Submitted:

18 August 2025

Posted:

19 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. AI Affordances and Educational Potential

1.2. Purpose and Structure of This Paper

2. Educational Context

2.1. 21st Century Graduate Skills and Dispositions

2.2. Competency Based Education

2.3. Educating the Whole Person

3. Learning with AI

3.1. Socratic Dialogue

3.2. Formative Assessment and Learning Objectives

3.3. AgenticAI and Co-Creation

4. AI-Supported Learning Systems

4.1. Learning Experience Platforms

4.2. Multi-Agent Systems

4.3. Success Criteria for an AI-Supported Learning System

- provide dialogic engagement and formative assessment;

- adapt and personalise learning activities to empower the learner;

- facilitate human-agenticAI and co-created learning;

- maintain ethical compliance;

- employ self-correcting, generative embodied multi-agent AI frameworks.

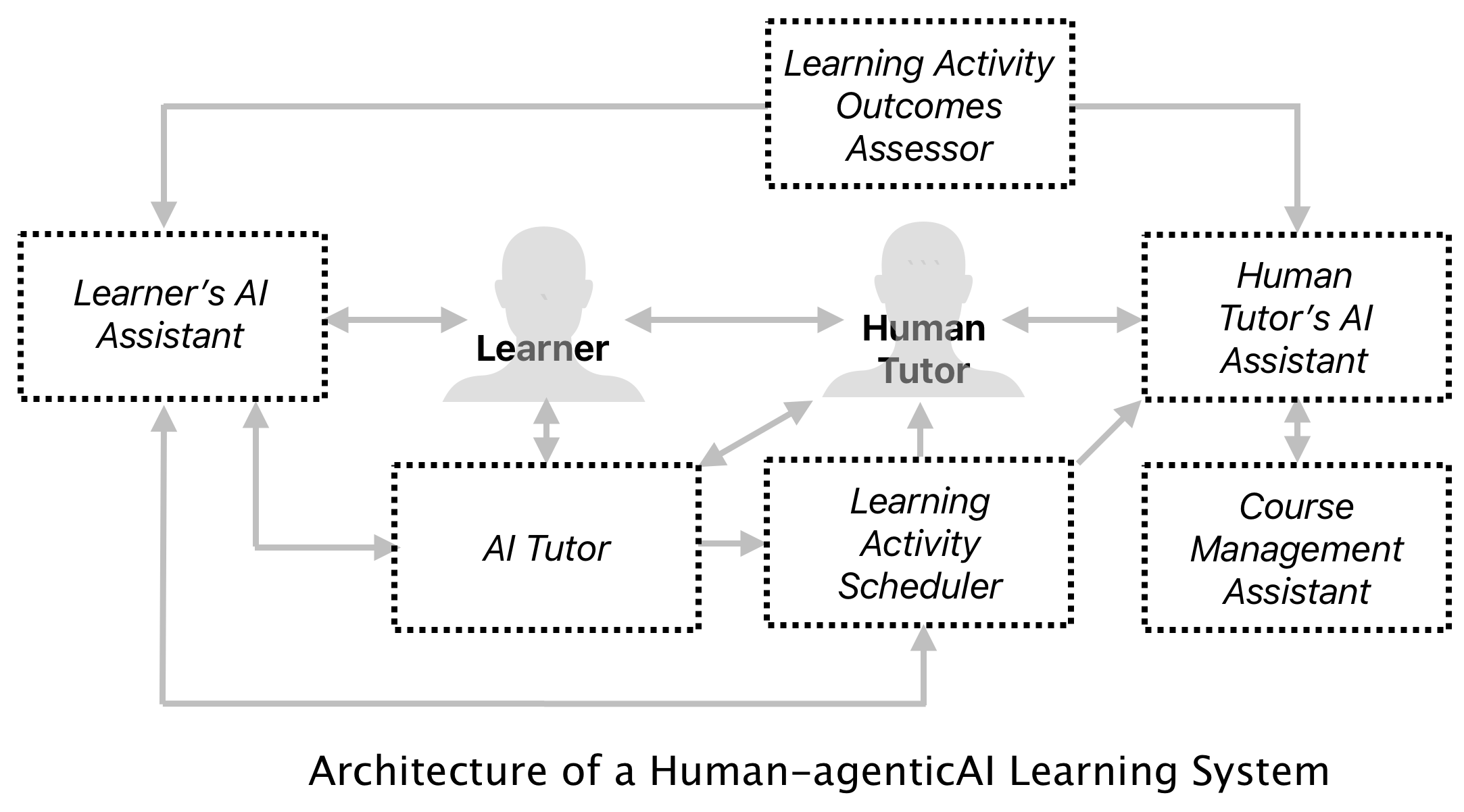

5. Architecture of a Human-agenticAI Co-Created Learning System

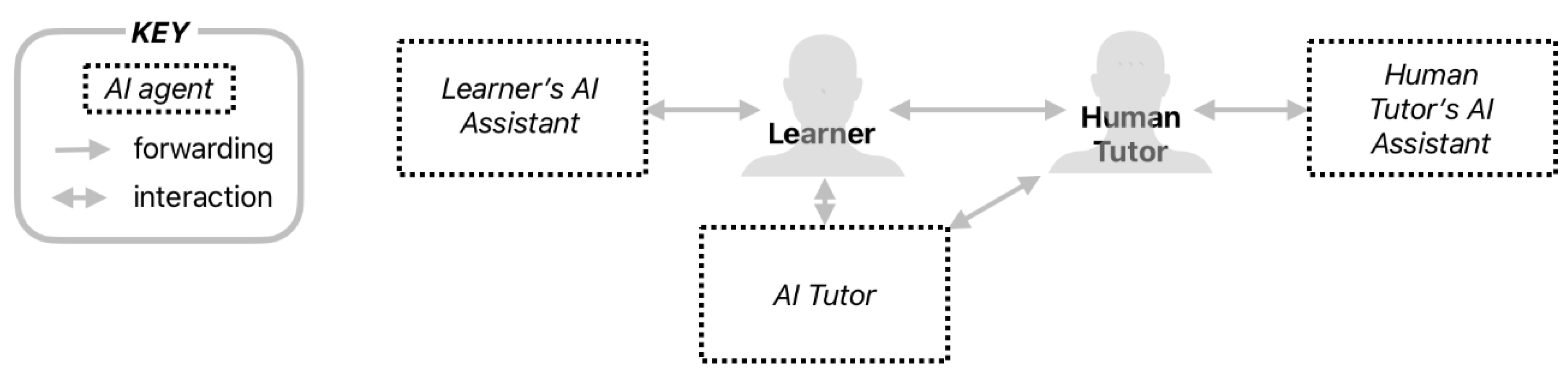

5.1. Principal Agents of the HCLS

5.2. Overview of HCLS Processes

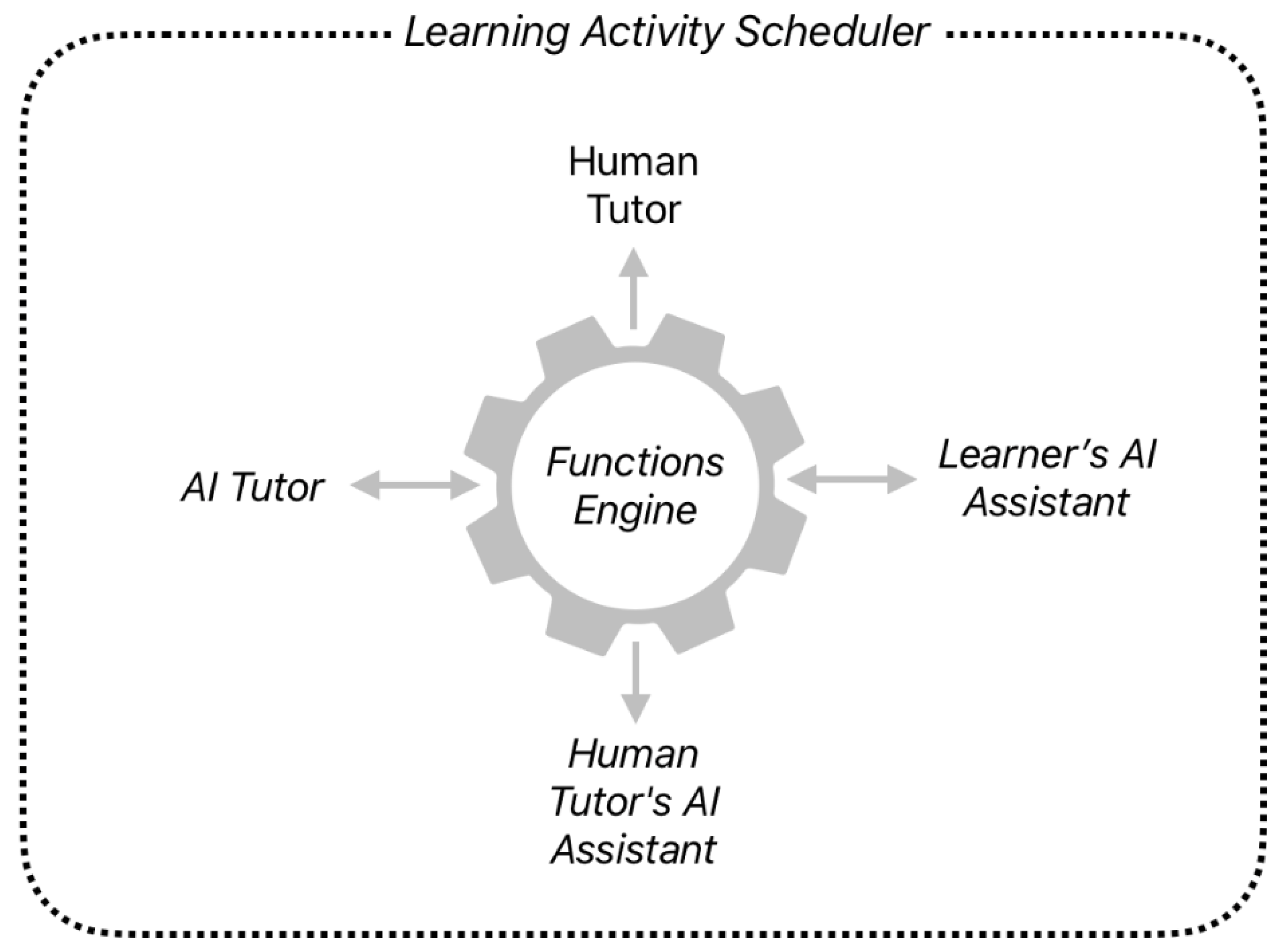

- The AI Tutor consults the Course Syllabus and activity libraries to select a learning activity for the Learner. The difficulty level and suitability are determined