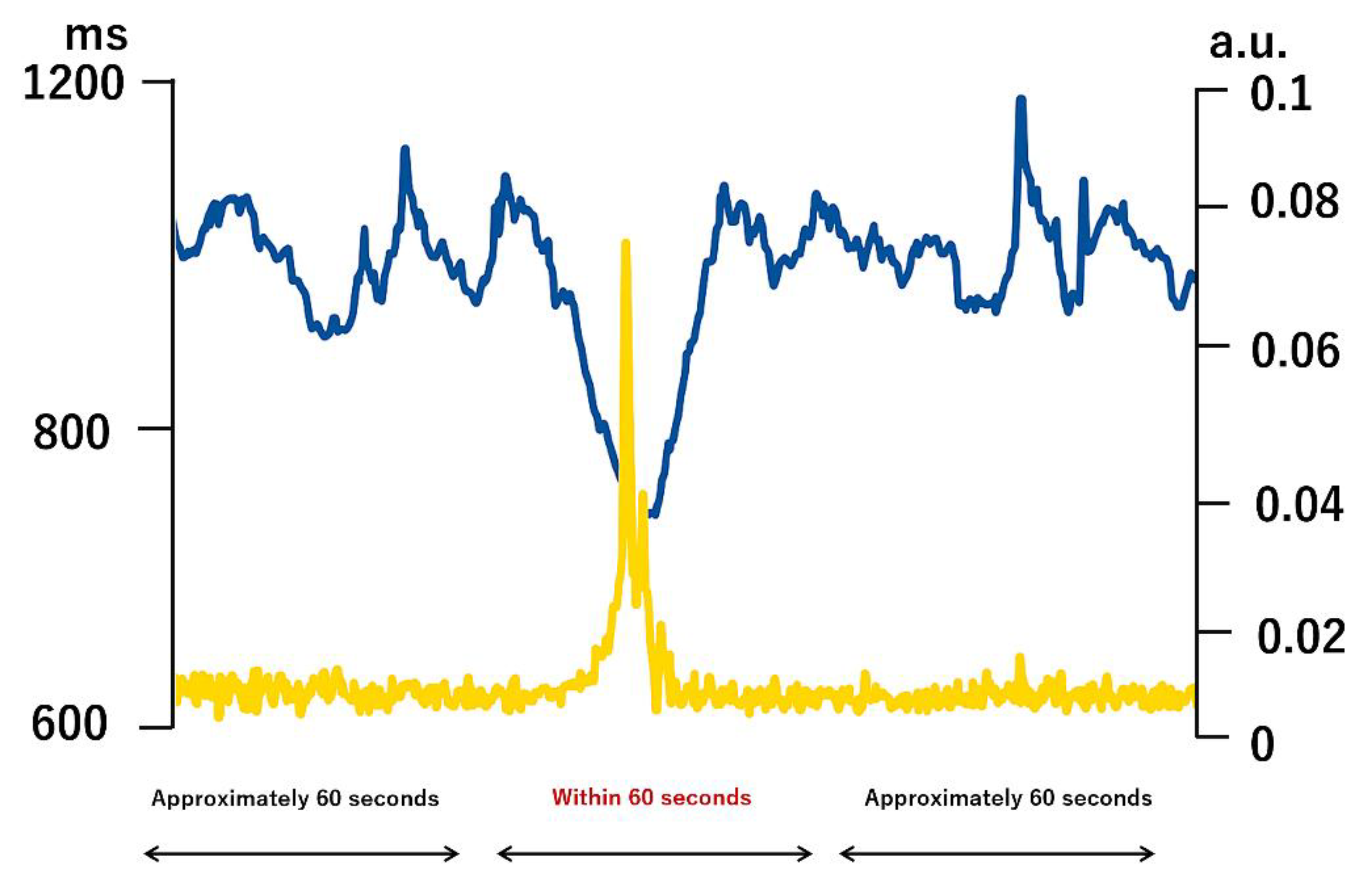

Body activity signals were processed using a 0.1–1.2 Hz band-pass filter to remove DC drift and high-frequency noise. The square root of the sum of squared acceleration components was then computed and converted into a univariate time series representing activity level (Y). Posture predicts posture during 24 hours of free movement based on 3-axis acceleration and displays values between 0.1 and 1.0. 0.1 indicates supine position, 0.2 indicates prone position, 0.4 indicates lateral position (right hand up), 0.6 indicates lateral position (right hand down), and 1.0 indicates standing or sitting position (

Figure 1).

