Submitted:

09 September 2024

Posted:

09 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Conditions

2.2. Experimental Diet Preparation

| Experimental diet | |||

| Con | SPC25 | SPC50 | |

| Ingredient (%, DM) | |||

| Low-temperature fishmeal (LT FM)a | 60.0 | 45.0 | 30.0 |

| Soy protein concentrate (SPC)b | 9.0 | 18.0 | |

| Wheat gluten | 9.5 | 14.25 | 19.0 |

| Wheat flour | 15.5 | 15.5 | 15.5 |

| Starch | 5.6 | 3.93 | 2.26 |

| Fish oil | 4.9 | 6.25 | 7.6 |

| Mono-calcium phosphate (MCP)c | 1.05 | 2.1 | |

| Vitamin C | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Mineral premixd | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Vitamin premixe | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Betaine | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Choline | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Lysine (99%) f | 0.375 | 0.75 | |

| Methionine (99%) g | 0.145 | 0.29 | |

| Nutrients (%, DM) | |||

| Dry matter | 96.3 | 96.8 | 96.3 |

| Crude protein | 53.9 | 53.1 | 52.8 |

| Crude lipid | 9.3 | 9.5 | 10.6 |

| Ash | 13.3 | 12.7 | 10.8 |

| Carbohydrateh | 23.5 | 24.7 | 25.8 |

| Gross energy (GE) (kcal/g)i | 4.800 | 4.845 | 4.992 |

2.3. Determination of Biological Indices

2.4. Biochemical Composition of the Experimental Diets and the Fish

2.5. Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. AA and FA Profiles of the Experimental Diets

3.2. Survival and Growth Performance (Table 5)

| Experimental diet | Initial weight (g/fish) |

Final weight (g/fish) |

Survival (%) | Weight gain (g/fish) | SGR (%/day) a |

| Con | 721.4±6.95 | 1112.5±28.80 | 96.3±1.79 | 390.8±24.95 | 0.31±0.016 |

| SPC25 | 729.4±5.63 | 1170.3±90.10 | 94.7±4.09 | 442.3±86.24 | 0.34±0.048 |

| SPC50 | 732.5±3.61 | 1131.9±24.47 | 96.3±2.49 | 400.6±24.29 | 0.31±0.015 |

| P–value | P > 0.9 | P > 0.9 | P > 0.05 | P > 0.9 | P > 0.05 |

3.3. Feed Availability and Biological Indices (Table 6)

| Experimental diet | DFI (%/day) a | FE b | PER c | PR (%) d | CF (g/cm3) e | VSI (%) f | HSI (%) g |

| Con | 0.48±0.018 | 0.63±0.024 | 1.16±0.045 | 37.36±1.510 | 1.04±0.247 | 3.99±0.574 | 1.47±0.282 |

| SPC25 | 0.46±0.004 | 0.70±0.074 | 1.32±0.139 | 42.62±3.703 | 1.16±0.283 | 3.59±0.263 | 1.57±0.344 |

| SPC50 | 0.44±0.009 | 0.69±0.021 | 1.30±0.039 | 42.90±1.256 | 1.04±0.083 | 3.45±0.356 | 1.44±0.150 |

| P–value | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | P > 0.5 | P > 0.9 | P > 0.6 | P > 0.8 | P > 0.9 |