in consultation with the Learner’s AI Assistant and the details are passed to the Learning Activity Scheduler. This agent specifies a learning activity which is forwarded to the Learner’s AI Assistant and AI Tutor and reported to the Human Tutor’s AI Assistant.

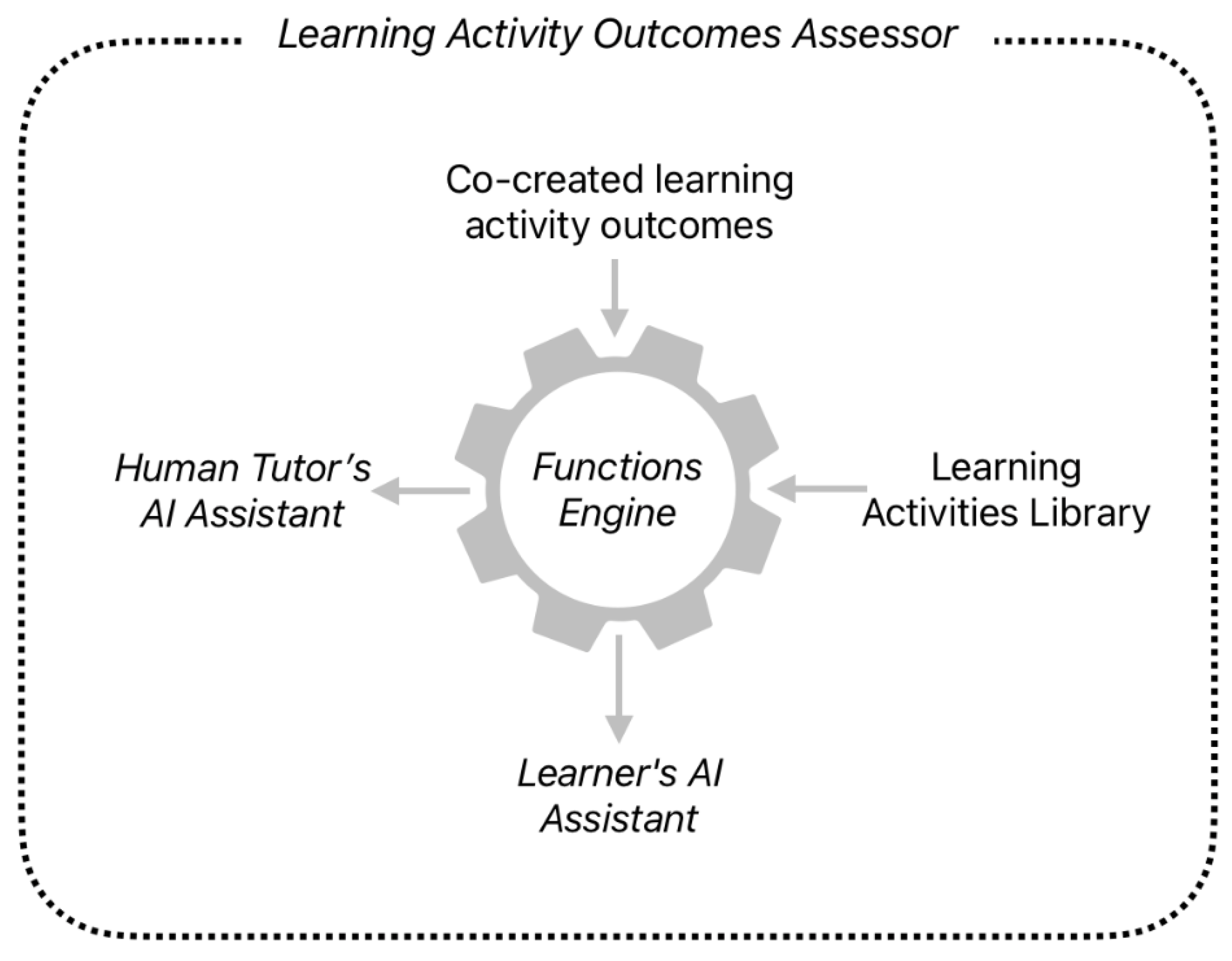

- The Learner’s AI Assistant cues the activity with the Learner at an opportune time, supports the Learner in completing the learning activity, and forwards the outcomes to the Learning Activity Outcomes Assessor.

- The Learning Activity Outcomes Assessor evaluates the outcomes against the specification and reports to the Human Tutor’s AI Assistant.

