3. Results

A 63-year-old woman presented with visual complaints. At the age of 54, she had had an automobile accident without head trauma, and following that, complained repeatedly that something was “not right” about her vision. She also felt that, overall, her brain “simply wasn’t right”. She felt her memory was not the same and her ability to think as she formerly had was somehow different. However, multiple medical evaluations failed to reach a diagnosis. Furthermore, she was told there was nothing wrong, when she knew in fact this was untrue.

Then in her early 60s, she began to experience more definitive symptoms, such as blurry vision, optic ataxia, and difficulty seeing multiple objects in her visual field (simultanagnosia). She developed difficulty reading, and was unable to use her computer or drive an automobile. In one instance, while she was driving she felt that the scene in front of her rippled, just as one might see when one watches a movie and the screen ripples to represent going back in time. When her vision returned there was another car right next to her that she hadn’t seen. It was at this time she stopped driving.

In addition to her declining vision, her memory began to decline rapidly, depression set in, and she became angry that no one seemed to be able to help her. She began to isolate herself from friends, concerned about their reaction to her verbal repetitions. Travel was tiring and there was generally a period of disorientation upon arrival at the destination. Her affect became flat. She joined a support group for patients and care partners of those with Alzheimer’s, and since she was still verbally proficient, she was able to explain to the other care partners what this condition was like. A few years later, they reflected to her that for the first year after they had met her, she had not smiled.

With her blurry vision and her increasing loss of memory, she stopped reading. She had trouble keeping track of what she was reading and because she could not see the words well, she became irritated and frustrated. She had difficulty organizing and became irritated and then apathetic. Her office became cluttered.

She began to rely fully on her husband for meal preparation, management of medication, and direction of what to do throughout the day. She was determined to find a way to beat her illness, but she did not have the faculties to follow through.