3.4. Proximate Composition of Dorsal Muscle (Table 7)

| Experimental diet | Moisture | Crude protein | Crude lipid | Ash |

| Con | 72.87±0.020 | 22.44±0.240 | 2.37±0.400b | 1.57±0.005a |

| SPC25 | 72.69±0.330 | 22.26±0.500 | 2.61±0.025b | 1.55±0.025a |

| SPC50 | 71.95±0.085 | 21.91±0.045 | 4.44±0.145a | 1.50±0.005b |

| P–value | P > 0.1 | P > 0.4 | P < 0.04 | P < 0.05 |

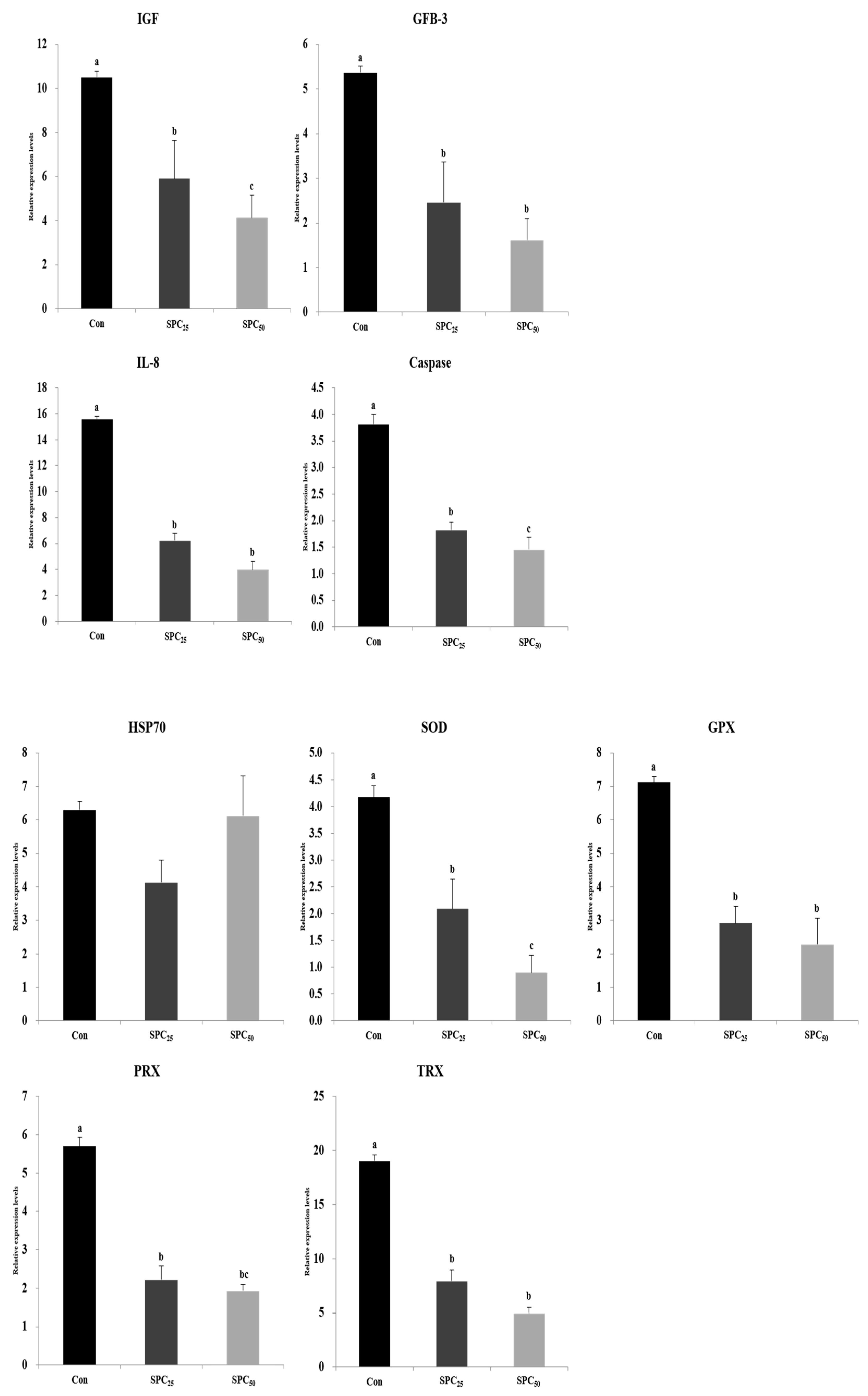

3.5. Expression Analysis of Growth, Immune, and Stress-Related Genes (Figure 1)

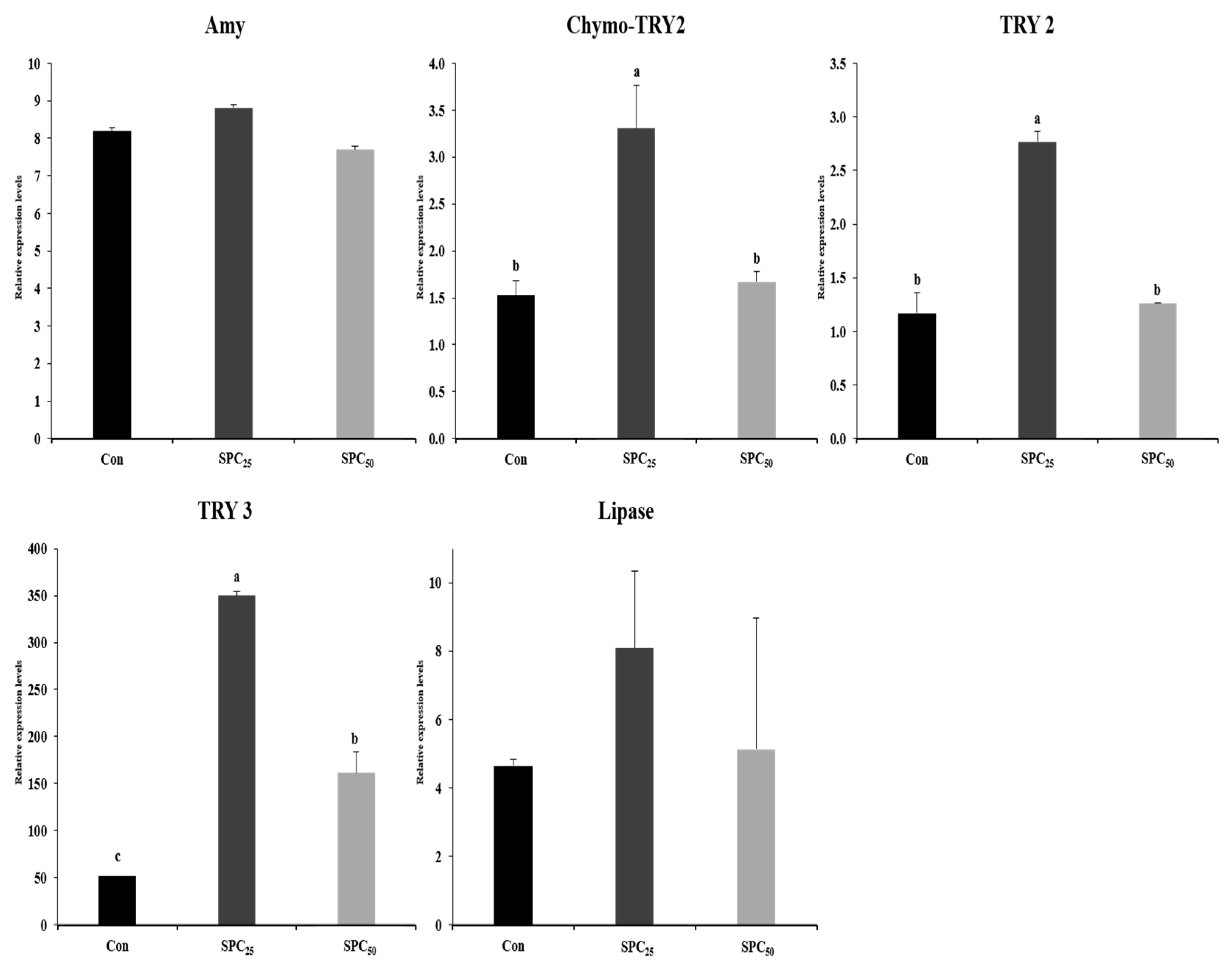

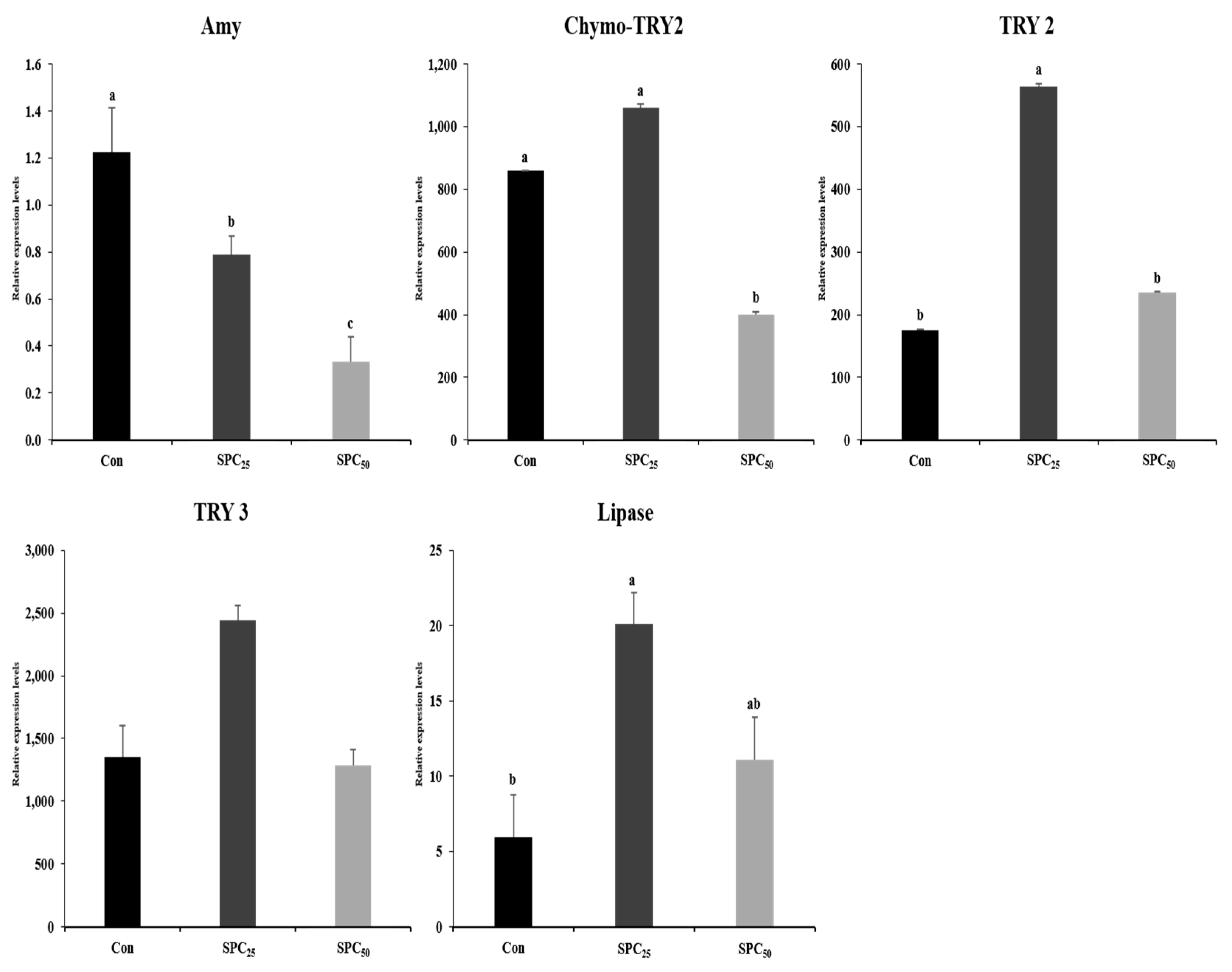

3.6. Expression Analysis of Digestive Enzyme Genes in the Stomach and Middle Intestine (Figure 2 and Figure 3)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Ethics Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Min, B.H.; Lee, J.H.; Noh, J.K.; Kim, H.C.; Park, C.J.; Choi, S.J.; Myeong, J.I. Hatching rate of eggs, and growth of larvae and juveniles from selected olive flounder, Paralichthys olivaceus. The Korean Soc. Dev. Biol. 2009, 14, 239–247.

- KOSIS, 2023. Korean Statistical Information Service, Korea. Available online: https://kostat.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10301010000&bid=225&act=view&list_no=430057. (Accessed 22 Mar. 2024).

- Hur, S.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.; Jeong, S.; Kim, K. Effects of worm-based extruded pellets on growth performance of olive flounder Paralichthys olivaceus in commercial aquafarms. Korean J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2022, 55(5), 533–540. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.M.; Lee, J.H.; Noh, J.K.; Kim, H.C.; Park, C.J.; Park, J.W.; Noh, G.E.; Kim, K.K. Temporal expression analyses of pancreatic and gastric digestive enzymes during early development of the olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus). Aquac. Res. 2017, 48, 979–989. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Baek, S.I.; Cho, S.H.; Kim, T.H. Evaluating the efficacy of partially substituting fishmeal with unfermented tuna by-product meal in diets on the growth, feed utilization, chemical composition and non-specific immune responses of olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus). Aquac. Rep. 2022, 24, 101150. [CrossRef]

- Olsen, R.L.; Hasan, M.R. A limited supply of fishmeal: impact on future increases in global aquaculture production. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 27, 120–128. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.S.; Park, J.S.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, D.G.; Hwang, J.A. Comparison of dietary protein levels on growth performance of far eastern catfish silurus asotus and water quality in biofloc technology and flow-through systems. Korean J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2022, 55(5), 541–548.

- Médale, F.; Boujard, T.; Vallée, F.; Blanc, D.; Mambrini, M.; Roem, A.; Kaushik, S.J. Voluntary feed intake, nitrogen and phosphorus losses in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) fed increasing dietary levels of soy protein concentrate. Aquat. Living Resour. 1998, 11, 239–246. [CrossRef]

