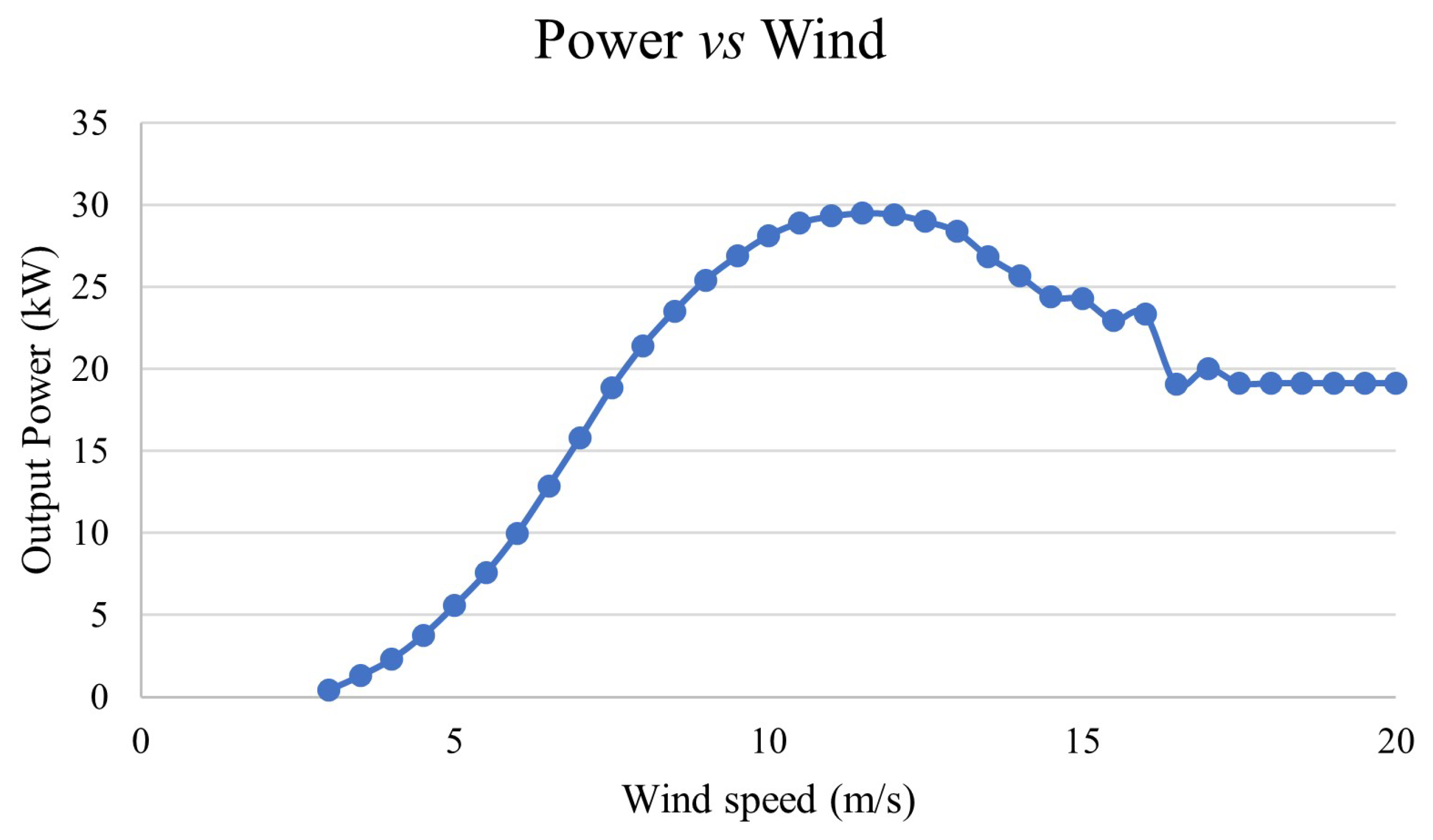

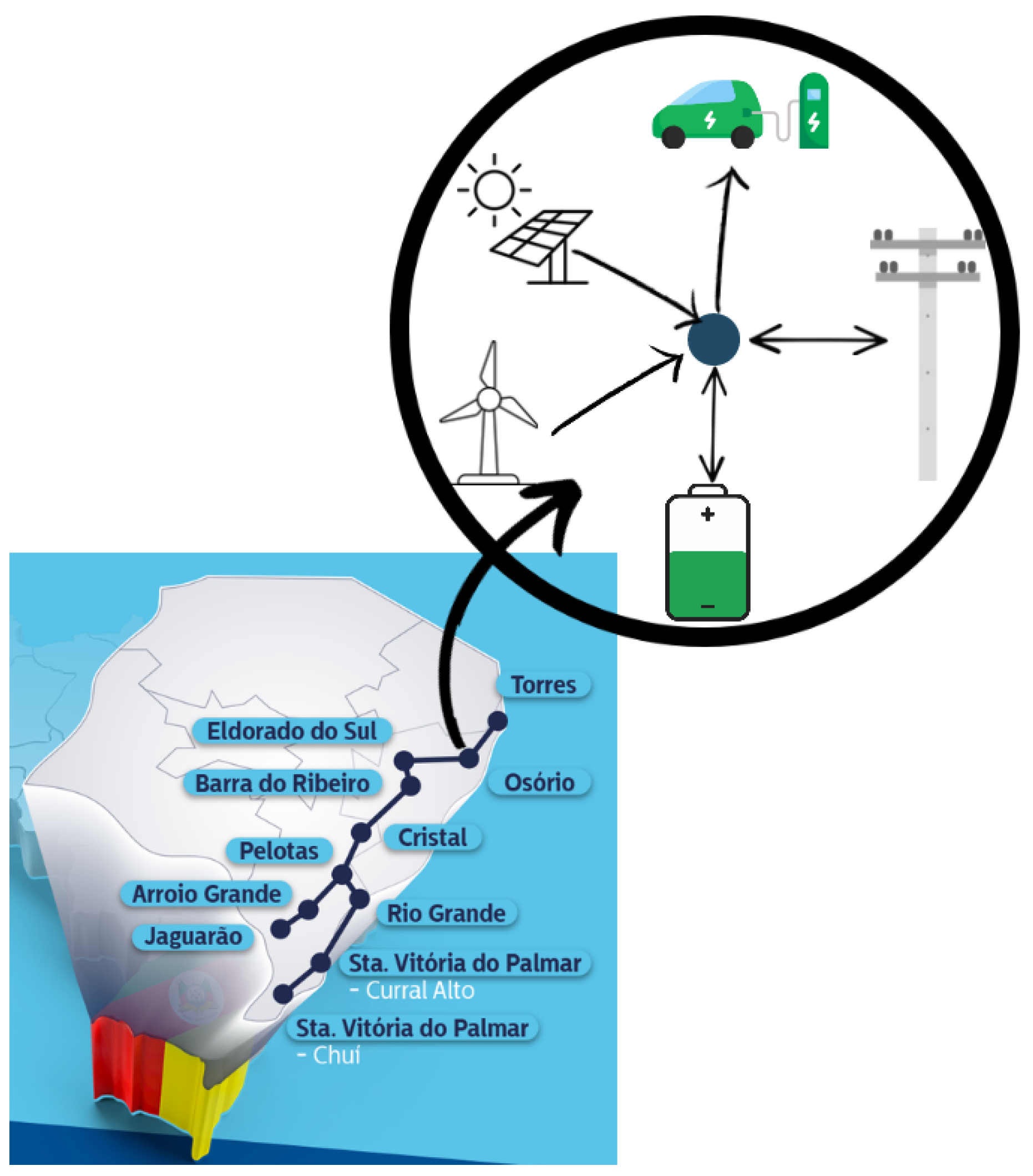

The following shows the modeling carried out to estimate the recharges in the MG, the generations coming from WT and PVS, the BESS wear model is detailed, and later the algorithm developed to optimize the energy management in the MG is presented.

3.1. EVFCS Usage Modeling

Forecasting and analyzing the demand for EV charging on highways faces significant challenges, as they rely on several external and unpredictable factors, such as mobility patterns, seasonality, weather, and human behavior. To address these uncertainties, several models have been developed, including approaches based on statistical data, learning from historical usage patterns, traffic surveys, and vehicle flow counts, among others.

In [

22], a methodology is presented to model typical vehicle usage profiles in Brazil, categorized according to the types of trips undertaken, enabling the estimation of charging demand. In turn, the study in [

23] builds upon these typical usage profiles for regular users and complements the analysis by including occasional users, modeled through simulations based on the Monte Carlo method. However, both approaches are focused on charging in residential contexts and parking lots, without considering the specificities of charging behavior on highways, which require a different analysis due to their unique characteristics and greater variability.

In the context of highways, two possible alternatives can be highlighted. The first is intended for initial operations, where a consolidated history of recharging data is not yet available. The second leverages observed patterns in the recharging behavior, such as energy consumption, recharge duration, and connection time. Therefore, at first, it is possible to use the methodology developed in [

24], since there is no history of recharges. The daily capacity behavior of the establishment, the typical variation of flow on the highway, the market share of EVs and the distribution of battery capacities of the EVs sold, served as a basis for estimating recharging events and then the EVFCS usage pattern [

24].

