1. Introduction

Iron deficiency anemia affects cardiovascular response and induces metabolic and hormonal disturbances both of which are essential for temperature regulation [

1,

2,

3]. Early studies in resting humans and animals with iron deficiency anemia have shown impaired thermoregulation and altered metabolism during cold air or water exposure [

4,

5,

6,

7]. For instance, individuals with anemia experienced greater body heat losses due to a reduced ability to increase metabolism, as indicated by lower rectal temperature and oxygen uptake responses [

5]. Additionally, due to enzymatic depletion of iron, oxidative metabolism is impaired, and catecholamine levels are elevated [

2,

8,

9,

10]. These disturbances, at rest, are reversed when iron deficiency anemia is treated, highlighting the importance of adequate iron levels for maintaining proper thermoregulation and overall metabolic function [

4].

However, there is a paucity of studies investigating the integrated responses of thermoregulatory and cardiovascular responses in anemic individuals at cold. Exercise and cold environment could independently tax cardiovascular responses [

11] and, to the best of our knowledge, there are no investigations of whether the disadvantageous cardiovascular system of anemic individuals, in terms of oxygen delivery, would be able to serve both the thermoregulatory and metabolic demands of exercise simultaneously. It has been documented that during exercise in the cold the cardiovascular strain is amplified causing altered sympathetic function [

12]. Cold exposure is characterized by a sympathetic nervous system excitation that causes cutaneous vasoconstriction [

13] and elevated muscle sympathetic nerve activity [

14] leading to increases in arterial blood pressure, and thus, heightening the risk of cardiovascular events more pronouncedly in individuals with underlying cardiovascular diseases [

13,

15,

16,

17,

18].

Iron deficiency anemia is most prevalent in well trained pre-menopausal women, athletes, military personnel and pregnant women [

19,

20,

21]. It also coexists in various diseases such as heart failure, hypertension, kidney failure and cancer [

22,

23,

24,

25]. Therefore, it is of great importance to examine the physiological and thermal behavioral responses of individuals with chronic iron deficiency during exercise in moderately cold environments as these conditions are common in work, sports and recreational activities.

This study aims to investigate how individuals with mild iron deficiency anemia regulate body temperature and respond to cardiovascular stress during exercise in moderate cold (11-12 °C) conditions. Understanding these responses is critical for improving the safety and performance of vulnerable populations under such environmental conditions.

We hypothesized that during exercise anemic participants compared to controls would demonstrate a slower rise in core temperature due to a compromised heat production which could not be counterbalanced by enhanced peripheral vasoconstriction and augmented blood pressure response.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Eighteen young adult participants, nine (5 females, 4 males) with chronic mild iron deficiency anemia (inclusion hematological criteria were: 10 < Hb < 12 g/dL, 34 < Hct < 37%, ferritin < 15 µg/L) [

26] and nine (5 females, 4 males) controls with normal [Hb], serum iron (Fe) and ferritin volunteered for the study (

Table 1). An a priori power analysis (G Power 3.1.9.7. software) indicated that a minimum of sixteen participants (8 per group) was required to achieve a statistical power greater than 0.85, effect size

ηp2 >0.06 (medium) and α value ≤0.05, in a mixed 3-way ANOVA design (group × condition × time). Both groups had no previous history of cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases and were free of musculoskeletal injuries and thyroid diseases. Before visiting the lab, the participants were instructed to avoid heavy meals (4h), intense exercise (24h) and not consume alcohol and caffeinated beverages (12h). All female participants had regular menstrual cycle and were not using contraception pills. In addition, to avoid the confounding effects of female hormones on core temperature and physiological responses, all female participants exercised during the follicular phase of menstrual cycle [

27], which was assessed with urine sticks. The experimental procedures had the approval of the local Ethical Committee (1157/11-12-2019). All possible risks and benefits of the procedures were thoroughly explained to the participants, and their written consent was obtained. The two groups were well matched for age, height, body mass, body surface area and %fat. However, they were different by design for fitness level using the prediction equation of differences in V̇O

2max with corresponding differences in hemoglobin concentration as reported by Calbet and colleagues [

28]. More specifically, initially, fitness and hematological parameters of the anemic participants were measured and thereafter they were matched with control participants based on [Hb]-corrected V̇O

2max values.

2.2. Study Design

Prior to the main experiments, the participants visited our lab on two occasions, including a baseline blood status assessment, a seven-site body fat calculation [

29] and a familiarization with experimental procedures and the equipment/instrumentation. Thereafter, on two different days, with at least 48-h interval, the participants performed VO

2max tests on cycle ergometer (Lode, Groningen, The Netherlands), one in cold (11 °C and RH: 40%) and one in neutral (22 °C and RH: 40%) environment. The load of incremental exercise was initially set at 20 W for all participants and then increased by 20 W every min for females and by 30 W for males until volitional exhaustion. The highest 20-s values were averaged to determine V̇O

2max.

During experimental protocols, 1 h before the experiment, participants arrived at the lab and ingested 5 mL/BM of water. They then emptied their bladder, and their body mass was measured (Bilance Salus, Italy) while wearing only shorts (males) or shorts and a fitted top (females). Afterwards, their capillary blood Hct% and [Hb] were determined. Then, they remained seated for 5 min while baseline rectal and skin temperatures and blood pressure were recorded, serving as idle values. If rectal temperature differed more than 0.2 °C from the value recorded in the first visit, the experiment was postponed for another day. The participants remain seated for another 20 min either in neutral or cold environment in a randomized and counterbalanced order. Then, they performed the prolonged cycling exercise protocol in the corresponding environmental condition (neutral: 22 °C, 40% RH and cold: 11 °C, 40% RH), (ANN: anemia + neutral, ANC: anemia + cold & CONN: control + neutral, CONC: control + cold): at an intensity 10% below the second ventilatory threshold (VT2) until either their rectal temperature (T

re) increased by 1 °C or until 1 h had passed, whichever occurred first. Participants were not allowed to drink water throughout the experiment (including resting period and exercise) and wore the same clothing across all conditions: shorts, socks, T-shirt and shoes. Each exercise session was separated by an interval of at least 48 h between measurements. Also, the hydration status was assessed in every visit using Hct% values and body mass [

30].

