1. Introduction

In recent years, increasing attention has been directed toward the human immune system and strategies to enhance its function. A growing body of evidence indicates that physical inactivity, tobacco use, excessive alcohol consumption, diets high in ultra-processed foods, excessive intake of sugar and salt, insufficient sleep, and chronic psychological stress are associated with impaired immune function [

1]. In contrast, regular physical activity, abstinence from tobacco and excessive alcohol, consumption of minimally processed, nutritionally balanced diets, adequate sleep, and effective stress management have been linked to improved immune function and greater resilience to illness [

2].

In addition to the latter measures, whole-body cryotherapy (WBC), a short-term therapeutic application of extreme cold of about minus 90 degrees, seems to show a positive influence on the immune system, physical pain, body composition and other human regulatory systems. In detail, whole-body cryotherapy, in which test subjects stay in a cold chamber by performing slow body movements on the extremities and head (ears and nose, mouth), was developed about 40 years ago in Japan and shows far-reaching effects on various regulatory systems of the human body in a short exposure time. Studies show that WBC can lead to a reduction in inflammatory mediators and muscle enzymes in the serum of athletes [

3]. Furthermore, WBC has demonstrated promising effects across a range of physiological and psychological domains. Emerging evidence suggests beneficial impacts on mental health, alleviation of pain associated with chronic conditions such as fibromyalgia and osteoarthritis, enhanced post-exercise recovery, improved sleep quality, mood elevation, and reductions in depressive symptoms. Additional potential benefits include support for weight management, adjunctive effects in autoimmune and neurological disorders, and possible enhancement of cognitive function and brain health [

4,

5,

6]

In line with these findings, this study further examines the influence of WBC on the various parts of the body system. In detail, this study aims to investigate how well WBC is suitable as a prevention method for strengthening the human immune system. In particular, the signaling pathways (gamma interferon), lymphocyte subsets (CD4/CD8 ratio) and defense mechanisms against viruses (ITT test) are to be determined by blood tests. Another focus of this study is the investigation of the change in body composition in the direction of age-specific norm values in bioelectrical impedance analysis measurement. The body's white fat content should be reduced, while the body's beige/brown fat content should be increased. The phase angle could augment and the amount of the lean mass of the body could change, which could be helpful in preventing chronic disease. Additionally, it will be investigated whether vagus stimulation is associated with a change in the subjective perception of stress, which can be objectified by the Trier Inventory for Chronic Stress (TICS) test procedure in a before/after comparison. A potential change in myofascial stiffness induced by cryo therapy has not yet been investigated. A semi-electronic myofascial stiffness measurement system can be used to investigate whether WBC leads to any change in this parameter. In addition, joint flexibility is recorded by the finger/floor distance test and mechanical pain sensitivity is examined via algometry.

Plasma sACE2 is a risk factor for severe COVID-19 identified by studies. This study is intended to investigate the effects of WBC on the plasma concentration of sACE2 in a before-and-after comparison. If this is reduced by the WBC, the WBC would possibly be suitable as a preventive measure against a severe course of COVID-19. The connections between the immune system, autonomic nervous system and myofascial tonicity during and after WBC have not yet been investigated. This pilot study aims to generate preliminary data and establish a foundation to guide the design of larger clinical trials.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a prospective monocentric observational study including 20 adult participants. Participants underwent 18 sessions of cryotherapy over 9 weeks (–90°C, 3–6 minutes each), followed by a 9-week post-intervention phase. Assessments were conducted at three time points: measurement 1 (baseline), measurement 2 (post-intervention), and measurement 3 (follow-up).

The study was registered in the German Register for Clinical Trials (trial no. DRKS 00031033) after approval by the ethical committee of the Bayerische Landesärztekammer (

www.ethikkommission.blaek.de; approval number 22118).

Since the present study is an exploratory monocentric study with pilot character, no formal sample size planning was carried out. The number of cases of n=20 was determined on the basis of the donations received for the study and the limited capacities of a therapeutic practice for reasons of feasibility. This number of cases was seen as sufficient to describe the (continuous) target variables collected in the study in such a way that initial insights into the mechanisms of action of the intervention can be provided on the basis of these results and sample size calculations can be carried out for future confirmatory (multicenter) studies.

