1. Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune, inflammatory disease of the central nervous system (CNS) characterized by inflammation, demyelination, and axonal degeneration [

1].

The official World Health Organization website about MS states that it is a diagnosis of exclusion, and there are no definitive diagnostic tests [

2]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows plagues or sclerosis in the brain and spinal cord, but this method is limited in availability, time-consuming, less comfortable for patients, and expensive. The other tests, such as lumbar puncture, optical coherence tomography, and visual evoked potentials, only support the diagnosis. So, an official diagnosis from the onset may be delayed.

Moreover, the diagnosis of MS is complicated because there is no exact, unambiguous set of symptoms, and the sequence of their appearance differs over time. There are more than 50 symptoms of MS [

3], which vary from person to person and depend on the location and severity of nerve fibre damage [

2]. Symptoms can come and go or last for a long time.

A study of prodromal symptoms of MS in primary care settings revealed that patients with MS (PwMS) had a significantly higher risk of presenting up to 10 years before the index date with gastric, intestinal, urinary, and anorectal disturbances, anxiety, depression, insomnia, fatigue, headache, and various types of pain [

4,

5]. Pathogenesis of MS shows that “when patients develop the first symptoms, the disease has been present for a long time, and they may have evidence of old lesions on magnetic resonance imaging and some atrophy of the brain” [

6] (p. 527). Therefore, therapy decisions should be made as soon as possible.

The McDonald criteria allow earlier confirmation of the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis and earlier decisions on therapy [

7]. Evidence of CNS damage that is disseminating in space or appearing in multiple regions of the nervous system and evidence of damage that is disseminating in time or occurring at different points in time are the main criteria that a patient should meet to be diagnosed with MS with clinical isolated syndrome (CIS). A person who has experienced at least two MS relapses and has clear-cut evidence of damage in at least two distinct brain areas can also be diagnosed with MS, as that individual fulfils requirements for both dissemination in space and time. However, fewer relapses or fewer brain areas damaged means additional investigation is needed for a formal diagnosis. Primary progressive MS (PPMS) may be formally diagnosed in people who experience worsening disability for at least one year (based on previous symptoms or ongoing observation) and who exhibit at least two of the following:

The definition of PPMS, especially one-year timing, became a criterion for splitting our study sample into early and delayed diagnosis groups.

However, the studies also show that there are some sociodemographic aspects which represent a barrier that leads to delayed MS diagnosis. Particularly in the population of Italy, it was older age at onset, lower educational level and motor symptoms at onset [

8].

The idea of comparing early and late diagnosis impact on the progress of MS is not new. But the results are ambivalent.

Classic MS often first presents and is diagnosed after the onset of a recognized CIS, where neurological signs and symptoms, such as optic neuritis, partial myelitis and brainstem syndrome, last at least 24 hours. These patients, when treated early in the progression of the disease, tend to have better outcomes. However, for some patients, MS progression is not classic. For example, they may have prodromal symptoms or mild, nonspecific symptoms, such as fatigue, depression and some pain. Including them in the early presenting group and comparing it to the patients presenting to the late presenting group (most of whom had been misdiagnosed for years), the outcomes were similar in both groups after 10 to 15 years [

5]. The possible explanation is that early presenting group patients are more likely to have multiple attacks in the first 2 years after onset; that is, they had more severe disease at the beginning.

Data of prospective cohort design, with eight years of follow-up study, showed that those receiving the first disease-modifying therapy (DMT) within 6 months after diagnosis had lower productivity losses over time, possibly through maintained work capacity compared to those whose first DMT was in more than 6 months [

9]. However, both groups had similar healthcare costs, which first increased and then decreased over time. The other study revealed that early treatment initiation was related to reduced risk of further disability accrual [

10].

A study in Sweden measured outcomes of MS in the 4–10-year period from disease onset. The results showed that earlier commencement of disease-modifying treatment was associated with better patient-reported physical symptoms when measured using a disease-specific metric; however, general quality of life was not affected [

11].

