1. Introduction

The distributed-order (DO) fractional calculus was discussed for the first time in 1969 in [

1]. It was argued then that the DO derivative is a generalization of fractional and integer-order derivatives. Caputo and others, in [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7] developed what they called the DO calculus. DO differential equations have several uses in the fields of secure communication, image encryption, physics, and circuit implementation [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Aboelenen [

12] proposed a local discontinuous Galerkin finite element approach for DO time, Riesz space-fractional convection-diffusion, and Schrödinger-type problems. In [

13], chaos synchronization of the DO Lorenz model using chaotic masking are presented. Secure communications using DO hyperchaotic masking for a text that consists of symbols, spaces, numbers and alphabets are examined in [

8]. Abed-Elhameed

et. al [

11] introduced a scheme for image encryption based on adaptive synchronization.

The authors of [

14] proposed the complex detuned lasers model as follows:

where,

,

,

,

, the positive real parameters are

a,

b,

c, and

d, the complex conjugate variable is denoted by

and the time derivatives are represented by dots. The state variables

w,

v, and

u in a ring laser system of two-level atoms are related to population inversion, polarization, and electric field amplitude, respectively, as illustrated in [

15]. The dynamics and synchronization characteristics of complex detuned lasers (1.1) were investigated by Mahmoud

et al. [

16], and in this 5-dimensional model [

16] only chaotic attractors were found to exist . A new version of (1.1) which represents a 6-dimensional hyperchaotic model was studied in [

17], where

. Using a novel image cryptosystem for high security, Li

et al. [

18] discussed the 7-dimensional fractional-order hyperchaotic detuned laser model.

The real form of (

1) is written as:

where,

and

are real state variables.

Based on the model (1.2), the fractional-order detuned laser model can be written as:

where,

stands for the Caputo fractional derivative

[

1],

,

and

and

d are the real parameters of model (

3).

In this paper, we focus on what we call the distributed-order hyperchaotic detuned (DOHD) laser model, given as follows:

Extreme multistability and multistability phenomena have recently become very important in the study of chaotic models. Indeed, multistability frequently appears in nonlinear dynamical systems and denotes the presence of multiple attractors for the same set of model parameters [

19]. Additionally, this phenomenon is often referred to as extreme multistability when an infinite number of attractors coexist for the same set of model parameters [

20]. An enhanced two stable node-foci example of Chua’s circuit was investigated and the model’s multistability was examined in [

21]. In [

22], coexisting chaotic attractors, as well as periodic and point attractors were studied in a new 4D smooth chaotic model. Chen [

23] discovered many kinds of coexisting behaviors, such as coexisting chaotic and periodic attractors, chaotic attractors and singular degenerate heteroclinic cycles, different kinds of periodic attractors, as well as periodic attractors and singular degenerate heteroclinic cycles. Moreover, the phenomenon of extreme multistability, with an infinite number of hidden attractors was investigated in a novel memristive hyperchaotic model in [

24]. Mengxin

et al. [

25] also observed the phenomenon of extreme multistability in a complex simplified Lorenz model with integer-order derivatives. Finally, a logarithmic memcapacitor model was comprehensively investigated with coexisting attractors and multistable coexisting oscillations in [

26].

The synchronization of hyperchaotic (or chaotic) models is an essential branch of nonlinear dynamics research. It has been thoroughly studied in a number of areas, such as circuit implementation [

11], neural networks [

27], color image encryption [

9] and secure communications [

8]. Many types of synchronization, including complete synchronization [

7], projective synchronization [

27], adaptive synchronization [

11] and generalization of combination synchronization [

9] were investigated for DO models. A scheme to examine the generalization of combination-combination synchronization among two fractional-order and two DO hyperchaotic models was introduced in [

28].

In this article, we present the dynamics and numerical solutions of the DOHD laser model (1.4) for the first time. The coexistence of several attractors with the same parameter set but different initial conditions is investigated, while we also study the dual combination synchronization (DCS) for integer and DO hyperchaotic models. Other types of synchronization can also be studied, as particular cases of the suggested DCS phenomenon, as noted in literature. Here, using the tracking control technique [

29], we present schemes for the DCS with four drive and two response integer and distributed-order models, respectively. To derive analytical formulas for control functions, we formulate and prove a new theorem. A particular case is provided to demonstrate how well the numerical and analytical results agree with each other. To this end, we applied here the modified Predictor-Corrector approach [

7] to obtain our numerical results.

The format of this article is as follows: A preliminary introduction and an application of the Caputo fractional derivative to our model are given in

Section 2 and

Section 3 respectively. Next, the dynamical properties and Lyapunov exponents (LEs) of the proposed model (1.4) are calculated in

Section 4.

Section 5 contains the numerical simulations of the multistability phenomenon for a model with various coexisting attractors. A scheme to achieve the DCS using the tracking control technique is investigated in

Section 6. Furthermore, a particular case is provided to demonstrate the validity of the generated analytical control functions. Our overall conclusions are described in the final section.

3. Preliminaries

In this section, we provide definitions, lemmas and a theorem [

1,

7,

33] for our analysis of the DO derivative, which constitute the fundamental ideas of the paper.

Definition 1.

[1] For any For the function , the Caputo fractional derivative is defined as follows:

Definition 2.

[33] The distributed derivative of any continuous function is:

where, , .

Theorem 3.1.

[7] Assume that a dynamical system with DO on several terms of our fractional-order model is given by:

where, and let represent the eigenvalues of , if

where, f contains the nonlinear terms of our model, J is constant matrix, so that , , I is the identity matrix and is the number of steps for . It follows that (3.3) has a zero solution that is asymptotically stable.

Lemma 3.1.

[6] Assume that a Lyapunov function exists that satisfies

where and . Thus, is Mittag-Leffler stable, where is a FP for the DO model (3.3). If these assumptions hold globally on , then is globally Mittag-Leffler stable.

Lemma 3.2.

[6] Let is differentiable function, then

where, T denotes the transpose operation.