The participants were recruited in the corresponding author’s practice Murnau, in a newspaper article in a local newspaper, a local journal and a video on a public website. In addition, the information was transmitted to the Murnau health department as well as general practitioners and other health professionals in the Garmisch-Partenkirchen district.

The inclusion criteria were male/female/diverse from 40-75 years. The exclusion criteria for WBC in this study comprised: (were to be clarified by preclinical medical diagnosis) pregnancy, severe hypertension (blood pressure > 180/100), acute or recent myocardial infarction, unstable angina, arrhythmia, symptomatic cardiovascular disease, pacemaker, peripheral arterial occlusive disease, venous thrombosis, acute or recent cerebrovascular accident, uncontrolled seizures, Raynaud's syndrome, fever, tumor disease, symptomatic lung diseases, blood clotting disorders, severe anemia, infections, cold allergies, cold agglutinin disease and acute kidney and urinary tract diseases, as well as epileptic seizures, further increased intraocular pressure, such as glaucoma, for these patients there is no exclusion of liability, even e.g. in the case of an unexplained increase in intraocular pressure.

Furthermore, consumption of more than 4 cups of coffee per day, more than 2 alcoholic beverages per day, a strong dietary change and extreme sports, as well as other cold applications such as ice bathing as well as beforehand cryotherapy experience were used as additional exclusion criteria.

Body composition was measured via bioelectrical impedance analysis. Immune parameters included full blood counts, CD4/CD8 subtyping, and cytokine profiling under stimulated conditions as well as a measurement of sACE2 levels. Stress perception was measured using the Trier Inventory for Chronic Stress (TICS). Peripheral vascular reactivity was assessed via blood volume pulse amplitude (BVP).

Laboratory analysis was performed by Human ACE2 ELISA Kit by Invitrogen. The serum samples from the test subjects, which had been frozen at -20°C, were thawed at room temperature and diluted 1, 2 with assay diluent from the test kit. This dilution level was chosen because preliminary tests showed that the dilution of 1, 8 specified by the test kit resulted in signals that were too low. Except for the changed dilutions, the ELISA was performed according to the test instructions, measured on the Tecan Reader Infinite F50 Plus, and evaluated with the Tecan Magellan software.

As it was found out in the course of the study that one participant had already had extensive cryotherapy exposure, she was asked to leave the study

Statistical analysis: patient cohort and values of the clinical parameter were described by appropriate measures of the empirical distributions depending on the scale: means and standard deviations, median, interquartile range and total range for continuous parameters, absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables. Repeated measurement analysis of variance was performed to analyze the time course of the clinical parameters and were illustrated by boxplots. Due to exploratory character of this study, p-values were not adjusted for multiple testing, and no imputation of missing values was performed. All analyses were performed in R version >4.2.0.

3. Results

One participant experienced significant physical and mental strain over the course of the study and became severely ill toward the end. This adverse event was deemed unrelated to the cryotherapy intervention. Consequently, the participant’s data was excluded from the final analysis.

3.1. Description of the Study Cohort and Received Cryotherapy

The description of the study cohort and received cryotherapy can be found in

Table 1. The cohort consisted of 19 patients with an average age of 52.9 ± 9.8 and 4 (21%) male participants. All participants received 18 sessions of cryotherapy with and average duration of 4.5 ± 0.76 min every 3.5 ± 0.4 days, indicating a consistent application of cryotherapy overall participants.

