1. Introduction

Citizen science is a field of study where experienced researchers involve community members to collect data for research projects (Hulbert & Scott, 2019) as well as participate in the analysis and reporting on the project results (Scistater, 2025). Public participation in scientific projects via citizen science allows community members to actively engage in resolving community problems and take charge of their environments. Citizen science is, therefore, a movement to democratise science as community members learn about science and how to solve science-related challenges (Heigl, Kieslinger, Paul, Uhlik & Dörler, 2019).

Within the context of developing countries, citizen science aims to foster collaboration by bringing scientists and members of the public together to find solutions to local challenges. Additionally, researchers collaborate with community members in citizen science projects to increase and expand the impact of research. As one of the eight priorities to advance open science (European Commission, 2018), citizen science data plays a role in the advancement of research to strengthen and develop communities. In its nature, open science promotes open and accessible knowledge and emphasises sharing through collaboration (Nurfarawahidah, Kaur & Yanti Idaya Aspura 2023).

Citizen science projects and activities have been widely reported (Weingart and Meyer 2021). To make citizen science activities and projects thrive and achieve maximum impact, support and collaboration from various stakeholders for long-term sustainability are needed. As Ignat, Cavalier &Nickerson (2019) suggest, researchers, libraries, and the public should collaborate to ensure adequate retention of citizen science data. This collaboration is essential as an ongoing dialogue among all stakeholders, including academia-industry collaborations (Sauermann, Vohland, Antoniou, Balázs, Göbel, Karatzas, Mooney, Perelló, Ponti, Samson & Winter, 2020). Academic librarians are crucial to support education, research, and engaged scholarship. Aligned with advancing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations, academic libraries, as key information and knowledge hubs, could provide information, systems, research expertise, and infrastructure to support citizen science activities. Therefore, academic librarians could foster collaboration among stakeholders and promote awareness and advocacy for citizen science activities to fulfil this mission.

Despite the prominent role of academic librarians in research support, the lack of awareness and expertise in citizen science and adequate resourcing of citizen science activities in academic libraries present a significant challenge (Rammutloa, 2023). When failing to address this, academic libraries risk missing an opportunity to demonstrate their value and relevance to society at large. To ensure advanced support and assistance from academic librarians to expand citizen science opportunities and impact on societies, this paper aims to examine opportunities that will foster collaboration between stakeholders towards achieving Sustainable Development Goals outcomes. The study is guided by the objective 'to examine ways in which academic librarians can collaborate to advance citizen science activities.' The research question aims to provide structure in obtaining insight into the research questions:

What platforms are in place that create awareness and encourage citizen science discourse in academic libraries in South Africa?

How could South African academic libraries collaborate to support and promote citizen science?

2. Theoretical Background

The study employed the Knowledge Management framework as a theoretical underpinning, examining collaborative platforms that facilitate awareness creation and stakeholder collaboration. The Knowledge Management framework identifies components such as capture and learn, retain and reuse, enabling technology, and collaboration as important for an effective organisation (Working Knowledge CSP 2025). The first component of capture and learn emphasises that people can acquire and apply knowledge to finish tasks if they participate in learning processes (Working Knowledge CSP 2025). People can further demonstrate understanding at any point in the learning experience. The component on retention and re-using knowledge assets emphasises the point that citizen science data are knowledge assets which should be retained for future use (Working knowledge CSP 2025). Guidelines should therefore be developed to ensure that these knowledge assets are open and accessible in various formats. The third component supports the notion that technology is crucial in citizen science activities as it assists citizen scientists to “connect, collect and collaborate”. The final component highlights the importance of stakeholder collaboration to ensure the sustainability of citizen science activities (Working Knowledge CSP 2025).

3. Literature Review

Academic libraries play a crucial role in supporting citizen science by extending their research data services, as Nurfarawahidah (2023) suggests. These libraries are the core of the universities they serve and have the potential to become hubs for citizen science initiatives. Their existing collaborations and expertise position them as valuable partners in advancing open science practices. In addition, academic libraries offer a unique avenue for fostering partnerships and engagement, particularly among students and researchers, to support and advance outcomes related to SDGs. Their extensive collections provide a wealth of information that is indispensable for research projects in various fields (Day & Pendharkar, 2024).

Traditionally, libraries have formed consortia to facilitate resource sharing and bulk procurement of information resources (Dempsey and Malpas, 2018). However, recent changes in research have shifted the focus to collaborative efforts in research data management and preservation. For instance, the University College London Library leveraged technology by introducing Radio Frequency Identification Devices (RFIDs) to improve service efficiency. They also established open-access initiatives, creating spaces for students and researchers to engage in research-related discussions (Meunier, 2018).

