Introduction

Dermatophilosis is a contagious zoonotic skin disease caused by the Gram-positive actinomycete Dermatophilus congolensis, primarily affecting cattle but also other domestic and wild animals, and occasionally humans (Dickson and de Elías Costa, 2010). The disease manifests as exudative dermatitis with characteristic scab formation, crusting, and hair loss, leading to significant animal welfare concerns and economic losses through reduced growth, milk yield, and hide quality (Yeruham et al., 2003). Transmission occurs via direct contact with infected animals or indirectly through fomites and insect vectors (Osman et al., 2014; Quinn et al., 2002), with prevalence highest in warm, humid tropical and subtropical regions where environmental and management factors exacerbate disease impact (Kumar, 2018).

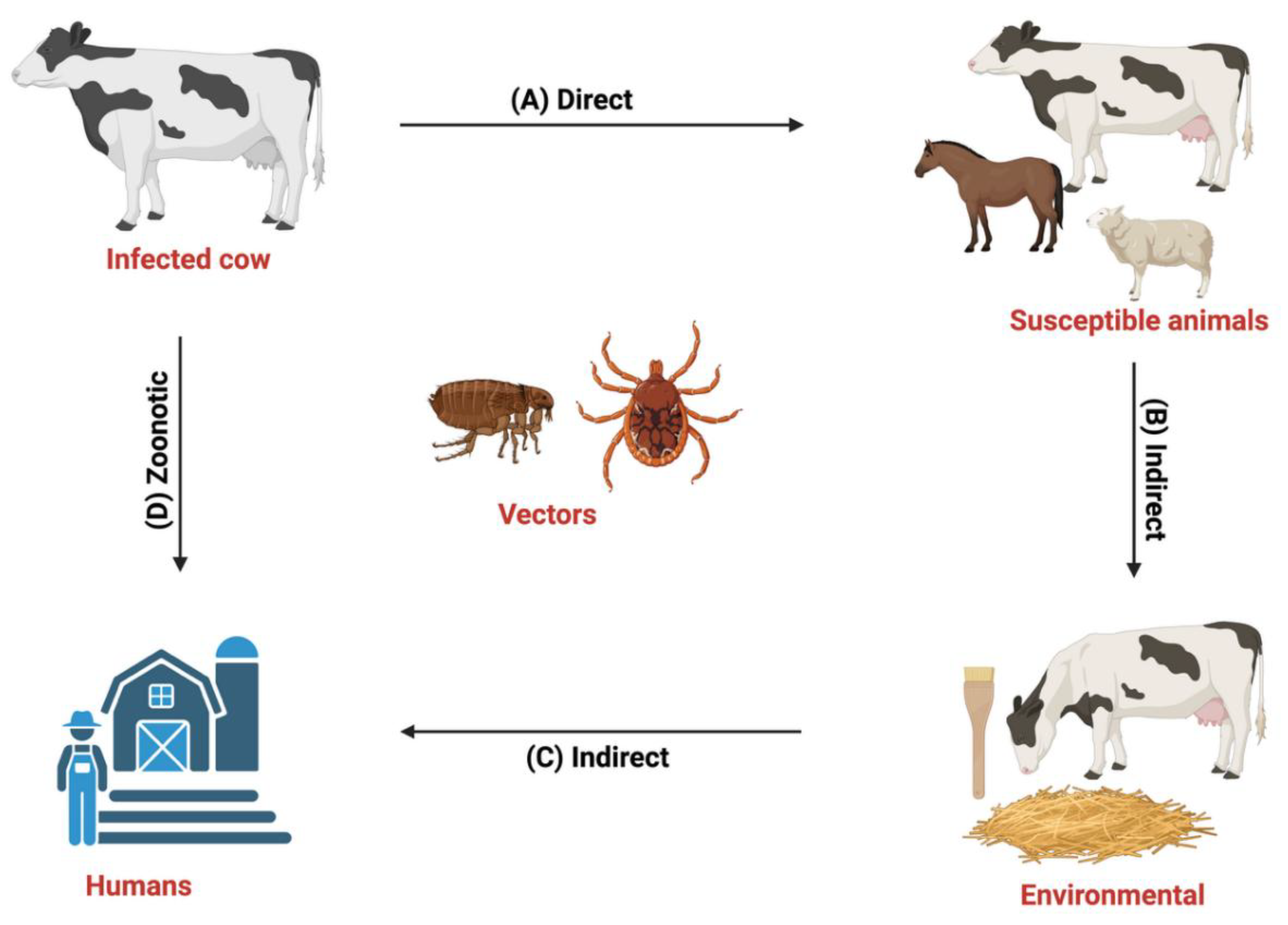

Figure 1.

Transmission cycle of Dermatophilus congolensis. (A) Direct contact occurs among animals in the same herd, or via the transfer of zoospores to nearby animals that are susceptible to the disease, such as cattle, goats, sheep, horses, and, rarely humans (Zoonotic). (B) Indirect contact occurs with the use of contaminated materials, such as skin brush, and bedding, or through grazing, or mechanical vectors such as ticks, flies, and other ectoparasites (C and D) Zoonotic transmission occurs among people working with animals, such as veterinarians, animal handlers, and abattoir workers, that do not observe proper biosecurity measures. Figure designed with Biorender.com.