2.3. Measurements

Core body temperature was recorded with a probe (MSR 145, Henggart, Switzerland) at rectum, 10-12 cm past the anal sphincter, sampled and stored at 30-s intervals by MSR data logger (Modular Signal Recorder, MSR Electronics GmbH, Henggart, Switzerland). Skin temperature was measured at four sites (forearm, fingertip, calf, chest) using thermocouples (MSR 147WD, Henggart, Switzerland) attached to the skin with a single piece of adhesive tape, and a weighed mean skin temperature (T

skin) was calculated [

31,

32]. The forearm–fingertip temperature difference (T

f-f) was used as an index of skin vasomotor tone, which is reproducible during exercise [

33].

Minute mass flow of local sweat rate secreted in the forearm was measured continuously during the experiment at a frequency of 200 Hz by means of a ventilated capsule, positioned on a 5.72-cm

2 area of skin at the right forearm and ventilated at a rate of 1 L/min with room air. The temperature and humidity of air entering and exiting the capsule were measured with thermocouples (TSD 202A, BIOPAC, Systems Inc.) and capacitance hygrometers (Delta), respectively. Sweating rate (SwR) was estimated from the difference between the temperature and the humidity of inflowing and outflowing air. Temperature and humidity sensors were appropriately calibrated before their use. Also, thermal sensation was assessed with a scaled questionnaire (1, cold; 3, cool; 5, slightly cool; 7, neutral, 9; slightly warm, 11; warm, 13; hot) (ASHRAE, 1966, modified). Gas exchange and ventilatory variables (V̇O

2, V̇CO

2 RER, V̇E) were recorded continuously throughout experiments breath by breath via open-circuit spirometry (Ultima CPX, MedGraphics, USA). Before each test, the gas analyzers for O

2 and CO

2 and the pneumotachograph were calibrated with two different gas mixtures a) 12% O

2 and 5% CO

2 balanced in N

2 and b) 21% O

2 and 0.01% CO

2 balanced in N

2 and a 3-L syringe (Ultima CPX, MedGraphics, USA), respectively. Metabolic energy expenditure was calculated as follows:

where “RER” is respiratory exchange ratio (VCO

2/VO

2), “ec” is the caloric equivalent of a liter of oxygen when carbohydrates are oxidized (21.1 kJ) and “ef” is the caloric equivalent of a liter of oxygen when fat is oxidized (19.6 kJ).

Systolic blood pressure (SP) and diastolic blood pressure (DP) were continuously recorded beat by beat noninvasively via a photoplethysmograph with the cuff attached on the middle finger of the left hand (Finometer 2003, FMS, The Netherlands). Stroke volume (SV) was estimated via the Modelflow method [

34] , while mean arterial pressure (MAP), cardiac output (CO) and total peripheral resistance (TPR) were calculated by BeatScope software (version 1.a.). The method of photoplethysmography has been shown to have very high validity correlation (0.93-0.99) with invasive methods such as arterial line placement during dynamic exercise [

35]. To minimize measurement noise, the left hand was carefully and comfortably immobilized in a stable structure so as not to constrain maximal effort during exercise. The heart rate (HR) was monitored with a standard lead II electrocardiogram (ECG 100C, BIOPAC Inc., USA). The Hct% values were determined using Hct scale (Haematocrit Reader, Hawksley Inc., UK) after a 5-min centrifugation of 75μL capillary blood at 11,500 rpm (Micro Haematocrit Mk5 Centrifuge, Hawksley, UK) with a resolution of 1% units. The [Hb] values were determined by a portable photometer (Diaspect Tm) using 10 μL of capillary blood.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Normality of data was assessed using Shapiro-Wilk test. A Student’s paired two-tailed t-test was employed for comparing participants’ characteristics. Resting values of rectal and skin temperatures were analyzed using ANOVA for two factors (group x condition). The same analysis was also performed for rate of rectal temperature rise, heat production values and initiation of sweating. Three-way ANOVA was conducted to analyze cardiovascular and thermoregulatory responses with [Hb] as between-subject factor and two within-subject factors (condition and time). The cardiovascular and thermal responses presented in the figures were analyzed for the common 20-min period of exercise since there was time variation to achieve the targeted Tre of 38 °C. A Tuckey post hoc test was used to assess the significance of parametric analysis. For significant time related interactions, separate two-way ANOVA was conducted at each time point of interest. Moreover, partial eta squared as measures of effect size was used, where ηp2= 0.01 is considered small, 0.06 moderate, and >0.14 as large. A violation of normality was found for thermal sensation; thus, initially a Friedman test was conducted to discriminate overall group effects (anemia vs. control). Thereafter, a Wilcoxon Signed–Rank Test was used to detect differences between conditions within the same group and a Mann-Whitney test for independent groups at each time point. Data is presented as mean±SD. The significance level was set at p≤0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

The two groups differed by design in blood variables (p<0.001) and were matched for anthropometric characteristics (p>0.05) (

Table 1). [Hb] was by 21% lower in the anemic group (p<0.001) and V̇O

2max by 12.5%, but overall group difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.06). Also, there was no effect of cold exposure in V̇O

2max for both groups (ANN:40.6±4.7, ANC: 41.1±4.9 & CONN: 46.3±7.1, CONC: 46.7±6.6 mL·kg

-1·min

-1) (p>0.05). No group differences for MAP were detected before the thermal provocation for resting data (p=0.98), (ANN: 94±9; ANC: 96±7 vs. CONN: 94±6, CONC: 95±6). Also, there were no differences between groups for baseline values regarding T

sk and T

re in Neutral and Cold conditions, respectively.