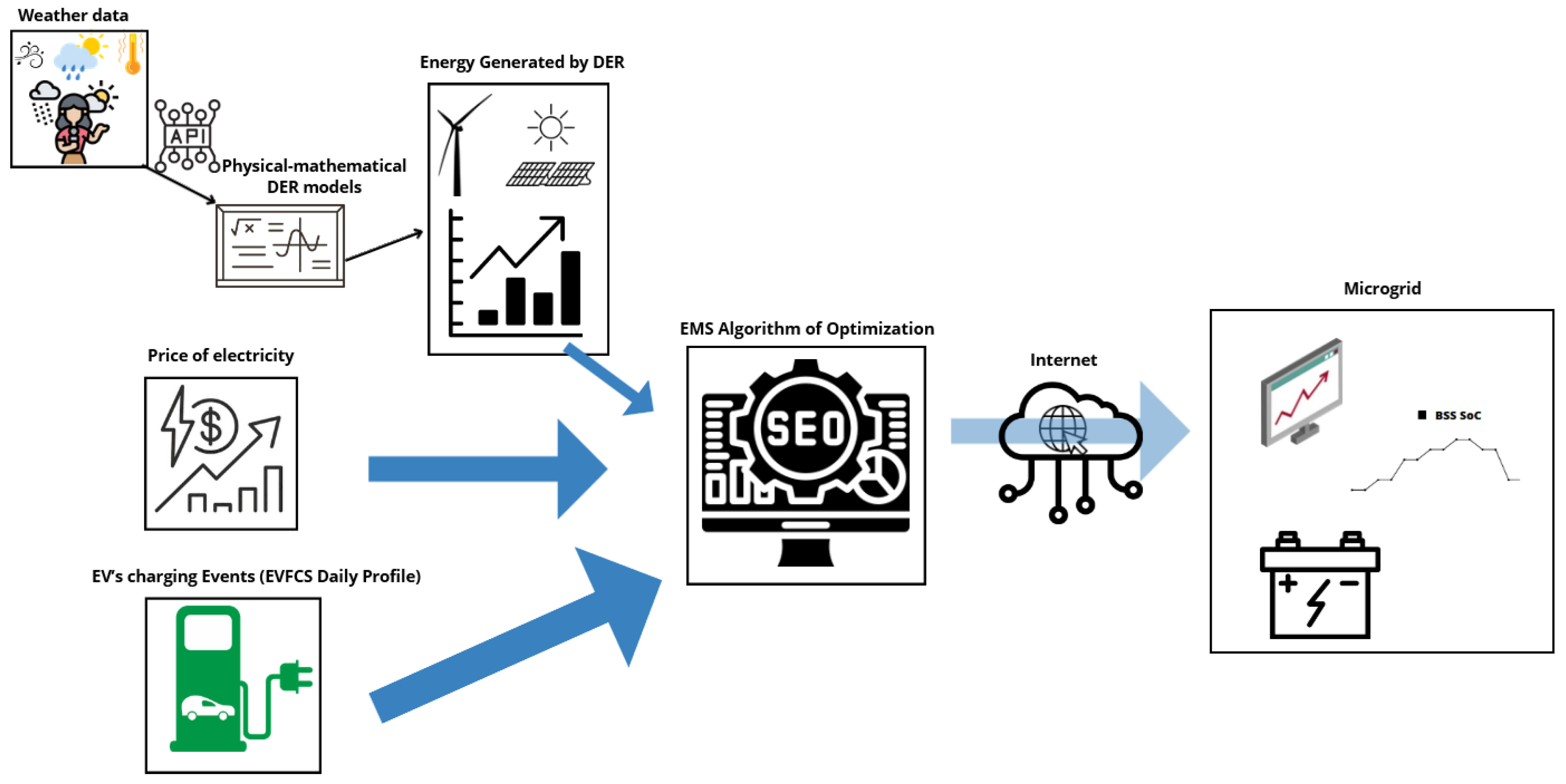

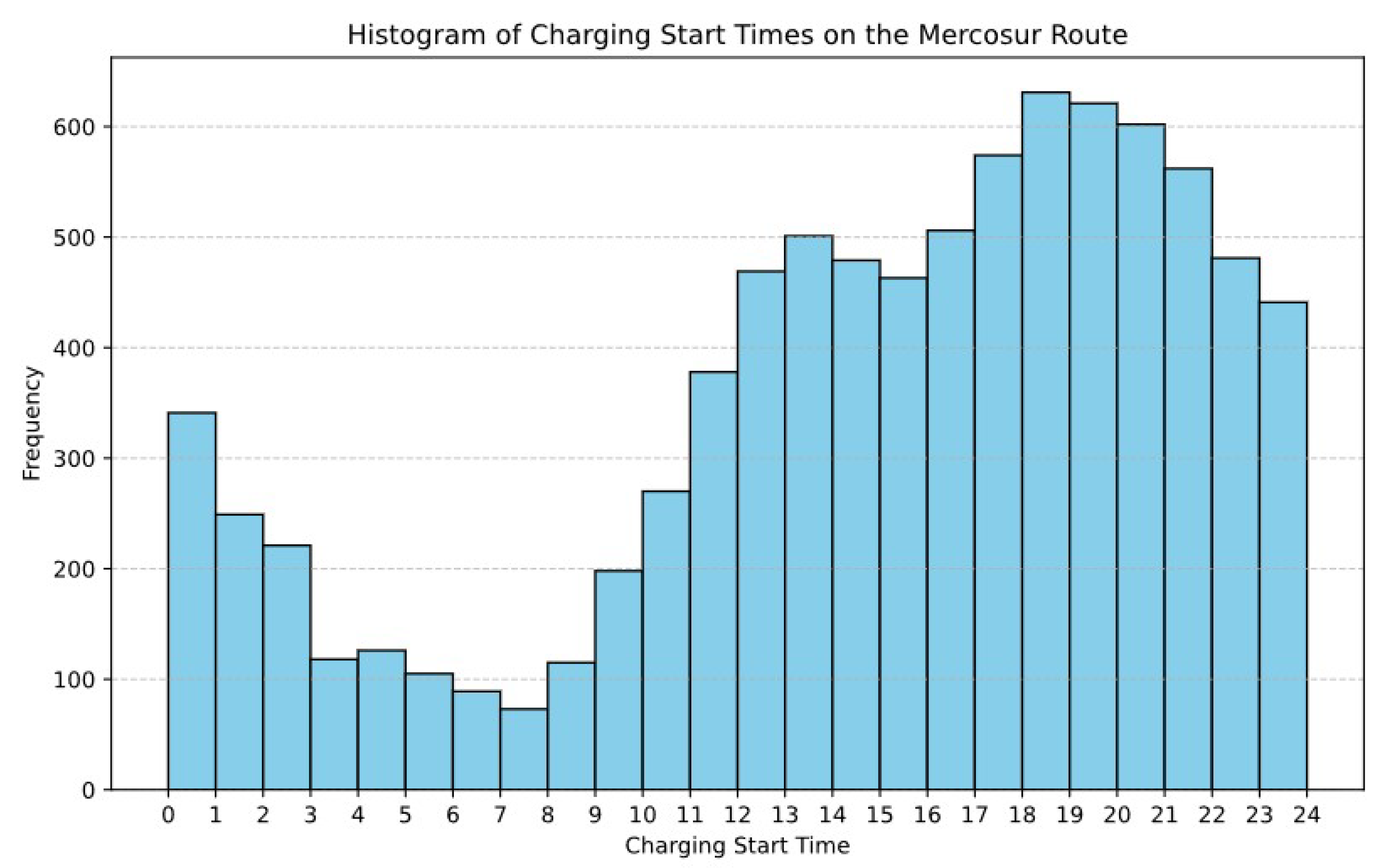

As a second option, already knowing the user’s behavior, the EVFCS demand curve will be obtained from the statistics of the recharge history. This is a more attractive option and will be used in this work. The algorithm developed follows the following step-by-step, which are illustrated in

Figure 2:

Load and Clear Data: Organize historical data.

Filter Relevant Data: Eliminate database errors, erroneous data, and outliers.

Analyze Trends: Identify historical patterns.

Generate Usage Profile: Create probabilistic models.

Simulate Scenarios: Generate daily recharge distributions based on historical patterns.

Preview Results: Show the simulated and average curves.

Export Data: Save results for integration with other systems.

