1. Introduction

Ultrashort pulse fiber lasers have been extensively investigated owing to their inherent advantages of high pulse quality, compactness, flexibility, and compactness, making them suitable for a wide range of applications in micromachining, biomedical science, spectroscopy, and ultrafast photonics [

1,

2,

3,

4]. As the primary approach to obtain ultrashort pulses in fiber lasers, mode-locking technology are generally implemented with various saturable absorbers (SAs), which are typically classified into two categories: artificial SAs and real SAs. Artificial SAs leverage nonlinear effects to realize the saturable absorption function, such as nonlinear polarization rotation (NPR) [

5]; whereas lasers mode-locked by NPR may exhibit fluctuations in stability during prolonged use, potentially due to their heightened sensitivity to external environmental influences. Meanwhile, the implementation of an all-fiber structure with a real saturable absorber enables the advancement of fiber lasers from the laboratory research stage to that of a commercial instrument. In practice, real SAs exploit the intrinsic properties of the materials employed to achieve intensity-dependent nonlinear absorption, exemplified by semiconductor saturable absorption mirrors (SESAMs) [

6], single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) [

7], graphene [

8], topological insulators (TIs) [

9], transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) [

10], black phosphorus (BP) [

11], among others [

12]. Nevertheless, these saturable absorbers still present some challenges. SESAMs, constrained by their inherent energy bandgap, typically demonstrate a narrow operational bandwidth and are associated with high costs due to the sophisticated and specialized equipment required for their fabrication. The operational bandwidth of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) is contingent upon the diameter of the CNTs employed, yet integrating CNT composites into high-power fiber lasers increases the risk of damage. In contrast, graphene offers a wider operating bandwidth, rendering it more suitable for mode-locked lasers; nonetheless, the modulation depth of single-layer graphene is typically inferior to 1%, which results in a low saturation strength and, consequently, a significant limitation on the pulse energy and duration [

13]. For TIs and TMDs, chemical vapor deposition (CVD) and/or pulsed laser deposition (PLD) are inevitably used in the fabrication of SAs, rendering the manufacturing process highly complex [

14]. Additionally, BP is inherently unstable because of its susceptibility to moisture absorption and oxidation, giving rise to substantial fluctuations in its optical properties.

Recently, organic liquid-based saturable absorbers have attracted tremendous attention for the generation of ultrashort pulses. As a novel kind of saturable absorber, organic liquid-SAs possess virtues of a broad wavelength absorption range, high liquidity, effective heat diffusivity, high damage thresholds, cost-effectiveness and easy of fabrication. In 2015, Z. Wang et al. first demonstrated a self-starting ultrafast fiber laser mode-locked by alcohol-SA, where a bright pulse working at 1.6 μm was produced with the pulse duration of 972 fs and pulse energy of ∼0.6 nJ[

15]. Subsequently, Q-switched fiber lasers based on alcohol saturable absorber were also reported, generating pulses operating at 1.55 μm (C waveband) in an Er -doped laser cavity and 1.88μm in a Tm-doped laser cavity, respectively [

16,

17]. Moreover, the modulation depth of alcohol saturable absorbers can be readily adjusted by varying the concentration of organic liquid used, thereby accommodating the diverse requirements of ultrafast fiber lasers in different design situations. Nevertheless, the volatility of alcohol necessitates tightly sealed packaging to ensure its stability. Consequently, alternative non-volatile organic liquid SAs, such as HQCDCL2H2O[

18], pure water[

19,

20], glycerin[

21], acetone[

22], and ethylene glycol[

23], have been successively explored and proposed, prompting a rapid development of pulsed fiber lasers based on organic liquid-SAs.

To date, most research of mode-locked fiber lasers employing organic liquid absorber has focused on the anomalous dispersion region, where conventional solitons (CSs) are initiated through the interplay between self-phase modulation (SPM) and group velocity dispersion (GVD). Notably, according to the soliton area theorem determination, the energy of a single CS pulse is inherently limited, with further increases in pump power leading to pulse splitting [

24]. In comparison, dissipative solitons (DSs) realized in net-normal-dispersion or/and in all-normal-dispersion region can achieve relatively high pulse energies, where nonlinearity, dispersion, gain and loss within the cavity need to accomplish in a multifaceted balance [

25]. Therefore, exploring the use of organic liquid SAs to generate dissipative solitons in normal dispersion lasers presents fascinating possibilities.

In this paper, we experimentally demonstrate that by adopting an ethylene glycol saturable absorber, stabilized mode-locking operation are obtained in a net positive dispersion laser. Both individual dissipative soliton and multiple dissipative solitons (involving soliton pairs and soliton triplets) are successfully attained by precisely manipulating the polarization state and the pump power in the laser cavity. The observed multiple DSs are caused by the cavity pulse peak clamping effect under narrow gain bandwidth conditions. Our experimental results are in good agreement with previous theoretical investigation on dissipative solitons. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first demonstration of such a dissipative soliton fiber laser using ethylene glycol as the SA.