3.2. Cardiovascular Responses

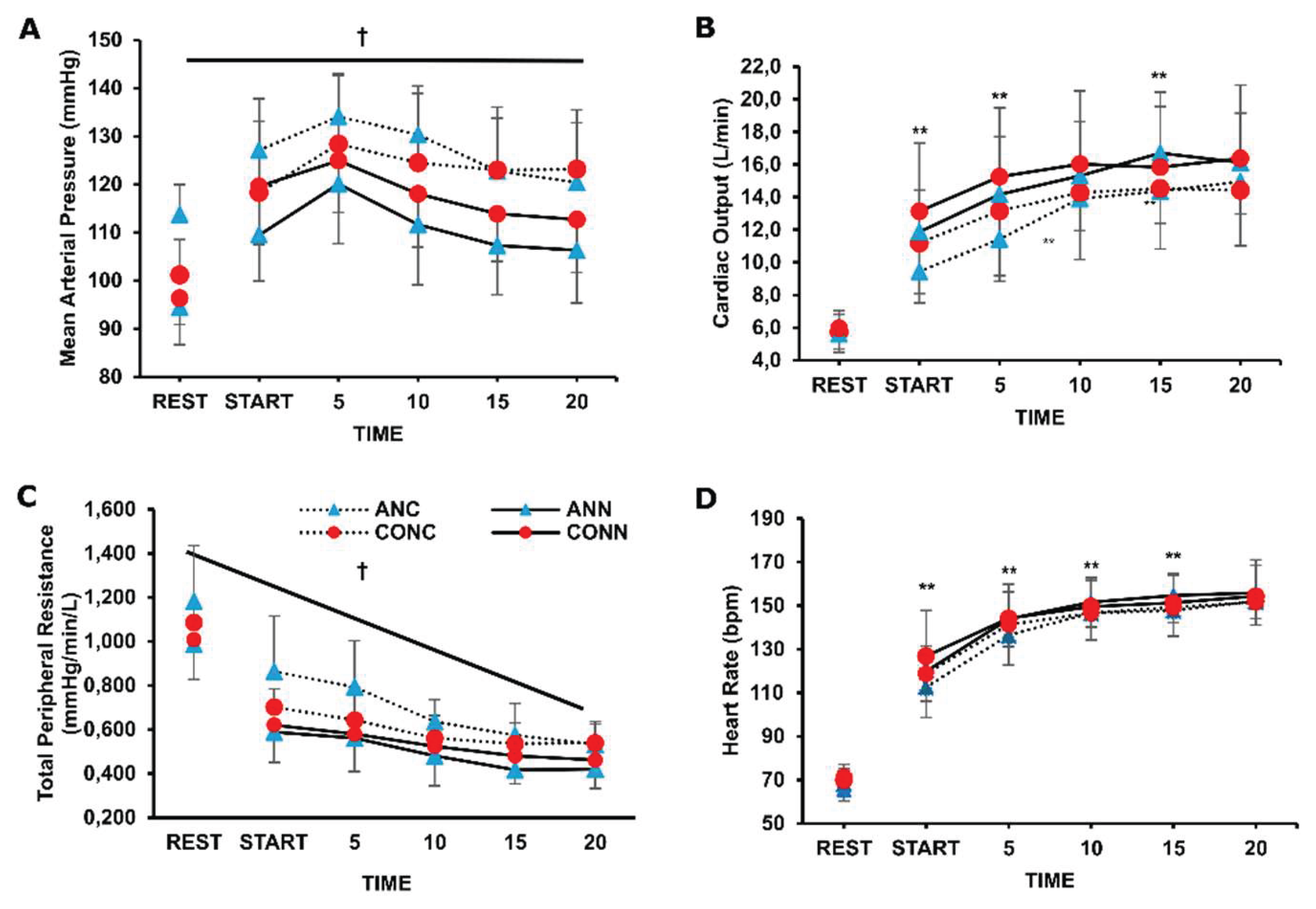

There was a significant group x environment interaction for MAP (p=0.031, η

p2=0.26) and for TPR (p=0.043, η

p2=0.23) and post-hoc analysis indicated that they were significantly higher in the cold condition compared to neutral, but only in the anemic group the values reached significance, both at rest and during exercise (p<0.001) (

Figure 1).

For CO responses an environment x time interaction was revealed (p=0.004, η

p2=0.19) and further analysis indicated that only in the anemic group the CO differed at specific time points between cold and neutral conditions during exercise (

Figure 1B). Overall stroke volume increased from rest to exercise (p=0.001, η

p2=0.19) and there was no difference in the cold (97±26 mL) compared to the neutral (103±26 mL) condition during exercise (p=0.10). Overall heart rate increased during exercise in both groups and conditions (p<0.001, η

p2=0.98), and it was lower from the onset until the 15

th min of exercise in ANC compared to ANN (p=0.01, η

p2=0.40). Diastolic blood pressure was higher in ANC (93±10 mmHg) compared to ANN (82±10 mmHg) (p=0.022, η

p2=0.75), while it was elevated in CONC compared to CONN only at the 15

th and 20

th min of exercise (p=0.005). Systolic blood pressure was elevated only in ANC (175±21 mmHg) compared to ANN (155±21) (p=0.0004, η

p2=0.37) with no difference between CONC (166±23 mmHg) and CONN (162±23 mmHg) (p=0.64).

