Submitted:

20 August 2025

Posted:

22 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples Preparation

- a)

-

Control group (samples denoted as CS)- obtained by the conventional sintering, when the heating and cooling was as followed:

- -

- Specimens were heated with a heating rate, ΔT/Δt= 10°C/min up to T = 1550 °C, followed by holding for 2 hours at that temperature, and then cooled for 153 min with a cooling rate 10°C/min to 20°C before removing from the furnace. Total sintering time was 7 h.

- b)

-

Experimental group (samples denoted as SS)- obtained by the speed sintering, were subjected to the followed protocols:

- -

- Specimens were heated with a heating rate 50°C/min up to 1400°C, then with 4°C/min up to temperature 1500 °C, and the last 16 min with 10°C/min up to 1560 °C. The cooling was with a cooling rate 50 °C/min down to 800 °C, dwelling for 5 min, when the specimens were removed from the furnance and left to cool down to room temperature(for approximately 15 min). Total sintering time was 90 min.

- a)

- Polished specimens - underwent dry polishing performed with SagemaxNexxZr Shine Kit-diamond rubber polishers(rubber polishers for pre-polishing and high-gloss polish with diamond paste).

- b)

- Glazed specimens- underwent a transparent aluminosilicate glass deposition on a surface.

2.2. Color Measurements

2.3. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

2.4. Physical Analysis-Contact Angle Measurements

2.5. Biocompatibility Evaluation on Human Gingival Fibroblasts

3. Results

3.1. Optical Properties

3.1.1. Differences in Total Color Change of Speed Sintered Samples

3.1.2. Differences in L* and C* Values

| Layer | ΔE* | ΔL* | ΔC* | ΔH* | Δa* | Δb* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polished | Enamel | 3.013 | 2.453 | 1.621 | -0.659 | 0.444 | 1.692 |

