Submitted:

17 August 2025

Posted:

19 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

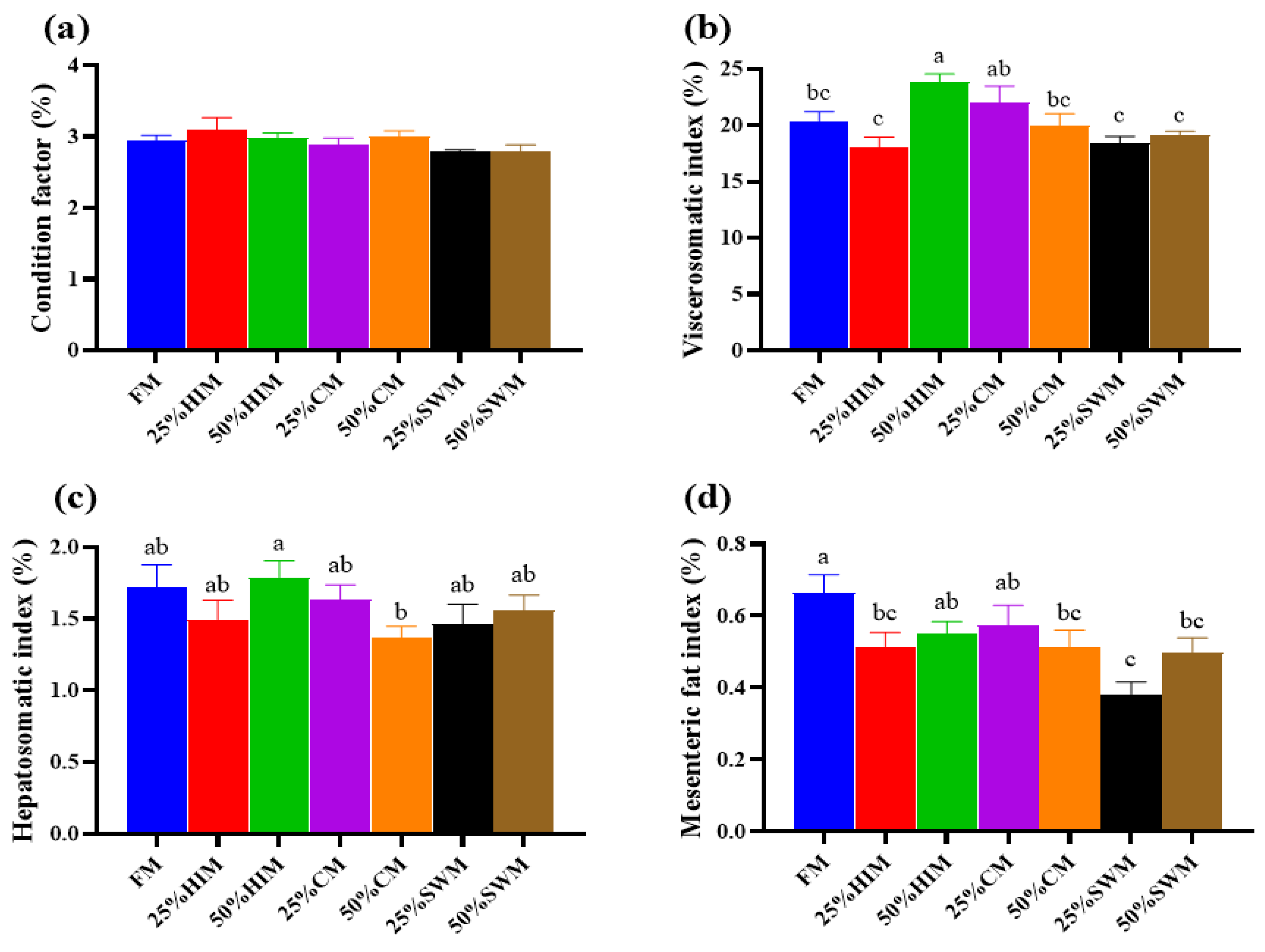

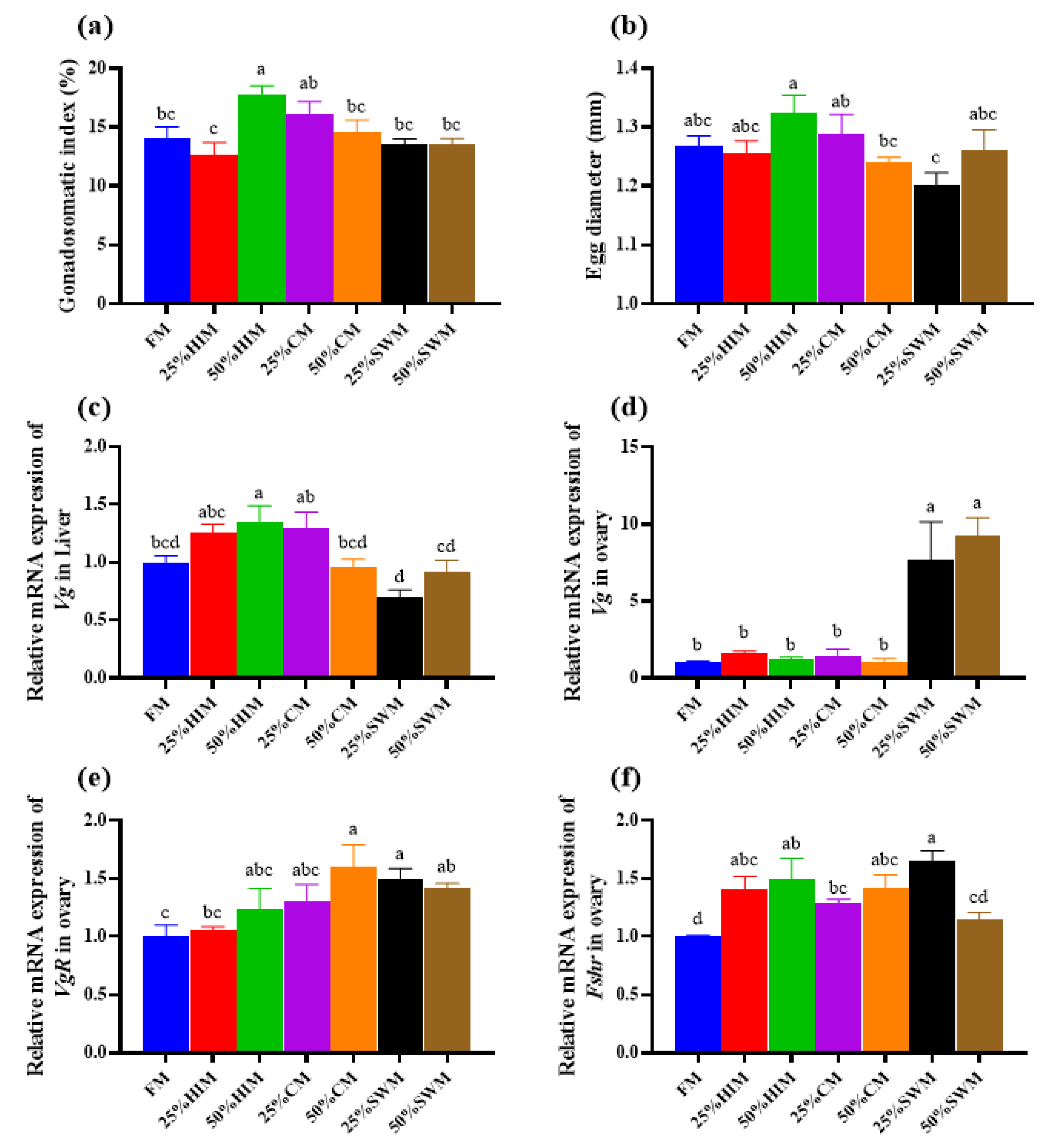

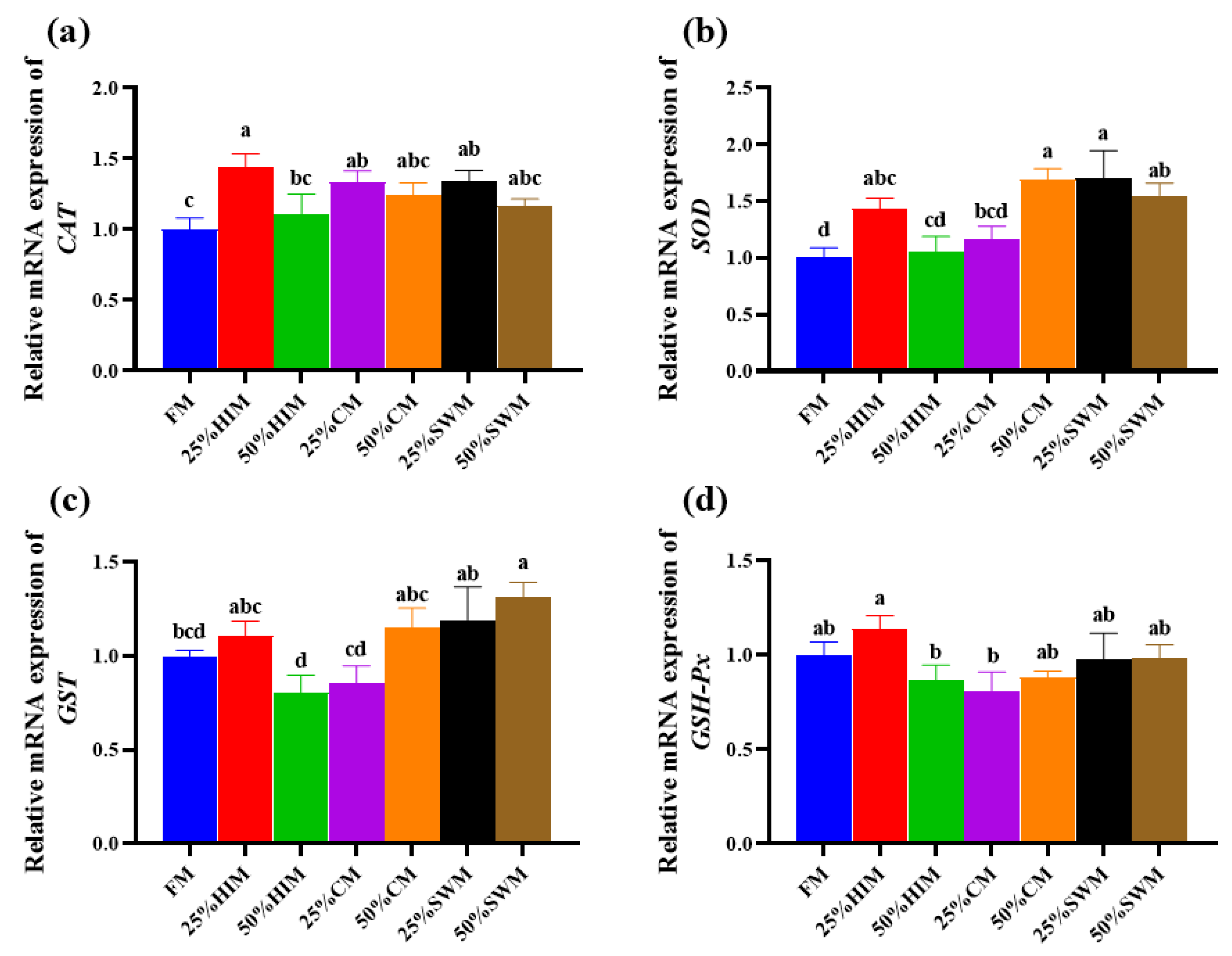

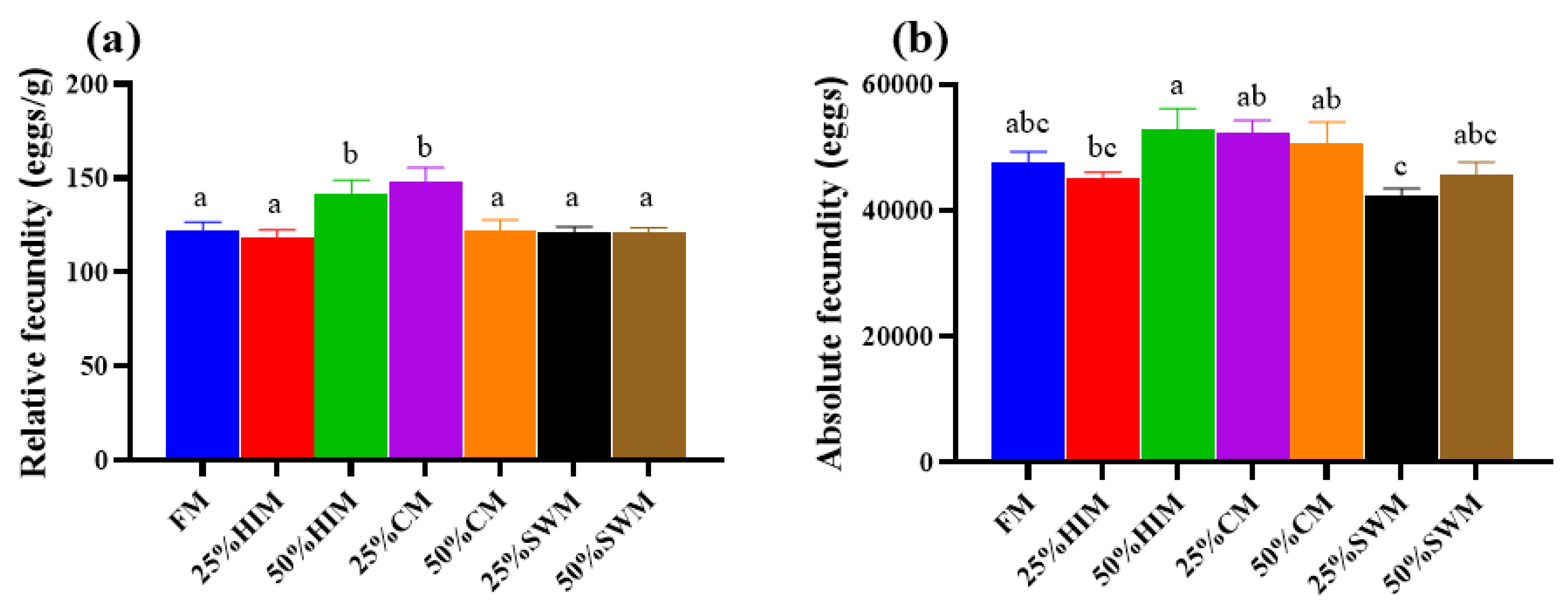

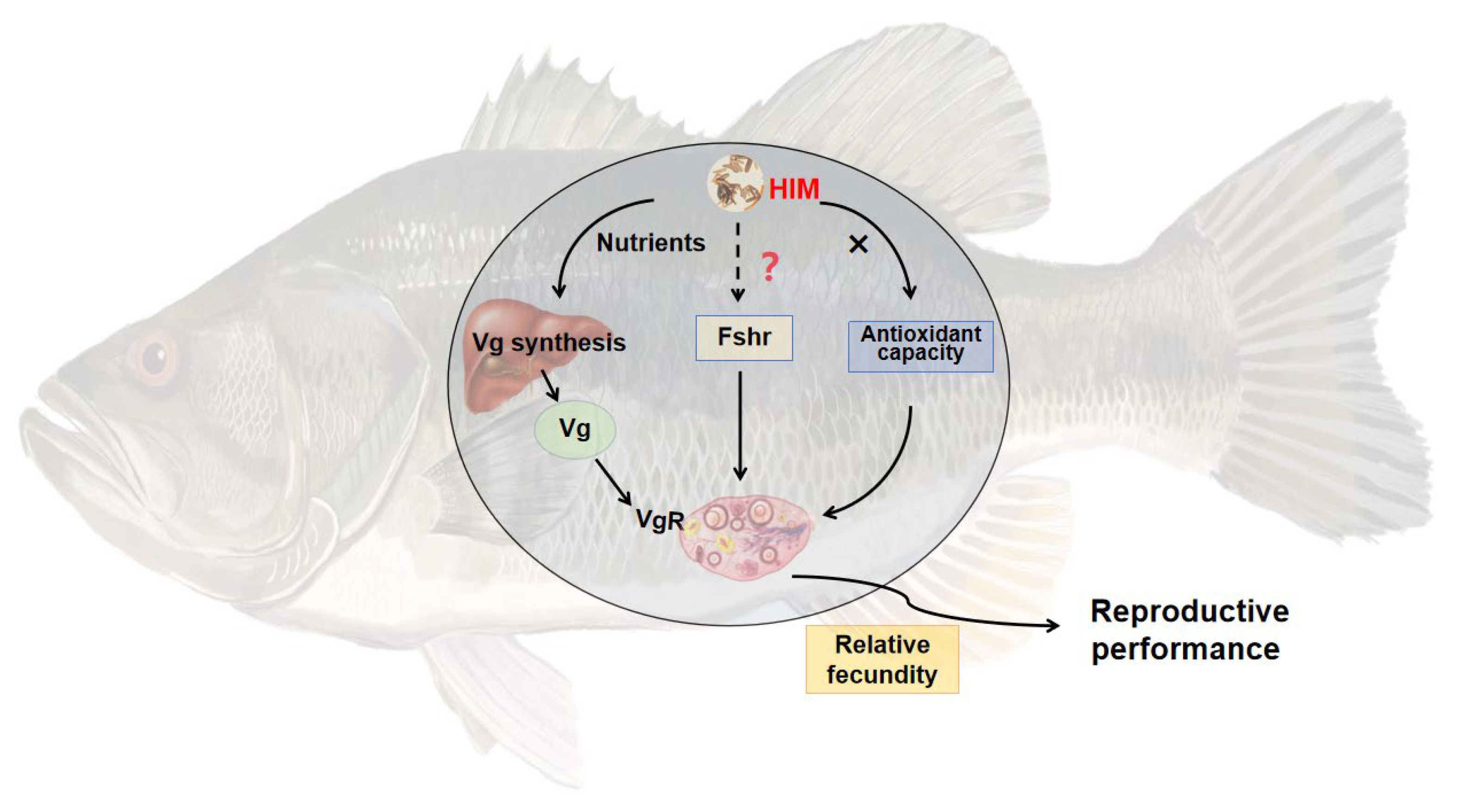

To investigate the effects of three protein sources—Hermetia illucens larvae meal (HIM), Chlorella meal (CM), and Stickwater meal (SWM)—on ovarian development in largemouth bass broodstock, these protein sources were used to replace 0% (control group FM, containing 40% fishmeal), 25%, and 50% of the fishmeal in the diet. A total of seven isonitrogenous and isolipidic diets were formulated (FM, 25% HIM, 50% HIM, 25% CM, 50% CM, 25% SWM, and 50% SWM). Healthy female fish with an initial body weight of 353.57 ± 28.12 g were fed these diets for eight weeks. The results showed that the viscerosomatic index, gonadosomatic index, and egg diameter of broodstock in the 50% HIM group were significantly higher than those in the FM group. The relative fecundity of broodstock in the 50% HIM and 25% CM groups was significantly higher than in other groups. The relative mRNA expression of hepatic vitellogenin (Vg) was significantly upregulated in the 50% HIM group, while the relative mRNA expression of Vg and vitellogenin receptor (VgR) in the ovary was significantly upregulated in the 25% SWM and 50% SWM groups. In conclusion, replacing 50% of the fishmeal in the diet with Hermetia illucens larvae meal can enhance ovarian development in largemouth bass broodstock by increasing the gonadosomatic index, and relative fecundity, and upregulating the expression of genes related to vitellogenin synthesis (Vg).