Figure 1.

An example of heart rate RR interval and activity.

Figure 1.

An example of heart rate RR interval and activity.

An example of extracted RR interval time series and physical activity time series for transient physical activity of less than 60 seconds during wakefulness and sleep. The blue line shows heart rate RR interval, and the yellow line shows biological acceleration. The values of the 3-axis accelerometer are scaled to a range of 0 to 0.1. The original unit of acceleration measured by the accelerometer used in the experiment is g, but since this sensor can measure within a range of ±1 g, we defined this as a movement intensity score (an index of activity level) in the range of 0 to 0.1. The acceleration signal was band-pass filtered between 0.1 and 1.2 Hz to remove DC and high-frequency components. The square root of the sum of squares was calculated to convert it into a univariate time series of physical activity. A model equation was developed using X as the R-R interval and Y as the physical activity level, and the response of X to changes in Y was calculated.

2.3. Time-Series Extraction for AR Modeling

For each transient activity episode, RR interval time-series (X) and physical activity time-series (Y) were extracted within 60-second windows. These paired time-series were used to parameterize a multivariate autoregressive (MVAR) model, allowing the estimation of heart rate responses to physical activity.

2.4. Multivariate Autoregressive (MVAR) Model

The transient HR response was modeled as:

X(t): RR interval at time t

Y(t): body activity level at time t

p: model order (determined using the Final Prediction Error criterion)

ak, bk, ck, dk: linear prediction coefficients

Z(t): residual term

This formulation models the dynamics of RR interval fluctuations as determined by both past RR intervals and past body activity levels.

2.5. Evaluation of Model Performance

Multivariate Autoregressive Model (MVAR) was applied to each episode to predict HR responses to transient physical activity. MVAR model is a statistical model used to analyze how multiple time series data influence each other and change over time. It is an extension of the basic autoregressive (AR) model to handle multiple variables. AR model assumes that the future value of a variable can be explained by its own past values. In contrast, the MVAR model handles multiple different time series data simultaneously. Therefore, MVAR models assume that the current value of each variable is determined not only by its own past values but also by the past values of all other variables, and express this relationship in mathematical terms for analysis and prediction. The MVAR model considers a case where there are two time series data, Xt and Yt. It assumes that the current value of Xt is influenced not only by Xt-1 (the value of X one period ago) but also by Yt-1 (the value of Y one period ago). Similarly, the current value of Yt is considered to be influenced not only by Yt-1 but also by Xt-1. These influences are expressed as linear relationships, and by estimating the coefficients (weights) indicating the degree of influence between each variable, the specific relationships are clarified (linear combination).

Predicted responses were compared with actual responses obtained from ensemble averages of measured RR intervals. The degree of agreement between predicted and measured responses was quantified using correlation analysis.