Figure 1.

Transmission cycle of Dermatophilus congolensis. (A) Direct contact occurs among animals in the same herd, or via the transfer of zoospores to nearby animals that are susceptible to the disease, such as cattle, goats, sheep, horses, and, rarely humans (Zoonotic). (B) Indirect contact occurs with the use of contaminated materials, such as skin brush, and bedding, or through grazing, or mechanical vectors such as ticks, flies, and other ectoparasites (C and D) Zoonotic transmission occurs among people working with animals, such as veterinarians, animal handlers, and abattoir workers, that do not observe proper biosecurity measures. Figure designed with Biorender.com.

Despite its global distribution and significant burden on livestock production, D. congolensis remains a neglected pathogen with limited molecular characterization. The bacterium exhibits a complex life cycle involving filamentous hyphae and motile zoospores (Hemavathi et al., 2023; Gordon and Edwards, 1963), and shows genetic diversity with distinct strains reported across geographic locations (Branford et al., 2021). There is currently no fully effective treatment for dermatophilosis in cattle (Hordofa et al., 2025; Nath et al., 2010; Burd et al., 2007), as clinically recommended topical, parenteral, and local formulations have shown limited success, and a vaccine remains unavailable—largely due to critical gaps that persist in understanding its genomic architecture, virulence mechanisms, and antimicrobial resistance profiles. Notably, rising antibiotic resistance complicates disease control and treatment (Branford et al., 2021; Zaria, 1993). Furthermore, the zoonotic potential of D. congolensis underscores its importance within a One Health framework, yet studies addressing its public health implications are scarce (Burd et al., 2007).

This review aims to synthesize current molecular and genomic knowledge of D. congolensis, focusing on its resistome landscape and virulence factors. We discuss recent advances in genomic sequencing, phylogenetic insights, and antimicrobial resistance mechanisms, highlighting their implications for disease diagnosis, treatment, and management in cattle. By identifying research gaps and emerging trends, this review seeks to inform future investigations and support the development of effective strategies to mitigate the impact of dermatophilosis on animal health and livestock production.

Molecular Characterization of D. congolensis

D. congolensis has been characterized by whole-genome sequencing and bioinformatic analysis, exploring the genomic characteristics that provide a clear comprehension of its genetic structure and diversity. The genome is approximately 2.6 Mb in size (Branford et al., 2021), where the base composition of D. congolensis has been analyzed, revealing a guanine plus cytosine (GC) content ranging from 57.4 to 58.7 mol%, which is consistent with its classification within the family Dermatophilaceae (Samsonoff et al., 1977). In contrast to soil-dwelling Actinobacteria like Streptomyces, which frequently have larger genomes and higher GC content to allow complex secondary metabolite production, D. congolensis’s moderate GC content may represent genomic adaptations to its biological niche as a skin pathogen (Nouioui et al., 2018). The genome of D. congolensis typically had 2527 coding sequences (CDS), 49 transfer RNAs (tRNA), with the exception of BTSK20, BTSK22, and BTSK31, which encode 52 tRNAs, and BTSK5, BTSK28, and BTSK34, which encode 43, 46, and 48 tRNAs, respectively. Each genome also contains three ribosomal RNAs (rRNA) (Branford et al., 2021). A number of studies have investigated the genomic characteristics of D. congolensis to better understand the pathogen’s genetic composition, pathogenesis, and its evolutionary adaptation. Investigating the genome of D. Congolensis is important for the identification of the major virulence factors, resistance patterns, and developing control strategies. Through analysis and better comprehension of this pathogen, a potential vaccine candidate and therapeutic target can be developed. Previous studies have shown that D. congolensis is a high GC-content member of the Actinobacteria, with a genome encoding approximately 2,527 genes (Branford et al., 2021). Among these, 23 housekeeping genes are associated with antimicrobial susceptibility mechanisms, and some isolates have been found to encode the acquired antimicrobial resistance gene tet(Z), which is implicated in tetracycline resistance (Branford et al., 2021).