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Diets

2.2. Feeding Trial and Sampling

2.3. Proximate Nutrient Composition

2.4. Gene Expression

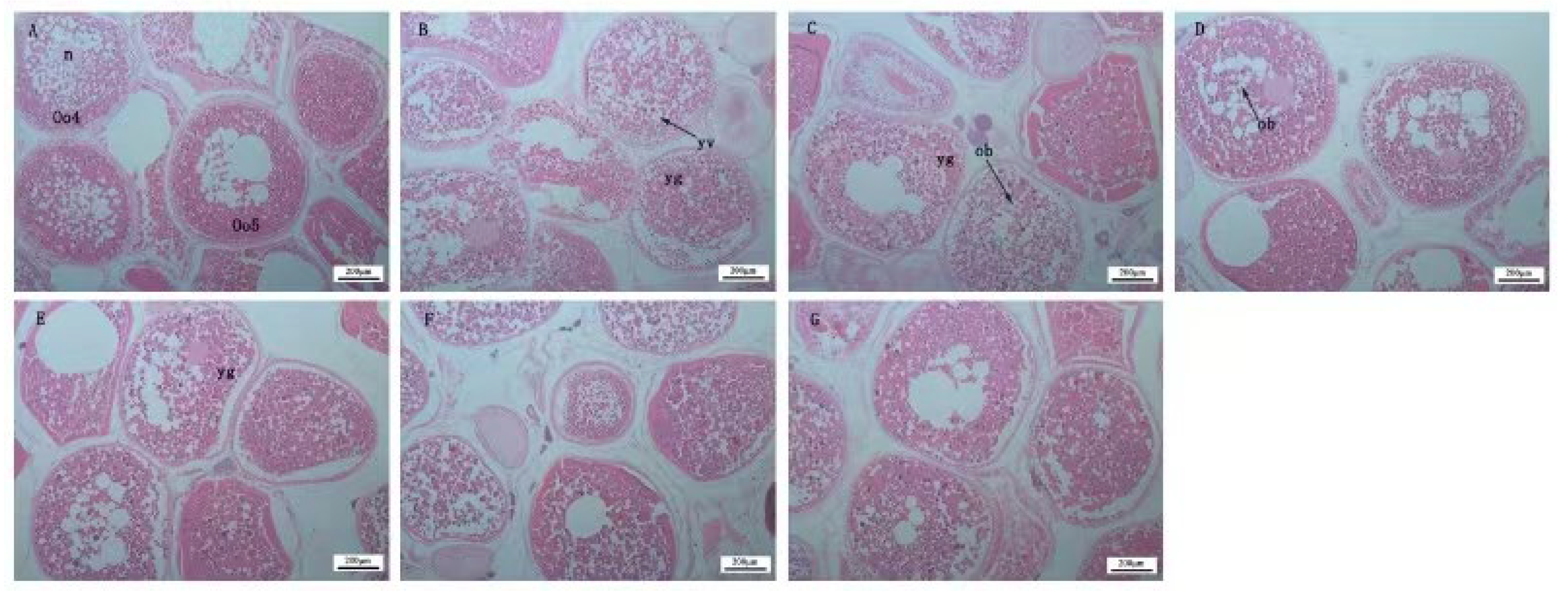

2.5. Histological Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Dietary Protein Sources on Growth Performance of Female Largemouth Bass Broodstock

3.2. Effects of Dietary Protein Sources on Ovarian Development of Female Largemouth Bass Broodstock

3.3. Effects of Dietary Protein Sources on Antioxidant Capacity of Ovary in the Female Largemouth Bass Broodstock

3.4. Effects of Dietary Protein Sources on the Reproductive Capacity of Female Largemouth Bass Broodstock

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HIM | Hermetia illucens larvae meal |

| CM | Chlorella meal |

| SWM | Stickwater meal |

| FM | Fish meal |

| Vg | Vitellogenin |

| VgR | Vitellogenin receptor |

| E2 | Estradiol 2 |

| PROG | Progesterone |

| CF | Condition factor |

| VSI | Viscerosomatic index |

| HIS | Hepatosomatic index |

| MFI | Mesenteric fat index |

| GSI | Gonadosomatic index |

| RF | Relative fecundity |

| AF | Absolute fecundity |

| CAT | Catalase |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| GST | Glutathione S-transferase |

| GSH-Px | Glutathione peroxidase |

| Fshr | Follicle-stimulating hormone receptor |

| FSH | Follicle stimulating hormone |

References

- Abdel-Moez, A.M.; Ali, M.M.; El-Gandy, G.; Mohammady, E.Y.; Jarmołowicz, S.; El-Haroun, E.; Elsaied, H.E.; Hassaan, M.S. Effect of including dried microalgae Cyclotella menegheniana on the reproductive performance, lipid metabolism profile and immune response of Nile tilapia broodstock and offspring. Aquac. Rep. 2024, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, C.V.; Yilmaz, O. Vitellogenesis and yolk proteins, fish. Encyclopedia of reproduction 2018, 6, 266–277. [Google Scholar]

