Submitted:

14 August 2025

Posted:

19 August 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Mechanism of the ‘Genetic Zipper’ Method

2.1. CUAD Biotechnology: Step-by Step Action

- Step 1: Arrest of rRNA function, leading to hypercompensation.

- Step 2: Enzymatic degradation of rRNA by DNA-guided rRNase, such as rRNase H1 (Gal’chinsky et al., 2024; Kumar et al., 2025).

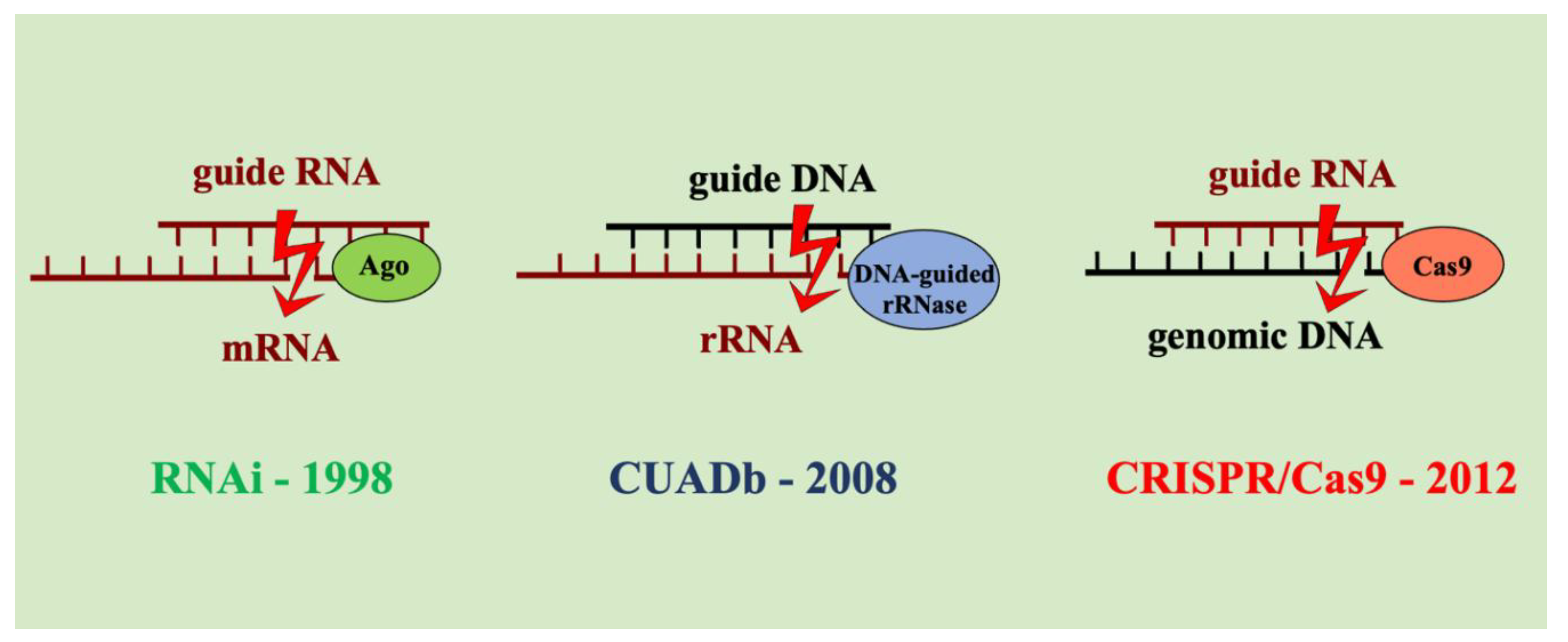

2.2. Comparison with RNAi and CRISPR/Cas

- CUADb is one of three antisense technologies alongside RNAi and CRISPR/Cas.

- All involve duplex formation with unmodified nucleic acids and nuclease-mediated gene silencing: RNAi: guide RNA–mRNA (Argonaute); CUADb: guide DNA–rRNA (DNA-guided rRNase); CRISPR/Cas: guide RNA–DNA (Cas proteins) (Kumar et al., 2025).