The subjective outcomes of PwMS were the object of interest in our study. And The International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) core set for MS could be considered the right tool for this. ICF defines a common language to describe the impacts of the disease at different levels, which are impairment (problems in anatomical or physiological structures and their symptoms and signs), activity limitation (formerly known as “disability”), participation restriction (formerly known as handicap), and contextual factors (environmental and personal). People with MS may have a combination of deficits, such as physical, cognitive, psychosocial, behavioural, and environmental problems [

12]. Classified according to the WHO ICF, these involve impairments (strength, coordination, balance, spasticity, memory, urinary urgency), resulting in function limitation (mobility, self-care, incontinence, pain, cognitive deficits) and restricted social participation (impact on work, driving, family, finances) [

13].

Every PwMS differs according to sensitivity, attitudes, abilities, experience, and other psychological characteristics. The most significant advantage of such a questionnaire is that all categories are described in detail so that a person can name the subjective meaning of impairment in their life. There are two ICF sets for MS—comprehensive [

14] and brief [

15]- and their selection depends on the researchers’ aims.

The Google Scholar search system currently finds only 50 publications where two keywords, “Multiple sclerosis” and “ICF core set for MS”, appear together. Most of them are designated for developing or validating instruments in different cultures, some about rehabilitation, and some analyse the relationship with other variables. However, no publications use the ICF tool to evaluate different impairment categories from different time perspectives.

Functioning and health are not only an outcome but also the starting point in assessing a patient. It has been reported that independently of the physical disability degree, impaired functioning and participation in social activities can have a major influence on role limitations in work and life [

16]. Studies show that as the disease progresses, the level of working capacity decreases [

17]. Patients with a mild form of MS do not have difficulty with self-care, but later on, with the onset of movement-evoked pain, usual activities become a burden. In one Swiss study, the number of regular MS-diagnosed employees working full-time was very small; a slightly bigger number of MS patients worked part-time, while the rest were unemployed because of the failure to find a job fitting their current disability [

18]. Nevertheless, no publications have related working capacity to the timing of diagnosis.

To summarize, several studies separately analyse the relationship between the timing of diagnosis and later outcomes, or ICF scores, with working capacity, but no study has analysed all these variables together. Thus, this study aimed to compare the scores of the comprehensive ICF core set for Multiple Sclerosis (cICF-MS) in PwMS) who were diagnosed the same or the following year from the onset and who were diagnosed later, and if differences were found, to analyse their value for predicting current work capacity.

2. Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted at Vilnius University, Faculty of Medicine, Institute of Clinical Medicine, Clinic of Neurology and Neurosurgery and at the Disability and Working Capacity Assessment Office (DWCAO) under the Ministry of Social Security and Labour of the Republic of Lithuania. Data were collected from March to August 2022.

2.1. Participants

One hundred fifty-one consecutive patients with MS participated in the study.

The inclusion criteria: 1) age over 18 years but not higher than the retirement age; 2) MS diagnosis according to the McDonald criteria 2017 revisions [

7]; 3) MS at remission stage and stable neurological condition; 4) fluent in the Lithuanian language; 5) disability assessed at DWCAO; and 6) voluntary consent to participate in the study certified by the participant’s signed informed consent form.

The exclusion criteria were: 1) patients not fulfilling the inclusion criteria and 2) patients not compliant with the study protocol.

2.2. Data Collection

1) Sociodemographic (age, sex, education, employment) and clinical data (value of Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS), type of MS, disease duration, comorbidities and medication) were collected by leading investigator D.V. from journal recordings at DWCAO.

2) The Comprehensive International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (cICF) Core Set for MS consists of 138 categories: body functions—40, body structures—7, activities and participation—53, and environmental factors—38. Comprehensive ICF data for the PwMS were collected by leading investigator D.V. by telephone interviews (approximately 40 min per participant) and journal recording at DWCAO due to legal limitations on face-to-face contact during COVID-19 pandemic restrictions.

