Submitted:

21 August 2025

Posted:

21 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

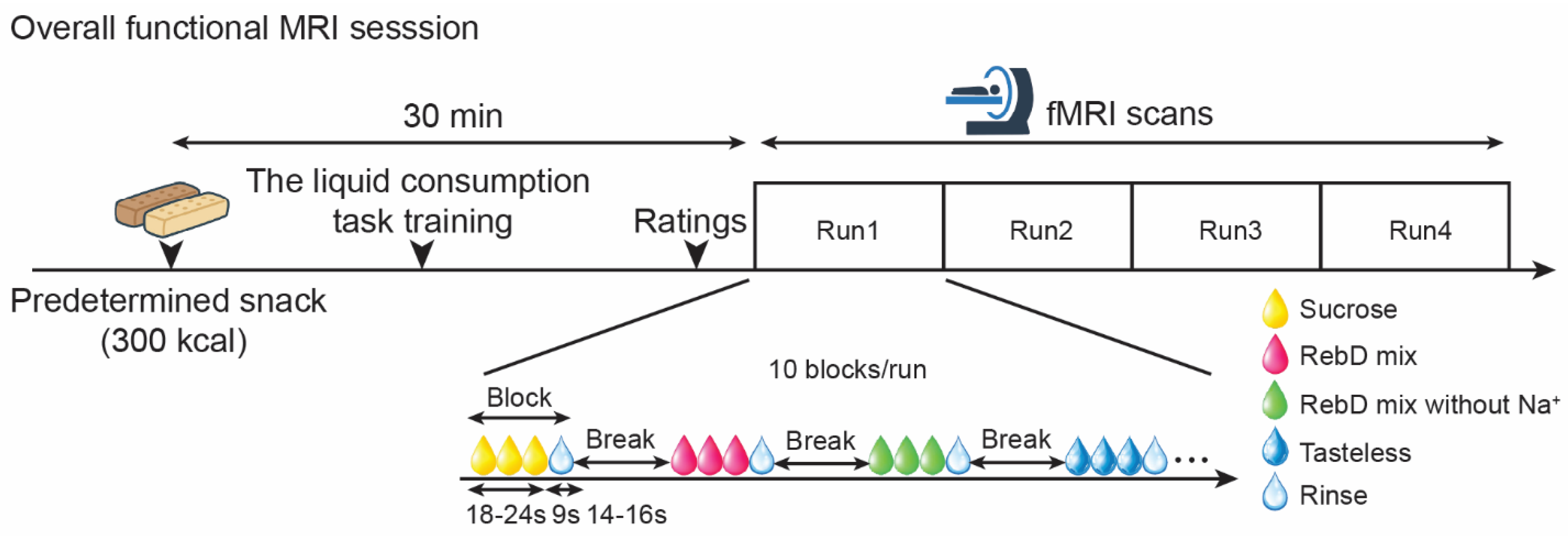

2.2. fMRI Session

2.2.1. Solutions for the Liquid Consumption Task at the fMRI Session

2.2.2. Solution Delivery

2.2.3. The Liquid Consumption Task

2.2.4. MR Image Acquisition

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

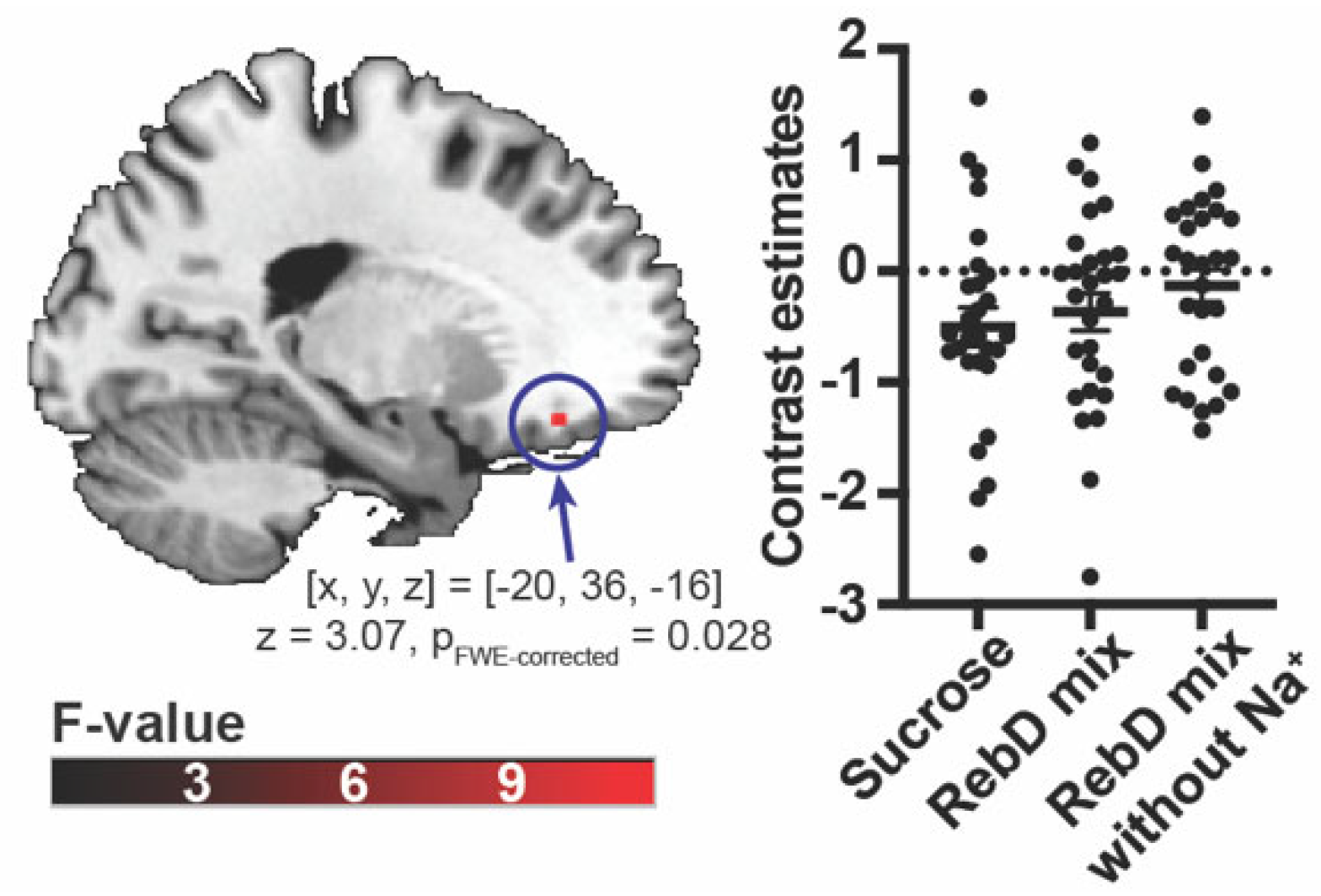

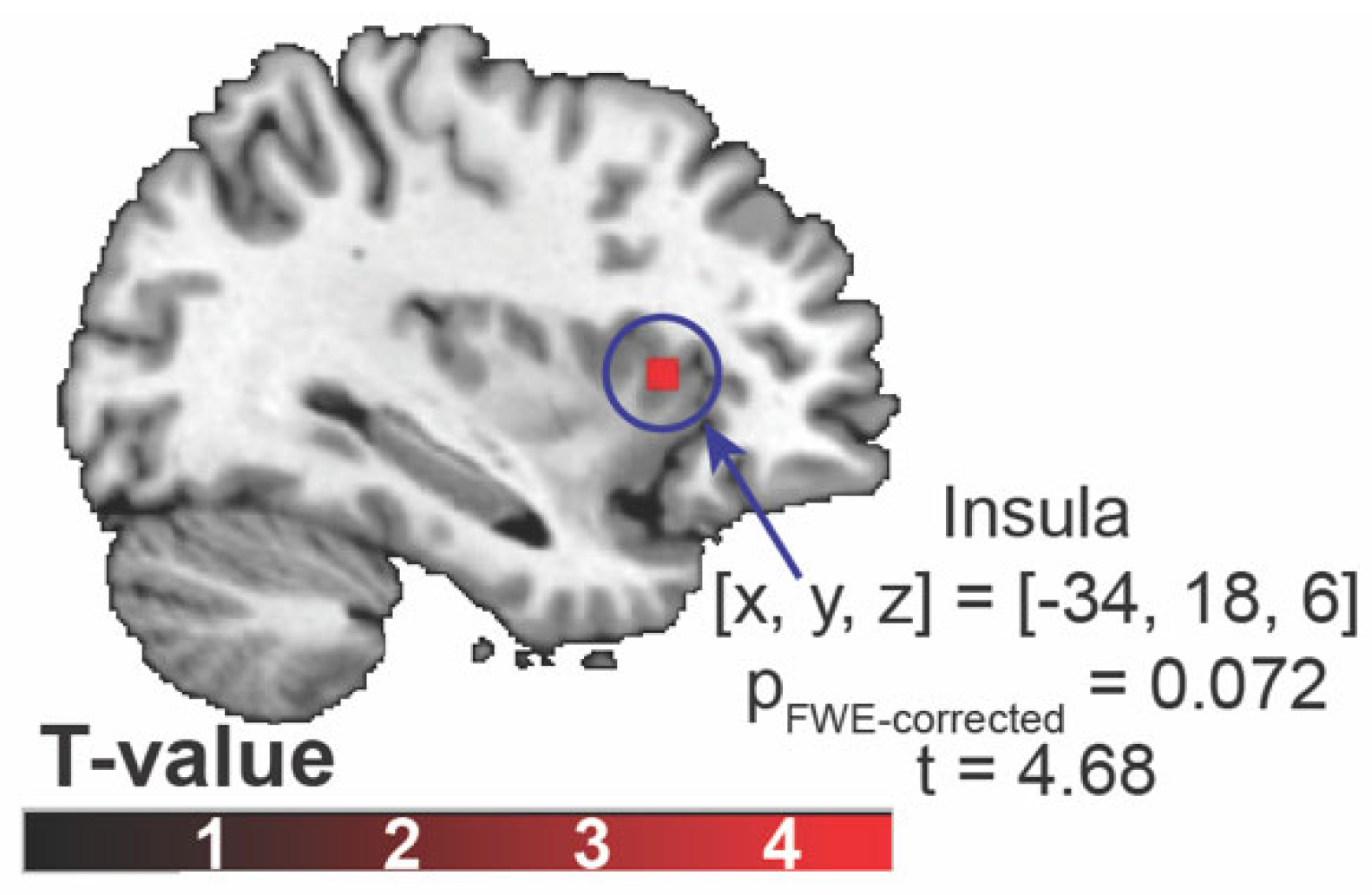

3.1. Brain Response to Each Gustatory Condition

3.2. Results of Whole-Brain Searchlight MVPA

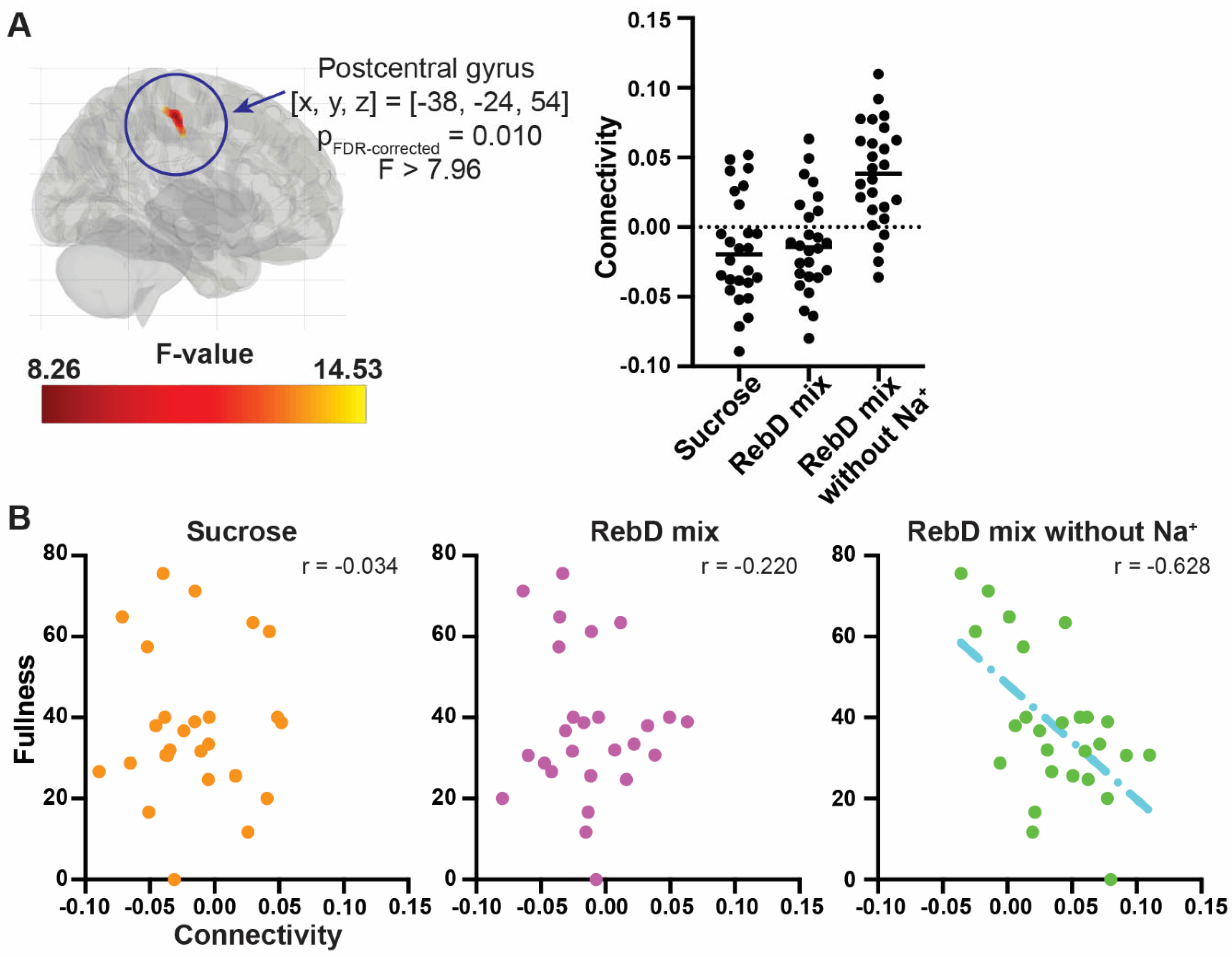

3.3. Connectivity Analysis with the gPPI

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sørensen, T.I.A. Forecasting the global obesity epidemic through 2050. The Lancet 2025, 405, 756–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, V.S.; Hu, F.B. The role of sugar-sweetened beverages in the global epidemics of obesity and chronic diseases. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2022, 18, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.; Jarvis, S.E.; Tinajero, M.G.; Yu, J.; Chiavaroli, L.; Mejia, S.B.; Khan, T.A.; Tobias, D.K.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. , et al. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies and randomized controlled trials. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2023, 117, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, V.W.K.; Wee, M.S.M.; Tomic, O.; Forde, C.G. Temporal sweetness and side tastes profiles of 16 sweeteners using temporal check-all-that-apply (TCATA). Food Research International 2019, 121, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, A.W.K.; Wong, N.S.M. How Does Our Brain Process Sugars and Non-Nutritive Sweeteners Differently: A Systematic Review on Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Studies. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, G.K.W.; Oberndorfer, T.A.; Simmons, A.N.; Paulus, M.P.; Fudge, J.L.; Yang, T.T.; Kaye, W.H. Sucrose activates human taste pathways differently from artificial sweetener. NeuroImage 2008, 39, 1559–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohner, S.; Toews, I.; Meerpohl, J.J. Health outcomes of non-nutritive sweeteners: analysis of the research landscape. Nutrition Journal 2017, 16, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceunen, S.; Geuns, J.M.C. Steviol Glycosides: Chemical Diversity, Metabolism, and Function. Journal of Natural Products 2013, 76, 1201–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemus-Mondaca, R.; Vega-Gálvez, A.; Zura-Bravo, L.; Ah-Hen, K. Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni, source of a high-potency natural sweetener: A comprehensive review on the biochemical, nutritional and functional aspects. Food Chem 2012, 132, 1121–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, I.; Dubois, G.E.; Clos, J.F.; Wilkens, K.L.; Fosdick, L.E. Development of rebiana, a natural, non-caloric sweetener. Food Chem Toxicol 2008, 46 Suppl 7, S75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suez, J.; Cohen, Y.; Valdés-Mas, R.; Mor, U.; Dori-Bachash, M.; Federici, S.; Zmora, N.; Leshem, A.; Heinemann, M.; Linevsky, R. , et al. Personalized microbiome-driven effects of non-nutritive sweeteners on human glucose tolerance. Cell 2022, 185, 3307–3328.e3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellfritsch, C.; Brockhoff, A.; Stähler, F.; Meyerhof, W.; Hofmann, T. Human psychometric and taste receptor responses to steviol glycosides. J Agric Food Chem 2012, 60, 6782–6793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoo, Y.; Ohkuri, T.; Fujie, A. Food and drink with increased sweetness. JP6705945B2, 2020-06-03, 2020.