2.3. Use of DNAInsector for Oligo Design

- DNAInsector generates target oligonucleotides in ~10 seconds (DNAInsector, 2025).

- Simplifies oligo pesticide design, making it accessible even to non-specialists.

3. Practical Implementation and Application Strategy

3.1. Selection of Pest Targets

- 12 DNA pesticides developed for important pests (mostly Sternorrhyncha and 1 spider mite), chosen due to experimental precedence (Oberemok et al., 2024a).

3.2. Oligo Pesticide Application Methods and Dosages

- Application via cold fogger or backpack sprayer using 10–20 micron droplets.

- Dosage: Trees: 10–12 g oligo in 180–200 L water per hectare (400–500 trees); Bushes/grasses: 9–10 g in 180–200 L (Oberemok et al., 2025c).

3.3. Oligo Pesticide Application Methods and Dosages

- Pesticides are primarily contact-based, not systemic. Direct contact with pest integument is required (Oberemok et al., 2025c).

4. Case Studies: Proposed Oligonucleotide Pesticides

4.1. Selection of Insect Pests

- 12 pests from 5 continents, including hemipterans like Myzus persicae, Diaphorina citri, Planococcus citri, and the spider mite Panonychus ulmi.

4.2. Pest-Specific Oligo Design and Targets

- All target 18S or 28S rRNA using 11-nt antisense DNA sequences (Table 1).

4.3. Global Representation of Species

- Origin of pests illustrated in Figure 2.

- Species include those affecting apples, potatoes, citrus, coffee, and forest trees (e.g., Adelges tsugae, Paracoccus marginatus) (Soltis et al., 2014; Buzzetti et al., 2015; García Morales et al., 2016; Alba-Tercedor et al., 2021; Kar et al., 2023).

5. Advantages of the ‘Genetic Zipper’ Method

5.1. Cost and Ease of Synthesis

- CUADb is more cost-effective than RNAi and CRISPR/Cas technologies (Oberemok et al., 2024c; 2024d).

5.2. Safety and Environmental Benefits

- Low carbon footprint, biodegradable, safe for non-target species (Gal’chinsky et al., 2023; Oberemok et al., 2024b).

5.3. High Target Specificity

- Antisense oligos designed for specific rRNA sequences reduce off-target impacts (Gal’chinsky et al., 2024; Oberemok et al., 2025a).

5.4. Resistance Management Potential

- Novel mode of action may help prevent development of target-site resistance (Oberemok et al., 2024c).

5.5. Predictive Design Using Related Species

- Effectiveness can be predicted for untested species using phylogenetic proximity (Oberemok et al., 2024a; Gavrilova et al., 2025).

6. Advantages of the ‘Genetic Zipper’ Method

6.1. Limited Pest Coverage

- Proven mainly for hemipterans and spider mites; broader validation is needed (Gavrilova et al., 2025).

6.2. Off-Target and Specificity Concerns

- Requires careful design to avoid unintended effects (Kumar et al., 2025).

6.3. Delivery System Limitation

- Field delivery methods are still being optimized (Oberemok et al., 2025).

6.4. Risk of Resistance Evolution

- New resistance mechanisms may eventually emerge (Gal’chinsky et al., 2024).

6.5. Production and Cost Issue

- While cheaper than some RNA-based tools, it still needs specialized synthesis setups (Hemant et al., 2025).

7. Conclusion and Future Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Abubakar, M., Koul, B., Chandrashekar, K., Raut, A., Yadav, D. (2022). Whitefly (Bemisia tabaci) management (WFM) strategies for sustainable agriculture. Agriculture. 12(9): 1317. [CrossRef]

- Alba-Tercedor, J., Hunter, W.B., Alba-Alejandre, I. (2021). Using micro-computed tomography to reveal the anatomy of adult Diaphorina citri Kuwayama (Insecta: Hemiptera, Liviidae) and how it pierces and feeds within a citrus leaf. Sci Rep. 11(1):1358. [CrossRef]

- Ali, J., Bayram, A., Mukarram, M., Zhou, F., Karim, M.F., Hafez, M. M. A. et al. (2023). Peach–Potato Aphid Myzus persicae: Current Management Strategies, Challenges, and Proposed Solutions. Sustainability. 15:11150. [CrossRef]