The categories b1308 (energy and drive functions, other specified); b235 (vestibular functions); b445 (respiratory muscle functions); b5508 (thermoregulatory functions, other specified (sensitivity to heat)); b5508 (thermoregulatory functions, other specified (sensitivity to cold)); b640 (sexual functions) and b710 (mobility of joint functions); s610 (structure of urinary system); s730 (structure of upper extremity); s750 (structure of lower extremity); s760 (structure of trunk) and s810 (structure of areas of skin); e1108 (products or substances for personal consumption, other specified) were not evaluated due to lack of available information.

The extent or magnitude of ICF category impairment was determined according to the instructions in the online ICF book [

19]. The instructions are as follows:

0 = NO impairment (none, absent, negligible): a reduction of function by 0-4%;

1 = MILD impairment: slight or low reduction of function by 5-24%;

2 = MODERATE impairment: medium or fair reduction of function by 25-49%;

3 = SEVERE impairment: high or extreme reduction of function by 50-95%;

4 = COMPLETE impairment: total reduction in function by 96-100%

More detailed information about cICF scores in this study could be found in the primary study report [

20].

3) WCL refers to the “ability of a person to implement a professional competency previously gained, to acquire a new professional competency, or to perform jobs that require lower professional competency”, and its criteria and procedures are approved by the order of the Ministers of Social Security, Labor, and Health [

21]. The WCL was established after a complex assessment of the medical criteria (i.e., the person’s basic work capacity) and the criteria of the person’s activities and ability to participate.

Work capacity is evaluated in five-percentage-point intervals, ranging from 0 to 100 (where 0–25% indicates total incapacity for work, 30–55% indicates a partial capacity for work, and 60–100% indicates that a person is capable of working). In Lithuania, all persons assessed at 0–55% of working capacity are designated “persons with disabilities” and are guaranteed legislatively determined benefits according to this status—the lower the percentage of working capacity scores, the more severe the disability.

More detailed information about the assessment of WCL can be read on the official website [

22].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the statistical software package SPSS 17.0 (version for MS Windows). Descriptive statistics for the quantitative variables are presented as the mean and standard deviation; discrete variables are presented as the absolute value and the percentage of the analysed sample group. Comparisons between groups were conducted using the Student t test, Mann-Whitney U test or Chi-square test. Multiple stepwise regression analysis was applied to predict working capacity.

3. Results

The duration from onset to diagnosis is the main variable of this study. Its average time was M=2.3, SD=4.0, Median = 1, Min = 0, Max = 30 years. Based on a reasonable time to set the diagnosis from the first symptoms, it was decided to divide the full sample into two groups: PwMS, who were diagnosed within one year from onset (N=96; early group) and PwMS, who were diagnosed within two or more years from onset (N=55, delayed group).

To compare the cICF scores of these groups, it was important to ensure that both groups do not differ by clinicodemographic data. Results presented in

Table 1 show that these groups were statistically equal in terms of age, gender, education, employment, disease type, disease-modifying treatments, comorbidities, EDSS, and work capacity score.