- Vandenbeuch, A.; Kinnamon, S.C. Why low concentrations of salt enhance sweet taste. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2020, 230, e13560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breslin, P.A.S.; Izumi, A.; Tharp, A.; Ohkuri, T.; Yokoo, Y.; Flammer, L.J.; Rawson, N.E.; Margolskee, R.F. Evidence that human oral glucose detection involves a sweet taste pathway and a glucose transporter pathway. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0256989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, G.; Hoon, M.A.; Chandrashekar, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ryba, N.J.; Zuker, C.S. Mammalian sweet taste receptors. Cell 2001, 106, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.Q.; Zhang, Y.; Hoon, M.A.; Chandrashekar, J.; Erlenbach, I.; Ryba, N.J.; Zuker, C.S. The receptors for mammalian sweet and umami taste. Cell 2003, 115, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, E.M.; Loo, D.D.F.; Hirayama, B.A. Biology of Human Sodium Glucose Transporters. Physiological Reviews 2011, 91, 733–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, K.K.; Sukumaran, S.K.; Kotha, R.; Gilbertson, T.A.; Margolskee, R.F. Glucose transporters and ATP-gated K<sup>+</sup> (K<sub>ATP</sub>) metabolic sensors are present in type 1 taste receptor 3 (T1r3)-expressing taste cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108, 5431–5436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasumatsu, K.; Ohkuri, T.; Yoshida, R.; Iwata, S.; Margolskee, R.F.; Ninomiya, Y. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 as a sugar taste sensor in mouse tongue. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2020, 230, e13529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolls, E.T. The functions of the orbitofrontal cortex. Brain Cogn 2004, 55, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, D.M.; Bender, G.; Veldhuizen, M.G.; Rudenga, K.; Nachtigal, D.; Felsted, J. The role of the human orbitofrontal cortex in taste and flavor processing. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2007, 1121, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Ishida, T. The effect of multiband sequences on statistical outcome measures in functional magnetic resonance imaging using a gustatory stimulus. NeuroImage 2024, 300, 120867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penny, W.D.; Friston, K.J.; Ashburner, J.T.; Kiebel, S.J.; Nichols, T.E. Statistical Parametric Mapping: The Analysis of Functional Brain Images; Academic Press: 2011.

- Nieto-Castanon, A.; Whitfield-Gabrieli, S. CONN functional connectivity toolbox: RRID SCR_009550, release 22; Hilbert Press: 2022. [CrossRef]

- Whitfield-Gabrieli, S.; Nieto-Castanon, A. Conn: a functional connectivity toolbox for correlated and anticorrelated brain networks. Brain Connect 2012, 2, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Castanon, A. FMRI minimal preprocessing pipeline. In Handbook of functional connectivity Magnetic Resonance Imaging methods in CONN, Hilbert Press: 2020. 3–16. [CrossRef]

