Submitted:

17 September 2025

Posted:

18 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Objectives

2.2. Ehical Considerations and Data Collections

2.3. Methods

Study Poplulation

Sleep Sub-Study

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

3.2. Cognitive Performance and Quality of Life Assessements

3.3. Correlations Between Physical Disability and Cognitive Function Measures

3.4. Correlations Between MSIS-29 and Quality of Life Measures

3.5. Correlations Between Quality of Life scores, Cognitive Function and Physical Disability Measures

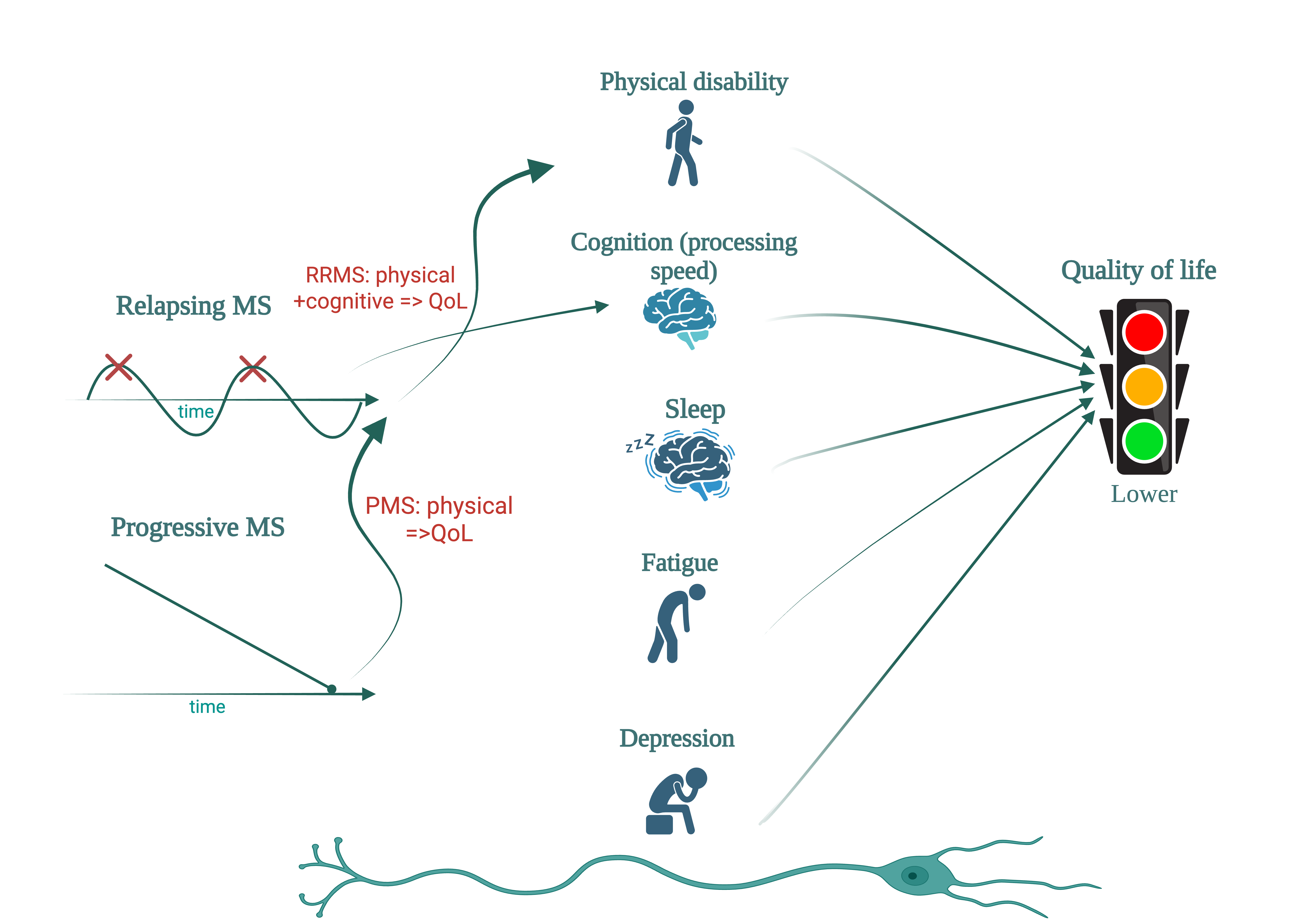

3.6. Subgroup Analysis: Relapsing vs Progressive Forms – Quality of Life, Physical Disability and Cognitive Function

3.7. Subgroup Analysis: Sleep Quality

3.8. ANOVA Analysis of Sleep Disturbance

| Group | Nr | MSIS 29 | BDI | ESS | MFIS p | MFIS c |

| NO | 13 | 39.9 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 16.6 | 12.6 |