- Peisker, M. Manufacturing of soy protein concentrate for animal nutrition. In: Brufau, J. (Ed.), Feed Manufacturing in the Mediterranean Region. Improving Safety: From Feed to Food. Ciheam, Zaragoza, 2001, 103-107. http://om.ciheam.org/article. php?IDPDF=1600017.

- Freitas, L.E.L.; Nunes, A.J.P.; do Carmo Sá, M.V. Growth and feeding responses of the mutton snapper, Lutjanus analis (Cuvier 1828), fed on diets with soy protein concentrate in replacement of anchovy fishmeal. Aquac. Res. 2011, 42, 866–877. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Ibrahim, U.B.; Yu, A.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y. Dried porcine soluble benefits to increase fishmeal replacement with soy protein concentrate in large yellow croaker Larimichthys crocea diet. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2023, 54, 1162–1178. [CrossRef]

- Colburn, H.R.; Walker, A.B.; Breton, T.; Stilwell, J.M.; Sidor, I.F.; Gannam, A.L.; Berlinsky, D.L. Partial replacement of fishmeal with soybean meal and soy protein concentrate in diets of Atlantic Cod. N. Am. J. Aquac. 2012, 74, 330–337. 10.1080/ 15222055.2012.676008.

- Deng, J.; Mai, K.; Ai, Q.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Xu, W.; Liufu, Z. Effects of replacing fishmeal with soy protein concentrate on feed intake and growth of juvenile Japanese flounder, Paralichthys olivaceus. Aquaculture 2006, 258, 503- 513. [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.H.; Lee, C.S.; Webster, C.D. Alternative protein sources in aquaculture diets. The Haworth Press, New York, NY. 2019, pp. 571.