2. Experimental Setup

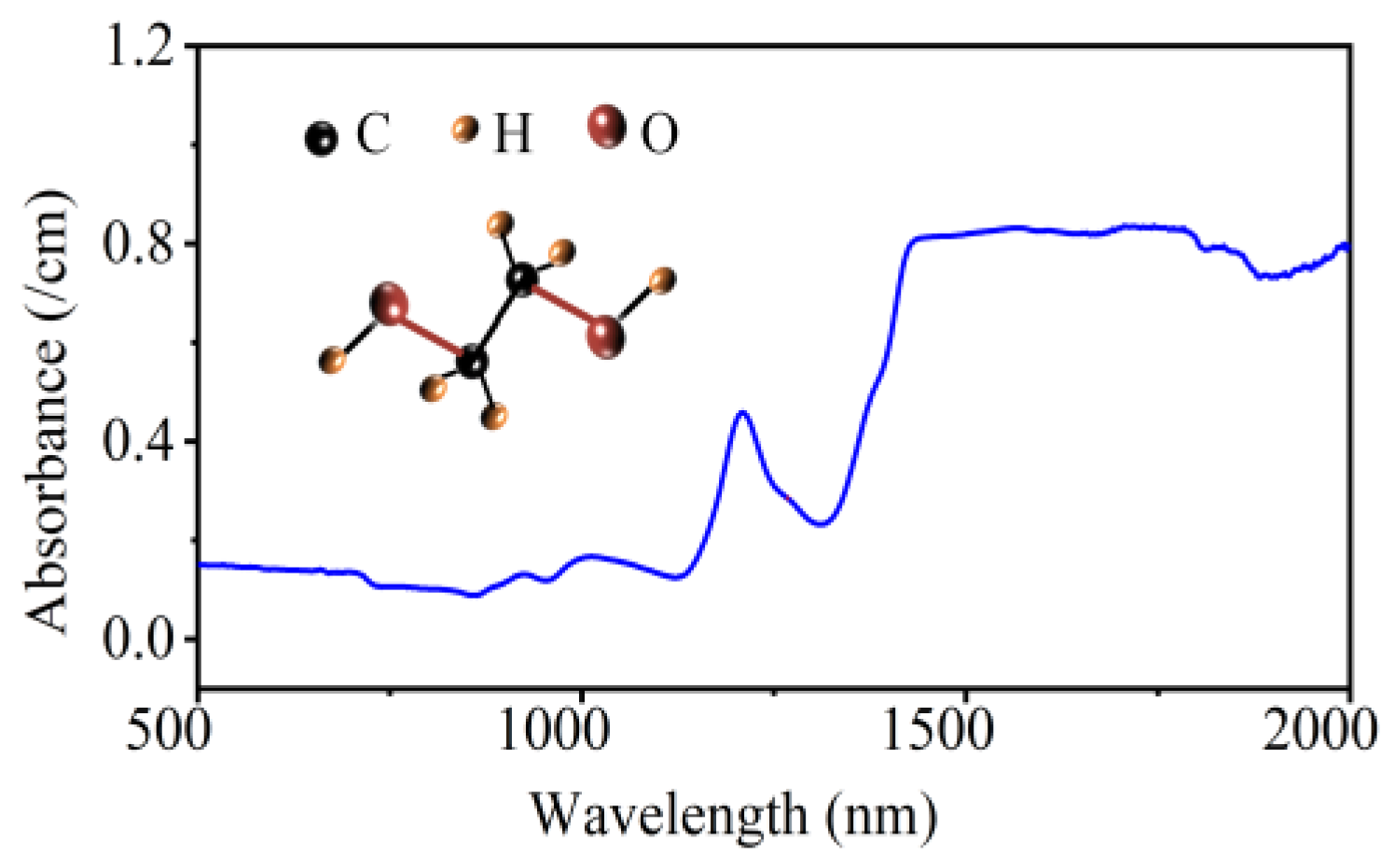

To further investigate the optical properties of ethylene glycol, we measured its absorption spectrum. As illustrated in

Figure 1, ethylene glycol possesses a broad wavelength absorption band, which are attributed to its inherent molecular structure. As shown in the inset, the ethylene glycol molecule includes four covalent bonds: C-H, C-O, C-C, and O-H, the stretching and/or bending vibrations of which result in the broadband absorption characteristics. The absorption near 1500 nm corresponds to the first-order second harmonic generated by the stretching vibrations of O-H and C-H bonds; the absorption around 1800 nm arises from the bending vibrations of O-H bonds; and the strong absorption near 2000 nm originates from the resonant bending vibrations of C-H and O-H bonds. Particularly, the strong absorption of ethylene glycol at 1500 nm makes it possible to achieve Q-switched or mode-locked pulses in erbium-doped fiber lasers. Moreover, the relaxation time of ethylene glycol (resulting from electronic transitions between vibrational energy levels of molecules) is typically in the picosecond scale, less than the cavity round-trip time of pulses (generally on the nanosecond scale), which meets the requirement of mode locking as a saturable absorber.

In addition, as an organic liquid-SA, ethylene glycol-SA likewise has virtues of the high liquidity, effective heat diffusivity, high damage thresholds, cost-effectiveness, and easy fabrication [

26]. Moreover, the stability of ethylene glycol-SA is extremely excellent due to its low volatility, making it an excellent candidate saturable absorber.

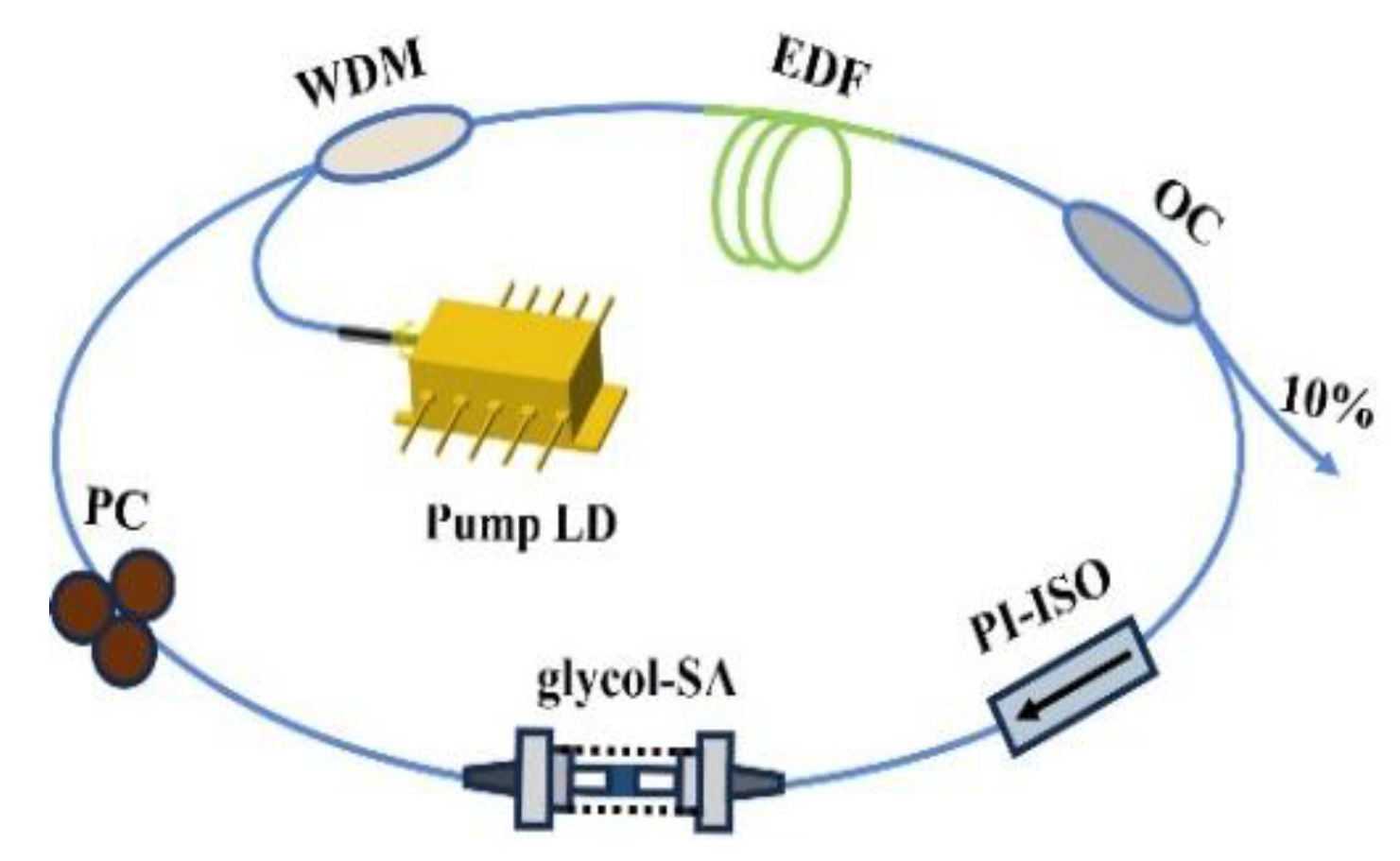

The experimental setup of the mode-locked laser is built as illustrated in

Figure 2. A 2.6m Erbium doped fiber (EDF) (CorActive, EDF-L-1500) with a numerical aperture (NA) of 0.25, a core absorption coefficient of 13.4 dB/m at 980 nm, a peak absorption value of 80 dB/m at 1530 nm and a dispersion parameter of -26 ps/nm/km at 1550 nm, is forward pumped by a 980 nm diode laser. The pump laser with the maximum output power of 500 mW is coupled into the cavity through a 980/1550nm wavelength division multiplexer (WDM). A polarization independent isolator (PI-ISO) is inserted to ensure the unidirectional operation of the laser. A polarization controller (PC) is adopted to adjust the cavity polarization and loss to optimize mode-locking output pulses. A home-made ethylene glycol-SA produced by sandwiching the ethylene glycol between two fiber ferrule connectors is connected between the PI-ISO and the PC. The ethylene glycol-SA possess the superiorities of the wide operation waveband, high damage threshold, cost effective, good stability, and ease of fabrication. Employing a balance detected system (similar as that in Ref.[

