1. Introduction

The call for ocean literacy has become increasingly urgent as the world faces escalating environmental, social, and economic challenges linked to the ocean. This paper traces its roots to the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) project at Hokkaido University of Education, Hakodate, Japan, where the concept of ocean literacy began to emerge between 2019 and 2021. The first published study focused on the diverse marine resources in Northern Iloilo, Philippines—including mangroves, coral reefs, seagrasses, and fisheries—and highlighted their potential integration into instructional materials for science education (Tupas & Matsuura, 2020). Respondents affirmed the relevance of these materials to the Department of Education’s curriculum, underscoring the need to bridge local ecological knowledge with classroom learning.

Despite these advances, several gaps remain. While initial instructional materials enhanced curriculum integration, they lacked immersive and sustainable platforms for long-term community engagement. To address this, the lead proponent introduced the idea of establishing a Marine Ecosystem Museum to serve as a hub for conservation, education, and public awareness. Early feedback revealed strong interest from stakeholders but also emphasized the importance of adopting a digital and technological approach to make the museum more interactive, accessible, and future-ready (Tupas et al., 2023).

Between 2021 and 2022, efforts expanded to incorporate Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) education enriched with the Arts (STEAM) in an integrated school in Carles, Iloilo. These initiatives laid the groundwork for a more holistic educational framework that does not only promote ocean literacy but also strengthens cultural identity and creativity. In 2024, the vision for a marine ecosystem museum took a regional dimension when it was formally organized at the Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organisation–Regional Centre for Education in Science and Mathematics (SEAMEO RECSAM), demonstrating its potential to serve as a model for Southeast Asia.

The novelty of this study lies in its interdisciplinary and transnational approach, which advances education, environmental stewardship, and cultural preservation while being strongly aligned with the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Specifically, it contributes to SDG 4 (Quality Education) by creating inclusive and relevant instructional materials, SDG 13 (Climate Action) and SDG 14 (Life Below Water) by promoting awareness and action for marine ecosystems, and SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) through regional and international collaborations. Equally, it addresses socio-economic dimensions such as SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) by envisioning eco-tourism opportunities, and SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) by strengthening local identity and resilience.

This integrated framework not only fills the gap between curriculum-based materials and community-wide awareness but also pioneers an innovative model of a digital, community-rooted, and globally informed marine museum. Such an approach ensures that ocean literacy is not confined to academic spaces but is extended into society, bridging local realities with global sustainability goals.

This study is anchored in the Blue Carbon Academy Project of the Institute of Technology Sepuluh Nopember (ITS), Surabaya, Indonesia. The initiative underscores the critical role of education and social engagement in promoting sustainable practices and strengthening community impact. By integrating scientific knowledge with social awareness, the project aims to foster greater understanding of blue carbon ecosystems, enhance stewardship, and build long-term strategies that contribute to both environmental sustainability and community resilience.

Thus, this study was formulated. The paper illustrates an approach to enhance marine education through creative outputs across Northern Iloilo State University (NISU) community outreach program to various stakeholders in Northern Iloilo, Philippines.

