Submitted:

20 August 2025

Posted:

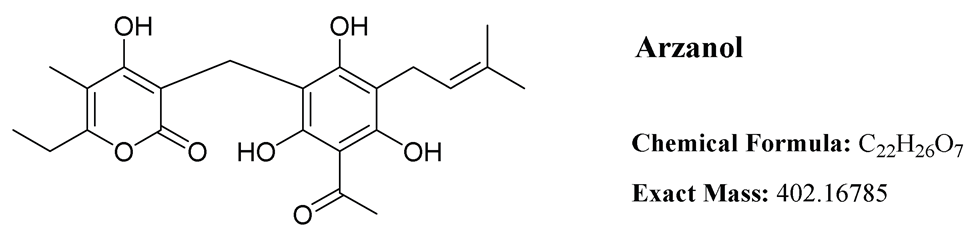

21 August 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Isolation, Natural Sources and Synthesis

3. Chemical Structure and Properties

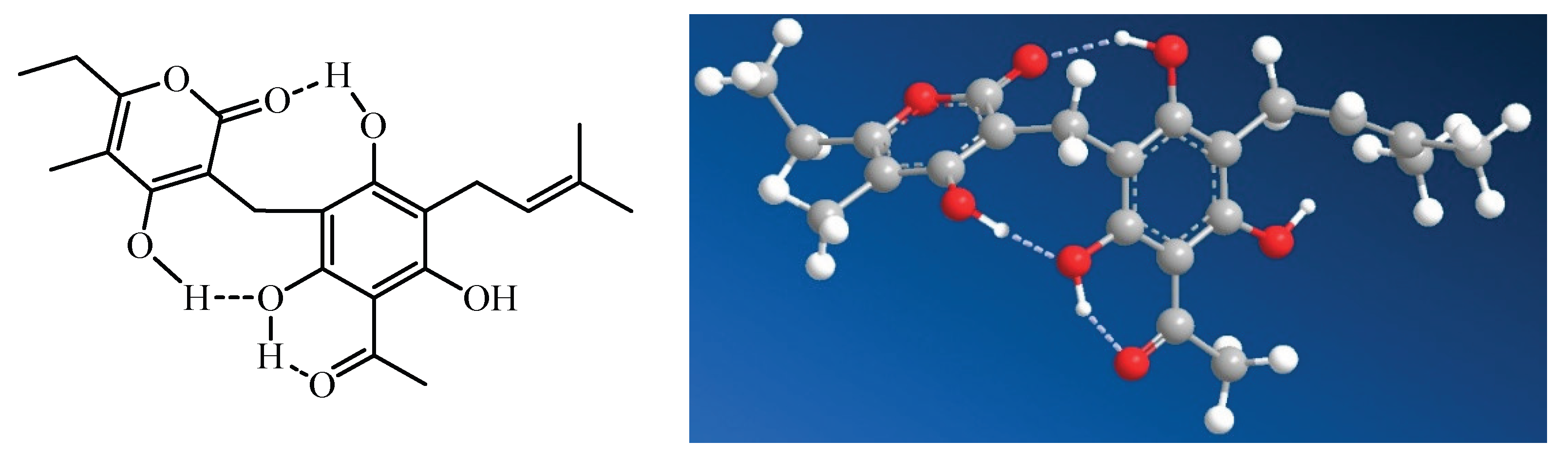

3.1. Conformational Dynamics and Solution Structure

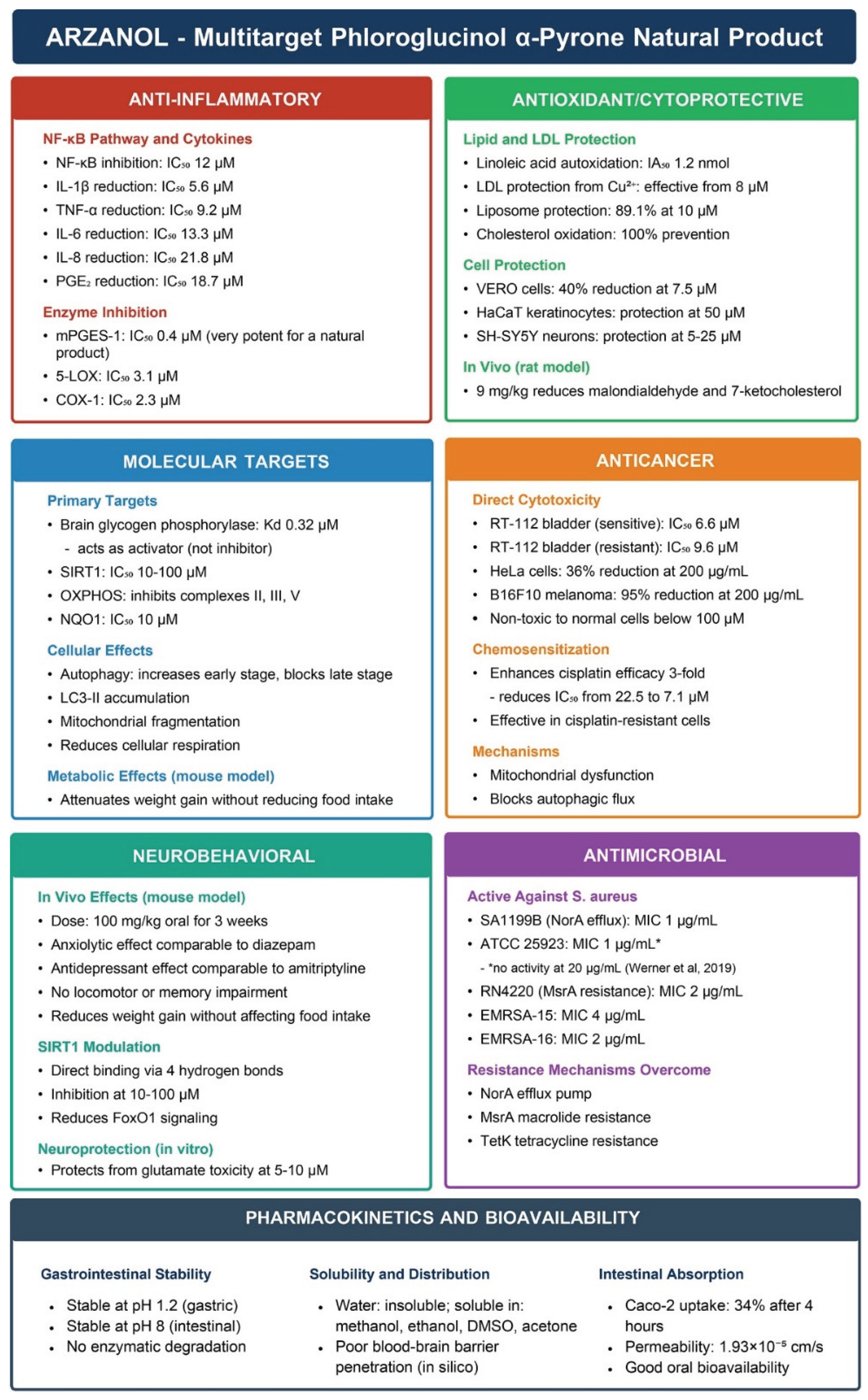

4. Anti-inflammatory Activity

4.1. NF-κB Pathway Inhibition

4.2. Dual Enzymatic Inhibition

4.3. In Vivo Validation

5. Antioxidant Activity

5.1. Protection Against Lipid Peroxidation in Lipoproteins

5.2. Mechanistic Insights into Antioxidant Action

5.3. Cellular Cytoprotection Against Oxidative Stress

5.3.1. Protection of Skin Cells

5.3.2. Neuroprotection Against Oxidative Stress

5.4. In Vivo Antioxidant Effects

6. Antimicrobial Activity

7. Molecular Targets and Mechanisms

7.1. Brain Glycogen Phosphorylase

7.2. Autophagy Modulation and Mitochondrial Dysfunction

7.2.1. Mitochondrial Toxicity as a Mechanism of Action

7.3. Anticancer Activity and Chemosensitization

7.4. SIRT1 Inhibition and Metabolic Regulation

8. Pharmacokinetics and Bioavailability

8.1. Gastrointestinal Stability

8.2. Intestinal Absorption and Cellular Transport

8.3. Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration

9. Neurobehavioral and Metabolic Effects

9.1. Anxiolytic and Antidepressant Properties

9.2. Metabolic Effects and Weight Management

9.3. Direct Neuroprotective Effects