- Henson, R.; Buechel, C.; Josephs, O.; Friston, K.J. The slice-timing problem in event-related fMRI. NeuroImage 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sladky, R.; Friston, K.J.; Tröstl, J.; Cunnington, R.; Moser, E.; Windischberger, C. Slice-timing effects and their correction in functional MRI. Neuroimage 2011, 58, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, J.L.; Hutton, C.; Ashburner, J.; Turner, R.; Friston, K. Modeling geometric deformations in EPI time series. Neuroimage 2001, 13, 903–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K.J.; Ashburner, J.; Frith, C.D.; Poline, J.-B.; Heather, J.D.; Frackowiak, R.S.J. Spatial registration and normalization of images. Human Brain Mapping 1995, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitfield-Gabrieli, S.; Nieto-Castanon, A.; Ghosh, S. Artifact detection tools (ART). Cambridge, MA. Release Version 2011, 7, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Power, J.D.; Mitra, A.; Laumann, T.O.; Snyder, A.Z.; Schlaggar, B.L.; Petersen, S.E. Methods to detect, characterize, and remove motion artifact in resting state fMRI. Neuroimage 2014, 84, 320–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, V.D.; Wager, T.D.; Krishnan, A.; Rosch, K.S.; Seymour, K.E.; Nebel, M.B.; Mostofsky, S.H.; Nyalakanai, P.; Kiehl, K. The impact of T1 versus EPI spatial normalization templates for fMRI data analyses. Hum Brain Mapp 2017, 38, 5331–5342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, J.; Friston, K.J. Unified segmentation. Neuroimage 2005, 26, 839–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, J. A fast diffeomorphic image registration algorithm. Neuroimage 2007, 38, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarkoni, T.; Poldrack, R.A.; Nichols, T.E.; Van Essen, D.C.; Wager, T.D. Large-scale automated synthesis of human functional neuroimaging data. Nature Methods 2011, 8, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzourio-Mazoyer, N.; Landeau, B.; Papathanassiou, D.; Crivello, F.; Etard, O.; Delcroix, N.; Mazoyer, B.; Joliot, M. Automated Anatomical Labeling of Activations in SPM Using a Macroscopic Anatomical Parcellation of the MNI MRI Single-Subject Brain. NeuroImage 2002, 15, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldjian, J.A.; Laurienti, P.J.; Kraft, R.A.; Burdette, J.H. An automated method for neuroanatomic and cytoarchitectonic atlas-based interrogation of fMRI data sets. Neuroimage 2003, 19, 1233–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldjian, J.A.; Laurienti, P.J.; Burdette, J.H. Precentral gyrus discrepancy in electronic versions of the Talairach atlas. Neuroimage 2004, 21, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriegeskorte, N.; Goebel, R.; Bandettini, P. Information-based functional brain mapping. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2006, 103, 3863–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebart, M.N.; Görgen, K.; Haynes, J.-D. The Decoding Toolbox (TDT): a versatile software package for multivariate analyses of functional imaging data. Frontiers in Neuroinformatics 2015, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, A.M.; Ridgway, G.R.; Webster, M.A.; Smith, S.M.; Nichols, T.E. Permutation inference for the general linear model. Neuroimage 2014, 92, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.M.; Nichols, T.E. Threshold-free cluster enhancement: Addressing problems of smoothing, threshold dependence and localisation in cluster inference. NeuroImage 2009, 44, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friston, K.J.; Buechel, C.; Fink, G.R.; Morris, J.; Rolls, E.; Dolan, R.J. Psychophysiological and modulatory interactions in neuroimaging. Neuroimage 1997, 6, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaren, D.G.; Ries, M.L.; Xu, G.; Johnson, S.C. A generalized form of context-dependent psychophysiological interactions (gPPI): a comparison to standard approaches. Neuroimage 2012, 61, 1277–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worsley, K.J.; Marrett, S.; Neelin, P.; Vandal, A.C.; Friston, K.J.; Evans, A.C. A unified statistical approach for determining significant signals in images of cerebral activation. Hum Brain Mapp 1996, 4, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumbley, J.; Worsley, K.; Flandin, G.; Friston, K. Topological