Submitted:

16 December 2024

Posted:

17 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

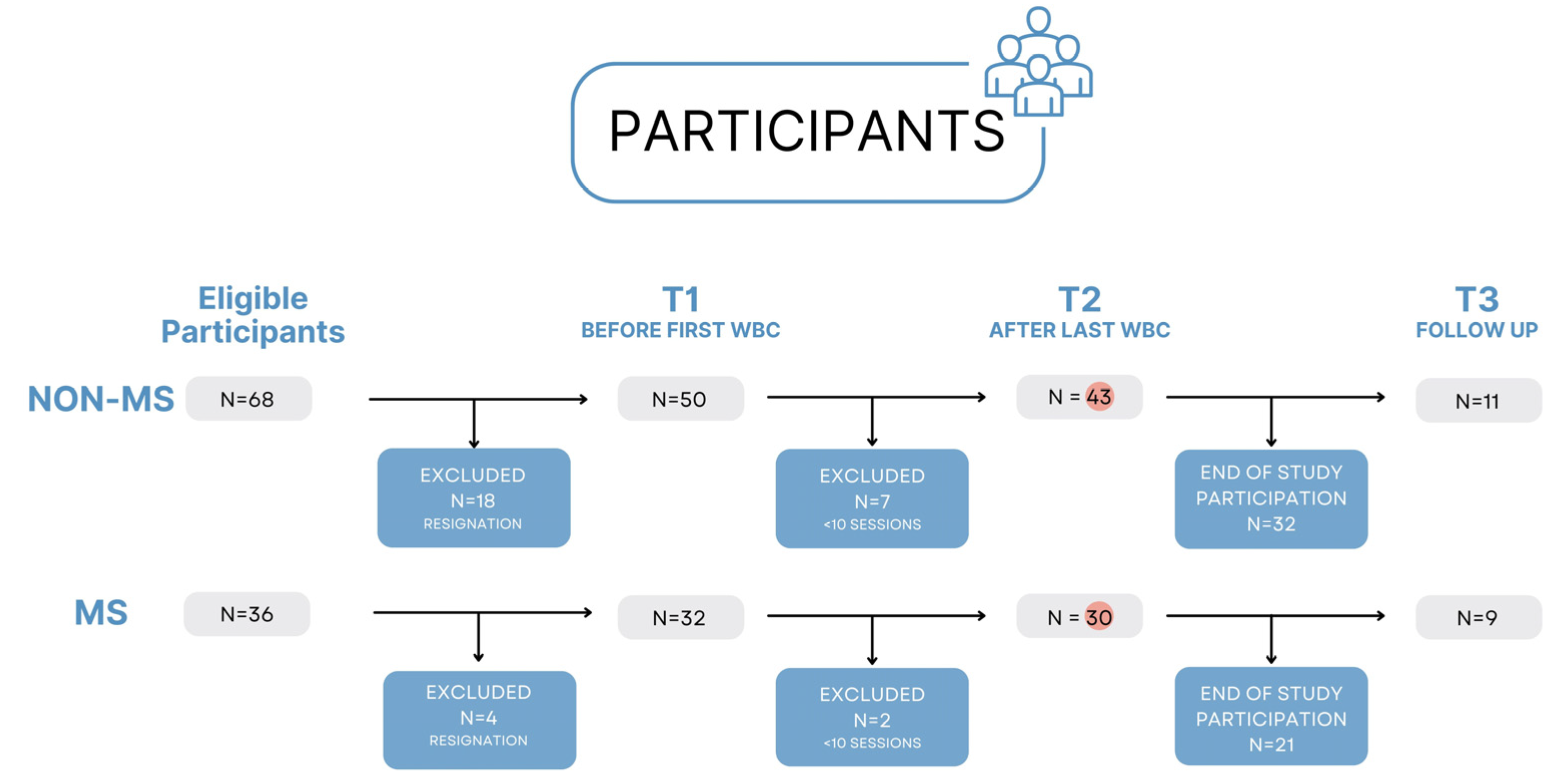

2.1. Participants

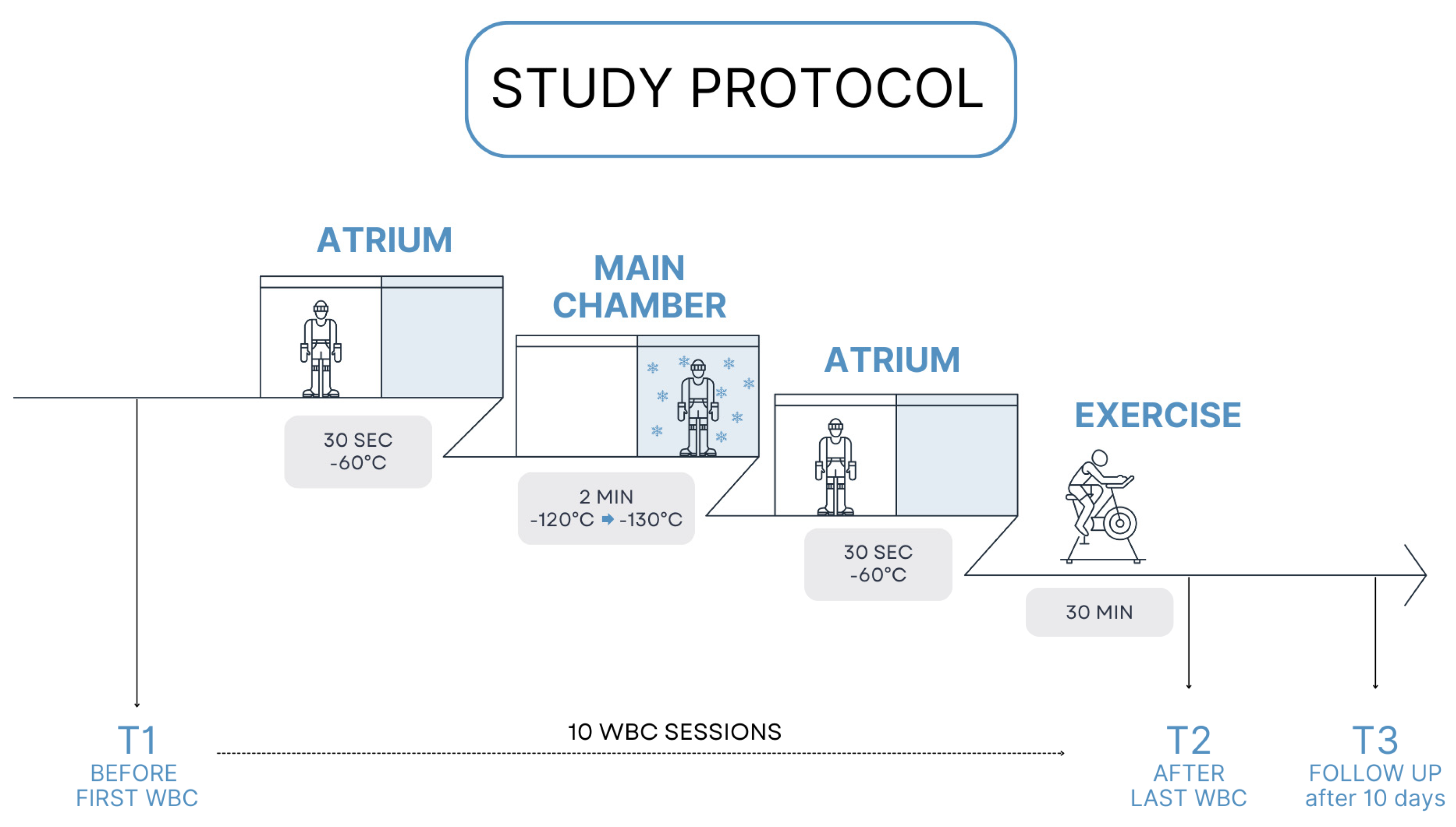

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Assessment Protocol

2.3.1. Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) for Pain Assessment

2.3.2. The World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF)

2.3.3. Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)

2.3.4. 30-Second Chair Stand Test (30CTS)