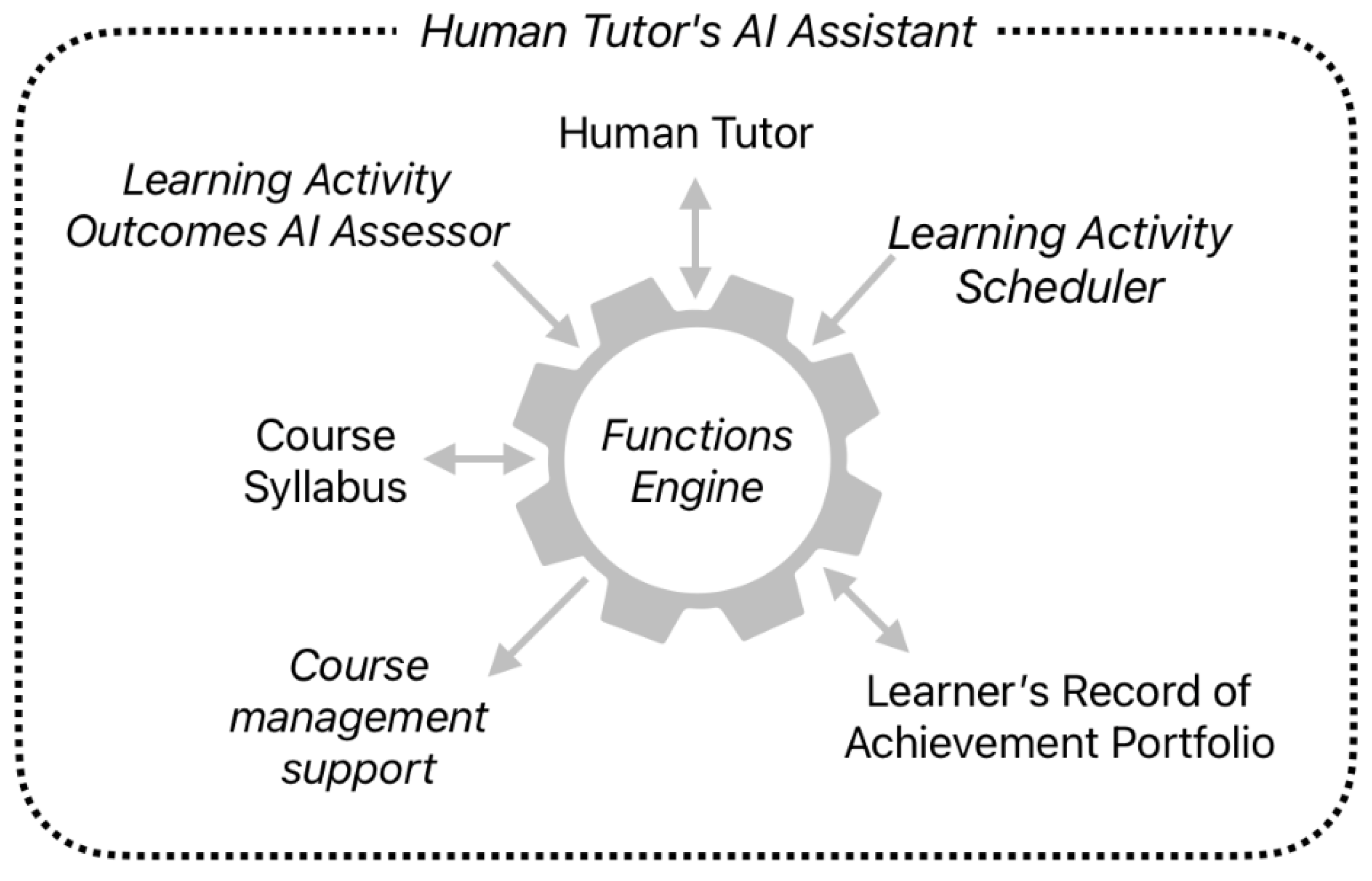

- The Human Tutor’s AI Assistant reports to the Human Tutor and forwards evidence of competence levels to the Learner’s Record of Achievement Portfolio. This is then available to external systems for academic warranting and awards.