| <1/Week | 11 | 47.5 | 4.8 | 5.2 | 9.8 | 7.6 |

| 1,2/Week | 1 | 106 | 20 | 12 | 39 | 29 |

| >=3/Week | 4 | 77 | 22 | 13.25 | 36.5 | 30.75 |

| p | 0.000572 | 0.000604 | 0.003256 | 0.000364 | 0.000212 |

| Group | Nr | BD | MFIS t |

|

NO |

4 |

2.5 |

14 |

|

<1/Week |

12 | 2.3 | 16.4 |

|

1,2/Week |

4 | 16.26 | 47 |

|

>=3/Week |

9 | 14.1 | 51.3 |

| p | 0.000734 | 0.000146 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Daundasekara, S.S.; Arlinghaus, K.R.; Johnston, C.A. Quality of Life: The Primary Goal of Lifestyle Intervention. Am J Lifestyle Med 2020, 14, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compston, A.; Coles, A. Multiple sclerosis. The Lancet 2008, 372, 1502–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-González I, Martín-Rodríguez A, Conrad R, Pérez-San-Gregorio MÁ. Quality of life in adults with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e041249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, B.P.; Vickrey, B.; Hays, R.D.; et al. A comparison of health-related quality of life in patients with epilepsy, diabetes and multiple sclerosis. Epilepsy Res 1996, 25, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalachkov, Y.; Soydaş, D.; Bergmann, J.; et al. Determinants of quality of life in relapsing-remitting and progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2019, 30, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siger, M. Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Primary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis Patients: Review. Clin Neuroradiol 2022, 32, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.J.; Banwell, B.L.; Barkhof, F.; et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol 2018, 17, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumstarck, K.; Boyer, L.; Boucekine, M.; Michel, P.; Pelletier, J.; Auquier, P. Measuring the Quality of Life in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis in Clinical Practice: A Necessary Challenge. Mult Scler Int 2013, 2013, 524894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtzke, J.F. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: An expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 1983, 33, 1444–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J.S.; Rudick, R.A.; Cutter, G.R.; Reingold, S.C. The multiple sclerosis functional composite measure (MSFC): An integrated approach to MS clinical outcome assessment. Multiple Sclerosis 1999, 5, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer-Moock, S.; Feng, Y.S.; Maeurer, M.; Dippel, F.W.; Kohlmann, T. Systematic literature review and validity evaluation of the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) and the Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite (MSFC) in patients with multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol 2014, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meo, E.; Portaccio, E.; Giorgio, A.; et al. Identifying the Distinct Cognitive Phenotypes in Multiple Sclerosis. JAMA Neurol 2021, 78, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corfield, F.; Langdon, D. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Brief Cognitive Assessment for Multiple Sclerosis (BICAMS). Neurol Ther 2018, 7, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavitt, V.M.; Tosto, G.; Riley, C.S. Cognitive phenotypes in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2018, 265, 562–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedict, R.H.B.; Amato, M.P.; DeLuca, J.; Geurts, J.J.G. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis: clinical management, MRI, and therapeutic avenues. Lancet Neurol 2020, 19, 860–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potticary, H.; Langdon, D. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Brief Cognitive Assessment for Multiple Sclerosis (BICAMS) International Validations. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagenais, E.; Rouleau, I.; Demers, M.; et al. Value of the MoCA test as a screening instrument in multiple sclerosis. Can J Neurol Sci 2013, 40, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borkowska, A.R.; Daniluk, B.; Adamczyk, K. Significance of the diagnosis of executive functions in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Moreno, S.M.; Cuadrado, M.L.; Cruz-Orduña, I.; et al. Validation of the Spanish-language version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment as a screening test for cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Neurología (English Edition) 2022, 37, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoops, S.; Nazem, S.; Siderowf, A.D.; et al. Validity of the MoCA and MMSE in the detection of MCI and dementia in Parkinson disease. Neurology 2009, 73, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, Q.C.; Cervin, M.; Choo, CC.; et al. Examining the validity of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and its domains using network analysis. Psychogeriatrics 2024, 24, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Laethem, D.; De Cock, A.; Van Schependom, J.; Benedict, R.H.B.; Nagels, G.; D’hooghe, M. Correlates of patient-reported cognitive performance with regard to disability. Sci Rep 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobart, J.; Lamping, D.