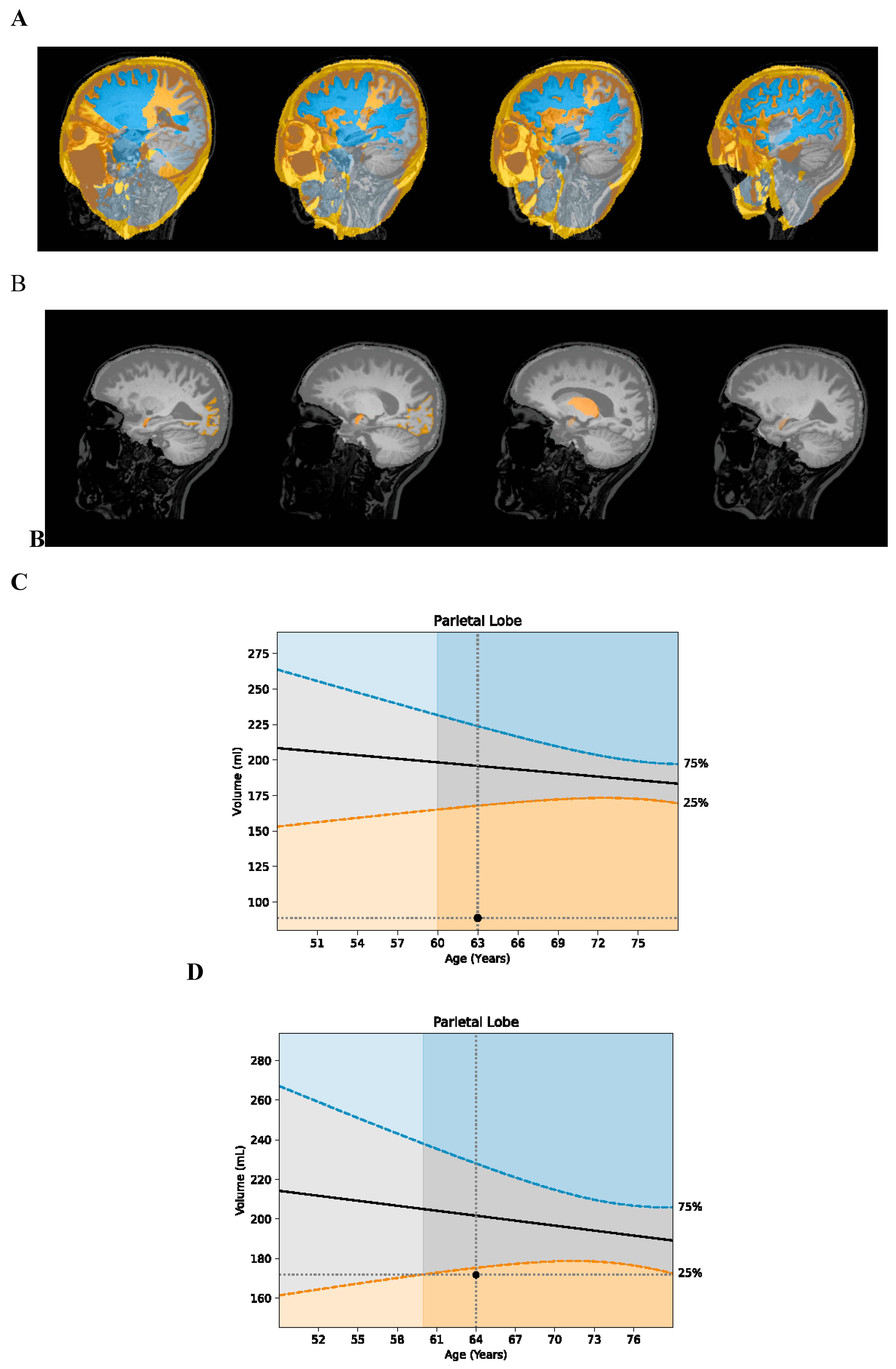

Her MRI volumetrics showed parietal and occipital atrophy, with parietal lobe volume at <1

st percentile for age, occipital lobe volume at the 10

th percentile, temporal lobe volume at the 41

st percentile, and frontal lobe volume at the 13

th percentile (

Table 1). Based on her symptoms and atrophy pattern, a diagnosis of PCA was made.

She participated in a pharmaceutical trial for an anti-amyloid antibody for 1.5 years, but after the completion of the trial, found that she had been in the placebo-control group.

She took donepezil for a few years without noticing any symptomatic improvement. When she discontinued donepezil, she did not notice any acceleration of decline, but did notice that the headaches she had had abated.

Laboratory evaluation showed her to be ApoE4 heterozygous, with WBC 4400/mL, HOMA-IR of 0.73, hemoglobin A1c 5.1%, homocysteine 6.2 mM, estradiol 0 pg/mL, progesterone 13.66 ng/mL, TSH 1.22 mU/mL, vitamin D 32.9 ng/mL, serum copper 155 mg/dL, serum zinc 132 mg/dL, ALT 16 units/L, AST 30 units/L, blood mercury 5 mcg/L, MMP-9 135 ng/mL (normal < 331 ng/mL), TGF-1 11,360 pg/mL (normal < 2380 pg/mL), LDL 122 mg/dL, LDL particle number 1449 nM, triglycerides 57 mg/dL, albumin 4.4 g/dL, and glutathione 585 mM.

She failed the visual contrast sensitivity test (

https://www.vcstest.com/). Plasma p-tau 181 was elevated at 1.72 pg/mL (normal range 0-0.97 pg/mL). A sleep study disclosed mild sleep apnea, with an apnea/hypopnea index of 9.9.

Urinary mycotoxin analysis was positive for ochratoxin, aflatoxin, trichothecenes, gliotoxin, and zearalenone. Antibodies to Borrelia and Bartonella were positive (IgM). Urinary mercury was increased at 10 mg/g of creatinine (normal < 1.3), and lead was also increased at 6.2 mg/g creatinine (normal < 1.2).