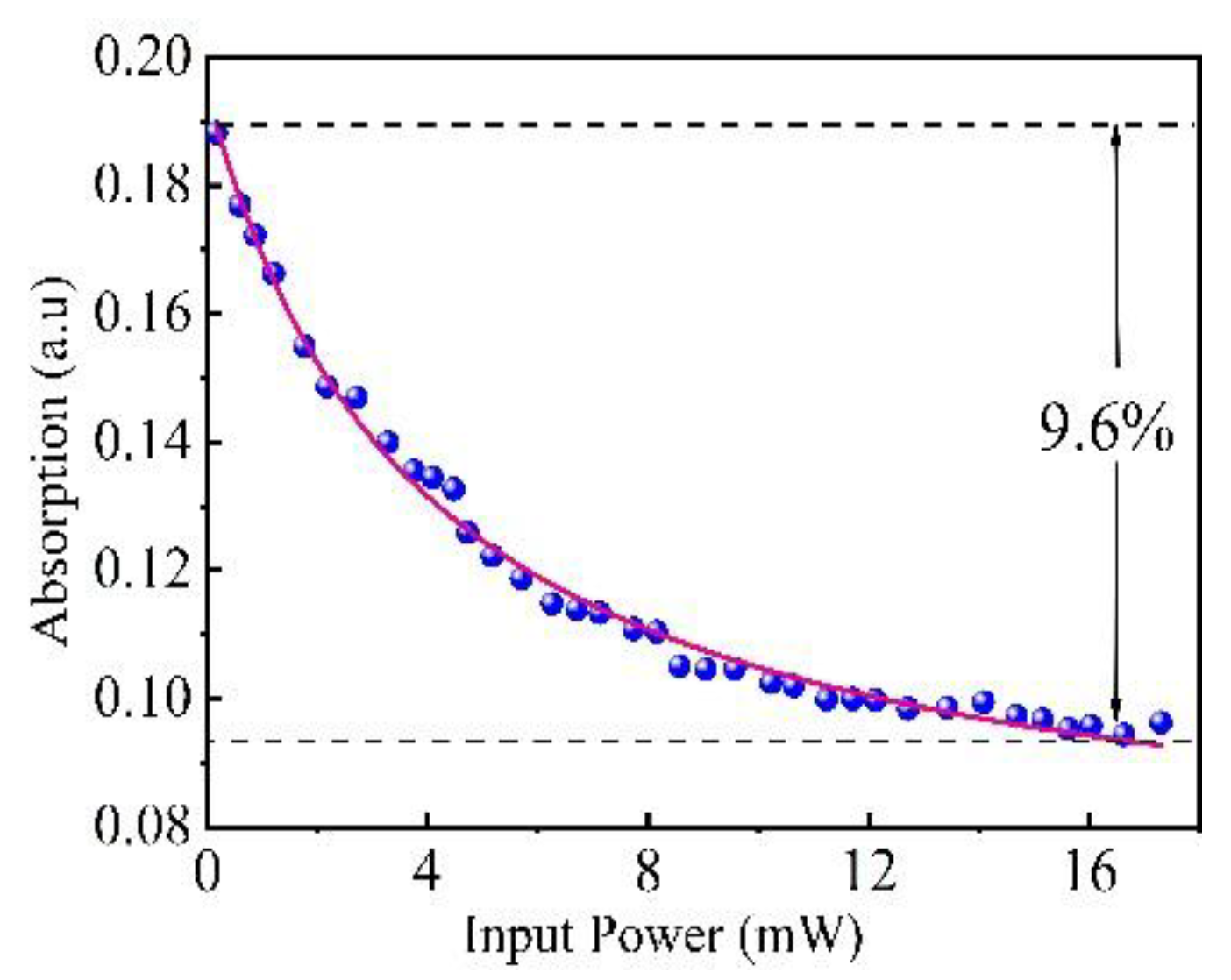

15], the input pulsed laser (Menlo Systems, LAC-1550) centered at the wavelength of 1568.8 nm with the repetition rate of ~50 MHz and the pulse duration of ~200 fs), the nonlinear absorption of ethylene glycol-SA as a nonlinear function of the average pump power is measured. As shown in

Figure 3, the modulation depth is estimated to be ∼9.6%. A 90/10 coupler (OC) with ninety percent is fed back into the cavity to maintain sufficient gain, while 10% output port is monitored to investigate the pulse characteristics by an optical spectrum analyzer (Yokogawa AQ6370D) with a spectral resolution of 0.02 nm, and an oscilloscope (RTO 2022, 2 GHz), a radiofrequency spectrum analyzer (Keysight N9000B) via a high-speed 10 GHz bandwidth photodetector (Newport 818BB-51F).

All the optical components are linked into a ring by splicing their tail fibers, which are standard single-mode fibers (SMFs) with the dispersion parameter of 17 ps/km/nm at 1550 nm. The ring cavity length is around 5.8 m, and the total dispersion is calculated to be 0.017 ps

2 for dissipative soliton mode-locking regime, in which DS can be induced by mutual interaction among dissipative processes deriving from the normal cavity dispersion, fiber nonlinear Kerr effect, gain and loss, and the effective cavity gain bandwidth filtering [

27].