6. A Scheme for DCS Between Integer and Distributed-Order Hyperchaotic Models

The DCS of n-dimensional hyperchaotic integer-order and DO dynamical systems with four drive and two response models are introduced in this part. For the drive models, we need one pair of two integer-order hyperchaotic models, and for the response models, we need another pair of DO hyperchaotic models.

Let the drive models be:

and

where, the state vectors of drive models (6.1,6.2) are

,

,

,

and the four continuous vector functions

,

,

,

.

Models (6.1,6.2)) can be expressed as

and

where,

,

,

and

.

These are the equivalent of one pair of two response models:

where,

,

is the state vectors of the response models (6.5),

and

are continuous vector functions and

,

are two control functions of the response models (6.5).

Models (6.5) can be expressed in vector form as:

where,

,

and

.

Definition 3.

Given that three non-zero constant diagonal matrices and S in exist, such that

then the drive models (6.3-6.4) are said to be in DCS with the response models (6.6), where the synchronization error is , while the matrix norm is .

Remark 6.1. Equation (6.7) implies combination synchronization [17] if the response models are integer-order.

Remark 6.2. Additional synchronization kinds, such as projective [34], modified projective [35,36], and complete synchronization [37], may be considered as particular cases of (6.7).

Assume the following for the control function

:

with the the compensation control

described as:

The vector of the control function

will be defined below.

Theorem 6.1.

The drive models (6.3-6.4) and response model (6.6) may perform the DCS, if the control function vector is constructed as follows:

where, a positive-definite diagonal gain matrix and .

Proof. Multiplying Equation (6.6) by

S gives

which implies that

Suppose now that the compensation control has the form:

and hence that model (6.12) becomes:

The result of substituting equation (6.15) into equation (6.14) gives

If

K is chosen so that Theorem 6.1 is satisfied, then

as

. So, DCS among one response model (6.7) and two drive models (6.3-6.4) can be performed. □

6.1. A Special Case

Using four integer-order and two DO detuned laser models as drive and response models, respectively, the control functions (6.15) are calculated numerically as an example to achieve the DCS. The four drive models are:

and

the two associated response models are

where, the control functions of the response models (6.19) are

and .

We noe choose , , and . In like manner other choices of T, R, S and K can be studied.

Using Theorem 6.1, we may now generate the control function matrix as:

where,

Equation (6.10) yields the error model (6.16) as:

where,

In order to achieve the DCS between the four drive models (6.17-6.18) and the two response models (

33), numerical solutions are performed using the control functions (6.20). The initial conditions of the drive models (6.17-6.18) and the response models (6.19) are, respectively,