3.2. Bioimpedance Analysis

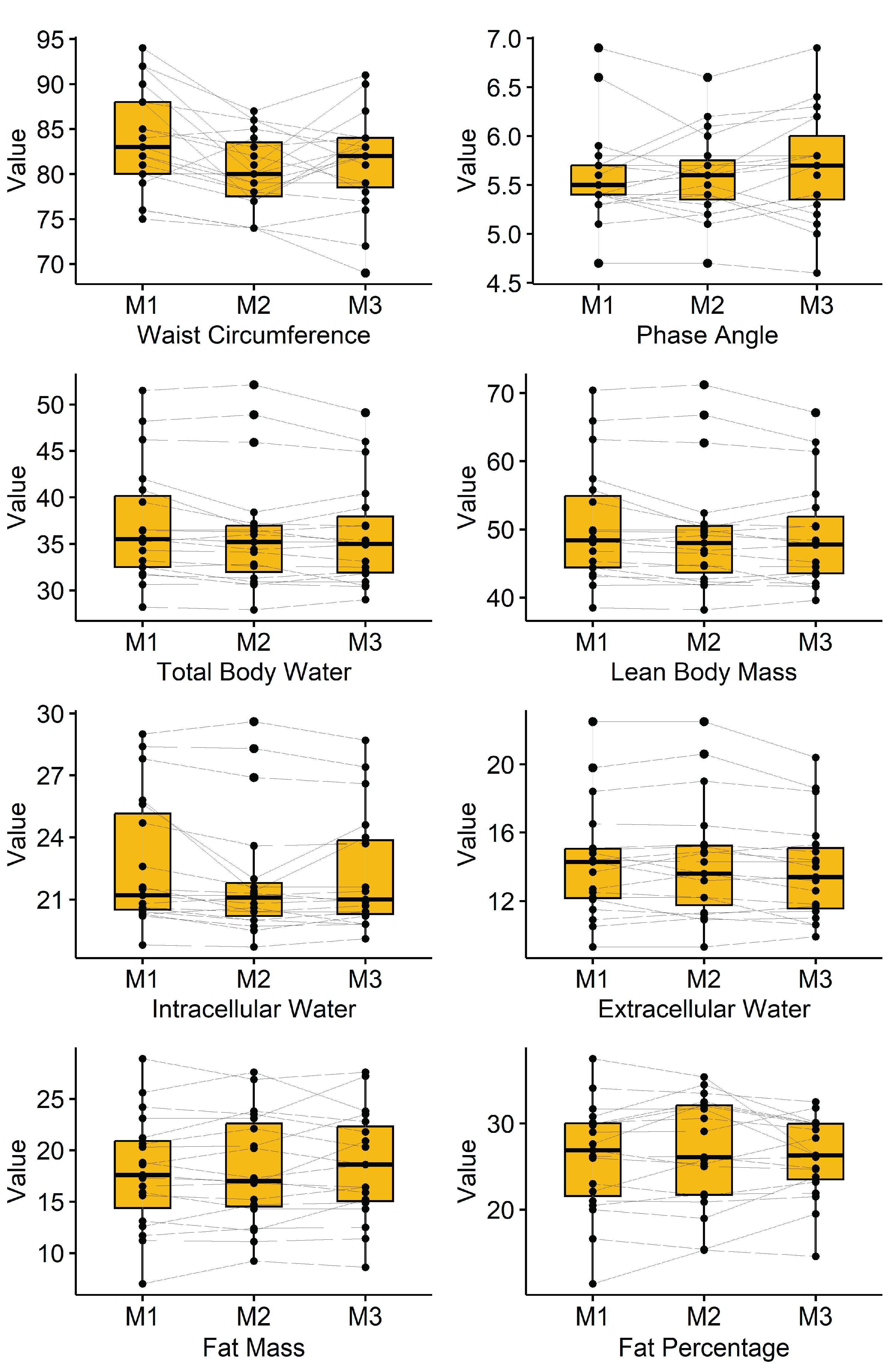

Results of the bioimpedance analysis can be found in

Table 2 and are illustrated in

Figure 1. Waist circumference significantly dropped from 83.8 ± 5.7cm to 80.2 ± 4.2cm and ended in 81.3 ± 5.5cm (p=0.001). Furthermore, total body water, lean body mass, as well as intercellular and extracellular water showed a significant decrease.

3.3. Immuno-Blood Parameter

Table 3 shows the time course of the blood parameters that refer to the immune system. Effects on Lymphocytes, Monocytes and Granulocytes can be found, especially directly after cryotherapy (Measurement 2), however, the effects dissolved to measurement 3. Furthermore, influences of cryotherapy on the virus pool can be seen: IL2 and INF-γ monotony decreasing and increasing, respectively, IL10 shows a high effect at measurement 2. In general, effects are examined particularly from measurement 1 to measurement 2 with diminishing effects afterwards.