Considering the data-intensive nature of citizen science projects, extensive partnerships are necessary to expand research related to the achievement of SDGs (Moczek, Voigt-Heucke, Mortega, Fabó Cartas & Knobloch, 2021). Collaboration is vital to sharing best practices and learning from each other. As a key component of the information sharing environment, academic librarians can utilise existing relationships to promote citizen science activities, as exemplified by the collaboration between Purdue University, Aalto University Libraries and Council on Library and Information Resources (Rousi, Branch, Kong & Fosmire 2013). The collaboration saw a move towards promoting open geoscience content and how to promote platforms and repositories to citizen science stakeholders in Finnish university libraries. Through platforms like Scistarter and Zooniverse, academic librarians can create spaces to support citizen science projects and activities (Harrington, 2019). For instance, Scistarter hosts more than 3000 registered projects, allowing people to participate actively in science initiatives (Scistarter, 2025).

In addition to hosting information on registered citizen science projects, academic librarians can create 'Libraries as Community Hubs for Citizen Science' initiatives. The partnership between Scistarter, researchers, librarians, citizen scientists, and staff at Arizona State University is an example of such citizen science hubs. The creation of library and community hubs to advance citizen science demonstrates the potential of libraries to support citizen science (Ignat et al., 2019). Outputs from such activities include the publication of librarians’ guides to citizen science aimed at providing insight into incorporating citizen science into library services (Mwaniki, 2018).

Virtual platforms, such as webinars, webcasts, and virtual chat sessions, can also be used to advance citizen science collaborations (Mwaniki, 2018). Additionally, conference attendance and workshops offered by academic libraries or marketed via academic library social media may emphasise continuous professional development necessary to stay abreast of ways in which to optimally use citizen science to advance open access research.

Open access is a critical part of the open science movement advocated by academic libraries, as it allows researchers to use, re-use and disseminate their research. This fundamental role necessitates a shift in academic libraries to accommodate transformations occurring within research and information technology (Rafiq, Batool, Ali & Ullah 2021). The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) recognises that libraries need to modify their services to support open preservation, dissemination and curation of published digital scientific materials (OECD 2015).

The open science movement champions open research, enabling collaborative and knowledge-exchange opportunities among diverse stakeholders such as libraries, IT departments, funders, business and researchers (Ayris & Ignat 2018). One of the critical priorities and emerging success metrics for open science identified by the European Commission (2018) is citizen science. The inclusion of citizen science among these priorities indicates the important role played by citizen science in the domain of open science and research.

4. Methodology

4.1. Materials and Methods

A quantitative research approach and a case study design were used to gather and analyse data and identify patterns, gain useful information, and gain a generalised understanding of how the collaboration of academic librarians and other stakeholders in citizen science could be achieved. The choice of using a quantitative case study design is to provide a holistic view of citizen science in Library and Information Science (LIS), particularly in academic libraries.

4.2. Data Collection Method

A web-based survey design was used to collect quantitative data from one hundred and eighty-five (185) respondents, who are members of the Library and Information Association of South Africa (LIASA). LIASA is a non-profit organisation established to unite and represent all individuals working in different libraries and information services in South Africa (Library and Information Association of South Africa 2025). The targeted respondents were members of the Higher Education Library Interest Group (HELIG), which is affiliated with academic libraries in various capacities. A Census sampling technique was deemed suitable to collect data from the entire population of the LIASA – HELIG members. The small number of respondents in the study informed the reason for collecting data from the entire population of LIASA HELIG members. This aligns with the advice to survey the whole population if it is less than 100 or survey 50% if it is around 500 (Leedy & Ormrod, 2021). The population under study is between 100 and 250, which is acceptable according to the previous statement.

The Microsoft Forms software was used to develop the survey questionnaire. An email link containing the questionnaire and a consent form requesting the respondents' consent and guaranteeing their anonymity should they agree to participate in the study was sent to the respondents.

Primary data from respondents was collected using a self-administered questionnaire with closed and open questions. The reason for using a flexible questionnaire was to ensure that the respondents had a standardised presentation of the citizen science phenomenon and had the opportunity to express themselves without undue influence. The questionnaire was administered for three months, with two reminders sent to ensure that many respondents had the opportunity to participate in the study. Despite the reminders sent, the overall response rate was 34% since only 63 respondents completed the questionnaire. Judging by the population size, the responses cannot be generalised as they are not representative. Although the response rate was low, the researcher maintains that the validity and reliability of the results were not compromised. This assertion is supported by Sataloff & Vonyela (2021), who advance the view that in survey research, there are no clear and acceptable guidelines for response rate. Daikeler, Silbert & Bošjank (2021) also reported that online surveys produced a 12% lower response rate than emails and telephone. It is for these reasons that a low response rate should not prevent assumptions from being drawn from the results (Winter 2000). This study will therefore draw assumptions from the results.