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Single Dissipative Soliton Operation

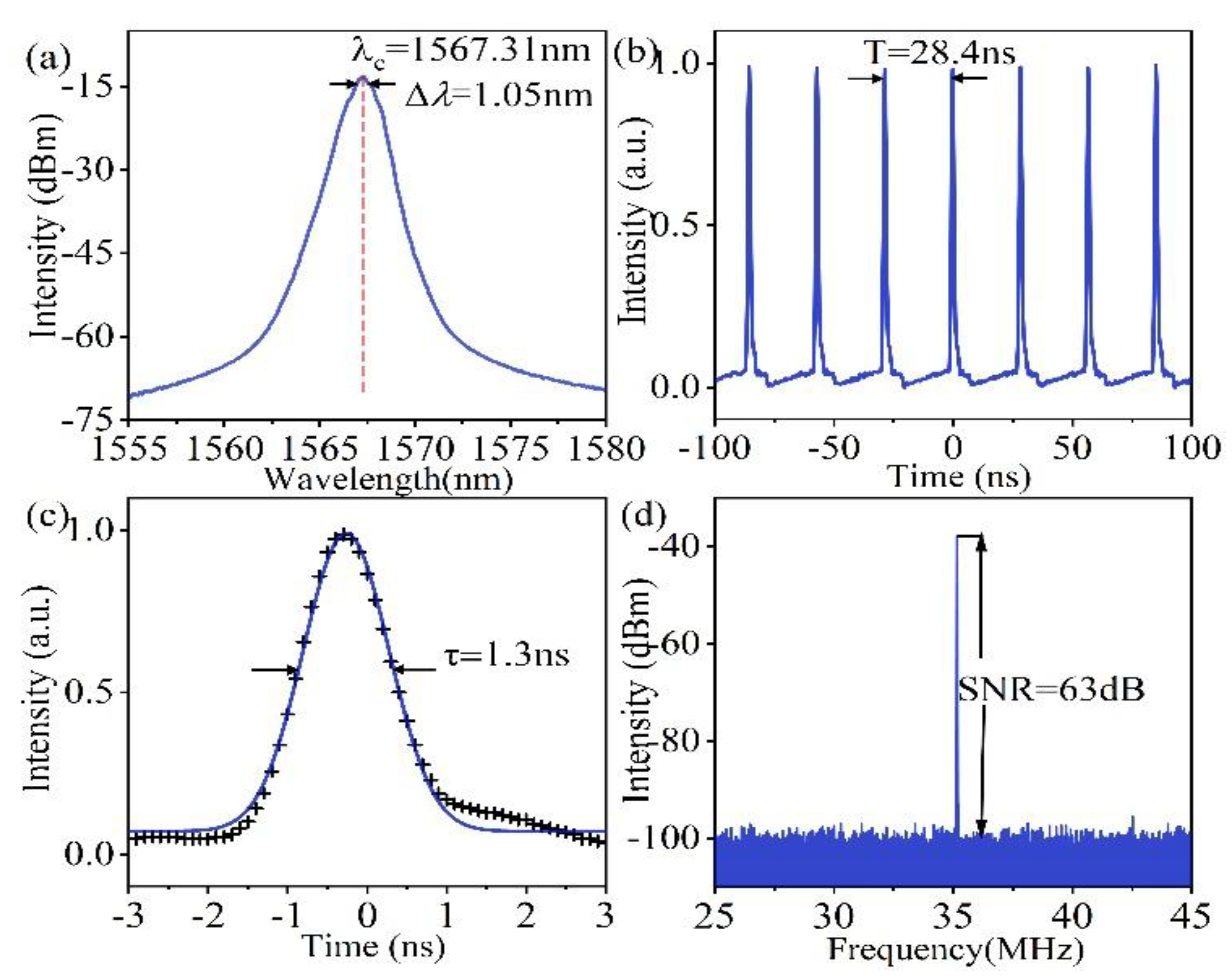

In the proposed laser, when the pump power exceeds a threshold of 100 mW, self-starting mode-locked pulse operation is achieved by careful adjustment of the polarization controller. The characteristics of the stable pulse are demonstrated in

Figure 4. As shown in

Figure 4(a), the optical spectrum displays steep spectral edges, which is universally acknowledged as a generic feature of nonlinear pulse propagation in normal dispersion fiber lasers, indicating that the mode-locked pulses have been successfully shaped to DSs. Notably, different from the typical DSs with rectangular shapes, the optical spectrum displays a bell-like shape with a narrow spectrum width. The central wavelength of the DS is located at 1567.31 nm, with a 3dB spectrum width of 1.05 nm, akin to bandwidths observed in the SESAM mode-locked laser [

28], which is attributed to the narrow bandwidth spectral filtering effect induced by limited gain bandwidth [

29]. Furthermore, this appearance may also originate from the large cavity birefringence or/and the associated birefringence filter effect [

30].Time characteristics of the pulse sequence are displayed in

Figure 4(b). The temporal period of the dissipative pulse is recorded at 28.4 ns, corresponding to the total cavity length of 5.8 m. In addition, we estimate the pulse width by amplifying the profile of a single pulse, due to the absence of an autocorrelator in our laboratory. As present in

Figure 4(c), the full width at half maximum (FWHM) assuming a Gaussian profile is ~ 1.3 ns. Actually, the real pulse duration would be considerably shorter if an autocorrelator were used to evaluate its pulse width. According to the Fourier transform limit, the minimum achievable pulse width is calculated to be 3.4 ps.

Figure 4(d) depicts the radio-frequency (RF) spectrum of the dissipate pulse under a pump power of 225 mW. The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is larger than 60 dB at the fundamental repetition frequency of 35.17 MHz, with a resolution of 2 kHz, conforming that the laser mode-locking operation is highly stable. The laser output power coupled through the 10% optical coupler is about 14.35 mW, resulting in a peak power of around 0.31W. This combination of low peak power and broad pulse width renders such a simple DS laser system an ideal candidate for seed pulse generation in amplification applications.

Particularly, it should be noted that the spectral profiles of the single solitons undergoes a dynamic change at varying pumping levels, exhibiting characteristics such as a parabolic, Π-shaped, or M-shaped morphology.