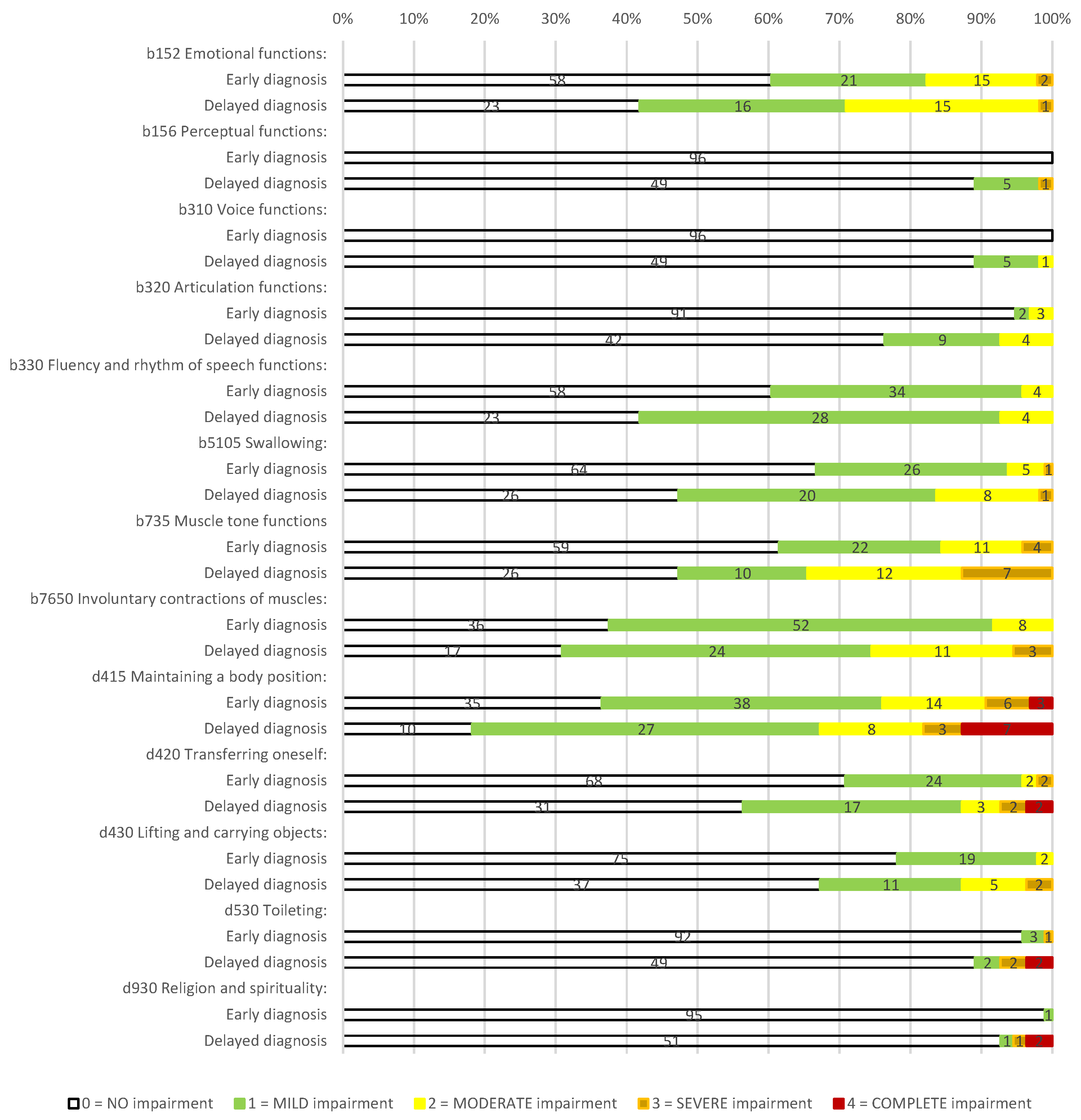

The second step of the analysis was directly related to the paper’s aim: to evaluate if delayed diagnosis of MS is related to more significant functional impairment at follow-up. 125 categories (33 body functions, 2 body structures, 53 activities and participation, 37 environmental factors) were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test between early and delayed diagnosis groups. Only 13 categories of cICF were found to be related to duration from onset to diagnosis (

Table 2).

While analysing data in

Table 2, it is seen that 8 differences were found among impairment of body functions and 5 among activities and participation categories. No differences were found between body structures and environmental factors.

The biggest difference between groups was for d415 Maintaining a body position (M

early = 1.00, M

delayed = 1.45, p = .016).

Figure 1 shows a detailed distribution between impairment groups for each category. It is seen that 7 (12.7%) PwMS in the delayed diagnosis group had complete impairment in this cICF category at follow-up.

The most impaired body function (62.5% in the early diagnosis group and 69.1% in the delayed diagnosis group) was b7650 Involuntary contractions of muscles.