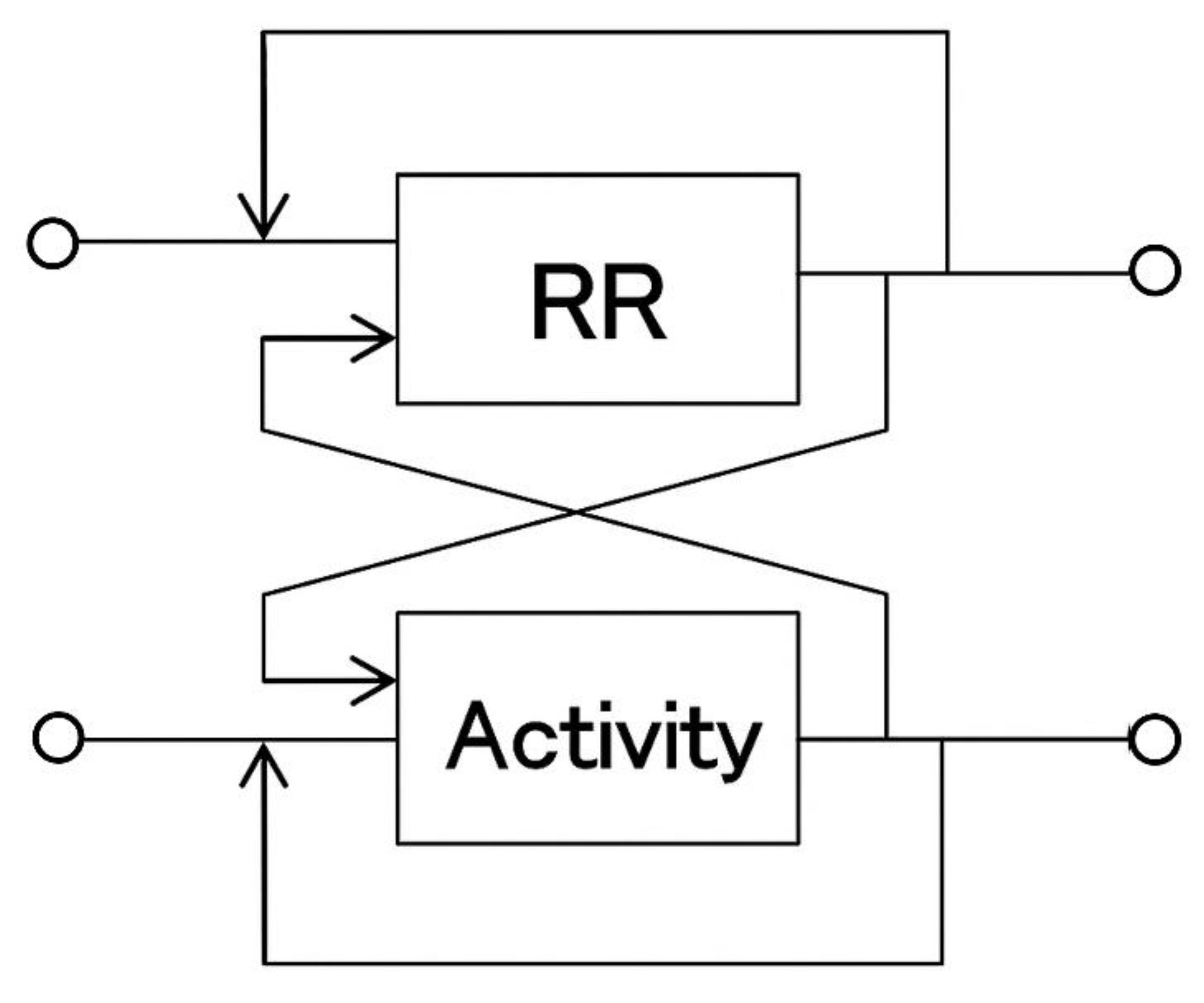

Figure 2.

System Identification Using a Multidimensional Autoregressive Model.

Figure 2.

System Identification Using a Multidimensional Autoregressive Model.

Heart rate responses to transient physical activity were predicted using a multidimensional autoregressive model and compared with the actual heart rate responses obtained by averaging. The model demonstrates that the fluctuations in time series X are determined by the past fluctuations of X itself and other related time series.