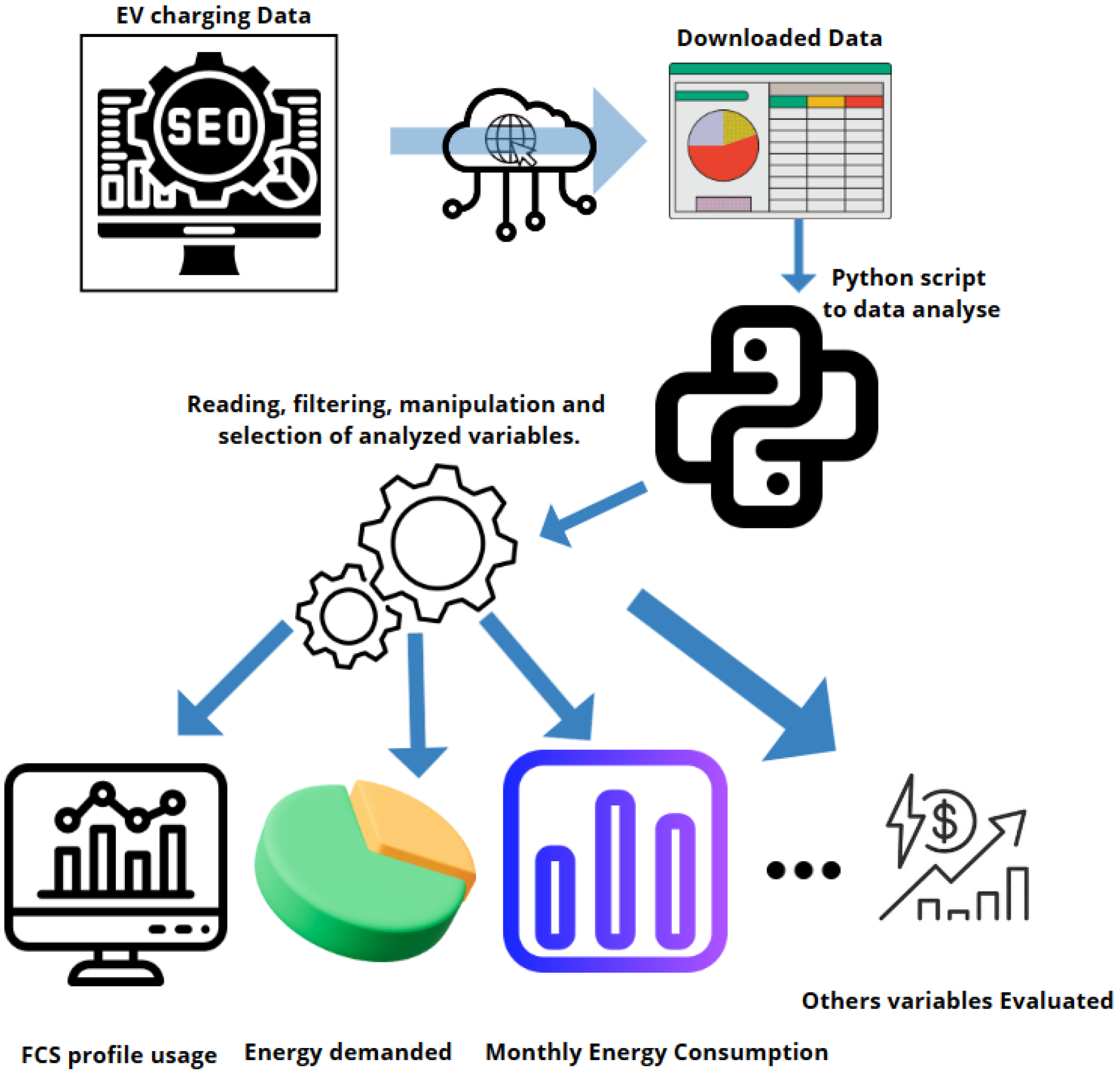

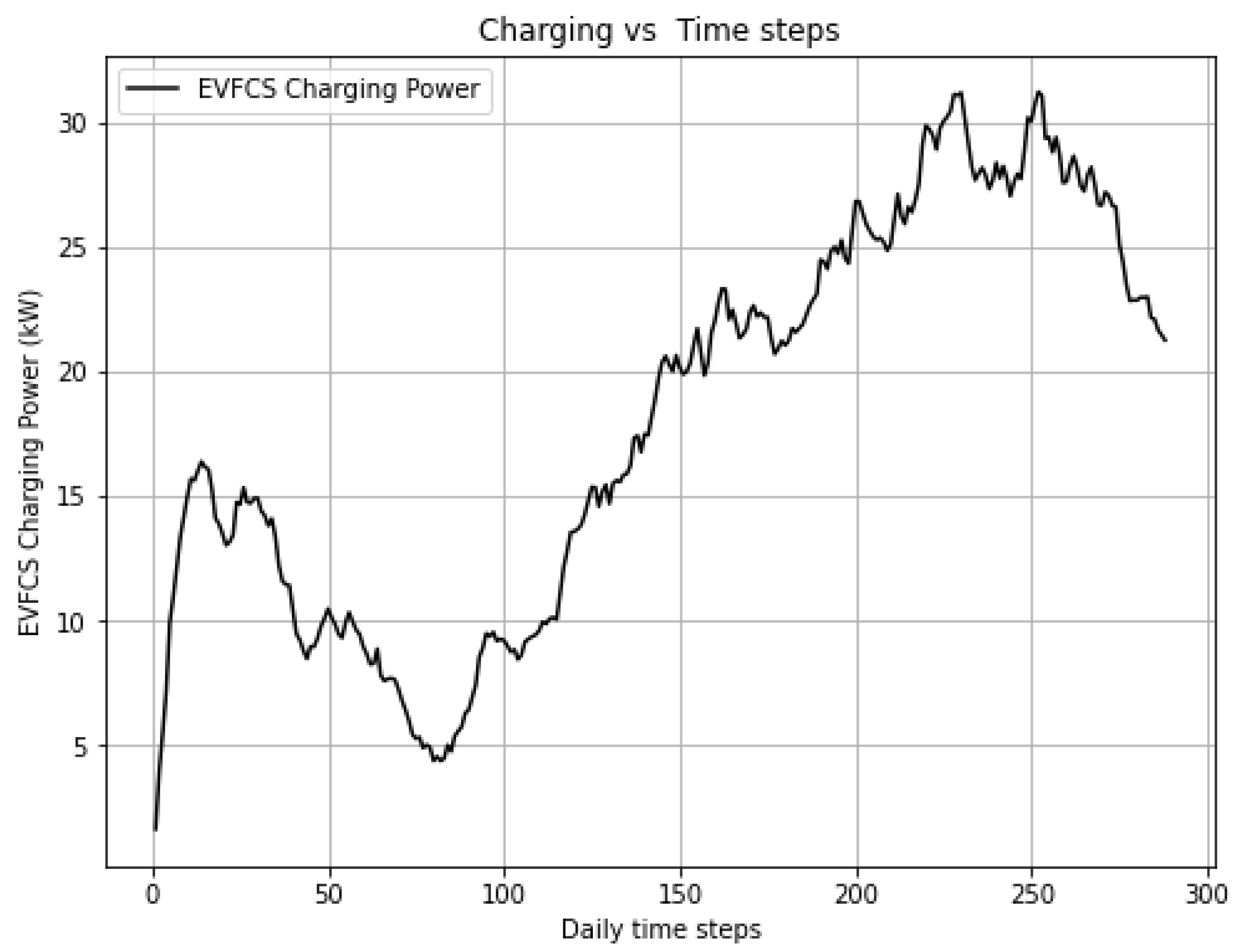

Figure 3 shows a daily recharge profile obtained following the process described above. This profile was generated from historical recharge data, which was organized, filtered, and analyzed to identify patterns of behavior. Subsequently, probabilistic modeling was used to create representative distributions of the characteristics of the recharges, such as duration, energy consumed, and start times. Based on these distributions, daily scenarios were simulated that reflect the typical use of the EVFCS. Finally, the results were viewed and exported for integration into the EMS algorithm.

3.2. Wind Generation Modeling

The use of wind kinetics for the generation of electricity depends on factors such as wind speed, turbine sweep area, characteristics of the installation site, such as soil roughness, altitude, and the construction characteristics of WT [

25,

26,

27].

There are different types of models used for wind generation forecasting. The main methods include physical, statistical, and hybrid models. The physical models are based on principles of fluid mechanics and the technical characteristics of the turbines, such as the power curve and the geometry of the blades, and are fed by meteorological data, such as wind speed and direction, obtained by numerical forecasts or local measurements [

28,

29].

Statistical models, on the other hand, use methods such as linear regression and time series to identify historical patterns, offering quick solutions, but with limitations in scenarios of high variability. Hybrid models combine physical and statistical approaches, integrating machine learning techniques to capture complex relationships between the variables involved [

28,

29]. The choice of model depends on the requirements of accuracy, time horizon, and data availability, with physical models standing out for their robustness when fed by detailed weather forecasts.

Deterministically, it is possible to calculate the mechanical power available in a wind turbine using eq. (

1):

where

is the mechanical power of the turbine (W, kW, or MW),

is the air density (kg/m

3),

is the power coefficient of the turbine or Betz limit,

A is the rotor area (m

2), and

is the wind velocity approaching the turbine (m/s). The air density is approximately 1.225 kg/m

3 under standard conditions of temperature and pressure (1 atm, 15.56 °C, at sea level). References [

25,

30] highlight that it is possible to estimate the air density based on the altitude of the location, when necessary. The higher the altitude, the more rarefied the air becomes, leading to a lower density [

25,

30].

Consequently, the electrical power generated by a WT is given by eq. (

2);

where

is the electrical power delivered (W, kW, or MW), and

is the total efficiency of the wind turbine system, including components such as the generator, gearbox, mechanical losses, and electrical losses [

25].

