4. Key Performance Indicators for SLB Management Within the PDCA Framework

The effective integration of SLBs into grid applications requires a structured approach to monitoring and evaluation throughout their lifecycle. KPIs act as measurable metrics that translate complex technical, economic, and environmental aspects into actionable insights, supporting adaptive management under the PDCA framework [

75,

76].

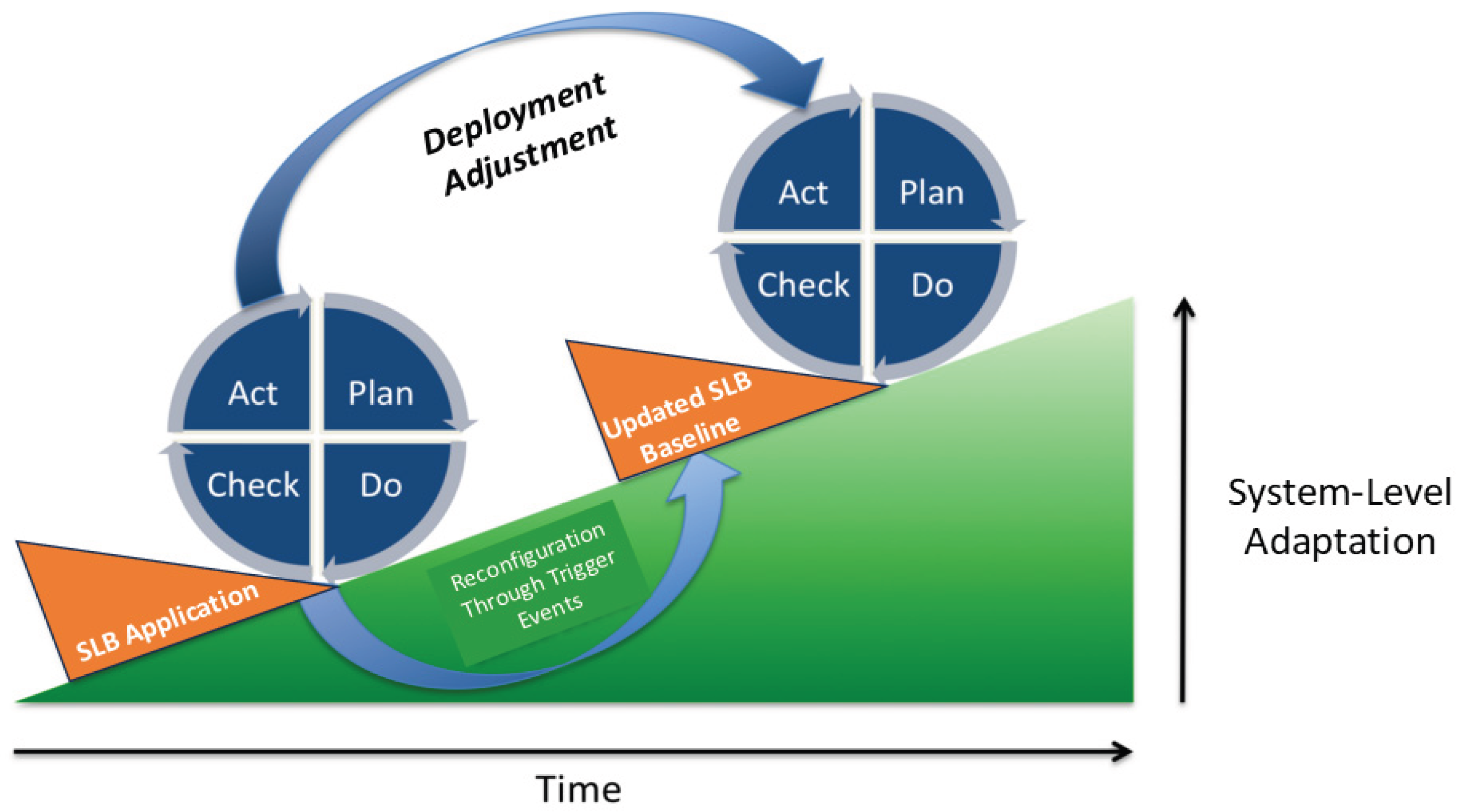

While several studies have proposed KPIs for first-life batteries, there is a research gap in systematically applying KPIs to second-life batteries within operational management frameworks, particularly under circular economy and resilience objectives. This section aims to address this gap by presenting a comprehensive KPI catalog aligned with the PDCA cycle, allowing operators to track, analyze, and optimize SLB deployments dynamically. The KPIs were selected and structured based on analytical review and adapted by the author to reflect second-life battery characteristics.

- (a)

Scenario Definitions and Assumptions

To illustrate the implementation of the proposed PDCA-based framework, three representative deployment scenarios for second-life batteries (SLBs) are defined. These scenarios reflect distinct operational roles within power systems and require tailored KPI configurations and trigger conditions to support adaptive lifecycle management:

Scenario 1: HV Backup. SLBs are deployed as reserve power sources at medium-voltage substations, providing support during outages and unplanned events. Performance is characterized by infrequent deep discharges with long idle periods. The primary KPIs include State of Health (SoH) and Round-Trip Efficiency (RTE). Planning targets are SoH > 70% and RTE > 85%. Real-time monitoring ensures that, when SoH falls below 65% (trigger threshold), the SLB is reallocated to a less demanding application to extend residual value and defer disposal.

Scenario 2: RES Smoothing. In this case, SLBs are integrated to mitigate fluctuations in photovoltaic (PV) and wind power output, absorbing surplus generation and smoothing short-term variability. Operational patterns involve moderate cycling with medium depth-of-discharge (DoD). Key KPIs include DoD range (target 60–70%) and the Integral Degradation Index (IDI). When the IDI exceeds 0.85 (trigger threshold), the battery is reassigned to low-cycling roles such as frequency regulation or strategic reserve to preserve functionality and mitigate further degradation.

Scenario 3: Frequency Regulation. Here, SLBs provide rapid-response ancillary services, balancing short-term frequency deviations through intensive cycling. This scenario places greater stress on battery lifespan, requiring close tracking of cost-effectiveness. Economic KPIs, such as Levelized Cost of Storage (LCOS) and Return on Investment (ROI), guide performance evaluation. A dynamic LCOS threshold (180–200 USD/MWh) serves as a trigger for re-evaluation. If exceeded, the SLB is shifted to services with lower cycling intensity or retired if no viable use remains.

All scenarios are designed for mid-voltage grid applications and assume partial battery degradation at the time of integration. The planning horizon for each use case spans 5–10 years. Load profiles are derived from historical public data and synthetic reconstructions based on Ukrainian modeling studies [

77,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85], while renewable generation variability is modeled using international benchmarks, including IEA-PVPS. The trigger-based mechanism in each scenario supports responsive control aligned with PDCA phases, maximizing the operational utility and sustainability of second-life battery systems.

- (b)

Technical KPIs for SLB Integration

Selection of technical performance indicators is critical for ensuring the operational readiness and longevity of second-life batteries (SLBs) within energy systems [

86,

87,

88,

89,

90]. Metrics such as RTE, DoD, SoH, and IDI provide quantifiable insights into the core functional capabilities of SLBs under dynamic operational conditions [

91,

92,

93,

94]. These KPIs help in evaluating conversion efficiency, usable capacity, degradation progression, and charge/discharge behavior, aligning operational control with grid support requirements and degradation mitigation strategies [

95,

96,

97,

98].