3.3. Thermoregulatory Responses

The rate of rectal temperature rise was lower in ANC compared to CONC (p=0.047, η

p2=0.22) and ANN (p=0.003, η

p2=0.33) (

Table 2). Accordingly, exercise time to reach a specific temperature (+1 °C) was longer for ANC compared to ANN (p=0.001, η

p2=0.52) and CONC (p=0.021, η

p2=0.26) (

Table 2).

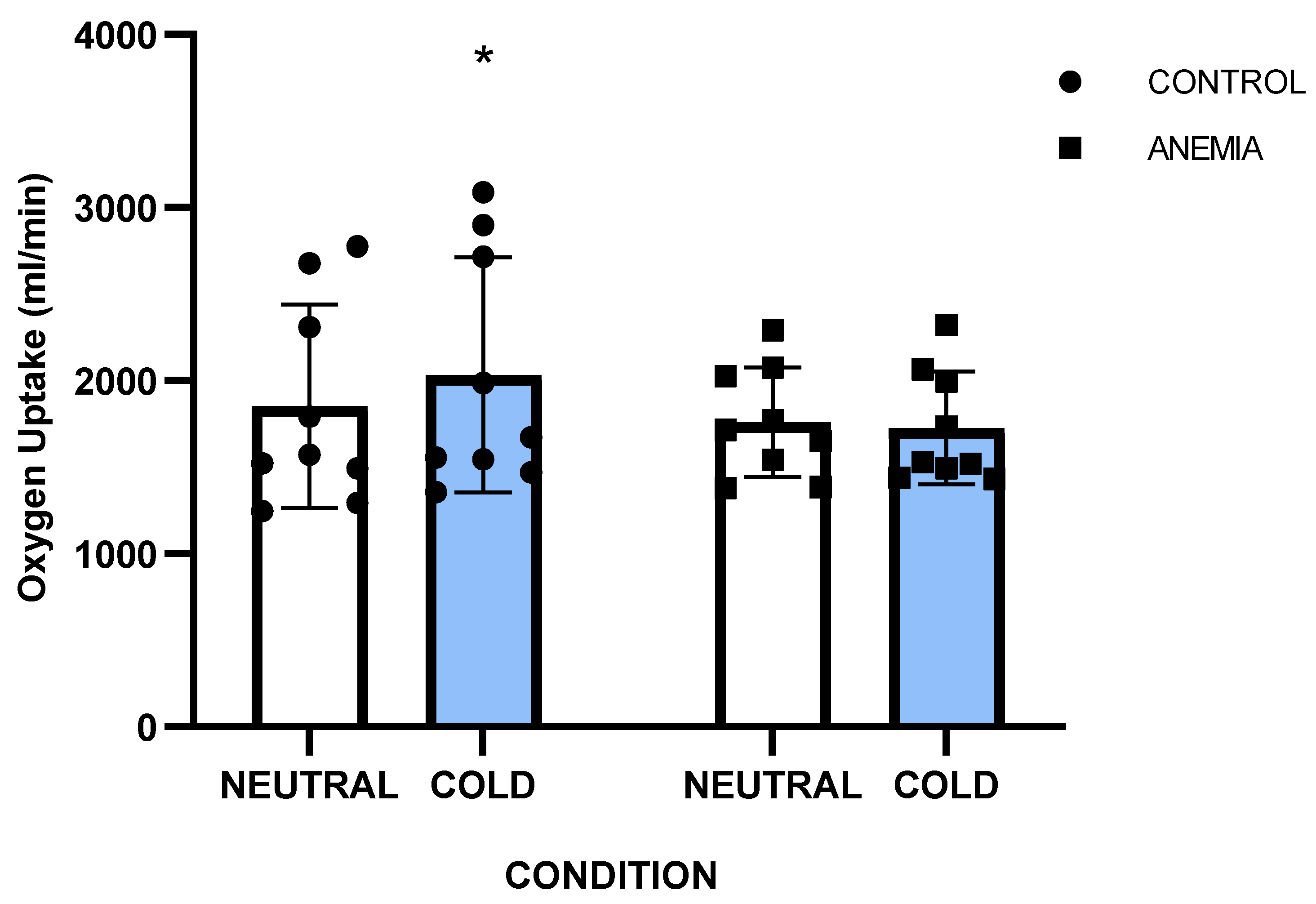

A significant group x condition interaction was noted for oxygen uptake (p=0.016, η

p2=0.31) and post hoc analysis revealed that VO

2 was higher only in the control group during exercise in the cold (CONC: 1852±626 mL/min) compared to thermoneutral (CONN: 2031±727 mL/min) (p=0.026) (

Figure 2), whereas in the anemic group the VO

2 remained unchanged in the two conditions (ANN: 1759±314 mL/min vs. ANC: 1725±321 mL/min) (p=0.92). Metabolic heat production (

Hprod) in absolute values during exercise (

Table 2) was higher in CONC (710±236 W) than in CONN (645±204 W) (p=0.035, η

p2=0.25), but similar between ANC (610±106 W) and ANN (606±107 W). Also,

Hprod was not different between ANN and CONN in relative values as well (

Table 2).