10. Cytotoxicity Profile and Selectivity

11. Structure-Activity Relationships and Future Perspectives

- SAR studies to identify key pharmacophores for each activity

- Synthesis of analogs with greater potency/selectivity

- Formulations to improve solubility and BBB penetration

- Clinical validation in inflammatory, metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases

- Investigation of potential drug-drug interactions given the multiple molecular targets

- Long-term safety evaluation for chronic use

Conclusion

| Category | Subcategory | Biological Activity | IC50/EC50/Dose | Model/Cell Type | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-inflammatory | NF-κB Pathway | Switches off NF-κB in Jurkat immune-cell assay | IC50 ~5 µg/mL (≈12 µM) | Jurkat cells | [1] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Cytokine Inhibition | IL-1β reduction | IC50 5.6 µM | LPS-stimulated human monocytes | [1] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Cytokine Inhibition | TNF-α reduction | IC50 9.2 µM | LPS-stimulated human monocytes | [1] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Cytokine Inhibition | IL-6 reduction | IC50 13.3 µM | LPS-stimulated human monocytes | [1] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Cytokine Inhibition | IL-8 reduction | IC50 21.8 µM | LPS-stimulated human monocytes | [1] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Eicosanoid Pathway | PGE2 reduction | IC50 18.7 µM | LPS-stimulated human monocytes | [1] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Eicosanoid Pathway | 5-LOX inhibition | IC50 3.1 µM | Recombinant enzyme assay | [2] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Eicosanoid Pathway | 5-LOX inhibition in neutrophils (A23187/AA stimulation) | IC50 2.9 µM | Human neutrophils | [2] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Eicosanoid Pathway | 5-LOX inhibition in neutrophils (LPS/fMLP stimulation) | IC50 8.1 µM | Human neutrophils | [2] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Eicosanoid Pathway | mPGES-1 inhibition | IC50 0.4 µM | IL-1β-stimulated A549 cells | [2] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Eicosanoid Pathway | COX-1 inhibition (12-HHT reduction) | IC50 2.3 µM | Human platelets | [2] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Eicosanoid Pathway | COX-1 inhibition (TXB2 reduction) | IC50 2.9 µM | Human platelets | [2] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Eicosanoid Pathway | PGE2 reduction in whole blood | ~50% at 30 µM | Human whole blood | [2] |

| Anti-inflammatory | In Vivo | Reduces pleural fluid volume | 59% at 3.6 mg/kg | Rat pleurisy model | [2] |

| Anti-inflammatory | In Vivo | Reduces inflammatory cell infiltration | 48% at 3.6 mg/kg | Rat pleurisy model | [2] |

| Anti-inflammatory | In Vivo | Reduces PGE2 levels | 47% at 3.6 mg/kg | Rat pleurisy model | [2] |