SOH is a key indicator that characterizes the current performance of a battery relative to its initial condition [

28,

29,

30]. It is commonly evaluated from two main perspectives: the remaining capacity and the internal resistance of the battery.

When calculated based on remaining capacity, SOH is expressed as [

28]:

When evaluated based on internal resistance, SOH is defined as [

27]:

In these formulas, Ccurrent and Cinitial represent the battery’s current and nominal capacity as specified by the manufacturer. Rmax, Rcurrent, and Rinitial correspond to the internal resistance at the beginning of life, current state, and end-of-life threshold, respectively.

To capture the complex degradation dynamics of second-life batteries (SLBs), including both deterministic and stochastic aging effects, this study employs the Integral Degradation Index (IDI) developed by the author in previous work [

34]. This composite indicator accounts for capacity loss from calendar aging, cyclic aging, and random operational variability such as temperature fluctuations, variable DoD, SOC swings, and inconsistent C-rate conditions. The IDI formula integrates the deterministic degradation models with a stochastic uncertainty term:

where

) – loss of capacity due to calendar aging;

– reaction rate constant;

– activation energy; R – universal gas constant; T is the temperature; t is the time; f(SOC) is a function that describes the dependence on the SOC;

– loss of capacity due to cyclic aging;

– reaction rate constant for cyclic aging; DOD – depth of discharge; Crate – charging/discharging speed; α and β – model parameters;

– the number of charge/discharge cycle;

– total loss of battery capacity, taking into account the factors of calendar and cyclic aging;

(t) – taking into account the uncertainty of the state/behaviour of secondary batteries under operating conditions;

T,

are random variables, respectively, temperature, state of charge, depth of discharge, charge/discharge rate with a certain distribution (e.g., normal), derivatives represent

the sensitivity of the battery capacity to changes in each of these parameters.

The Remaining Useful Life (RUL) of a battery denotes the projected operational duration remaining before the battery's state of health (SOH) declines to a predefined critical threshold. Provided the initial SOH at the beginning of second-life application and a critical SOH limit for acceptable performance, the RUL can be estimated as:

where

– the initial state of health of the battery when it starts its secondary use;

– the critical state of health at which the battery is considered no longer effective for the intended application,

– the integral degradation index, which represents the rate of degradation per unit time.

This index enables more realistic modeling of SLB behavior in operational environments and improves accuracy in SOH and RUL predictions, making it particularly suitable for adaptive control and trigger-based decision-making within the PDCA framework. Cross-validation was performed using synthetic datasets reflecting three representative SLB aging scenarios. The results were compared to degradation patterns reported in [

34].

In addition, it is essential to account for the reliability indicator R(t), which reflects the actual ability of the battery to operate without interruptions during its second-life application. This indicator is defined as the ratio of uninterrupted operating time to the total operating time:

Its value decreases in the presence of frequent faults, shutdowns, or failure events, and it is critically important for assessing the long-term effectiveness of second-life battery applications in power systems.

Integrating these technical KPIs within the PDCA cycle enables systematic monitoring and adaptive management, providing the data foundation for trigger-based decision-making, scenario planning, and lifecycle extension strategies under the principles of the circular economy [

99,

100].

Table 3 summarizes the selected technical KPIs relevant for SLB deployment and their connection to PDCA phases.

In practice, these technical KPIs guide operational decisions across different SLB deployment scenarios [

90,

91]. For instance, in frequency regulation services, maintaining an RTE above 85% and SoH above 70% ensures rapid and reliable system response while preserving SLB health [

101]. In renewable energy smoothing applications, DoD levels are strategically managed to balance energy flexibility and degradation rates, while the IDI can be monitored to assess the combined effects of cyclic and calendar aging [

102,

103].

By integrating the selected technical KPIs into the PDCA cycle, operators can implement a structured and adaptive approach to SLB management. This enables ongoing monitoring, threshold-based trigger control, and scenario-specific planning, aligning operational strategies with circular economy goals and performance sustainability [