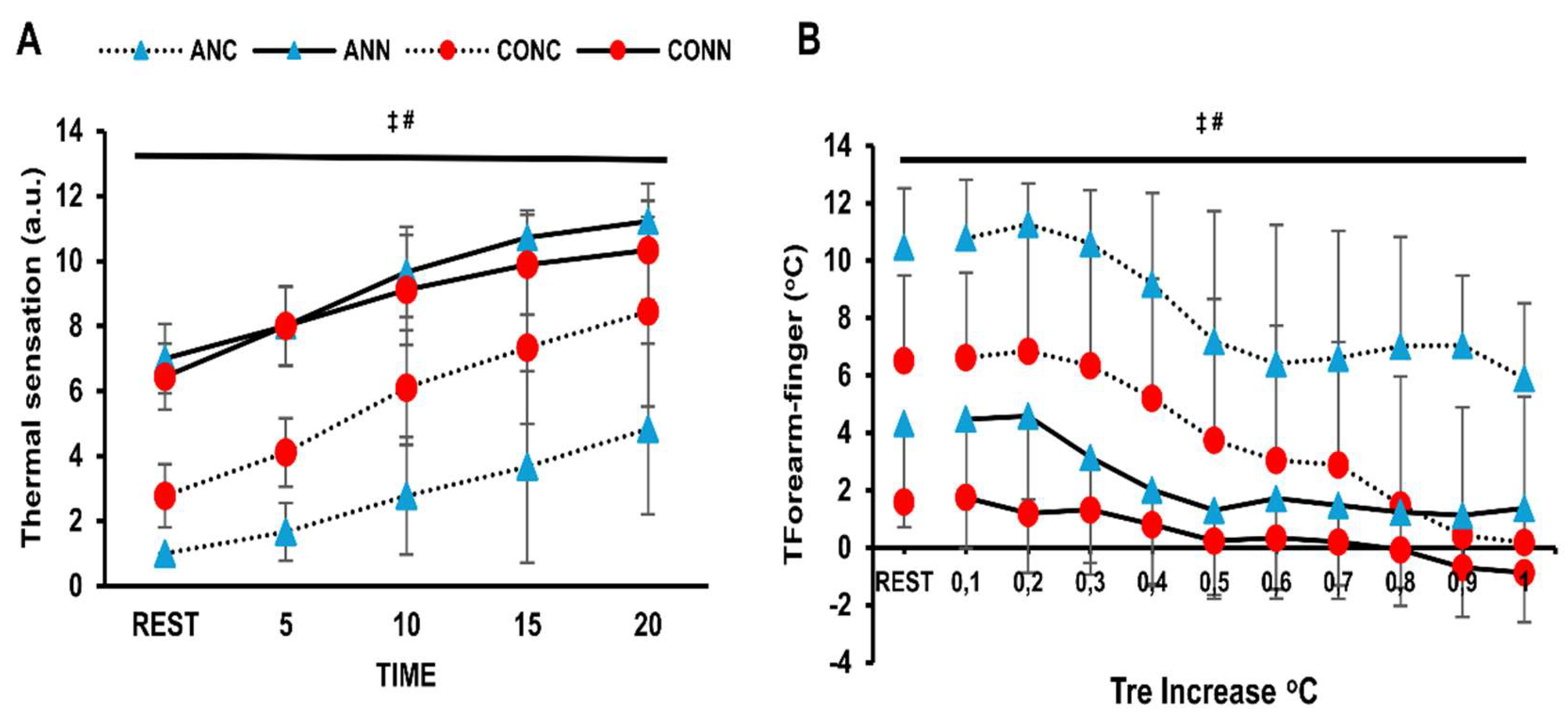

A group x condition interaction (p=0.010, η

p2=0.36) was found for T

skin accounted for by the lower T

sk values at rest and throughout exercise observed in ANC compared to CONC (p=0.028) and ANN (p=0.001) (

Figure 3A). Cold exposure delayed the onset of sweating in both groups (p=0.001). There was a strong tendency for difference between ANC (0.33±0.2) and CONC (0.21±0.1) (p=0.056). The sweat rate increased as time progressed (p=0.0001) and it was lower in cold environment irrespective of group (p=0.004, η

p2=0.40). Also, SwR in ANC was lower than CONC during exercise (p=0.024) (

Figure 3B).

There was a violation of normality for thermal sensation. Therefore, a Friedman test was conducted indicating that there is a condition effect for both the anemic and control groups (p=0.001). Thus, Nonparametric Wilcoxon was used as a post-hoc test and showed a difference between cold and neutral conditions for both groups (p=0.001). Lower thermal sensation values were noticed in ANC compared to CONC (p=0.01) according to Mann-Whitney test for independent groups. T

forearm-finger was lower in the anemic participants than in controls (p=0.004, η

p2=0.42) and higher in the cold than in the thermoneutral condition (p<0.001, η

p2=0.72) (

Figure 4B).

4. Discussion

Previous studies in animals and humans with iron deficient anemia have focused primarily on temperature regulation responses during cold exposure at rest [

5,

6,

7]. This is the first study that examined the interactive temperature, cardiovascular and thermal behavioral responses both at rest and during exercise in anemic individuals. The main findings of this study are that chronic mild iron deficiency anemia affects cardiovascular and thermoregulatory responses in individuals exposed to cold air conditions at rest and during exercise. Specifically, anemic individuals showed lower rate of rectal temperature rise and mean skin temperature, augmented peripheral vasoconstriction and exaggerated blood pressure response in the cold condition. Also, anemic individuals exhibited suppressed sweating rate responses. These findings suggest enhanced cardiovascular strain in anemic individuals, especially during exercise, probably inducing high cold vulnerability in this group of people.