2.3.5. Timed Up and Go (TUG)

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

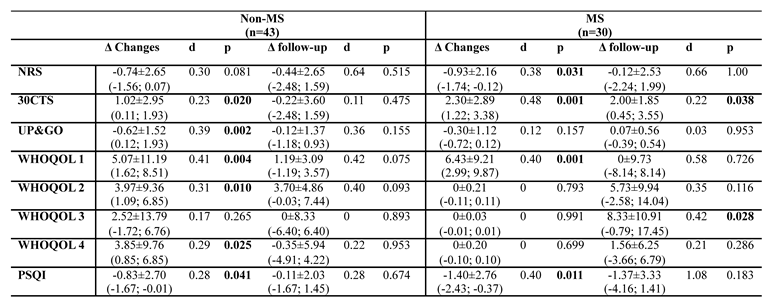

3.1. Changes in Test Results Before WBC, After 10 Sessions and After 10 Days from Last Session

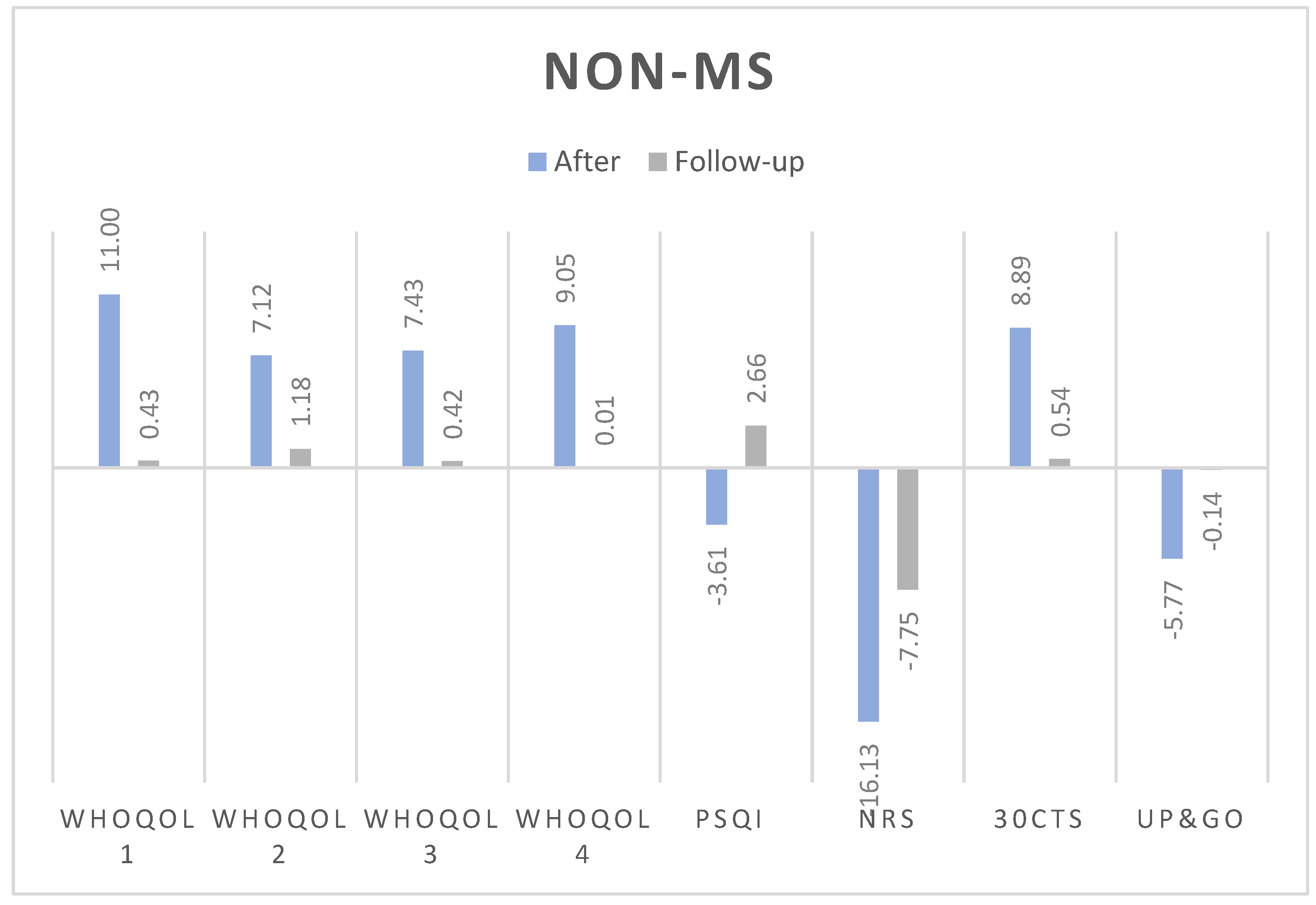

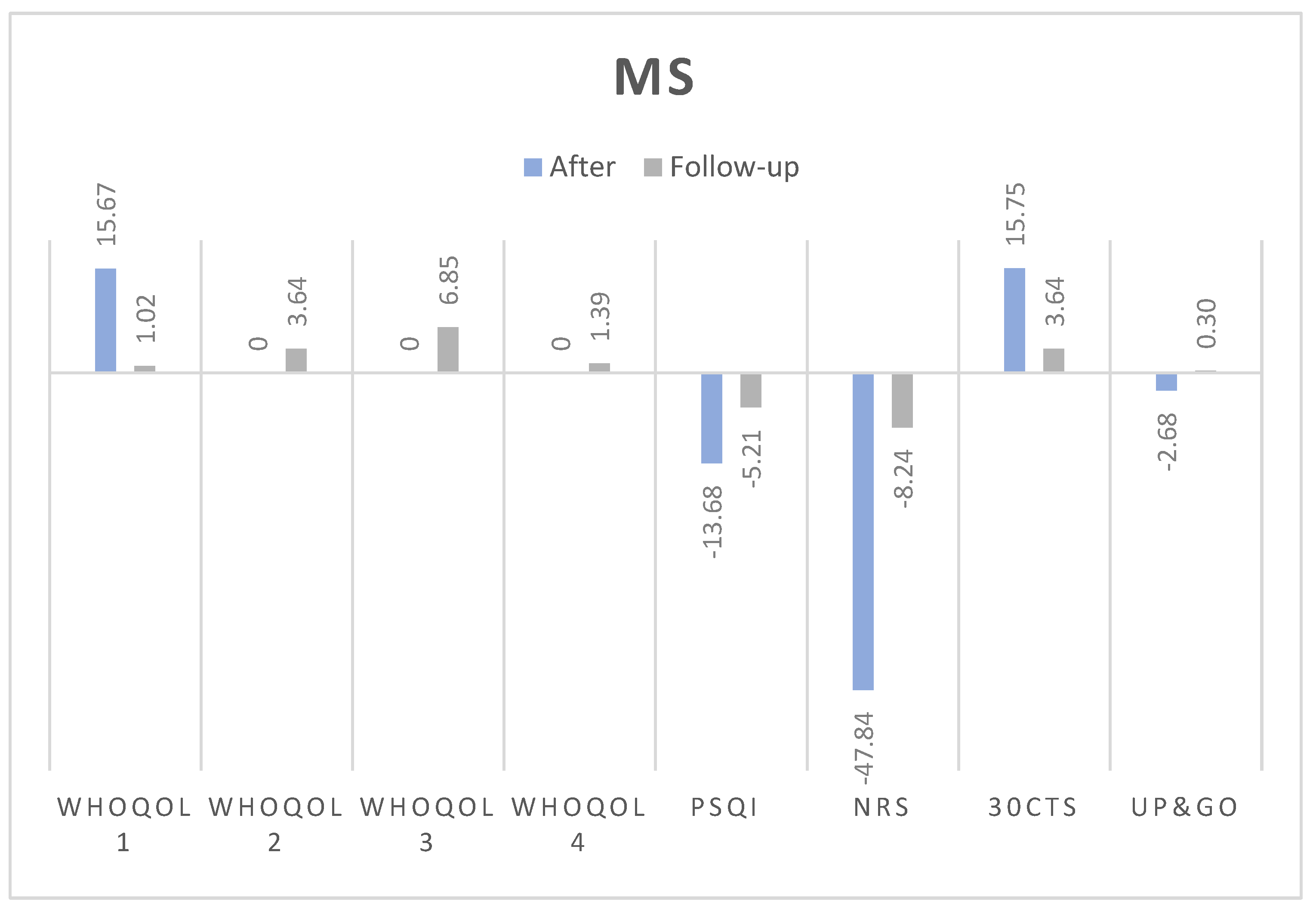

3.1.1. Numerical Rating Scale (NRS):

3.1.2. 30-Second Chair Stand Test (30CTS):

3.1.3. Timed Up and Go (TUG):

3.1.4. WHOQOL Quality of Life Domains:

- Somatic domain: Both groups improved post-treatment. In non-MS, the improvement was statistically significant and medium-sized (Δ = 5.07, p = 0.004, d = 0.41), with no significant effect at follow-up (Δ = 1.19, p = 0.075, d=0.42). Similarly, MS group experienced significant improvements (Δ = 6.43, p = 0.001, d = 0.40), but these did not persist at follow-up (Δ = 0, p = 0.726, d=0.58).

- Psychological domain: Statistically significant improvements were observed in non-MS (Δ = 3.97, p = 0.010, d = 0.31). In MS, the changes were not significant post-treatment (Δ = 0, p = 0.793, d=0).

- Social domain: Improvements were not statistically significant for non-MS group (Δ = 2.52, p = 0.265, d=0.17) but were significant for MS, however only at the follow-up (Δ = 8.33, p = 0.028, d = 0.42).

- Environmental domain: Statistically significant changes were observed in non-MS post-treatment (Δ = 3.85, p = 0.025, d = 0.29), but these were not seen in MS patients at any stage.