, , and

. Selecting

,

,

and

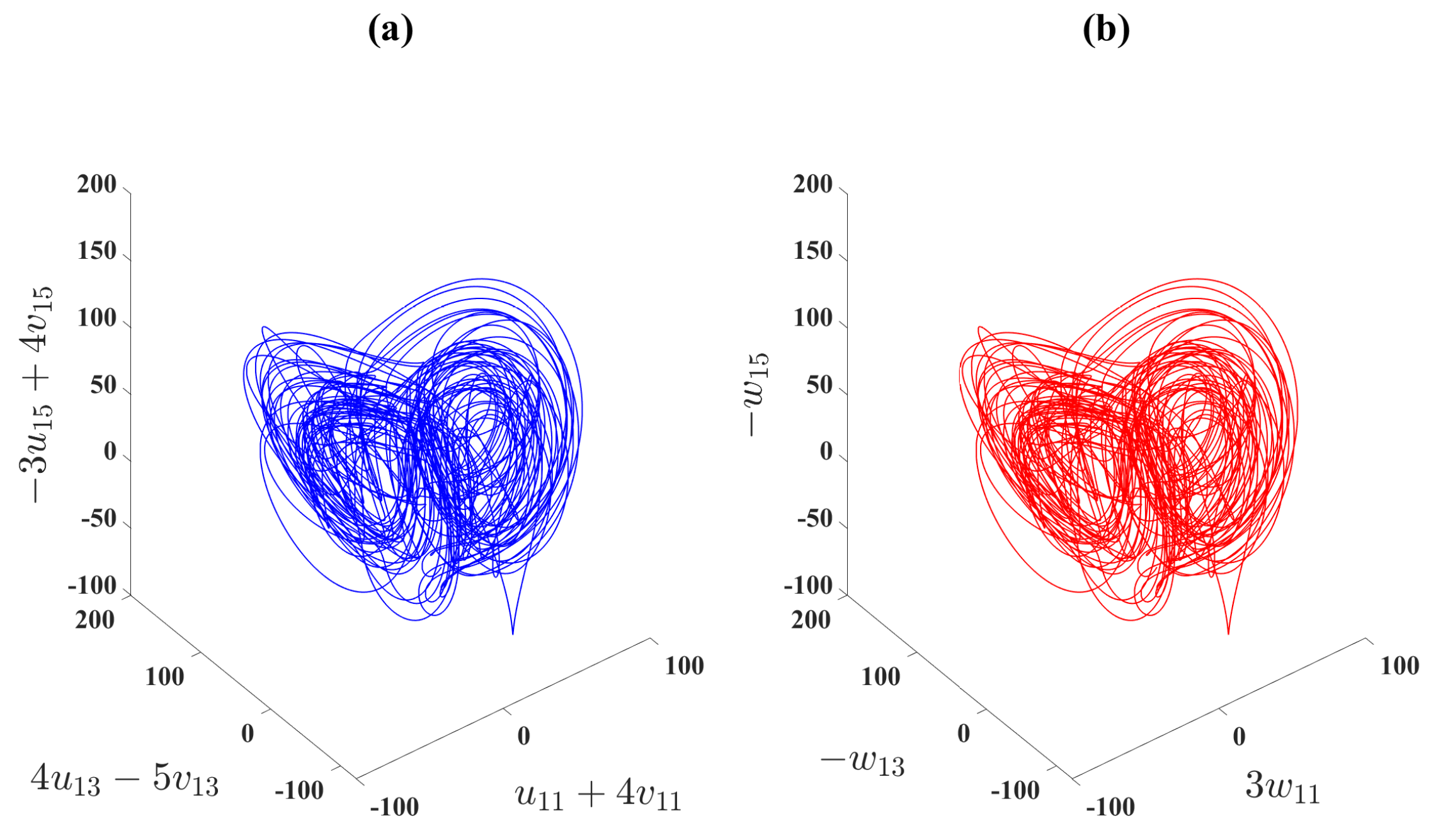

, the results of DCS of models (6.17–6.19) are depicted in

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

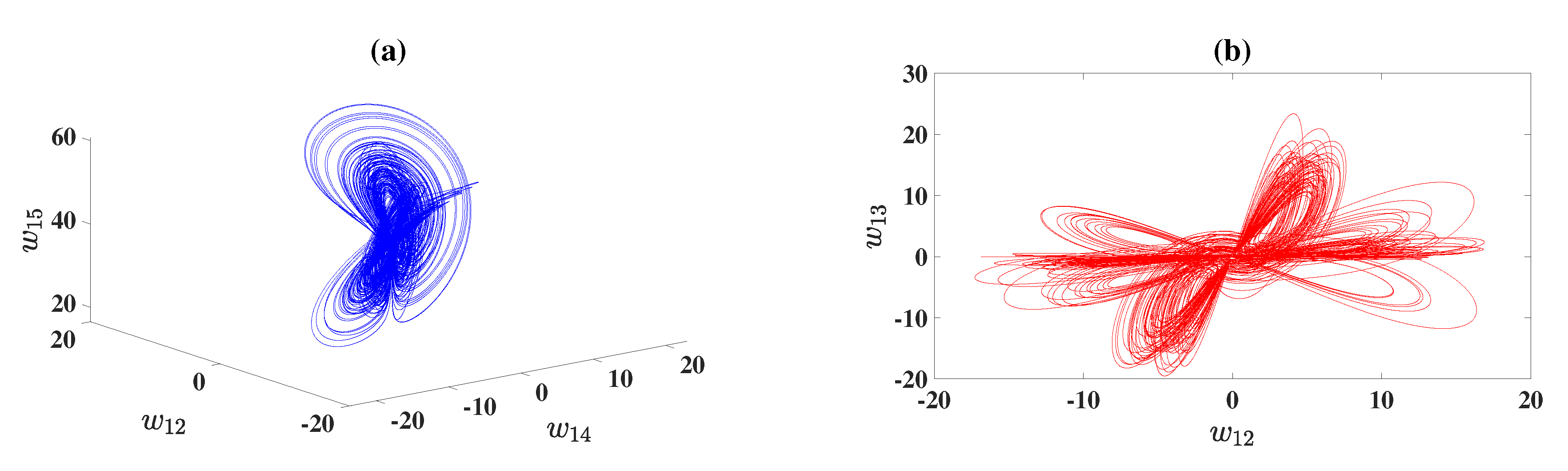

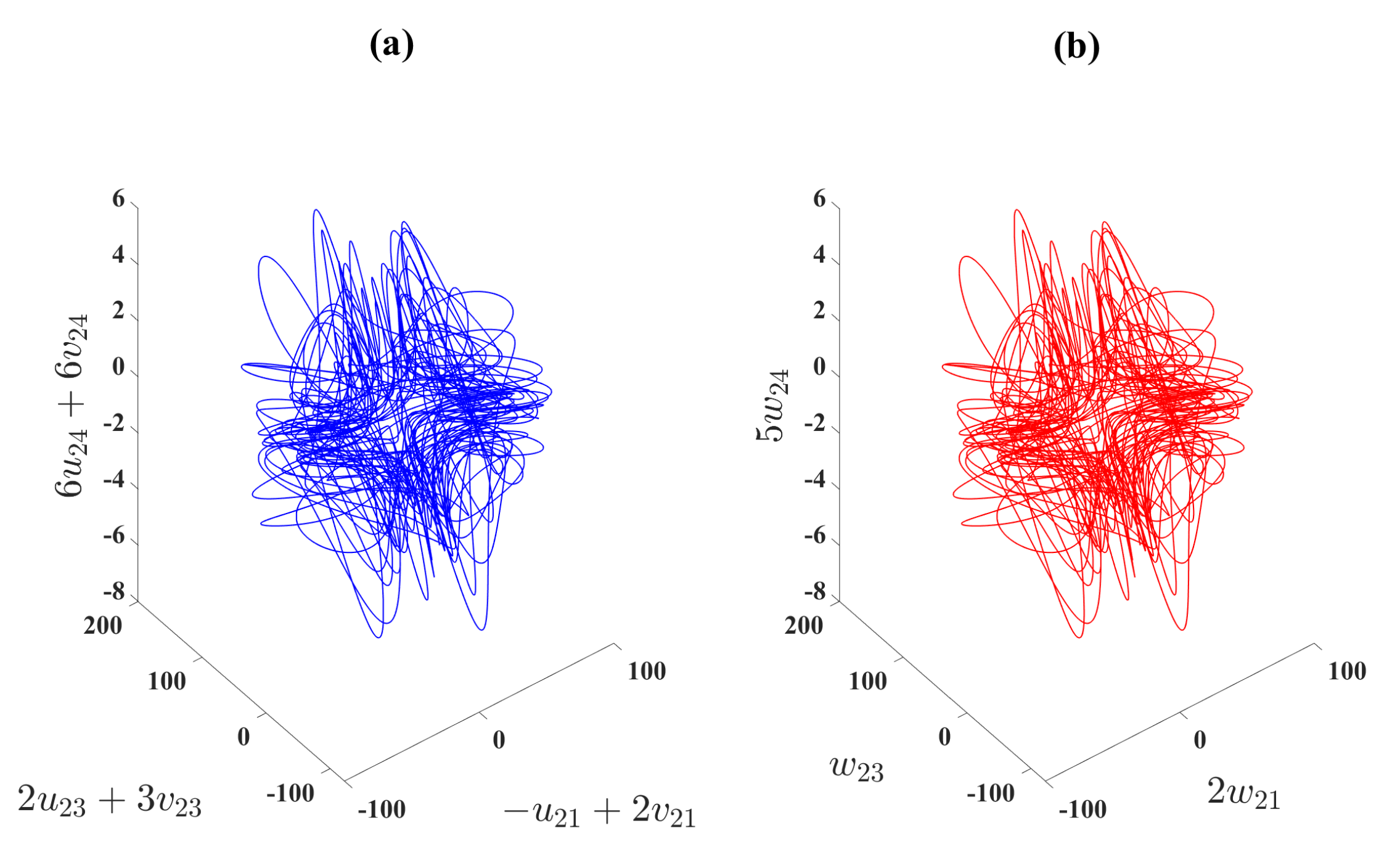

Figure 11. The three dimensional projection in the first two drive models of (6.17-6.18) and the first one response model of (6.19) are plotted in

Figure 8:

space and

space. In addition, the three dimensional projection in the second two drive models of (6.17-6.18) and second response model of (6.19) are indicated in

Figure 9:

space and

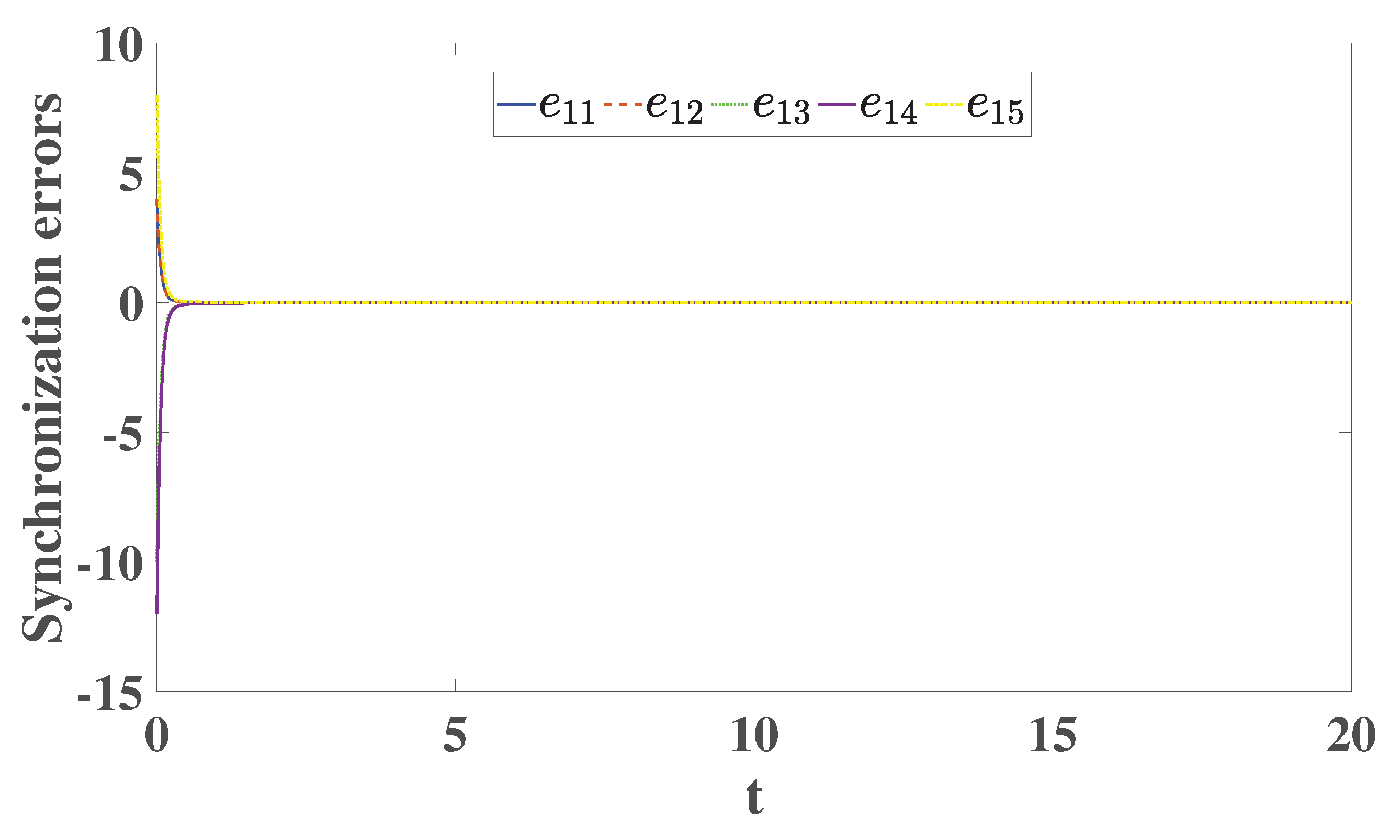

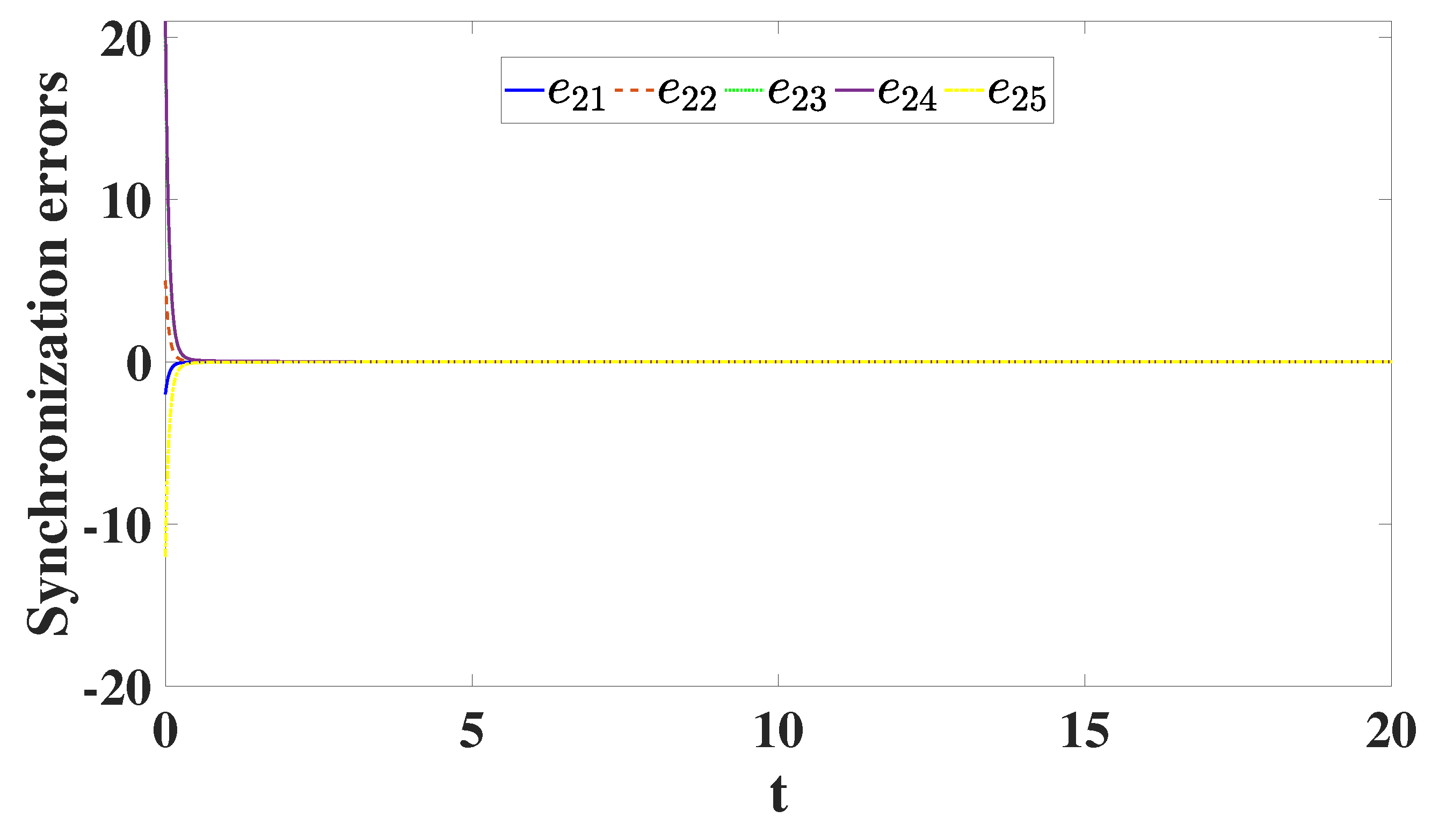

space. This shows that the DCS is performed as suggested by Theorem 6.1. As shown