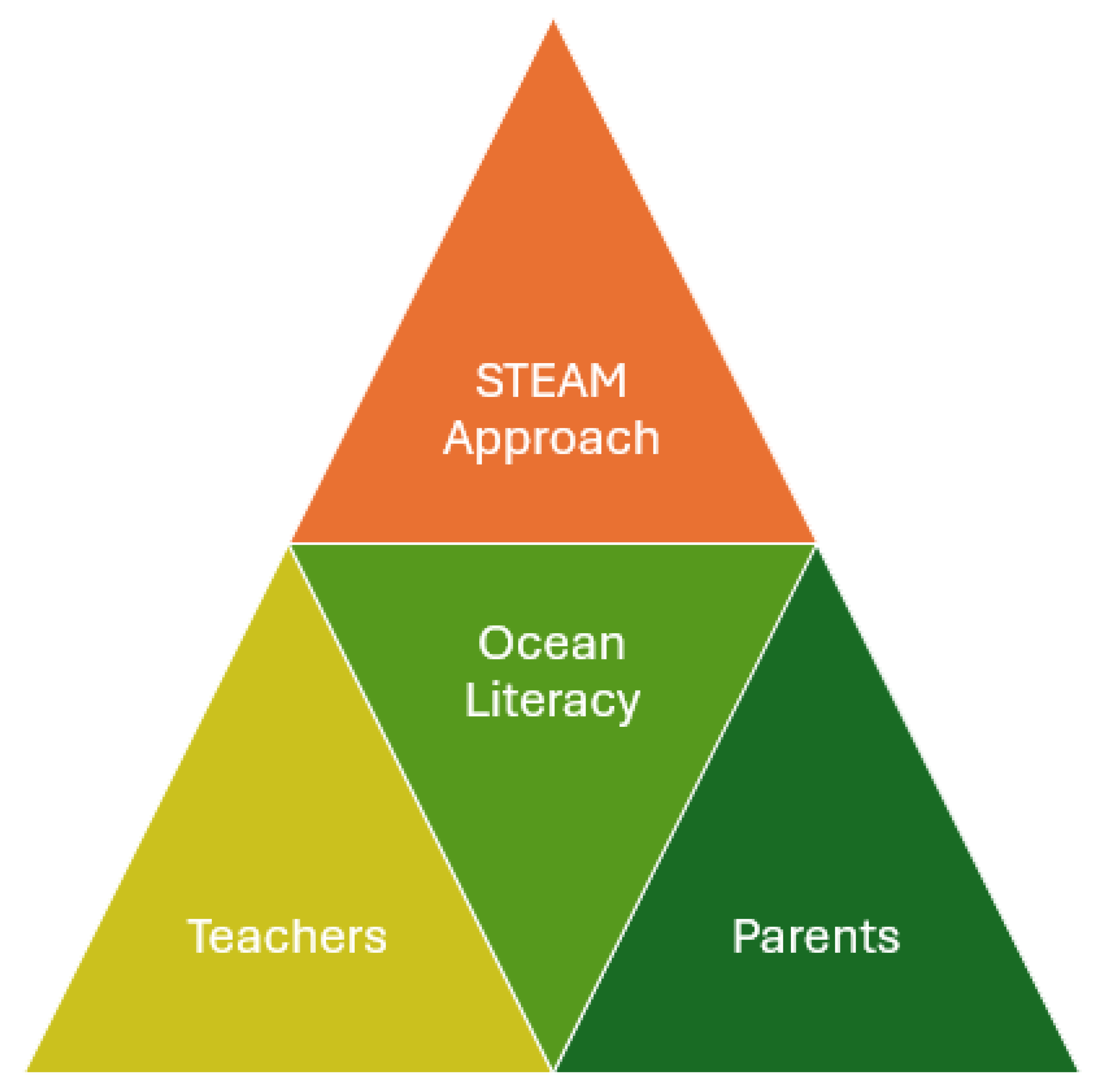

Figure 1 shows conceptual framework of the study.

1.1. Ocean Literacy: Bridging Science, Education, and Community Action

Ocean literacy is broadly defined as an understanding of the ocean’s influence on people, and people’s influence on the ocean. It is not only about knowing scientific facts about marine ecosystems but also about developing the capacity to make informed and responsible decisions regarding the ocean and its resources. An ocean-literate individual recognizes the interconnectedness of the ocean with climate, biodiversity, culture, economy, and human well-being (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)2, (2025).

The idea of ocean literacy moves beyond the traditional classroom approach to science learning. It calls for a holistic framework where education, stewardship, and action are integrated. By understanding that the ocean regulates climate, provides food and livelihoods, sustains biodiversity, and shape’s cultural identity, learners and communities become more aware of the urgency to protect it. At the same time, recognizing human influence on the ocean—such as overfishing, pollution, and coastal development—highlights the responsibility of individuals and societies to mitigate negative impacts and promote sustainability (Tuva, 2024; Kelly et al., 2022).

This dual perspective—the ocean’s influence on us and our influence on the ocean—creates a powerful educational paradigm. It emphasizes reciprocity, accountability, and shared stewardship UNESCO1, 2025). Anchored in the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals, ocean literacy contributes to SDG 4 (Quality Education) through curriculum integration, SDG 13 (Climate Action) and SDG 14 (Life Below Water) by fostering environmental responsibility, and SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) by encouraging international and local collaboration (UN2, 2025).

