1. Introduction

Sustainable education plays a crucial role in empowering students to address global challenges, such as climate change and biodiversity loss, through informed decision-making and responsible action. In 2015, the United Nations established 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to promote sustainability and tackle a broad range of social, economic, and environmental issues [

1]. This study focuses on SDG 4 – Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education, SDG 13 – Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts, and SDG 14 – Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development.

Several elements of the UN 2030 Agenda can be advanced through citizen science, including fostering participation, building partnerships, promoting education, encouraging sustainable living, and strengthening global citizenship. Citizen science activities can therefore address sustainability challenges while contributing to the achievement of the SDGs [

2,

3]

Citizen science is a participatory research approach that actively engages members of the public in generating new knowledge or understanding [

4]. Such projects enable non-professional participants to contribute to diverse, often large-scale, research efforts [

5]

Traditionally, citizen science has been especially prevalent in biodiversity monitoring due to its capacity to facilitate large-scale data collection [

6]. It is recognised as a valuable tool for increasing both the quantity and spatial/temporal coverage of data, enabling the establishment of long-term monitoring programmes and supporting research on climate change [

6,

7]. Moreover, these projects engage a variety of stakeholders and serve as a powerful mechanism for promoting sustainable practices.

Citizen science projects vary in terms of the level of public involvement. Three main types of citizen science can be identified: (1) Contributory, where scientists design the research and participants collect data following defined protocols; (2) Collaborative, where participants engage in multiple research activities, such as data analysis and interpretation, while scientists frame the research questions; and (3) Co-created, where participants are involved in all stages of the project, including the formulation of research questions [

7]. To this typology, the category of Extreme Citizen Science has been added, characterised by a bottom-up approach that integrates local needs, traditions, and culture, with scientists acting as both experts and facilitators [

8].

Co-creation projects involve citizens and scientists collaborating at multiple stages of the research process, emphasising mutual learning—citizens contribute local knowledge and perspectives, while scientists provide methodological expertise (5)

This approach fosters deeper engagement, shared ownership, and more inclusive and impactful scientific outcomes. Consequently, co-created citizen science projects often demonstrate the greatest transformative potential and the broadest impacts on public understanding [

9,

10,

11]

In school settings, citizen science offers significant potential for science education [

12,

13]. Its distinctive approach and relevance to sustainable development have led to increasing adoption in educational contexts. However, the educational impact of citizen science varies depending on project design [

14]. A key recommendation is to align learning objectives with citizen science goals during the planning stage, using co-creation approaches to ensure accessibility and inclusivity [

15]. Nevertheless, many projects face constraints such as limited time, scarce resources, and teachers’ lack of confidence in their scientific knowledge [

17].

This study explores the benefits and limitations of a co-creation citizen science approach implemented in schools to monitor species distribution on rocky shores. The following research questions guided the investigation:

What was the impact of the co-creation citizen science project on students’ scientific knowledge and skills development?

How did different stakeholders evaluate the implementation of the co-creation project?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

The participants were 100 students of 4th grade (aged 9 – 10) belonging to 5 classes within 5 elementary schools (3 private schools and 2 public schools) from Lisbon, Faro, and Matosinhos region (Portugal). These schools were selected for their proximity to the coast and because both students and in-service teachers had participated in a collaborative citizen science project on rocky shore species monitoring during the previous academic year.

This project adopted a co-creation approach, involving students, teachers, and researchers in all stages of the research process. It expanded upon a previous citizen science initiative and included the participation of one marine ecology researcher and three in-service teachers [

3]

The first activity aimed to introduce and motivate students for the project. Through role-play, students began designing the citizen science project, defining participants, research questions, and methods. The second activity involved refining the project design, with students discussing and deciding on key elements. Each class presented its conclusions via a Zoom call to a marine researcher, who provided feedback on data collection, target species, and procedures. Teachers’ pedagogical and scientific objectives were also discussed in this session.

The final activity consisted of a field trip to an intertidal zone in Portugal; however, only one class (C2) from Matosinhos was able to participate. During the trip, five student groups explored the rocky platform at low tide, searching for predetermined species. Observations were recorded in the iNaturalist platform—a widely used biodiversity citizen science database [

16]—with at least one adult supervising each group. Submitted observations included photographs, date, geolocation, and, where possible, species identification. Following the researcher’s guidance, students also collected data on the density of mobile species and the percentage cover of sessile species within 20 × 20 cm quadrats.