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Riazi, A.; Thompson, A. The multiple sclerosis impact scale (MSIS-29) a new patient-based outcome measure. Brain 2001, 124, 962–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tur, C. Fatigue Management in Multiple Sclerosis. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2016, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, J.; Kobelt, G.; Gannedahl, M.; Berg, J. Association between Disability, Cognition, Fatigue, EQ-5D-3L Domains, and Utilities Estimated with Different Western European Value Sets in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Value in Health 2019, 22, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, K.H.; Ford, D.V.; Jones, P.A.; et al. How People with Multiple Sclerosis Rate Their Quality of Life: An EQ-5D Survey via the UK MS Register. PLoS One 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawton, A.; Green, C.; Telford, C.; Zajicek, J.; Wright, D. Using the multiple sclerosis impact scale to estimate health state utility values: Mapping from the MSIS-29, version 2, to the EQ-5D and the SF-6D. Value in Health 2012, 15, 1084–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, K.; Yoshiike, T.; Nagao, K.; et al. Association of subjective quality and quantity of sleep with quality of life among a general population. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerković, A.; Mikac, U.; Matijaca, M.; et al. Psychometric Properties of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: Factor Structure, Reliability, Correlates, and Discrimination. J Clin Med 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołtuniuk, A.; Kazimierska-Zajacą, M.; Pogłódek, D.; Chojdak-łukasiewicz, J. Sleep Disturbances, Degree of Disability and the Quality of Life in Multiple Sclerosis Patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billings, M.E.; Hale, L.; Johnson, D.A. Physical and Social Environment Relationship With Sleep Health and Disorders. Chest 2020, 157, 1304–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.; Shin, K.; Shin, C. Development of the Sleep Quality Scale. J Sleep Res 2006, 15, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F.; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research [Índice de calidad del sueño de Pittsburgh: un nuevo instrumento para la práctica y la investigación psiquiátrica]. Psychiatry Res 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, R.; Babson, K.; Menno, D.; et al. Test–retest reliability of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale in clinical trial settings. J Sleep Res 2022, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solaro, C.; Trabucco, E.; Signori, A.; et al. Depressive Symptoms Correlate with Disability and Disease Course in Multiple Sclerosis Patients: An Italian Multi-Center Study Using the Beck Depression Inventory. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0160261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degraeve, B.; Lenne, B.; Norberciak, L.; Massot, C.; Donze, C. A comparative analysis of depression screening tools in multiple sclerosis: Implications for diagnosis and prevalence. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2025, 93, 106220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mey, G.M.; Mahajan, K.R.; DeSilva, T.M. Neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis. WIREs Mechanisms of Disease 2023, 15, e1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrogianni, K.; Giannopapas, V.; Kitsos, D.K.; et al. Cognitive Impairment in Newly Diagnosed Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review of Related Molecular Biomarkers and a Meta-Analysis of Associated Demographic and Disease-Related Characteristics. J Clin Med 2025, 14, 2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medana, I.M.; Esiri, M.M. Axonal damage: a key predictor of outcome in human CNS diseases. Brain 2003, 126, 515–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, G.; Hashim, M.J. Epidemiology of Multiple Sclerosis: Global, Regional, National and Sub-National-Level Estimates and Future Projections. J Epidemiol Glob Health 2025, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luetic, G.G.; Menichini, M.L.; Vrech, C.; et al. Clinical and demographic characteristics of male MS patients included in the national registry-RelevarEM. Does sex or phenotype make the difference in the association with poor prognosis? Mult Scler Relat Disord 2022, 58, 103401. [Google Scholar]