In an effort to better understand D. congolensis genetic diversity, evolutionary links, and divergence from related bacteria, phylogenetic analysis has been performed using a variety of molecular approaches. Whole-genome comparisons, single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis, and 16S rRNA gene sequencing have been among the primary areas of research. Phylogenetic analysis of D. congolensis has shown minimal genetic diversity among isolates, indicating structural and functional conservation. A study on Nigerian isolates confirmed D. congolensis as phylogenetically distinct but more closely related to Nocardia brasiliensis than Streptomyces sp (Oladunni et al., 2016). Additionally, strain D 363 closely resembled DSM44180, NBRC105199, C2, and D.C16SrRNA, while strain D 362 was similar to S3 and S2 from GenBank (Oladunni et al., 2016). Moreover, sequence analysis of a D. congolensis isolate from sheep revealed 99–100% sequence homology with other D. congolensis isolates in the NCBI database (Chitra et al., 2017). The phylogenetic analysis showed a close clustering with isolates from Congo, Nigeria, and Angola, indicating strong genetic relatedness among African strains (Chitra et al., 2017). Another study on the phenotypic and genotypic characterization of D. congolensis isolates from cattle, sheep, and goats in Jos, Nigeria, revealed over 98% sequence similarity among the isolates, with variations observed at specific nucleotide positions (Samson et al., 2011). Phylogenetic analysis further confirmed a 99% identity between the isolates and D. congolensis DSM 44180 from GenBank. The phylogenetic tree clustered the isolates into two main groups, indicating a close evolutionary relationship across host species. This high degree of genetic similarity suggests that the isolates are likely strains of the same species (Samson et al., 2011). Further investigation of the genetic diversity of D. congolensis has been gained through SNP-based phylogenetic analysis, which identified three major clusters. The first cluster comprised geographically diverse strains, which contained 27–33 CRISPR spacers, reflecting genetic variability. The second cluster consisted of strains from a single location, all of which carried six CRISPR spacers and frequently harbored the tet(Z) antimicrobial resistance gene, suggesting a localized adaptation to tetracycline exposure. The third cluster comprised strains from two distinct locations, exhibiting 4–5 CRISPR spacers, which represent an intermediate genetic profile (Branford et al., 2021).