Analysing in a dichotomous way, if it was impairment or not, more than 15% difference between groups in b152 Emotional functions and b330 Fluency and rhythm of speech function (both categories 39.6% PwMS functioning was impaired in early diagnosis group and 58.2% in delayed diagnosis group), b5105 Swallowing (33.3% impaired in early diagnosis group and 52.7% in delayed diagnosis group), b320 Articulation functions (5.2% impaired in early diagnosis group and 23.6% in delayed diagnosis group).

It is important to note that two categories—b156 Perceptual functions and b310 Voice functions were not impaired in the early diagnosis group.

In the last stage of data analysis, the categories from

Table 2 were entered into stepwise regression analysis as predictors of the working capacity of the entire sample. If predictors for working capacity were not found, that would mean that all the differences in categories listed above are not affecting the main functioning of a person, that is the ability to work. However, the predictors were found, which means that the time of diagnosis may be related to work capacity. The results of the final step are presented in

Table 3.

There were three statistically significant categories predicting working capacity: d415 Maintaining a body position, b156 Perceptual functions, b735 Muscle tone functions. Negative beta coefficients mean that the higher ICF scores are related to lower working capacity scores. Together, this could explain 37.7 per cent of working capacity data distribution.

4. Discussion

During, on average 11 years from MS diagnosis till follow-up study, there can happen plenty of things, which may result in better or worse functioning of PwMS. This study aimed to analyse if delayed MS diagnosis is related to bigger impairment assessed by cICF. 125 comparisons were made, and differences were found in only 13 categories (10.4%). This supports the findings of other researchers, who found that early and delayed diagnosis have similar outcomes after 10 or 15 years [

5,

11].

It also should be noted that no categories in ICF body structures and environmental factors domains were more impaired in one group than in another. That may mean alike progression of MS in both groups, alike effects of treatment, or equal solutions for both groups in adapting their environment and support system.

In the literature review, it was mentioned that there are two sets of ICF for MS. The comprehensive one is typically applicable for assessing individual problems and needs and for estimating prognosis and the potential for rehabilitation. The brief is based on their ability to discriminate between patients with high or low-functioning status [

19]. Interestingly, only one category from brief set b152, Emotional functions, was among those where differences between early and delayed diagnosis groups were found. This category itself covers a wide range of emotions, like depressive symptoms, anxiety, or anger [

23]; thus, such results may mean a lack of attention to the psychological condition of such patients.

Category d415 Maintaining a body position was most impaired in both groups (with significantly higher results in the delayed group), and it was the strongest predictor of working capacity. Currently, most occupations require staying in the same body position, such as remaining seated or standing and maintaining a lying, squatting, or kneeling position. Impairment in this ICF category may be explained by neuroimaging research. The study of biomarkers of MS disability progression showed that the earliest were structural disconnections due to paramagnetic rim lesions in the motor-related regions [

24].

Even though the study sample consisted only of PwMS, who applied for their work capacity assessment, 63.6% of them were diagnosed within 1 year from the onset, which shows good functioning of medical care in Lithuania, and this fit the data from other European countries [

25,

26].

Study design and its implementation have some limitations. First, the authors did not consider any differences in the baseline impairments of PwMS at the time of diagnosis. MS manifests itself in very different forms, and data about the first symptoms and their progression would enrich the study data.

Second, the 11-year time gap between diagnosis and survey means that many confounding factors, such as disease progression, treatment adherence, and lifestyle changes, may have influenced ICF scores independently of the timing of diagnosis. The study relies on participants who were available and willing to participate after 11 years, potentially excluding those with more severe disease or those who have passed away, which could skew the results.

Third, the study’s cross-sectional nature limits the ability to establish causality between delayed diagnosis and higher ICF scores in the 13 categories.

Fourth, categorising “early diagnosis” versus “delayed diagnosis” may not fully capture the nuances of diagnostic pathways, including potential misdiagnoses or delays due to atypical symptom presentation.

Finally, the study aimed to analyse the relationship between ICF scores and working capacity. However, work is not the only aspect of a fulfilling life, and the relationship of ICF scores with social life or personal realisation could inspire future research.