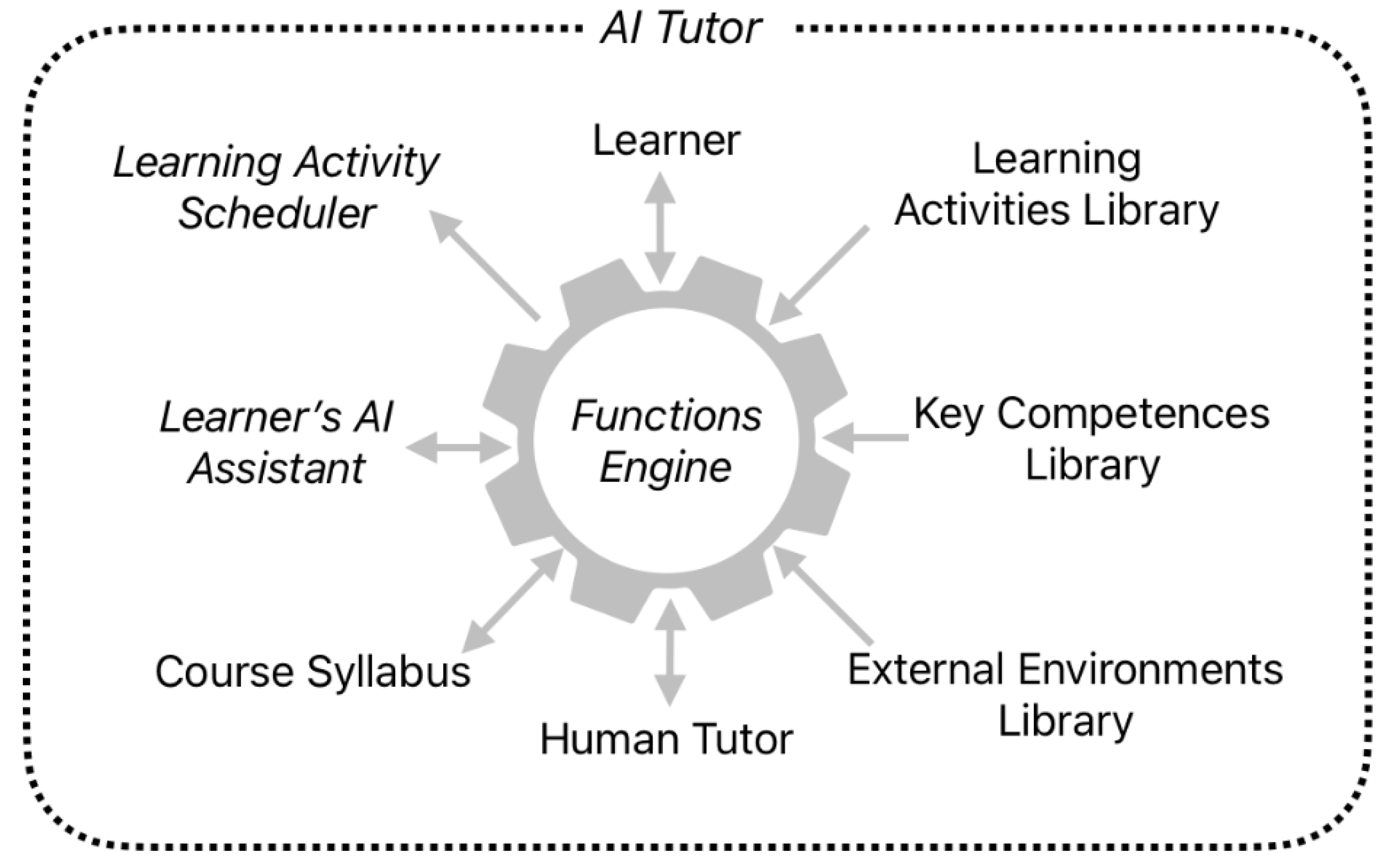

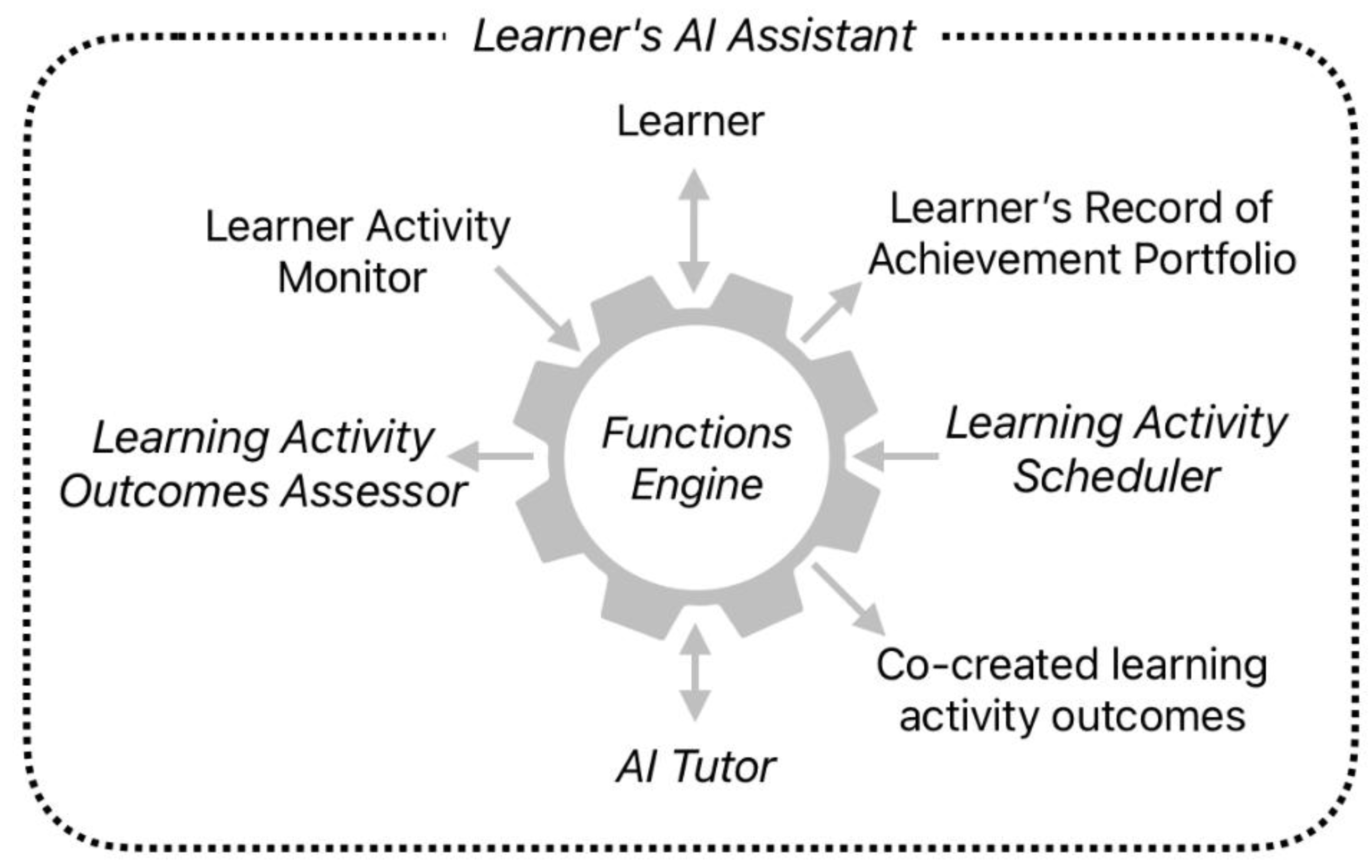

5.3. Functions of AI Agents in the HCLS

5.3.1. Functions of the AI Tutor

5.3.2. Functions of the Learner’s AI Assistant

5.3.3. Functions of the Human Tutor’s AI Assistant

5.3.4. Functions of the Learning Activity Scheduler

5.3.5. Functions of the Learning Activity Outcomes Assessor

5.4. Feedback Paths Within the HCLS

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Evaluation of HCLS Against the Six Criteria

6.2. Assumptions in the HCLS Proposition

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sublime, J.; Renna, I. Is ChatGPT Massively Used by Students Nowadays? A Survey on the Use of Large Language Models such as ChatGPT in Educational Settings. Preprint 2024, arXiv:2412.17486. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Zhang, K.; Wang, W. Embracing AI in Education: Understanding the Surge in Large Language Model Use by Secondary Students. Preprint 2024, arXiv:2411.18708. [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Chen, B.; Liu, J. TechTrends 2024, 68, 58–66. [CrossRef]

- Stein, R.M. The Half-Life of Facts: Why Everything We Know Has an Expiration Date. Quant. Financ. 2014, 14, 1701–1703. [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. The Future of Jobs; World Economic Forum: Cologny, Switzerland, 2016. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Future_of_Jobs.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- PricewaterhouseCoopers. The Fearless Future: 2025 Global AI Jobs Barometer; PwC: London, UK, 2025. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/artificial-intelligence/ai-jobs-barometer.html (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- U.S. Department of Education. Direct Assessment (Competency-Based) Programs; U.S. Department of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ed.gov/laws-and-policy/higher-education-laws-and-policy/higher-education-policy/direct-assessment-competency-based-programs (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Sturgis, C. Reaching the Tipping Point: Insights on Advancing Competency Education in New England; CompetencyWorks: USA, 2016. Available online: https://www.competencyworks.