| Transition 1 | 1.643 | 0.511 | 1.544 | -0.227 | 0.095 | 1.558 | |

| Transition 2 | 1.514 | 0.362 | 1.482 | -0.298 | 0.245 | 1.446 | |

| Body | 1.496 | 0.600 | 1.337 | -0.298 | 0.326 | 1.331 | |

| Glazed | Enamel | 2.580 | 1.593 | 1.888 | -0.747 | 0.345 | 2.000 |

| Transition 1 | 1.528 | 0.168 | 1.466 | -0.398 | 0.196 | 1.506 | |

| Transition 2 | 1.925 | -0.247 | 1.683 | -0.488 | 0.263 | 1.832 | |

| Body | 2.196 | -0.925 | 2.256 | -0.274 | 0.244 | 2.259 |

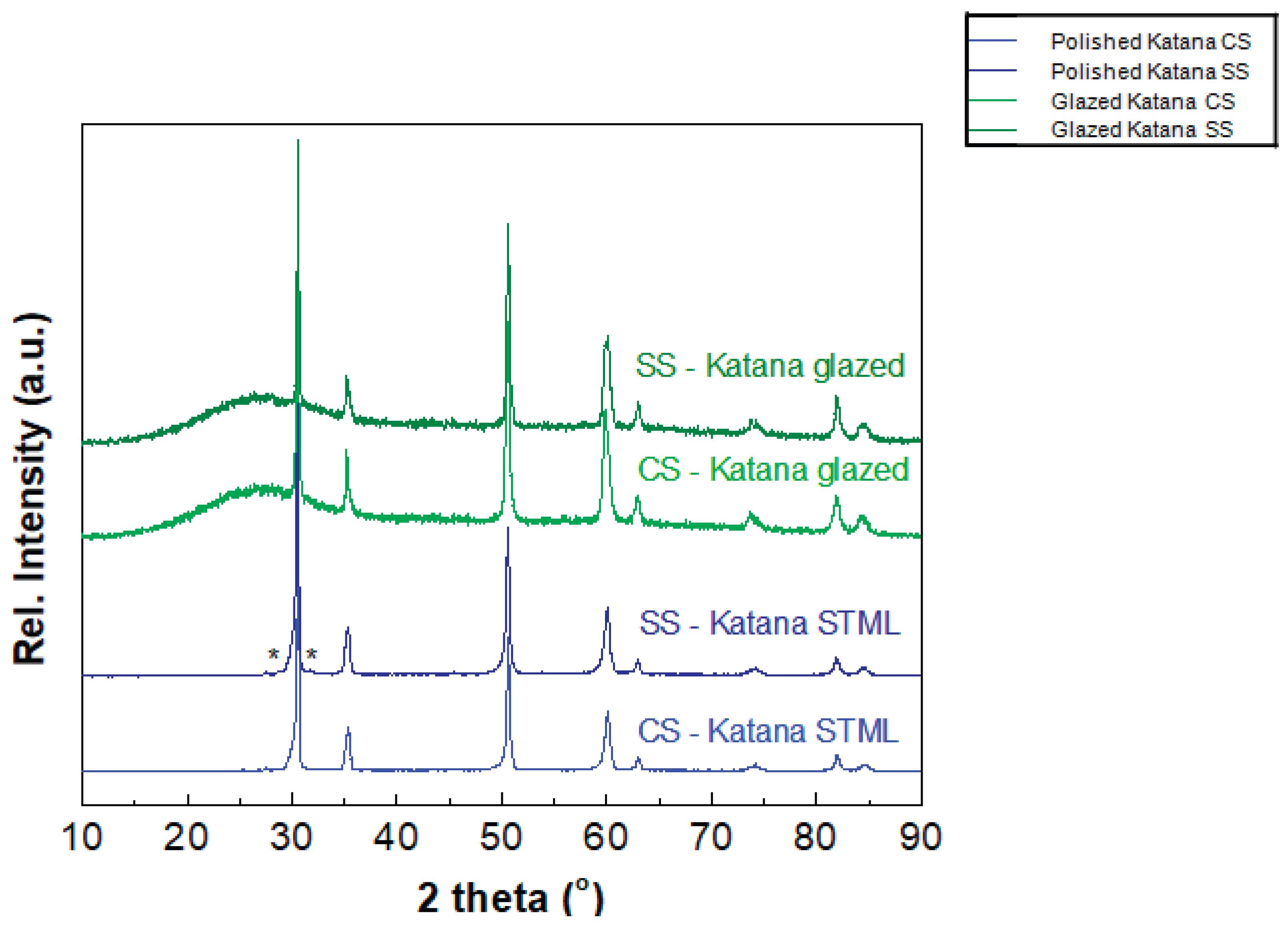

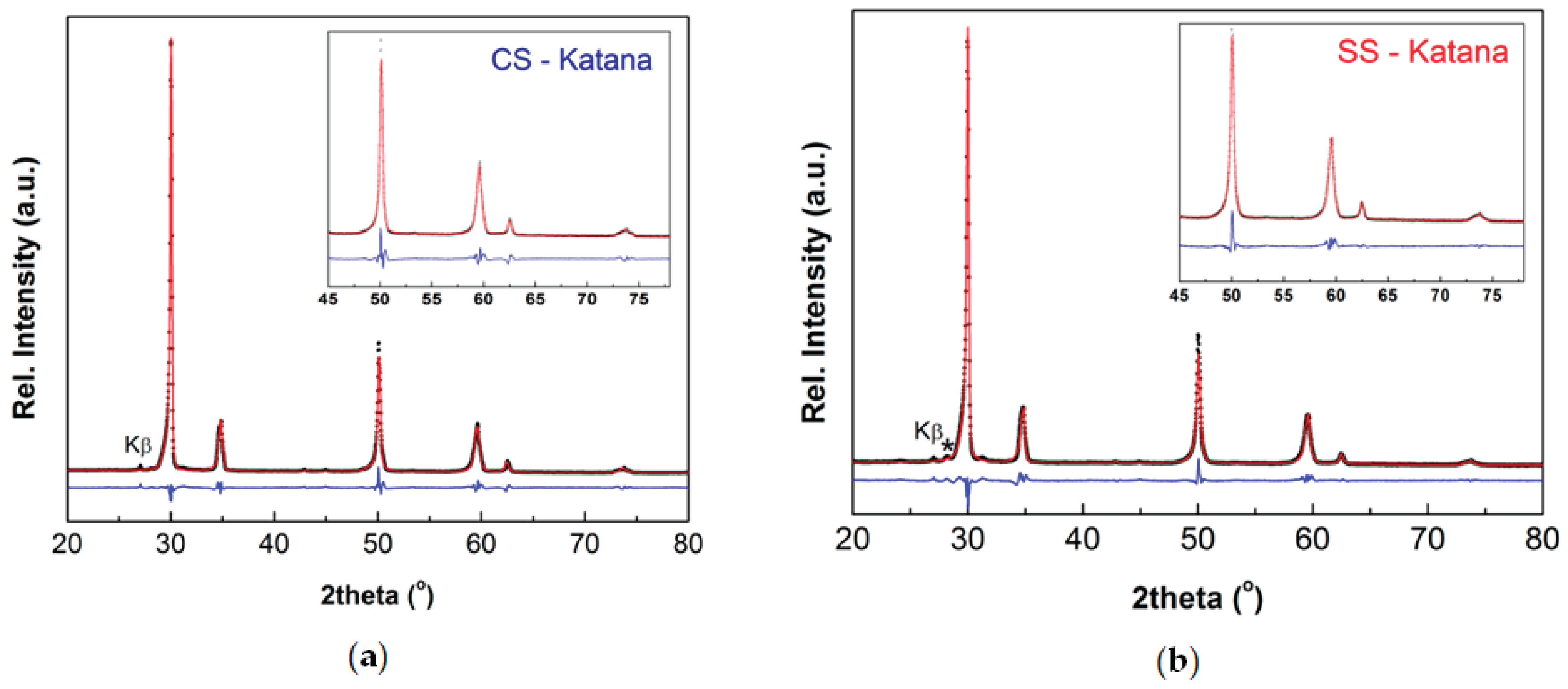

3.2. The Crystal Structure of Sintered Katana STML Samples

3.3. Contact Angle Measurements

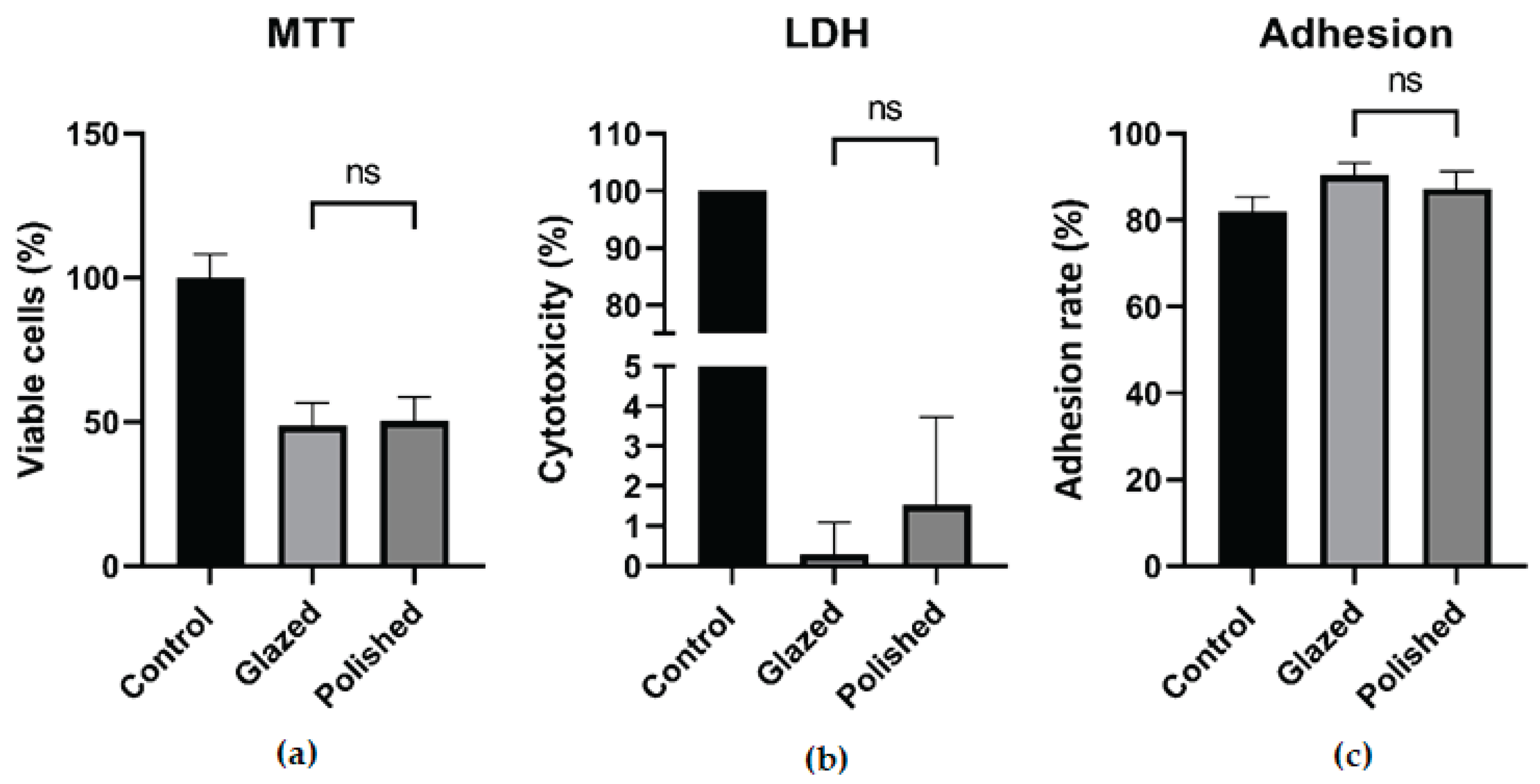

3.4. Comparable Cell Viability and Attachment on Polished and Glazed Zirconia Surfaces