3.1.5. Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI):

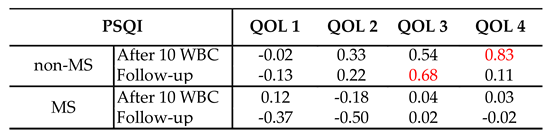

3.2. Correlations Between the Quality of Life and Quality of Sleep After Cryotherapy

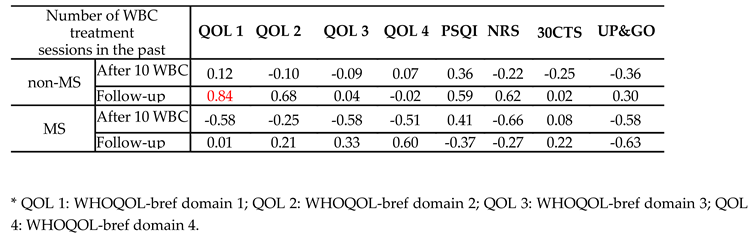

3.3. Correlations Between the Number of Cryotherapy Sessions in the Past and Obtained Test Results

4. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Non-MS | BEFORE | AFTER | FOLLOW-UP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | Median (±95%CI) | Mean±SD | Median (±95%CI) | Mean±SD | Median (±95%CI) | |

| NRS | 4.23±2.71 | 4.00 (3.40; 5.06) |

3.49±2.33M | 3.00 (2.77; 4.21) |

2.89±1.67M | 3.00 (1.58; 3.69) |

| 30CTS | 16.00±4.61 | 16.00 (14.58; 17.42) |

17.02±4.56*S | 16.00 (15.62; 18.43) |

16.45±3.17S | 16.00 (14.32; 18.59) |

| UP&GO | 8.72±1.62 | 8,56 (8.22; 9.21) |

8.10±1.56**M | 7,83 (7.62; 8.58) |

8.15±1.56M | 7,75 (7.10; 9.20) |

| WHOQOL 1 |

63.87±13.55 | 64,29 (59.70; 68.04) |

69.94±11.44**M | 67,85 (65.41; 72.45) |

69.16±8.64M | 71,43 (63.35; 74.96) |

| WHOQOL 2 |

69.57±13.16 | 70,83 (65.52; 73.62) |

73.55±12.92**M | 70,83 (69.57; 77.52) |

74.62±11.7M | 79,17 (66.76; 82.48) |

| WHOQOL 3 | 71.90±16.27 | 75.00 (66.89; 76.90) |

74.42±14.01S | 75.00 (70.10; 78.73) |

71.97±9.33S | 75.00 (65.70; 78.24) |

| WHOQOL 4 | 64.32±14.05 | 65,63 (59.99; 68.64) |

68.17±12.37*M | 71,88 (64.36; 71.97) |

67.33±13.43S | 65,63 (58.31; 76.35) |

| PSQI | 6.07±3.41 | 5.00 (5.02; 7.12) |

5.23±2.5*M | 5.00 (4.46; 6.00) |

5.18±1.89S | 5.00 (3.91; 6.45) |

| MS | BEFORE | AFTER | FOLLOW-UP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | Median (±95%CI) | Mean±SD | Median (±95%CI) | Mean±SD | Median (±95%CI) | |

| NRS | 2.6±2.85 | 1.5 (1.54; 3.66) |

3.49±2.15*S | 0.5 (0.86; 2.47) |

0.89±1.83M | 0 (-0.52; 2.30) |

| 30CTS | 14.7±3.98 | 14.00 (13.21; 16.19) |

17.00±5.55***M | 15.5 (14.93; 19.07) |

15.56±3.71* | 16.00 (12.70; 18.41) |

| UP&GO | 8.42±2.58 | 7.96 (7.46; 9.39) |

8.17±2.51S | 7.82 (7.18; 9.06) |

8.33±3.27S | 8.20 (5.82; 10.84) |

| WHOQOL 1 | 55.83±16.95 | 55.36 (49.50; 62.16) |

62.26±15.77***M | 66.07 (56.37; 68.15) |

65.08±13.81M | 67.85 (54.47; 75.69) |

| WHOQOL 2 |

63.47±13.83 | 64.58 (58.30; 68.63) |

63.47±13.83 | 64.58 (58.31; 68.63) |

68.06±12.5S | 62.5 (58.45; 77.66) |

| WHOQOL 3 | 65.00±20.58 | 66.67 (57.32; 72.68) |

65.00±20.58 | 66.67 (57.32; 72.68) |

73.15±18.53*M | 75.00 (58.90; 87.39) |

| WHOQOL 4 | 67.19±14.33 | 65.63 (61.84; 72.54) |

67.19±14.33 | 65.63 (61.84; 72.54) |

70.14±14.41S | 68.75 (59.06; 81.21) |

| PSQI | 7.8±3.6 | 7.5 (6.45; 9.16) |

6.4±3.58**M | 6.00 (5.06; 7.73) |

4.22±2.49S | 5.00 (2.31; 6.13) |

References

- Jakimovski, D.; Bittner, S.; Zivadinov, R.; Morrow, S.A.; Benedict, R.H.; Zipp, F.; Weinstock-Guttman, B. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet 2024, 403, 183-202. [CrossRef]

