Submitted:

20 August 2025

Posted:

22 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. ML an Overview

2.1. Terminology and Learning Paradigms

2.2. Supervised, Semi-Supervised, Unsupervised, and RL Tasks

2.2.1. Supervised Learning

2.2.2. Semi-Supervised Learning

2.2.3. Unsupervised Learning

2.2.4. RL

2.3. Learning Models

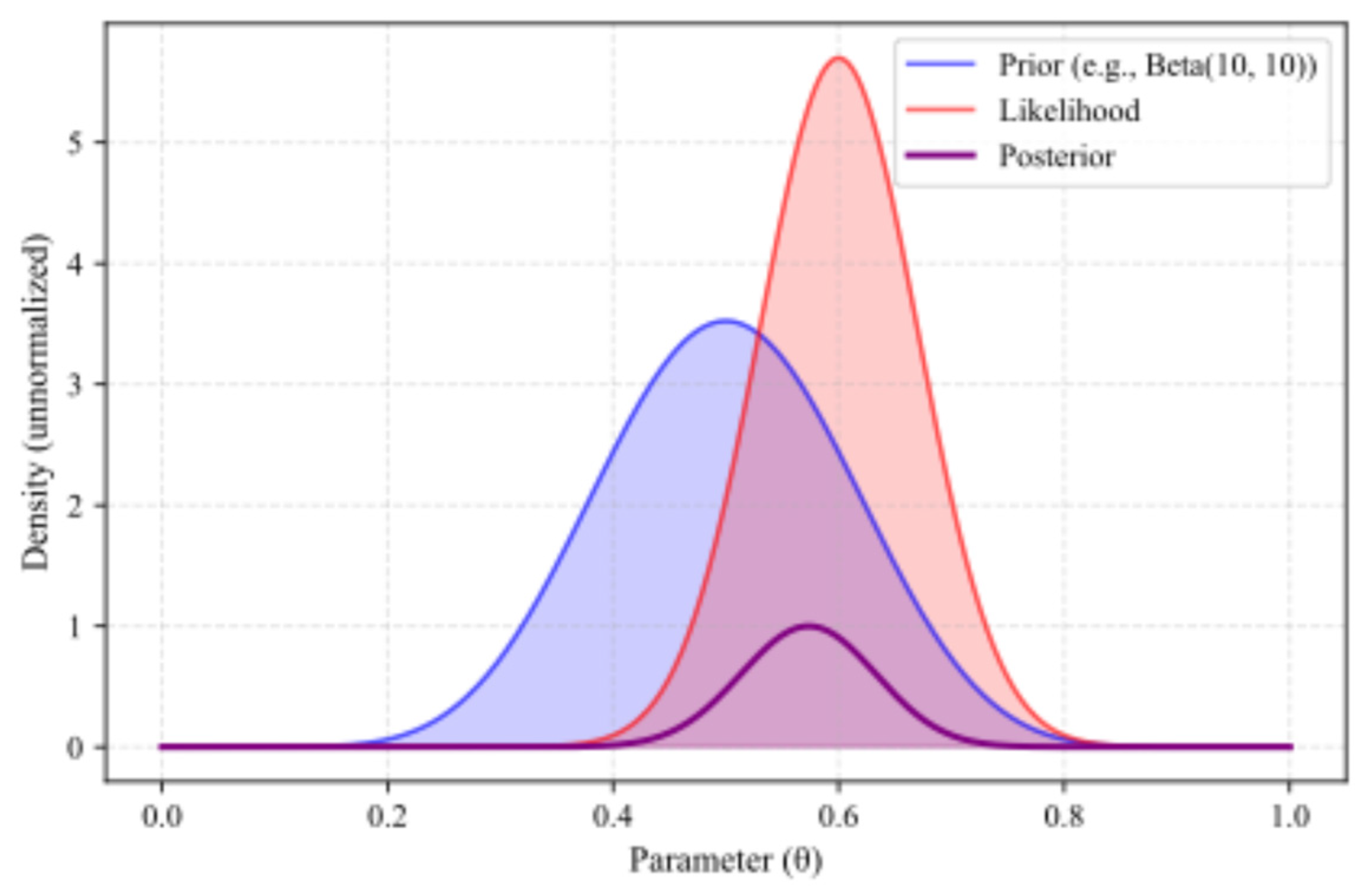

2.3.1. Bayesian Models

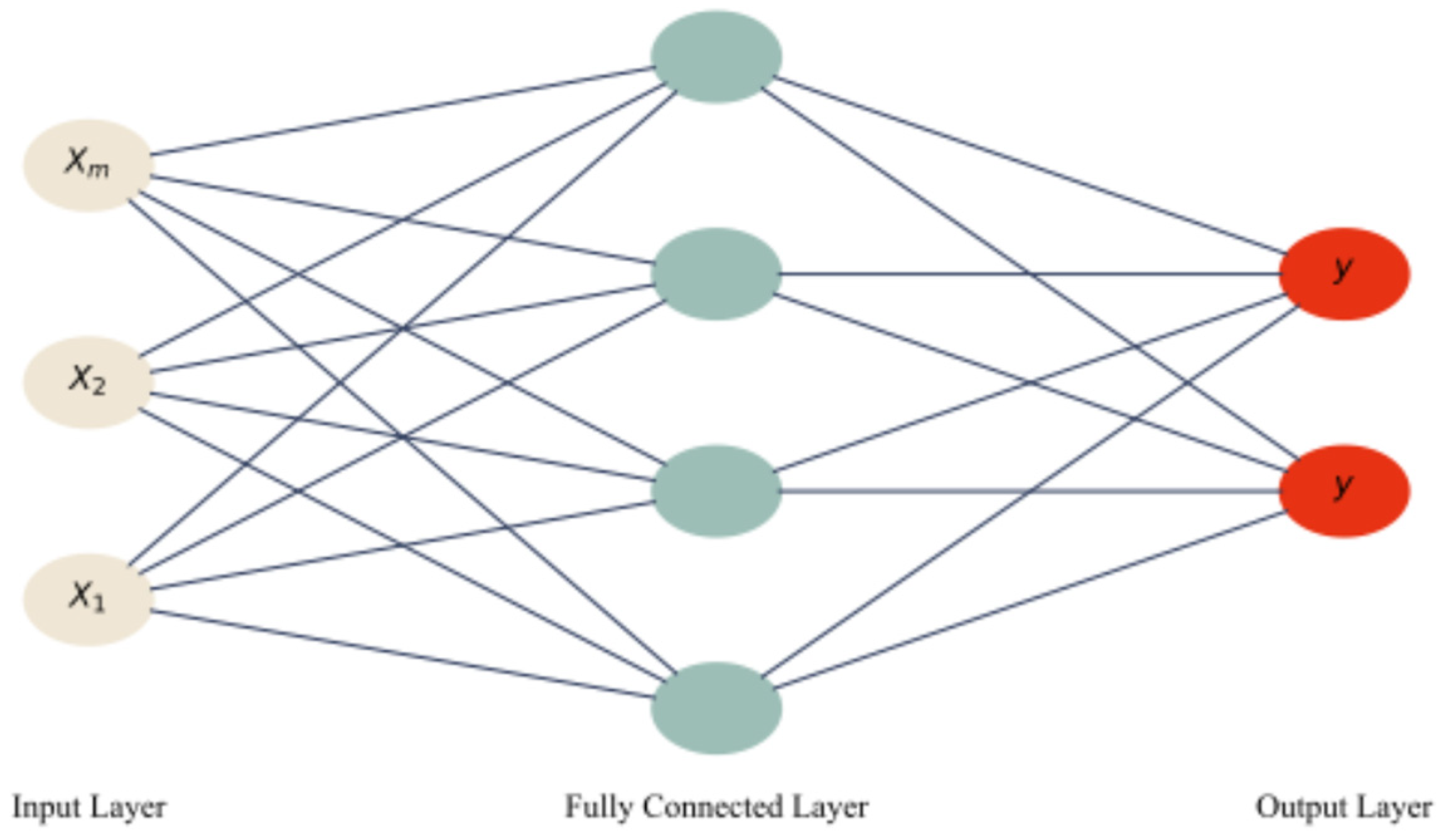

2.3.2. ANNs

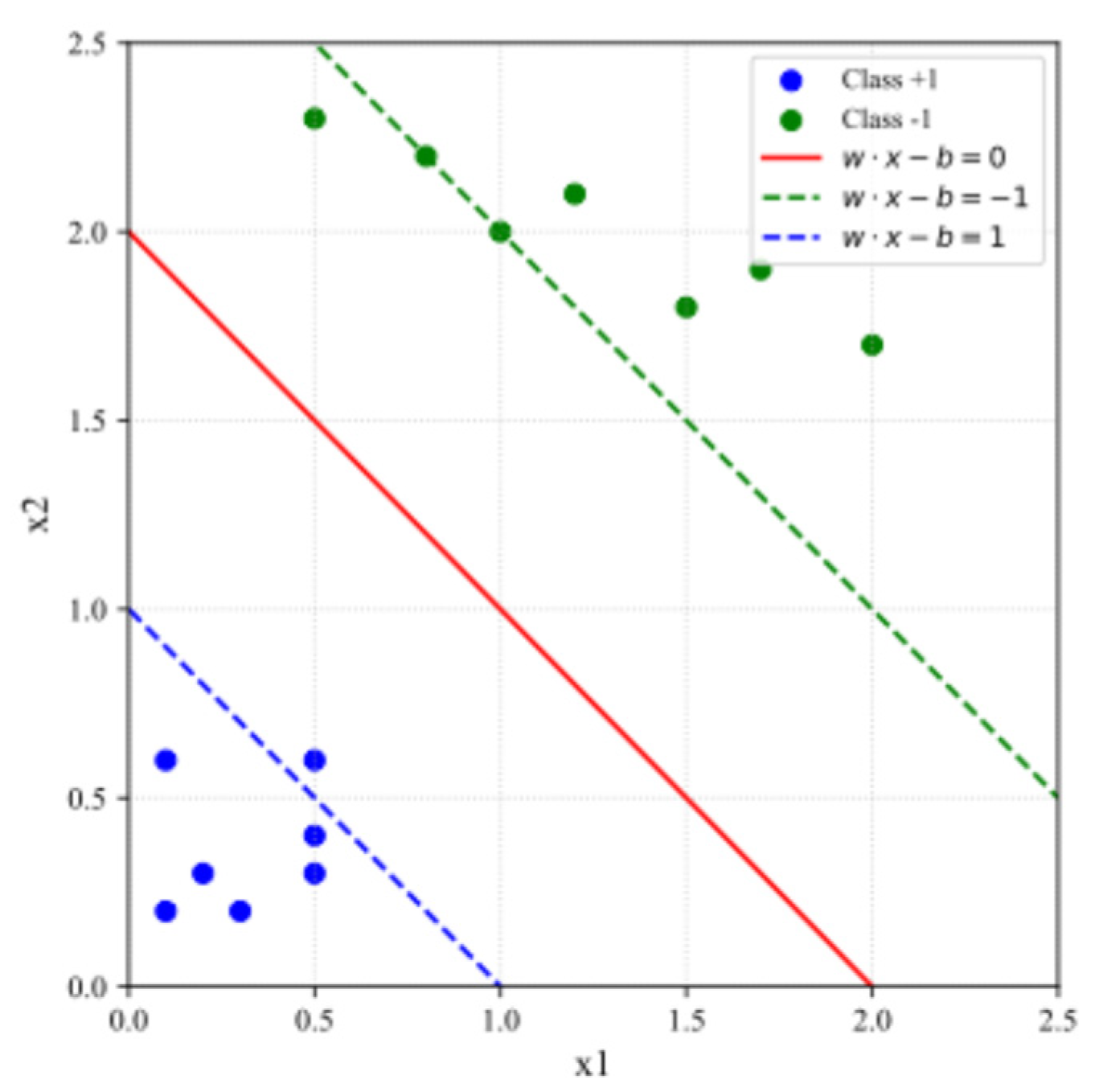

2.3.3. SVMs

2.3.4. Linear and Logistic Regression

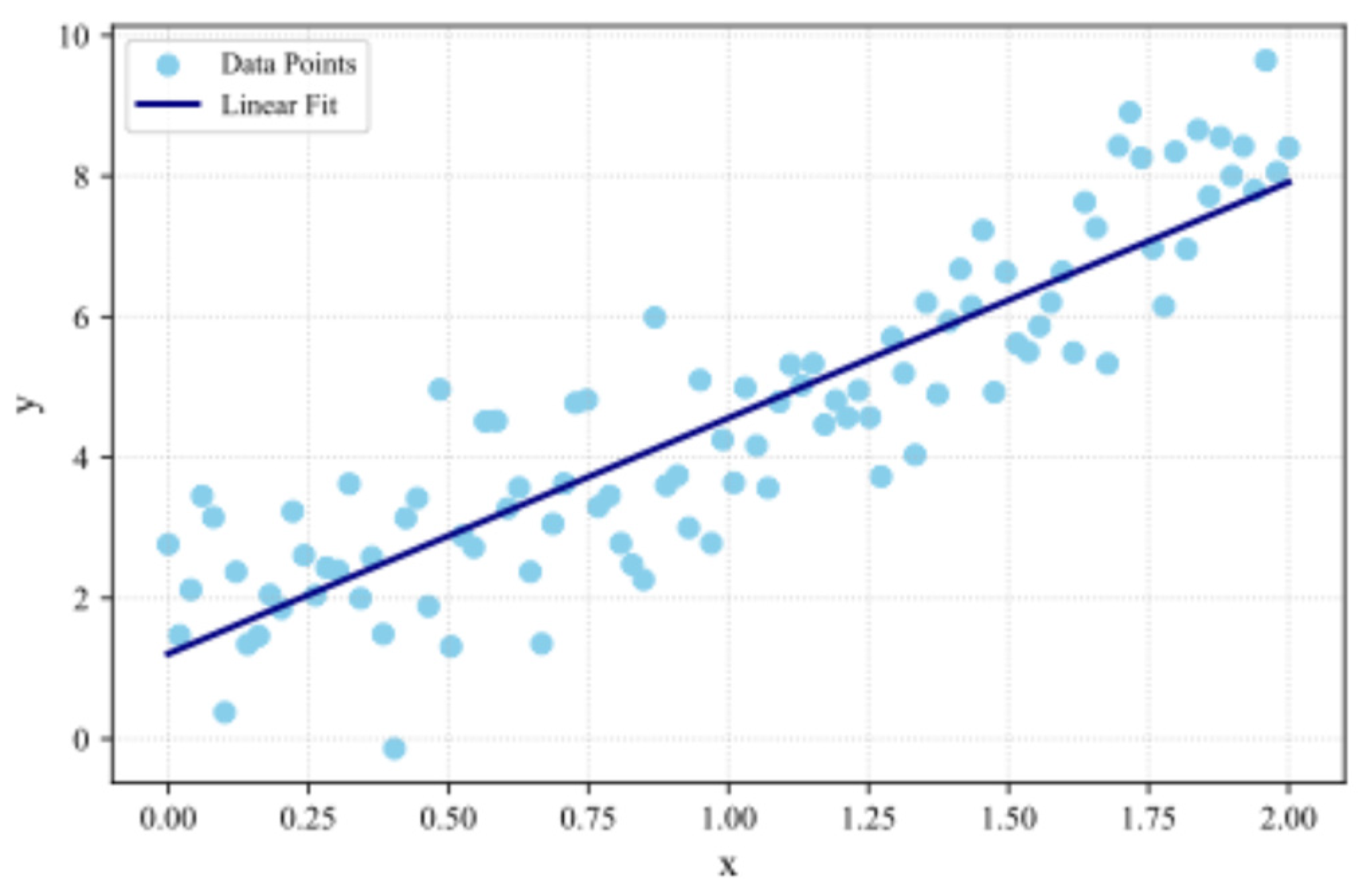

2.3.4.1. Linear Regression