| Anti-inflammatory | In Vivo | Reduces LTB4 levels | 31% at 3.6 mg/kg | Rat pleurisy model | [2] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Lipid Protection | Complete inhibition of linoleic acid autoxidation | IA50 1.2 nmol | Solvent-free film (37°C, 32h) | [3] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Lipid Protection | Protection under EDTA-mediated oxidation | ≥80% at 1 nmol, 100% at ≥2.5 nmol | Linoleic acid + EDTA | [3] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Lipid Protection | Protection in FeCl3-catalyzed oxidation | 13% at 40 nmol, 80% at 80 nmol | Linoleic acid + FeCl3 | [3] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Cholesterol Protection | Complete protection against cholesterol oxidation | 100% at 10 nmol | 140°C thermal oxidation | [3] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Cholesterol Protection | Prevention of 7-keto and 7β-OH formation | IA50 5.6-6.8 nmol | 140°C, 1-2h | [4] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | LDL Protection | Protects LDL from Cu2+-induced oxidation | Significant from 8 µM | Human LDL (37°C, 2h) | [16] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Liposome Protection | Protection of polyunsaturated fatty acids | 89.1% at 10 µM | Phospholipid liposomes + Cu2+ | [4] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Cell Protection | No cytotoxicity to VERO cells | Up to 40 µM | VERO fibroblasts | [3] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Cell Protection | Reduces lipid peroxidation in VERO cells | 40% reduction at 7.5 µM | VERO cells + 750 µM TBH | [3] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Cell Protection | No cytotoxicity to VERO cells | Up to 50 µM | VERO cells (24h) | [16] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Cell Protection | No cytotoxicity to differentiated Caco-2 | Up to 100 µM | Differentiated Caco-2 (24h) | [16] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Cell Protection | Protects VERO cells from TBH | Significant at 25-50 µM | VERO cells + TBH | [16] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Cell Protection | Protects Caco-2 cells from TBH | Significant from 25 µM | Differentiated Caco-2 + TBH | [16] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | In Vivo | Prevents plasma lipid consumption | 9 mg/kg i.p. | Wistar rats + Fe-NTA | [4] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | In Vivo | Protects plasma unsaturated fatty acids | Complete at 9 mg/kg | Wistar rats + Fe-NTA | [4] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | In Vivo | Reduces plasma MDA levels | 9 mg/kg | Wistar rats + Fe-NTA | [4] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | In Vivo | Reduces plasma 7-ketocholesterol | 9 mg/kg | Wistar rats + Fe-NTA | [4] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Keratinocyte Protection | No cytotoxicity | 5-100 µM | HaCaT cells | [12] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Keratinocyte Protection | Protects against H2O2 cytotoxicity | 50 µM pre-treatment | HaCaT cells + 2.5-5 mM H2O2 | [12] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Keratinocyte Protection | Reduces ROS generation | 50 µM | HaCaT cells + 0.5-5 mM H2O2 | [12] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Keratinocyte Protection | Prevents lipid peroxidation | 50 µM | HaCaT cells + 2.5-5 mM H2O2 | [12] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Keratinocyte Protection | Prevents apoptosis (caspase-3/7) | 50 µM | HaCaT cells + 5 mM H2O2 | [12] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Keratinocyte Protection | Preserves mitochondrial membrane potential | 50 µM | HaCaT cells + 5 mM H2O2 | [12] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Neuronal Protection | Increases viability (differentiated cells) | 5-25 µM | Differentiated SH-SY5Y | [18] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Neuronal Protection | Cytotoxic at high dose (differentiated cells) | 71% reduction at 100 µM | Differentiated SH-SY5Y | [18] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Neuronal Protection | Non-toxic (undifferentiated cells) | 2.5-100 µM | Undifferentiated SH-SY5Y | [18] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Neuronal Protection | Protects differentiated cells from H2O2 | 5-25 µM | Differentiated SH-SY5Y + 0.5 mM H2O2 | [18] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Neuronal Protection | Protects undifferentiated cells from H2O2 | 5 µM | Undifferentiated SH-SY5Y + 0.5 mM H2O2 | [18] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Neuronal Protection | Reduces ROS (differentiated cells) | 5-25 µM | Differentiated SH-SY5Y + H2O2 | [18] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Neuronal Protection | Reduces ROS (undifferentiated cells) | 5 µM | Undifferentiated SH-SY5Y + H2O2 | [18] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Neuronal Protection | Decreases basal apoptosis | 5-25 µM | Differentiated SH-SY5Y | [18] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Neuronal Protection | Protects from H2O2-induced apoptosis (PI assay) | 10-25 µM | ifferentiated SH-SY5Y + 0.25 mM H2O2 | [18] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Neuronal Protection | Protects from H2O2-induced apoptosis (caspase) | 10-25 µM | Differentiated SH-SY5Y + 0.25 mM H2O2 | [18] |

| Neuroprotective/Neurobehavioral | Neuroprotection | Protects from glutamate toxicity | 5-10 µM | SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells | [9] |