2.2. Data Collection

To address the research questions, a mixed methodology was applied to combine elements of quantitative and qualitative research, integrating the benefits of both methods to have a better understanding of the research questions and enhance the credibility and reliability of data by comparing different sources, perspectives, or data collection technique [

17,

18,

19]. Data were collected through questionnaires to students (n=100) and in-service teachers (n=3); participant observation of students, in-service teachers and researchers; and the observations inserted by students in the iNaturalist app (n = 21).

The students' questionnaires, were applied to assess the perceptions and evaluation of the students of the co-creation citizen science approach (

Table S1). The questionnaire’s main section included (1) Satisfaction assessment, where participants rate their experiences with specific activities such as participating in and organising projects, working in groups, and learning sessions; (2) Activities feedback, which gathers opinions on specific tasks like project presentations, group discussions, and role-playing ; (3) Agree/Disagree statements, which measure beliefs about the feasibility and benefits of citizen science projects; and (4) Reflections and Learnings, where participants share what they have learned and provide suggestions for structuring future citizen science initiatives. These questionnaires were anonymous, and the students were asked to use a code (i.e. the first and second letter of one of their parents’ names and their birthday number). The Cronbach´s Alpha [

20] estimates the consistency of responses across items in a test or questionnaire, ranging from 0 to 1, with a value closer to 1 indicating high reliability. The students’ questionnaires with 40 items had a Cronbach´s alpha of 0.782.

The in-service teachers were invited to complete an online questionnaire through their email addresses to assess their perceptions about the benefits and limitations of the co-creation approach in a school context (

Table 1).

Moreover, the involvement of students, in-service teachers, and researchers in each activity was analysed through an observation grid during the study with the following categories: (1) Knowledge; (2) Communication; (3) Critical thinking; (4) Collaborative work; (5) Active engagement. The data inserted by students in the platform were analysed according to the following criteria: (1) valid observation (with acceptable photo); (2) correct species identification; (3) image quality; (4) correct use of the scale; (5) other relevant information (in the image) and (6) number of observed taxa.

2.3. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were applied to the questionnaire of students and in-service teachers to portray the relative frequencies of each question and for the data inserted by the students in the platform. To analyse the observation grid, we calculated the frequency distribution of the levels and identified the most frequently occurring level (the mode) as a measure of central tendency (

Table S2). For the field notes, content analysis was applied based on categories that emerged, aiming to support the study results. It was an iterative process of reading and re-reading the data, selecting, coding (data reduction) and displaying it into categories [

21]

3. Results

The findings are presented below in individual sections.

3.1. Impact of the Co-Creation Citizen Science Project on the Scientific Knowledge and Skills Development

Analysis of the observations submitted by class C2 to the iNaturalist platform revealed that students registered 21 valid observations, all accompanied by high-quality photographs. Of these, 95.5% were correctly identified by the students. In total, 13 different taxa were recorded, with the most frequently observed being Sabellaria alveolata (19.0%), Patella sp. (14.2%), Chthamalus sp. (9.5%), Corallina sp. (9.5%), and Mytilus sp. (9.5%).