4.1. Cardiovascular Responses

In young anemic individuals, elevated mean arterial pressure was recorded both at rest and during early exercise, more than in controls, in cold conditions. Even though anemia is generally characterized by increased vasodilatory capacity [

36,

37], this is the first study indicating a high blood pressure response in anemic individuals during cold exposure. This accentuated cardiovascular strain, likely due to increased sympathetic activation and peripheral vasoconstriction, could be of clinical importance given the frequent coexistence of anemia and cardiovascular disease, which may raise the risk of adverse events in cold environments. In the present study, the healthy participants exhibited elevated blood pressure response at rest (~5mmHg) and exercise (~10mmHg) in the cold compared to the neutral condition but this difference did not reach statistical significance likely due to a great individual variability [

16,

38]. The lower skin temperature observed in our anemic individuals in the cold is associated with increased total peripheral resistance, which is attributable to changes in cutaneous vasculature based on T

finger-forearm, although current data in young adults remain inconclusive as to whether sympathetic response also involves muscle vasculature [

14,

39,

40]. Moreover, the hypertensive response may be driven by higher catecholamine levels in anemia, as supported by earlier animal and human research [

4,

8,

9]. In our study, the cardiac output of anemic individuals was lower in the cold compared to the neutral condition due to lower heart rate response which is common during cold exposure, especially under extreme cold conditions where body temperature is reduced [

11]. Also, intriguingly, the reduced heart rate of anemic individuals during exercise in the cold could be indicative of an attempt to attenuate cardiac output and, therefore, to blunt the exaggerated arterial blood pressure response, thus altering the operating point of HR baroreflex [

41]. In our study, stroke volume remained relatively stable in both groups, in alignment with previous research showing that stroke volume is typically preserved or even elevated [

42,

43,

44,

45] and, thus, the central venous pressure (preload) was not different among conditions and groups. As arises from above, the hypertensive response displayed by the anemic individuals is mainly attributed to enhanced peripheral resistance. However, further research is warranted in anemic individuals regarding the purpose served and the precise autonomic responses recruited in cardiovascular control under cold stress.

4.2. Temperature Regulation Responses

Cutaneous vasoconstriction serves as a principal defending mechanism against body temperature reduction during cold exposure [

11]. In our study, the anemic group showed higher vasoconstrictor activity in cold conditions compared to controls, as assessed by the finger-forearm skin temperature gradient, that resulted in lower mean skin temperature. Despite this, anemic individuals displayed a lower rate of rectal temperature rise in cold conditions compared to controls suggesting impaired heat generating mechanisms.

V̇O

2 response has major role in temperature regulation in the cold [

11]. In our study, the anemic participants had comparable metabolic heat production to controls in the neutral condition, but they could not increase their V̇O

2 responses in the cold as the healthy participants did and this is evident in their higher metabolic heat production both in absolute (W) and relative (W·kg

-1 & W·m

-2) values. Our findings align with earlier findings that iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia affected the metabolic responses during cold exposure in resting humans and animals. Particularly, Beard and colleagues (1990) in their study, after controlling for body fat and menstrual cycle, reported that anemic women had lower V̇O

2 values in the cold and their core temperature declined faster due to insufficient non-shivering thermogenesis mechanisms. The authors suggested that these responses are linked to lower thyroid hormones levels, since iron deficiency affects the conversion of T4 to more drastic T3, leading to diminished circulating levels of thyroxine and triiodo- thyronine in rats and humans [

5]. This conversion to the more drastic T3 requires iron [

1] and is crucial for stimulating brown adipose tissue thermogenesis, essential for energy homeostasis in cold conditions [

46,

47].

Thermal sensation plays a critical role in initiating behavioral thermoregulation, but there is a lack of information regarding individuals with chronic iron-deficiency anemia. In our study, cold exposure reduced subjective thermal sensation in both groups, with anemic participants reporting even lower values. During exercise in the cold, their thermal sensation mirrored lower mean skin temperature, slower rectal temperature rise, and greater vasoconstriction, as indicated by finger-forearm gradient. These findings agree with previous studies showing that thermal sensation is influenced by skin and rectal temperatures [

48]. Anemic individuals’ higher cold sensitivity may reflect a compensatory behavioral mechanism for impaired heat production. On the other hand, it could be a greater intolerance which possibly arises from their diminished inability to maintain core temperature. Crucially, from a clinical perspective, cold intolerance is connected to earlier onset of ischemia or angina during exercise in coronary artery disease patients [

49,

50]. Further research should elucidate the thermal perception of anemic humans and the interactive effect of additional thermal factors, such as ageing, hypoxia and sleep deprivation on thermal sensation.

To our knowledge, the present study is the first one to examine the temperature regulation responses of iron deficient anemic humans during exercise in the cold with previous research focusing only on resting conditions [

7,

9,

10]. In the present study the anemic participants also displayed lower local sweat rate in the cold in the same manner as T

sk. In fact, skin temperature modulates sweat rate responses [

51] especially during cold exposure where a drop in T

sk reduces the sweat production without any observed change in body temperature [

52].

The findings of this study on how iron-deficiency anemia alters cardiovascular and thermal responses during cold exposure could be applied in a wide range of areas, such as clinical practice, exercise performance, workers and military personnel. From a clinical perspective, these findings can help identify individuals at higher risk for adverse outcomes in cold environments, particularly in populations with complex cardiovascular conditions.

4.3. Methodological Considerations

This study is not without limitations. During cold exposure, the sympathetic nervous system is stimulated and, therefore, the autonomic cardiovascular responses play a pivotal role in maintaining the homeostasis of cardiovascular system both at rest and during exercise. Given that the anemic individuals showed a reduced heart rate with a concomitant increased mean arterial pressure it is suggested that the arterial baroreflex may be altered in this group; however, the study design did not allow for a thorough investigation of the role of autonomic regulation, especially the arterial baroreflex function. Therefore, more in-depth investigation of autonomic regulation is required in anemic populations. Moreover, the study was limited by the absence of skin blood flow measurements, since sympathetic noradrenergic vasoconstrictor nerves induce a rapid decrease in skin blood flow, in cold conditions [

13]. However, we attempted to address this limitation by measuring forearm-finger skin temperature gradient which is considered as a valid qualitative index of cutaneous vasomotor tone during steady-state exercise [