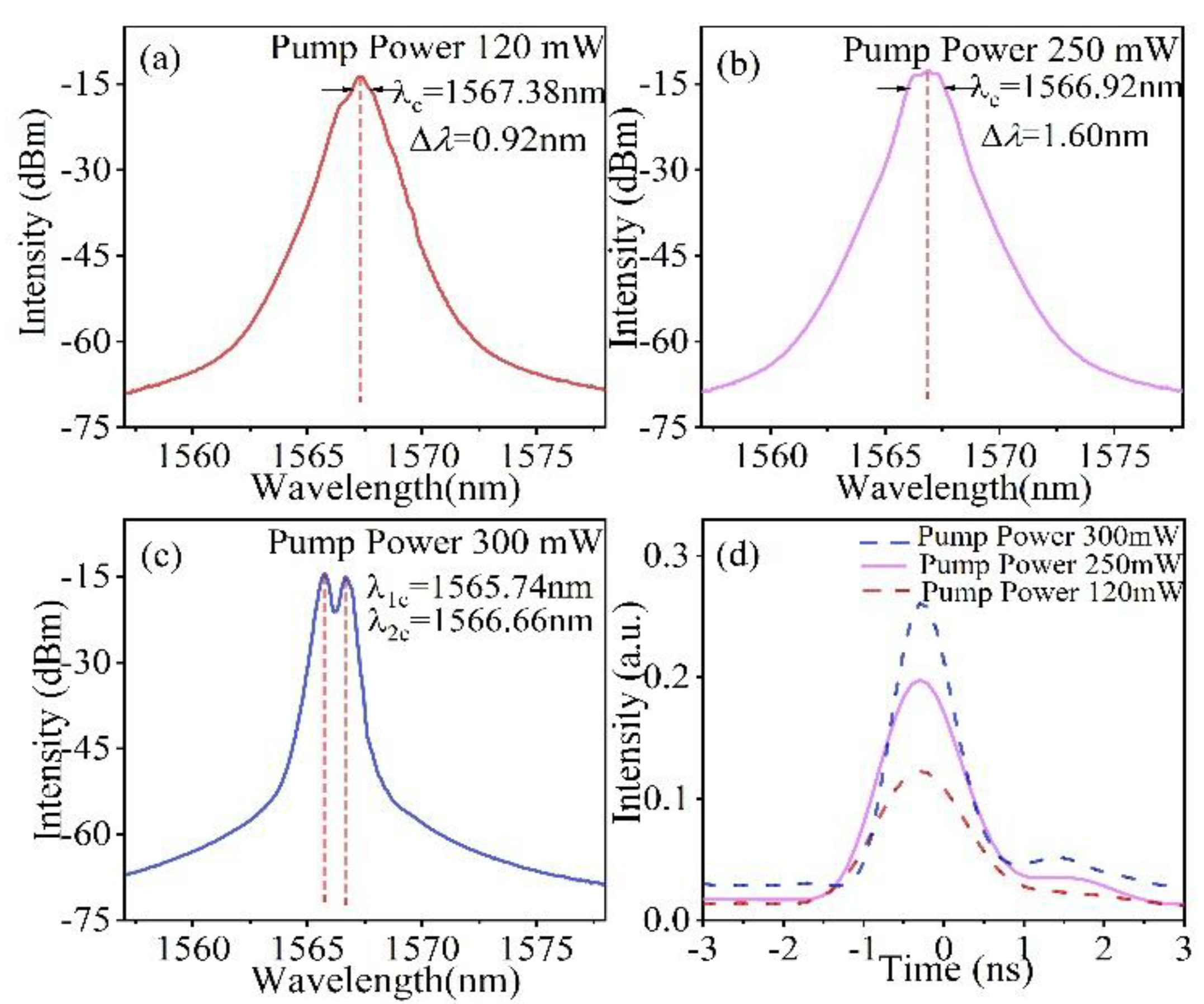

Figure 5 presents the optical spectral evolution under different pump power. As illustrated in

Figure 5(a), (b), and (c), the center wavelength of this mode-locked fiber laser exhibits a blueshift when the pump power is increased from 120 mW to 300 mW. Meanwhile, the 3 dB spectral bandwidth are 0.92, 1.58, and 1.60 nm, respectively, changing in an escalating trend. Peculiarly, at the elevated pump power of 300mW, two prominent spectral lobes emerge, centered at 1565.68 nm and 1566.64 nm. The dynamic variation of the spectrum is attributed to the increase of gain and nonlinear effects caused by the increasing pump power, which is completely consistent with the simulation results mentioned in reference [

31].

Remarkably, it should be mentioned that the center wavelength can also be relocated by adjusting the PC; however, in the process described above, we did not modify the direction of the polarization controller. Therefore, the present blueshift with the increased pump power can be ascribed to the enhanced absorption processes in the erbium-doped fiber. Furthermore, the specific output wavelengths are dependent on the length of the gain fibers, the cavity configuration, the pump power, and the pump wavelengths [

32].

Figure 5(d) provides the corresponding pulse shapes variation of the dissipative solitons at different pump power. Increasing nonlinearity induced by the increase of the pump power keeps the temporal pulse profile with higher peaks. Meanwhile, the temporal pulse widths slightly decrease with the increased nonlinearity, agreeing well with the previous work [

31].

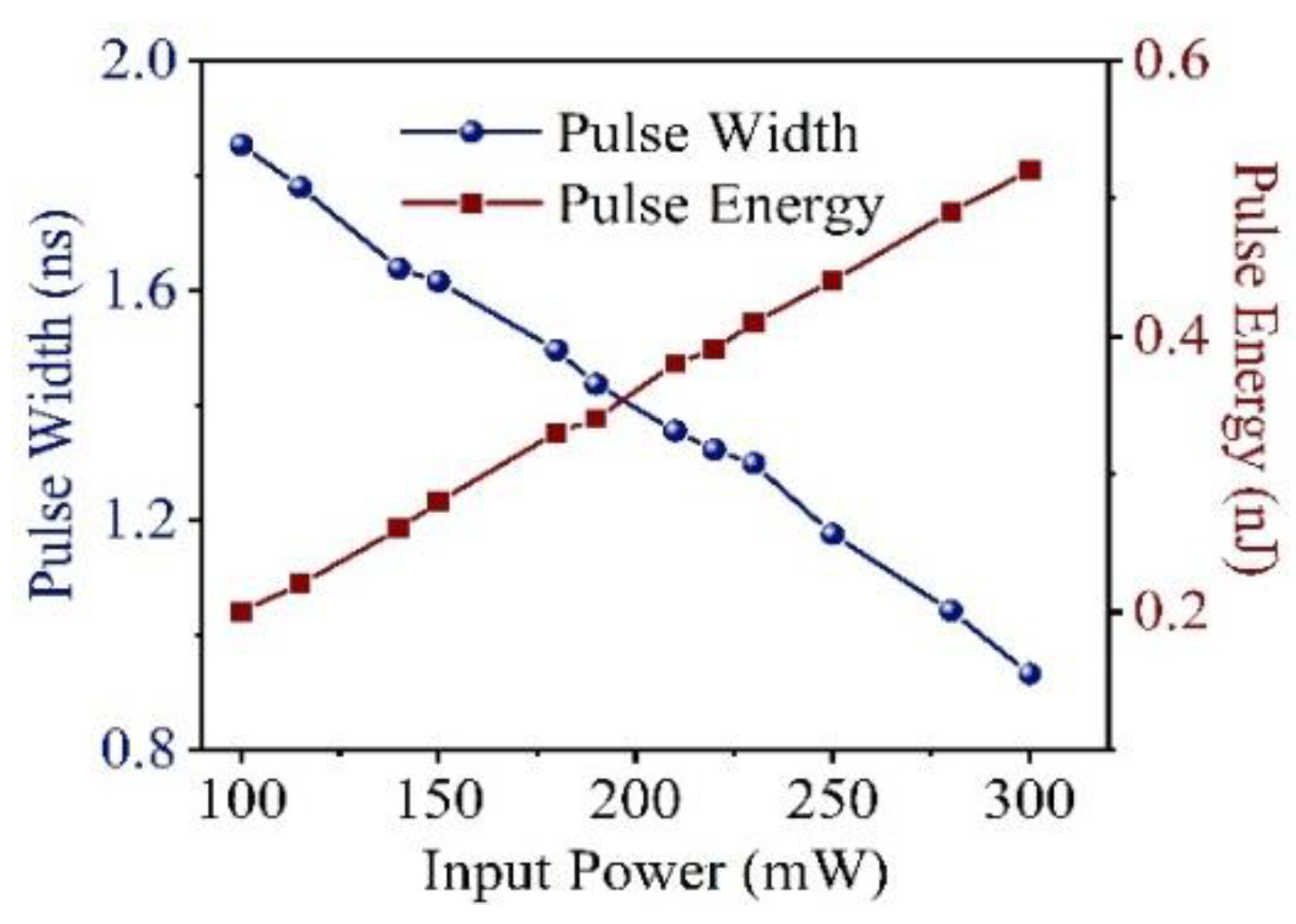

In addition, we also analyze the relationship between the output pulse energy and pulse duration versus the pump power. As depicted in

Figure 6, increasing the pump power from 100 mW to 300 mW results in a reduction of pulse duration from approximately 1.85 ns to 0.93 ns, while the output pulse energy experiences a slight increase from 0.2 nJ to 0.52 nJ. This observed decrease in pulse duration with increasing pump power can be primarily attributed to the nonlinear absorption effects of the ethylene glycol saturable absorber, i.e., the higher the pulse intensity, the higher the transmittance.