| Neuroprotective/Neurobehavioral | Metabolic Effects | Attenuates weight gain (no effect on food intake) | 100 mg/kg, 3 weeks oral | Mice | [9] |

| Neuroprotective/Neurobehavioral | Behavioral Effects | Anxiolytic effect (comparable to diazepam) | 100 mg/kg | Mice | [9] |

| Neuroprotective/Neurobehavioral | Behavioral Effects | Antidepressant effect (comparable to amitriptyline) | 100 mg/kg | Mice | [9] |

| Neuroprotective/Neurobehavioral | Behavioral Effects | No locomotor or memory impairment | 100 mg/kg | Mice | [9] |

| Neuroprotective/Neurobehavioral | SIRT1 Modulation | Binds SIRT1 via 4 H-bonds | Molecular docking | In silico | [9] |

| Neuroprotective/Neurobehavioral | SIRT1 Modulation | SIRT1 inhibition | 10-100 µM | Cell-free assay | [9] |

| Neuroprotective/Neurobehavioral | SIRT1 Modulation | Reduces SIRT1 expression/activity | 100 mg/kg HSE or 10 µM | Mouse hippocampus (ex vivo) | [9] |

| Neuroprotective/Neurobehavioral | SIRT1 Modulation | Suppresses FoxO1 signaling | 100 mg/kg HSE or 10 µM | Cell and tissue studies | [9] |

| Anticancer | Autophagy Modulation | Inhibits starvation-induced autophagy | +164.6% mCitrine-LC3 | Mouse embryonic fibroblasts | [11] |

| Anticancer | Autophagy Modulation | Accumulates LC3-II and p62/SQSTM1 | Not specified | HeLa cells | [11] |

| Anticancer | Autophagy Modulation | Increases but reduces size of autophagosomes | Not specified | HeLa cells | [11] |

| Anticancer | Autophagy Modulation | Increases ATG16L1-positive structures | Not specified | HeLa cells | [11] |

| Anticancer | Direct Cytotoxicity | Cytotoxic to cisplatin-sensitive bladder cancer | IC50 6.6 µM | RT-112 cells | [11] |

| Anticancer | Direct Cytotoxicity | Cytotoxic to cisplatin-resistant bladder cancer | IC50 9.6 µM | RT-112 cells | [11] |

| Anticancer | Direct Cytotoxicity | Cytotoxic to undifferentiated Caco-2 | 55% reduction at 100 µM | Undifferentiated Caco-2 | [4] |

| Anticancer | Direct Cytotoxicity | Cytotoxic to HeLa cells | 36% reduction at 200 µg/mL | HeLa cells (24h) | [4] |

| Anticancer | Direct Cytotoxicity | Cytotoxic to B16F10 cells | 95% reduction at 200 µg/mL | B16F10 melanoma (24h) | [4] |

| Anticancer | Direct Cytotoxicity | No cytotoxicity to differentiated Caco-2 | Up to 100 µM | Differentiated Caco-2 | [4] |

| Anticancer | Direct Cytotoxicity | No cytotoxicity to L5178Y cells | 20 µg/mL | Murine lymphoma L5178Y | [6] |

| Anticancer | Chemosensitization | Enhances cisplatin effect | Reduces IC50 from 22.5 to 7.1 µM | RT-112 cells | [11] |

| Anticancer | Mitochondrial Effects | Induces mitochondrial fragmentation | Not specified | HeLa cells | [11] |

| Anticancer | Mitochondrial Effects | Reduces basal/maximal respiration | Not specified | HeLa cells | [11] |

| Anticancer | Mitochondrial Effects | Inhibits OXPHOS complexes II, III, V | Not specified | Isolated mitochondria | [11] |

| Anticancer | Mitochondrial Effects | Inhibits NQO1 | Significant at 10 µM | Direct activity assay | [11] |

| Metabolic | Glycogen Metabolism | Binds brain Glycogen Phosphorylase (bGP) | Identified as main target | HeLa cell lysates | [10] |

| Metabolic | Glycogen Metabolism | Direct bGP binding (DARTS confirmed) | Dose-dependent protection | DARTS assay | [10] |