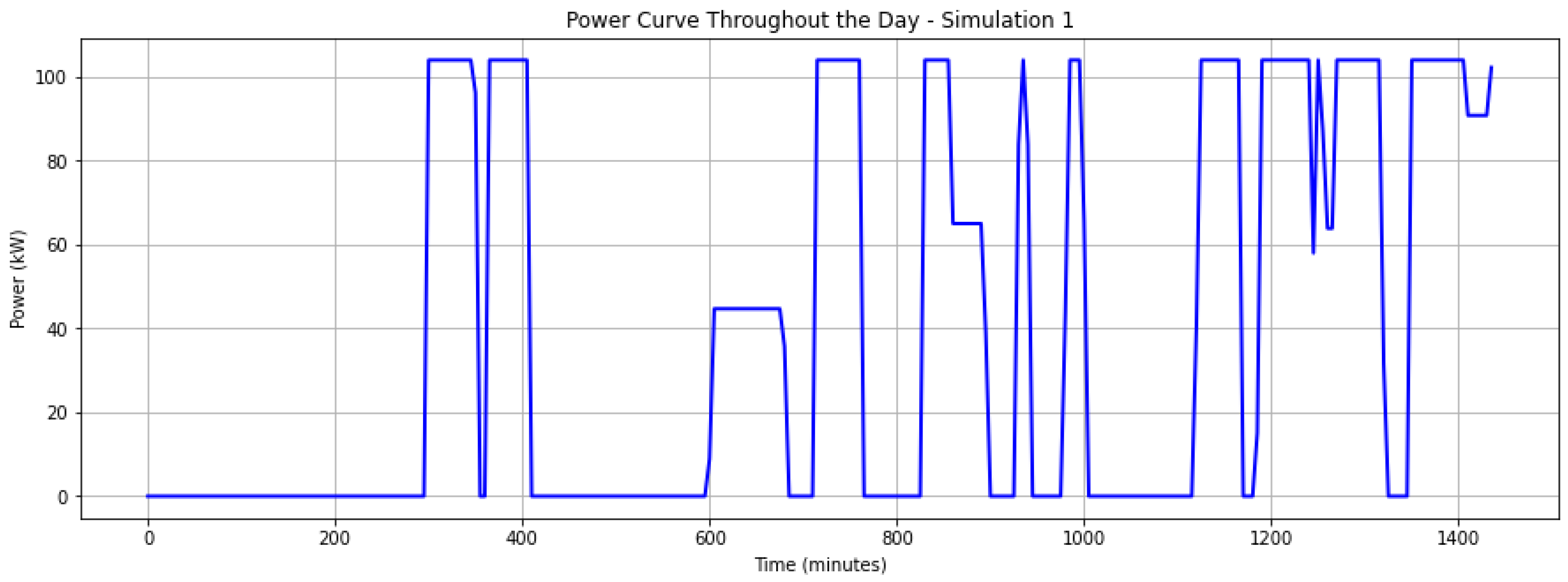

It is also possible to calculate the power generated by the wind turbine, through the turbine power curve provided by the manufacturer from tests. This curve relates the output power generated to the wind speed incident on the turbine blades.

Figure 4 shows a power curve as a function of wind speed for the 30 kVA WT.

Wind power generation is only possible above a minimum wind speed (cut-in speed) and varies with wind speed and turbine characteristics until reaching the cut-out speed, at which point the turbine must be shut down. Wind speed at the turbine blades must be adjusted, as API data typically provides wind speeds measured at 10 meters above ground. The Hellman Law is widely used in engineering and meteorology to extrapolate wind speeds from a reference height

to a height

z, considering the terrain properties and the logarithmic wind profile. This law provides a practical way to estimate wind speeds at different heights based on terrain roughness [

27,

31]. The basic formula of the Hellman Law is expressed as eq. (

3).

In this eq. (

3),

represents the wind speed at height

z (in m/s), while

is the wind speed at the reference height

(in m/s). The variable

z denotes the height at which the wind speed is to be extrapolated (in meters), and

is the reference height where the wind speed is already known (in meters). The exponent

depends on the roughness of the terrain and is an empirical parameter that varies with the type of terrain and atmospheric conditions.

The value of typically varies depending on the roughness of the terrain. For example, for water surfaces or very flat terrains, . In rural areas or regions with low vegetation, . In suburban areas or regions with medium-sized constructions, . Finally, for urban areas or regions with tall buildings, . The Hellman Law is a practical tool for estimating wind speeds at various heights. However, its accuracy depends on the assumption of a constant wind profile and the consistency of terrain roughness. Abrupt changes in terrain or atmospheric instability can reduce the precision of this method.

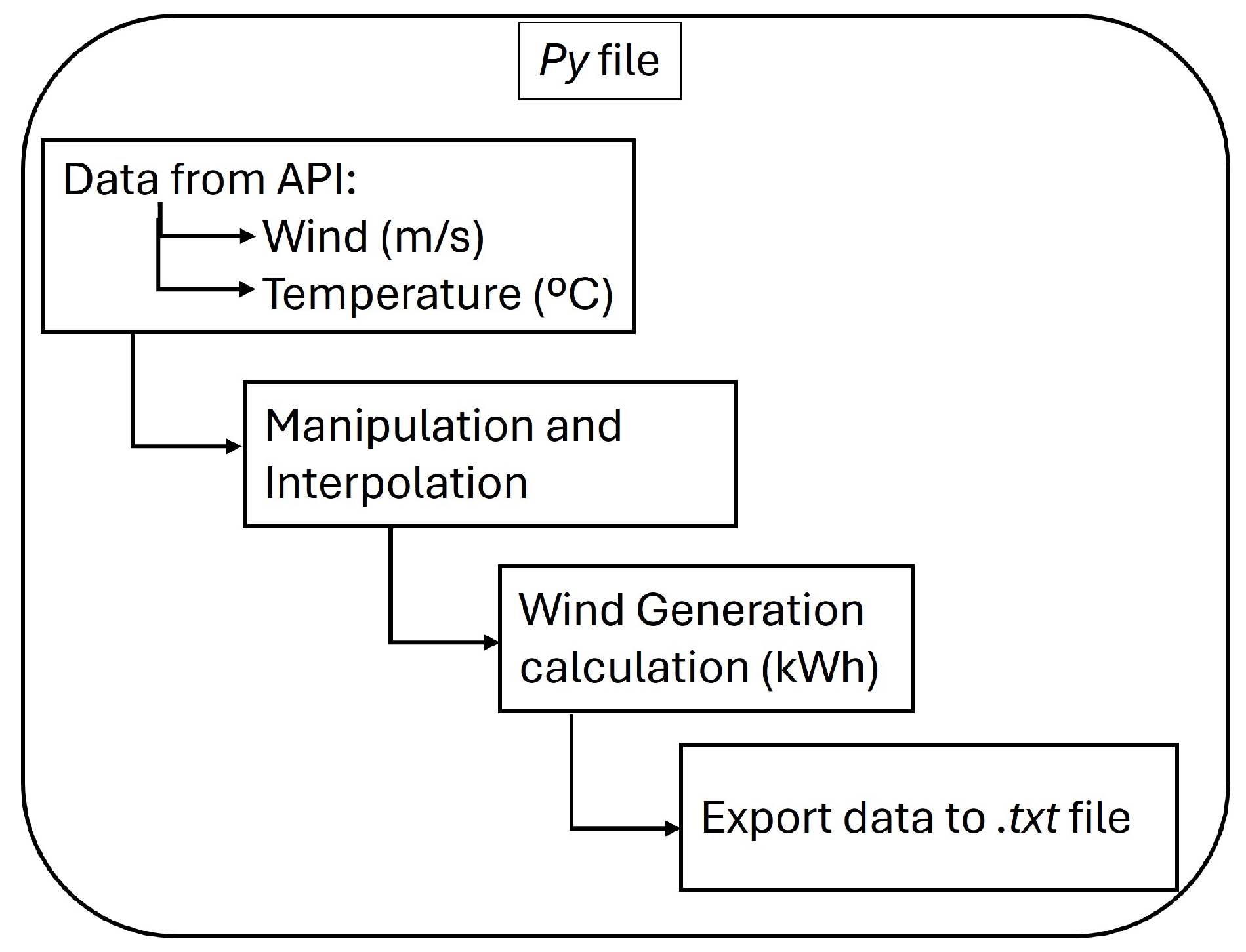

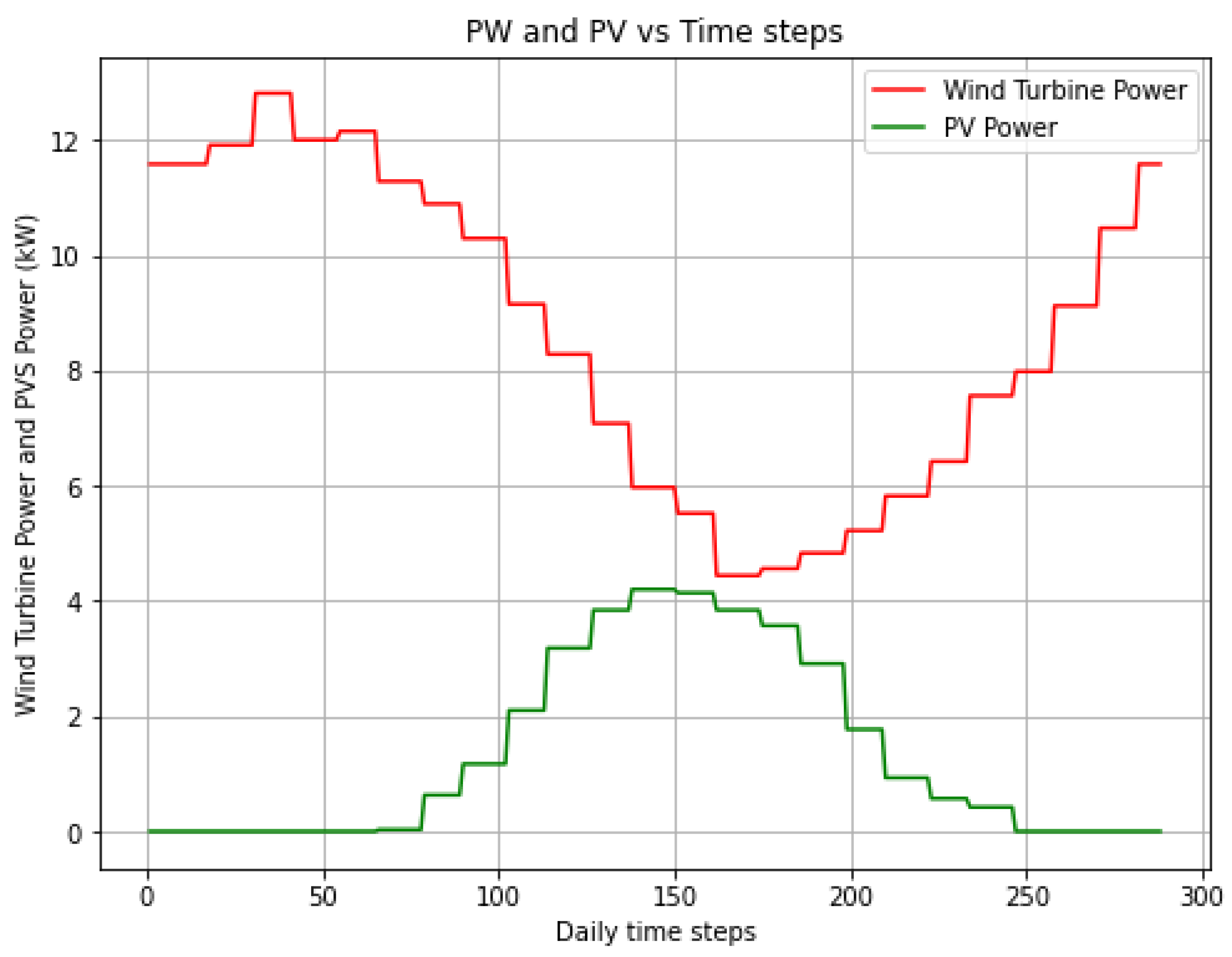

Via weather API, wind speed forecasts are obtained for the next day. Data interpolation manipulations are performed every 5 minutes, and the wind speed is corrected, via Hellman’s Law, for the height of the wind turbine. Thus, it is possible to calculate the generation, as shown in the diagram in

Figure 5.