3.2. Dissipative Soliton Pairs Operation

As mentioned above, stable single dissipative soliton operation can be facilitated in a limited pump power range from 100mW to 300mW. When the pumping intensity dramatically changes beyond this range, the balance required for the formation of single-soliton states is broken, resulting in the emergence of continuous-wave or multi-soliton states [

33].

By deliberately raising the pump power to a level exceeding 300 mW, the single DS becomes more energetic, leading to the formation of oscillatory soliton pairs within the laser cavity.

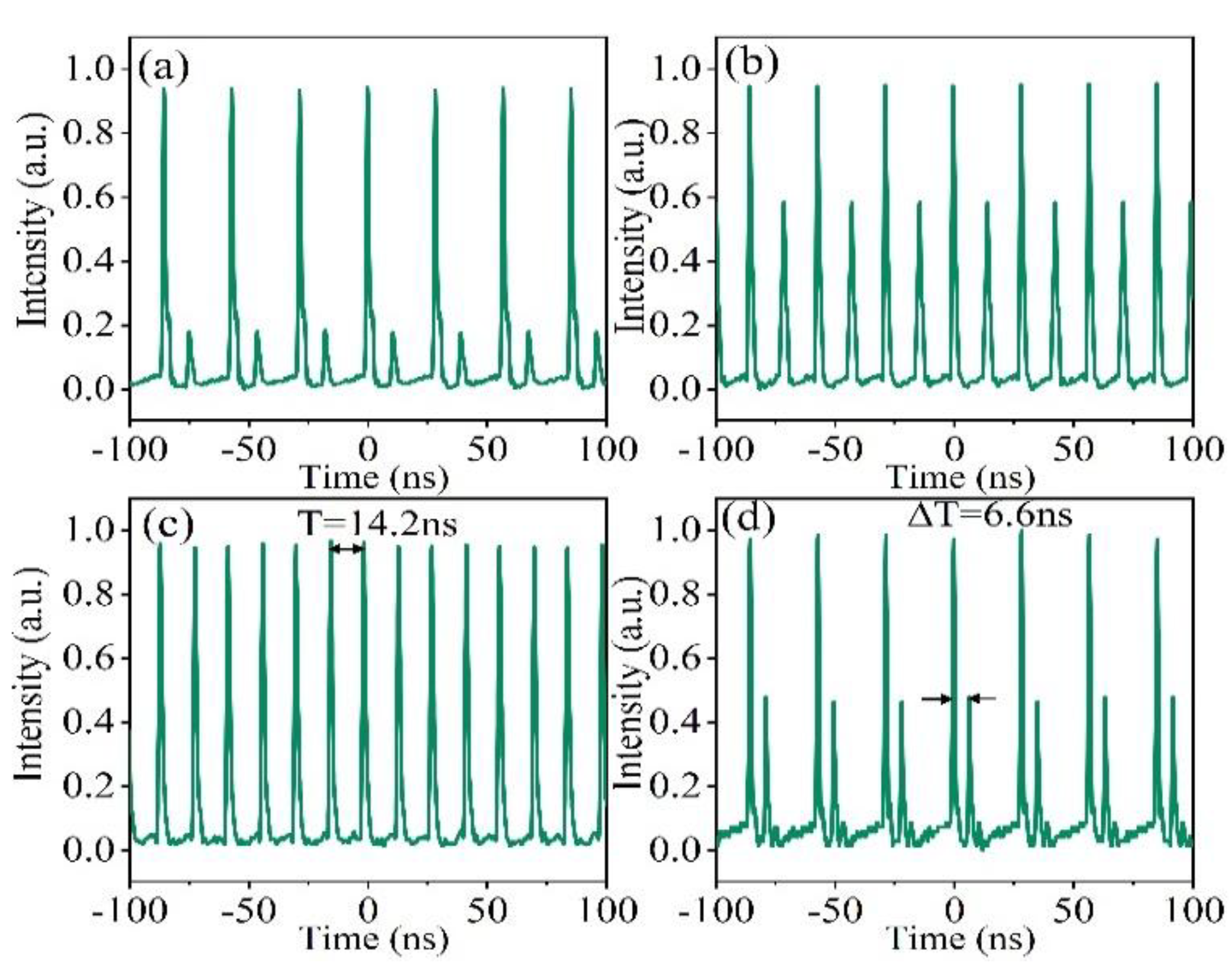

Figure 7 illustrates the time-domain profiles of these oscillating soliton pairs at various instances. As depicted in

Figure 7(a), a weak soliton appears initially on the right side of a single soliton at a pumping power of 305 mW, indicating that a stable asymmetric soliton pair state has been established. In the initial state, without PC regulation, this weak soliton pair oscillates with low intensity and slow speed; when the pumping power is increased to 345 mW, the weak soliton oscillates with gradually enhanced intensity and the oscillation speed is further strengthened, as shown in

Figure 7(b). The pulsed laser enters the state of oscillating soliton pairs and is transformed into a stabilized soliton pair after a short period of oscillatory shaping of oscillating soliton pairs, and finally a stabilized soliton pair is obtained. As present in

Figure 7(c), further increasing the pump power to 360 mW, the two solitons exhibited identical pulse heights on the oscilloscope alignment, indicating that they possessed the same pulse energy, i.e., as the pump intensity varies, the energies of the two pulses undergo simultaneous changes while maintaining a constant height. This phenomenon bears resemblance to the soliton energy quantization observed in conventional solitons lasers.

Noteworthy, in the whole oscillation process, the instantaneous distance between the main and weaker pulses remains constant. The process of transferring a stable asymmetric soliton pair to an oscillating soliton pair is longer than that of transferring an oscillating soliton pair to a stable soliton pair, indicating that there is a prolonged transient period for mode-locking operations from a stable asymmetric soliton pair to a subsequent stable soliton pair. Ultimately, the increased gain induced by the pumping parameter facilitates the formation of symmetric oscillating soliton pairs, and the higher the gain, the more the oscillations decay and the symmetric soliton pairs remain stable [

34]. In addition, the separation between the adjacent pulses can be changed by slightly adjusting the orientation of the PC. As described in

Figure 7(d), another stable asymmetric soliton pair chain with different separation is observed when we fine-tune the PC’s direction under the constant pump power.