104,

105,

106,

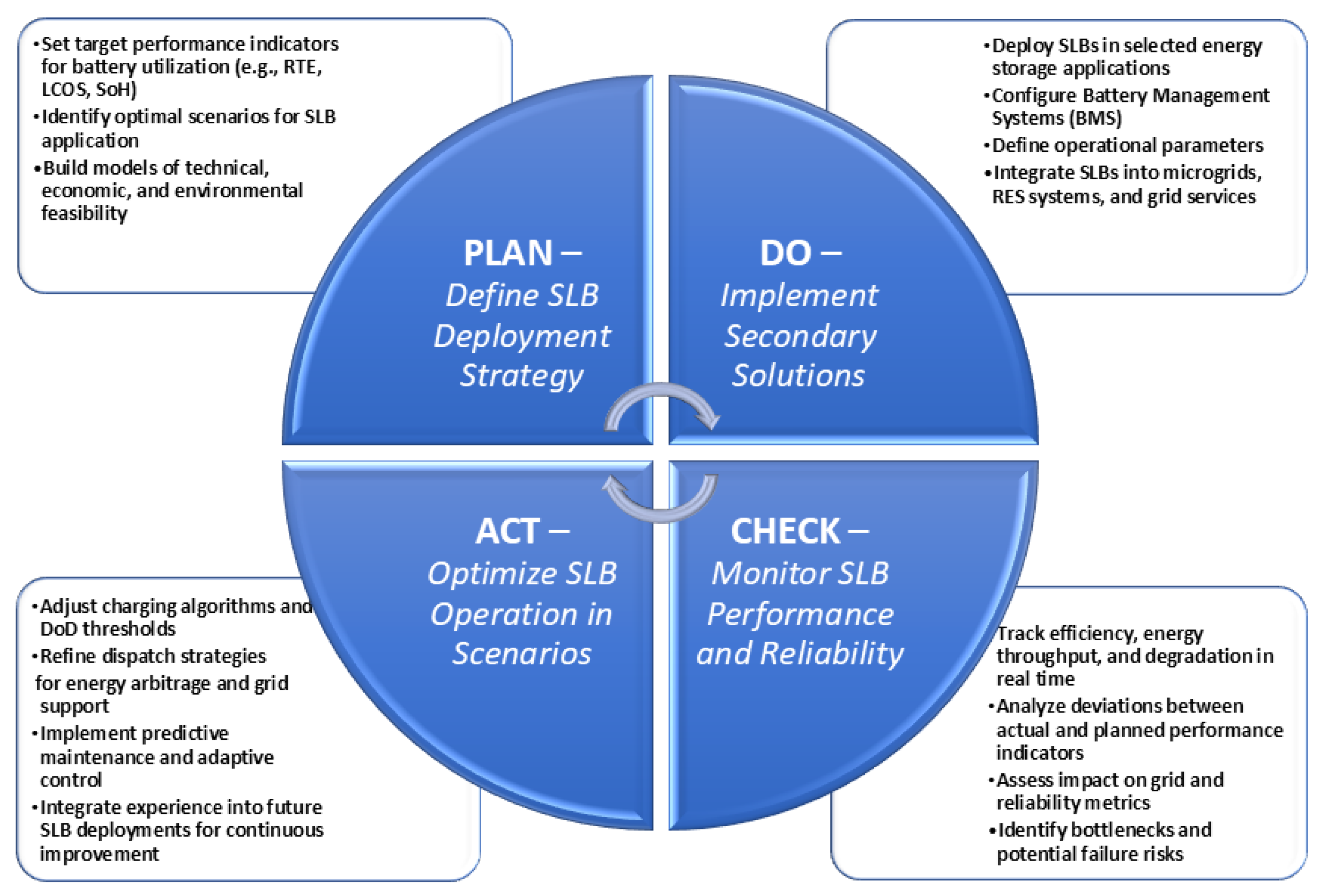

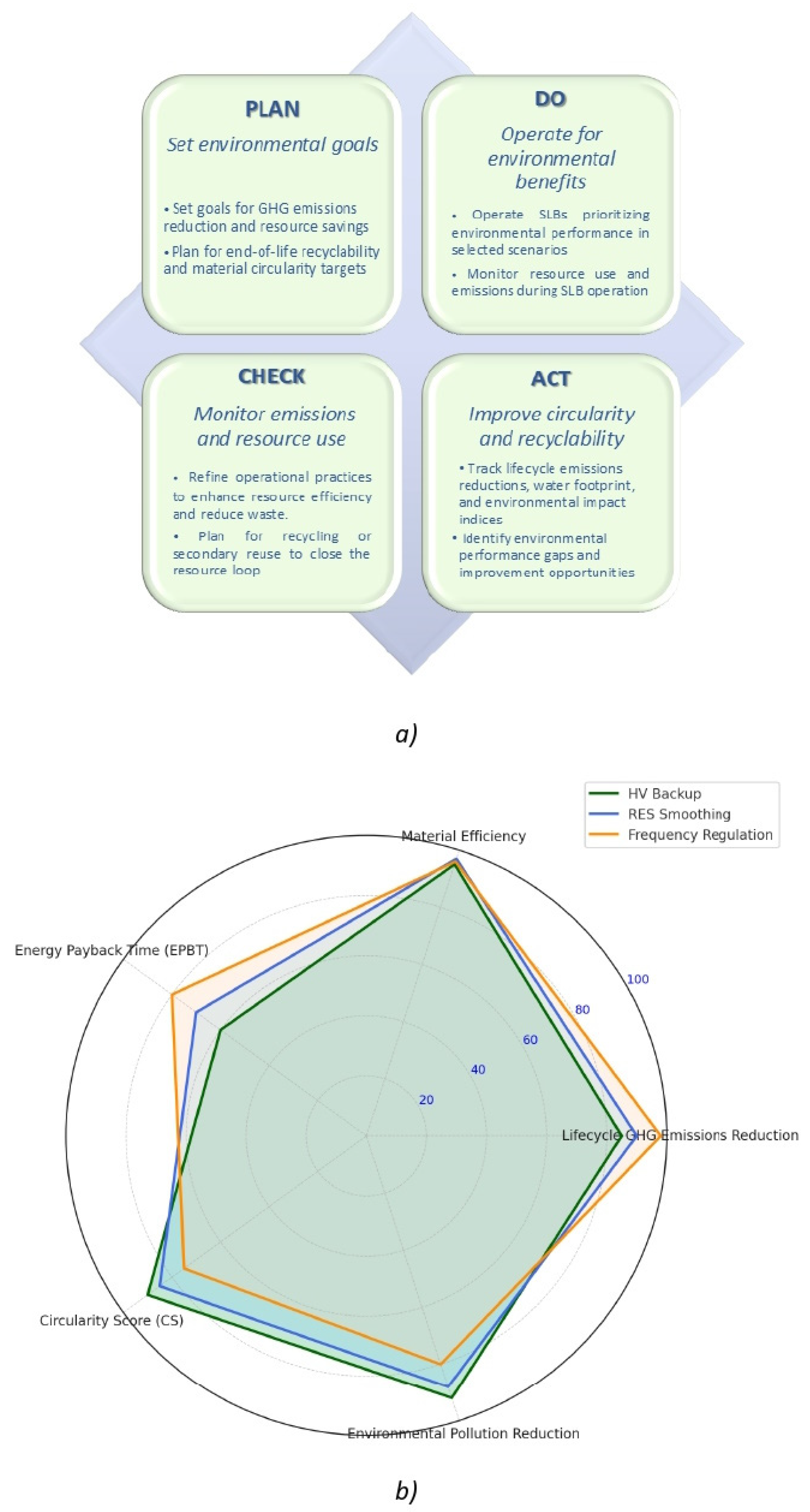

107]. The diagram in

Figure 7a illustrates how key technical indicators (such as RTE, SoH, DoD, and IDI) are embedded within each PDCA phase to support continuous performance improvement and degradation mitigation. To visualize how these indicators manifest in different system roles,

Figure 7b presents a comparative radar chart of three SLB deployment scenarios — HV Backup, RES Smoothing, and Frequency Regulation — highlighting scenario-specific KPI profiles and trade-offs.

- (c)

Economic KPIs for SLB Deployment

Economic feasibility is a critical dimension of SLB deployment, influencing investment decisions, operational strategies, and long-term project viability [

107,

108]. Economic KPIs such as LCOS, Payback Period (PBP), Return on Investment (ROI), and Revenue Stacking Potential provide structured tools for evaluating the cost-effectiveness of SLB systems while aligning them with market and policy frameworks [

108,

109,

110]. These indicators allow for quantifying economic benefits, managing operational expenditures, and assessing profitability under various market conditions, including in residential, backup, and grid-support contexts [

109,

110,

111].

To quantify the financial viability of SLB deployment across scenarios, two key economic indicators are applied: ROI and LCOS.

LCOS reflects the total cost per unit of stored and delivered energy across the project lifetime:

where:

– capital expenditures in year

;

– operational and maintenance costs;

– delivered energy;

– discount rate;

– project lifetime.

These formulas allow for comparative financial assessment across applications such as backup power, microgrids, and renewable integration. As noted in prior work [

32,

33,

34], SLB deployment in RES smoothing shows ROI of 15–22%, while LCOS values vary strongly with utilization and degradation rate.

Incorporating economic KPIs within the PDCA cycle ensures that financial considerations are systematically monitored and integrated into adaptive decision-making, enabling project stakeholders to align operational control with profitability and circularity goals [

107,

112].

Table 4 summarizes the key economic KPIs relevant to SLB integration and their linkage to PDCA phases.

In application, these economic KPIs support scenario-specific financial optimization of SLB systems [

108,

109]. For example, in HV Backup scenarios, LCOS calculations can be used to compare SLB integration with alternative backup solutions, while PBP and ROI provide critical benchmarks for project viability under cost-constrained conditions [

107,

111]. In RES smoothing and frequency regulation scenarios, revenue stacking potential allows operators to leverage multiple income streams, improving economic performance and reducing reliance on a single service revenue [

109,

112].