- Kim, M.G.; Lee, C.; Shin, J.; Lee, B.J.; Kim, K.W.; Lee, K.J. Effects of fishmeal replacement in extruded pellet diet on growth, feed utilization and digestibility in olive flounder Paralichthys olivaceus. Korean J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2019, 52(2), 149–158. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.G.; Shin, J.; Lee, C.; Lee, B.J.; Hur, S.W.; Lim, S.G.; Lee, K.J. Evaluation of a mixture of plant protein source as a partial fishmeal replacement in diets for juvenile olive flounder Paralichthys olivaceus. Korean J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2019, 52(4), 374–381. [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.; Kim, M.G.; Shin, J.; Shin, J.; Hur, S.W.; Lee, B.J.; Lee, K.J. Evaluation of three plant proteins for fishmeal replacement in diet for growing olive flounder Paralichthys olivaceus. Korean J. Fish Aquat. Sci. 2020, 53, 464–470. [CrossRef]

- Takagi S.; Shimeno, S.; Hosokawa, H.; Ukawa, M. Effect of lysine and methionine supplementation to a soy protein concentrate diet for red sea bream Pagrus major. Fish. Sci. 2001, 67, 1088–1096.

- Kokou, F.; Rigos, G.; Kentouri, M.; Alexis, M. Effects of DL-methionine-supplemented dietary soy protein concentrate on growth performance and intestinal enzyme activity of gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata L.). Aquac. Int. 2016, 24, 257–271. [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.; Oh, D.H.; Park, S.; Seo, J.; Kim, D.; Moon, S.; Park, H.S.; Lim, S.; Lee, B.; Hur, S.; Lee, K.; Nam, T.J.; Choi, Y.H. Expression of insulin-like growth factor genes in olive flounder, Paralichthys olivaceus, fed a diet with partial replacement of dietary fishmeal. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2019, 54, 131–142. [CrossRef]

- Jang, W.J.; Hasan, M.T.; Lee, B.; Hur, S.W.; Lee, S.; Kim, K.W.; Lee, E.; Kong, I. Effect of dietary differences on changes of intestinal microbiota and immune-related gene expression in juvenile olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus). Aquaculture 2020, 527, 735442. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.W.; Wang, X.J.; Bai, S.C. Optimum dietary protein level for maximum growth of juvenile olive flounder Paralichthys olivaceus (Temminck et Schlegel). Aquac. Res. 2002, 33, 673–679. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Cho, S.H.; Kim, K. Effects of dietary protein and energy levels on growth and body composition of juvenile flounder Paralichthys olivaceus. J. World Aquacult. Soc. 2000, 31, 306–315. [CrossRef]

- AOAC, 1990. Association of Official Analytical Chemists. 15th ed. Arlington, VA, USA.

- Jeong, S.M.; Kim, N.L.; Hur, S.W.; Lee, S.H.; Bae J.H.; Kim, K.W. Effect of dietary inclusion of black soldier fly larvae Hermetia illucens meal on growth performance of starry flounder Platichthys stellatus and feed value. Korean J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2023, 56(4), 373-379. [CrossRef]

- Duncan, D.B. Multiple range and multiple F test. Biometrics 1955, 11, 1–42. [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.S.; Teshima, S.; Ishikawa, M.; Koshio, S. Methionine requirement of juvenile Japanese flounder Paralichthys olivaceus. J. World Aquacult. Soc. 2000, 31, 618–626. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Lee, S. Requirement of dietary n-3 highly unsaturated fatty acids for juvenile flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus). Aquaculture 2004, 315–323, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Nandakumar, S.; Ambasankar, K.; Ali, S.S.R.; Syamadayal, J.; Vasagam, K. Replacement of fishmeal with corn gluten meal in feeds for Asian seabass (Lates calcarifer). Aquac. Int. 2017, 25, 1495–1505. [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, K. Partial replacement of fishmeal with corn gluten meal in diets for Japanese flounder Paralichtys olivaceus. J. World Aquacult. Soc. 1999, 30, 357–363. [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.S.; Teshima, S.; Koshio, S.; Ishikawa, M. Arginine requirement of juvenile Japanese flounder Paralichthys olivaceus estimated by growth and biochemical parameters. Aquaculture 2002, 205, 127–140. [CrossRef]

- Forster, I.; Ogata, H.Y. Lysine requirement of juvenile japanese flounder Paralichthys olivaceus and juvenile red sea bream Pagrus major. Aquaculture 1998, 161, 131–142. [CrossRef]

- Goff, J.B.; Gatlin III, D.M. Evaluation of different sulfur amino acid compounds in the diet of red drum, Sciaenops ocellatus, and sparing value of cystine for methionine. Aquaculture 2004, 241, 465–477. [CrossRef]

- Farhat; Khan, M.A. Total sulfur amino acid requirement and cysteine replacement value for fingerling stinging catfish, Heteropneustes fossilis (Bloch). Aquaculture 2014, 426, 270–281. [CrossRef]