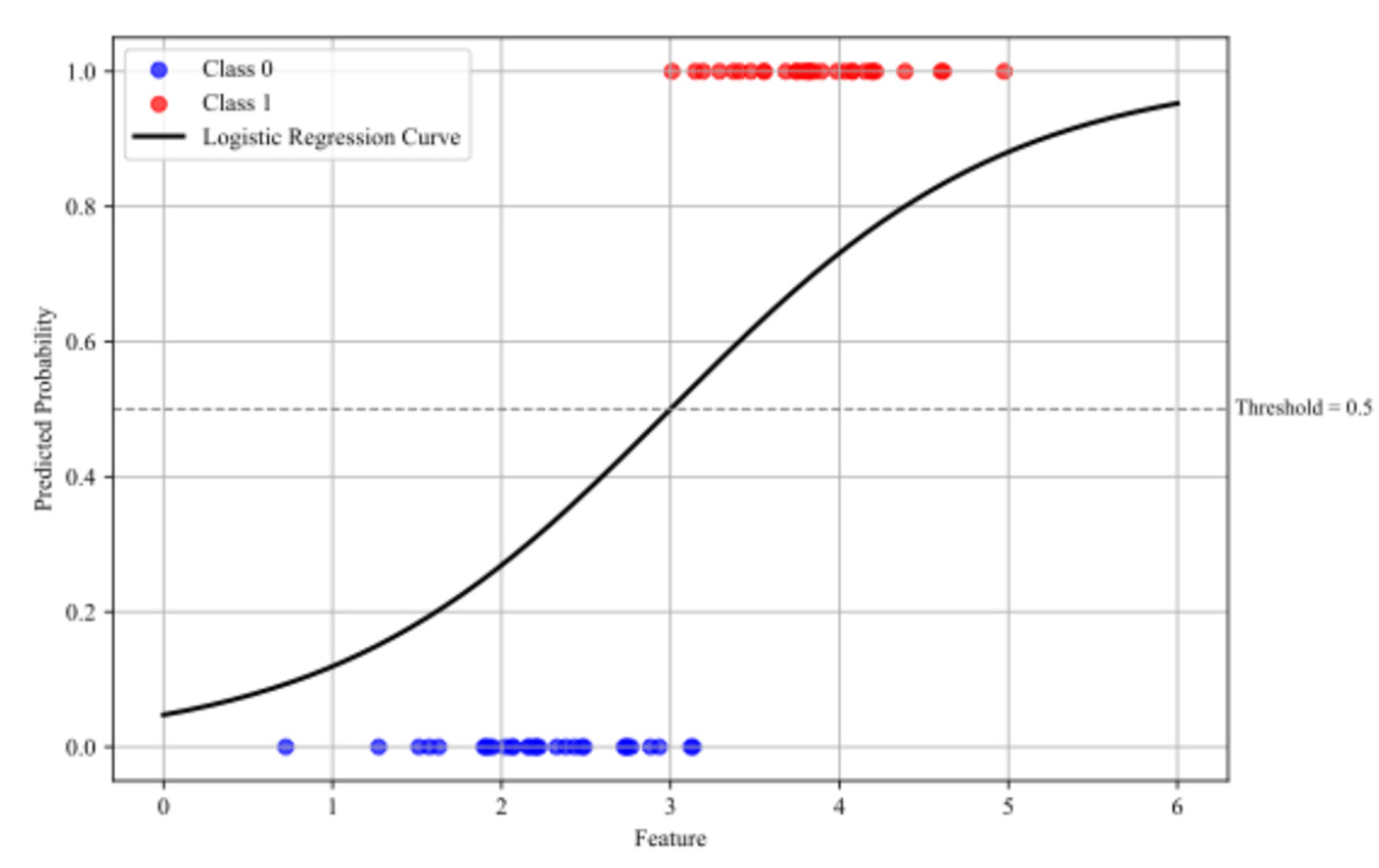

2.3.4.2. Logistic Regression

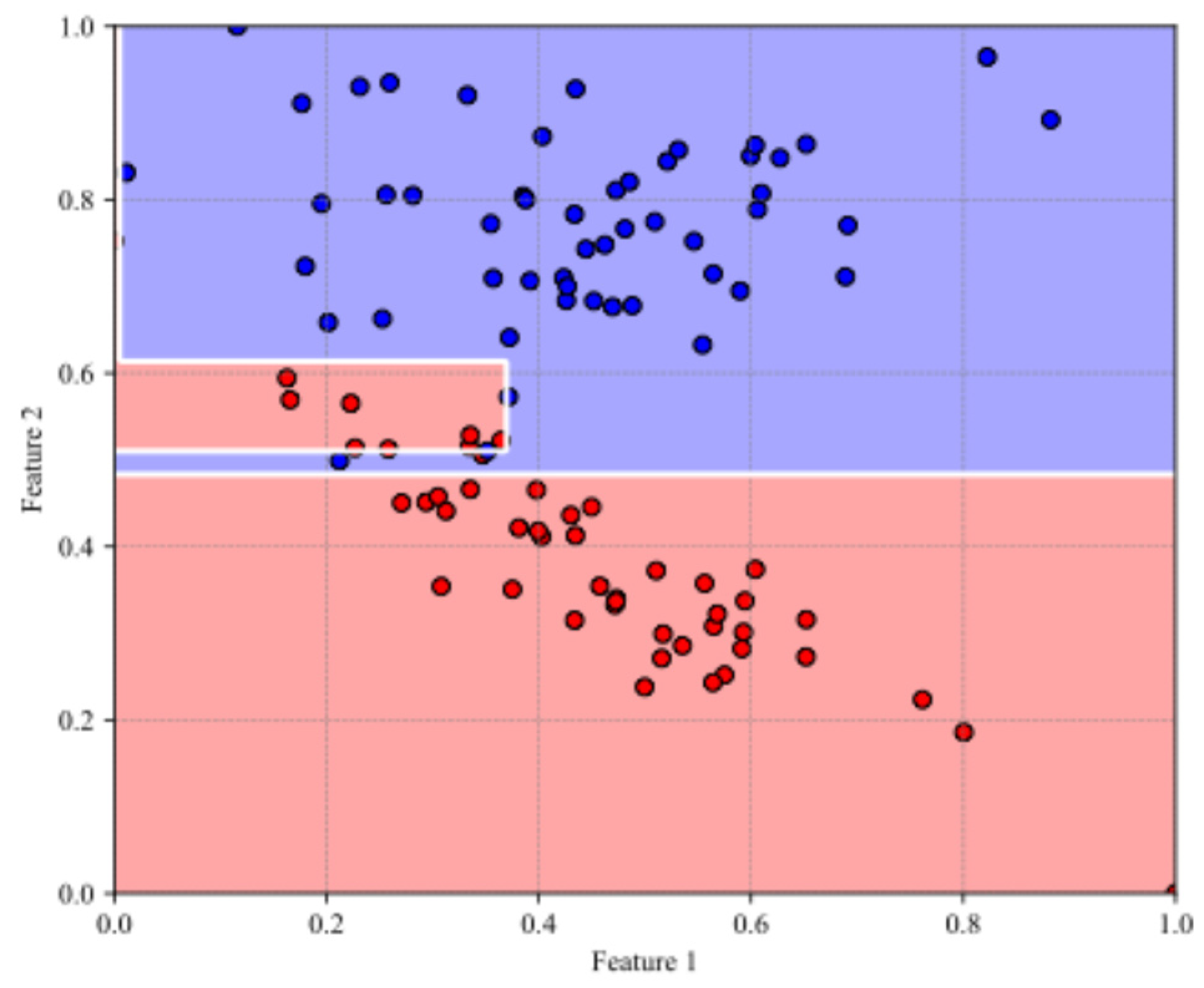

2.3.5. Decision Trees

2.4. Evaluation Metrics

2.4.1. Classification Metrics

2.4.2. Regression Metrics

3. Review for Analog Design Based on ML Methods

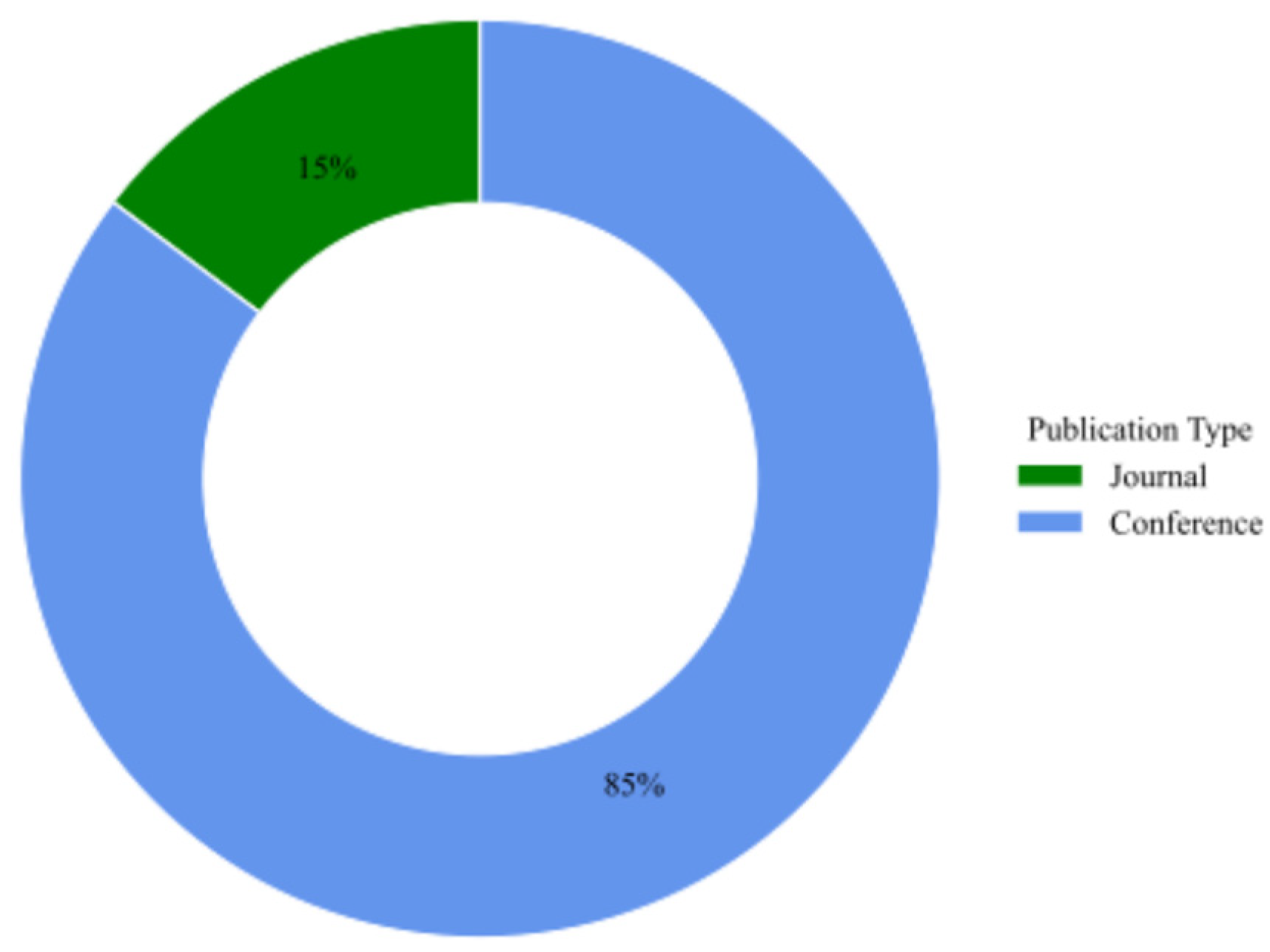

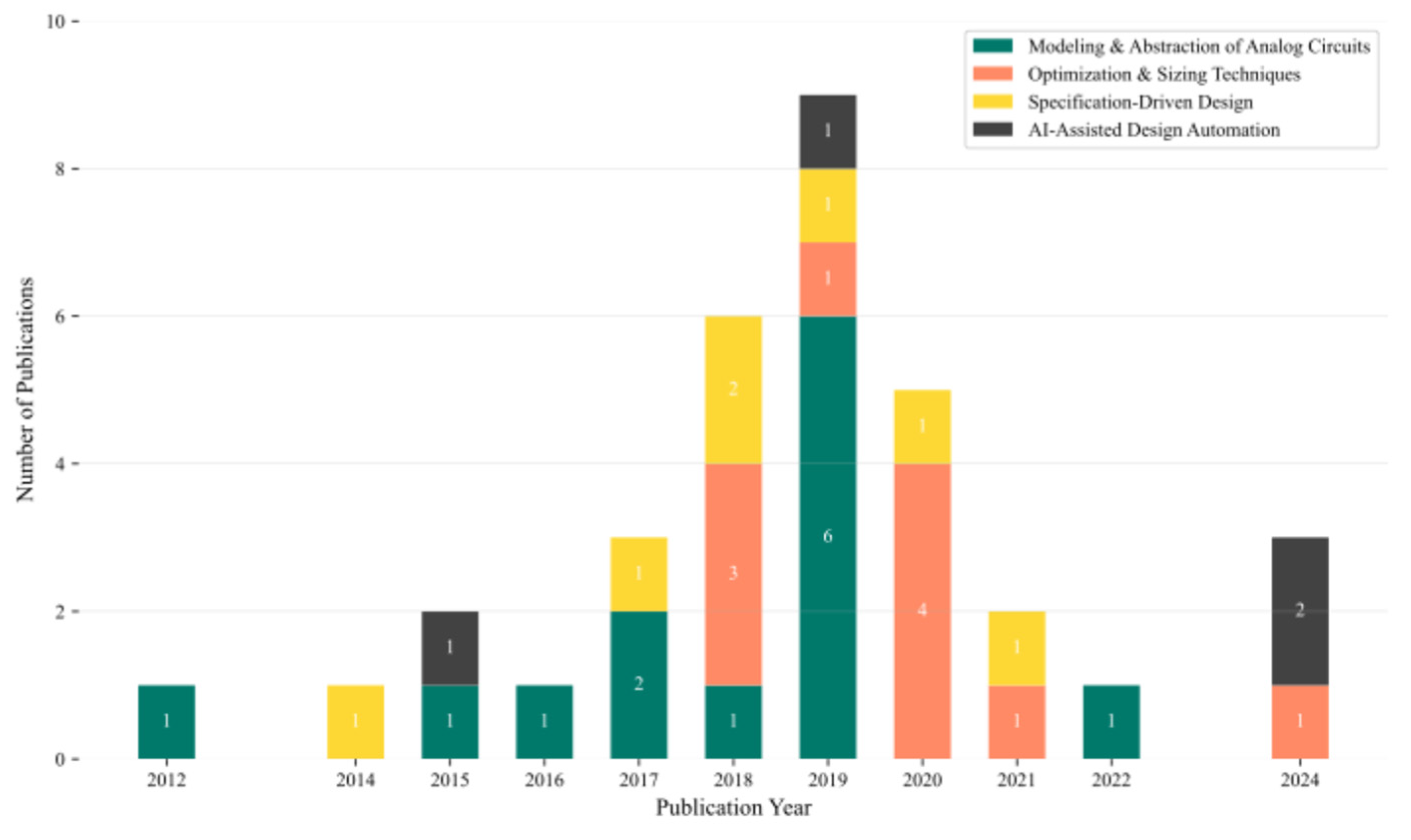

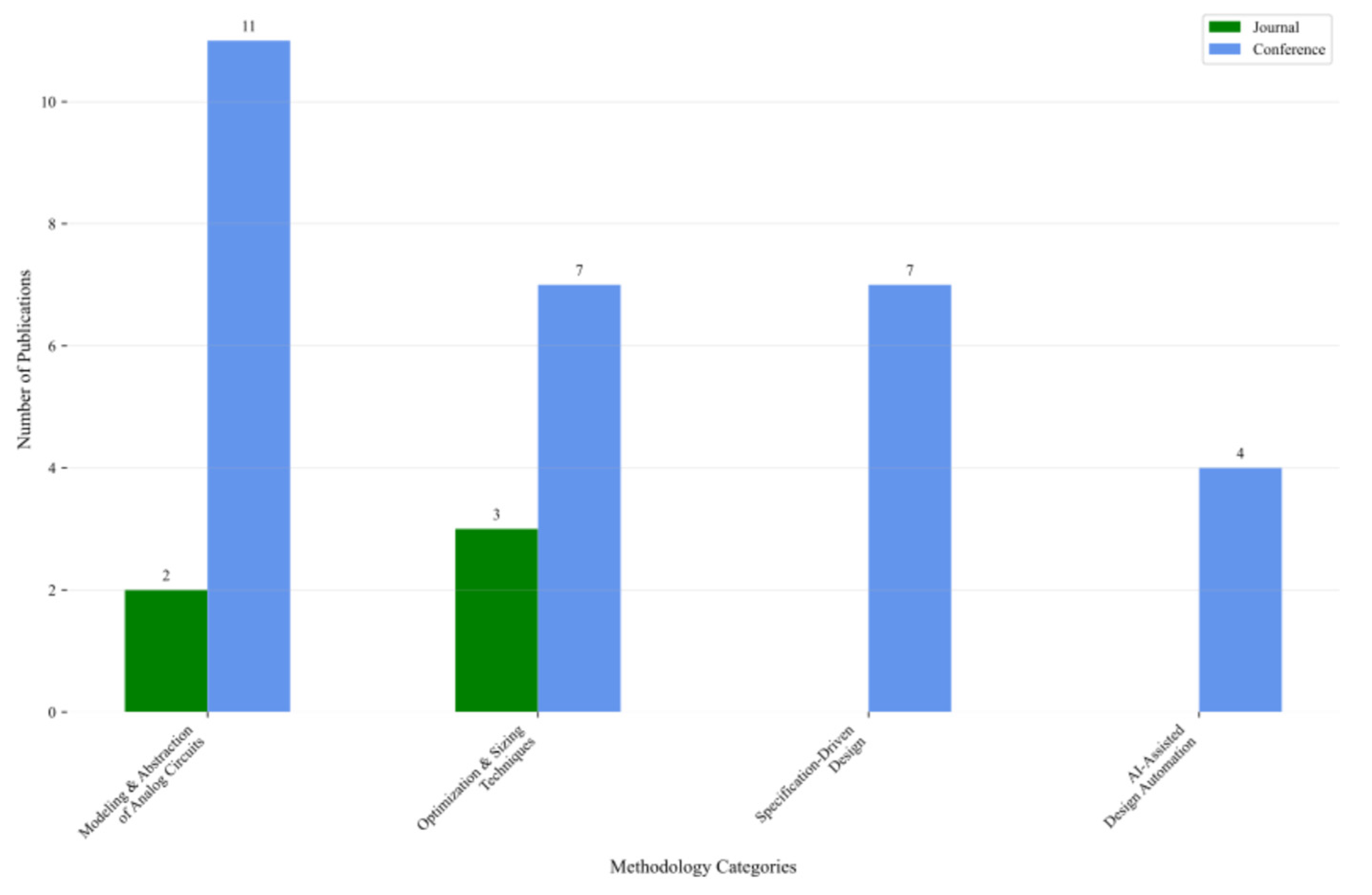

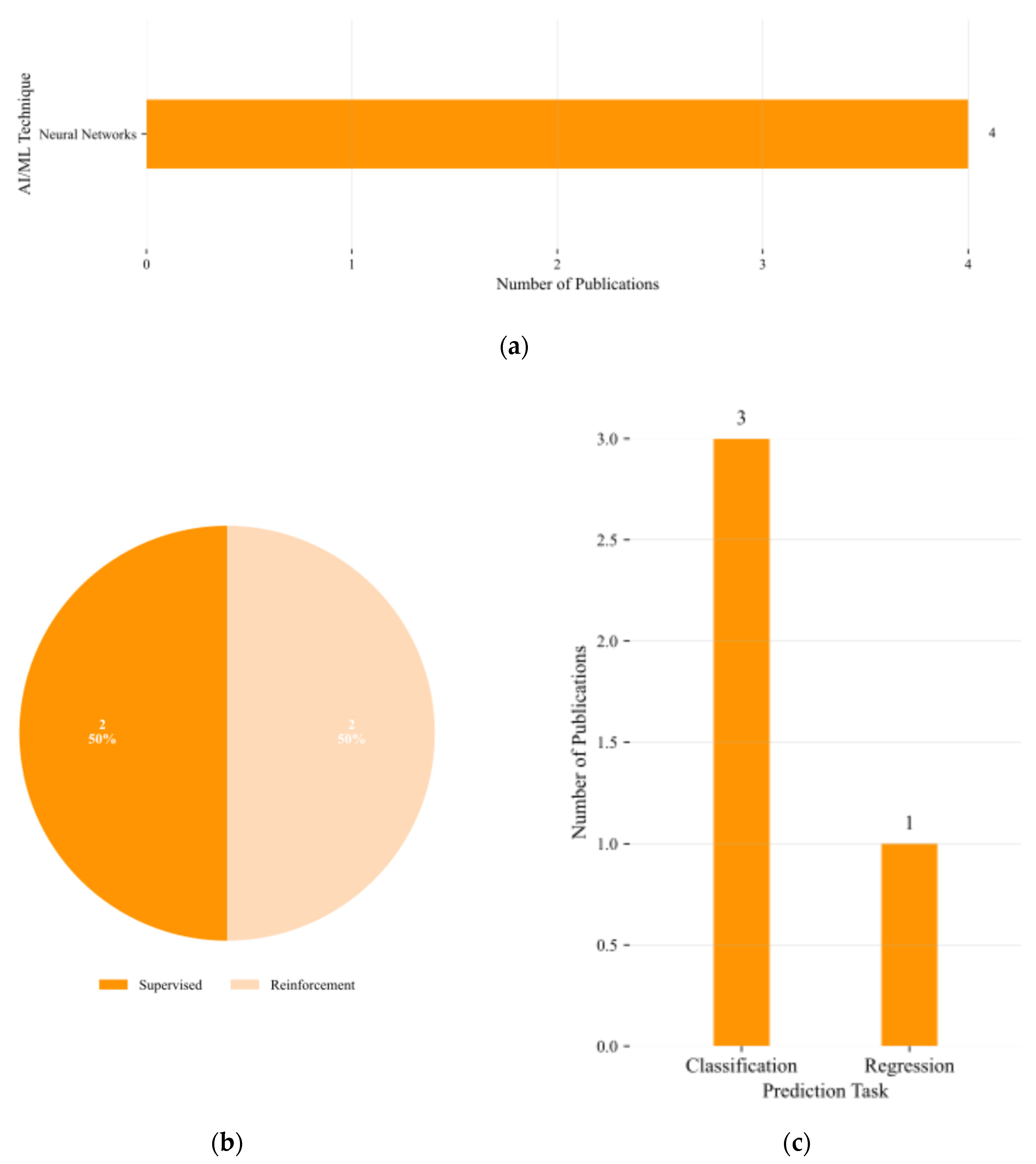

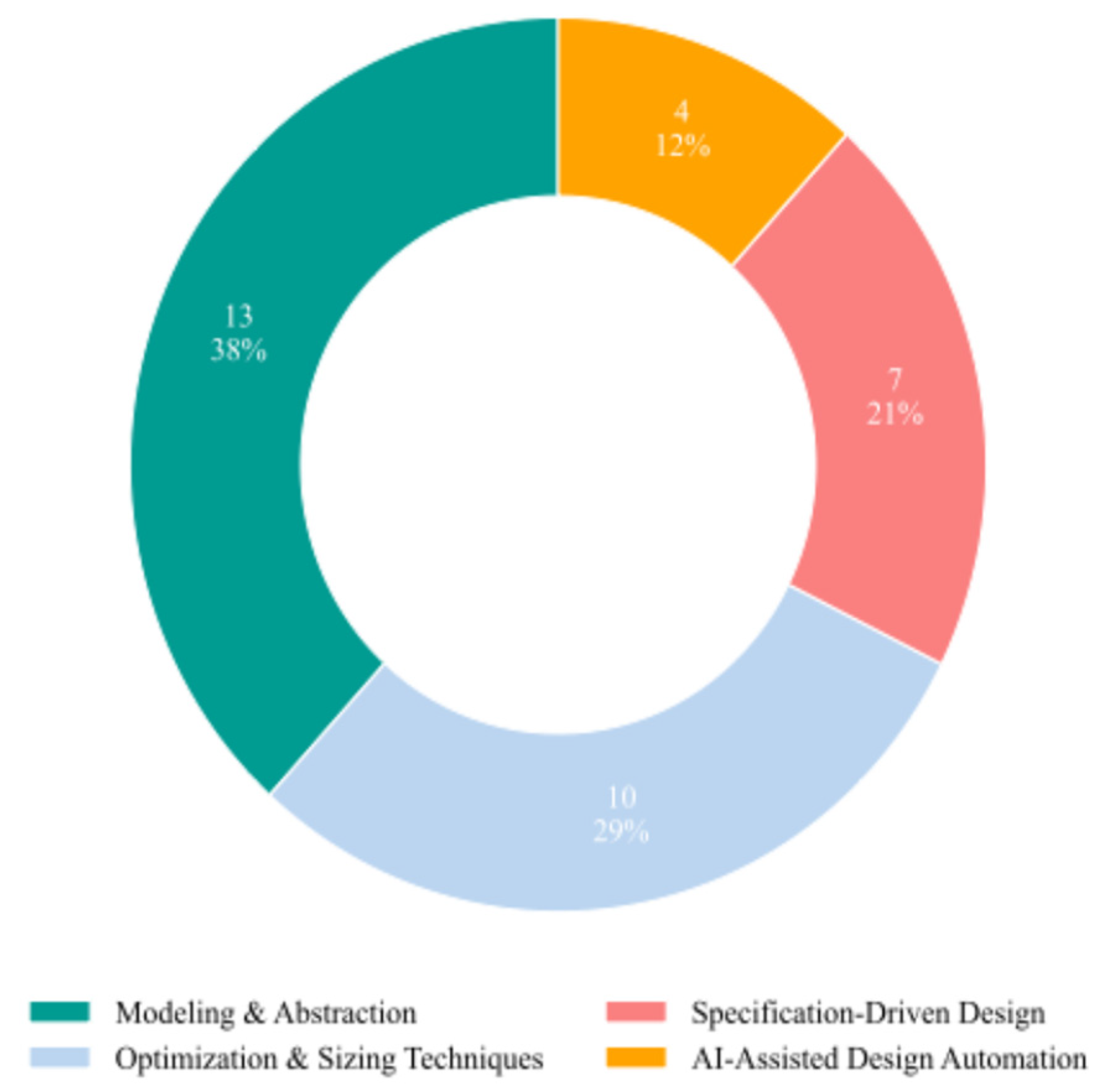

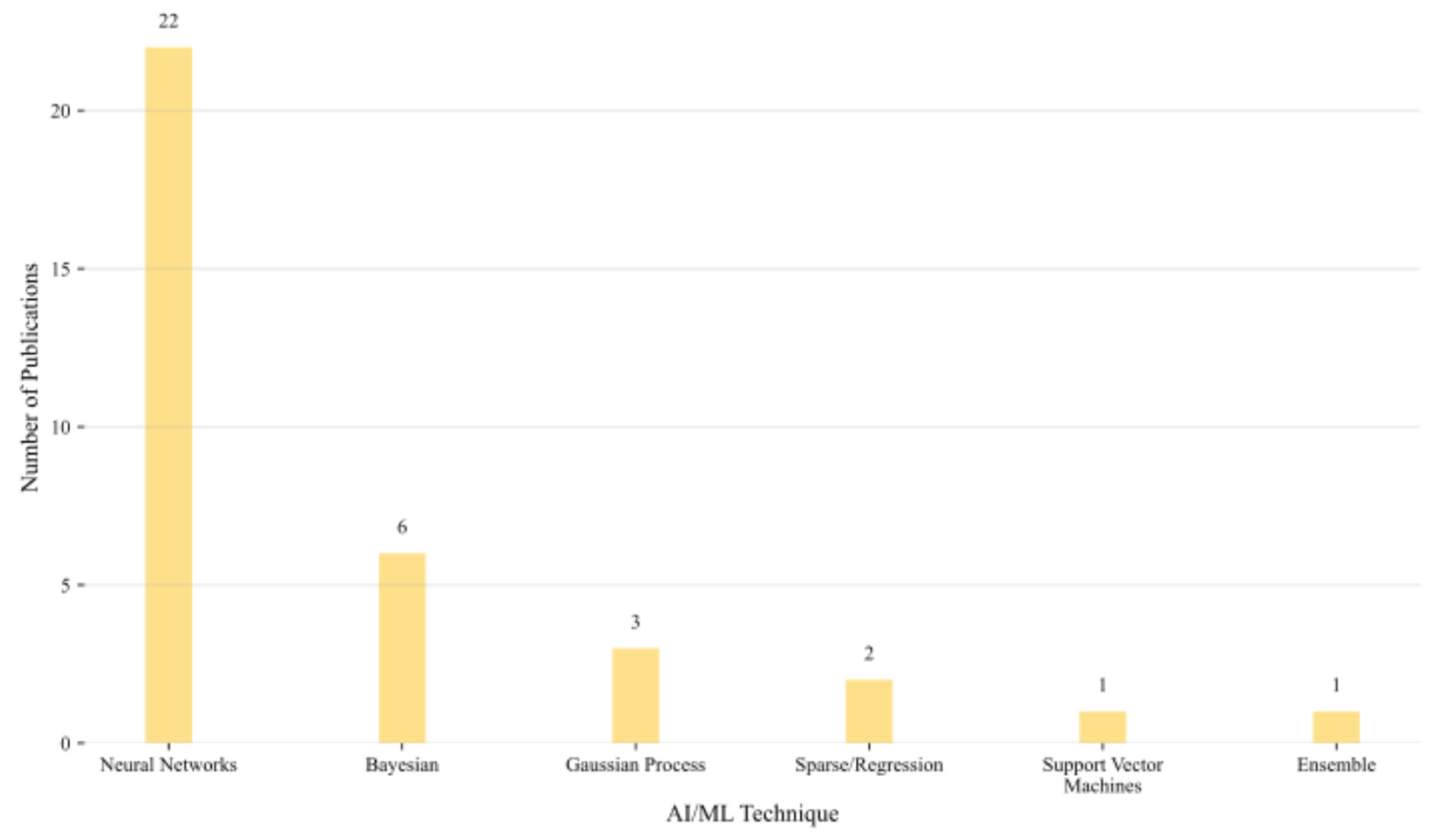

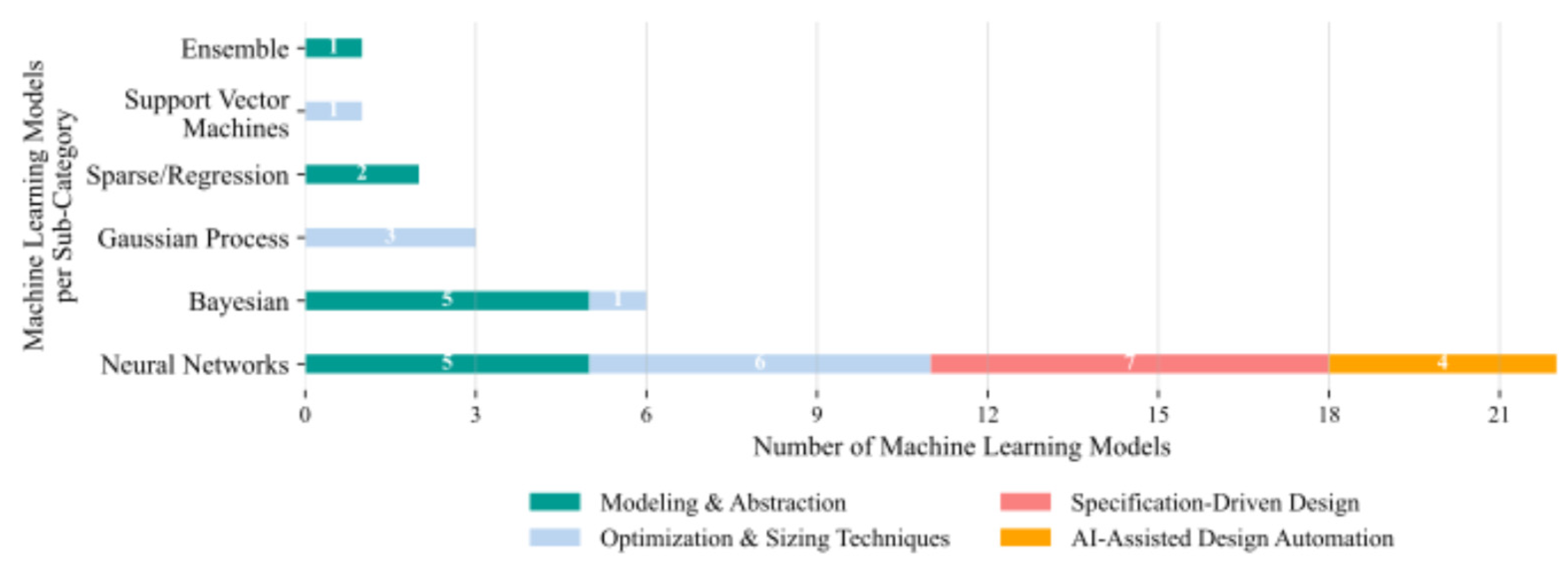

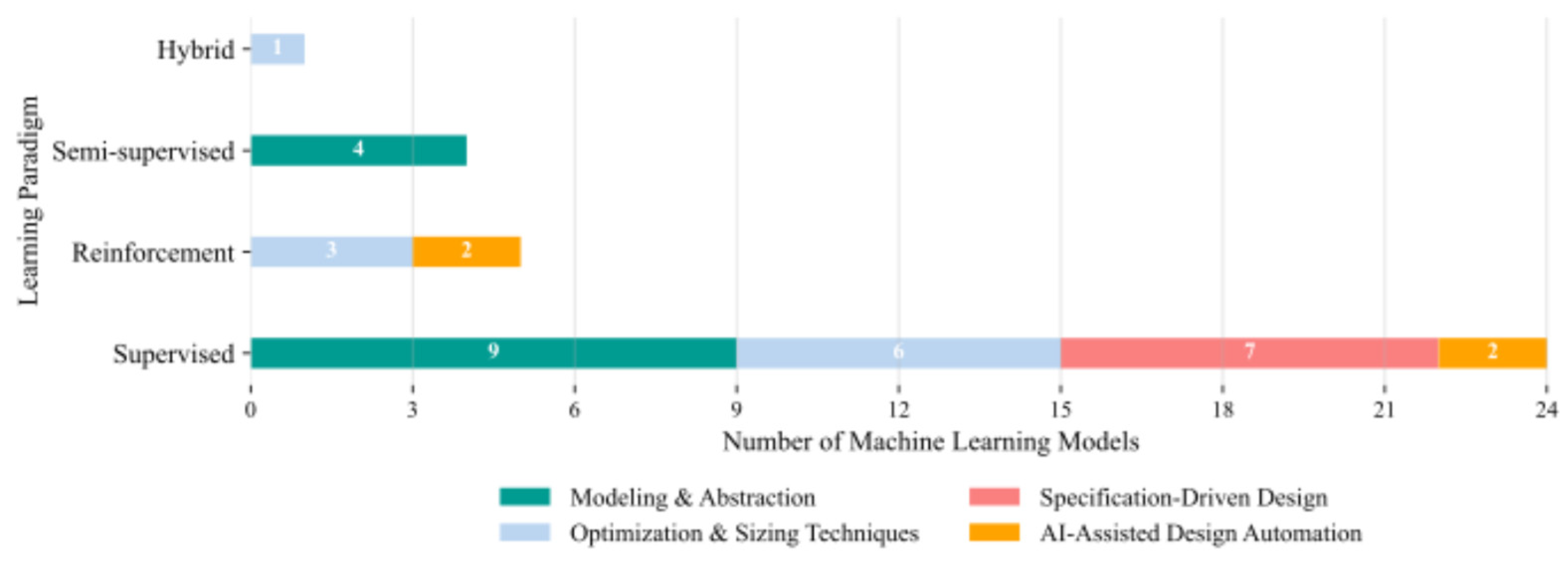