3.3. Dissipative Soliton Triplets’ Emission

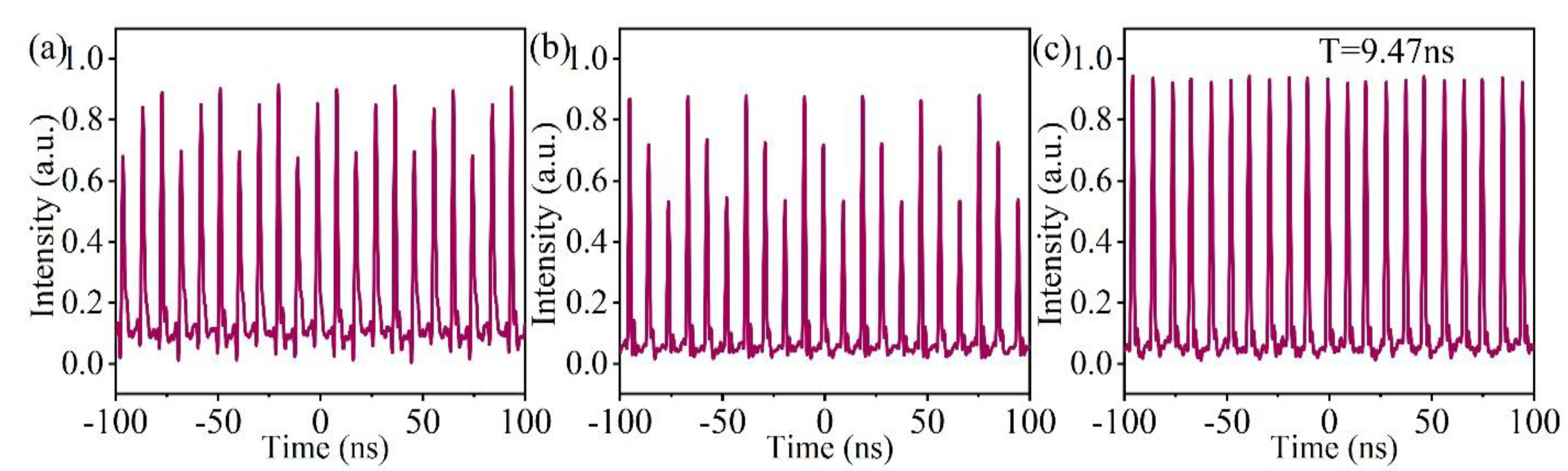

Furthermore, similar scenarios are also appeared for soliton triplets at elevated pumping parameters. When the pump power surpasses the two-soliton stability threshold of 420 mW, a third weak soliton is incorporated into the soliton pair, thereby establishing a soliton triplet state. As illustrated in

Figure 8(a) and 8(b), stable asymmetric soliton triplets and oscillating soliton triplets are achieved within the pumping scope of 420.5-435mW and 435-450mW, severally. When the pumping parameter is further increased, the energies of the three solitons are found to be approximately equal, and a stable triplet is generated under suitable polarization, whose characteristics is presented in

Figure 8(c). The observation of soliton triplets is qualitatively similar to that of soliton pairs, which can be concluded that a weak soliton acquires energy through the interaction of the soliton pair; once the pump power is continuously increased, the laser begins to work in an oscillating soliton triplet regime; following a brief interval, the oscillating soliton triplet transfers into a stable soliton triplet.

For the formation of the multiple dissipative solitons, it is contributed to the soliton shaping of dispersive waves [

33,

34], which is different from soliton energy quantization effect inducing the multi-soliton generation in negative dispersion laser. As the pump strength is elevated, the soliton peak intensity increases; ultimately, the soliton peak is constrained by the cavity, which means that the peak-power-clamping effect is activated by the limited gain bandwidth and the saturable absorption of the ethylene glycol. Further increases in pump strength serve not to amplify the soliton itself, but the background dispersive waves. Rather than a noise-like wave being formed, the background dispersive waves are rapidly shaped into a new DS, which then gives rise to the multiple dissipative solitons.

Moreover, in order to confirm that the mode-locking of multiple DS fiber laser is indeed caused by the glycol saturable absorber, we purposely eliminated the glycol-SA from the laser cavity. Subsequently, the pulse train was no longer observed any more, and there were no indications of mode-locking. This results substantiate the pivotal role of the glycol-saturated absorber in the generation of dissipative soliton operation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first observation of a positive dispersion fiber laser adopting ethylene glycol as an SA, wherein both single dissipative soliton and multiple dissipative solitons (including soliton pairs and soliton triplets) have been generated. The observation corroborates the effectiveness of the ethylene glycol-SA in soliton operation, which possesses great potential in ultrashort pulse lasers.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, we demonstrate a passively mode-locked fiber laser utilizing an ethylene glycol saturable absorber, operating in the net-normal-dispersion regime. Through meticulously adjusting the polarization state within the cavity, stable DSs are manifested. The generated single DS exhibits a center wavelength of 1567.31 nm, a 3 dB bandwidth of 1.05 nm, a repetition rate of 35.17 MHz, a pulse width of 1.3 ns, and an SNR of 63 dB. With an increase in pump power from 100 mW to 300 mW, the variation in the spectral profile of the individual solitons are induced, assuming either a parabolic-like, Π-like, or M-like shape. Moreover, further increasing the pump power results in the emergence of multiple DSs, involving soliton pairs and soliton triplets, which originates from the pulse peak clamping effect within the cavity. Our experimental results highlight the potential of ethylene glycol as an effective saturable absorber for passively mode-locked fiber lasers working in diverse soliton regimes