4.3. Data Analysis

Data analysis followed a six-step procedure to prepare, explore, analyse, represent, interpret, and validate the data (Creswell and Plano 2018). The process involved downloading and exporting responses from Microsoft Forms to Microsoft Excel and a statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS) for analysis. Five themes presented in

Figure 1 were discovered from the analysis procedure. This was done to present descriptive statistics from respondents.

Figure 1 is a diagrammatic presentation of the six themes discovered from the quantitative results.

4.4. Results

The study established that collaboration is vital for the success and survival of citizen science in academic libraries; however, the issue of the lead collaborator from the various stakeholders should be clarified. The results are presented below.

4.4.1. Employment Profiles

Questions that required demographic information were not included, as they do not have any significance to the study. However, the employment profiles of the respondents shown in

Table 1 were mandatory, as they provided background information on the different speciality areas, sections, or roles of the respondents. Three sections, Client Services (36.51%), Research (23.81%), and Information Communication Technology (12.75%), were prominent compared to other sections. The employment profiles do not represent respondents' knowledge about citizen science but present a staff concentration in the various sections.

4.4.2. Platforms to Create Awareness of Citizen Science Activities.

During data analysis, the theme of platforms to create awareness of citizen science activities appeared as one of the points to consider. Participants were asked, 'In your view, how could academic librarians create awareness of citizen science activities'? Furthermore, participants were required to choose more than one option. The results are shown in

Table 2.

In response to the question on how awareness of citizen science activities could be created, academic librarians listed options such as having a page on the library website dedicated to citizen science activities (15.2%), a libguide (13.1%), an online discussion forum (12.1%), repositories to deposit (11.8%) and access data (11.1%) as platforms to prioritise. Some platforms, such as social media posts and face-to-face discussions, were also mentioned, but the results indicate that they are less important than the five stated. The results are not amiss, as academic librarians are information providers and are expected to provide infrastructure to make information easily accessible to library users. In their quest to fulfil their obligation to provide information, they could employ platforms such as those stated in

Table 2 (above) to create awareness of citizen science activities.

4.4.3. Collaborating for the Sustainable Service of Citizen Science

In response to a survey question on how academic librarians could collaborate to ensure the sustainability of citizen science activities, 20 responses were collected (

Table 3). The suggestions provided insight into the preferred collaboration methods to sustain citizen science initiatives, and the results presented the following responses.

The results show that academic librarians are in favour of community engagement activities between librarians and community members (5). A community of practice and the formation of a citizen science association (5) are also seen as ideal collaborations for the sustainability of citizen science activities. The academic librarians also listed engaging in discussion forums in workshops and training (4) and forming a citizen science group under LIASA and within universities (4) as preferred means of collaboration. Although Hecker, Haklay, Bowser, Makuch, Vogel, & Bonn (2018) reported on evidence of successful formations of communities of practice, mainly by international citizen science associations, the results of this study reported a contrary view where LIASA, as a community of practice, was the least preferred discussion forum to sustain citizen science activities (see 4.4.4 below). The results further revealed that conferences and funding (2) are not preferred means of collaboration for the sustainable service of citizen science. The result about funding is not surprising, as academic libraries have evolved and have now shifted their services to virtual offerings from bulk buying of physical resources.