| Metabolic | Glycogen Metabolism | Binds at AMP allosteric site | Competitive with AMP | Competitive binding assay | [10] |

| Metabolic | Glycogen Metabolism | High-affinity bGP binding | Kd = 0.32 ± 0.15 µM | Surface Plasmon Resonance | [10] |

| Metabolic | Glycogen Metabolism | Predicted AMP site binding | Kd,pred = 0.65 ± 0.18 µM | Molecular docking | [10] |

| Metabolic | Glycogen Metabolism | Activates bGP enzyme | Dose-dependent activation | HeLa cell lysates | [10] |

| Antibacterial | S. aureus (drug-resistant) | SA1199B (NorA efflux) inhibition | MIC 1 µg/mL | S. aureus SA1199B | [5] |

| Antibacterial | S. aureus (drug-resistant) | XU212 (TetK) inhibition | MIC 4 µg/mL | S. aureus XU212 | [5] |

| Antibacterial | S. aureus (drug-resistant) | ATCC 25923 (reference) inhibition | MIC 1 µg/mL | S. aureus ATCC 25923, Mueller-Hinton/MTT method | [5] |

| Antibacterial | S. aureus (drug-resistant) | RN4220 (MsrA) inhibition | MIC 2 µg/mL | S. aureus RN4220 | [5] |

| Antibacterial | S. aureus (drug-resistant) | EMRSA-15 (epidemic MRSA) inhibition | MIC 4 µg/mL | S. aureus EMRSA-15 | [5] |

| Antibacterial | S. aureus (drug-resistant) | EMRSA-16 (epidemic MRSA) inhibition | MIC 2 µg/mL | S. aureus EMRSA-16 | [5] |

| Antibacterial | Negative Results | No activity against S. aureus ATCC 25923 | No inhibition at 20 µg/mL | S. aureus ATCC 25923, CLSI broth microdilution | [6] |

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Appendino, G.; Ottino, M.; Marquez, N.; Bianchi, F.; Giana, A.; Ballero, M.; Sterner, O.; Fiebich, B.L.; Munoz, E. Arzanol, an anti-inflammatory and anti-HIV-1 phloroglucinol α-pyrone from Helichrysum italicum ssp. microphyllum. Journal of natural products 2007, 70, 608–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, J.; Koeberle, A.; Dehm, F.; Pollastro, F.; Appendino, G.; Northoff, H.; Rossi, A.; Sautebin, L.; Werz, O. Arzanol, a prenylated heterodimeric phloroglucinyl pyrone, inhibits eicosanoid biosynthesis and exhibits anti-inflammatory efficacy in vivo. Biochemical pharmacology 2011, 81, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, A.; Deiana, M.; Atzeri, A.; Corona, G.; Incani, A.; Melis, M.P.; Appendino, G.; Dessì, M.A. Evaluation of the antioxidant and cytotoxic activity of arzanol, a prenylated α-pyrone–phloroglucinol etherodimer from Helichrysum italicum subsp. microphyllum. Chemico-Biological Interactions 2007, 165, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, A.; Atzeri, A.; Nieddu, M.; Appendino, G. New insights into the antioxidant activity and cytotoxicity of arzanol and effect of methylation on its biological properties. Chemistry and physics of lipids 2017, 205, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taglialatela-Scafati, O.; Pollastro, F.; Chianese, G.; Minassi, A.; Gibbons, S.; Arunotayanun, W.; Mabebie, B.; Ballero, M.; Appendino, G. Antimicrobial phenolics and unusual glycerides from Helichrysum italicum subsp. microphyllum. Journal of natural products 2013, 76, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, J.; Ebrahim, W.; Özkaya, F.C.; Mándi, A.; Kurtán, T.; El-Neketi, M.; Liu, Z.; Proksch, P. Pyrone derivatives from Helichrysum italicum. Fitoterapia 2019, 133, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Abrosca, B.; Buommino, E.; Caputo, P.; Scognamiglio, M.; Chambery, A.; Donnarumma, G.; Fiorentino, A. Phytochemical study of Helichrysum italicum (Roth) G. Don: Spectroscopic elucidation of unusual amino-phlorogucinols and antimicrobial assessment of secondary metabolites from medium-polar extract. Phytochemistry 2016, 132, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akaberi, M.; Danton, O.; Tayarani-Najaran, Z.; Asili, J.; Iranshahi, M.; Emami, S.A.; Hamburger, M. HPLC-Based Activity Profiling for Antiprotozoal Compounds in the Endemic Iranian Medicinal Plant Helichrysum oocephalum. Journal of Natural Products 2019, 82, 958–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgonetti, V.; Caroli, C.; Governa, P.; Virginia, B.; Pollastro, F.; Franchini, S.; Manetti, F.; Les, F.; López, V.; Pellati, F.; Galeotti, N. Helichrysum stoechas (L.) Moench reduces body weight gain and modulates mood disorders via inhibition of silent information regulator 1 (SIRT1) by arzanol. Phytotherapy Research 2023, 37, 4304–4320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Gaudio, F.; Pollastro, F.; Mozzicafreddo, M.; Riccio, R.; Minassi, A.; Monti, M.C. Chemoproteomic fishing identifies arzanol as a positive modulator of brain glycogen phosphorylase. Chemical Communications 2018, 54, 12863–12866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deitersen, J.; Berning, L.; Stuhldreier, F.; Ceccacci, S.; Schlütermann, D.; Friedrich, A.; Wu, W.; Sun, Y.; Böhler, P.; Berleth, N. High-throughput screening for natural compound-based autophagy modulators reveals novel chemotherapeutic mode of action for arzanol. Cell Death & Disease 2021, 12, 560. [Google Scholar]