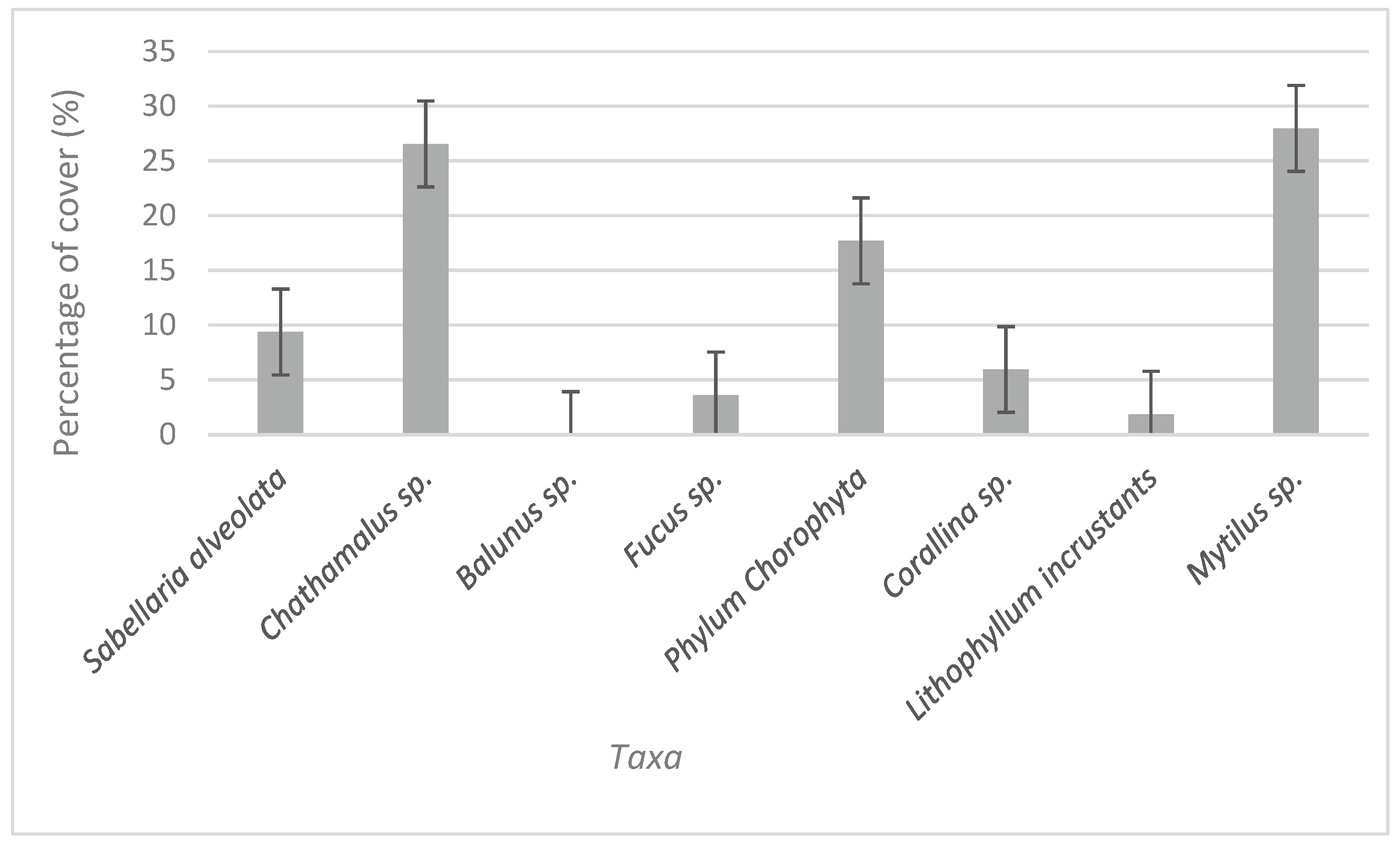

Figure 1 presents the mean percentage cover of sessile species across five sampling areas (20 × 20 cm quadrats).

Chthamalus sp. and

Mytilus sp. exhibited the highest coverage, each reaching approximately 30%. The

Phylum Chlorophyta also showed notable coverage (20%), while

Sabellaria alveolata and

Fucus sp. registered less than 10%.

Field note analysis indicated that most students remembered the presentation delivered by a previous fourth-grade class in the prior school year (Field Notes, R14), demonstrating continuity in learning and sustained engagement. Students exhibited:

“A solid understanding of the issue of climate change and recognition of the relevance of citizen science projects for studying its effects on the rocky intertidal ecosystem. They followed the explanations attentively, grasped the concepts related to the greenhouse effect and carbon dioxide emissions into the atmosphere, and engaged critically when questioned, contributing with thoughtful and pertinent questions. Furthermore, they demonstrated awareness of the primary causes of climate change and its ecological consequences for the intertidal zone. They also understood the concept of citizen science and its importance in monitoring and assessing the impacts of climate change on local biodiversity” (Field Notes, R15).