33]. Also, ecological validity was compromised, as the participants’ light clothing did not accurately represent typical real-world settings; besides, a combination of cold temperatures with other environmental stressors (i.e. altitude, wet environment) could pose an additional challenge to metabolic responses [

53].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study highlights the significant impact of chronic mild iron-deficiency anemia on cardiovascular and thermoregulatory responses during cold exposure, particularly during exercise. Anemic individuals displayed a slower rise in rectal temperature. They also exhibited a lower skin temperature, as well as elevated vasoconstriction and total peripheral resistance, as a compensatory mechanism. The latter responses resulted in exaggerated blood pressure, indicating exaggerated cardiovascular strain compared to controls. Given the prevalence of anemia in individuals with cardiovascular diseases and in a significant portion of athletic population, more research is needed to adequately address the autonomic cardiovascular responses under various adverse environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.M., N.G. and M.K.; methodology, P.M., A.T., N.G. and M.K.; formal analysis, P.M. and M.K.; investigation, P.M., S.N. and P.L.; data curation, P.M.; writing—original draft preparation, P.M. and M.K.; writing—review and editing, P.M., S.N., P.L., A.T., N.G. and M.K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by Research Ethics and Bioethics Committee of the School of Physical Education and Sport Science, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece (1157/11-12-2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the participants for their remarkable commitment and engagement throughout the experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Tsk