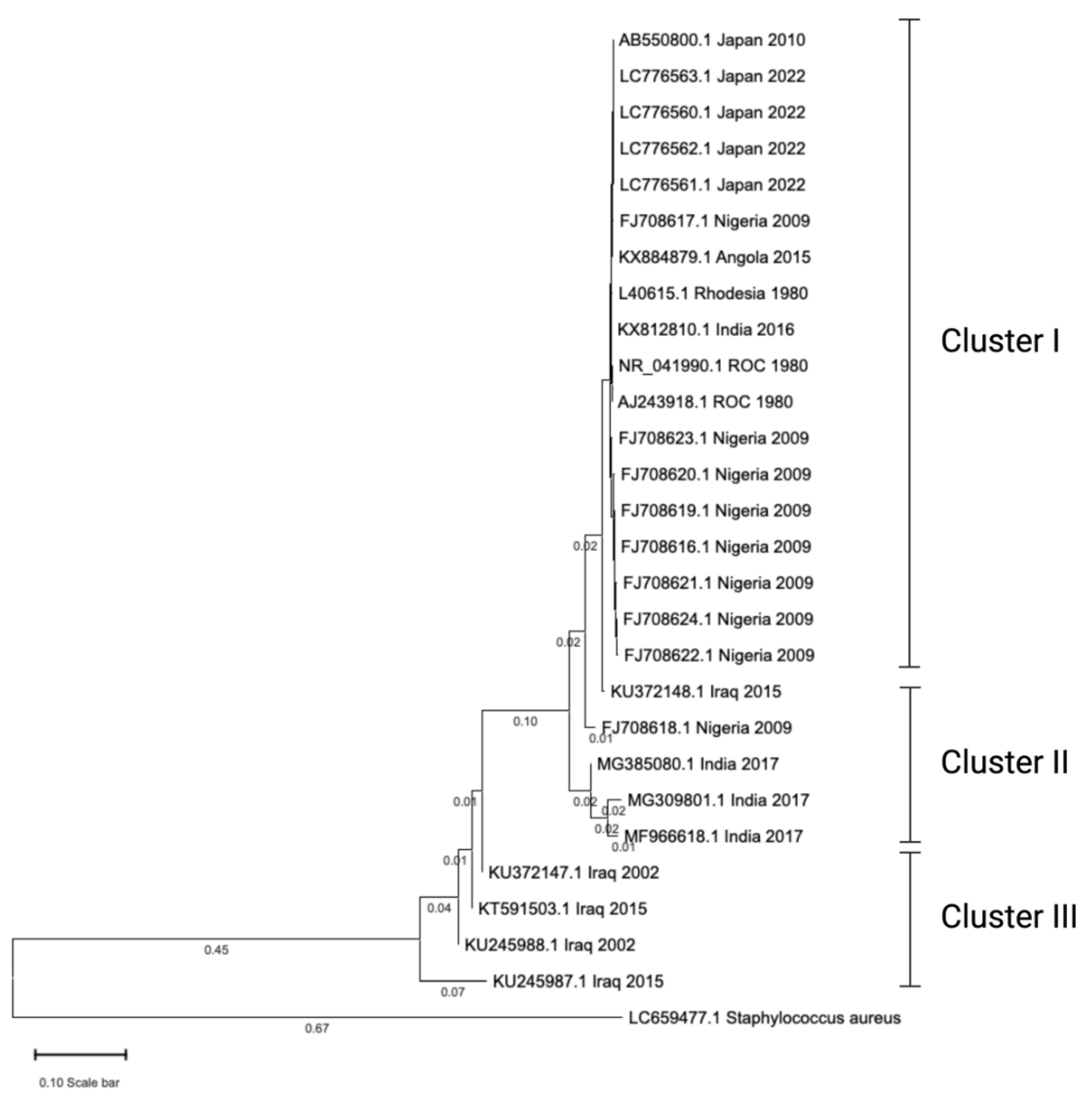

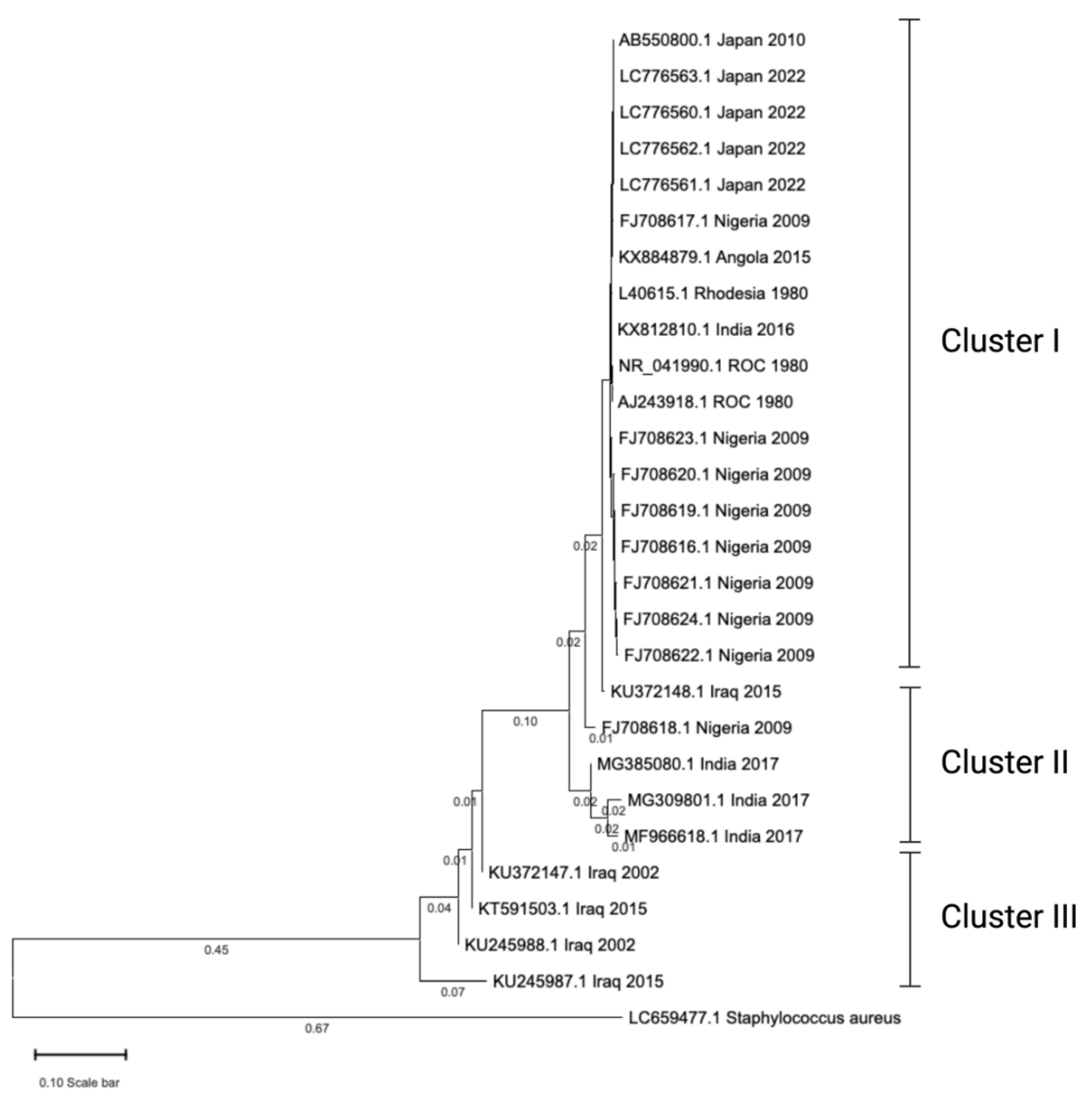

In our recent phylogenetic analysis, we examined 28 16S rRNA gene sequences of Dermatophilus congolensis obtained from diverse geographic regions. The phylogenetic tree revealed tight clustering of sequences from individual countries, such as Nigeria (2009) and Japan (2022), which exhibited short branch lengths, indicating circulation of closely related or identical strains within those regions. Based on the topology, the tree can be divided into three major clusters (Cluster I, II, and III), representing distinct phylogenetic lineages. Sequences from Japan and Iraq formed separate, well-supported clades and were notably distant from other groups, highlighting significant genetic divergence and suggesting unique evolutionary trajectories in these regions. The pairwise sequence identity within these two countries ranged from 71% to 83%, whereas sequences from other countries displayed higher similarity, with identities ranging from 88% to 100%.

Figure 2.