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/CompetencyWorks_Reaching-the-Tipping-Point.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Kaliisa, R.; Rienties, B.; Mørch, A.; Kluge, A. Comput. Educ. Open 2022, 3, 100073. [CrossRef]

- Datnow, A.; Park, V.; Peurach, D.J.; Spillane, J.P. Transforming Education for Holistic Student Development; Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, September 2022. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- NFER. The Skills Imperative 2035; NFER: London, UK, 2022. Available online: https://www.nfer.ac.uk/the-skills-imperative-2035 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Saito, N.; Akiyama, T. On the Education of the Whole Person. Educ. Philos. Theory 2022, 56, 153–161. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K. Educating for Wholeness, but Beyond Competences: Challenges to Key-Competences-Based Education in China. ECNU Rev. Educ. 2020, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Asakaviciūtė, V.; Valantinaitė, I.; Sederavičiūtė-Pačiauskienė, V. Filos. Sociol. 2023, 34, 328–338. [CrossRef]

- Orynbassarova, D.; Porta, S. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Emerging eLearning Technologies and Applications; 2024. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/ab1cf9d86d10bcdec408489c0ae534aa944a65f4 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Gregorcic, B.; Polverini, G.; Sarlah, A. Phys. Educ. 2024, 59, 045001. [CrossRef]

- Tapper, T.; Palfreyman, D. The Tutorial System: The Jewel in the Crown. In Oxford, the Collegiate University; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Balan, A. Law Teach. 2017, 52, 171–189. [CrossRef]

- Lissack, M.; Meagher, B. Responsible Use of Large Language Models: An Analogy with the Oxford Tutorial System. She Ji 2024, 10, 389–413.