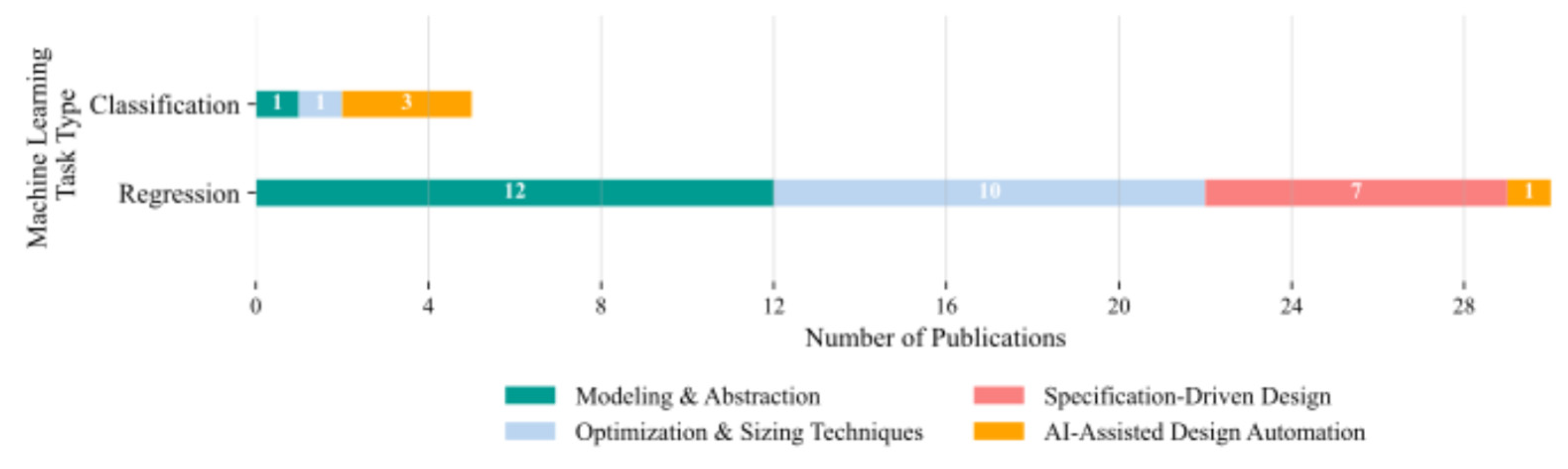

3.1. Studies Categorization

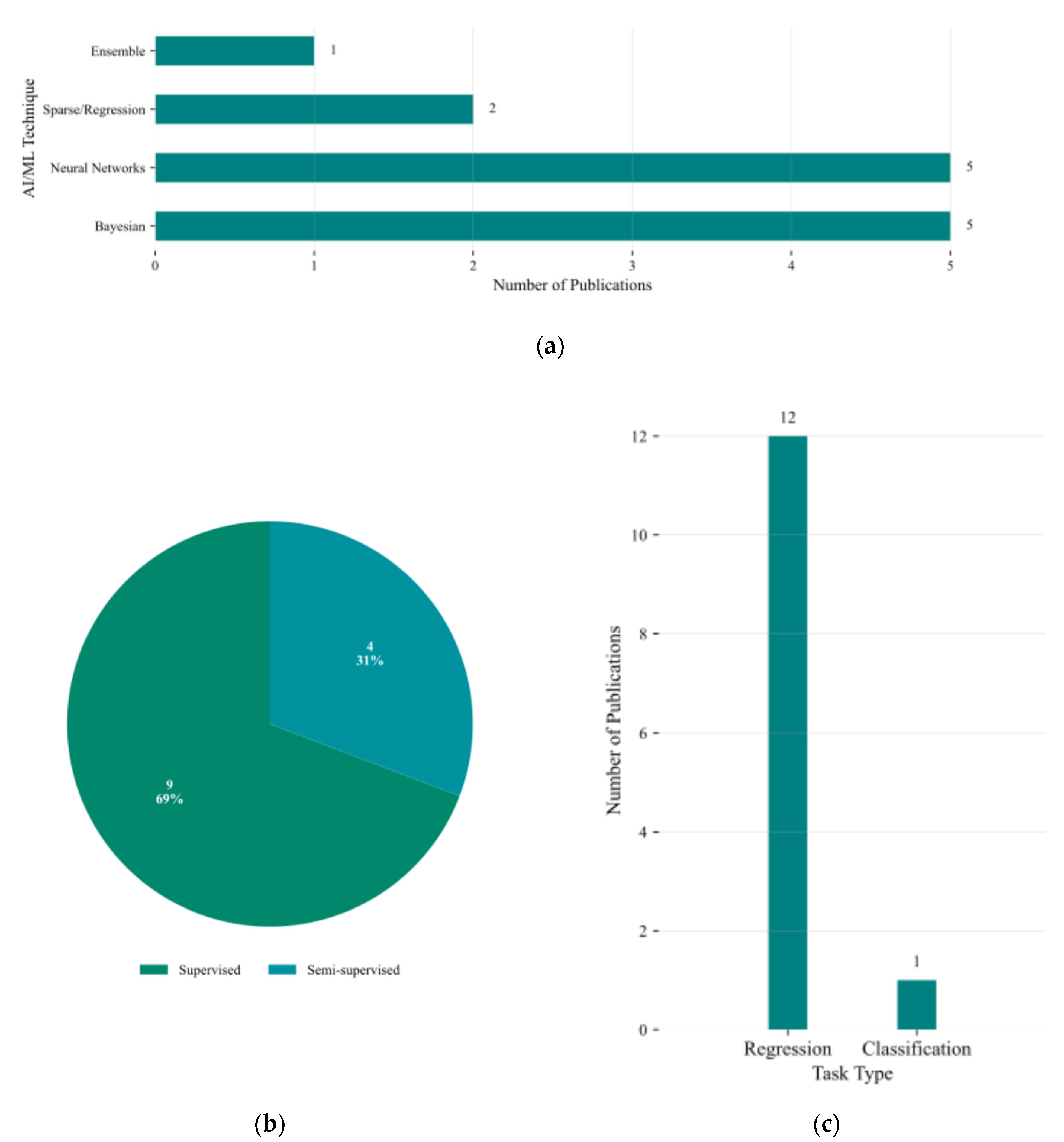

3.2. Modeling & Abstraction of Analog Circuits

3.2.1. Overview of Modeling & Abstraction of Analog Circuits Techniques

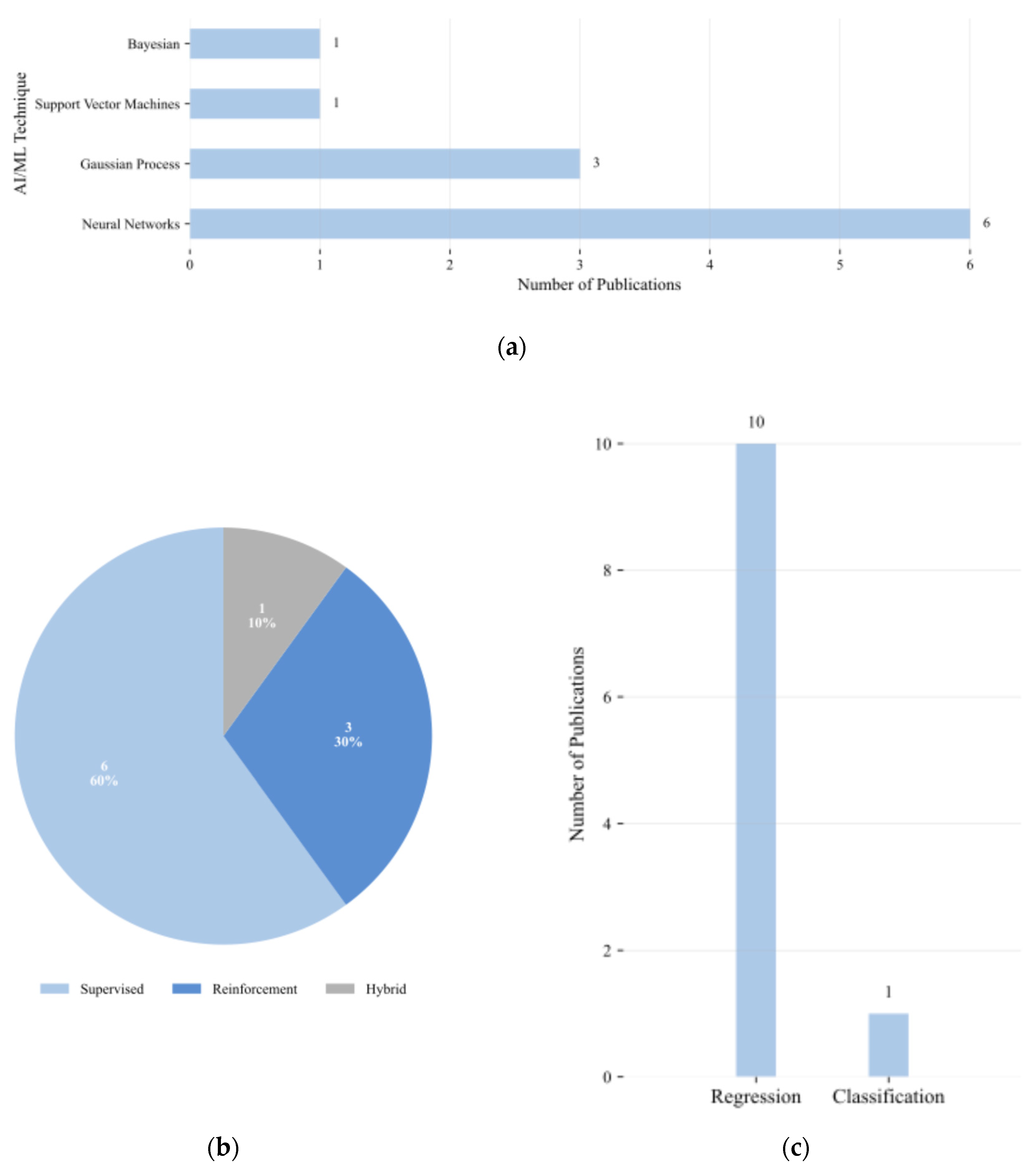

3.3. Optimization & Sizing Techniques

3.3.1. Overview of Optimization & Sizing Techniques

3.4. Specification-Driven Design

3.4.1. Overview of Specification-Driven Design Techniques

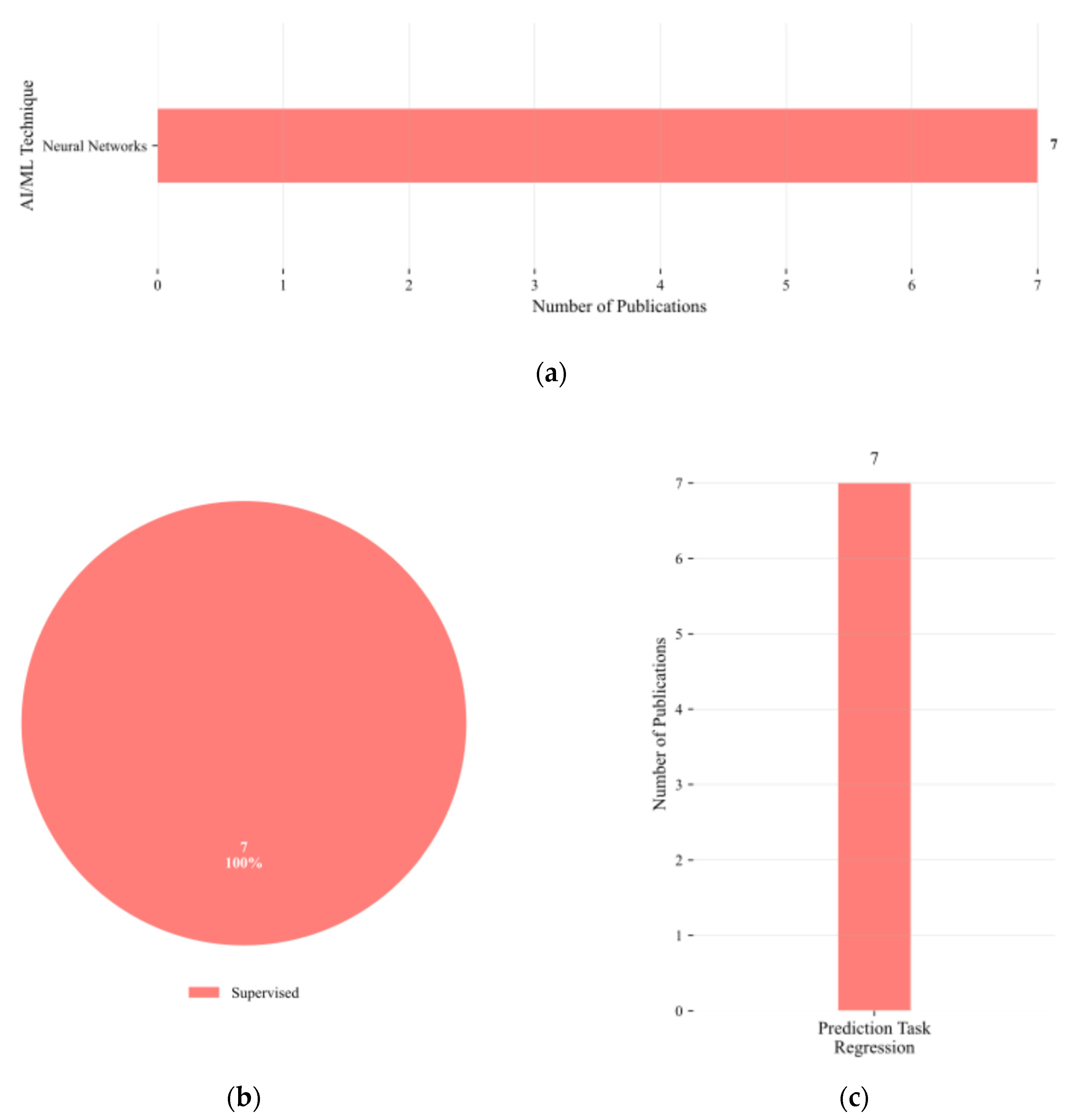

3.5. AI-Assisted Design Automation

3.5.1. Overview of AI-Assisted Design Automation Techniques

4. Discussion and Conclusions

5. Future Work