- An, W.; Dong, X.; Tan, B.; Yang, Q.; Chi, S.; Zhang, S.; Liu, H.; Yang, Y. Effects of dietary n-3 highly unsaturated fatty acids on growth, non-specific immunity, expression of some immune-related genes and resistance to Vibrio harveyi in hybrid grouper (♀ Epinephelus fuscoguttatus × ♂ Epinephelus lanceolatu). Fish. Shellfish Immunol. 2020, 96, 86–96. [CrossRef]

- Volpato, J.A.; Ribeiro, L.B.; Torezan, G.B.; da Silva, I.C.; de Oliveira Martins, I.; Genova, J.L.; de Oliveira, N.T.E.; Carvalho, S.T.; de Oliveira Carvalho, P.L.; Vasconcellos, R.S. Characterization of the variations in the industrial processing and nutritional variables of poultry by-product meal. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 101926. [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.I.; Jeong, H.S.; Cho, S.H. Replacement effect of fishmeal by plant protein sources in olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) feeds with an addition of jack mackerel meal on growth, feed availability, and biochemical composition. Aquac. Nutr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Cho, S.H. Substitution impact of tuna by-product meal for fishmeal in the diets of rockfish (Sebastes schlegeli) on growth and feed availability. Animals 2023, 13, 3586. [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Li, J.; Liu, P. Regulation of growth performance and lipid metabolism by dietary n-3 highly unsaturated fatty acids in juvenile grass carp, Ctenopharyngodon idellus. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2011, 159, 49–56. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Aminikhoei, Z.; Kim, K.; Lee, S. Growth and fatty acid composition of juvenile olive flounder Paralichthys olivaceus fed diets containing different levels and ratios of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid. Fish Aquat. Sci. 2014, 17(1), 95-103. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Seo, B.S.; Park, H.S.; Lee, B.J.; Hur, S.W.; Nam, T.J.; Lee, K.J.; Lee, S.H.; Choi, Y.H. Effect of fishmeal content in the diet on the growth and sexual maturation of olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) at a typical fish farm. Animals. 2021, 11, 2055. [CrossRef]

- Li, P.Y.; Wang, J.Y.; Song, Z.D.; Zhang, L.M.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.X.; Pan, Q. Evaluation of soy protein concentrate as a substitute for fishmeal in diets for juvenile starry flounder (Platichthys stellatus). Aquaculture 2015, 448, 578–585. [CrossRef]

- Sim, Y.J.; Cho, S.H.; Kim, K.; Jeong, S. Effect of substituting fishmeal with various by-product meals of swine-origin in diet on olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus). Acuac. Rep. 2023, 33, 101844 . [CrossRef]

- Niu, K.; Khosravi, S.; Kothari, D.; Lee, W.; Lim, J.; Lee, B.; Kim, K.; Lim, S.; Lee, S.; Kim, S. Effects of dietary multi-strain probiotics supplementation in a low fishmeal diet on growth performance, nutrient utilization, proximate composition, immune parameters, and gut microbiota of juvenile olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus). Fish. Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 93, 258–268. [CrossRef]

- Seo, B.; Park, S.; Hwang, S.; Lee, Y.; Lee, S.; Hur, S.; Lee, K.; Nam, T.; Song, J.; Kim, J.; Jang, W.; Choi, Y. Effects of decreasing fishmeal as main source of protein on growth, digestive physiology, and gut microbiota of olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus). Animals 2022, 12, 2043. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Palacios, H.; Izquierdo, M.S.; Robaina, L.; Valencia, A.; Salhi, M.; Vergara, J.M. Effect of n-3 HUFA level in broodstock on egg quality of gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata L.). Aquaculture 1995, 132, 325–327. [CrossRef]

- Furuita, H.; Tanaka, H.; Yamamoto, T.; Suzuki, N.; Takeuchi, T. Effect of high levels of n-3 HUFA in broodstock diet on egg quality and egg fatty acid composition of Japanese flounder, Paralichthys olivaceus. Aquaculture 2002, 210, 323–333. [CrossRef]

- Bae, K.; Kim, K.; Lee, S. Evaluation of rice distillers dried grain as a partial replacement for fishmeal in the practical diet of the juvenile olive flounder Paralichthys olivaceus. Fish Aquat. Sci. 2015, 18(2), 151-158. [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, E.N.; Björnsson, B.T.; Valdés, J.A.; Einarsdottir, I.E.; Lorca, B.; Alvarez, M.; Molina, A. IGF-I/PI3K/Akt and IGF-I/ MAPK/ERK pathways in vivo in skeletal muscle are regulated by nutrition and contribute to somatic growth in the fine flounder. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2011, 300(6), R1532–R1542. [CrossRef]