in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11, on the other hand, the synchronization errors

e converge to zero very rapidly as

.

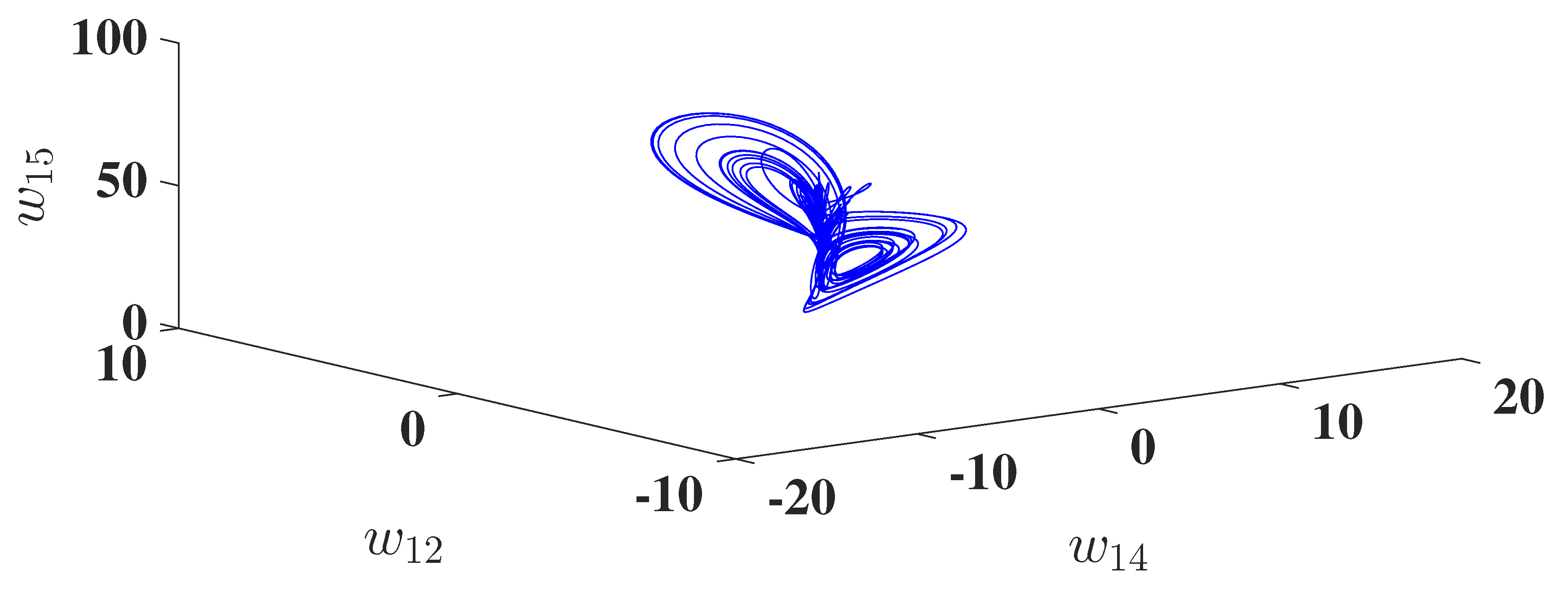

Figure 1.