3.3. PV Generation Modeling

Photovoltaic generation forecasting methods are widely used to optimize the use of solar energy, and are divided into three main approaches: based on physical models, statistical methods, and artificial intelligence techniques. Physical models use meteorological information and characteristics of photovoltaic systems, such as solar radiation and ambient temperature, to estimate energy generation based on physical principles. Statistical methods, on the other hand, apply time series and mathematical models, such as linear regression and ARIMA, to identify historical patterns and make short-term predictions [

32,

33,

34].

On the other hand, artificial intelligence techniques such as Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), machine learning, and hybrid algorithms offer more accurate forecasts by learning from large volumes of historical and weather data. The combination of physical models from the panels with weather forecast data has significant advantages, such as greater accuracy when incorporating real-time weather conditions or day-ahead forecasts and adaptability to local variations, allowing you to optimize energy generation and planning more efficiently and reliably [

32,

33,

34].

The calculation of photovoltaic generation is based on the nominal power of the module, the rate of reduction of the efficiency of the photovoltaic module due to degradation, solar irradiation at the installation site, and the temperature of the module, according to the eq. (

4) [

33,

35].

where

is the output power of the photovoltaic module (kW) at hour

h,

is the nominal power of the photovoltaic module under standard test conditions (kW),

is the efficiency reduction factor of the photovoltaic module due to degradation (%),

is the total irradiance on the surface of the Earth (W/m

2) at hour

h,

is the irradiance under standard test conditions, assumed to be 1000 W/m

2,

is the power temperature coefficient (%/°C),

is the photovoltaic panel temperature (°C) at hour

h, and

is the photovoltaic panel temperature under standard test conditions, assumed to be 25°C [

33]. All parameters under Standard Test Conditions (STC) correspond to those tested by manufacturers in laboratory conditions.

The modeling of the cell temperature in the photovoltaic panel is directly related to ambient temperature and solar irradiance. Equation (

5) presents this approach, where

is the ambient temperature measured at hour

h,

is the hourly irradiance, and Nominal Operating Cell Temperature (NOCT) is the nominal operating cell temperature of the photovoltaic panel [

36,

37].

Finally, the output power per photovoltaic panel was estimated using eq. (

4), the total power generated is proportional to the power of each panel and the number of panels installed,

, as shown in eq. (

6). It is worth mentioning that the photovoltaic generation model considers panels with the same generation capacity, positioned similarly, and under similar conditions, accounting for shading and surface states.

This mathematical approach aligns with the methodology employed by the Homer software to calculate a plant’s photovoltaic generation.

can be inserted into the software as a text file with hourly data, generated from Typical Meteorological Year (TMY) data for the location. In the absence of such data, Homer uses the Graham algorithm to generate synthetic irradiance series [

38]. This algorithm produces hourly irradiance values based on latitude and monthly average irradiance values. Therefore, it allows energy estimates for long periods.

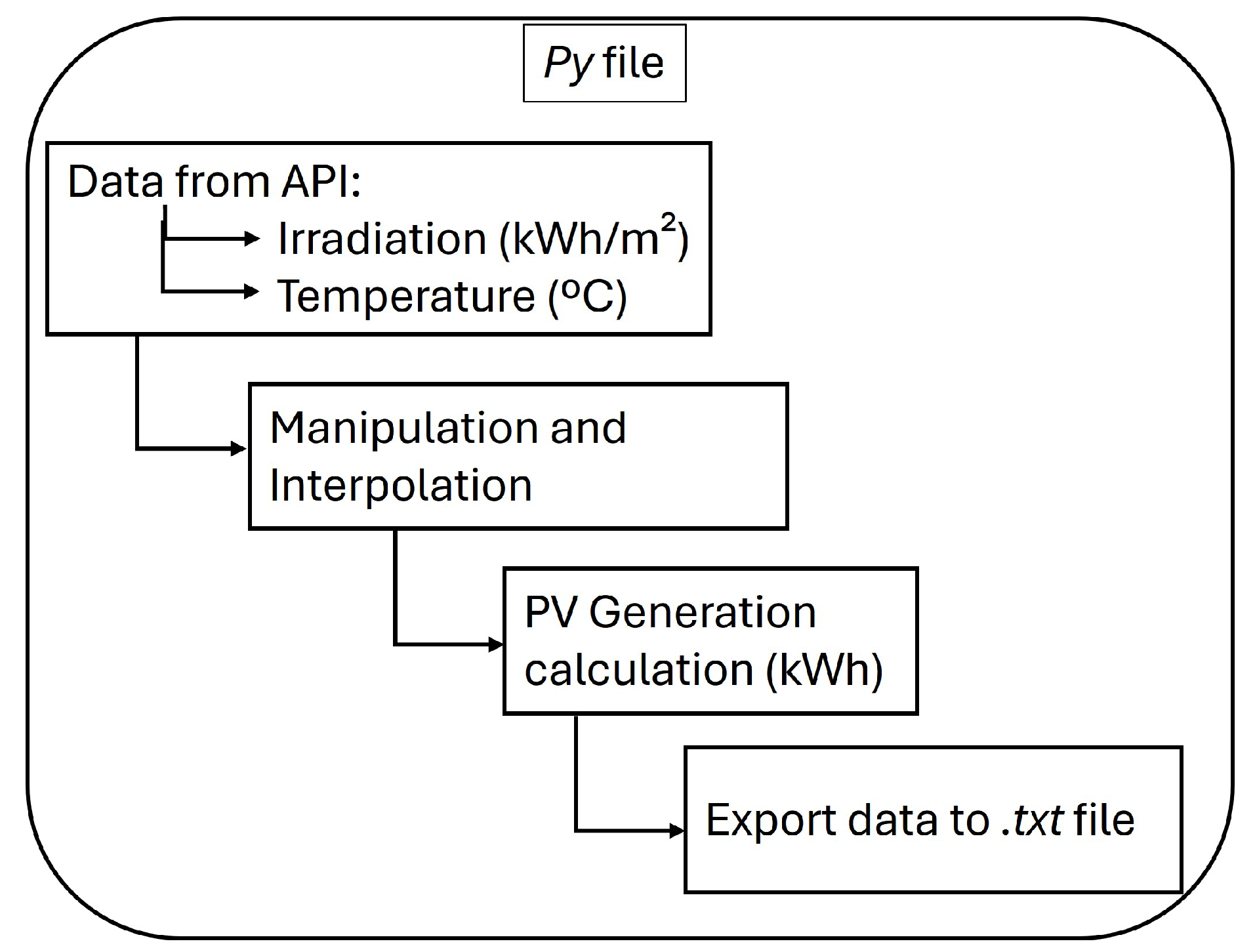

However, for the short term, the data obtained via weather API for the next day ensures better accuracy and precision in estimating the photovoltaic generation profile. The sequence of steps followed is shown in

Figure 6. Since the data comes in every hour, some manipulations and interpolations are required to obtain a daily profile with 5-minute discretization, which will be the resolution used in the optimization algorithm.

3.4. BESS Degradation Cost Model

BESS is costly, especially considering their limited lifespan, as batteries can only endure a finite number of charge-discharge cycles before reaching the end of life (EOL), typically defined as a 20%–30% reduction in the state of health (SoH) [

39]. The degradation of li-ion batteries occurs as a function of variables such as temperature, calendar effect, intensity of discharges, and applied currents, among other factors, according to [

40,

41,

42,

43]. Among the available technologies, lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) and lead-acids are predominant in modern BESS applications.