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The sample color measurements in this study showed that the rapid-sintered Katana STML had higher lightness compared to the conventionally sintered sample in the area corresponding to the incisal part of the crown.

- XRD analysis of multichromatic zirconia revealed appearance of the yttria-lean T1-phase with high tetragonality in the speed sintered zirconia samples.

- Glazing as a surface finishing procedure increased hydrophilicity and surface energy values.

- Both polished and glazed zirconia demonstrated comparable cell viability and attachment.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Park, M.-G. Effect of Low-Temperature Degradation Treatment on Hardness, Color, and Translucency of Single Layers of Multilayered Zirconia. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kohorst, P.; Borchers, L.; Strempel, J.; Stiesch, M.; Hassel, T.; Bach, F.-W.; Hübsch, C. Low-Temperature Degradation of Different Zirconia Ceramics for Dental Applications. Acta Biomaterialia 2012, 8, 1213–1220. [CrossRef]

- Manziuc, M.; Gasparik, C.; Negucioiu, M.; Constantiniuc, M.; Alexandru, B.; Vlas, I.; Dudea, D. Optical Properties of Translucent Zirconia: A Review of the Literature. The EuroBiotech Journal 2019, 3, 45–51. [CrossRef]

- Benalcázar Jalkh, E.; Bergamo, E.; Campos, T.; Coelho, P.; Sailer, I.; Yamaguchi, S.; Alves, L.; Witek, L.; Tebcherani, S.; Bonfante, E. A Narrative Review on Polycrystalline Ceramics for Dental Applications and Proposed Update of a Classification System. Materials 2023, 16, 7541. [CrossRef]

- Kolakarnprasert, N.; Kaizer, M.R.; Kim, D.; Zhang, Y. New Multi-Layered Zirconias: Composition, Microstructure and Translucency. Dent Mater 2019, 35, 797–806. [CrossRef]