Evolutionary tree of 16s rRNA sequences of

Dermatophilus congolensis. A total of 28 sequences were retrieved from GenBank. Twenty-seven of the sequences were

D. congolensis, and one of them was Staphylococcus aureus, serving as an outgroup. The sequences were imported into CLUSTERW online platform (

https://www.genome.jp/tools-bin/clustalw) to perform multiple sequence alignment (MSA). The resultant MSA was imported into MEGA 11 software to create a phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method (Saitou and Nei, 1987). The optimal tree is shown. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths (below the branches) in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method (Tamura, 2004) and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. On the tree, each sequence was represented with an accession number, geographical location of the isolates, and year of isolation of bacteria. ROC: Republic of the Congo. Branch length that was less than 0.01 was hidden to avoid tree ambiguity.

Figure 2.

Evolutionary tree of 16s rRNA sequences of

Dermatophilus congolensis. A total of 28 sequences were retrieved from GenBank. Twenty-seven of the sequences were

D. congolensis, and one of them was Staphylococcus aureus, serving as an outgroup. The sequences were imported into CLUSTERW online platform (

https://www.genome.jp/tools-bin/clustalw) to perform multiple sequence alignment (MSA). The resultant MSA was imported into MEGA 11 software to create a phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method (Saitou and Nei, 1987). The optimal tree is shown. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths (below the branches) in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method (Tamura, 2004) and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. On the tree, each sequence was represented with an accession number, geographical location of the isolates, and year of isolation of bacteria. ROC: Republic of the Congo. Branch length that was less than 0.01 was hidden to avoid tree ambiguity.

Therefore, the genomic and phylogenetic analyses of D. congolensis provide insight into the genetic composition, diversity, and evolutionary adaptations. This knowledge has significant implications for disease control, antimicrobial resistance monitoring, and the development of targeted therapeutic interventions.

D. congolensis employs several virulence factors to establish infection and evade host defenses, though their functional roles remain partially characterized. Among these, proteolytic enzymes, particularly serine protease (nasp gene) (Garcia-Sanchez et al., 2004), play a crucial role in epidermal invasion. This extracellular enzyme degrades host tissues, enabling the bacterium to penetrate deeper layers of the skin and form lesions (Cerrato et al., 2004). However, protease activity varies between isolates, with some lacking detectable serine protease genes, indicating functional diversity in virulence strategies (Ambrose, 1996). Besides these enzymatic factors, the agac gene, which encodes an alkaline ceramidase protein, provides a robust molecular marker for detection. The agac gene forms the basis of a highly specific SYBR Green real-time PCR (RT-PCR) assay, developed to rapidly identify D. congolensis DNA in clinical samples. This assay demonstrates exceptional sensitivity, with a detection limit of 1 pg DNA per reaction and no cross-reactivity with closely related or other common bacterial species, supporting its diagnostic precision. All clinical isolates tested yielded positive results, confirming the reliability of agac-based molecular detection methods. Although the agac gene’s role in virulence is less directly characterized compared to proteolytic enzymes, its stable presence across D. congolensis strains underpins its value for laboratory confirmation, while also revealing minimal sequence variability among isolates tested (García et al., 2013). In addition to enzymatic degradation, D. congolensis utilizes structural invasion mechanisms such as hyphae and zoospores. Hyphae are filamentous structures that actively penetrate the epidermis, triggering acute inflammation and leading to repeated cycles of tissue invasion (Tellam et al., 2021; Ambrose, 1996). Zoospores, which are motile and flagellated, facilitate the spread of infection to new sites, especially in the presence of moisture and skin damage (Burd et al., 2007).

Resistome Profile of D. congolensis

Antibiotics are the major drugs used for the treatment of dermatophilosis; historically, drugs such as amoxicillin, ampicillin, chloramphenicol, erythromycin, novobiocin, penicillin G, spiramycin, streptomycin, and tetracyclines have been effective (Tresamol and Saseendranath, 2013; Amor et al., 2011). However, D. congolensis has been reported to have developed resistance to certain antimicrobial agents, although comprehensive data on its antibiotic resistance profile remain limited. Tetracycline is the only antibiotic for which the resistant mechanism and transmission have been studied to some extent. A recent comprehensive genomic study reported the spread of tet(Z) gene within the population of D. congolensis isolated from animal origin (Branford et al., 2021). This gene has been seen to be associated with tetracycline resistance.