Chaotic attractors for the fractional order detuned laser model (1.3) for , space.

Figure 1.

Chaotic attractors for the fractional order detuned laser model (1.3) for , space.

Figure 2.

Chaotic attractors for the fractional order detuned laser model (1.3) for , space.

Figure 2.

Chaotic attractors for the fractional order detuned laser model (1.3) for , space.

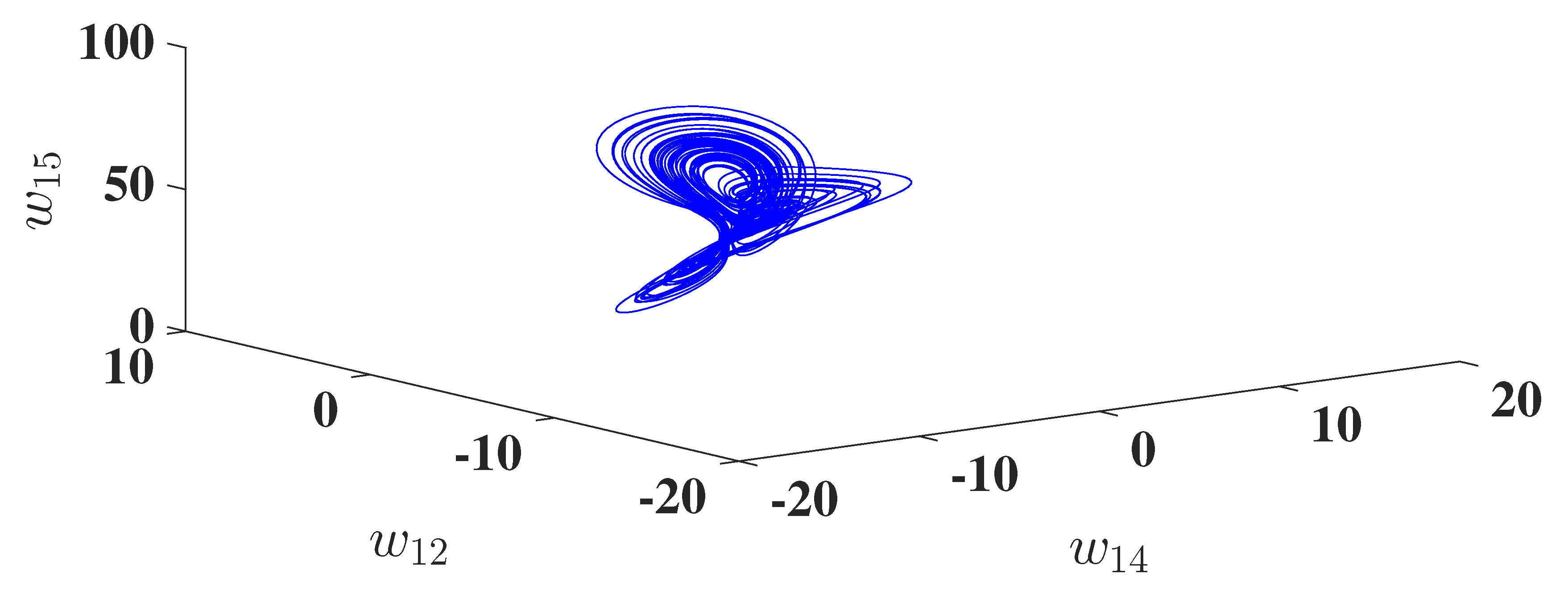

Figure 3.

LEs of the DOHD laser model (1.4), versus t, versus t, , and versus t.

Figure 3.

LEs of the DOHD laser model (1.4), versus t, versus t, , and versus t.