3. Results

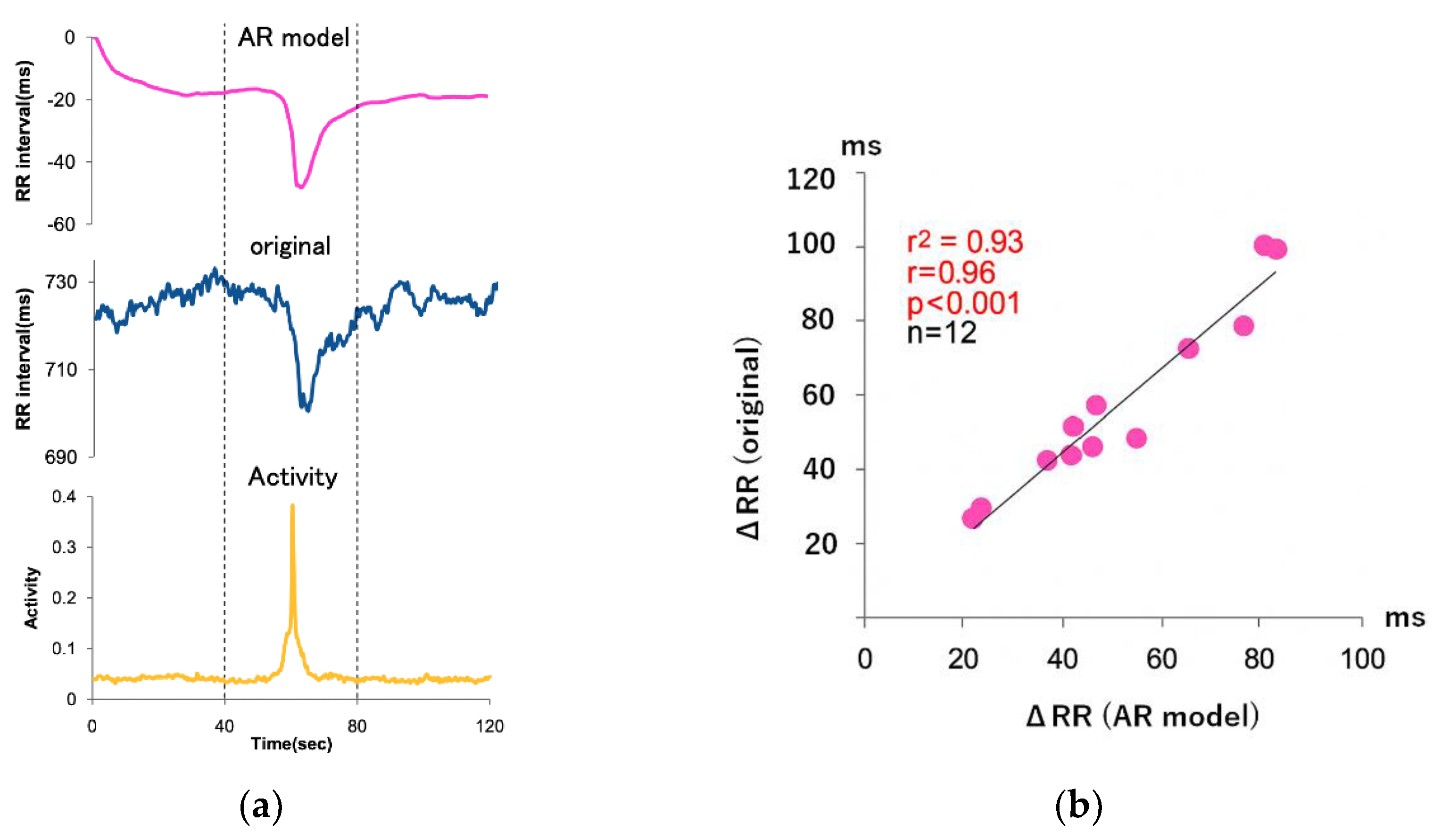

Evaluated the accuracy of heart rate (HR) responses to transient physical activity using a multivariate autoregressive (MVAR) model with RR interval and accelerometer-derived body activity signals under free-living conditions; the results demonstrated a strong correlation between predicted and measured HR responses during wakefulness (

Figure 1; r² = 0.93, r = 0.96, p < 0.001, n = 12), indicating that approximately 93% of the transient HR response could be explained by the MVAR model. During walking, fluctuations in the Z-axis signal reflected dynamic posture changes. In contrast, during sleep, HR responses associated with arousal could not be fully predicted by body activity signals alone. Posture estimation derived from tri-axial accelerometry provided additional insights into daily physical states, with characteristic values corresponding to supine (0.1), prone (0.2), and lateral (0.4, right arm up) positions.

Figure 3.