Integrating economic KPIs into the PDCA cycle enables continuous assessment of project viability and profitability across SLB deployment scenarios [

107,

110,

111]. By embedding indicators such as LCOS, ROI, PBP, and Utilization Rate into financial planning and monitoring workflows, stakeholders can identify cost deviations, anticipate revenue fluctuations, and adjust strategies in response to market conditions.

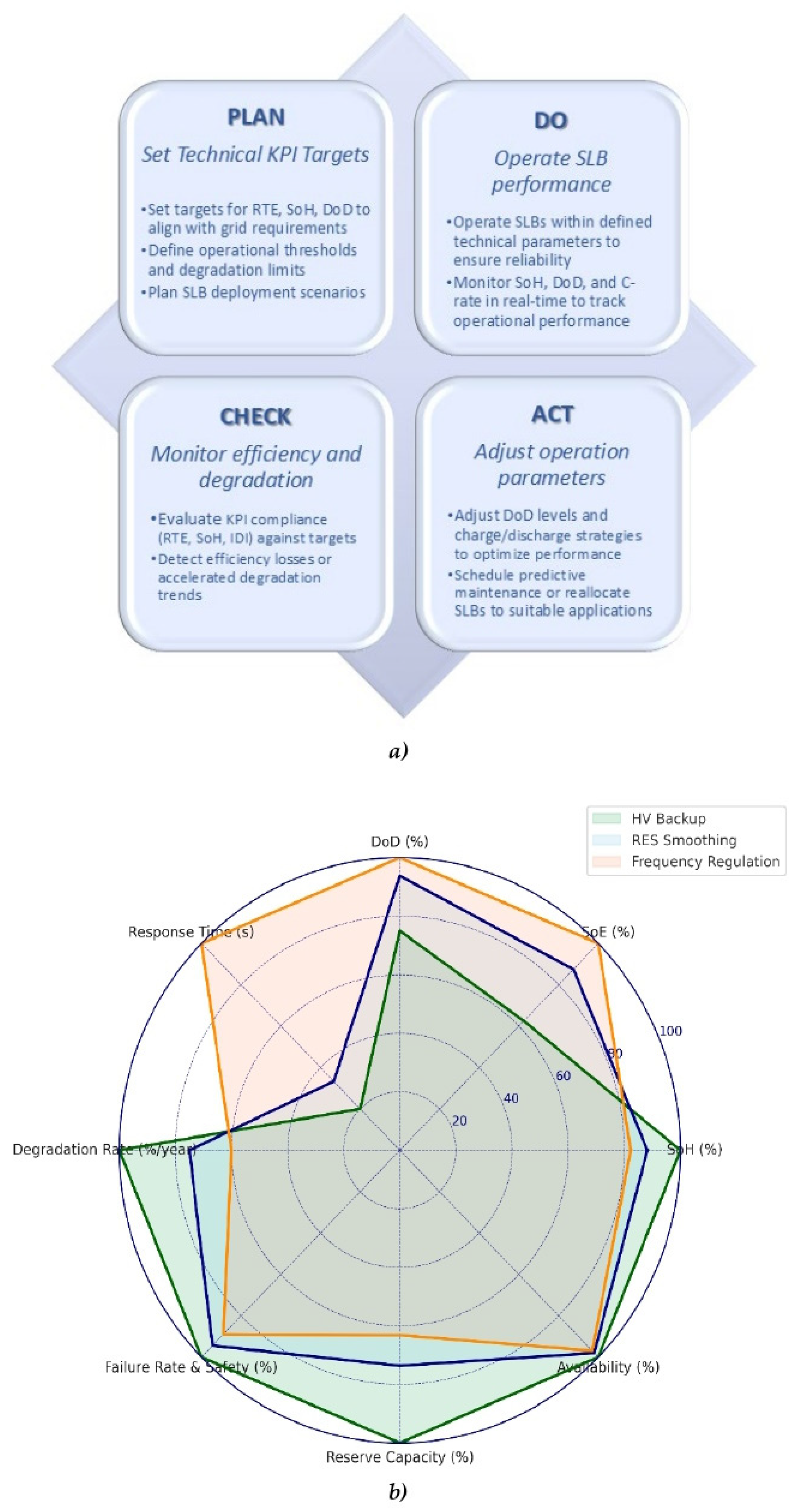

Figure 8a presents the economic dimension of the PDCA logic, illustrating how each phase contributes to financial control and optimization. To contextualize these indicators within specific system roles,

Figure 8b visualizes the economic KPI profiles of the three representative SLB scenarios — HV Backup, RES Smoothing, and Frequency Regulation. The radar chart highlights scenario-specific performance trade-offs, enabling comparative evaluation and scenario-driven financial strategy design.

- (d)

Environmental KPIs for Evaluation of SLB Sustainability

Environmental sustainability indicators are essential for evaluating the circularity potential and climate impact of SLB deployment in energy systems [

113,

114]. Metrics such as Lifecycle GHG Emissions Reduction, Resource Savings, and End-of-Life Recyclability Readiness quantify the environmental benefits of reusing batteries compared to first-life systems and conventional fossil-based alternatives [

115,

116,

117].

Environmental KPIs provide critical insight into the circular value of SLBs. For instance, carbon footprint reduction is expressed as:

where

and

represent lifecycle emissions for new and second-life battery production, respectively.

A 40 kWh SLB pack can save over 2,200 kg CO₂ compared to a new battery.

Material efficiency (ME), indicating energy return on material input, is given by:

where

represents useful output energy in second life, and

reflects embodied energy in raw materials.

Another indicator, Energy Payback Time (EPBT), reflects the time to recover the energy invested in SLB repurposing:

For typical SLB deployments, ≈ 0.1 years (≈1.2 months), significantly outperforming new LIBs.

Finally, the Circularity Score (CS

) is used for comparative circularity evaluation:

where

– the mass of components reused in the second-life battery application;

– the mass of components recyclable after the end of the second life;

– the total mass of materials in the battery.

This indicator reflects the proportion of materials that are either reused or returned into the production cycle, thus serving as a key metric for assessing circular economy performance, and for SLBs achieving scores up to 0.9 versus 0.6 for new batteries.

These KPIs align SLB operations with decarbonization pathways, material circularity, and regulatory sustainability targets [

118,

119]. Integrating environmental KPIs within the PDCA cycle enables real-time tracking of sustainability outcomes, allowing operational strategies to be adapted to enhance SLB contributions to circular economy goals while maintaining alignment with system performance and economic feasibility [

120,

121].

Table 5 summarizes key environmental KPIs applicable to SLB management and their placement within PDCA phases.

In practical deployment, these environmental KPIs guide sustainability-aligned operational management of SLBs [

113,

114]. For instance, in RES smoothing scenarios, monitoring lifecycle GHG reductions enables quantifying emissions savings achieved by displacing fossil-based peak plants, while resource savings metrics provide insights into the materials preserved through reuse instead of new battery production [

115,

116,

117,

118]. End-of-life recyclability readiness supports planning for circular re-entry of materials, closing the loop in battery resource cycles [

119,

120,

121]. Utilizing these KPIs within PDCA-based operations enables evidence-based scenario prioritization, allowing SLB operators to select and adjust use cases that maximize environmental benefits while sustaining system reliability and cost-effectiveness.