3.4. Further Blood Parameters

The influence of cryotherapy on the further blood parameters BKS, ACE2 and BVP (mean and SD) is shown in

Table 4. No effects can be found for BKS. A statistically significant decrease can be found for ACE2 which can surprisingly be found especially in the follow-up (between measurement 2, 0.5±0.7 and measurement 3, 0.3±0.4, p=0.029). Trends (p-values <0.1) can be found for BVP mean and BVP SD with a notable decrease between measurement 1 and measurement 2.

3.4. Subjective Perception of Stress

Subjective perception of stress was measured by the Trier Inventory for Chronic Stress (TICS). The course of time for the participant’s reported subjective perception of stress can be found in

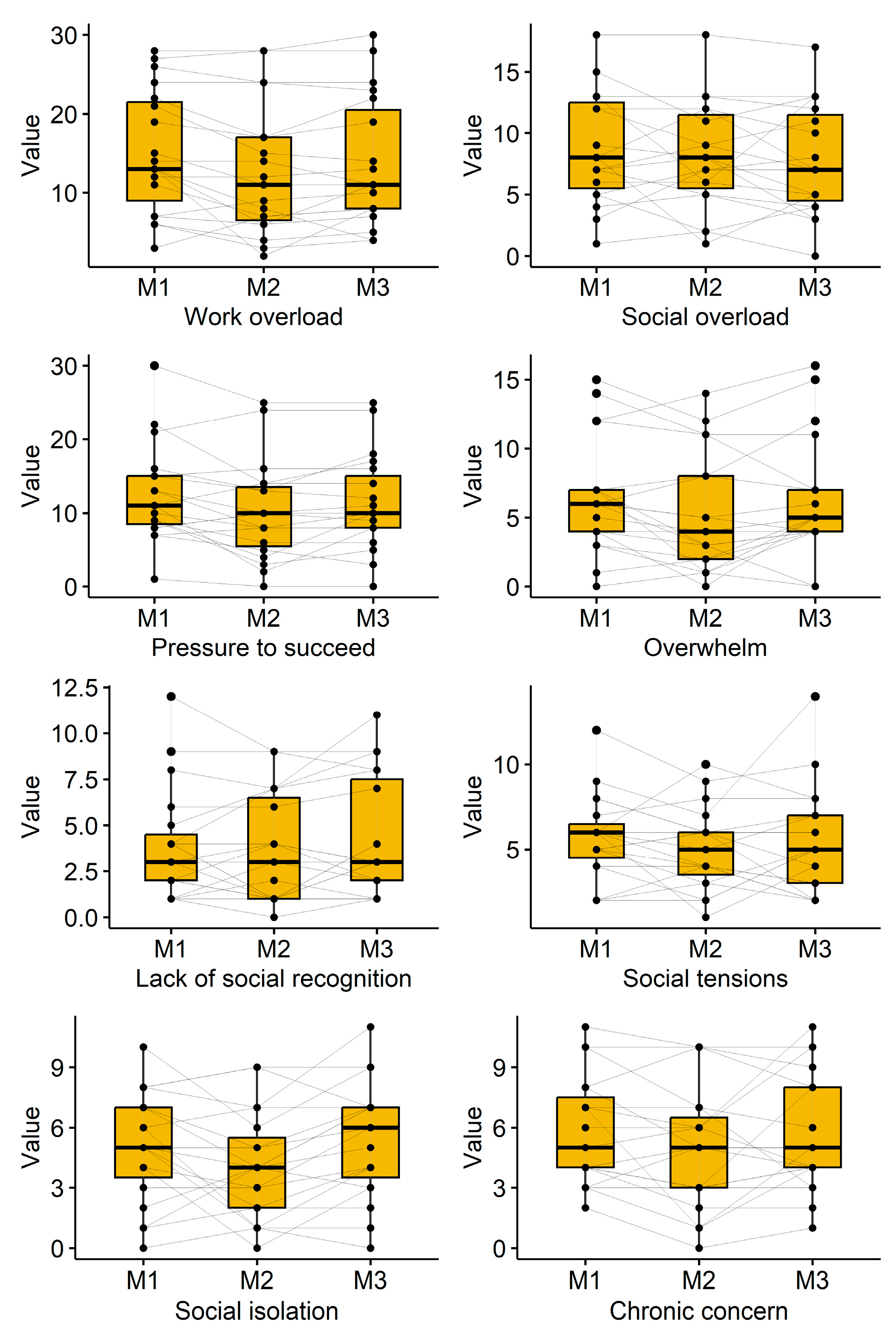

Table 5 and depicted in

Figure 2. Statistically significant effects can be found for the scales “Work overload” (p=0.009), “Pressure to succeed” (p=0.018) and “Social isolation” (p=0.049). A decreased effect (p=0.081) can be found for the scale “Overwhelm” directly after cryotherapy (6.4±4.1 to 5.2±4.3) but it vanished afterwards (6.2±4.4). The further TICS showed decreased values directly after cryotherapy that often neutralized afterwards.

3.5. Further Parameters

In this study, also further parameters were examined comprising short time heart rate variability, respiratory sinus arrythmia, myofascial stiffness as well as parameters from the small and differential hemogram. We did not find structural influencing by cryotherapy on these parameters, but some small trends could be seen. However, showing and discussing them would go beyond the scope of this paper.

4. Discussion

The research presented in this pilot study shows that a structured 9-week whole body cryotherapy program followed by a 9-week observation period brings about physiological changes. In particular, the decrease in waist circumference and intracellular water levels indicates an enhancement in body composition. Over time there was a reduction in sACE2 levels, hinting at a shift towards vascular and immune system modulation. The immune response showed inflammatory changes with a slight rise in IL 10 and a decrease in TNF alpha levels. These results underscore the impact of cryotherapy on pathways related to immune function and metabolic regulation.

During the follow up, after the intervention (measurement 2) there were impacts seen mainly in vascular indicators like BVP amplitude. Further results indicate that people with stress levels or metabolic load reacted more positively to the treatment. These findings support cryotherapy as a safe, systemic, non-pharmacological intervention with both physiological and immunological relevance.