- Cesar, P.F.; Miranda, R.B. de P.; Santos, K.F.; Scherrer, S.S.; Zhang, Y. Recent Advances in Dental Zirconia: 15 Years of Material and Processing Evolution. Dental Materials 2024, 40, 824–836. [CrossRef]

- Alghazzawi, T.F. The Effect of Extended Aging on the Optical Properties of Different Zirconia Materials. J Prosthodont Res 2017, 61, 305–314. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Making Yttria-Stabilized Tetragonal Zirconia Translucent. Dent Mater 2014, 30, 1195–1203. [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, R.; Angelis, R.D.; Davis, B.H. Factors Influencing the Stability of the Tetragonal Form of Zirconia. Journal of Materials Research 1986, 1, 583–588. [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, R.; Harris, M.B.; Simpson, S.F.; Angelis, R.J.D.; Davis, B.H. Zirconium Oxide Crystal Phase: The Role of the pH and Time to Attain the Final pH for Precipitation of the Hydrous Oxide. Journal of Materials Research 1988, 3, 787–797. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.-L.; Jiang, Y.-Y.; Wei, Y.-R.; Swain, M.V.; Yao, M.-F.; Li, D.-S.; Wei, T.; Jian, Y.-T.; Zhao, K.; Wang, X.-D. The Influence of Yttria Content on the Microstructure, Phase Stability and Mechanical Properties of Dental Zirconia. Ceramics International 2022, 48, 5361–5368. [CrossRef]

- The Royal Society of Chemistry Available online: https://www.rsc.org/ (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Yoshida, M.; Hada, M.; Sakurada, O.; Morita, K. Transparent Tetragonal Zirconia Prepared by Sinter Forging at 950 °C. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 2023, 43, 2051–2056. [CrossRef]

- Xia, X. Computational Modelling Study of Yttria-Stabilized Zirconia.

- Khanlari, K.; Shi, Q.; Li, K.; Hu, K.; Tan, C.; Zhang, W.; Cao, P.; Achouri, I.E.; Liu, X. Fabrication of Ni-Rich 58NiTi and 60NiTi from Elementally Blended Ni and Ti Powders by a Laser Powder Bed Fusion Technique: Their Printing, Homogenization and Densification. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 9495. [CrossRef]

- Daou, E.E. The Zirconia Ceramic: Strengths and Weaknesses. TODENTJ 2014, 8, 33–42. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.M.; Troczynski, T.; McCullagh, A.P.; Wyatt, C.C.L.; Carvalho, R.M. The Influence of Altering Sintering Protocols on the Optical and Mechanical Properties of Zirconia: A Review. J Esthet Restor Dent 2019, 31, 423–430. [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, A.M.; Lim, C.H.; Wolff, M.S.; Janal, M.N.; Zhang, Y. Current Speed Sintering and High-Speed Sintering Protocols Compromise the Translucency but Not Strength of Yttria-Stabilized Zirconia. Dental Materials 2024, 40, 664–673. [CrossRef]

- Kaizer, M.R.; Gierthmuehlen, P.C.; dos Santos, M.B.; Cava, S.S.; Zhang, Y. Speed Sintering Translucent Zirconia for Chairside One-Visit Dental Restorations: Optical, Mechanical, and Wear Characteristics. Ceramics International 2017, 43, 10999–11005. [CrossRef]

- Paravina, R.; Ghinea, R.I.; Herrera, L.; Della Bona, A.; Igiel, C.; Linninger, M.; Sakai, M.; Takahashi, H.; Tashkandi, E.; Pérez Gómez, M. del M. Color Difference Thresholds in Dentistry. Journal of Esthetic and Restorative Dentistry 2015, 27. [CrossRef]

- Rabel, K.; Blankenburg, A.; Steinberg, T.; Kohal, R.J.; Spies, B.C.; Adolfsson, E.; Witkowski, S.; Altmann, B. Gingival Fibroblast Response to (Hybrid) Ceramic Implant Reconstruction Surfaces Is Modulated by Biomaterial Type and Surface Treatment. Dental Materials 2024, 40, 689–699. [CrossRef]

- Chu, S. Color in Dentistry A Clinical Guide to Predictable Esthetics. Stomatology Edu Journal 2018.