- Gill, N.; Higgs, D.A.; Skura, B.J.; Rowshandeli, M.; Dosanjh, B.S.; Mann, J.; Gannam, A.L. Nutritive value of partially dehulled and extruded sunflower meal for post-smolt Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) in sea water. Aquac. Res. 2006, 37(13), 1348–1359. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Moon, J.; Seo, J.; Nam, T.; Lee, K.; Lim, S.; Kim, K.; Lee, B.; Hur, S.; Choi, Y. Effect of fishmeal replacement on insulin-like growth factor-I expression in the liver and muscle and implications for the growth of olive flounder Paralichthys olivaceus. Korean J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2019, 52(2), 141–148. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jung, S. cDNA microarray analysis of viral hemorrhagic septicemia infected olive flounder, Paralichthys olivaceus: immune gene expression at different water temperature. J. Fish Pathol. 2014, 27(1), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kim, H.C.; Park, C.; Park, J.; Lee, Y.M.; Kim, W. Interleukin-8 (IL-8) expression in the olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) against viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus (VHSV) challenge. Dev. Reprod. 2019, 23(3), 231–238. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Guo, Z.; Luo, S.; Wang, A. Effects of high temperature on biochemical parameters, oxidative stress, DNA damage and apoptosis of pufferfish (Takifugu obscurus). Ecotox. Environ. Safe. 2018, 150, 190–198. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Deshmukh, R.S.; Das, S. Caspase-10 inhibits ATP-citrate lyase-mediated metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming to suppress tumorigenesis. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4255. [CrossRef]

- Jia, R.; Liu, B.; Feng, W.; Han, C.; Huang, B.; Lei, J. Stress and immune responses in skin of turbot (scophthalmus maximus) under different stocking densities. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016, 55, 131–139. [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.K.; Shinm Y.; Ju, S.; Han, S.; Choe, W.; Yoon, K.; Kim, S.S.; Kang, I. Heat shock respose and heat shock proteins: Current understanding and future opportunities human diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4209. [CrossRef]

- Currie, S.; Moyes, C.D.; Tufts, B.L. The effects of heat shock and acclimation temperature on Hsp70 and Hsp30 mRNA expression in rainbow trout: in vivo and in vitro comparisons. J. Fish Biol. 2000, 56(2), 398–408. [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Lu, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Li, Y.; Qiu, H.; Sun, P.; Ma, H.; Ding, L.; Zhou, Q. Regulation of growth, antioxidant capacity, fatty acid profiles, hematological characteristics and expression of lipid related genes by different dietary n-3 highly unsaturated fatty acids in juvenile black seabream (Acanthopagrus schlegelii). Aquaculture 2017, 471, 55–65. [CrossRef]

- Gwak, W.; Park, D.W. Developmental changes in digestive enzymes activity of black rockfish Sebastes inermis. J. Aquac. 2006, 19, 125–132.

- Hu, Y.; Yang, G.; Li, Z.; Hu, Y.; Zhong, L.; Zhou, Q.; Peng, M. Effect of dietary taurine supplementation on growth, digestive enzyme, immunity and resistant to dry stress of rice field eel (Monopterus albus) fed low fishmeal diets. Aquac. Res. 2018, 49(6), 2108–2118. [CrossRef]

- Garling, D.L.; Wilson, R.P. Optimum dietary protein to energy ratios for channel catfish fingerlings, Ictalurus punctatus. J Nutr. 1976, 106, 1368–1375. [CrossRef]