She was treated with a personalized, precision medicine approach that included:

Treatment of Bartonella for three months:

ABart ½ dropper po bid

Azithromycin 500 mg po qd

Doxycycline 100 mg po bid

Rifampin 300 mg po bid

Megasporebiotic 295 mg po bid

Treatment of mycotoxin exposure (ongoing for 2.5 years):

Bentonite clay 450 mg po bid

Activated charcoal 560 mg po bid

Chlorella 125 mg po tid

Welchol 625 mg po bid

Saccharomyces boulardii 235 mg po tid

InterFase Plus 675 mg po bid

Nystatin 500 mg po qid

Argentyn nasal spray, 2 sprays to each nostril bid

Amphotericin B 150 mg po bid

BE spray (mupirocin and EDTA) 2 sprays in each nostril bid

Treatment of lead and mercury for six months

DMSA 200 mg twice per week

In addition to the treatments above, she began a plant-rich, mildly ketogenic diet, with fasting of 12-14 hours each night. She used a breathalyzer device (Biosense) to track her acetone levels, scoring in the 30’s on average, which correlates to approximately 3 mM beta-hydroxybutyrate in the blood.

Due to a pain in her foot (which is common with Bartonella), her exercise was limited, but she used a Peloton and walked infrequently. She checked her oxygen saturation at night using a Wellue ring, and her SpO2 was an average of 96-98%, with few drops and none below 90%. She used a Sunlight sauna for diaphoresis and detoxification 2-3x/week. She began bioidentical hormone replacement therapy, valacyclovir, and took supplements tailored to her laboratory data, including Ashwagandha, Bacopa, Gotu kola, Cataplex b-gf (bovine liver, organic beet (root), nutritional yeast, defatted wheat germ, rice bran, organic sweet potato, organic carrot, and bovine adrenal), pregnenolone, DHEA, S-adenosyl methionine, NAD, glutathione, methyl-B12, zinc, vitamin D, multivitamins, magnesium threonate, pro-resolving mediators, and 5-hydroxytryptophan.

She received glutathione intravenously weekly for 10 weeks to support detoxification, ozone treatment for her pathogens, and used a grounding mat, but no change in her symptoms were linked temporally to these treatments. However, when she began exercise with oxygen therapy (EWOT), she noticed an immediate improvement in her symptoms. She was unable to do computer brain training initially, due to her vision. She also had cranial sacral therapy monthly.

In April 2023, she began vision exercises and training, which are ongoing.

As she began treatment, the first change noted was stabilization, without further decline. Next, her memory began to improve. She remembered more details in stories from a few days prior and in some cases a few weeks prior. Her engagement picked up tremendously and in the support group she began discussing how the group could collectively help others. She regained her sharp wit and her ability to tell engaging stories.

Her attitude toward life became more focused on the future. She began talking about her bucket list and started to make to-do lists again. Her feelings began to change, from her initial anger that no one had helped her 10 years prior, to being grateful for what she can do presently.

Over the year after treatment was initiated, her inability to read resolved, and she began reading without difficulty. She is once again reading with purpose and great interest. Her ability to use the computer returned, and she was once again able to do computer-based brain training.

Her engagement with others improved, and she became a leader in her Alzheimer’s support group, helping others in the group. She served as a panelist regarding her own case history in front of an audience of 100 people, answering questions extemporaneously, and accurately, for over an hour.

She responded to vision training, and whereas she initially struggled with tracking and saccadic movements, she improved these markedly, and also improved her vergence and binocular vision.

She has begun driving in parking lots but recognizes that she is not yet ready for road driving.

Her mycotoxins decreased: ochratoxin A from 36.09 to 10.98 ng/g creatinine (normal <7.5 ng/g creatinine), mycophenolic acid 213 to 37.4 (normal <37.4), zearalenone 293 to undetectable (normal <3.2). Her TGF-1 decreased from 11,360 to 6323 pg/mL (normal < 2380 pg/mL).