- Youneszadeh-Fashalami, M.; Salati, A.P.; Keyvanshokooh, S. Comparison of proteomic profiles in the ovary of Sterlet sturgeon (Acipenser ruthenus) during vitellogenic stages. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D: Genom. Proteom. 2018, 27, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, Y.; Wong, N.-K.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, C.; Wu, X.; Ren, C.; Luo, P.; Jiang, X.; Ji, J.; Wu, X.; et al. Vitellogenin Receptor (VgR) Mediates Oocyte Maturation and Ovarian Development in the Pacific White Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Yin, Y.; Fan, H.; Zhou, Q.; Jiao, L. Arginine Promoted Ovarian Development in Pacific White Shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei via the NO-sGC-cGMP and TORC1 Signaling Pathways. Animals 2024, 14, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, X.; Jiao, L.; Wang, J.; He, Y.; Li, S.; Jin, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Q. Dietary protein regulates ovarian development through TOR pathway mediated protein metabolism in female Litopenaeus vannamei. Aquac. Rep. 2023, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Peng, D.; Chen, X.; Wu, F.; Jiang, M.; Tian, J.; Liu, W.; Yu, L.; Wen, H.; Wei, K. Effects of dietary protein levels on growth, muscle composition, digestive enzymes activities, hemolymph biochemical indices and ovary development of pre-adult red swamp crayfish (Procambarus clarkii). Aquac. Rep. 2020, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Fei, S.; Duan, Y.; Liu, C.; Liu, H.; Han, D.; Jin, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Xie, S. Effects of dietary protein level on the growth, reproductive performance, and larval quality of female yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco) broodstock. Aquac. Rep. 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Long, F.; Ding, L.; Yao, Y.; Wu, W.; Fu, Y.; Chen, W. Effects of three different protein levels on the growth, gonad development, and physiological biochemistry of female Pengze crucian carp (Carassius auratus var. Pengze) broodstock. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1459412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, S.K.; Suma, A.Y.; Rashid, A.; Kabir, M.A.; Goh, K.W.; Kari, Z.A.; Van Doan, H.; Zakaria, N.N.A.; Khoo, M.I.; Wei, L.S. The Potential of Fermented Water Spinach Meal as a Fish Meal Replacement and the Impacts on Growth Performance, Reproduction, Blood Biochemistry and Gut Morphology of Female Stinging Catfish (Heteropneustes fossilis). Life 2023, 13, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Fei, S.; Liu, C.; Duan, Y.; Liu, H.; Han, D.; Jin, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Xie, S.; et al. Compared to Fishmeal, Dietary Soybean Meal Improves the Reproductive Performance of Female Yellow Catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco) Broodstock. Aquac. Nutr. 2023, 2023, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhao, M.; Zheng, K.; Wei, Y.; Yan, L.; Liang, M. Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) meal in the diets improved the reproductive performance of tongue sole (Cynoglossus semilaevis) broodstock. Aquac. Nutr. 2017, 23, 1287–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Tan, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, W. Effects of plant protein replacing fish meal on growth and reproduction of red swamp crayfish, Procambarus clarkii. Aquatic biology 2020, 44, 479–484. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, P. Effects of Antarctic krill meal instead of fish meal on growth and reproduction of female Monopterus albus. Master, Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai, 2022.

- Zhang, M.; Wang, S.; Gan, L.; Lin, Y.; Shao, J.; Jiang, H.; Li, M. Effects of fishmeal replacement with eight protein sources on growth performance, blood biochemistry and stress resistance in Opsariichthys bidens. Aquac. Nutr. 2021, 27, 2529–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Internation Markets for Fisherish and Aquaculture Products. Globefish Highlights 2022.