5. Conclusions

Knowing that MS diagnosis was delayed can be a big psychological hardship for PwMS, including feelings of uncertainty and anxiety, betrayal, and a sense of regret or grief over the missed opportunity for early intervention, which could have potentially altered the disease course or preserved their functional abilities. Thus, data-based information about the functioning of PwMS at longer period follow-up is important not only for researchers but also for the patients themselves.

This study proved that delayed diagnosis of MS is related to some worsening of functioning according to the ICF scale, but these impairments are not crucial. To keep up working capacity most attention should be paid to the category d415 Maintaining a body position and preventive actions like exercise therapy should be taken.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.Ž., D.V. and D.J.; methodology, I.Ž. and D.V.; software, I.Ž.; validation, D.V; formal analysis, I.Ž; investigation, D.V.; resources, D.J.; data curation, I.Ž; writing—original draft preparation, I.Ž.; writing—review and editing, I.Ž, D.V. and D.J.; visualization, I.Ž.; supervision, D.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Lithuanian Bioethics Committee (No. 2021/10–1387-855) on October 26, 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the primary investigator and co-author D. V. upon reasonable request. Data are located in controlled access data storage at Vilnius University

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jakimovski, D.; Bittner, S.; Zivadinov, R.; Morrow, S.A.; Benedict, R.H.B.; Zipp, F.; Weinstock-Guttman, B. Multiple Sclerosis. Lancet 2024, 403, 183–202. [CrossRef]

- Multiple Sclerosis Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/multiple-sclerosis (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Emrich, L. Top 50 Symptoms of Multiple Sclerosis. Available online: https://www.healthcentral.com/article/top-50-symptoms-of-multiple-sclerosis (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Disanto, G.; Zecca, C.; MacLachlan, S.; Sacco, R.; Handunnetthi, L.; Meier, U.C.; Simpson, A.; McDonald, L.; Rossi, A.; Benkert, P.; et al. Prodromal Symptoms of Multiple Sclerosis in Primary Care. Ann. Neurol. 2018, 83, 1162–1173. [CrossRef]

- Zachariah, J.; Quezada, T.; Desai, T.; Schorr, R.E.; Scott, T.F. Real World Prognosis in MS: Does Early versus Late Diagnosis Matter? Neurol. Res. 2021, 43, 458–463. [CrossRef]

- Murray, T.J. Diagnosis and Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis. BMJ 2006, 332, 525–527. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.J.; Banwell, B.L.; Barkhof, F.; Carroll, W.M.; Coetzee, T.; Comi, G.; Correale, J.; Fazekas, F.; Filippi, M.; Freedman, M.S.; et al. Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis: 2017 Revisions of the McDonald Criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 162–173. [CrossRef]

- Patti, F.; Chisari, C.G.; Arena, S.; Toscano, S.; Finocchiaro, C.; Fermo, S.L.; Judica, M.L.; Maimone, D. Factors Driving Delayed Time to Multiple Sclerosis Diagnosis: Results from a Population-Based Study. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2022, 57, 103361. [CrossRef]

- Karampampa, K.; Gyllensten, H.; Murley, C.; Alexanderson, K.; Kavaliunas, A.; Olsson, T.; Manouchehrinia, A.; Hillert, J.; Friberg, E. Early vs. Late Treatment Initiation in Multiple Sclerosis and Its Impact on Cost of Illness: A Register-Based Prospective Cohort Study in Sweden. Mult. Scler. J. Exp. Transl. Clin. 2022, 8. [CrossRef]

- Tintore, M.; Cobo-Calvo, A.; Carbonell, P.; Arrambide, G.; Otero-Romero, S.; Río, J.; Tur, C.; Comabella, M.; Nos, C.; Arévalo, M.J.; et al. Effect of Changes in MS Diagnostic Criteria over 25 Years on Time to Treatment and Prognosis in Patients with Clinically Isolated Syndrome. Neurology 2021, 97, e1641–e1652. [CrossRef]

- He, A.; Spelman, T.; Manouchehrinia, A.; Ciccarelli, O.; Hillert, J.; McKay, K. Association between Early Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis and Patient-Reported Outcomes: A Nationwide Observational Cohort Study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2023, 94, 284–289. [CrossRef]

- International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Available online: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health (accessed on 21 December 2024).