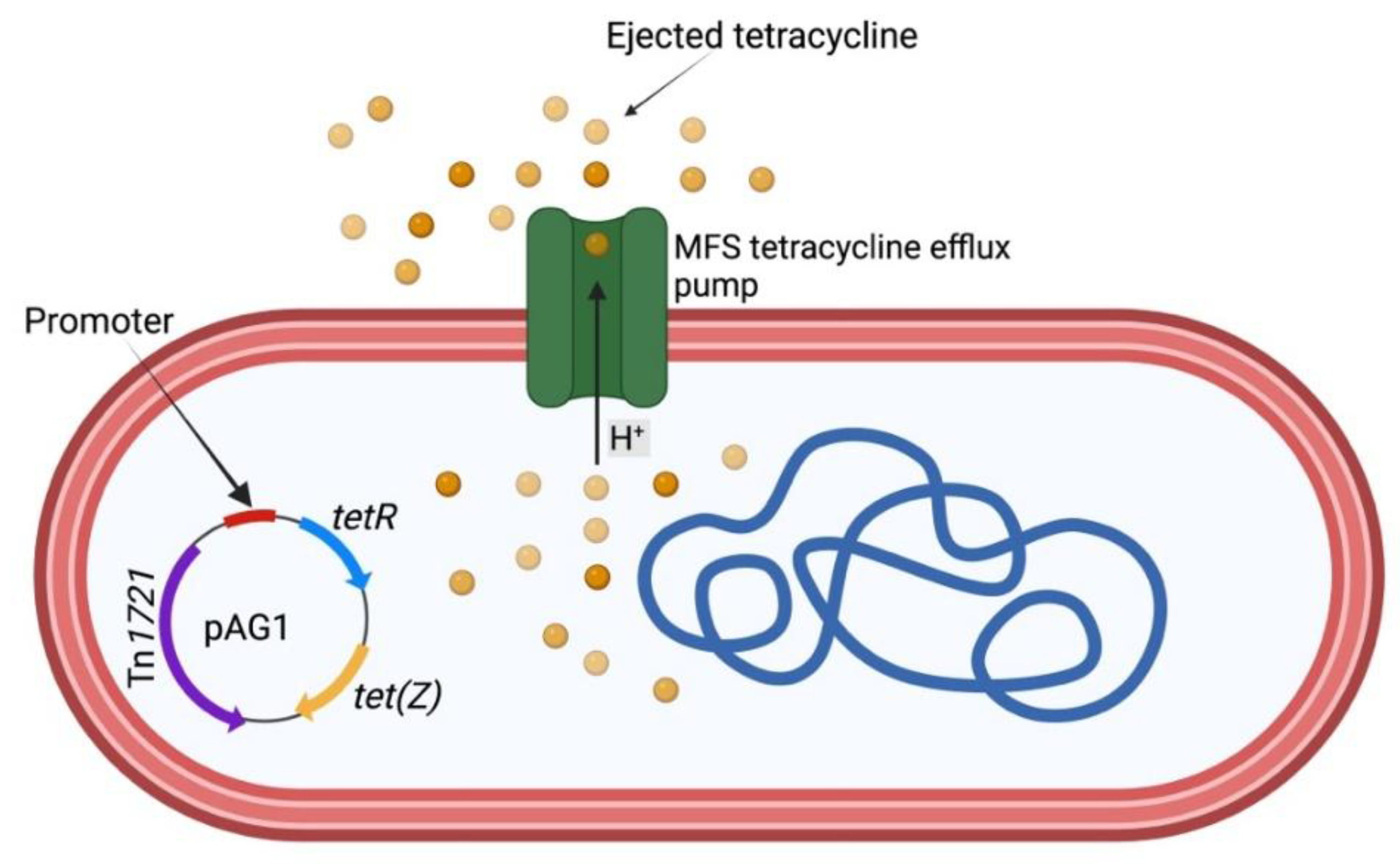

tet(Z) is a rare antibiotic-resistant gene that codes for tetracycline efflux protein (TetZ). It was first described by Tauch et al. (2000). It is carried by transposon Tn1721, which is encoded on the pAG1 plasmid. The detection of tet(Z) in

D. congolensis poses a great threat to the treatment of dermatophilosis. TetZ protein uses an efflux pump resistance mechanism to eject tetracycline. Currently, there is no study that has fully investigated this mechanism. However, we propose that the mechanism will not be different from the mechanism used by other Gram-positive bacteria (

Figure 3). More research is needed to ascertain our proposed mechanism.

In addition to the tet(Z) that confers tetracycline resistance in D. congolensis, twenty-five housekeeping genes have been reported to be associated with its susceptibility against a wide range of antibiotics (Branford et al., 2021). They include: Dfr, PgsA, Iso-tRNA, rpoB, Mtra, EF-G, kasA, rpsL, Ddl, S12p, EF-Tu, folP, gyrA, S10p rpoC, Alr, OxyR, rho, folA, gyrB, inhA, fabl, dxr, MtrB, and gidB. Judicious use of antibiotics in the treatment of dermatophilosis is required in order to prevent the resistance of these genes to their respective antibiotics.

Implications for Cattle Health and Disease Control

Diagnosis of D. congolensis is commonly done by cytology from lesions or bacterial culture. However, some recent advancements in molecular characterisation techniques have allowed researchers to explore the genomic profile of D. congolensis in greater depth (Oladunni et al., 2016). The draft genome sequences of multiple D. congolensis isolates have provided insights into the pathogen’s resistome profile, which is critical for improving disease diagnosis and treatment strategies. Identifying specific genes associated with virulence and antibiotic resistance can aid in developing more accurate diagnostic tools. For instance, a study shows the detection of the tet(Z) gene, which confers resistance to tetracyclines, in several isolates, highlighting the need for targeted treatments based on the pathogen’s resistance profile (Branford et al., 2021). Molecular characterisation, therefore, plays a vital role in enhancing disease diagnosis and guiding veterinarians in selecting appropriate interventions, ultimately improving the overall management of dermatophilosis in cattle.