Accuracy assessment of heart rate responses during acute physical activity. Figure (a) shows the heart rate response during wakefulness, and Figure (b) shows the correlation between the decrease in heart rate response calculated from AR and the actual decrease in heart rate.

Figure 3.

Accuracy assessment of heart rate responses during acute physical activity. Figure (a) shows the heart rate response during wakefulness, and Figure (b) shows the correlation between the decrease in heart rate response calculated from AR and the actual decrease in heart rate.

4. Discussion

The present study investigated the feasibility of using a multivariate autoregressive (MVAR) modeling approach to predict heart rate (HR) responses to transient physical activity under free-living conditions by combining RR interval data and accelerometer-derived activity signals. Our results demonstrated that during wakefulness, approximately 93% of the transient HR response could be explained by the MVAR model, indicating a high degree of predictive accuracy. This finding underscores the potential of integrated accelerometer–ECG monitoring for characterizing cardiovascular dynamics in real-world settings.

Heart rate responses to transient activity during wakefulness and sleep; the strong correlation observed between modeled and actual HR responses in wakefulness suggests that HR dynamics during transient activity are largely driven by mechanical or metabolic demands directly captured by accelerometry. For instance, walking induced characteristic fluctuations in the Z-axis acceleration signal, which were well-aligned with increases in HR. This observation is consistent with previous research demonstrating that locomotor activity measured by tri-axial inertial sensors can reliably capture dynamic physical states and related physiological responses in free-living contexts [

31]. In contrast, HR responses during sleep could not be fully explained by accelerometer signals alone. Episodes of movement arousal were accompanied by HR accelerations that exceeded predictions based solely on body activity, suggesting contributions from autonomic arousal mechanisms. Similar phenomena have been described in the context of sleep physiology, where sympathetic activation during arousals can elicit abrupt cardiovascular changes independent of gross body movement [

32]. This discrepancy highlights an important limitation of purely activity-driven models in nocturnal contexts, where neural regulatory inputs may dominate HR variability. Autoregressive modeling of HR responses; the use of an autoregressive framework provided several methodological advantages. By explicitly modeling the dependencies of HR time series on both its own past values and on activity-derived inputs, the MVAR approach enabled robust system identification even under noisy real-world conditions. This is in line with prior work showing that autoregressive modeling is effective for spectral and time-domain analysis of HR variability [

33,

34]. However, unlike traditional autoregressive analyses of stationary HRV segments, our study emphasized short-term, transient dynamics. This focus aligns with recent developments in time-varying or multivariate autoregressive modeling of psychophysiological signals, which have demonstrated utility in quantifying causal interactions between autonomic branches [

35]. By extending this principle to activity–HR interactions, the current study contributes to a broader methodological framework for modeling physiological responses to environmental perturbations.

Comparison with related studies; our findings differ from earlier work by Nazeran et al. (2005) [

36], who applied nonlinear dynamic methods to evaluate HR variability responses during structured exercise in laboratory conditions. Whereas their study emphasized spectral and nonlinear markers of autonomic regulation, our work addressed the transient, time-domain relationship between spontaneous body movements and HR under free-living conditions. This distinction is important, as ecological monitoring introduces variability not captured in controlled environments. The present study also contrasts with research on prosthetic gait monitoring using autoregressive neural network models [

37]. While both studies share a focus on autoregressive system identification, our emphasis was on cardiovascular responses rather than biomechanical prediction. Nevertheless, the methodological parallels suggest that hybrid machine learning and autoregressive approaches may hold promise for improving model accuracy in future work. Studies that have examined HRV in relation to daytime activity levels [

32] or derived HRV from wearable photoplethysmography [

38] further highlight the increasing trend of integrating multimodal signals for health monitoring. The present findings support this trajectory, showing that accelerometer-enhanced ECG systems enable meaningful quantification of HR responses to everyday activity, particularly in distinguishing inter-individual response profiles.