To enable environmentally sound integration of SLBs into energy systems, environmental KPIs must be operationalized within a structured management framework. The PDCA cycle provides such a structure, supporting scenario-specific sustainability goals, tracking real-time emissions and resource use, and informing end-of-life strategies.

Figure 9a outlines how environmental considerations are embedded into each PDCA phase — from planning circularity targets to acting on emissions trends and recyclability readiness. To assess how various SLB deployment scenarios contribute to sustainability goals,

Figure 9b presents a comparative radar chart of environmental KPIs across three application types: HV Backup, RES Smoothing, and Frequency Regulation. The chart highlights the environmental strengths and trade-offs of each use case, facilitating evidence-based decision-making aligned with decarbonization and circular economy objectives.

While technical, economic, and environmental KPIs each offer valuable insights into second-life battery (SLB) performance, none of them alone is sufficient for making informed deployment decisions. Technical indicators such as SoH, RTE, or IDI characterize the physical capability and health of the battery, but they do not reflect whether continued use is financially viable or environmentally justified. Conversely, a deployment scenario with favorable ROI or LCOS may involve rapid degradation or poor reliability, ultimately compromising system performance. Similarly, scenarios with strong environmental impact — such as carbon footprint reduction or circularity gains — may underperform economically or technically, limiting their practical relevance.

Each KPI dimension becomes more or less critical at different stages of the SLB lifecycle. In the initial screening and repurposing phase, technical KPIs dominate decision-making to ensure safe and viable operation. During scenario matching and early deployment, economic KPIs such as LCOS and ROI take precedence to confirm financial feasibility. As the battery progresses through its operational phase, degradation trends and usage profiles shift the emphasis toward trigger-based technical monitoring. Toward the end of life, environmental and circularity KPIs become crucial in guiding reallocation, recycling, or disposal planning.

This evolving relevance of KPIs necessitates a composite, dynamic evaluation framework that allows weighting, tracking, and balancing of competing priorities. Integrating these KPIs within the PDCA management cycle enables scenario-specific optimization, supports lifecycle governance, and ensures alignment with circular economy principles.

- (e)