- Gómez-Melero, S.; Caballero-Villarraso, J.; Escribano, B.M.; Galvao-Carmona, A.; Túnez, I.; Agüera-Morales, E. Impact of Cognitive Impairment on Quality of Life in Multiple Sclerosis Patients—A Comprehensive Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3321. [CrossRef]

- Comprehensive ICF Core Set for Multiple Sclerosis Available online: https://www.icf-research-branch.org/component/jdownloads/?task=download.send&id=134&catid=8&m=0&Itemid=1626 (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- Brief ICF Core Set for Multiple Sclerosis Available online: https://www.icf-research-branch.org/component/jdownloads/?task=download.send&id=107&catid=8&m=0&Itemid=1626 (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- Holper, L.; Coenen, M.; Weise, A.; Stucki, G.; Cieza, A.; Kesselring, J. Characterization of Functioning in Multiple Sclerosis Using the ICF. J. Neurol. 2010, 257, 103–113. [CrossRef]

- González Torre, J.A.; Cruz-Gómez, Á.J.; Belenguer, A.; Sanchis-Segura, C.; Ávila, C.; Forn, C. Hippocampal Dysfunction Is Associated with Memory Impairment in Multiple Sclerosis: A Volumetric and Functional Connectivity Study. Mult. Scler. 2017, 23, 1854–1863. [CrossRef]

- Findling, O.; Baltisberger, M.; Jung, S.; Kamm, C.P.; Mattle, H.P.; Sellner, J. Variables Related to Working Capability among Swiss Patients with Multiple Sclerosis—A Cohort Study. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0121856. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization(WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF; World Health Organization: Genève, Switzerland, 2001; ISBN 9789241545426.

- Valadkevičienė, D.; Jatužis, D.; Žukauskaitė, I.; Danylaitė Karrenbauer, V.; Bileviciute-Ljungar, I. Revision of the Brief International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Core Set for Multiple Sclerosis: A Study of the Comprehensive Icf Core Set for Multiple Sclerosis with Participants Referred for Work Ability Assessment. J. Rehabil. Med. 2024, 56, jrm19671. [CrossRef]

- Valadkevičienė, D. The biopsychosocial aspects of disability assessment in patients with multiple sclerosis. Doctoral thesis, Vilnius University, Lithuania, 2019.

- Capacity for work assessment level. Available online: https://ndnt.lrv.lt/en/capacity-for-work-assessment-level/ (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Coenen, M.; Basedow-Rajwich, B.; König, N.; Kesselring, J.; Cieza, A. Functioning and Disability in Multiple Sclerosis from the Patient Perspective. Chronic Illn. 2011, 7, 291–310. [CrossRef]

- Tozlu, C.; Olafson, E.; Jamison, K.W.; Demmon, E.; Kaunzner, U.; Marcille, M.; Zinger, N.; Michaelson, N.; Safi, N.; Nguyen, T.; et al. The Sequence of Regional Structural Disconnectivity Due to Multiple Sclerosis Lesions. Brain Commun. 2023, 5, fcad332. [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, M.; Kuhle, J.; Puhan, M.A.; Kamm, C.P.; Chan, A.; Salmen, A.; Kesselring, J.; Calabrese, P.; Gobbi, C.; Pot, C.; et al. Factors Associated with Time from First-Symptoms to Diagnosis and Treatment Initiation of Multiple Sclerosis in Switzerland. Mult. Scler. J. Exp. Transl. Clin. 2018, 4, 2055217318814562. [CrossRef]

- Aires, A.; Barros, A.; Machado, C.; Fitas, D.; Cação, G.; Pedrosa, R.; Cerqueira, J.; Perdigão, S.; Silva, A.M.; Vale, J.; et al. Diagnostic Delay of Multiple Sclerosis in a Portuguese Population. Acta Med. Port. 2019, 32, 289–294. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).