- Nick, S.T.; Roberts, C.; Billiodeaux, S.; Davis, D.E.; Zamanifekri, B.; Sahraian, M.A.; Alekseeva, N.; Munjampalli, S.; Roberts, J.; Minagar, A. Multiple sclerosis and pain. Neurol Res 2012, 34, 829-841. [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, A.B.; Schwid, S.R.; Herrmann, D.N.; Markman, J.D.; Dworkin, R.H. Pain associated with multiple sclerosis: systematic review and proposed classification. Pain 2008, 137, 96-111. [CrossRef]

- Kotterba, S.; Neusser, T.; Norenberg, C.; Bussfeld, P.; Glaser, T.; Dörner, M.; Schürks, M. Sleep quality, daytime sleepiness, fatigue, and quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis treated with interferon beta-1b: results from a prospective observational cohort study. BMC Neurol 2018, 18, 123. [CrossRef]

- Vitkova, M.; Gdovinova, Z.; Rosenberger, J.; Szilasiova, J.; Nagyová, I.; Mikula, P.; Krokavcova, M.; Groothoff, J.W.; van Dijk, J.P. Factors associated with poor sleep quality in patients with multiple sclerosis differ by disease duration. Disabil Health J 2014, 7, 466-471. [CrossRef]

- Gil-González, I.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Conrad, R.; Pérez-San-Gregorio, M. Quality of life in adults with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e041249. [CrossRef]

- Haki, M.; Al-Biati, H.A.; Al-Tameemi, Z.S.; Ali, I.S.; Al-Hussaniy, H.A. Review of multiple sclerosis: Epidemiology, etiology, pathophysiology, and treatment. Medicine (Baltimore) 2024, 103, e37297. [CrossRef]

- Konen, F.F.; Möhn, N.; Witte, T.; Schefzyk, M.; Wiestler, M.; Lovric, S.; Hufendiek, K.; Schwenkenbecher, P.; Sühs, K.W.; Friese, M.A.; et al. Treatment of autoimmunity: The impact of disease-modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis and comorbid autoimmune disorders. Autoimmun Rev 2023, 22, 103312. [CrossRef]

- Amatya, B.; Khan, F.; Galea, M. Rehabilitation for people with multiple sclerosis: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019, 1, Cd012732. [CrossRef]

- Razazian, N.; Kazeminia, M.; Moayedi, H.; Daneshkhah, A.; Shohaimi, S.; Mohammadi, M.; Jalali, R.; Salari, N. The impact of physical exercise on the fatigue symptoms in patients with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Neurol 2020, 20, 93. [CrossRef]

- Redlicka, J.; Zielińska-Nowak, E.; Lipert, A.; Miller, E. Impact of Moderate Individually Tailored Physical Activity in Multiple Sclerosis Patients with Fatigue on Functional, Cognitive, Emotional State, and Postural Stability. Brain Sci 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Corrini, C.; Gervasoni, E.; Perini, G.; Cosentino, C.; Putzolu, M.; Montesano, A.; Pelosin, E.; Prosperini, L.; Cattaneo, D. Mobility and balance rehabilitation in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2023, 69, 104424. [CrossRef]

- Zielińska-Nowak, E.; Włodarczyk, L.; Kostka, J.; Miller, E. New Strategies for Rehabilitation and Pharmacological Treatment of Fatigue Syndrome in Multiple Sclerosis. J Clin Med 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Jing, Y.; Li, Y.; Lian, Y.; Li, J.; Li, Z. Rehabilitation treatment of multiple sclerosis. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1168821. [CrossRef]

- Hauser, S.L.; Cree, B.A.C. Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis: A Review. Am J Med 2020, 133, 1380-1390.e1382. [CrossRef]

- Legrand, F.D.; Dugué, B.; Costello, J.; Bleakley, C.; Miller, E.; Broatch, J.R.; Polidori, G.; Lubkowska, A.; Louis, J.; Lombardi, G. Evaluating safety risks of whole-body cryotherapy/cryostimulation (WBC): a scoping review from an international consortium. European journal of medical research 2023, 28, 387.

- Miller, E.; Mrowicka, M.; Malinowska, K.; Mrowicki, J.; Saluk-Juszczak, J.; Kędziora, J. Effects of whole-body cryotherapy on a total antioxidative status and activities of antioxidative enzymes in blood of depressive multiple sclerosis patients. World J Biol Psychiatry 2011, 12, 223-227. [CrossRef]

- Alito, A.; Fontana, J.M.; Franzini Tibaldeo, E.; Verme, F.; Piterà, P.; Miller, E.; Cremascoli, R.; Brioschi, A.; Capodaglio, P. Whole-Body Cryostimulation in Multiple Sclerosis: A Scoping Review. J Clin Med 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Capodaglio, P.; Cremascoli, R.; Piterà, P.; Fontana, J.M. WHOLE-BODY CRYOSTIMULATION: A REHABILITATION BOOSTER. J Rehabil Med Clin Commun 2022, 5, 2810. [CrossRef]