- Piras, F.; Sogos, V.; Pollastro, F.; Appendino, G.; Rosa, A. Arzanol, a natural phloroglucinol α-pyrone, protects HaCaT keratinocytes against H2O2-induced oxidative stress, counteracting cytotoxicity, reactive oxygen species generation, apoptosis, and mitochondrial depolarization. Journal of Applied Toxicology 2024, 44, 720–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Les, F.; Venditti, A.; Cásedas, G.; Frezza, C.; Guiso, M.; Sciubba, F.; Serafini, M.; Bianco, A.; Valero, M.S.; López, V. Everlasting flower (Helichrysum stoechas Moench) as a potential source of bioactive molecules with antiproliferative, antioxidant, antidiabetic and neuroprotective properties. Industrial crops and products 2017, 108, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minassi, A.; Cicione, L.; Koeberle, A.; Bauer, J.; Laufer, S.; Werz, O.; Appendino, G. A Multicomponent Carba-Betti Strategy to Alkylidene Heterodimers–Total Synthesis and Structure–Activity Relationships of Arzanol. 2012.

- Rastrelli, F.; Bagno, A.; Appendino, G.; Minassi, A. Bioactive Phloroglucinyl Heterodimers: The Tautomeric and Rotameric Equlibria of Arzanol. European Journal of Organic Chemistry 2016, 2016, 4810–4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.; Pollastro, F.; Atzeri, A.; Appendino, G.; Melis, M.P.; Deiana, M.; Incani, A.; Loru, D.; Dessì, M.A. Protective role of arzanol against lipid peroxidation in biological systems. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids 2011, 164, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mammino, L. Complexes of arzanol with a Cu2+ ion: a DFT study. Journal of Molecular Modeling 2017, 23, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piras, F.; Sogos, V.; Pollastro, F.; Rosa, A. Protective effect of arzanol against H2O2-induced oxidative stress damage in differentiated and undifferentiated SH-SY5Y Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 7386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, L.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Ciriani, M.; Falé, P.L.V.; Teixeira, V.; Madeira, P.; Machuqueiro, M.; Pacheco, R.; Florêncio, M.H.; Ascensão, L.; Serralheiro, M.L.M. Antiacetylcholinesterase activity and docking studies with chlorogenic acid, cynarin and arzanol from Helichrysum stoechas (Lamiaceae). Medicinal Chemistry Research 2017, 26, 2942–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).