In practice, advancing ocean literacy involves innovative strategies such as developing localized instructional materials, creating interactive platforms like museums and digital hubs, and embedding marine issues into community-based education. These efforts ensure that ocean literacy is not only an academic pursuit but also a way of life that empowers communities to become custodians of the marine environment (McCauley et al., 2021).Thus, ocean literacy stands as both a knowledge framework and an action agenda—enabling societies to understand, value, and sustain the ocean for present and future generations.

One study about ocean and coastal literacy in Brazil showed it is very uncommon among elementary learners. Extension activities like informal learning revealed that they increase students’ critical thinking as future defenders of our dying ecosystem (Stefanelli-Silva et al., 2019). Just like in the Philippines, marine biodiversity is also vanishing; thus, without any intervention from other sectors like academe, this problem will continue to arise. Northern Iloilo is located along the Visayan Sea, but studies along this marine ecosystem indicated heavy exploitation of aquatic species. The Visayan Sea is the fishing ground and distributor of different fish resources in the Philippines (Bagsit et al., 2021; Bacalso et al., 2023). But this marine biodiversity is in great danger.

1.2. Integrating Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics for Holistic Learning

A recent global forecast reveals that 85% of the professions in 2030 do not yet exist, and many of these are expected to be rooted in STEAM-related fields. This highlights the urgent need for an educational paradigm that not only inspires students to shape the world around them but also equips them with the knowledge and skills to address complex challenges, such as those faced by our oceans (European School Education Platform, 2025).

The STEAM approach—integrating Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics—offers a powerful framework for advancing ocean literacy. Beyond fostering creativity and innovation, STEAM provides personalized and engaging learning experiences that connect scientific knowledge with real-world contexts. By embedding marine issues into interdisciplinary learning, students are encouraged to explore how human actions influence the ocean and how the ocean, in turn, sustains life and communities (Chapell et al., 2025; Spyropoulou & Kameas, 2024).

This study positions STEAM as a vital tool for ocean literacy, enabling educators to design meaningful classroom activities, project-based learning, and ICT-driven simulations that mirror real-world marine and environmental challenges. For instance, students may engage in projects such as designing sustainable coastal communities, creating digital models of coral reef ecosystems, or producing art that communicates the urgency of climate action.

By doing so, learners develop not only academic competence but also essential 21st-century skills—problem-solving, inquiry, collaboration, systems thinking, and creativity. These are the very competencies required to cultivate the next generation of leaders, innovators, and stewards who will safeguard the future of our oceans.

Furthermore, studies on the STEAM approach reveal that it is highly effective in enhancing both cognitive and affective learning, as it not only strengthens students’ critical thinking and problem-solving skills but also fosters motivation, creativity, and positive attitudes toward learning (Kang, 2019).

1.3. Key Stakeholders in Advancing STEAM-Integrated Ocean Literacy

Green Mentors emphasize the importance of enhancing ocean literacy and advancing sustainable practices through both educational and community-based initiatives. Their programs integrate marine conservation topics into school curricula, thereby providing students with early exposure to critical environmental issues. In addition, they conduct community workshops that raise public awareness and encourage local participation in marine stewardship. By collaborating with local and international partners, Green Mentors foster a multi-sectoral approach to ocean education that bridges formal instruction with community engagement. Such initiatives not only deepen the understanding of ocean-related challenges but also empower individuals and groups to take meaningful, actionable steps toward sustainability. This aligns with global calls to promote ocean literacy as a foundation for achieving long-term ecological resilience and meeting relevant Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (UN1, 2025).

A study on the experiences of visitors to coastal areas may focus on collecting information about how exposure to marine and coastal environments influences human health and well-being (McKinley et al., 2023). Furthermore, ocean literacy plays a vital role in shaping human behaviors and practices, fostering greater awareness, responsibility, and action toward achieving ocean sustainability (Shellock et al., 2024). Thus, it is essential to raise awareness and provide knowledge to different stakeholders through activities such as teaching with the STEAM approach in the context of Ocean Literacy, with a strong integration of English, Mathematics, and Science. Such initiatives equip stakeholders with a deeper understanding and empower them to become advocates and protectors of local marine biodiversity. This knowledge and sense of responsibility can then be passed on to future generations, ensuring continuity of stewardship. Incorporating indigenous knowledge into marine education further strengthens this approach. For example, instead of using apples or oranges in teaching basic mathematics, educators may use local marine resources, making learning more contextualized, meaningful, and culturally relevant.