- Thong, I.S.K.; Jensen, M.P.; Miró, J.; Tan, G. The validity of pain intensity measures: what do the NRS, VAS, VRS, and FPS-R measure? Scand J Pain 2018, 18, 99-107. [CrossRef]

- Hawker, G.A.; Mian, S.; Kendzerska, T.; French, M. Measures of adult pain: Visual Analog Scale for Pain (VAS Pain), Numeric Rating Scale for Pain (NRS Pain), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Chronic Pain Grade Scale (CPGS), Short Form-36 Bodily Pain Scale (SF-36 BPS), and Measure of Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain (ICOAP). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011, 63 Suppl 11, S240-252. [CrossRef]

- Skevington, S.M.; Lotfy, M.; O’Connell, K.A. The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Qual Life Res 2004, 13, 299-310. [CrossRef]

- Pomeroy, I.M.; Tennant, A.; Mills, R.J.; Young, C.A. The WHOQOL-BREF: a modern psychometric evaluation of its internal construct validity in people with multiple sclerosis. Qual Life Res 2020, 29, 1961-1972. [CrossRef]

- Curcio, G.; Tempesta, D.; Scarlata, S.; Marzano, C.; Moroni, F.; Rossini, P.M.; Ferrara, M.; De Gennaro, L. Validity of the Italian version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Neurol Sci 2013, 34, 511-519. [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, M.; Beracci, A.; Martoni, M.; Meneo, D.; Tonetti, L.; Natale, V. Measuring Subjective Sleep Quality: A Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [CrossRef]

- Jerković, A.; Mikac, U.; Matijaca, M.; Košta, V.; Ćurković Katić, A.; Dolić, K.; Vujović, I.; Šoda, J.; Đogaš, Z.; Pavelin, S.; et al. Psychometric Properties of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: Factor Structure, Reliability, Correlates, and Discrimination. J Clin Med 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Tulipani, L.J.; Meyer, B.; Allen, D.; Solomon, A.J.; McGinnis, R.S. Evaluation of unsupervised 30-second chair stand test performance assessed by wearable sensors to predict fall status in multiple sclerosis. Gait Posture 2022, 94, 19-25. [CrossRef]

- Özkeskin, M.; Özden, F.; Ar, E.; Yüceyar, N. The reliability and validity of the 30-second chair stand test and modified four square step test in persons with multiple sclerosis. Physiother Theory Pract 2023, 39, 2189-2195. [CrossRef]

- Polidori, A.; Malagoli, M.; Giacalone, R.; Brichetto, G.; Monti Bragadin, M.; Prada, V. 30-Second Chair Stand and 5-Times Sit-to-Stand Tests Are Interesting Tools for Assessing Disability and Ability to Ambulate among Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Life (Basel) 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Kear, B.M.; Guck, T.P.; McGaha, A.L. Timed Up and Go (TUG) Test: Normative Reference Values for Ages 20 to 59 Years and Relationships With Physical and Mental Health Risk Factors. J Prim Care Community Health 2017, 8, 9-13. [CrossRef]

- Valet, M.; Lejeune, T.; Devis, M.; van Pesch, V.; El Sankari, S.; Stoquart, G. Timed Up-and-Go and 2-Minute Walk Test in patients with multiple sclerosis with mild disability: reliability, responsiveness and link with perceived fatigue. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2019, 55, 450-455. [CrossRef]

- Barłowska-Trybulec, M.; Zawojska, K.; Szklarczyk, J.; Góralska, M. Effect of whole body cryotherapy on low back pain and release of endorphins and stress hormones in patients with lumbar spine osteoarthritis. Reumatologia 2022, 60, 247-251. [CrossRef]

- Klemm, P.; Hoffmann, J.; Asendorf, T.; Aykara, I.; Frommer, K.; Dischereit, G.; Müller-Ladner, U.; Neumann, E.; Lange, U. Whole-body cryotherapy for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a monocentric, single-blinded, randomised controlled trial. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2022, 40, 2133-2140. [CrossRef]

- Bettoni, L.; Bonomi, F.G.; Zani, V.; Manisco, L.; Indelicato, A.; Lanteri, P.; Banfi, G.; Lombardi, G. Effects of 15 consecutive cryotherapy sessions on the clinical output of fibromyalgic patients. Clin Rheumatol 2013, 32, 1337-1345. [CrossRef]

- Chruściak, T. Subjective evaluation of the effectiveness of whole-body cryotherapy in patients with osteoarthritis. Reumatologia 2016, 54, 291-295. [CrossRef]

- Bowser, B.; O’Rourke, S.; Brown, C.N.; White, L.; Simpson, K.J. Sit-to-stand biomechanics of individuals with multiple sclerosis. Clin Biomech (Bristol) 2015, 30, 788-794. [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.; Kostka, J.; Włodarczyk, T.; Dugué, B. Whole-body cryostimulation (cryotherapy) provides benefits for fatigue and functional status in multiple sclerosis patients. A case–control study. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 2016, 134, 420-426.