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W. Z. and H. J.; methodology, W.Z. and L. Z.; validation, H. J. and N. L.; writing- original draft preparation, W.Z.; writing-review and editing, W.Z.; supervision, L. Z. and K. Y.; project administration, K.Y.; funding acquisition, W.Z. and Y. K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (62105296, 62305209); Henan Provincial Science and Technology Research Project (252102220036, 242102210145); the Key Research Project of Higher Education Institutions of Henan Province (26A510020); Youth backbone Project of Zhengzhou University of Light Industry.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Keller, U. Recent developments in compact ultrafast lasers. Nature 2003, 424, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley J., M.; Finot, C.; Richardson D., J.; Millot, G. Self-similarity in ultrafast nonlinear optics. Nat. Phys. 2007, 3, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang W., Y.; Xian T., H.; Wang W., C.; Zhan, L. Advancement and expectations for mode-locked laser gyroscopes. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2022, 39, 3159–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng J., S.; Zhao Z., H.; Boscolo, S.; Finot, C.; Sugavanam, S.; Churkin D., V.; Zeng H., P. Breather Molecular Complexes in a Passively Mode-Locked Fiber Laser. Laser Photonics Rev. 2021, 15, 2000132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao C., X.; Wang Z., Q.; Luo, H.; Zhan, L. High Energy All-Fiber Tm-Doped Femtosecond Soliton Laser Mode-Locked by Nonlinear Polarization Rotation. J. Lightwave Technol. 2017, 35, 2988–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang C., C.; Wang, P. Harmonic Dissipative Soliton Resonance in an Er/Yb Co-Doped Fiber Laser Based On SESAM. J. Lightwave Technol. 2022, 40, 5958–5966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo H., Y.; Hou, L.; Wang Y., G.; Sun, J.; Lin Q., M.; Bai, Y.; Bai J., T. Tunable Ytterbium-Doped Mode-Locked Fiber Laser Based on Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. J. Lightwave Technol. 2019, 37, 2370–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, K.; Wang D., N. Coupling scheme for graphene saturable absorber in a linear cavity mode-locked fiber laser. Opt. Lett. 2021, 46, 4362–4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing X., W.; Liu Y., X.; Han J., F.; Liu W., J.; Wei Z., Y. Preparation of High Damage Threshold Device Based on Bi2Se3 Film and Its Application in Fiber Lasers. ACS Photonics 2023, 10, 2264–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu Y., H.; Zhang, H.; Wu Z., J.; Gu Q., Q.; Wang S., T.; Deng G., L.; Zhou S., H. The dispersion management of passively mode-locked all-fiber lasers based on the Co2+: ZnS-film. Opt. Laser Technol. 2022, 155, 108368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang W., C.; Wang, J.; Wu, J.; Hou T., Y.; Ma P., F.; Su R., T.; Ma Y., X.; Peng J., S.; Zhan, L.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, P. Bright/dark switchable mode-locked fiber laser based on black phosphorus. Opt. Laser Technol. 2020, 123, 105948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu N., N.; Ma P., F.; Fu S., G.; Shang X., X.; Jiang S., Z.; Wang S., Y.; Li D., W.; Zhang H., N. Tellurene-based saturable absorber to demonstrate large-energy dissipative soliton and noise-like pulse generations. Nanophotonics 2020, 9, 2783–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafiso S. D., D.; Ugolotti, E.; Schmidt, A.; Petrov, V.; Griebner, U.; Agnesi, A.; Cho W., B.; Jung B., H.; Rotermund, F.; Bae, S.; Hong B., H.; Reali, G.; Pirzio, F. Sub-100-fs Cr:YAG laser mode-locked by monolayer graphene saturable absorber. Opt. Lett. 2013, 38, 1745–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, B.; Yao, Y.; Yan P., G.; Xu, K.; Liu J., J.; Wang S., G.; Li, Y. Dual-Wavelength Soliton Mode-Locked Fiber Laser with a WS2-Based Fiber Taper. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 2016, 28, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang Z., Q.; Zhan, L.; Wu, J.; Zou Z., X.; Zhang, L.; Qian, K.; He, L.; Fang, X. Self-starting ultrafast fiber lasers mode-locked with alcohol. Opt. Lett. 2015, 40, 3699–3702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang Z., Q.; Zhan, L.; Qin M., L.; Wu, J.; Zhang, L.; Zou Z., X.; Qian, K. Passively Q-Switched Er-Doped Fiber Lasers Using Alcohol. J. Lightwave Technol. 2015, 33, 4857–4861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra-Escamilla, B.; Durán-Sánchez, M.; Posada-Ramírez, B.; Alvarez-Tamayo R., I.; Alaniz-Baylón, J.; Bello-Jiménez, M.; Prieto-Cortés, P.; Kuzin E., A. Passively Q-Switched Thulium-Doped Fiber Laser Using Alcohol. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2018, 30, 1768–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najm M., M.; Al-Hiti A., S.; Nizamani, B.; Arof, H.; Zhang, P.; Yasin, M.; Harun S., W. Passively Q-switched erbium-doped fiber laser with mechanical exfoliation of 8-HQCDCL2H2O as saturable absorber. Optik 2021, 242, 167073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian T., H.; Zhan, L.; Gao L., R.; Zhang W., Y.; Zhang W., C. Passively Q-switched fiber lasers based on pure water as the saturable absorber. Opt. Lett. 2019, 44, 863–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai C., S.; Dong Z., P.; Lin J., Q.; Yao P., J.; Xu L., X.; Chun, G. Passively Q-switched and mode-locked 1.9 μm Tm-doped fiber laser based on pure water as saturable absorber. Acta Phys. Sin. 2022, 71, 174202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang W., Y.; Zhan, L.; Xian T., H.; Gao L., R. Generation of Bright/Dark Pulses in an Erbium-Doped Fiber Laser Mode-Locked with Glycerin. J. Lightwave Technol. 2019, 37, 3756–3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang L., X.; Zhao H., D.; Dai H., L. Passively Q-switching fiber lasers using acetone solution as a saturable absorber. Opt. Eng. 2019, 58, 086107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang W., Y.; Jiang H., J.; Zheng, L.; Liu N., N.; Zhang X., D.; Yang, K.; Zhan, L. Passively mode-locked fiber laser based on ethylene glycol. Results in Phys. 2024, 60, 107670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang D., Y.; Zhao L., M.; Zhao, B.; Liu A., Q. Mechanism of multisoliton formation and soliton energy quantization in passively mode-locked fiber lasers. Phys. Rev. A 2005, 72, 043816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grelu, P.; Akhmediev, N. Dissipative solitons for mode-locked lasers. Nat. Photon. 2012, 6, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang W., Y.; Jiang H., J.; Yang, K.; Liu N., N.; Geng L., J.; Hao Y., Q.; Xian T., H.; Zhan, L. Bright/dark switchable mode-locked fiber laser based on alcohol. Chin. Opt. Lett. 2024, 22, 031403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao L., M.; Tang D., Y.; Zhang, H.; Wu, X.; Bao Q., L.; Loh K., P. Dissipative soliton operation of an ytterbium-doped fiber laser mode locked with atomic multilayer graphene. Opt. Lett. 2010, 35, 3622–3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, N.; Huang C., Y.; Tang Y., L.; Xu J., Q. 12 nJ 2 μm dissipative soliton fiber laser. Laser Phys. Lett. 2015, 12, 055101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, J.; Dai, C.; Xu, L.; Yao, P. Linear cavity dissipative soliton mode-locked laser based on polarization-maintaining fiber structure. Laser Technol. 2024, 48, 153–158. [Google Scholar]

- Peng J., S.; Sorokina, M.; Zeng H., P. Spectral Correlations in Laser Instabilities Beyond Stable Mode Locking. J. Light. Technol. 2021, 39, 6579–6584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelalim M., A.; Logvin, Y.; Khalil D., A.; Anis, H. Properties and stability limits of an optimized mode-locked Yb-doped femtosecond fiber laser. Opt. Express 2009, 17, 2264–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, B.; Gui L., L.; Li, X.; Xiao X., S.; Zhu H., W.; Yang C., X. Generation of 35-nJ Nanosecond Pulse from a Passively Mode-Locked Tm, Ho-Codoped Fiber Laser with Graphene Saturable Absorber. Photonics Technol. Lett. 2013, 25, 1447–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li D., J.; Tang D., Y.; Zhao L., M.; Shen D., Y. Mechanism of Dissipative-Soliton-Resonance Generation in Passively Mode-Locked All-Normal-Dispersion Fiber Lasers. J. Lightwave Technol. 2015, 33, 3781–3787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelalim M., A.; Logvin, Y.; Khalil D., A.; Anis, H. Steady and oscillating multiple dissipative solitons in normal-dispersion mode-locked Yb-doped fiber laser. Opt. Express 2009, 17, 13128–13139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).