References

- R. Mina, C. Jabbour, and G. E. Sakr, “A Review of Machine Learning Techniques in Analog Integrated Circuit Design Automation,” 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Afacan, N. Lourenço, R. Martins, and G. Dündar, “Review: Machine learning techniques in analog/RF integrated circuit design, synthesis, layout, and test,” Integration, vol. 77, 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. Cao, M. Benosman, X. Zhang, and R. Ma, “Domain Knowledge-Infused Deep Learning for Automated Analog/Radio-Frequency Circuit Parameter Optimization,” May 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. F. Budak, P. Bhansali, B. Liu, N. Sun, D. Z. Pan, and C. V. Kashyap, “DNN-Opt: An RL Inspired Optimization for Analog Circuit Sizing using Deep Neural Networks,” Oct. 2021, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2110.00211.

- K. Settaluri, A. Haj-Ali, Q. Huang, K. Hakhamaneshi, and B. Nikolic, “AutoCkt: Deep Reinforcement Learning of Analog Circuit Designs,” in Proceedings of the 2020 Design, Automation and Test in Europe Conference and Exhibition, DATE 2020, 2020. [CrossRef]

- I. H. Sarker, “Machine Learning: Algorithms, Real-World Applications and Research Directions,” 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. LeCun, Y. Bengio, and G. Hinton, “Deep learning. Nature,” Nature, 2015.

- M. I. Jordan and T. M. Mitchell, “Machine learning: Trends, perspectives, and prospects,” 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. B. Kotsiantis, “Supervised Machine Learning: A Review of Classification Techniques,” Informatica, vol. 31, pp. 249–268, 2007. [CrossRef]

- I. Goodfellow, Y. Bengio, and A. Courville, “RegGoodfellow, I., Bengio, Y., & Courville, A. (2016). Regularization for Deep Learning. Deep Learning, 216–261.ularization for Deep Learning,” Deep Learning, pp. 216–261, 2016.

