1. Introduction

Bone grafting, augmentation, and related procedures—including tissue regeneration: regeneration, restoration, reconstruction, replacement, and repair—rank among the most commonly performed interventions worldwide, second only to blood transfusion, with over two million cases annually, and demand continuing to rise. [

1,

2]. Despite their widespread use, conventional/traditional graft materials—autografts, allografts, xenografts, and synthetic substitutes—are often limited by donor site morbidity, restricted availability, high cost, immunogenic risks, restricted malleability, and sub-optimal biological performance, amongst others [

3]. These challenges underscore the urgent need for innovative biomaterials that can safely and effectively promote localized

de novo bone regeneration [

3]. Henceforth, biomaterials that actively, safely and efficaciously, induce, enhance, and accelerate biomineralization, osteo-conduction, and -induction are particularly valuable in advancing orthopaedic, oro-dental, and cranio-maxillo-facial therapies [

3,

4,

5].

Hydroxyapatite (HAp: Ca_10(PO_4)_6(OH)_2), the primary mineral component of bone, is extensively used in bioceramics due to its biocompatibility and osteoconductive properties [

6,

7]. While HAp can be sourced from synthetic and natural origins including human and animal bones, fish bones have recently gained attention as a sustainable and abundant alternative. This approach leverages the considerable volume of fish bone waste generated globally by the fishing and aquaculture industries, which otherwise presents environmental disposal challenges. Indeed, Chile’s salmon farming industry, a significant global supplier, produces large quantities of byproducts such as scales, skin, and bones [

8]. Valorization of these residues is essential to address environmental concerns while providing economic and health benefits [

5]. Henceforth, extracting hydroxyapatite from salmon bones offers a sustainable, environment-friendly, and low-cost route to novel biomaterials, with potential advantages over traditional sources including prion safety, cultural and religious acceptability when compared to bovine or porcine materials [

7,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

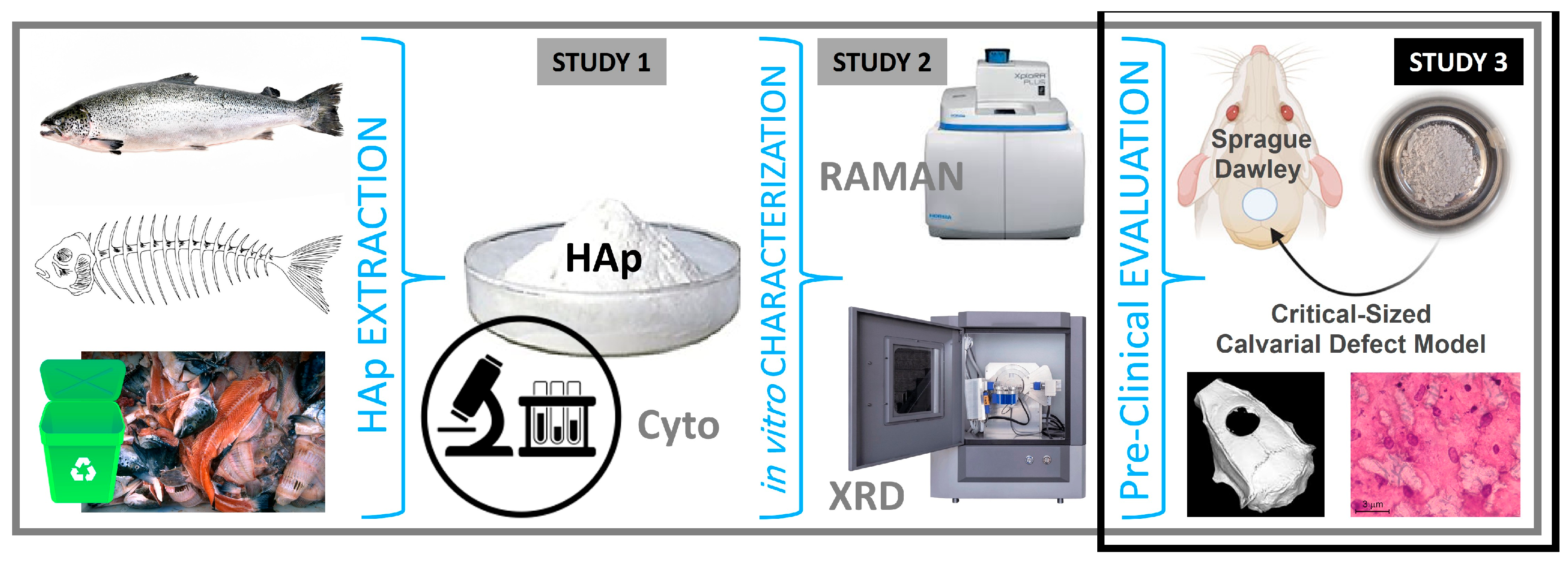

Figure 1.

From Waste to Graft: Progression from Hydroxyapatite (HAp) Extraction, Production, and in vitro Characterization to Pre-Clinical Evaluation of Salmon Fishbone-Derived HAp in an Animal Model as a safe, effective and sustainable Bone Graft Material.

Figure 1.

From Waste to Graft: Progression from Hydroxyapatite (HAp) Extraction, Production, and in vitro Characterization to Pre-Clinical Evaluation of Salmon Fishbone-Derived HAp in an Animal Model as a safe, effective and sustainable Bone Graft Material.