- Halder, N.C.; Wagner, C.N.J. Separation of Particle Size and Lattice Strain in Integral Breadth Measurements. Acta Cryst 1966, 20, 312–313. [CrossRef]

- SEC Available online: https://www.stevenabbott.co.uk/abbottapps/SEC/index.html (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Ghinea, R.; Pérez, M.M.; Herrera, L.J.; Rivas, M.J.; Yebra, A.; Paravina, R.D. Color Difference Thresholds in Dental Ceramics. Journal of Dentistry 2010, 38, e57–e64. [CrossRef]

- Ebeid, K.; Wille, S.; Hamdy, A.; Salah, T.; El-Etreby, A.; Kern, M. Effect of Changes in Sintering Parameters on Monolithic Translucent Zirconia. Dent Mater 2014, 30, e419-424. [CrossRef]

- Pekkan, G.; Pekkan, K.; Bayindir, B.Ç.; Özcan, M.; Karasu, B. Factors Affecting the Translucency of Monolithic Zirconia Ceramics: A Review from Materials Science Perspective. Dent Mater J 2020, 39, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-J.; Ahn, J.-S.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, H.-Y.; Kim, W.-C. Effects of the Sintering Conditions of Dental Zirconia Ceramics on the Grain Size and Translucency. J Adv Prosthodont 2013, 5, 161–166. [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, B.; Recen, D. Color Stability and Translucency of Two CAD-CAM Restorative Materials Subjected To Mechanical Polishing, Staining, and Prophylactic Paste Polishing Procedures. EÜ Dişhek Fak Derg 2021, 42, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-K.; Kim, S.-H.; Lee, J.-B.; Han, J.-S.; Yeo, I.-S. Effect of Polishing and Glazing on the Color and Spectral Distribution of Monolithic Zirconia. The Journal of Advanced Prosthodontics 2013, 5, 296. [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.-J.; Lee, Y.-K.; Lim, B.-S.; Kim, C.-W. Effect of Surface Topography on the Color of Dental Porcelain. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine 2003, 14, 405–409. [CrossRef]

- Inokoshi, M.; Shimizu, H.; Nozaki, K.; Takagaki, T.; Yoshihara, K.; Nagaoka, N.; Zhang, F.; Vleugels, J.; Van Meerbeek, B.; Minakuchi, S. Crystallographic and Morphological Analysis of Sandblasted Highly Translucent Dental Zirconia. Dental Materials 2018, 34, 508–518. [CrossRef]

- Itoh, T.; Mori, M.; Inukai, M.; Nitani, H.; Yamamoto, T.; Miyanaga, T.; Igawa, N.; Kitamura, N.; Ishida, N.; Idemoto, Y. Effect of Annealing on Crystal and Local Structures of Doped Zirconia Using Experimental and Computational Methods. Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2015, 119, 8447–8458. [CrossRef]

- Belli, R.; Hurle, K.; Schürrlein, J.; Petschelt, A.; Werbach, K.; Peterlik, H.; Rabe, T.; Mieller, B.; Lohbauer, U. Relationships between Fracture Toughness, Y2O3 Fraction and Phases Content in Modern Dental Yttria-Doped Zirconias. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 2021, 41, 7771–7782. [CrossRef]

- Mayinger, F.; Ender, A.; Strickstrock, M.; Elsayed, A.; Nassary Zadeh, P.; Zimmermann, M.; Stawarczyk, B. Impact of the Sintering Parameters on the Grain Size, Crystal Phases, Translucency, Biaxial Flexural Strength, and Fracture Load of Zirconia Materials. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials 2024, 155, 106580. [CrossRef]