One of the most pressing concerns in cattle production is the rise of antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains, which complicates the treatment of dermatophilosis. The overuse and misuse of antibiotics in cattle farming have contributed to the development of antibiotic resistance in pathogens such as D. congolensis. Identifying resistance genes in D. congolensis isolates underscores the importance of responsible antibiotic stewardship (Branford et al., 2021). By promoting the judicious use of antibiotics and adopting alternative strategies for disease control, such as improving biosecurity measures and the use of vaccines, cattle producers can help mitigate the spread of resistant bacterial strains. Antibiotic stewardship is essential for preserving the efficacy of existing treatments and reducing the overall burden of antibiotic resistance in livestock production systems.

A study has previously shown that antibiotics such as erythromycin, penicillin, ampicillin, and tetracyclines are effective against D. congolensis; however, the misuse or overuse of these antibiotics has led to the emergence of resistance in some isolates (Valipe et al., 2009). Specific resistance was observed in D. congolensis against antibiotics like polymyxin B, enrofloxacin, oxacillin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. The rise of antibiotic-resistant strains necessitates alternative treatments and management of antibiotic use in both veterinary practice and cattle production. Antibiotic stewardship programs should focus on reducing the dependence on broad-spectrum antibiotics, encouraging targeted therapy based on antibiotic sensitivity testing.

Going forward, research efforts should focus on further understanding the pathogenic mechanisms of D. congolensis and developing more effective control and management strategies. Scientists should channel more studies into vaccine development targeting specific antigens produced by D. congolensis during infection. Vaccines could offer a long-term solution for preventing dermatophilosis outbreaks, especially in regions where environmental conditions promote the spread of the disease. Additionally, exploring alternative therapies, such as bacteriophage-based treatments, may provide new avenues for controlling D. congolensis infections without relying on traditional antibiotics. There is also a need to understand the environmental and host factors that contribute to disease transmission, which are critical for developing comprehensive management strategies that minimise the impact of dermatophilosis on cattle health and productivity. Therefore, advances in molecular characterisation and antibiotic stewardship practices are essential for improving disease management in Dermatophilus congolensis and should receive urgent attention. The government should also work with relevant stakeholders to fund research that explores innovative solutions, such as vaccine development and alternative therapies, to reduce the burden of this pathogen on cattle production systems.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the molecular characterization and resistome profiling of Dermatophilus congolensis offer valuable insights into the biology, pathogenicity, and antimicrobial resistance of this important cattle pathogen. The identification of key virulence factors and antibiotic resistance mechanisms reveals the complexity of its interactions with the host and its capacity to evade therapeutic interventions. The presence of mobile genetic elements further raises concerns about the potential for horizontal gene transfer and the emergence of multidrug-resistant strains. These findings emphasize the urgent need for improved diagnostic tools, evidence-based treatment protocols, and prudent antibiotic use in livestock management. Future research should focus on functional genomics, surveillance of antimicrobial resistance patterns, and the development of novel therapeutic and preventive measures. A deeper understanding of D. congolensis at the molecular level will contribute to more effective disease control strategies, improved animal welfare, and enhanced productivity in cattle.

Author Contributions

Olamilekan Gabriel Banwo: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Conceptualization. Olalekan Chris Akinsulie: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Resources, Data curation. Ridwan Olamilekan Adesola: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Resources, Data curation. Olalekan Taiwo Jeremiah: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision.

Data Availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ambrose, N.C., 1996. The pathogenesis of dermatophilosis. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 28(2 Suppl), 29S–37S. [CrossRef]

- Amor, A., Enríquez, A., Corcuera, M.T., Toro, C., Herrero, D., Baquero, M., 2011. Is infection by Dermatophilus congolensis underdiagnosed? J Clin Microbiol. 49(1), 449-51. [CrossRef]

- Branford, I., Johnson, S., Chapwanya, A., Zayas, S., Boyen, F., Mielcarska, M.B., Szulc-Dąbrowska, L., Butaye, P., Toka, F.N., 2021. Comprehensive molecular dissection of Dermatophilus congolensis genome and first observation of tet(Z) tetracycline resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(13), 7128. [CrossRef]

- Burd, E.M., Juzych, L.A., Rudrik, J.T., Habib, F., 2007. Pustular dermatitis caused by Dermatophilus congolensis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45(5), 1655. [CrossRef]

- Cerrato, R., Larrasa, J., Ambrose, N.C., Parra, A., Alonso, J.M., Rey, J.M., Mine, M.O., Carnegie, P.R., Ellis, T.M., Masters, A.M., Pemberton, A.D., 2004. Characterisation of an extracellular serine protease gene (nasp gene) from Dermatophilus congolensis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 231(1), 53–57. [CrossRef]

- Chitra, M.A., Jayalakshmi, K., Ponnusamy, P., Manickam, R., Ronald, B.S.M., 2017. Dermatophilus congolensis infection in sheep and goats in Delta region of Tamil Nadu. Vet. World. 10(11), 1314–1318. [CrossRef]

- Dickson, C., de Elías Costa, M.R.I., 2010. Human and animal dermatophilosis. An unusual case report and review of the literature. Dermatol. Arg. 16, 349-353.