- Hua, K.; Cobcroft, J.M.; Cole, A.; Condon, K.; Jerry, D.R.; Mangott, A.; Praeger, C.; Vucko, M.J.; Zeng, C.; Zenger, K.; et al. The Future of Aquatic Protein: Implications for Protein Sources in Aquaculture Diets. One Earth 2019, 1, 316–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagawany, M.; Taha, A.E.; Noreldin, A.; El-Tarabily, K.A.; El-Hack, M.E.A. Nutritional applications of species of Spirulina and Chlorella in farmed fish: A review. Aquaculture 2021, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalamaiah, M.; Hemalatha, R.; Jyothirmayi, T. Fish protein hydrolysates: proximate composition, amino acid composition, antioxidant activities and applications: a review. Food chemistry 2012, 135, 3020–3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, M.C.; Fotedar, R.; Giridharan, B.; Saptoro, A.; Nagarajan, R.; Lau, J.; Tiong, Y.; Rowtho, V.; Selvan, C.; Tan, A.; et al. The effects of fish protein hydrolysate as supplementation on growth performance, feed utilization and immunological response in fish: A review. MATEC Web Conf. 2023, 377, 01020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Peng, K.; Hu, J.; Yi, C.; Chen, X.; Wu, H.; Huang, Y. Evaluation of defatted black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens L.) larvae meal as an alternative protein ingredient for juvenile Japanese seabass (Lateolabrax japonicus) diets. Aquaculture 2019, 507, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawski, M.; Mazurkiewicz, J.; Kierończyk, B.; Józefiak, D. Black Soldier Fly Full-Fat Larvae Meal as an Alternative to Fish Meal and Fish Oil in Siberian Sturgeon Nutrition: The Effects on Physical Properties of the Feed, Animal Growth Performance, and Feed Acceptance and Utilization. Animals 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbu, S.M.; Shoko, A.P.; Ulotu, E.E.; Luvanga, S.A.; Munyi, F.M.; John, J.O.; Opiyo, M.A. Black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens, L.) larvae meal improves growth performance, feed efficiency and economic returns of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus, L.) fry. Aquaculture, Fish and Fisheries 2022, 2, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carral, J.M.; Sáez-Royuela, M. Replacement of Dietary Fishmeal by Black Soldier Fly Larvae (Hermetia illucens) Meal in Practical Diets for Juvenile Tench (Tinca tinca). Fishes 2022, 7, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kari, Z.A.; Téllez-Isaías, G.; Hamid, N.K.A.; Rusli, N.D.; Mat, K.; Sukri, S.A.M.; Kabir, M.A.; Ishak, A.R.; Dom, N.C.; Abdel-Warith, A.-W.A.; et al. Effect of Fish Meal Substitution with Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) on Growth Performance, Feed Stability, Blood Biochemistry, and Liver and Gut Morphology of Siamese Fighting Fish (Betta splendens). Aquac. Nutr. 2023, 2023, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Liu, X.; Ma, R.; Wang, B.; Ho, S.-H.; Chen, J.; Xie, Y. Effects of substituting fish meal with Chlorella meal on growth performance, whole-body composition, pigmentation, and physiological health of marbled eel (Anguilla marmorata). Algal Res. 2024, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Ye, H.M.; Gao, Y.; Ling, S.C.; Wei, C.C.; Zhu, X. Chlorella additive increased growth performance, improved appetite and immune response of juvenile crucian carp Carassius auratus. Aquaculture research 2018, 49, 3329–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enyidi, U.D. Chlorella vulgaris as Protein Source in the Diets of African Catfish Clarias gariepinus. Fishes 2017, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, X.; Yao, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Leng, X.; Xu, H. An Evaluation of Replacing Fishmeal with Chlorella Sorokiniana in the Diet of Pacific White Shrimp (Litopenaeus Vannamei): Growth, Body Color, and Flesh Quality. Aquac. Nutr. 2022, 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, O.; Paolucci, M.; Motlagh, H.A. Dietary supplementation of Chlorella vulgaris improved growth performance, immunity, intestinal microbiota and stress resistance of juvenile narrow clawed crayfish, Pontastacus leptodactylus Eschscholtz, 1823. Aquaculture 2022, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Ye, Y.; Cai, C.; Xu, J.; Zhang, L.; Chen, K.; Huang, Y.; Xu, D. Effects of replacing fish meal with fish paste powder on growth and health of grass carp. Chinese Journal of Animal Nutrition 2015, 27, 2094–2105. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, C. Effects of low fish meal diet supplemented with marine animal protein hydrolysate on growth, feed utilization and antioxidant capacity of juvenile pearl gentian grouper (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus). Master, Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai, 2020.

- Wei, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Duan, M.; Ma, Q.; Xu, H.; Liang, M. Influence of fish protein hydrolysate on intestinal health and microbial communities in turbot Scophthalmus maximus. Aquaculture 2023, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randazzo, B.; Zarantoniello, M.; Gioacchini, G.; Giorgini, E.; Truzzi, C.; Notarstefano, V.; Cardinaletti, G.; Huyen, K.T.; Carnevali, O.; Olivotto, I. Can Insect-Based Diets Affect Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Reproduction? A Multidisciplinary Study. Zebrafish 2020, 17, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemello, G.; Zarantoniello, M.; Randazzo, B.; Gioacchini, G.; Truzzi, C.; Cardinaletti, G.; Riolo, P.; Olivotto, I. Effects of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) enriched with Schizochytrium sp. on zebrafish (Danio rerio) reproductive performances. Aquaculture 2022, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, W.F.; Castro, T.F.D.; Orlando, T.M.; Meurer, F.; Paula, D.A.d.J.; Virote, B.D.C.R.; Vianna, A.R.d.C.B.; Murgas, L.D.S. Replacing fish meal by Chlorella sp. meal: Effects on zebrafish growth, reproductive performance, biochemical parameters and digestive enzymes. Aquaculture 2020, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramoniam, T. Mechanisms and control of vitellogenesis in crustaceans. Fish. Sci. 2010, 77, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, A.; Hiramatsu, N.; Fujita, T. Vitellogenesis and choriogenesis in fishes. Fish. Sci. 2016, 82, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casarini, L.; Lazzaretti, C.; Paradiso, E.; Limoncella, S.; Riccetti, L.; Sperduti, S.; Melli, B.; Marcozzi, S.; Anzivino, C.; Sayers, N.S.; et al. Membrane Estrogen Receptor (GPER) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Receptor (FSHR) Heteromeric Complexes Promote Human Ovarian Follicle Survival. iScience 2020, 23, 101812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiu, S.H.K.; Benzie, J.; Chan, S.-M. From Hepatopancreas to Ovary: Molecular Characterization of a Shrimp Vitellogenin Receptor Involved in the Processing of Vitellogenin1. Biol. Reprod. 2008, 79, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraju, G.P.C. Reproductive regulators in decapod crustaceans: an overview. J. Exp. Biol. 2011, 214, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.J.; Tao, Y.; Li, Y.; Sayouh, M.A.; Lu, S.; Qiang, J.; Xu, P. Modulation of chronic hypoxia on ovarian structure, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in female Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquaculture 2024, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | FM | 25% HIM | 50% HIM | 25% CM | 50% CM | 25% SWM | 50% SWM |