- Correale, J.; Rush, C.A.; Barboza, A. Are highly active and aggressive multiple sclerosis the same entity? Front Neurol 2023, 14, 1132170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purmonen, T.; Hakkarainen, T.; Tervomaa, M.; Ruutiainen, J. Impact of multiple sclerosis phenotypes on burden of disease in Finland. J Med Econ 2020, 23, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lublin, F.D.; Häring, D.A.; Ganjgahi, H.; et al. How patients with multiple sclerosis acquire disability. Brain 2022, 145, 3147–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inojosa, H.; Schriefer, D.; Ziemssen, T. Clinical outcome measures in multiple sclerosis: A review. Autoimmun Rev 2020, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uitdehaag, B.M.J. Clinical outcome measures in multiple sclerosis. Handb Clin Neurol 2014, 122, 393–404. [Google Scholar]

- Højsgaard Chow, H.; Schreiber, K.; Magyari, M.; et al. Progressive multiple sclerosis, cognitive function, and quality of life. Brain Behav 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehanovic, A.; Kunic, S.; Ibrahimagic, O.C.; et al. Contributing Factors to the Quality of Life in Multiple Sclerosis. Med Arch 2020, 74, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernstsson, O.; Tinghög, P.; Alexanderson, K.; Hillert, J.; Burström, K. The External Validity of Mapping MSIS-29 on EQ-5D Among Individuals With Multiple Sclerosis in Sweden. MDM Policy Pract 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nociti, V.; Losavio, F.A.; Gnoni, V.; et al. Sleep and fatigue in multiple sclerosis: A questionnaire-based, cross-sectional, cohort study. J Neurol Sci 2017, 372, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasiuk, J.; Kapica-Topczewska, K.; Czarnowska, A.; Chorąży, M.; Kochanowicz, J.; Kułakowska, A. Co-occurrence of Fatigue and Depression in People With Multiple Sclerosis: A Mini-Review. Front Neurol 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gois LCde, P.; Pimentel-Silva, L.R.; Damasceno, B.P.; Damasceno, A. Associations between cognitive and clinical disability across MS subtypes: The role of the underlying brain damage. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2021, 48, 102701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliore, S.; Ghazaryan, A.; Simonelli, I.; et al. Cognitive Impairment in Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis Patients with Very Mild Clinical Disability. Behavioural Neurology 2017, 2017, 7404289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Højsgaard Chow, H.; Schreiber, K.; Magyari, M.; et al. Progressive multiple sclerosis, cognitive function, and quality of life. Brain Behav 2018, 8, e00875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portaccio, E.; Magyari, M.; Havrdova, EK.; et al. Multiple sclerosis: emerging epidemiological trends and redefining the clinical course. The Lancet Regional Health - Europe 2024, 44, 100977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeni, K.; Tulek, Z.; Ozer, A.; Terzi, M. The effect of fatigue, sleep quality and depression on quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis: A serial mediation model. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2025, 93, 106211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, A.; Ebrahimian, A.; Sadigh-Eteghad, S.; Talebi, M.; Naseri, A. Sleep quality in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis based on Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2025, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foschi, M.; Rizzo, G.; Liguori, R.; et al. Sleep-related disorders and their relationship with MRI findings in multiple sclerosis. Sleep Med 2019, 56, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braley, T.J.; Boudreau, E.A. Sleep disorders in multiple sclerosis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2016, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Strijbis, E.M.M.; Repovic, P.; Mostert, J.; et al. The MSIS-29 and SF-36 as outcomes in secondary progressive MS trials. Multiple Sclerosis Journal 2022, 28, 1606–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, D.H. Biomarkers and Surrogate Outcomes in Neurodegenerative Disease: Lessons from Multiple Sclerosis. NeuroRx 2004, 1, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patten, S.B.; Marrie, R.A.; Carta, M.G. Depression in multiple sclerosis. International Review of Psychiatry 2017, 29, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparasci, D.; Gobbi, C.; Castelnovo, A.; et al. Fatigue, sleepiness and depression in multiple sclerosis: defining the overlaps for a better phenotyping. J Neurol 2022, 269, 4961–4971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardo, G.; Coates, S.; Okuda, D.T. Outcome measures assisting treatment optimization in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2021, 269, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | F (N, p%) | M (N, p%) | EDSS (mean, min-max) | |

| Total | 112 | 77 (68.7%) |

35 (31.3%) |

3.339 (0-7.0) |

|

Average date (mim-max) |

38.11 (16-60) |

40.16 (18-60) |

33.60 (16-55) |

|

| Relapsing forms group | 87 (77.7%) |

62 (71.3%) |

25 (28.7%) |

2.609 (0-6.0) |

| Progressive forms group | 25 (22.3%) |

15 (60%) |

10 (40%) |

5.880 (3.0-7.0) |

|

Group 1 Relapsing forms |

Group 2 Progressive forms |

p value (95% confidence interval) | ||

| Total N | 112 | 87 | 25 | |

|

SDMT (mean) PASAT (mean) MoCA (mean) MMSE (mean) |

38.25 (2-65) 43.32 (8-60) 23.62 (5-30) 27.96 (16-30) |

41.61 46.05 24.67 28.44 |

25.52 33.84 19.96 26.28 |

<0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.004 |

|

MSIS 29 (mean) MSNQ (mean) EQ-5D index (mean) EQ VAS (mean) |

59.67 15.89 2.32 71.04 |

51.91 13.92 1.69 76.21 |

86.24 22.68 4.48 53.24 |

<0.001 0.009 <0.001 <0.001 |

| SDMT |

PASAT (60) |

MoCA (30) |

MMSE (30) |

||

|

EDSS |

p | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| r | -0,587 | -0.466 | -0.390 | -0.400 |