- Alloui-Griza, R., Cherif, A., Attia, S., Francis, F., Lognay, G. C., Grissa-Lebdi, K. (2022). Lethal Toxicity of Thymus capitatus Essential Oil Against Planococcus citri (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) and its Coccinellid Predator Cryptolaemus montrouzieri (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Journal of Entomological Science. 57(3):425-435. [CrossRef]

- Assouguem, A., Lahlali, R., Joutei, A. B., Kara, M., Bari, A., Aberkani, K., et al. (2024). Assessing Panonychus ulmi (Acari: Tetranychidae) Infestations and Their Key Predators on Malus domestica Borkh in Varied Ecological Settings. Agronomy. 14:457. [CrossRef]

- Avila, C. A., Marconi, T. G., Viloria, Z., Kurpis, J., Del Rio, S. Y. (2019). Bactericera cockerelli resistance in the wild tomato Solanum habrochaites is polygenic and influenced by the presence of Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum. Sci Rep. 2019 Oct 1;9(1):14031. [CrossRef]

- Buzzetti, K. A., Chorbadjian, R. A. Fuentes-Contreras, E., Gutiérrez, M., Ríos, J. C., Nauen, R. (2015). Monitoring and mechanisms of organophosphate resistance in San Jose scale, Diaspidiotus perniciosus (Hemiptera: Diaspididae). J. Appl. Entomol. 140:507–516. [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Asencio, I., Dietrich, C. H., Zahniser, J. N. (2023). A new invasive pest in the Western Hemisphere: Amrasca biguttula (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae). The Florida Entomologist. 106(4):263–266. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48763130 [Accessed August 14, 2025].

- DNAInsector. 2025. https://dnainsector.com/?token=e870a6fc9abe44d18fdbbcf909805689 [Accessed Juny 27, 2025].

- Eleftheriadou, N., Lubanga, U. K., Lefoe, G. K., Seehausen, M. L., Kenis, M., Kavallieratos, N. G.; et al. (2023). Uncovering the Male Presence in Parthenogenetic Marchalina hellenica (Hemiptera: Marchalinidae): Insights into Its mtDNA Divergence and Reproduction Strategy. Insects. 14:256. [CrossRef]

- Gal’chinsky, N. V., Yatskova, E. V., Novikov, I. A., Useinov, R. Z., Kouakou, N. J., Kouame, K. F., et al. (2023). Icerya purchasi Maskell (Hemiptera: Monophlebidae) Control Using Low Carbon Footprint Oligonucleotide Insecticides. Int J Mol Sci. 24(14):11650. [CrossRef]

- Gal’chinsky, N. V.; Yatskova, E. V.; Novikov, I. A.; Sharmagiy, A. K.; Plugatar, Y. V.; Oberemok, V. V. (2024). Mixed insect pest populations of Diaspididae species under control of oligonucleotide insecticides: 3′-end nucleotide matters. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology. 200:105838. [CrossRef]

- García Morales, M., Denno, B. D., Miller, D. R., Miller, G. L., Ben-Dov, Y., Hardy, N. B. (2016). ScaleNet: A literature-based model of scale insect biology and systematics. Database. 2016:bav118. [CrossRef]

- Gavrilova, D., Grizanova, E., Novikov, I., Laikova, E., Zenkova, A., Oberemok, V., et al. (2025). Antisense DNA acaricide targeting pre-rRNA of two-spotted spider mite Tetranychus urticae as efficacy-enhancing agent of fungus Metarhizium robertsii. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 211:108297. [CrossRef]

- Gounari, S., Zotos, C. E., Dafnis, S. D., Moschidis, G., Papadopoulos, G. K. (2021). On the impact of critical factors to honeydew honey production: The case of Marchalina hellenica and pine honey. J. Apic. Res. 62:383–393. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, N. K., Phan, N. T., Biddinger, D. J. (2023). Management of Panonychus ulmi with Various Miticides and Insecticides and Their Toxicity to Predatory Mites Conserved for Biological Mite Control in Eastern U.S. Apple Orchards. Insects. 2023. 14(3):228. [CrossRef]

- Kar, A., Majhi, D. and Mishra, D. K. (2023). First report of Coccus viridis (Green) as a pest of dragonfruit in West Bengal. Pest Management in Hort. Ecosystems. 29(2):304-306.