FDR for neuroimaging. NeuroImage 2010, 49, 3057–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, T.J.; Liu, Z.; Ly, T.; Shehata, S.; Sivakumar, N.; La Santa Medina, N.; Gray, L.A.; Zhang, J.; Dundar, N.; Barnes, C.; et al. Negative feedback control of hypothalamic feeding circuits by the taste of food. Neuron 2024, 112, 3354–3370.e3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. ppcor: An R Package for a Fast Calculation to Semi-partial Correlation Coefficients. Commun Stat Appl Methods 2015, 22, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, J.H. Tests for comparing elements of a correlation matrix. Psychological Bulletin 1980, 87, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diedenhofen, B.; Musch, J. cocor: A Comprehensive Solution for the Statistical Comparison of Correlations. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0121945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldhuizen, M.G.; Gitelman, D.R.; Small, D.M. An fMRI Study of the Interactions Between the Attention and the Gustatory Networks. Chemosens Percept 2012, 5, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avery, J.A.; Liu, A.G.; Ingeholm, J.E.; Gotts, S.J.; Martin, A. Viewing images of foods evokes taste quality-specific activity in gustatory insular cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118, e2010932118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, N.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Lai, H.; Qin, K.; Li, J.; Biswal, B.B.; Sweeney, J.A.; Gong, Q. Brain gray matter structures associated with trait impulsivity: A systematic review and voxel-based meta-analysis. Human Brain Mapping 2021, 42, 2214–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filbey, F.M.; Schacht, J.P.; Myers, U.S.; Chavez, R.S.; Hutchison, K.E. Marijuana craving in the brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2009, 106, 13016–13021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegman, J.; van Loon, I.; Smeets, P.A.M.; Cools, R.; Aarts, E. Top-down expectation effects of food labels on motivation. Neuroimage 2018, 173, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, P.; Onishi, A.; Koepsell, H.; Vallon, V. Sodium glucose cotransporter SGLT1 as a therapeutic target in diabetes mellitus. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2016, 20, 1109–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorboulev, V.; Schürmann, A.; Vallon, V.; Kipp, H.; Jaschke, A.; Klessen, D.; Friedrich, A.; Scherneck, S.; Rieg, T.; Cunard, R. , et al. Na(+)-D-glucose cotransporter SGLT1 is pivotal for intestinal glucose absorption and glucose-dependent incretin secretion. Diabetes 2012, 61, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriya, R.; Shirakura, T.; Ito, J.; Mashiko, S.; Seo, T. Activation of sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 ameliorates hyperglycemia by mediating incretin secretion in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2009, 297, E1358–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astrup, A. Reflections on the discovery GLP-1 as a satiety hormone: Implications for obesity therapy and future directions. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2024, 78, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, A.W.K.; Wong, N.S.M.; Eickhoff, S.B. Empirical assessment of changing sample-characteristics in task-fMRI over two decades: An example from gustatory and food studies. Hum Brain Mapp 2020, 41, 2460–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age (years) |

Sex (male / female) |

Body mass index (kg/m2) |

Fullness | Hunger | |

| Mean ± S.D. | 22.36 ± 5.20 | 22 / 6 | 20.34 ± 2.22 | 45.56 ± 20.63 | 37.97 ± 18.68 |

| Range | 18 - 42 | 15.41 - 24.91 | 13.62 - 90.40 | 0.00 - 75.55 |

| Sucrose | RebD mix | RebD mix without Na+ | p-value* | ||

| Liking | Mean ± S.E. | 56.21 ± 3.61 | 55.54 ± 4.03 | 57.44 ± 2.62 | 0.937 |

| Range | 21.53 - 83.46 | 8.11 - 87.29 | 31.84 - 91.89 | ||

| Wanting | Mean ± S.E. | 54.56 ± 3.55 | 53.11 ± 4.03 | 49.88 ± 3.58 | 0.895 |

| Range | 22.57 - 96.11 | 23.74 - 86.71 | 16.02 - 86.64 | ||

| Intensity | Mean ± S.E. | 51.79 ± 3.43 | 50.43 ± 3.85 | 49.14 ± 3.35 | 0.063 |

| Range | 7.39 - 80.61 | 0.00 - 89.95 | 21.73 - 89.36 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).