- C. M. Bishop, “Bishop - Pattern Recognition And Machine Learning - Springer 2006,” Antimicrob Agents Chemother, vol. 58, no. 12, 2014.

- X. Zhu, “Semi-Supervised Learning Literature Survey Contents,” SciencesNew York, vol. 10, no. 1530, 2008.

- O. Chapelle, B. Scholkopf, and A. Zien, Eds., “Semi-Supervised Learning (Chapelle, O. et al., Eds.; 2006) [Book reviews],” IEEE Trans Neural Netw, vol. 20, no. 3, 2009. [CrossRef]

- J. E. van Engelen and H. H. Hoos, “A survey on semi-supervised learning,” Mach Learn, vol. 109, no. 2, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen, M. Mancini, X. Zhu, and Z. Akata, “Semi-Supervised and Unsupervised Deep Visual Learning: A Survey,” IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell, vol. 46, no. 3, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Robert, “Machine Learning, a Probabilistic Perspective,” CHANCE, vol. 27, no. 2, 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. K. Jain, M. N. Murty, and P. J. Flynn, “Data clustering: A review,” in ACM Computing Surveys, 1999. [CrossRef]

- I. T. Jollife and J. Cadima, “Principal component analysis: A review and recent developments,” 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. S. Sutton and A. G. Barto, “Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction,” IEEE Trans Neural Netw, vol. 9, no. 5, 2005. [CrossRef]

- L. P. Kaelbling, M. L. Littman, and A. W. Moore, “Reinforcement learning: A survey,” Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, vol. 4, 1996. [CrossRef]

- C. Szepesvári, “Algorithms for reinforcement learning,” in Synthesis Lectures on Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning, 2010. [CrossRef]

- D. P. Bertsekas, “Dynamic Programming and Optimal Control 3rd Edition , Volume II by Chapter 6 Approximate Dynamic Programming Approximate Dynamic Programming,” Control, vol. II, 2010.

- C. E. Rasmussen, “Gaussian Processes in machine learning,” Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), vol. 3176, 2004. [CrossRef]

- M. Seeger, “Gaussian processes for machine learning.,” 2004. [CrossRef]

- B. Shahriari, K. Swersky, Z. Wang, R. P. Adams, and N. De Freitas, “Taking the human out of the loop: A review of Bayesian optimization,” 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. K. I. Williams, “Learning With Kernels: Support Vector Machines, Regularization, Optimization, and Beyond,” J Am Stat Assoc, vol. 98, no. 462, 2003. [CrossRef]

- C. Cortes and V. Vapnik, “Support-Vector Networks,” Mach Learn, 1995. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Freedman, Statistical models: Theory and practice. 2009. [CrossRef]

- A. J. Scott, D. W. Hosmer, and S. Lemeshow, “Applied Logistic Regression.,” Biometrics, vol. 47, no. 4, 1991. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Quinlan, “Induction of Decision Trees,” Mach Learn, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 81–106, 1986. [CrossRef]

- L. Breiman, J. H. Friedman, R. A. Olshen, and C. J. Stone, Classification and regression trees. 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. Chen and C. Guestrin, “XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system,” in Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2016. [CrossRef]

- D. M. W. Powers and Ailab, “EVALUATION: FROM PRECISION, RECALL AND F-MEASURE TO ROC, INFORMEDNESS, MARKEDNESS & CORRELATION.”.

- T. Saito and M. Rehmsmeier, “The precision-recall plot is more informative than the ROC plot when evaluating binary classifiers on imbalanced datasets,” PLoS One, vol. 10, no. 3, 2015. [CrossRef]

- T. Chai and R. R. Draxler, “Root mean square error (RMSE) or mean absolute error (MAE)? -Arguments against avoiding RMSE in the literature,” Geosci Model Dev, vol. 7, no. 3, 2014. [CrossRef]

- C. J. Willmott and K. Matsuura, “Advantages of the mean absolute error (MAE) over the root mean square error (RMSE) in assessing average model performance,” Clim Res, vol. 30, no. 1, 2005. [CrossRef]

- T. Hastie, R. Tibshirani, G. James, and D. Witten, “An introduction to statistical learning (2nd ed.),” Springer texts, vol. 102, 2021.

- X. Li, W. Zhang, F. Wang, S. Sun, and C. Gu, “Efficient parametric yield estimation of analog/mixed-signal circuits via Bayesian model fusion,” in IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer-Aided Design, Digest of Technical Papers, ICCAD, 2012. [CrossRef]

- F. Wang, M. Zaheer, X. Li, J. O. Plouchart, and A. Valdes-Garcia, “Co-Learning Bayesian Model Fusion: Efficient performance modeling of analog and mixed-signal circuits using side information,” in 2015 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer-Aided Design, ICCAD 2015, 2016. [CrossRef]

- F. Wang et al., “Bayesian model fusion: Large-scale performance modeling of analog and mixed-signal circuits by reusing early-stage data,” IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems, vol. 35, no. 8, 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Hasani, D. Haerle, C. F. Baumgartner, A. R. Lomuscio, and R. Grosu, “Compositional neural-network modeling of complex analog circuits,” in Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Neural Networks, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Alawieh, F. Wang, and X. Li, “Efficient Hierarchical Performance Modeling for Integrated Circuits via Bayesian Co-Learning,” in Proceedings - Design Automation Conference, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yang et al., “Smart-MSP: A Self-Adaptive Multiple Starting Point Optimization Approach for Analog Circuit Synthesis,” IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems, vol. 37, no. 3, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Z. Gao, J. Tao, F. Yang, Y. Su, D. Zhou, and X. Zeng, “Efficient performance trade-off modeling for analog circuit based on Bayesian neural network,” in IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer-Aided Design, Digest of Technical Papers, ICCAD, 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Islamoǧlu, T. O. Çakici, E. Afacan, and G. Dundar, “Artificial Neural Network Assisted Analog IC Sizing Tool,” in SMACD 2019 - 16th International Conference on Synthesis, Modeling, Analysis and Simulation Methods and Applications to Circuit Design, Proceedings, 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Hakhamaneshi, N. Werblun, P. Abbeel, and V. Stojanovic, “BagNet: Berkeley analog generator with layout optimizer boosted with deep neural networks,” in IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer-Aided Design, Digest of Technical Papers, ICCAD, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhang, W. Lyu, F. Yang, C. Yan, D. Zhou, and X. Zeng, “Bayesian Optimization Approach for Analog Circuit Synthesis Using Neural Network,” in Proceedings of the 2019 Design, Automation and Test in Europe Conference and Exhibition, DATE 2019, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. B. Alawieh, S. A. Williamson, and D. Z. Pan, “Rethinking sparsity in performance modeling for analog and mixed circuits using spike and slab models,” in Proceedings - Design Automation Conference, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. B. Alawieh, X. Tang, and D. Z. Pan, “S 2 -PM: Semi-supervised learning for efficient performance modeling of analog and mixed signal circuits,” in Proceedings of the Asia and South Pacific Design Automation Conference, ASP-DAC, 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Gabourie, C. Mcclellan, and S. Suryavanshi, “Analog Circuit Design Enhanced with Artificial Intelligence,” 2022.

- M. Wang et al., “Efficient Yield Optimization for Analog and SRAM Circuits via Gaussian Process Regression and Adaptive Yield Estimation,” IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems, vol. 37, no. 10, 2018. [CrossRef]

- W. Lyu et al., “An efficient Bayesian optimization approach for automated optimization of analog circuits,” IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I: Regular Papers, vol. 65, no. 6, 2018. [CrossRef]

- W. Lyu, F. Yang, C. Yan, D. Zhou, and X. Zeng, “Batch Bayesian optimization via multi-objective acquisition ensemble for automated analog circuit design,” in 35th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2018, 2018.

- P. C. Pan, C. C. Huang, and H. M. Chen, “Late breaking results: An efficient learning-based approach for performance exploration on analog and RF circuit synthesis,” in Proceedings - Design Automation Conference, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, Y. Wang, Y. Li, R. Zhou, and Z. Lin, “An Artificial Neural Network Assisted Optimization System for Analog Design Space Exploration,” IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems, vol. 39, no. 10, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhao and L. Zhang, “Deep reinforcement learning for analog circuit sizing,” in Proceedings - IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems, 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang, J. Yang, H.-S. Lee, and S. Han, “Learning to Design Circuits,” Dec. 2020, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/1812.02734.

- S. Devi, G. Tilwankar, and R. Zele, “Automated Design of Analog Circuits using Machine Learning Techniques,” in 2021 25th International Symposium on VLSI Design and Test, VDAT 2021, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yin, Y. Wang, B. Xu, and P. Li, “ADO-LLM: Analog Design Bayesian Optimization with In-Context Learning of Large Language Models,” in IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer-Aided Design, Digest of Technical Papers, ICCAD, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- E. Dumesnil, F. Nabki, and M. Boukadoum, “RF-LNA circuit synthesis by genetic algorithm-specified artificial neural network,” in 2014 21st IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Circuits and Systems, ICECS 2014, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Fukuda, T. Ishii, and N. Takai, “OP-AMP sizing by inference of element values using machine learning,” in 2017 International Symposium on Intelligent Signal Processing and Communication Systems, ISPACS 2017 - Proceedings, 2017. [CrossRef]

- N. Lourenco et al., “On the Exploration of Promising Analog IC Designs via Artificial Neural Networks,” in SMACD 2018 - 15th International Conference on Synthesis, Modeling, Analysis and Simulation Methods and Applications to Circuit Design, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang, X. Luo, and Z. Gong, “Application of deep learning in analog circuit sizing,” in ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, 2018. [CrossRef]

- N. Lourenço et al., “Using Polynomial Regression and Artificial Neural Networks for Reusable Analog IC Sizing,” in SMACD 2019 - 16th International Conference on Synthesis, Modeling, Analysis and Simulation Methods and Applications to Circuit Design, Proceedings, 2019. [CrossRef]

- V. M. Harsha and B. P. Harish, “Artificial Neural Network Model for Design Optimization of 2-stage Op-amp,” in 2020 24th International Symposium on VLSI Design and Test, VDAT 2020, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. D. Murphy and K. G. McCarthy, “Automated Design of CMOS Operational Amplifier Using a Neural Network,” in 2021 32nd Irish Signals and Systems Conference, ISSC 2021, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhang, L. Huang, Z. Wang, and N. Verma, “A seizure-detection IC employing machine learning to overcome data-conversion and analog-processing non-idealities,” in Proceedings of the Custom Integrated Circuits Conference, 2015. [CrossRef]

- K. Hakhamaneshi, N. Werblun, P. Abbeel, and V. Stojanović, “Late breaking results: Analog circuit generator based on deep neural network enhanced combinatorial optimization,” in Proceedings - Design Automation Conference, 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Basso, L. Bortolussi, M. Videnovic-Misic, and H. Habal, “Fast ML-driven Analog Circuit Layout using Reinforcement Learning and Steiner Trees,” May 2024, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2405.16951.