- Karuppiah, P., Thayalan, K. J., Thangam, G. S., Eswaranpillai, U. (2025). Bio-Control Agents: A Sustainable Approach for Enhancing Soil Nutrients Use Efficiency in Farming. In: Mitra, D., de los Santos Villalobos, S., Rani, A., Elena Guerra Sierra, B., Andjelković, S. (eds) Bio-control Agents for Sustainable Agriculture . Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H., Gal’chinsky, N., Sweta, V., Negi, N., Filatov, R., Chandel, A., et al. (2025). Perspectives of RNAi, CUADb and CRISPR/Cas as Innovative Antisense Technologies for Insect Pest Control: From Discovery to Practice. Insects. 16(7):746. [CrossRef]

- Munyaneza, J. E. (2015). Zebra Chip Disease, Candidatus Liberibacter, and Potato Psyllid: A Global Threat to the Potato Industry. Am. J. Potato Res. 92:230–235. [CrossRef]

- Noller, H. F., Donohue, J. P., Gutell, R. R. (2022). The universally conserved nucleotides of the small subunit ribosomal RNAs. RNA. 28(5):623-644. [CrossRef]

- Oberemok, V. V., Laikova, E. V., Andreeva, O. A., Gal’chisnky, N. V. (2024c). Oligonucleotide insecticides and RNA-based insecticides: 16 years of experience in contact using of the next generation pest control agents. J Plant Dis Prot. 131:1837-1852. [CrossRef]

- Oberemok, V. V., Laikova, K. V. Gal’chinsky, N. V. (2024). Contact unmodified antisense DNA (CUAD) biotechnology: list of pest species successfully targeted by oligonucleotide insecticides. Front. Agron. 6:1415314. [CrossRef]

- Oberemok, V. V., Laikova, K. V., Gal’chinsky, N. V. (2025c). Toward Global Pesticide Market: Notes on Using of Innovative ’Genetic Zipper’ Method. Indian Journal of Entomology. [CrossRef]

- Oberemok, V. V., Laikova, K. V., Andreeva, O. A., Gal’chinsky, N. V. (2024b). Biodegradation of insecticides: oligonucleotide insecticides and double-stranded RNA biocontrols paving the way for eco-innovation. Front. Environ. Sci. 12:1430170. [CrossRef]

- Oberemok, V. V., Puzanova, Y. V., Gal’chinsky, N. V. (2024d). The ‘genetic zipper’ method offers a cost-effective solution for aphid control. Front Insect Sci. 4:1467221. [CrossRef]

- Oberemok, V., Gal’chinsky, N., Novikov, I., Sharmagiy, A., Yatskova, E., et al. (2025a). Ribosomal RNA-Specific Antisense DNA and Double-Stranded DNA Trigger rRNA Biogenesis and Insecticidal Effects on the Insect Pest Coccus hesperidum. Int J Mol Sci. 26(15):7530. [CrossRef]

- Oberemok, V., Laikova, K., Andreeva, O., Dmitrienko, A., Rybareva, T., Ali, J., et al. (2025b). DNA-Programmable Oligonucleotide Insecticide Eriola-11 Targets Mitochondrial 16S rRNA and Exhibits Strong Insecticidal Activity Against Woolly Apple Aphid (Eriosoma lanigerum) Hausmann.Int J Mol Sci. 26(15):7486. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A. K., Upadhyay, S. K., Mishra, M., Saurabh, S., Singh, R., Singh, H., et al. (2016). Expression of an insecticidal fern protein in cotton protects against whitefly. Nature Biotechnology. 34(10):1046–1051. [CrossRef]

- Smit, S., Widmann, J., Knight, R. (2007). Evolutionary rates vary among rRNA structural elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 35(10):3339-54. [CrossRef]

- Soltis, N. E., Gomez, S., Leisk, G. G., Sherwood, P., Preisser, E. L., Bonello, P., et al. (2014). Failure under stress: the effect of the exotic herbivore Adelges tsugae on biomechanics of Tsuga canadensis. Ann Bot. 113(4):721-30. [CrossRef]