In this study, stakeholders refer specifically to teachers, parents or guardians, and barangay officials. These individuals play a critical role in promoting Ocean Literacy through the implementation of the STEAM approach, serving as key facilitators in fostering awareness, knowledge, and sustainable practices within their communities.

1.4. The Blue Carbon Academy: A Platform for Education and Sustainability

The Blue Carbon Academy is not an entirely new concept, as several countries have already recognized its significance and implemented initiatives tailored to their local contexts. Various nations have developed and adopted their own educational programs, community activities, and research endeavors under the Blue Carbon framework, highlighting its global relevance and adaptability. What makes the concept continually novel, however, is its dynamic application—where each country contextualizes the Academy to address specific ecological, educational, and social needs, thereby creating unique pathways toward ocean sustainability and climate action (Fair Carbon, 2025).

Blue carbon refers to the carbon captured and stored by ocean and coastal ecosystems, including mangrove forests, seagrass meadows, and salt marshes. These ecosystems act as significant carbon sinks, sequestering atmospheric carbon dioxide and mitigating climate change. As such, blue carbon represents a crucial tool in global efforts to combat environmental degradation and promote ecosystem-based climate solutions (Seven Seas Media, Org., 2024). The term ‘Blue Carbon’ was introduced nearly 17 years ago and has since been associated with high-impact initiatives aimed at addressing climate change through the conservation and restoration of coastal and marine ecosystems (Murray et al., 2023). One study suggests that enhancing carbon storage within blue carbon ecosystems—through protection, restoration, and effective management—can significantly influence atmospheric greenhouse gas levels and contribute to climate change mitigation (Howard et al., 2023).

In this study, Blue Carbon refers to the various activities directed at selected stakeholders aimed at protecting marine biodiversity through educational initiatives and social impact programs.

4. Discussion

This initiative highlights the critical role of higher education institutions in advancing community-based learning and promoting ocean literacy. Extension programs, when properly supported by governance and financial structures, serve as a bridge between academic research and grassroots application. The cascading model of instruction reflects best practices in curriculum development, aligning with constructivist theories that emphasize building knowledge from foundational to complex concepts.

Moreover, the focus on marine education resonates strongly with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 4 (Quality Education), SDG 13 (Climate Action), and SDG 14 (Life Below Water). By contextualizing global sustainability issues within local realities, the NISU extension activities not only enhance scientific literacy but also cultivate a sense of stewardship among participants. Such efforts empower communities to recognize their roles in marine conservation and contribute to building resilient coastal societies.

Science education aims to understand the concept of how science works. However, various problems experienced by many science teachers are one of the restrictions of the science curriculum (Valente et al., 2020). Thus, universities, especially those offering teacher education courses, create mechanisms to help the basic education curriculum by extending training and workshops as extension activities and programs. Another study exposed that science teaching is more linked to storytelling. This approach promotes three creative thinking sub-skills (Nasir, Faizal, 2022). Just like storytelling, the art-integrated method has a significant impact on the science curriculum.

Importantly, integrating the concept of Blue Carbon into these extension programs provides an additional layer of environmental and climate relevance. By teaching stakeholders about the role of mangroves, seagrass meadows, and salt marshes in sequestering carbon, participants gain practical knowledge about how local ecosystems contribute to climate change mitigation. This integration not only strengthens marine literacy but also empowers communities to actively participate in preserving biodiversity while addressing global climate challenges.

Figure 2 shows the first extension program on an art-integrated approach to teaching marine education in the Philippines.

With the collaboration of a professional artist, the researchers developed instructional materials that employ an artistic approach to teaching marine biodiversity within the basic education curriculum. This integration of arts and science provides a visually engaging and creative medium through which students can explore complex ecological concepts. Out of the eleven (11) municipalities under study, seven (7) are coastal areas; therefore, instructional topics were deliberately designed to emphasize ocean and coastal biodiversity, ecosystems, and resource management. This contextualization ensures that learning is relevant to the local environment and community livelihoods.