Composite Scenario-Based KPIs Visualization

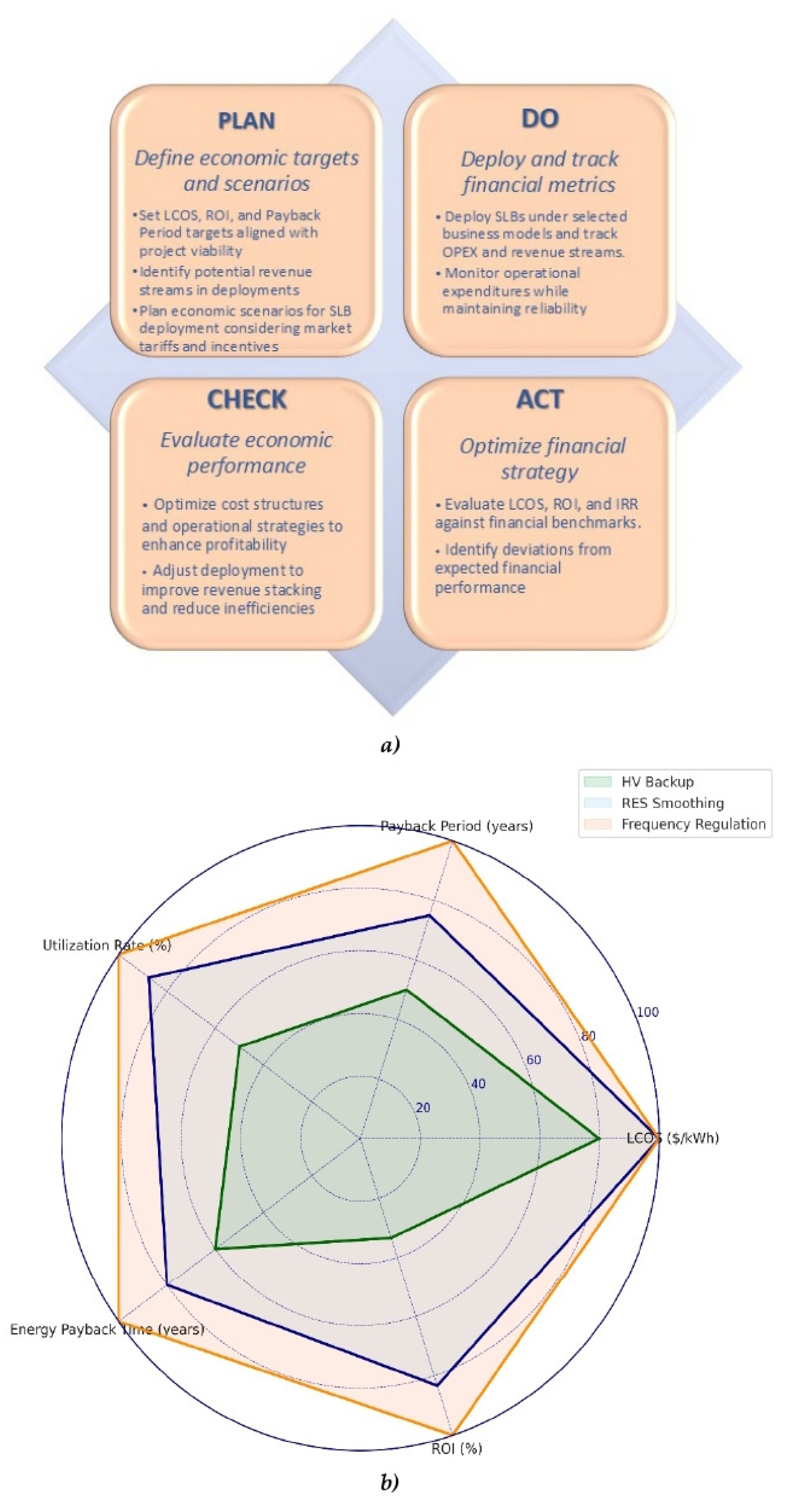

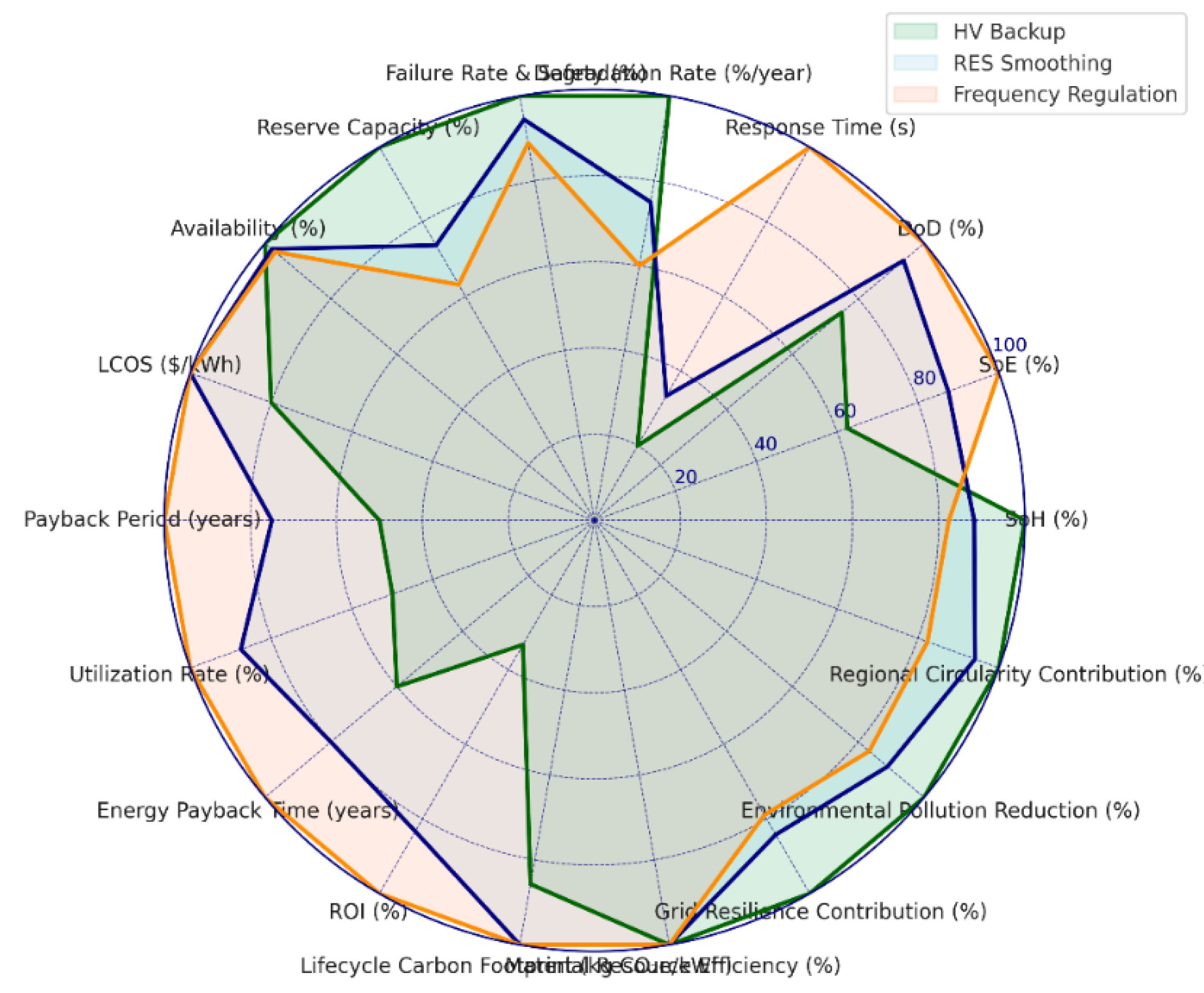

To support balanced and adaptive deployment of SLBs, a composite radar-based visualization approach is employed. Unlike separate assessments of technical, economic, and environmental indicators, this integrated view enables holistic comparison of SLB performance across representative operational scenarios — high-voltage backup, RES smoothing, and frequency regulation.

Figure 10 presents a composite radar chart that consolidates normalized KPI values across all three dimensions, offering a multidimensional overview of scenario-specific strengths, weaknesses, and trade-offs. This includes metrics such as round-trip efficiency, SOH, degradation rate, LCOS, payback period, lifecycle carbon footprint, material resource efficiency, and more — each normalized to a 0–100 scale to allow joint visualization.

The chart reveals that Frequency regulation delivers strong technical responsiveness but faces challenges from accelerated degradation and increased LCOS, reflecting intensive cycling stress. HV backup excels in safety, availability, and reserve capacity, with moderate financial returns and limited cycling intensity — making it suitable for longevity-oriented roles. RES smoothing offers the most balanced profile, with stable performance across environmental and economic KPIs, positioning it as a versatile option in grid-interactive applications.

This visual comparison directly supports PDCA-based SLB management by making trade-offs explicit and scenario selection more transparent. It enables stakeholders to align deployment strategies with system priorities — whether optimizing for resilience, economic return, or circularity gains.

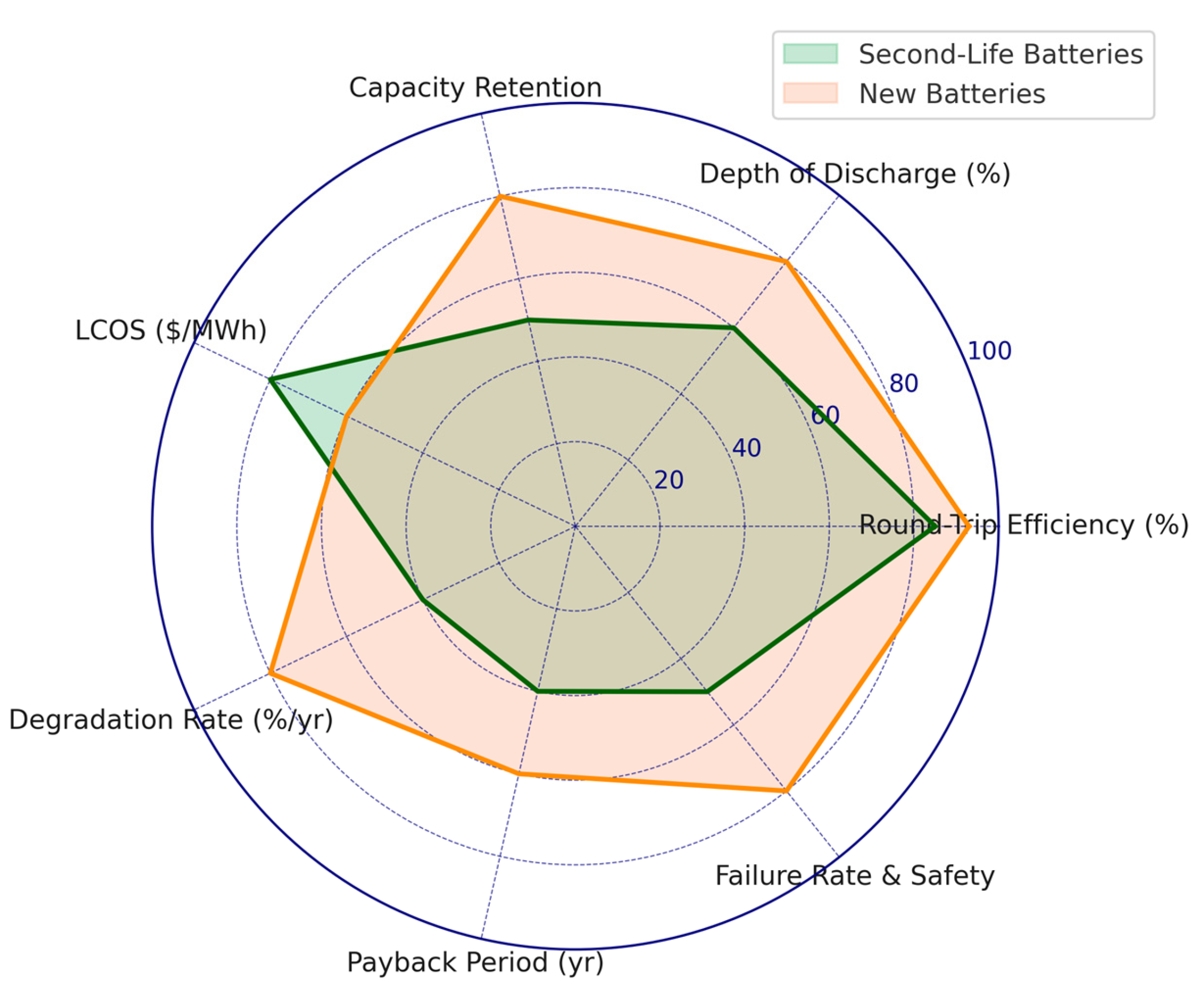

In addition to comparing SLB scenarios,

Figure 11 presents a reference radar chart contrasting SLBs and new LIBs across selected KPIs. While SLBs demonstrate clear advantages in lower LCOS and circularity benefits, they underperform in capacity retention, depth of discharge, and degradation rate, emphasizing the need for context-specific planning and lifecycle-aware operation.