Further examination of indicators unveiled shifting patterns over time. Significantly noteworthy was the trend in sACE2 levels which exhibited a decline from the assessment to the subsequent evaluation, indicating a plausible systemic adjustment in response to cryotherapy treatments. Given sACE2’s key roles in metabolic and immune regulation, this discovery has significant physiological implications that warrant further investigation.

Interferon gamma (INF-γ) exhibited a stable profile across all three time points, indicating that pro-inflammatory Th1 immune activation remained unaffected by the intervention. In contrast, IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, displayed a mild increase in post-intervention phase suggesting a possible transition towards a regulatory immune phenotype balance. TNFalpha on the other hand demonstrated a lowering trend consistently which is in line with decreasing anti-inflammatory patterns of a cryotherapy intervention.

BVP amplitude variance, as an indicator of peripheral autonomic reactivity, demonstrated a transient increase in post-intervention phase, most prominently in measurement 2, suggesting a momentary stimulation effect on peripheral vasodilation and vascular tone. However, this effect was not sustained at follow-up, indicating an acute, rather than long-term, autonomic response.

Further data analysis offers an understanding of the systemic physiological impacts of the cryotherapy intervention. Most notably, the observed reductions in sACE2 levels and transient changes in anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 suggest a subtle but measurable shift in immune regulation following repeated cold exposure. These findings are consistent with research connecting methods to influencing vascular health as well as metabolic and immune responses through systems such, as the renin–angiotensin system and cytokine pathways.

The decrease in sACE2 is particularly intriguing, given its dual role as a receptor in viral pathogenesis (notably SARS-CoV-2) and as a key regulator of endothelial and cardiovascular homeostasis. The reduction observed post-intervention may reflect an adaptive response to thermal stress, possibly mediated by hormonal or autonomic triggers such as catecholamine release or enhanced endothelial nitric oxide signaling. This finding expands the potential relevance of cryotherapy beyond metabolic and pain-related applications, hinting at broader vascular–immune crosstalk effects.