In our previous work [

10], we developed a novel nano-structured salmon backbone-derived hydroxyapatite (nanoS-HAp) using a modified, simplified, and optimized alkaline hydrolysis–calcination process and demonstrated its superior physico-chemico-mechanical properties, optimal Ca/P ratio, and enhanced in vitro biocompatibility relative to conventional HAp sources [

10]. We subsequently fine-tuned the extraction process at lab scale, confirming the material’s high crystallinity and favorable nano-scale features, suitable for clinical and surgical bone tissue engineering applications [

11]. Herein, following and building on these foundational in vitro studies, the present work focuses on evaluating the osteogenic efficacy and biocompatibility of salmon-derived hydroxyapatite (nanoS-HAp) in vivo. We investigate its bone regenerative potential and systemic safety using a critical-sized calvarial defect model in rats, aiming to demonstrate SAHA as a bio-effective, malleable, and sustainable alternative to conventional bone grafts, with a substantial potential for translation; evaluation in clinical trials, and practical use in surgeries.

2. Materials and Methods

The hydroxyapatite material (nanoS-HAp) used in this study was derived, extracted and produced from salmon fish backbone via a novel, patent-pending alkaline hydrolysis–calcination process developed and optimized in our collaborative laboratories [

10,

11]. This processing protocol efficiently isolates the mineral phase by removing organic components such as proteins and lipids, yielding a high-purity nano-structured hydroxyapatite (nanoS-HAp). Physico-chemical and mechanical characterization including X-ray diffraction, Raman spectroscopy, electron microscopy, and spectroscopy, to mention a few, demonstrated that the resulting nanoS-HAp exhibits a highly crystalline structure with an optimal Ca/P ratio and nano-scale morphology suitable and favorable for

de novo bone regeneration. Moreover, the SAHA material’s biocompatibility, cellular/tissular characteristics, and osteoinductive properties were also previously confirmed through extensive in vitro cell viability and biological assays, positioning our nanoS-HAp/SAHA as a promising biomaterial for regenerative medicine indications and applications (i.e. particularly well-suited for simple and complex bone regeneration and repair applications— comparable to or even surpass those of synthetic, human, bovine, and porcine hydroxyapatite, positioning it as a promising candidate for use in tissue bio-engineering, wound healing, and bone regenerative and reparative interventions [

10,

11]. Here, we advance to assess the pre-clinical characteristics and bio-performance of nanoS-HAp/SAHA, in vivo.