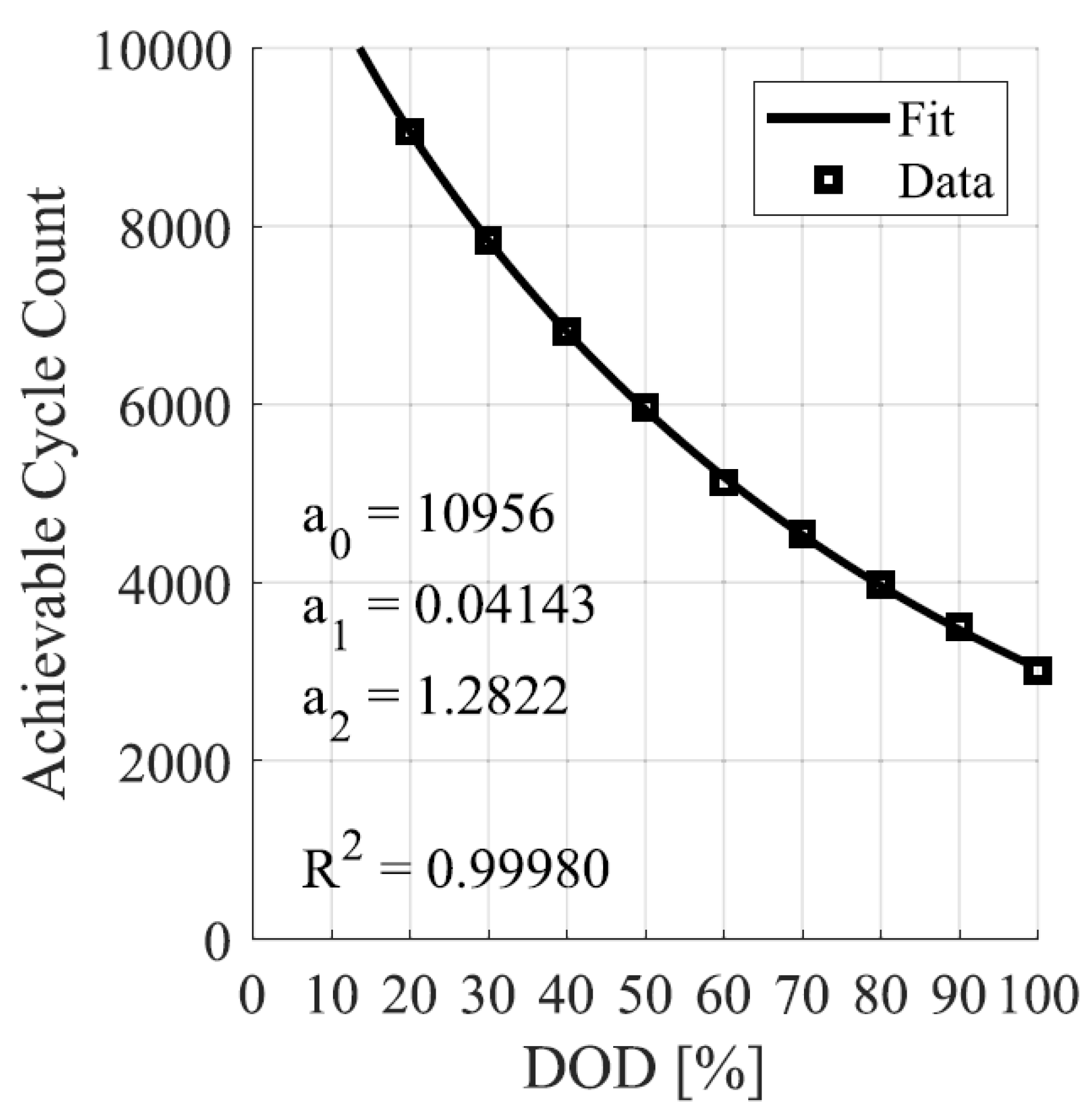

Various models are used in the literature to predict and mitigate battery degradation. Empirical and semi-empirical models are widely used due to their simplicity and ability to provide quick estimates based on experimental data. These models correlate the number of charge/discharge cycles with the depth of discharge and temperature. This work uses the modeling presented by [

9], which updates the empirical battery wear model proposed by [

44] considering the battery’s wear as a function of the intensity of discharge. So, the total cycles of a battery are reduced when it is subjected to high DoD.

In the literature, some functions are proposed to relate the Achievable Cycle Count (ACC) to the DoD. Since life cycle data is often presented at discrete DoD levels, interpolation is useful. To achieve this, a generic function

can be defined in various formats to fit different wear curves. In [

44] is proposed the reciprocal function

, where

and

are curve-fitting coefficients, but it has limitations in universality. Alternative formats, such as the exponential,

and logarithmic,

, also fit specific cases well but fail to generalize. To address this, a combined reciprocal and exponential model is proposed by [

9] for broader applicability, as shown eq. (

7).

where

,

and

are coefficients that can be obtained by methods such as the least squares fitting, and

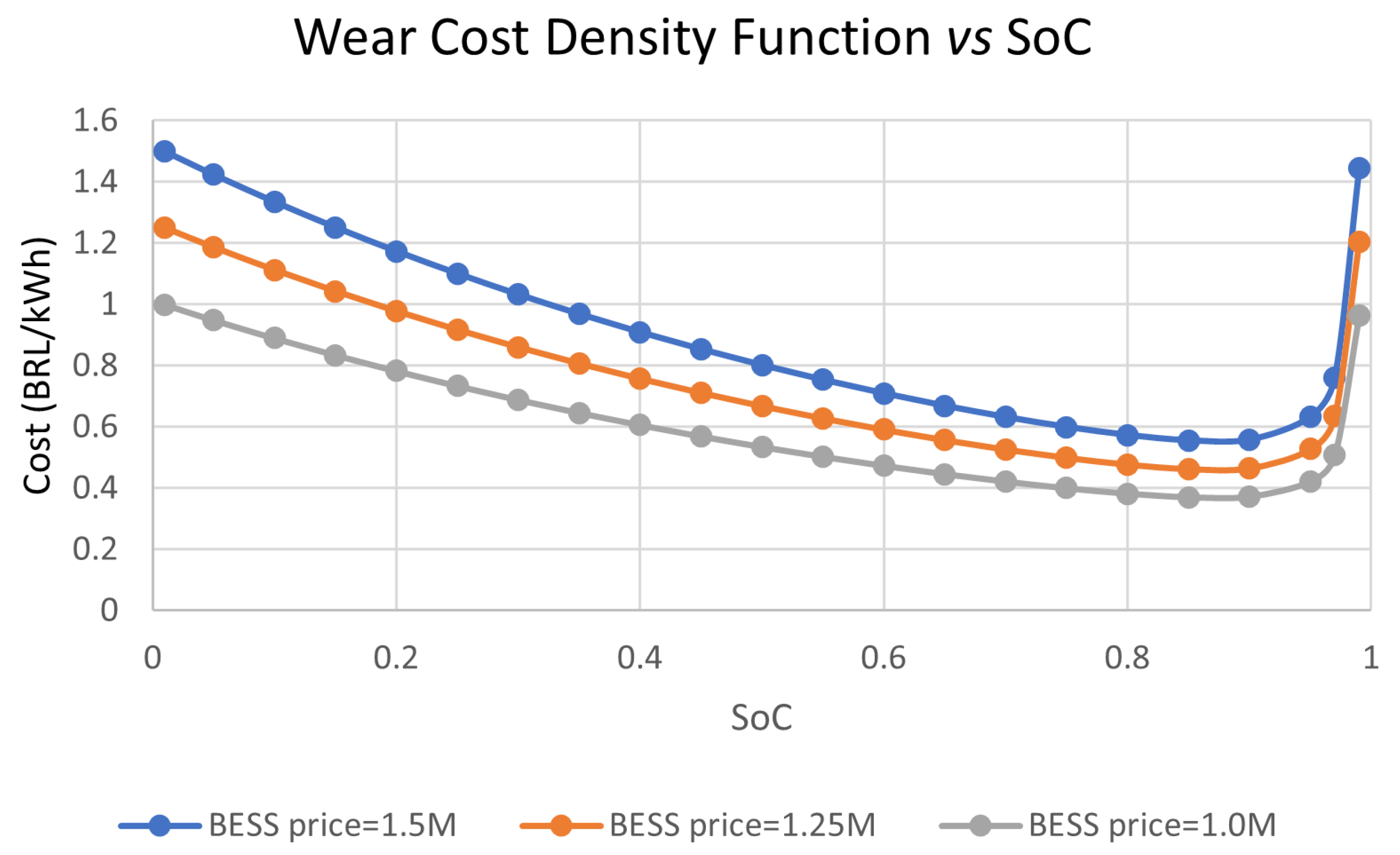

d is the DoD of BESS. Considering the cost, capacity, and ACC vs DoD curve of the BESS, and performing the necessary mathematical manipulations, [

9] derived a Normalized Wear Density Function,

, expressed in terms of monetary cost per unit of energy transferred (typically

$/kWh), as shown in eq. (

8). This formula allows you to calculate the density of wear as the DoD varies.

where

is a modulating factor to account for temperature fluctuation, calculated as

, where

is the temperature of the battery in Celsius. The

is the BESS price (

$),

M represents the BESS capacity (kWh), and

is the current DoD of the BESS.

The average value of the Wear Density Function is useful for assessing the cost-benefit of different battery models, as it considers not only price and capacity but also durability. The average value of eq. (

8) is calculated as eq. (

9):

Since

has nonlinear variation behavior as a function of the SoC, it is necessary to use a piecewise linearization algorithm to insert this variable into linear optimization problems [

45].