Implications for health monitoring and exercise prescription; the ability to accurately capture HR responses to transient physical activity in daily life has important implications for personalized health monitoring. In particular, quantifying the magnitude and kinetics of HR response may provide insight into autonomic regulation and cardiovascular fitness. Our results suggest that accelerometer-integrated monitoring systems could aid in tailoring exercise prescriptions or evaluating the efficacy of rehabilitation programs, extending applications beyond traditional HR monitoring. This potential is especially relevant for populations requiring individualized activity guidance, such as older adults, where accelerometry is already widely employed for frailty and fall-risk prediction. Furthermore, the integration of posture estimation from tri-axial accelerometry adds contextual richness to HR monitoring. Our study showed that characteristic values derived from accelerometer signals (e.g., 0.1 for supine, 0.2 for prone, 0.4 for lateral positions) could classify postural states under free-living conditions. Such information may be valuable in interpreting cardiovascular responses in relation to body position, particularly in sleep studies or in conditions where posture-related hemodynamic shifts are clinically relevant.

Study limitations and future directions; several limitations warrant consideration. First, the study sample consisted of a relatively small cohort of 12 healthy adult males. This limits the generalizability of the findings, particularly to female or clinical populations with altered autonomic function. Second, although the MVAR model achieved high predictive accuracy during wakefulness, performance during sleep was less robust. As noted, this may reflect unmodeled autonomic contributions; future work should consider incorporating additional physiological signals such as electrodermal activity, respiration, or EEG to better capture arousal-related responses. Third, posture estimation based on accelerometer thresholds, while useful, remains an indirect proxy and may be affected by device placement or calibration variability. More advanced orientation estimation techniques, such as those using inertial measurement units and nonlinear filters, could improve accuracy [

37]. Fourth, the analysis focused on relatively short (≤60 s) transient activity windows; longer-term adaptation processes such as recovery dynamics were not assessed.

Finally, our approach was limited to linear autoregressive modeling. Although effective, nonlinear interactions between autonomic inputs and HR responses may not be fully captured. Nonlinear autoregressive models with exogenous inputs (NARX) or hybrid machine learning approaches may enhance predictive capacity, as suggested in prior biomechanics and HRV research.

In summary, the present findings extend the literature on HR variability and autoregressive modeling by demonstrating that transient HR responses to everyday physical activity can be reliably predicted under free-living conditions, particularly during wakefulness. Compared to previous controlled or laboratory-based studies, our approach emphasizes ecological validity and integrated multimodal monitoring. Future studies should build on this foundation by expanding participant diversity, incorporating additional physiological signals, and exploring nonlinear or hybrid modeling strategies.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated whether transient heart rate (HR) responses to physical activity can be reliably characterized using combined heart rhythm and body movement signals. While activity data are often applied for distinguishing sleep and wake states, relatively few studies have examined how heart rate dynamics directly respond to brief episodes of activity in daily life. Our results showed that, during wakefulness, up to 93% of HR responses to transient activity could be predicted using a multivariate autoregressive (MVAR) model that incorporated body acceleration signals together with heart rhythm measures. This demonstrates the potential of multimodal physiological monitoring for capturing cardiovascular adjustments during everyday behaviors. By contrast, during sleep, HR responses to arousal could not be explained by physical activity alone, suggesting an additional contribution from autonomic regulation. Simultaneous monitoring of movement and heart rate dynamics therefore provides valuable insights into individual variability in cardiovascular responsiveness under free-living conditions. From a healthcare perspective, such approaches may support the personalization of exercise recommendations, early detection of abnormal responses, and remote monitoring of treatment effectiveness.