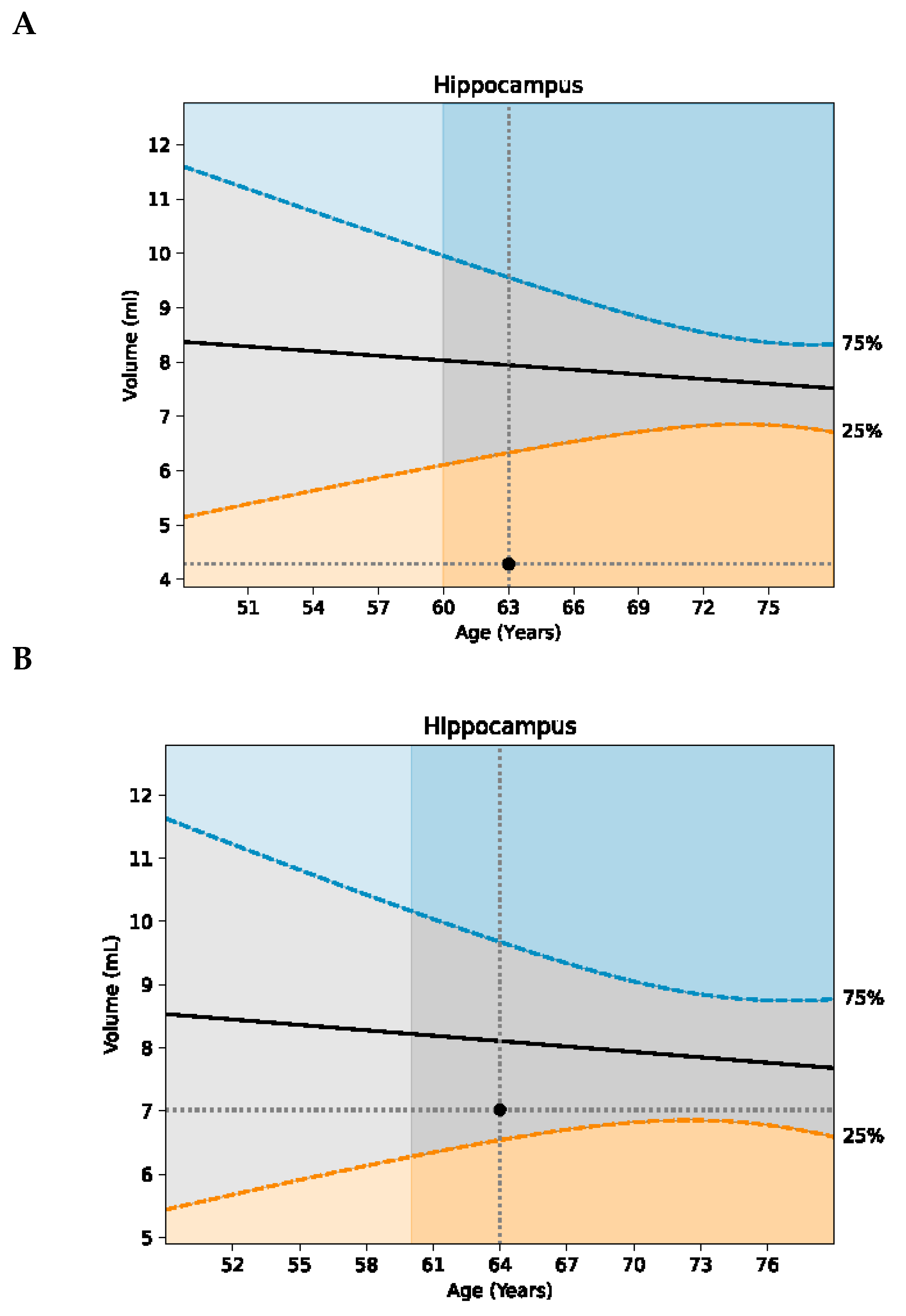

Her MRI volumetrics showed marked improvement (

Table 1): her parietal lobe volume increased from <1

st percentile to the 22

nd percentile (

Figure 1); her occipital lobe volume increased from the 10

th to 25

th percentile; and her hippocampal volume increased from the 6

th to 32

nd percentile (

Figure 2). Her p-tau 181 improved modestly, from 1.72 pg/mL to 1.68 pg/mL to 1.52 pg/mL.