During activities, students collaborated effectively. Observations noted that “Groups understood the tasks, worked cohesively, and discussed how to structure a citizen science project.” (Field Notes, R16). Each group produced realistic project reports, addressing essential components and identifying relevant stakeholders (Field Notes, R17).

Observation grid results (

Table S2) indicated a good level of content comprehension (mode = 3) and consistent scientific reasoning (mode = 3). Oral communication was generally accurate and scientifically sound (mode = 3–4), with students able to pose relevant questions (mode = 3). Collaborative work was strong, with balanced participation across groups (mode = 4). Engagement levels were high, and students displayed curiosity toward the observed phenomena (mode = 4).

Teacher questionnaires (n = 3) showed that two “strongly agreed” and one “agreed” that the project enhanced students’ scientific knowledge and skill development. All three identified improvements in scientific and technological knowledge, self-growth and autonomy, critical thinking, problem solving, and interpersonal communication. Two teachers highlighted gains in effective oral and written communication, and one mentioned “self-awareness and well-being.”

3.2. Implementation of a Co-Creation Project

Student satisfaction with various aspects of the project (Question 1) was high: 69% reported being “very satisfied” with their overall participation, and 56% reported being “very satisfied” with group work. Nearly half (49%) were “very satisfied” with organising a citizen science project.

Regarding specific activities (Question 2), the climate change and citizen science presentation was the most highly rated, with 66% “very satisfied.” Role-play activities generated strong engagement, with 52% “very satisfied” when researching their character and 43% when writing the character report. Group presentations and discussions were also well received (51% and 48% “very satisfied,” respectively) (

Table 2).

Students’ attitudes toward citizen science (Question 3) were overwhelmingly positive. Most agreed that citizen science should involve collaboration between governance, scientists, and schools, and that participation enhanced their understanding of the intertidal zone (95%). Collaborative work was recognised as essential by 94% of respondents (

Table 3).

For knowledge-related statements (Question 4), 84% agreed that citizen science entails participation in scientific research, 91% identified an appropriate app for species recording, and 85% acknowledged the effects of climate change on marine ecosystems. In Question 4.2, 89% recognized the importance of school–science collaboration in studying climate change, and 91% valued using apps to document species on the beach.

In the open-ended question on project design (Question 5), 35% of students stated they would consult a researcher, 25% would consult their teacher, and 21% would involve the city hall. Practical suggestions included gathering necessary materials (29%) and visiting the beach to record species using a tablet (43%).

Field notes confirmed that students viewed researchers, the school community, and local government as key stakeholders in project design. Teacher responses highlighted implementation constraints, particularly the extensive school curriculum and limited institutional support:

“In addition to a lack of time, due to the extensive programme, there is also insufficient community support, particularly from local authorities, for transport and field trips.” (T1)

Another teacher noted:

“Advantages: the field trip, with direct contact and species identification in the intertidal zone. Limitations: difficulty identifying some species.” (T2)

The teacher also highlighted that the researcher’s involvement throughout the project was essential for both the teacher and the students to understand their roles and stay motivated.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study highlight the strong educational potential of a co-creation citizen science approach in elementary school, particularly for enhancing scientific knowledge and fostering key transversal skills.

The 21 valid observations submitted by class C2 to the iNaturalist platform demonstrated a high degree of accuracy in species identification, indicating that students were able to apply theoretical knowledge in authentic, real-world contexts. The correct identification of taxa such as

Sabellaria alveolata and

Patella sp. suggests that the project effectively reinforced taxonomic knowledge and ecological awareness. Moreover, students’ capacity to quantify species abundance and estimate percentage cover in the field demonstrates the acquisition of procedural and analytical competencies, consistent with previous findings from similar initiatives [

12,

22,

23].

Participant observation and data from the observation grids further confirmed that students could integrate and articulate scientific concepts using appropriate terminology [

15,

23]. Communication skills were strengthened, with students displaying coherent reasoning and constructive interaction during group activities. This supports existing evidence that authentic engagement in the scientific process fosters a sense of ownership, agency, and curiosity [

24].

The observed curiosity and willingness to contribute ideas throughout the project are particularly relevant, as these dispositions are known predictors of sustained interest in science [

4,

14]. The co-creation approach provided opportunities for meaningful participation, enabling students to connect scientific content with their lived experiences.