|

Mean skin temperature |

| Tre

|

Rectal temperature |

| VO2

|

Oxygen uptake |

| TPR |

Total peripheral resistance |

| MAP |

Mean arterial pressure |

| CO |

Cardiac output |

| HR |

Heart rate |

| SwR |

Sweat rate |

|

Hprod |

Heat production |

References

- Brigham, D.; Beard, J. Iron and thermoregulation: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 1996, 36, 747–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, P.H.; Volpe, S.L. Iron, thermoregulation, and metabolic rate. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 1999, 39, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, J.L. Iron biology in immune function, muscle metabolism and neuronal functioning. J Nutr discussion 580S. 2001, 131, 568S–579S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, J.L.; Tobin, B.W.; Smith, S.M. Effects of iron repletion and correction of anemia on norepinephrine turnover and thyroid metabolism in iron deficiency. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1990, 193, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, J.L.; Borel, M.J.; Derr, J. Impaired thermoregulation and thyroid function in iron-deficiency anemia. Am J Clin Nutr 1990, 52, 813–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman, E.; Gale, C.; Green, W.; Johnson, D.G.; Mackler, B.; Finch, C. Hypothermia in iron deficiency due to altered triiodothyronine metabolism. Am J Physiol 1980, 239, R377–R381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukaski, H.C.; Hall, C.B.; Nielsen, F.H. Thermogenesis and thermoregulatory function of iron-deficient women without anemia. Aviat Space Environ Med 1990, 61, 913–920. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Voorhess, M.L.; Stuart, M.J.; Stockman, J.A.; Oski, F.A. Iron deficiency anemia and increased urinary norepinephrine excretion. J Pediatr 1975, 86, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dillmann, E.; Johnson, D.G.; Martin, J.; Mackler, B.; Finch, C. Catecholamine elevation in iron deficiency. Am J Physiol 1979, 237, R297–R300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Torres, C.; Cubeddu, L.; Dillmann, E.; Brengelmann, G.L.; Leets, I.; Layrisse, M.; Johnson, D.G.; Finch, C. Effect of exposure to low temperature on normal and iron-deficient subjects. Am J Physiol 1984, 246, R380–R383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellani, J.W.; Tipton, M.J. Cold Stress Effects on Exposure Tolerance and Exercise Performance. Compr Physiol 2015, 6, 443–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikaheimo, T.M. Cardiovascular diseases, cold exposure and exercise. Temperature (Austin) 2018, 5, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alba, B.K.; Castellani, J.W.; Charkoudian, N. Cold-induced cutaneous vasoconstriction in humans: Function, dysfunction and the distinctly counterproductive. Exp Physiol 2019, 104, 1202–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugele, H.; Marume, K.; Amin, S.B.; Possnig, C.; Kuhn, L.C.; Riehl, L.; Pieper, R.; Schabbehard, E.L.; Oliver, S.J.; Gagnon, D.; et al. Control of blood pressure in the cold: differentiation of skin and skeletal muscle vascular resistance. Exp Physiol 2023, 108, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparrini, A.; Guo, Y.; Hashizume, M.; Lavigne, E.; Zanobetti, A.; Schwartz, J.; Tobias, A.; Tong, S.; Rocklov, J.; Forsberg, B.; et al. Mortality risk attributable to high and low ambient temperature: a multicountry observational study. Lancet 2015, 386, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaney, J.L.; Kenney, W.L.; Alexander, L.M. Sympathetic function during whole body cooling is altered in hypertensive adults. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2017, 123, 1617–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fares, A. Winter Hypertension: Potential mechanisms. Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 2013, 7, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yavar, Z.; Sun, Q. Cardiovascular response to thermoregulatory challenges. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2015, 309, H1793–H1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClung, J.P.; Karl, J.P.; Cable, S.J.; Williams, K.W.; Young, A.J.; Lieberman, H.R. Longitudinal decrements in iron status during military training in female soldiers. Br J Nutr 2009, 102, 605–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parks, R.B.; Hetzel, S.J.; Brooks, M.A. Iron Deficiency and Anemia among Collegiate Athletes: A Retrospective Chart Review. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2017, 49, 1711–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasricha, S.R.; Moir-Meyer, G. Measuring the global burden of anaemia. Lancet Haematol 2023, 10, e696–e697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felker, G.M.; Stough, W.G.; Shaw, L.K.; O'Connor, C.M. Anaemia and coronary artery disease severity in patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2006, 8, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felker, G.M.; Shaw, L.K.; Stough, W.G.; O'Connor, C.M. Anemia in patients with heart failure and preserved systolic function. Am Heart J 2006, 151, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caro, J.J.; Salas, M.; Ward, A.; Goss, G. Anemia as an independent prognostic factor for survival in patients with cancer: a systemic, quantitative review. Cancer 2001, 91, 2214–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauffer, M.E.; Fan, T. Prevalence of anemia in chronic kidney disease in the United States. PLoS One 2014, 9, e84943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskolou, M.; Komboura, S.; Zacharakis, E.D.; Georgopoulou, O.; Keramidas, M.; Geladas, N. Physiological Responses of Anemic Women to Exercise under Hypoxic Conditions. Physiologia 2023, 3, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, F.C.; Waner, J.I.; Vieira, E.F.; Taylor, S.R.; Driver, H.S.; Mitchell, D. Sleep and 24 hour body temperatures: a comparison in young men, naturally cycling women and women taking hormonal contraceptives. J Physiol 2001, 530, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calbet, J.A.; Lundby, C.; Koskolou, M.; Boushel, R. Importance of hemoglobin concentration to exercise: acute manipulations. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2006, 151, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A.S.; Pollock, M.L. Practical Assessment of Body Composition. Phys Sportsmed 1985, 13, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavouras, S.A. Assessing hydration status. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2002, 5, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, A.C. A New Technic for the Measurement of Average Skin Temperature over Surfaces of the Body and the Changes of Skin Temperature During Exercise: Six Figures. The Journal of Nutrition 1934, 7, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D.; Wyndham, C.H. Comparison of weighting formulas for calculating mean skin temperature. J Appl Physiol 1969, 26, 616–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keramidas, M.E.; Geladas, N.D.; Mekjavic, I.B.; Kounalakis, S.N. Forearm-finger skin temperature gradient as an index of cutaneous perfusion during steady-state exercise. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 2013, 33, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogert, L.W.; van Lieshout, J.J. Non-invasive pulsatile arterial pressure and stroke volume changes from the human finger. Exp Physiol 2005, 90, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, K.M.; Fadel, P.J.; Smith, S.A.; Norton, K.H.; Querry, R.G.; Olivencia-Yurvati, A.; Raven, P.B. Increases in intramuscular pressure raise arterial blood pressure during dynamic exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2001, 91, 2351–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sproule, B.J.; Mitchell, J.H.; Miller, W.F. Cardiopulmonary physiological responses to heavy exercise in patients with anemia. J Clin Invest 1960, 39, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskolou, M.D.; Roach, R.C.; Calbet, J.A.; Radegran, G.; Saltin, B. Cardiovascular responses to dynamic exercise with acute anemia in humans. Am J Physiol 1997, 273, H1787–H1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greaney, J.L.; Stanhewicz, A.E.; Kenney, W.L.; Alexander, L.M. Muscle sympathetic nerve activity during cold stress and isometric exercise in healthy older adults. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2014, 117, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagius, J.; Kay, R. Low ambient temperature increases baroreflex-governed sympathetic outflow to muscle vessels in humans. Acta Physiol Scand 1991, 142, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Durand, S.; Crandall, C.G. Baroreflex control of muscle sympathetic nerve activity during skin surface cooling. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2007, 103, 1284–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogoh, S.; Fisher, J.P.; Dawson, E.A.; White, M.J.; Secher, N.H.; Raven, P.B. Autonomic nervous system influence on arterial baroreflex control of heart rate during exercise in humans. J Physiol 2005, 566, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArdle, W.D.; Magel, J.R.; Lesmes, G.R.; Pechar, G.S. Metabolic and cardiovascular adjustment to work in air and water at 18, 25, and 33 degrees C. J Appl Physiol 1976, 40, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, P.B.; Niki, I.; Dahms, T.E.; Horvath, S.M. Compensatory cardiovascular responses during an environmental cold stress, 5 degrees C. J Appl Physiol 1970, 29, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Alonso, J.; Mora-Rodriguez, R.; Coyle, E.F. Stroke volume during exercise: interaction of environment and hydration. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2000, 278, H321–H330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, T.E.; Crandall, C.G. Effect of thermal stress on cardiac function. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 2011, 39, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianco, A.C.; McAninch, E.A. The role of thyroid hormone and brown adipose tissue in energy homoeostasis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2013, 1, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullur, R.; Liu, Y.Y.; Brent, G.A. Thyroid hormone regulation of metabolism. Physiol Rev 2014, 94, 355–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, S.M.; Raja, S.N.; Bulcao, C.F.; Goldstein, D.S. Relative contribution of core and cutaneous temperatures to thermal comfort and autonomic responses in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1999, 86, 1588–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchant, B.; Donaldson, G.; Mridha, K.; Scarborough, M.; Timmis, A.D. Mechanisms of cold intolerance in patients with angina. J Am Coll Cardiol 1994, 23, 630–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juneau, M.; Johnstone, M.; Dempsey, E.; Waters, D.D. Exercise-induced myocardial ischemia in a cold environment. Effect of antianginal medications. Circulation 1989, 79, 1015–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K. The physiology, pharmacology, and biochemistry of the eccrine sweat gland. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 1977, 79, 51–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibasaki, M.; Crandall, C.G. Mechanisms and controllers of eccrine sweating in humans. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2010, 2, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schafer, E.A.; Chapman, C.L.; Castellani, J.W.; Looney, D.P. Energy expenditure during physical work in cold environments: physiology and performance considerations for military service members. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2024, 137, 995–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).