- Scott, H.G. Phase Relationships in the Yttria-Rich Part of the Yttria-Zirconia System. J Mater Sci 1977, 12, 311–316. [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, J.; Gremillard, L.; Virkar, A.V.; Clarke, D.R. The Tetragonal-Monoclinic Transformation in Zirconia: Lessons Learned and Future Trends. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 2009, 92, 1901–1920. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Inokoshi, M.; Nozaki, K.; Shimizubata, M.; Nakai, H.; Cho Too, T.D.; Minakuchi, S. Influence of High-Speed Sintering Protocols on Translucency, Mechanical Properties, Microstructure, Crystallography, and Low-Temperature Degradation of Highly Translucent Zirconia. Dental Materials 2022, 38, 451–468. [CrossRef]

- Qualitative X-ray Diffraction Analysis of Metastable Tetragonal (T′) Zirconia - Gibson - 2001 - Journal of the American Ceramic Society - Wiley Online Library Available online: https://ceramics.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1151-2916.2001.tb00708.x (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Yamashita, I.; Tsukuma, K. Phase Separation and Hydrothermal Degradation of 3 Mol% Y2O3-ZrO2 Ceramics. J. Ceram. Soc. Japan 2005, 113, 530–533. [CrossRef]

- Alves, L.M.M.; Contreras, L.P.C.; Bueno, M.G.; Campos, T.M.B.; Bresciani, E.; Valera, M.C.; Melo, R.M. de The Wear Performance of Glazed and Polished Full Contour Zirconia. Braz. Dent. J. 2019, 30, 511–518. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-S.; Shin ,Seung-Yun; Moon ,Seung-Kyun; and Yang, S.-M. Surface Properties Correlated with the Human Gingival Fibroblasts Attachment on Various Materials for Implant Abutments: A Multiple Regression Analysis. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica 2015, 73, 38–47. [CrossRef]

- Rutkunas, V.; Bukelskiene, V.; Sabaliauskas, V.; Balciunas, E.; Malinauskas, M.; Baltriukiene, D. Assessment of Human Gingival Fibroblast Interaction with Dental Implant Abutment Materials. J Mater Sci: Mater Med 2015, 26, 169. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Lee, S.J.; Khang, G.; Lee, H.B. The Effect of Fluid Shear Stress on Endothelial Cell Adhesiveness to Polymer Surfaces with Wettability Gradient. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2000, 230, 84–90. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Khang, G.; Lee, Y.M.; Lee, H.B. The Effect of Surface Wettability on Induction and Growth of Neurites from the PC-12 Cell on a Polymer Surface. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2003, 259, 228–235. [CrossRef]

- Mordanov, O.; Khabadze, Z.; Meremkulov, R.; Saeidyan, S.; Golovina, V.; Kozlova, Z.; Fokina, S.; Kostinskaya, M.; Eliseeva, T. EFFECT OF SURFACE TREATMENT PROTOCOLS OF ZIRCONIUM DIOXIDE MULTILAYER RESTORATIONS ON FUNCTIONAL PROPERTIES OF THE HUMAN ORAL MUCOSA STROMAL CELLS. Georgian Med News 2023, 172–177.

| The heating rate (°C/min) | Phase | Lattice parameters (Å) |

Phase fraction (wt.%) |

Tetragonality, a |

Crystallite size, DXRD (nm) |

Lattice strain, ε (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS-Katana | 10 | Tetragonal (S.G. P42/nmc) |

a= b = 3.633(7) c = 5.124(8) |

54(8) | 0.997 | 17 ± 2 | 0 |

| Cubic (S.G. Fm-3m) |

a = b = c = 5.137(7) | 46(8) | |||||

| SS-Katana | 50 | Tetragonal (T) |

a= b = 3.627(7) c = 5.157(8) |

49(3) | 1.005 | 19 ± 2 | 0.2(2) |

| Tetragonal (T1) |

a= b = 3.615(7) c = 5.168(8) |

27(2) | 1.011 | ||||

| Cubic (C) | a = b = c = 5.189(9) | 24(4) |

| Liquid | Sample | |

|---|---|---|

| Polished | Glazed | |

| Water | 45.12±12 | 32.26±1.80 |

| Ethylene glycol | 50.06±3.12 | 28.06±1.45 |

| Diiodmethane | 42.55±1.98 | 35.50±2.20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).