Together,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 anchor the KPI framework in practical insights, enabling adaptive, evidence-based SLB deployment aligned with performance targets and sustainability goals.

This scenario-based KPI analysis supports system planners, operators, and researchers in evaluating SLB deployment strategies, enabling informed decision-making on scenario prioritization while managing trade-offs between operational performance, financial considerations, and sustainability objectives within adaptive PDCA-based management frameworks.

Beyond scenario-based comparisons, KPI roles evolve dynamically across the SLB lifecycle — from early-stage screening to portfolio-level optimization.

Table 6 summarizes this evolution by mapping KPI functions to distinct integration phases and strategic decisions. This complements radar-based evaluations with a temporal logic, clarifying not only what to monitor but also when and why it matters for SLB integration.

Integrating KPIs within the PDCA framework enables systematic continuous improvement in SLB operation: Plan (define KPI targets), Do (deploy with monitoring), Check (track deviations), Act (adjust operational strategies). This structured feedback loop aligns SLB performance with grid requirements, economic objectives, and sustainability goals.

- (f)

Trigger-Based Control Logic

To operationalize the PDCA-based integration of second-life batteries (SLBs), a trigger-based control mechanism is introduced, linking key performance indicators (KPIs) to adaptive decision rules. This approach transforms KPI monitoring into actionable logic, enabling timely interventions in response to technical degradation, economic inefficiencies, or environmental deviations. By defining threshold values and corresponding actions, SLB deployment strategies can dynamically evolve while maintaining alignment with system-level objectives, circular economy principles, and reliability standards.

Within this logic, each KPI serves as a sentinel for a specific type of risk or opportunity. When thresholds are breached, corrective or preventive actions are triggered in the Do or Act phases of the PDCA cycle, ensuring that performance deterioration does not become irreversible.

Representative examples of such KPI-driven triggers include:

SoH Trigger: If the state of health (SoH) drops below 65%, the SLB is reassigned from high-intensity applications (e.g., frequency regulation) to low-stress roles (e.g., backup), thereby extending usable life and deferring replacement.

IDI Trigger: When the Integral Degradation Index (IDI) exceeds 0.85, indicating cumulative calendar, cyclic, and stochastic wear, the battery’s operational load is reduced or it is prepared for secondary reassignment or recycling.

RTE Trigger: A decline in round-trip efficiency (RTE) below 75% prompts adjustments in depth-of-discharge (DoD) or cycling frequency to reduce further degradation.

LCOS Trigger: An increase in the LCOS beyond predefined viability thresholds initiates strategic reassessment, including possible changes to use-case scenarios or business models.

Environmental Triggers: If lifecycle GHG reduction falls below 25% or resource savings become negligible, environmental performance is flagged for review, triggering redesign or exit strategies.

Table 7 provides a consolidated matrix of threshold-based triggers and the corresponding operational responses, structured in alignment with PDCA phases. It serves as a practical reference for scenario-specific SLB management.

This trigger-based logic empowers SLB operators to implement data-driven, scenario-aware interventions, ensuring performance stability, economic feasibility, and sustainability. By embedding KPI thresholds directly into the PDCA cycle, this approach facilitates predictive governance, reduces degradation risks, and supports lifecycle extension — reinforcing the broader goals of circular energy systems. The trigger-based control structure reflects a custom event-driven logic devised specifically for adaptive SLB dispatch under scenario variability.

- (g)

KPI-Triggered Operational Model

To operationalize trigger-based SLB management within the PDCA cycle, we propose a formalized control model in which real-time values of selected KPIs determine appropriate system-level actions. These actions aim to maximize performance while minimizing degradation, economic loss, or sustainability compromise. The model builds upon the KPI-action matrix and embeds decision logic into an adaptive control rule applicable to SLB deployment.

Let the following KPIs be monitored at time t: SOH(t) – state of health, LCOS(t) – levelized cost of storage, U(t) – utilization rate, R(t) – reliability indicator.

We also define key thresholds and acceptable minimum values: TSOH – SOH threshold, LLCOS – LCOS threshold, Umin, Rmin – minimum acceptable values for utilization and reliability respectively.

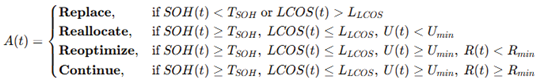

Then the control action A(t) is selected according to the rule:

This logic yields four distinct operational strategies:

Replace: If technical or economic thresholds are violated, the SLB is retired or moved to end-of-life processing.

Reallocate: If utilization is too low despite acceptable SOH and LCOS, the SLB is reassigned to a more suitable use-case.

Reoptimize: If reliability drops, operational parameters are adjusted (e.g., dispatch frequency, DoD) to mitigate further risk.

Continue: If all KPIs remain within target bounds, the current scenario is maintained.

Each action is mapped to PDCA phases:

Plan: Define KPI targets and thresholds based on scenario evaluation.

Do: Deploy batteries and begin monitoring.

Check: Evaluate deviations using real-time KPI inputs.

Act: Apply A(t) based on logic rule to modify or continue the operational strategy.

This model ensures that SLB deployment remains data-driven, dynamically adaptive, and aligned with both technical feasibility and circular economy objectives. Moreover, it enables the formalization of transition logic between deployment roles, bridging operational monitoring with actionable system-level responses.

This study relies on simulated data rather than operational logs. The degradation model assumes uniform calendar and cyclic decay, which may not capture real-world thermal or charging variability. The KPI weights are expert-based and may vary across systems. Scalability and interoperability with existing dispatch platforms require further verification.