- Villavicencio-Vásquez, M., Espinoza-Lozano, F., Espinoza-Lozano, L., Coronel-León, J. (2025) Biological control agents: mechanisms of action, selection, formulation and challenges in agriculture. Front. Agron. 7:1578915. [CrossRef]

| Common name; Latin name; plant hosts | GenBank ID | Target rRNA | Sequence of oligonucleotide pesticide (5’-3’) | Reference |

| Hemlock woolly adelgid; Adelges tsugae (Annand, 1928); feeds on the long-lived conifer eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) | CM099572.1 |

18S | GCAAAAAACAT | (Soltis et al., 2014) |

| San Jose scale; Diaspidiotus perniciosus (Comstock, 1881); feeds on the apple, peach, nectarine, pear, plum and cherry trees | KY085528.1 |

28S | GGGTAAACGGA | (Buzzetti et al., 2015) |

| Papaya mealybug; Paracoccus marginatus (Williams and Granara de Willink, 1992); feeds on a wide variety of taxa, with host plant records for 158 genera in 51 families | AY427410.1 |

28S | GCATGAATGGA | (García Morales et al., 2016) |

| Asian citrus psyllid; Diaphorina citri (Kuwayama, 1908); feeds on the citrus trees | XM_008481222.3 |

28S | GGTTTCTGATT | (Alba-Tercedor et al., 2021) |

| Indian cotton jassid; Amrasca devastans (Ishida, 1913); feeds on the cotton, both cultivated and wild, and eggplant | MF101773.1 |

28S | GGTATCAAAAT | (Cabrera-Asencio et al., 2023) |

| Soft green scale; Coccus viridis (Green, 1889); feeds on the wide range of important crop plants are attacked, including arabica and robusta coffee, citrus, tea, mango, cassava and guava | KP189543.1 |

28S | GGAATTCAGGA | (Kar et al., 2023) |

| Citrus mealybug; Planococcus citri (Risso, 1813); feeds mainly on the citrus orchards and nurseries | XM_065345195.1 |

28S | GCTATATGCTT | (Alloui-Griza et al., 2022) |

| Tobacco whitefly; Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius, 1889); feeds with a broad range of host plants including tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.), eggplant (Solanum melongena L.), okra (Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench), cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.), pepper (Capsicum spp.), potato (Solanum tuberosum L.), soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.), cauliflower (Brassica oleracea L.), cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz), cotton (Gossypium spp.), and several other crops of great economic importance | XM_019043890.2 |

28S | GGAAAATGGTC | (Shukla et al. 2016; Abubakar et al. 2022) |

| European red spider mite; Panonychus ulmi (Koch, 1836); feeds various tree and small fruit crops, including apples (Malus domestica (Suckow) Borkh.) | AB926333.1 |

28S | GGTGTAGCATA | (Joshi et al., 2023; Assouguem et al., 2024) |

| Green peach aphid; Myzus persicae (Sulzer, 1776); feeds on over 40 plant families including Apiaceae (carrot, Daucus carota (Hoffmann)); Asteraceae (lettuce, Lactuca sativa (Linnaeus); artichoke, Cynara cardunculus (L.)); Amaranthaceae (beet, Beta vulgaris (L.); spinach, Spinacia oleracea (L.)); Brassicaceae (broccoli, Brassica oleracea var. italica (L.); brussels sprouts, Brassica oleracea var. gemmifera; cabbage, Brassica oleracea var. capitata (L.) etc. | XM_022312381.1 |

28S | GGCTTGAAAAT | (Ali et al., 2023) |

| Marchalina hellenica (Gennadius, 1883); feeds on the sap of pine trees (Pinus spp.) | EU087875.1 |

28S | GCGGGGAAAGA | (Gounari et al., 2021; Eleftheriadou et al., 2023) |

| Potato psyllid; Bactericera cockerelli (Šulc, 1909); feeds on the potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) and vein-greening in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) |

GQ249866.1 |

28S |

GGAAGAACCCA | (Munyaneza, 2015; Avila et al., 2019) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).