| Target | Sequence (5'-3') | Gen Bank |

| IGF | F.P = 5'-CGGCGCCTGGAGATGTACTG-3′ | AF016922.2 |

| R.P = 5'-TGTCCTACGCTCTGTGCCCT-3′ | ||

| GFB-3 | F.P = 5'-CTCAAGACCTGGAACCTCTCACTAT-3′ | KF723424.1 |

| R.P = 5'-CTCAGCTACACTTGCAAGACTTGAC-3′ | ||

| IL-8 | F.P = 5'-GTTGTTGCTGTGATGGTGCT-3′ | AB809047.1 |

| R.P = 5'-GCCGGTATCTTTCAGAGTGG-3′ | ||

| Caspase | F.P = 5'-GCACATGGACATCCTGAGTG-3′ | AB247499.1 |

| R.P = 5'-AGGCTGCTCATTTCACTGCT-3′ | ||

| HSP70 | F.P = 5'-TCCTCATGGGTGACACTTCG-3′ | AB010871.1 |

| R.P = 5'-TTGTCCTTGGTCATGGCTCT-3′ | ||

| SOD | F.P = 5'-GGGAATGTCACTGCTGGAAAA-3′ | EF681883.1 |

| R.P = 5'-CCAATAACTCCACAGGCCAGAC-3’ | ||

| GPX | F.P = 5'-GAAGGTGGATGTGAATGGGAAG-3′ | EU095498.1 |

| R.P = 5'-TCTGCCTCGATATCAATGGTAAGG-3′ | ||

| PRX | F.P = 5'-TCTCCTACAGCAAACAGCAC-3′ | DQ009987.1 |

| R.P = 5'-CCAGGAAGTGACACCATCAA-3′ | ||

| TRX | F.P = 5'-TGGACAGAGGCGAGGCTACT-3′ | XM020095833.1 |

| R.P = 5'-ACCCAAAGACCAAACCACACAC-3′ | ||

| Amy | F.P = 5'-CACTCTTCATGTGGAAGCTGGTTC -3′ | KJ908179 |

| R.P = 5'-CCATAGTTCTCAATGTTGCCACTGC -3′ | ||

| Chymo-TRY2 | F.P = 5'-ACTACACCGGCTTCCACTTC -3′ | AB029754 |

| R.P = 5'-GAACACCTTGCCAACCTTCATG -3′ | ||

| TRY2 | F.P = 5’-ATCGTCGGAGGGTATGAGTG-3′ | AB029751 |

| R.P = 5’-CATCCAGAGACTGTGCACATG-3′ | ||

| TRY3 | F.P = 5'-TATGAGTGCACGCCCTACTC -3′ | AB029752 |

| R.P = 5'-GTTCTCACAGTCCCTCTCAGAC -3′ | ||

| Lipase | F.P= 5'-ATGGGAGAAGAAAATATCTTATTTTTGA -3′ | HQ850701 |

| R.P = 5'-TACCGTCCAGCCATGTATCAC -3′ |

| Ingredients | Requirement | Experimental diet | ||||

| FM | SPC | Con | SPC25 | SPC50 | ||

| Essential amino acids (EAA) (g/kg) | ||||||

| Arginine | 36.6 | 45.5 | 20.4–21.01 | 29.4 | 27.2 | 26.3 |

| Histidine | 13.4 | 16.4 | 9.6 | 11.5 | 12.1 | |

| Isoleucine | 28.9 | 31.1 | 22.3 | 21.6 | 21.0 | |

| Leucine | 47.4 | 50.3 | 39.4 | 37.5 | 36.3 | |

| Lysine | 50.7 | 41.3 | 1.50–21.02 | 36.3 | 33.6 | 32.4 |

| Methionine | 17.7 | 6.7 | 14.4–14.93 | 13.7 | 12.3 | 11.7 |

| Phenylalanine | 25.3 | 32.1 | 22.6 | 22.8 | 23.2 | |

| Threonine | 25.8 | 24.9 | 21.7 | 19.2 | 17.7 | |

| Valine | 33.8 | 31.9 | 26.7 | 24.5 | 23.5 | |

| ∑EAA4 | 279.6 | 280.2 | 221.7 | 210.2 | 204.2 | |

| Non-essential amino acids (NEAA) (g/kg) | ||||||

| Alanine | 40.1 | 27.1 | 31.7 | 26.6 | 23.0 | |

| Aspartic acid | 59.0 | 72.6 | 44.8 | 40.8 | 38.5 | |

| Cysteine | 3.5 | 5.9 | 0.63 | 6.1 | 3.0 | 2.8 |

| Glutamic acid | 89.6 | 127.8 | 97.6 | 111.4 | 119.3 | |

| Glycine | 42.9 | 27.6 | 33.5 | 28.2 | 24.4 | |

| Proline | 21.8 | 33.1 | 30.9 | 35.5 | 39.3 | |

| Serine | 22.6 | 31.7 | 22.6 | 22.1 | 21.9 | |

| Tyrosine | 17.7 | 19.3 | 15.6 | 14.8 | 14.6 | |

| ∑NEAA5 | 331.5 | 384.5 | 282.8 | 282.4 | 283.8 | |

| Ingredient | Requirement | Experimental diet | ||||

| FM | SPC | Con | SPC25 | SPC50 | ||

| C14:0 | 59.3 | 34.8 | 31.9 | 26.2 | ||

| C16:0 | 241.9 | 205.1 | 202.9 | 187.1 | ||

| C18:0 | 49.1 | 197.7 | 222.6 | 247.6 | ||

| C20:0 | 15.3 | |||||

| C22:0 | 19.4 | |||||

| ∑SFA | 384.9 | 437.6 | 457.4 | 460.9 | ||

| C17:1n-7 | 48.6 | 46.5 | 42.9 | |||

| C18:1n-9 | 28.5 | 28.0 | 27.0 | |||

| C24:1n-9 | 15.2 | |||||

| ∑MUFA2 | 15.2 | 77.1 | 74.5 | 69.9 | ||

| C18:2n-6 | 118.6 | 178.3 | 210.3 | 260.4 | ||

| C18:3n-6 | 29.3 | 31.3 | 35.2 | |||

| C20:2n-6 | 37.9 | |||||

| C20:3n-6 | 18.1 | |||||

| C20:4n-6 | 44.2 | |||||

| C20:5n-3 | 120.6 | |||||

| C22:2n-6 | 0.9 | 68.4 | 65.0 | 49.7 | ||

| C22:6n-3 | 169.5 | 117.8 | 108.3 | 77.8 | ||

| ∑n-3 HUFA3 | 491.8 | 8.16–10.204 | 117.8 | 108.3 | 77.8 | |

| Unknown | 139.7 | 73.4 | 53.2 | 46.1 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).