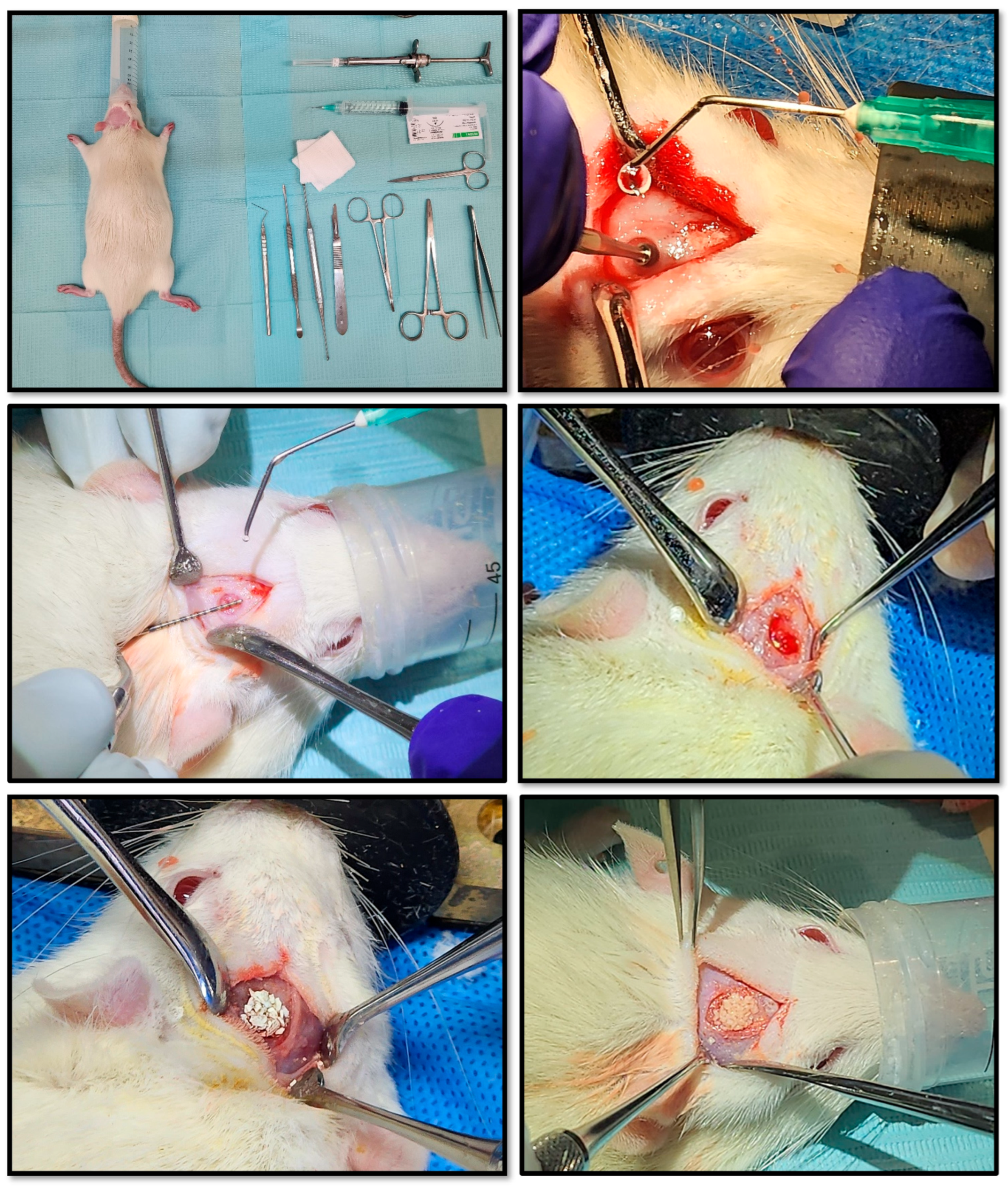

Twenty-one healthy male adult rats, laboratory-born/-bred, weighing between 250 and 300 grams, were randomized into three main groups of seven animals each. Each group corresponded to one of three post-operative evaluation time points: 15, 30, and 60 days. Within each time group, animals were sub-divided to receive different grafting materials, for comparative analysis. Animals were housed in a controlled environment, under standardized conditions, and routinely monitored and assessed for health and welfare. Sprague–Dawley rats were used for the in vivo experiments, as the critical-sized calvarial defect model in this species is a gold-standard approach for assessing the osteo-conductive and osteo-inductive potential of novel bone grafting materials, providing reproducible, quantifiable outcomes that closely mimic clinical challenges in cranio-maxillo-facial bone repair. The calvarial model offers a flat, easily accessible site with minimal movement, allowing for standardized defect sizes (often 5 mm in rats, which is “critical-size,” meaning it won’t heal spontaneously) — ideal for assessing new material performance in a controlled setting. It also serves as a validated preliminary step toward dental (such as alveolar ridge augmentation post-exodontia and sinus floor elevation/lift procedures) and certain non-load-bearing orthopaedic applications such as segmental defects.

Under general anesthesia, a linear incision was made along the cranial midline after depilation. Using a scalpel with a 15-blade and surgical retractors, the parietal bone was exposed. A critical-sized calvarial defect (5 mm diameter) was created with a surgical micromotor (NSK SurgiPro, Japan) fitted with a #3 round drill bit, operating at 800 rpm under constant sterile saline irrigation. Care was taken not to perforate the dura mater when removing the bone fragment. Hemostasis was achieved using sterile gauze as was needed.

The defect was then filled with one of the following graft materials/treatments:

C-0: Negative control (no graft material)

E-1: Synthetic HAp (SHA) (Sigma Aldrich®, Germany)

E-2: Porcine xenograft HAp (PHA) (The Graft, Pure Biologics, USA)

E-3: Bovine xenograft HAp (BHA) (Mineross Cortical X, Biohorizons, USA)

E-4: Human allograft HAp (HHA) (OraGraft Mineralized Cortical, Lifenet Health, USA)

E-5: Salmon biograft HAp (SAHA)

Figure 2.

Pre-Clinical Surgical Protocol. Workflow for creating standardized cranial defects in rats and applying the experimental bone graft materials. After preparing the armamentarium and animals, defects are created and measured for uniformity, then grafts are applied according to randomization (N = 21, incl. empty/void control defects).

Figure 2.

Pre-Clinical Surgical Protocol. Workflow for creating standardized cranial defects in rats and applying the experimental bone graft materials. After preparing the armamentarium and animals, defects are created and measured for uniformity, then grafts are applied according to randomization (N = 21, incl. empty/void control defects).

Assigned graft materials were carefully inserted into the defect, packed gently to fill the space, and shaped to conform to the defect margins. After re-ensuring the complete and uniform graft placement, the subcutaneous tissue and skin were closed in layers using a 3.0 nylon thread suture. Post-operative analgesia (Tramadol, 20–40 mg/kg) was administered subcutaneously every 12 hours for 48 hours starting at anesthesia induction. Antibiotic prophylaxis with Enrofloxacin (10 mg/kg) was given in 2 subcutaneous doses: pre-operative and post-operative. Animals were monitored post-operatively for pain, infection, and general health, with analgesics administered according to institutional guidelines. All procedures were performed under aseptic conditions and in accordance with institutional animal care and use protocols approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee and the BioResearch Center of the Universidad de los Andes in Santiago de Chile.

Animals were euthanized on post-operative days 15, 30, and 60 by intra-peritoneal overdose of ketamine (300 mg/kg) and xylazine (30 mg/kg). Remains were handled in accordance with the biosafety protocols of the BioResearch Center and Universidad de los Andes, and disposed of by STU Ltda in compliance with institutional guidelines, with the harvested samples promptly collected for processing, imaging, and histological analyses.

Blood samples were also collected via saphenous vein puncture under general anesthesia (ketamine/xylazine 100/10 mg/kg). Baseline samples were taken pre-surgery; and follow-up samples were collected at 30 and 60 days post-op. Serum biochemical parameters measured included total protein, albumin, total bilirubin, AST, ALT, alkaline phosphatase, glucose, cholesterol, triglycerides, BUN, lactic acid dehydrogenase, creatinine, sodium, potassium, chloride, calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium. Hematologic analysis covered erythrocytes, leukocytes, neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils, hemoglobin, hematocrit, and platelets, using an automated hematologic analyzer. C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were also assessed as an immune status indicator. Blood was centrifuged at 1000g for 10 minutes and plasma stored at –80°C until analysis.

Bone regeneration was evaluated using three-dimensional cone beam computed tomography (ConeBeam CT, Sirona Orthophos XG, Spain). Following euthanasia, rats were transported according to biosafety protocols to the imaging facility. Bone density within the defect, both centrally and at margins, was quantified. The defect’s aspect ratio was calculated as the transverse width divided by the sagittal length, providing a dimensionless measure of defect shape. Imaging was performed at 15, 30, and 60 days post-surgery.