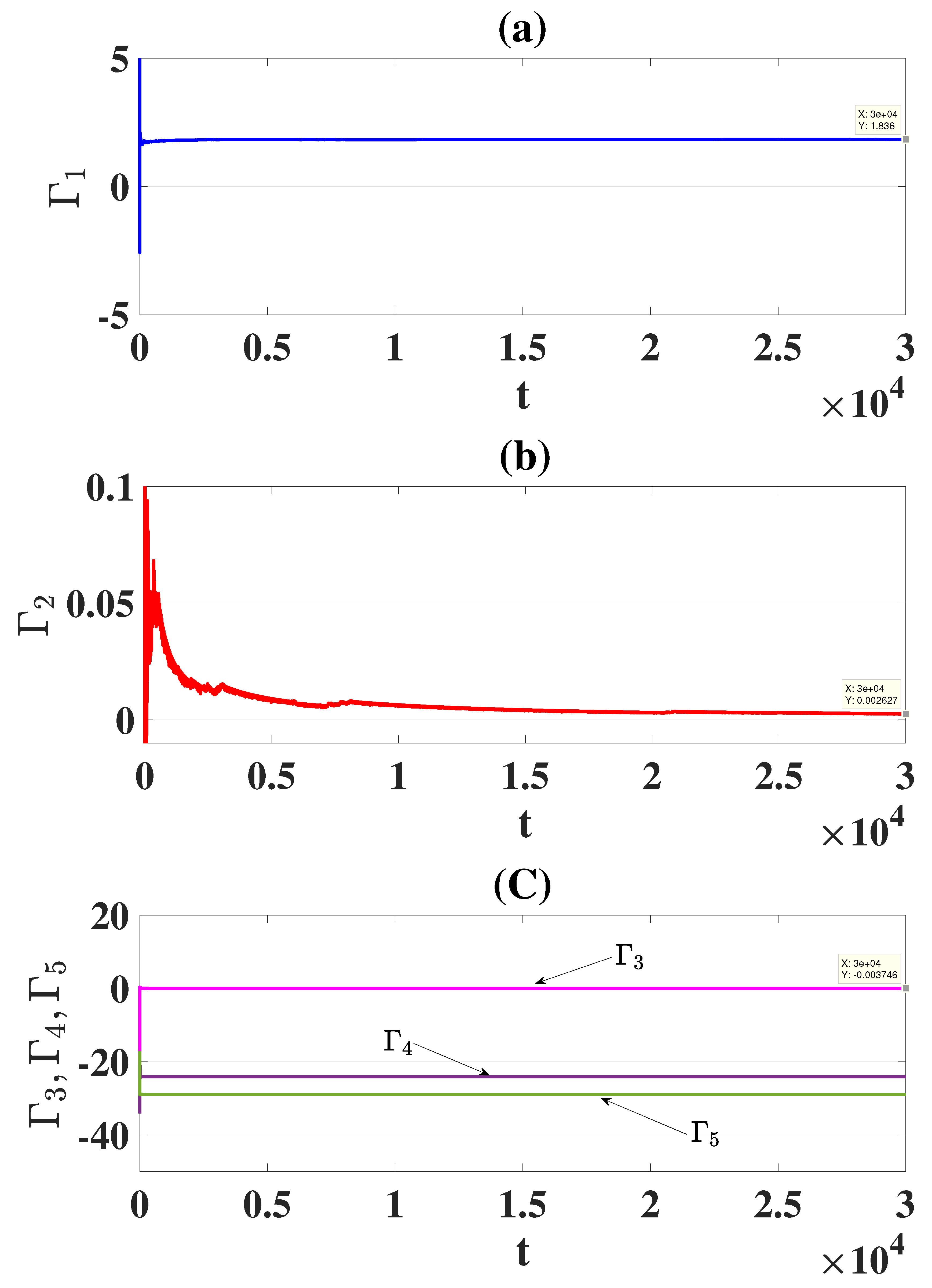

Figure 4.

hyperchaotic attractors for the DOHD laser model (1.4) for , space and space.

Figure 4.

hyperchaotic attractors for the DOHD laser model (1.4) for , space and space.

Figure 5.

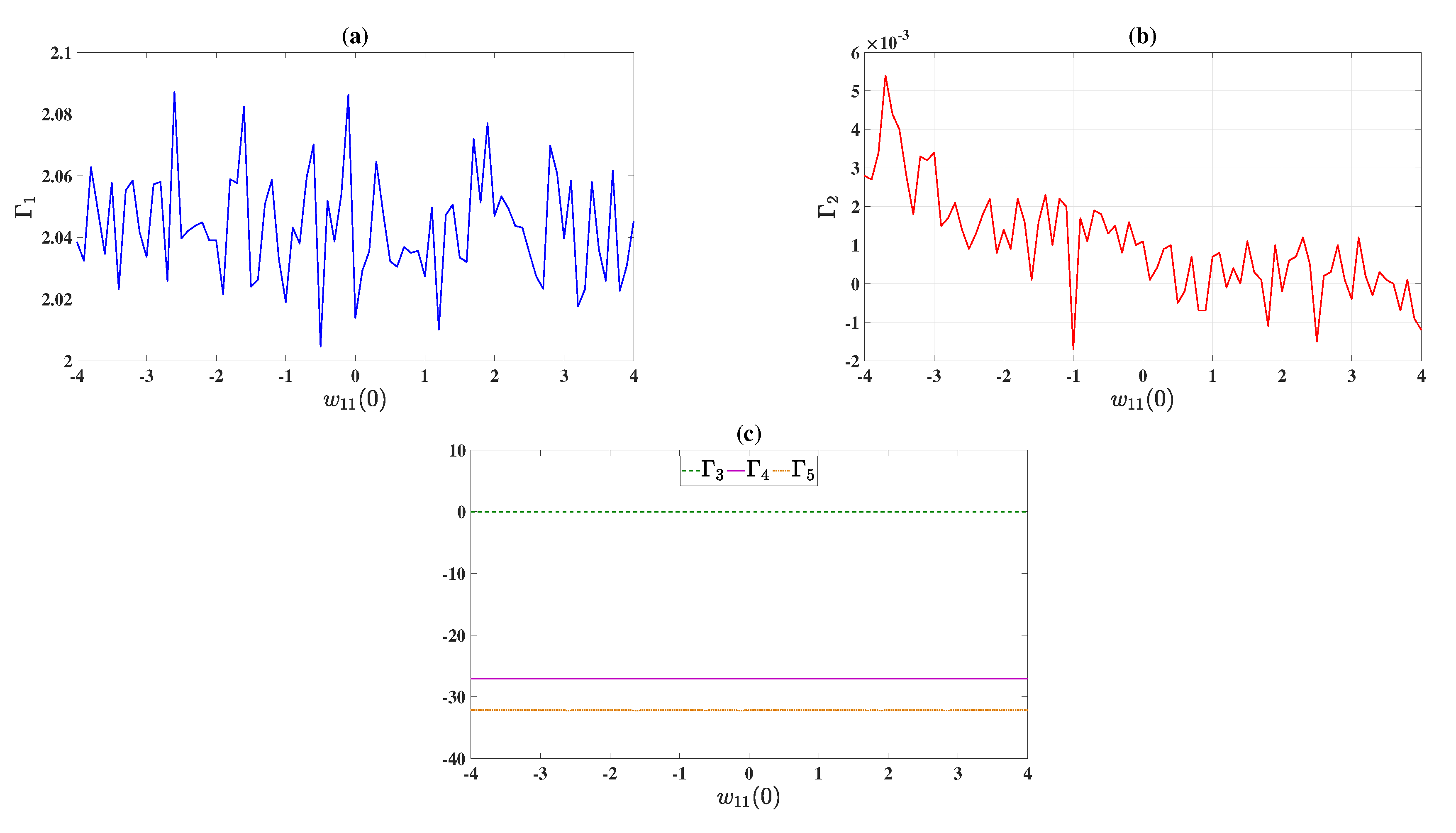

LEs of model (1.4) for , versus , versus , and versus .

Figure 5.

LEs of model (1.4) for , versus , versus , and versus .