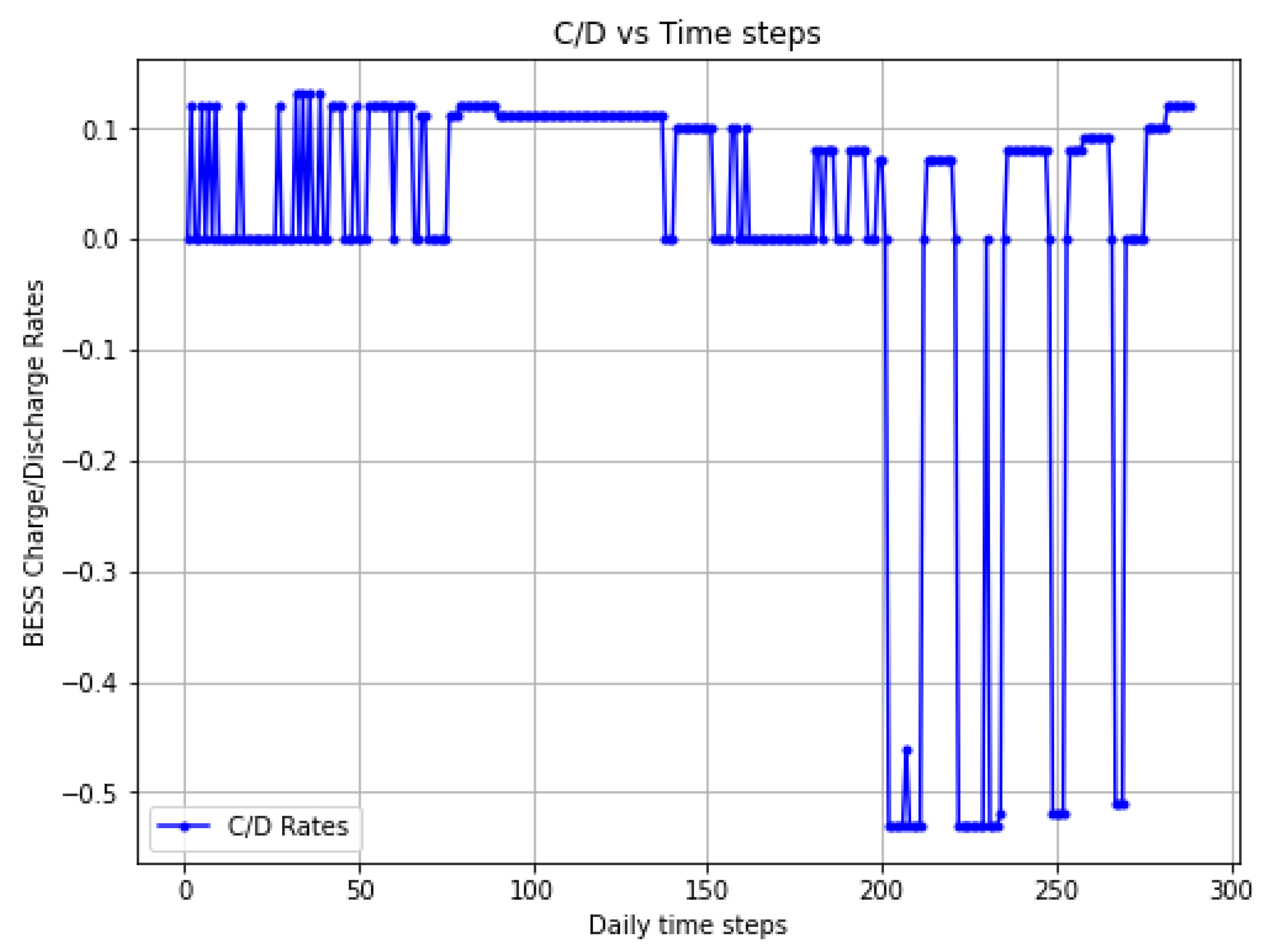

3.5. Proposed Optimization Algorithm

The main objective is an optimized power distribution between the grid and BESS according to the utilization of local renewable energy production and the reduction of operating costs. Therefore, the controllable power rate defines when the BESS charges or discharges energy. These are the decision variables for the optimization problem. This formulation was chosen for its maturity, availability of tools, and fast and robust convergence to the global optimum.

A formal description of this optimization requires definition of the following parameters and variables, as summarized in

Table 1.

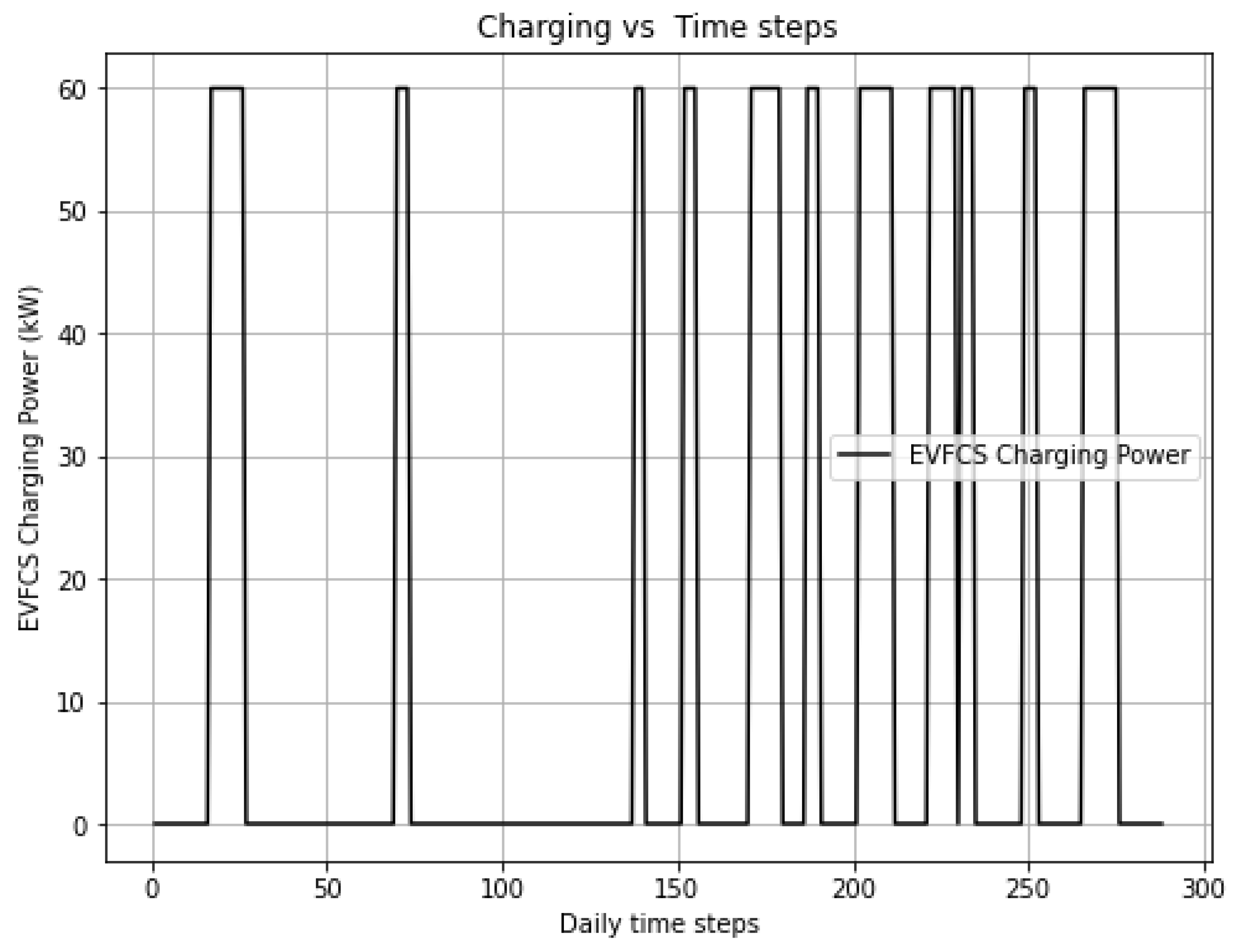

The MG energy management problem involves the optimization of static storage discharge/charge events to meet the charging demands of EVs while reducing operating costs. In this sense, charging is preferred when it is cost-effective, or discharging is preferred when energy costs are high, given the variation in hourly electricity price. The dispatch scheduling problem is approached by time window, so that the total available period

for discharging/charging during the day is uniformly distributed over a sample interval

within

intervals, as in eq. (

10).