Specimens were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, rinsed, and decalcified in 18% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). Each sample was bisected longitudinally along the centerline of the surgical defect and then sectioned at 10 μm thickness. Sections were then mounted on slides and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Von Willebrand factor (vWF), and alpha smooth muscle actin (α-SMA). Antigen retrieval was performed with proteinase K, for 20 minutes at 37°C. Images were captured by a single blinded examiner using an optical microscope equipped with a digital camera at 40× and 200× magnifications to evaluate de novo (new) bone formation within the calvarial defects.

3. Results

3.1. Biocompatibility Analysis

Biochemical and hematological analyses were conducted to evaluate the systemic health of rats at 30 and 60 days post-graft implantation.

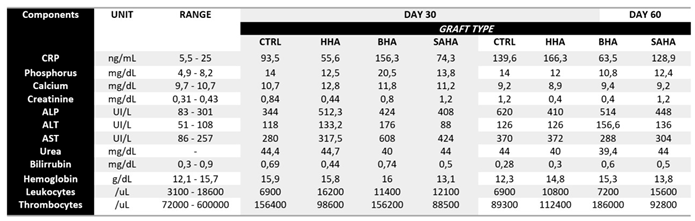

Table 1 summarizes the key parameters, including inflammatory markers, indicators of kidney and liver function, and mineral levels relevant to bone metabolism. Briefly, these measurements were selected to provide a comprehensive assessment of the animals’ physiological status, ensuring that the implanted graft materials did/not provoke any significant adverse systemic effects. Herein, C-reactive protein (CRP), a sensitive marker of systemic inflammation, showed no significant differences among the graft groups and controls at either time point, suggesting that the biomaterials did not elicit inflammatory or immune reactions. Kidney function markers, including creatinine and urea, also remained stable across groups, indicating preserved renal function and the absence of nephrotoxicity associated with graft implantation. Liver function tests—including alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and bilirubin—were comparable between grafted and control animals, further supporting the systemic safety of the materials. The ALT/AST ratio remained below 1 in all cases, consistent with the absence of liver injury or inflammation (any mild elevation in AST is more likely of a non-hepatic origin). In the context of this study, the ratio below 1 across all graft groups suggests that the implantation of SAHA did not induce hepatocellular damage, systemic stress, or inflammation. This finding further supports the hepatic safety of nanoS-HAp and suitability for clinical applications, including repeated or long-term exposure interventional scenarios.

Hematological parameters, including hemoglobin concentration, leukocyte counts, and platelet numbers, were similarly unaffected by the implanted grafting materials. These results collectively indicate that the salmon-derived hydroxyapatite materials were well tolerated and did not induce hematological disturbances or systemic toxicity over the course of the study. Therefore, the findings support the biocompatibility of our novel material and its suitability to advance to clinical evaluation in bone regeneration applications.

Table 1.

Biochemical and Hematological Profiles of Rats implanted with Salmon-derived HAp (SAHA) and the other commercial grafting materials at 30 and 60 days post-operatively. CRP: C-Reactive Protein; ALP: Alkaline Phosphatase; ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase; Urea: Blood Urea Nitrogen; CTRL: Control Defect

Table 1.

Biochemical and Hematological Profiles of Rats implanted with Salmon-derived HAp (SAHA) and the other commercial grafting materials at 30 and 60 days post-operatively. CRP: C-Reactive Protein; ALP: Alkaline Phosphatase; ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase; Urea: Blood Urea Nitrogen; CTRL: Control Defect