4.4.4. Discussion Platforms for the Sustainability of Citizen Science Activities

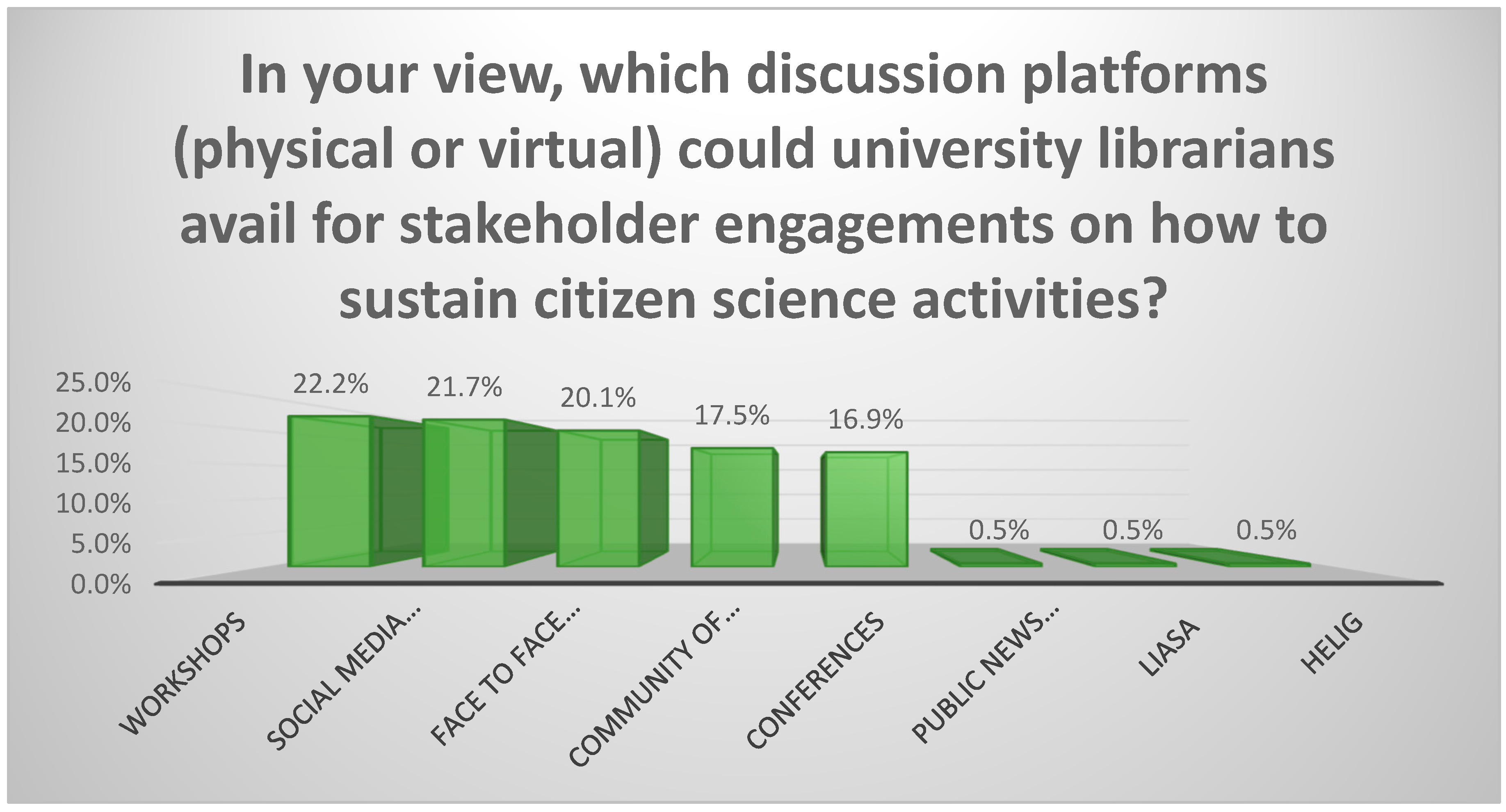

Discussion forums, particularly online platforms, play a crucial role in the success of citizen science by facilitating communication and knowledge sharing among citizen scientists (OECD, 2015). The results in

Figure 2 featured various platforms that are important to encourage discourse on the sustainability of citizen science initiatives. The respondents mentioned workshops (22%), social media pages (21.7%), face-to-face discussion rooms (20.1%), communities of practice (17.5%) and conferences (16.9%) as valuable platforms for collaboration.

These results suggest that workshops, social media pages, face-to-face discussions, and communities of practice are critical to sustaining citizen science activities in academic libraries. Storksdieck, Shirk, Cappadonna, Domroese, Göbel, Haklay, Miler-Rushing, Roetman, Sbrocchi & Vohland (2016) also emphasised that stakeholders are engaged in the success of citizen science in conferences and workshops. These discussion platforms prevent duplication of efforts and foster efficient collaboration. Hecker et al. (2018) reported establishing a community of practice where citizen science practitioners engage in discourse to ensure the sustainability of citizen science projects. Lukyanenko, Wiggins & Rosser (2019) referred to citizen science content as user-generated content suitable for discussion on various platforms, including social media, social networks, blogs, chat rooms, and others.

The following platforms were least preferred by academic librarians as means to sustain citizen science activities: public news publishing (0.5 %), LIASA (Library and Information Association of South Africa) (0.5 %), and HELIG (Higher Education Libraries Interest Group) (0.5 %).

The survey results revealed a contradiction regarding the least preferred discussion forums, namely LIASA (Library and Information Association of South Africa) and HELIG (Higher Education Libraries Interest Group), when discussing citizen science-related content. Lukyanenko et al. (2019) recommended using communities of practice as a foundational platform for discussing citizen science-related content. This recommendation aligns with the notion that these platforms function as communities of practice, where librarians from different sectors engage in discussions about library-related information.