- (h)

Future Research: Multi-model Framework for SLB Deployment

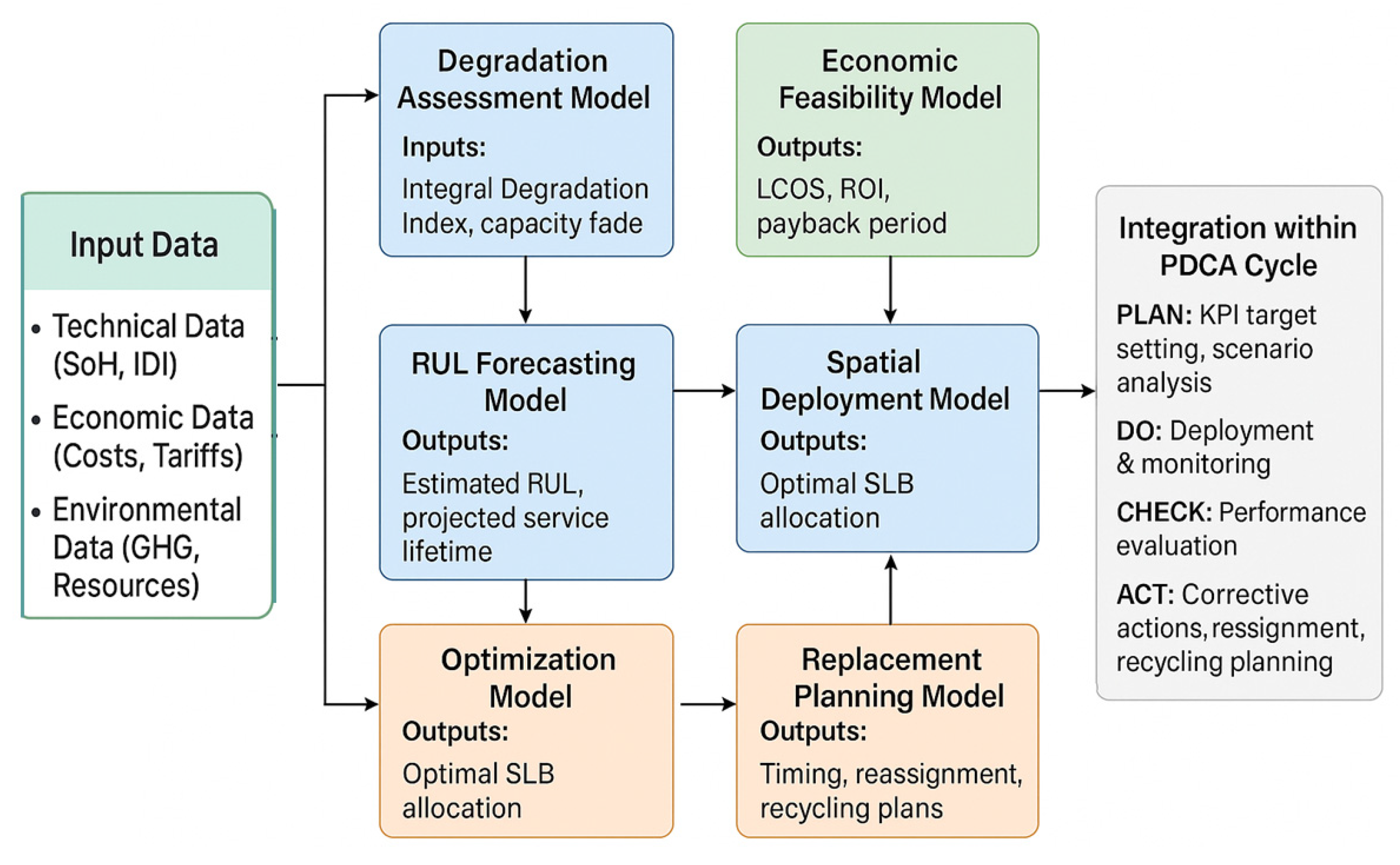

Building on the presented KPI-based control approach, future research will focus on the development of an integrated multi-model framework for second-life battery (SLB) deployment. This framework will support comprehensive decision-making throughout the battery lifecycle by combining technical performance monitoring, economic feasibility analysis, spatial allocation, operational optimization, and replacement planning — all aligned with the PDCA cycle. Such an approach aims to enhance the efficiency and reliability of SLB integration into energy systems under diverse grid and microgrid scenarios.

In the PLAN phase, target KPIs are defined across technical (SoH, SoE, DoD, IDI), economic (LCOS, ROI, PBP), and environmental (lifecycle carbon footprint, material resource efficiency) dimensions. Degradation and RUL models are employed to assess the technical suitability of SLBs for intended applications. Economic feasibility is evaluated using LCOS and financial performance indicators, while scenario-based planning identifies optimal use cases considering system flexibility and resilience requirements.

In the DO phase, SLBs are deployed within selected applications such as renewable energy integration, backup power, or frequency regulation. Operational parameters are configured using cluster-based deployment and optimization models, ensuring efficient system integration while monitoring degradation trends through the IDI and SoH metrics.

In the CHECK phase, real-time monitoring of KPIs allows comparison of actual performance with planned targets. Trigger conditions, based on thresholds for degradation, utilization rates, and economic parameters, initiate system checks for operational adjustments, maintenance scheduling, or reconfiguration of deployment scenarios.

In the ACT phase, corrective actions are implemented to optimize SLB operation, including adjusting charging/discharging strategies, transitioning to alternative operational scenarios, or planning replacements. Feedback from operational performance informs iterative improvements in future SLB deployment strategies.

To operationalize the KPI-PDCA framework, a set of interconnected models supports scenario-based deployment and adaptive management of SLBs within energy systems.

Table 8 summarizes these models, detailing their inputs, outputs, applied methods, and integration within the PDCA cycle to align SLB deployment with circular economy goals and system flexibility requirements.

The models presented in

Table 8 function as an integrated system supporting the systematic deployment and adaptive management of SLBs within the KPI-PDCA framework. By combining degradation analysis, lifetime forecasting, economic feasibility, spatial and operational optimization, and replacement planning, these models enable informed decision-making across planning, operation, monitoring, and corrective phases. Trigger-based control logic is embedded within this structure, using KPI thresholds to initiate adjustments in dispatch strategies, scenario allocations, or replacement timing as SLBs progress through different stages of use. This multi-model approach ensures that SLB deployment aligns with circular economy principles by extending asset lifecycles, improving resource efficiency, and reducing waste while maintaining operational flexibility and economic viability within energy systems.

Figure 12 visually summarizes this integrated multi-model framework, illustrating how the individual models interact within the PDCA cycle to support scenario-based SLB deployment and adaptive management.

Together, these models enable comprehensive scenario-based evaluation and operational management of SLBs within energy systems, supporting decision-making aligned with circular economy principles, system flexibility needs, and sustainability objectives.

In Ukraine, active research is underway to develop advanced models supporting SLB deployment within energy systems, covering frequency regulation applications, distributed generation integration, and scenario-based optimization under technological and environmental constraints [

122,

123,

124,

125,

126,

127,

128,

129,

130,

131,

132,

133]. These models address both the technical dynamics of SLB operation and the economic-environmental dimensions of system-level deployment planning, aligning with the broader goals of grid flexibility and low-carbon transition pathways [

124,

125,

126,

127]. Notably, author has contributed to this field through the development of integrated degradation modeling, cluster-based SLB allocation frameworks, and circular economy-oriented operational scenarios for the Ukrainian power system [

17,

18,

19], [

34], [

117]. Future work will focus on calibrating these models using real-world operational and degradation datasets to refine scenario-based analyses and trigger thresholds. Additionally, the integrated use of these models offers the potential for developing digital twin systems for SLB management, enabling predictive diagnostics, adaptive dispatch strategies, and continuous optimization within energy systems.

.

.