The use of art in instructional design aligns with the STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, Mathematics) framework, which has been shown to enhance both cognitive and affective learning outcomes. By integrating visual and creative elements, students are more likely to retain knowledge, engage with the content emotionally, and develop critical thinking skills. In the context of marine biodiversity education, the artistic approach allows learners to visualize complex ecological interactions—such as coral reef dynamics, mangrove habitats, and fish population networks—in ways that traditional textbooks often cannot convey.

Focusing on coastal municipalities ensures that education is locally relevant and culturally responsive, which is critical for fostering environmental stewardship and sustainable practices. By emphasizing the relationships between communities and their marine resources, students develop a deeper understanding of human impacts on ecosystems and the importance of conservation. This approach also contributes to the development of ocean literacy, empowering learners to make informed decisions and take action toward preserving coastal and marine environments.

In sum, combining art with marine science not only enriches the learning experience but also strengthens the connection between knowledge, creativity, and environmental responsibility, providing a model for effective and engaging ocean literacy education in basic education.

Arts is essential in studying science even though they are opposites. Creativity involves imagination. Imagination is visualization. And they are linked to solving scientific problems. The rule of arts in science is understanding the world and creating a masterpiece. For instance, the Invertebrate Zoology Department of the National Museum of Natural History comprises artistic outputs. The displays are unified with imagination and history. Thus, art helps the beauty of the invertebrates of the oceans (Gamar, 2022). An art-science collaboration has a common cause: to grasp and illustrate the world. The study focused on innovation and was called the “Catching a Wave Case Study.” The purpose is to understand oceans and coasts as an ecosystem where humans interact. The results showed a significant effect on understanding the importance of marine biodiversity (Paterson et al., 2022).

Furthermore, in Structural and Molecular Biology, the arts have the most vital manifestation in learning the two areas due to visual presentation. SciArts plays a crucial role in visualization and understanding the concepts of molecules from size to shape (Goodsell, 2021). In Biology, the arts are always significant, from cells to DNA.

Finally, the integration of the Blue Carbon concept into these instructional activities adds a critical environmental dimension. By teaching participants about the role of mangroves, seagrass meadows, and salt marshes in sequestering carbon, students and stakeholders gain practical knowledge about how local ecosystems contribute to climate change mitigation. This not only reinforces marine biodiversity education but also cultivates a sense of environmental responsibility, empowering communities to actively participate in preserving coastal ecosystems while addressing global climate challenges.

Figure 3 shows the different activities in the selected schools in the 5th District of Iloilo, Philippines.

A series of extension activities and programs were successfully conducted in the adopted schools following the signing of a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) between key officials of Northern Iloilo State University (NISU) and the principals of the partner schools. The implementation of these programs began with action research, emphasizing its growing importance in basic education. Teachers, irrespective of rank or position, were encouraged to actively engage in action research, fostering reflective practice and data-driven decision-making in the classroom.

In June 2025, the College of Education, NISU – Ajuy Campus, Iloilo, Philippines, officially extended these programs to include active participation from parents and guardians. The extension initiatives were implemented in Mangorocoro Elementary School, Adcadarao Integrated School, and Puente Buglas Integrated School within the Municipality of Ajuy. This inclusive approach ensured that learning and community engagement were not limited to students alone but extended to the broader school community, enhancing the overall impact of the programs.

The parents and guardians expressed great enthusiasm and excitement about the integration of the STEAM approach in Ocean Literacy, particularly in the areas of English, Science, and Mathematics. Many shared that this method was new to them, yet they felt empowered by the opportunity to engage in teaching their children using local marine resources. One parent remarked, “This is something new to us, and we are excited to learn how to use our coastal resources to teach our children. It makes learning more meaningful and connected to our community.” Overall, participants highlighted that the approach not only enhances their understanding of marine ecosystems but also gives them practical tools to support their children’s education in a creative and locally relevant way.