| MSNQ (60) | EQ-5D index (score) | EQ (VAS score) | ||

|

MSIS – 29 (145) |

p | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| r | 0.622 | 0.825 | -0.774 |

| SDMT | PASAT (60) | MoCA (30) | MMSE (30) | EDSS |

9HPT DH |

9HPT NDH |

T25FW | |||

|

MSIS – 29 (145) |

p | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | |

| r | -0.544 | -0.520 | -0.314 | -0.491 | 0.686 | 0.579 | 0.610 | 0.547 | ||

|

EQ-5D index (score) |

p | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | |

| r | -0.574 | -0.524 | -0.375 | -0.511 | 0.683 | 0.593 | 0.589 | 0.526 | ||

|

EQ (VAS score) |

p | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | |

| r | 0.524 | 0.471 | 0.336 | 0.402 | -0.683 | -0.518 | -0.542 | -0.515 |

||

| SDMT |

PASAT (60) |

MMSE (30) |

MoCA (30) |

|||

|

1 |

EDSS |

p | 0.0001 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.053 |

| r | -0.488 | -0.361 | -0.294 | -0.208 | ||

|

2 |

EDSS |

p | 0.491 | 0.012 | 0.035 | 0.061 |

| r | -0.151 | -0.492 | -0.422 | -0.380 |

| SDMT |

PASAT (60) |

MoCA (30) |

MMSE (30) |

EDSS |

9HPT DH |

9HPT NDH |

T25FW | |||

|

1 |

MSIS-29 (145) | p | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.173 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| r | -0.496 | -0.464 | -0.148 | -0.485 | -0.583 | 0.423 | 0.500 | 0.492 | ||

| EQ-5D index (score) | p | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.056 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | |

| r | -0.476 | -0.427 | -0.207 | -0.455 | 0.528 | 0.443 | 0.431 | 0.462 | ||

| EQ VAS (score) | p | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.086 | 0.003 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | |

| r | 0.488 | 0.380 | 0.186 | 0.312 | -0.602 | -0.408 | -0.419 | -0.499 | ||

|

2 |

MSIS – 29 (145) |

P | 0.587 | 0.194 | 0.449 | 0.258 | 0.003 | 0.202 | 0.087 | 0.108 |

| r | -0.122 | -0.269 | -0.159 | -0.235 | 0.576 | 0.264 | 0.349 | 0.391 | ||

|

ED-5D (score) |

p | 0.186 | 0.086 | 0.087 | 0.050 | 0.002 | 0.089 | 0.029 | 0.519 | |

| r | -0.286 | -0.350 | -0.349 | -0.397 | 0.595 | 0.347 | 0.438 | 0.163 | ||

|

EQ VAS (score) |

p | 0.951 | 0.221 | 0.307 | 0.209 | 0.092 | 0.969 | 0.317 | 0.763 | |

| r | -0.014 | 0.254 | 0.213 | 0.260 | -0.344 | 0.008 | -0.208 | -0.076 |

| SDMT |

PASAT (60) |

MoCA (30) |

MMSE (30) |

EDSS |

9HPT DH |

9HPT NDH |

T25FW | MFIS p | MFIS c | MFIS t | BDI | ESS | PSQI | ||

| MSIS-29 (145) | p | 0.715 | 0.004 | 0.815 | 0.077 | 0.032 | 0.067 | <0.001 | 0.064 | 0.001 | 0.0003 | 0.0002 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.005 |

| r | -0.071 | -0.517 | -0.045 | -0.333 | 0.400 | 0.345 | 0.631 | 0.348 | 0.578 | 0.619 | 0.625 | 0.725 | 0.297 | 0.505 | |

| EQ 5D (score) | p | 0.378 | 0.009 | 0.301 | 0.146 | 0.012 | 0.093 | 0.002 | 0.021 | 0.045 | 0.013 | 0.014 | 0.005 | 0.652 | 0.147 |

| r | -0.170 | -0.474 | -0.199 | -0.277 | 0.458 | 0.318 | 0.550 | 0.426 | 0.376 | 0.454 | 0.415 | 0.504 | 0.078 | 0.276 | |

| EQ VAS (score) | p | 0.180 | 0.069 | 0.010 | <0.001 | 0.008 | 0.179 | 0.005 | 0.104 | 0.002 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.029 | 0.115 | 0.049 |

| r | 0.256 | 0.342 | 0.472 | 0.629 | -0.482 | -0.408 | -0.504 | -0.308 | -0.556 | -0.690 | -0.663 | -0.406 | -0.22 | -0.36 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).