- García, A., Martínez, R., Benitez-Medina, J.M., Risco, D., Garcia, W.L., Rey, J., Alonso, J.M., Hermoso de Mendoza, J., 2013. Development of a real-time SYBR Green PCR assay for the rapid detection of Dermatophilus congolensis. J. Vet. Sci. 14(4), 491–494. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Sanchez, A., Cerrato, R., Larrasa, J., Ambrose, N.C., Parra, A., Alonso, J.M., Hermoso-de-Mendoza, M., Rey, J.M., Mine, M.O., Carnegie, P.R., Ellis, T.M., Masters, A.M., Pemberton, A.D., Hermoso-de-Mendoza, J., 2004. Characterisation of an extracellular serine protease gene (nasp gene) from Dermatophilus congolensis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 231(1), 53–57. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, M.A., Edwards, M.R., 1963. Micromorphology of Dermatophilus congolensis. J. Bacteriol. 86(5), 1101–1115. [CrossRef]

- Hemavathi, A., Sai Nehru, B., Vivek Srinivas, V.M., Kathiresan, R., Devadevi, N., Jayalakshmi, V., Mukhopadhyay, H.K., 2023. Isolation, PCR based Diagnosis and Therapeutic Management of Bovine Dermatophilosis. J. Anim. Res. 13(1), 93-98.

- Hordofa, N.D., Sori, T., Befekadu, B., 2025. Chronic Form of Dematophilosis Treatment Response With Long-Acting Oxytetracycline in Cattle: Case Report. Vet. Med. Sci. 11(3), e70339. 11. [CrossRef]

- Nath, B.D., Ahasan, S., Rahman, S., Huque, A.K.M.F., Nath, B.D., Rahman, M.S., HUQUE, A., 2010. Prevalence and therapeutic management of bovine dermatophilosis. Bangladesh Research Publications Journal 4.3: 198-207.

- Nouioui, I., Carro, L., Woyke, T., Kyrpides, N. C., Pukall, R., Klenk, H. P., Goodfellow, M., Göker, M., 2018. Genome-based taxonomic classification of the phylum Actinobacteria. Front. Microbiol. 9, 355158. [CrossRef]

- Oladunni, F.S., Oyekunle, M.A., Talabi, A.O., Ojo, O.E., Takeet, M.I., Adam, M., Raufu, I.A., 2016. Phylogenetic analysis of Dermatophilus congolensis isolated from naturally infected cattle in Abeokuta and Ilorin, Nigeria. Vet. med. sci. 2(2), 136. [CrossRef]

- Osman, S.A., 2014. Camel dermatophilosis: Clinical signs and treatment outcomes. J. Camel Pract. Res. 21(2), 199-204.

- Quinn, P.J., Markey, B.K., Carter, E.M., Donnelly, J.W., Leonard, C.F., 2002. Veterinary Microbiology and Microbial Disease. first ed. Black Well Publishing Company, USA, 69–70.

- Saitou, N., Nei, M., 1987. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4, 406-425. [CrossRef]

- Samsonoff, W.A., Detlefsen, M.A., Fonseca, A.F., Edwards, M.R., 1977. Deoxyribonucleic acid base composition of Dermatophilus congolensis and Geodermatophilus obscurus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 27(1), 22–25. [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K., Nei, M., Kumar, S., 2004. Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101(30), 11030–11035. [CrossRef]

- Tauch, A., Pühler, A., Kalinowski, J., Thierbach, G., 2000. TetZ, a new tetracycline resistance determinant discovered in gram-positive bacteria, shows high homology to gram-negative regulated efflux systems. Plasmid, 44(3), 285–291. [CrossRef]

- Tellam, R. L., Vuocolo, T., Denman, S., Ingham, A., Wijffels, G., James, P. J., Colditz, I.G., Jacob, R., 2021. Dermatophilosis (lumpy wool) in sheep: a review of pathogenesis, aetiology, resistance and vaccines. Anim. Prod. Sci. 62(2), 101–113. [CrossRef]

- Tresamol, P.V., Saseendranath, M.R., 2013. Antibiogram of Dermatophilus congolensis isolates from cattle. Int. J. Live. Res. 3, 117–121.

- Valipe, S., Choi, G., Morton, M., Nadeau, J., 2009. Investigation of the Antimicrobial Mechanism of Caprylic Acid on Dermatophilus congolensis. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 29(5), 404-405. [CrossRef]

- Yeruham, I., Elad, D., Perl, S., 2003. Dermatophilosis in goats in the Judean foothills. Rev. Med. Vet. 154(12), 785-788.

- Zaria L. T., 1993. Dermatophilus congolensis infection (Dermatophilosis) in animals and man! An update. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 16(3), 179–222. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).