Regarding project implementation, results indicate that students recognised not only the importance of citizen science but also their ability to participate actively in the design and development of such initiatives. This aligns with Bonney et al.’s [

8] typology, which positions co-created projects as catalysts for deeper engagement and inquiry-based learning. Similar to findings from, higher levels of participation were associated with gains in content knowledge, inquiry skills, and motivation [

14,

25].

Despite these benefits, structural barriers limited the full realisation of the co-creation approach. Teachers cited the overloaded curriculum and insufficient support from local authorities, especially for fieldwork logistics, as significant constraints. These challenges underscore the need for stronger partnerships between schools, researchers, and local institutions to ensure the feasibility and sustainability of educational citizen science projects.

This study also illustrates how co-creation citizen science projects can contribute to multiple SDGs [

1]. By participating in genuine research, students developed scientific literacy and transversal competences aligned with SDG 4 (Quality Education). Monitoring species impacted by climate change addressed the objectives of SDG 13 (Climate Action) and SDG 14 (Life Below Water).

Ultimately, engaging students and the wider school community in authentic research experiences not only supports the acquisition of scientific knowledge but also empowers them to take informed, democratic action in their local contexts. This approach promotes critical thinking, civic responsibility, and a deeper understanding of socio-scientific issues—essential foundations for the development of active, responsible citizens.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the co-creation approach in citizen science projects had significant potential to balance scientific and educational objectives in school settings. By actively involving students in all stages of the research process—from project planning to data collection—the initiative fostered the development of scientific knowledge alongside transversal skills such as critical thinking, collaboration, and communication.

Teachers successfully integrated the project into their teaching practice, although constraints emerged, particularly the demands of an extensive curriculum and the lack of external institutional support. These findings suggest that, for co-creation citizen science projects to be fully effective, schools require sustained backing from local authorities and scientific institutions to overcome logistical and structural barriers.

Engaging students and the broader educational community in authentic research not only promotes scientific literacy but also empowers young people to take meaningful action on sustainability challenges. However, despite its promise, there is still a lack of empirical studies exploring the full potential and limitations of the co-creation approach in education.

Future research should prioritise the long-term implementation of co-creation projects that address educational, scientific, and community needs through an investigative and participatory approach. Establishing long-term monitoring programmes to assess climate change impacts on specific ecosystems within schools demands continuous collaboration across the entire educational community. Early and sustained partnerships between scientists, students, and teachers may also help reduce scepticism regarding the validity of citizen science data.

6. Limitations of the Study

A limitation of this study was that activities were delayed during the COVID-19 pandemic, and only one class could implement the project, which must be considered when interpreting the findings. Additionally, the marine researcher involved in the project did not complete the questionnaire, limiting insights into the researcher’s perspective on the co-creation approach in the school context.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T.N.; D.B. and C.G.; Methodology, A.T.N.; Validation, A.T.N., D.B., and C.G.; Investigation, A.T.N.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, A.T.N.; Writing—Review and Editing, D.B. and C.G.; Supervision, D.B. and C.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) through project UIDP/04292/2020 awarded to MARE and project LA/P/0069/2020 granted to the Associate Laboratory ARNET. Additional support was provided by FCT under the Doctoral Grant SFRH/BD/138527/2018.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was reviewed and approved by the Instituto de Educação, Universidade de Lisboa.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. Consent was also obtained from the legal guardians of minors to participate and to publish any potentially identifiable data or images.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing does not apply to this article.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all participating schools, teachers, and researchers for their collaboration and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization. Education for Sustainable Development Goals. Learning Objectives. United Nations Educational and Cultural Organization; 2017.

- Ferrari, C.A.; Jönsson, M.; Gebrehiwot, S.G.; Chiwona-Karltun, L.; Mark-Herbert, C.; Manuschevich, D.; et al. Citizen science as democratic innovation that renews environmental monitoring and assessment for the sustainable development goals in rural areas. Sustainability. 2021, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, S.; Fonte, C.C.; See, L. The role of Citizen Science in Earth Observation. Vol. 9, Remote Sensing. MDPI AG; 2017.