However, it is intriguing that these platforms, well-established as communities of practice for librarians, are less favoured for discussions on citizen science activities among academic libraries in South Africa. The other interesting point is that the respondents are also members of LIASA-HELIG; however, they seem not to trust or favour their community of practice as a discussion platform. The reasons for this discrepancy may be multifaceted and warrant further exploration.

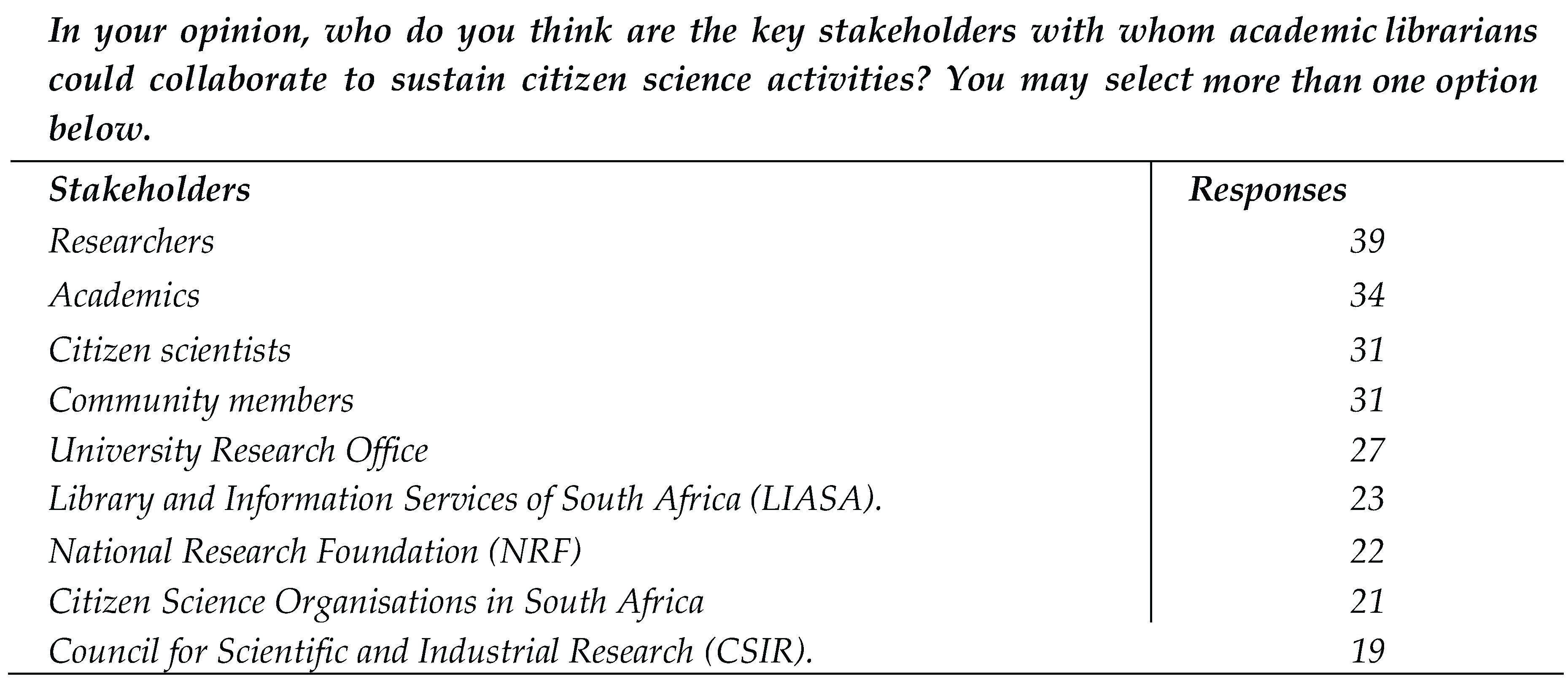

4.4.5. Key Stakeholders to Collaborate in Sustaining Citizen Science Activities.

The establishment of communities of practice assumes an important function in promoting collaboration (Working Knowledge CSP, 2025). In citizen science projects, considerable amounts of data are generated, often necessitating additional resources, including support from academic libraries. Academic libraries have well-established partnerships with various stakeholders, such as students, academic staff members, and community members, which they can leverage to advance citizen science initiatives (Nurfarawahidah, Kaur & Yanti Idaya Aspura 2023).

The recommended partners for collaboration in citizen science activities typically include researchers, libraries, and the public engaged in research, aligning with the insights from (Ignat et al. 2018). Notably, these recommendations reveal the responses of academic librarians, who identified stakeholders they could collaborate with to support citizen science activities. Participants were asked to identify key stakeholders to collaborate with academic librarians. In addition, they were instructed to select more than one option in their responses. The results are presented in

Figure 3.