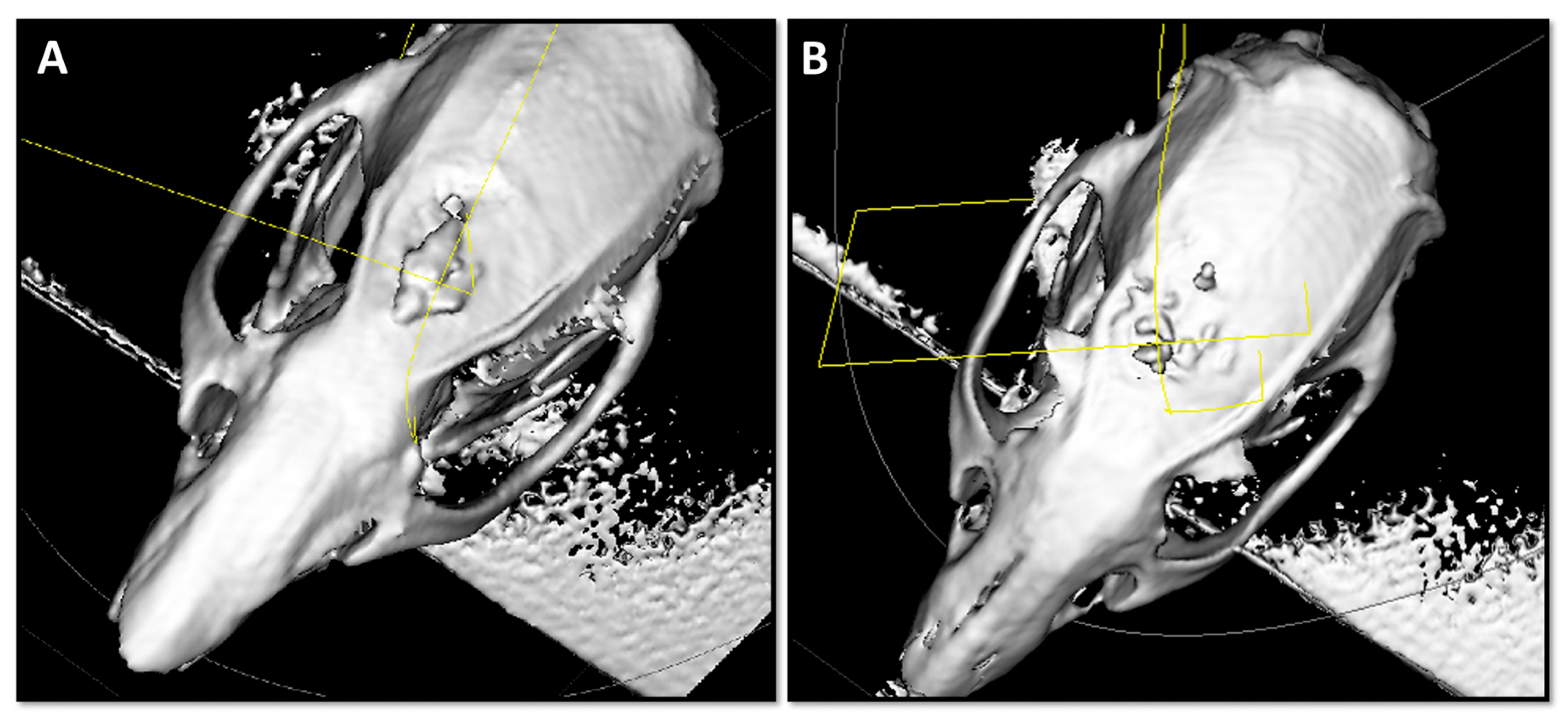

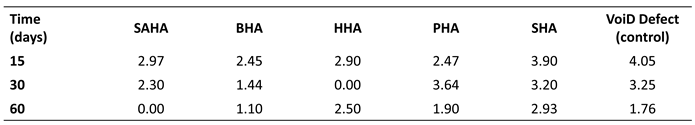

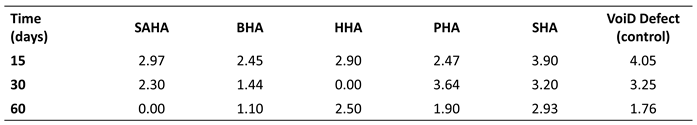

3.2. Imaging Analysis

CBCT or cone beam computed tomography was employed to evaluate localized bone defect regeneration at 15, 30, and 60 days post-implantation. At 15 days, the calvarial defects treated with the SAHA graft material and the bovine xenograft or BHA exhibited smaller diameters relative to the other groups, accompanied by an evident bone callus formation indicative of an increased metabolic activity. However, the newly-regenerated bone surface did demonstrate slight irregularities and heterogeneity in tissue growth patterns. Interestingly, at the 60 days time-point, the smallest calvarial defect diameter was observed in the SAHA group, suggesting superior bone regeneration. In contrast, defects treated with other grafts displayed slightly larger diameters than the empty defect controls, which followed natural healing patterns, typical to the rat model. Herein, these findings demonstrate that SAHA promotes more rapid and organized bone formation, with enhanced closure of critical-sized defects. Representative CBCT images at 15 days are shown in

Figure 3, illustrating early bone growth with the SAHA (A) and BHA (B) grafts.