- Vohland, K.; Land-Zandstra, A.; Ceccaroni, L.; Lemmens, R.; Perelló, J.; Ponti, M.; et al. Editorial: The Science of Citizen Science Evolves. In The Science of Citizen Science; Vohland, K., Land-Zandstra, A., Ceccaroni, L., Lemmens, R., Perelló, J., Ponti, M., et al., Eds.; Springer: Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, E.S.; Perelló, J.; Becker, F.; Bonhoure, I.; Legris, M.; Cigarini, A. Participation and Co-creation in Citizen Science. In The Science of Citizen Science; Vohland, K., Land-Zandstra, A., Ceccaroni, L., Lemmens, R., Perelló, J., Ponti, M., et al., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Pocock, M.J.O.; Tweddle, J.C.; Savage, J.; Robinson, L.D.; Roy, H.E. The diversity and evolution of ecological and environmental citizen science. PLoS One. 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonney, R.; Ballard, H.; Jordan, R.; McCallie, E.; Phillips, T.; Shirk, J.; et al. Public participation in scientific research: Defining the field and assesing its potencial for informal science education. A CAISE inquiry group report. CAISE; 2009.

- Haklay, M. Citizen science and volunteered geographic information: Overview and typology of participation. In Crowdsourcing Geographic Knowledge: Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI) in Theory and Practice; Sui, D. Z., Elwood, S., Goodchild, M.F., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Amesterdam, 2013; pp. 105–122. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, A. Citizen Science. A study of people, expertise and sustainable development; Routledge: London, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Shirk, L.J.; Bonney, R. Scientific impacts and innovations of citizen science. In Citzen science Innovation in open science, society and policy; Hecker, S., Haklay, M., Bowser, A., Makuch, Z., Vogel, J., Bonn, A., Eds.; UCL Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, M.; Rullman, S.; Cousins, J.; Esmail, N.; Begin, E.; Venicx, G.; et al. Contributions to publications and management plans from 7 years of citizen science: Use of a novel evaluation tool on Earthwatch-supported projects. Biol Conserv. 2017, 208, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, S.; Rock, J.; Smith, J. Sediments and seashores - A case study of local citizen science contributing to student learning and environmental citizenship. Front Educ (Lausanne). 2021, 6, 674883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, A.T.; Boaventura, D.; Galvão, C. Contributions from citizen science to climate change education: monitoring species distribution on rocky shores involving elementary students. International Journal of Science Education, Part B [Internet]. 2025, 15, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndt, J.; Nitz, S. Learning in citizen science: The effects of different participation opportunities on students´knowledge and atttitudes. Sustainability. 2023, 15, 12264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, J.; Bell, L.; Galvão, C.; Golumbic, Y.N.; Kloetzer, L.; Knoben, N.; et al. Citizen science, education, and learning: Challenges and opportunities. Frontiers in Sociology. 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boone, M.E.; Basille, M. Using iNaturalist to contribute your nature observations to science. EDIS. 2019, 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, W.J. Research design. Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches; SAGE Publications, Inc: Thousand Oaks, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research; Pearson: New York, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, W.J.; Plano Clark, L.V. Designing and conducting mixed methods research; SAGE Publications, Inc.: London, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering statistics using SPSS; SAGE Publications: London, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, B.M.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook; SAGE Publications, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Boaventura, D.; Neves, A.T.; Santos, J.; Pereira, P.C.; Luís, C.; Monteiro, A.; et al. Promoting ocean literacy in elementary school students through investigation activities and citizen science. Front Mar Sci. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brossard, D.; Lewenstein, B.; Bonney, R. Scientific knowledge and attitude change: The impact of a citizen science project. Int J Sci Educ. 2005, 27, 1099–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Iñesta, E.; Queiruga-Dios, A.M.; García-Costa, D.; Grimaldo, F. Citizen science projects. An opportunity for education in scientific literacy and sustainability. Metode Sci Stud J. 2022, 2022, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Mady, R.P.; Phillips, T.B.; Bonter, D.N.; Quimby, C.; Borland, J.; Eldermire, C.; et al. Engagement in the data collection phase of the scientific process is key for enhancing learning gains. Citiz Sci. 2023, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).