The apparent preference for academic librarians to work with researchers (39), academics (34), citizen scientists (31), and community members (31) stems from their natural interactions with these groups. Other noteworthy stakeholders are the University Research Office (27), LIASA (23), National Research Foundation (22), Citizen Science Organisations in South Africa (21), and Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (19) are mostly external but have a key role to play in the academic library environment. As a result,

Figure 3 illustrates the importance of focusing on researchers, academics, citizen scientists, and community members as primary collaborators in the sustainability of these activities.

It should be noted that the least preferred stakeholders may be attributed to academic librarians in South Africa, who are still navigating their roles in citizen science and do not fully understand these stakeholders' potential contributions. To ensure the success of citizen science initiatives, consideration, attention, and efforts should be directed toward fostering collaboration with these key groups.

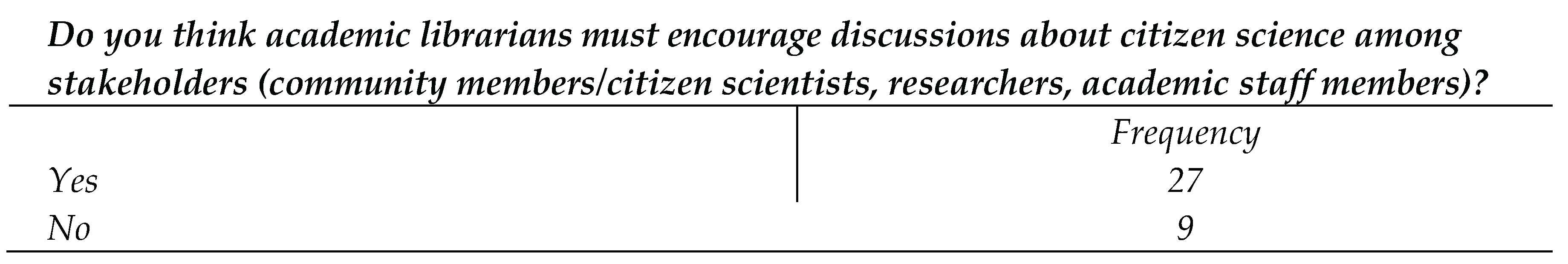

4.4.6. Encouraging Discussions About Citizen Science Among Stakeholders

Collaboration is a well-established practice for academic libraries, which have long been involved in resource sharing through consortia (Malpas, Schonfeld, Stein, Dempsey, & Marcum 2018). According to the knowledge management framework, collaboration consists of two essential components. The first part involves leadership support to encourage collaboration, followed by active participation of practitioners to drive collaborative efforts (Working Knowledge CSP, 2025).

Collaboration among various key stakeholders is crucial to enable the flourishing of citizen science within academic libraries. This includes the Information, Communication, and Technology (ICT) Department, the Research Office, citizen scientists, librarians, and researchers. Academic libraries must act as intermediaries, bridging external citizen science programmes and initiatives with researchers and scientists, as Ayris, de San Roman, Maes, and Labastida (2018) suggested. Engaging in discussions and encouraging discourse on citizen science with relevant stakeholders is necessary for academic librarians (Overgaard & Kaarsted, 2018). The results of this study, as presented in

Figure 4, demonstrate the importance of this involvement. In response to the question, (27) academic librarians agreed that they need to encourage discussions about citizen science, while (9) responded with a "No."

This result highlights the significance of academic librarians in promoting dialogue on citizen science among key stakeholders within academic libraries, including community members/citizen scientists, researchers, and academic staff members. A follow-up question was posed to respondents who supported the idea of encouraging discussions about citizen science. Several key points were highlighted in

Table 4.

Nine academic librarians pointed out the need to raise awareness and enhance understanding of citizen science to ignite discussions. This includes initiatives to educate stakeholders about the concept and its potential benefits. Five respondents advocated for collaborative efforts to stimulate discussions on citizen science. Collaborations could involve partnerships between different stakeholders within academic libraries and beyond. Two responses deviated from the main themes, where an academic librarian believed librarians serve as a platform between stakeholders, acting as intermediaries. Another response mentioned 'data preservation and accessibility', although it was not entirely relevant to the question.

When academic librarians who expressed a lack of interest in encouraging discussions about citizen science were asked to provide reasons for their selection, their responses illuminated barriers and perceptions. As presented in

Table 5, the results revealed that five respondents indicated that academic librarians have shown little evidence of participating in research activities. This perception suggests that academic librarians' limited involvement in research may influence their hesitancy to engage in discussions about citizen science.