Momentary Stimulation Effects: A short-term response pattern was observed in some participants, particularly around measurement 2, which coincided with the end of the 9-week cryotherapy protocol. Parameters such as BVP amplitude, IL-10, and bioelectrical impedance analysis phase angle showed temporary enhancements or modulation. These findings support the hypothesis that cryotherapy induces transient systemic stimulation, likely through cold-induced norepinephrine release, endothelial activation, or cytokine communication.

There was no significant improvement in Finger-to-Floor test (FBA), however this may have been influenced that several participants exhibited a higher-than-expected mobility for which our established FBA distance test was not suffice. In future studies the modified Shober Test should be used instead.

The distinction between individuals who respond positively to the treatment and those who do not highlights the differences in how people’s bodies react to it varies greatly from person to person. Those who respond well show enhancements in waist size reduction, hydration levels and immune system characteristics. These trends indicate that certain initial traits like stress levels or metabolic demands could make some people experience improvements. This observation supports a personalized or precision medicine approach to cryotherapy, where baseline phenotype may guide therapeutic application.

Moreover, these subgroup effects align with a growing body of literature indicating that interventions targeting autonomic and immune systems may not produce uniform outcomes but instead trigger targeted regulatory cascades in susceptible physiological networks. Identifying such networks and their phenotypic markers could improve patient stratification in future therapeutic protocols.

In consistency with the Literature, Inflammatory Markers, Stress Reduction, CRP, IL-6, TNF-α show in our data significant decrease in these markers—consistent with numerous reports demonstrating similar effects from Cryosauna treatments and cold-water immersion [

6,

7].

As confirmed in the literature, multiple sessions lead to continuous improvement in physiological parameters through adaptive mechanism, underscoring the long-term benefits of whole-body cryotherapy [

8].

Our research differs from others that may use temperatures, like 110°C or cold water instead, our method centers around a 90°C cold air environment, without any external mechanical factors involved to solely evaluate the thermal impact [

9].

Our consistent 18-session plan allows for an examination of how things adapt over time and helps to document the impact. Through a structured approach we utilized a process to identify not just common signs of inflammation but also subtle variations in the blood cell composition such as the ratio of neutrophils to lymphocytes [

10].

We did not find any connection between the length of the time of single cold exposure and the effects on any of your parameters. However, the minimal length was 3,5 min, the longest time was 6,5 min for a single session [

9].

Elderly individuals face age-related declines in immune function and autonomic nervous system regulation, making them disproportionately susceptible to severe viral infections. Cryotherapy offers a non-pharmacological approach with preliminary evidence of boosting innate and adaptive immunity, restoring autonomic balance, and lowering circulating soluble ACE2 levels—thereby addressing the urgent medical need to enhance host defenses and reduce viral entry in older populations. Out of this medical need for treatment we took older subjects for our study, (40 – 75 years of age and both sexes), while most other WBC studies have taken younger participants and mostly men. The population age for most athletic or obese trials was 20–40 years and young men [

11]. The primary endpoints were targeted at inflammatory cytokines: IL-10, TNF-α shifts in all studies, but younger groups (mostly men) show larger fold-changes. Vascular markers like sACE2 decline are unique to our protocol—no prior WBC trial has tracked this [

11,

12,

13].

We consider mitochondrial aging as one of the factors that would blunt our outcomes. Mitochondria are being continually remodeld through balanced fusion, fission, biogenesis and mitophagy. With age, biogenesis and fusion decline while fission increases and mitophagy becomes insufficient, leading to accumulation of dysfunctional organelles and promoting many age-related diseases. [

14]. The age-associated loss of mitochondrial plasticity—marked by reduced biogenesis, altered dynamics, and compromised quality control—directly contributes to declining VO₂max. Although endurance training benefits all ages, the relative improvements in older adults lag behind those in younger subjects, underscoring the need for targeted interventions to restore mitochondrial function in later life [

15].