In conclusion, integrated multimodal monitoring holds promise as a practical tool for continuous assessment of cardiovascular function in everyday healthcare.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.Y. and Y.Y.; methodology, Y.Y.; software, Y.Y.; validation, E.Y. and Y.Y.; formal analysis, E.Y.; investigation, E.Y.; resources, Y.Y.; data curation, Y.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, E.Y.; writing—review and editing, E.Y. and Y.Y.; visualization, Y.Y.; supervision, E.Y.; project administration, E.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study participants for their cooperation and acknowledge the technical support provided by colleagues during data collection and analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- de Bell, S.; Zhelev, Z.; Shaw, N.; Bethel, A.; Anderson, R.; Thompson Coon, J. Remote monitoring for long-term physical health conditions: an evidence and gap map. Health Soc Care Deliv Res. 2023, 11, 1–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Chai, K. Wearable Sensing Systems for Monitoring Mental Health. Sensors (Basel) 2022, 22, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, J.; Edbrooke-Childs, J. Monitoring and Measurement in Child and Adolescent Mental Health: It’s about More than Just Symptoms. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, B.; Cahalin, L.; Buman, M.; Ross, R. The current state of physical activity assessment tools. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 57, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, P.; Kirkham, R.; McNaney, R. Opportunities for Smartphone Sensing in E-Health Research: A Narrative Review. Sensors (Basel) 2022, 22, 3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P. Smartphone Applications for Patients’ Health and Fitness. Am. J. Med. 2016, 129, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keadle, S.K.; Conroy, D.E.; Buman, M.P.; Dunstan, D.W.; Matthews, C.E. Targeting Reductions in Sitting Time to Increase Physical Activity and Improve Health. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2017, 49(8), 1572–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toth, E.E.; Ihász, F.; Ruíz-Barquín, R.; Szabo, A. Physical Activity and Psychological Resilience in Older Adults: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2023, 32(2), 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakala, S.; Rintala, A.; Immonen, J.; Karvanen, J.; Heinonen, A.; Sjögren, T. Effectiveness of Technology-Based Distance Interventions Promoting Physical Activity: Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. J. Rehabil. Med. 2017, 49(2), 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaseva, K.; Dobewall, H.; Yang, X.; Pulkki-Råback, L.; Lipsanen, J.; Hintsa, T.; Hintsanen, M.; Puttonen, S.; Hirvensalo, M.; Elovainio, M.; Raitakari, O.; Tammelin, T. Physical Activity, Sleep, and Symptoms of Depression in Adults—Testing for Mediation. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51(6), 1162–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charansonney, O.L. Physical Activity and Aging: A Life-Long Story. Discov. Med. 2011, 12(64), 177–185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jewell, V.D.; Capistran, K.; Flecky, K.; Qi, Y.; Fellman, S. Prediction of Falls in Acute Care Using The Morse Fall Risk Scale. Occup. Ther. Health Care 2020, 34(4), 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakin, C.J.; Bolton, D.A.E. Forecast or Fall: Prediction’s Importance to Postural Control. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.K.; Skubic, M.; Despins, L.A.; Popescu, M.; Keller, J.; Rantz, M.; Abbott, C.; Enayati, M.; Shalini, S.; Miller, S. Explainable Fall Risk Prediction in Older Adults Using Gait and Geriatric Assessments. Front. Digit. Health 2022, 4, 869812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck Jepsen, D.; Robinson, K.; Ogliari, G.; Montero-Odasso, M.; Kamkar, N.; Ryg, J.; Freiberger, E.; Masud, T. Predicting Falls in Older Adults: An Umbrella Review of Instruments Assessing Gait, Balance, and Functional Mobility. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22(1), 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehfeld, S.; Schulte-Althoff, M.; Schreiber, F.; Fürstenau, D.; Näher, A.F.; Hauss, A.; Köhler, C.; Balzer, F. The Prediction of Fall Circumstances Among Patients in Clinical Care—A Retrospective Observational Study. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2022, 294, 575–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennone, J.; Aguero, N.F.; Martini, D.M.; Mochizuki, L.; do Passo Suaide, A.A. Fall Prediction in a Quiet Standing Balance Test via Machine Learning: Is It Possible? PLoS One 2024, 19(4), e0296355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Rockwood, K. Frailty in Older Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391(6), 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proietti, M.; Cesari, M. Frailty: What Is It? Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1216, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dent, E.; Martin, F.C.; Bergman, H.; Woo, J.; Romero-Ortuno, R.; Walston, J.D. Management of Frailty: Opportunities, Challenges, and Future Directions. Lancet 2019, 394(10206), 1376–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhu, J.; Hu, X.; Liao, R. Healthy Aging, Early Screening, and Interventions for Frailty in the Elderly. Biosci. Trends 2023, 17(4), 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesari, M.; Calvani, R.; Marzetti, E. Frailty in Older Persons. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2017, 33(3), 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolle, A.T.; Lewis, K.B.; Lalonde, M.; Backman, C. Reversing Frailty in Older Adults: A Scoping Review. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23(1), 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Valencia, M.; Izquierdo, M.; Cesari, M.; Casas-Herrero, Á.; Inzitari, M.; Martínez-Velilla, N. The Relationship Between Frailty and Polypharmacy in Older People: A Systematic Review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 84(7), 1432–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Abbod, M.; Shieh, J.S. Pain and Stress Detection Using Wearable Sensors and Devices—A Review. Sensors 2021, 21(4), 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Badea, M.; Tiwari, S.; Marty, J.L. Wearable Biosensors: An Alternative and Practical Approach in Healthcare and Disease Monitoring. Molecules 2021, 26(3), 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Shahabi, F.; Xia, S.; Deng, Y.; Alshurafa, N. Deep Learning in Human Activity Recognition with Wearable Sensors: A Review on Advances. Sensors 2022, 22(4), 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argañarás, J.G.; Wong, Y.T.; Begg, R.; Karmakar, N.C. State-of-the-Art Wearable Sensors and Possibilities for Radar in Fall Prevention. Sensors 2021, 21(20), 6836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, R.; Mishra, P.; Kumar, S. Advancements in optical fiber-based wearable sensors for smart health monitoring. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2024, 254, 116232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, M.B.; Rajagopal, S.; Prieto-Simón, B.; Pogue, B.W. Recent advances in smart wearable sensors for continuous human health monitoring. Talanta 2024, 272, 125817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahabpoor, E.; Pavic, A.; Brownjohn, J.M.W.; Billings, S.A.; Guo, L.Z.; Bocian, M. Real-Life Measurement of Tri-Axial Walking Ground Reaction Forces Using Optimal Network of Wearable Inertial Measurement Units. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2018, 26, 1243–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slušnienė, A.; Laucevičius, A.; Navickas, P.; Ryliškytė, L.; Stankus, V.; Stankus, A.; Navickas, R.; Laucevičienė, I.; Kasiulevičius, V. Daily Heart Rate Variability Indices in Subjects with and without Metabolic Syndrome before and after the Elimination of the Influence of Day-Time Physical Activity. Medicina 2019, 55, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boardman, A.; Schlindwein, F.S.; Rocha, A.P.; Leite, A. A Study on the Optimum Order of Autoregressive Models for Heart Rate Variability. Physiol. Meas. 2002, 23, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, E.M.; Sant’Anna, M.L.; Andreão, R.V.; Gonçalves, C.P.; Morra, E.A.; Baldo, M.P.; Rodrigues, S.L.; Mill, J.G. Spectral Analysis of Heart Rate Variability with the Autoregressive Method: What Model Order to Choose? Comput. Biol. Med. 2012, 42, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callara, A.L.; Sebastiani, L.; Vanello, N.; Scilingo, E.P.; Greco, A. Parasympathetic-Sympathetic Causal Interactions Assessed by Time-Varying Multivariate Autoregressive Modeling of Electrodermal Activity and Heart-Rate-Variability. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 68, 3019–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazeran, H.; Chatlapalli, S.; Krishnam, R. Effect of Novel Nanoscale Energy Patches on Spectral and Nonlinear Dynamic Features of Heart Rate Variability Signals in Healthy Individuals during Rest and Exercise. Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2005, 2005, 5563–5567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, L.K.; Al Kouzbary, M.; Al Kouzbary, H.; Liu, J.; Abu Osman, N.A. Estimation of Body Segmental Orientation for Prosthetic Gait Using a Nonlinear Autoregressive Neural Network with Exogenous Inputs. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 2023, 46, 1723–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polak, A.G.; Klich, B.; Saganowski, S.; Prucnal, M.A.; Kazienko, P. Processing Photoplethysmograms Recorded by Smartwatches to Improve the Quality of Derived Pulse Rate Variability. Sensors 2022, 22, 7047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).