- A. Mehradfar et al., “AICircuit: A Multi-Level Dataset and Benchmark for AI-Driven Analog Integrated Circuit Design,” Jul. 2024, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2407.18272.

| Cite | Data Size | Observed Features | AI Method | Evaluation | Results |

| [38] | RO: 4000 samples SRAM: 1000 samples |

Power consumption, oscillation frequency, phase noise, and propagation delay | Semi-supervised BMF regressor | Prediction error | ~0.2 – 2% |

| [39] | RO: 750 fundamental frequencies and 10 phase noise samples, LNA: 13 forward gain and 1 noise figure samples |

Device-level process variations like, threshold voltage, oscillation frequency, noise figure, and forward gain | Semi-supervised CL-BMF regressor | Relative error | ~0.28 – 0.33 dB |

| [40] | Schematic: 3000 samples, Post-layout RO: 300 samples, Post-layout SRAM: 300 samples |

Device-level variations and layout extracted parasitics | Supervised BMF regressor | Relative error | < 2% |

| [41] | Trimming: 695 samples, Load jumps: 433 samples, Line jumps: 501 samples |

Trimming behavior and dynamic load/line transitions time-series signals | Supervised NARX and TDNN regressor | MSE, and Correlation coefficient (R) |

Trimming: 7e-5, Load: 5.6e-3, Line: 1.4e-3, R > 0.96 |

| [42] | Delay-line: 100 labeled and 300 unlabeled samples, Amplifier: 250 labeled and 450 unlabeled samples |

Propagation delay and power consumption across hierarchical circuit blocks | Semi-supervised BCL regressor | Relative error | Delay-line: 0.13%, Amplifier: 0.55% |

| [43] | Simulated-oriented programmable amplifier: 3,000–100,000 samples | Transistor sizing width & length, biasing parameters, voltage gain, and phase margin |

Supervised G-OMP regressor | No explicit modeling error metric reported | Authors confirm equivalent or improved solution quality |

| [44] | Charge pump: 200 samples, Amplifier: 260 samples |

Transistor width parameters and circuit-level performance metrics | Supervised BNN regressor | Hypervolume (HV) and Weighted gain (WG) |

Charge pump: 15.04 HV and 0.19 WG, Amplifier: 10.72 HV and 102 WG |

| [45] | Over iterative design generations: 20,000 samples | Transistor sizing ratios width & length, bias currents, and power consumption | Supervised FNN regressor | No explicit modeling error metric reported | Authors confirm ANN outputs closely match SPICE simulation results |

| [46] | Optical receiver: 435 samples, DNN queries: 77,487 samples |

Voltage gain, phase margin, diagram margin, and post-layout design specifications | Supervised DNN classifier | Sample compression efficiency | 300× |

| [47] | Operational amplifier: 130 samples, Charge pump: 890 samples |

Design specifications like, voltage gain, phase margin, transistor dimensions width & length, and passive components resistance, capacitance | Supervised Ensemble (BO|GP|NN) regressor | Figure of Merit (FOM) | Operational amplifier: FOM not reported Charge pump: 3.17 FOM |

| [48] | Labeled: 90 samples, Gibbs: 2800 samples |

High-dimensional process parameters targeting power performance | Supervised ANN regressor | Relative error | 2.39% |

| [49] | Comparator: 50 orthogonal matching pursuit (OMP) samples and 70 S2-PM samples, Voltage-controlled oscillator: 50 OMP samples and 40 S2-PM samples, Unlabeled: 20 samples |

Process variation parameters, including threshold voltage shifts | Semi-supervised Sparse regressor | Relative error | Comparator: OMP: 2.50%, S2-PM: 2.53% and Voltage-controlled oscillator: OMP: 1.55%, S2-PM: 1.6% |

| [50] | PySPICE: 4000 samples | Input impedance, voltage gain, power consumption, transistor dimensions width & length, and passive components resistance, capacitance | Supervised FNN regressor | MSE | 10⁻⁴ with ideal model, 10⁻² with PySpice |

| Cite | Data Size | Observed Features | AI Method | Evaluation | Results |

| [51] | 24 parameters and 50,000 Monte Carlo simulations used for yield estimation | Design parameters, includes sizing, yield, and process corner metrics | Supervised BO–GPR regressor | Failure rate | 1% |

| [52] | Simulation budget of 100–1000 per circuit, including 20–40 initial design-of-experiment (DoE) samples | Design variables like, transistor sizes, passive dimensions, biasing levels and performance metrics like, gain, efficiency, area | Supervised BO–GPR regressor | No explicit modeling error metric reported | Demonstrated equal or superior Pareto quality with significantly reduced simulation cost |

| [53] | Operational amplifier: 500 samples, Power amplifier: 500 samples |

Includes performance specifications such as gain, phase margin, unity-gain frequency, power-added efficiency, and output power, along with design variables such as transistor dimensions, resistor, and capacitor values | Supervised BO–GPR regressor | No explicit modeling error metric reported | Demonstrated equal or superior Pareto front quality with 4–5× fewer simulations compared to non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm – II (NSGA-II) and genetic algorithm-based sizing of parameters for analog design (GASPAD) |

| [54] | Genetic algorithm: 260 population samples and 16 sampling segments | Device sizing parameters such as transistor geometry and biasing levels, along with performance metrics including gain, power, and bandwidth | Supervised BLR regressor and SVM classifier | No explicit modeling error metric reported | Demonstrated comparable or improved performance metrics with up to 1245%–1518% speed-up in circuit synthesis |

| [55] | Operational amplifier: 158 samples, Cascode band-pass filter circuit: 632 samples |

Includes transistor widths, resistances, and capacitances, along with performance metrics such as gain, unity-gain bandwidth, bandwidth, and phase margin | Supervised ANN regressor | Model error and R |

< 1% and 0.99 |

| [56] | 50,000 training tuples | Design variables such as transistor lengths, widths, and bias voltages, as well as performance attributes like DC gain, bandwidth, phase margin, and gain margin | Reinforcement PGNN regressor |

No explicit prediction error metrics reported | Model performance evaluated via convergence of the reward function, defined as a weighted combination of normalized DC gain, bandwidth, phase margin, and gain margin |

| [57] | Three-stage transimpedance amplifier: 40.000 SPICE samples, Two-stage transimpedance amplifier: 50.000 SPICE samples |

Circuit operating characteristics including DC operating points and AC magnitude/phase responses, along with transistor–level parameters such as threshold voltage, transconductance, and saturation voltage | Reinforcement DDPG regressor |

No explicit surrogate-model error metrics reported | Three-stage transimpedance amplifier: satisfied FOM score with a 250× reduction. Two-stage transimpedance amplifier: reached 97.1% of expert-designed bandwidth with a 25× improvement in sample efficiency |

| [5] | Transimpedance amplifier: 500 samples, Operational amplifier: 1000 samples, Passive-element filter: 40 samples |

Design objectives include gain, bandwidth, phase margin, power, and area, evaluated against design-space parameters such as transistor widths/lengths, capacitor values, and resistor values | Reinforcement DNN-PPO regressor |

No explicit surrogate-model error metric | Achieved 40 × higher sample efficiency than a genetic-algorithm baseline |

| [58] | Width-over-length sweep: 65.534 samples, Transconductance-to-drain-current sweep: 7.361 samples, GA-guided local refinement: 632 samples |

Design objectives include voltage gain, phase margin, unity-gain frequency, power consumption, and slew rate | Supervised ANN and Reinforcement DDPG regressors | Prediction score | Width-over-length sweep: 90%, Transconductance-to-drain-current sweep: 93%, GA-guided local refinement: 75.8% and DDPG 25–250× less sample-efficient than the supervised/GA pipeline |

| [59] | Five seed points plus twenty iterations, each evaluating one LLM-generated and four GP-BO candidates: 105 samples | Amplifier: 14 continuous design variables - all transistor widths / lengths plus compensation resistor Rz and capacitor Cc), Comparator: 12 continuous design variables - width and length of six transistors |

Supervised LLM-guided GP–BO regressor | No explicit surrogate-model error metric | Satisfies every design specification for both amplifier and comparator, achieves the top figure-of-merit among all methods, and reaches convergence with a 4 × reduction in optimization iterations |

| Cite | Data Size | Observed Features | AI Method | Evaluation | Results |

| [60] | Low-noise amplifier: 235 samples | Bandwidth, 1-dB compression point, center frequency, third-order intercept point, noise figure, forward gain, transistor width/length ratio, source inductance, bias voltage | Supervised ANN regressor | Prediction accuracy | Matching networks: 99.22% accuracy, Transistor geometries: 95.23% accuracy |

| [61] | 20,000 samples after cleaning and normalization | Current and power consumption, direct current gain, phase margin, gain bandwidth product, slew rate, total harmonic distortion, common and power rejection ratio, output and input voltage range, output resistance, input referred noise |

Supervised FNN regressor | Average prediction accuracy | 92.3% |

| [62] | Original: 16,600 samples, Augmented: 700,000 samples |

Direct current gain, supply current consumption, gain–bandwidth, phase margin | Supervised ANN regressor | MSE and MAE |

0,0123 and 0,0750 |

| [63] | Not precisely specified, 5.000 – 40.000 samples |

Gain, bandwidth, power consumption | Supervised DNN regressor | Average match rate and RMSE |

95.6% and ≈30 |

| [64] | Pareto-optimal circuit sizing solutions: 700 samples | Load capacitance, circuit performance measures such as gain, unity gain frequency, power consumption, phase margin, widths and lengths | Supervised MP and ANN regressors | MAE | MP: 0.00807 and ANN: 0.00839 |

| [65] | SPICE: 7.409 samples | Gain, phase margin, unity gain bandwidth, area, slew rate, power consumption, widths and lengths of selected transistors, bias current, and compensation capacitor | Supervised ANN regressor | MSE and R2 |

≈ 4.26e-10 and 94.29% |

| [66] | LT-SPICE: 40.000 samples | DC gain, phase margin, unity-gain bandwidth, slew rate, area, compensation capacitor value and transistor widths, lengths, compensation capacitor, and bias current | Supervised FNN regressor | MAE | 0.160 |

| Cite | Data Size | Observed Features | AI Method | Evaluation | Results | ||||||

| [67] | Electroencephalogram segments: 4.098 samples | Frequency-domain energy in multiple bands and time-domain characteristics | Supervised ANN classifier | Accuracy, Recall |

≈96% and ≈95% |

||||||

| [68] | Post-layout simulated designs: 338 samples | Design parameters of an optical link receiver front-end in 14 nm technology, including resistor dimensions, capacitor dimensions, and transistor properties such as number of fins and number of fingers; performance metrics such as gain, bandwidth, and other specification errors | Supervised DNN classifier | No explicit surrogate-model evaluation metric reported | Specification-compliant design in 338 simulations, 7.1 hours, over 200× faster than baseline | ||||||

| [69] | Synthetic floorplans with 5–20 devices for training, 11-device circuit for evaluation, no explicit total sample count reported | Topological relationships between devices represented as sequence pairs; device parameters such as dimensions, shape configurations, symmetry, and alignment; performance objectives including occupied area and half-perimeter wirelength | Reinforcement DNN classifier |

No explicit model-level evaluation metric reported | Reduced refinement effort by 95.8%, and produced layouts 13.8% smaller and 14.9% shorter than manual designs | ||||||

| [70] | No explicit dataset size reported, multiple analog circuit topologies, including telescopic and folded cascode operational amplifiers | Gain, phase margin, power consumption, and slew rate, transistor dimensions, bias currents, and compensation capacitance | Reinforcement DNN regressor |

No explicit model-level evaluation metric reported | Fewer simulations, demonstrating higher sample efficiency in sizing multiple analog amplifier topologies | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).