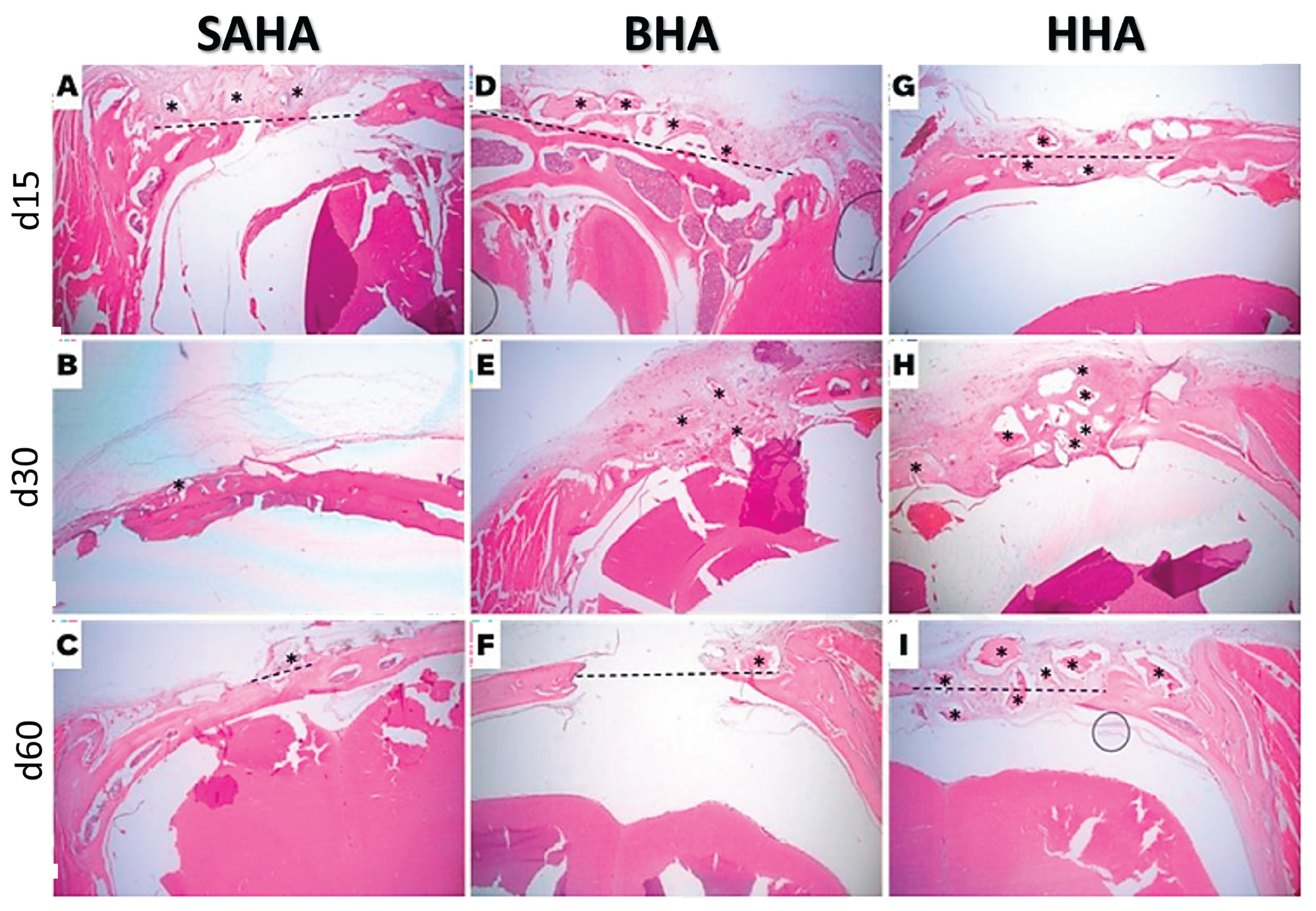

3.3. Histological Analysis

Histological examination was performed to assess new bone formation, inflammatory response, and graft integration at 15, 30, and 60 days post-implantation. At 15 days, and as expected, all grafted samples exhibited pronounced inflammatory signs, including infiltration of immune cells and multinucleated giant cells surrounding the implanted materials, reflecting the initial host response to foreign biomaterials. By day 30, the inflammation persisted only in the human allograft group, correlating with delayed superficial wound healing and higher pain scores as assessed using the rat Grimace scale. In contrast, the other graft-treated groups showed a progressive resolution of early inflammatory responses, indicating a favorable tissue tolerance. By day 60, inflammatory signs were absent across all groups, consistent with normal healing and graft acceptance.

Encapsulation of the graft material was observed in all groups at early time points. In the SAHA samples, encapsulation was evident at d15 and d30, and by d60, vital bone tissue was observed within the encapsulated areas alongside the residual graft material, demonstrating ongoing osteointegration and gradual replacement of the graft with newly- formed bone. Furthermore, graft efficacy, evaluated based on the resolution of inflammation, bone formation, and graft integration, indicated that the porcine xenograft performed most effectively, closely followed by the salmon-derived hydroxyapatite grafte material (SAHA). It was noted that the bovine xenograft and synthetic HAp grafts exhibited moderate performance, while the human allograft demonstrated the least efficacy among the materials tested. Hence, the ranking of graft performance from most to least effective was: porcine xenograft, salmon biograft, bovine xenograft, synethic, and finally the human allograft. Representative histological sections from rats implanted with salmon, bovine, and human grafts at days 15, 30, and 60 are shown in

Figure 4, illustrating progressive bone formation, resolution of inflammation, and graft integration over time.

4. Discussion

Bone formation is initiated by newly differentiated osteoblasts, which secrete an unmineralized extracellular matrix termed osteoid, composed primarily of collagen type I and other organic proteins that provide the structural framework for mineral deposition. This osteoid undergoes a tightly regulated biomineralization process, in which calcium (Ca²⁺) and phosphate (PO₄³⁻) ions from physiological fluids nucleate and crystallize to form hydroxyapatite (HAp: Ca₁₀(PO₄)₆(OH)₂), the primary mineral component of bone [

9,

10,

11,

12]. This

de novo bone formation, or osteogenesis, relies not only on the physical availability of calcium and phosphate but also on the local chemical environment and signaling cues that regulate osteoblast differentiation, maturation, and extracellular matrix mineralization [

2,

3,

4,

12]. HAp serves as more than a structural scaffold; its surface chemistry and nanoscale features influence protein adsorption, ion exchange, and growth factor binding, thereby modulating cellular signaling pathways, including BMP, Wnt/β-catenin, and integrin-mediated mechano-transduction, which collectively guide the proliferation and differentiation of osteoprogenitor cells [

9,

10,

11,

12]. The precise stoichiometry, crystallinity, and nanoscale morphology of HAp are therefore critical determinants of both the speed and quality of bone regeneration, ultimately dictating the expansion of the mineralized bone matrix and the successful integration of graft materials within a defect [

2,

3,

4,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

Our present in vivo study demonstrated that rats implanted with salmon-derived hydroxyapatite (SAHA) exhibited normal renal function and stable liver enzyme profiles, with ALT/AST ratios consistently below 1, indicating the absence of systemic toxicity or hepatocellular injury. Hematological parameters, including leukocyte, platelet, and hemoglobin counts, remained within the normal ranges, suggesting a stable immune response and preserved coagulation function post-implantation, without adverse hematological effects. These findings align with previous observations for HAp-based biomaterials [

9,

14,

15,

16,

17], reinforcing the local and systemic safety and biocompatibility of our SAHA.