- Cai, L.; Msafiri, M.M.; Kangwa, D. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 7191–7264. [CrossRef]

- Black, P.; Wiliam, D. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 2018, 25, 551–575. [CrossRef]

- Parmigiani, D.; Nicchia, E.; Murgia, E.; Ingersoll, M. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1366215. [CrossRef]

- Muafa, A.; Lestariningsih, W. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Religion, Science and Education 2025, 4, 195–199. Available online: https://sunankalijaga.org/prosiding/index.php/icrse/article/view/1462/1143 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Sambell, K.; McDowell, L.; Montgomery, C. Assessment for Learning in Higher Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Earl, L.M. Assessment as Learning: Using Classroom Assessment to Maximize Student Learning; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013.

- Atjonen, P.; Kontkanen, S.; Ruotsalainen, P.; Pöntinen, S. Pre-Service Teachers as Learners of Formative Assessment in Teaching Practice. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2024, 47, 267–284. [CrossRef]

- Fleckney, P.; Thompson, J.; Vaz-Serra, P. Designing Effective Peer Assessment Processes in Higher Education: A Systematic Review. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2025, 44, 386–401. [CrossRef]

- Vashishth, T.; Sharma, V.; Sharma, K.; et al. AI-Driven Learning Analytics for Personalized Feedback and Assessment in Higher Education. In Using Traditional Design Methods to Enhance AI-Driven Decision Making; IGI Global, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Winarno, S.; Al Azies, H. Int. J. Pedagogy Teach. Educ. 2024, 8, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Epp, C.; Chen, F.; Cui, Y. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 152, 108061. [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Weng, X.; Ouyang, F.; Jin, T.; Chiu, T. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2024, 21, 40. [CrossRef]

- Ilieva, G.; Yankova, T.; Ruseva, M.; et al. A Framework for Generative AI-Driven Assessment in Higher Education. Information 2025, 16, 472. [CrossRef]

- Sideeg, A. Bloom’s Taxonomy, Backward Design, and Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development in Crafting Learning Outcomes. Int. J. Linguist. 2016, 8, 158. [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, G.; McTighe, J. Understanding by Design; Merrill-Prentice-Hall: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 2005.

- Anderson, L.W.; Krathwohl, D.R. (Eds.) A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2001.

- Kamalov, F.; Santandreu Calonge, D.; Smail, L.; Azizov, D.; Thadani, D.; Kwong, T.; Atif, A. Preprint 2025, arXiv:2504.20082. [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, G. AI Agentic AI in Education: Shaping the Future of Learning; Medium Blog, 2025. Available online: https://medium.com/accredian/ai-agentic-ai-in-education-shaping-the-future-of-learning-1e46ce9be0c1 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Hughes, L.; Dwivedi, Y.; Malik, T.; et al. AI Agents and Agentic Systems: A Multi-Expert Analysis. J. Comput. Inf. Syst.2025, 1–29. [CrossRef]

- Molenaar, I. Eur. J. Educ. 2022, 57, 632–645. [CrossRef]

- Cukurova, M. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2025, 56, 469–488. [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, R.; Roumeliotis, K.I.; Karkee, M. Vibe Coding vs. Agentic Coding: Fundamentals and Practical Implications of Agentic AI. Preprint 2025, arXiv:2505.19443. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Drosos, I. Vibe Coding: Programming through Conversation with Artificial Intelligence. Preprint 2025, arXiv:2506.23253. [CrossRef]

- Järvelä, S.; Zhao, G.; Nguyen, A.; Chen, H. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2025, 56, 455–468. [CrossRef]

- Perkins, M.; Furze, L.; Roe, J.; MacVaugh, J.J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 2024, 21, 06. [CrossRef]

- Masero, R. Learning Management Systems To Learning Experience Platforms: When Does an LMS Become an LXP? eLearning Industry, 14 July 2023. Available online: https://elearningindustry.com/learning-management-systems-to-learning-experience-platforms-when-does-an-lms-become-an-lxp (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Valamis. LXP vs. LMS: Understanding the Key Differences; Valamis: 2025. Available online: https://www.valamis.com/blog/lxp-vs-lms (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Valdiviezo, A.D.; Crawford, M. Fostering Soft-Skills Development through Learning Experience Platforms (LXPs). In Handbook of Teaching with Technology in Management, Leadership, and Business; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 312–321.

- Radu, C.; Ciocoiu, C.N.; Veith, C.; Dobrea, R.C. Artificial Intelligence and Competency-Based Education: A Bibliometric Analysis. Amfiteatru Econ. 2024, 26, 220–240. [CrossRef]

- Asad, M.M.; Qureshi, A. High. Educ. Skills Work-Based Learn. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Sajja, R.; Sermet, Y.; Cikmaz, M.; Cwiertny, D.; Demir, I. Information 2024, 15, 596. [CrossRef]

- Shamsudin, N.; Hoon, T. Exploring the Synergy of Learning Experience Platforms (LXP) with Artificial Intelligence for Enhanced Educational Outcomes. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Innovation & Entrepreneurship in Computing, Engineering & Science Education; Advances in Computer Science Research, Volume 117; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2024; pp. 30–39. [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Chang, R.; Pei, S.; Chawla, N.V.; Zhang, X. Preprint 2024, arXiv:2402.01680. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Wei, X.; Chen, G.; Shen, H.; et al. Generative Multi-Agent Collaboration in Embodied AI: A Systematic Review. Preprint 2025, arXiv:2502.11518. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.-H.; Li, R.; Zhou, Y.; Qi, C.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Jiang, B.; Wu, Y. AI Agent for Education: Von Neumann Multi-Agent System Framework. Preprint 2024, arXiv:2501.00083. [CrossRef]