| Ingredients | |||||||

| Fish meal | 40 | 30 | 20 | 30 | 20 | 30 | 20 |

| Hermetia illucens larvae meal | 0 | 11.7 | 23.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chlorella meal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12.3 | 24.6 | 0 | 0 |

| Stickwater meal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 18 |

| Soybean protein concentrate | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 |

| Soybean meal | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Fish oil | 3 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 3 | 3.1 |

| Soybean oil | 3 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 3 | 3.1 |

| Soybean lecithin | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Corn starch | 9 | 9.5 | 9.8 | 7.5 | 5.8 | 10 | 10.8 |

| Vitamin premix1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Mineral premix2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Ca(H2PO4)2 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Choline chloride | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Sodium carboxymethylcellulose | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Proximate composition | |||||||

| Moisture | 8.04 | 7.06 | 8.28 | 7.06 | 9.07 | 6.90 | 9.40 |

| Crude protein | 48.58 | 48.58 | 48.59 | 48.58 | 48.59 | 48.62 | 48.65 |

| Crude lipid | 10.95 | 10.85 | 10.95 | 10.85 | 10.95 | 10.88 | 11.01 |

| Ash | 12.64 | 11.81 | 10.95 | 11.23 | 9.96 | 11.72 | 10.88 |

| Items | FM | 25% HIM | 50% HIM | 25% CM | 50% CM | 25% SWM | 50% SWM |

| Amino acids | |||||||

| Arginine | 3.35 | 3.23 | 2.79 | 2.73 | 3.02 | 2.92 | 2.87 |

| Alanine | 3.34 | 3.31 | 2.99 | 2.92 | 3.50 | 3.24 | 3.34 |

| Asparagine | 2.36 | 2.23 | 2.13 | 2.04 | 2.27 | 2.18 | 2.08 |

| Glutamate | 6.49 | 6.06 | 5.13 | 5.42 | 6.07 | 6.13 | 6.09 |

| Glycine | 0.99 | 0.94 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.93 | 1.10 | 1.27 |

| Histidine | 1.52 | 1.63 | 1.51 | 1.23 | 1.41 | 1.32 | 1.34 |

| Isoleucine | 2.97 | 2.70 | 2.63 | 2.49 | 2.67 | 2.57 | 2.45 |

| Leucine | 4.85 | 4.41 | 4.24 | 4.23 | 4.68 | 4.32 | 4.09 |

| Lysine | 4.19 | 3.83 | 3.48 | 3.38 | 3.41 | 3.64 | 3.42 |

| Methionine | 1.33 | 1.12 | 0.97 | 1.04 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.01 |

| Phenylalanine | 2.56 | 2.34 | 2.22 | 2.20 | 2.43 | 2.26 | 2.18 |

| Serine | 1.59 | 1.67 | 1.52 | 1.37 | 1.60 | 1.44 | 1.50 |

| Threonine | 1.89 | 1.87 | 1.61 | 1.52 | 1.78 | 1.61 | 1.61 |

| Tyrosine | 1.81 | 1.83 | 1.88 | 1.55 | 1.67 | 1.59 | 1.43 |

| Valine | 2.77 | 2.61 | 2.57 | 2.39 | 2.69 | 2.44 | 2.36 |

| Proline | 2.31 | 2.41 | 2.31 | 2.09 | 2.33 | 2.45 | 2.81 |

| Gene name | Position | Primer sequences (5'-3') | Product length(bp) |

| β-actin | Forward | TCACAGTCCTCCTAAGCCGA | 186 |

| Reverse | GGCCCATACCAACCATCACA | ||

| GAPDH | Forward | GGTGAGGTCAAGGTTGAGGG | 90 |

| Reverse | CCACTTGATGTTAGCGGGGT | ||

| Vg | Forward | ACTCTGTGGAAAGGCTGACG | 70 |

| Reverse | ACTCTTGGTCAGGCGTTTGT | ||

| VgR | Forward | CACAAGACCTGCGGAGACAT | 99 |

| Reverse | GTTGTGGCATTCGCACTTGT | ||

| Fshr | Forward | CCATCTCAGCGGCTCTCAAG | 89 |

| Reverse | GGAGCAGGAGTTGATTGGGT | ||

| CAT | Forward | CTGCTGTTCCCGTCCTTCAT | 154 |

| Reverse | GGTAGCCATCAGGCAAACCT | ||

| SOD | Forward | GCATGTTGGAGACTTGGGGA | 104 |

| Reverse | CAATGATCGAGTACGGGCCA | ||

| GST | Forward | GGTCTCACGCTCAACCAGAA | 123 |

| Reverse | CAGCTTGACCTCAGCACTCA | ||

| GSH-Px | Forward | CGTTATTCTGGGTGTGCCCT | 166 |

| Reverse | AAACAAGGGGTGTGCATCCT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).