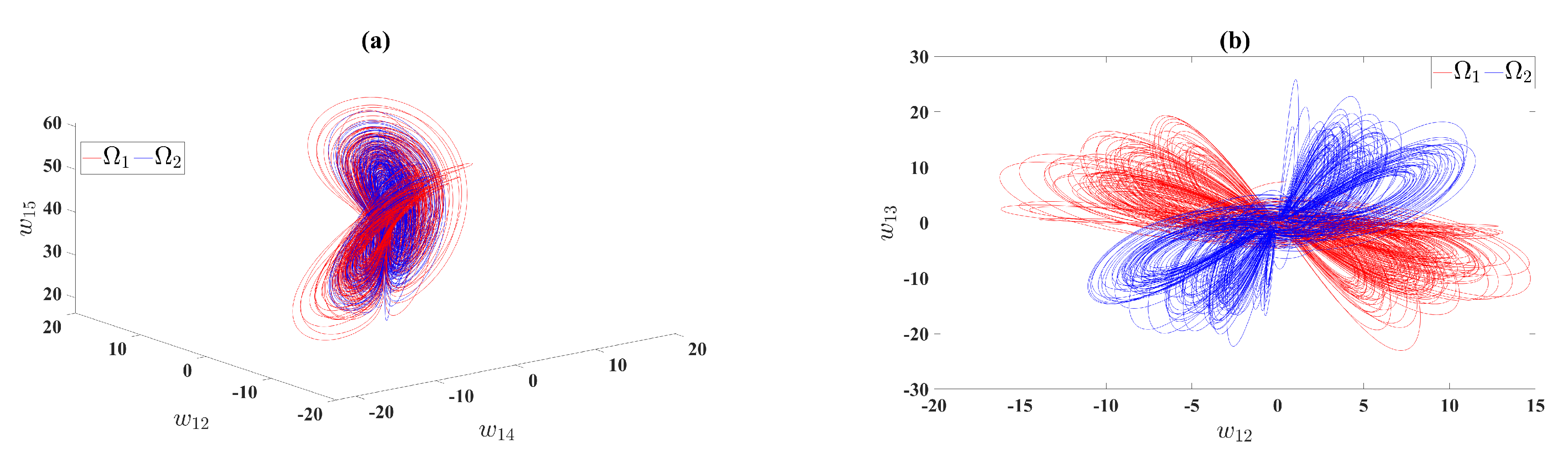

Figure 6.

Different coexisting attractors of model (1.4) for and different initial conditions and on space and space.

Figure 6.

Different coexisting attractors of model (1.4) for and different initial conditions and on space and space.

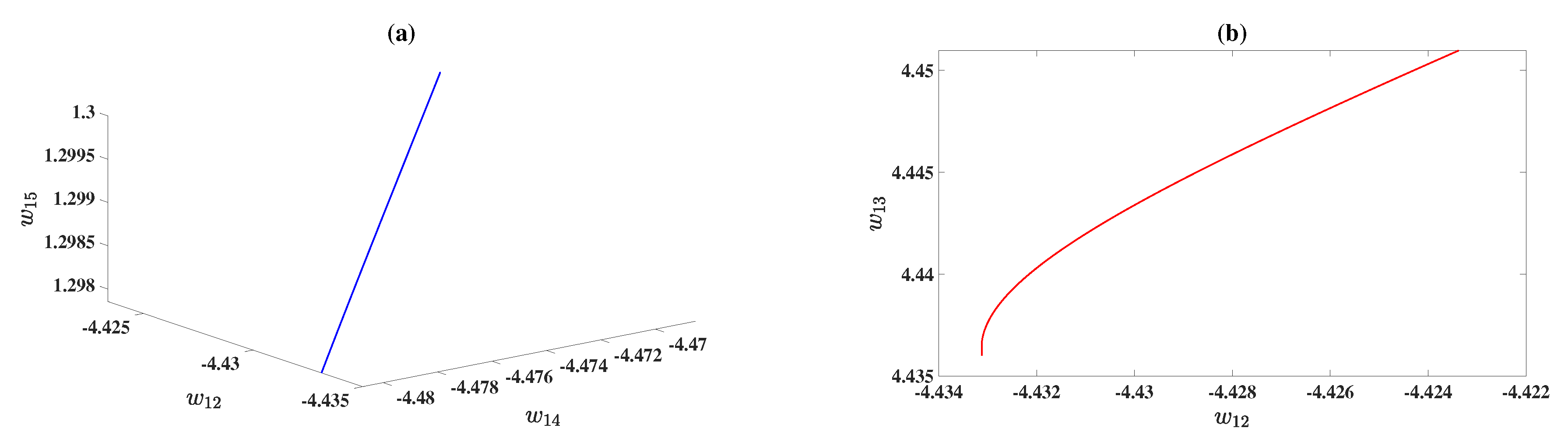

Figure 7.

Solution that approaches FPs of the DOHD laser model (1.4) for and the initial condition , space and space.

Figure 7.

Solution that approaches FPs of the DOHD laser model (1.4) for and the initial condition , space and space.

Figure 8.

DCS of: the first two drive models of (6.17-6.18) in space and the first response model of (6.19) in space.

Figure 8.

DCS of: the first two drive models of (6.17-6.18) in space and the first response model of (6.19) in space.

Figure 9.

DCS of: the second two drive models of (6.17-6.18) in space and the second response model of (6.19) in space.

Figure 9.

DCS of: the second two drive models of (6.17-6.18) in space and the second response model of (6.19) in space.

Figure 10.

Synchronization errors for the first two drive models of (6.17-6.18) and the first one response model of (6.19) versus t, (solution of the model (6.21) for ).

Figure 10.

Synchronization errors for the first two drive models of (6.17-6.18) and the first one response model of (6.19) versus t, (solution of the model (6.21) for ).

Figure 11.

Synchronization errors for the second two drive models of (6.17-6.18) and the second one response model of (6.19) versus t, (solution of the model (6.21) for ).

Figure 11.

Synchronization errors for the second two drive models of (6.17-6.18) and the second one response model of (6.19) versus t, (solution of the model (6.21) for ).