Notably, animals receiving the salmon biograft showed markedly enhanced

de novo bone regeneration, evidenced by reduced defect diameters and robust bone callus formation (

Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4); a superior osteogenic performance consistent with the high biocompatibility and bioactivity previously observed in vitro [

10,

11,

12,

14]. Cyto-compatibility assays using C2C12 myoblasts and mouse embryonic fibroblasts confirmed that SAHA supports cell viability and proliferation significantly better than other HAp sources, with >90% cell viability even at higher concentrations (100–200 µg/mL). Such cellular responses indicate that SAHA provides a favorable microenvironment for localized osteogenesis, promoting adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation of osteoblasts into/within the site.

The outcomes of this in vivo study are consistent with, and directly extend, our previous in vitro findings [

10,

11], which had established the physico-chemical, structural, and cytological attributes of the salmon-derived HAp material relevant to bone regeneration. Indeed, physico-chemical characterization and analysis via XRD (X-ray diffraction) and Raman spectroscopy confirmed that the SAHA material possesses a highly crystalline structure with crystallite sizes up to 60.38 nm, which is within the optimal nano-scale range for new bone regeneration [

2,

4,

10,

11,

12,

14,

15,

16,

17]. SEM/EDS analysis revealed a slightly elevated Ca/P ratio relative to stoichiometric HAp (1.67), consistent with reports suggesting enhanced bioactivity at these ratios [

4,

10,

11,

12,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Raman spectra identified key phosphate (PO₄³⁻) functional groups without detectable carbonate (CO₃²⁻) or hydroxyl (OH⁻) peaks, suggesting a distinctive mineral phase that may underlie SAHA’s unique biological performance [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Furthermore, the structural and compositional properties of SAHA likely underpin its superior bioactivity, promoting osteoblast adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation, which collectively enhance in vivo bone regeneration. In contrast, other graft materials, including bovine and human-derived HAp, showed less favorable outcomes, with larger defect diameters and, in the case of human allografts, persistent early inflammation. This chronic inflammatory response in the human graft group underscores potential immunogenicity issues absent in SAHA and other grafts, reinforcing our salmon-derived hydroxyapatite as a safer alternative. Furthermore, the encapsulation of exogenous material with fibrous tissue occurred in approximately 72% of SAHA-treated samples, likely due to particle size (250–1000 µm) relative to the 5 mm rat calvarial defects. While indicative of a typical foreign body response to particulate grafts, this encapsulation did not impair overall bone regeneration. Optimization of particle size distribution may further enhance graft integration and promote uniform bone growth. Although the rat critical-size calvarial model is a well-established platform for comparative evaluation of bone grafts, clinical translation will require testing in models that better replicate complex human defect geometries encountered in oral, cranio-maxillo-facial, and non-load-bearing orthopedic surgeries [

20]. Nonetheless, our reproducible and simplified extraction process/protocol [

10,

11]—combining alkaline hydrolysis, defatting, and calcination—provides a cost-friendly, environmentally sustainable and/or attractive alternative source and scalable technical method to competently produce bioactive nano-scaled HAp with favorable physico-chemico-mechanico-biological properties.

Collectively, these results demonstrate that salmon bone-derived nano-hydroxyapatite (SAHA) is a promising bone graft material, combining excellent in vitro cytocompatibility, optimal the structural and compositional properties, and effective in vivo osteoconductivity and pre-clinical biocompatibility. Beyond its regenerative performance and potential, SAHA can represent a model for sustainable biomaterial production from fishery waste, addressing both environmental and clinical needs in bone regeneration and repair.

5. Conclusions

The present study demonstrates that hydroxyapatite derived from Chilean salmon bone (nanoS-HAp/SAHA) exhibits excellent and highly-promising osteo-conductive, -inductive and biocompatible properties in vivo, comparable to established and commonly-used commercial bone grafts including bovine, porcine, and human allografts. The biochemical and hematological profiles of rats implanted with nanoS-HAp /SAHA remained stable, with no significant deviations from controls, indicating the absence of systemic toxicity or organ dysfunction. Notably, rats receiving the salmon biograft showed enhanced and accelerated de novo bone regeneration, evidenced by significantly smaller defect diameters and robust bone callus formation, thereby underscoring the osteogenic potential of this new biomaterial. It is nonetheless noteworthy that while some heterogeneity in bone growth was observed—likely due to particle size or graft handling—the overall transient inflammatory response supports SAHA as a safe and effective bone graft substitute. Building on the previous in vitro studies demonstrating nanoscale crystalline structure, optimal Ca/P ratio, and strong bioactivity, this in vivo validation further establishes SAHA as a viable, bioactive scaffold for bone regeneration and repair. Moreover, the reproducible, cost-effective extraction process from sustainably sourced fish bone waste provides an environmentally friendly and cost-effective alternative to traditional mammalian-derived grafts, aligning with the growing need for novel regenerative biomaterials and substitutes, that are effective, attainable, and ecologically responsible. To the best of knowledge, we strongly believe that SAHA represents a significant advancement in bone tissue engineering, merging scientific innovation with sustainability. Our ongoing research aims to optimize material processing for more consistent bone regeneration, extend preclinical studies to larger animal models, and advance toward clinical translation, including evaluation in clinical trials. These efforts hold promise for improving patient outcomes in osseous regenerative therapies while simultaneously addressing the challenges of biowaste valorization and promoting sustainability in biomedical and dental materials.