Three participants highlighted different key performance areas (KPAs) where academic staff members have a specific KPA for community participation, while library staff do not. This might account for academic librarians’ lack of involvement. One respondent acknowledged that community members often have a deeper understanding of specific topics, potentially making them more qualified subject experts in citizen science. Another participant indicated that subject-specific or discipline-specific scientists are better positioned to promote citizen science, suggesting that they are more competent and better suited due to their specialised knowledge.

These results indicate that academic librarians' lack of involvement in research, differing key performance areas, and perceptions of subject-specific expertise present significant barriers to discussions about citizen science. It is also evident that academic librarians may not view leading and encouraging conversations about citizen science as their primary responsibility. Koltay (2019) emphasise that the role of academic libraries is primarily to support research efforts by providing access to the literature and various services and products. Based on this view, it is therefore not surprising that academic librarians see their contribution in research support and not in conducting the actual research.

5. Discussion

During the analysis, creating awareness of citizen science activities emerged as a recurring theme under the collaboration objective. In particular, the importance of initiating awareness of citizen science activities at the university level is underscored (Ignat et al., 2019). Universities and research institutions are encouraged to play a central role in providing resources and promoting the infrastructure necessary to support citizen science initiatives. Academic libraries, which are integral components of these institutions, are expected to align their mandates with those of their institutions. According to Federer and Qin (2019), academic librarians must have the essential skills and knowledge and the ability to develop awareness services and establish partnerships to create new services.

However, an intriguing contradiction surfaces when examining this focus on creating awareness within the context of citizen science. At the heart of citizen science lies the principle of community outreach, wherein community members actively contribute their time and expertise to citizen science projects (Sauermann al, 2020). In essence, citizen science embodies a form of community outreach, and its success hinges on the active participation of the community. This contradiction highlights the need to balance creating awareness and fostering active community engagement, as these aspects are essential in citizen science. In the pursuit of encouraging awareness, it is crucial not to undermine the core principles of citizen science, which revolve around the invaluable contributions of community members.

6. Conclusions

Citizen science is inherently collaborative, involving multiple stakeholders, such as the community, researchers, and other interested parties, depending on the specific project. International citizen science associations have shown that collaboration is fundamental to establishing a foundation for successful citizen science activities. The study's results also underscore the need for collaboration among citizen science stakeholders. However, there are differing views on who should take the lead in spearheading these collaborative efforts. The study recommends that academic librarians play a central role in initiating and coordinating collaboration among the mentioned stakeholders, including academic librarians, academic staff members, and community members. This recommendation is grounded in the fact that the proposal to position citizen science in academic libraries falls within the purview of academic librarians. Given their involvement in research and data-intensive environments and their existing connections with academic staff members, it is natural for academic librarians to serve as coordinators of citizen science activities.

The study also highlights the importance of using collaboration platforms, virtual or physical, to promote awareness and advocacy of citizen science. To facilitate this, the recommendation is to form a community of practice that includes academic librarians, community members, academic staff, and researchers. This community of practice will serve as a hub for collaborative efforts in citizen science. Furthermore, academic librarians should establish their community of practice to connect with local and international colleagues who have embarked on similar initiatives. This networking will enable benchmarking and the sharing of lessons learnt from peers. In addition to forming partnerships and collaborations, academic librarians should actively engage with local citizen science associations. Staying informed about new citizen science projects and actively participating in these initiatives is essential. This proactive approach will help academic librarians play a pivotal role in the advancement of citizen science within their institutions and the broader community.

References

- Ayris, P; Ignat, T. Defining the role of libraries in the open science landscape: a reflection on current European practice. Open Information Science 2018, 2, 1–22. Available online: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/opis-2018-0001/html?lang=en. [CrossRef]

- Ayris, P; López de San Román, A; Maes, K; Labastida, I. Open Science and its role in universities: a road map for cultural change. In League of European Research Universities (LERU); 2018; Available online: https://www.leru.org/files/LERU-AP24-Open-Science-full-paper.pdf.