The signaling axis driving mitochondrial biogenesis—PGC-1α activation via hormetic ROS and NO—becomes less responsive with age. Older animal models exhibit diminished PGC-1α induction after exercise, concomitant with age-related downregulation of kinases such as AMPK and deacetylases like SIRT1, which together constrain mitochondrial renewal [

16].

Age-related immune remodeling can blunt WBC effects in such a way that inflammation has a higher resting IL-6, TNF-α, CRP baselines reduce the proportional drop post-WBC. Reduced adaptive plasticity may lead to fewer naive T cells and skewed memory/ effector ratios limit acute cytokine swings. A SASP (Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype) means that senescent stromal/immune cells secrete pro-inflammatory mediators that dampen regulatory signals like IL-10. Together, these changes may explain our more modest IL-10 rises and TNF-α reductions compared to younger cohorts.

Effect sizes would expect ~30–50% smaller cytokine shifts than in 20- to 30-year-olds. Sampling timing may hint into the direction that older participants peak later, considering adding 48 h and 72 h post-WBC draws. Tailored protocols would hint to future trials could extend to 20–24 sessions in older adults to achieve cytokine modulation on par with younger samples.

In addition to the discussion about the age of participants, this study has some further limitations: A small number of participants were chosen for the study because of organizational und financial constraints with twenty individuals included, making it more of a preliminary investigation or a pilot study than a full study that would require a larger sample size for validation. In particular, stiffness measurement had an even smaller number of individuals for this type of measurement. Subjects did not show up, so with this limited number of individuals reliable data could not be collected. There were no statistically significant differences in this small group found, so it would be particularly desirable to increase the number of subjects and the number of measurements in stiffness. However, our findings can be used as a basis for the planning and conduct of larger controlled randomized confirmatory trials.

5. Conclusions

Our research results show that undergoing whole body cryotherapy at 90 °C leads to decreases in markers of inflammation and noticeable enhancements in regulation, a similar effect to what is observed with other cold exposure methods. By utilizing a stimulus without any mechanical factors impacting the process our approach unveils subtle adaptation mechanisms and provides fresh perspectives into how the body responds to varying levels of treatment. These findings are essential for enhancing strategies and confirming the practical significance of uniform whole-body cryotherapy.

Collectively, these results and interpretations highlight the complex, multilevel impact of cryotherapy, reaching beyond traditional endpoints such as pain relief or local inflammation. They underscore the need for system-level research frameworks that can account for non-linear, time-sensitive, and individualized responses to therapeutic interventions.

Cryotherapy induced measurable physiological changes across hydration, immune, and vascular systems. The decrease in ACE2 indicate a preserved and potentially modulated systemic regulation. This integrative approach may represent a viable therapeutic adjunct in metabolic and stress-related conditions.

These discoveries underscore the significance of cryotherapy methods and encourage additional investigation into customized implementation plans and lasting outcomes.

Author Contributions

Punito Michael Aisenpreis: Protocol/project development, data collection and management, manuscript writing/editing. Sybille Aisenpreis: data collection, manuscript writing/editing. Manuel Feisst: data analysis, data interpretation, manuscript writing/editing. Robert Schleip: Protocol/project development, manuscript writing/editing. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work and ensure that any questions regarding the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are properly addressed and resolved.

Funding

This study was financially supported by private contributions through the „Stiftung Immunweltmeister e.V“., a non-profit association in Murnau, Bavaria, Germany.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, was registered in the German Register for Clinical Trials (trial no. DRKS 00031033) after approval by the ethical committee of the Bayerische Landesärztekammer (

www.ethikkommission.blaek.de; approval number 22118).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to all those who contributed to the success of this study. Special thanks go to Lena Mühmel, Elisabeth Schmid, Monika Schöps, Diana Ott, and Monika Heidrich for their meticulous support in data collection. I am sincerely grateful to Dr. Ali Grossmann (formerly Roche AG, Penzberg), Dr. Felix Quitterer (Roche AG, Penzberg), and Dr. Wolfgang Mayer (Immumed GmbH/ Lab4more GmbH, Munich) for their invaluable contributions to conceptual planning. My appreciation extends to Ursula Rammelmaier for her guidance on hygiene and planning, and to Dr. Gerti Heiss, Munich, for her leadership and expertise as the supervising medical doctor throughout this project. I also gratefully acknowledge the many contributors of the Stiftung Immunweltmeister, e.V. Murnau, whose generous financial and motivational support sustained this study over many months and played a vital role in its completion.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Punito Michael Aisenpreis, Sybille Aisenpreis and Manuel Feißt declares no conflicts of interest. Author RS is a board member of a non-profit fascia research charity (www.fasciaresearchcharity.org)".