- Radecka, A.; Knyszyńska, A.; Łuczak, J.; Lubkowska, A. Adaptive changes in muscle activity after cryotherapy treatment: Potential mechanism for improvement the functional state in patients with multiple sclerosis. NeuroRehabilitation 2021, 48, 119-131. [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.; Kostka, J.; Włodarczyk, T.; Dugué, B. Whole-body cryostimulation (cryotherapy) provides benefits for fatigue and functional status in multiple sclerosis patients. A case-control study. Acta Neurol Scand 2016, 134, 420-426. [CrossRef]

- Pawik, M.; Kowalska, J.; Rymaszewska, J. The effectiveness of whole-body cryotherapy and physical exercises on the psychological well-being of patients with multiple sclerosis: A comparative analysis. Adv Clin Exp Med 2019, 28, 1477-1483. [CrossRef]

- Mogavero, M.P.; Lanza, G.; Bruni, O.; DelRosso, L.M.; Ferri, R.; Ferini-Strambi, L. Sleep counts! Role and impact of sleep in the multimodal management of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2023, 270, 3377-3390. [CrossRef]

- Douzi, W.; Dupuy, O.; Tanneau, M.; Boucard, G.; Bouzigon, R.; Dugué, B. 3-min whole body cryotherapy/cryostimulation after training in the evening improves sleep quality in physically active men. Eur J Sport Sci 2019, 19, 860-867. [CrossRef]

- Szczepańska-Gieracha, J.; Borsuk, P.; Pawik, M.; Rymaszewska, J. Mental state and quality of life after 10 session whole-body cryotherapy. Psychol Health Med 2014, 19, 40-46. [CrossRef]

- Vitenet, M.; Tubez, F.; Marreiro, A.; Polidori, G.; Taiar, R.; Legrand, F.; Boyer, F.C. Effect of whole body cryotherapy interventions on health-related quality of life in fibromyalgia patients: A randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med 2018, 36, 6-8. [CrossRef]

- Rzepka, M.; Chmiela, T.; Kaczmarczyk, A.; Krzystanek, E. Insomnia, Fatigue, Bladder Disorders and Mood Disorders among Polish Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: Cross-Sectional Study. J Clin Med 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

|

All (n=73) |

NON-MS (n=43) |

MS (n=30) |

|

| Gender | |||

| Females | 62 (83.78) | 39 (88.64) | 23 (76.67) |

| Males | 11 (14.86) | 4 (9.09) | 7 (23.33) |

| Education | |||

| Primary education | 2 (2.70) | 2 (4.54) | 0 |

| Secondary education | 28 (37.84) | 21 (47.73) | 7 (23.33) |

| Higher education | 43 (58.11) | 20 (45.45) | 23 (76.67) |

| Working status | |||

| employed | 45 (60.81) | 22 (50.00) | 23 (76.67) |

| unemployed | 1 (1.35) | 0 | 1 (3.33) |

| retiree | 23 (31.08) | 19 (43.18) | 4 (13.33) |

| Disability pensioner | 4 (5.40) | 2 (4.54) | 2 (6.67) |

| Comorbidities | |||

| No | 36 (48.65) | 18 (40.91) | 18 (60.00) |

| Yes | 37 (51.35) | 25 (59.09) | 12 (40.00) |

| Smoking | |||

| No | 61 (82.43) | 36 (81.82) | 25 (83.33) |

| Yes | 12 (16.22) | 7 (18.18) | 5 (16.67) |

| Special diet | |||

| No | 64 (86.49) | 34 (77.27) | 30 (100.00) |

| Yes | 9 (12.16) | 9 (20.45) | 0 |

| Physical activity | |||

| More than 2 times per week | 33 (44.59) | 20 (45.45) | 13 (43.33) |

| 2 times per week | 15 (20.27) | 11 (25.00) | 4 (13.33) |

| 1 time per week | 13 (17.57) | 7 (15.91) | 6 (20.00) |

| 1 time per month | 3 (4.05) | 1 (2.27) | 2 (6.67) |

| No physical activity | 9 (12.16) | 4 (9.09) | 5 (16.67) |

| WBC in the past | |||

| No | 18 (24.32) | 3 (6.82) | 15 (50.00) |

| Yes | 55 (74.32) | 40 (90.91) | 15 (50.00) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).