The barangay officials expressed their gratitude and delight for being included in the Ocean Literacy activities. They emphasized their appreciation for the opportunity to participate, stating that the programs were both informative and engaging. One official noted, “We are thankful for being chosen to be part of this activity. We are very delighted to learn new ways to support ocean conservation and use this knowledge to benefit our community.” Overall, the officials recognized the value of the initiative in strengthening local environmental stewardship and fostering collaboration between the community and educational institutions.

The results highlight the critical role of institutional collaboration and community involvement in the successful implementation of educational outreach. By integrating action research into extension activities, teachers not only enhance their professional practice but also contribute to improving learning outcomes and school-based interventions. The inclusion of parents and guardians reflects a holistic approach to education, aligning with contemporary models of community-engaged learning and reinforcing the home-school connection.

Moreover, the adoption of these programs across multiple schools underscores the scalability and replicability of the model, demonstrating its potential to enhance STEAM-based and ocean literacy education in coastal communities. Such initiatives are consistent with global educational priorities, including SDG 4 (Quality Education), as they promote innovative teaching practices, community participation, and sustainable learning environments that empower students, teachers, and families alike.

A series of extension activities and programs were conducted in the adopted school upon the memorandum of agreement signed between NISU key officials and the Bancal Integrated School principal. The activities started with action research, which is essential now in basic education. Regardless of rank, teachers are encouraged to conduct action research.

According to the participants, a study about the impact of action research positively influenced teaching and learning methodology. Doing action research helps in professional development and providing curriculum. However, lack of financial support is common (Abrenica and Cascolan, 2022). However, as a researcher, you can conduct action research anytime you want, even without monetary funding. Thus, it is essential to teach in one’s mind that any innovations created and adopted must be tested for effectiveness. Further, one study suggests that problems encountered inside the curriculum could be solved by doing action research (Albani and Johnson, 2022).

Also, aside from motivating teachers, school heads were trained in how to use localization and contextualization in science teaching. The primary purpose of these activities is to boost understanding of localization and contextualization. With all the positive reviews on localization and contextualization, school heads should give one hundred percent support to these practices.

After training the critical officials in cluster 2 of the District of Bangcal, Carles, and Iloilo, science teachers were invited. This time, they were prepared to create instructional materials using local resources focused on marine resources. Many enjoyed the activities, and most became advocates of localization and contextualization. The scarcity of equipment and facilities for science teaching, localization, and contextualization is the key solution to the perennial problems of the Philippine education system.

After all the participants have created instructional materials for science teaching, we plan to display them. The next training was about the Learning Resource Center (LRC). The content of the learning resource center can improve the quality of learning. Thus, academic institutions are inspired to utilize learning resource centers as answers to improve the quality of Learning (Rahmant et al., 2023).

Table 2 shows the participants’ ratings of the different extension activities conducted.

The evaluation of eight (8) extension activities and programs conducted in the districts of Carles and Ajuy yielded an overall rating of excellent. This outcome reflects the high level of effectiveness, relevance, and impact of the initiatives as perceived by the participants and stakeholders.

The excellent evaluation results highlight the significant contribution of university-led extension programs in strengthening community engagement and advancing educational outcomes. In particular, the activities addressed both academic and practical needs, integrating STEAM approaches and ocean literacy themes into local contexts. Such outcomes demonstrate the value of designing programs that are not only academically grounded but also responsive to the realities of coastal communities.

The findings also affirm the importance of participatory approaches in extension work. By actively involving teachers, students, parents, and community members, the programs fostered a sense of ownership and collective responsibility. This aligns with contemporary models of community-based education, which emphasize collaboration between higher education institutions and local stakeholders.

Moreover, the consistently excellent ratings underscore the potential of these extension initiatives to contribute to broader sustainable development goals. Specifically, they support SDG 4 (Quality Education) by enhancing teaching and learning practices, SDG 13 (Climate Action) and SDG 14 (Life Below Water) by promoting awareness of environmental and marine issues, and SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) through multi-sectoral collaboration.

In summary, the evaluation results not only confirm the success of the eight extension activities but also highlight their scalability and replicability as a model for other communities seeking to integrate education, sustainability, and community empowerment.

Higher education conducts extension activities and programs as one of the key thrusts that match instruction and research. Universities and communities should mutually benefit (Magnaye and Ylagan, 2021).