- Creswell, JW; Plano Clark, VL. Designing and conducting Mixed methods research (3rd Edition); Thousand Oaks, CA; SAGE, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Day, A; Pendhakar, A. Current connections, future collections: researchers and information professionals working together. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association 2024, 73(3), 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daikeler, J; Silber, H; Bošnjak, M. A meta-analysis of how country-level factors affect Web Survey response rate. International Journal of Market Research 2021, 64(3), 306–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, L; Malpas, C. Gleason, N., Ed.; Academic library futures in a diversified university system. In Higher education in the era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution; Singapore; Palgrave Macmillan, 2018; pp. 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. OSPP-REC: Open Science Policy Platform Recommendations; Brussels; Publications Office of the European Union, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federer, L. Defining data librarianship: a survey of competencies, skills, and training. Journal of medical library Association 2018, 106(3), 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrington, E. Academic libraries and public engagement with science and technology; Cambridge; Chandos Publishing, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hecker, S; Haklay, M; Bowser, A; Makuch, Z; Vogel, J; Bonn, A. Innovation in citizen science: setting the agenda for citizen science. In Citizen Science: innovation in open science, society and policy; London; UCL Press, 2018; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Heigl, F; Kieslinger, B; Paul, KT; Uhlik, J.; Dörler, D. Toward an international definition of citizen science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, 116(17), 8089–8092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulbert, JM; Turner, SC; Scott, SL. Challenges and solutions to establishing and sustaining citizen science projects in South Africa. South African Journal of Science 2019, 115(7/8), 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ignat, T; Cavalier, D; Nickerson, C. Citizen science and libraries: waltzing towards a collaboration. Mitteilungen der VÖB 2019, 72(2), 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koltay, T. Accepted and emerging roles in academic libraries in supporting research 2.0. The journal of academic librarianship 2019, 45(2), 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leedy, P.D; Ormrod, JE. Practical Research: Planning and Design; Pearson Education, Limited; United Kingdom, 2021. [Google Scholar]

-

Library and Information Association of South Africa (LIASA). 2025. Available online: https://www.liasa.org.za/page/about.

- Lukyanenko, R; Wiggins, A; Rosser, HK. Citizen science: an information quality research frontier. Information Systems Frontiers 2019, 22, 961–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malpas, C; Schonfeld, R; Stein, R; Dempsey, L; Marcum, D. University futures, library futures: aligning library strategies with institutional directions; Dublin, OH; OCLC Research, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, B. Library technology and innovation as a force for public good: a case study from UCL Library Services. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on "Emerging Trends and Technologies in Libraries and Information Services "(ETTLIS 2018); IEEE; New York, 2018; pp. 159–165. Available online: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10044764/.

- Moczek, N; Voigt-Heucke; Mortega; Fabó Cartas; Knobloch. A self-assessment of European Citizen science projects on their contribution to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Sustainability 2021, 13(4), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwaniki, PW. Envisioning the future role of librarians: skills, services and information resources. Library Management 2018, 39(1/2), 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurfarawahidah, B; Kaur, K & Yanti Idaya; Aspura, MK. Exploring Citizen science participation and challenges in academic libraries: A comprehensive qualitative study. Pakistan Journal of Information Management and Libraries 2023, 25, 38–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Making open science a reality; Paris; OECD, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overgaard, AK; Kaarsted, T. A New trend in media and library collaboration within citizen science? The case of a Healthier Funen. Liber Quarterly. The Journal of the Association of European libraries 2018, 28(xx-xxl), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, M; Batool, SH; Ali, AF; Ullah, M. University libraries response to COVID-19 pandemic: A developing country perspective. The Journal of Academic Librarianship 2021, 47(1), 102280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammutloa, MW. The missing link: the capacity development for academic librarians to sustain citizen science in university libraries. Library Management 2023, 44(6/7), 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousi, AM; Branch, BD; Kong, N; Fosmire, M. Libraries as advocates of citizen science awareness on emerging open geoscience platforms in Finnish society-international collaboration for promoting open geoscience content in Finnish university libraries. Libraries Faculty and Staff Presentations Paper 66; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Santaloff, RT; Vontela, S. Response rate in survey research. Journal of Voice 2021, 35(5), 683–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauermann, H; Vohland, K; Antoniou, V; Balázs, B; Gȍbel, C; Karaatzas, K; Mooney, P; Perello, J; Pointi, M; Samson, R; Sinter, S. Citizen science and sustainability transitions. Research Policy 2020, 49(5), 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scistater. Citizen science. 2025. Available online: https://scistarter.org/citizen-science.

- Storksdieck, M; Shirk, JL; Cappadonna, JL; Domroese, M; Göbel, C; Haklay, M; Miller-Rushing, AJ; Roetman, O; Sbrocchi, C; Vohland, K. Associations for citizen science: regional knowledge, global collaboration. Citizen Science: Theory and Practice 2016, 1(2), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingart, P; Meyer, C. Citizen science in South Africa: rhetoric and reality. Public Understanding of Science 2021, 30(5), 605–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, G. A Comparative discussion of the notion of validity in qualitative and quantitative research. The qualitative report 2000, 4(3&4), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Working Knowledge CSP Knowledge management framework. 2025. Available online: https://workingknowledge-csp.com/knowledge-management-framework/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).