Abbreviations

| The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript |

. |

| BVP |

Blood volume pulse amplitude |

| TICS |

Trier Inventory for Chronic Stress |

| WBC |

Whole-Body Cryotherapy |

References

- Zhu Y, Garcia-Larsen V, Bromage S, Martinez-Steele E, Curi-Hallal AL, Rebholz CM, Matsuzaki M. Association Between Ultraprocessed Food Intake and Self-Reported Arthritis. Am J Prev Med. 2025, 68, 1109–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Núñez-Cortés, R.; Salazar-Méndez, J.; Nijs, J. Physical Activity as a Central Pillar of Lifestyle Modification in the Management of Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain: A Narrative Review. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banfi G., et. al: Effects of whole-body cryotherapy on serum mediators of inflammation and serum muscle enzymes in athletes. Journal of Thermal Biology 2009, 34, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi G, Ziemann E, Banfi G. Whole-Body Cryotherapy in Athletes: From Therapy to Stimulation: An Updated Review of the Literature. Front Physiol. 2017, 8, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doets JJR, Topper M, Nugter AM. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of whole body cryotherapy on mental health problems. Complement Ther Med. 2021, 63, 102783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J. , Zhang, X., Ge, Z. et al. Whole-body cryotherapy can reduce the inflammatory response in humans: a meta-analysis based on 11 randomized controlled trials. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 7759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chun E, Joseph R, Pojednic R Whole-Body Cryotherapy Reduces Systemic Inflammation in Healthy Adults: Pilot Cohort Study. Interact J Med Res 2024, 13, e60942. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouzigon, Romain, et al. "Cryostimulation for post-exercise recovery in athletes: a consensus and position paper.". Frontiers in Sports and Active Living 2021, 3, 688828. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jdidi, H. , de Bisschop, C., Dugué, B., Bouzigon, R., & Douzi, W. Optimal duration of whole-body cryostimulation exposure to achieve target skin temperature: influence of body mass index—a randomized cross-over controlled trial. Journal of Physiological Anthropology 2024, 43, 28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pournot, H. , Bieuzen, F., Louis, J., Fillard, J. R., Barbiche, E., & Hausswirth, C. Time-course of changes in inflammatory response after whole-body cryotherapy multi exposures following severe exercise. PloS one 2011, 6, e22748. [Google Scholar]

- Bouzigon, R. , Grappe, F., Ravier, G., & Dugue, B. Whole-and partial-body cryostimulation/cryotherapy: Current technologies and practical applications. Journal of Thermal Biology 2016, 61, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kusmierczyk, J. , Wiecek, M., Wojciak, G., Mardyła, M., Kreiner, G., Szygula, Z., & Szymura, J. The Effect of Physical Activity and Repeated Whole-Body Cryotherapy on the Expression of Modulators of the Inflammatory Response in Mononuclear Blood Cells among Young Men. Journal of clinical medicine 2024, 13, 2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He Y, Fekete G. The Effect of Cryotherapy on Balance Recovery at Different Moments after Lower Extremity Muscle Fatigue. Physical Activity and Health. 2021, 5, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun N, Youle RJ, Finkel T. The mitochondrial basis of aging. Mol Cell. 2016, 61, 654–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisløff U, Støylen A, Loennechen JP, et al. Superior cardiovascular effect of aerobic interval training versus moderate continuous training in heart failure patients: a randomized study. Circulation. 2007, 115, 3086–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodgers JT, Lerin C, Haas W, et al. Nutrient control of glucose homeostasis through a complex of PGC-1α and SIRT1. Nature. 2005, 434, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).