6. Patents

Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT)—(International) has been filed by the co-authors of this article.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.M. and Z.S.H.; Methodology, F.M., A.P. and Z.S.H.; Investigation, M.J.G., N.O. and Z.S.H.; Writing—original draft preparation, F.M., M.J.G. and Z.S.H.; Writing—review and editing, Z.S.H.; Final version review/editing, Z.S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research work was supported by operating grants provided through the CORFO Crea y Valida I+D+i Grant for the Chilean Salmon Fish Bone project; # 21CVC2-183641 (2022–2025).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board and the Ethics Committee of the UNIVERSIDAD DE LOS ANDES and the BioResearch Center (CiiB), respectively, under protocol C2-3641-II for the years 2023 and 2024, incl.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

All raw data underlying the results are included herein, and no additional source data are required.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge veterinarian Ms. Nataly Quezada, a member of the CiiB team at the Universidad de los Andes in Santiago de Chile, for her invaluable and continuous support to this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Starch-Jensen, T.; Deluiz, D.; Deb, S.; Bruun, N.H.; Tinoco, E.M.B. Harvesting of autogenous bone graft from the ascending mandibular ramus compared with the chin region: a systematic review and meta-analysis focusing on complications and donor site morbidity. J. Oral Maxillofac. Res. 2020, 11, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zumarán, C.C.; Parra, M.V.; Olate, S.A.; Fernández, E.G.; Muñoz, F.T.; Haidar, Z.S. The 3 R’s for Platelet-Rich Fibrin: A “Super” Tri-Dimensional Biomaterial for Contemporary Naturally-Guided Oro-Maxillo-Facial Soft and Hard Tissue Repair, Reconstruction and Regeneration. Materials 2018, 11, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardin, C.; Ricci, S.; Ferroni, L.; Guazzo, R.; Sbricoli, L.; De Benedictis, G.; et al. Decellularization and delipidation protocols of bovine bone and pericardium for bone grafting and guided bone regeneration procedures. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haugen, H.J.; Lyngstadaas, S.P.; Rossi, F.; Perale, G. Bone grafts: which is the ideal biomaterial? J. Clin. Periodontol. 2019, 46, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccirillo, C.; Pullar, R.C.; Costa, E.; Santos-Silva, A.; Pintado, M.M.E.; Castro, P.M.L. Hydroxyapatite-based materials of marine origin: a bioactivity and sintering study. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2015, 51, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesan, J.; Zhong-Ji, Q.; Bomi, R.; Thomas, N.; Kim, S. A comparative study of thermal calcination and an alkaline hydrolysis method in the isolation of hydroxyapatite from Thunnus obesus bone. Biomed. Mater. 2011, 6, 035003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bas, M.; Dagligar, S.; Kalkandelen, C.; Gunduz, O. Use of waste salmon bones as a biomaterial. Proc. IEEE 2020, pp. 1–4.

- VIII Informe de Sustentabilidad 2022. Salmon Chile. Available online: https://www.salmonchile.cl/descargas/VIII_Informe_Sustentabilidad_SalmonChile_2022.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Haberko, K.; Bućko, M.M.; Brzezińska-Miecznik, J.; Haberko, M.; Mozgawa, W.; Panz, T.; et al. Natural hydroxyapatite—its behaviour during heat treatment. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2006, 26, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, F.; Haidar, Z.S.; Puigdollers, A.; Guerra, I.; Padilla, M.C.; Ortega, N.; Balcells, M.; García, M.J. Efficient hydroxyapatite extraction from salmon bone waste: An improved lab-scaled physico-chemico-biological process. Molecules 2024, 29, 4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, F.; Haidar, Z.S.; Puigdollers, A.; Guerra, I.; Padilla, M.C.; Ortega, N.; García, M.J. A novel Chilean salmon fish backbone-based nano-hydroxyapatite functional biomaterial for potential use in bone tissue engineering. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1330482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granito, R.N.; Muniz Renno, A.C.; Yamamura, H.; de Almeida, M.C.; Menin Ruiz, P.L.; Ribeiro, D.A. Hydroxyapatite from fish for bone tissue engineering: a promising approach. Int. J. Mol. Cell Med. 2018, 7, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haidar, Z.S.; Hamdy, R.C.; Tabrizian, M. Biocompatibility and safety of a hybrid core-shell nanoparticulate OP-1 delivery system intramuscularly administered in rats. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 2746–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atik, İ.; Atik, A.; Akarca, G.; Denizkara, A.J. Production of high-mineral content of ayran and kefir – effect of the fishbone powder obtained from garfish (Belone belone). Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2023, 33, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, E.M.; Sayed, M.; El-Kady, A.M.; Elsayed, H.; Naga, S.M. In vitro and in vivo study of naturally derived alginate/hydroxyapatite biocomposite scaffolds. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 165, 1346–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naga, S.M.; Mahmoud, E.M.; El-Maghraby, H.F.; El-Kady, A.M.; Arbid, M.S.; Killinger, A.; Gadow, R. Porous scaffolds based on biogenic poly(ε-caprolactone)/hydroxyapatite composites: in vivo study. Adv. Nat. Sci.: Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2018, 9, 045004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torquato, L.; Suárez, E.; Bernardo, D.; Pinto, I.; Mantovani, L.; Silva, T.; Jardini, M.; Santamaria, M.; De Marco, A. Bone repair assessment of critical-size defects in rats treated with mineralized bovine bone (Bio-Oss®) and photobiomodulation therapy: a histomorphometric and immunohistochemical study. Lasers Med. Sci. 2021, 36, 1515–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.K.; Çimenoğlu, Ç.; Cheam, N.M.J.; Hu, X.; Tay, C.Y. Sustainable aquaculture side-streams derived hybrid biocomposite for bone tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2021, 126, 112104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, Y.; Du, T.; Liu, Y. Biomechanical characteristics and analysis approaches of bone and bone substitute materials. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haidar, Z.S. Current and emerging trends in oro-dental healthcare and cranio-maxillo-facial surgery. J. Oral Health Craniofac. Sci. 2023, 8, 001–006. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).