- Leslie, D. Understanding Artificial Intelligence Ethics and Safety: A Guide for the Responsible Design and Implementation of AI Systems in the Public Sector; The Alan Turing Institute: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, J. Intrinsic Self-Correction in Generative Language Models via Data Pipeline and Partial Answer Masking. Preprint 2024, arXiv:2401.07301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, M. Toward Self-Correcting Hybrid AI Systems: Integrating LLMs with Deterministic Classical Systems. SSRN Preprint 2025. [CrossRef]

- Quantzig. How Automated Quality Management Is Shaping the Future of Business; Quantzig: Mumbai, India, 2025. Available online: https://www.quantzig.com/… (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Lamprecht, E. The Difference between UX and UI Design; CareerFoundry Blog: 2025. Available online: https://careerfoundry.com/… (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Luo, Y. Designing with AI: A Systematic Literature Review on the Use, Development, and Perception of AI-Enabled UX Design Tools. Adv. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2025, 2025, 3869207. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Almeida, D.; Wainwright, C.; Mishkin, P.; Zhang, C.; Agarwal, S.; Slama, K.; Ray, A.; et al. Training Language Models to Follow Instructions with Human Feedback. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 27730–27744. [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, D.M.; Stiennon, N.; Wu, J.; Brown, T.B.; Radford, A.; Amodei, D.; Christiano, P. Fine-Tuning Language Models from Human Preferences. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2019, 32. [CrossRef]

| Feature | GenAI | AgenticAI |

| Autonomy | Acts in response to human input | Acts autonomously in response to learner and environment |

| Workflow | Automates given workflow processes | Optimises and evolves new workflow processes |

| Decision-making | Makes decisions on the basis of predictive learning analytics data | Employs self-learning for proactive decision-making |

| AI Tutor roles | ‘Secretarial support’ and dialogic engagement | Adapting and personalising activities and curriculum for the learner |

| Level 1 | No use of AI |

| Level 2 | AI used for brainstorming, creating structures, and generating ideas |

| Level 3 | AI-assisted editing, improving the quality of student created work |

| Level 4 | Use of AI to complete certain elements of the task, with students providing a commentary on which elements were involved |

| Level 5 | Full use of AI as ‘co-pilot’ in a collaborative partnership without specification of which elements were wholly AI generated |

| AgenticAI support for individual working | AgenticAI support for team working |

| Curating student’s study activity with notes, summaries, diary management and links to resources | Curating information and resources, team communications and liaison to support students’ team working. |

| Providing Socratic tutoring and dialogic formative assessment | Providing Socratic tutoring and dialogic formative assessment |

| Checking and improving the quality of student created work | Identifying and curating team working and improving the quality of collaborative achievements |

| Human-agenticAI co-creation between student and AI tutor | Supporting peer evaluations of collaborative working; engaging in ‘hybrid human-AI shared regulation in learning’ (HASRL) |

| Activity | PBL | Projects | Research | Teamwork | Presentations | Viva voce |

| Flipped classroom /blended | ||||||

| Individual online activity | Level 2 | |||||

| Collaborative online activity | ||||||

| Workplace / simulation / gaming | Level 4 | |||||

| Laboratory /workshop / studio |

| Function | Learning Management Systems | Learning Experience Platforms |

| Locus of control | Tutor/Administrator control. Cognitivist orientation in focus on content delivery and management. | Learner control. Constructivist orientation in focus on learner experience and engagement. |

| Personalisation | Limited personalisation of content and tasks. | AI-driven personalisation of content and activities, based on user preferences and behaviour. |

| Social & collaborative orientation |

Limited social interaction features. | Flexible opportunities for social and collaborative learning. |

| Code | Criterion | Structures, Interactions and Processes |

| A | Dialogic engagement and formative assessment | Interactions and processes between the Learner, the AI Tutor and the Learner’s AI Assistant to enable support and engagement. |

| B | Adaptive and personalised activities to empower the learner | Interactions and processes between the AI Tutor, the Learner’s AI Assistant and the Learning Activity Scheduler to select and cue suitable activities to facilitate mastery by the Learner. |

| C | Human-agenticAI and co-created learning | Interactions and processes between the Learner, the Learner’s AI Assistant and the AI Tutor to provide partnership in the co-creation of learning activity outcomes. |

| D | Develop personal and collaborative skills and competences in diverse environments | Personal and social experiences of collaborative learning in diverse environments. Interactions and processes between the Learning Activity Outcomes Assessor and adjacent agents to assess co-created learning activity outcomes against key competences and external environments criteria (Table 4). |

| E | Ethical compliance | Interactions and processes between the Human Tutor’s AI Assistant and the Human Tutor to manage the ethical compliance of learning activities and external environments to authoritative guidelines (Section 5.3.1). |

| F | Employment of self-correcting, generative embodied multi-agent AI frameworks | Structures supporting five forms of internal self-correction (Section 5.4). External quality management feedback to the Course Syllabus and libraries. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).