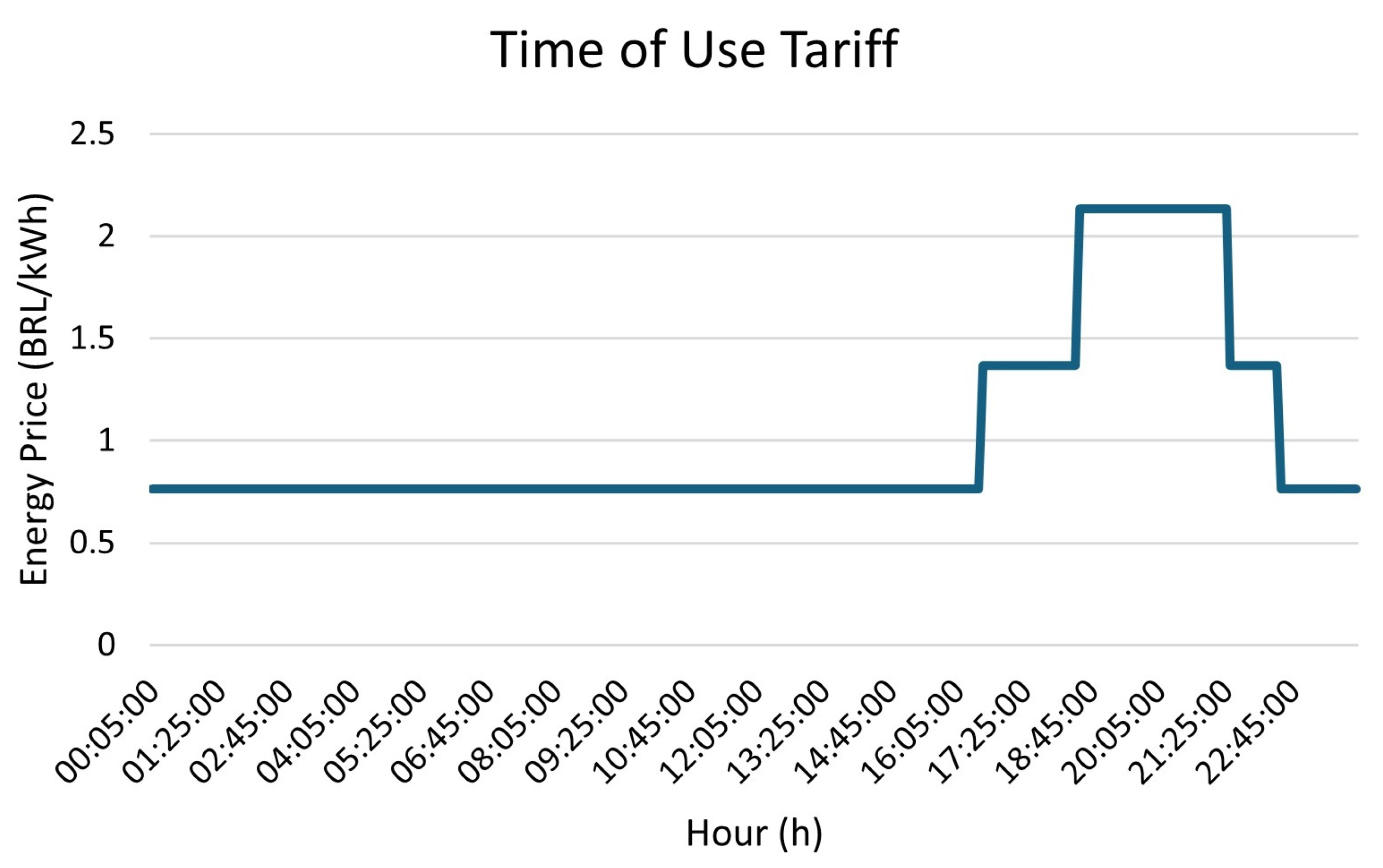

Note that the problem only comprises unidirectional charging of EVs and bidirectional discharging/charging of BESS. Thus, the EMS should preferentially dispatch power from the BESS during periods of peak tariff, while prioritizing dispatch from the grid when the tariff is cheaper. It is important to emphasize that the energy coming from PVS and a WT is constantly used by the MG in the form of constraint. It is more efficient to use the generated energy directly for charging EVs, without losses from conversion to BESS. When there is no charging of EVs, the energy is injected into the grid by the net metering system or it is stored in the BESS.

The objective function (OF) consists of scheduling the discharging/charging of the BESS to minimize the costs of buying, selling, and storing energy, according to eq. (

11). The optimal power dispatch between local renewable sources, BESS, or grid is determined at each time instant

j to achieve the objective and ensure the correct MG operation. When energy is sold to the grid, the cost considered is the loss in the value of the kilowatt-hour by the net metering discount.

The constraints of the optimization problem comprise (a) energy balance, (b) SoC of the BESS, and (c) BESS power. An energy balance constraint is set to ensure that the load on the MG is equivalent to the energy consumed, according to eq. (

12).

The loads are the total power required to charge the connected EVs () and the power to charge the BESS (). Also, there is power injected into the grid (). As the energy source, we have a photovoltaic generation (), wind generation () and the BESS discharging power (). Also, there is the amount of energy purchased from the grid ().

Full participation of photovoltaic and wind generation in the form of an energy balance constraint is assumed. In this way, the conversion of energy to the battery is prevented by using it at the same instant of generation and EV connection, bypassing possible efficiency losses. In the case of highway fast charging, the demand for EVs is not controllable, so, like local renewable generation, it cannot be visualized in the objective function, but it is present in this energy balance constraint.

Note that power available by photovoltaic (

) and wind (

) systems are the estimated at each time instant,

j. As already described, wind and photovoltaic daily generation profiles are obtained from physical models, fed with wind and irradiance data obtained via weather forecast APIs [

20].

The maximum power requested and supplied to the grid (

) are constrained as a tool to prevent overload of the distribution transformer for any time instant

j. This restriction can be fixed or variable in time to limit energy purchases in periods of higher tariffs, depending on the tariff structure addressed. In this case, a fixed value is considered, since the ToU adopted for the case study bills only the amount of energy and not the power. Furthermore, a binary power exchange logic is formulated to prohibit the scenario of energy purchase and injection at the same instant of time

j, according to eq. (

13) and eq. (

14).

where

is a binary auxiliary parameter used to indicate whether energy should be purchased or injected into the grid, according to eq. (

15).

The BESS can be charged, discharged, or remain inactive at each time step. Thus, BESS scheduling is decomposed into two variables, one for charging (

) and one for discharging (

), for

. Both discharging/charging powers are controllable and constrained by their upper limits, i.e., (

and

), respectively, according to eq. (

16) and eq. (

17). The power exchange logic is implemented to make it impossible to charge and discharge simultaneously, according to eq. (

18).

where,

is a binary auxiliary parameter used to indicate when the BESS is charged or discharged, according to eq. (

18).

At the beginning of each day, the initial BESS SoC

is computed, according to eq. (

19).

As a guarantee that there will always be an amount of power remaining in the BESS, to keep the operation offline, and provide emergency recharges, in the problem the initial SoC, , is set at least 50%. Likewise, at the end of the simulation day, the final SoC is required to be at least equal to 50%, i.e., .

According to eq. (

20) always at the beginning of the day, the BESS SoC should be equal to or greater than the initial one,

. Thus, 288 is the total

j period in a day, and

is the total days in the chosen period (7 in a week, 30 in a month, and 365 in a year). Obviously, for simulations of only one day, this restriction can be disregarded or set a value of 1 for

.

The current SoC (

) at any time instant

j, denoted by eq. (

21), can be obtained by considering:

The SoC at the previous time step ();

The increment of SoC as a result of charging;

The SoC decrease due to discharging.

where

is the discharge/charge efficiency;

is the battery capacity, in kWh;

is the time sample, in hours. The SoC is restricted at its extreme limits to prevent overcharging and deep discharging, according to eq. (

22).

As the BESS serves as a power source in the MG, there must be a minimum amount of energy to provide power to EVs. To guarantee such a minimum requirement for the next day, BESS’s SoC must satisfy a minimum threshold at the last time step of the current day’s scheduling, according to eq. (

23).

Another restriction that can be used refers to the maximum total charge and discharge cycles that the BESS can have during the total period considered. In this way it is possible to reduce the loss of capacity of the BESS due to the wear of the system by the excess of cycles, as equated in eq. (

24) and eq. (

25).

where

is the maximum total number of charging cycles.

where

is the maximum total number of discharge cycles. These parameters can be useful if considering periods longer than 1 day of simulation. Thus, the operation of the BESS can be limited to a maximum number of charge and discharge cycles, defined by the owner of the MG.

To ensure efficient operation and preserve the life of the BESS, restrictions have been imposed that prevent abrupt changes between the loading and discharging states. These restrictions ensure that the BESS goes through a transition state, called idling, in which it performs neither loading nor unloading before switching between these two modes of operation.

The first constraint prevents the BESS from switching directly from the discharging mode to the charging mode. In this case, if the system was discharging in the previous period (

), it cannot enter charging mode in the current period (

), ensuring that the charging state is zero (

). The constraint can be mathematically expressed in eq. (

26).

Similarly, the second constraint prevents the BESS from switching directly from charging mode to discharging mode. Thus, if the system was charging in the previous period (

), it cannot enter discharging mode in the current period (

), ensuring that the discharging state is zero (

). This relationship is mathematically represented in eq. (

27).

These restrictions ensure that BESS operates in a stable manner, avoiding behavior that could cause premature wear and damage to the system. In addition, this approach promotes a more controlled transition between operating modes, contributing to the reliability and efficiency of the system.

In addition to technical and operational constraints, other constraints may also be included in the model. Some restrictions defined by the authors are presented below to better personalize the study.

Restriction 1: The restriction ensures that the BESS will be charged only when there are no recharges in progress in the system. The inequality of eq. (

28). limits the surplus of DER used to charge the BESS, ensuring that this process occurs only in the absence of other recharges. This restriction prevents excessive energy demand from the grid at the same time.

Restriction 2: The restriction imposes a limit on the charge of the energy storage battery (BESS), ensuring that it does not exceed the instantaneous sum of the power generation of the wind and photovoltaic at the instant

j. This condition is necessary to ensure that BESS charging only uses the energy available from the DER, avoiding the use of external sources or the violation of the physical limits of the system, as eq. (

29).

Restriction 3: The restriction states that the discharge power of the BESS may not exceed the maximum charging power requested by electric vehicles at the instant

j. This limitation ensures that the BESS discharges only the energy necessary to meet instantaneous demand, avoiding overloading or wasting energy, while keeping the system compliant with operational requirements, as shown eq. (

30).

Restriction 4: The restriction limits the maximum power that can be injected into the electricity grid, ensuring that this power does not exceed the sum of distributed generation from wind and photovoltaic sources at the instant

j. This formulation allows for dynamically controlling the power injection into the grid, ensuring that the injection is limited or allowed according to the availability of distributed generation, as shown eq. (

31).

Restriction 5: The restriction ensures that at least 80% of the energy generated by DERs (wind and photovoltaic) is consumed locally, limiting the injection of energy into the electricity grid to a maximum of 20% of the total generated, as shown eq. (

32).

This restriction promotes the efficient use of locally generated energy, reducing dependence on the power grid and minimizing losses related to transmission and distribution. In addition, it is aligned with sustainable practices and incentives for the self-consumption of renewable energy.